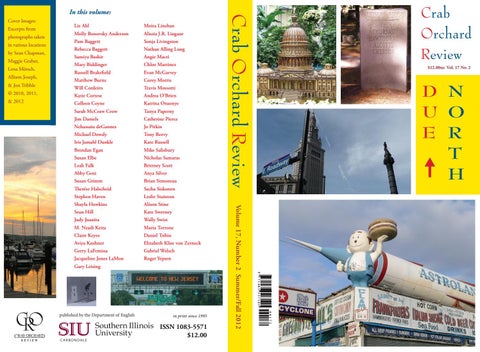

Excerpts from photographs taken in various locations by Sean Chapman, Maggie Graber, Lena Mörsch, Allison Joseph, & Jon Tribble © 2010, 2011, & 2012

•

REVIEW

ISSN 1083-5571 $12.00

D N U O E R T H

00172

•

in print since 1995

$12.00us Vol. 17 No. 2

9 771083 557101

CR AB ORCH AR D

published by the Department of English

Moira Linehan Alissia J.R. Lingaur Sonja Livingston Nathan Alling Long Angie Macri Chloe Martinez Evan McGarvey Corey Morris Travis Mossotti Andrea O’Brien Katrina Otuonye Tanya Paperny Catherine Pierce Jo Pitkin Tony Reevy Kate Russell Mike Salisbury Nicholas Samaras Brittney Scott Anya Silver Brian Simoneau Sacha Siskonen Leslie Stainton Alison Stine Kate Sweeney Wally Swist Maria Terrone Daniel Tobin Elizabeth Klise von Zerneck Gabriel Welsch Roger Yepsen

Volume 17, Number 2 Summer/Fall 2012

CO R

Liz Ahl Molly Bonovsky Anderson Pam Baggett Rebecca Baggett Samiya Bashir Mary Biddinger Russell Brakefield Matthew Burns Will Cordeiro Katie Cortese Colleen Coyne Sarah McCraw Crow Jim Daniels Nehassaiu deGannes Michael Dowdy Iris Jamahl Dunkle Brendan Egan Susan Elbe Leah Falk Abby Geni Susan Grimm Therése Halscheid Stephen Haven Shayla Hawkins Sean Hill Judy Juanita M. Nzadi Keita Claire Keyes Aviya Kushner Gerry LaFemina Jacqueline Jones LaMon Gary Leising

Crab Orchard Review

Crab Orchard Review

In this volume: Cover Images: