Sire lines and how they emerge

An

essay by Chris McGrath

Sire lines and how they emerge

An

essay by Chris McGrath

and now sires of sires. What, asks Chris McGrath, is the source of their potency?

Those of the thoroughbred, in contrast, extend seamlessly with their constituent genes. They rise and fall on sheer inherited prowess. Ends and means are inseparable. Success IS succession.

The purity of that model might well seem eroded by our own interventions. For centuries, we have not just documented equine dynasties, but managed them. People have never given stallions equal opportunity. Yet many seasoned horsemen take the view that genes, in the end, will overcome even our most inept intrusion.

Ric Waldman, for instance, insists that no amount of mismanagement will prevent the rise of a potent stallion. ‘You might make it more difficult,’ says the man who supervised the stud career of Storm Cat. ‘But eventually the stallion is going to win out that argument.’ And it is an axiom of another sage of the Bluegrass, John Sikura of Hill ‘n’ Dale, that ‘the genetic switch is either on or off’ when a horse retires to stud. On this view, the best mares in the world will be unavailing, should the switch be off; if it happens to be on, as when Into Mischief was being ignored at $7,500 or Siyouni at €7,000, then even the basest material will allow a horse to show what he can do. But, even if that’s true, we cannot feel absolved of responsibility;

nor denied opportunity. The long evolution of the thoroughbred owes much to a series of breeders who recognised and facilitated the potential of a great stallion. Very often, they did so more than once.

Many have also insisted on the value, even to a prepotent stallion, of their complementary endeavours in the building of female families. True, those necessarily remain relatively confined in their reach. But that does not disqualify them from a role in what is, on the face of it, the most purely patriarchal quest of all: the ultimate grail, a sire of sires.

Now it’s hard enough to find a stallion who can replicate the genetic sources of his racetrack performance. How much harder, then, to discover one who can add that final signature of greatness, by in turn producing sons capable of recycling their legacy.

A stallion that does this is so rare that he can become synonymous with entire eras. At a time when the necessary attributes had been falling out of commercial favour, for instance, Sadler’s Wells restored the Derby as the definitive test of a thoroughbred through two sons, Galileo and Montjeu, whose stock proved peculiarly adapted to that challenge. To discover a sire of sires, the founder of a male line, duly stands as perhaps the greatest legacy to which a breeder can aspire. In the endlessly multiplied strands of ancestry, these stallions are the knots that allow future generations to keep their bearings.

is that there are no rules. Nobody has ever set out to breed a slow horse, but such tends to be the routine outcome. We simply do the best we can, and try to stay alert if something is palpably clicking. And that, excitingly, is just what has happened in the case of two horses foaled a few weeks apart in 2002, Dubawi and Shamardal.

With their ongoing consolidation as sires of sires, in fact, they have set an apt seal on one of the most lavishly funded breeding programmes in turf history. Darley’s very name, of course, attests to a long perspective. A sense of history perhaps sharpens the desire to bequeath a legacy, to find that stallion who might represent Darley’s contribution to the breed’s modern evolution to future generations.

In the event, Darley appears to have found two.

Dubawi and Shamardal both won G1 prizes as juveniles and Classics the following spring. Each then attempted a Derby – Dubawi stretching a little too far at Epsom, but Shamardal profiting from the reduction of the Prix du Jockey Club – before reverting to a mile. Each also represent fresh proliferations for two iconic sire lines already discussed: Shamardal, as a grandson of Storm Cat; and Dubawi, as a glorious bloom on a branch of Mr Prospector that would otherwise have withered with the cruel fate of Seeking The

Gold’s charismatic son Dubai Millennium.

It possibly feels anomalous to refer to a ‘founder of a male line’ when these horses are merely recycling their own genes. But let’s take Shamardal’s grandsire Storm Cat as an example. Whatever he may have owed to Storm Bird, the fact is Storm Cat’s sire did not produce other sons that might allow him to brand as his own this branch of the Northern Dancer dynasty. Different sons of Storm Cat, in contrast, today dominate the Kentucky landscape, in particular, after launching the rival houses of Into Mischief (via Harlan), Not This Time (via Giant’s Causeway) and Justify (via Hennessy). Two of these branches have meanwhile flourished in the European theatre, too: Scat Daddy and now No Nay Never trace to Hennessy, and of course Shamardal has absolutely exemplified the speed and toughness of Storm Cat as the principal European heir of Giant’s Causeway.

sire, logically Storm Cat must owe some kind of debt to his dam, Terlingua, whose sire Secretariat notoriously failed to establish a sire line despite his historic prowess on the racetrack and commensurate opportunity at stud. The calibre of his mares is doubtless central to Secretariat’s contrasting profile as a distaff influence, extending beyond Storm Cat to other important stallions such as AP Indy and Gone West. The latter had a major footprint in Europe, where Holy Roman Emperor also proved able to adapt the wares of a Secretariat mare to a different racing environment.

If anything, Terlingua’s racing career almost suggests Secretariat to have served as a passive conduit for the blazing speed of her dam Crimson Saint, who broke the Hollywood Park track record in :56 flat. Terlingua was fast, precocious and tough, all traits later trademarked by her son, and in turn by Shamardal. And something of that Storm Cat toughness surely traced to Crimson Saint’s sire, Crimson Satan (who mined 18 wins in 59 starts from the ore of his Argentinian antecedents).

One of the most intriguing questions arising from the unmistakable phenomenon of sires that excel as distaff influences is their propensity to have sons that do the same, and also daughters that go on to produce other broodmare sires. In the latter group we might include the Buckpasser mares that produced Miswaki, sire of the breed-shaping Urban Sea; El Gran Senor, responsible for the blue hen Toussaud, dam of four elite winners including Empire Maker. In the former category, meanwhile, Mill Reef was not just a noble broodmare sire himself but produced a son, Shirley Heights, and especially a grandson, Darshaan, to emulate his service. A very similar pattern can be observed between Nureyev, Polar Falcon and that paragon of this sphere, Pivotal. Another son

of Nureyev to achieve a huge impact through his daughters is Theatrical, while Peintre Celebre also entered the family trade.

These patterns permit no definitive explanation. The complexity of genetic inheritance, after all, may well include benefits as elementary as physiological aptitude for nourishing the embryo or nursing the suckling. In the round, however, they do imply some legitimacy for the ‘branding’ of sire lines.

make no greater genetic contribution to a horse than the three other stallions and four mares in the third generation. Often, in fact, it seems that the bloodstock industry only obsesses about stallions because the disparity of their output, especially in this era of enormous books, yields so much more evidence than a mare’s single foal (at most) per annum. But the phenomenon of a sire of sires would appear to confirm a heritable potency between fathers and sons.

Some people even argue that a prepotent stallion so dominates the portion of genetic inheritance most adapted to athletic performance that the complementary excellence we seek to offer him, through his mares, proves nearly superfluous. And there have certainly been stallions whose first, inexpensively conceived crops set standards barely maintained by the superior mares duly drawn into their books.

On this theory, the bull dominates the herd genetically as he does behaviourally. And that, on the face of it, might explain how certain stallions have emerged, over the past three centuries, to bestride an epoch: Eclipse, Phalaris, Northern Dancer.

Now it is true that each of these also happened to stumble across some historic opportunity. The stock of Eclipse proved to be especially adapted to the sport’s transition from its antediluvian format – heats over shattering distances, plus cat-and-mouse match racing – to something more recognisably modern, with larger fields sharing a single stampede over much shorter distances. Phalaris, little more than a high-class sprint handicapper during a truncated wartime programme, was tailormade for an era that conversely began to treat those abbreviated distances, in races like the Derby and St Leger, as relatively severe tests. And the cosmopolitan blend behind Northern Dancer reconciled the demands of dirt and turf racing, precisely as commercial breeding exploited competition between new investors of international ambition.

Even acknowledging that these stallions sailed well with a following wind, the fact remains that each produced an armada of sons and grandsons who replicated assets most pertinent to their time. Paradoxically, however, that process requires a reach – and

therefore a diversity – that dilutes the dominant character we tend to ascribe to a sire line.

We talk of Mr Prospector speed, for instance, because that was his own game. But while fast horses like Fappiano and Miswaki duly helped to get him established, he soon came up with a Belmont winner in Conquistador Cielo. And, in the end, his immense influence proved a matter of range and flexibility, just as it has for his scion three generations removed, Dubawi. Fappiano himself founded a dirt Classic line, while as a broodmare sire Miswaki stands behind some of the sturdiest turf blood in Europe: Galileo and Sea The Stars, Dalakhani, Hernando. Smart Strike began a line of late-maturing, long-running influences like Curlin, English Channel and Lookin At Lucky. And while many of Kingmambo’s top-class runners at 10 to 12 furlongs were out of mares by staying influences, he also got a St Leger winner out of a daughter of Royal Academy and a Never So Bold mare! Complementing all this stretch, meanwhile, there have been Mr Prospector lines that perhaps developed a more cosmopolitan interpretation of their founder’s speed, none more so than the one that finds its nexus in Dubawi.

So while Mr Prospector himself harnessed the speed of his sire Raise A Native, his second career surely drew upon the many Classic influences inlaid into his pedigree: his grandsire Native Dancer and the sires of both his first two dams, Nashua and Count Fleet, were all Belmont winners. A similar exercise would be so familiar with Danehill, as an ostensible conduit of ‘Danzig speed’, that it barely feels necessary. A fast horse himself, Danehill’s variegated output surely showcases the celebrated concentration of class across his pedigree: his second dam famously half-sister to his grandsire Northern Dancer; their dam, Natalma, in turn a half-sister to Halo’s dam Cosmah. And Halo, of course, gave us another transformative sire of sires in Sunday Silence. Note, however, that it is actually females who unite these celebrated founts of virility.

Dubai Millennium tragedy, as one of 56 foals in his sire’s only crop before succumbing to grass sickness in 2001, represents perhaps the greatest genetic weight borne by so fragile a thread since the Darley Arabian’s son ‘Bleeding’ Childers – untrainable due to vascular issues – excelled his champion brother, Flying Childers, in establishing a line that is now ubiquitous.

Dubai Millennium was not simply the single son of Seeking The Gold to peg down a male line (in the northern hemisphere, at any rate) but was also out of a mare whose sire was otherwise an expensive failure, in Shareef Dancer. Conversely his second dam, the G1 winner Fall Aspen, produced a whole series of elite performers and/or producers,

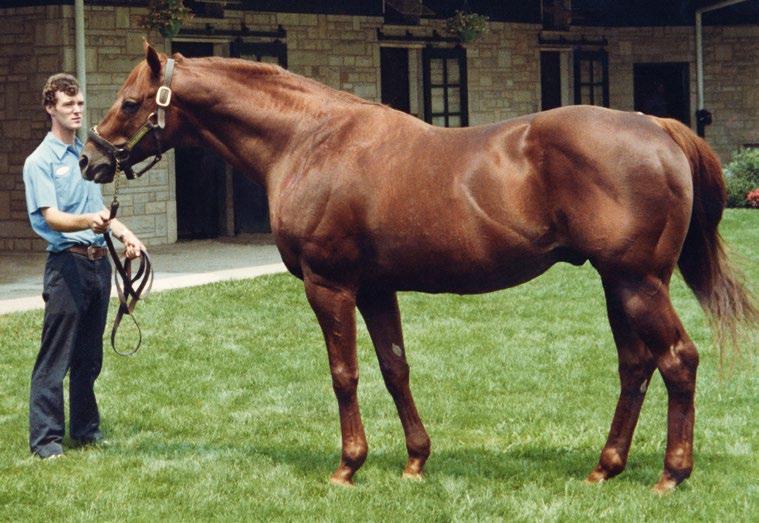

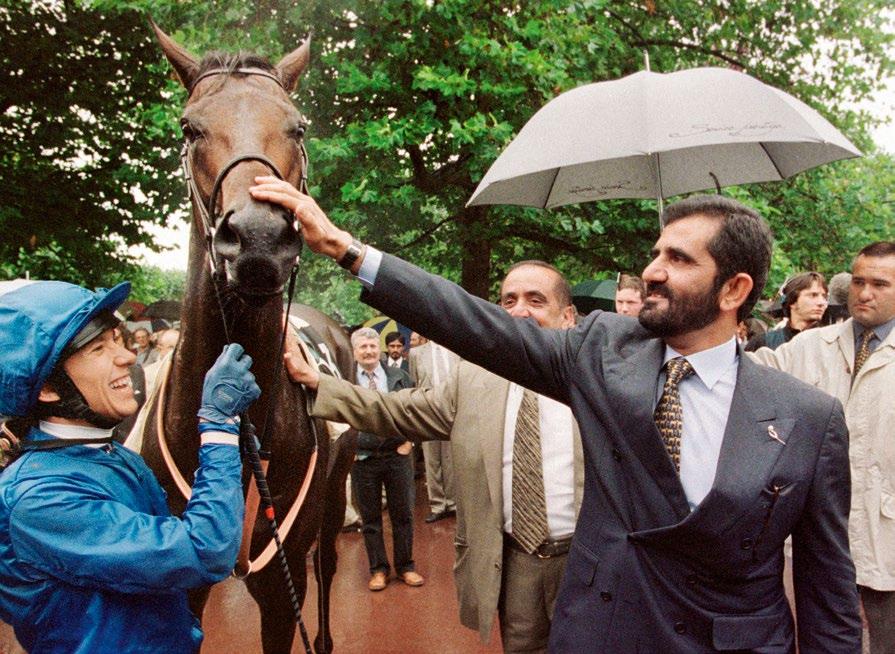

Dubawi’s sire line, clockwise from top left: Raise A Native, unraced after an undefeated juvenile season; his son Mr Prospector as a yearling, having sold for a sales-topping $220k at Keeneland July – he was the top sprinter of 1974; his son Seeking The Gold and his son Dubai Millennium, with Sheikh Mohammed after his debut G1 success in the Prix Jacques Le Marois, a race Dubawi also won.

Arguably the most significant horse in Dubawi’s pedigree is not a stallion at all: Dubai Millennium’s second dam, Fall Aspen.

Shareef Dancer and Sheikh Mohammed after winning the Irish Derby of 1983. Dubai Millennium’s broomare sire, a $3.3m yearling and son of Northern Dancer (in the black and white photo), was syndicated with a valuation of £24m to stand at Dalham Hall Stud. Above, Dubawi’s broodmare sire Deploy, a very well-bred non-Stakes winner who finished second in the Irish Derby.

which would appear to volunteer her as the most obvious resource for Dubawi to have mined behind his sire.

Dubawi’s dam and grandam were both by Juddmonte stallions who arguably failed to meet expectations. Something surely percolated through Deploy that he generally failed to replicate in his stock, sharing genes as he did with siblings as celebrated as Warning, Commander In Chief, Dushyantor and Yashmak. Dubawi’s dam, Italian Oaks winner Zomaradah, was Deploy’s best runner; while her own mother contributes to the influence achieved through his daughters by Dancing Brave.

Whatever the shortfall between Dancing Brave’s first and second careers, it is striking that Dubawi’s maternal family is uniformly sown by staying influences. After Deploy and Dancing Brave, we find High Line and Sea Hawk, the latter through his daughter Sunbittern – who is also found (closer up, as grandam) behind In The Wings and HighRise. Deploy himself, remember, was by Shirley Heights out of the famous Roberto mare Slightly Dangerous, herself an Oaks runner-up and half-sister to the dam of Rainbow Quest. The kind of thing, in other words, that would today send commercial breeders screaming from the room!

For the complementary dash of brilliance, we should perhaps focus on the dirt speed that enabled Dubai Millennium’s grandam Fall Aspen to win races like the Matron (then seven furlongs) and Prioress (six). Her footprint as a broodmare was very wide, but did include winners of the July Cup and Diadem Stakes plus the dam of another July Cup winner. In standing directly opposite Mr Prospector in Dubai Millennium’s second generation, she presents a similar formula to the one that produced American Champion juvenile Timber Country, her son by Mr Prospector’s son Woodman.

a pretty deep well in grandam Helen Street, as an Irish Oaks winner by Troy. Most will seek the necessary foil of speed in his sire line, but perhaps we should sooner start with Machiavellian – whose four foals out of Helen Street included Street Cry as well as Shamardal’s dam Helsinki. That’s because Machiavellian can never be viewed merely as another conduit for Mr Prospector, when his dam Coup de Folie combines both the great daughters of Almahmoud.

She was by Cosmah’s son Halo out of Natalma’s daughter Raise the Standard. Again, it is the females that unite the virile brands: Shamardal extends a branch of the dynasty founded by Natalma’s son Northern Dancer; while his sire Giant’s Causeway was out of a mare by Rahy, whose damsire was Halo.

Picking out particular genetic strands to rationalise success is always a matter of personal prejudice, but clusters like this can only be reassuring. For some of us, indeed, depth is the key to all pedigree: if it’s all good stuff, it doesn’t matter what comes through. But destiny calls these horses in many a different voice, as seen from Shamardal’s eventual entry to the same stable as Dubawi. Famously subject of an insurance claim in his youth, owing to a spinal issue, he was restored to soundness in time to be shipped from Kentucky to Tattersalls where he cost Gainsborough just 50,000gns. Compare this haphazard redemption with the hopes vested in Dubawi, the anointed scion, aptly the first runner and first winner bequeathed by his nearly messianic sire!

£25,000, ultimately produced no fewer than six Group 1 winners from 120 live foals. Its first stars adhered to an expected template, milers like Makfi and Poet’s Voice making their name in races their sire had contested himself. Then Monterosso emulated his grandsire’s success in the Dubai World Cup, while from the second crop, Al Kazeem matured to win elite races over 10 furlongs; and a sturdy staying mare even gave Dubawi a German Derby winner in Waldpark. By his fifth crop, Dubawi’s range was established, and it duly produced not only the brilliant miler Night Of Thunder but also the middledistance star Postponed; while the next one, in 2012, produced New Bay to shine over the intermediate distance of the Prix du Jockey Club. From the following crop Zarak failed only narrowly to emulate that success.

By this stage, Dubawi’s fee had multiplied nearly tenfold, triggering competition among his sons as more accessible options. Poet’s Voice showed immediate promise, coming up with Poet’s Word on a £12,000 cover, but died at just 11. Instead it fell to Night Of Thunder to become Dubawi’s breakout son – and with stock very different to the slowburning stayer Poet’s Word.

Starting at a similarly modest level (his fee dipped to £15,000 in his third and fourth seasons), Night Of Thunder imparted such startling precocity that he matched the record of Fasliyev, a very different type, with seven Stakes winners from his first juveniles, and established a new record number of first-crop Stakes horses. Moreover, Highfield Princess, who would eventually prove best of that crop, only started life in handicaps the following summer off 57, discovering her metier with maturity over the bare five furlongs.

Hardly the inception that might have been anticipated for this sire line, when you recall all those grandfather clock stallions presiding over Dubawi’s maternal family. After all, Night Of Thunder (whose latest star Economics was pointedly spared a Derby slog)

Shamardal’s sire line, from top left: Storm Bird, undefeated at two, a flop at three; his son Storm Cat was second in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile; his son Giant’s Causeway was European Horse of the Year and also a Champion sire. Storm Cat’s legacy perhaps owes something to his broodmare sire, the extraordinary Secretariat.

Helen Street, Shamardal’s Classic winning grandam, was bred several times with Machiavellian, also producing leading sire Street Cry. Beneath his photo is Natalma, dam of Northern Dancer and half-sister to Cosmah, another significant mare on Shamardal’s page. The other two photos are of Terlingua, Storm Cat’s dam, and her lightning-fast mother Crimson Saint.

is out of a Galileo mare. But soon afterwards, in 2016, the Singspiel mare Dar Re Mi – a G1 winner at a mile and a half – gave Dubawi an unbeaten Champion juvenile. At three, moreover, Too Darn Hot dropped back to seven furlongs to resume the G1 thread, before relishing the test of speed at a mile presented by the Sussex Stakes.

Too Darn Hot in turn came up with a record four Group winners from his first crop of juveniles and has, meanwhile, comfortably eked out the mile for Classic winner Fallen Angel and Australian monster Broadsiding. Even his flying start at stud, however, left Too Darn Hot only second in the 2023 rookie standings, such was the prolific impact of his Darley neighbour Blue Point – whose astounding 51 winners included two at the elite level. And Blue Point, of course, is a son of Shamardal.

Fast starts have proved a hallmark of this line. Much as Shamardal had himself immediately secured the succession for Giant’s Causeway, so Lope de Vega emerged from his own debut crop to emulate his Poulains-Jockey Club double. (In turn Lope de Vega would also land running at stud, immediately producing Champion juvenile Belardo.)

Lope de Vega’s emergence actually arrested a slide in his sire’s fee, restoring him to €50,000 from €20,000. Unfortunately, Shamardal’s ability to sustain that momentum would be increasingly confined by the physical issues that eventually required rigorous control of his books at Kildangan Stud. Nonetheless he continued to produce a series of eligible heirs.

three brilliant juveniles, Pinatubo, Earthlight and Victor Ludorum, setting a seal on an astounding record of at least one G1 winner from each of his first 11 crops. This trio carved up most of Europe’s top juvenile prizes (Pinatubo claiming the National Stakes and Dewhurst; Earthlight, the Morny and Middle Park; Victor Ludorum, the Lagardère) in the months after a fully mature Blue Point won two G1 sprints in four days at Royal Ascot.

Shamardal’s loss, the following year, duly came at the height of his reputation. But his posthumous stock includes at least one more future stallion in the making, in Inisherin, who joins Blue Point at the sharper end of what might be characterised, overall, as a speed-oriented brand. Certainly Shamardal’s occasional stayers, inevitable given the range among his high-quality mares, feel rather more of an aberration than in the case of Dubawi. Admittedly, Shamardal made a real hallmark of the turning 10½ furlongs at Chantilly, his own Jockey Club success having been emulated by a son and grandson in Lope de Vega and Look de Vega. Overall, however, Shamardal has done a lot of work in that miler-sprinter sweet spot. So, too, has Lope de Vega – who, crucially, is out of a mare

by Shamardal’s damsire Machiavellian. That hardly discourages the theory, already proposed, that Machiavellian’s impact here may owe more to his maternal blood than to even Mr Prospector.

An alternative emphasis may yet become necessary, however, should Victor Ludorum happen to outdo his peers Pinatubo and Earthlight in their new career: his third dam is none other than Shamardal’s illustrious grandam Helen Street. To double down 3x3 on an Irish Oaks winner by Derby hero Troy would hardly seem a formula calculated to produce a thoroughgoing miler like Victor Ludorum, who just flattened out into third when making the family’s compulsory Jockey Club bid.

sons even of a sire of sires will succeed or fail. Tributaries of Shamardal spread far from the mainstream: Bow Creek’s son Breizh Eagle was Classic-placed in France; sons of Shamardal lately accounted for two in four runnings of the G1 Turnbull Stakes (Smokin’ Romans by Ghibellines, Kings Will Dream by Casamento); and Captain Sonador, despite his early loss, managed to leave G1 Stewards’ Cup winner Seasons Bloom in Hong Kong. Some of these wider footprints result from Shamardal’s early days in Australia, where Lope de Vega also enjoyed immediate success. Dubawi’s own shuttling stints produced a single stallion son, Willow Magic in South Africa, where he produced G1 winner Mk’s Pride. Al Kazeem has a G1 winner in Germany, Aspetar, while there is now even a young Dubawi stallion in the Bluegrass, Demarchelier. But the spine of his dynasty, naturally enough, has developed through more affordable options in his local market: whether sons like Time Test, or such developing branches as the one through Makfi’s son Make Believe and grandson Mishriff.

Overall, while both houses have obviously shown diversity, in essence Dubawi and Shamardal have done little to discourage the axiomatic faith of breeders in miler speed. Zarak, despite the sturdy influences operating behind his Champion dam, is the latest to corroborate with Poulains winner Metropolitan. And what happened when Dubawi –somewhat complementing the Victor Ludorum experiment with Shamardal’s maternal line – was sent a mare whose third dam was one and the same with his fourth? The net result, in Space Blues, was the dash to win the Prix Maurice de Gheest, Prix de la Forêt, and Breeders’ Cup Mile. Space Blues has since joined the other young guns alongside their sire at Darley, where Horse of the Year Ghaiyyath, five-time G1 winner Modern Games and another dasher, the Royal Ascot sprinter Naval Crown, are also extending Dubawi’s legacy into the evening of his career.

There has never yet been a stallion who left no unfinished business. It was not until his Oaks 1-2 in 2024, for instance, that Dubawi produced an Epsom Classic winner. Instructively, that was something that had never appeared within the compass of Shamardal. Yet the contrast that implies might have suggested one last fulfilment for two horses that embarked simultaneously on a path to greatness, without ever converging: namely, the discovery of some mutual synergy.

A nick was always going to prove elusive, given their parity in age, but one daughter of Dubawi who did start breeding in time to visit Shamardal has now produced Cinderella’s Dream to become a G1 winner. She has done so over 9½ sharp furlongs of grass in the United States – a fairly apt median for the variations achieved by both these horses. Dirt, admittedly, remains essentially uncharted territory; and only Dubawi, and not Shamardal, would manage the kind of G1 double he achieved on Irish Champions Day in 2023, when the juvenile Henry Longfellow won the National Stakes over seven furlongs and the four-year-old Eldar Eldarov took the Irish St Leger over 14.

characterise either Dubawi or Shamardal as merely typical of Mr Prospector and Storm Cat respectively. After all, both those patriarchs became as remarkable for versatility as for the speed tailored to their original racing environment. And, to a degree, crediting a sire line with versatility actually denies it a specific character altogether. Having started his career with Shamardal, for instance, Giant’s Causeway left as his final bequest Not This Time – whose successes at Saratoga in 2024 alone, ranged from Cogburn’s world record of 59.8 seconds over 5½ furlongs, to Next’s 22-length win over 14!

What Dubawi and Shamardal have both brought into play was something of the ‘hybrid vigour’ famously sought by Bull Hancock. Into a European gene pool that was becoming saturated with Sadler’s Wells, Dubawi supplied a precious injection of a sire tragically denied a wider footprint; while the sires of his first three dams, old-school stayers as noted, have been virtually effaced from commercial pedigrees. Shamardal, for his part, threw a European lifeline for Giant’s Causeway, who departed for Kentucky after a single season in Ireland, while the influence of his grandam’s sire Troy had soon been extinguished by his early death at just seven.

For any successful sire, origin must ultimately be interpreted through outcome. We can only evaluate the root system by observing the growth of the tree. Quite how saplings start springing up, all around, remains an abiding mystery – but one so engrossing that, really, we shouldn’t want it any other way.

For all that it is the longest-documented man-made breed of animal, there is much that is unknown, and possibly unknowable, about the thoroughbred. But that doesn’t stop us asking.

How (why, even) do sire lines emerge?

Where have they sprung from?

In charge of the awkward questions, celebrated bloodstock sage

Chris McGrath...

Neither nature nor nurture can obviously account for Chris’s interest in the thoroughbred, which has always puzzled his family. Wherever things went wrong, genetically it must trace somewhere beyond the number of generations typically accommodated by a catalogue page. (But then that’s often true of horses, too.) Though born and raised in England, his page is chiefly Irish and German. Nonetheless, his principal allegiance nowadays is to Italy: he has been going to one particular valley there, at least once a year, for more than half his life. A graduate of Oxford University, Chris was supposed to become a lawyer but was, instead, seduced by the penury and insecurity of life as a sportswriter.

During his time on The Independent, in particular, he covered many international events beyond the Turf. But while he still enjoys some other sports, notably the soccer purveyed with varying degrees of competence by Torino FC, he has become increasingly specialised with time. He has been named Racing Writer of the Year three times, and his social history of the thoroughbred, Mr Darley’s Arabian, was shortlisted in 2016 for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year. He writes regularly for the Thoroughbred Daily News.