In this volume:

Including Our 2003 Fiction & Nonfiction Prize Winners

7

9 1

ISSN 1083-5571

AWP Intro Winners

77108 3 5 5 7 1

$8.00

Mary Quade Sara Quinn Rivara Nicholas Samaras Sean Serrell Neil Shepard Betsy Sholl Taije Silverman Maggie Smith Liz Stefaniak Kevin Stein Alexandra van de Kamp Latha Viswanathan Sophie Wadsworth Braden Welborn Gabriel Welsch Kathy Whitcomb

$8.00us Vol. 9 No. 1

9

Yahya Frederickson Elton Glaser Luisa Igloria HonorĂŠe Fanonne Jeffers Anne Keefe Steve Kistulentz Elizabeth Knapp Melissa Kwasny Jacqueline Jones LaMon Lisa Lewis Linda Mannheim Debra Marquart John Minczeski Missy-Marie Montgomery Paula Nangle James P. Othmer Donald Platt

Volume 9, Number 1 Winter/Spring 2004

Danny Anderson S. Beth Bishop Bruce Bond Amy Knox Brown Joel Brouwer Anthony Butts Stacy Gillett Coyle Melissa Crowe Jim Daniels Traci Dant Oliver de la Paz Matt Donovan Kevin Ducey Nancy Eimers Robin Farabaugh Beth Ann Fennelly Vievee Francis

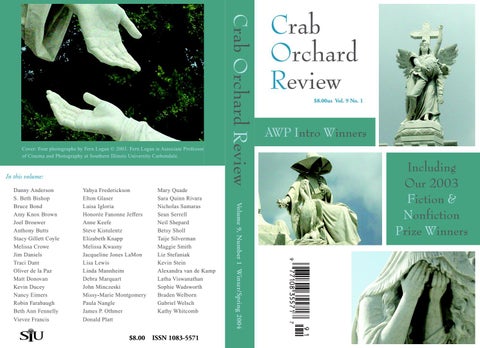

Crab Orchard Review

Cover: Four photographs by Fern Logan Š 2003. Fern Logan is Associate Professor of Cinema and Photography at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Crab Orchard Review