from the banks of chalk streams Championing churchyard nature

we’re bringing precious habitat back to life

from the banks of chalk streams Championing churchyard nature

we’re bringing precious habitat back to life

Norfolk Wildlife Trust is a charity dedicated to all aspects of wildlife conservation in Norfolk. Our members help us to create a county where there is space for nature to thrive and more people are inspired to take action for nature.

Thank you so much for being a member. Why not give the gift of wildlife to someone else? A gift membership is a unique present for wildlife watchers, outdoors enthusiasts, or families keen to explore Norfolk further. We can even post a welcome pack with a message directly to the recipient on your behalf. They will also receive three copies of Tern each year, access to local events, and be able to explore NWT nature reserves for free. Visit our website to buy your gift or call 01603 625540.

If you’re not already a member of NWT, please join us today by visiting our website, calling our friendly team using the details below, or asking a member of staff at one of our visitor centres. Help us create a wilder Norfolk for all. norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/Join or 01603 625540

Tern is published three times a year by Norfolk Wildlife Trust. Advertising sales by Countrywide Publications.

Printed by Micropress Printers Ltd.

Editor: Vicky Boorman

Designer: Hannah Moulton

While every care is taken when accepting advertisements neither Norfolk Wildlife Trust nor Countrywide Publications can accept responsibility for unsatisfactory transactions that may arise. The views expressed in this magazine are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of Norfolk Wildlife Trust.

NORFOLK WILDLIFE TRUST

Bewick House, 22 Thorpe Road, Norwich NR1 1RY, UK

T: 01603 625540

E: info@norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk

All contents © Norfolk Wildlife Trust. Reg Charity No: 208734

Cover photo: Creative Nature/iStock

Despite this being our summer Tern, we have a watery theme running through the issue! Our cover story focuses on the wonderful wetland work that has taken place across NWT Roydon Common and Tony Hallatt Memorial Reserve. Restoring the natural water flows across these nature reserves has created a flourishing wildlife-rich wetland that is also more resilient to future changes in our climate, read more on p22.

Plus, we also celebrate our wonderful chalk streams (p18), shine a spotlight on the water scorpion (p10) and delve into the rich marine life of the North Norfolk coast (p28).

Increasingly, our work involves finding creative solutions to a changing world. Hundreds of years ago, our beaches may have been safe places for beachnesting birds. Yet the modern world means that they now face numerous

challenges when trying to raise a family. Turn to p16 to read how we’re working in partnership along the coast to give these birds a fighting chance.

I’m sure you’ll agree that a peaceful churchyard can be a wonderful place to stop for a picnic on a summer’s day. Our partnership with the Diocese of Norwich means that across Norfolk, nature is blossoming in these oftenancient green spaces — find out more on p30. And if you’d like to get involved, why not take part in our churchyard Spotter Survey on p34?

As ever, thank you so much for your continued support. We hope you have a wonderful summer and find inspiration for places to visit and wildlife to discover in these pages.

Eliot Lyne, Chief Executive

Alternative ways to read Tern The magazine can be read on our website as a text-only document. You can make changes to font size and background colour, for easier reading, and enjoy Tern using a screen reader. This issue is available to download at norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/PlainTextTern

Biodiversity in the Brecks has received a boost thanks to a translocation project led by the charity Plantlife, which involved moving a rare lichen from Cornwall to NWT Weeting Heath.

Scrambled egg lichen, Gyalolechia fulgens, which resembles a plate of scrambled eggs due to its bright yellow, crumbly appearance, is one of three specialist lichens lost to the region. Along with starry Breck lichen and scaly Breck lichen, scrambled egg lichen became extinct in the Brecklands due to habitat loss. This was a result of changes in farming, an increase in tree cover and a loss of rabbit grazing.

The technique used to move the species, known as translocation, involves carefully removing small patches of the lichen from one area and using either water or book-binding glue to reattach them in another.

Two hundred small pieces of the lichen — about the size of a 20p piece — were removed from Penhale in Cornwall and 160 transplanted into the Breckland chalky landscape.

A section of undulating ground at Weeting Heath, known as ‘The Washboard’ was created nearly 20 years ago as a refuge for several rare lichen species. James Symonds, NWT Warden at Weeting Heath, has been working alongside Plantlife to ensure the lichen settle in well at their new home. ‘We’ve been hugely lucky to work with Plantlife on several occasions across our Breckland reserves and partner with them on the fantastic work they’ve carried out, changing the fortunes of many rare and special species. Bringing back scrambled egg lichen to the Brecks is exactly the kind of project we want to see more of in the region. We hope the future continues to look sunny side up for lichens here.’

Norfolk Wildlife Trust is proud to be taking part in Norwich Pride this year. We will be supporting and celebrating LGBTQIA+ staff, volunteers, supporters and visitors by taking part in the Pride procession on 26 July. Find our Wilder Learning team on one of the stalls, encouraging families and young people to explore the diversity in nature through interactive activities. If you see us, please come and say hello!

Additionally, you can look forward to our own Pride-inspired events taking place the week leading up to the celebration, including a free guided walk with a picnic at NWT Sweet Briar Marshes (24 July, book via our website) and an LGBTQIA+ Leaders in Nature Conservation and STEM Panel Discussion chaired by our ambassador Nick Acheson at Norwich Arts Centre (22 July, tickets via NAC).

We are delighted to share the news that we have been able to purchase two new plots of land bordering NWT Foxley Wood thanks to support from generous donors, including two significant legacies left to the Trust by Graham Churchyard and Adrian Gunson.

These generous gifts have allowed us to expand Foxley Wood, which is home to Norfolk’s largest ancient woodland, by an amazing 100 acres — increasing its size by over a third.

In addition to creating vital new wildlife habitat for some of Norfolk’s rare plants and animals, this significant land acquisition will allow Norfolk Wildlife Trust to expand public access to the popular site.

Steve Collin, Norfolk Wildlife Trust Area Manager, said: ‘We’re immensely excited about creating more space for wildlife at Foxley Wood. As Norfolk’s largest ancient woodland, it is a vital refuge for some of the county’s rare plants and animals.

‘As well as assisting with the natural regeneration of new woodland, to ensure our new land supports as much wildlife as possible, we’ll create a mosaic of habitats including scrub, grassland, woodland rides and ponds.

We are pleased to announce a brand new collective of young people aged 16–25, each with a passion for supporting Norfolk’s wildlife. This newly hatched group includes 17 members who will meet monthly to manage Sloughbottom Meadows, our first youth-led nature reserve situated in Norwich.

Over the next two years, the Youth Forum will take over the seasonal management of the six-acre County Wildlife Site and help maintain the meadows and woodlands for wildlife and the local community. With support from The Norwich Fringe Project, members will carry out meadow-cutting and raking, coppicing and habitat creation, as well as wildlife surveys, litter picks and creating interpretation for visitors.

Youth Forum members are located across the county, from Gorleston to Aylsham to Norwich. The group brings an

‘As the new woodland evolves, it will fill up with nectar-rich plants and young scrubland trees which are ideal for pollinating species and provide important nesting and feeding grounds for birds and bats. The maturing woodland will, in time, support the woodland specialist wildlife that Foxley is known for — including bluebells, butterflies such as purple emperor and silver-washed fritillary and birds including tree creepers and nuthatches — allowing them to spread out from the ancient woodland.’

The new land links Foxley Wood to the Marriott’s Way, making it the perfect spot to offer new public access to the site. By connecting the nature reserve to NWT Sweet Briar Marshes in Norwich, we will create new and ecofriendly ways for people to enjoy some of Norfolk’s most special wild places.

Find out more: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/ FoxleyExpansion

exciting array of skills and experiences, including writers, activists, musicians, conservation students, artists — and many who have never taken part in wildlife conservation projects before. This is an opportunity for young people to learn conservation skills, experience leading an ambitious project and connect with like-minded enthusiasts; we can’t wait to see members grow and develop in their new roles.

Our Youth Forum is part of the Building Foundations for the Future project, which is funded thanks to support from National Lottery players and The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

In 2023, thanks to a generous legacy and donor support, we acquired Mere Farm, a 130-acre site that borders with NWT Thompson Common. We could see the huge potential of the land for enhanced habitat creation, especially to encourage the northern pool frog to expand its range from its stronghold at Thompson.

Over the last two years, thanks to funding from Natural England’s Species Recovery Programme Capital Grants Scheme, match-funded by the Banister Trust, we have successfully worked alongside the Woodland Trust and the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust (ARC) to create a tapestry of wildlife habitats on our adjoined land surrounding Thompson Common.

Providing the perfect habitat for the globally rare northern pool frog has been at the heart of this project. With advice from pool frog experts at ARC and our skilled digger operator, we have excavated six ghost pingos at Mere Farm — and just over the fence at the Woodland Trust-owned

Green Farm, we have supported the restoration of a further eight.

Enhancing the habitat surrounding the newly restored pingos, with the aim of reinvigorating depleted agricultural soil into species-rich grassland and natural scrub, has also been an important part of our work. Anglian Water Flourishing Environment Fund generously provided the money for a useful piece of kit that helped speed up the process. Conservation grazing will be essential here in the future, so we have installed new fencing to enable this to happen.

‘It’s stunning to see how quickly the new pingos have gone from bare earth and water to having a long list of species from water beetles to pond plants,’ says NWT’s Nature Conservation Manager Jon Preston who’s been overseeing the project. ‘It’s only a matter of time before the northern pool frogs take the short leap from Thompson to find new homes next door. And it’s vital that they do, so that this ultra-rare species is more resilient in the future.’

‘This project has been exactly what is needed for pool frog recovery,’ says John Baker from ARC. ‘It has created and restored pond habitat at a landscape scale — and this has only been possible by combining our shared knowledge and expertise. We hope that our work will enable the frogs to expand their local range — creating several, linked populations, improving the resilience of the population reintroduced initially almost ten years ago.’

We have been blown away by the response to our Norfolk’s Nature Needs a Home appeal, which you will hopefully have read all about in the spring issue. Incredibly, at the time of writing, you have donated over £35,000 to help give nature a home in Norfolk. Thank you so much!

Thanks to meticulous work from our staff and volunteers, a highly invasive plant has been eradicated from the pingos at NWT Thompson Common, allowing native plants and species to flourish.

Thompson Common pingos are some of the most biodiverse in Europe and support many scarce species, many of which aren’t found anywhere else in the UK. Unfortunately, some of the ponds were threatened by a non-native plant, Crassula helmsii, aka Australian Swamp Stonecrop. Crassula can form a dense mat across a pond’s surface that can prevent many other plants from growing, as well as removing food plants for many organisms and lowering oxygen levels. Left unchecked, the invasive plant would have spread into many of the ponds and wetland areas.

Funded for the first two years by Anglian Water Invasive Non-Native Species Fund and the past two years by Natural England’s Species Recovery Programme Capital Grants Scheme, the project aimed to find and remove all the crassula at Thompson Common — reducing it to a level where it could not spread or impact biodiversity.

NWT’s Crassula Officer, Julia MumfordSmith, led the ambitious project. ‘Crassula is notoriously difficult to eradicate,’ she says. ‘Some ponds had large amounts of the plant which

were easy to see but we suspected it had spread to other ponds in small amounts. We wanted to find these and eradicate them before they got established and became extremely difficult to manage. With the help of volunteers, we searched over 1,276,369 square metres [equivalent to 187 football pitches] looking for a plant that can be 1cm tall, hiding amongst lush sedges and vegetation.

‘It is fantastic to see the diversity of plants and animals return to the areas that were infested by thick mats of crassula,’ continues Julia. ‘Those areas are now a garden of water violet, tubular water dropwort, bladderwort and rare stoneworts with scarce liverworts floating past, stirred by the movements of water vole, water shrew, great crested newt, huge water beetles and the northern pool frog.

‘I would like to thank the 43 volunteers who gave their time to this project and worked relentlessly throughout the year including through icy winter weather and scorching summer heat to protect the fantastic wildlife of one of Norfolk’s most special places.’

Eradicating crassula at Thompson Common will also reduce the risk of the species spreading into the newly created ponds on land surrounding the nature reserve — see our story on page six for more.

Along with your donations have come inspiring messages of hope and love for wildlife and wild

Your chance to feature in our 2026 calendar and exhibitions!

We want to see your best images of Norfolk’s birds, mammals, marine life, bugs, plants, fungi and landscapes — taken anywhere, from one of NWT’s nature reserves to your own garden within the past year. Photographers with any level of experience are encouraged to share their vision of Norfolk’s amazing nature, with images taken with professional cameras or mobile phones welcome! The competition, running from 7 June–21 July, is free to enter and open to all ages.

Emperor dragonflies by last year’s winner Stuart Merchant

The competition will be judged by an exciting line-up of talented East Anglian photographers, including Megan James, Jimmy King, Fiona Burrage and Alfie Bowen, along with a young person from NWT’s Youth Forum.

Judges will select a favourite photograph for each month of the year to be printed in Norfolk Wildlife Trust’s 2026 calendar, with a selection of the best photos also being shown in an exhibition at NWT Cley Marshes and The Forum in Norwich.

An Overall Winner, Young Person Winner, and Mobile Phone Photography Winner will also be chosen, with winners receiving a prize from a range of fantastic specialist and local businesses, including a top prize of SFL 8x50 binoculars (RRP £1,850) from Zeiss, along with goodies from Norfolk-based businesses Lisa Angel, SOP and WILD Sounds & Books.

Norfolk’s adders need our help! ‘This iconic Norfolk species is nationally in decline, and we suspect that some populations here are struggling or have been lost in recent years,’ says Helen Baczkowska, NWT’s Conservation Research and Evidence Manager. ‘Norfolk and Suffolk were once strongholds for adders, but we have gaps in our knowledge about these secretive creatures, with some suitable habitats lacking records.’

As a first step, we have helped form a partnership with Suffolk Wildlife Trust, Natural England and Amphibian and Reptile Conservation to find out more about adders, where they are and how we can help them to thrive. ‘Good evidence is needed to make sure we make

the right decisions,’ says Helen, ‘and we’ve been surveying adders so we understand more about their preferred habitat. I never thought I’d find myself trimming scales from an adder’s shed skin to assess genetic health!’

The partnership has also supported workshops for land managers — spreading the news on what adders need to flourish. ‘So much of this’, says Helen, ‘connects with work we’re already doing at NWT, ensuring habitats across Norfolk are well cared for and connected by corridors like hedges or rough grassland’.

To enter

Submit up to three of your best images, taken in Norfolk within the past year, at: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/ PhotoComp. Entries are open 7 June–21 July. Please read the competition rules on our website before entering.

county’s key species and directs our efforts to monitor and assess the impacts of our work for wildlife.

Adders have been identified as a key priority within our new Species Recovery Framework. The Framework will help guide how we support our

Read more about our Species Recovery Framework: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/ SpeciesRecovery

Although they resemble scorpions, with their large, brown, leafshaped body and pincer-like forelegs, water scorpion — Nepa cinerea — are in fact members of an insect group called Hemiptera, or ‘true’ bugs. They are common and well distributed across the UK, and as their name implies are found in well-vegetated ponds or gently flowing streams. Their long straight tails act as a breathing snorkel, rather than a sting. They can be found year-round in Norfolk ponds feeding on other insects, tadpoles and small fish; often concealing themselves in thick vegetation. Like all bugs, they have

a straw-like mouth, called a rostrum. The water scorpion grabs passing prey, injecting it with a powerful digestive enzyme. It then sucks out the poor creature’s liquified innards.

The adults will leave the water, and at night they can often be found around the margins of ponds. Water scorpions can fly, although they have rather underdeveloped wing muscles for their size, but they will, if necessary, leave a pond to find new territory. Even a small garden pond may be home to a water scorpion, alongside other underwater predators, such as the water stick insect.

Lesser white-fronted geese

This winter will go down in UK birding history for the unprecedented arrival of lesser white-fronted geese to Norfolk, says photographer and writer Robin Chittenden.

Norfolk is famous for its wintering geese, especially the thousands of pink-footed geese that mainly breed in Iceland. A few hundred greater whitefronted geese also winter here, although milder weather means many now remain in Northern Europe. The lesser white-fronted goose has always been an extremely rare vagrant to the UK but is now even more so, due to a huge decline in the European population.

In the 1970s, Project Fjällgås* began in Sweden with the aim of breeding and releasing lesser white-fronted geese into the wild to revive their collapsed population. The last few years have seen the project team’s hard work pay off, and they quote: ‘a minimum of 100 young lesser white-fronted geese have fledged in the past four years, compared to just over 30 in the previous four years’.

‘‘ The lesser whitefronted goose has always been an extremely rare vagrant to the UK but is now even more so, due to a huge decline in the European population.

These birds then usually go on to winter in the Netherlands and Germany, so imagine the jaw-dropping moment when a flock of 24 lesser white-fronted geese was found at RSPB Titchwell this winter, moving on to Ken Hill Marshes. This wasn’t the end of it though, nine more were found between Wighton and Warham, later moving to NWT Cley Marshes and then seven more were found at Stiffkey!

Coloured rings on the legs of these birds confirmed them as having originated from Sweden. They were in family groups, and as the juveniles learn migration routes from their parents, could this be the start of the establishment of a regular wintering flock in Norfolk? But why did they come here in the first place? Perhaps they got lost in foggy conditions and inadvertently crossed the North Sea, helped by favourable winds. No-one will ever know, but they must have found Norfolk to their liking as they spent the whole winter here. If they do come back next year, do try and see them. They have an endearing high-pitched gabbling call

compared to the noisy oinks of the pink-footed geese and the greylags.

Some of the wintering favourites stayed for the whole winter. The female pallid harrier was regularly seen in the afternoon at Warham Greens and was occasionally seen during the day nearby at scattered locations including North Point Pools (Wells-next-the Sea), Stiffkey, Warham, Wighton and Sustead.

Shore lark remained a firm favourite with birders. They were spotted virtually every day at two favoured wintering spots — Holkham Gap and between Old Hunstanton and NWT Holme Dunes.

Adding a splash of colour, a glossy ibis wintered at Stiffkey and another at Burgh Castle. Inland, a red-necked grebe was spotted at NWT Thorpe Marshes, a Slavonian grebe at NWT Hickling Broad and single great northern divers appeared briefly at Wroxham and NWT Barton Broad.

The start of the warm weather saw the emergence of a few butterfly species including many brimstones. The wings

almost white, males have yellow-green underwings and yellow upperwings. A few adders were spotted emerging from their hibernacula.

*jagareforbundet.se/Projekt-fjallgas/english/ Some conservationists are opposed to the Swedish releases. Read more: piskulka.net (populations/translocations)

Kyle explains how he progressed into his role, why his days never look the same and what he loves about working in the Broads

I’ve always wanted to work outside doing something practical. After university, I spent a year working odd jobs and volunteering, building practical skills and increasing my natural history knowledge. I secured a traineeship with Sussex Wildlife Trust and received certifications in chainsaw, first aid, tractor and more, which allowed me to work on different types of land.

I then became Reserve Assistant in the Brecklands with NWT. This was a fantastic opportunity, allowing me to build the foundations of my career working on a unique landscape. I later became Lead Officer, then Reserve Manager. I’ve been in my current role for a year and still loving learning new things.

Although my current job is less ‘on the ground’, I still manage to get out

on the reserves to undertake habitat management, such as fen and reed cutting, scrub work or infrastructure repair. As well as supporting our Broads teams, I ensure site management plans are kept updated and that we meet our obligations and agreements. We’ve got some incredibly special nature reserves in the Broads, providing a home to some of the UK’s most threatened species, and it’s a privilege to have a role in ensuring they thrive.

I also work on larger scale projects, such as how we can manage challenges that climate change brings, as well as those based on the restoration or management of new sites that NWT takes on. Some projects will long outlive me, which is so exciting. I also liaise with partners and neighbours. A big part of NWT’s strategy is to expand the land available to nature through better connectivity, so partnership working is vital.

I love the varied nature of my role. I might be out conducting a bittern survey or working with the reserves teams to find new ways of managing difficult tasks. Other days, I could be developing a large-scale project to secure the future of our sites or working with neighbouring landowners to build a better-connected landscape. Spending time out on the sites — seeing, hearing and feeling the tangible benefits of our hard work — is the best part of all.

The best way to get into a job like mine is to be enthusiastic and get as involved as possible. I know it’s not always that simple but volunteering really got me where I am today.

I love spending time outdoors in my own time too, whether that’s kayaking in the Broads or mountain biking, climbing or walking!

Imagine

Become

Exclusive holidays for life An initial payment from £5,000 and a quarterly fee of under £38 (that is around £150 a year), which can increase in line with but not exceed the Retail Price Index Excluding Mortgage Interest (RPIX), gives you access to all HPB’s holiday homes. For each HPB holiday, you will pay a no-profit user charge covering only property running and maintenance costs and use of on-site facilities. The average charge is the same throughout the year, the average weekly charge for a studio sleeping two is around £372 and around £569 for a two bedroom property, larger properties are also available. After an initial charge of 25% your money is invested in a fund of holiday properties and securities. The fund itself meets annual charges of 2.5% of its net assets at cost, calculated monthly. Your investment return is purely in the form of holidays and, as with most investments, your capital is at risk. You can surrender your investment to the company after two years or more (subject to deferral in exceptional circumstances) but you will get back less than you invested because of the charges

well as other

and changes in the

of the

and

Beach-nesting birds face many challenges, but we can all help to protect them, says Nature Conservation Officer Robert Morgan

Our county’s wonderful stretches of wide, open beaches are, understandably, a great draw in summer for both visitors and locals. North Norfolk’s Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty designation is not only for its delightful views, but the incredible wildlife too. However, the popularity of our beaches, including those classified as nature reserves, places increasing pressure on them.

Three species of Norfolk beachnesting birds, the ringed plover, oystercatcher and little tern are at risk from increased disturbance, and their vulnerability has led to a gradual decline in their populations. Hundreds of years ago, when our coastal beaches were vast lonely places, they were

Can you spot the ringed plover nest?

a sensible and safe place to nest. The modern world means that these birds now face numerous challenges when attempting to raise a family. General human disturbance can prevent them settling, and accidental damage, by an unsuspecting foot on their well-camouflaged eggs, is sadly a likely possibility.

Dog ownership continues to grow in the UK, and off-the-lead dogs on our beaches, which nesting birds find particularly threatening, is an increasing and significant problem. This never-ending encroachment means that our beach nesters become squeezed into ever-decreasing areas, and this can result in higher occurrences of natural predation. Rising sea levels and more frequent summer storms also prove an issue.

However, help is on hand and, with the cooperation of all beach users, these beautiful seashore birds can be saved and hopefully helped to recover. Around the coast of Norfolk, conservation organisations, including the National Trust, RSPB and Norfolk Wildlife Trust, collaborate to help protect these precious, but highly vulnerable birds.

At NWT Holme Dunes nature reserve, staff and volunteers ‘rope off’ three areas to protect shore-nesting birds. One of the most obvious and vocal is the little tern. Arriving with us in April, after a winter spent on the west coast of Africa, the little tern is a dainty bird, often referred to as a sea-swallow. And like the more familiar blue-bird, it has a long, forked tail and swept-back wings. It is pure white, with powder-grey wings and a black crown. Unlike any other UK tern,

Ringed plover; left: ringed plover adopting ‘broken wing’ behaviour

‘‘ Norfolk is an important county for nesting little tern, with almost half of the UK population (roughly 700 pairs) attempting to nest in scattered colonies around our coast.

it sports a bright yellow bill. Norfolk is an important county for nesting little tern, with almost half of the UK population (roughly 700 pairs) attempting to nest in scattered colonies around our coast. During the spring and summer nesting season, NWT has a team of volunteers patrolling Holme Dunes beach. Along with recording bird behaviour and nesting activity, the volunteer wardens help the public to understand the problems these birds face.

As well as little tern, the Holme beach volunteers keep a watchful eye on oystercatchers and ringed plovers too. The oystercatcher or ‘sea-pie’, as it was once known, is the most conspicuous wader on the beach. It has bold black and white plumage, carrot-coloured bill and pink legs. Gary Hibberd, NWT Holme Dunes Reserve Warden, has a few pointers on recognising oystercatcher and ringed plover behaviour when they are disturbed at the nest or with chicks. ‘The oystercatcher is a noisy bird during the summer, especially when incubating eggs and rearing its young — an indicator that you may be too close to a nest or chicks. The ringed plover is a smaller, compact bird, it has a white belly and light brown wings, a black breast band, black and white face, with a brown crown.

The ringed plover has probably suffered the most due to seaside recreation. Gary stated that its behaviour is very different to the oystercatcher. ‘It will hurriedly leave the nest, with a worried ‘puew’ call, hoping to draw you away. When they have young, both adults will be ‘panic-stricken’, often adopting the ‘broken wing’ behaviour, a sure sign they have young nearby. Ringed plover chicks feed themselves, and it is during this period that they are most vulnerable. At Holme Dunes they often choose to forage on the upper strandline or around the muddy pool away from the cordons.’

Help us protect beach nesting birds at the coast this summer

1

Keep away from fenced-off breeding bird areas.

2

Follow signage and guidance from beach wardens to minimise disturbance.

3

Keep dogs on leads in areas where you are asked to and responsibly dispose of dog mess.

4

Be mindful in all areas of the beach and stay clear of breeding birds and their fledglings.

Learn more about the magic of chalk streams and what you can do to protect them with NWT Conservation Research and Evidence Manager

Helen Baczkowska

Arecent look at a map of Britain’s chalk rivers gave me a surprise. Without realising it, I have, it seems, lived several years of my life near waterways that rise from the chalk bedrock of southeast England. Some of my earliest memories are of my grandparents’ bungalow on the banks of the Colne near London. I remember, just, being drawn to the peace of the riverbank and watching long strands of green weed moving gently in the current.

As a student, I lived a few metres from the Stour in Kent and walked miles along its banks seeking kingfishers, yellow water lilies, and brief glimpses of brown trout rising lazily to the surface. Before moving to Norfolk two decades ago, I lived in a nearly derelict water mill in Hampshire, the disused part of which spanned the wide river Test. In autumn, people used to stand by our front door watching the spectacle of salmon leaping upstream. The silver fish, some as long as my arm, often had to try several times to make it through the old mill-race, their tails and muscular backs emerging briefly from the water to gasps from their audience. In early summer, I could sit in the back garden watching mayflies dip and rise above the white flowers of water crowfoot, whilst a family of water voles crouched in a line on the bank with their young. Later on, I moved a few miles to a house on a lane that forded the Meon — a smaller and quieter river than the mighty Test. One midnight, a friend and I were watching badgers in the old water meadows behind the house when we heard the clear and unmistakeable whistle of an otter. We knew that the species had been declared extinct in the county a few years before, but here they were, whistling their return through the dark.

Now I find myself living not far from the Tas, which runs northwards through the South Norfolk Claylands towards Norwich. Like the Meon, it is a river of winter fords, shaded shallows under alder trees and still, quiet pools. I am grateful to the Tas for my best sighting yet of an otter; I was swimming in a

Only around 200 chalk rivers are known globally, 85% of which are found in southern and eastern England. TALES

deep pool one sunlit afternoon when a shape in the water caught my attention. Seconds later, the broad head of a dog otter appeared just a few feet away, his dark eyes looking curiously at me. I held my breath, looking back before he vanished into the water.

Only around 200 chalk rivers are known globally, 85% of which are found in southern and eastern England. Here in Norfolk, they include not just the Tas, but the Wensum, which flows alongside NWT’s Sweet Briar Marshes nature reserve in Norwich, as well as the Bure, the Tud, the Nar and the Glaven to name a few. All of these watercourses emerge from the chalk with pure water that is rich in minerals and remains at a fairly constant temperature year-round — conditions that encourage a wide range

of aquatic plants, invertebrates and fish species. Above the waters, bats and birds feed on insect life and the waterways also create a network of vital corridors for wildlife across the county.

The sheer number of chalk rivers in Norfolk means that we have recently supported a campaign initiated by Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, seeking greater recognition and protection for the rivers. Although the clear waters support so much wildlife, they are sadly vulnerable to human impacts. Many have been overdeepened by dredging, or straightened out and cut off from their natural flood plains, whilst the movement of species like eels has been obstructed by sluices or weirs, and pollution from many different sources remains a threat.

At the end of 2024, Norfolk Wildlife Trust signed a joint letter to Parliament advocating for policy changes to protect chalk rivers. The recommendations made included introducing ‘no development’ buffer zones around chalk streams, considering the implications of sewerage systems in local plans and, crucially, designating chalk rivers and their catchments as irreplaceable habitats. Irreplaceable habitats are those like ancient woodlands, which are difficult or impossible to re-create and that consequently need special protection, especially when new houses or infrastructure such as roads are planned. At the time of writing, our wonderful chalk rivers do not have this protection.

We followed this up by contacting all of our councillors in Norfolk, asking them to sign a powerful open letter to Rt Hon Angela Rayner MP and Rt Hon Steve Reed OBE MP in February this year. Sixty-two councillors from Norfolk joined their counterparts from Hampshire and The Isle of Wight and Wiltshire in supporting the letter calling for greater protections for chalk streams within planning policy.

Norfolk Wildlife Trust will continue to advocate for these irreplaceable waterways, to help give our chalk streams, and the wildlife they nurture, a fighting chance. We will also speak out against developments that could do our chalk streams harm, such as in the case of the Norwich Western Link road.

As we continue with our efforts, we’ll be sure to let you know when you can add your voice to ours. And in the meantime, there is one thing we can all do, whether we swim, bird watch, fish or just enjoy walking along riverbanks. It is simply this — take a moment to see what you can spot living in the river and don’t let these lovely places go unnoticed any longer.

Chalk streams had their moment in Parliament recently when MPs called on Government to introduce protection for these precious rivers via the new Planning and Infrastructure Bill. But meanwhile, other Government action on chalk streams is faltering. A much-needed ‘chalk stream recovery pack’ sets out the key commitments, policy changes and action Government will take to drive forward the conservation of these precious rivers. But it is yet to be published, and risks sitting on a shelf forever more.

A petition has been launched to press the Government to publish the chalk stream recovery pack. At 10,000 signatures, they will have to formally respond to the petition, explaining to the electorate why they don’t think chalk streams deserve special attention.

Find out more and sign the petition: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/ SaveOurChalkStreams

supporting nature conservation since 1988

all our profits are donated to the Wildlife Trusts natural history holidays small friendly groups relaxed pace expert leaders

Estonia: bears & autumn migration

Colombia: Andes & Santa Marta

Chile: Patagonia & Tierra del Fuego

Cyprus: wild flowers at Christmas

Morocco: mountains and coast

France: Dordogne, Cevennes, Vercors

Danube Delta: remote wildlife cruise

Costa Rica: tropical wildlife

Antarctica, Falklands & South Georgia 01954 713575 www.wildlife-travel.co.uk

Traditional Farm - Workhouse Museum - Adventure Playground

Discover Norfolk’s rural history across 50 acres of glorious countryside.

Visit the workhouse museum, farming galleries, chapel, co age gardens, and meet rare-breed animals down on the farm - plus much more!

New exhibition for 2025: Through the Microscope: Secrets of Norfolk’s Changing Landscape with Edible East.

A great day out, whatever the weather!

Wildlife and people will benefit from our ambitious project to create flourishing fens for the future. West Norfolk Reserves Manager Ash Murray tells us more.

Over recent decades, Norfolk Wildlife Trust has done much to restore our Roydon Common and East Winch Common nature reserves. The results have been dramatic, with many species either expanding their populations or re-establishing themselves for the first time in decades.

As well as helping to moderate our climate by storing large amounts of carbon, the peatlands here support a staggering array of rare and threatened species. Many of the most important species inhabiting our peatland reserves have survived in isolation there since the retreat of the Ice Age. They are now exceptionally rare in the lowlands of eastern England, and are more typically found in uplands of the north and west UK. The beautiful woolly feather-moss was locally common in mires until around 6,000 years ago, but has retreated northwards; now Roydon Common is the sole surviving location in lowland England.

The wetlands found across these mires also provide one of the most important locations for breeding waders in lowland

England, whilst the drier heathland habitats support nationally important breeding populations of iconic species, such as nightjar and woodlark, and provide a winter home for a range of raptor species, including hen harriers, merlins and marsh harriers. To stand quietly on the track at Roydon Common on a warm summer’s evening, bathed in the rich scent of heather and bracken, the mechanical churring of displaying nightjars blending with the drumming of snipe and piping of redshank, is truly transformative.

Thanks to a £210,350 grant from the FCC Communities Foundation, as part of the Landfill Communities Fund, we have been able to provide essential spreading room for these species, whilst making their populations more resilient to future change across the adjacent Tony Hallatt Memorial Reserve, Grimston Warren and the Delft. ‘WetScapes’ was a two-year project which started in March 2023 with the joint aims of restoring more natural water flows across these reserves, buffering the effects of climate change and reversing the changes caused by atmospheric pollution.

nature reserves represent one of the most important lowland wetland and heath landscapes in the UK.

A stream meanders its way across the Tony Hallatt Memorial Reserve. Its gently shelving margins are lined with pale, spiky lawns of bristle clubrush and vivid green tufts of fountain apple-moss. The yellow and white flowers of lesser water plantain poke out of the clear water and sticklebacks dart and dash between flowing wefts of stonewort growing on the gravelly streambed. The scene has a timeless quality. However, for more than two hundred years, this streambed lay dry, its life-giving waters diverted into a steep-sided drainage channel.

Restoring this lost stream to its former glory has been a key part of our WetScapes project. Combining different data sources helped us plot its original course. Careful excavation was also vital to ensure we dug down to exactly the right point — known as the ‘drawdown zone’ to ensure it would hold

the required amount of water to benefit wildlife and plants throughout the year.

The beauty of wetland restoration is that results can be rapid and dramatic. Four months after creating the first section of the stream, pied wagtails darted and flitted over the banks catching emerging insects. The first pair of oystercatchers to successfully breed on the reserve chaperoned their gangly-legged chicks along the gravelly banks. Plants not otherwise present on the reserve started to colonise the stream and its margins, including marsh lousewort, marsh arrowgrass and stonewort.

As well as the myriad of benefits to wildlife that the restored stream provides, it also helps to slow water movement through the landscape, attenuating river flows and reducing the likelihood of flooding downstream.

Pied wagtail

‘‘ Four months after creating the first section of the stream, pied wagtails darted and flitted over the banks catching emerging insects.

Mires: actively forming peatlands

Fens: mires that are fed primarily by groundwater (as opposed to bogs that are nourished by precipitation)

Water table: this refers to the level below the ground that’s saturated with water

Drawdown zone: the area at the edge of a body of water that is frequently exposed to the air due to changes in water level

In 1797, William Faden published the first large-scale map of Norfolk (one inch to the mile). This just pre-dated many of the major losses of extensive warrens, heaths and commons. However, even by this time, the stream, which would have previously wound its way across the Tony Hallatt Memorial Reserve, had already been diverted into a steep-sided drainage ditch. In 1945-6, as part of its National Air Survey, the RAF took photos of the same area and these clearly showed the original course of the stream.

By combining these data sources with more recent methods, such as LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), we were able to view in detail the topography of the reserve and plot

the original stream course on the ground. We then took samples of the soil to figure out the exact course and depth of the former stream, using changes in the sediment type (soil layers) to determine the streambed.

Throughout the year, groundwater levels fluctuate. The surface of the water table is exposed to oxygen in the atmosphere and the iron which it contains reacts (becomes oxidised), giving rise to red bands of staining in the soil: a lower band marks the average winter water table and a higher band marks the average summer water table. By excavating below the lower-stained band of soils, we were confident that the pools or streambed we created would remain permanently wet throughout

the year, whereas digging to a point between these bands would result in a water level that gradually decreased throughout the summer. This drawdown zone is critical to a suite of species that have declined in recent decades.

Contractors used specialist machinery to excavate the course of the former stream, creating deeper sections to act as permanent pools along its length. The gradient of the margins of the stream were made as gradual as possible to extend the width of the drawdown zone. Sections of the streambed were raised using excavated material to create leaky dams; creating alternating sections of faster and slower water movement. In other sections, short dead-ended channels mimic natural oxbows.

‘‘ Freed from the smothering effects of purple moorgrass tussocks and nourished by more consistent water flows, these peatlands will once again begin to store carbon.

Although our remaining peatlands in West Norfolk are still of global importance, they have been (and continue to be) significantly damaged by atmospheric pollution, in particular, nitrogen pollution from farming and industry. These pollutants can alter peatland chemistry, damage vegetation, reduce biodiversity and disrupt eco functions — all of which can reduce peat’s ability to store and soak up carbon.

Nitrogen pollution also has another impact. It acts as fertiliser, benefitting the plants that can tolerate higher nitrogen concentrations — at the expense of lower growing, less competitive species.

The most obvious result of this has been the rapid replacement of our diverse fen flora with purple moorgrass; a natural component of our fens that has been pushed into overdrive by nitrogen. It forms closely packed, towering clumps, or ‘tussocks’ that shade out other species and increase water loss from the bog surface.

Changing weather patterns caused by climate change can also stimulate

and amplify the impacts of pollution. Warmer, wetter winters extend the growing season for plants benefitting from increased nitrogen, such as the purple moor-grass. Conversely, species that are poorly adapted to high levels of nitrogen become weaker, leaving them vulnerable during periods of drought.

The WetScapes project has enabled us to restore areas of degraded fen by cutting and removing the dense thatch that has accumulated and stripping off the purple moor-grass tussocks that have smothered the ground surface. This has exposed the wet, bare underlying peat surface, stimulating the germination of a host of fen plants, such as the insectivorous round-leaved sundew and the beautiful, golden-green lesser cow-horn bog

moss. These species will reinitiate the development of peat, helping to store water and thereby reducing the impact of droughts. In doing so, the peatland will once again begin to store carbon, rather than emitting it.

To facilitate this process, we have also installed structures (culverts and earth bunds) into former drainage ditches to restore the natural hydrology of the reserves. This is helping to reduce seasonal fluctuation in the water table, ensuring that the newly colonised peat surfaces do not dry out and that peat-forming bog mosses can thrive. Lapwings, Eurasian curlew and redshanks were quick to respond by recolonising these areas, filling the air with their fluttering, plunging forms as they vocally proclaim their territories.

Round-leaved sundew Left: lapwing

There are now more deer in the British countryside than ever before — and only two of the six species are native. Collectively, they are having a devastating effect on our native flora and fauna; causing a decrease in species diversity by modifying the habitats they require to thrive and through direct removal of species by

The WetScapes project has marked a turning point in the fortunes of these nature reserves.

browsing. To tackle this issue, in the seasonally flooded ground adjacent to the surrounding woodland, we have installed fencing (pictured left) to exclude deer and livestock to allow dense tangles of wet scrub to develop. Flower-rich glades amongst dense tangles of scrub are rare in this county, as muntjac and Chinese water deer have completely removed low-growing vegetation. For species such as nightingale and grasshopper warbler, this meeting of scrub and flora is essential to their survival. To create more of this habitat, we fenced off two large wet areas and will maintain these as low scrub with sunlit glades. These areas already support dense swathes of flowering plants, such as fleabane and tormentil. The presence of wind-blocking scrub will boost the opportunities for nectar and pollen-feeding species, such as the rare tormentil mining bee.

The WetScapes project has marked a turning point in the fortunes of these nature reserves. Freed from the smothering effects of purple moor-grass tussocks and nourished by more consistent water flows, these peatlands will once again begin to store carbon and, in doing so, will support a diverse range of fen plants and invertebrates. Flower-rich, sheltered glades amongst dense, wet scrubland will help to ensure that nectar and pollen-feeding species have a continual food source, even in drought conditions.

What is so wonderful about this project is that we’ve created a flourishing wetland that is also more resilient to future changes in our climate — so good for us, as well as nature.

NWT Marine Project Officer Annabel Hill shares her passion for the rich and varied habitat of the North Norfolk coastline and the species that live here.

Our marine ecosystems are often out of sight and out of mind, yet they are home to some of Norfolk’s most curious and fascinating creatures, as well as diverse habitats. The North Norfolk coastline, with its sand dunes, rockpools and pebble beaches, is nationally recognised as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) — now renamed National Landscape. But this outstanding beauty doesn’t stop at the coastline. Under the waves, when the sun is shining in the summer, the North Sea off the Norfolk coast can be turquoise blue.

Shimmering fish, such as bib and wrasse, can be seen darting and gliding through swaying seaweeds in an array of red, green and brown shades across the white chalk seabed off Cromer

and beyond. Prawns can be found gathering under old structures such as the Sheringham sewage pipe. White and coral-coloured plumose anemone cover the SS Vera shipwreck off Cley, like small delicate trees. If you look closely enough you may see a violet sea slug, whose pinky-purple colour and bright white tips make it look like it has escaped from an enchanted fairytale.

Unlike most terrestrial species, those living in the sea don’t see humans as a threat and typically don’t disappear as quickly as they can. Some are even curious. Prawns will investigate a hand placed gently in their vicinity. Some seem sceptical, like the crabs who will pinch if in doubt, or hunker down in a hole, but there are some that go on the defensive straight away, such as the little cuttlefish — probably my

favourite species, and the one I always hope to encounter because it is so full of character. Little cuttlefish live up to their name, only reaching 6cm in length. Like other cuttlefish they can change colour thanks to the chromatophores in their skin, and squirt ink as a defence to confuse their predators while they make a quick getaway. Mind you, given their small size, a quick getaway for them seems rather slow to a human diver hanging in the water above them.

Most people would be able to categorise a marine mammal, a fish, or a crustacean, but how about a sea mouse? It’s actually a worm, though it resembles a woodlouse — which, interestingly, is a crustacean. Even the little cuttlefish is a type of squid, rather than a true cuttlefish. It’s a confusing world under the sea.

The importance of a healthy marine habitat

These remarkable species, and many more like them, are only here because of the range of marine habitats available to them. All marine habitats are of course important, and even some of the most unexciting — like expanses of mud — play a huge role in carbon sequestration. The Blue Carbon Mapping Project (led by the Scottish Association for Marine Science on behalf of WWF, The Wildlife Trusts and RSPB) estimates that 244 million tonnes of organic carbon are stored in the top 10cm of seabed sediments and vegetated habitats, with over 98% of this stored in seabed sediments like mud. However, one of our most notable marine habitats off our coast is the chalk, sometimes referred to as the chalk reef, which forms part of the Cromer Shoal Chalk Beds Marine Conservation Zone. The reef sits 200 metres off the North Norfolk Coast, starting at Weybourne and ending at Happisburgh. Marine Conservation Zones are protected due to the rare or declining habitats and species found within them.

The marine environment faces numerous threats, many of which mirror those affecting terrestrial species and habitats — such as climate change, habitat degradation, and pollution. Current marine work at NWT includes raising awareness of the wildlife that lives beneath the waves at coastal events, being an active voice for nature at Norfolk’s marine partnership meetings and opposing schemes that would damage marine life.

• Learn more about life under the sea at one of our marine-focused events norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/Events

• Keep a look out for National Marine Week (between 26 July and 10 August) where we’ll have a host of sea-themed events taking place in Norfolk.

• Help marine life from home. Plastic waste has a damaging effect on our seas and natural world. For tips on cutting down on plastic — and lots of other at-home activities go to: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/Actions

‘‘ All marine habitats are of course important, and even some of the most unexciting — like expanses of mud — play a huge role in carbon sequestration.

In collaboration with the Diocese of Norwich, NWT has run the Churchyard Conservation Scheme for more than 40 years. Environment Officer for the Diocese Barbara Bryant tells us more.

How has the Churchyard Conservation Scheme benefited communities?

It’s a wonderful resource to help our parishes and those who look after churchyards and green spaces to do so in a more informed way. They receive hands-on practical help in terms of understanding what they’ve already got and learn how to enrich it further.

In 2024, the Church of England governing body tasked all parishes to draw up simple land management plans, boost their Eco Church survey results for the ‘land category’ and to record the biodiversity of their green spaces. The resources and practical workshops offered by NWT are in complete support of these aims.

Last year, NWT gave advice to 24 church groups, ran four workshops on churchyard conservation and carried out wildlife audits to inform conservation management plans across 30 churchyards — with the help of our wonderful volunteers.

Working with Gemma and Lucy [from NWT] on planning and delivering workshops and conferences. Their enthusiasm is infectious, and they are so engaging in sharing their knowledge and excitement on making discoveries. It’s always a joy!

Want to get involved in nature conservation in your community?

See over the page for our brilliant range of workshops.

How has the partnership with NWT benefited churchyards and nature?

Having such great expertise available locally and in person is what makes the difference. Recently, while giving an ‘eco-talk’ to parishes on the North Norfolk coast, a farmer told me that since I connected him with NWT about molehills in the local churchyard, he’s completely changed his view! He now sees moles as a sign of healthy soil rather than a nuisance. And he’s bringing others on that journey with him.

Taking part in workshops run by NWT means that church groups are enabled to enthuse others.

One church that took part in the annual Churches Count on Nature citizen science event said: ‘Most of the adults attending had never previously visited the church. Even those who had been inside hadn’t explored the burial ground. It was fascinating to see what was hidden under various stones and in the crevices of the church building. A beautiful zebra spider was of particular interest.’

‘‘Having such great expertise available locally and in person is what makes the difference.

What do you hope for the future of the scheme?

I’m looking forward to seeing a growing number of our church communities realising the treasure trove of biodiversity they have on their doorstep. I also hope they come to appreciate how they can take steps to improve and share this with everyone in their locality. We can all contribute to turning the tide on the biodiversity loss in our little patch of Eden. As our Bishop Graham (lead Bishop for the environment) says: ‘My dream is to see churchyards as places for the living, as well as the dead.’

Here’s to the next 40 years!

More information on our Churchyard Conservation scheme and how to get involved:

norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/ ChurchyardConservationScheme

Our exciting 2025 programme is full of talks and practical sessions designed to support and inspire individuals, communities and groups acting for nature in their local area.

Whether you want to raise funds for a community wildlife project, encourage new plants and animals into your local green space, or learn how you can speak up for wildlife on your patch, there is a Wilder Communities workshop for everyone.

Workshops are generously subsidised by donations made to Norfolk Wildlife Trust.

To view all our Wilder Communities workshops and for more details go to: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/WilderCommunities or check out p9 of our events leaflet (enclosed).

A selection of workshops from our 2025 programme:

An introduction to DIY posters

Tuesday 10 June 2025

Online webinar via Zoom

How to create a wildflower meadow

Wednesday 18 June 2025

Fir Grove, Wreningham

Making room for swifts in your neighbourhood

Tuesday 8 July 2025

St Nicholas Church, North Walsham

Introduction to practical scything

Sunday 13 July 2025

Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse

Hedgehogs, their ecology and how to help these prickly customers

Friday 8 August 2025

Trimingham Village Hall, Trimingham

Five steps to creating a simple management plan for your churchyard

Thursday 11 September 2025

Gissing Community Building, Gissing

Unique glass beads, jewellery and gifts

1 Albert Street, Holt NR25 6HX

07801 225757

www.seahorsestudio.uk seahorsestudio@icloud.com

Find me on Facebook! www.facebook.com/ seahorsestudioholt

Develop your skills and wildlife knowledge with expert-led biodiversity training from the Field Studies Council.

Delve into some interactive online training, with resources, live webinars and activities.

Online courses in 2025:

• Introduction to Mustelids

• Discovering Garden Birds

• Botanical Anatomy

• Fungi Field Skills ...and more!

Visit our website to book www.field-studies-council.org/natural-history-training

With the disappearance of Norfolk’s once abundant meadows, churchyards are now playing an important role as sanctuaries for much of our declining wildlife. Many of Norfolk’s churchyards are ancient plots of land, often untouched by the modern world of fertilisers and chemical pesticides. This makes them wonderful places for native wildflowers, and being relatively undisturbed, fantastic for other wildlife too — from lichens to swifts and bats to butterflies.

With the support of the Diocese of Norwich, NWT runs the Churchyard Conservation Scheme to survey, monitor and advise on the wildlife-friendly upkeep of our county’s churchyards. With over 700 churches in Norfolk this is a massive task, so we are enlisting your help with this summer’s spotter survey. We have identified three species of native wildflower that are good indicators of a possible wildlife-friendly and biodiverse churchyard.

When passing or visiting a churchyard, keep your eyes peeled and please submit your records online by visiting:

norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/SpotterSurvey

Championing churchyard nature

Read more about our work in churchyards on p30.

FLOWERS: May to September

Large long-stalked daisy, with slightly hairy spoon-shaped toothed leaves, the plant is between 20cm to 70cm tall. Its alternative name, moon daisy, is apt; as its big yellow eye seems to glow on a moonlit summer’s night.

FLOWERS: July to September

This downy, perennial member of the carrot family has a tough, slightly ridged stem and an umbel of white flowers. It is highly nutritious for livestock, and in the past was commonly cultivated for fodder.

FLOWERS: July to August

Small, narrow leaves that appear in whorls on its angular stems, with dense clusters of yellow flowers. These full ‘frothy’ flowers smell of honey. Their name derives from a custom of including it in the straw-filled mattresses of women about to give birth.

Butterflies are a symbol of summer, and one particular group are little sapphire jewels that sparkle in the sunshine. There are nine regular ‘blue’ butterflies in the UK (although some are brown in colour in both the male and female). Here are some tips for finding and identifying Norfolk’s top three:

After becoming extinct as a Norfolk breeding butterfly, a re-introduction scheme and careful conservation has seen the return of the silver-studded blue. The butterfly is associated with heathland, with the caterpillars relying on heather and gorse. Although similar to the common blue, it is the smallest of the three. In many places in the UK, it is in serious decline, however at NWT Buxton Heath they occur in impressive numbers.

This butterfly can be found across the countryside where uncut grass and wildflowers grow. It has a habit of flying close to the ground, particularly the female when searching for bird’s-foot trefoil on which to lay her eggs. The male has violet-blue wings, finely trimmed with a black and white margin. The female is dark chocolate brown, and it requires a keen eye to distinguish it from the brown argus butterfly.

The holly blue is the most frequently seen, and is at home in gardens, parks and churchyards. The male and female are both lilac-blue, with the female sporting black wing tips. They also have silver-white underwings speckled with black dots. The holly blue tends to fly higher, skipping among the bushes. The caterpillars feed on ivy buds.

In late summer, bird song gives way to the buzz and hum of insects. Why not find a patch of long grass to lie in, close your eyes, and enjoy the ‘song’ of grasshoppers stridulating.

Take time to smell the cool familiar scent of water mint or the honey-perfumed flowers of meadowsweet. The meadowsweet’s leaves, in contrast to its flowers, have an antiseptic fragrance.

Many people are familiar with our wonderful coastal reserves at Cley and Holme but travel a few miles inland and NWT has another gem sitting within the North Norfolk Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. NWT Ringstead Downs is a ‘Site of Special Scientific Interest’ for good reason, for the reserve is one of the largest remaining areas of unimproved chalk grassland in the county. This wonderful dry valley was cut through by glacial meltwater at the end of the last Ice Age, leaving steep-sided slopes — a rare landscape for Norfolk. As a result, the valley has never been ploughed, so now stands as an

excellent example of this speciesrich habitat. The profusion of wildflowers ensures an abundance of butterflies — 20 species have been recorded here, including the brown argus. Other insects include the oak bush-cricket, speckled bush-cricket (right) and black oil beetle. The common rock-rose is a typical chalk grassland species that grows here, and it can be seen in bloom from June to September; it has a strongly scented sulphuryellow flower. Many other flowers, unusual for Norfolk, are found here, including dwarf thistle, squinancy-wort and wild thyme.

How to get there?

Access is from the permissive bridleway through the Downs,

Hedgehogs are thriving in a housing estate in Norwich, thanks to the passion and dedication of an enterprising twelve-year-old.

Hi, my name is Kitty, and I am a Hedgehog Champion. I raise awareness of how endangered hedgehogs are, to encourage people to become champions for the species.

I live on a new housing estate called The Hampdens and we now have a thriving hedgehog community. Over the last couple of years, we have added hedgehog houses and feeding stations in our garden — as well as pollinators to encourage more insects. Many of my neighbours have done the same — encouraged by me! Last year, we even had baby hedgehogs born on the estate.

For the last two years I have run a ‘raising awareness’ stall in my local park. I also fundraise for the British Hedgehog Preservation Society and our local animal sanctuary,

Hallswood, who take in sick or injured hedgehogs. My regular newsletter keeps people up to date, plus we have a Facebook and Instagram page.

I want to make our whole estate more inviting to insects and hedgehogs in the early part of spring, when they come out of hibernation, so I started a Pollinator Pathway project. I gave neighbours and residents seeds to plant in the tree pits outside their houses. I also ran a community planting day, and we planted wildflowers on a roundabout and other green spaces. There are now many more grasshoppers, bees, butterflies and caterpillars around.

Helping hedgehogs makes me feel really happy and proud. I’m making a difference, even though I’m only 12 years old. Imagine the effect on hedgehogs if everyone opened their gardens to them and gave them a chance.

‘‘

When I see a hedgehog using the Hedgehog Highway that I made in the fence, eating the food I left out or using our green spaces, I feel proud that they can share our garden and estate with us.

Every hedgehog I help means one more chance for them to survive and have babies. Maybe one day they will come off the endangered red list and be part of our everyday world again!

Learn more about Kitty’s work by following ‘Hampdens Hedgehogs’ on social media.

Find out how to help hedgehogs and other wildlife at home norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/Actions

Selecting plants is one of the most exciting parts of gardening, but compost choice can determine a great deal of success in the garden.

When selecting a compost, the most important thing is to look for a peat-free label. Taking peat out of the ground destroys important habitats and releases large amounts of stored carbon into the atmosphere, so gardening peat-free is an easy way to take positive action for wildlife and climate. If you can’t find peat-free stated on the bag, then the chances are the product contains peat. Something marked as organic or environmentally-friendly doesn’t necessarily mean it’s peat-free.

Peat-free mixes contain more microbes, many of which are beneficial for your plants but can change how the compost performs the longer they are left in the bag. To get the best from your compost, we recommend using it in the growing season you bought it or within a year of the manufacture date. If you are using smaller amounts of specialist mixes, such as ericaceous compost for acid-loving plants,

you could share with a friend or local gardening group to save on cost.

Not every peat-free mix will be a perfect fit for every gardener, so try a couple of different types to find one that suits your plants and growing environment. Peat-free compost has come a long way, with a wide range for every need and plant type available. All peat-free mixes are different, so you might also need to adjust watering and feeding a little. As a general rule, peat-free may need to be watered little and often compared to peat.

Getting to know what you need from your compost and which products give healthy, long-lasting plants can unlock a whole new world of gardening success for anyone, even if you don’t have the greenest fingers!

Claire Thorpe is the peatfree campaign manager for the RHS, and is passionate about helping people garden sustainably.

Meadows

A wildflower patch full of native annuals like oxeye daisy won’t need any compost at all, as these plants prefer low nutrient soils, so you can sow directly into bare ground.

Veg

Soil improvers and manures, which contain lots of organic matter, can add nutrients without the need for lots of fertiliser.

Seeds

Seed and cutting compost is specially mixed to suit these young plants, being much finer and containing less slow-release feed than multipurpose compost. The fine texture is especially important for small seeds like foxglove.

Trees and hedges

Peat-free compost is prone to a dry top so check with your finger to see if there is moisture lower down in the container and aim to keep compost just moist, stopping watering before it runs out the bottom.

Specialist plants

Look for products labelled as working for plant groups that need specific soil conditions (e.g. carnivorous sundews or ericaceous cranberries), as multipurpose compost won’t provide the conditions they need to grow well.

As well as being brilliant for wildlife, trees and hedge plants often come bare root (not in a pot), so you can plant in the ground, just adding some mulch. Home compost or leaf mould are easy mulches to make yourself.

As well as in compost, peat can be found in bedding plants and potted house plants. Help us raise awareness of ‘hidden peat’ by becoming a peat inspector: wildlifetrusts.org/ban-sale-peat

Pond plants

Use special aquatic mixes to fill pond basket planters, these are formulated to ensure nutrient release is slower, stopping leaching into the pond which can cause algal growth.

Houseplants

One of the biggest killers of houseplants is overwatering. Mixing houseplant-specific compost with grit or fine bark will help stop root rot by improving drainage.

Nick Acheson Author and NWT Ambassador

Buff-tailed bumblebee covered in pollen

Ecologists and conservationists often talk with confidence about prehistoric vegetation, making reference to the plants which flourished in past landscapes and their relative abundance. These seem astonishing claims, given that no literate humans were around to document the forests and grasslands of the distant past. Abundant evidence of past vegetation can be found, however, if we only look in the right places.

One of the most powerful disciplines helping us understand prehistoric vegetation is palynology, which translates from ancient Greek as the study of particles that are strewn around. In practice, palynologists study pollen grains.

Pollen is produced by most seed plants. Pollen grains are not themselves — as often assumed — the plants’ male gametes or sex cells; rather they are gametophytes which produce male gametes. Pollen grains have hard external cases, formed of a polymer called sporopollenin, and for two reasons this makes them invaluable to palynologists. The first is that sporopollenin is extremely stable, persisting in sediments for thousands of years. The second is that the external case of each species’ pollen has a unique shape and pattern, giving palynologists the opportunity to profile the species composition and relative abundance of long-gone forests.

But where is ancient pollen to be found?

One of the best stores of ancient pollen is the sediment on the bottom

‘‘One of the best stores of ancient pollen is the sediment on the bottom of wetlands.

of wetlands. As readers of Tern, you’ll be aware of our work in the Brecks to restore pingos around Thompson Common. Pingos are priceless, both because of the many threatened species they support and because, having existed since the retreat of the Ice Age, they can harbour stores of pollen documenting thousands of years of Norfolk vegetation.

Though palynologists love pollen for the stories it tells of landscapes past, many of us modern humans suffer in summer from hay fever and other pollen-related allergies. While pollen designed to be carried by insects and other animals is typically heavy and sticky, and therefore unlikely to be inhaled in large quantities, the pollen of grasses and many trees has evolved to be blown on the wind. Only a minuscule fraction of windborne pollen ever reaches a receptive female cell. The rest is cast across the world, where some is inhaled by humans, including those unfortunate humans (including me) who suffer from pollen-triggered allergies.

Hay fever notwithstanding, pollen — whether windborne or carried by animals between flowers — is a critical adaptation in the story of life on Earth. It has enabled plants everywhere to reproduce sexually, to maintain genetic diversity, and to dominate virtually every terrestrial and coastal environment.

And I suppose that’s something to bear in mind as you reach for the antihistamine this summer...

There are many ways businesses can support our work, from joining our Investors in Wildlife corporate membership scheme, attending an employee volunteering day or donating funds through an affinity scheme. Businesses are increasingly looking to show their commitment to championing Norfolk’s wonderful wildlife and one of the most impactful ways to do this is through a charity of the year partnership with us.

We are delighted to announce that Westover Large Animal Vets have chosen Norfolk Wildlife Trust as their charity of the year for 2025. As part of this partnership, they will be fundraising for us in multiple ways throughout the year, such as raffles at their client evenings.

They will also be holding an open day later in the year where NWT can enthuse guests about the vital work we do.

Jazmine Notley, Westover’s Receptionist, says: ‘working alongside animals every day, the vets and staff at Westover understand the importance of nature, and of healthy, functioning ecosystems. For this reason, we wanted to support the good work of Norfolk Wildlife Trust, and hope that our support can go some way to boosting their important projects and conservation initiatives. We’re looking forward to working together over the coming year!’

We wanted to say a huge thank you to Westover Large Animal Vets for their support and are looking forward to collaborating throughout 2025.

If your business is looking to make a real difference to the protection and restoration of Norfolk’s natural wonders, then why not nominate NWT as your charity of the year? If you would like to find out more, please contact our Corporate Partnerships team at wilderbusiness@norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk.

Our trustee Bailey Tait took on an epic 84 miles of the Norfolk Coastal Path to raise money for Norfolk Wildlife Trust.

‘Every day brought different terrain and different iconic Norfolk species. The grey seals basking on the beach at Horsey Gap and the sound of marsh harriers overhead reminded us exactly what we were doing it for.

‘We tried to keep note of everything we saw, but the Norfolk coast is such a wild and rich landscape that we lost count very quickly. Some of the top performers were lizards, larks, water voles and green sandpipers.

‘The hardest part was definitely camping. On the third morning we woke up to ice on our backpacks. And having to carry everything you need to camp on your backs for 84 miles made the walking infinitely harder.

‘Hobbling into Hunstanton on the final day was euphoric, not just because we’d done it but also because we had raised over £1,500 for Norfolk Wildlife Trust!

‘Thank you to everyone who donated and for anyone considering their own fundraiser — do it, you won’t regret it.’

Fancy fundraising for us?

Find our more: norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/ Fundraise

Bailey Tait

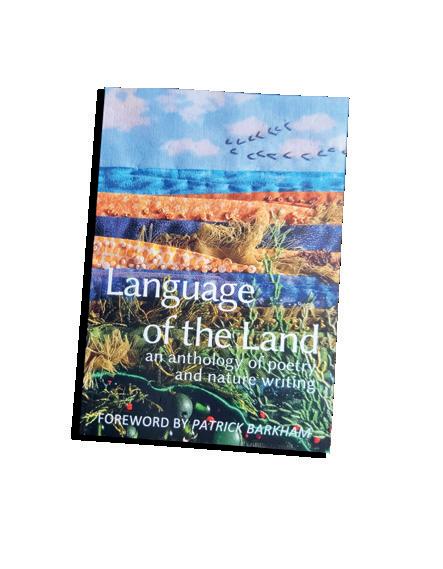

Nick Acheson reviews the new anthology by the Cley-based writers’ group with all proceeds going to NWT.

In a speech to the Norfolk Biodiversity Partnership in 2009, visionary writer Jay Griffiths extolled ‘that lovely heart-slipping moment when you suddenly realise that you are with a knower of the land, who keeps like treasure their stanza of the song.’

Reading Language of the Land — a new anthology by the Cley-based writers’ group led by Jonathan Ward — I am often reminded of Jay’s words. For its contributors — like the wavewashed pebbles of Cley beach — are, in their diversity, united by Cley’s cycles of change. Through their shared, repeated walks and words, they have been rendered knowers.

Inevitably, in an endeavour built on common creative practice, some themes recur in the words of multiple writers. One such is the power nature exerts on us, for good. ‘We came to be unboundaried,’ writes Sue Burge, ‘unmoored; to be sculpted by wind.’ Unquestionably this is the reason so

Close and respectful observation of wild beings is a recurrent theme too. ‘Is it improper,’ asks Tina Green, ‘to stare at beautiful / Creatures through a screen?’ But stare we must, as the dignity of our wild fellows demands it, be they Peter Lloyd’s banded agrion (‘My second life this / Short, bright’), or Chris Tassell’s kestrel (‘which joined us to show how to master the wind’), or even Lesley Mason’s oak, whom she asks to tell her ‘of the games you played in your acorn days, / your sapling courtship hidden in the woods.’

Impermanence is another of the themes woven through the work of several contributors. Barb Shannon wistfully observes, ‘all I hold dear... beautiful even / is merely a trick / of light.’ And Maddie McMahon urges us to look with compassion and attention on an autumn leaf, ‘before she is gone.’

In a book about a place so intimately connected with Norfolk Wildlife Trust, whose profits will generously be donated to support our work, the theme of impermanence inherently translates into our human ravages