Andrei Guruianu Lorraine Healy Laura Johnson Meredith Kunsa Việt Lê Bethany Tyler Lee Jeffrey Thomas Leong Karen Llagas Amit Majmudar Peter Marcus Daiva Markelis Carrie Messenger Adela Najarro Iain Haley Pollock Michele Poulos Mary Quade Bushra Rehman Thomas Reiter José Edmundo Ocampo Reyes

CO R

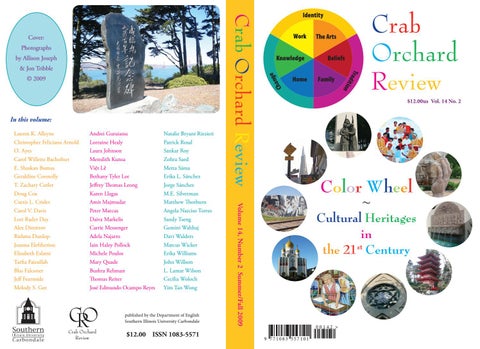

Crab Orchard Review

Natalie Bryant Rizzieri Patrick Rosal Sankar Roy Zohra Saed Metta Sáma Erika L. Sánchez Jorge Sánchez M.E. Silverman Matthew Thorburn Angela Narciso Torres Sandy Tseng Gemini Wahhaj Davi Walders Marcus Wicker Erika Williams John Willson L. Lamar Wilson Cecilia Woloch Yim Tan Wong

published by the Department of English Southern Illinois University Carbondale

$12.00 ISSN 1083-5571

Crab Orchard Review $12.00us Vol. 14 No. 2

Color Wheel

~ Cultural Heritages in the 21st Century

Volume 14, Number 2 Summer/Fall 2009

Lauren K. Alleyne Christopher Feliciano Arnold O. Ayes Carol Willette Bachofner E. Shaskan Bumas Geraldine Connolly T. Zachary Cotler Doug Cox Curtis L. Crisler Carol V. Davis Lori Rader Day Alex Dimitrov Rishma Dunlop Joanna Eleftheriou Elizabeth Eslami Tarfia Faizullah Blas Falconer Jeff Fearnside Melody S. Gee

Family

n

In this volume:

Home

Beliefs

itio

© 2009

The Arts

Tra d

& Jon Tribble

Knowledge nge

by Allison Joseph

Work

Cha

Photographs

Crab Orchard Review

Cover:

Identity

00142 > 9 771083 557101