6 minute read

Roots and Simulacra

The enslavement of a natural form by human thought says more about political and social structures and hierarchies of human knowledge than it does about the mind itself.

— Matteo Pasquinelli (2020, p208)

Advertisement

the symbol of roots simulacrum 2: disneyland as a case study

Symbolic appropriation of the arborescent image is not limited to the more accessible trunk-branch section of a tree. Root networks, or abstracted equivalents, have been as widely adopted in the terminology of economic and psychological theory as they have in the depictions of religious and political agenda.

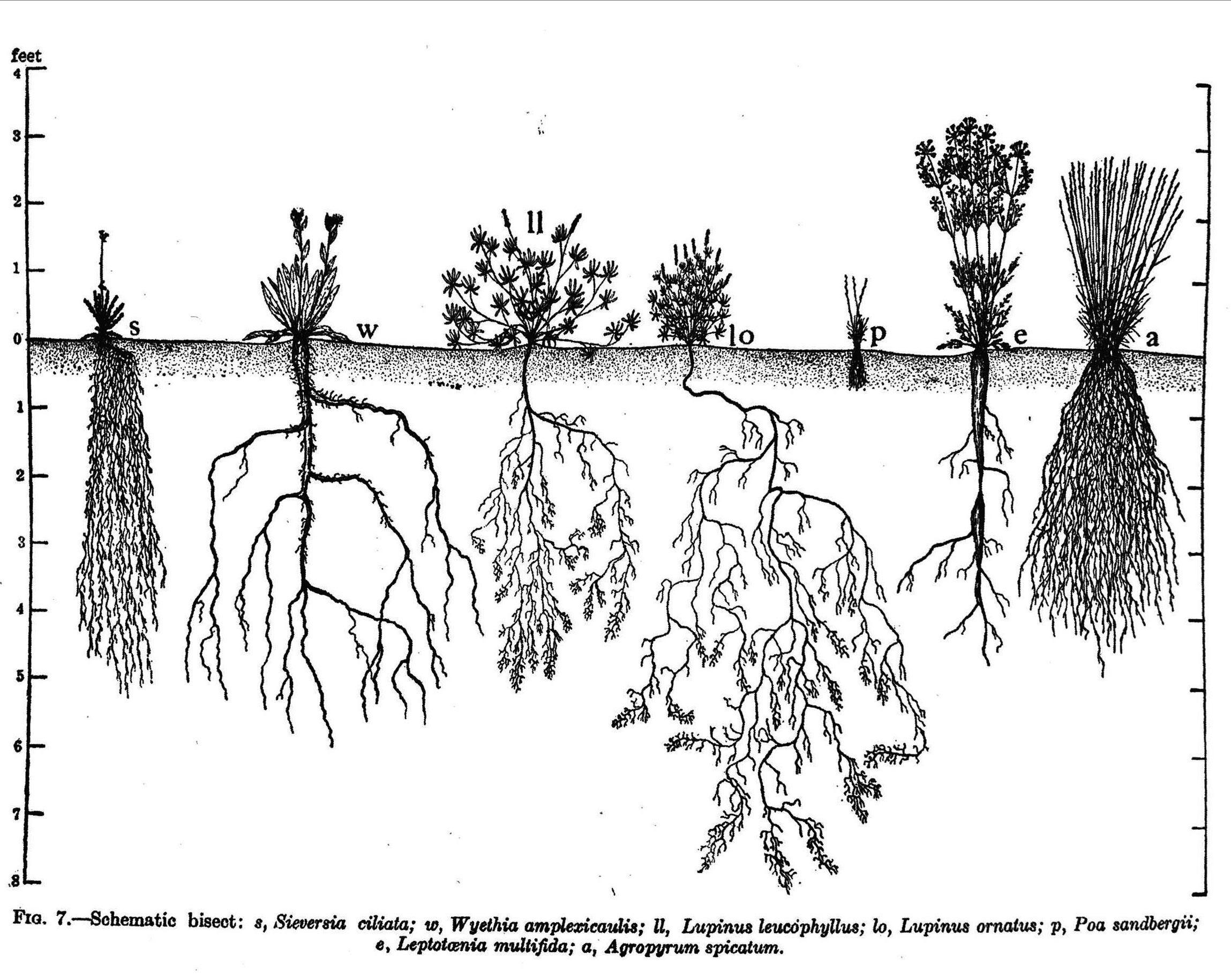

Tree roots are borrowed to represent a depth in knowledge (Fig. 1) steadiness, strength, and our connection to the earth as the human species, in most cases abridging a profound reality in favour of representative simplification.

By nature of our above-ground existence, we are far less familiar with the organisation of these buried roots than we are with the visible branches of a tree. The true arrangement of these complex networks would remain beyond our comprehension without the work of individuals such as Dr. John Weaver, who would carve out tonnes of earth to accurately map the complex root networks of hundreds of plant species, presenting us with a representation of their reality. Is the widespread acceptance of these accurate representations productive? How might we avoid the pitfalls of those representations which might appear real?

Jean Baudrillard’s idea of the ‘simulacra’ (1981) believes that in modern society, we are inundated with a multitude of signs and symbols so far removed from their original essence, that they represent a completely new version of a subject in their own right. Their uptake so widely accepted, and representation so tangible as its own entity, that a hyper-reality is created, in which a skewed representation replaces the original profound reality.

Navigating the irony of our subject, roots, we must exhume the simulacra present in even the most unabstracted of its representations. What tactics might this subject deploy to manifest its denatured reality among society?

Referring to Disneyland, Baudrillard illustrates the culmination of many simulacra (and their respective orders of disguise) (1981, p. 12), which he believes reflects one of the most powerful hyper-realities of the time. He sets out the tactics of the simulation, stating that Disneyland ‘rejuvenate(s) the fiction of the real in the opposite camp’ (p. 13).

Countless similar examples exist in our world, forty years on, and whilst Disneyland marks itself the force to be reckoned with, we must be wary of its allies.

Reinforcing those other simulacra which act undercover (including our subject, roots), Disneyland threads together its simulation, declaring it a simulation. What it cannot anticipate, however, is the effect its tactics has on those in attendance. Whilst Baudrillard claims that guests do not come in ignorance of the simulation, its popularity is so great, denatured reality so strong, it has the effect to quell those who might otherwise revolt. So, aware of their presence in a simulation, those in attendance endorse its cause. Might we uncover a similar tactic in that of our lesser known subject?

In roots, then, we face the regiments behind the sacrificial Disneyland, or specifically, those compact highly skilled regiments containing only a select few with the most sophisticated tactics - in this case, obscurity and accuracy. These regiments are followed only by the sciences. Where this unabstracted representational simulacra strikes our ignorant defence, the result is an undetectable agent exposed only through an awareness of their presence, but protected by our inability to place it.

the subject’s disguise

It is our ignorance of a profound reality that renders us an easy target. For where we previously knew nothing, a comprehensive denatured version is presented to us with an accuracy equivalent to representations typical of scientific disciplines - those that we trust without thought. The resolution of these representations convey a far greater certainty than any of their simplified symbolic counterparts. Grid lines and scale bars strike our critical weakness, evoking those aspects which we rely on for the very foundation of society. A flicker of doubt is provoked only by small stylistic interventions and errors in line weight, features not often present in the accurate representations of scientific information. If we are in search of a simulacra, it is these small mistakes only, which come close to giving away the opponent’s game. But there lies another layer to our subject’s disguise.

The critical power of the moderns lies in [their ability to] mobilize Nature at the heart of social relationships, even as they leave Nature infinitely remote from human beings’ (Latour, 1993, p. 37)

Where does this place, then, a subject like ours?

Tangled between an obscurity in our tangible world (Kourik, R. 2015) and the readily deployed ammunition of the Constitution (Latour, 1993), we are confronted with a unique case. We have acknowledged the sophistication in its disguise (our nescience paired with its accuracy), but we must also recognise its more reliable methods of manifestation.

If Nature is as agile within the Constitution as Latour (1993) gives it credit - simultaneously transcendent and distant - we are in the presence of a dangerous simulacra. Its position within Nature and in turn, the construction of Society, renders it a highly skilled ally of the simulation. The attractiveness in its previously obscured knowledge targets a most foundational aspect of human relations, to such an extent that the product is similar to the denial manifest in those attending Disneyland.

An urge to take this simulacra as reality strikes deep within our pursuit of knowledge/apparent ‘[t]otal knowledge’ (Latour, 1993, p. 36) and we want nothing other than to share this new-found reality - we have been turned by the very double agent we discovered!

simplification for intellectual gain?

What succeeds, then, despite knowledge of its falsification, is our willing dissemination of its reality. Similar to Disneyland in its ability to turn the opposition, we are recruited (albeit on a less revolutionary scale) to further strengthen its case, now complicit in the masking of a profound reality. To share this knowledge of the widely unknown is to strengthen one’s own intellectual position, whether within horticulture, architecture, or those disciplines which continue to appropriate simplified forms of root networks (unlikely!). Emerging as (often fetishised) kernels of obscure information, we knowingly promote a denatured hyperreality for our own gain. It is our own pursuit of total knowledge, then, which becomes the most powerful weapon of our opposition. Are we in control of our own simulation?

Endorsing and promoting these realities which, whether known to us or not, are far removed from a phenomena once real, is commonplace among technical disciplines. Where the opportunity arises, accurate representation of that which is beyond us strengthens our position, bringing us ever closer to total knowledge and a completion of the sciences. How best, then, to avoid this trap?

remaining in the unknown

Let us return to those simplified symbolic representations across other disciplines. Do they succeed in masking a profound reality?

They certainly do not try to convey their subjects’ essence accurately. Their deliberate ignorance is our best chance of success in these cases. Showing us that they hold no resemblance to what is real, by simplifying their form into something not natural, is their proof of allegiance. What can we learn then, from these symbolic representations, in the realm of the more technical disciplines?

A pursuit of knowledge through representation is prevalent within the sciences and other subjects which demand a visible accuracy. Drawings, photographs, and other forms of imagery strive for a profound reality, but never achieve it. Authors endorse denatured realities, falling victim to false accuracy in their representation, strengthening the case of the opposition and in turn, a hyper-reality. We cannot ever hope to side solely with our own cause. Caught unaware, we make mistakes, and where a simulacra targets our most vulnerable aspects - for example, those identified as transcendent or in the realm of a pursuit of total knowledge - we act as a double agent. So resolutely manifest among the society of this age, the simulation has infiltrated all aspects of our culture. Forty years after Baudrillard wrote his ‘Simulacra and Simulation’ (1981), our productivity continues to increases, exponentially. Forms of representation, both digital and analogue, are what we now live by and through (Haraway, 1991). Whilst the temptation is to suggest that the simulation has become our new profound reality, surrendering too soon has consequences.

Learning from those forms of representation which present themselves more clearly as denatured is productive. We can adopt similar tactics to avoid the traps set by those accurate, skilled agents of the simulation which have the ability to mask an (often obscure) profound reality. But, perhaps crucially, we should be wary of an urge to pursue total knowledge, accepting our position within a realm that should sometimes remain unknown. We should be wary of an urge represent everything.