Issue Five:

LET THE BEGIN CIRCUS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Executive Board of Counterculture Magazine would like to extend an immense amount of gratitude to everyone who participated in this project and helped us create Issue Five. It is because of your support that we were able to keep the momentum we needed to make it into the magazine it is today.

We would first like to extend a huge thank you to our faculty advisor, Dr. Thad Williamson at the Jepson School of Leadership. Dr. Williamson was one of the first supporters of this project and helped us to conceive many of the ideas that are foundational to the magazine. His support during our time as both an affiliated and unaffiliated organization is unprecedented, and we are forever grateful.

Next, we would also like to thank our team of writers, who have persisted through this project despite academic and personal stress. Thank you for telling your stories and providing your insights, as well as devoting much of your time to the creation of this project. Without your hard work, this magazine would not be able to exist. We would also like to extend a thank you to our creative design and social media team for developing the concept for this issue and making it come to life through visual narratives. To our cover models, thank you for your participation in this project and for creating the beautiful photos on the cover and that are incorporated throughout the magazine.

Lastly, we would like to thank the larger University of Richmond community for their consistent support over the last four issues of the magazine. From sharing social media posts from the Counterculture Instagram account to telling us how excited you were to see this project come to fruition, your endless support and enthusiasm propelled us to make this issue come alive. We are elated to have you as our mentors, peers, and friends.

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR I

It’s the end of an era.

At least for me, anyways. I’ve said it before, and I will say it time and time again: when I first came to Richmond in the fall of 2021 and started this magazine, I would have never imagined it where it is today. With a budget, for starters. With a committed, engaged, wonderful team of writers and creatives. With a deeply supportive student body that rallies behind every issue. We’re nearly three years out, and Counterculture Magazine continues to surprise me at every turn.

Here’s another thing that would surprise freshman year me: Issue Five being my last issue as editor in chief.

When I established Counterculture, I assumed that I’d be in this position until Issue Seven, assuming that I continued to do a good job and be re-elected by my peers. While I studied abroad this past fall in Cape Town, South Africa, it became evident that this magazine needed to move beyond, well, me. I realized that in order for the magazine to continue to grow and prosper, there needed to be a change. I decided that I would remain in the position for one more semester to ensure that things would be handed off smoothly, and in the end, get to watch the magazine I love so much grow and change from afar.

In many ways Counterculture and I have grown together, throughout these years. When I started this magazine, I came onto this campus on fire, determined to use my voice in an impactful way to inspire change.

As I approach my senior year (!) I have become a lot more reflective about the person who I’ve become during my college years. I truly believe that Counterculture has been instrumental in my development as an individual and activist. Beginning this magazine was the boldest thing I had ever done in my eighteen years of existence. I knew what was at risk the potential embarrassment of creating a complete flop of a publication, the fear that no one would participate. But I trusted in myself and this community, and I am so happy I did. I am so, so happy that I did.

This semester I’ve been thrilled to work on Counterculture with another editor in chief, and it is thanks to her that my hair was not on fire as we attempted to pull together this publication. Sydney Dwyer has been one of my closest friends throughout my time at Richmond, and I could not think of a better person to entrust this magazine with as she takes over as the sole editor in chief in the fall. She’s been here since the beginning— she was one of the first signatures to register Counterculture as an organization! and embodies the values that this magazine is grounded in. I can assure you that this magazine is in extremely capable and dedicated hands.

Issue Five is the most visually unique magazine that we’ve produced, and, along with Issue One, it is also the one that I am the most proud of. I am so happy to leave Counterculture as a part of my legacy at the University of Richmond, and look forward to coming back in the fall for Issue Six, this time as a writer. Thank you— to the writers, the creatives, my family, and my friends for the best three years as editor in chief. Happy reading.

With love, Christian Herald Co Editor-in-Chief

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR II

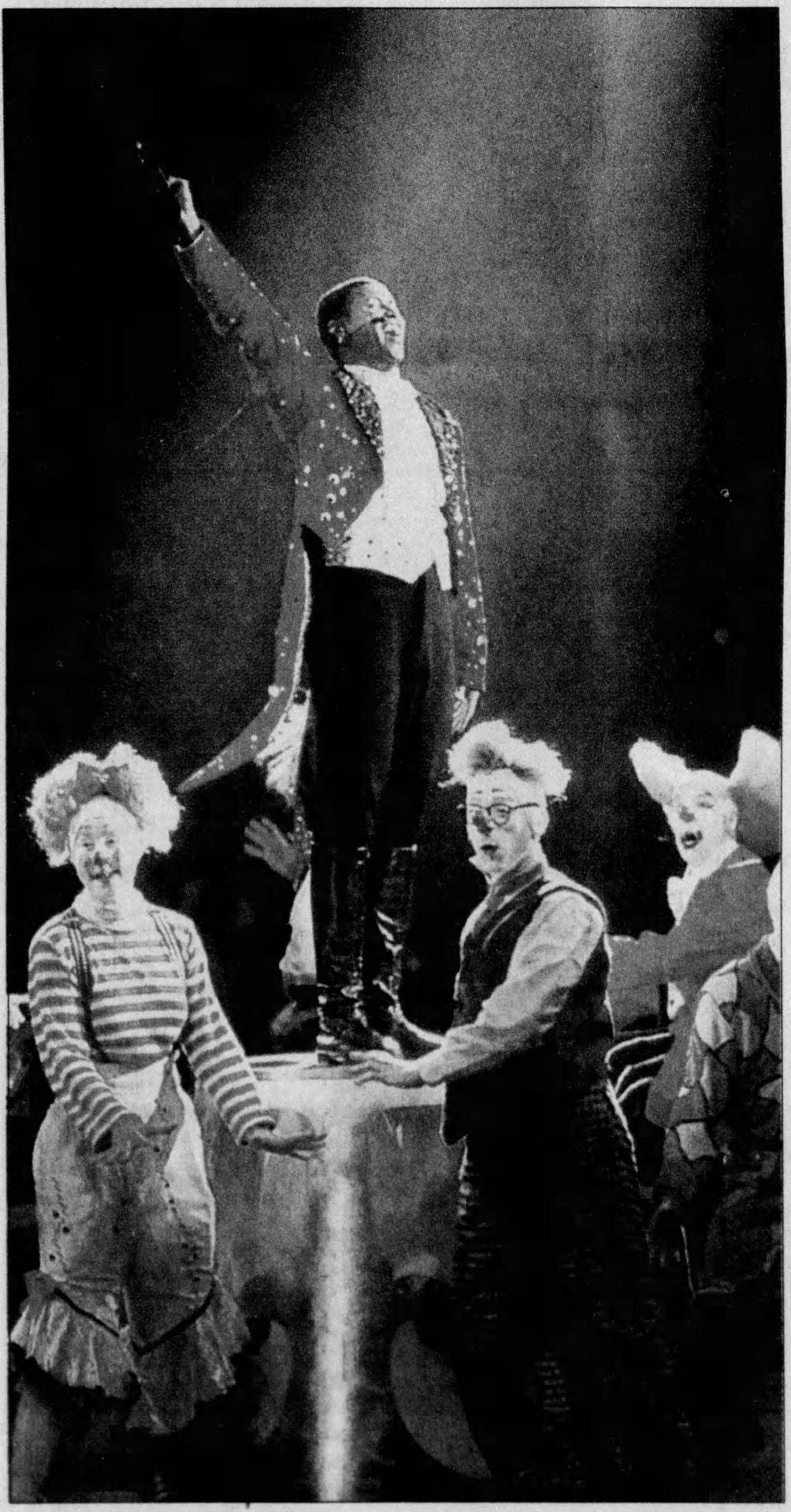

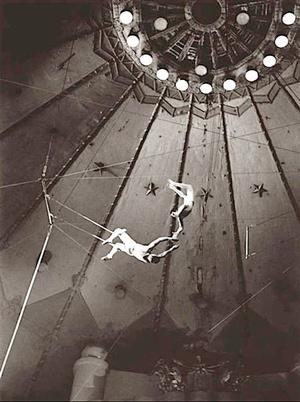

What does it mean to be part of a spectacle? According to Merriam Webster Dictionary, a spectacle is defined as something exhibited to view as unusual, notable, or entertaining, especially in an eye-catching or dramatic public display. Upon hearing the word, many people immediately think of circuses, plays, or other extravagant events that lean into the ridiculous in an effort to tell unique stories that stun the audience. As a result, the idea of a spectacle may seem far fetched, a little bit removed from the reality of our daily lives.

But people don’t always need stages or intricate sets in order to conduct or carry out a performance. Society assigns many roles to the various groups existing within a given place. There are countless unspoken rules and behavioral codes one must follow when interacting with others. Furthermore, these social norms are conditioned by other factors such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation, nationality, and age, to name a few. Don’t we all lean into the idea of performance as we go about our daily lives?

For marginalized groups, these stereotypes, often embedded in problematic ideologies, tell them who they can and can’t be, or what types of resources they “can'' access. For example, women are conditioned to be non-confrontational, to be polite, and accommodating. Certain individuals regularly invalidate the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community, by using phrases such as “it’s just a phase,” or “you chose to be that way.” Black men are often perceived to be threatening while Black women are thought of as being hypersexual. Across every marginalized social group, people must navigate their identities, struggling to live authentically amidst these unwritten categories.

Thus, we decided to pick this theme precisely because it grapples with what it means to live genuinely in a society that tries to dictate who people become and how they experience life. To depict this idea, we decided to develop the idea of a circus, as it tends to represent those who live on the margins of society. We wanted to create something eye-catching, with striking poses, dramatic makeup, and intense body language. I hope you all enjoy reading all of the articles and taking in all of the art!

As one of the original writers of Counterculture, the organization means a lot to me. It presents an important space on campus where people can discuss important issues in a way that highlights their passions. It’s been fun to witness my growth as a writer and become even more comfortable expressing my own voice. I want to take the time to thank everyone who has helped me along this journey, especially Christian, for teaching me what it means to be editor and chief of this magazine. I’ve learned so much this semester, and can’t wait to do it all again next fall!

Happy reading,

Sydney Dwyer Co Editor in ChiefTAYLOR SWIFT’S SILENCE AND THE PROLIFERATION OF PERFORMATIVE WHITE FEMINISM: A STUDY OF THE VIRTUAL “SWIFTIE” FAN BASE

Scrolling through the depths of TikTok, each swipe of my thumb yields another 20something-year-old baking cinnamon rolls in their studio apartment, a compilation of the best Oscar speeches this year, or a puppy toddling around the backyard for the first time. However, between each of these videos, I find myself guiltily captivated by the same thing that has plagued my mind since 2020: the inhuman spectacle of Taylor Swift. Singing along to the 60-second slice from her 200+ song discography that I’ve committed entirely to memory, I watch as other teenage girls spin around their rooms or sob to the lyrics on their beds, seeing my own connection to her music reflected in their performance before the camera. As the paralysis of the doom scroll sets in, however, I begin to realize that something isn’t right. As each lip-syncing girl flits around my screen, I notice that each one looks exactly the same, and nothing like me. Stereotypically pretty, white teenage girls have flooded my social media, laying claim to the relatability of Taylor Swift’s discography

TikTok is just one of the many social media platforms that provide a skewed mirror of the shades of Taylor Swift’s fanbase. Rising to fame in the 2000s as a country artist, Swift occupied a predominately white genre with a fanbase that mirrored this disproportionate racial makeup. Consequently, even throughout her evolution into Pop music, the makeup of the “Swifties” has always been disproportionately Caucasian. A 2023 survey found that nearly 75% of Taylor Swift’s American fan base identifies as white, almost 50% of which are suburban millennials. With global touring and periodic album releases spanning 18 years and nearly 600 live performances, Swift walks the line between skillfully adapting to the desires of her consumers and dictating the future of pop herself. With a life lived largely in the spotlight, her meticulously controlled identity has engendered a fanbase of white women who have paradoxically grown up alongside her, calibrating their vulnerability to the candidness with which Taylor expresses herself; her ever-growing discography providing a vocabulary of viable emotions for these “Swifties” as they navigate the world.

Not only has her influence enchanted millions of Americans, but it’s also captured the attention of the world. Swift was named the top streaming artist of 2023 on both Apple Music and Spotify. She also holds 13 number 1 album slots on Billboard and is the first artist to ever claim the top ten places on the Hot 100 in a single week. The Eras tour solidified her global impact, creating a 2.3 magnitude earthquake during the Seattle leg of The Eras tour and bringing in more than 5 billion dollars to the U.S. economy between 2022 and 2023. Within the social media space, Taylor holds 539 million followers across all platforms, creating a community of TikTok “Swifties” with an average of 380 million views per day. Named Time Magazine’s 2023 Person of the Year, with a word powerful enough to supposedly change the price of eggs in America, Taylor Swift has the largest non-political platform in the world right now. The question is, what is she doing with that immense influence?

For some, she’s done a lot. Historically coached by managers and record labels to confine her identity to the content featured in her albums, Swift’s teenage years in the spotlight were lived as a largely unproblematic, idealized presentation of womanhood. Her media presence was largely confined to tabloid conversations about boys and relationships, with a personality just unconventional enough to paint her as the alluring girl next door; tall, thin, blond, and ‘not like other girls.’ You can imagine the shock of the world then, when in 2017, she met a defamation claim from radio host David Mueller with a sexual assault countersuit against him for a single dollar. A critical predecessor of the #MeToo Movement, this was the first time Taylor spoke out publicly about any kind of hot-button topic, let alone one with as much vulnerability as her own victimization yielded. She fought the lawsuit with bravery and confidence, winning on all counts, empowering millions of women to fearlessly share their own stories of misconduct and assault.

Her subsequent steps into the public sphere have been infrequent, but no less influential. In October of 2018, despite the pleas of her publicity team, she released a social media statement endorsing the Democratic senatorial and congressional candidates in Nashville, Tennessee. After declaring that she could not vote for someone unwilling to “fight for dignity for ALL Americans,” Swift has since then encouraged her followers to vote for the candidate best representing their values. In June of 2019, Taylor released the famously inclusionary “You Need to Calm Down” music video, making a point to feature people of all shapes, shades, sizes, and sexual orientations. Shouting out the work of GLAAD in her lyrics, Swift inspired a flood of 13-dollar fan donations to the non-profit LGBTQ+ rights organization. Her forays into social justice allyship have been few, but when executed, impactful.

Perhaps her most provocative and well-received social commentary is off her 7th album Lover, with her 2019 hit song, The Man. Swift shares her exasperation at constantly being undercut and reduced to her appearance or newest love interest, marveling at the hypocrisy of misogyny and sexism when under the scrutiny of the public eye. As she writes, "if she were a man, then “[she’d] be the man.” Rebuking the double standard that broader society holds women to, Swift wrote that if she were male, no one would “question how much of [her success she] deserved,” her wealth making her a “baller” rather than the undeserving “bitch” the media made her out to be. Her lyrics hit home for millions of women around the globe, a recognition of their endurance and prowess in the face of discrimination and marginalization. There is no doubt that Taylor Swift has used her platform to amplify good causes. But does her work qualify as true social activism?

Before making any comments about Taylor Swift's activism, it is critical to distinguish between social and performative activism. Activism is characterized as “the use of vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change,” where the ‘activist’ participates in an organized series of actions aimed towards a particular social goal. In this sense, activism requires sustained public efforts to engender change, a commitment to dedicating one’s time to spreading awareness and repeatedly attempting to make visible changes in our society. Most critically however, activism is predicated on the selflessness of the activist, as the efforts taken to make a social impact are intended to further the wellbeing of a marginalized group, rather than boosting public perception of oneself. In contrast, performative activism is defined as “activism done to increase one’s social capital rather than because of one’s devotion to a cause,” and is intended to inform the public about the individual’s social values, rather than an active effort to create social change. Performative activism consciously crafts one’s public identity, and often consists of sparse efforts to further social change, accompanied by the individual “continuing to make the same harmful choices and actions.” While discerning anyone’s intentions is incredibly difficult and subjective, the activist’s dedication to both embodying and spreading the values they fight for is a critical aspect of social justice efforts in the age of perceptionfocused digital media.

Upon closer inspection of Taylor Swift’s forays into social activism, it becomes increasingly clear that as deeply as she believes in the causes she champions, her actions have had less of an impact on society as a whole, and much greater influence upon the public’s perception of her image. It is critical to note that Swift has never claimed herself to be an activist, nor has she set forth her music to represent the struggles of an entire community. However, Taylor Swift is more than just a talented singer-songwriter. She is an individual whose personality, image, and most vulnerable feelings have become currency within a capitalist media industry where she is, in effect, a capitalist mechanism.

From publicity stunt relationships, to strategic on-trend outfits, to the very words that come out of her mouth, Taylor’s public actions are designed to enhance her profit-making capabilities, rather than hinder them. With her immense societal influence, it is evident that her actions can have rippling impacts, but in selectively deciding which social justice issues to speak about, Swift sends the message to her millions of fans, that a certain set of issues are worth taking a risk to support, while others are not. Further, Swift’s criticism of inequality and injustice align with the inherent bias of white feminism, a type of feminist ideology driven by both conscious or unconscious bias which exclusively centers on “white middle-class women and..the issues that primarily affect them.” Another glance at the lyrics of The Man reveals a different story. Swift argues that a simple gender switch would lead to a life of privilege and power. But for female-presenting people of color, a gender switch would be highly unlikely to ward such an untouchable position of influence within society. Further, queer male-presenting people would be far from untouchable, historically experiencing pervasive discrimination. In an effort to share her own pain, she takes an excessively broad-stroked stance, seeming to forget the additional complexities faced by the many individuals residing in the intersection of multiple marginalized identities. Swift’s song, while impactful for her fanbase of white suburban millennials, rings slightly tone-deaf to the vast majority of the marginalized communities she claims to support, regressing the progress made to carve space for all marginalized communities within mainstream media.

But Swift’s sidelining of marginalized perspectives is only half of the issue. With her immensely devoted following comes an immensely impressionable fanbase, who find themselves seen and represented in songs like The Man. And why wouldn't millions of young white women doubt the reality of Swift's lyrics?

They look, act, feel, and experience the world the same way Taylor Swift does. So, if she laments that she would be uncriticized and impenetrably strong if she were a man, who has the right to stop millions of women from feeling seen and heard in Swift’s struggles? No one does, and I do not attempt to argue that it is so. However, I urge you to think about the 100 million non white women who are also Swifties, and how they feel whenever they go on Tik Tok and fail to see any type of representation. Where they once found a place of affinity and reassurance in their feelings of Taylor Swift diminish and diminish, until those people realize that maybe her words are not meant for them.

Further, Swift’s recent silence during the 2023 media storm surrounding her speculated partner Matty Healy reinforces her lack of commitment to take action against the discrimination she vocally condemns. Shortly after the release of Swift’s 10th studio album, Midnights, she was photographed publicly with the lead singer of “The 1975,” Matty Healy, escalating into a speculated publicity relationship, as the two were photographed holding hands and going on dates for several months before ‘breaking up’ almost as covertly as they had gotten together. However, during their brief ‘relationship,’ news began to filter through media publications surrounding Matty Healy’s numerous discriminatory remarks and Nazi salutes during past tours and concerts, facing serious accusations of racism and discrimination actions under the spotlight of his enlarged platform. Appearing on a podcast in January of 2023, Healy publicly mocked the ethnicity of the newly popular rapper Ice Spice, calling her an “‘Inuit spice girl’ and ‘chubby Chinese Lady’” when referring to her Nigerian and Dominican heritage. In the resurfacing of Healy’s overt racism, Swift made no attempt to comment, not only continuing to be publicly associated with Healy despite the backlash of the media, but even offering Ice Spice a collaborating on a song off her newest album and bringing her out as a guest star on three Eras Tour concerts, a publicity stunt band-aid veiling the ignorance that she supposedly stood against. Remaining entirely silent as a woman of color received the discrimination and hatred she denounced in her own discography, Swift made herself complicit in this hatred, continuing to frequently associate with Matty Healy while the public constantly berated him to apologize.

Swift’s actions have even wider ramifications however, as her fan base reiterates and reinforces the positive aspects of Swift's public identity, while simultaneously omitting her missteps. Swift’s silence demonstrates to her millions of fans that it is permissible to overlook the harm done to women of color, so long as it does not impact yourself. Her role as a complicit bystander represents the rampant white feminism going unchecked in our society and her continued idolization demonstrates the danger of her predominantly white fanbase, as her sheath of performative activism absolves her from the responsibility to speak out for equality and justice when it truly matters. In evading accountability through silence, she models to her impressionable fans that they are not responsible to advocate for others.

Additionally, in attempting to circumvent a recognition of the harm done to her fanbase by both her and Healy’s actions, she teaches people from marginalized communities to accept the discrimination, because they could one day be rewarded by the paternalistic spotlight of white privilege and power.

Swift’s silence may have lost me as a follower, but she is by no means feeling consequences of her performative activism and role as a complicit bystander. Due to the same social media algorithms that pushed white Swifties onto my “FYP,” social media platforms will continue uplifting the people who celebrate Swift’s positive attributes, while sidelining voices bringing awareness to ways in which he has harmed the communities she continues to performatively support. Yes, Swift has absolutely done things that have had genuine positive impacts for marginalized and silenced communities in our society. But, with the proliferation of social media, Taylor Swift has come to exemplify the very performative white feminism that marginalized communities have fought so hard to combat. Swift chooses to remain silent at the times when her voice would have the most impact, modeling the ignorant freedom inherent to performative white feminism. Coupled with her widespread idolization in American pop culture, her actions instill this lack of circumspection in yet another generation of potential changemakers.

INCLUSIVE, “WOKE,”OR INSUFFICIENT?

THE DIALOGUE SURROUNDING DIVERSITY, EQUITY, & INCLUSION (DEI) AT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES

In 2023, a survey of U.S. college students revealed that 55% of students would think about transferring schools if their college banned DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) initiatives. DEI programs at universities have recently been under fire by conservative lawmakers, with 49 total bills aiming to prohibit DEI employment and funding already introduced in state legislatures, 7 of which were signed into law. There seem to be differing perspectives on the merit of DEI programs, as evidenced by the percentage of students who view DEI as a necessity at universities and the number of anti-DEI laws circulating in state governments. In addition, some individuals do not support eliminating DEI, but they believe that current DEI initiatives could be strengthened. In order to unpack all of these opinions, it is necessary to delve into what is included in DEI programs at these institutions of higher education. At the very heart of DEI are programs and resources that provide support for underrepresented students, and also funding for DEI research and hiring educators of marginalized groups. DEI also includes diversity statements by faculty and staff, diversity training, and more inclusive admissions and hiring processes.

THE PRO-DEI STANCE: COUNTERING HISTORICAL DISCRIMINATION AT UNIVERSITIES

This brings us to the first perspective on the DEI initiative: those who wholeheartedly believe in the power of inclusion at universities regardless of background. Proponents of DEI emphasize the undeniable truth that colleges have historically discriminated against minorities and lacked diversity among their ranks. They make it their mission to counter discrimination on campuses and provide culturally sensitive resources for underrepresented students. DEI does not only support racial minorities, but also uplifts those with disabilities, immigrants, the LGBTQ+ community, and veterans.

Many students of color have voiced their opinions about potential DEI bans at public universities, making it clear that these bans feel like an insult to their existence. One student at Ohio State University stated that the closing of DEI offices was akin to “a slap in the face.” In particular, Black students, who make up 8% of the school’s population, value the benefits of the Frank W. Hale Jr. Black Cultural Center, which is the central headquarters of DEI on campus. Black students can connect with staff who share their racial identity, and the staff can help them through challenges that are unique to the Black experience in the U.S. The same student mentioned above labeled this center as “a safe haven.” To students of marginalized groups, these DEI-affiliated centers are places where they can receive assistance tailored to their identities on a campus where others do not share their backgrounds. Even just connecting with people like themselves can bring a sense of community and belonging when they feel isolated among their peers.

Some statistics illustrate the significance of DEI for students of marginalized groups. 60% of Hispanic and Latinx students and 59% of Black students would think about transferring if their school outlawed DEI compared to 52% of white students. Additionally, 69% of LGBTQ+ students stated that a DEI ban at a college would have affected their decision to enroll, while only 56% of cisgender and heterosexual students said the same. It is evident that students of underrepresented groups have a stake in the concept of DEI. After all, their college experiences would be largely impacted if lawmakers suddenly pulled the plug on DEI at public universities. According to proponents, DEI serves to make these students feel seen and provides any services that would make their transition to higher education easier.

In the wake of anti-DEI bans, public universities impacted by these decisions are forced to work around the law with loopholes. For example, Texas A&M University created compliance guidelines and frequently asked questions so that faculty can still aid students who seek help without directly going against the law. They are still adamant in their mission for inclusion by “support[ing] diversity in a general way” but not “promot[ing] preferential treatment of any particular group and are open to everyone.” Furthermore, Colorado College has even formed a new program called the Healing and Affirming Villa and Empowerment Network (HAVEN), which aims to support transfer students from states with anti-DEI laws. Even amidst the growing number of state laws restricting DEI programs, some colleges are fighting back by providing support to students in any way possible.

ANTI-DEI LEGISLATION: THE DIVISIVENESS AND “WOKENESS” OF DEI

At the opposite end of the spectrum, many conservative lawmakers view DEI as an inherently divisive program, something that supposedly “discriminate[s] against students based on their race, ethnicity, or gender.” While supporters of DEI believe that these programs are intended to counter discrimination based on these identities, those against DEI think the exact opposite. Perhaps they dislike the attention being given to students with marginalized identities after so many years of remaining unacknowledged. Or perhaps they believe these services and resources are discriminatory in nature because they are not offered to white or straight students. Regardless, these individuals believe that DEI divides students instead of uniting them.

Other arguments of critics include DEI programs being a waste of taxpayer money and pushing “woke” ideologies on students and faculty. The enforcement of inclusion seemingly signals to these individuals that they are being forced to align with an ideology that they do not agree with. They claim to work for the interests of students regardless of “race, ethnicity, or gender” while also advocating for the removal of DEI programs that uplift students of underrepresented backgrounds. It is not just lawmakers who are railing against DEI. One English professor who used to work at Penn State Abington claims that the DEI initiatives at this university created a hostile work environment. He bemoans the use of diversity statements and likens this to “bend[ing] the knee” to DEI. He also concurs that DEI “has always been about toeing an ideological line,” and he insists that its purpose was never to create meaningful change. For some individuals, DEI is just another inconvenient rule that university staff are expected to follow.

DEI PROGRAMS ARE DOING NOT ENOUGH TO SUPPORT UNDERREPRESENTED STUDENTS

There are even those who do not support anti-DEI legislation, but instead believe that DEI initiatives do not completely fulfill their promises of supporting underrepresented students. Tyler A. Harper, who is an environmental studies assistant professor at Bates College, claims that “DEI offices are focused on the least impactful inequalities on campus.” Harper did not hold back when he suggested that universities attempt to “appear progressive when they are in fact engines of inequality through student debt placed on Black and brown students who they purport to be lifting up.” From his perspective, it seems that colleges and universities are showing their hypocritical sides by claiming to help students of marginalized groups while also exploiting and profiting off of them through financial oppression. Perhaps they are even putting on the whole DEI front to pull people’s attention away from the real problems, like “slap[ping] a smiley face on all that,” suggests Harper. This stance begs the question of whether universities are refusing to address the structural inequities at their institutions.

Some people believe this accusation to be true because of the methods of gaslighting that colleges use to create the illusion of progress. According to an article from Inside Higher Ed, universities have not lived up to their promises of DEI, and they have even refused to implement structural changes that could actually make progress. They have mastered the use of polished DEI rhetoric, but simultaneously do not act to dismantle systemic inequalities.

One of these methods is called “the slowdown,” which occurs when university boards claim that the proposed initiatives cannot yet be implemented. This method effectively puts all plans on hold while they review policies, delaying the necessary structural changes for an indefinite amount of time. Another method is called “the shutdown,” which signals to those suggesting action that they must cease their work, halting the conversation in its tracks.

These gaslighting tendencies allow the university to pretend all is well on the surface while shutting down anyone who speaks against their DEI policies, even at the expense of genuine progress. It is evident that there are people on the fringe regarding the stances of DEI in higher education, as some believe that there is much work to be done to improve the existing DEI initiative. After all, if one were to ask underrepresented students at any predominantly-white university about DEI at their school, they would most likely be met with a mixture of critique and praise.

THE VARIOUS STANCES ON DEI: THE CONFLICT AMIDST ANTI-DEI LEGISLATION

As anti-DEI legislation continues to multiply in state legislatures, the dialogue around Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion will remain chaotic and multifaceted. There will always be outright proponents and critics, but there will also be those who take on a more nuanced position such as the one discussed previously. Universities that embrace DEI will continue promoting inclusivity through legal loopholes even if their state laws discourage it. AntiDEI politicians will keep introducing legislation in their states despite pushback. Those on the fringe will continue advocating for more structural solutions that universities will most likely reject. Only time will tell us how this debate on DEI initiatives at public universities will be settled.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MEDIA LITERACY

Chances are you’ve heard the string of phrases, “declining media literacy” or “media literacy is dead” on a social media post. It sounds strange, scary, maybe even silly. You may not have any clue of what it could mean.. And is it even really happening? To understand if and how it is declining or if it has died, we must first understand what media literacy is.

“Media” (shortened from “medium”) refers to anything that conveys information. It can be made for numerous reasons including for entertainment or news. Often, it is used to show public opinion. In this modern age, the type that comes to mind is social media, a newer form of mass media. Other recognizable types include newspapers, television, radio, and magazines, such as this one. Books and movies can also apply, as a way of sharing ideas and commentary through their fictional worlds. “Literacy” refers to the ability to read, write, and/or interpret information through language. Whether you are constantly aware of it or not, you use literacy in almost everything you do, especially when it comes to consuming media.

Media literacy is the ability to analyze and evaluate information that you see. Most simply, by having media literacy, you will be less likely to fall for scams or false news. Besides those things, media illiteracy can pose bigger issues with misinformation about social and political problems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation and conspiracy theories spread about its origin. Such theories included that the virus was made in a laboratory as a biological weapon from China, or that the virus escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan from scientists working on bats with a more ancestral virus than COVID-19 itself. Dangerous “miracle cures” began to appear overnight. These conspiracy theories lead to a surge in discrimination and violence towards AAPI communities in the United States.

Another example would be the recent misinformation involving election fraud in the United States. As we’ve established, mass media is a huge proponent of how information spreads. Information about elections, candidates, and voting is no different, and in this day and age, most get this information from social media. During the 2020 election, there was a large outpour of misinformation and rumors about “mail-in voter fraud”, most of it coming from platforms like Facebook and Twitter or online news and media outlets. This false rhetoric not only shows cracks in the media literacy of the American public, but it also has the potential to erode the trust of Americans in their country.

From both of these instances with real social and political ramifications, the importance of media literacy is clear. Media Literacy Now, a nonprofit group, and The Reboot Foundation, a research organization, funded a study to see the state of media literacy in the US among adults. The survey was conducted from May 2 through June 9, 2022. The 541 participants reported ages ranging from 19 to 81. All of the participants were located in the United States.

One significant result as it pertains to this topic is that media literacy education alleviated the belief in conspiracy theories and misinformation. “Participants who reported having studied critical thinking activities and media literacy while in school were 26 percent less likely to believe a conspiracy. However, only 42 percent of respondents reported learning how to analyze science news stories in high school, and only 38 percent reported learning how to analyze media messaging in general.”

Another study by a nonprofit called Digital Inquiry Group aimed to gather information on high school students’ ability to “evaluate digital sources” i.e spot misinformation. It was conducted from June 2018 to May 2019 and administered to 3,446 students. The students were given six tasks, all attempting to tap into the students’ ability to analyze online sources and ads. Basically, they were being tested on their media literacy skills. Ninety percent of the students received no credit on four of six tasks. It is clear that from both studies that media literacy, especially digital media literacy, is not where it should be.

It is not so simple to say that media literacy is declining, as those of us exposed to the Internet grow more with each passing day. In the modern digital age, it may not be so much that it is declining, but that it never got the start it deserved. As this is, there has been an increased push to teach media literacy in schools. hhh

In The Reboot Foundation and Media Literacy Now study, 84 percent said they supported requiring media literacy education in schools. 82 percent thought critical thinking skills were lacking in the general public, and 90 percent supported required critical thinking instruction at the K-12 level. Teaching media literacy would not only help to protect children and adults on the Internet, but the skills learned could also help in everyday life. It encourages critical thinking, teaches to discern bias from fact, and allows people to reach conclusions using logic when applicable.

In the United States, California’s state legislature has passed a law to encourage media literacy in schools. However, there has been no legislation on the national level. In Sweden, Canada, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan, and Australia there are “task forces” associated with the topics of media literacy and stopping the spread of misinformation, especially when it comes to elections. In China, there are strict laws pertaining to who is spreading information on “economic and social issues” in general.

Media shapes society, and society shapes people. Media literacy can make all the difference. It can turn naive shoppers into “watchful buyers”, ignorant pursuers into “skeptical observers”, and ignorant people into “well informed citizens”. It is clear that education is the key to spreading this information. Perhaps in the future, the U.S Congress will follow in the footsteps of California’s state’s law, and establish legislation to fund media literacy in schools. In today’s world, it’s crucial, with endless information at the tap or swipe of a screen.

CAPITALISM IN EDUCATION: WHY IS UOFR MORE CONCERNED WITH AESTHETICS THAN ITS STUDENTS?

“Number one most beautiful campus in the country.” The University of Richmond boasts this recognition as if it is one of the most highly revered awards in history. Countless banners with the phrase hang from campus buildings and, sporadically, from banners attached to “spider blue” street lamps. The aesthetic UofR markets to alumni, prospective students, and the Richmond community, however, is drastically different from the UofR that current students experience on a day-to-day basis. While the sole fault for this disconnect cannot be placed entirely on the university itself, especially considering how entrenched capitalism is in every sector of our society, the university has undoubtedly continued to perpetuate this disconnect by prioritizing its image as a brand over its students time and time again.

THE LARGER REALITY

Like most institutions of higher education, especially those that are privately-owned and therefore depend on endowments and donations, the University of Richmond is heavily concerned with profit. This phenomenon is not unique to UofR. In fact, the operation of most educational institutions - private universities, public universities, and K-12 schoolsrely heavily on capitalistic principles. In universities in particular, these principles manifest in the actions of administrators who foster competition and false ‘trust’ in their respective institution by translating endowments and donations into student enrollment numbers. This is possible in part because parents of university students view endowments and donations as a symbol of ‘trust.’ The larger those streams of income, the more stable these institutions appear, and the more ‘trust’ parents and students are likely to have in the university. In turn, this incentivizes the university to commodify its campus so that it is able to profit from interactions between students and the community and increase this ‘trust.’

From these profitable interactions, it is easy to piece together a narrative that the university is simply interested in promoting student engagement with the larger Richmond community; especially with the inclusion of categories like experiential learning and community engagement as part of the campus’s strategic plan. However, if that was the case, then service shuttles provided through the Center for Civic Engagement (CCE) would be more accessible and the university’s broader attempts to increase community engagement would reach beyond the suburbs that surround the school’s campus.

Instead, when service locations are ‘too far’ or when ‘not enough’ students show interest in a particular location, then the university suddenly becomes unable to provide reliable transportation. A clear example of this occurred my freshman year, in which I was required to participate in experiential learning opportunities in my Justice and Civil Society class. I along with a number of my peers opted to volunteer at Peter Paul Development Center, an organization focused on addressing educational inequities in the east end of Richmond. Yet the CCE, which openly markets service shuttles for student use, was unable to provide transportation for any one of us and we were all instead forced to carpool with the few students who owned cars.

It is important to note here that Peter Paul Development Center is located in a more disadvantaged area of Richmond and is around twenty minutes away from campus. Alternatively, Carytown, which is home to expensive eateries and boutiques, is only around fifteen minutes away. Still, the campus Daily Connector bus manages to make evening stops at Carytown a priority for the sole reason that businesses must understand their audiences if they’re to be monetarily successful. The business that is UofR understands that, regardless of recent strategic marketing to minorities, their audience remains largely white.

I have witnessed arguments between the university’s board of trustees and students over the continued use of racist mens’ names on campus buildings and over inaction on the part of the university in instances of racial violence. In my freshman year alone, white students donned sombreros and ponchos and ignored the racist implications of their ‘costumes,’ and another group of students behaved in a racist manner towards a black delivery driver on campus, punching and kicking the driver’s car.

I have also witnessed the censorship of students by the administration when they attempted to recount any of these past instances of violence to prospective students.

At first, I was surprised as the university markets itself as a fairly progressive and liberal institution, acknowledging the racist history of the school’s conception and the enslaved individuals that died in the process. What really mattered however was their acknowledgement of future goals to do better. So far, the acknowledgement of those plans is one of the few concrete pieces of progress that UofR has produced since, and this inaction on the part of the university emphasizes another competing reality that exists on UofR’s campus, specifically for minority students. In an era where the appearance of ‘inclusivity’ directly translates to political and social capital for non-minority populations, UofR has manipulated this ideology to its advantage and incorporated it into its brand image. In fact, one hardly has to scroll through the school website for more than a few seconds before a black or brown face is smiling on the screen. Despite being overly represented in the school's marketing, however, these same faces struggle the most when it comes to concerns of belonging and inclusivity on campus. This is a common trend in broader society, especially in the political realm where the minority narrative is often manipulated by politicians in order to gain capital. In her novel Birthing Black Mothers, Jennifer Nash explores this phenomenon in the context of the 2020 presidential elections in which white candidate Elizabeth Warren wielded her conversational connection with Eric Garner’s mother like a political weapon.

THE POC REALITY

UofR wields its various diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) boards in a similar manner. These boards, regardless of the intention behind their creation, are largely invisible to the broader campus. They also only seem to emerge into student view when recurring racially unjust incidents prompt them to release performative statements. The past bias reporting system seemed to function in a likewise performative manner and lacked actual accountability for those individuals reported against. It was, only recently, through student action that this system was amended and institutional change was achieved. Still, the university boasts both this bias reporting system and its DEI boards, as well as their commitments to creating an inclusive learning environment like a badge of honor while simultaneously ignoring the fact that many of these accomplishments were only achievable through the actions of students.

Not to be erased, however, are the efforts of many faculty members who, unlike the administration, actively fought alongside students to achieve these changes. I’m sure their outward support is due to the simple fact that they are less concerned with running an institution and therefore less limited by capitalism.

Nonetheless, while the activism on the part of these students is undoubtedly impressive, students shouldn’t constantly have to advocate for themselves, especially for something as simple as the right to belong.

CONCLUSION

Systems that foster belonging, promote involvement within the entire community, and prioritize the learning of students should be as entrenched in UofR as capitalism. The danger in integrating these systems, however, is of course that they may simply become extensions of the university’s carefully calculated brand. Combating this therefore requires not just a change in UofR’s system as a whole but a questioning of foundational American principles that prioritize competition and profit over individuals.

RACIAL JUSTICE IN THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM

INTRODUCTION

The American criminal justice system is meant to stand as a guardian of fairness, equality, and justice. Yet, the reality is far less idealistic and far more troubling. The unfortunate truth is that racial disparities are prevalent within the criminal justice system and highlighted in statistics regarding wrongful conviction. Wrongful convictions are far too prevalent, with approximately 5% of American convictions being wrongful convictions. Furthermore, wrongful convictions ruin innocent lives and leave the trust between society and the justice system in a state of disrepair.

RACIAL INJUSTICE IN THE PRISON SYSTEM

Systemic racism, deeply entrenched within judicial and law enforcement institutions, perpetuates discriminatory practices that disproportionately target racial minorities, specifically African Americans. A study found that one in five American police officers show signs of either pro-white or anti-black implicit biases. While such implicit biases may be unintentional, that does not alleviate the fact that they distort perceptions, and skew judicial outcomes. A study conducted by the Lewis & Clark School of Law also found that African Americans face unique challenges when it comes to getting legal representation. For example, African Americans were 50% less likely to receive callbacks from lawyers when requesting legal aid. Inadequate legal representation further exacerbates the vulnerability of marginalized minority communities that are already being targeted by the judicial system at higher rates.

RACIAL DISPARITIES IN WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS

Extensive research has shown that the racial disparities in wrongful convictions are not statistical coincidences, but indicators of systemic issues. Of the 5% of convictions that turn out to be wrongful convictions, approximately 53% of those wrongfully convicted are African American. That statistic becomes even more concerning when conjoined with the reality that African Americans make up only 13.5% of the American population. Furthermore, African Americans are seven times more likely than White Americans to be wrongfully convicted of murder. The rise of forensic evidence has also led to discrimination. Flawed forensic evidence, used in more than half of wrongful convictions since 1989, is further tainted by confirmation bias and the failure of institutions to implement safeguards against racial bias. It is also important to note that those who are already susceptible to implanted memories are also more likely to misremember the face of someone of a different race, leading white witnesses to disproportionately misidentify African Americans in the context of trials. The reality is that this issue is merely a result of a much larger racial disparity issue within the United States’ judicial system.

WRONGFUL CONVICTION AS A CONSEQUENCE OF RACIAL DISPARITIES

Wrongful convictions have impacts beyond that which is seen in courtrooms and prisons. Those who are wrongfully convicted are real people with real families, jobs, and lives. While those exonerated due to wrongful convictions are often given compensation, no money can make up for the years spent incarcerated. Furthermore, wrongful convictions further erode the already fragile trust that many African Americans have in the American judicial system.

African Americans are already more likely to be apprehended and arrested by police officers, more likely to be tried in a court, and more likely to be found guilty. Their disproportionately high interaction with the American judicial system inherently leads to higher rates of wrongful conviction, especially based on the size of the population in America. Therefore, racial discrimination inherently leads to higher rates of race-related wrongful convictions.

Furthermore, the rate of wrongful convictions among African Americans has long term implications for their families. The emotional and financial toll of navigating the legal system can destabilize households. Those wrongfully detained and convicted often lose their jobs, leading to difficulties reintegrating and regaining financial stability upon release. Research has also shown that African American families are significantly more likely to live in single-parent homes. Further examination shows that those who grow up in a single parent household, and more specifically single mother households, are more likely to end up in the prison system and less likely to pursue higher education. The targeting of African Americans, and the resulting rate of wrongful convictions, can have long term implications for the families that they are forced to leave behind.

CHARTING A COURSE TOWARDS JUSTICE

Confronting racial disparities in wrongful convictions requires a multifaceted approach focused on systemic reforms. Efforts to dismantle systemic racism and combat implicit biases must be prioritized, with improved training, accountability measures, and diversity initiatives. However, these efforts must be meaningful rather than performative. Ensuring equitable access to competent legal representation is imperative, necessitating the expansion of public defender services and the eradication of barriers to quality defense. Additionally, enhancing the reliability and transparency of forensic evidence is critical, requiring higher standards, independent oversight, and scientific integrity. Fostering collaboration between law enforcement and communities is essential, fostering mutual trust, accountability, and understanding. Community-driven initiatives, restorative justice programs, and civilian oversight mechanisms can bridge divides, empower marginalized voices, and hold institutions accountable for their actions.

HEALTHCARE IN THE AMERICAN PRISON SYSTEM

The Declaration of Human Rights and other international agreements maintain that all citizens have the right to health services, essential medicines, and basic human needs like water. This included people in prison. Incarcerated people are entitled to medical and dental care, adequate nutrition, protection from infectious diseases, and safe conditions. Although this is a consistent standard, there are different interpretations of what healthcare as a human right for prisoners looks like.

With there being over 1 million people in the U.S. state prisons on average, this large population is mostly poor, disproportionately Black, Native American, Hispanic, and/or a part of the LGBTQ+ community. Specifically, a 2022 Pew Research Center Report notes Black people account for 33% of the prison population, nearly triple their prevalence in the general population. These characteristics all enforce the individuals being in the spotlight of authorities. This is the key background for statistics and is necessary to keep in mind the overall prisoner demographics.

Speaking on the issue of United States healthcare in total, many prisoners' first demonstration of health services was during incarcerations as they were not insured and did not see physicians when they were in the community. 50% of people in state prisons lacked health insurance at the time of their arrest. This makes any service provided seem like an upgrade, but it is all too common to leave the facility in worse condition than originally.

The need for care stems from the high rate of chronic illness among incarcerated individuals. About 80% of incarcerated individuals have been diagnosed with a chronic condition, including illnesses like hypertension, diabetes, asthma, COPD, hepatitis C, HIV, substance abuse, and mental health conditions. Moreover, these ailments commonly do not stand by themselves. This is from the prevalence of both physical and mental illness, as well as disability and pregnancy. Rates are higher in prisons compared to the general population, but consideration of inadequate health care prior to being incarcerated accounts for incomplete diagnoses. Their health issues may begin before their arrest, but incarceration often exacerbates or creates more problems. In the end, the care is designed to be a baseline in its coverage. Prison healthcare is meant to be reactionary, treating acute healthcare problems rather than taking any preventative measures or treating chronic diseases.

Diabetes is a good example to use from its nationwide commonality. About 8% of all individuals, and 23% of older people, have been diagnosed with diabetes. How could something so common be something that prisons and other correctional facilities frequently fail to treat? Diabetes requires careful management of blood sugar levels. There are several lawsuits showing direct neglect of life-or-death situations when diabetic incarcerated people needed timely food, insulin, or medical equipment. Not only is the lack of attention dangerous within itself, but the inmates newly diagnosed will have no ability to manage their own medicine or draw their own insulin.

While in the facilities, an inmate who wants treatment must first be seen by a correctional officer. It is within that individual, with their lack of medical expertise, to decide whether a nurse or physician is needed. Although the care is present, the restrictive access procedures create barriers that are aligned with the structure of prison systems. The care is not always free, as some states require inmates to pay. While working for $0.75 a day, any mount is unaffordable. With that being said, 81% of people in state prison report having seen at least one healthcare provider since their incarceration. Although in the majority, still, 1 in 5 (19%) have gone without seeing any health specialist since their admission.

When inside the prison, their care is sparse and menial; while leaving, they are in worse condition than prior. Moreover, a criminal record often severs access to any outside community health care. With 80 million individuals in the United States having a criminal record, Wang, a former primary care physician for death row inmates, claims “they are impacted not only by having been incarcerated but also by a system of collateral consequences. Laws, policies, and practices in many states prohibit those with a criminal record from getting health care, housing, food stamps, and employment.” Not only in consideration of the individual being affected but the families of the incarcerated population are left in worsened living conditions. The family, as a result, is left with decreased economic resources, reduced social support, housing instability, and stress and stigma. In terms of the prisoner being released, the medical transition is not a point of ease in this process; the individual gets a limited supply of medications and a list of what they need.

United States prisons fall short of their constitutional duty to meet the essential health needs of people in their custody. As a result, incarcerated citizens are stuck in a constant state of illness and despair. Against their well-being, maintaining good health is seemingly an impossible achievement for prisoners. Due to the evident lack of care or simple compassion, there is the long-term effect of distrust between health officials and prisoners that is inescapable in the current circumstances. This results in inmates not knowing how to get adequate care for themselves, and even being discouraged from wanting to. The healthcare available, as well as therapeutic programs, demonstrate that from a lack of care and resources, it is impossible for prisoners to actually benefit from the systems in place. There needs to be a heightened degree of rehabilitation in all regards, leading to encouragement for the incarcerated individuals to leave and live differently. With the needed change, the programs would serve their true purpose of infiltrating the individuals back into society, being of benefit to them, their families and loved ones, and possible victims. Rehabilitation programs serve a critical role in reducing recidivism.

THE HISTORY OF REDLINING IN THE CITY OF RICHMOND

The federal and state governments adopted the problematic practice of redlining in the 1930s. When deciding how to distribute money to the many neighborhoods and cities across the U.S., they established the following criteria to describe the various district areas: "'best,' 'still desirable,' 'declining,' or 'hazardous.'" Unfortunately, the officials demonstrated their racist biases, as they typically classified Black and immigrant neighborhoods as 'hazardous,' outlining them in red (hence the name redlining). Consequently, residents in redlined areas suffered from a lack of federally backed mortgages and other types of credit over several decades, fueling a cycle of disinvestment. Not only does it become important to study this phenomenon, but the ways in which officials justified these dynamics. Oftentimes, the language officials used when describing redlined neighborhoods highlights the racist ideologies by which they operated. As one can imagine, decades of these racist policies continue to affect the residents who live in redlined areas, severely diminishing the quality of their everyday lives.

During these periods, officials wrote a series of clarifying remarks about the various neighborhoods within a given city or county. The language they utilized to describe these areas becomes incredibly important. When discussing area D8 in Richmond (which borders Hollywood Cemetery), officials noted the following: “Negroes crowded out of D-1 are crowding white men out of the aged and obsolete structures of D-8.” The use of the verb “crowding” is very telling, as it suggests that Black people intentionally unified to forcibly push white people out of the neighborhood. Consequently, it paints white communities as the victims of vicious attacks from Black people. Not only do these claims support harmful racial stereotypes that depict Black people as harmful and dangerous, but they also reinforce ideas of white victimhood and superiority. Additionally, the words “aged” and “obsolete structures” highlight the perceived status of the district. According to the city officials, the buildings in this area are in the process of crumbling into disrepair, ruining their original intended purposes. Through using language and rhetoric, the officials develop a perception of D-8 as a neighborhood full of hostile individuals who can't prevent their buildings from becoming dilapidated and uninhabitable.

Similarly, in area C-4, which borders area D-8, officials commented that “This area is yellow, largely because the school for white children is in the negro area, D-8, and because the negroes of D-8 pass back and forth for access to the William Byrd Park which lies to the west. For this reason losses on properties are being taken.” As a result, it becomes clear that city officials believe the presence of Black spaces and communities have a negative impact on whiter neighborhoods, making them undesirable. Therefore, the audience can observe how city officials attempted to create a physical distance from these communities by classifying this area as 'yellow' and unfit for receiving substantial amounts of government funding.

In other area remarks, city officials intentionally disregarded the presence of Black communities. For example, in area D-1, they observed that the district had a land occupancy rate of 75% with a 90% occupancy rate in dwelling units. Homes were occupied by 20% of the population, suggesting that not as many families had the funds to purchase entire houses. Despite the high rates of occupancy in these areas, city officials noted that the "Population [was] decreasing because of demolition to save taxes.” To no one's surprise, over 90% of residents in this neighborhood were Black. Their explanation serves as an attempt at erasure that dehumanizes Black communities by suggesting that they weren't worthy enough to even be mentioned in important government documents. Thus, the language utilized by city officials demonstrates how both the Federal and state governments worked to uplift white communities while simultaneously harming communities of color.

The results of these racist and problematic policies are still felt today. For instance, in Gilpin, more than 2,000 residents, most of whom are Black, live in low-income public housing units that lack essential accommodations, such as air conditioning. These dynamics have created harmful living environments for these individuals. The lack of investment in these neighborhoods means that few green spaces exist in these areas. Instead of an abundance of parks or trees, residents live in spaces with excessive amounts of concrete and other materials that rapidly absorb heat. Consequently, in the summer months, these neighborhoods typically become 5-20 degrees warmer than other areas in the city. As a result, Shelly Thompson, a community health worker in Gilpin explains that "residents have high rates of asthma, diabetes, and blood pressure, all conditions that can be worsened by heat. They are also exposed to air pollution from the six-lane highway next door." To further compound the severity of the issue, the lack of investment in these neighborhoods also means that there are fewer doctor’s offices, grocery stores, and other materials that rapidly absorb heat. Consequently, in the summer months, these neighborhoods typically become 5-20 degrees warmer than other areas in the city. As a result, Shelly Thompson, a community health worker in Gilpin explains that "residents have high rates of asthma, diabetes, and blood pressure, all conditions that can be worsened by heat. They are also exposed to air pollution from the six-lane highway next door." To further compound the severity of the issue, the lack of investment in these neighborhoods also means that there are fewer doctor’s offices, grocery stores, and other necessary types of facilities in these areas. Thus, residents must travel, sometimes on foot, long distances to purchase healthy foods or find adequate health care. And as Ms. Thompson questions, ‘“If you have asthma but it’s 103 degrees out and you're not feeling well enough to catch three buses to see your primary care physician, what do you do?’” All in all, the results of decades of redlining have created a host of intersectional issues that continue to negatively impact people of color by greatly diminishing the quality of their lives.

In conclusion, the language used by city officials to justify policies pertaining to redlining created a cycle of disinvestment that actively harms neighborhoods of color. Even though more people have become aware of redlining in recent years, much work must be done to fix these issues and establish a sense of equity. Officials in Richmond's Sustainability Office have outlined a tentative plan of attack to improve the quality of life in many underinvested districts. To name a few, city planners would like to ensure that everyone in Richmond is a 10 minute walk away from a park. They also hope to increase the number of trees in notoriously hot neighborhoods, redesign buildings to increase airflow, and use materials with lighter colors. However, many of these ideas will not only take years to accomplish, but also require higher levels of funding. Not to mention, bringing about these changes risks the potential for gentrification, which tends to displace people of color, reinforcing harmful cycles for these communities. Thus, officials need to exert caution when thinking about long-term solutions, making sure they prioritize the well-being of communities of color to prevent these cycles from continuing.

COMBATTING THE OVERDISCIPLINING OF BLACK GIRLS IN HENRICO PUBLIC SCHOOLS

\ In the fall of 2017,* there were over 50 million students enrolled in public schools across the United States. Of these 50 million, only 7.7 million were Black, making up a total of just 15 percent of students in the American public schooling system. Despite these statistics, and Black students being a definitive minority in the American public school system, Black students make up 32% of all suspensions, and are 2 times more likely than their white counterparts— who make up over 50% of the schooling population to be suspended. The problem does not lie with cultural deficiencies in Black students, as dominant narratives suggest, but rather, the teachers and administrators themselves, who carry their own racial biases to schools. Stereotypes labeling Black students as more violent and hypersexual result in teachers punishing Black students for subjective and innocuous incidents, like “talking back,” walking the hallways without a pass, or using profanity. In essence, Black student’s actions are viewed through a distorted lens— one in which inane slip ups become worthy of extreme disciplinary action.

In conversations regarding discipline, Black girls rarely receive the attention of their Black male counterparts, resulting in a gap both in academia and societally that ignores their unique struggles regarding discipline in schools. While Black boys receive discipline in an effort to quell perceived “violent” attitudes, Black girls receive discipline in an effort to have them align with stereotypical forms of Western femininity. Black girls undergo the same policing, punishment, and psychological trauma as Black boys, but this is largely ignored and continues to go unnoticed by most of the world. Discipline often has negative consequences on the self esteem of Black girls, as well as their feelings of belonging.

At Henrico County Public Schools, this narrative of Black students being disproportionately disciplined is unchanging. According to a 2012 report titled HCPS Discipline Data Analysis & Strategy Development, Black students as a whole received out of school suspensions at nearly 4 times the rate of white students, a significant decrease from years prior.* Black students only made up 23% percent of the Henrico County Public Schools’ population in 2012, yet comprised a staggering 72% of all suspensions. When breaking this down by gender, data from the 2019-2020 school year reveals that Black girls received 10.8 times the amount of out of school suspensions than their white female peers, and 2.8 times the number of in school suspensions. The problem is clear: Henrico County has enormous work to do regarding the over-disciplining of Black students, and Black girls are a standout demographic that needs significant assistance in achieving equity in HCPS.

The mission statement of Henrico County Public Schools paints a clear, invigorating picture of success and achievement. “Henrico County Public Schools, an innovative leader in educational excellence, will actively engage our students in diverse educational, social and civic learning experiences that inspire and empower them to become contributing citizens.” Inspiration and empowerment are key to the HCPS vision. Yet the over disciplining of Black girls actively rejects this notion. Research shows that Black girls who receive excessive discipline than their peers are less likely to believe that they will attend college, more likely to have lower levels of belonging and confidence, and ultimately, well prepared for the violence of the carceral state outside of school due to the violence experienced within. If Henrico County Public Schools truly wishes to empower its students and make them better citizens, then school officials should have every motivation to get to the root of this disparity by working to overcome the systemic forces that disproportionately penalize Black female students.

PRE-EXISTING POLICIES

Henrico County Public Schools has not had a substantial amount of progress in regards to closing the discipline gap in the past decade. In 2012, Black girls were 6 times more likely to receive out of school suspensions; by the 2019-2020 school year this had increased to Black girls being 10 times more likely to receive OSS. It’s important to examine policy action taken in the last 10 years to examine how, if any, policies have helped reduce disproportionate discipline received by Black girls.

In 2015 HCPS removed zero tolerance policies, instead aiming to keep students in schools even with multiple disciplinary infractions. In addition, the removal of out of school suspensions for some subjective infractions resulted in the out of school suspension rate dropping by 45% between 2010 and 2015, and reduced the number of arrests by 96% between 2017 and 2018. A report conducted for HCPS in 2018 titled “A Review of Equity and Parent Engagement in Special Education” found that even despite these overall declines, Black students of all genders, particularly those with disabilities, were still more likely to receive short term out of school suspensions, and were more likely to be suspended for subjective infractions. But both of these reports do not highlight gendered differences within the overall Black student demographic, leaving questions as to how this decline differs between Black girls and Black boys.

In October of 2021, Elko Middle School held a showing of the movie “Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools” in conjunction with the Department of Family and Community Engagement and the Disciplinary Review Hearing Office. In a video explaining the purpose of the event, William Noel Sr., the director of the Disciplinary Review Hearing Office, acknowledges the disparity in suspensions. He attributes disproportionate discipline to a multitude of causes, including “a lack of cultural understanding, diversity understanding, [or] cultural competence [or] implicit bias.” Not once in the video is it mentioned that school policy can be used as a tool against over-disciplining, which, as one student remarks in the video, is often for petty offenses like walking in the halls without a pass. The video is the first result when searching “suspension” on the HCPS website and is featured on their YouTube page, demonstrating a wider community acknowledgement of this problem.

In addition, Henrico County has also implemented the use of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS). As a broad framework, PBIS works to reduce school suspensions and other exclusionary discipline practices in a data driven manner that reviews a number of different paths for discipline. According to the Henrico County Public Schools website, the HCPS PBIS system uses a five tiered approach of “equity, systems, data, practices, and outcomes.” HCPS attempts to reduce punitive measures by shifting classroom practices, emphasizing a focus on “culture and equity” and providing support for educators. The main outlet of support comes from an “Intervention Team” which meets weekly to assess student needs by analyzing data.

Though HCPS has only recently begun to implement PBIS on a county-wide level, research has suggested that implementing PBIS does not necessarily reduce racial disparities in discipline, though it does reduce overall suspensions. Combining this knowledge with a lack of relevant data, as well as a vaguely worded webpage regarding the topic, it becomes unclear if PBIS has been successful in its implementation thus far.

Despite attempts to decrease overall suspensions and other disciplinary infractions for all students, there still remains a disparity in how Black students overall are disciplined in Henrico County Public Schools. In addition, there is a considerable lack of data demonstrating how these disparities differ between Black girls and Black boys, creating questions to the effectiveness of implemented policies to reduce these disparities despite an explicit acknowledgment from HCPS that there is a problem.

POLICY OPTIONS AND SOLUTIONS

While Henrico County has made several steps in addressing racial disparities, there is still work to be done regarding racial disparities in suspension rates. There are multiple policy options to be considered which have been implemented by other school districts with similar problems across the country, such as restorative justice, PBIS, and more. But there are others that are emerging with new research that could potentially solve HCPS’ problems.

Empathic-Mindset Intervention (EMI) is one of the newest yet most innovative approaches to reducing racial disparity gaps. It is a model that is the work of University of California Berkeley Professor Jason Okonofua, who has published multiple articles and studies regarding the topic. Empathic-mindset intervention encourages teachers in K-12 schools to develop closer relationships with their students that are built on mutual trust and respect, fostering an environment which reduces disciplinary action. Empathic mindset intervention works within the teacher’s capabilities as educators and individuals, using the basic principle of empathy to bolster its goals. One study found that EMI was able to reduce in school suspensions by 34%, with another demonstrating that after taking a brief online module suspensions reduced by half. Most crucially, Okonofua’s research has found that not only does EMI reduce suspensions overall, but it also reduces racial disparities. One of Okonofua’s studies that specifically focused on racial disparities found that suspension disparities decreased by 10 percent for Black and Hispanic students.

In addition, EMI also does not require much from educators while still being able to make a significant impact. EMI relies on the reading of articles, short responses, and online modules, making it achievable for teachers to receive an impactful EMI education while not spending a considerable amount of time on such matters. In a county like HCPS which has to consider the needs of teachers who have to teach dozens of students daily, this option makes feasible sense to preserve the energy and time of educators. In terms of reasonable policy options, this presents a relatively simple solution to an extremely complex problem.

Lastly, this policy is backed by the Department of Education and has been cited by several studies in major journals, demonstrating its legitimacy as a practice. Deceptively simple and exceedingly effective, EMI works to benefit Black girls by reducing racial disciplinary gaps, and by reducing suspensions overall.

CONCLUSION

The over disciplining of Black girls in the American public school system remains a persistent and ongoing issue which affects millions of students each and every day. The reality is, however, that this is a problem that is largely a policy choice. By implementing policies that allow teachers and administrators to change the biases that they might possess against Black girls, we can create a better, more inclusive schooling environment. Though Henrico County Public Schools represents one school district in one state, it serves as a microcosm for an issue that has replicated itself across the country, and perhaps one day, can serve as a model for potential solutions.

CONTRIBUT0RS

Lily Dubrovich

Camille Duran

Sydney Dwyer

Maddie Fellner

Makayla Hamlin

Christian Herald

Myanna Hightower

Kristine Nguyen

writers Cover Design & Social Media team

Camille Duran

Debora Lemma

Tsion Maru

Camille Duran

Cover Photo models

Doro Azizi

Chelsea Waruzi

Executive board

Sydney Dwyer

Christian Herald

Lily Dubrovich

Maddie Fellner

Myanna Hightower

Editor’s Note: To protect privacy, ensure freedom of speech, and emphasize our collective unity regarding the issues we write about, Counterculture does not use individual articles, instead including a contributors list at the end of each issue.

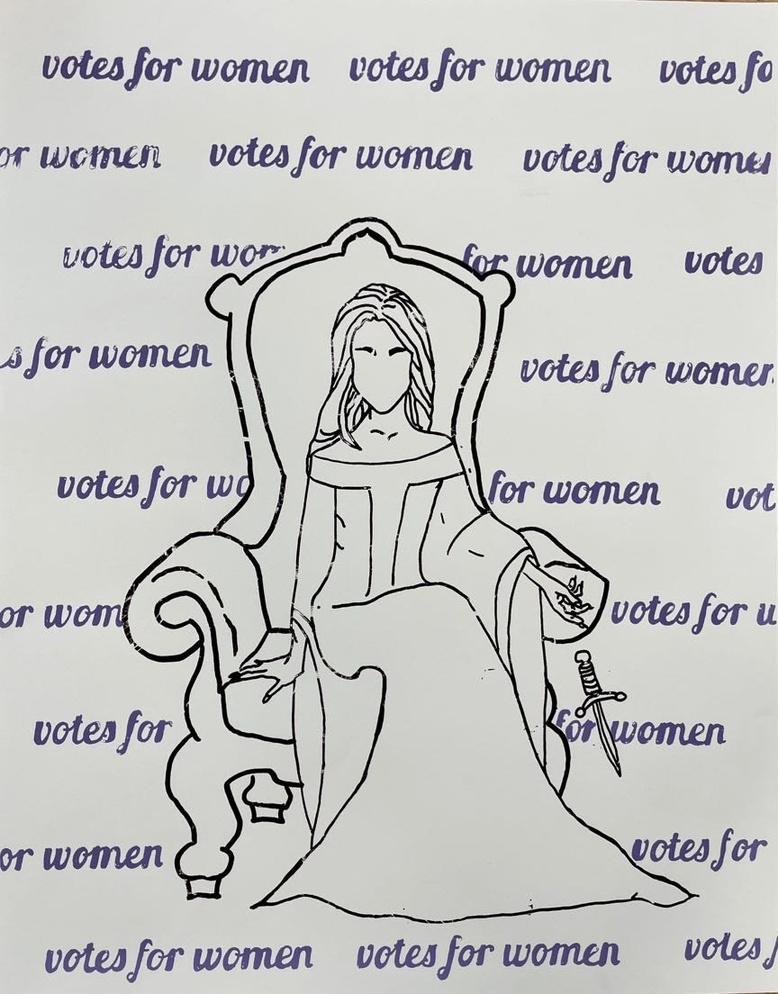

Judith on a Throne