4 minute read

Gift Giving

Now I give this thing to a third person who after a time decides to give me something in repayment for it (utu), and he makes me a present of something (taonga). Now this taonga I received from him is the spirit (hau) of the taonga I received from you and which I passed on to him. The taonga which I receive on account of the taonga that came from you, I must return to you. It would not be right on my part to keep these taonga whether they were desirable or not. I must give them to you since they are the hau of the taonga which you gave me. If I were to keep this second taonga for myself I might become ill or even die. Such is hau, the hau of personal property, the hau of the taonga, the hau of the forest. Enough on that subject.

— Marcel Mauss (1990. p9)

Advertisement

Staring at an individual that is isolated from the world, the struggle is noticeable, whether for not identifying themselves with other people that surrounds them or feeling alone. Afraid of creating connections due the fear of rejection impregnated in the society we live in. People try to fit in to please others, or to be what the society sees as ‘normal’ rather than being their own selves. At last, a stranger noticed their struggle and offered assistance, this showed they care. This unforeseen act of kindness helped them to re-evaluate the negative perceptions and inspired them to reach out more often. There is a lack of meaningful social connections and the feeling of loneliness and disconnection needs to be addressed. A deeper exploration of social fabric and the idea of community and skills exchange and how the act of giving can build the ties between one another and create a sense of connection. The concept of gift-giving as a way to establish and strengthen social relationships by embracing the ethos of giving without expecting anything in return builds a sense of belonging and community that goes beyond the beliefs of society.

The different types of acts of service or gestures - physical, emotional - have a big impact on creating connections and is fundamental in many cultures as it maintains and reinforces social relationships. Marcel Mauss, a French sociologist and anthropologist, defends that gift-giving is not purely an act of interchange, as it initiates social ties and obligations.

For Mauss, gift-giving puts people under obligations as the giver not only give an object but also part of himself, he states ‘the objects are never completely separated from the men who exchange them’ (1990). In the other hand, Lewis Hyde, takes this concept on to a greater extent, defending it is an inherent political act that provocates the capitalist attitude of egocentricity and eccentricity. However, emphasises what Mauss has said on the relationship of giver and receiver, when gifting something to someone that means offering a piece of ourselves and creating a connection to the receiver. And only when there is an understanding about the meaning of gift-giving we can then use it as tool to build relationships besides creating a more bonded community.

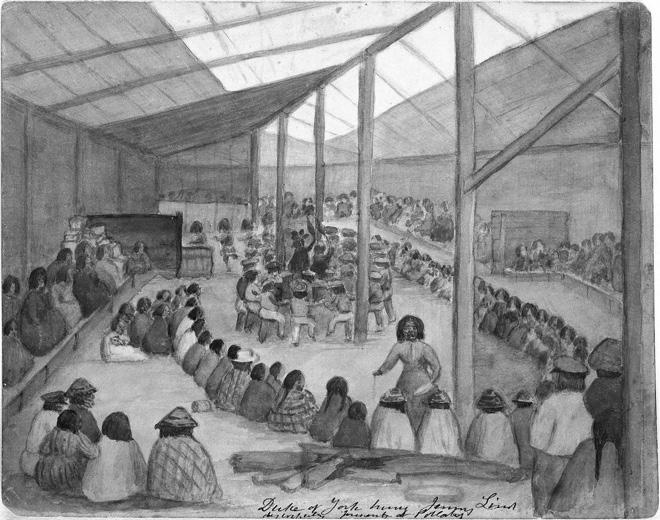

Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America practice gift-giving feasts known as potlatch. It is a system of gift-giving with social, religious and political implications, moreover, it conveys the the obligation of repaying gifts received, the obligation to give gifts and the obligation to receive gifts.

On potlatch Mauss states ‘It follows clearly from what we have seen that in this system of ideas one gives away what is in reality a part of one’s nature and substance, while to receive something is to receive a part of someone’s spiritual essence. To keep this thing is dangerous, not only because it is illicit to do so, but also because it comes morally, physically and spiritually from a person. Whatever it is, food, possessions, women, children or ritual, it retains a magical and religious hold over the recipient. The thing given is not inert.’ (1990, pg10). This feast, it is a community even, where not only they exchange material gifts but culture, knowledge and stories.

In the other hand, kula exchange happens among the Trobriand Islanders in Papua New Guinea, where each island have their own patterns and materials. Unlike potlatch, this exchange it is based on giving something without expecting to receive something back. This goes beyond purely exchanging gifts but it is a way to have a social exchange between different communities. ‘Even in the largest, most solemn and highly competitive form of kula (…) the rule is set out with nothing to exchange or even to give in return for food (…) On these visits one is recipient only, and it is when the visiting tribes the following year become the hosts that gifts are repaid with interest.’ (1990, p20). Kula and potlatch exchange’s illustrate how gift-giving can be a powerful tool in the matter of sharing values and creating a sense of belonging in community.

The disconnection and isolation many individuals experience must be addressed by encouraging gift-giving regardless if it is material, physical or emotional. Hydes wrote ‘The gift moves toward the empty place. As it turns in its circle it turns toward him who has been empty-handed the longest, and if someone appears elsewhere whose need is greater it leaves its old channel and moves toward him. Our generosity may leave us empty, but our emptiness then pulls gently at the whole until the thing in motion returns to replenish us. Social nature abhors a vacuum’ (1979, p53) - on gift-giving being a recurrent cycle and that it should spread to those in need. Although the giver might have a feeling of emptiness once they give something away as it is a cycle it will eventual come back to them and this maintains the social fabric. It is a mutual act that benefits the receiver as well as the giver.

These acts of kindness help cultivated a more generous and equitable society, and by embracing the ethos of giving without expecting anything in return it is possible to create a society that

140 Composting is so hot currently lacks the practice of generosity. It is fundamental to keep the cycle running - the more we give, the more we receive - the stronger our social relationships become. ‘The gift is a servant to forces which pull things together and lift them up’ (1979, p54).