14 minute read

The Embodied Artifact Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

The human species was unique in evolving organically through its technological extensions: The body itself is only human by virtue of technology: the human hand is human because of what it makes, not of what it is.

— André Leroi-Gourhan (2018)

Advertisement

The digital age has given rise to cognitive assemblages that not only include humans and machines, but also include the infrastructures that support their interactions.

— Katherine Hayles (2012, p9)

What we must now do is to trace the stages that have led to a liberation so great in present-day societies that both tool and gesture are now embodied in the machine, operational memory in automatic devices, and programing itself in electronic equipment.

— André Leroi-Gourhan (1993)

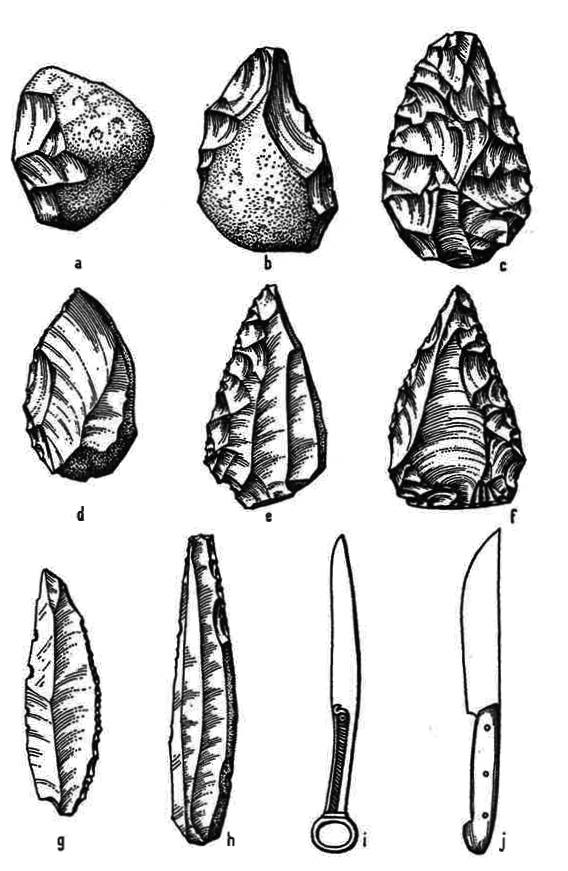

The Acheulean stone axe is one of the earliest known tools created. As far as we are currently aware, the tool can be dated back over 1.8 million years to the extinct species of humans known as Hominis. These prehistoric species were the first of their kind to show advancements in tool-making and the use of fire, their spines were adapted for upright walking, and their brain size was considerably larger than their predecessors.

As humans have evolved over the years, consciousness and technology have followed suit. The Agricultural Revolution that took place around 10,000 BCE transitioned us from our hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled farming and agriculture. The Scientific Revolution in the 16th century then fostered logic and objectivity through the sciences. The Digital Revolution in the mid-20th century altered the way in which we interact with the world through the internet and telecommunications. And finally, we have landed on the Information Revolution with the digitization of information and the beginnings of Artificial Intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence and the Acheulean stone axe are seemingly both products of human interactions with the world but from opposite ends of the material timeline. Both are human technology which changed the way their uses interact with the world. Where is the line between machine and human? And to what extent are our minds embodied by material affordances?

Despite no known formal language, symbolism or stable culture, Hominis were able to ‘produce a stable production of tools for thousands of years.(Tomlinson, 2018, p68) The Acheulean stone axe was a testament to their resourcefulness and evolving cognitive abilities. This simple yet powerful artifact is believed by anthropologists such as Leoir Gourhan to represent the physical embodiment of the knowledge network of our prehistoric ancestors. The physical ‘meeting of body and material world’ in Leroi Gourhan’s proposition of ‘chaine operatore’ described the succession of gestures involved in the creation of Acheulean technologies. The blueprint that allowed the stone stool to be reproduced for thousands of years was embodied in the meeting of social behavoir and material conditions. The stone tool is thought to physically embody the cognition of these early hominins ‘Analysis of Acheulean tools allow us to answer questions inwards towards the brains of the tool makers and out wards towards the sociophysical environments in which the tools were created’ (Tomlinson, 2018, p60).

Katherine Hayles’ work raises parallel issues around embodied cognition, and discusses these issues in relation to the technology dominating an increasing amount of our lives today. Hayles’

92 Composting is so hot illustrates the complex interrelation of the human mind, technology and the environment through her concept of ‘cognitive assemblages.’

Adopting a post-humanist perspective Hayles (2012) illustrates how technology is not something separate from the human, but instead, human consciousness and technology have co-evolved.

Hayles (2012:9) writes that ‘The digital age has given rise to cognitive assemblages that not only include humans and machines, but also include the infrastructures that support their interactions,’’ in other words, through the concept of assemblages, Hayles (2012) argues the environment, the human and machine are ontologically intertwined. Similarly to how Uexküll argued that the subject and object can not be separated, because our subjective perception directly influences what can be known at any one given time, Hayles argues human consciousness (the subject) can also not be separated from technology (the object). Moreover, as Ingold (2022) argued that humans are embedded in the environment, with the two evolving together, Hayles similarly sees the environment, technology and human consciousness also evolving together through ‘cognitive assemblages.’

One opposing view that Hayles is challenging is technological determinism, this is where technology is naturalised in the sense that it is seen as determining an outcome separate to human consciousness. But as comparison of Axe and AI show- tools evolve with human mind, intent, purpose.

It is not that stone tools are proximities of the mind but something closer to the reverse: mind as an outgrowth of the body-stone relationship. (Tomlinson, 2018, p68).

‘All technology is communication and an extension of ourselves’ (Marshall McLuhan, 1969) that mirrors the human body: vehicles extend our feet, machines extend our hands, podcasts extend our voices etc. Electricity began a new age, wherein humanity stopped simulating the ‘external’ and began replicating the ‘internal’ - the central nervous system. AI, much like our brains, takes basic inputs in parallel structuring, and creates complex patterns of understanding and interaction:

The human doens’t simply invent tools. The tools invent the human. More precisely, tool and human produce each other. The artifacts that prosthetically expand thought and reach are what make the human human. (Colomina and Wigley, 2022, p52).

There are, however, some obvious material differences between the axe and Artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence is an explicit embodiment of cognition today. There has been a shift in the way we interact with the tools through the technological and information revolution. It’s no longer exclusively a ‘physical’ interaction with the material world but a ‘metaphysical’ interaction through nodes of digital networks. AI embodies the pinnacle of these networks of information and cognitive assemblages. The networks are not tangible entities, yet they surround us in unimaginable ways, mediating our actions and interactions. To this extent the machine embodied cognition. It’s important to acknowledge the fact that these technical systems are processing and selecting information for us, as well as acting on that information. In contrast to the axe, which in comparison can be understood as a physical tool, AI is performing and having an effect (Callon et al, 2007). It is this performativity that causes some to worry that the human is out of the loop (Murgia, 2023).

During the first summer of the coronavirus pandemic, a diary entry by K Allado-McDowell initiated an experimental conversation with the AI language model GPT-3. She compiled the conversations and published the first book to be co-created with the emergent AI. The book is called ‘Pharmako AI.’

Phenomenology of Architecture has one and runs on to two lines

The building is not a thing, but a happening.

— Martin Heideggar (2008)

Phenomenology

Walking through London’s West End the immense presence of the British Museum unavoidably comes into view. The imposing mass of the building boldly stands its ground, aware of its history and fame, and immediately demands the attention of all those who pass by. Its entrance courtyard is framed by soaring columns as it hosts a multicultural exchange of the many thousands of visitors within. Greek Revivalism carved into the tympanum juxtapose the modernity of Foster’s parametric roof. 44m tall ceilings vitalise the atrium with a flooding of natural light as a bustling atmosphere of social interactions is echoed between the containing walls. A spatial hierarchy invites visitors around the exhibitions, reflecting and reinforcing the narration of the histories on display. Through the manipulation of light and shadows, intimate spaces to heighten concentration or open rooms to inspire awe, are employed to exploit the human senses and influence the user’s phenomenology.

Phenomenology is the ‘study of the structures of experience’ (Heidegger, 1977), the awareness of the subjective reality of our everyday existence and in the built environment, how architecture can ‘shape human perception and behaviour’ (Casey, 1997).

Architecture is an interactive and malleable device that can influence the human on a societal and individual scale. It can influence spirituality, inspire creativity, produce spaces of comfort and reassure security. It is the foundation of democracy and the catalyst for revolution. Architecture is a powerful tool that can be used to exploit the human sensory experience to produce meaningful spaces. Throughout history, the phenomenology of architecture’s influence can be seen through the introduction of cathedrals – that inspired spirituality across Europe - or the towering presence of palaces – which stood as a country’s beacon of power and authority. In the 21st century, architecture is becoming increasingly influential in the battle against climate change as a focus on sustainability in construction reflects a focus on sustainable living as a collective. Understanding the phenomenology is crucial to producing a built environment that can satisfy our ontological relationship with our surroundings. Utilising the agency of materials promotes our ontological relationship with our planet helping to connect the human with our natural habitat and is rapidly transforming the way in which humans treat resources and sympathise with the ecological landscape. The use of sustainable construction methods is being employed to both tackle the impeding climate crisis and reassure the human with its innate interdependence with nature. The human is also affected on the personal scale as seen through the wider understanding of the physiological and psychological relationships with architecture:

Designing buildings with health in mind can lead to spaces that promote well-being, reduce stress, and improve quality of life.

(Sternberg, 2009)

Architecture has a profound impact on peoples’ lives, thus phenomenology should be intentionally woven throughout the inception of design. Without it, architecture risks producing spaces that feel alienating, and ultimately, create unwelcoming environments that limit the potential of the human. It is in the

96 Composting is so hot

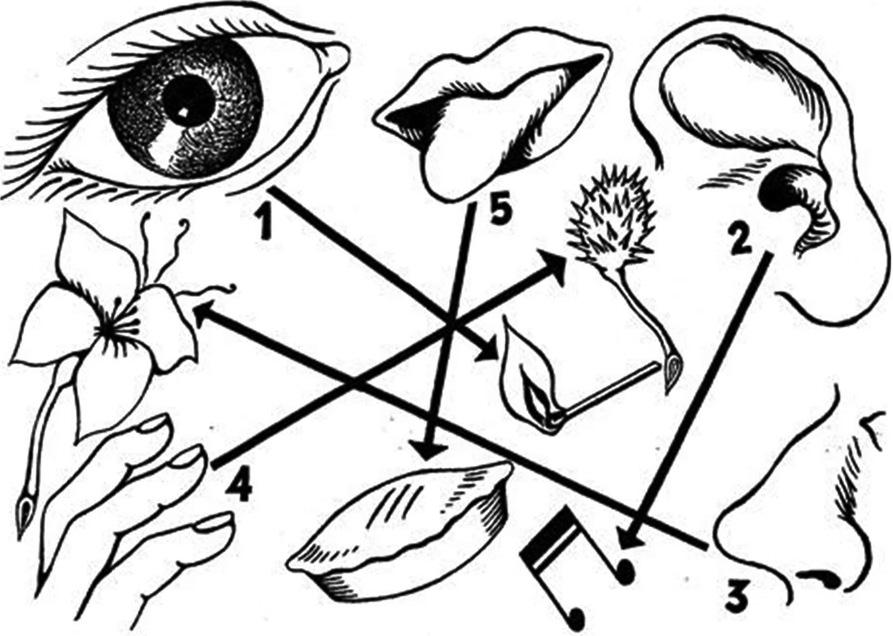

The order in which attention is captured by the human senses, as believed by cinematographer.

Morton

Leonard Heilig

(1992, p. 279-294) anthropocentric interest of humanity to produce architecture that is aware of its phenomenology.

Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles is a pertinent example of a building that engages and influences the human phenomenology in architecture. The use of stainless steel to produce wave-like facades bend and refract sunlight throughout the day, producing a dynamic and charismatic environment that invites human interaction. Observed from a distance, the building appears to dance in the landscape as its complex geometry shimmers in the sunlight. Up close, the undulations produce pockets of space that interchange in size, inviting adventure around its perimeter and eventually guiding the human into its concert halls as though the building itself is contributing to the performances within. The architecture successfully represents the creativity that it was designed to host, producing an atmosphere that amplifies the phenomenology of freedom and expression found in the world of art. In contrast to the modern deconstructivism of Gehry’s designs, the Roman Pantheon inspires a sense of awe through its mass and intricate interplay of internal light. The Pantheon’s oculus allows the sun to pierce into the central hall and glide around the curved walls, embracing the interconnectedness of nature and architecture to create a sense of transcendence for the human. Finnish architect, Juhani Pallasmaa explains light is ‘not purely a visual phenomenon, but also has an emotional impact on human beings’ (2012, p. 30). The negotiation of human emotion and architectural design is key to producing engaging and soulful environments that transcend generations to inspire cultural change and growth. It is also important to note phenomenology is not only a facet to the grandeur of public buildings but is integral at the individual scale such as the comfort and security of our homes and workplaces. A study by Kathleen Connellan and her associates found light in spaces to be imperative to the ‘biochemical and hormonal body rhythms’ that when optimised, ‘reduce depression, lessen agitation, ease pain and improve sleep’ (2013, p. 136). The phenomenology of architecture has a tangible influence on the way we exist in our built environment, and it is therefore crucial to be introduced at every design stage of every scale of architecture.

Phenomenology can also be addressed by employing sound and scale, a combination often exercised in places of worship to influence to a spiritual experience. The scale of architecture can be used to elicit a sense of reverence, frequently found in cathedrals to emphasise the magnitude of its religious significance. A Cathedral’s towering internal heights appear to reach for the heavens as though the building has a direct connection to the divine. The sheer scale of these structures can intentionally evoke emotions of humility and unease, reducing the human’s pride to succumb to the importance of spirituality. In this sense, places of worship are a rare example of non-anthropocentric architecture that focuses on the insignificance of the human and the importance of religion. Large internal volumes also produce opportunity for sound to reverberate around the halls, creating a sense of spaciousness and grandeur while heightening the significance of the speaker. Sound is key to our sensory experience of a space as it works as an invisible measurement of scale while also serving as an ontological interaction between the human the surrounding objects. The relationship between architecture and the human sensory experience of a space is crucial to the human phenomenology of the built environment, as Pallasmaa explains, ‘I confront the city with my body ... I experience myself in the city, and the city exists through my embodied experience. The city and my body supplement and define each other. I dwell in the city and the city dwells in me’ (2012, p5). Thus, it is crucial for sound and scale to be thoroughly integrated in the design of architecture in order to inform the human phenomenology of the built environment and produce satisfying spaces that encourage the engagement of the human and its ontological reality.

The phenomenology of architecture should be considered from the inception of design. The human sensory experience is continuously active and should be exploited to fuel inspiration and create meaningful spaces that can further improve our built environment. Employing the agency of materials, the influence of sound, the impression of scale and the fluidity of light, should be integral to the progress of architecture and woven throughout future developments.

100 Composting is so hot

Semiotourisme and runs on to two

Amidst the proliferation of fast media, interpretation no longer unfolds along sequential lines; instead, it follows associative spirals and asignifying connections.

— Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi (2009, p112)

the background world

Hollowness is in style; everything has become a representation of an unattainable reality. Without any directions, or any specific destination, we have become full-time tourists forced into navigating around landscapes saturated with signifying representations. This is Semiotoursim.

Picture a spiderweb with no clear centre, axis or sense of scale. Now on this model, superimpose the subject - a spider - that is aggressively weaving and re-weaving , editing and cutting, destroying and re-building upon pre-existing structures. It is a perpetual mode of intense collaboration with the spiderweb and its material qualities. In this example, structures are constantly edited much like meaning and signification mutates, evolves and displaces itself today in the semiotic world we currently find ourselves inhabiting.

Welcome to the precarious postmodern condition, but let’s talk about how we arrived here in the first place. With the rise of industrial capitalism in the early 19th century, factories and production assembly lines were the main source of generating capital through the means of manufacturing material goods. This model was dependant on workers dedicating a certain amount of time in order to complete tasks in exchange for a monetary wage.

There was clarity in what needed to be achieved in order to produce something of material. This clarity slowly turned cloudy.

At a later point when technological transformations occurred, something interesting happened. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi describes a changeover from what was once industrial capitalism into ‘semiocapitalism’; a mutation which re-shuffled its focus of production towards ‘the sphere of semiotic goods: the info-sphere.’ (2009, p. 44) The info-sphere became the landscape in which signs, media and information resided, having a direct relationship with humans who absorb and hold ability to comprehend their meaning. As digital infrastructures accelerated, so did the info-sphere together with the speed of producing signs, symbols and information creating a potent form of tension not only in the economy, but in humans trying to interpret signification.

Berardi coins two terms which relate to this tension: cyberspace relating to the ‘infinite productivity of collective intelligence in a networked dimension’ (2009, p. 44) and cybertime as the ‘mental time that is necessary to elaborate info-stimuli coming from cyberspace.’ (2009, p. 143) This contradiction between the infinite nature of cyberspace and finite of cybertime, is what he defines as the root of contemporary chaos. The age of semiocapitalism has taught us that more information does not necessarily mean more meaning in fact, the opposite, meaning becomes unreachable and unprocessable to the average human being. They are in a mutually destructive relationship.

This destructive relationship manifests itself in a particular song by Nine Inch Nails titled The Background World (2017). It contains an idea of time and its finite nature being stretched to its limits. Roughly around the fourth minute, the repetitive lyrics: ‘are you sure, this is what you want’ (2017) together with the steady instrumental rhythm suddenly come to a violent stop at which the song self destructs.

Vocals disappear altogether, and the instrumental continues to loop itself 52 times perhaps suggesting a reference to the limited amount of weeks in a year. Each loop becomes a progressively more distorted version of its predecessor, ending in an unrecognisable stream of noise bearing no relation to the original. It is possible this song is a sonic translation of what Jean Baudrillard would refer to as the mutation images or representations evolve to: the stages of the sign. (1981, p. 6) The image begins with reflecting reality through a faithful copy. It then distorts it by masking reality. At the third stage, it unravels an absence of reality, and finally at the fourth stage, announces that it bears no relation to reality whatsoever.

The simulacrum is never that which hides the truth - it is truth that hides the fact that there is none. The simulacrum is true.

(Baudrillard 1981, p. 1)

Through this constant process of imitating, the image becomes a vessel containing minimal traces of meaning, detaching itself from the original and creating something which one is unable to distinguish wether it is real or imagined. The song exists in a purely constructed hyperreality, like most of the objects, products and artefacts we see in front of us on a daily basis.

So let’s ask the question we are all sensing is present, when did reality lose meaning? In the chapter ‘The Implosion of Meaning in the Media’ (Baudrillard, 1981 p. 79) we learn that the relationship between meaning and information is sortable into the following three hypothesis:

Either information produces meaning, but cannot make up for the brutal loss of signification in every domain. Or information has nothing to do with signification. It is something else, an operational model of another order, outside meaning and of the circulation of meaning strictly speaking. Or, very much on the contrary, there is a rigorous and necessary correlation between the two, to the extent that information is directly destructive of meaning and signification, or that it neutralises them.

(Baudrillard, 1981 p. 79)

104 Composting is so hot

From the trio, the latter statement confirms the most frightening condition: with the rise of information exchange, we are not getting nearer to meaning - it is not a proportional relationship. Rather, information becomes an overly simplified means of constructing a false reality rather than exchanging any meaning. This marks the death of modernity.

Baudrillard presents traditional outdoor markets belonging to a time before modernity decayed. (1981, p. 75) With their highly centralised nature - located in the core of towns and villages around the world - outdoor markets were places where merchants would exchange highly specialised products for capital. Life revolved around them, however, at a certain point arrived a new type of markets.

Ones containing fluorescent lights, conditioned air and right angled shelving units holding vividly coloured products with long life spans printed on their front and sides. Hypermarkets - Tescos, LIDL and Asda’s - truly marked the death of modernity according to Baudrillard. They dislodge themselves from the city centres, bleeding out into metro areas - ‘a completely delimited functional urban zoning,’ (Baudrillard, 1981, p. 77) shopping malls and airports like a parasite. At a certain point - although blurry - the hypermarkets admiration of simulating the perfected version of the traditional market ends in a catastrophe - all life which at once was present in their eyes, has vanished. They exist in a reality, but one at the furthest point away from ours. They become a part of a hyperreality, a collection of entities containing no past and no future.

The photograph titled 99 cent by Andreas Gursky (1999) depicts the seriality of arrangement inside the typical hypermarket.