13 minute read

The

Entangled Being Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

We are not disembodied subjects contemplating an external world, but rather are fully embodied beings who participate in the ongoing unfolding of the world.

Advertisement

—

Tim Ingold (2022, p135)

The fact is worth remembering because it is often neglected that the words animal and environment make an inseparable pair. Each term implies the other. No animal could exist without an environment surrounding it. Equally, although not so obvious, an environment implies an animal (or at least an organism) to be surrounded.

— James Gibson (2015, p35)

A spider spends its life drawing out a silk-like liquid from its spinnerets, creating a sticky web between leaves, branches and objects in which it hopes to catch its prey. Following the creation of the web, it will pause until vibrations are felt, alerting it that it has been successful in catching its prey. It will then proceed to travel into the web and wrap its prey in swathing bands of silk before either consuming the prey or leaving it for later. As the web is formed, the actions of the spider are registered in the lived space and the material world is altered.

Let us consider this web that is created by the spider to be a metaphor for the activities engaged in by all living beings throughout their lives. It’s important to note that the web is never-ending, it is never the same for any two beings, and even upon death, the matter of the being continues to interact with the environment.

The lines of the spider’s web, for example, unlike those of the communications network, do not connect points or join things up. They are rather spun from materials exuded from the spider’s body and are laid down as it moves about. In that sense, they are extensions of the spider’s very being as it trails into the environment. (Ingold, 2010, p12).

All living beings are constantly spinning their ‘web of life’ as they go about their daily activities and interact with the material world. As you zoom out and focus on the infinite number of living beings that operate within our environment, you can begin to understand just how complex this interconnected web of lives becomes. It’s this entanglement that we are looking to explore - how all living beings are entangled and embedded in the material world.

Let us begin by posing a question - is it possible to separate living beings and objects from the material world in which they exist? In the previous section, we created a metaphor for the spider’s web, with the web representing the lived experience of each being. Think of the web as a story that becomes more and more complex over time, describing the movements and interactions that the being has taken throughout its life. Now imagine combining the webs of all other living beings within the environment - this is where things start to get very interesting.

Ingold refers to this complex combination of intersecting webs as a ‘meshwork of entangled lines of life, growth, and movement’ (Ingold, 2010, p63). If you closely examined a small patch of grass in a meadow, you would discover thousands of living beings going about their daily activities, all interacting with each other and the environment in different ways. It is these interactions and how they shape everything around them that Ingold was interested in. This idea of a ‘network’ was utilised within Bruno Latour’s ActorNetwork Theory and stands to counter Ingold’s idea of a ‘meshwork.’

As highlighted by Ingold, ‘The distinction between the lines of flow of the meshwork and the lines of connection of the network is critical. Yet it has been persistently obscured, above all in the recent elaboration of what has come to be known, rather unfortunately, as ‘actor-network theory.’’ (Ingold, 2010 p11). Alongside this, Uexküll’s Umwelt theory can also be seen to be questioning the concept by assuming that ‘meaning is bestowed by the organism on its environment’ (Ingold, 2011, p64).

Moving our focus to perception, Merleau-Ponty’s understanding was not simply a matter of receiving information from the external world, but rather involved a dynamic process of engagement with that world, in which the perceiver actively explores and manipulates their environment: ‘To this extent, every perception is a communication or a communion.’ (Merleau-Ponty & Smith, 2018).

If we are embedded in the material world, then we exist in everything we make, from a primitive stone axe to a house. We need an approach to our environment and making that situates practitioners in the context of active engagement with their surroundings.

Gibson believed that perception is a process of active exploration, in which organisms use their senses to gather information about their environment. He argued that ‘Perception is exploratory...it is a way of moving about and getting into contact with the environment’ (Gibson, 1979).

His understanding of perception differs from Merleau-Ponty’s in that he viewed objects as static stimuli, forgetting the embedded nature of subjects within their constituents.

Embodied perception refers to the idea that perception is not simply a matter of passive sensing or receiving information, but is actively shaped by the physical and behavioral characteristics of the organism doing the perceiving. Being in the world is fundamentally driven by these perceptions, and the unfolding relations of stimuli within the constituents of our environment.

The environment or objective material world is in a dynamic flow of current in constant relational flux, with living beings embedded into this flow. We must reframe the assumption of the practitioner as a passive agent, separate from the material world, to one that acknowledges the entangled situated nature of the mind, body & material world.

Souls on to two lines

Materials are not passive objects waiting to be shaped by human beings, they are active agents in their own right, with their own unique properties and powers.

— Graham Harman (2018)

Materials are not passive objects waiting to be shaped by human beings, they are active agents in their own right, with their own unique properties and powers.

— Juhani Pallasmaa (2005)

materials

As one walks the streets of Islington, Amin Taha’s 168 Upper Street emerges amongst its local Georgian context. The skeuomorphic townhouse, cast from in-situ terracotta, recreates the late 19th century vernacular that once stood before. Sculpted neoclassical ornaments are reintroduced through the agency of terracotta and juxtapose the site’s heritage with its contemporary use of modern construction. Internally, CLT wall panels draw on our innate familiarity with organic materials to create welcoming and comforting living environments. Exposed materials are used to communicate with the human, producing a palpable atmosphere and sense of soul throughout the building. Leaving Islington and arriving in Canary Wharf, the soul in architecture is altogether forgotten. A metropolis landscape overwhelms the senses as glass towers overshadow walkways and concrete floors dull the sound of one’s footsteps. Materials are reduced to mere resources and their agency entirely

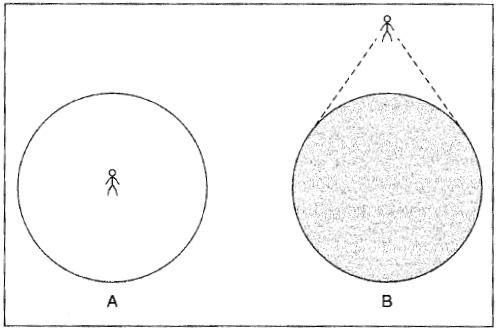

Approaches to theory and research. [Left] ‘Closed’ arboreal system; [Right] ‘Open’ rhizomatic system. (Sellers et al. 2016) abandoned. What remains is a soulless habitat devoid of architectural engagement, preserved only for commercialism.

Canary Wharf represents the growing disparity between architecture and the sense of soul in the current built environment. The theory of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) lays the foundation for a new perspective of materials and the soul of the reality we experience. Materials are identified as objects with an ‘equal right to exist,’ and with ‘the same ontological privilege as the human’ (Harman, 2011). With that privilege comes a set of ‘internal dynamics and relations’ (Harman, 2018) that make materials independent agents impacting the world in unique ways.

The challenge for architects is to work with materials in a way that recognises their inherent agency, and that creates spaces that are in harmony with the surrounding world (Ahmed, 2017)

The sterile atmosphere of Canary Wharf is an example of neglected agency as its materials are viewed solely as a means to an end.

Compare Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia to Canary Wharf’s One Canada Square; while the former carefully sculpts granite and sandstone into organic forms to create a grandeur synonymous with the spiritual preaching within, the latter is criticised for being a ‘monolithic structure that dominates the skyline and overwhelms the senses’ (Self, 2015). Despite towering over 200m and surrounded by homogenous steel structures, One Canada Square remains uninspiring and alienated. The building sees materiality as a functional tool to achieve a human-centred architecture and fails to unlock the internal properties they have to offer. In stark contrast, Gaudi’s tree-like columns and floral carvings exhibit the potential of stone as an active agent capable of interacting with the world around it. Stainglass windows manipulate light throughout the day as the building cycles through its daily circadian rhythm, glowing from the flood of morning light and calming as the sun begins to set.

The Sagrada Familia uses materials not just as static, decorative

154 Composting is so hot elements, but rather as living characteristics that welcome the human interaction and contribute to the ethereal soul of the cathedral, a quality Canary Wharf and many metropolis landscapes are devoid of. Perhaps the mundanity of One Canada Square is not the fault of architect Cesar Pelli, but is instead testament to a cultural movement toward modernism and its focus on functionality. Graham Harman argues ‘the modernist’s focus on functionality and efficiency has led to a neglect of the aesthetic and sensory qualities of materials, resulting in a lack of attention to their unique capacities and potentials’

(Harman, 2018). Post-modernist, Robert Venturi, also noted ‘Less is a bore ... because it is simply a posture and not a method. It is a lazy posture because it avoids the necessity of choice. And it is a boring posture because it denies complexity and denies the architect the possibility of creating architecture as a rich and profound experience.’ (Venturi, 1966). The use of materials as purely structural entities, rather than interactive tools of the architecture, is a common fault of the contemporary built environment and is a significant causality of its lack of soul. Grand monuments like the Palace of Versailles demonstrate the power of material agency; incredibly intricate detailing and infused use of opulent materials, like gold and marble, produce an awe-inspiring atmosphere reminiscent of the power the Palace once resembled. The capacity to reflect the monarchy’s jurisdiction through the building’s mass, adornment and materiality, is a combination Harman argues modernist architecture would struggle to compete with. Understandably, it would be a very different atmosphere if the palace were designed by Walter Gropius. Timothy Morton offers a subtle variation on material agency, suggesting ‘materials are always already in relationship with their environment. They cannot be understood as discrete entities, but are instead constantly in the process of becoming in relation to their surroundings.’ (Morton, 2007). Using this sentiment, Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe’s Farnsworth House challenges Harman and Venturi’s criticisms by demonstrating a balance between the functional capacity of materials and a clearly defined relationship with their environment. For example, enormous glass panes blur the lines between external and internal spaces, rendering the building almost weightless in appearance floating amongst the surrounding vegetation. Elevated 1.6m above the ground, the carefully assembled steel structure produces an unintrusive mass that embraces its environment, allowing the landscape to run through the building, absorbing it from all sides. Wooden floors and veneered cabinetry draw direct links to the encircling trees and in similar fashion to Taha’s 168 Upper Street, align with the human’s inherent connection with nature. Whilst it is reasonable to suggest each material has a reduced ontological impact on the human experience when compared to those found in Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, it is the combination of the selected materials that produce a powerful relationship with the landscape. The human sensory experience is therefore fully exploited, evoking a profound sense of soul and demonstrating a fine balance between material agency and modernist architecture.

One Canada Square illuminates broader issues that face much of present-day architecture; the pursuit for commercialism. Like most contemporary developments, design drivers frequently revolve around optimising space for maximised profits, as a result, much of modern architecture is concerned only with materials that can create large internal openings or endure towering heights. Material agency is therefore entirely abandoned at the benefit of commercialism, and with it so too is a building’s soul. Commercialism is just part of humanity’s wider issues of anthropocentrism and while it will serve to rapidly grow the human’s wealth and dominance of the planet, it will equally deprive the human of a soulful environment that can coexist with its ontological reality.

Architecture must not abandon the soul of the spaces it produces. It should consolidate material agency at the inception of a design project, consider user and environmental needs and focus on the sensory experience of the human. The soul of a building is what drives architecture forward and creates spaces that encourage engagement and intrigue, not serving as an addition to the landscape, but as an extension of it.

156 Composting is so hot

Vanishing Point itle: And Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

The idea that the future has disappeared is of course rather whimsical, as while I write these lines the future is not stopping to unfold. But when I say ‘future’ I am not referring to the direction of time.

— Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi (2011, p13) past follows future

Vanishing Point. The first word implies a sense of speed, the latter an end. Reading them together, suggests an erosion of something that eventually disappears completely. The future as we know it has succeeded this two-word phrase - it has escaped or rather disappeared as we desperately tried to pursue it and its counterpart - the origin. But it is important to note that the future here is not described with any reference to time, rather it is the idea of generating new possibilities, new ideas, new modes of output.

Before we imagine the vanishing point of the future, let us consider the moment when it was a state which was something held in high regard. The 1909 Manifesto Futurista (futurist manifesto) by Filippo Tommaso was the ‘avant-garde’s first conscious declaration’ (2009, p. 123) that placed trust in the future writes Berardi. It was a declaration of ‘the aesthetic value of speed.’ (2009, p. 14) With speed arrived an increases of capital through the acceleration of production assembly lines.

The idea of the future painted by the Futurists - and even the communists and fascists in the earlier part of the 20th century - was

Lost Highway, 1997

David Lynch always portrayed as a bright utopian state where life was full of possibility, progress and innovation. In the same century that the future was thought to result in utopia, saw a reversal into dystopia where the ‘result was Fascism in Italy and totalitarian communism in Russia.’ (2009, p. 18)

Where modernists in the past like Mies van der Rohe were chanting ‘less is more’ the Semiotourists of todays current contemporary society are transforming it to ‘more is more.’ This acceleration of information has increased rapidly over the past two decades. Now, more and more pressure is added on the ‘cognitariat’ (the hybrid between cognitive and proletariat as Berardi states, (2009, p. 142) as we reside in the semiocapitalism system of production.

This has become possible due to the technological advancements of the 21st century and the overproduction of visual output, devoid of any boundaries set by the traditional forms of supply and demand. When one describes that something is coming to ‘an end,’ there is an instantaneous implication of its counterpart: ‘a beginning.’ Both words have the idea of time in their roots and therefore, their relationship is assumed to have a strong linear quality of progression. One provides its meaning in relation to its counterpart and vice versa - much like the relationship between subject and object; one exists on the basis of the other. But what happens when the end does not actually take place? And when I state the end I am referring to future possibilities. Baudrillard argues that the relationship becomes destabilised to the point of exhaustion. He describes it as going through a ‘process of limitlessness in which the end can no longer be located.’ (2011, p. 59)

A point of no return is reached when things lose their end becoming perpetually lasting. One could describe this state as the inhabitation of the vanishing point of the future. Process perpetually unfold, contributing to a paradoxical condition.

Baudrillard further states: ‘either we shall never reach the end, or we are already beyond it.’ (2011, p. 60) As a side effect from this inability to locate the end, we aim to thrust the pendulum to the other side and thus double down on locating the origin point. But it is not as easy as that, as the origin point also becomes out of reach. This simple yet complex relationship struggle results in everything in our world to develop infinitely in an irregular and exponential growth with no given destination.

Baudrillard ends the chapter with the hypotheses that if there is no longer an end, then ‘he no longer knows who he is. And it is this immortality that is the ultimate phantasm of our technologies.’ (2011, p. 62)

Mark Fisher writes of a similar condition where the future - or the end - becomes something of the past, unattainable and impossible to imagine with its presence only really felt through its absence. Retrospection becomes the driving force of culture, forcing its time frame to be folded back on itself. (Fisher, 2014 p. 19) We find that cultural production becomes that of a perpetually flowing stream of repetitions, recycled, re-edited fragments of history structured in a way to hide their original influences, or as Jack Self calls this, ‘The Big Flat Now.’ (2018)

There is no perspective, no yesterday, and no tomorrow. Flatness has neither a limit, nor a horizon. It has permanently changed our relationship with time and space. As a contemporary metaphor, flatness describes how the invention of the internet has restructured global society. (Self, 2018)

What Self is saying is that any pre-existing separation between the past and the future has been reduced to an unrecognisable boundary all because of our current ability to access to large amounts of archived material as well as being able to make calculated predictions on the future. This is how the idea of flatness appeared in contemporary society.

To return to Fisher and the idea of lost futures, he uncovers the term ‘Hauntology’ (2014, p. 25) which was originally coined by Jacques Derrida in his book Spectres of Marx. For something to exist, it relies

160 Composting is so hot