20 minute read

Perception In Time d Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

We are easily deluded into assuming that the relationship between a foreign subject and the objects in his world exists on the same spatial and temporal plane as our own relations with the objects in our human world. This fallacy is fed by a belief in the existence of a single world, into which all living creatures are pigeonholed. This gives rise to the widespread conviction that there is only one space and one time for all living things.’

— Jakob von Uexküll (1957, p14)

Advertisement

‘Imagine you’re walking through a flower strewn meadow humming with insects and fluttering with butterflies. Here we may glimpse the worlds of the lowly dwellers of the meadow. To do so, we must first blow a soap bubble around each creature to represent its own world filled with the perceptions which it alone knows.’ ... He states, ‘through the bubble we see the world of the burrowing worm, of the butterfly, or of the field mouse, the world as it appears to the animals themselves, not as it appears to us. This we may call the phenomenal world or the self-world of the animal.’

(Uexküll, 1957, p5)

‘… this eyeless animal finds its way to her watchpoint [at the top of a tall blade of grass] with the help of only its skin’s general sensitivity to light. The approach of her prey becomes apparent to this blind and deaf bandit only through her sense of smell. The odour of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, works on the tick as a signal that causes her to abandon her post (on top of the blade of grass/bush) and fall blindly downward toward her prey. If she is fortunate enough to fall on something warm (which she perceives by means of an organ sensible to a precise temperature) then she has attained her prey, the warm-blooded animal, and thereafter needs only the help of her sense of touch to find the least hairy spot possible and embed herself up to her head in the cutaneous tissue of her prey. She can now slowly suck up a stream of warm blood.’ (Agamben, 2012, p46).

Let us imagine the life of a tick.

Patiently waiting on a blade of grass, ‘a tick can wait eighteen years’ (Uexküll, 1957, p17) before acting on its innate instincts to jump onto its prey, pump itself full of blood, fall to the floor, lay its eggs and die. In contrast, human beings operate on a completely different temporal timeframe, with a completely different array of senses. For humans, a single moment ‘lasts an eighteenth of a second.’ (Uexküll, 1957, p12). It is this difference in time and space that we are looking to explore within this pattern - how can we separate ourselves from our singular experience and move away from the fallacy that is the single unidimensional world?

The above quote shows Uexküll taking us on a journey through a meadow. Here, Uexküll encourages us to consider the world experiences by other living beings. Uexküll goes on to explain that when we ourselves enter a bubble of another, an insect in a meadow, our own familiar perspective of the meadow is challenged and transformed. Uexküll further demonstrates the phenomenal world through the story of the tick.

Here we see that the reality of the world is wrapped by the subject, dismantling the widely held assumption that the world we perceive is the only world that exists. Each living being is confined to their bubble of experiences which is formed from their individual perceptual sensory cues. This notion can be extended to the seemingly concrete nature of time itself. The idea being that the

Tick

Schiller, C.H., Kuenen, D.J

1957 is so hot

‘widespread conviction that there is only one space and one time for all living things.’ (Uexküll, 1957, p5) is not the case.

Umwelt theory inspired many important thinkers of the 20th century and the branch of social theory: phenomenology . Merleau-Ponty and Heiddiger inspired important ontological and epistemological thinking which led to phenomenology becoming a methodology in itself, where qualitative, subjective data, is deliberately sought after and held as valid.

Phenomenologist James Gibson believed: ‘the world which the perceiver moves around in and explores is relatively fixed and permanent, somehow pre-prepared with all its affordances ready and waiting to be taken up by whatever creatures arrive to inhabit it.’ (Gibson, 1983). For Uexküll by contrast, ‘the world emerges with its properties alongside the emergence of the perceiver in person, against the background of involved activity. (Ingold, 2011, p208). The subject is fundamental in the construction of the world, shown clearly when looking at the life of a tick. This phenological framing completely shifts the singular, athropectric view of the world which permeates western thought.

Moreover, Uexküll appears to posit humans and a tick on the same level metaphysically, meaning he does not seem to hold humans’ consciousness as superior to other insects and animals, as has long been the case within dominant branches of scientific thought and practice since the enlightenment.

The very concept of the umwelt theory is however anthropocentric, in that we are bound by our mode of communication and experience of the world. Literature, our current source of communication, tends to simplify reality by reducing the richness and complexity of objects and their relations to mere representations. Similar to Uexküll, Graham Harman in ‘Object Oriented Ontology’ asks us to flatten everything (objects and living beings) onto the same ontological plane. Here ‘everything that exists must be physical..’ Where his ideas differ is that he believes objects exist independently of human perception and possess their own inherent properties and relations. Norton challenges the notion that literature can fully capture the intricate essence of objects, their withdrawn reality, and their non-human agency. Highlighting the need to move beyond anthropocentric interpretations and recognize the independent existence and significance of objects in themselves, unmediated by human perception or literary depictions. The intangible ontological nature of our consciousness is eluded by any of our attempts to objectively conceptualise it. The same is true when conceptualizing the phenomenological experiences of a tick. We can only attempt to think beyond our own sensory world through art & poetry. It’s through these forms that we are able to ‘concretize those totalities which elude science, and may therefore suggest how we might proceed to obtain the needed understanding.’ (Norberg-Schulz, C, 1996)

Uexküll raised important ontological and epistemological questions which inspired critical thinking (beyond Darwinism) in biology, philosophy and beyond. Although there are still large parts of scientific logic which hold there is one objective reality, which can be measured and studied independently of subjective thought.

It is important to understand that we occupy a particular place in time and space, which comes with our own singular experience, and this experience cannot lead us to knowledge of everything, objectively. Remembering to consider the phenomenological experience of non-humans, as Uexküll does with the story of the tick, helps to prevent us from being so ‘easily deluded’ as to believe ‘the widespread conviction that there is only one space and one time for all living things’ (Uexküll, 1957, p11).

Anthropocentric Suicide Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

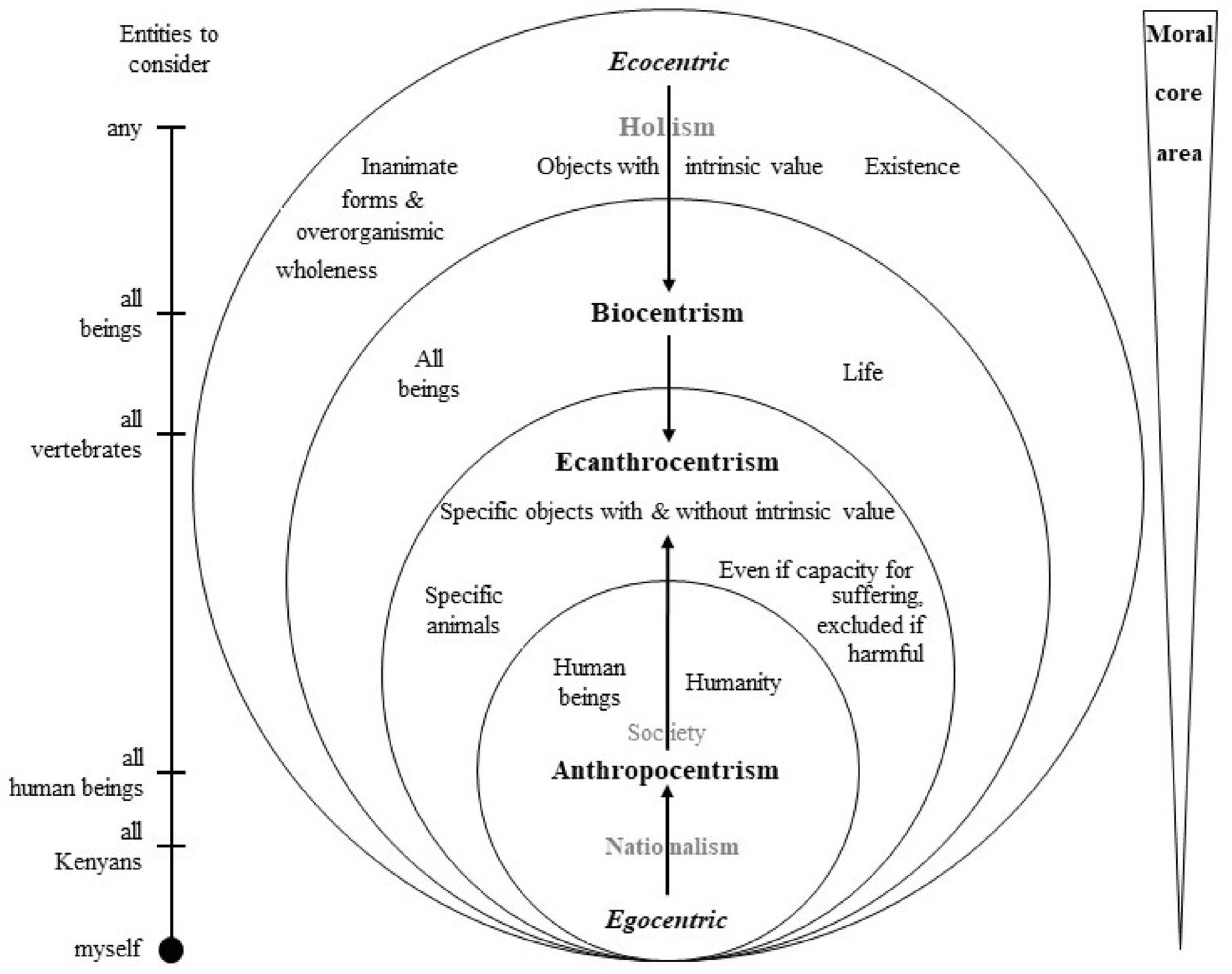

Human-centered design perpetuates a culture of anthropocentrism that places human needs and desires above the needs and desires of other beings, leading to ecological and social imbalance. (Plumwood, 1995)

— Val Plumwood (1995) sustainability

In 2022 more than 33million people were affected by the unprecedented flooding in Pakistan, 20 million people still require humanitarian assistance, 10 million of which are ‘deprived of safe drinking water’ (Unicef, 2023). Here, in England, 2022 was the ‘warmest year on record in 364-years’ (Metoffice, 2022) and ‘15 of the UK’s top 20 warmest years on record have all occurred this century –with the entire top 10 within the past decade’ (BBC, 2023).

The climate crisis threatens human existence, and yet it has been increasingly fuelled by the existence of humans. Anthropocentrism has neglected the planet’s health and has permeated our every practice, especially in the construction industry which contributes to ‘36% of global final energy consumption’ (UN Environment Programme, 2021). From laying bricks to heating our homes the residential sector in the UK is directly responsible for ‘22% of total emissions,’ of which, 45% is attributed to space heating alone (BEIS, 2020).

How Ecocentrism and Anthropocentrism Influence Human-Environment Relationships. (Rulke et al. 2020)

50 Composting is so hot

Anthropocentrism is a fundamental distortion of the relationships among entities in the universe, a distortion that has led to the ecological crisis we face today. (Morton, 2017)

Specifically, Timothy Morton refers to the failure of humanity to recognise the balanced ontology of all objects; the interdependence of all things in the universe. Failure to recognise this interconnectedness, is failure to acknowledge and address what Morton describes as Hyperobjects; objects so massive in spatial and temporal scale they are difficult to comprehend but have very real impacts on humanity. Climate change is a hyperobject woven throughout our politics, social systems and economies; it’s a sum of billions of minute actions that have culminated into a planeteffecting object. The embracing of anthropocentrism is the neglect of the agency of the objects that fill our universe and occupy our planet. In tangible terms, the embracing of anthropocentrism is the neglect of our planets health. It is now thoroughly accepted human activity is directly responsible for the climate crisis, contributing to the unprecedented levels of carbon dioxide that is unforgivingly shaping our planet’s atmosphere and all the ecosystems within it. Now, more than ever, humanity is being devastated by global warming; Concern Worldwide notes, ‘compared to the period between 1960 and 2010, the average number of floods over the last decade have increased by more than 75%. The prevalence of wildfires has doubled, and the average number of droughts each year since 2010 has increased by 57%. In 2019, the number of climate-related disasters was 237. The annual average between 1960 and 2010 was 146.’ (concern worldwide, 2022).Human behaviour can be explicitly attributed to the exponential damage of our climate, and in turn is responsible for the human suffering at the hands of global warming. If we are to tackle the climate crisis we must first address our anthropocentrism.

The construction industry is a pertinent example of anthropocentric design fuelling the looming urgency of climate change. The cement industry alone is responsible for 8% of global

CO2 emissions (BBC, 2018), and is found in almost every construction project across the world. Cement is an ingredient of concrete, a vital building material responsible for the quick construction of our cities; 15.2 million metric tons of cement was consumed in the UK in 2020 (Statista, 2022), amounting to 12.6 billion tonnes of embodied carbon. This sum is dwarfed, however, by China’s cement consumption of 2.5 billion metric tonnes in 2021, over half of the United States’ total cement consumption throughout the 20th century (4.9 billion tonnes) (Ritchie, 2023). While cement is a versatile building material often credited for its strength and durability, its overconsumption is mainly a result of its relative low cost when compared to more sustainable alternatives. Anthropocentrism prioritises cost over the ecological damage of cement, and despite a plethora of examples that showcase the successes of alternate methods, it continues to be a favoured building material. CLT is a vastly more sustainable alternative to its concrete counterpart, offering a reduction of up to 60% in embodied carbon (Dr Morwenn Spear, et al, 2021) and faster on-site installation due to prefabricated panelling. In East London, Dalston Works is a 10 storey residential development with 121 apartments and balconies alongside courtyards and restaurants. With of 3,852 cubic metres in volume (dezeen, 2023), its entire structure is manufactured from cross-laminated timber and currently stands as the largest CLT construction in the world. Dalston Work serves as an example of the mass scale CLT can achieve, and demonstrates the overreliance on cement and concrete throughout the rest of the industry. If we are to reduce our reliance on cement, we must expand our use of renewable materials and focus on producing more ecocentric construction methods.

Following a building’s completion, space heating demand is the next largest contributor to the construction industry’s overall energy consumption, and further highlights the anthropocentrism of architecture. Only recently has the idea of Passivhaus become a popular and rising form of architecture that respects the ontological relationship a building has with its environment. Passivhaus provides a series of measures that work towards a carbon neutral entity which often give back to its habitat rather than exploit it. The average space heating demand for a residential scheme in the UK is 145 kWh/ m2, over 9.5x the Passivhaus target of just 15 kWh/m2. Passivhaus achieves this significant improvement through meticulous attention to air tightness and a focus on insulation throughout the home. The use of heat pumps regulate internal temperatures in response to external weather patterns, ensuring optimal thermal comfort levels throughout the year, without requiring intense energy to quickly rise or drop temperatures. There is a harmony between the human habitat and the surrounding natural world, emphasising an ontologically equality between the human and the environment. There is also a keen attention to the agency of materials, with a particular focus on renewable resources such as timber – creating welcoming homes that draw on our innate connection with nature. Materials are not reduced to just their structural qualities, instead they are interrogated on their effects on the ecosystem, their lifespans and even locality to the scheme within which they will be a part of. Passivhaus demonstrates there are reasonable alternatives to traditional means of construction that respects the interconnectedness of architecture and the environment. In more urban landscapes, like dense cities, retrofit architecture can be used to alter previously anthropocentric buildings into ecocentric spaces moving forward. As the ecological damage of the construction of these buildings has already been established, they should be used as a foundation for further development, rather than be demolished for newbuild projects. Retrofit architecture can be built to the standards of Passivhaus and therefore can exercise an ontological approach to future architecture. Passivhaus and retrofit approaches to design can address the needs of anthropocentrism while considering the ontological importance of the objects that create our world.

In order to address the daunting inevitability of our climate crisis, humanity must first confront its anthropocentrism. The construction industry must reduce its 36% annual contribution to global carbon dioxide emissions and be used as a beacon of an ecocentric approach to the balance between humanity and its environment. Sustainable design methods like Passivhaus and Retrofit architecture, should lay the foundations for a more ontologically considered built landscape, reinstating a harmony between the human and the environment. It is in the anthropocentric interest of humanity to revaluate its position amongst natural world.

Luxury Value: And Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

In a world where everything is shopping… and shopping is everything… what is luxury? Luxury is not shopping.

— Rem Koolhaas (2001, p4)

Luxury is: Attention, ‘Rough,’ Intelligence, ‘Waste,’ Stability.’

— Koolhaas (2001, p. 57) that bag

Luxury has always been something that nobody needs. One’s survival in the world has never been dependant on it. Luxury therefore liberates it self from any formal grid work, becoming a form of loose entertainment. Its psyche is easily influenced in that it can be reversed, edited and re-shuffled at any given moment. It prefers context over object - the generated representation of a certain lifestyle that creates a strong desire of ownership. How did we end up buying into something physical based purely on its non-physical counterpart?

In the beginning of the new millennium, luxury fashion met architecture in one of the most potent forms of collaboration the world has seen. OMA/AMO and Prada begun their creative endeavour in simultaneously trying to translate the then present condition of luxury and commerce into a series epicentre stores in America. The project evolved into a series of innovative brick and mortar stores and a book documenting the process behind certain decisions and definitions.

56 Composting is so hot

Indefinite expansion represents a crisis: in the typical case it spells the end of the brand as a creative enterprise and the beginning of the brand as a purely financial enterprise. (Koolhaas, 2001, p. 4)

The owner of the Prada brand is Miuccia Prada. Her earliest example of innovation was in the reversal of luxury through a black nylon bag. Nylon which at the time was a cheap material, combined with dimpled lather - a symbol of luxury - became Prada’s earliest disturbance in the fashion world. All objects have layers of history and symbolism and what Prada realised is that the idea of luxury has nothing to do with utility or the ‘use-value’ as Marx defines it. The juxtaposition of materials fundamentally destabilised the meaning of the object, re-contextualising the material’s layers by injecting an aesthetic directed towards a classless society. This re-definition of the projects use-value and exploring its symbolic value was made clear in Baudrillard’s definition of ’sign-value.’

The work of OMA/AMO was heavily inspired by this collaboration they had with Miuccia Prada. A lot of their built projects contained references to this reversal of luxury through the material observations and use. It was all fundamentally related to the idea of material value. A prime example of a reversal was the gold leafed building in the Fondazione Prada complex designed by OMA. It screams luxury because of its symbolism related to richness, however the thing it doesn’t communicate is that it is in fact cheaper than most paints in terms of cost per square meter. This reversal of value is what’s significant here. (Laparelli, 2017, p. 1)

To return to the idea of value, we also have to return to the Marxist ideologies of use-value and exchange-value. All material objects or products contain these two values, it is what makes them be apart of the system of consumption in contemporary society. Marx defines the use-value to ‘being limited by the physical properties of the commodity, it has no existence apart from that commodity.’ (1887, p. 27)

Take for example a commodity such as steel, rice or coffee beans, they are all material things with a determined goal of use. It is important to note that the relationship between the products’ use-value and labour required to realise them are not dependant on each other.

Exchange-value on the other hand, is defined as the ‘values in use of one sort are exchanged for those of another sort, a relation constantly changing with time and place.’ (1887, p. 27) In more concrete terms, it is defined as the rate of exchange a product has when compared to other products. This boils down to exchange-value having much a higher monetary value when compared to use-value. Of course, we are aware of this as the cost to produce a t-shirt is significantly less than what it would sell for in a store. This exchangevalue is the main driver of capital generation in contemporary society.

Baudrillard used Marxist thought to build up on the ideas on the use and exchange-value of commodities. He later critiques Marx by defining these two values as a ‘rational construction that postulates the possibility of balancing out value, of finding a general equivalent for it which is capable of exhausting meanings and accounting for exchange.’ (Baudrillard, 2011, p. 9) His argument is rooted in the study of anthropology. Anthropology undermined this dialectic between the use and exchange value of products and thus ‘shattering the ideology of the market.’ (Baudrillard, 2011, p. 9)

His response to the rise in consumer culture was that it produced a third type of value a product embodies, one which subsumes the other types of value. Sign-value is the counterpart of the physical; It opens up the world of a universe which the product belongs to or tries to portray through visual signification. The lifestyle which encompasses the product. Up till now the market value of an object was stable. Sign-value disrupts this stability causing it to mutate to one which is ‘fleeting and fluid.’ (2011, p. 11) Sign-value uses our desires against us, to seduce us into purchasing a universe created by a product. Seduction contrasts the idea of production. It strips the product of its material identity, revealing an empty canvas in which symbolism can be injected into and thus altering its behaviour altogether.

Referring to the theme of seduction, Baudrillard claims ‘it was no longer a question of bringing things forward, of manufacturing them, of producing them for a world of value, but of seducing themthat is to say, of diverting them from that value, and hence from their identity, their reality, to destine them for the play of appearances, for their symbolic exchange.’ (2011, p. 21)

Seduction plays on the idea that identities and realities are always in flux, they can mutate and replace themselves. It sets desires in motion and advertising is the prime example.

A TV commercial for example never tries to persuade its viewers of the products’ use or exchange-value. That would be a highly desperate way to sell. It works on the representation of the universe the product represents, playing on the idea of desire for a different mode of lifestyle. Use-value is completely erased.

It is hard to imagine buying into a product for its use as we have fallen in love with the image of the product is trying to sell. We have thus fetishised the sign and desire more and more - the mantra of contemporary society. Is this terminal?

Lily of the Valleyn to two lines

‘Indigenous people regard all products of the human mind and heart as interrelated and as flowing from the same source; the relationships between people and their land, the kindship with the other living creatures that share the land, and with the spirit world. Since the ultimate source of knowledge and creativity is in the land itself, all of the art and science of a specific people are manifestations of the dame underlying relationships, and can be considered as manifestations of people as a whole’

— Erica-Irene Daes (1997, p. 3)

Nestled into the centre of the western flower bed of the garden, in early April a small plant, only thirty centimetres tall, can be found growing close to the fence line beside the hyacinths. It has broad green leaves that fan outwards from the stem and eight snow white flowers that droop downwards, the petals curling outwards at the ends, like the frilly sock’s schoolgirls wear in the summertime.

Wandering around the garden with my grandfather, he pointed out the sweet little plant to me; ruffling the leaves and bending down for a closer look, he said ‘Ah yes, Lily of the Valley.’

The name, Lily of the Valley, carries such a grandeur for something so small, its name professing a presence much larger and significant than its reality. Its botanical name is ‘Convalloria Majolis,’ derived from the Latin for ‘valley’ and ‘belonging to May’ (Kirby, 2011, p. 85) – etymologically marking a time when the sun shines for longer, spirits are high and days are lead with merriment.

The flower gained its popularity in the UK during the reign of Queen Victoria when it was used as a celebratory bouquet on

Whitsunday; a day in the pagan calendar that marked the return of the Holy Spirit to the Apostles (Kirby, 2011, p. 85). Its cultural significance was then maintained through its repeated description in Christianity. In the Old Testament of the Bible it is used to describe beauty and purity of the beloved in the ‘Song of Solomon’ and in early depictions of the crucifixion, lily of the valley was often used to symbolise the sadness of the Virgin Mary, leading to the flowers nickname ‘Mary’s Tears’ (1979).

My grandfather and I picked a small bunch of the lily of the valley, placing them in a rounded glass vase on the garden table. Cutting the stalks, a fragrant aroma was released; the spring-like, slightly sweet, slightly floral scent filled the air. A ripple of nostalgia swept over, the smell instantly transporting my mind back to the spring days of my youth; flowers on dining tables, laughing, eating, drinking in sweet spring smells.

I was not alone in experiencing the lily of the valley’s time altering qualities; in Virginia Woolf’s book, ‘To the lighthouse,’ the fragility and ephemeral beauty of the flower is used to convey the fleeting child-like joy in Mrs Ramsay – the lily of the valley a physical representation of her emotion.

Mrs.Ramsay, who had been arranging the knot of flowers, which she had plucked from the plants on the terrace, for Lily Briscoe, was suddenly taken herself by the beauty of the moment, and felt she had never been so happy in her life, and must do something to express her gratitude, and stood there, the picture of health, prosperity, and worldly pleasure, contemplating the entire satisfaction of her desires. (Woolf, 1927, p. 45)

Easter Sunday lunch arrived at the table; my parents, brothers, uncle, grandfather and I devouring a banquet of potatoes, meats and vegetables, chatter filling the air as we sat in the early April sun. I interjected one of the boisterous conversations to ask a little more about the ‘Lily of the Valley’ we’d discovered earlier in the day.

My mother chimed into the conversation, with a slightly puzzled expression: ‘Didn’t you know? Your great-grandmother used to grow Lily of the Valley in her allotment and then she would sell them once a year to the flower sellers on Soane Square.’

My great-grandmothers allotment was a mystical place, always mentioned, but my memory slightly cloudy, as I was only six or seven when she had to pass it onto someone new.

The entrance to allotment was behind a wooden gate, painted blue, on Queen’s Town Road – just before the Power Station. My great-grandmother’s family had lived in Battersea for generations, firmly working-class people made up of milkmen, cooks, and furriers. My family acquired the allotment four generations ago: my greatgreat-great-grandfather using it as place of storage for the horses that he was trading. They were a part of the post-World War One allotment boom, in which every third household in London has access to an allotment (Ward, 1988, p. 23). The allotment was a slice of London they got to call their own; the expansive 4m by 15m plot of land sandwiched between Victorian terraces provided not just an abundance of fruits and vegetables, but a sense of belonging to the city too (Ward, 1988, p. 27).

The ’lotty,’ which is what the allotment was called amongst our family, was mostly used to productivity grow food, especially during the war years. But one summer chancing her luck, when my greatgrandmother got off the 137 bus on the Kings Road, she asked if the Soane Square flower sellers would buy her lotty lily of the valley, and to her surprise - they said yes!

So, for the fifteen years to follow when May would come around and the allotment was blooming with the white droplets of the Lily of the Valley, my great-grandmother, great-grandfather and grandfather would collect the flowers, bunch them together at the kitchen table and form bouquets ready to deliver to Soane Square.

The lily of the valley, for such an inconspicuous little flower, held stories from generations, it’s smell unlocking histories I was unaware. Perhaps the lily of the valley is a mnemonic object, adding to the body of acquired information available for transmission, storing it for when we might be in need (Ingold, 2000, p. 134 ). Despite having never been a part of the lily of the valley cultivation in the lotty, the stories and information have slowly filtered and descended the ancestral lines, so each time I see the delicate white flower, it places a whole bank of knowledge about the lily of the valley firmly in my consciousness. Tim Ingold in his book ‘Perceptions of the Environment’ captures this exact sentiment, he says:

‘Critically, this implies that objects of memory pre-exist, and are imported into, the contexts of remembering. They are already present, in some representational form, within the native mind. Thus, far from bringing memories into being, remembering serves to bring out, or to disclose, knowledge that has been there from the start. In short, from the perspective of the genealogical model, remembering is no more generative of the contents of memory than is life activity generative of the person. And this, in turn, means that people share memories, it is not because of their mutual involvement in joint activity within a certain environment, but because their knowledge has come from the same ancestral source, along the lines of common decent. They are bound by identity not only of bodily substance and of cultural tradition, by both inheritance and heritage.’ (Ingold, 2000, p. 138)