A Language Pattern, or: How to Look at Architecture Obliquely, or: composting is so hot. For now.

Amy Young

Calum Montgomery

Camille Cervania Trinidad

Emily Bennett

Imogen Clarke

Indigo Leveson-Gower

Ines Liborio

Joseph Kohlmaier, ed.

Jules Regis

Oliver Coulton

Theo Ploutarhou

Vasil Stefanov

Poetry and Architecture

2023

A Language Pattern, or: How to Look at Architecture Obliquely, or: composting is so hot. For now.

A Manual for 21st Century Architects

Poetry and Architecture

2023

The texts in this draft publication were written by students of the Poetry and Architecture Module at the School of Art, Architecture and Design, London Metropolitan University, in 2023. In this teaching module, poetry represents a way of thinking which, in Éduart Glissant’s words, sets out to ‘invent a knowledge that would not serve to guarantee its norms in advance, but would follow excessively along to keep up with the measurable quantity of its vertiginous variances.’

The module introduces architecture students to a set of radical readings in contemporary philosophy and theory, particularly feminist, ecological and postcolonial theory, as well as forays into present thinking on language, objects, the post-human, or commoning. It then asks: how do you map these ideas back onto architecture? What are the consequences? Can architecture be rethought?

Students constructed an answer to this question through a joint writing project that resulted in a book of 30 ‘language patterns,’ a toolkit on how to look at architecture obliquely, against the grain, in the present age. But above all, Poetry and Architecture is a social space in which traditional approaches to pedagogy and teaching architecture are exploded. We have been cooking, eating, reading and thinking together. The book the students collaborated on is an example of generosity and collaboration, and a testament to what education can do if you let it. It is also brilliant in many ways. This is the last year Poetry and Architecture runs in its current form. All students receive the same grade: a First. The students made their tutor a cake with icing that read ‘Composting is so hot,’ (Haraway) but that is not why.

Joseph Kohlmaier

June 2023

vii 1 Catkin Carpet 9 2 Buildings and Permanence 13 3 Collective Cognition 20 4 Ecofeminism 1: A Manicured Garden 25 5 EcoPhenomic Pulsations 30 6 Designing through Commonism 34 7 Water 39 8 Perception In Time 44 9 Anthropocentric Suicide 49 10 Luxury Value 55 11 Lily of the Valleyn 60 12 Rewilding Language and Syntax 64 13 Land as Archive: The Sanctification of Space 69 14 Daily cartographer: On Anthropocentrism 75 15 Generosity is Free 80 16 Architecture and power 85 17 The Embodied Artifact 90 18 Phenomenology of Architecture 95 19 Semiotourisme 101 20 Ryegrass Lawn 106 21 Roots and Simulacra 110 22 Saving Tongues 22 23 The perception of a ‘Pollutant’: On Ecocriticism and Environmental Racism 122 24 Ecofeminism 2: On Agriculture 128 25 Holobiant Living 133 26 Gift Giving 137 27 Birdsong 142 28 The Entangled Being 147 29 Soul 152 30 Vanishing Point 157

1 Catkin Carpet

Abandoning progress rhythms to watch polyphonic assemblages is not a matter of virtuous desire. Progress felt great; there was always something better ahead. Progress gave us the ‘progressive’ political causes with which I grew up. I hardly know how to think about justice without progress. The problem is that progress stopped making sense. More and more of us looked up one day and realized that the emperor had no clothes. It is in this dilemma that new tools for noticing seem so important. Indeed, life on earth seems at stake.

— Anna Tsing (2014, p. 24)

Each year in early March the wintery frost begins to disappear; the days instead slowly warming, bringing with them the promise of spring. Daffodils bloom and the flamingo willow turns a buttery pink, as tufts of green peak amongst the paving slabs. A great emergence happens in our garden in March; the symphony of colours marking the end of a long voyage of dismal days, offering a relief with a magnitude comparable to Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic adventures.

The indulgence of petals, blossoms and the chatter of sunlight continues for a few weeks, washings finally hung outside, and coffees drank on the doorstep.

But every year, without fail, the joy of spring in the garden is bought to a grinding halt. Sitting snuggly along the fence line, our neighbours Aspen looms tall with its dangling branches and silvery trunk. In the third week of March, give or take a few days, it begins to develop these greyish fury entities, that hang precariously from

9

above. They are long and thin, with a feather like texture; wriggling in the wind, my brothers and I used to call them the ‘slugs of the sky.’ These curious things are catkins; ‘a branch with leaves and flowers, that have been condensed down into a small flexible dangling branch, a perfectly adapted way of getting pollen into the wind. Without the need to attract insects or other animals, they are devoid of bright petals, nectar and scent, insignificant and plain (Thomas, 2014, p. 168).

As the catkins form, numbers build on the branches and the tree becomes enveloped in a fury skin. My mother used to stand at the back of the house, scowling at the tree, remarking on their hideous character, threatening to chop the Aspen down, for the sight is so ghastly each year. With a few gusts of wind, the catkins made their way onto the ground, falling gracefully as they twirled with their grey wings. Landing on the lawn, a catkin carpet forms.

In my mother’s eyes, the catkins sit low in the garden hierarchy… even perhaps on the same level as the pests of nature; the pigeons, squirrels, ravens, and foxes. Unlike a rose or a tulip, the catkin can’t offer beauty or a sweet scent; they have no sensory pleasure and litter the garden grey. Yet, the catkins are really no different to any other flower, they follow the same structure, just condensed into a small flexible dangling branch. The Aspen catkin is ‘made up of s series of scales or bracts below which nestle tree flowers, each with two deeply divided stamens. The remains of the perianth are there but very small and insignificant’ (Thomas, 2014, p. 168). As wind pollinators, Aspen’s are much more efficient than insect pollinating plants, the pollen able to travel wider without the restriction of relying on another species for transit. The pollen is smaller than insect pollinated plants, helping it to travel through the air – ‘the pollen grains start with a negative charge on the anther but acquire a strong positive charge as they fly though the air, and the female flowers have a negative charge, which helps pluck pollen electrostatically from the streamlining air.’ (Thomas, 2014, p. 178).

The complexities of the catkin and their essential role in the

10 Composting is so hot

growth of new trees, which ultimately produces the oxygen we need to breathe, are undermined, and diminished to the level of a nuisance, as we see them so singularly as an unattractive weed-like plant. In a world constructed under capitalism, to the human, the catkin has no value (Tsing, 2015, p. 23). They do not offer an opportunity for progress, they cannot make the economy grow or make us more productive, they won’t advance technology or enable faster communication – the catkin cannot be sold or traded, for they are not beautiful enough to sit in a garden centre nor permanent enough to be handed out like seeds.

In her book ‘The Mushroom at the End of the World’ Anna Tsing (2015) attempts to position the reader to imagine a world outside the structures of capitalism, in which the ‘driving beat of progress’ is taken away. If we were to really look, listen, smell, and touch the catkin, we might notice its intricacies and intrinsic importance to the world it sits within; beyond the need of it having ‘economic value.’ Tsing (2015, p. 21) says:

Progress is a forward march, drawing other kinds of time into its rhythms. Without that driving beat, we might notice other temporal patterns. Each living thing remakes the world through seasonal pulses of growth, lifetime reproductive patterns and geographies of expansion. Within a given species too, there are multiple time-making projects as organism enlist each other and coordinate time-making landscapes.

As the Aspen catkins fall to the ground each spring, it is a silent reminder of the yearly cycle of regrowth, pollination, and seasonal shifts, marking a cyclical rhythm outside of the standard acceleration forwards; the work of the tree and all the actors involved are unveiled; the sun, the rain, the soil, the fertilising plants, the insects and animals. Anna Tsing (2015, p. 75) tells us that rather than seeing these non-human things as isolated elements, we must instead understand them as assemblages; since everything, human and non-human, is

11

wholly interconnected forming the complex and fragile ‘web of life.’ These assemblages could be conceived as polyphonic assemblages, comparable to the dense and complex music of the baroque.

Polyphony is music in which autonomous melodies intertwine…. when I first learned polyphony, it was a revelation in listening; I was forced to pick out separate, simultaneous melodies and to listen for the moments of harmony and dissonance they created together. This kind of noticing is just what is needed to appreciate the multiple temporal rhythms and trajectories of the assemblage.

(Tsing, 2015, p. 23)

The catkin is a part of a large polyphonic assemblage of all the things that let it grow, and all the things it pollinates as it drifts in the wind, away from our garden. Despite my mother labelling the catkins as ugly nuisances and capitalism telling us they have no monetary value; the role the catkin plays in the balance of the ecological system is as important as the flute in a baroque polyphony. The catkin is perhaps a lesson in engaging in the ‘art of noticing’ (Tsing, 2015, p. 18) as a way to counter and reconstruct the constant drive for progress that is thrust upon us; a way to re-situate ourselves as a part of nature, opposed to separate from it. The catkin tells us that nature does not need to be beautiful or productive because nature is simply not here to serve us; it is a part of us and we are a part of it.

12 Composting is so hot

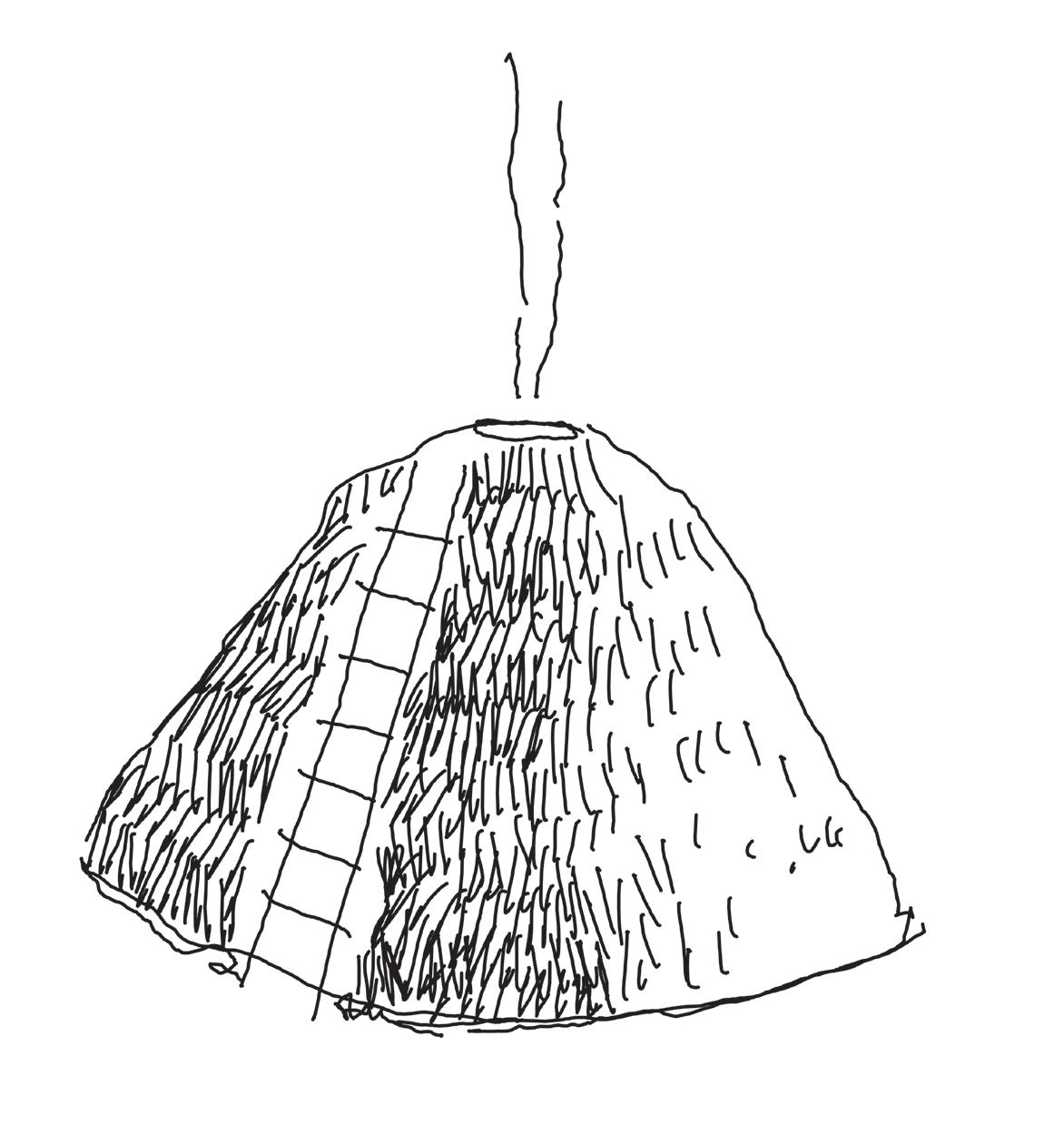

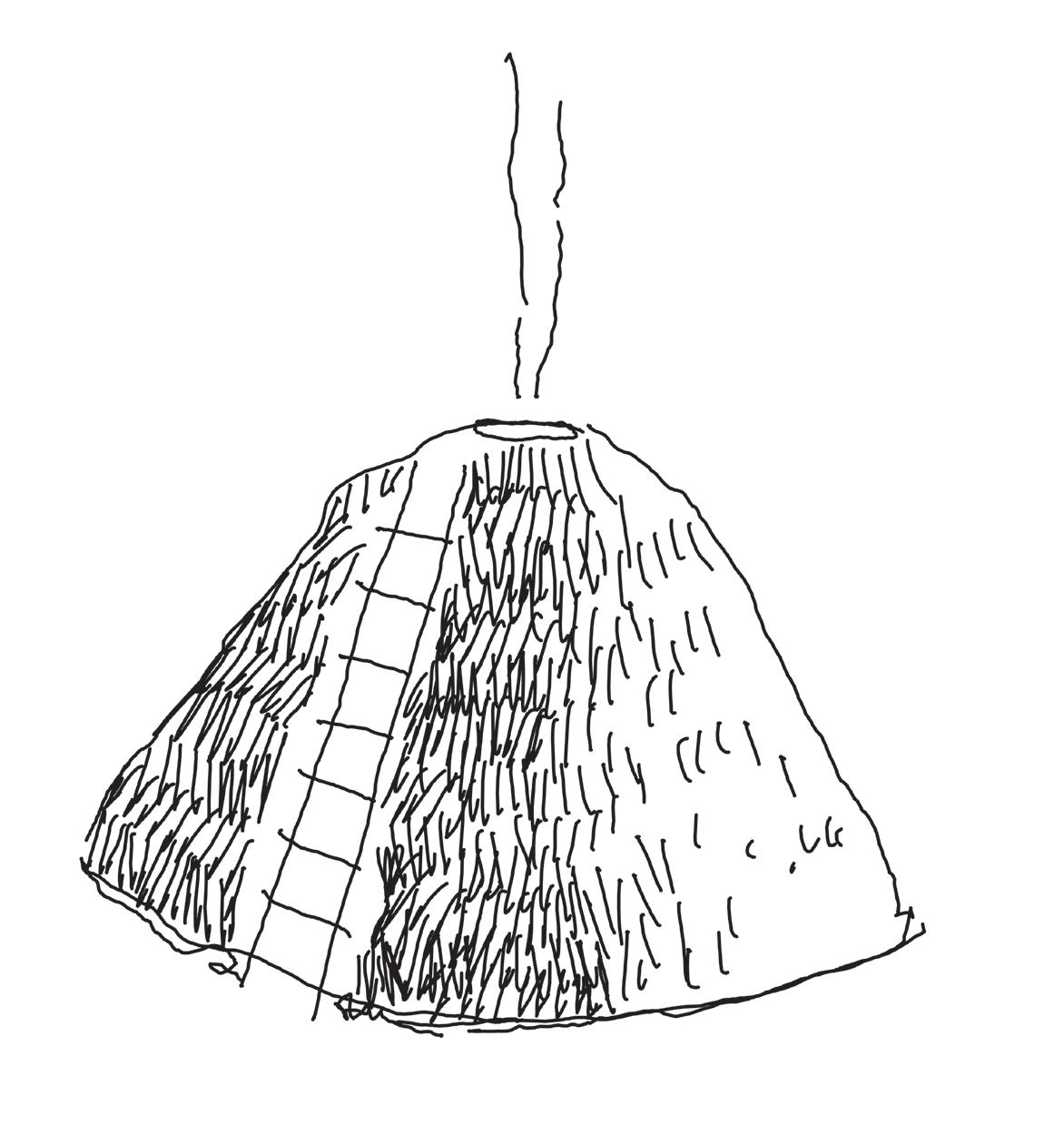

Buildings and Permanence

The mound builds up precisely because the material of which it is made is continually falling down.

— Tim Ingold (2013, p75)

past decisions in today’s world

Hill House, Helensburgh was designed and built by Charles and Margaret Mackintosh in 1902. It now stands superseded by another building, a waterproof box which allows the perishing external finish to dry out gradually.

A potter’s gardening shed on the Isles of Scilly comprises the layering of material and forms designed over decades of alteration. It stands now as a glass box resting on a stone plinth, repaired in places with damaged concrete.

Buildings loom over and persist beyond us. They have the perfect memory of materiality. When we deal with buildings we deal with decisions taken long ago for remote reasons. We argue with anonymous predecessors and lose. The best we can hope for is compromise with the fait accompli of the building. The whole idea of architecture is permanence (Brand, 1994, p. 2).

maquina do mundo

In Laura Vinci’s artwork, ‘Maquina do Mundo’ (‘The Machine of the World,’ Vinci, L., 2005) a conveyor belt moves ground white marble

13 2

between two heaps. Two representative monuments are created, on the one hand typical of the lavish material she chooses, but also similar to those we consider far more ephemeral. The movement of grains on the surface of each mound is seen at a close scale, but invisible a few steps back. Observing steadiness at a distance, closer inspection reveals the reality - constant alteration.

Buildings do nothing but change. Yet, we have developed a perception towards these monuments which embodies permanence and an attitude to building which demands a corresponding approach. In 1994, Stewart Brand documented our losing battle with the temporality of our own architectures and two years later, Pallasmaa (1996) refuted further the ‘ageless perfection’ (p. 34) that he saw manifest in modernism.

The relative insignificance of our built environment has also been observed by numerous authors (Koolhaas, 1995; Krier, 2009), who ask questions around the relation to its dwarfing environmental context. Do these monuments of which it comprises really change? These layered artefacts developing at a rate intangible to us have been rendered our most protective invention. Immediately ineffected by the weathering of our time, they surely endure a far greater permanence than the shifting mounds in Laura Vinci’s ‘Maquina do Mundo’ . We are aware of ongoing alteration in the design of our buildings, but a comparison to these ephemeral artefacts appears incompatible. Might examining their existence in the world of an alternative ‘us’ reveal a condition which could alter this perception?

the artificial and perception: learning from ants

In ‘Making’ (2013), Tim Ingold refers to a nest made by forest ants, using it to illustrate that ‘the earth is not the solid and pre-existing substrate that the edifice builder takes it to be.’ (p. 77)

Confining us firmly to our own biosemiotic realm, Ingold appropriates the ant’s nest as an extension of the earth, and it is

14 Composting is so hot

our temporal perception of stability and endurance that is the cause of this appropriation. To us, built up of only weakly bound soil compressed only by its own weight, the small mound could be kicked down in one movement. For an ant, months, even years, of work culminate to produce a nest that houses hundreds of thousands.

To an ant, irrespective of the duration of their ‘moment’ (Uexkull, 1957), their perception of the nest is fundamentally different. Whilst no investigation has determined the comparative motor processes of ants, the ability of ants to conduct their domestic activities within an area equal to the size of a laptop track pad, accurately adjusting their speed between the limits of 0.0001 mms-1 and 5mms-1 (Gallotti, R., Chialvo, D. R., 2018), is evidence enough that their visual receptor (and therefore other sense modalities (Uexkull, 1957, p. 29)) reach far beyond the resolution of ours.

Where we see an ants nest as an extension of the earth, ants percieve their artificial. But, to refute their status as natural, and establish them ‘artificial’ (as Ingold does not) is a rewarding provocation. Is our perception of the artificial limited to the products of our own species’ input? If we approach this problem from an etymological perspective, an investigation into our own term ‘artificial’ provides an interesting result.

The earliest recorded use of the word refers to our appropriation of half the diurnal cycle into a whole human ‘day,’ the ‘artificial day.’ Important in this case is our perceptual imposition of the ‘day’ onto a phenomena that already exists as ‘the diurnal cycle.’ To render this artifical, therefore, is not to change the substance of the thing, but to alter the perception it. If, however, we accept our biosemiotic fate and designate the products of all other living beings ‘artificial’ (the ants nest becomes ‘the pile of earth’ for example, appropriating their nest into an insignificant function of our being), the result is not what we might imagine.

If we can percieve/confuse so readily the products of other species’ as a function of our world, how might our labours appear in the worlds of others?

15

16 Composting is so hot

Fig. 1: Repair Works to Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Hill House, Helensburgh (BBC, 2019)

Fig. 1: Repair Works to Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Hill House, Helensburgh (BBC, 2019)

In the explanation of his biosemiotic theory, Jakob von Uexküll utilises numerous case studies of creatures which, due to the time intervals of their motor processes, experience a different ‘Umwelt’ to the one that we as humans do. ‘In the snail’s world [for example,] a rod that oscillates four times per second has become stationary’ (Uexkull, 1957, p. 31). To enter an Umwelt that renders our monuments closer to piles of shifting marble we only have to imagine the world of the snail, a creature for which the speed of its motor processes is more than four times slower than our own. What creature would it take, then, amongst the steady mass of our built environment, to perceive our most permanent architectures the way we might see a potters shed? Certainly one that is present in our world.

To experience other Umwelts is made difficult by the constraints of our own motor processes, and imagining the full connotations of their differences is impossible. Exploring the implications of an alternative perceptual realm, however, is a grounding exercise. Do our most monumental buildings really stand more firmly than the potter’s shed? How much does the changing mass of our urban environment really differ from the shifting surfaces of Laura Vinci’s ‘Maquina do Mundo?’

Deliberately striking the heart of our most sentimental architectures, the mounds of white marble ask questions around the condition of these ‘permanent’ monuments. Some buildings outlive us as human individuals, but it is these very facts, consolidated by our anthropocentric guise that render this perception our reality.

But what else do we have? Should we look to supposed other worlds to base our worldly activities? Which Umwelt should we imagine to assume best practice for the activities of our being? Our world contains many other Umwelts after all.

17 alternate umwelten

re-situating our built environment

We cannot hope to exist in total sympathy with the motor processes of other species. But, exploring alternative perceptions within a world that we artificially perceive, is rewarding in individual cases. In situations of crisis, we might hope that the anecdotal application of these scientifically proven (important) perceptual differences provides basis for a reconsideration of our present bounded worldly activities.

The mound builds up precisely because the material of which it is made is continually falling down. (Ingold, 2013, p. 75)

Whether building subsidence or falling sand, the effects of gravity are not infinitely resisted. What we build is purely for our thought, conceived with reference only to the scale of our time. Are there ways we can more sensitively facilitate the shifting surface of our built environment? To enable an (inevitable) changing condition, must we reposition our architectural perception closer (than our sensory apparatus leads us to believe) to that of Laura Vinci’s ‘Máquina do Mundo?’

Whilst our current systems are (naturally) geared towards the unique function of our own species’ motor processes, our very ability to establish this uniqueness demands a re-situation of the processes which currently destroy the environment we perceive.

18 Composting

is so hot

19

Fig. 2: Ongoing Repair works to a Potter’s Shed, The Isles of Scilly.

Image: Calum Montgomery

Collective Cognition

A pedagogy built on authentic dialogue, conscientisation and revolutionary praxis can never serve the interests of oppressors; on the contrary, it is openly supportive of the struggle against oppression. Problem-posing education reaffirms human beings as subjects, furnishes hope that the world can change and, by its very nature, is necessarily directed toward the goal of humanisation.

— Roberts (1996, p297)

Inside a square room, four rows of five seats sit in silence. The beige walls house displays of History, or English – never both – with the aim to inspire the cohort through carefully formatted, illustrated prose. To the right of the room, two large windows connect the inside to the outside, where learning ends and children play and run and talk, before returning indoors. Play ceases here.

At the front of the room, a teacher stands behind a desk and in front of a board, facing the rows of empty seats. The pupils file in, noisily. Each return to their assigned chair, sits down, but not before the teacher gives their first instruction – the lesson has begun in which they are to be taught.

Foolish to think they may learn from each other; a curriculum must be followed. Pupils must ‘learn’ to be graded, to be tested, to achieve. Knowledge to be bestowed upon vessels by the one who knows all. In a place made to educate, the classroom confines and silences and stifles, withholding the knowledge and experience existing outside of

20 Composting

3

is so hot

traditional teaching

Essentialism is a philosophical theory which emphasises the teaching of traditional skills taught by a teacher to a student. Essentialism has come to influence modern day education over other forms of philosophical theory due to increased standardisation and importance placed on outcomes rather than the experience of learning. Within modern day education, from primary schools up until university level, the distinct hierarchal structure prohibits creativity, free-thought and perpetuates oppression within an educational setting. This pattern seeks to propose that a more dialogical approach to education may create more rewarding learning opportunities and increasingly humane practices within a modern society.

Although in more recent centuries active learning techniques have become a more developed practice within education, the issue of heirarchy perpetuated by ‘banking‘ educational practices still prevails in modern day educational institutions. The term ‘banking’ was first coined by Paulo Freire in his 1968 book Pedagogy of the Oppressed; it refers to a system in education whereby teachers ‘deposit’ knowledge into students. Freire (2018, p. 72) states;

In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing.

This is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, banking assumes that students know nothing, and can only learn from the teacher who knows everything. This therefore limits the students’ capacity to engage in critical and creative discussion (Freire, 2018, p. 296), failing to acknowledge each other’s points of view and the socio-political context of said teaching. Secondly, this perpetuates the hierarchical

21 the four beige walls.

essentialism and banking within education

relationship between student and teacher, as the teacher acts as the oppressor and the students, the oppressed.

breaking the cycle of oppression

In order to create more humane educational systems, oppression must be abolished from educational practices. Oppression through educational ‘banking’ stifles creative thinking which students must recognise to consequently breakdown the oppressive structures they are in (Freire, 2018, p. 296). Often, those as a collective fail to recognise the power they have to liberate themselves, and instead strive to obtain the role of the oppressor. This, however, is a false depiction of liberation. As Freire (2018, p. 46) states;

It is a rare peasant who, once ‘promoted’ to overseer, does not become more of a tyrant towards his former comrades than the owner himself.

This illustrates how the cycle of oppression is never broken when the oppressed wish to become the oppressors as this is their perceived freedom, instead of having the ability to recognise their collective power in pursuit of true liberation.

An example of the cycle of oppression within modern-day educational systems is exhibited in the 2022 Environmental investigation which looked into the teaching practices at the Bartlett School of Architecture. The report details how power dynamics were a key issue which led to multiple accounts of misconduct, bullying and contributed towards the toxic working environment of the school (Howlett Brown, 2022, p. 39). Students stated they were gaslit and bullied by tutors and furthermore, it was extremely difficult for students to present their issues to anyone that would listen as comments such as ‘it’s always been this way’ (Howlett Brown, 2022, p. 39) were used to normalise the poor behaviours of the tutors in

22 Composting is so hot

power. This was compounded by the employment of former alumni as tutors who would perpetuate this teaching style. In this sense, the tutors as the oppressors use the imbalance of power to take advantage of those below them, allowing them to have leverage over their access to opportunities, resources and bargaining powers over the student (Howlett Brown, 2022, p. 41), and worse, the power to speak out against them due to years of cyclical oppression before.

problem posing education and de-schooling society

In order to combat this dehumanising approach to education, one must consider other means of education where a hierarchy between the student and teacher is dismantled, and learning is prioritised. The dialogical approach of ‘problem-posing’ education serves as way to achieve this. Teachers assume the role of both teacher and student and vice versa for the students (Freire, 2018, p. 296); this allows everyone in the education process to have the ability to teach and be taught, thus disassembling the hierarchy on both sides. The role of the teacher fundamentally changes so that he/she may offer structure, direction and a goal for the educative process as well as offering critical feedback for both verbal and written work, however in doing so does not impede on the ‘horizontal’ structure opposing traditional hierarchy within education (Freire, 2018, p. 172). This approach to teaching benefits students, allowing them to situate their own thoughts amongst those of other students and within a socio-political context. Furthermore, it encourages interrogation, critical thinking and connection between different topics and subjects to facilitate an integrated learning experience beyond the parameters of a traditional curriculum, consequently leading to a more humane approach to education.

To further enhance the learning experience, one must also learn to prioritise the experience of learning over learning outcomes and results. Too often, emphasis is placed on getting the best grade, a

23

good examination result or on one’s productivity, achieved through an already pre-determined curriculum. The process of learning is something which is a means to achieving these goals, not an action which is prioritised in its own right (Illich, 1974, p. 3). In his book ‘Deschooling Society,’ Illich argues that often traditional teaching does not, in fact, enable us to learn effectively. Frequently, things like learning a new language, can be learnt more effectively when fully immersed in a native-speaking country rather than through dictatorial approaches as used in schools (Illich, 1974, p. 7). Problemposing education begins to dismantle this ‘banking’ approach to education, however this can be taken one step further by allowing education to manifest itself outside of the traditional school walls in a de-centralised version of ‘school.’ This is further explored in the pattern ‘Network of Learning,’ which illustrates how education may be re-invented to allow it to take place within the city or town, outside of the traditional school walls (Alexander et al., 1977, p. 100). The pattern further explains how this would allow anyone to become a teacher of their skill and allow anyone to be a student, allowing them to pursue their own educational interests and embrace the expertise of those around them.

In order to create a more humane educational practice, one must first recognise the oppression acting within current educational systems in order to change it. Once oppression has been perceived, steps can be taken to ensure the pursuit of liberation is sought through dismantling hierarchical practices and working towards equality within educational practices. Furthermore, one must interrogate teaching methods and ensure that the process of learning is prioritised over perceived measurements of achievement such as tests and examinations. Finally, de-centralising school systems should be considered in order to allow wider access to education, broaden the curriculum and allow people to easily pursue personal interests through a network of people who support them.

24 Composting is so hot

On Ecofeminism 1: A Manicured Garden

… there can be no question of the forest as a consecrated place of oracular disclosures; as a place of strange or monstrous or enchanting epiph- anies; as the imaginary site of lyric nostalgias and erotic errancy; as a natural sanctuary where wild animals may dwell in security far from the havoc of humanity going about the business of looking after its ‘interests.’ There can be only the claims of human mastery and possession of nature – the reduction of forests to utility.

— Robert Pogue Harrison (1992, p121)

Nature has been subjugated to the market as a mere supplier of commodities. Women have been subjugated to patriarchy as mere suppliers of labour. And both nature and women are now seen as mere instruments of economic growth.

— Val Plumwood (1993, p169)

In a sense of both majesty and melancholy, the striking figure of a tree floats along the water’s serene current. The visual spectacle is the opening scene to Salom ... Jashi’s, Taming the Garden (2021), an otherworldly tale of the venture of Georgia’s former prime minister and bil- lionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili. His presence is felt only through murmurs and folkloric tales, along his surreal quest to collect centuries-old trees across the country of Georgia, transporting them at colossal expense and upheaval into his private garden - a curated garden of flamboy- ance and excess. (Taming the Garden, 2021)

Jashi’s film is a very literal portrait of one man’s pervading power over the natural world, highlighting the absurdities of this

25 4

is so hot

26 Composting

Backpacking Cooking gear

Clive Catton

quest to conquer and own. The natural world has for centuries been subjugated to oppressive systems that prioritise economic growth and human domi- nance. This view of the world, or even the universe, as a mere utility for us to master, perhaps began most critically during the Scientific Revolution. It marked a significant turning point in human history which ‘posited the universe as an assemblage of parts functioning according to regular laws that men could, in principle, know in their entirety’ (Garrard, 2012, p. 69). Led by Francis Bacon, Rene Descartes, and Isaac Newton among others, this view replaced the previous view of the Earth that our ancestors followed. What before was a nurturing ‘Mother Earth’ or ‘Magna Mater’ was now something that could be read, measured, extracted and used. This led to the belief that the uni- verse was a great machine that could be controlled and manipulated by humans, according to regular laws that humans could know in their entirety. This worldview, which places humans at the centre of the universe, is known as anthropocentrism. It refers to the point of view that ‘humans are the only, or primary, holders of moral standing. Anthropocentric value systems thus see nature in terms of its value to humans’ (Oxford Bibliographies, 2021).

Whilst this view of the world places the human at the centre, other schools of thought suggest there is also a gendered argument. Ecofem- inism is a philosophical and social movement that links feminism with ecology, arguing that the domination and exploitation of nature is intrinsically connected with the subjugation of women. Ecofeminist Val Plumwood argues that, ‘The inferiorisation of human qualities and aspects of life associated with necessity, nature and women—of nature-as-body, of nature-as passion or emotion, of nature as the pre-sym- bolic, of nature-as primitive, of natureas-animal and of nature as the feminine— continues to operate to the disadvantage of women, nature and the quality of human life. The connection between women and nature and their mutual inferiorisation is by no means a thing of the past, and continues to drive, for example, the denial of women’s activity and indeed of the

27

whole sphere of reproduction’ (Plumwood, 2003, p. 21). With Caroline Merchant also presenting a view of the Scientific Revolution that saw the feminine Magna Mater disenchanted and rational- ised by masculine reason. She also notes that Mother Earth’s last followers, Europe’s ‘witches,’ were brutally rooted out (Merchant, 1990, p. 172). This relationship between feminism and ecology is explored in the works of many prominent writers who state even the story of the Garden of Eden has ecofeminist readings, suggesting the story represents the historical and ongoing exclusion of women from nature, as well as the exploitation of nature for the benefit of men. Vera Norwood speaks about this stemming into the early male domination in nature study, stating that, ‘From the earliest work in natural history- the general investigation of plants, animals, and the physical environment - to its nineteenth and twentiethcentury growth and the division into specialised disciplines like botany, ornithology, and geology, men have defined the subjects and methods of study’ (Norwood, 1993, p. XIV). In more recent history, ecofeminists have suggested that environmental deg- radation as a symptom of anthropocentrism has disproportionately affected the lives of women, especially those in the Global South, where women are more often responsible for collecting water, fuelwood and other resources that are more scarce due to climate change (Shiva, 2002, p. 75). The chauvinistic attitudes present here, can be considered in relation to the anecdote opening the pattern, the film Taming the Garden (2021). It can be read not only as a critique of anthropocentrism but also as an ecofeminist critique of the patriarchal dominating system that prioritises power, status and greed over the well-being of the environment and the citizens who inhabit it.

Whilst ecofeminism as an ideology suggests that women have continually been disregarded from conversations regarding nature, Mary Austin provides an enjoyably different standpoint. She confronts the myth that ‘nature is no place for a woman’ by noting the traditional roles that are necessary to survive in the wilderness,

28 Composting is so hot

observing that the ‘self-reliance’ of the unafraid male figure battling the wilderness relies heavily on the ‘feminine’ domestic tasks such as mending clothes, cooking and foraging. An interesting restructure of the masculine harnessing of nature. (Garrard, 2012, pp. 84-85)

The human quest to conquer and dominate the natural world has been perpetuated for centuries, with the Scientific Revolution playing a significant role in the establishment of the view of the world as a mere utility to be mastered. A view that has given hegemony to humans and led to a disconnect between the human and the nonhuman systems that we are part of, causing extreme environmental destruction and social injustice. This viewpoint is also intrinsically linked to the patriarchal systems that have given rise to it, succeeding to exclude women from discussions around the natural world as well as to segregate them entirely. Vadana Shiva suggests that, ‘The industrial revolu- tion converted economics from the prudent management of resources for sustenance and basic needs satisfaction into a process of com- modity production for profit maximalisation... This new relationship of man’s domination and mastery over nature was thus also associated with new patterns of domination and mastery over women and their exclusion from participation as partners in both science and develop- ment’ (Shiva, 2002, p. xvii).

Therefore, the domination of nature and women is linked, and cannot be addressed separately.

Therefore, the domination of nature and women is linked, and cannot be addressed separately.

We must recognise that the domination of nature and women stem from the same social and political structures that value some beings over others. By recognising the intrinsic value of all human and non human beings, we can challenge the systems of oppression that are systemic in our societies, and can move from a culture of domination to one of respect, compassion and interconnectedness with the natu- ral world.

29

EcoPhenomic Pulsations

The earth is an ode and we are but one breath. Each word grown carefully, the letters fitting a precise pattern It is a complicated text of course. A language uncommon to most and interpreted variably. The rhythm must be kept,but as we have melded into this poem, the rhythm has fallen away. We come as full stops. We break and twist the words, breeding sentences we desire. What meaning it had has been blurred through the pages. I’m afraid these lines cannot go on, but hope that we can breathe again.

— Indigo Leveson-Gower

(2023)

‘Sound is language’s flesh, its opacity as meaning marks its material embeddedness in the world of things . . .In sounding language we ground ourselves as sentient, material beings, obtruding into the world with the same obdurate thingness as rocks or soil or flesh. We sing the body of language, relishing the vowels and consonants in every possible sequence. We stutter tunes with no melodies, only words’

—

Charles Bernstein

(1998)

It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties.

—

Donna Haraway

(2016)

30 Composting is so hot 5

Nature by any other name might smell sweeter. I am sitting in my room; I have positioned my chair before my window with my feet propped up on the sill. My laptop sits between my eyes and the exterior environment, ready to catch my thoughts. I feel safe in this space, the temperature is optimal, and my chair is cushioned. From here I can see a snippet of the world you and I inhabit. To categorise: I see several trees, two five-storey blocks of flats, a crosssection of a road and a lawn fenced into a garden. A thought crosses my mind; the only thing not placed by man in this space is the sky, the thought stops mid tracks as a plane comes into view, breaking up the clouds. This is a city. The vast majority of humans live within one of these. We surround ourselves with reminders of ourselves. The city is constructed from elements of nature, into something separate to, but within the natural world. The trees and lawn serve as a small reminder of the natural world; however, they are placed within boundaries, a concrete pathway, a metal fence. Boundaries not to be broken lest they become an inconvenience. Within such a world how can the dichotomy between ‘nature’ and ‘humans’ not be reinforced?

Language as a Tool

How we define and compartmentalise the world is not only a tool to perceive, but a tool that defines how we perceive. We ‘weave the world to word’; the language we create defines the non-human world and how we act within it. (Knickerbocker, S., 2012.) In ‘The Trouble with Wilderness’ William Cronan argues that the idea of wilderness as a pristine and untouched place is a myth that has had a profound impact on American culture (Cronan, 1996). European settlers’ view of North America as a ‘wilderness,’ vast and untamed, led to their desire to conquer and transform. The term in contemporary society is now imbued with a sense of otherness – something to view from afar. Cronan argues for a more nuanced view of the ‘wilderness’

31 natures name

leading to a less binarized interpretation of the environment. This in turn could create a sensitive and holistic approach to ecological thought.

If the goal of environmentalism is to facilitate a significant connection with the natural world and promote behaviours that are more attuned to ecological concerns, then what role does language play? Just as we shape language, can language shape us? John Austin examines this in ‘How To Do Things With Words,’ coining ‘locutionary force’: the core meaning of a word and the ‘illocutionary force’ which is what is achieved by saying a word (Austin, 1962). The ‘illocutionary force’ of ‘wilderness’ led to destruction. Could we transfer this to how we speak on matters of the environment: the perceived meaning of these terms, and what is actually achieved?

New Pulsations

At this moment in time, the age we are living in is often referred to as the Anthropocene. This term ‘Anthropocene’ is mired with meaning that transcends its definition. It is a shifting point in the Earth’s history, where human activity has become the dominant force that shapes the planet and has had an irreversible impact on the Earth’s systems. Coined by Paul J Crutzen, it stems from the Greek ‘anthropo’ (Human) and ‘cene’ (new) (Crutzen, 2006). Donna Haraway argues that by using this term we limit our perception of the world and the way in which we can live in it. It reinforces the importance of humans and of our actions, failing to acknowledge the agency and relevance of non-humans. The ‘illocutionary force’ stops us from acknowledging this and taking action. Haraway instead suggests the term ‘Chthulucene’; this term calls for the hierarchy between species to be abolished and focuses on the interwoven and interconnected nature of the world, including humans, non-human entities, and geological forces; a new ‘illocutionary force’ (Haraway, 2016). ‘Chthulu’ derived from ‘Cthonic’ meaning ‘of earth’ in Ancient Greek;

32 Composting is so hot

this calls for a shift in perception to valuing the earth in its entirety and decentring the human experience. She goes on further speaking of ‘Humusities,’ the integration of the study of humans with the study of the earth and its ecological systems. The term is aplay on the word ‘humanities’ and the word ‘humus’ which refers to the organic matter in soil that is essential to plant growth. These terms are grounded in an ecological perspective, unable to be untied.

Words over time have lost meaning. A tree means just that, a tree. With a new approach to language, could we ground them in further meaning? If I look out my window I see ‘a tree,’ if I think and feel harder, perhaps I see ‘a life giver’ cut off from its fellow ‘life givers.’ When I look and see a ‘a lawn,’ perhaps I see a ‘confined monoculture.’ When I look and see an apartment, perhaps I see an ‘isolated world.’ When I look and see a road, perhaps I see a ‘colonising path.’ This view now, is not just a city, it is a battle ground.

33

Designing through Commonism

In commonism, all of social life manifests itself, in all its complexity. Perhaps this is why it has the potential of a meta-ideology. Just like the message of liberty of neoliberalism appeals to both left and right across party lines, so commonism’s call for the working class but also to an endangered middle-class, the proletariat and the precariat, people with and without jobs, students and pensioners, women and men, heterosexuals and holes, legal and illegal aliens. Also, both progressive and conservative forces now regard social deprivation as problematic.

— Nick Dockx and Paul Gielen (2018. p85)

Walking down Fenchurch Street in the city of London, can’t help but reminiscing about the city’s Roman past due to the many listed buildings on the surroundings that carry a lot of history. This particular building stands out, it is unavoidable. It is colossal. Its height and shape seem somehow misplaced. It is impressive, incandescent with the sun. Over 30 stories covered in shiny glass. You enter the building and the large lobby is unwelcoming, the space is cold, the double height spaces filled with bright lights and white walls. The curve at the top of the building increases the reflection of sunlight and it has been known to melt cars.

In our society, appearance often holds more value than substance. This mentality is deeply embedded in the construction industry. Too often, design decisions are driven by financial gain or aesthetic appeal, rather than to the community needs. Projects are designed for the ‘books,’ with a focus on profit over purpose. As a result, buildings may not function efficiently or effectively for the people who use

34 Composting

6

is so hot

them. Design should prioritise the needs for the people, not just the financial goals of individuals or practices.

The concept of commonism is introduced by Nick Dockx and Paul Gielen in their book, Commonism: A New Aesthetic of the Real, where they describe this term as an ideology that could be compared to neoliberalism, fascism, or even religion, in the sense that all these ‘belief’ systems claim to be the only truth of the real. They defend that commonism it is in much more close proximity to how social relationships work and to what humanity is about, considering it places the human figure - in her/his/they - total context at the centre of everything. This ideology promotes values of sharing and the community. In addition to this, they see it as a way to challenge the powerful capitalism system and create a more impartial society.

(Dockx ans Gielen, 2018)

A prime example of commonism is the project of Lina Bo Bardi in Sao Paulo, Brazil. The SESC Pompeia cultural centre might be seen by some as ugly, colossal, bizarre, but certainly remarkable. Built in the 90’s at the very end of the military dictatorship when the society was still sceptical about modernist buildings, this brutalist building, which was inspired by British factories, was shocking for most of the population. The sesc complex is characterised by reusing as many materials it was possible, and composes of raw brickwork, steel beams and reinforced concrete. The former drum factory was stripped off back to its original reinforced concrete and the materials were intentionally left exposed. Bo Bardi added two huge concrete towers connected by footbridges and a third seventy meter tall tower that could be seen from a great distance.

What used to be an old metal factory soon had become a vibrant space that provided the local community with education, leisure and culture. At the heart of the design was the people from Pompeia and what they wanted and needed as well as using existing resources to create something meaningful for the community regardless of their economical or social position. Citing Zeuler R.M. de A. Lima on his biography of Lina Bo Bardi ‘architecture is not a matter of stylish, it’s

35

a matter of solving problems that emerge from a specific situation, which can only be solved by producing something that is in harmony with the cultural, social, and economic situation of a given time and place’ (2013, p17).

But is the aesthetic and beauty of a building more important than its uses and spaces? The director of SESC, Danilo Santos de Miranda said ‘the exhibition is an educational journey through the artist’s work, which exercises the sensitivity of visitors who pass through the free and welcoming environment of Sesc Pompeia (…) the institution fulfils its mission by spreading the Visual Arts to a wider audience, confirming that culture is intrinsic to human development and a driving force of transformations aimed at expanding the quality of life of society as a whole’ (de Santos Miranda, 2019) - his statement illustrated the importance of a cultural centre as it is the case of sesc pompeia, a place that promotes arts and culture to anyone that needs or wants regardless if they could or not afford it.

Dockx and Gielen delve into the concept of commonism as a new way of thinking. Their book explores three main areas: the commons, commonalities and common sense. The first reflects resources that are to be used by the community such as land, water, air… and that are not property of a single person or group but that belong to everyone. Commonalities reflect on the values of sharing (beliefs, culture, knowledge) with others from different backgrounds in order to bring people together and create and enhance the bond within the community. The last emphasises collective intelligence - each person has their own talents and skills that increases the dynamic once shared - and it is the very beginning for social change.

Citing Dockx and Gielen ‘culture as the bases and not as superstructure because culture stands for the whole process of giving meaning to ourselves and to the societal environment we are living’ (2018) meaning culture and the way it is shared it is crucial and shapes our own selves and the world we live in.

The concept of commonism, focusing on the three areas previously mentioned, can be found at the SESC Pompeia that

is so hot

36 Composting

Marcelo Ferraz

37

Pescaria no Rio (Fishing in the river)

focus on community, collaboration and participation rather than on individualism and financial gain. This is a powerful example of how following these principles lead to a successful scheme that not only is more inclusive but also criticises the current pattern of profit-driven design.

Would addressing this problem help tackle other wide problems such as social inequality? Bo Bardi’s creation used both existing resources and affordable materials to transform this old factory into a spirited and dynamic space that is still being used by the community of Sao Paulo in the present day. It counts with performances and community events that not only brings the community together but also people from other backgrounds that come to share values and experience cultural exchange which brings people together and contributes to a more inclusive and equitable society.

Architecture ought to be a tool for social transformation, designed to encourage community engagement and to benefit the society as a whole. In order to shift from financially gain design to community centred design, designers should welcome the principles of commons, commonalities and common sense.

The ideology behind a community-centred approach means that people and the community work together, sharing values and knowledge, that can increase the potential of the design to project spaces and create contexts that will suit the human needs in a more social and sustainable way, whilst reflecting the values of sharing and community. Designing for the ‘books’ has no such impact on society as a whole as the projects that have embodied these principles, such as SESC Pompeia Cultural Centre, which has become a metaphor of social transformation through design.

38 Composting

is so hot

the poetics of water

In the Western world, the four fundamental elements are earth, air, fire and water. Gaston Bachelard has devoted several works to their symbolism. One of them, which concerns water (water and the dreams), suggests that it is a cultural asset.

By letting himself be guided by the images of the poets and by listening to water and its mysteries, he leads the reader into a meditation on the imaginary of water. He distinguishes between two main types of water that evoke myths and fantasies: clear, shining water, which gives rise to vivid and fleeting images, and still, heavy water, residing in the dark depths, which is linked to the image of death. He also discusses what he calls ‘compound waters’: water that burns, water penetrated by night and water-soaked earth. Finally, according to the philosopher, when water becomes a nourishing liquid, its character is maternal, feminine. But he also believes that there is a morality of water, since it is used as a means of purification, a supremacy of fresh water, a ‘violent water’ and a whispering water that speaks …

Thierry Paquot extended Bachelard’s reflections on the symbolism of water by examining more specifically its place in the life of societies. While taking up the themes of stagnant water, living water, fresh water, sea water, rain water and stream water, he relies on more rational data, whether chemical, economic, geographical or ecological. For this author, there is a geopolitics of water that guarantees an imaginary that ensures that every human being has a share in humanity.

39 7 Water

The teaching of Babylon

For ancient civilizations, water was a revered good. Drought, or on the contrary floods, were considered as punishments sent by a God who was displeased with mankind. In the Mesopotamian empire of Babylon (which reached its peak in the 6th century BC), it played a central role in culture and daily life. The Babylonians regarded water as a symbol of life. Their priests claimed that the gods controlled the waters of the earth and that they were a source of fertility and abundance. They built temples and shrines specifically dedicated to the water deities and devoted many religious ceremonies to them. There was Enki, the god of water and wisdom, and Tiamat, the goddess of primordial waters. According to their mythology, the universe was originally a chaos of tumultuous waters. The gods had to separate them to create the order of the world.

Living between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Babylonians developed a civilization based on the domestication of water. Irrigation systems watered their crops and fed reserves from which they drew water during periods of drought. They built dams and canals to control the flow of water, while they used water wheels to power mills and other machinery privatization of water in nature

‘Water is the engine of nature’ said Leonardo da Vinci. Yet at the beginning of the 21st century there is a global crisis in access to water. This is evidenced by photographs of arid, cracked, dry fields, strewn with decomposing cattle carcasses... Meanwhile, multinationals are getting rich by exploiting and distributing water. Overconsumption comes mainly from productivism in agriculture, which waters corn fields with water cannons, while the slurry from thousands of pigs pollutes the ground waters. Each good produced requires an extraordinary amount of water: a kilo of hamburger requires

is

40 Composting

so hot

an average of 16,000 liters of water, a kilo of chicken 5,700, a kilo of cheese 5,000 and it takes 400 to 2,000 liters of water depending on the region to produce a kilo of wheat. Textile, electronics and metalworking companies also overuse water. In everyday life, an American spends an average of 500 liters of water (including washing cars, filling swimming pools and watering lawns), it takes about 300 liters for a European. While 20 liters per person per day is considered a minimum, some people have only one or two liters. The inequality in access to drinking water is extreme. Every year, international organizations publish worrying estimates of the number of people without water (more than 800 million in 2015). A majority of them live in Africa where they are victims of water-linked diseases such as cholera, diarrhea and legionellosis.

In recent years, the major droughts that have occurred during the summer months in Europe have alerted the public authorities. In France, the state has provided 70% of the funding for a ‘megabasin’ project in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region (in Sainte-Soline). This is a retention basin that draws water in winter from the ground and stores it in basins that can hold up to 650,000 cubic meters of water, the equivalent of 260 Olympic-sized swimming pools, so that it can be redistributed in summer during droughts in the lands of multinational food companies.

This misuse of water that affects smallholders is an ultimate drift of capitalism which seeks to privatize water. In France, resistance movements have organized themselves and given rise to huge demonstrations. They suffered violent repression by the armed forces sent by the state. With many injuries and one death, these movements were banned for disturbing public order …

Globally, the problem of water supply will only get worse. If the quantity of water available on the whole of the terrestrial globe hardly varies from one year to the next, safe and drinkable water will be more and more unequally distributed while the demand will be growing. As a result of global warming, some territories must now carry out desalination, which is costly in terms of energy (solar, wind, etc.), while

41

others are forced to ration their water reserves. It is to be expected that water resources will be the cause of geopolitical tensions.

For ancient civilizations, water was a revered good. Drought, or on the contrary floods, were considered as punishments sent by a God who was displeased with mankind. In the Mesopotamian empire of Babylon (which reached its peak in the 6th century BC), it played a central role in culture and daily life. The Babylonians regarded water as a symbol of life. Their priests claimed that the gods controlled the waters of the earth and that they were a source of fertility and abundance. They built temples and shrines specifically dedicated to the water deities and devoted many religious ceremonies to them. There was Enki, the god of water and wisdom, and Tiamat, the goddess of primordial waters. According to their mythology, the universe was originally a chaos of tumultuous waters. The gods had to separate them to create the order of the world.

Living between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Babylonians developed a civilization based on the domestication of water. Irrigation systems watered their crops and fed reserves from which they drew water during periods of drought. They built dams and canals to control the flow of water, while they used water wheels to power mills and other machinery the water flowing under the cities

Water scarcity is also the source of a new concern: the way its natural sources have been treated in cities. In the 20th century, most of the rivers were totally covered by huge concrete structures in order to eliminate new sources of urban pollution conveyed in running water, to contain floods and above all to be able to flatten new surfaces available to clear roads and construct new buildings. Once the water sources were buried, they were radically invisible. Modern ideology then seemed to impose that the well-being of man depended on an environment made up solely of artificial soils. This is how most cities

42 Composting is so hot

buried their waterways. Residents have become utterly unaware of the location of their underground aquifers and the rivers and streams that once flowed above ground.

At a time when the urban population lives in atmospheres saturated with pollution and worries about the ecological disasters to come, it is a concern to find a link with the tangible signs of water from natural resources. It has therefore become important to rediscover the invisible rivers that flow under our cities, to value them and to protect them. Thus a few initiatives are emerging to explore the means by which it is possible to reintegrate these water sources into the fabric of urban life. The objective is to create resilient and sustainable systems that benefit both the environment and the development of a new urban imaginary reconciled with nature.

The solutions to be implemented are of several orders. Cities can reclaim covered rivers and streams to restore them as natural waterways. Cities can create new green spaces and improve plant and animal biodiversity in their surroundings. They can also integrate water into the built environment in several ways: through planted roofs including rain gardens; diverting rainwater to fountains and water features.

On a larger scale, cities can create beautiful and functional spaces that will help manage stormwater runoff while reducing urban heat island effects.

In addition to rainwater harvesting, cities can also consider harnessing alternative water sources such as ‘grey water’ (polluted) and salt water. By diversifying their water sources, they can reduce their dependency while ensuring a more reliable and resilient water supply.

With regard to the quality of the emotional life of the inhabitants, these projects aim to re-enchant cities by rediscovering the sounds of water in neighborhoods that have become silent again, forgotten daytime or nighttime aquatic reflections and a whole poetic imagination linked to the life of a fauna and flora that we thought had disappeared forever.

43

Perception In Time d Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

We are easily deluded into assuming that the relationship between a foreign subject and the objects in his world exists on the same spatial and temporal plane as our own relations with the objects in our human world. This fallacy is fed by a belief in the existence of a single world, into which all living creatures are pigeonholed. This gives rise to the widespread conviction that there is only one space and one time for all living things.’

— Jakob von Uexküll (1957, p14)

‘Imagine you’re walking through a flower strewn meadow humming with insects and fluttering with butterflies. Here we may glimpse the worlds of the lowly dwellers of the meadow. To do so, we must first blow a soap bubble around each creature to represent its own world filled with the perceptions which it alone knows.’ ... He states, ‘through the bubble we see the world of the burrowing worm, of the butterfly, or of the field mouse, the world as it appears to the animals themselves, not as it appears to us. This we may call the phenomenal world or the self-world of the animal.’

(Uexküll, 1957, p5)

‘… this eyeless animal finds its way to her watchpoint [at the top of a tall blade of grass] with the help of only its skin’s general sensitivity to light. The approach of her prey becomes apparent to this blind and deaf bandit only through her sense of smell. The odour of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, works on the tick as a signal that causes

44 Composting is so hot 8

her to abandon her post (on top of the blade of grass/bush) and fall blindly downward toward her prey. If she is fortunate enough to fall on something warm (which she perceives by means of an organ sensible to a precise temperature) then she has attained her prey, the warm-blooded animal, and thereafter needs only the help of her sense of touch to find the least hairy spot possible and embed herself up to her head in the cutaneous tissue of her prey. She can now slowly suck up a stream of warm blood.’ (Agamben, 2012, p46).

Let us imagine the life of a tick.

Patiently waiting on a blade of grass, ‘a tick can wait eighteen years’ (Uexküll, 1957, p17) before acting on its innate instincts to jump onto its prey, pump itself full of blood, fall to the floor, lay its eggs and die. In contrast, human beings operate on a completely different temporal timeframe, with a completely different array of senses. For humans, a single moment ‘lasts an eighteenth of a second.’ (Uexküll, 1957, p12). It is this difference in time and space that we are looking to explore within this pattern - how can we separate ourselves from our singular experience and move away from the fallacy that is the single unidimensional world?

The above quote shows Uexküll taking us on a journey through a meadow. Here, Uexküll encourages us to consider the world experiences by other living beings. Uexküll goes on to explain that when we ourselves enter a bubble of another, an insect in a meadow, our own familiar perspective of the meadow is challenged and transformed. Uexküll further demonstrates the phenomenal world through the story of the tick.

Here we see that the reality of the world is wrapped by the subject, dismantling the widely held assumption that the world we perceive is the only world that exists. Each living being is confined to their bubble of experiences which is formed from their individual perceptual sensory cues. This notion can be extended to the seemingly concrete nature of time itself. The idea being that the

45

Tick

Schiller, C.H., Kuenen, D.J

1957

is so hot

46 Composting

‘widespread conviction that there is only one space and one time for all living things.’ (Uexküll, 1957, p5) is not the case.

Umwelt theory inspired many important thinkers of the 20th century and the branch of social theory: phenomenology . Merleau-Ponty and Heiddiger inspired important ontological and epistemological thinking which led to phenomenology becoming a methodology in itself, where qualitative, subjective data, is deliberately sought after and held as valid.

Phenomenologist James Gibson believed: ‘the world which the perceiver moves around in and explores is relatively fixed and permanent, somehow pre-prepared with all its affordances ready and waiting to be taken up by whatever creatures arrive to inhabit it.’ (Gibson, 1983). For Uexküll by contrast, ‘the world emerges with its properties alongside the emergence of the perceiver in person, against the background of involved activity. (Ingold, 2011, p208). The subject is fundamental in the construction of the world, shown clearly when looking at the life of a tick. This phenological framing completely shifts the singular, athropectric view of the world which permeates western thought.

Moreover, Uexküll appears to posit humans and a tick on the same level metaphysically, meaning he does not seem to hold humans’ consciousness as superior to other insects and animals, as has long been the case within dominant branches of scientific thought and practice since the enlightenment.

The very concept of the umwelt theory is however anthropocentric, in that we are bound by our mode of communication and experience of the world. Literature, our current source of communication, tends to simplify reality by reducing the richness and complexity of objects and their relations to mere representations. Similar to Uexküll, Graham Harman in ‘Object Oriented Ontology’ asks us to flatten everything (objects and living beings) onto the same ontological plane. Here ‘everything that exists must be physical..’ Where his ideas differ is that he believes objects exist independently of human perception and possess their own inherent properties

47

and relations. Norton challenges the notion that literature can fully capture the intricate essence of objects, their withdrawn reality, and their non-human agency. Highlighting the need to move beyond anthropocentric interpretations and recognize the independent existence and significance of objects in themselves, unmediated by human perception or literary depictions. The intangible ontological nature of our consciousness is eluded by any of our attempts to objectively conceptualise it. The same is true when conceptualizing the phenomenological experiences of a tick. We can only attempt to think beyond our own sensory world through art & poetry. It’s through these forms that we are able to ‘concretize those totalities which elude science, and may therefore suggest how we might proceed to obtain the needed understanding.’ (Norberg-Schulz, C, 1996)

Uexküll raised important ontological and epistemological questions which inspired critical thinking (beyond Darwinism) in biology, philosophy and beyond. Although there are still large parts of scientific logic which hold there is one objective reality, which can be measured and studied independently of subjective thought.

It is important to understand that we occupy a particular place in time and space, which comes with our own singular experience, and this experience cannot lead us to knowledge of everything, objectively. Remembering to consider the phenomenological experience of non-humans, as Uexküll does with the story of the tick, helps to prevent us from being so ‘easily deluded’ as to believe ‘the widespread conviction that there is only one space and one time for all living things’ (Uexküll, 1957, p11).

48 Composting is

so hot

Anthropocentric Suicide Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

Human-centered design perpetuates a culture of anthropocentrism that places human needs and desires above the needs and desires of other beings, leading to ecological and social imbalance. (Plumwood, 1995)

— Val Plumwood (1995) sustainability

In 2022 more than 33million people were affected by the unprecedented flooding in Pakistan, 20 million people still require humanitarian assistance, 10 million of which are ‘deprived of safe drinking water’ (Unicef, 2023). Here, in England, 2022 was the ‘warmest year on record in 364-years’ (Metoffice, 2022) and ‘15 of the UK’s top 20 warmest years on record have all occurred this century –with the entire top 10 within the past decade’ (BBC, 2023).

The climate crisis threatens human existence, and yet it has been increasingly fuelled by the existence of humans. Anthropocentrism has neglected the planet’s health and has permeated our every practice, especially in the construction industry which contributes to ‘36% of global final energy consumption’ (UN Environment Programme, 2021). From laying bricks to heating our homes the residential sector in the UK is directly responsible for ‘22% of total emissions,’ of which, 45% is attributed to space heating alone (BEIS, 2020).

49 9

How Ecocentrism and Anthropocentrism Influence Human-Environment Relationships. (Rulke et al. 2020)

50 Composting is so hot

Anthropocentrism is a fundamental distortion of the relationships among entities in the universe, a distortion that has led to the ecological crisis we face today. (Morton, 2017)

Specifically, Timothy Morton refers to the failure of humanity to recognise the balanced ontology of all objects; the interdependence of all things in the universe. Failure to recognise this interconnectedness, is failure to acknowledge and address what Morton describes as Hyperobjects; objects so massive in spatial and temporal scale they are difficult to comprehend but have very real impacts on humanity. Climate change is a hyperobject woven throughout our politics, social systems and economies; it’s a sum of billions of minute actions that have culminated into a planeteffecting object. The embracing of anthropocentrism is the neglect of the agency of the objects that fill our universe and occupy our planet. In tangible terms, the embracing of anthropocentrism is the neglect of our planets health. It is now thoroughly accepted human activity is directly responsible for the climate crisis, contributing to the unprecedented levels of carbon dioxide that is unforgivingly shaping our planet’s atmosphere and all the ecosystems within it. Now, more than ever, humanity is being devastated by global warming; Concern Worldwide notes, ‘compared to the period between 1960 and 2010, the average number of floods over the last decade have increased by more than 75%. The prevalence of wildfires has doubled, and the average number of droughts each year since 2010 has increased by 57%. In 2019, the number of climate-related disasters was 237. The annual average between 1960 and 2010 was 146.’ (concern worldwide, 2022).Human behaviour can be explicitly attributed to the exponential damage of our climate, and in turn is responsible for the human suffering at the hands of global warming. If we are to tackle the climate crisis we must first address our anthropocentrism.

The construction industry is a pertinent example of anthropocentric design fuelling the looming urgency of climate change. The cement industry alone is responsible for 8% of global

51

CO2 emissions (BBC, 2018), and is found in almost every construction project across the world. Cement is an ingredient of concrete, a vital building material responsible for the quick construction of our cities; 15.2 million metric tons of cement was consumed in the UK in 2020 (Statista, 2022), amounting to 12.6 billion tonnes of embodied carbon. This sum is dwarfed, however, by China’s cement consumption of 2.5 billion metric tonnes in 2021, over half of the United States’ total cement consumption throughout the 20th century (4.9 billion tonnes) (Ritchie, 2023). While cement is a versatile building material often credited for its strength and durability, its overconsumption is mainly a result of its relative low cost when compared to more sustainable alternatives. Anthropocentrism prioritises cost over the ecological damage of cement, and despite a plethora of examples that showcase the successes of alternate methods, it continues to be a favoured building material. CLT is a vastly more sustainable alternative to its concrete counterpart, offering a reduction of up to 60% in embodied carbon (Dr Morwenn Spear, et al, 2021) and faster on-site installation due to prefabricated panelling. In East London, Dalston Works is a 10 storey residential development with 121 apartments and balconies alongside courtyards and restaurants. With of 3,852 cubic metres in volume (dezeen, 2023), its entire structure is manufactured from cross-laminated timber and currently stands as the largest CLT construction in the world. Dalston Work serves as an example of the mass scale CLT can achieve, and demonstrates the overreliance on cement and concrete throughout the rest of the industry. If we are to reduce our reliance on cement, we must expand our use of renewable materials and focus on producing more ecocentric construction methods.

Following a building’s completion, space heating demand is the next largest contributor to the construction industry’s overall energy consumption, and further highlights the anthropocentrism of architecture. Only recently has the idea of Passivhaus become a popular and rising form of architecture that respects the ontological relationship a building has with its environment. Passivhaus provides

52 Composting is so hot

a series of measures that work towards a carbon neutral entity which often give back to its habitat rather than exploit it. The average space heating demand for a residential scheme in the UK is 145 kWh/ m2, over 9.5x the Passivhaus target of just 15 kWh/m2. Passivhaus achieves this significant improvement through meticulous attention to air tightness and a focus on insulation throughout the home. The use of heat pumps regulate internal temperatures in response to external weather patterns, ensuring optimal thermal comfort levels throughout the year, without requiring intense energy to quickly rise or drop temperatures. There is a harmony between the human habitat and the surrounding natural world, emphasising an ontologically equality between the human and the environment. There is also a keen attention to the agency of materials, with a particular focus on renewable resources such as timber – creating welcoming homes that draw on our innate connection with nature. Materials are not reduced to just their structural qualities, instead they are interrogated on their effects on the ecosystem, their lifespans and even locality to the scheme within which they will be a part of. Passivhaus demonstrates there are reasonable alternatives to traditional means of construction that respects the interconnectedness of architecture and the environment. In more urban landscapes, like dense cities, retrofit architecture can be used to alter previously anthropocentric buildings into ecocentric spaces moving forward. As the ecological damage of the construction of these buildings has already been established, they should be used as a foundation for further development, rather than be demolished for newbuild projects. Retrofit architecture can be built to the standards of Passivhaus and therefore can exercise an ontological approach to future architecture. Passivhaus and retrofit approaches to design can address the needs of anthropocentrism while considering the ontological importance of the objects that create our world.

In order to address the daunting inevitability of our climate crisis, humanity must first confront its anthropocentrism. The construction industry must reduce its 36% annual contribution to global carbon

53

dioxide emissions and be used as a beacon of an ecocentric approach to the balance between humanity and its environment. Sustainable design methods like Passivhaus and Retrofit architecture, should lay the foundations for a more ontologically considered built landscape, reinstating a harmony between the human and the environment. It is in the anthropocentric interest of humanity to revaluate its position amongst natural world.

54 Composting is so hot

Luxury Value: And Subtitle if it has one and runs on to two lines

In a world where everything is shopping… and shopping is everything… what is luxury? Luxury is not shopping.

— Rem Koolhaas (2001, p4)

Luxury is: Attention, ‘Rough,’ Intelligence, ‘Waste,’ Stability.’

— Koolhaas (2001, p. 57)

that bag

Luxury has always been something that nobody needs. One’s survival in the world has never been dependant on it. Luxury therefore liberates it self from any formal grid work, becoming a form of loose entertainment. Its psyche is easily influenced in that it can be reversed, edited and re-shuffled at any given moment. It prefers context over object - the generated representation of a certain lifestyle that creates a strong desire of ownership. How did we end up buying into something physical based purely on its non-physical counterpart?

In the beginning of the new millennium, luxury fashion met architecture in one of the most potent forms of collaboration the world has seen. OMA/AMO and Prada begun their creative endeavour in simultaneously trying to translate the then present condition of luxury and commerce into a series epicentre stores in America. The project evolved into a series of innovative brick and mortar stores and a book documenting the process behind certain decisions and definitions.

55 10

56 Composting is so hot

Content, 2004, Rem Koolhaas

Content, 2004, Rem Koolhaas

Indefinite expansion represents a crisis: in the typical case it spells the end of the brand as a creative enterprise and the beginning of the brand as a purely financial enterprise. (Koolhaas, 2001, p. 4)