the Organic Way

From fermenting to freezing: how to store and preserve your surplus harvest

“Perhaps the reason so many of us buy pre-grown plants is because we think we wouldn’t be able to grow them ourselves”

There’s lots in the following pages about maximising our resources. No doubt I’d be preaching to the choir if I was to wax lyrical about wasting less, but something that’s on my mind is the reputation gardening has for being an expensive, middle-class privilege. And with good reason. Bags of compost, pre-grown annuals, vegetable plugs, perennials, trees and shrubs, tools, perhaps a lawn mower, garden furniture, a wheelbarrow – not to mention the replacement costs when plants fail: it all adds up. How have we come to this? I think it’s because much of the population has lost the art of seed sowing. Forgive the generalisation, but perhaps the reason so many of us buy pre-grown plants is because we think we wouldn’t be able to grow them ourselves.

Back to resources – let’s assess. Unless you’re solely needing to tend to plants in pots, you’ve probably got soil. Now, if there’s ever a subject that gardeners like to have a moan about it, it’s very often their soil. Too sandy, too limey, too loamy, too claggy – but it’s the first on my list of free resources.

Then… if it rains, you’ve got water. If you’ve got a comfrey plant or nettles in an area of your garden, or under a nearby hedgerow, you can harvest a bucketful of leaves to make plant food. If you collect your garden waste and veg peelings, and combine them with cardboard and newspaper, then you’ve got the makings of compost to help with the aforementioned soil problems.

Now for the most precious natural resource of all: seeds. Many are freely available. I’ve been known to gather the odd pod from my local park and save seed from the plants I grow each year. But you will also make two types of investment: one fiscal and one of friendship. Organic seeds are not expensive; you get masses in a pack and, if you join up with a friend, you can share them out. As time goes on, your collection will build and, before you know it, your annual gardening bill will be negligible. Not all seeds need to be sown under glass and pricked out. Many can be scattered. It’s not difficult or expensive to get started.

I’d love seed sowing to become a life skill again. And the curious among us will build our organic horticultural knowledge from this starting point, as the generations before us did.

Fiona Taylor Chief executive

Jules Duncan shows

Don’t overlook the cracks and crevices in your garden, writes Alice Whitehead

If traditional composting is too much like hard work, our experts share tips on more ‘hands-off’ methods

How The Greening Campaign has helped more than 20 communities tackle climate change at local level

Rachel de Thample on the art of fermentation to make vegetables healthier and longer lasting

Fiona

chats to ecologist and gardener

Readers’ tips, triumphs and memories

Dr Anton Rosenfeld explores whether achocha makes a good addition to our veg patches

From isolation to pollination: Catrina Fenton on the vital work of the HSL this summer

Our experts share their knowledge and advice

Find projects, groups and gardens local to you

Pauline Pears looks at maximising yields and longevity of our harvests

Tim Lang on why we should all be growing our own

Alice Whitehead Communications officer

Dr Anton Rosenfeld Research manager

Organic Way is published and printed on behalf of Garden Organic by:

CPL ONE: www.cplone.co.uk

T: 01727 893 894

EDITORIAL TEAM:

Wendy Davey, Hannah Rogers, Alice Whitehead, Pauline Pears

ART EDITOR: Caitlyn Hobbs

ADVERTISING:

Caroline Harland

E: caroline.harland@cplone.co.uk

T: 01223 378 045

Catrina Fenton Head of the Heritage Seed Library

Rachel de Thample Author & culinary tutor

Jules Duncan Ryton gardener

We will consider all contributions, although we are unable to pay for them. Manuscripts, photographs and artworks are sent at owners’ risk and may not be returned. The articles in this magazine do not necessarily reflect the view of Garden Organic, nor are advertisers’ products and services specifically endorsed by Garden Organic. Garden Organic has made every effort to trace and acknowledge ownership of all copyrighted material and to secure permissions. Garden Organic would like to hear of any omissions in this respect, and expresses regret for any inadvertent error. The decision whether or not to include materials submitted for inclusion (whether advertising or otherwise) shall be entirely at the discretion of Garden Organic. No responsibility can be accepted for any products or services that are the subject of any advertisement included in this publication and Garden Organic is not responsible for any warranty or representation whatsoever with regard thereto. All text and images © Garden Organic unless otherwise indicated. While generative AI tools may be used to support the initial research of features, all information has been verified by humans, and the final text and composition crafted by the author with reference to original sources. The magazine is printed on FSC® certified paper, which is responsibly sourced, certified to have been harvested from controlled sources and produced in a responsible manner. The wrapping is made from Polycomp™. It can be disposed of on a compost heap, in a household garden waste bin, food waste bin, or you can use it to line your food waste bin.

Garden Organic brings together thousands of people who share a common belief – that organic growing is essential for a healthy and sustainable world.

Through campaigning, advice, community work and research, our aim is to get everyone growing ‘the organic way’.

Patron: His Majesty The King

President: Professor Tim Lang, PhD, FFPH

Chair: Angela Wright

Vice-Chairs: Mark Mitchell and Joe McIndoe

Treasurer: Keith Arrowsmith

Garden Organic members play a vital role in supporting our charity’s work. You could get even more involved in helping us to spread the word about the many benefits of organic gardening by:

l Joining our Heritage Seed Library

l Making a donation

l Volunteering

To find out more – or for any other enquiries:

T: 024 7630 3517

E: enquiry@gardenorganic.org.uk

W: www.gardenorganic.org.uk

Our members’ magazine is published three times a year. We always love to hear our members’ news, views and organic gardening tips.

To contact the Editor: E: editor@gardenorganic.org.uk

P: Editor, Garden Organic, Ryton Organic Gardens, Wolston Lane, Coventry CV8 3LG

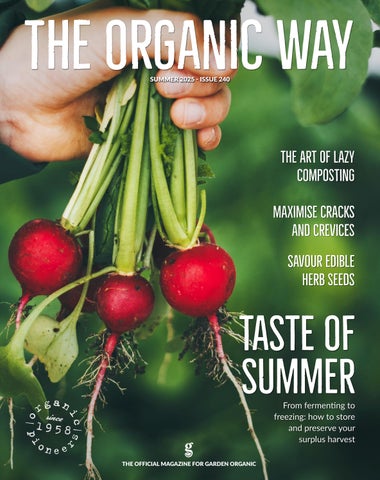

Cover Image: Radishes.

Garden Organic, the working name of the Henry Doubleday Research Association, is a registered charity in England and Wales (number 298104) and in Scotland (SCO46767)

To help keep our postage costs and emissions down, we’re planning to send the Heritage Seed Library 2026 Seed List and the autumn/winter edition of The Organic Way in the same mailing in mid-November.

This means the magazine will be a couple of weeks later than normal, and the Seed List a little earlier.

If you hold a Heritage Seed Library membership but have opted for the electronic catalogue, you will receive The Organic Way as normal, and the Seed List by email in mid-November. The HSL online request system will open at the same time, so you’ll be able to submit your choices as soon as the list arrives. Making this shift represents considerable savings for the charity and will give HSL members a longer time to browse for seeds!

If you have any questions, please contact our membership team on 024 7630 8210 or email membership@ gardenorganic.org.uk

It’s time to offer a lifeline to vulnerable bumblebees

British bumblebee numbers plummeted in 2024, and suffered their worst year since records began, according to new findings from the Bumblebee Conservation Trust.

The Trust’s national monitoring scheme shows the iconic British bumblebee – which plays a vital role in pollinating crops and wildflowers –declined by almost a quarter (22.5%) compared to the 2010-2023 average.

The charity believes this is due to cold and wet conditions from April to June 2024, which impacted colony establishment and foraging. In particular, there were worrying drops in White-tailed (Bombus lucorum s.l.) and Red-tailed (Bombus lapidarius) bumblebees, which fell by 60% and 74%, respectively, in England, Scotland and Wales.

If you want to support bumblebees, there’s still plenty you can do in your own garden:

1. Year-round food. Provide a diverse range of food sources with flowers that bloom at different times of year, including bumblebee favourites such as primrose, catmint, honeysuckle, nasturtium, mahonia and ivy.

2. Provide nesting sites. Compost heaps and bird boxes all make fantastic habitats for bumblebees. Or you could build your own B&B. Head to gardenorganic.org.uk/bumblebee-nest-box to find out more.

This issue of the magazine has been sent without an outer wrapping to reduce packaging. We hope it’s arrived with you in excellent condition but if that’s not the case please let us know by emailing editor@gardenorganic.org.uk

3. Stop using pesticides. Toxic chemicals such as neonicotinoids and glyphosate have been shown to impact foraging, egg laying, colony success and even interfere with navigation. Instead of spraying, work on building a balanced ecosystem in your garden, attracting beneficial creatures to help with pest control. Mulching can help control weeds.

4. Keep your lawn long. Long grass provides nesting sites for bumblebees, with many species nesting in the ground or in thick grass. Tangled grass stems also provide moisture and shelter from weather extremes. If your lawn has wildflowers in it, even better!

Warwick Vegetable Gene Bank has partnered with our Heritage Seed Library to help conserve precious heirloom vegetable varieties in the Midlands.

The UK vegetable gene bank, based at Warwick University, is supporting with information and seed samples from its frozen store for 10 crops, as part of our #SeedSearch project.

The two-year ‘Sowing your Seeds: Heritage Crops for a Resilient Future’ project – funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund – will conserve and pass on precious community vegetable varieties.

The bank has donated ex-commercial varieties such as ‘Cheshunt Early Giant’ lettuce, thought to date back to the 1930s, as well as underutilised crops such as purslane and orach (pictured).

The vital #SeedSearch project will help us develop knowledge of heritage crops, many of which will have been selected and bred locally for their special characteristics and resilience. They will be grown and assessed at our facilities in Ryton, so they can be maintained and shared as part of our living collection.

We’re excited to welcome a cohort of new trustees, who bring a diverse range of skills to our charity.

John Varney has worked within the charitable sector in museums and innovation, and for the last eight years has been chair of the Silk Heritage Trust. He’s an experienced gardener in his spare time –tackling four acres of pastureland on the edge of the Peak District.

Nadia Mazza and David Bond both volunteer with Garden Organic, Nadia as a Seed Guardian and David in the demonstration garden. David has more than 30 years’ experience as marketing director and managing director, and Nadia is a mathematician, working in academia for the last 20 years. Finally, Caroline Bosher is a project manager at the National Trust’s Nunnington Hall, where she’s delivered a sustainable garden redesign.

“Our new trustees will add immense value to our charity – and many of them have a deep love for gardening too,” says our chair Angela Wright. “We’re grateful that so many people are excited about what we do, and want to support the charity in its mission, governance and best practice.”

Pictured, left: a forest bug with its red legs and pointy shoulders. Right: common green shieldbug.

If you’re finding dents or distortion in your apples and pears it may be down to the ‘forest bug’ – which has a voracious appetite for fruit buds and flowers.

The shield bug is becoming an increasing ‘pest’ in the UK, and throughout the EU, causing pitting and distortion in developing fruits. Some varieties are much more prone to the bug, with ‘Gala’ and ‘Jazz’ apple varieties particularly susceptible. Pheromone traps are not effective, but research suggests blue light therapy could be, alongside attracting natural predators such as birds and earwigs.

Our Ecotalk garden at Gardeners’ World Live was complimented for its nature and food theme with a Silver Merit in the Showcase Garden category.

The judges commented that our Rooted in Nature garden was ‘packed with ways to help nature thrive’, alongside inspiring ideas to grow food. Based around our research paper, Every Garden Matters, the garden showcased how diversely planted kitchen gardens can buffer the biodiversity crisis, illustrating easy ways to maximise wildlife and manage water while growing vegetables.

The award is testament to the hard work of the garden team and designers Emma O’Neill, our head gardener, and Chris Collins, our head of organic horticulture.

A huge thank you to all our sponsors and supporters, who made the garden possible, including Ecotalk, Viridian Nutrition, Evengreener, Everedge, Breedon Aggregates and Rolawn. Special thanks to Wildwater for creating a beautiful pond, Melcourt for its high-quality peat-free compost and The Wildlife Community for the giant bug hotel and selection of wildlife habitats.

Organic farming in Scotland is outpacing the rest of the UK with a 11.8% rise in land designated for organic growing. According to new Defra figures, interest in organic growing and demand for organic land has increased in Scotland from 92,500 hectares to 103,500 hectares. In comparison, England and Wales are failing to meet demand for organic food sales, which have doubled in the last 12 years, with just 3% of farmland under organic standards in England and 4.3% in Wales.

We’re excited to be launching a new series of Members’ Days to give exclusive access and insight into a variety of organic gardens at our Growing Partners across the UK. These growing spaces commit to growing without pesticides, using peat-free compost and many are conserving Heritage Seed Library varieties. The first event will take place on Sunday 10 August at Nant-y-Bedd, a 10-acre organic garden and woodland in the Brecon Beacons National Park. The day will feature a guided tour with creator Sue Mabberley. Future events will be held at Castle Bromwich Hall & Gardens and Nunnington Hall – with more to be announced! For further details please visit gardenorganic.org.uk/events.

Innovative food initiatives are high on the menu in Wales, as the Welsh Government publishes its community food strategy. The publication has championed the pivotal role of Local Food Partnerships in creating a more sustainable and resilient food system. One project supported by the food partnership is ‘Welsh Veg in Schools’,

which suggests 25% of all vegetables used in primary school meals in Wales could be locally grown and organic by 2030.

Our CEO Fiona was delighted to attend a celebration at the Royal Caledonian Horticultural Society (The Caley) marking 200 years since being granted a Royal Charter and its role in promoting and advancing horticulture across Scotland. Her Royal Highness The Princess Royal officially opened a new teaching glasshouse at Saughton Park, purpose-built to support its expanding education programme.

We’re delighted our associate director of science Bruce Pearce has been made honorary research fellow at Coventry University. And congratulations also go to our trustee Catherine Dawson, senior associate at Melcourt, who’s been awarded the prestigious Veitch Memorial Medal, in recognition of her outstanding contributions to horticulture, sustainability and soil science, particularly peatfree compost.

Our 2025 AGM will take place online at 6pm on 4 September. See page 17 for full details.

Thanks to your generous donations we exceeded our 20K target for our Big Give Green Match Fund in April. Your donations mean our Heritage Seed Library can continue its vital work conserving the heritage seeds of the future. If you didn’t get chance to donate, go to gardenorganic.org.uk/donate.

Come and join us at the Yeo Valley Organic Garden Festival between 18-20 September. Our North Somerset Master Composters will be on hand with composting advice – and Garden Organic members can get discounted entry via the click down menu at yeovalley.co.uk.

Spread the word about Garden Organic and our work by letting people know about us. We would be very grateful if you could refer and recommend us to friends, family and colleagues. Share our website address at gardenorganic. org.uk and our social media feeds @gardenorganicuk, or get in touch by emailing membership@ gardenorganic.org.uk and we can send out some promotional material to share.

There are many reasons for growing your own food, not least to feed yourself and improve the diversity of your diet. But growing vegetables also allows you to avoid certain inputs and enhance biodiversity within your growing space.

While it can be difficult to be completely self-sufficient from your garden or allotment, there is research into how much we could grow. One paper suggests that in Sheffield (within city green space such as parks, gardens, roadside verges and woodlands) the available space equates to more than four times the current per capita footprint of commercial horticulture (Edmondson et al. 2020).

It’s difficult to say how desirable it would be to dig up our urban parks and verges, but the team also looked at gardens and allotments in Luton and Milton Keynes. This suggested that enough fruit and vegetables could be grown in the area to supply all citizens for 30 days (Grafius et al. 2020).

Others have reviewed international literature (Mead et al. 2024) and, although findings are mixed, urban agriculture makes a modest and positive contribution to food security by facilitating the availability of and access to fresh fruit and vegetables. Another international review paper looked at yields from urban areas and compared them with commercial production and found them to be similar –although cucumbers did not perform well (Payen et al. 2022).

But even one household can contribute. A further study (Gulyas and Edmondson 2024) suggested the median year-round household self-sufficiency was 51% in vegetables, 20% in fruits and 50% in potatoes. This was equivalent to 6.3 portions of fruit and vegetables, which is 70% higher than the UK national average. This home production accounted for half of each household’s annual five-a-day fruit and veg requirements. There were also added benefits, in that waste was also negligible, about 0.12 portions per day, which is 95% lower than the UK average.

Gardener Jules Duncan, based at our organic gardens in Ryton, shares how you can grow fragrant, flavoursome herbs for their edible seeds

Leave a patch of lemon balm to go to seed and you could be treated to a beautiful ‘charm’ of goldfinches in the autumn and winter. They know herbs are not only good for their leaves – but also for their seeds.

While we may be familiar with growing herbs for fresh or dried leaves, and tossing the occasional borage flower into a drink, herb seeds can add a different dimension. They enhance flavour and texture and are also packed with nutrients.

And yet there’s very little difference in the growing method. You’ll need to be prepared to have the plants in-situ for longer than usual so they can flower and set seed, and leave the seedheads on the plant so they can dry naturally.

One of my favourite herbs for seed is Nigella ( Nigella sativa ) also known as black cumin – which should not be confused with Love-in-the-Mist ( Nigella damascena ), which contains damascenin and is considered slightly poisonous. Nigella sativa has everything going for it: pretty flowers that are loved by pollinating insects, decorative seedheads (though true black cumin has no hairlike bracts) and tasty seeds.

Nigella doesn’t take up much space and could easily be grown in a small pot or window box. For a larger display, sow directly into a free-draining sunny spot in mid-spring or autumn – but be aware, it likes to self-seed! Ensure the space is weed free and free draining, and rake to a fine tilth. Sow thinly and cover with only a fine layer of soil as the seeds are very small. Alternatively, sow indoors, February to March, in seed trays or modules filled with peat-free compost, and transplant once they’re big enough to handle (and after acclimatising to outdoor conditions).

The seeds will be ready to harvest in the early autumn, as soon as the seedheads have turned brown and papery. The seeds fall easily from the dried heads and can be gently toasted and sprinkled on dishes such as curry, or added to bread.

Chive seeds ( Allium schoenoprasum ) make a tasty addition to a salad, and can also be sprinkled onto a freshly baked loaf or ground up to add a delicate onion flavour to recipes. Sow thinly, directly outside in spring, either into prepared ground or into pots, and cover with a thin layer of soil. Choose a sunny spot, or light shade, and ensure the ground is free draining but moist. If you already have a clump of chives, these can be dug up and divided to create new plants and replanted. Harvest the seed in late summer, when the flowerheads turn dry and brown, and then rub the seeds out.

Fenugreek ( Trigonella foenum-graecum ) is another winner for me. Sow this member of the legume family directly in the ground between April and August, in shallow drills of 0.5cm. Leave a gap of around 5cms between plants and 20cms between rows. Harvest the seeds once the pods are dry and yellow, just before ›

Most herb seeds can be left to dry on the plant, but it’s important to be mindful of weather conditions. Too hot or too wet can destroy a crop.

Some plants, such as nigella and angelica, self-seed readily, so it’s vital to be ahead of the game to avoid losing seed. In early autumn, watch out for the seedheads turning light brown and becoming papery, then tie a paper or net bag around the flowerheads to collect the seeds before they drop.

Alternatively, cut them at the stem and hang upside down in a cool place to fully dry for a couple of weeks. Leave a tray underneath to collect the seeds or encourage them out by rubbing the dried seedhead.

The flavour of home-grown organic seeds, compared to shop bought, is far better, primarily because they will be fresher, and they have no food miles or added toxic chemicals. Plus, these easily accessible flavour powerhouses also have the added benefit of being wildlife magnets.

For advice on seed harvesting, cleaning and storage, head to gardenorganic. org.uk/seed-saving or contact us at editor@gardenorganic.org.uk to request a copy of our Seed Saving Guidelines.

1. Bergamot (Monarda didyma)

Also known as bee balm, this plant is very attractive to butterflies and bees. The seeds can be scattered on salads or used to make a tea. Sow indoors early spring, or outdoors from March to May or in early autumn.

2. Caraway (Carum carvi) Used for centuries for medicinal and culinary uses. The seeds can be added to bread and cakes. The open, easy-access umbel flowers are a great source of food for a variety of wildlife. Choose a sheltered, sunny position and sow directly April/ June, ensuring the ground is kept moist. This is a biennial plant, so will set seed in its second year.

3. Dill (Anethum graveolens) Lovely crushed and used in stews and soups, or used whole in pickles. Flowers are loved by hoverflies. Sow directly outdoors from spring to mid-summer, cover with only a thin layer of soil.

4. Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis)

The seeds can be used in teas and jams. Seedheads attracts birds, especially finches. Sow outdoors May to August or start off indoors in early spring in peat-free seed compost and plant out after the last frost.

5. Parsley (Petrosilenum crispum)

Grows well on a windowsill and outdoors. It’s a biennial, so sets seed in its second year. Crushed seeds produce a stronger parsley flavour. Sow outdoors from March to July, but be patient as they can take up to a month to germinate. Parsley seed is not recommended for pregnant women.

Sign up as a Variety Champion today

Step 1. Browse our varieties and select the one you’re most interested in or let us choose for you.

Step 2. Set up your minimum monthly donation of £25 and we’ll be in touch to take your chosen variety.

Step 3. Enjoy updates on the Heritage Seed Library and look forward to visiting, meeting the team and getting hands on nurturing, harvesting or tasting our varieties.

•

•

•

•

•

Don’t overlook the corners, cracks and crevices in your garden, writes Alice Whitehead – they provide valuable micro habitats for plants and wildlife

It can be easy for the larger elements of your garden –the trees, shrubs and manmade structures – to divert attention and become the focus. But how about looking at your growing space through a smaller lens, perhaps even the compound eyes of a beetle or a bee?

At this micro level, cavities in walls and gaps in paths become miniature worlds, all with their own diverse ecosystems. And they offer specific and sometimes unique environments for different species. Damp pockets might be home to fungi, ferns and beetles while more sun-baked spots are ideal for alpines, creeping herbs and hunting spiders.

The more habitats you can offer in your garden, the more diverse the wildlife you’ll attract. So think of your garden as a series of interconnected layers, with each tiny part playing an important role in the ecological community.

Ground-dwelling invertebrates, for example, such as spiders, beetles, millipedes and woodlice, can be easily overlooked but they make a larger contribution to garden biodiversity than any other group of ‘micro-fauna’. They help recycle plant waste, clear up ‘pest’ insects – and an average garden could be home to 2,000 different species.

In our Every Garden Matters research paper we show that gardens can have a positive contribution to nature conservation.

And with human use of land, habitat destruction and climate change causing a 13% decline in the abundance of wildlife in the UK, since 1970, small spaces become a big deal.

At these overlooked edges, even cracks in paving stones can become tiny biospheres. In a recent study1, up to 66 species of invertebrates were happily sharing pavement space with people. The researchers conducted surveys at 12 locations across Berlin and found urban pavements and cobbled streets fostered a surprising number and quantity of soil dwelling insects.

Up to 55 species of ground-nesting Hymenoptera (a large order of insects that includes sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants) were discovered hiding in the cracks and crevices, including 28 species of wild bees and 22 apoid wasps.

Similarly, in its Greener Cities guide, the Pesticide Action Network (PAN UK) celebrates resilient, native plants such as dandelions, herb Robert and chickweed that thrive in the harsh conditions of paths and kerbsides. They discovered more than 80 different species in just one street, making an important contribution to insect habitats.

So perhaps it’s time to consider your garden pathway as more than a way to get from A to B. Rather than pressure-wash so-called weeds, allow some of them to

Scan the QR code for references

be colonised to benefit nature. Or deliberately fill gaps between slab corners with plants, such as thyme. Stones, logs and flowerpots will also attract centipedes, millipedes and woodlice. And as carnivorous hunters, centipedes keep populations of snails, spiders and soft-bodied grubs under control.

Brick walls may be constructed as barriers and screens, but they also offer fortifications for flora and fauna. These linear nature reserves may have moist pockets on one side, and dry, warm habitats on the other – providing homes for insects, toads and small mammals.

The interstices between bricks can be naturally colonised by algae, mosses, lichens and ferns. But you can also mimic nature by planting up these micro habitats with tough succulents and sempervivums. Layer the top of your wall with pebbles and these can act as planting pits for rock cress (Aubretia). Or consider a vertical rockery.

Beetles will find shelter in these protected environments, particularly in winter, and may lay their eggs in cracks in spring. And black garden ants will congregate in gaps. They help aerate soil, pollinate plants and dispose of caterpillars, as well as being part of the food chain for larger creatures.

So maximise this intricate map of flora-filled fissures and green gaps in your garden and you can support a much bigger ecological matrix, playing its part in climate mitigation by nurturing wildlife, absorbing heat and filtering rainwater.

Our head gardener Emma O’Neill shows you how to create an alpine rockery in a small space

Alpine gardens were a passion of our founder Lawrence Hills –so we wanted to find a way to create a smaller version in our organic demonstration garden. We were lucky enough to have some stone slabs leftover from building work, so we smashed these into smaller pieces and added a good mix of gravel to the ground before burying the slabs vertically, close together. The aim was to create a ‘crevice garden’, which mimics rocky, mountainous terrain. This creates narrow planting pockets for alpines, as well as space for planting around the base. It’s best to avoid an area with lots of shade as alpines don’t like damp soil. As the name suggests, these plants thrive in high-altitude, mountainous regions so require well-drained soil, and an exposed sunny site with lots of air circulation.

• Pasqueflower (Pulsatilla vulgaris). With beautiful flowers and feathery hair foliage, this long-lived alpine is an absolute favourite of mine.

• Creeping thyme (Thymus praecox). A scented evergreen that grows happily in sunny crevices.

• Bellflower (Campanula portenschlagiana). Unlike most alpines, this flowers all summer long.

• Saxifrage. This pretty evergreen perennial is smothered in flowers from April until June.

working name Garden Organic

You are cordially invited to the 38 Annual General Meeting th Taking place online, at 6pm, Thursday 4 September 2025. th

Agenda

1. Introduction & welcome from the Chair of the Board of Trustees.

2 Apologies for absence

3. Approve minutes of 37 Annual General Meeting held on 5 June 2024. (available on the Garden Organic website from 7 August 2025).

4. Presentation of the 2024/25 Annual Report on Garden Organic ’s activities by the Chief Executive.

5. Presentation of the Consolidated Financial Statements 2024/25 by the Treasurer: To receive the reports of the Board and its auditors for the year ended 31 March 2025 (available on the Garden Organic website from 7 August 2025) st th

6. Adoption of the Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements 2024/25.

7. Appointment of Auditors 2025/26: To authorise the members of the Board to appoint auditors and to fix their remuneration.

8. Election of Board Members: To confirm elections to the vacancies of the Garden Organic Board of Trustees.

The business of the AGM being concluded, there will be time for questions from the floor.

Following the AGM, members will have the opportunity to put their organic growing questions to our panel of experts Questions can be asked on the day, or submitted in advance by email to membership@gardenorganic.org.uk

To book your place, please visit gardenorganic.org.uk /events/2025AGM

Attendance at the AGM is limited to Garden Organic members only. Non-members are welcome to join the organic gardening question panel

If you are unable to attend the AGM but still wish to vote, Garden Organic members are able to vote by proxy. Visit gardenorganic.org.uk /events/2025AGM to submit your vote, or call us on 024 7630 8210 to request a paper voting form.

3 July 2025 By Order of the Board Garden Organic, the working name of the Henry Doubleday Research Association, is a company limited by guarantee, registration number 2188402 and is a registered charity in England and Wales (no 298104) and Scotland (SC046767) Registered office: Ryton Gardens, Wolston Lane, Coventry, CV8 3LG

If you’re an impatient gardener and fed up with turning your heap, our experts share their tips for more ‘hands-off’ composting methods

Composting is easy – but turning the heap (to speed up decomposition) or scooping organic material into a compost bin, can be back-breaking work.

For the reluctant composter, there are some ‘lazier’ alternatives that allow the worms and microbes to do much of the work for you – while you reap the benefits of a nutritious soil conditioner.

The chop-and-drop method is the most basic example, where you simply cut back herbaceous perennials, chop them into little pieces and leave them where they drop.

It’s a method increasing in popularity with professional gardeners for the way it helps reduce weeds and retain moisture, as well as providing habitats for wildlife. Similarly, dead hedges, where deadwood is stacked in makeshift vertical piles, offers a large number of habitats and an easy, sustainable way to reuse clippings.

You might like to try making a hotbed. This uses the heat of the decomposition process to grow plants earlier in the season. The Victorians used it to grow melons and pineapples in their glasshouses. If you have

a bigger space, you could incorporate a hügelkultur bed. Loosely translated as ‘mound culture’, this method has been used since the 1960s to help decay large pieces of wood, reuse turf and use less bagged compost in growing beds.

Our expert composters have been trying out these methods in their own gardens and at our compost demonstration sites around the UK, and are keen to share their experiences.

Not only will these techniques help you recycle organic waste materials but also, thanks to their self-sustaining layers, they’ll cut back on the need for artificial fertilisers. This is because nutrients will return to the soil, improving soil health and, in turn, plant health.

If you run a business, you’ll also need to make it your business to learn efficient ways to compost this year. New legislation has made it mandatory that food waste is recycled – and, rather than pay a fee to have this taken away at the kerbside, you could try one of these free recycling systems.

North Somerset Master Composter Claire Aston shows you how to make an easy hotbed system, which can be handy for limited space

I often struggle to find enough space for composting in my small home garden, and in the past few seasons I’ve been experimenting with a hotbed in a metal raised bed.

I assemble the bed during the spring equinox each year, and fill with layers of nitrogen-rich coffee grounds, seaweed and grass clippings. (You can use animal manure, but be sure to get it from a trusted source that doesn’t use herbicides or pesticides).

It’s recommended you aim for a depth of 75cm, which will give around two to three months of heat. Layer the materials thinly, with enough browns (such as autumn leaves, shredded paper or cardboard) to hold air in the structure and prevent any anaerobic spots building up in the centre.

I cover these ingredients with a 10cm layer of compost and then plant directly into it (though be careful if you’re using fresh manure as young seedlings can be damaged because of the higher-than-usual nutrient content). It’s also possible to arrange trays of hardy vegetable seedlings on top. The heat from the composting materials helps aid growth and the whole bed is easily covered with fleece if a frost is forecast.

By midsummer, the level of the bed has shrunk by around one third, so I wait until the plants grown in situ have finished cropping and then I dig out the entire contents of this beautiful compost to mulch my garden. As a busy working mum, with limited time, I would recommend readers give hotbed composting a try.

North Somerset volunteer Master Composter Gemma Webb – who also runs an organic coaching, design and cut flower business (dialhillflowers.co.uk) – shares her tips for the chop-and-drop method

As plant growth ramps up in the spring and summer, a little-and-often approach to taming thuggish plants and weeds makes for more enjoyable garden care. In addition, deadheading of flowering plants such as dahlias and calendula also promotes further flowering.

When undertaking these tasks, the ‘chop-anddrop’ method can be used. This is where you simply chop up the removed material and add it to the surface of the soil around plants. You can also chop up the green material using a mower or hedge trimmers. This dead plant material feeds the microbes and life in your soil, which in turn supports healthy plant growth and the garden ecosystem as a whole.

Alternatively, you can drop the green material onto bark-chipping paths. The material will break down quickly and, in several years, the path material will provide a lovely autumn mulch for planting beds, rich in microbes and structure-enhancing goodness.

Chop-and-drop is ideal when plants are in full growth. In autumn and winter, old stems often provide habitats for wildlife, so leaving seedheads and standing vegetation for shelter until early spring is best to support nature in your garden.

This is a natural alternative to a boundary fence, utility screen or windbreak, and is suitable for all kinds of garden or allotment. A large proportion of woody material often ends up in green waste bins but it’s a valuable asset that can be reused

To make one, drive two rows of vertical branches or stakes into the ground (these acts as the ‘hedge’ edges), and fill the gap with woody prunings, laid lengthways. Old Christmas trees can be a great addition! As the lower branches break down, new ones can be added at the top.

Providing habitats for wildlife, its slow decomposition supports beneficial microbes, fungi and invertebrates that improve soil health. Located near a pond, frogs will also enjoy the shelter it provides.

For readers with bigger gardens, Shropshire Master Composters Louise Lomax and Colin Muddiman share their experience of making a hügel bed

We’ve been helping the children of Madeley Nursery School, Telford, with their composting – and in the past year have experimented with a hügel bed in the front garden to get pupils involved in this interesting method of composting.

Hügel beds can be as big or as small as you want but the idea is to recycle materials you have to hand, and layer them on top of logs and branches. These decay, provide nutrients and act as a sponge for moisture.

The front garden at the school consists of rough grass, so we set about taking off the turf and digging down about 50cm. This was easier said than done, as the area hadn’t been touched since the nursery was built about 45 years ago.

Bricks and stones were in plentiful supply, plus the odd crisp packet (proof they don’t degrade), but once the trench was finished, we layered branches and rotting wood over the base.

Our next layer was the turf we had cut out, which was placed upside down; woodchip and leafmould followed. In practice, you can decide what goes into these levels, depending on what you have lying around.

We mounded up the ingredients and topped them off with peat-free compost and topsoil. This should be sifted into any cracks to avoid the pile drying out. Plenty of water was added while the bed was being constructed to speed up the decomposition process and we gave it all a good soak before covering.

It’s recommended to leave the hügel bed for several

months so it can settle down, but we planted climbing beans, squash and tomatoes on top a couple of weeks after the bed was completed, and they grew well. Despite a dry period in June, the plants thrived and needed no extra watering and little regular attention. The beans produced a large harvest and were still producing in September.

Once the first mound has settled, it will need refreshing – but we think hügelkultur is a good method for schools, particularly where watering is a challenge during the school holidays. We’re now creating a second bed and planning a third so that each nursery class can be responsible for a hügel bed.

Ecologist and gardener

Becky Searle, popular for her advice on her ‘Sow Much More’ social media channels, chats to our CEO Fiona Taylor

Fiona Taylor (FT): Where did it all begin for you?

Becky Searle (BS): Having seen my grandparents and my parents gardening, I knew I simply had to do it. My parents gave me a little scrubby patch of earth around the side of our house, which was full of bugs; nothing grew there because it was in total shade. Then when I got a new house in 2018, I set up an Instagram page because I was bombarding my parents with pictures of my garden, and I think they were getting a bit bored with me. People started getting interested in my pictures. In 2020, I began to concentrate on gardening, tying in my ecology degree, and trying to educate people on the things that I felt they needed to know.

FT: Why did you select ecology as a degree?

BS: My mum’s an ecological consultant and now trains other ecological consultants. So ecology was something that I was brought up around. I wanted something that was challenging intellectually but also got me outside and allowed me to play with bugs and worms and plants; it was the perfect balance. I see my garden as an ecological laboratory because it’s a place that I get to influence what’s going on, but ultimately I don’t have the final say, and it’s nature and the ecology of the garden that’s in

control. I like to get up close and look at what’s going on and then try to figure out why those things are happening. So if I’ve got a pest in my garden, rather than treating the pest, I’ll figure out what the cause might be.

FT: I’m interested in the notion of a diagnostic approach, that you’re observing what’s going on and what the garden’s trying to tell you. Can you give us any good examples of that?

BS: I think the best example is weeds! Soil needs to have live plants in it because live plants are a big part of what the organisms in the soil eat. They’re eating root exudates, which are little packages of carbohydrates and sugars that the plants pump down through their roots to feed the life in the soil. It’s then turned into ‘glue’, which holds the soil structure together, and nutrients are released to the plants. So it’s this lovely symbiosis between plants and soil. When you have bare soil, it needs to grow plants, so weeds are a kind of ‘first response’ team as they grow really quickly.

When we see lots of weeds, we can assume our soil is lacking in organic matter. If we add some, we will see that the soil is then starting to feed on the organic matter that we’re adding and we’ll see fewer weeds because the life in the soil is starting to work in a different way.

FT: What else can we do to ensure that our soil is as healthy as it can possibly be?

BS: We need to make sure that the ecosystem in the soil is fed, but we also need to leave it alone. People are now realising that digging is not a good idea because when we dig, we break down the organic matter in the soil. A

lot of the organic matter is held in the live organisms in the soil, many of which are not able to cope with any exposure to sunlight.

FT: You talked about diagnostics and things giving you indications that life is happening or not happening. What other parts of the garden do you tend to use as your bellwether?

BS: I think pests are a key indicator of how healthy your ecosystem is. We classify things as pests if they’re a primary consumer: they eat plants. Anything else in the garden is eating the things that eat plants and so we don’t see those as pests because they’re not damaging what we want in our gardens. But if we’ve only got primary consumers – slugs, woodlice, and so on, that eat plant matter – then we have an imbalance in our ecosystem. People want to get rid of the pests, but what you’re going to do is make it more difficult for the things that want to eat those slugs to come into your garden because they’re only going to move in when there’s food. We have to think about the whole ecosystem rather than just the problem.

FT: You’ve just written a book, Grow a New Garden (Chelsea Green Publishing), which is a phenomenal achievement. Can you tell us about it?

BS: It’s designed to take you through the whole process of starting a new garden – or starting again with the space that you’ve got. The thing that I really wanted to do was try to teach people how gardens and plants work, and how the soil works so that they can trust the process and they can understand what’s going on at every stage. I talk about the importance of building a garden, not just for ourselves, but for the environment and our health; how to manage the soil, planning and designing the garden, with tips from an expert designer.

FT: Let’s just talk a bit about lawns – do you think they are a bit of an obsession in this country?

BS: I really dislike lawns! However, I do have a lawn because I have four children and they like to play in the garden. But the balance that we struck was that I sowed a load of wildflowers in the lawn – like vetch and daisies and clover and lots of things that can diversify the lawn. I think we need to get away from the narrative that we’ve been told over the past few hundred years that our lawns should be perfect. But if you want to look after a lawn, you have to start off with the soil. Most lawns are really depleted in organic matter because the grass doesn’t do an awful lot for building it up in the

Becky’s new book Grow a New Garden is an approachable guide to designing and planting beautiful, healthy gardens, no matter what space you have. It’s available at bookshop.org and other bookstores.

soil, particularly if we’re raking the thatch away. I advocate adding a small amount of organic matter regularly. That adds nutrients and kickstarts the activity in the soil. It’s better if we have a diversity of plants in the grass, which works better for the soil health. Just by adding a little bit of organic matter here and there, it can regularly build that health.

FT: You’re growing so many things from seed this year. Are you a fanatical seed saver and seed sower?

BS: Sowing from seed is so much more satisfying – and it’s a lot cheaper. Plus, you can save the seeds and use them again next year. Then things will adapt to the climate and the environment, which is much more sustainable, interesting – and fun!

This is an excerpt from an interview with Becky Searle, pictured, in the May 2025 Organic Gardening Podcast. Listen to the full interview at gardenorganic.org.uk/podcast or via Spotify, Apple podcasts, etc.

Never waste your harvest, with our guide to storing and preserving your surplus crops

Six months if frozen, one week if stored in oil in the fridge.

They can be frozen whole or in halves on a baking tray before popping into freezer bags. Defrost fully and remove the skin before using in soups, stews and sauces. You can also sprinkle halves with oil and salt, and dry on baking parchment in a cool oven for two hours and then store in oil in sterilised jars.

Best harvested early morning, before heat sets in, and when half ripe (half green and red) on the vine so they can ripen indoors.

In a clamp, given the right conditions, they can last from autumn to spring, eight-12 months in a freezer.

Surplus root crops such as carrot, turnip, swede and beetroot can be stored in a clamp. A simple method is to line the bottom of an old water butt, or similar sized container, with 15cm of builder’s sand and layer your root crops on top. Repeat in layers until full. Dig out as-and-when required.

Harvest when they have reached the desired size, and/or when leaves die back. For sweetest flavour, harvest after first frost.

TOMATOES Freeze Dry

Freeze Clamp

Six-12 months if frozen or dried, and two-three months if pickled.

Blanch in boiling water for three minutes then dunk in a bowl of iced water to stop the flavour and texture from degrading. Soak for four minutes and drain/dry thoroughly. Freeze on a baking tray before adding to resealable bags. Beans can also be pickled for longer-term storage (for method, see courgette/marrow), and peas can be dried in their pods and stored in an airtight container.

Harvest when pods are young and tender (before the bumps of seeds can be seen/felt), and in the morning when sugar levels are high.

Within one year if pickled, up to six months if dried and kept cool.

Whole onions and garlic bulbs can be cured by laying out on trays in a cool room. Once the skins and necks turn papery, plait and hang up (avoid storing near potatoes as these can absorb moisture). Small onions and cloves can also be pickled, making them taste sweeter. Cover with hot water, with a pinch of salt, and leave to cool. Top, tail and peel and leave to dry overnight, then seal in sterilised jars with a hot brine, ensuring it covers the crop (you can use malt vinegar, honey and peppercorns for the brine).

Pull onions and garlic when their leaves turn yellow. Harvest on a sunny day and leave to dry on the ground for a few days until the skin thickens.

Pickled courgettes or marrows will keep for one-two months in the fridge, three months in the freezer.

Chop and freeze (for method, see beans) or pickle by first submerging in cold water with a little salt for an hour, then heating up your pickling liquid (made from vinegar, sugar, mustard powder and spices) and adding the courgettes or marrows. Scoop into sterilised jars and seal.

Young and tender fruits, around 1020cm long for courgettes, 20-30cm for marrows. Cut at the base, in the morning, when fruits are crisp and juicy.

Cure Pickle

COURGETTE/ MARROW Pickle Freeze

Store in the fridge and use within six months.

Cabbage can be fermented by removing old leaves and shredding. Massage the leaves in sea salt (with clean hands) –using around 2% per weight of cabbage –so they release their natural juices. Pack into lidded jars along with any flavourings (such as spices, garlic, miso paste) and store away from sunlight for five days, at a cool, even temperature. Remove the lid once a day to release the gasses, and remove any scum. (Read our full feature on fermenting with Rachel De Thample, on page 30.)

During the cooler part of the day, when the cabbage head is firm with tight leaves.

Raspberries will be good to eat for 12-18 months in a freezer. Jam can last a year in a cool, dry cupboard. Once opened, jam can be refrigerated and eaten within three months.

Rinse the fruits and pat dry then lay out on a baking tray and freeze, before transferring to a zip-lock bag. Or make a quick jam, by combining 50% washed fruit with 50% caster sugar and heating in a pan. Bring to the boil and reduce until thickened, removing any scum, and pour into sterilised jars. If you strain the mixture through a sieve, you can also make a fruit syrup, which can be frozen.

Pick in the morning for tip-top sweetness, and look for uniformly coloured fruit that detaches easily from the plant. Gently twist at the stem.

CABBAGE Ferment

Freeze Preserve

Do you have any tips about storing or harvesting your crops? We’d love to hear about them. Email us at editor@gardenorganic.org.uk

We find out how The Greening Campaign has helped more than 20 communities tackle climate change at local level – and meet its indomitable founder

Eco-anxiety is real. Up to 75% of adults report being very or somewhat worried about the impact of climate change1. And more than 45% of children and young people say their feelings about climate change negatively affect their daily life and functioning2 .

In the face of this climate overwhelm, Hampshire resident Terena Plowright (pictured) has taken matters into her own hands to empower her community. She believes if people can make small environmental changes in their homes, gardens and communities, it will help them feel more invested and enabled.

Having worked on the land as a shepherdess for 35 years, Terena has sustainability in her blood. In her early life, her mum would show her how to grow her own food and was “religious about composting”. They would enjoy long walks together identifying wild plants and foraging for food.

“As a teenager I probably showed little interest, but, underneath, I now realise I was absorbing it all,” says Terena. “My mum was already aware of climate problems back then, in the 70s, and it concerned her how the environment was changing.”

After working as manager at The Sustainability Centre – an independent learning and study centre in Petersfield – Terena recognised that many ‘green’ centres, like hers, and environmental campaigns and publications, were not reaching large swathes of society.

“They were acting in an echo chamber and only appealed to ‘green’ people who were already doing green things,” she says. “Many people who felt too busy, or disengaged, or overwhelmed by climate change, were being overlooked.”

In 2008, Terena began to drop flyers through letterboxes in her hometown of Petersfield: each one outlining five environmental ‘challenges’ that homeowners could tick off. If they achieved them all, they could pop the flyer in their window.

“When I went back a few weeks later, I wasn’t expecting to see many flyers,” says Terena. “But I was

completely taken aback by the response. Houses, businesses, and even big chains such as Waitrose and Waterstones were proudly showing off their flyers. It was an emotional moment.”

By giving people clear challenges and keeping it simple, Terena found people were able to achieve big steps in a short time.

The Greening Campaign is now structured around five projects or ‘pillars’; Space for Nature, Health Impacts of Climate Change, Energy Efficient Warmer Homes, Waste Prevention and Cycle of the Seed.

At Garden Organic, we’re incredibly proud to run the ‘Cycle of Seed’ project, which focuses on food growing and food security, as well as supporting effective waste prevention activities.

We are one of a number of partner organisations, which also includes Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust and Hampshire County Council.

The campaign offers toolkits, expert support, training and workshops to build skills and help people feel they’re making a difference.

To date, the campaign has been a huge success with up to 20 communities growing their own food, reducing waste and saving energy across Hampshire. Ten of these have set up community gardens and growing spaces, and eight are growing heritage seeds, in support of our Heritage Seed Library.

Many of the communities have held seed swaps and abundance events to share gluts of fruit. An incredible £60,000 of savings have been made by reducing food waste, and 2,000-plus household items have been given a new lease of life, thanks to community-led waste prevention initiatives such as repair cafes, toy libraries, clothes swaps and driveway freecycle.

“It can be really difficult to know how to make a difference to the environment, but we’ve shown that if you just focus on your local community, change is possible,” says Terena.

“When people plant veg in their street, they can feed their family – but when they realise this can also feed a family of butterflies or bees, they see the wider impact they’re making. And from this, we can create a patchwork of green communities right across the country.”

Grandmother of 10 Lindsay Andrews has helped transform outdoor space at her local library as part of the Greening Campaign in her hometown of Ringwood, in southwest Hampshire

As a grandmother and mum, former forest school and scout leader Lindsay Andrews know what a positive effect nature can have on the next generation.

“I love seeing how children can thrive through being in the outdoor environment, and how important it is for them to gain knowledge, respect and look after nature,” she says. “But I feel a sense of guilt that the future for these young people is rather bleak, and felt I wanted to do my very small bit to try to make a difference, at least in my own community.”

Lindsay’s so-called ‘small bit’ has had a big impact on her local area. Two raised beds at her library have been transformed into vegetable beds, using the square foot method, where each square is planted with different crops and flowers, to demonstrate how to grow food in a small area.

The Greening Campaign has achieved a lot in a short space of time, partly because the team has been careful to measure its outcomes and impacts. This can be the number of square metres of land that’s been improved for nature, or the amount of C02 saved by energy-saving measures.

“People don’t want to feel they’re putting a lot of effort into a black hole, where they can’t sense what they’ve achieved,” adds Terena.

In August 2024, the campaign also adopted the nationally recognised Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment Toolkit (MWIA), with the support of health and wellbeing impacts assessor Anthea Cooke.

Research based on this toolkit has shown that the communities involved in the Greening Campaign feel a sense of control over their local actions, an increased belief in their own capabilities and a feeling of belonging.

Terena’s ethos has enabled and empowered communities to adopt simple, practical actions to tackle climate change. And the Campaign fits perfectly with Garden Organic’s objectives to help more people to grow organically, improve biodiversity and prevent

And, alongside the Greening Ringwood team, she’s also helped organise propagation, recycling and litter picking events, and a repair café with 20 regular repairers. They’ve just started a community food waste composting scheme, using a Ridan hot composter, and made 200 thermal image visits to households, giving them the knowledge and tools to make their homes warmer in winter and cooler in summer.

“It’s been fantastic to be part of a Hampshire-wide campaign, with the added bonus of being supported by a nationally recognised organisation such as Garden Organic. It’s helped people take us more seriously, and it has given us the knowledge and confidence to carry out all the activities we’ve done so far.”

waste. It’s been inspiring to see how each community has used our training, support and resources, adding their own ideas to inspire and bring local people together.

“What was once our ‘idea’ has become theirs,” add Terena. “We give the communities plenty of wiggle room to do what suits them and they focus on whatever they feel most passionate about.

“At the same time, we’ve been able to encourage adaptability. Climate change is a complex, global

issue – but at a local level it might look completely different. We need to be aware of how it can change our everyday lives from roads to properties, to health, biodiversity and food systems.”

In fact, Terena and her team have just started working with the Met Office to better inform communities about the impacts of quickly changing weather patterns, and extremes such as drought and flooding.

“One thing we can be sure of is that the climate is ever changing, and while we might want to bury our heads in the sand, we’ve got to adapt to living in a different climate while still reducing our impact. But we also need to be optimistic and find the opportunities for adaptation, whether that’s creating community energy from solar panels, or the ability to extend the food growing season and grow things from different world cultures.”

The Greening Campaign shows how community led action has the potential to make a huge difference on many levels from food security, biodiversity, waste reduction, cost savings and improved mental health.

“Climate change might seem insurmountable, but just as crossing a road is dangerous, if you cross it every day, you get used to it and begin to manage that fear. We need to stop being frightened of climate change and learn to understand it better.”

1. According to the Office for National Statistics’ Opinions and Lifestyle Survey 2021.

2. According to a 2021 article in The Lancet’s Planetary Health journal.

Planting a new herb ‘foraging bed’ at Bishops Waltham

Lindsay and Terena share their tips for tackling climate change

1. Unplug. Put your headphones away, switch your phone off and put your walking shoes on. Sit in a park, in a garden, under a tree and take in the sights and sounds, at least once a week. You’ll soon start to appreciate what’s around you.

2. Link with your local community in whatever shape or form that is and bring them together. There are so many benefits, both emotional and environmental.

3. Find your tribe. Seek out like-minded folk through eco organisations – whether that’s garden clubs, Master Composters, Waste Busters, Plastic-Free Communities, Bee Walkers (through the Bumblebee Trust) or Transition groups – and join some of them. They’re already thinking like you, and they’ll give you lots of tips and advice.

4. Prevent (not recycle) one piece of waste once a month. Instead of buying carrots in a plastic bag, buy them loose, or commit to buying one item from the refill shop. If you multiply that across the country – that’s an awful lot of plastic waste saved.

5. Understand heritage seeds – the importance of saving seeds and growing them for the future cannot be underestimated.

6. Don’t focus on the negatives around climate change. Focus on what you can do… and get on with it!

7. Join the Greening Campaign. If you live in Hampshire, get in touch at https://greening-campaign.org. Or why not create your own branch by reaching out to your town/ parish council to support you.

Rachel de Thample shares how the ancient preserving art of fermentation makes vegetables healthier and longer lasting – and encourages you to have a go

Fermentation is a transformative alchemy where raw ingredients are preserved in a manner that not only extends their shelf life, but also increases nutrients and metamorphosises flavour. Arguably, it’s the healthiest way to harness abundance and stretch the seasons. In my mind, it’s also the most exciting. The flavour transformation you get with fermentation is far more complex and evolved than with other preserving techniques like drying, bottling, or vinegar and sugar-based preserves.

What’s more, it’s incredibly easy. Sauerkraut, for instance, starts with just two ingredients: cabbage and salt. Packed into a jar, time allows a revolutionary shift.

First is the dramatic switch in texture and taste. As the bacteria converts the natural sugars and starches in the veg into lactic acid, it creates a delicious, tonguetingly tang with addictive powers. Next, the vitamin C content increases (by up to 50%) and beneficial bacteria (naturally living on the veg) is multiplied. This gives your microbiome a healthy boost and enables you to assimilate the nutrients in your food better.

One of the easiest ways to ferment vegetables is with salt. There are two main methods: dry brine and wet brine. With dry brine you finely shred (cabbages, leaves) or coarsely grate (roots), weigh the mixture and then add 2g salt for every 100g veg. This is called dry brining because all the ingredients are dry to start off with but when you add the salt it’s able to penetrate right into the cell walls of the shredded or grated veg, which draws out the natural moisture and creates a brine.

Wet brining is like using vinegar for pickling but instead of vinegar you use a mixture of salt and water. The ratio of salt to water is 4%, for example: 4g sea salt for every 100ml water. Filtered and boiled (and cooled) tap water is best to use, as water straight from the tap can contain chemicals like chlorine that will potentially kill off the good bacteria.

Fermenting fruit and vegetables is one of the safest ways to preserve food and yet so many people are scared that they’ll do something wrong. There aren’t hidden dangers with the salt-based ferment techniques outlined in my recipe. The environment created by using salt, and marrying this with packing everything into a jar and ensuring it’s airtight (i.e. anaerobic), creates conditions that are hostile to bad bacteria,

so they die off if they’re present. In the meantime, beneficial bacteria thrive and multiply in the salty, oxygen-starved mixture, boosting the gut healthfriendly offering.

The only thing that can, and sometimes does, go wrong is when everything shrinks down if you’re maturing your ferment for longer. This can create an air pocket at the top of the jar where yeasts will settle and, when exposed to oxygen, mould can grow. But hidden dangers like botulism can’t survive in a salt-based ferments if you follow the prescribed ratios of salt.

You don’t need to worry about sterilising your jars for fermentation. In fact, you want to stay away from any harsh sterilising chemicals. I simply use a jar that’s been cleaned in the dishwasher or with hot soapy water. Your jar should be at room temperature (not ›

1. Cabbage – the perfect base for kimchis and krauts, to which you can add all sorts of fun accents. Try fennel and gooseberry with lemon verbena, rhubarb and elderflower, or red cabbage and blackcurrant.

2. Carrot – pickle coarsely grated carrots with garden herbs in a 4% brine. Add fresh dill or coriander seeds.

3. Fennel – juicy and sweet, the bulb of Florence fennel is stunning pickled. The woody stems and fragrant leafy fronds make a delicious addition to sauerkraut with gooseberry or apples.

4. Tomato – simply pickle with a few crushed garlic cloves, herbs and 4% brine. It’s the perfect solution for firm, stubborn ripening or green tomatoes.

5. Turnip – a completely underrated veg, it’s a classic ingredient in kimchi. In spring, Koreans make kimchi with small, radish-like turnips. Turnips also play a starring role in one of my favourite Middle Eastern pickles: ‘torshi’, a bright pink pickle (made pink by adding a few slices of beetroot to the mix), which is spiced with za’atar.

6. Fruit – bacteria love sugar and as fruit has more concentrated sugars it gives ferments a brilliant boost. Gooseberries are my favourite example. I treat them like cucumbers by marrying them with fresh dill in a 4% salt brine. Softer fruits like summer berries, stone or orchard fruits are brilliant blended into the spice paste for kimchi.

hot) when you add your ferment as heat can kill the good bacteria, which you’re aiming to multiply. Use a classic jam jar with a lid that has a coating on the inside, as one that has exposed metal can erode when in contact with the salt (and the natural lactic acid made during the fermentation process).

Once you’ve mastered this ancient technique, you’ll never look back. The buoyancy of beneficial bacteria in fermented foods helps us survive. Each spoonful has billions of bacteria, which can help to replenish and diversify the populations in our gut.

And the simple act of fermenting food awakens primitive instincts, allowing us to connect with the world around us in a deeper way. My granny made sauerkraut, which led me to her German ancestry. Fermenting reunites us with ancient roots and awakens hidden histories that tell us more about ourselves.

With a background in top kitchens, working alongside the likes of Heston Blumenthal and Marco Pierre White, Rachel is an author and expert in local food initiatives, culinary tutoring and fermentation. She teaches courses at River Cottage and has penned the best-selling River Cottage Fermentation Handbook (Bloomsbury, 2020).

The word sauerkraut is German (it translates as ‘sour cabbage’) but the origins of this iconic vegetable ferment lie in ancient China. Labourers building the Great Wall of China are known to have sustained themselves (when fresh crops were unobtainable) on a diet of shredded cabbage fermented in rice wine.

Making sauerkraut is the perfect first step into fermenting: all you need is one cabbage and a big spoonful of salt. And then you can add all sorts of additions, or even, swap out the cabbage for other veg (finely shredded or coarsely grated).

INGREDIENTS (makes 500g)

400g cabbage

100g fruit or other seasonal veg. Fun combos to try: grated carrot, light green or white cabbage, fresh dill or fresh coriander seeds; red cabbage with blackberries and fresh fennel seeds or flowers; green cabbage with apple and thyme.

A handful of seasonal herbs, edible flowers, or 1tbsp spice 10g (or 2tsp) sea salt

1. Take 1-2 large outer leaves from your cabbage. Set aside for later.

2. Finely shred the cabbage and place in a large bowl. For the fruit or other veg, cut into bite-sized pieces, thin slices (or leave whole if berries or currants). Chop the herbs, pluck flowers from stems, or add spices if using.

3. Dust the salt over the mix and massage it into the veg. Give it some generous scrunching with your hands until the mixture starts to look wet.

4. Pack the mixture into a 500g jar, making it as airtight as possible. Place your reserved cabbage leaves on the top, tucking the sides in and around the mixture so it’s fully covered. Add a pinch of salt on top of the leaves and pour in enough water to cover so there’s no space in the jar. Secure the lid and set the jar on a plate to catch any bubbling juices.

5. Ferment at room temperature for two weeks, then eat or store at room temperature (a cooler spot out of direct sunlight is best) for up to a year. Check the jar every so often and top up with a pinch of salt and water right to the top to ensure there’s no space for mould to grow. Refrigerate once opened and eat within six weeks.

We love to hear from you. Send an email to editor@gardenorganic.org.uk or write to The Editor, Garden Organic, Ryton Gardens, Wolston Lane, Coventry, CV8 3LG

Members from across the UK share their triumphs, tips and gardening memories

When our children were small, we enjoyed holidays on smallholdings, addresses of which we got mainly from the HDRA/ GO small ads. It was safe and economical accommodation, friendly folk and nice locations – and some diversity of income for them. Other general personal adverts were also useful.

In the current issue, there are two pages listing local groups. I don’t see the point of regularly listing these. Why not have a general paragraph about the local groups and refer to the website for details, and use the space for something else?

Or focus these pages on one of these groups in detail for others to share and learn?

I would welcome small ads back if there is a demand.

J. Warrender, Sheffield

We would love to know if others share Jude’s view, both in terms of bringing back small ads, and reducing the local activities listing. Please share any thoughts by emailing editor@gardenorganic.org.uk or writing to Garden Organic, Ryton Gardens, Wolston Lane, Coventry CV8 3LG.

I am writing having read the article Time to chill in Issue 238.

The author claims that chill hours are anything below 7°C – however research on this is mixed, with anything below 9°C quoted in some research.

G. Kennard-Holden, Rhondda Cynon Taf

Organic gardener, and author of the above article Sally Morgan, writes: The definition of chill hours in the article was the number of hours when temperatures fall between 32 and 45°F (0 and 7.2°C). This definition has been used widely since the 1950s and was chosen here as it is a simple method that an amateur gardener with a weather station could monitor. There are many other methods. The Utah method, for example, involves assigning one chill hour to temperatures between 2.5 and 9.1°C and half a chill hour for temperatures between 1.5 and 2.4°C.

The Dynamic Method is the most advanced method. This

The article encouraging us to increase the variety of vegetables (issue 239) prompted me to share a tip about salsify.

Like other root vegetables, it can be left in the ground until ready for use. With some of mine, I used to cut the top-growth down to about 2cm and cover this with a small pile of soil. In time this produces a sweet and tender salad – like forced rhubarb, it has been deprived of sunlight and the chlorophyll has not done its usual job.

C. Sawyer, Strasbourg

uses ‘chill portions’ and assigns different weights to different temperature ranges. It allows for the fact that chilling doesn’t accumulate at a constant rate, and for interruptions as warmer temperatures can partially or completely undo any chilling that has built up.

The Dynamic method is best suited to warmer climates, where intermittent warm spells can affect dormancy. As UK winters become less predictable, it may soon provide better estimates of how fruit trees meet their chilling requirements.

ANTON ROSENFELD

Research manager

“New crops can be an acquired taste when we’ve been so used to the same flavours and textures for decades”

Dr Anton Rosenfeld reveals why a slug-resistant, spiny-fruited cousin to cucumber might be a good alternative to traditional greenhouse crops

It can be difficult for gardeners to adapt to new crops, unless new ones show a clear benefit over crops that are currently grown. But the results of our recent experiment into achocha – a cucurbit crop thought to originate from South America1 – suggest it might be well suited to our climate. This would mean it could be grown as an alternative to the more common glasshouse-grown crops such as cucumber or pepper. And, as many of these crops are also imported, these homegrown alternatives could help reduce our carbon footprint.

Achocha (Cyclanthera spp.) is also known as Bolivian cucumber, caigua, caihua, stuffing gourd, slipper gourd or climbing cucumber. It’s commonly found at altitude in the Andes, Peru and Bolivia, but it’s also widely cultivated throughout South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean2

There are two main types of achocha,

which are different species and have different shaped leaves and fruit. ‘Fat Baby’ (Cyclanthera brachystachya) has cordate leaves (shaped like a playing card spade) and grows single fruits that are covered in soft, fleshy spines. ‘Lady’s Slipper’ (Cyclanthera pedata) has palmate leaves (shaped like an open palm) and sets smooth fruits in pairs. The ‘Fat Baby’ type was trialled at our organic gardens in Ryton because it’s generally more resilient to outdoor growing conditions. Its less resilient cousin, ‘Lady’s Slipper’, is sometimes deemed more desirable, as it produces larger smoother fruits that are good for stuffing3 .

Achocha is best grown as a vertical vine, which is quite vigorous and can reach two metres high. It produces small white flowers, which are highly attractive to pollinators and beneficial insects.

The male flowers are produced in clusters The female flowers are easier to see as they are produced singly

Like most cucurbits, achocha produces both male and female flowers on the same plant. The male flowers are produced in clusters and can be quite difficult to spot if you don’t know what you are looking for. The female flowers are easier to see as they are produced singly, and the small spiny fruit develop underneath them.

These small, hollow fruits are technically berries, with an outer green shell (the mesocarp) and a fluffy white flesh (the endocarp) that also contains the seed4. The fruits are commonly described as having the texture of a pepper and the taste of a cucumber. The fruits have also been shown to contain elevated levels of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds4 .

Last year we sent achocha seeds out to 117 Garden Organic members, of which 61 returned results. The aim of this trial was to evaluate the performance and eating qualities

of achocha in a range of locations around the UK, and see if it could be a suitable alternative – in performance and taste – to cucumber or pepper.

Participants planted four plants around a wigwam after the last frost, which rapidly produced a large quantity of foliage. Most plants flowered after two months in midJuly, and fruits were ready to harvest by early to mid-August.

The 2024 growing season was cold and wet and many people remember it as the ‘year of the slug’. Although some people inevitably lost plants, many said the plants were left alone by slugs, even when everything else was severely damaged or lost.

One participant said: “Achocha was one of the few crops that didn’t get badly chewed by the slugs during this very damp growing season.”

The mean yield of fruits harvested from a wigwam of four plants was 1.8kg. This yield was achieved by the plants producing a large quantity of small fruits, with most sites producing an average of 142 fruits.

Overall, our research suggested that achocha was easy to grow (74% of participants), very productive (60%), with good slug resistance and the ability to produce a yield as far north as Glasgow in an exceedingly difficult growing season. However, there were mixed opinions on the taste. Only 44% of participants said they enjoyed eating them, 32% were neutral, and 25% expressed dislike. 42% agreed that they could make a good substitute for pepper, but only 25% said they would make a good substitute for cucumber.

Members reported that they preferred the stir-fried flavour of their achocha fruits over the raw flavour. Up to 41% rated the raw fruits as “pleasant” or “very pleasant”, but this rose to 55% once they were stir fried. The flavour also changed as the fruits aged.

We would recommend the younger, smaller fruits can be eaten raw, like a cucumber, with both the outer shell and inner flesh eaten. But, once the fruits become larger and the seeds woody, it’s best to let them continue developing. Once the white flesh dries out and the seeds fall out easily, they can be stir-fried or baked and stuffed and eaten like a pepper.