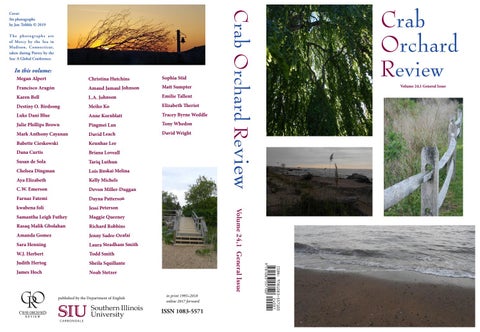

The photographs are of Mercy by the Sea in Madison, Connecticut, taken during Poetry by the Sea: A Global Conference.

In this volume: Christina Hutchins

Sophia Stid

Francisco Aragón

Amaud Jamaul Johnson

Matt Sumpter

Karen Bell

L.A. Johnson

Emilie Tallent

Destiny O. Birdsong

Meiko Ko

Elizabeth Theriot

Luke Dani Blue

Anne Kornblatt

Tracey Byrne Weddle

Julie Phillips Brown

Pingmei Lan

Tony Whedon

Mark Anthony Cayanan

David Leach

David Wright

Babette Cieskowski

Keunhae Lee

Dana Curtis

Briana Loveall

Susan de Sola

Tariq Luthun

Chelsea Dingman

Lois Ruskai Melina

Aya Elizabeth

Kelly Michels

C.W. Emerson

Devon Miller-Duggan

Farnaz Fatemi

Dayna Patterson

kwabena foli

Jessi Peterson

Samantha Leigh Futhey

Maggie Queeney

Rasaq Malik Gbolahan

Richard Robbins

Amanda Gomez

Jenny Sadre-Orafai

Sara Henning

Laura Steadham Smith

W.J. Herbert

Todd Smith

Judith Hertog

Sheila Squillante

James Hoch

Noah Stetzer

CO R

CR AB ORCH AR D •

•

REVIEW

published by the Department of English

Volume 24,1 General Issue

Megan Alpert

Crab Orchard Review

Cover: Six photographs by Jon Tribble © 2019

in print 1995–2018 online 2017 forward

ISSN 1083-5571

Crab Orchard Review Volume 24,1 General Issue