ACADEMIC Portfolio

Masters of Architecture // PART 2

ESALA | M(Arch) | 2022-2024

Masters of Architecture // PART 2

ESALA | M(Arch) | 2022-2024

CORMAC LUNN

ESALA | M(Arch) | 2022-2024 Masters of Architecture // PART 2

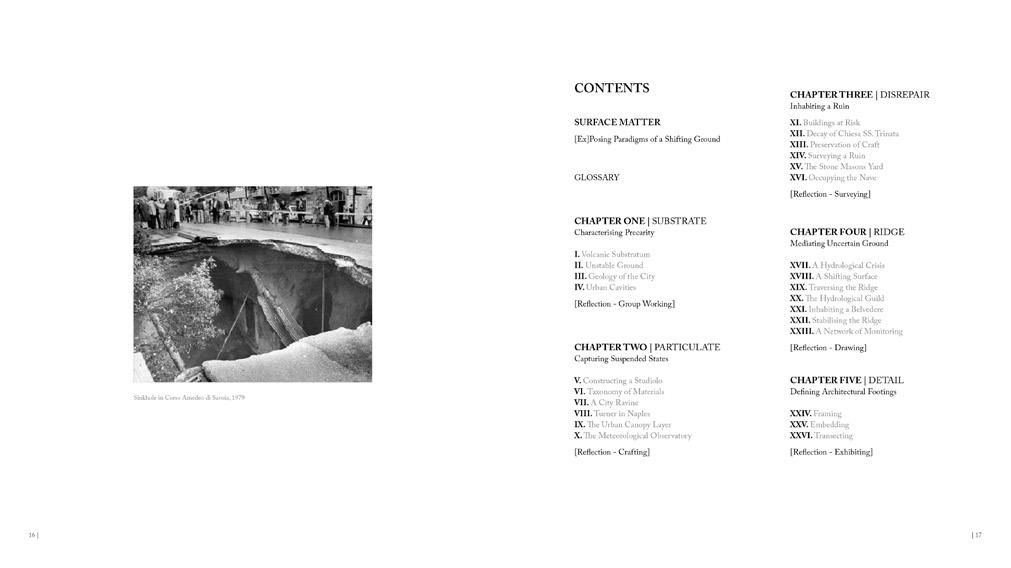

This Academic Portfolio offers a comprehensive record of academic work completed throughout the duration of the 2022-2024 Masters of Architecture program at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture [ESALA]. The collection encompasses a diverse range of thematic explorations, featuring a twoyear design thesis undertaken within the ‘Grounding Naples’ integrated pathway, theoretical essays and journals in ‘Unpacking Log,’ , and a selection of technical projects and drawings completed during the ATR and AMPL courses. Serving as a meticulously curated representation of academic achievements, this portfolio reflects both personal fulfillment and adherence to the professional standards required for the RIBA Part 2 qualification.

This course, taken in the final semester of the programme, requires students to curate the outcomes of academic work undertaken during the programme and present it in the form of an integrated academic portfolio that demonstrates compliance with the ARB Part 2 criteria. Various forms of presentation (drawings, installations, printed books /reports, models, photographs, films, digital material, etc.) and any other evidence of work, which has been assessed as part of the programme leading to an award of Part 2, will be represented in the portfolio.

LO1

The ability to produce a coherent, well designed and integrated architectural design portfolio that documents and communicates architectural knowledge, skills and abilities through coherent projects; and that synthesizes and presents work produced in diverse media (sketch books, written work, drawings and models, etc).

LO2

An understanding of the relation of the ARB Part 2 criteria and Graduate Attributes to the student’s own work, as demonstrated through a referencing system, covering the totality of the criteria, in the portfolio.

LO3

The acquisition and development of transferable skills to present work for scrutiny by peers, potential employers, and other public groups through structuring and communicating ideas effectively using diverse media.

GC1

Ability to create architectural designs that satisfy both aesthetic and technical requirements.

GC2

The graduate will have the ability to:

GC 1.1 prepare and present building design projects of diverse scale, complexity, and type in a variety of contexts, using a range of media, and in response to a brief;

GC 1.2 understand the constructional and structural systems, the environmental strategies and the regulatory requirements that apply to the design and construction of a comprehensive design project;

GC 1.3 develop a conceptual and critical approach to architectural design that integrates and satisfies the aesthetic aspects of a building and the technical requirements of its construction and the needs of the user.

Adequate knowledge of the histories and theories of architecture and the related arts, technologies and human sciences.

The graduate will have knowledge of:

GC 2.1 the cultural, social and intellectual histories, theories and technologies that influence the design of buildings;

GC 2.2 the influence of history and theory on the spatial, social, and technological aspects of architecture;

GC 2.3 the application of appropriate theoretical concepts to studio design projects, demonstrating a reflective and critical approach.

GC3

Knowledge of the fine arts as an influence on the quality of architectural design.

The graduate will have knowledge of:

GC 3.1 how the theories, practices and technologies of the arts influence architectural design; 2 12 2

GC 3.2 the creative application of the fine arts and their relevance and impact on architecture; 2 2

GC 3.3 the creative application of such work to studio design projects, in terms of their conceptualisation and representation.

GC4

Adequate knowledge of urban design, planning and the skills involved in the planning process.

The graduate will have knowledge of:

GC 4.1 theories of urban design and the planning of communities;

GC 4.2 the influence of the design and development of cities, past and present on the contemporary built environment;

GC 4.3 current planning policy and development control legislation, including social, environmental and economic aspects, and the relevance of these to design development.

GC5

Understanding of the relationship between people and buildings, and between buildings and their environment, and the need to relate buildings and the spaces between them to human needs and scale.

The graduate will have an understanding of:

GC 5.1 the needs and aspirations of building users;

GC 5.2 the impact of buildings on the environment, and the precepts of sustainable design;

GC 5.3 the way in which buildings fit into their local context.

GC6

Understanding of the profession of architecture and the role of the architect in society, in particular in preparing briefs that take account of social factors.

The graduate will have an understanding of:

GC 6.1 the nature of professionalism and the duties and responsibilities of architects to clients, building users, constructors, co-professionals and the wider society;

GC 6.2 the role of the architect within the design team and construction industry, recognising the importance of current methods and trends in the construction of the built environment;

GC 6.3 the potential impact of building projects on existing and proposed communities.

Understanding of the methods of investigation and preparation of the brief for a design project.

The graduate will have an understanding of:

GC 7.1 the need to critically review precedents relevant to the function, organisation and technological strategy of design proposals;

GC 7.2 the need to appraise and prepare building briefs of diverse scales and types, to define client and user requirements and their appropriateness to site and context;

GC 7.3 the contributions of architects and co-professionals to the formulation of the brief, and the methods of investigation used in its preparation.

The necessary design skills to meet building users’ requirements within the constraints imposed by cost factors and building regulations.

The graduate will have the skills to:

GC 10.1 critically examine the financial factors implied in varying building types, constructional systems, and specification choices, and the impact of these on architectural design;

GC 10.2 understand the cost control mechanisms which operate during the development of a project;

GC 10.3 prepare designs that will meet building users’ requirements and comply with UK legislation, appropriate performance standards and health and safety requirements.

GC8

Understanding of the structural design, constructional and engineering problems associated with building design.

The graduate will have an understanding of:

GC 8.1 the investigation, critical appraisal and selection of alternative structural, constructional and material systems relevant to architectural design;

GC 8.2 strategies for building construction, and ability to integrate knowledge of structural principles and construction techniques;

GC 8.3 the physical properties and characteristics of building materials, components and systems, and the environmental impact of specification choices.

Adequate knowledge of the industries, organisations, regulations and procedures involved in translating design concepts into buildings and integrating plans into overall planning.

The graduate will have knowledge of:

GC 11.1 the fundamental legal, professional and statutory responsibilities of the architect, and the organisations, regulations and procedures involved in the negotiation and approval of architectural designs, including land law, development control, building regulations and health and safety legislation; 123 2

GC9

Adequate knowledge of physical problems and technologies and the function of buildings so as to provide them with internal conditions of comfort and protection against the climate.

The graduate will have knowledge of:

GC 9.1 principles associated with designing optimum visual, thermal and acoustic environments;

GC 9.2 systems for environmental comfort realised within relevant precepts of sustainable design;

GC 9.3 strategies for building services, and ability to integrate these in a design project.

GC 11.2 the professional inter-relationships of individuals and organisations involved in procuring and delivering architectural projects, and how these are defined through contractual and organisational structures; 2 2

GC 11.3 the basic management theories and business principles related to running both an architect’s practice and architectural projects, recognising current and emerging trends in the construction industry.

With regard to meeting the eleven Graduate Criteria at Parts 1 and 2 above, the Part 2 will be awarded to students who have:

GA 2.1

Ability to generate complex design proposals showing understanding of current architectural issues, originality in the application of subject knowledge and, where appropriate, to test new hypotheses and speculations;

Ability to evaluate and apply a comprehensive range of visual, oral and written media to test, analyse, critically appraise and explain design proposals;

Ability to evaluate materials, processes and techniques that apply to complex architectural designs and building construction, and to integrate these into practicable design proposals;

Critical understanding of how knowledge is advanced through research to produce clear, logically argued and original written work relating to architectural culture, theory and design;

Understanding of the context of the architect and the construction industry, including the architect’s role in the processes of procurement and building production, and under legislation;

Problem solving skills, professional judgment, and ability to take the initiative and make appropriate decisions in complex and unpredictable circumstances; and

2.7

Ability to identify individual learning needs and understand the personal responsibility required to prepare for qualification as an architect.

[Year]

Tutor Name

Tutor Name

Course Title Title which summarises the succeeding course and body of work.

Course Synopsis Learning Outcomes

A summary of the course brief outlining the expectations and scope of the relevant body work.

A summary of the course brief outlining the expectations and scope of the relevant body work.

This studio explores the ideas of . .

LO1 - The ability to develop . .

LO2 - A knowledge of . .

LO3 - A critical understanding of . .

[Contributors]

Student Name

Student Name

BRIEF // TASK / TITLE

Sub Criteria

General Criteria Graduate Attributes

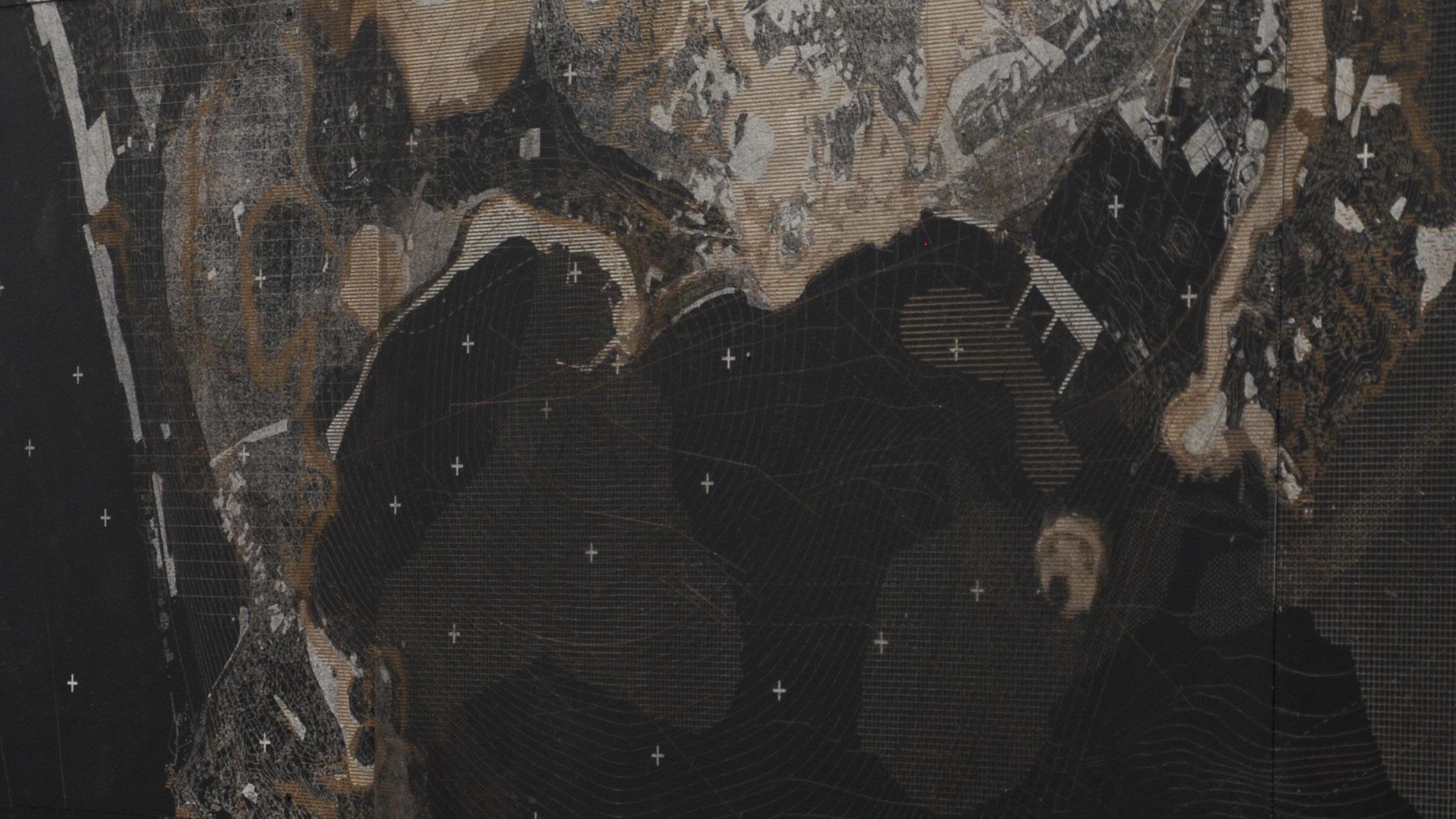

Visual markers of the ARB General Criteria shadows development from Ground Naples during design studio H.

Module Brief Breakdown

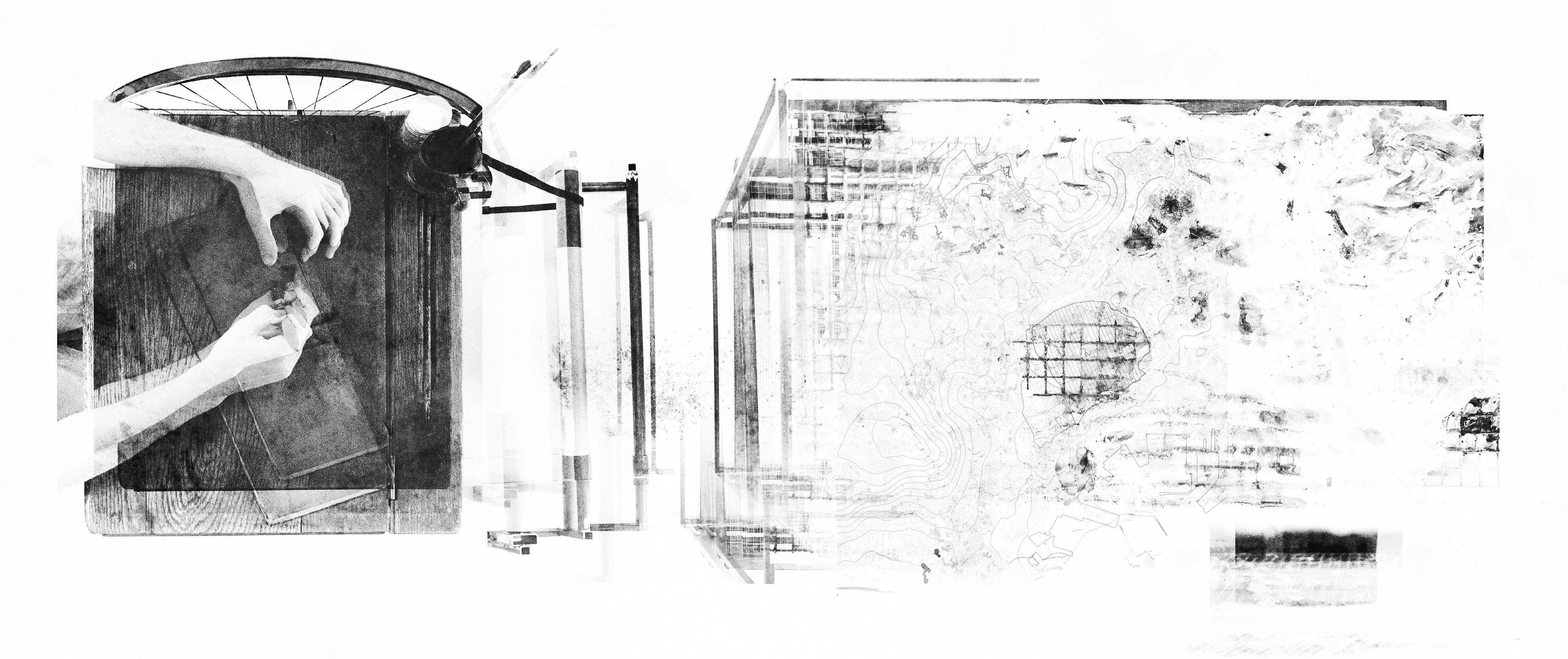

A selection of key images curated to visually describe the thematic notions explored within the course.

Course Index

Mapping includes a page number of the readers progression through the mapped course, and academic term the course was completed and the indexed course

Response

Reflective Paragraph

A selection of key images curated to visually describe the thematic notions explored within the course.

Collaboration Acknowledgment

I have been lucky enough to collaborate across a multitude of course over the two year MArch course with my creative and talented peers. Initials of collaborators are highlighted when the work has been the result of a shared effort.

renders development from Ground Naples during design studio H.

[Course Synopsis] [Course Aims]

[Course Organiser]

Kate Carter

[Contributions]

Isaac Sherriff [IS]

Isabelle Warren [IW}

Wenjing Xiao [WX]

Zhaoyi Yan [ZY]

The aims of this course are:

1. To develop approaches for research in technology and environment, and reflect on its role in the design process.

2.To help create an ongoing interest in the acquisition and synthesis of knowledge regarding the design, construction and performance of built form.

3.To investigate the link between architecture and the Climate Emergency.

Architectural Technology and Research recognises the growing need for a deeper relationship between practice and academia, particularly regarding research and its application in practice.

Methods of building are continually changing and evolving across the world. New materials; new processes; and new design tools create an environment where traditional paradigms may have less validity.

The course focuses on the research process and the discovery of new knowledge in the context of architecture, technology and environment. Students will work in small groups to develop two research projects leading to two outputs. Task 1 will be a response to existing built environment and the climate emergency, Task 2 will be a response to a specific context that can be linked to the design studio. The process will be supported by tutorials throughout the semester.

[Learning Outcomes]

LO1

An ability to appraise the technological and environmental conditions specific to issues in contemporary architecture, eg. sustainable design.

GC 5.2, 7.1, 8.1, 9.1, 9.2 // GA 2.3

LO2

An ability to organise, assimilate and present technological and environmental information in the broad context of architectural design to peer groups.

GC 9.1, 9.2 // GA 2.2, 2.3 LO3

An ability to analyse and synthesise technological and environmental information pertinent to particular context (eg. users, environment).

GC 5.1, 5.3, 7.1, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 9.1, 9.2 // GA 2.3

LO4

An understanding of the potential impact of technological and environmental decisions of architectural design on a broader context.

GC 5.1, 5.2,5.3, 8.3 // GA 2.3

Task

80% of buildings that will exist in 2050 have already been built. The study will respond to the issues created by existing built environment in the ‘Climate Emergency’. It will be framed around an existing site with a number of listed buildings.

The study requires research into the impact of our design decisions and the development of a design response to an existing building. The focus will be on the embodied and operational carbon across the life of a building.

Response

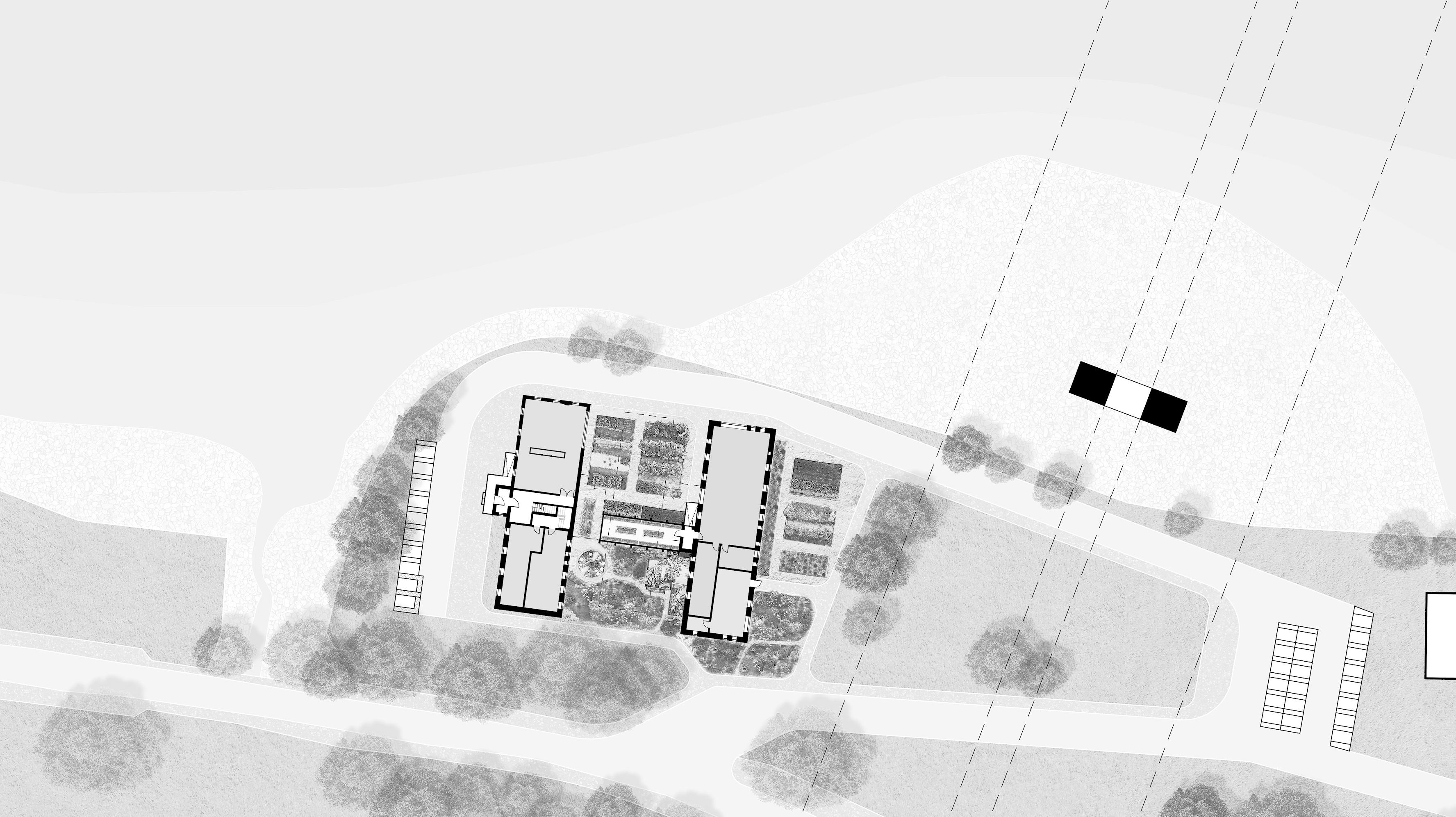

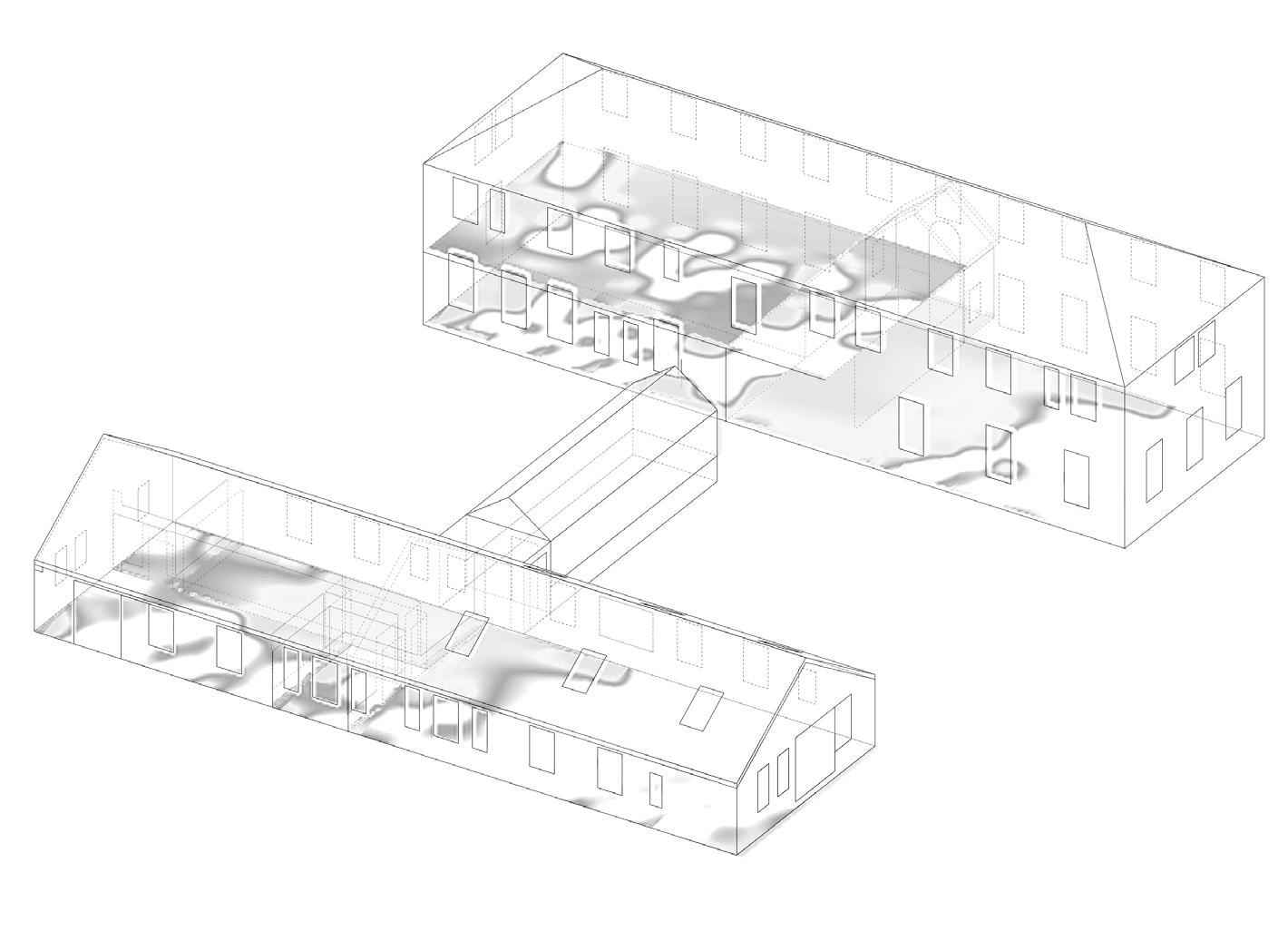

Active Neighborhoods is a social regeneration project seeking to build five core community pillars within the LAR Housing Development at Port Edgar. These pillars being: local community space, a circular local economy, an active transport network, clean energy and biodiversity. Given the buildings isoulated coastal site, the pillars of this retrofit project were built upon the principles of a 15 minute neighborhood, creating a programme which enables the residents of the new Port Edgar Housing Development to reach the vast majority of their day to day needs within a short walk from their home.

The pillars we identified for achieving a 15 minute neighbourhood were: local community space, a circular local economy, an active transport network, clean energy and biodiversity. Our programme is designed to engage with all local demographics throughout all times of the day; establishing the former “Officers Mess” as a multipurpose community hub.

We aim to build these five active pillars of community through the construction of a Village Hall, Community Garden, Net Zero Gym, Local

We identified from census data that working age people make up the majority of the local population, with 16-64 year olds accounting for 55% of the local area. With employment being predominantly sourced in the city, a sizable commute can make life all the more hectic - having all the essentials on your doorstep as well as an active social life and accessible fitness can make all the difference (Scotland’s Census, 2011).

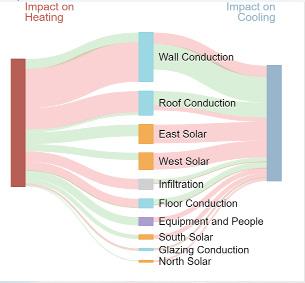

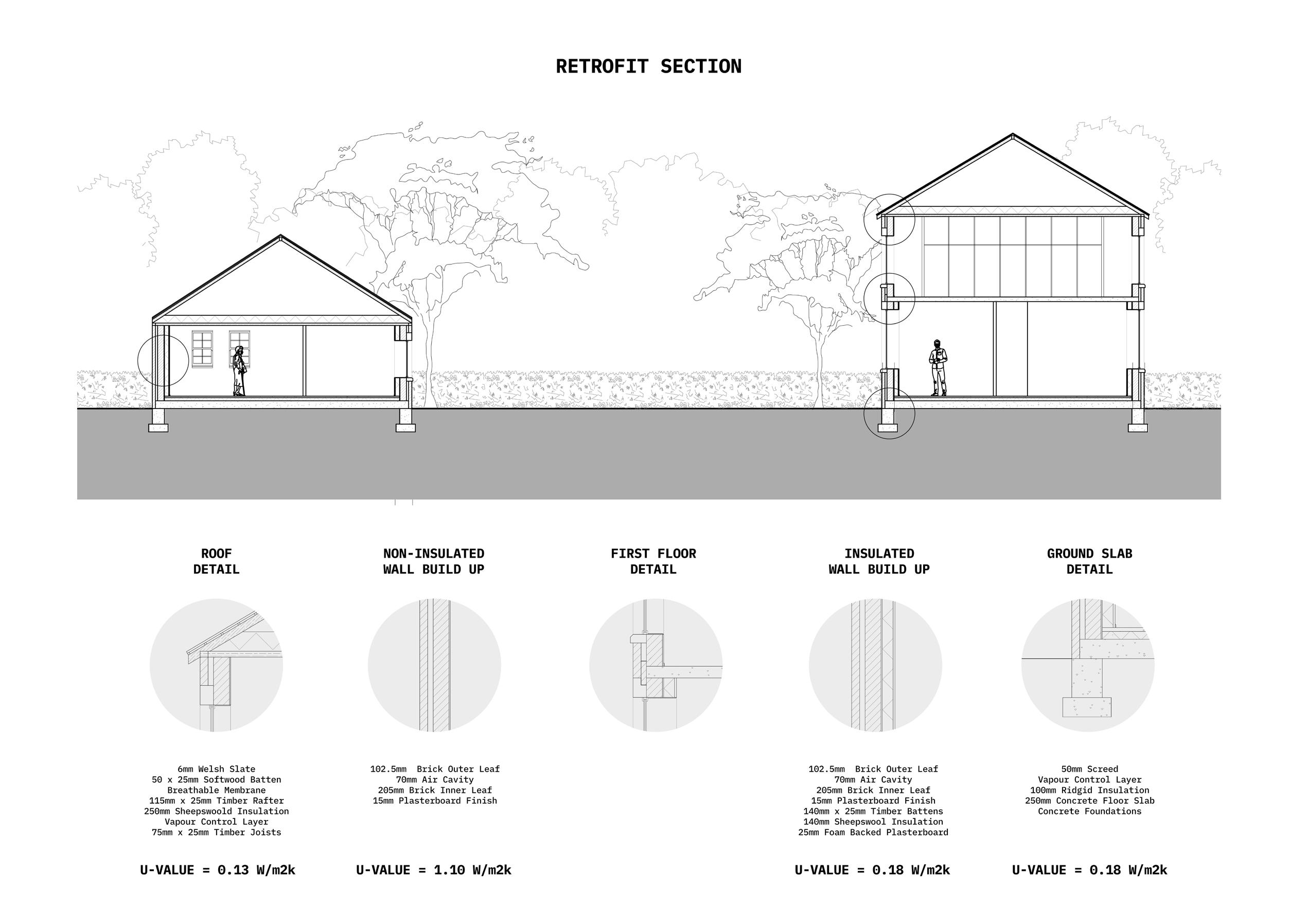

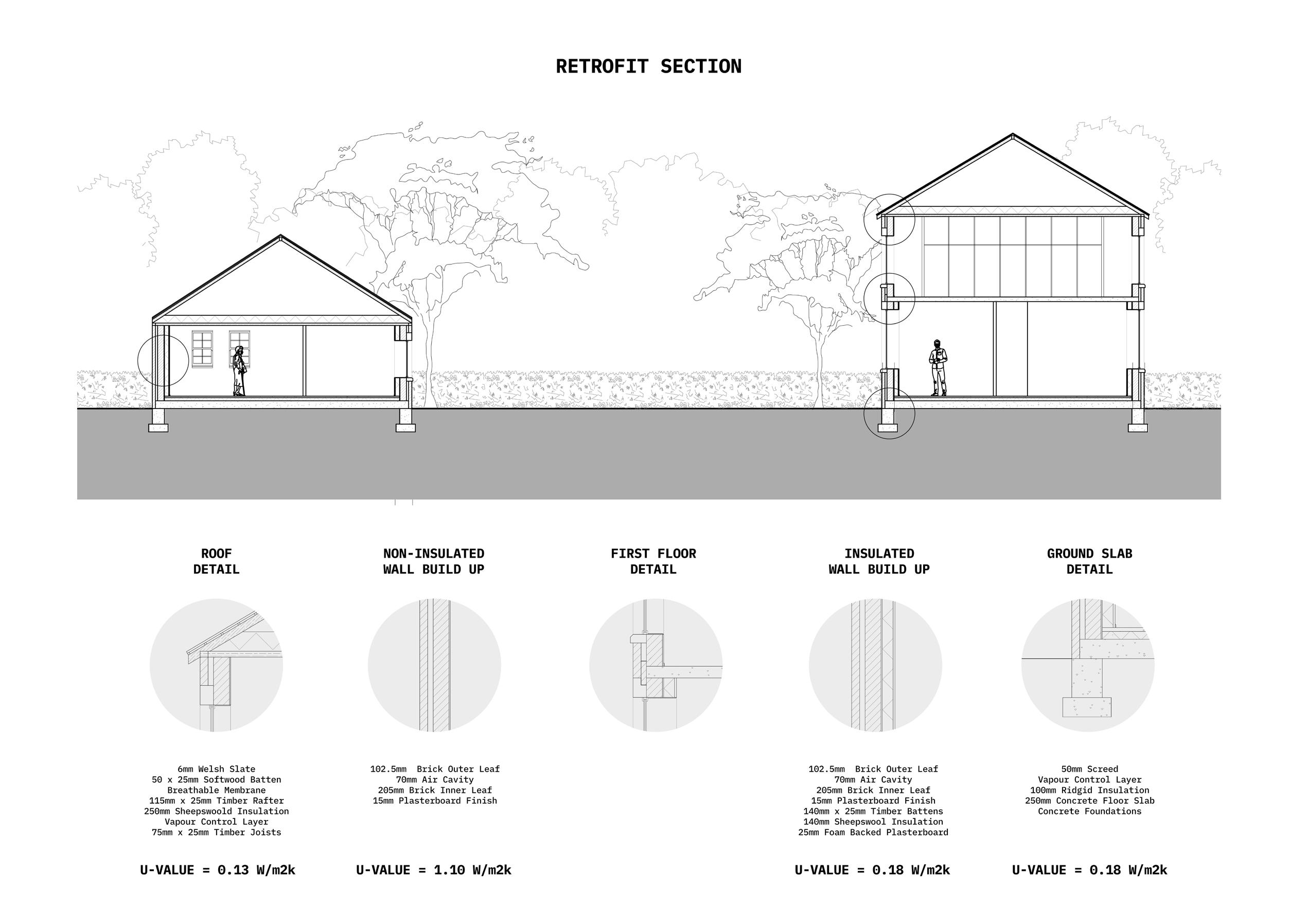

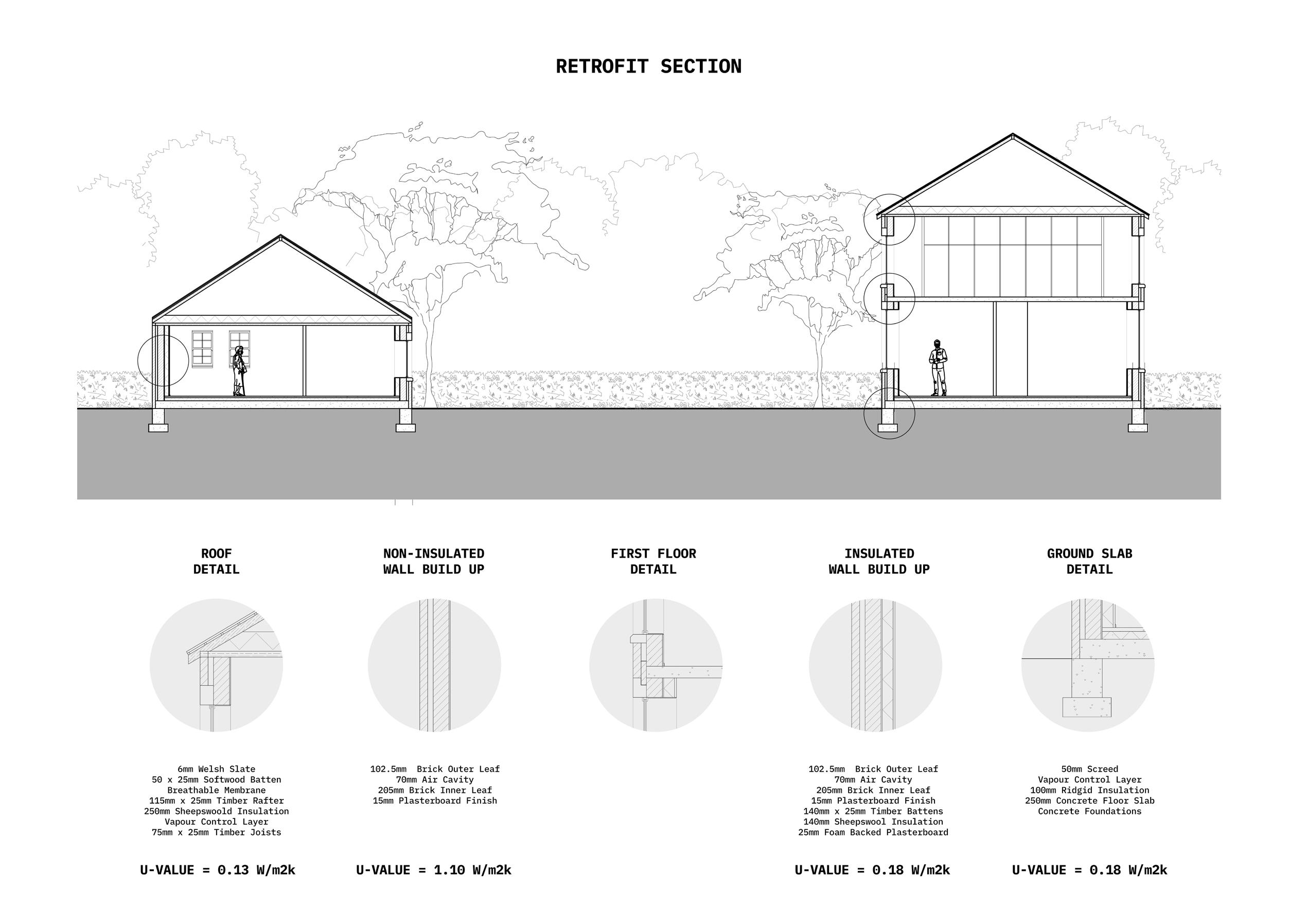

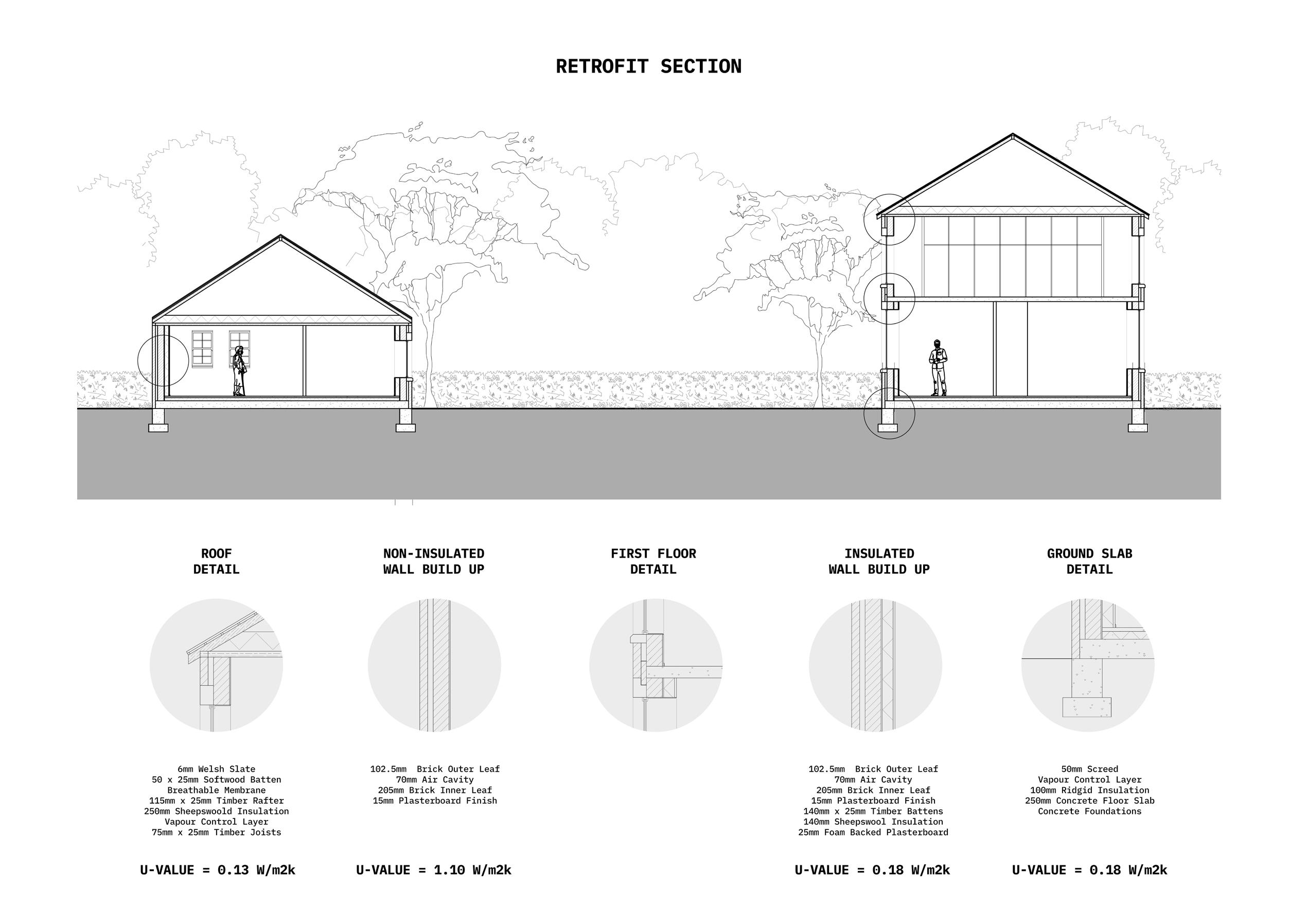

Our approach to retrofitting prioritised environmental sustainability and energy efficiency while minimizing waste. By retaining existing structures and recycling materials through careful demolition, we aimed to improve operational energy with the lowest embodied carbon during construction. In implementing these principles, we opted for a cold roof design with sheep's wool insulation, chosen for its sustainable sourcing, excellent insulation properties, and low embodied carbon. For the walls, we decided on internal insulation to maintain ventilation and moisture regulation, balancing thermal performance with the preservation of the building's character. Additionally, insulating above the slab and below the screed allowed for underfloor heating, offering a more efficient heating solution and potential energy savings. This holistic approach reflected our commitment to creating a more sustainable and energy-efficient building environment.

The improvments to the layout and material build up of the officers mess dramatically improved the energy use of the building. The building now falls well under the UK SAP Benchmark with an energy use intensity score of 23.

The building still remains heating dominated however the amount of energy needed to heat the building has dropped from 34708 kWh/yr to 6983 kWh/yr. This is thanks to a reduction in heat loss in the building through the walls, roof and floor.

Passive solar gain plays a crucial role in our design, significantly enhancing heat gains and reducing the need for artificial lighting. The incorporation of rooflights in the village hall and a mezzanine level in the gym has notably increased the influx of direct sunlight into the building, marking a substantial improvement in natural light utilization.

The retrofit integrated several sustainability measures aimed at improving the building’s performance and environmental impact. By capping and filling chimneys, moisture-related issues are mitigated, and energy efficiency is enhanced by preventing downdrafts and reducing heating needs. Introducing sun pipes in lieu of skylights not only maximizes natural light but also reduces energy consumption. Retrofitting the lobby with insulation serves to bolster thermal comfort and energy efficiency, while rainwater harvesting initiatives promote sustainable water management practices. Additionally, upgrading windows to triple glazing not only decreases heat loss and noise transmission but also contributes to overall comfort and efficiency. Collectively, these measures demonstrate a comprehensive approach to creating a more sustainable and eco-friendly building environment.

Measures such as cold roof insulation, internal wall insulation, and underfloor heating greatly improve the building’s energy efficiency, resulting in reduced energy consumption for heating and cooling. This approach focuses on building details and material with low embodied carbon, such as sheep’s wool insulation, while minimizing waste through careful demolition. Overall, the findings highlight how a comprehensive retrofitting approach can achieve significant improvements in both environmental sustainability and energy efficiency.

The climate and ecological crises affects the technological and environmental context of any architectural project. Theaimofthisstudyisto develop a deep understanding of an issue linked to sustainability in architecture. The research should consider a particular context (eg design studio).You may wish to discuss this with your studio course leader. The topics for the studies are subject to agreementwiththecourseorganiser.

The study requires research into the impact of our design decisions and the development of a design responsetoanexistingbuilding.Thefocuswillbeon the embodied and operational carbon across the life ofabuilding.

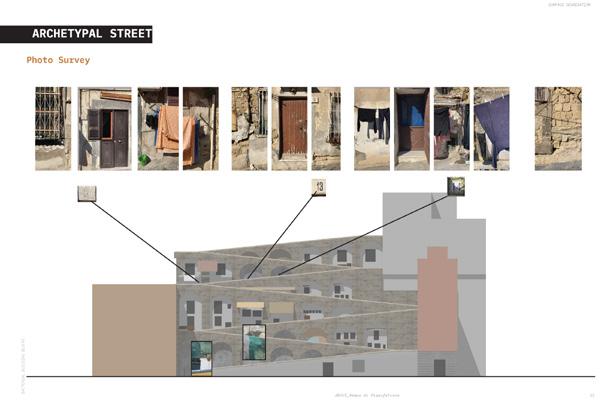

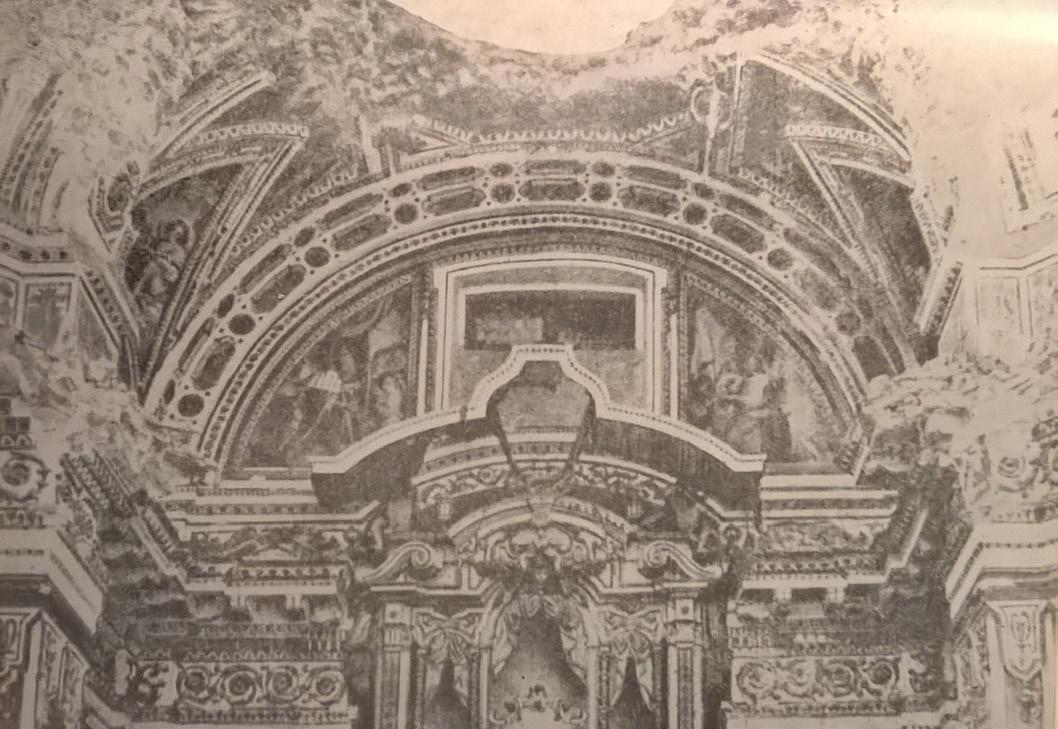

Isabelle and I had visited Naples in October 2022 and were struck by the level of degredation occuring in City.

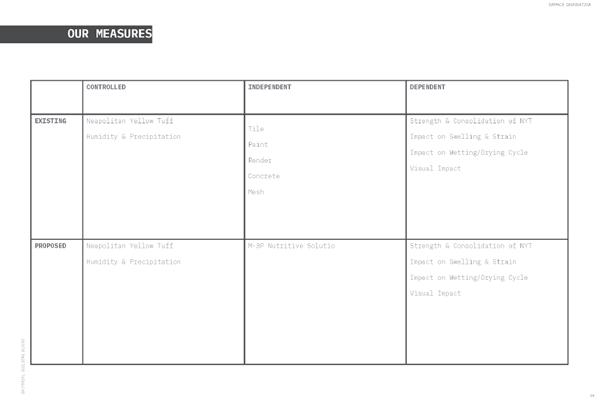

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the benefits, effects, and potential limitations of Bacterial Biomineralisation treatment as a means of consolidating and protecting Neapolitan Yellow Tuff, rendering it less susceptible to further degradation and consequently extending its lifespan. We compared the performance of bacterial biomineralization treatment on the exterior surface of NYT architecture to other more established –although notably ineffective – intuitive approaches to consolidating the stone already practiced in the city of Naples to assess its viability.

The decision to prioritise the consolidation and preservation of existing Neapolitan Yellow Tuff (NYT) over advocating for the demolition and subsequent reconstruction of sections within Naples was underscored by the remarkable carbon-capturing capabilities intrinsic to NYT.

NYT’s porous composition facilitated the absorption and sequestration of carbon and various pollutants. Airborne contaminants, alongside those suspended in water vapour, could effectively permeate the stone and become entrapped within its pores. Given the widespread utilization of NYT throughout the urban landscape, this characteristic yielded notable benefits, notably in the mitigation of local air pollution and its consequential impacts on public health. Moreover, on a broader scale, it contributed to the global imperative of combating climate change by reducing carbon emissions.

The deliberate choice to preserve NYT serves as a strategic endeavour, aligning with sustainable urban development principles. By using existing natural resources and maximizing their environmental benefits, Naples sets a precedent for responsible urban planning practices. This approach not only addresses immediate environmental concerns but also fosters a more resilient and environmentally conscious urban fabric.

“There are a good range of case studies in the appendix. It would be good to see them better integrated into the study.”

A2

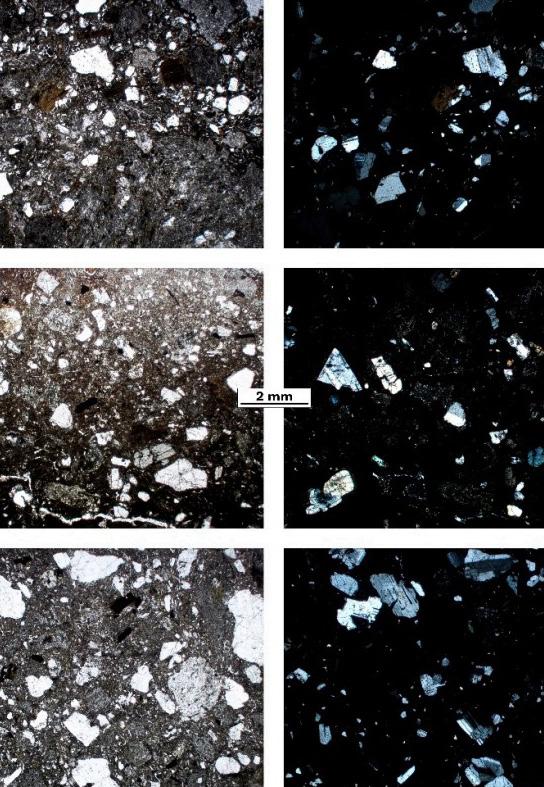

This capability is evidenced via petrographic studies on volcanic tuff which show deposits of carbon and other heavy metal particles at the surface and deeper within the inner layers of the sample.

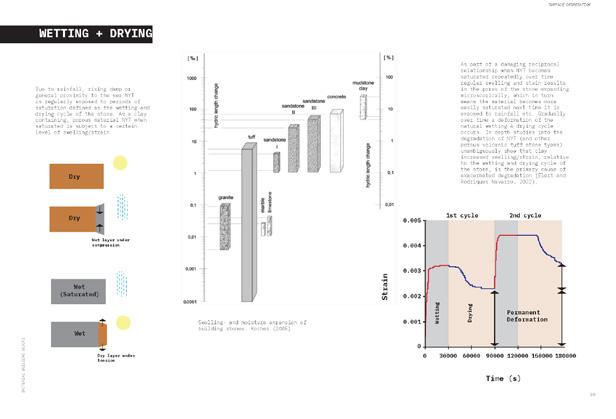

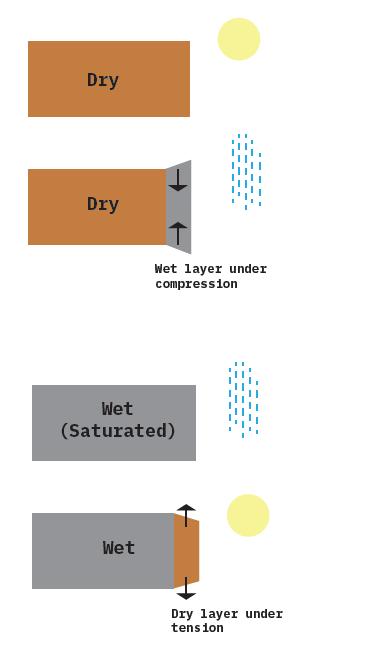

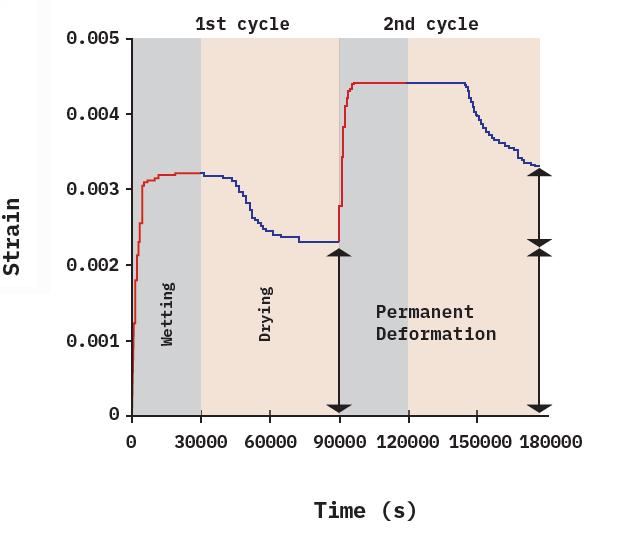

Due to rainfall, rising damp or general proximity to the sea NYT is regularly exposed to periods of saturation defined as the wetting and drying cycle of the stone. As a clay containing, porous material NYT when saturated is subject to a certain level of swelling/strain.

As part of a damaging reciprocal relationship when NYT becomes saturated repeatedly over time regular swelling and stain results in the pores of the stone expanding microscopically, which in turn means the material becomes more easily saturated next time it is exposed to rainfall etc. Gradually over time a deformation of the natural wetting & drying cycle occurs. In depth studies into the degradation of NYT (and other porous volcanic tuff stone types) unambiguously show that clay increased swelling/ strain, relative to the wetting and drying cycle of the stone, is the primary cause of exacerbated degradation.

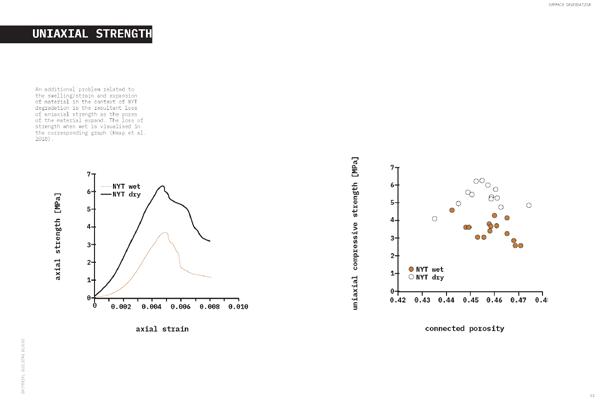

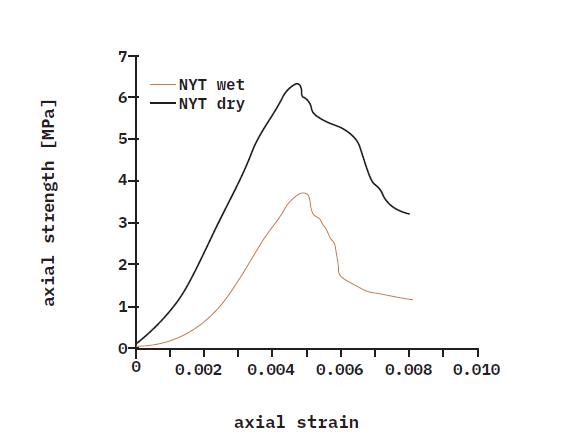

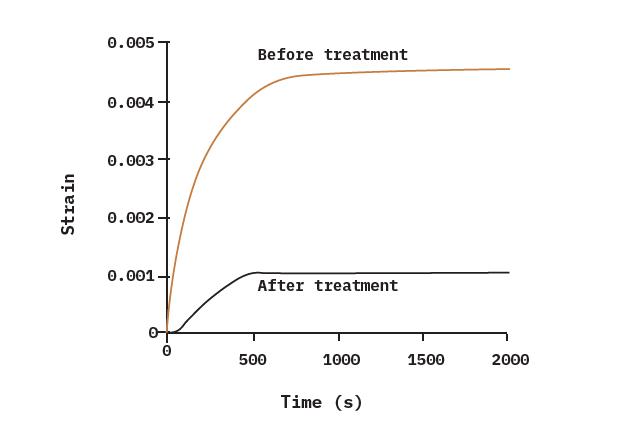

An additional problem related to the swelling/strain and expansion of material in the context of NYT degradation is the resultant loss of uniaxial strength as the pores of the material expand. The loss of strength when wet is visualised in the corresponding graph.

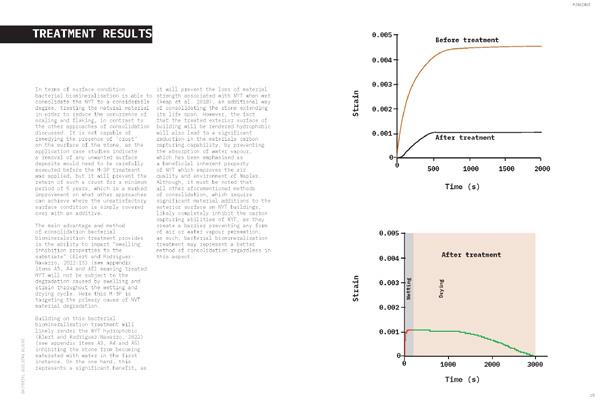

Compared to the other methods for consolidating NTY previously discussed in this study we proposed that bacterial biomineralisation could offer noninvasive alternative, which would outperform traditional methods of consolidation, in terms of strengthening the exterior surface of the stone, reducing swelling factor and improving hydrophobic properties, with the benefit of not altering the appearance of the Neapolitan architecture so intrinsic to the city. That if applied to the buildings of Naples the treatment would delay the process of decay and prevent any subsequent intervention for a minimum of 5 years, resulting in the reduction of observed decay and necessity for continual construction activity in the city

In terms of surface condition, bacterial biomineralization consolidated the NYT to a considerable extent, aiming to reduce scaling and flaking, unlike other discussed consolidation methods. It couldn’t address surface ‘crust’ presence directly; case studies indicated the need for careful removal of unwanted deposits before M-3P treatment application. However, it prevented crust recurrence for at least 5 years, surpassing other methods that merely covered unsatisfactory surface conditions.

The primary advantage of bacterial biomineralization treatment was imparting “swelling inhibition properties to the substrate,” addressing NYT degradation caused by wetting and drying cycles. This treatment targeted the core cause of NYT material deterioration.

Furthermore, extending bacterial biomineralization treatment could render NYT hydrophobic, inhibiting water saturation initially. While this prevents material strength loss associated with wet NYT, it also reduces the stone’s carbon-capturing capability by preventing water vapor absorption. However, other consolidation methods, involving significant material additions to NYT exteriors, likely completely inhibit NYT’s carbon-capturing abilities by creating a barrier against air or water vapor permeation.

[2022]

[Tutors]

Dr Chris French Michael Lewis[Contributions]

Olivia McMahon [OM]

Liam Findlay [LF]

[Course Synopsis]

In Architectural Design Studio C, the focus will be on navigating between the practical concerns of urban materiality and the speculative potential of architectural design. The studio will alternate between abstract and concrete approaches, aiming to create a space for both creative exploration and practical engagement with the city of Naples. This will involve two main phases: Move 1 where students will develop a studiolo within their studio environment, detached from Naples but in dialogue with its realities, for research and creative work; and Move 2, where students will propose an Observatory within a specific site in Naples, bridging the gap between gathered data and the conceptual space of the studiolo. Through these processes, students will grapple with Naples’ climate, structures, geology, and morphology, exploring various perspectives and methodologies to inform their architectural interventions.

[Learning Objectives]

LO1

The ability to develop and act upon a productive conceptual framework both individually and in teams for an architectural project or proposition, based on a critical analysis of relevant issues.

GC 1.3, 2.3, 3.3 // GA 2.1

LO2

The ability to develop an architectural spatial and material language that is carefully considered at an experiential level and that is in clear dialogue with conceptual and contextual concerns.

GC 1.1, 1.3, 2.3, 5.1, 5.3 // GA 2.1

LO3

A critical understanding of the effects of, and the development of skills in using, differing forms of representation (e.g. verbal, drawing, modelling, photography, film, computer and workshop techniques), especially in relation to individual and group work.

GC 1.1, 3.3 // GA 2.2

Present a selected FIGURE relevant to Naples, and an associated OBJECT or collection of objects related to that figure. The FIGURE should be an individual pertinent to Naples, either directly or indirectly. These could be historical figures, fictional figures or cultural figures... They could be made present as figures, through a portrait or photograph, or through a piece of their work (a book, a painting, an article, a film, a piece of clothing, and so on).The OBJECT could be drawn, made or found. It can be an original object, put forward to emblematise the thinking of your figure, or just an intriguing object through which to consider Naples.

Response

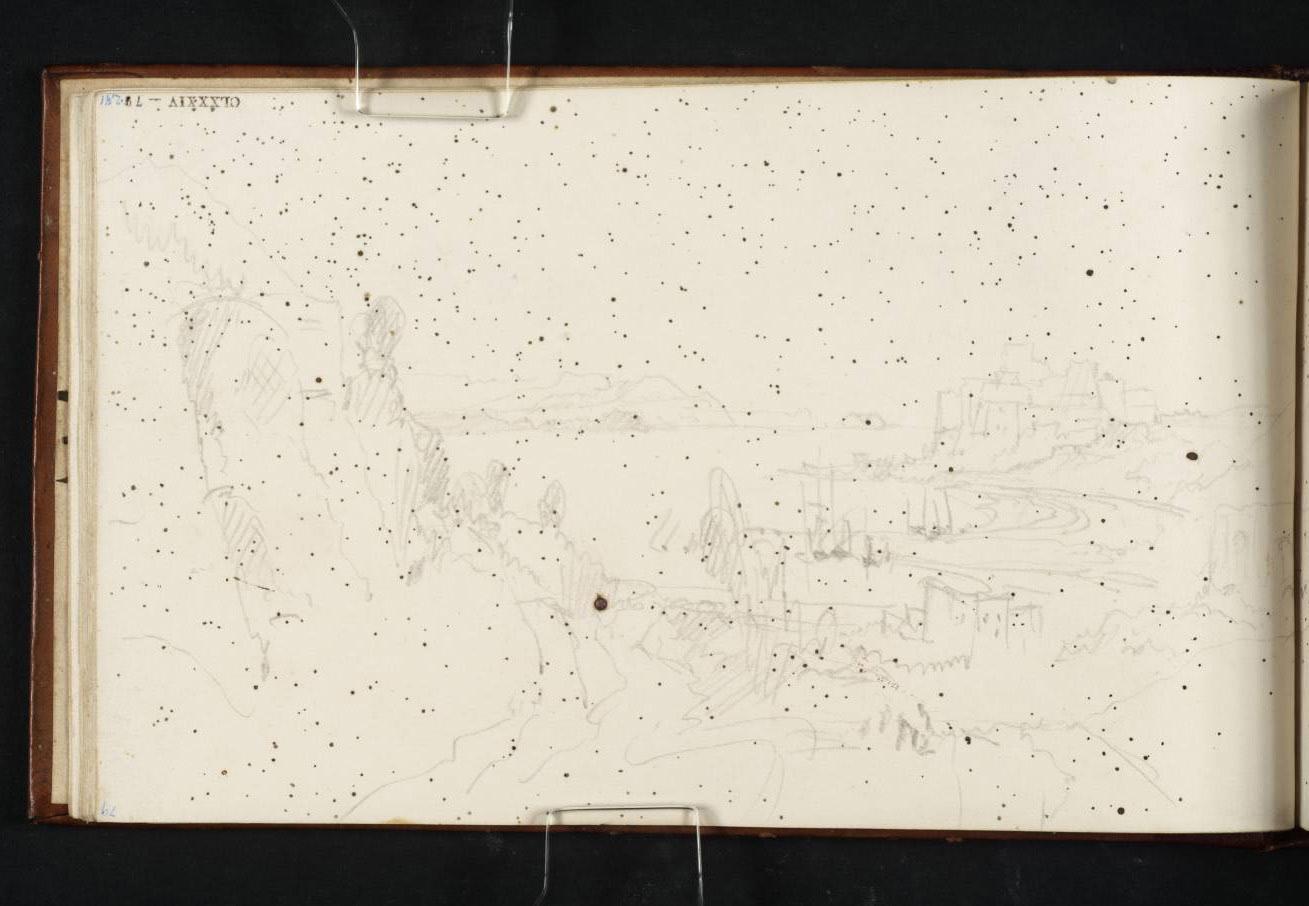

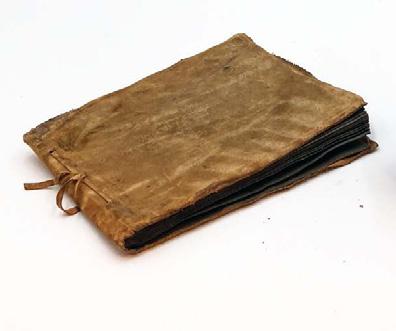

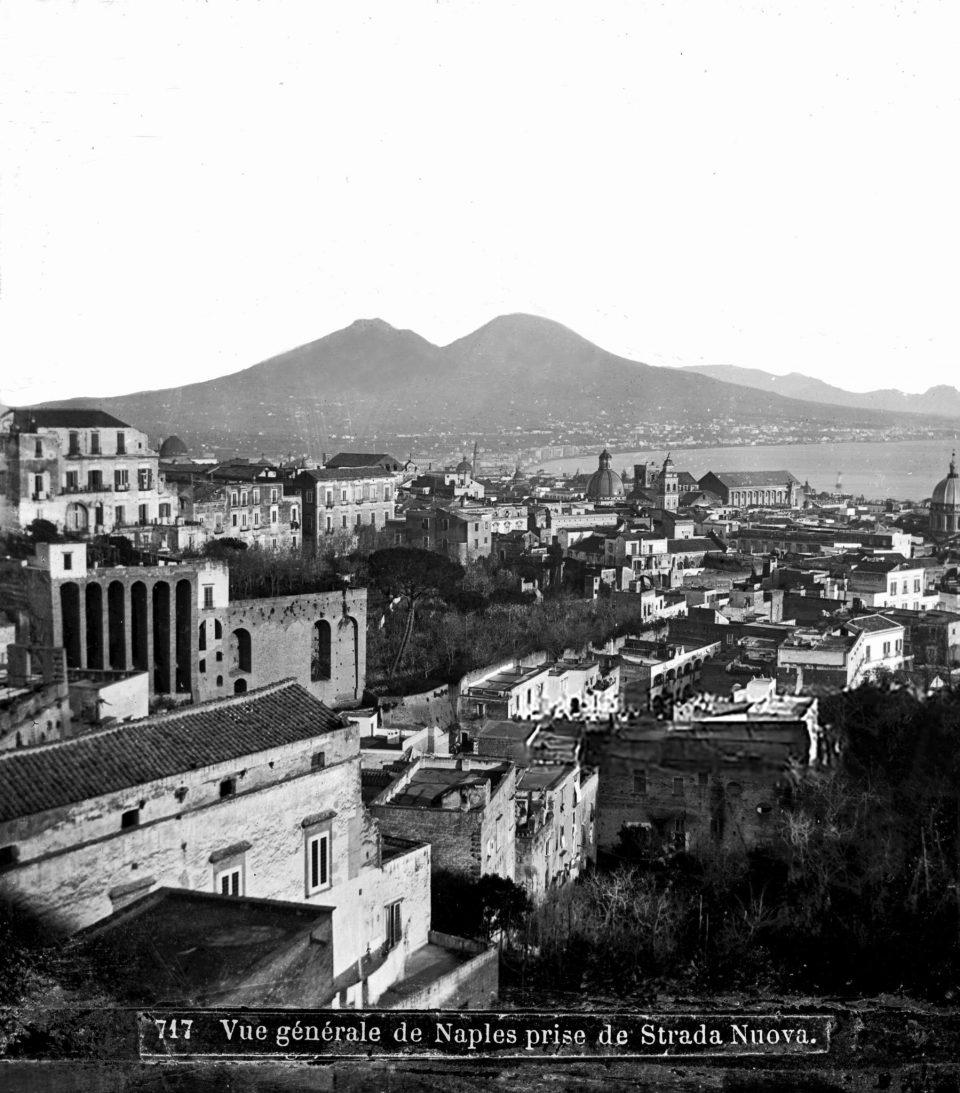

For this opening exercise I chose J.M.W Turner, the English landscape who visited Naples in 1819. Turner’s sketchbooks show that during his 1819 tour of Italy, he relied heavily on pencil point work.

For him, pencil sketches served a single purpose: to record facts and serve as a repository of topographical information.

He painted seven watercolour studies of Naples, but only a small proportion of these, if any, were done in the open air; the rest were done from memory after the pencil sketches were completed.

‘First, he receives a true impression from the place itself, and takes care to keep hold of that as his chief good ... and then he sets himself as far as possible to reproduce that impression on the mind of the spectator of his picture’

A page from his sketchbook illustrates his inquisitive nature and eagerness to register such a sublime event.

A number of scholars have followed John Gage’s suggestion that these were made by a shower of hot volcanic ash during Turner’s ascent of Vesuvius.

This triggered a fascination of my own, one concerned with registering the ground, the small details that often escape notice but hold profound significance. This initial study ultimately leads to an observatory concern with rendering one sensitive to the subtleties of weather and surface.

Developing from these initial installations, in Weeks 2 and 3 in your working groups you are to collectively re-install your objects and figures in such a way as to re-shape and re-construct the studio; we will turn the studio into a space of several studiol. Over the course of the semester these studioli will become both working spaces and tools for drawing, describing, and presenting your work and the city of Naples. This will involve the construction of specific furniture-like apparatus, low walls, desks, reading spaces, shelves, micro-architectures found, constructed, and installed, as well as the gathering of research material, drawings, and surveys. Task

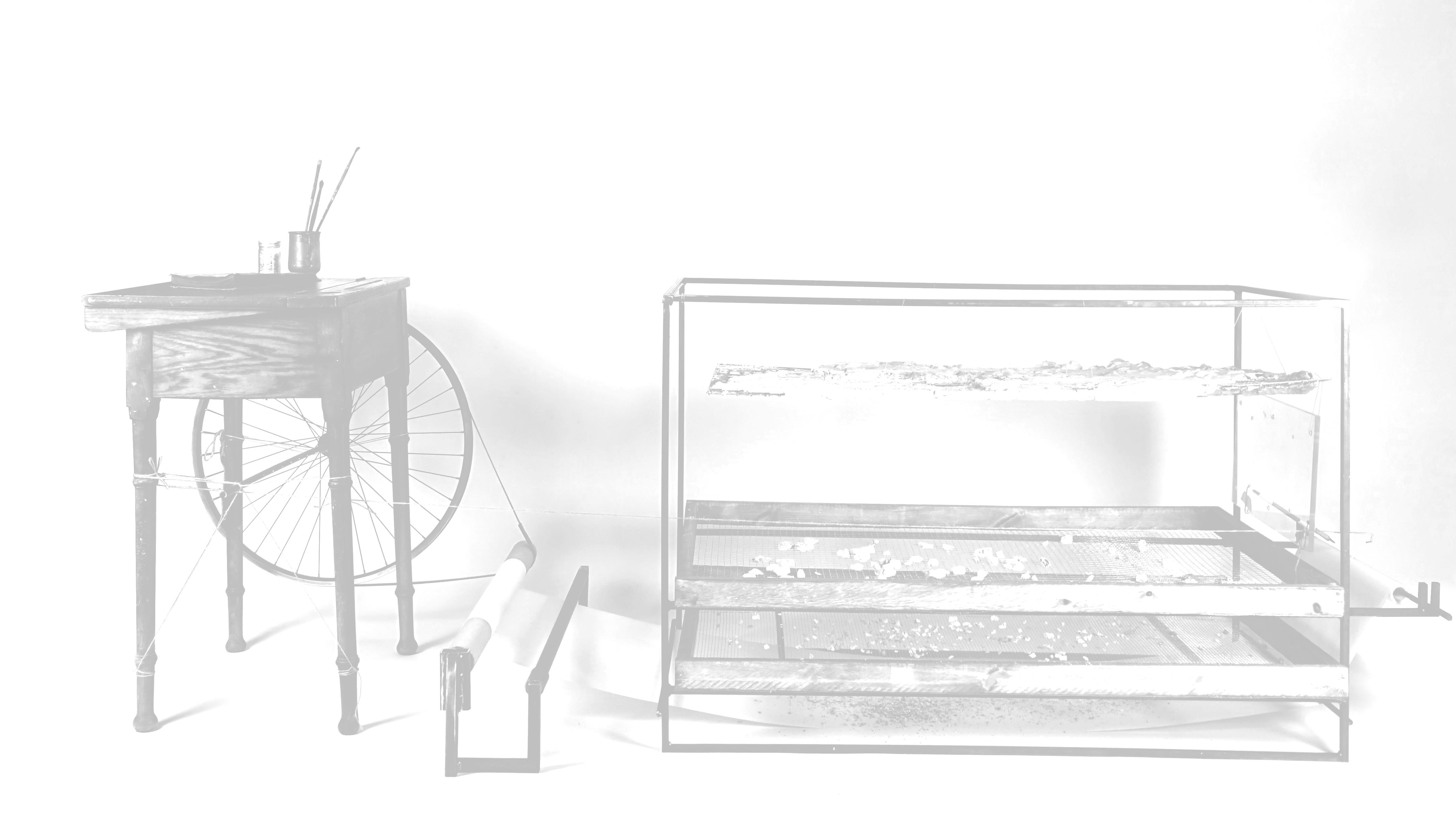

Response

The studioli is emblematic of a sort of archaeological device, where a series of layers come to represent the sequential process of making and un-making precarity. The surrogate surface, the sieves, the desk, the roll of paper and the needle formulates a language that begins to tie together the performative acts that our figures might engage in.

In order to continue the cycle of mark-making through the disruption and undoing of the surface, we propose a device that may register tremors and movement and, in turn, respond by tapping and chipping away at the surface.

The tools used to carve are stored in the same place as the deposits, within the table itself and treated with equal importance. The distinction between tools for marking and surfaces being marked are blurred, much like how the tabletop also acts as a wall to be projected on, or fragments of the “geographical paper” become imprinted on the scroll of paper below. The repetitive nature of this mark making generates a hermeneutical approach to the drawing process.

The surface created is intentionally fragile, so as to create unpredictable conditions, through mark making. It becomes a sketchbook, or a wall; a Neapolitan surface behaving geologically to describe a perplexing landscape. Drawings or workings deface themselves, becoming performative pieces, collected in trays, vials, scrolls, and stored in the desk to create an ever-evolving archive of pigment, deposit, sediment, and dust.

While in Naples you will have two central tasks: identifying and surveying a SETTING and recording a ZONE. These tasks can be completed in groups or individually (although you should never work on a site alone; ask for assistance from, and offer assistance to others where needed). Groups could be linked to your studiolo or could be formed through emerging mutual interests in the city.

Buildings “should be constructed with the smallest stones so that the walls, fully saturated with mortar made of lime and sand, will bound together for longer. For since these stones are soft and thin in consistency, they dry out the mortar absorbing the moisture. But when the amount of lime and sand is great and plentiful, the wall will not give way quickly since it contains more moisture, but is held together by these material.”

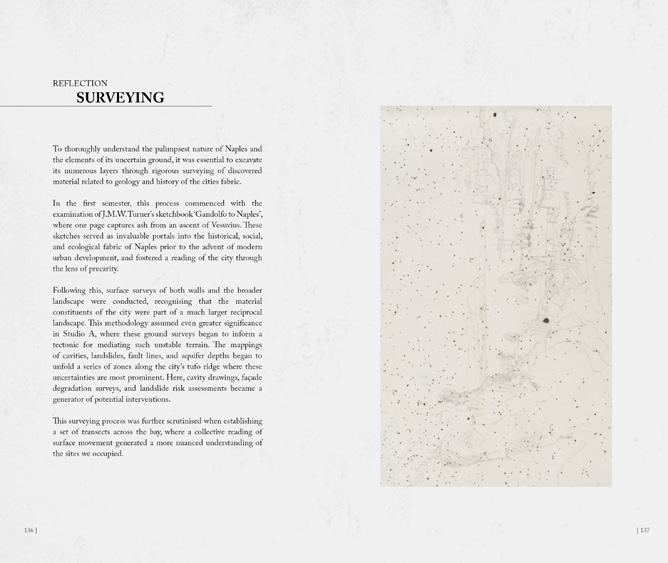

Response

Captured surfaces serve as registers of material conditions, or a “double register” as Andrew Benjamin describes, where walls and landscapes are both surfaces and surface effects. Using the concept of ‘Terroir,’ the fieldwork re-engages the theme of capturing surface effects within a larger context. In Naples, we collected mineralogical samples, building fragments, rock dust, rubbings, and photographs to construct material studies and taxonomies. This recontextualizes materiality within broader landscapes, following Jane Hutton’s ‘Reciprocal Landscapes.’ Our 1:1 material studies involved surveying degraded areas like landscapes, generating contours, and providing scale through a grid.

Parco Ventaglieri presents itself as a void in the city, a ravine of sorts that sits as a materially charged space, particularly relevant to our various material investigations. We found that it was incredibly hard to build up a picture of Naples due to the very subject we were investigating. Atmospheric effects, such as smog, dust, clouds and an undulating topography blur distinctions between surfaces, landscapes and buildings. The site, however, acts as rich backdrop in which to develop and understanding of these conditions.

Through Move 2 you are to devise, design and draw a small Observatory to be installed within your surveyed SETTING re-situating, grounding, your studiolo as an architectural project in Naples. The precise scale, programme and nature of this Observatory will be specific to your emergent theses, but it should enable the development of spatial, material strategies, and the exploration of architectural atmospheres and qualities. The working title Observatory is not intended to invoke telescopes or other viewing devices. While ‘observing’ implies ‘looking’, to observe something is to be attentive, to notice or perceive significance; this is not strictly or exclusively visual. Rather, we use the term here to echo the organisation ‘Citizens Observatory of the Commons’, an agency in Naples charged with monitoring the use of public spaces, auditing the city and its environment. Developing from the architecture of your studioli, your Observatories should develop similar, specific monitoring functions.

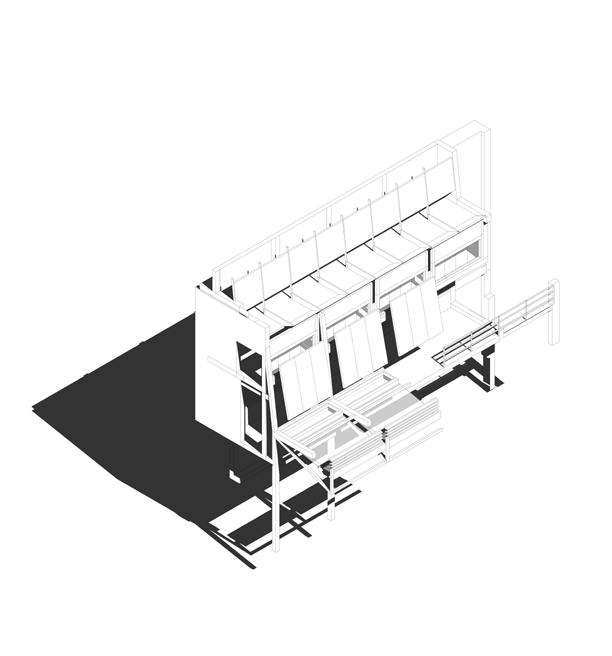

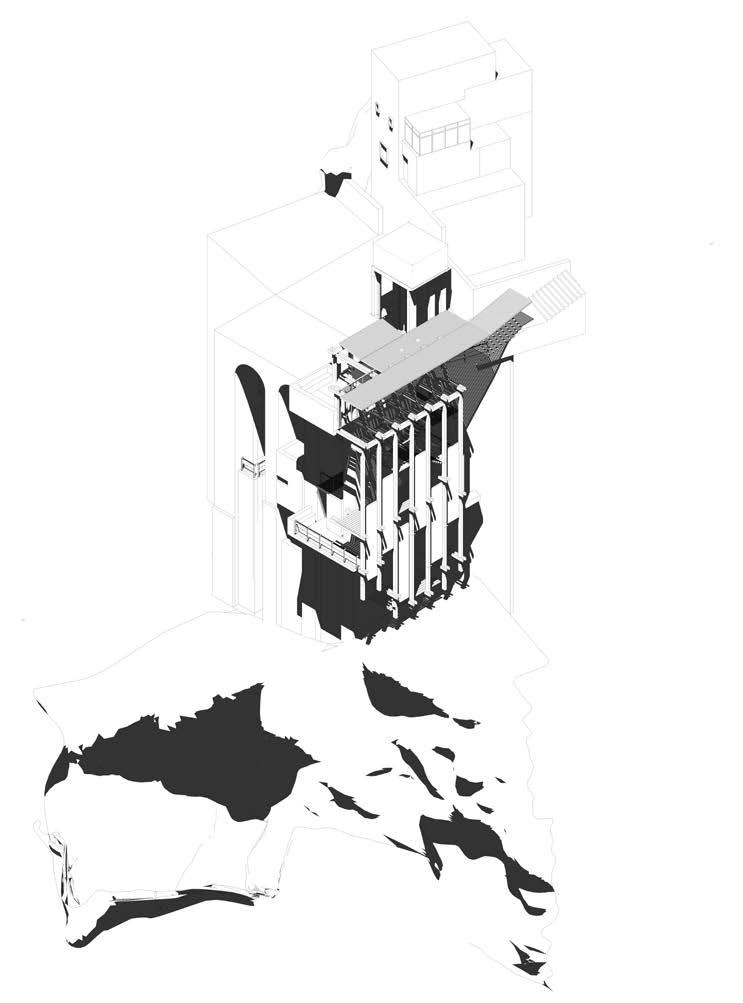

The structure serves as a meterological observatory, providing a place to measure, record and monitor atmospheric conditions. Such conditions are brough to a degree of visibility through a ‘twitching’ architecture that moves and shifts in response to the surrounding environment.

MOVE 2 // OBSERVATORIES

C

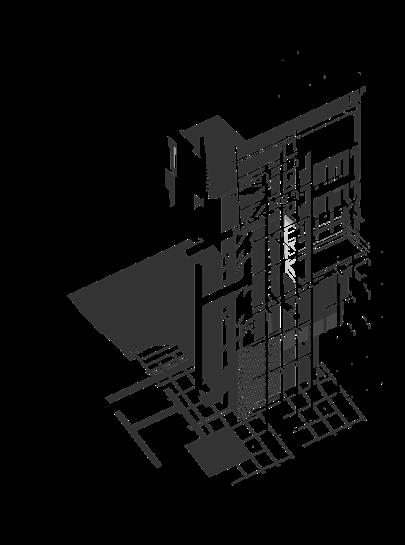

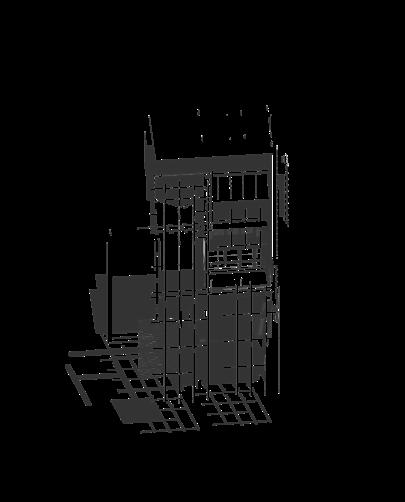

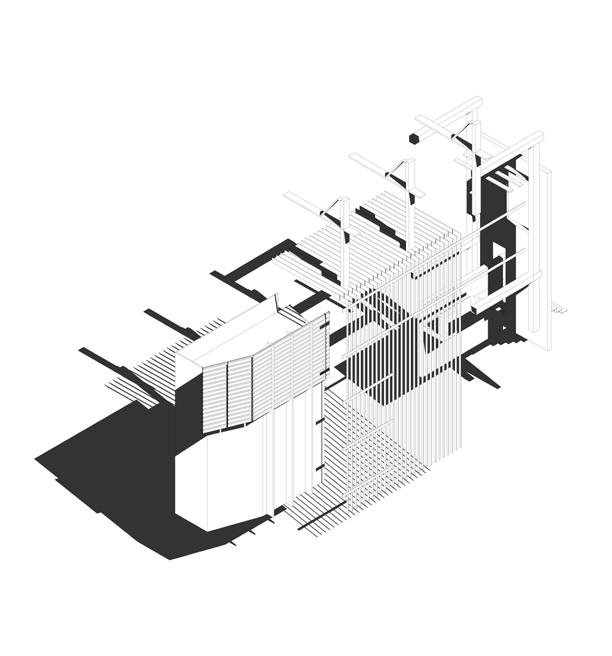

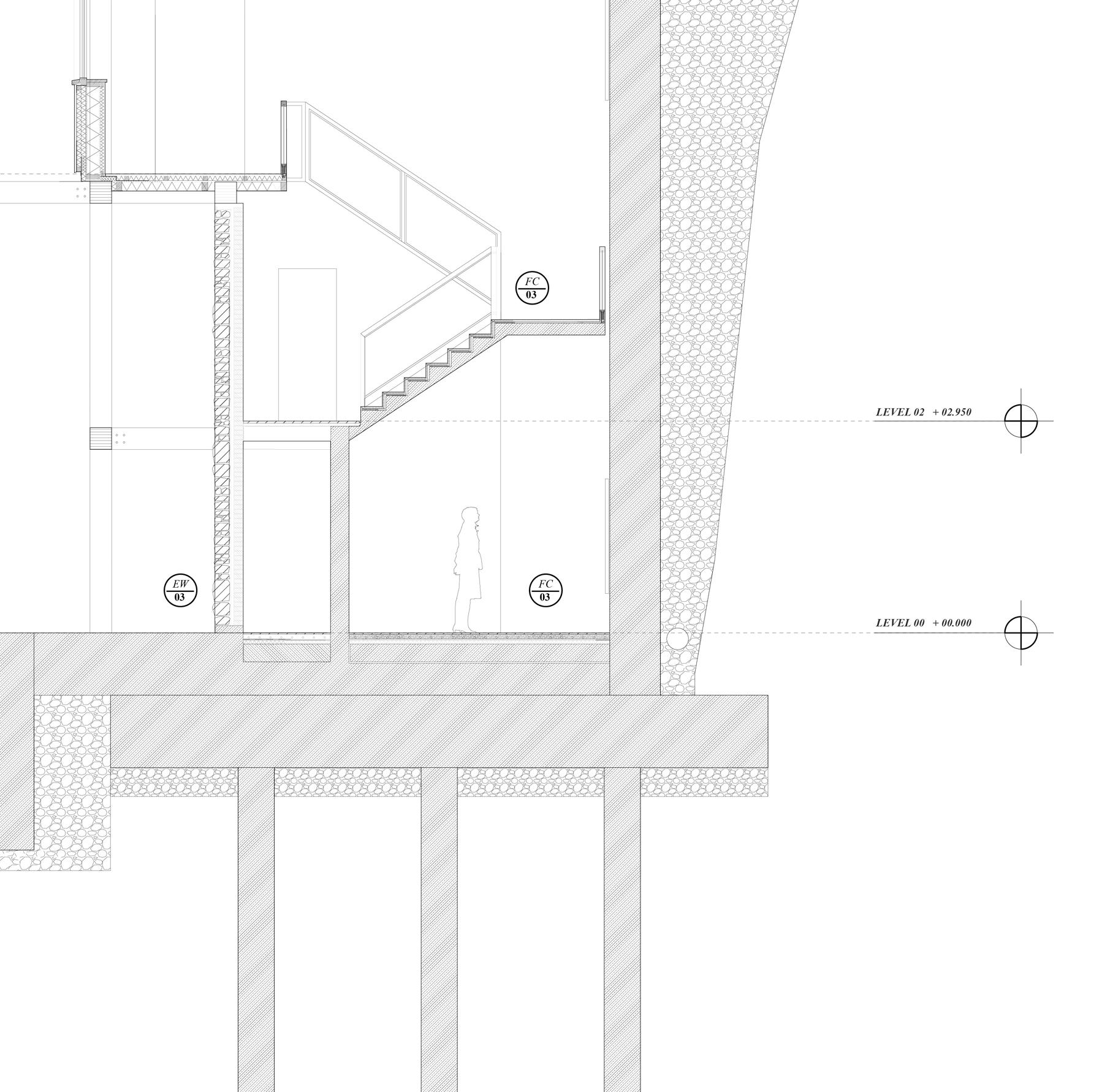

[above] perspective elevation showing the circulation and supporting framework across different levels of the observatory.

[left] perspective view of the meteorological observatory

Animated Architecture

The relationship between art and architecture is further explored through the possibility of action that distinguishes the latter. The verb-essence of architectural experience manifests through places for preparing, recording, exposing, painting, sheltering, descending and storing.

“A meaningful architectural experience is not simply a series of retinal images. The elements of architecture are not visual units, they are encounters, confrontations that interact with memory. In such memory the past is embodied in action. Rather than being contained separately somewhere in the mind or brain, it is actively an ingredient in the very bodily movements that accomplish a particular action,’”

- Edward S Casey, Remembering: A Phenomological Study, Indiana University Press, 2000,

The proposition framed the thesis well through its manifestation of atmosphere as a ‘twitchy’ architecture, shifting and moving in response to climate.

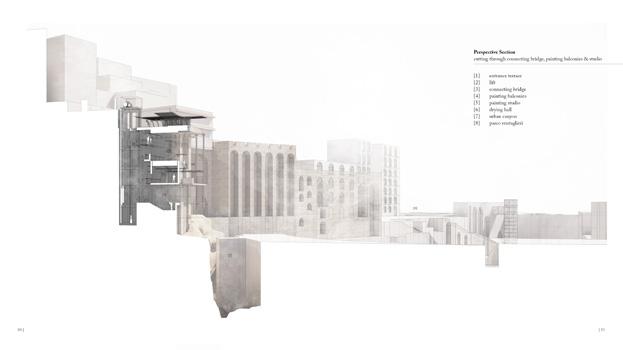

The observatory facilitates the descent through a system of lifts, stairs, and painting balconies, each providing a unique view point of the city. Traversing these levels are a set of shutters that respond to fluctuations in moisture levels. Monitored by a hygrometer discreetly nestled within the arches, these shutters twitch and shift, offering an ever-changing panorama from the external painting balconies

[above] renders of connecting bridge and painting studio [left] isometric of observatory

Some of the drawings (renders in the pamphlet and rendered iso in the portfolio) were incredibly effective at communicating the atmosphere and material qualities of the scheme. Where work is needed is in the orthographic drawings. The heavy shadows dominated, making the organisation difficult to read and obliterating the finer tectonic components.

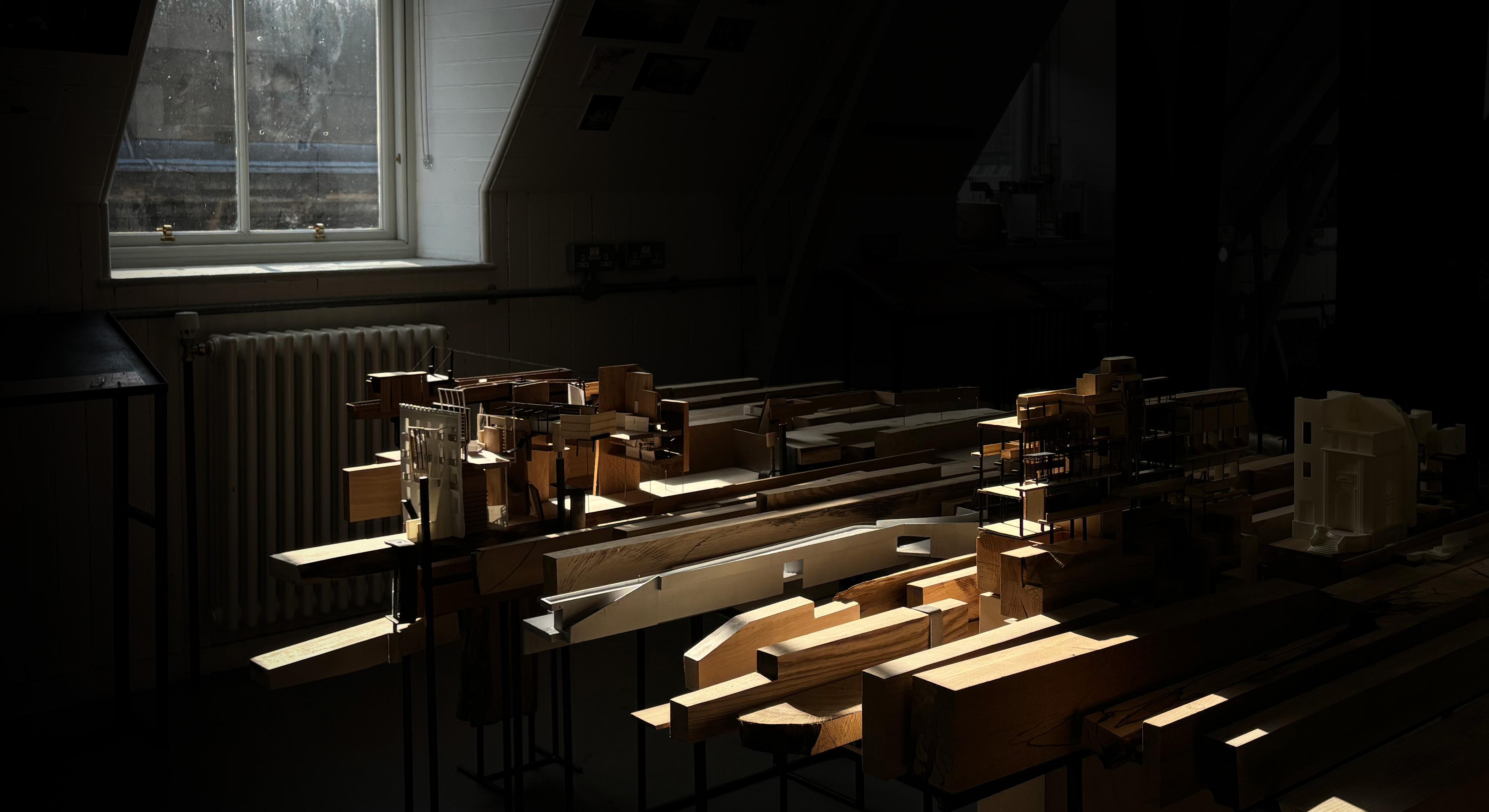

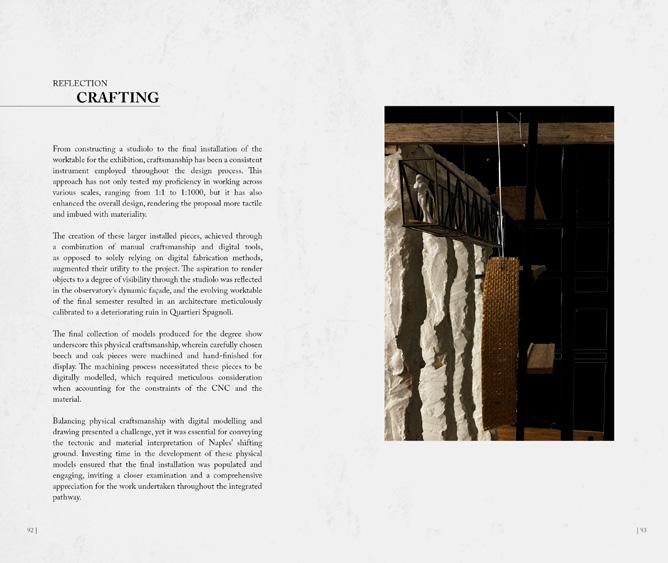

Model-making was a key driver during this studio, from the studiolo through to 1:50 spatial explorations. The act of making invited a curious approach to the materials being used and tested the sensibility of the architectural proposal. Every model served to deepen my understanding of the project, refine or redefine its conceptual underpinnings, and reduced the reliance on renders to articulate the atmospheric and spatial qualities of the proposal.

Throughout the semester, I continued to establish a sophisticated conceptual framework, drawing inspiration from the studiolo and conducting thorough research on Naples’ environmental conditions. This foundational work provided a solid basis for the development of my architectural proposition, particularly the design of the Observatory.

While I am pleased with the overall outcome of my studio work, there are areas where I recognise the need for improvement. For instance, I have noted feedback on the compression of material in my pamphlet, lack of development drawings and the clarity of my orthographic drawings. These insights have highlighted opportunities for refinement in my presentation techniques and technical skills moving forward.

[2023]

ARCH11070

[Tutors]

Dr Chris French

Michael Lewis

[Contributions]

Olivia McMahon [OM]

Liam Findlay [LF]

[Course Synopsis]

In Architectural Design Studio D gives students the opportunity to develop or initiate a major design project, and to bring students explorative and creative processes into dialogue with technological and environmental decision making. This will involve two main phases: Move 3, where students identify a material and sites within Naples in which the material manifests; and Move 4 where students explore how architecture might foster the production of these conditions, might break down borders between sites or spaces, might intervene in the composition of the air or nullify or amplify certain sounds to unsettle fixed atmospheres. These pieces should describe an ambitious architectural, landscape and urban proposition for Naples, one that introduces programmatic, social, cultural, and environmental concerns through a re-framing of the Neapolitan city landscape and its reciprocities.

[Learning Objectives]

LO1

The ability to develop and act upon a productive conceptual framework both individually and in teams for an architectural project or proposition, based on a critical analysis of relevant issues.

GC 1.3, 2.3, 3.3, 7.2, 7.3 // GA 2.1

LO2

The ability to develop an architectural spatial and material language that is carefully considered at an experiential level and that is in clear dialogue with conceptual and contextual concerns.

GC 1.1, 1.3, 2.3, 5.1, 5.3 // GA 2.1

LO3

The ability to investigate, appraise and develop clear strategies for technological and environmental decisions in an architectural design project.

GC 1.2, 8.1, 8.3, 9.1, 9.2 // GA 2.3

LO4

A critical understanding of the effects of, and the development of skills in using, differing forms of representation (e.g. verbal, drawing, modelling, photography, film, computer and workshop techniques), especially in relation to individual and group work.

GC 1.1, 3.3 // GA 2.2

Task

Through Move 3: Neapolitan Ground and GROUNDING(S) you are to identify a material, and sites within Naples in which that material is manifest, as both the focus of production and the object of consumption or use (Hutton’s second approach).Describe these sites through drawing/ma ing, depict their limits, and qualities, how material is found there, where, and how it is processed, and where it is subsequently employed (first approach). Describethematerialitself,itsstructural,formal,and technical properties.Describe its displacement,how it traverses the city or enters other sites and cycles of production(thirdapproach).

Response

Vitruvius description of the construction of a wall folds together material, constructional and environmental concerns. “Since the stones used are soft and porous,” he writes, “they are apt to suck the moisture out of the mortar... But when there is abundance of lime and sand, the wall, containing more moisture, will not soon lose its strength, for they will hold it together.”With a sustained interest inNeapolitansurfacesandthroughthescaleimplied by ‘Neapolitan Ground’, we explored the broader ecological territory and material reciprocities that underpin this notional wall. It explores how the constituents of the wall—the tufo,lime and sand— belong to broader, an often problematic, conditions andecologies.

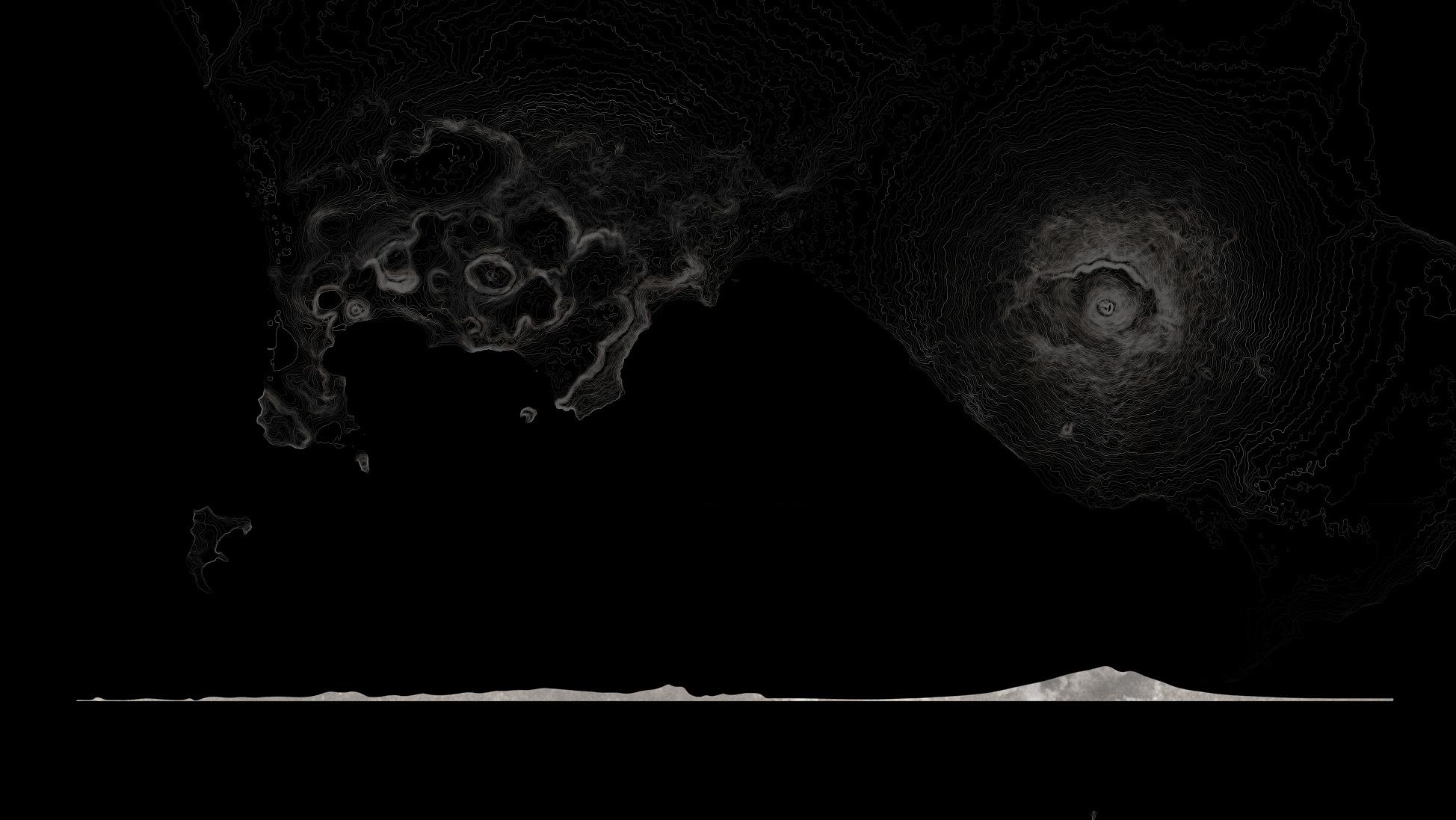

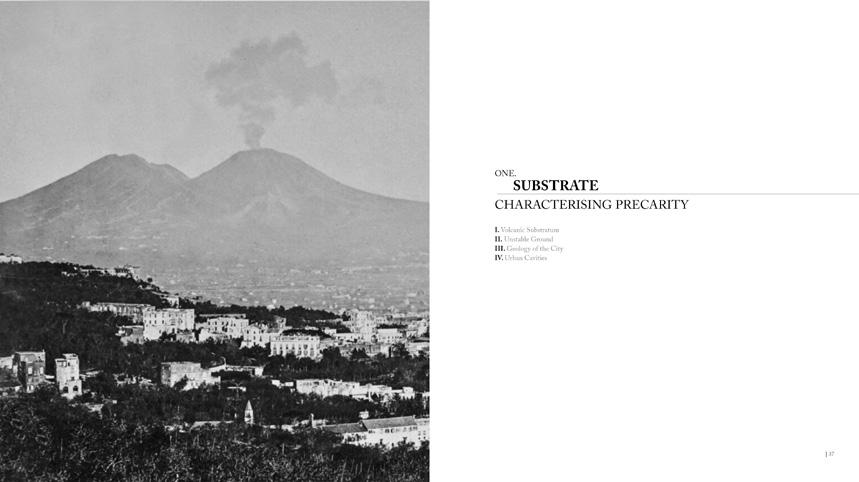

The geological formation of the volcanic bedrock, combined with the area’s rugged terrain, seismic events, bradyseism, and other natural occurrences, contribute to an inherently unstable ground condition for the city’s foundation, independent of any human alterations. This instability is exacerbated by the susceptibility of the volcanic bedrock to erosion by water.

[Campi Flegrei]

[Campi Flegrei]

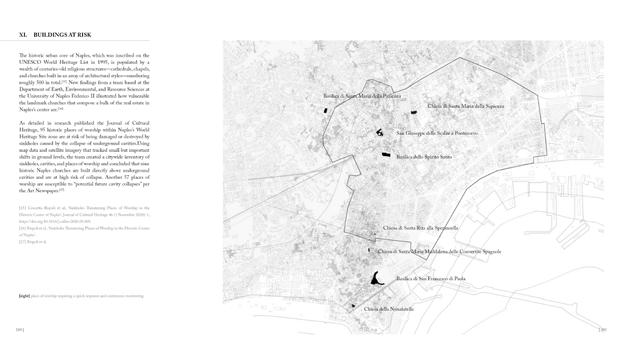

The subterranean strata of Naples serve as a geological chronicle of the city, preserving records of past volcanic activities and eruptions from neighbouring regions. The layered bedrock, in conjunction with the overlying soil strata, is composed of several compacted pyroclastic flows, leading to the unique varieties of tuff found in the area. Despite the common belief that a city founded on rock would be inherently stable, Naples exhibits a different scenario.

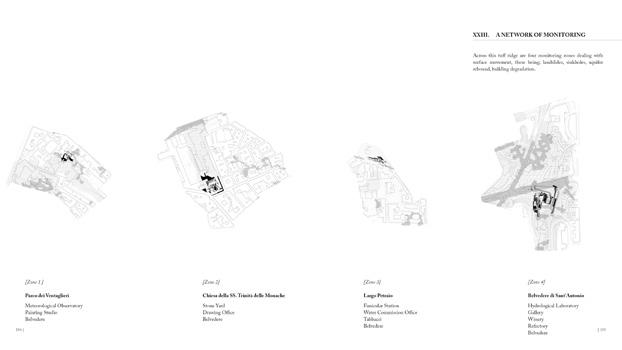

A pronounced tuff ridge cuts through the city, marking a shift in the city’s geological base, from thick pyroclastic sediments on the ridge’s crest to friable pyroclastic deposits at its base. This disparity in sediment structure leads to varying erosion rates. Districts such as Montecalvario, Quartieri Spagnoli, Vomero, and Posillipo are located on this less stable foundation, rendering them prone to erosion due to water infiltration and runoff along the ridge.

For many centuries, the inhabitants of Naples favoured the extraction of tuff from subterranean locations for construction purposes, leading to the formation of a complex network of cavities beneath the city, as opposed to using embankments or openair quarries which would have necessitated significant material transportation.

The techniques used for extraction led to the creation of large voids within the rocky substratum, typically hidden from sight at ground level. Tuff, once extracted from the quarries, was often used near its source, resulting in a direct relationship between the city’s growth and the increase in these underground cavities. Areas such as Montecalvario, Posillipo, and the Quartieri Spagnoli (Spanish Quarters) experienced extensive tuff extraction, thereby housing the greatest density of subterranean voids. This increased occurrence of underground cavities makes these districts especially prone to subsidence in the overlying subsoil.

Saharan advections in Naples can significantly increase PM10 loads on the ground, leading to a decline in air quality. PM10 refers to particulate matter with a diameter of 10 micrometers or less, which can penetrate deeply into the respiratory system and cause respiratory and cardiovascular problems. A recent study has shown these unfavourable meteorological conditions caused by desert dust, including reduced rainfall and relative humidity and increased temperature, can hinder pollutant dispersion.

This is particularly problematic in a city like Naples, with high pollution levels and a topography that can exacerbate the effects of these meteorological factors. The mountains surrounding the city can trap pollutants and prevent them from dispersing, while high temperatures and low humidity can cause pollutants to accumulate in the air. This is further worsened by the narrow but tall ‘urban street canyons’ that impede and or trap the movement of air.

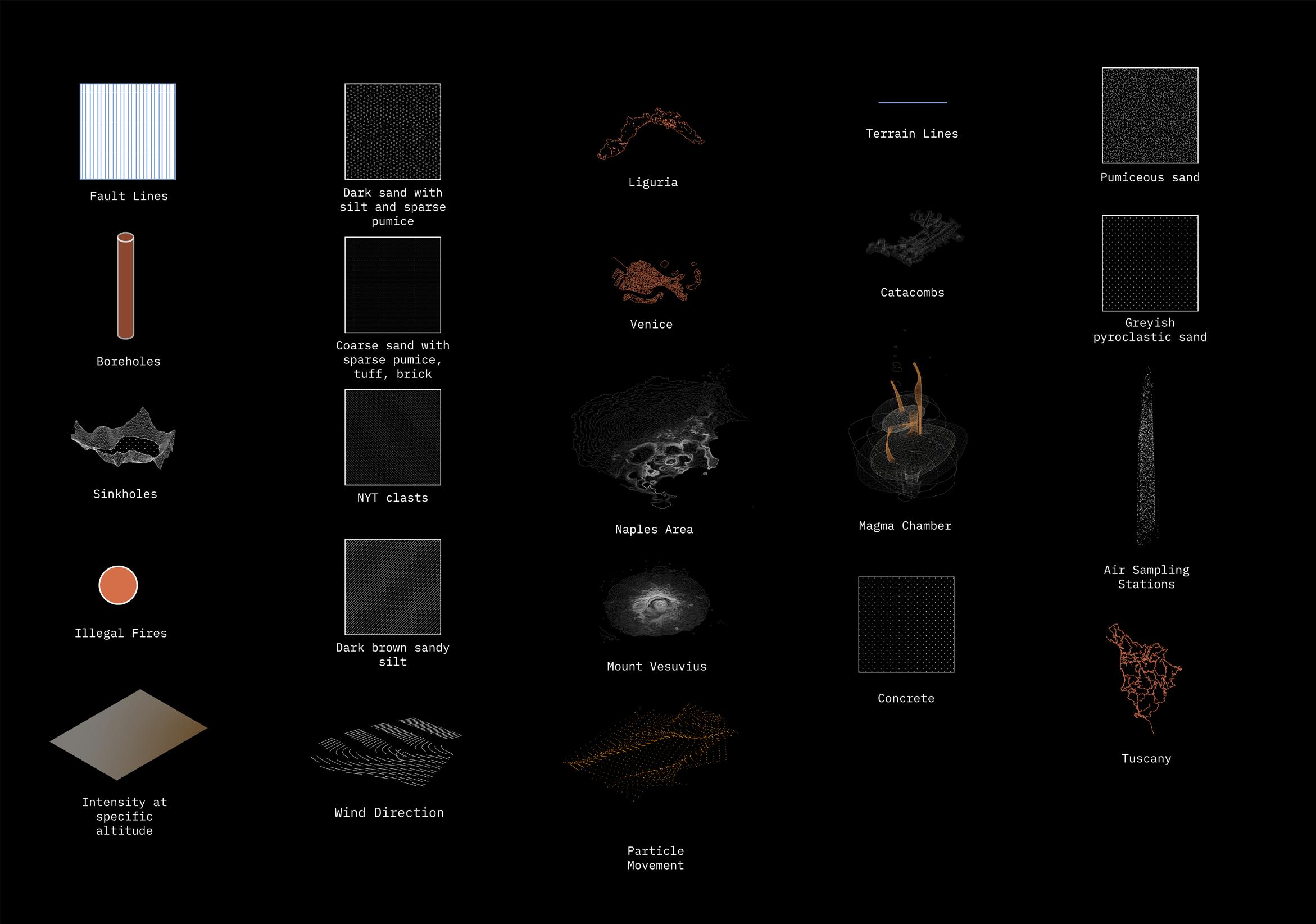

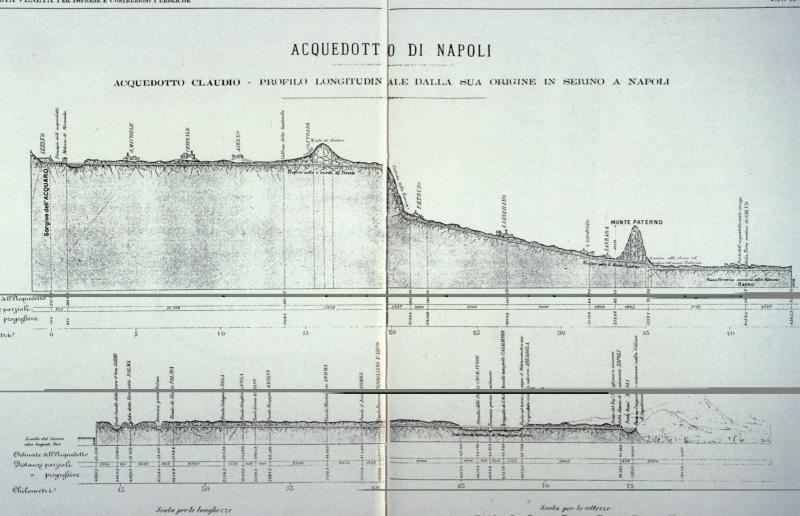

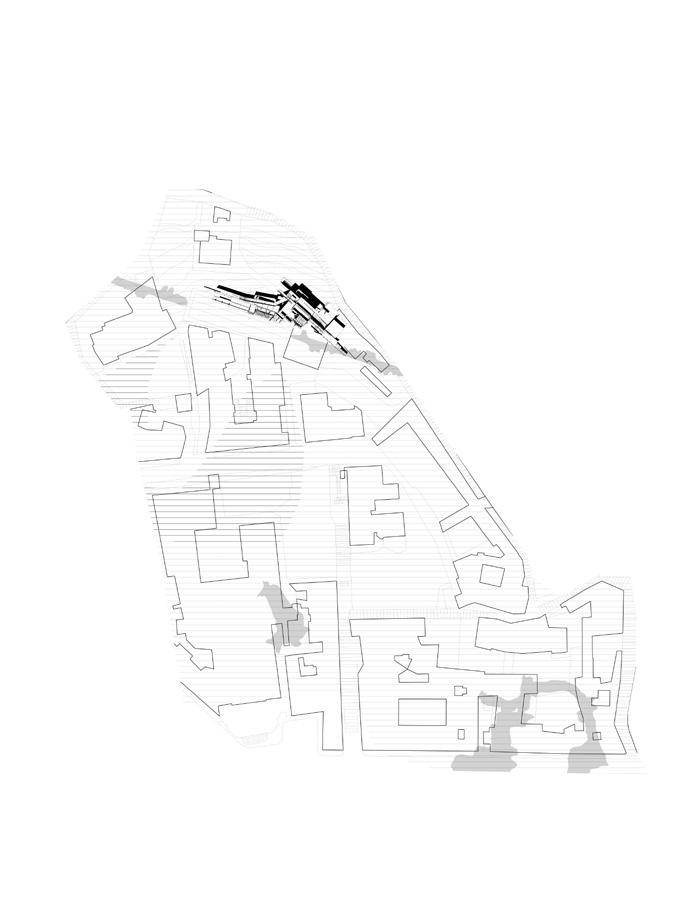

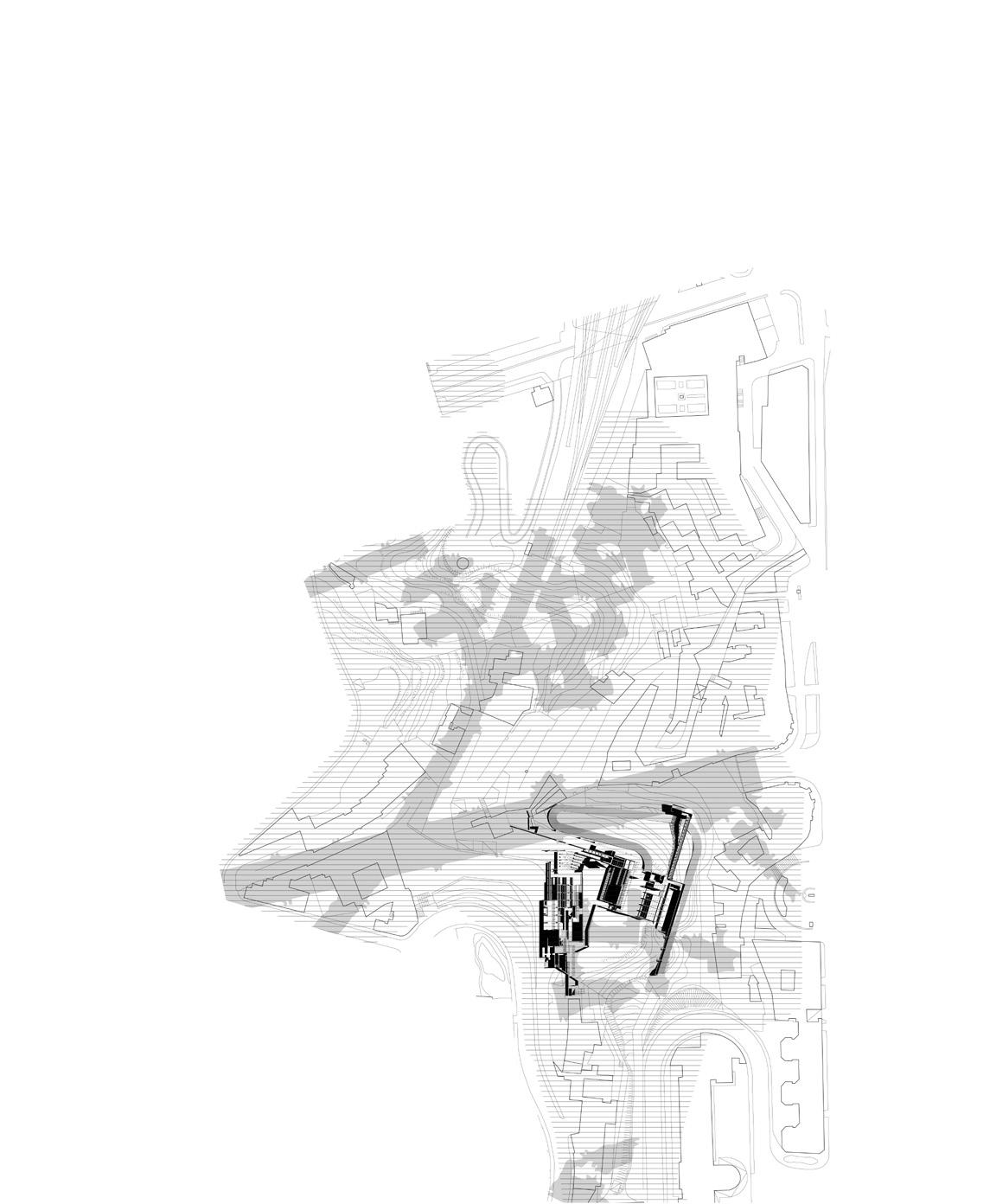

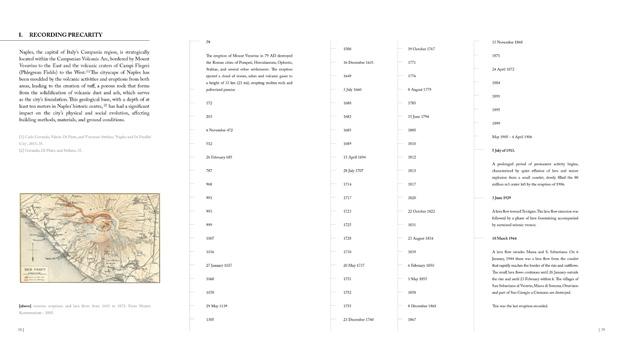

Our investigations from the beginning of the semester have been concerned with capturing material incompatibilities, or what we have chosen to call Faults. Faults from a geological standpoint but also a social, cultural and ecological one. The drawing is concerned with exploring existing material reciprocities and interrelations within Naples, tying together networks of quarries, sinkholes, landfills and atmospheric particulates with networks of corruption and contamination.

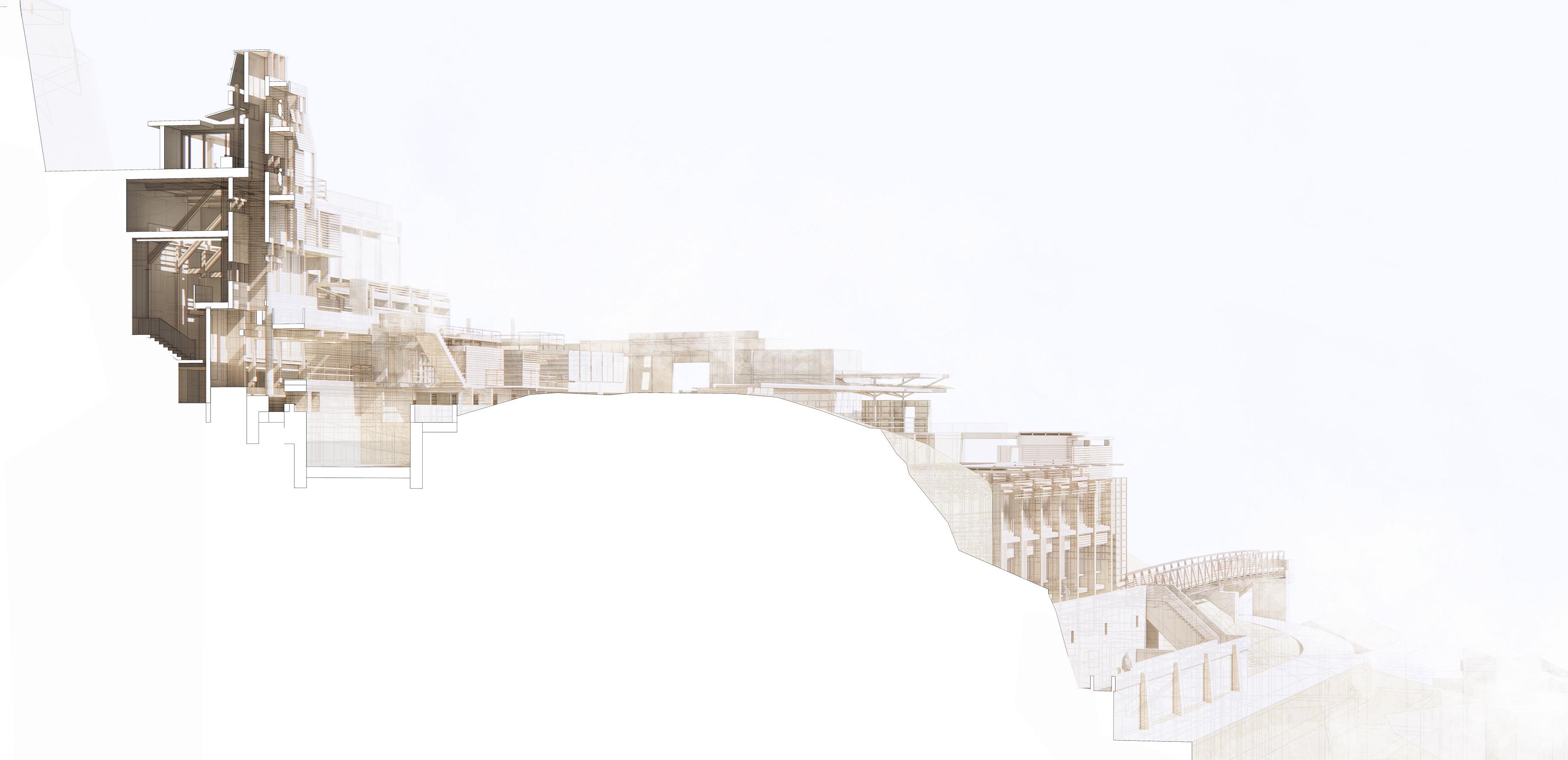

These performative interrelations are represented through a deep section - a ground cycle drawing that considers Naples as a core sample, acknowledging the complex ecological, social and biogeochemical processes taking place above, below and within the urban ground of Naples.

The bottom portion of the drawing can be read as geological ground and the top portion as a sort of aerosolized ground. The drawing allows us to relate phenomena occurring below ground to that above ground, depicting the entangled nature of Neapolitan surface.

Through Move 4: ZONE Constructions you are to explore how architecture might foster the production of these conditions, might break down borders between sites or spaces, might intervene in the composition of the air or nullify or amplify certain sounds to unsettle fixed atmospheres. You are to develop a complex, architectural/landscape strategy for a territory within Naples, ambitious and yet carefully focused on the concerns of your emergent thesis. This should be given spatial and material form, through models and drawings.

Informed by readings of “Il Sottosuolo di Napoli” (The Subsoil of Naples), our on-going investigation of the Neapolitan ground can be re-contextualised, where Neapolitan ground can now be divided into six distinct geotechnical zones.

These zones relate to the varied geotechnical conditions and strata of different kinds of soils and rock that presuppose Neapolitan ground, enabling us to identify particular urban areas of interest. A series of drawings that relate to soil contamination, air contamination, geological conditions, cavities and fault lines help to delaminate the investigations already completed as part of the Neapolitan ground drawing, enabling for a deeper understanding of ground conditions in Naples.

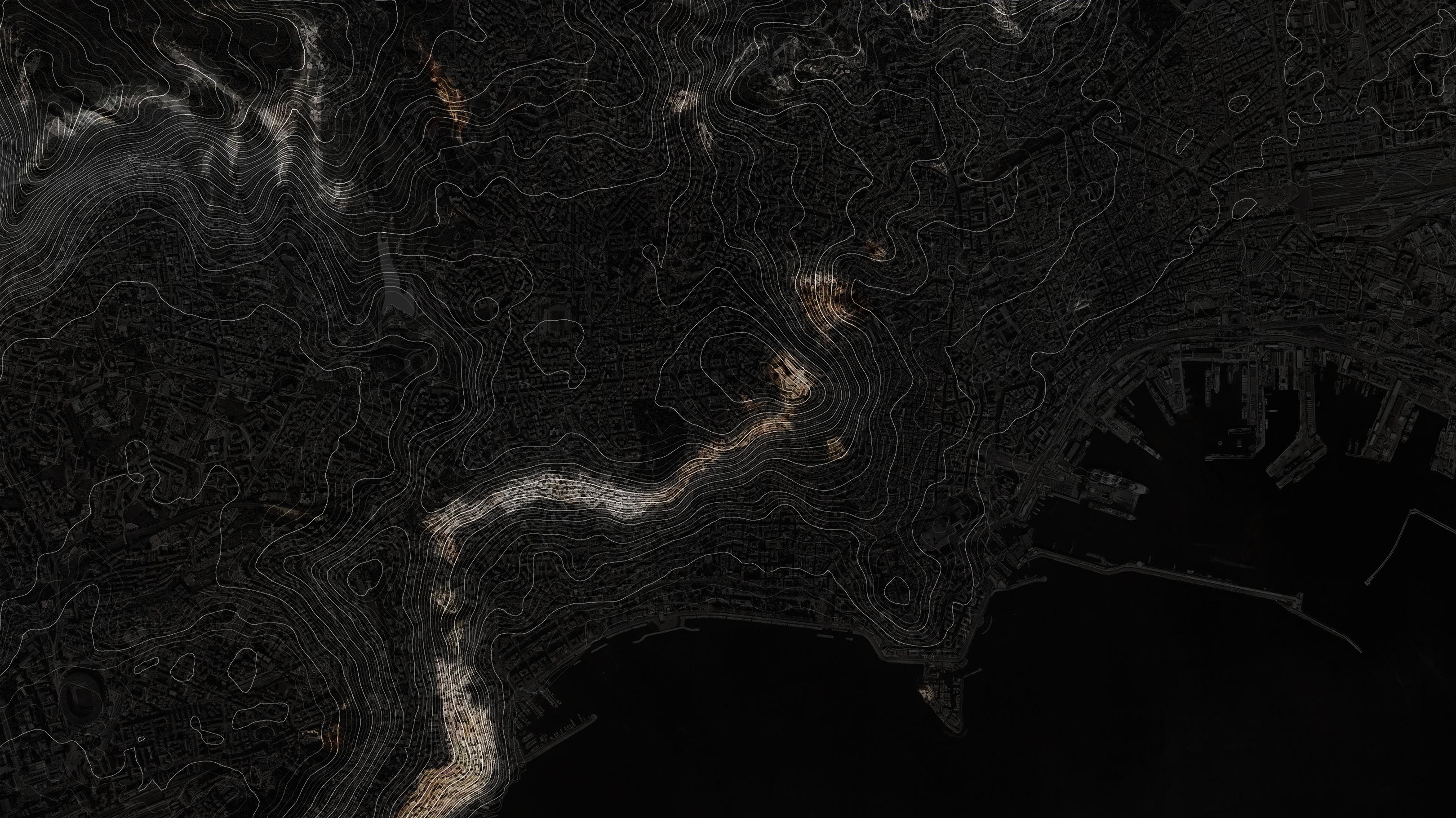

[above ] superimposed mapping of tuff with the cities topography

Re-constructing Ground

Our explorations have centred around how to best represent the various ground conditions that our zones embody.

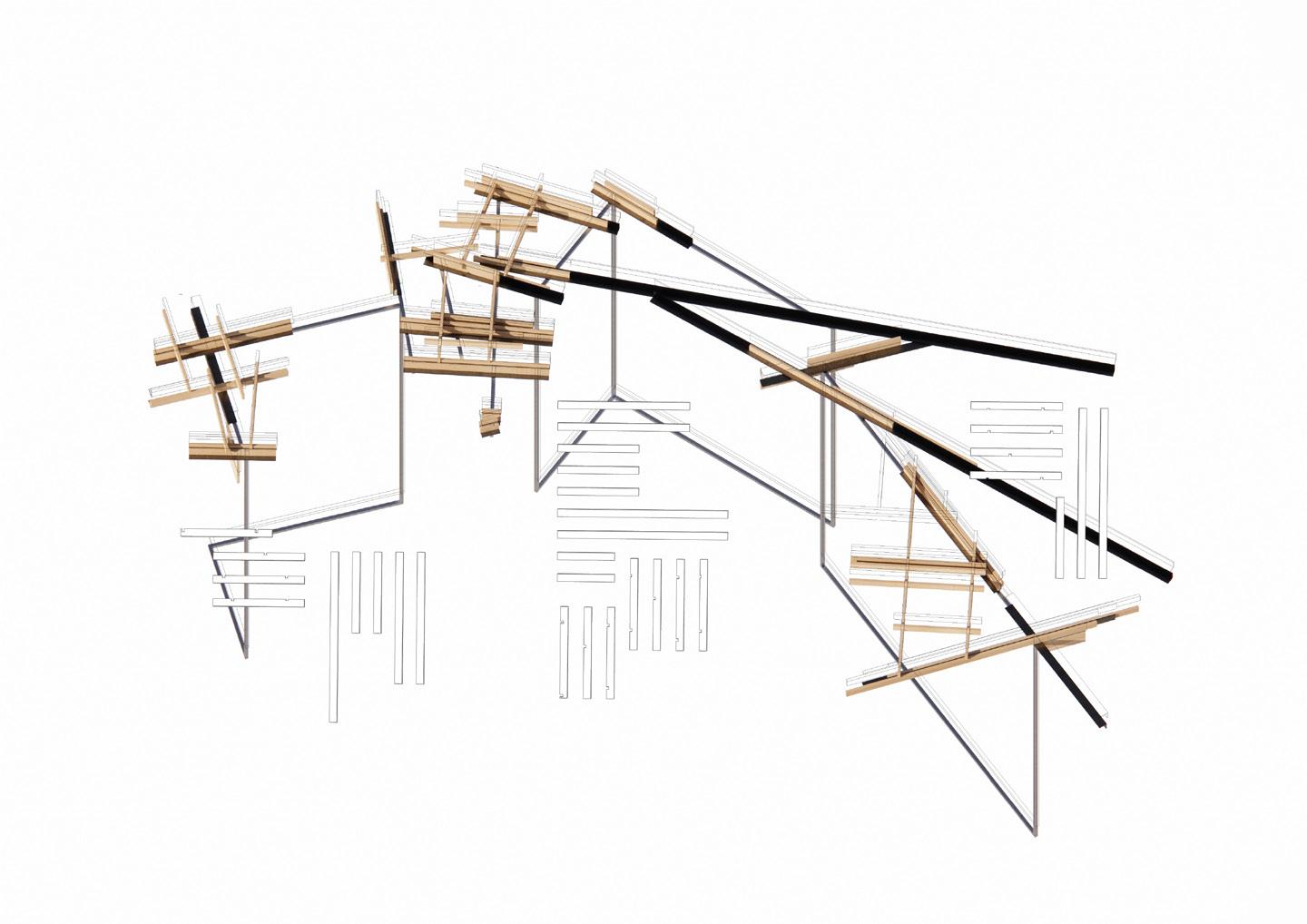

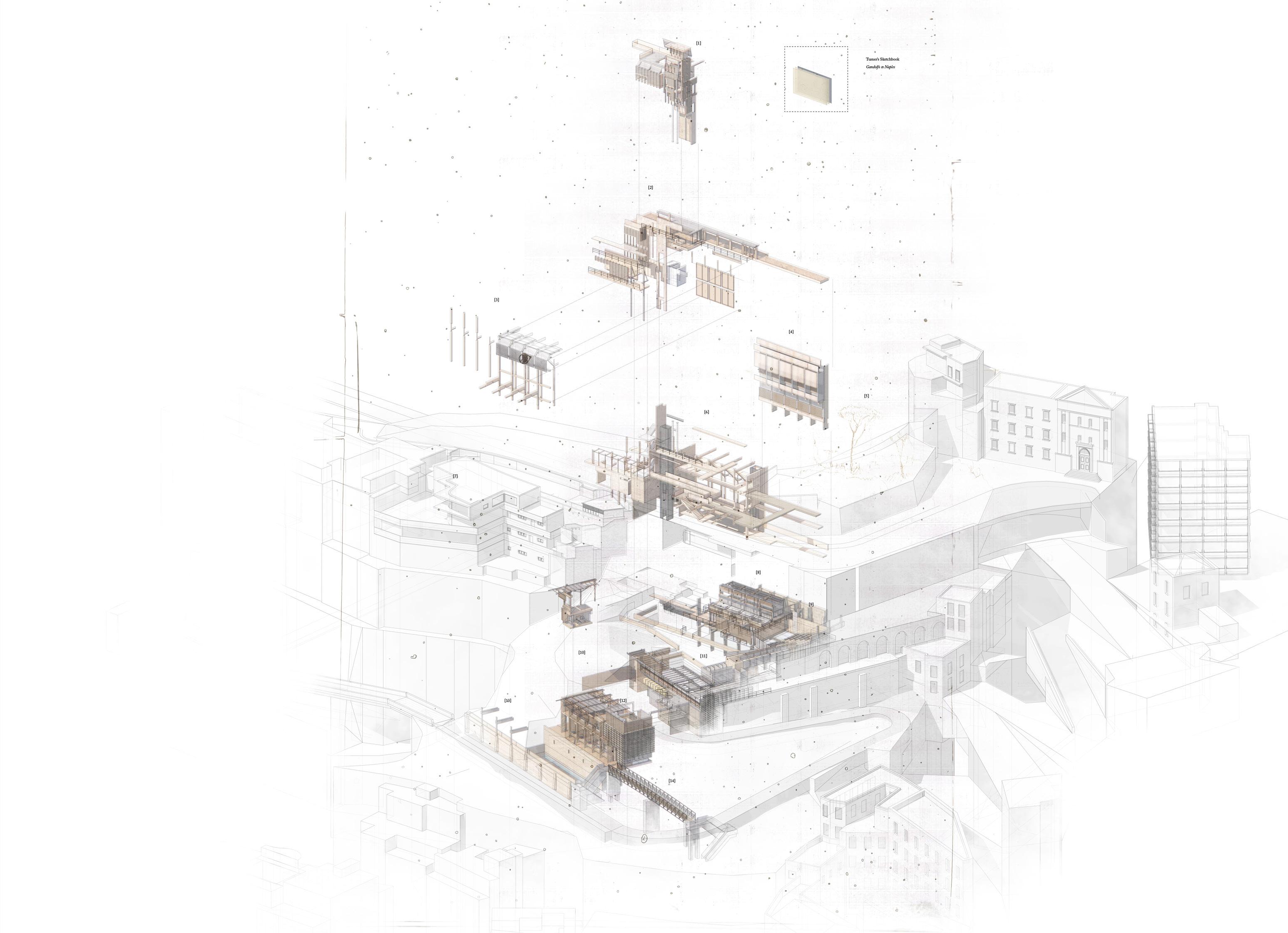

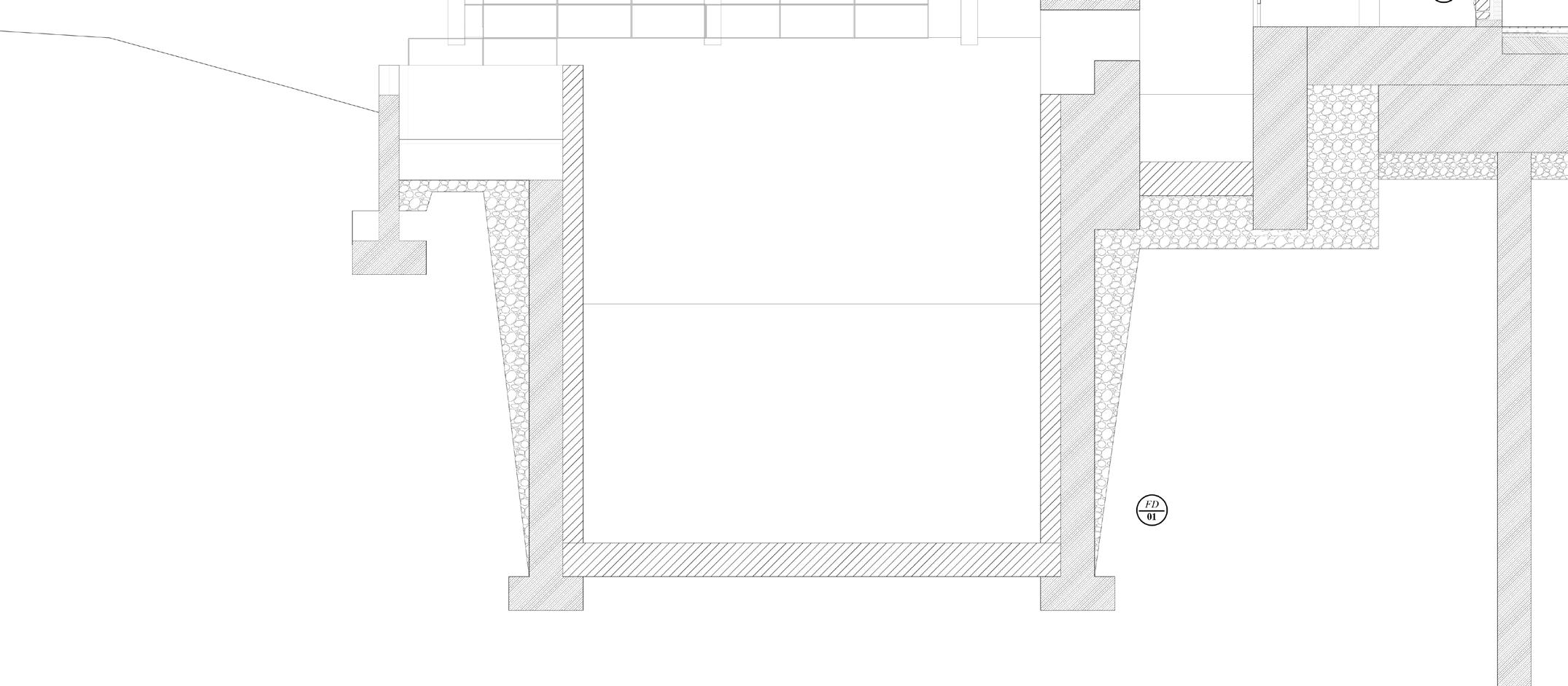

Initial explorations involve the articulation of two sets of complementary construction systems – timber laths and a metal framework – to represent the intersections between fault lines and subterranean networks. In addition to this, we also began to explore how we may create footings or support systems for this framework through prototyping boreholes at a 1:1 scale, which would be represented through rammed earth columns.

These boreholes would be emblematic of the varied geological conditions within each zone. A series of detail drawings come to represent possible earth construction footing systems that may be used within the synthetic field construction.

Taking our understandings of the geotechnical zones further, our investigations of Neapolitan ground can now be re-contextualized by activating it as a synthetic field. The term ‘synthetic’ here refers to the depiction of ground as both established through natural and man-made forces, but also as a field that may be re-configured and re-worked through our proposals. The synthetic field construction thus emblematises the various ground conditions of the zones that our proposals are sited on, whilst also performing as a field in which to situate and archive our work.

Alongside the development of this Neapolitan Ground and ZONES, you are to identify what we will refer to as a series of GROUNDINGS, sites or places in which your imagined city-landscape might come into contact with Naples. These GROUNDINGS, collectively, should identify and develop potential and proposed programmatic and material reciprocities for Naples, a network of programmes and architectures that engage in beneficial exchanges.

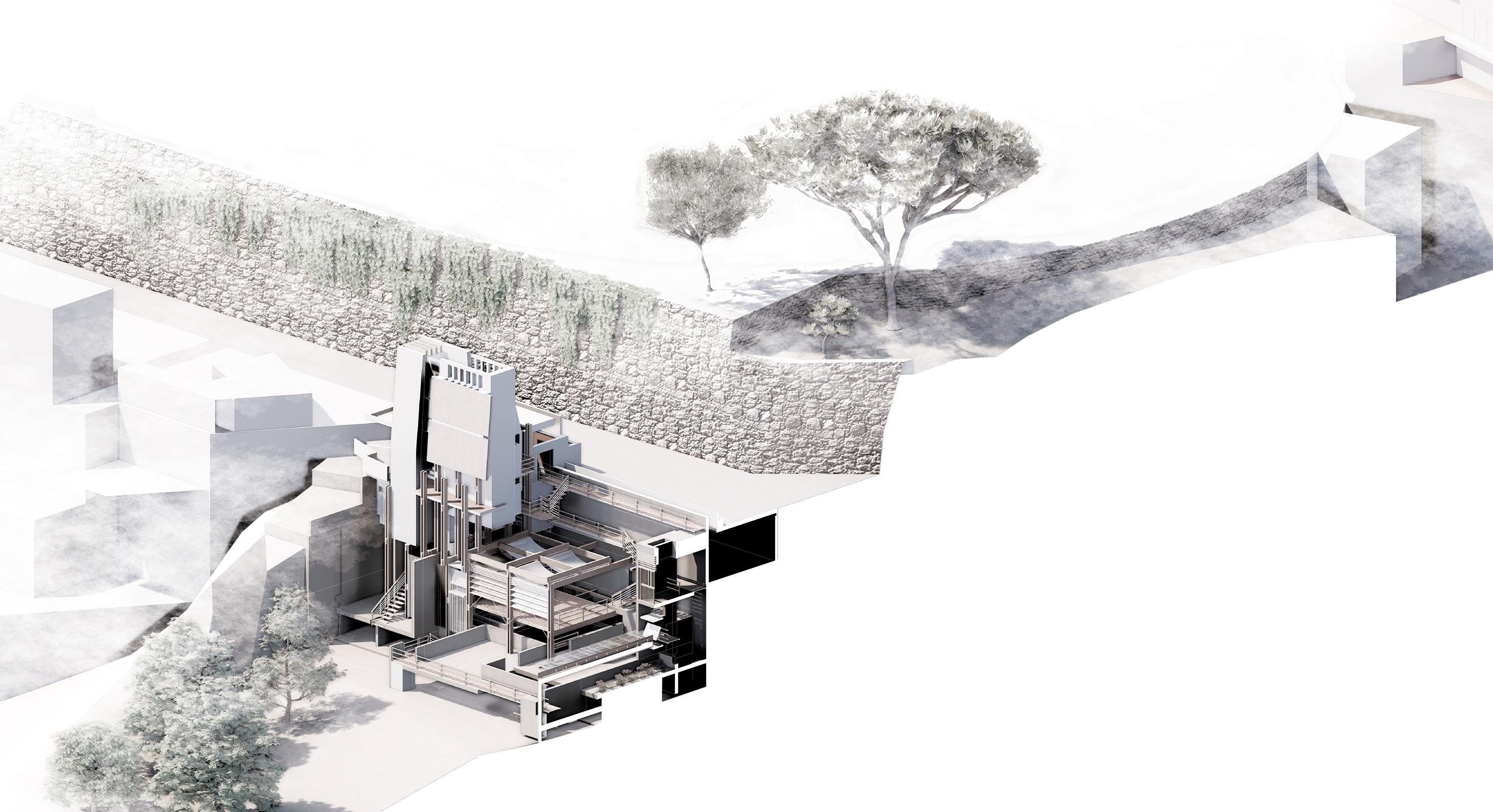

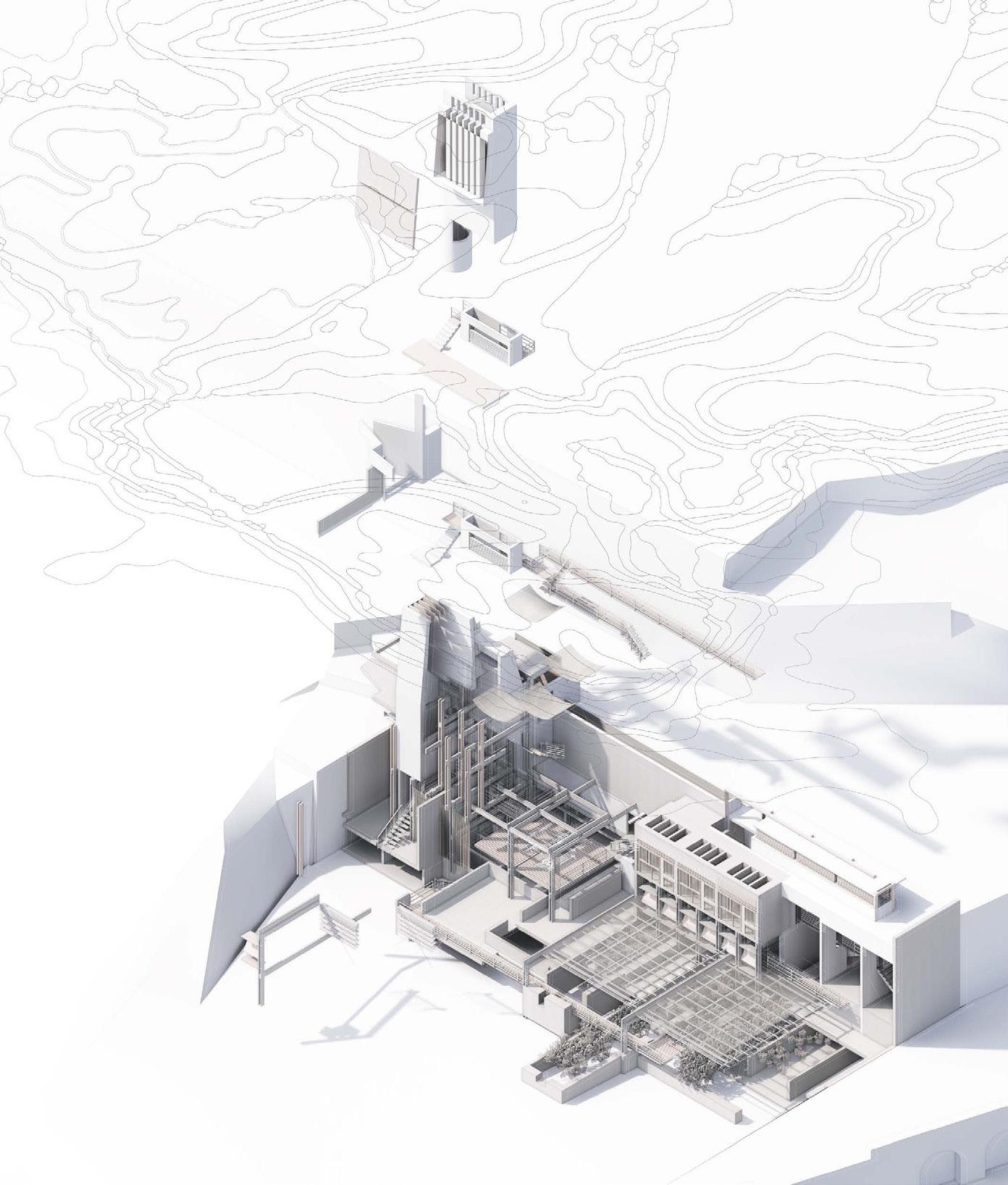

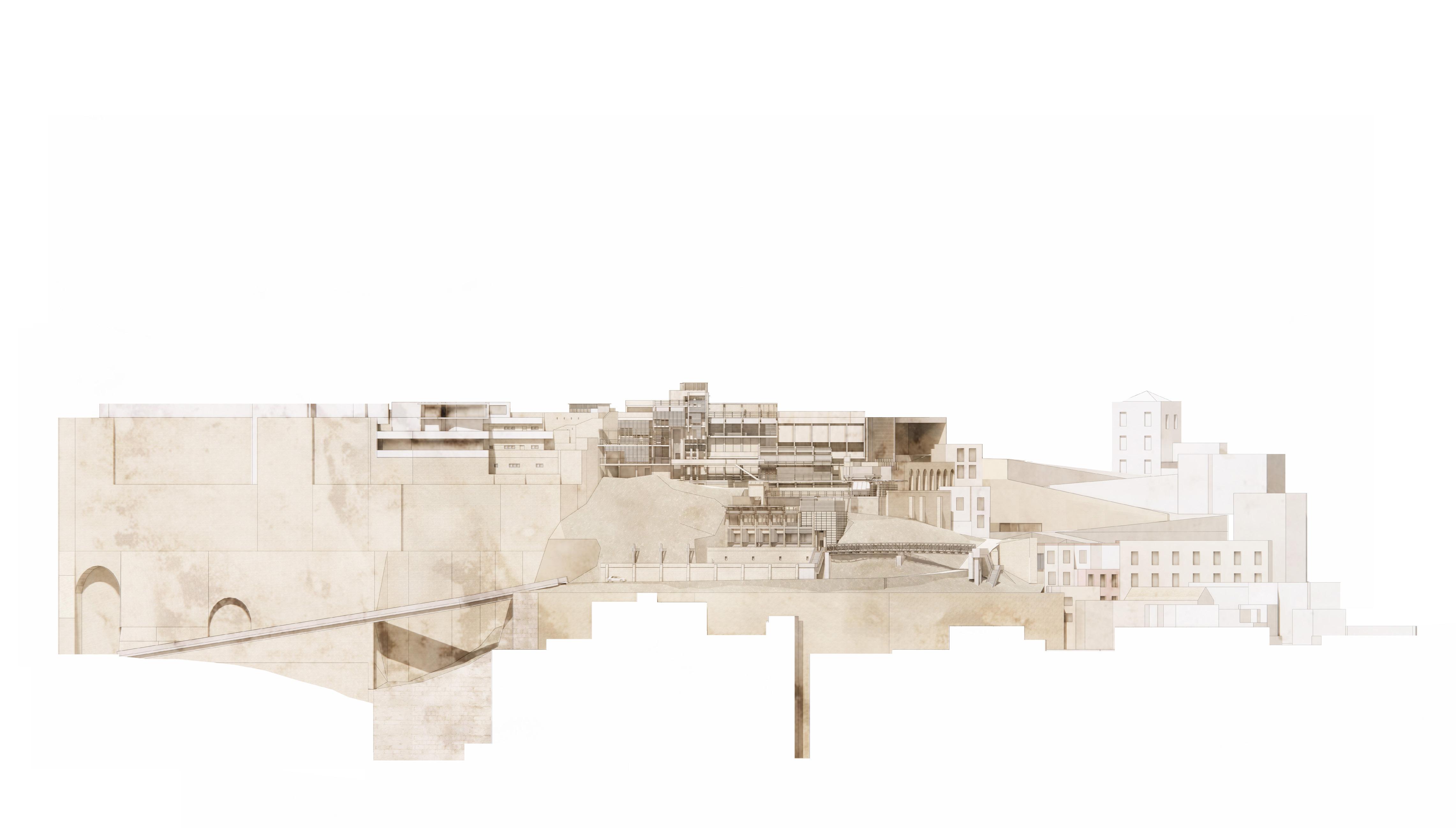

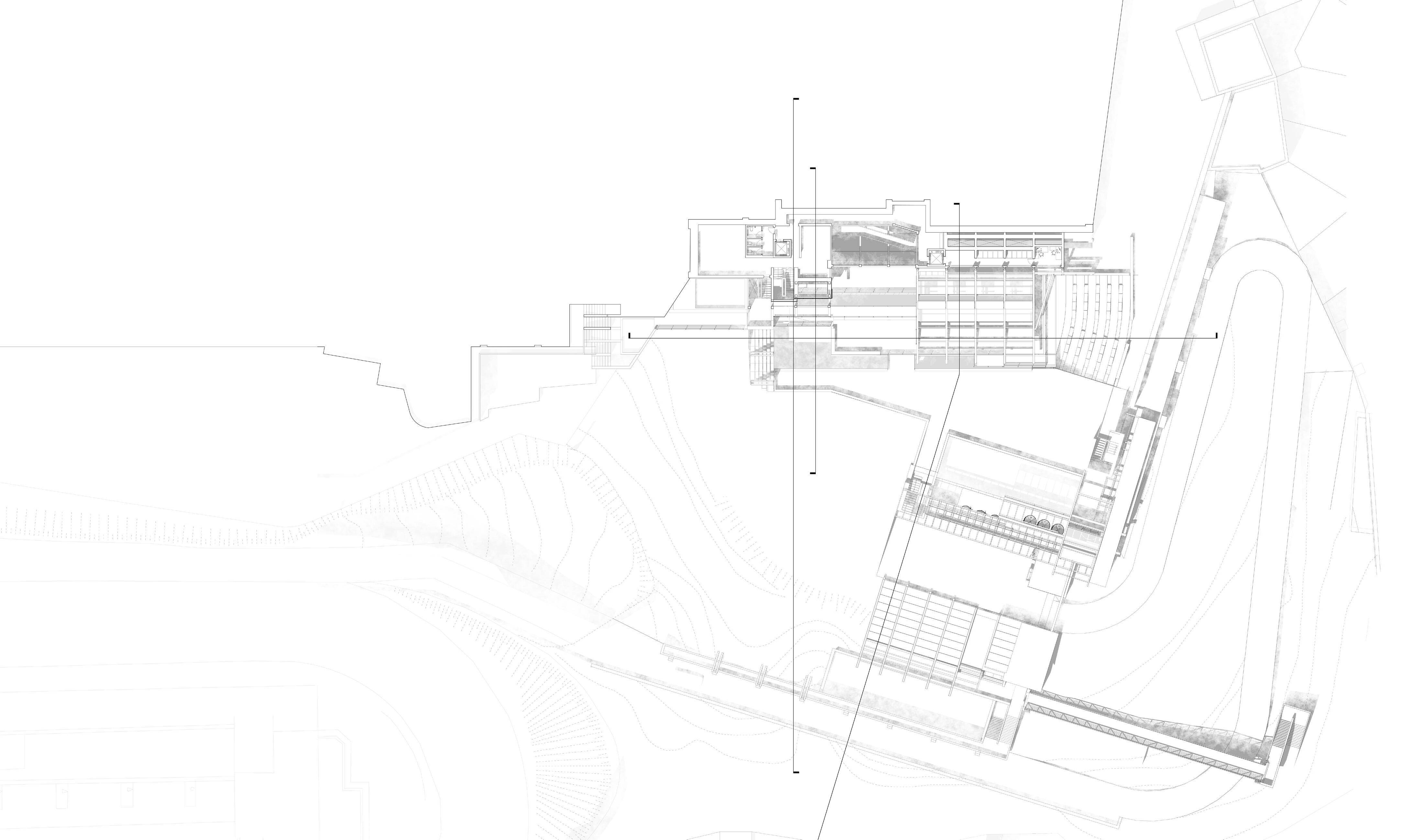

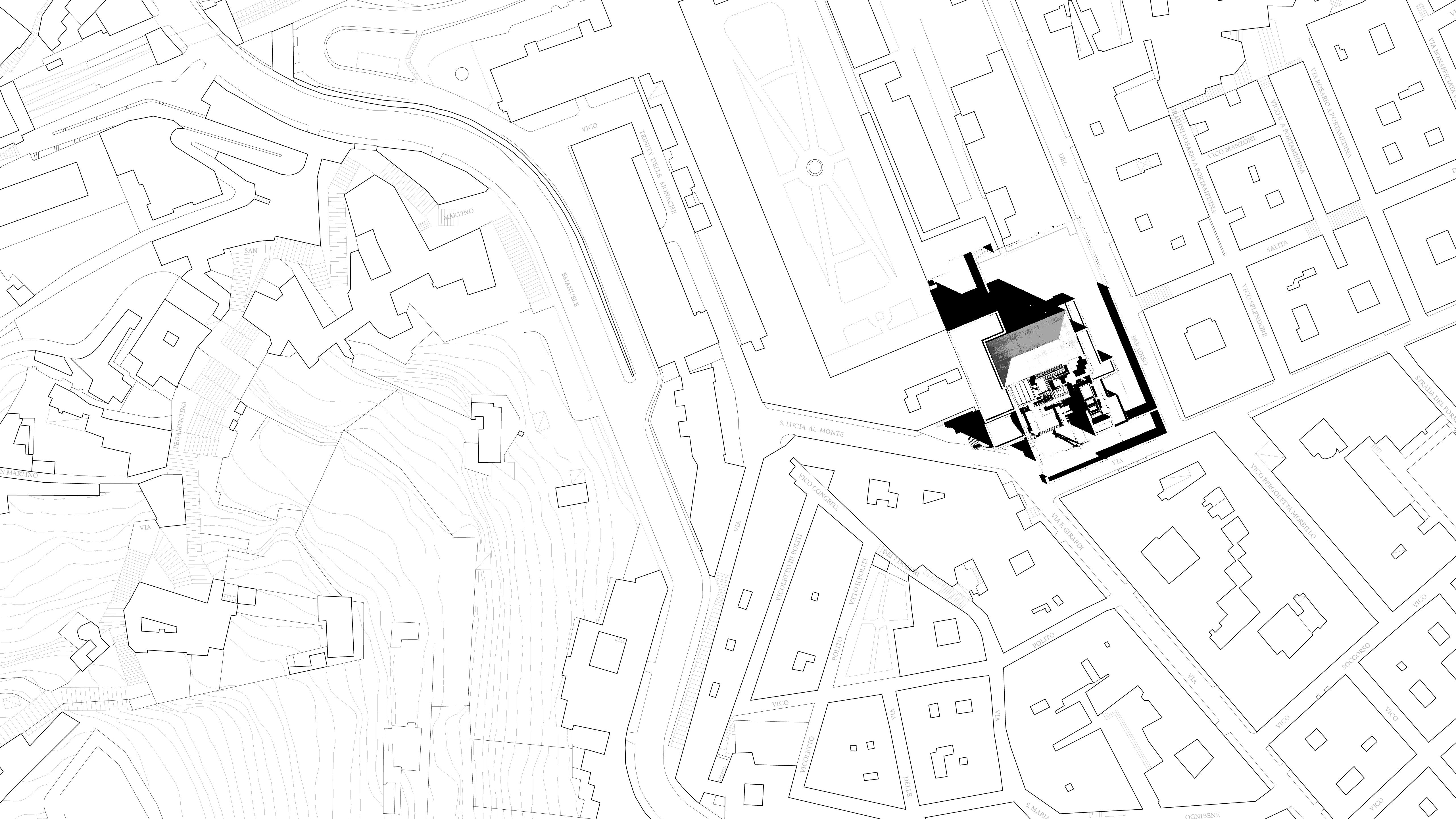

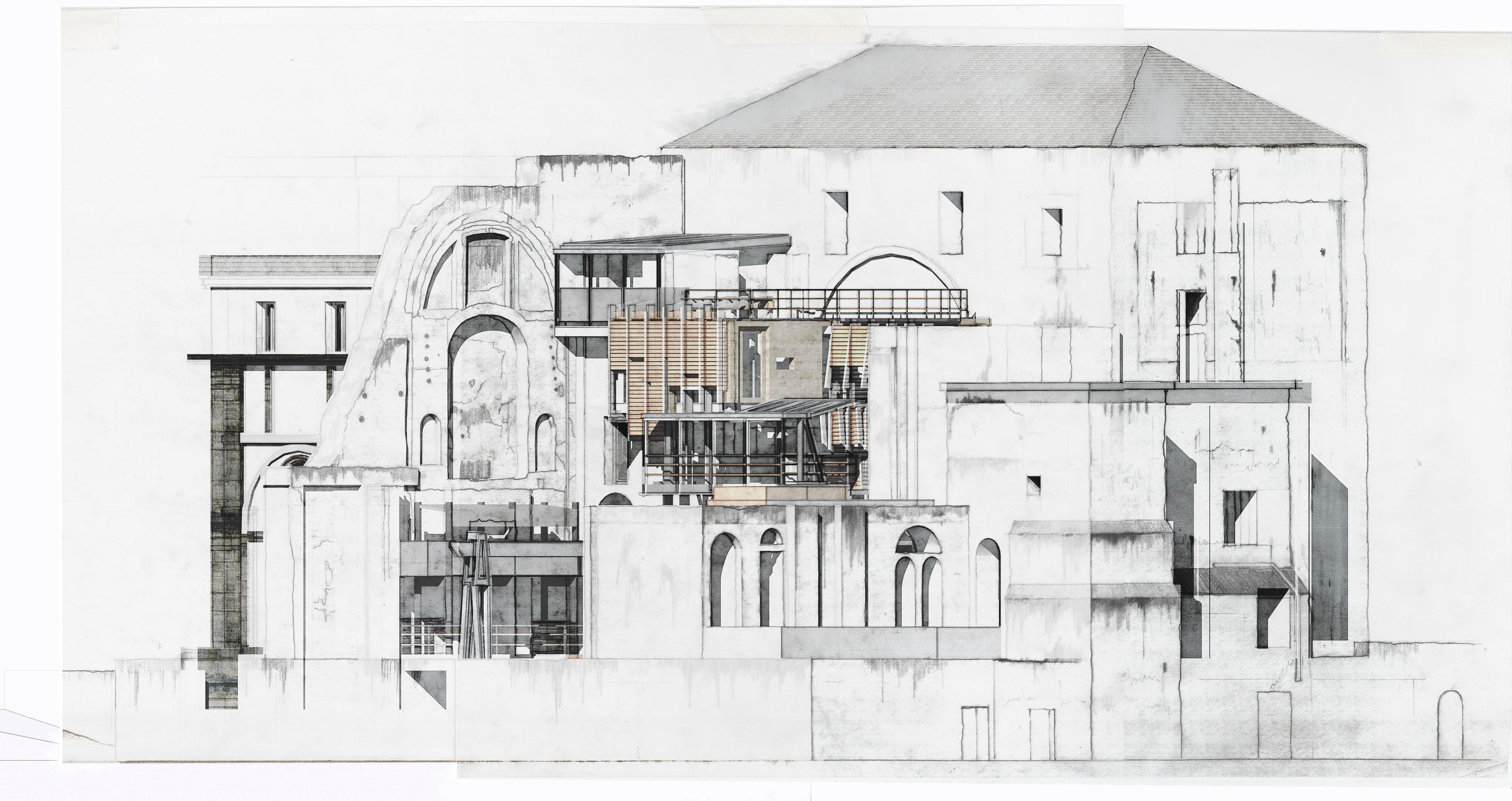

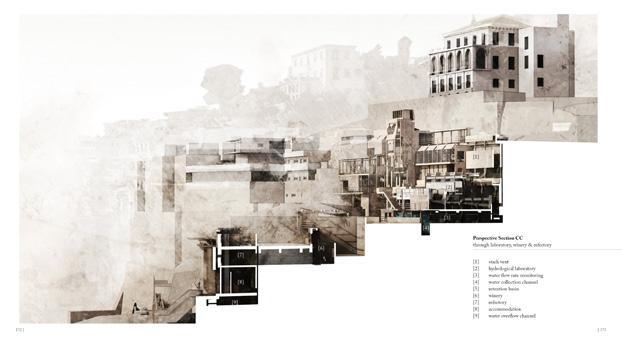

In the context of degradation, [Sup] planting Ground: A Repository for Pigments, Parts and Particulates intervenes as a mediator, seeking to further agitate and transform the existing ground condition by contending with aerosolised and excavated states. A series of undercutting and destructive gestures engage with and challenge the existing ground qualities of the site, with a particular focus on the Belvedere di Sant’Antonio Posillipo, a deteriorating concrete ruin that obstructs the tuff ridge. Liminal spaces operate as intermediaries, cultivating, conserving, and archiving elements of a synthetic field that operate at a particulate and territorial scale. These spaces enable a program that demands both confinement and ventilation, light and dark, moisture and dryness, with an acute sensitivity to the site’s materiality and context.

“It is really clear how the collective environmental concerns inform the programme, organisation and spaces of the architecture, eliminating mechanical ventillation specifically. There is a considered link between programme and remediation, and the use and adaptation of the existing structure to generate new types of spaces.”

Identifying a Site

Posillipo, a name derived from the Greek ‘Pausílypon’ or ‘respite from worry,’ has provided a haven outside the old city walls since the 1st Century BC, offering a sweeping panorama for villas that overlook the Bay of Naples. But as with many other coastal regions, Posillipo has fallen prey to unchecked development, pollution, and the loss of historic sites to modern construction or neglect. The ground, once porous, now bears the scars of extensive excavation, filling, terracing, and capping, leading to an artificial landscape that exacerbates drainage issues and atmospheric instability.

MOVE 5 // GROUNDINGS

Filed Labs

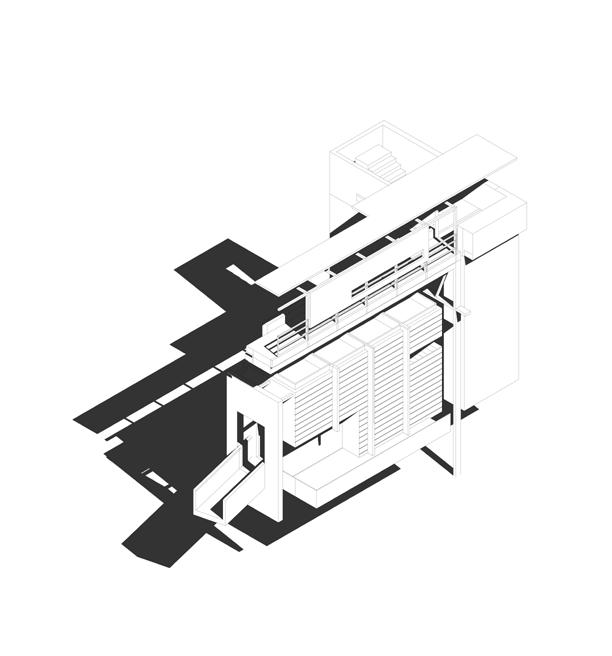

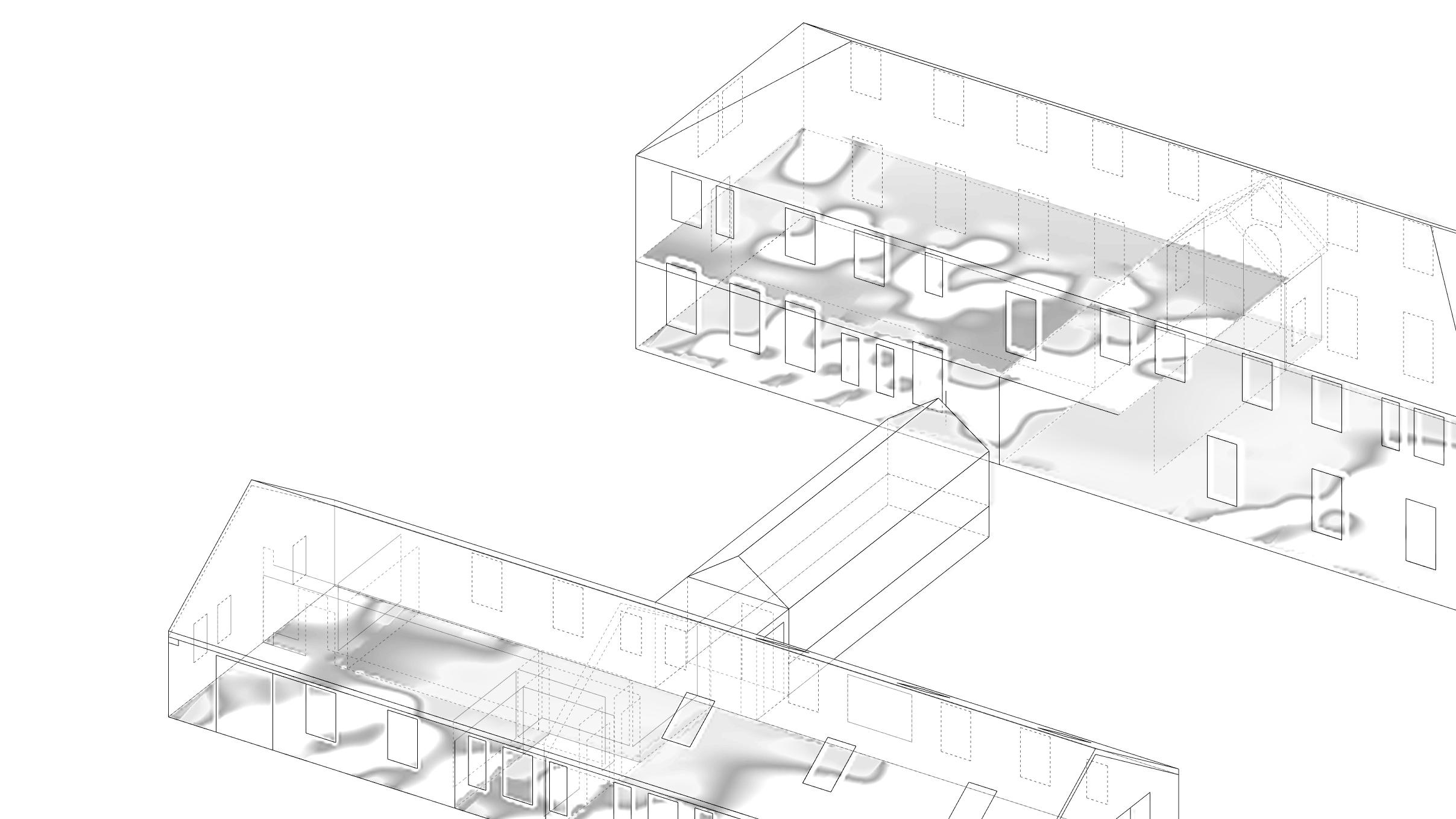

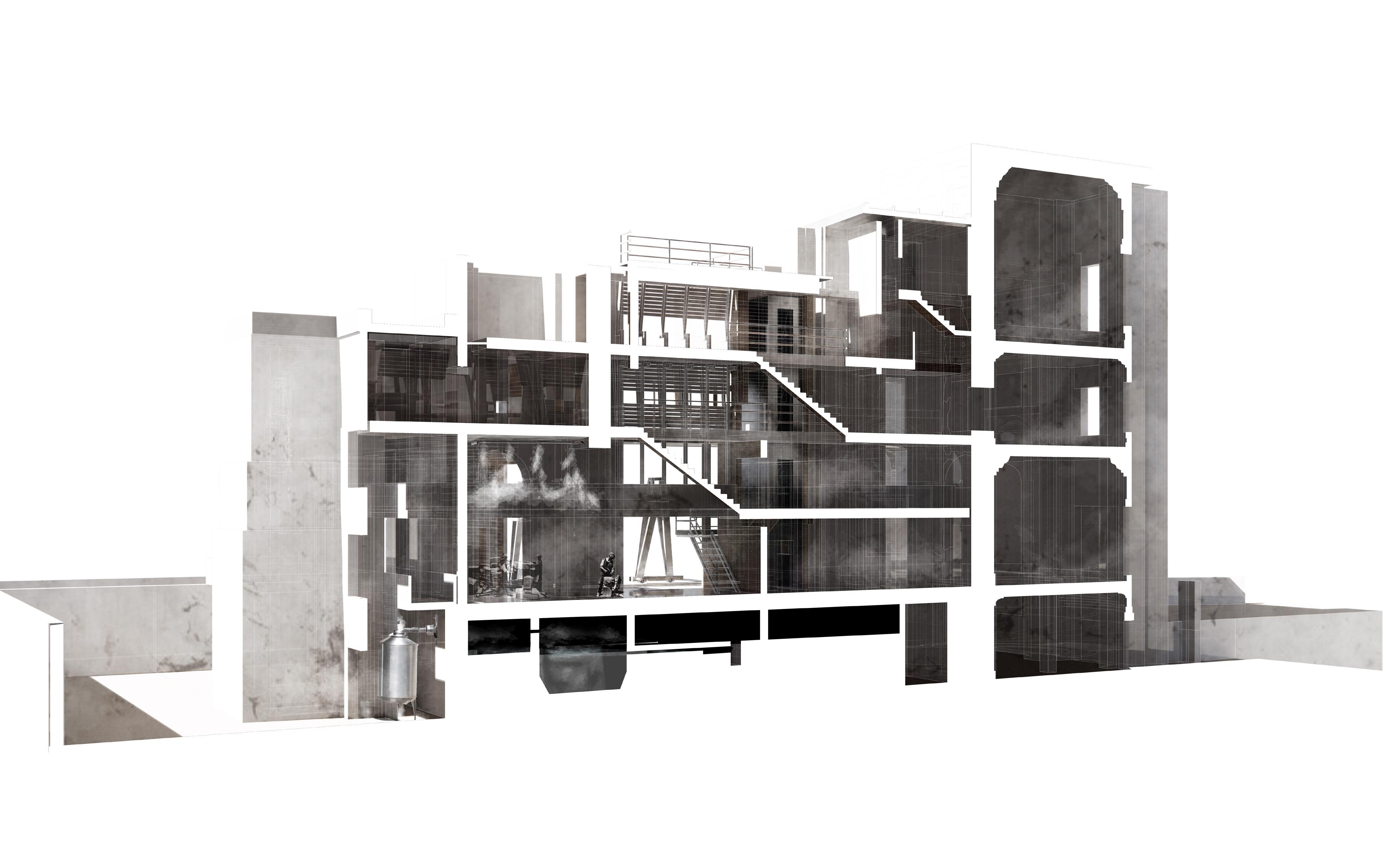

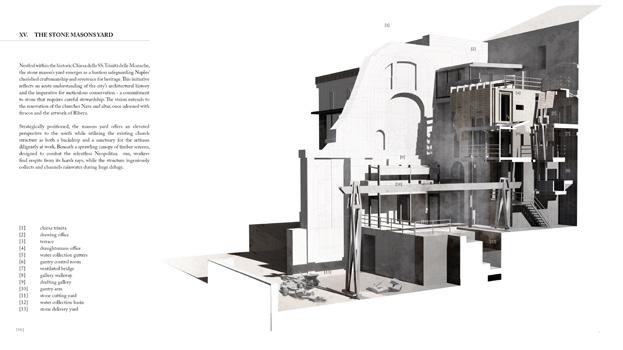

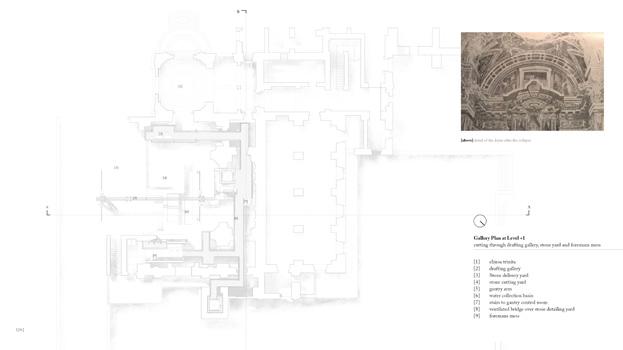

The individual proposal established a grounding within an existing concrete ruin. This field lab belongs to a larger set of enquiries and wider landscapes concerned with air remediation and ground movement, articulated through stack vents that remove the need for mechanical ventilation and a water collection system.

“Despite the programmatic and environmental richness, there is, however, still a sense that the proposal is detached from the language held by the Ground and Zone Construction. The scheme is contextually specific, but given the concerns of the thesis how might the descriptions of Ground embodied by the models and drawings challenge what we understand as architectural systems/spaces?”

The repository is housed in a deteriorating concrete ruin that plugs into the tuff ridge. The interplay of incompatible materials, a high elevation, and a steep topography creates a place of highest potential for air remediation via a system that uses pressure gradients within. Through this incision point, the ground becomes activated, with a succession of skins (or fronts, to use a meteorological term) to the building that channel particulates in the air through both dry and damp spaces. Within is a programme that works with these conditions and further agitates the concrete shell.

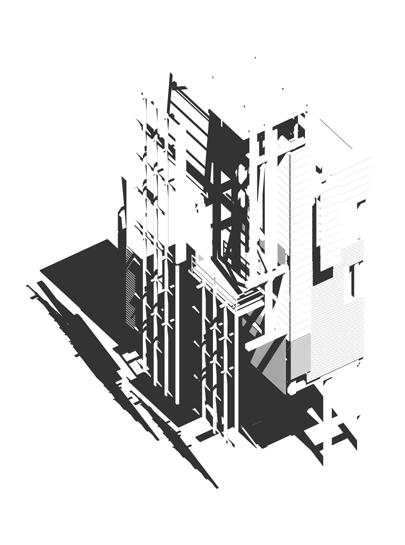

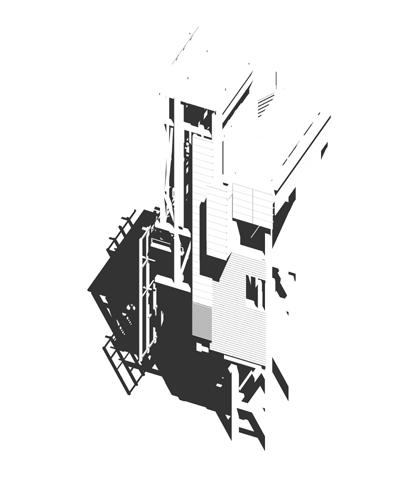

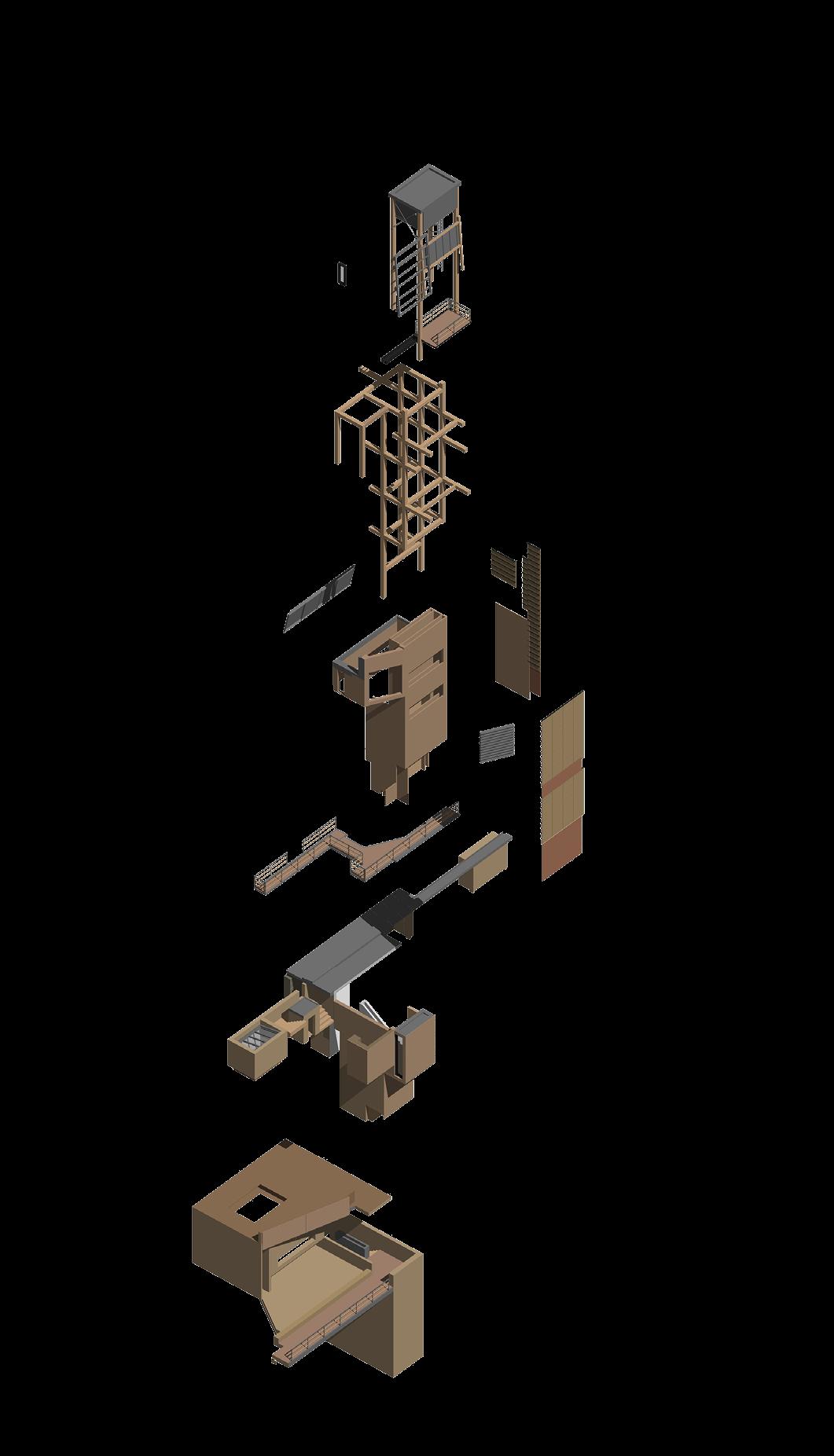

[above] renders showing the reuse of deteriorating ruin [right] exploded isometric of the ventilation hood

] etching of surface faults for zone contruction

STUDIO REFLECTION

This semester, I successfully tested the development of a design thesis through social, material and climatic issues. This was explored through group ‘Ground’ drawings and the Zone construction (drawings and installation), with further refinement developed in an individual ‘Field Lab’. It was clear how collective environmental concerns informed the programme, organisation and spaces of the architecture, but there was still a sense that the language held by the Ground and Zone construction was detached.

In terms of representation, the project was consistently drawn, in a variety of ways, although models were lacking. There were some really compelling drawings, particularly in 3D, but the renders lack specificity. Orthographic representation and speculative drawings still remain an aspect of my work I need to improve.

[2022]

Studies in Contemporary Archisectural Theory

[Course Aims]

[Course Synopsis]

[Course Organisers]

Dr Ella Chmielewska ARCH11070

[Seminar Organiser]

Dr Chris French

The course aims to:

1. Develop and expand your understanding of what theory is, and how it relates to architecture, design and the city.

2.Enhance your skills in critical reading and analysing the ideas presented in texts..

3.Refine your ability to write and communicate a focused critique of, and response to, texts.

Log records “observations, speculations, and ideas on architecture and the city at this point in our time and space.” Now in its 52nd issue, observation and speculation remain thefocus of Log; each issue gathers short written reflections on architecture, art, exhibition, history and theory, presented in such a way as to “resist the seductive power of the image in media.”

Through Unpacking Log we will look back at the now-past present of architectural thinking charted by Log. We will focus particularly on the question of material, on how material has been written about, described, theorised and made present in text in Log. Working through and around selected texts from the journal examining material — and accompanying para-texts specific to Log such as the postcards issued with each issue, summary sentences on the back cover, ‘Cover Stories’ and ‘General Observations’ scattered through each volume.

[Learning Outcomes]

LO1

A capacity to research a given theme, comprehend the key texts that constitute the significant positions and debates within it, and contextualise it within a wider historical, cultural, social, urban, intellectual and/or theoretical frame.

GC 2.1,3.1,4.1 // GA 2.4

LO2

An understanding of the way theoretical ideas and theories, practices and technologies of architecture and the arts are mobilized through different textual, visual and other media, and to explore their consequences for architecture.

GC 2.2,3.1,3.2

LO3

An ability to coherently and creatively communicate the research, comprehension and contextualisation of a given theoretical theme in relation to architecture using textual and visual media.

GC 2.2

The formats of the essay and journal are open, but their design must be thought out as a deliberate part of the submission. Think about the relation between text and image, and consider how you can use the structure and design of the documents to work in concert with the arguments that you are making.

The structure of the document is as follows:

MODALITIES OF REPRESENTATION

ERASURE

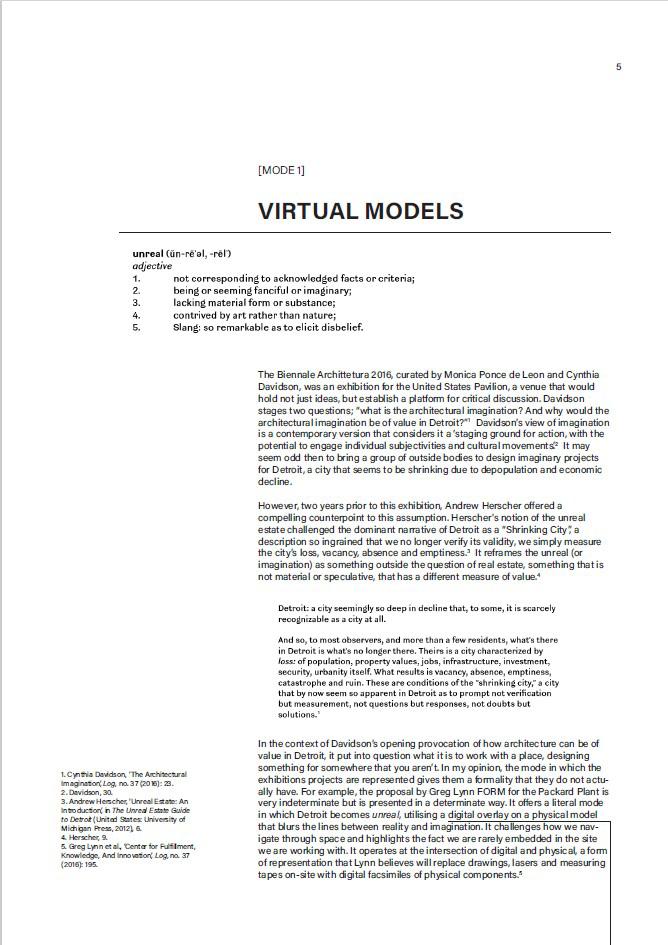

VIRTUAL MODELS

ABSTACTION

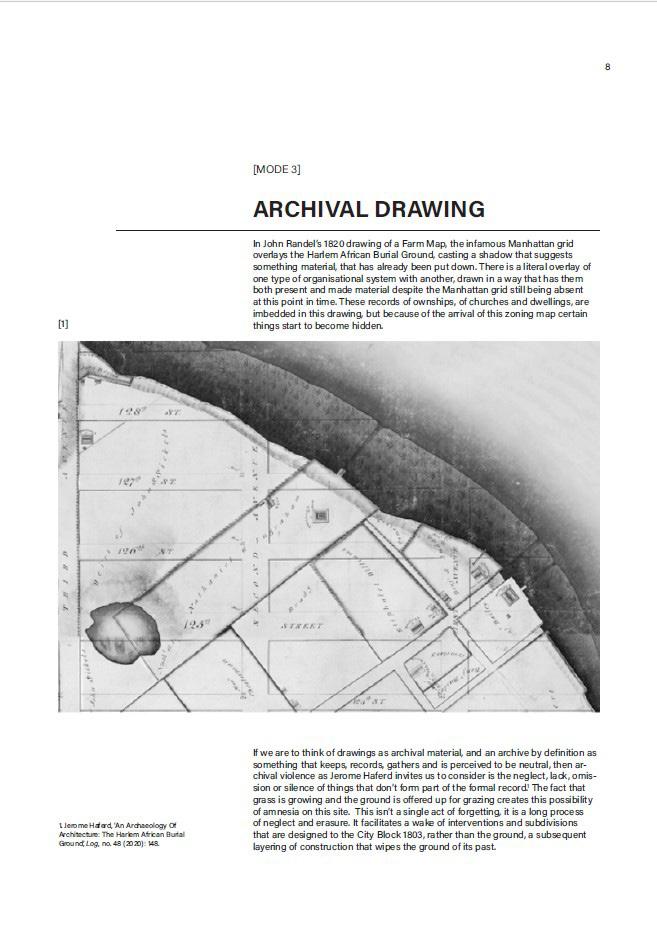

ARCHIVAL DRAWING

ALTERNATIVE CARTOGRPAHY

[RE]FRAMING

VISUAL BOUNDARIES

The reading journal (course diary) records your ongoing critical reflections and responses to the weekly readings and seminar discussions. You may reflect on what you find most interesting or most challenging in the reading, or discuss specific points of view. You may elaborate upon the significance of some aspects of the readings for contemporary architecture and/or urbanism. Each weekly entry should be at least 500 words and it should be illustrated as appropriate.

In my exploration of Log magazine, I noticed a fascinating evolution in its approach to images. Initially, the focus was on textual content, deliberately challenging the allure of images to foster deeper engagement with discourse. However, over time, there was a gradual incorporation of colourful visuals, perhaps reflecting a shift to online platforms and an acknowledgment of images’ power in shaping discussions. Inspired by this trajectory, I reflected on the interplay between image and text in architectural discourse, using the same format as Log itself.

This journal reflection explored Robert McNulty’s work in Log No.5, titled ‘What’s the Matter With Material?’, which served as an outlier in the set of representational modes explored. Despite this, it functioned as a tool for refining later explorations of Log and was purposely included as both a reference and symbolic act of erasure.

In Virtual Modes, the entry begins with a discussion surrounding the Biennale Archittetura 2016, curated by Monica Ponce de Leon and Cynthia Davidson, as an exhibition aimed at sparking critical discussions, particularly regarding the architectural imagination and its relevance in Detroit. I critique the exhibition’s virtual portrayal of architectural projects for Detroit, noting that they often lack a genuine understanding of the city’s context and needs. I also question the appropriateness of using Detroit as a platform for architectural discourse without offering tangible solutions, and emphasise the importance of further exploration and inquiry into the role of imagination in architecture.

Key Readings

Davidson, Cynthia. ‘The Architectural Imagination’. Log, no. 37 (2016): 22–31. Herscher, Andrew. ‘Unreal Estate: An Introduction’. In The Unreal Estate Guide to Detroit. United States: University of Michigan Press, 2012. https://www. jstor.org/stable/j.ctvdtphxh.4. Lynn, Greg, Melissa Shin, Sean Boyd, May Wang, Jasper Lynn, Peter Vikar, Jia Gu, et al. ‘Center for Fulfillment, Knowledge, And Innovation’. Log, no. 37 (2016): 194–203.

In Abstraction, I explore the dynamics of urban experience through the lens of the London Underground and Manhattan’s grid layout. Jobst’s observations lead to a philosophy of dislocation and endless compositions, departing from Heidegger’s rootedness and embracing indeterminacy. Drawing from Deleuze, Jobst proposes a philosophy that constructs spaces amidst existing terrains, emphasizing experimentation and intentional connection. This refiguring of abstraction offers a deeper understanding of urban space as a complex, dynamic system, constantly evolving and layered with meaning.

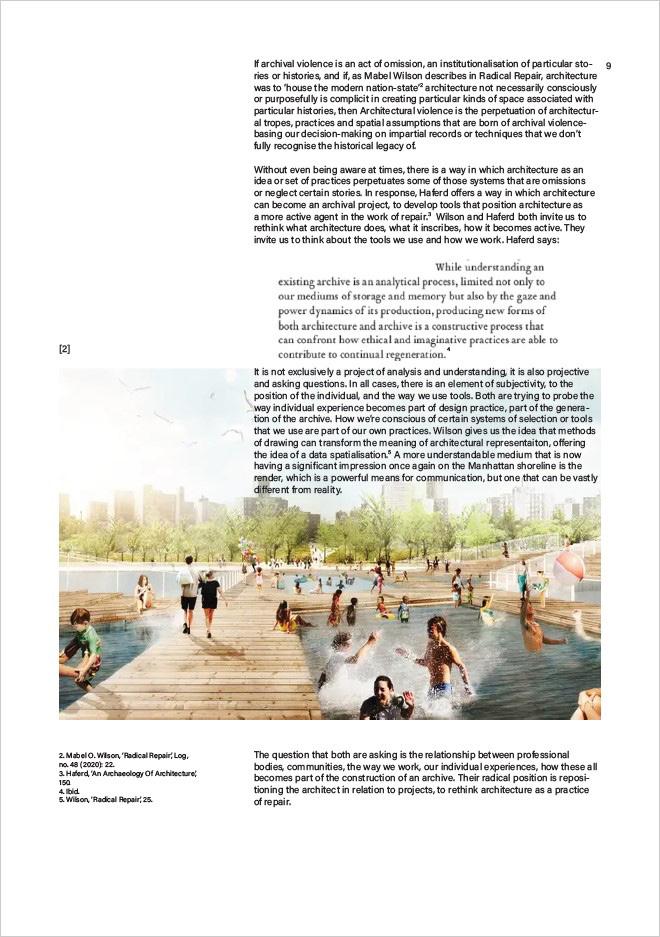

In Archival Drawing, I explore the complexities of architecture and urban history through John Randel’s 1820 Farm Map of Manhattan. I discuss issues of archival violence and architectural neglect, as well as proposals by Jerome Haferd and Mabel Wilson to rethink the role of architects in repairing historical omissions. This prompts a call for architects to actively engage with communities and histories in our work.methods as transformative tools in architectural representation. This journal underscores the subjective nature of architectural practice and calls for a repositioning of architects as agents of repair, actively involved in engaging with communities and histories in our work.

Key Readings Key Readings

Jobst, Marko. ‘Abstracting the Text’. Log, no. 26 (2012): 9–13.

Rajchman, John. Constructions / John Rajchman.

Writing Architecture Series. Cambridge, Mass. ; MIT Press, 1998.

Haferd, Jerome. ‘An Archaeology Of Architecture: The Harlem African Burial Ground’. Log, no. 48 (2020): 145–54. Wilson, Mabel O. ‘Radical Repair’. Log, no. 48 (2020): 21–26.

In Abstraction, I explore the dynamics of urban experience through the lens of the London Underground and Manhattan’s grid layout. Jobst’s observations lead to a philosophy of dislocation and endless compositions, departing from Heidegger’s rootedness and embracing indeterminacy. Drawing from Deleuze, Jobst proposes a philosophy that constructs spaces amidst existing terrains, emphasizing experimentation and intentional connection. This refiguring of abstraction offers a deeper understanding of urban space as a complex, dynamic system, constantly evolving and layered with meaning.

In Archival Drawing, I explore the complexities of architecture and urban history through John Randel’s 1820 Farm Map of Manhattan. I discuss issues of archival violence and architectural neglect, as well as proposals by Jerome Haferd and Mabel Wilson to rethink the role of architects in repairing historical omissions. This prompts a call for architects to actively engage with communities and histories in our work.methods as transformative tools in architectural representation. This journal underscores the subjective nature of architectural practice and calls for a repositioning of architects as agents of repair, actively involved in engaging with communities and histories in our work.

Latour, Bruno. “Seven Objections Against Landing on the Earth.” In Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth, 12-19. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020.

Salgueiro Barrio, Roi and Gabriel Kozlowski. “Cutting the Earth: Seven Cases of the Planet in Section.” Log, no. 51 (Winter/Spring 2021): 63-74. Renken, Anna. ‘Reassessing Critical Zones’ Log, no.51 (2021): 61-62.

Alonso, Pedro Ignacio. ‘Mountaineering’. AA Files, no. 66 (2013): 81–86.

Varnelis, Kazys. ‘The Potential of Passaic’. Thresholds, no. 36 (2009): 72–77.

Marullo, Francesco. ‘To Desert’ Log, no.55 (2022): 121-130

An illustrated essay (approximately 3,000 words +abstract + references + captions) that explores a topic of your choice, arising from the seminars and readings. The essay is not intended to be a comprehensive analysis or overview of the material covered in the seminar option, but rather an investigation of a specific topic connected to it that interests you.

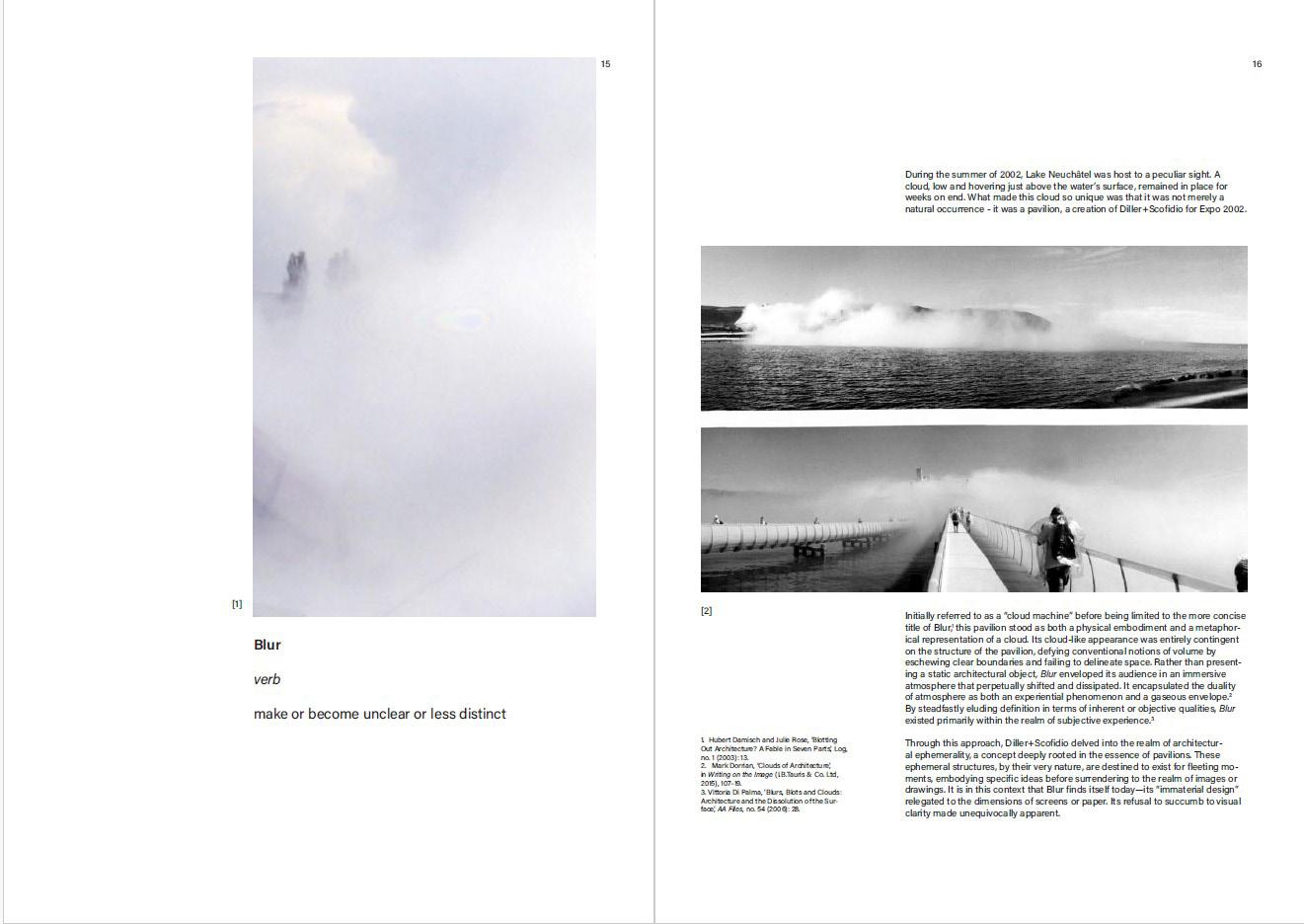

Initially referred to as a “cloud machine” before being limited to the more concise title of Blur, this pavilion stood as both a physical embodiment and a metaphorical representation of a cloud. Its cloud-like appearance was entirely contingent on the structure of the pavilion, defying conventional notions of volume by eschewing clear boundaries and failing to delineate space.

In this sense, the drawings of Blur are perhaps most effective when viewed in conjunction with the accompanying film of the project. Through the use of a diptych shot, the interior and exterior scenes converge, capturing the mist and fog that swirls and blurs visitors as they traverse the pavilion. In this composition, the fleeting qualities of the cloud linger, preserved within the juxtaposition of frames.

Abstract:

This essay embarks on an exploration of blurs, splits, and frames in the realms of art and architecture, interrogating conventional notions of representation and perception. A visual dialogue is established, bringing together the works of Diller+Scofidio, John Ruskin, J.M.W Turner, Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Brodsky, Peter Zumthor, and James Turrell. The aim is to delve into the complexities of capturing ephemeral phenomena, such as clouds and atmospheric experiences, in static forms. In scrutinizing these diverse artistic and architectural explorations, the essay unveils the multifaceted nature of representation and perception. It calls into question the visual boundaries that confine our understanding,urgingustoembracethefluidityand complexity inherent in capturing the ephemeral and embodyingtheintangible.

[1]Diller + Scorfidio. ‘Blur Building’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://dsrny.com/project/ blur-building

[2]Diller + Scorfidio. ‘Blur Aerial’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://dsrny.com/project/ blur-building

[3]Diller + Scorfidio. ‘A massive fog machine’ Blur: The Making of Nothing (2002): 98.

[4] Diller + Scorfidio. ‘correspondence: structure’ Blur: The Making of Nothing (2002): 82-83. Key Images

BRIEF O2 // ESSAY

Representing ephemerality poses a challenge in capturing objects and perceptions fleeting nature. John Ruskin proposed simplifying perspective for the sky, but it failed to capture clouds motion.

J.M.W. Turner’s paintings, like Pools of Solomon, expressed the ephemeral atmosphere, breaking through perspective’s limits. Ruskin attempted to quantify Turner’s work with a curvilinear system, contradicting the cloud’s nature. Brunelleschi ingeniously used a conical aperture and mirror to capturetheBaptistery’sperspective,omittingthesky.

Extract 1: Extract 2: Representing ephemerality in a way that captures both the nature of objects and a viewer’s perception of them poses a significant challenge. This challenge has its roots in the 18th-century preoccupation with exploring the fleeting nature of perception and the understanding that even stable objects such as buildings appear different from various viewpoints, times of day, and to different viewers. This awareness of perception’s heterogeneity was further complicated by the changeability of objects themselves, highlighting a central problem in representation: how to fix an object in a state of constant change, to capture the evanescence of a cloud.

[6]John Ruskin. ‘Cloud Perspective (Rectilinear)’, Modern Painters (1888) vol. V plates 64.

[7]The Fitzwilliam Museum. ‘Pools of Solomon, by Turner’ (Website) Last accessed 8th May 2023. https://collection.beta.fitz.ms/id/image/ media-1569848515.

[8]John Ruskin. ‘Analytical Sketch of the sky’, Modern Painters (1888) vol. V fig. 83.

[9]John Ruskin. ‘Cloud Perspective (Curvilinear)’, Modern Painters (1888) vol. V plates 65.

The attempt to deconstruct an image also works to question what it is to construct one. While Ruskin’s grid was predicated on a split between sky and ground, leading to a plane that worked independently, this construction of space begins to challenge the notion of how we describe and construct a view, echoing the themes explored in Damisch’s analysis of Brunelleschi’s painting of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence.

Key Images

[10]Filippo Brunelleschi, ‘Perspective Technique’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023, https:// www.sas.upenn.edu/moyer/coursepages/hist308-ren/ data/Alberti.html.

[11] Shem Louis. ‘Brunelleshi and the re-discovery of Linear Perspective’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://editions.covecollective.org/content/

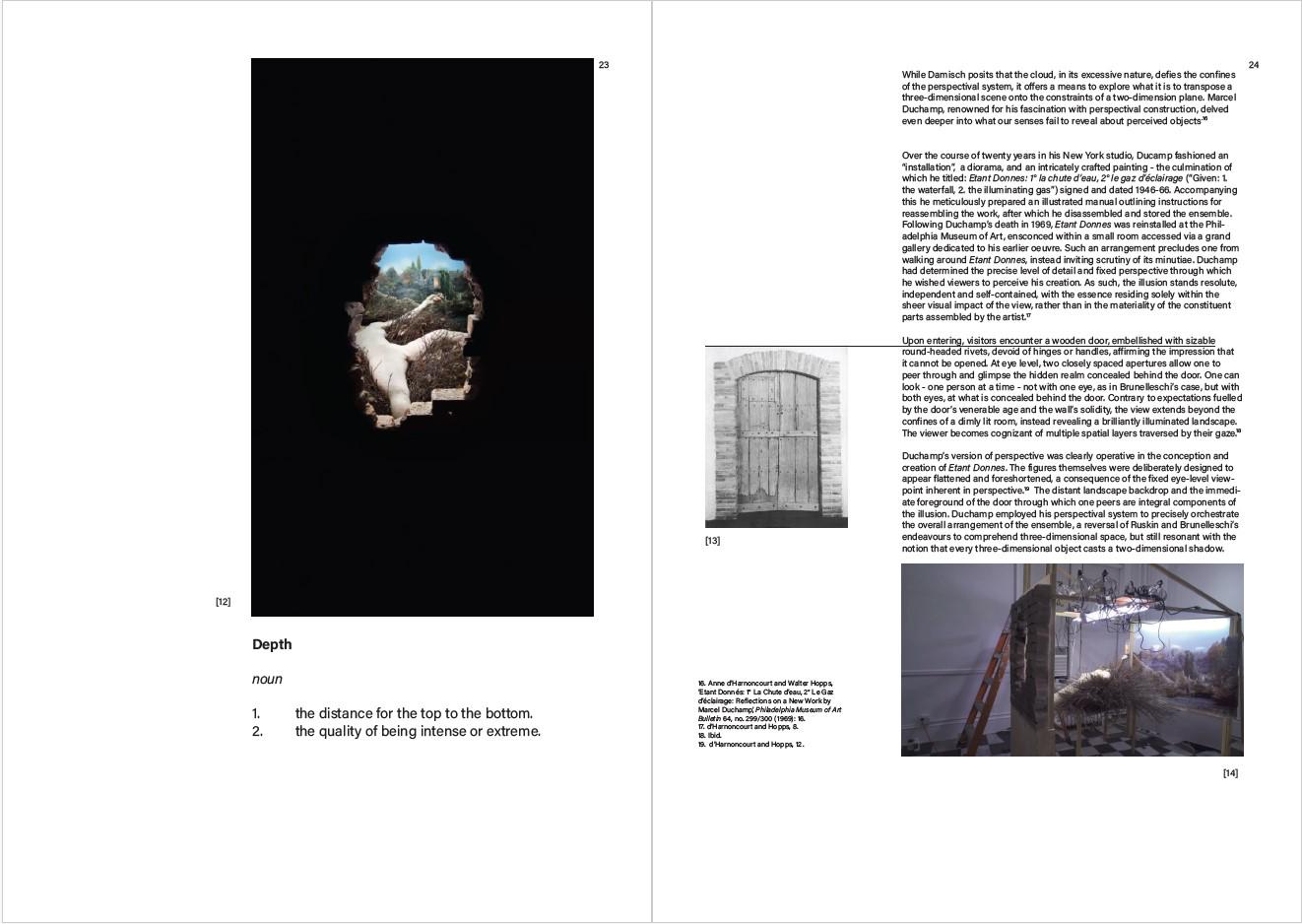

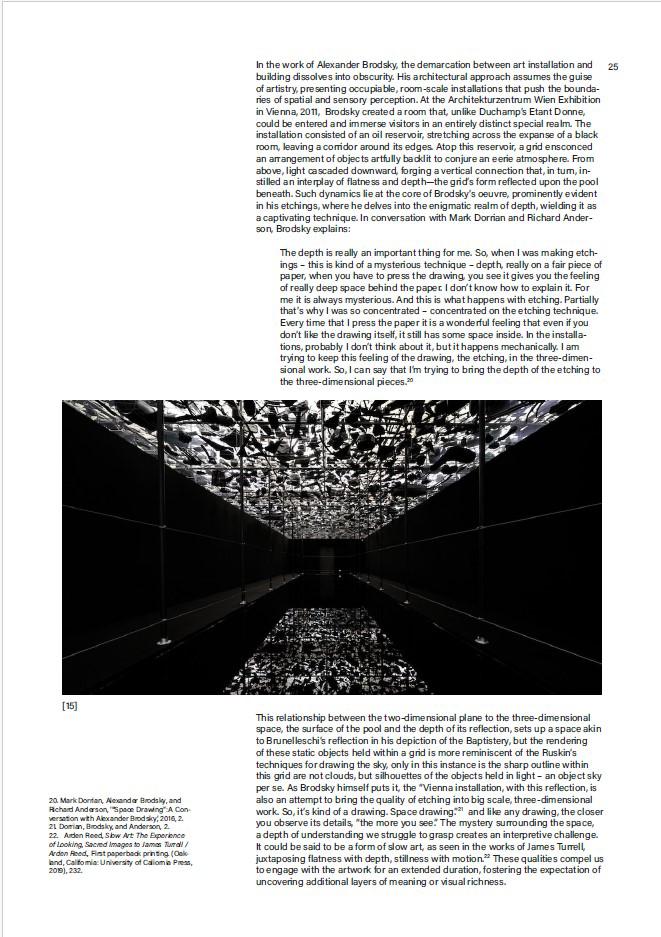

Damisch suggests clouds, in their excessive nature, challenge perspectival confines, exploring transposing 3D scenes onto a 2D plane. Duchamp’s “Etant Donnes” employs fixed eye-level viewpoints, elevating clouds beyond perspectival limits. Conversely, Brodsky’s installations merge art and architecture, delving into depth and surface interplay.

Duchamp’s version of perspective was clearly operative in the conception and creation of Etant Donnes. The figures themselves were deliberately designed to appear flattened and foreshortened, a consequence of the fixed eye-level viewpoint inherent in perspective. The distant landscape backdrop and the immediate foreground of the door through which one peers are integral components of the illusion.

[above] Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas

This relationship between the two-dimensional plane to the three-dimensional space, the surface of the pool and the depth of its reflection, sets up a space akin to Brunelleschi’s reflection in his depiction of the Baptistery, but the rendering of these static objects held within a grid is more reminiscent of the Ruskin’s techniques for drawing the sky, only in this instance is the sharp outline within this grid are not clouds, but silhouettes of the objects held in light –an object sky per se. As Brodsky himself puts it, the “Vienna installation, with this reflection, is also an attempt to bring the quality of etching into big scale, three-dimensional work. So, it’s kind of a drawing. Space drawing.”and like any drawing, the closer you observe its details, “the more you see.” The mystery surrounding the space, a depth of understanding we struggle to grasp creates an interpretive challenge. It could be said to be a form of slow art, as seen in the works of James Turrell, juxtaposing flatness with depth, stillness with motion.These qualities compel us to engage with the artwork for an extended duration, fostering the expectation of uncovering additional layers of meaning or visual richness.

[12] Marcel Duchamp. ‘(Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . .)’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsyeditorial-duchamps-work-hold-one-final-secret

[13] Anne d’Harnoncourt and Walter Hopps. ‘Etant Donnés: 1° La Chute d’eau, 2° Le Gaz d’éclairage: Reflections on a New Work by Marcel Duchamp’, Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 64, no. 299/300 (1969): 6, https://doi.org/10.2307/3795242. [14] Marcel Duchamp. ‘(Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . .)’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsyeditorial-duchamps-work-hold-one-final-secret [15] ArchDaily. ‘Alexander Brodsky at Architekturzentrum Wien in 2011’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://www. archdaily.com/375085/alexander-brodsky-atarchitekturzentrum-wien-in-2011

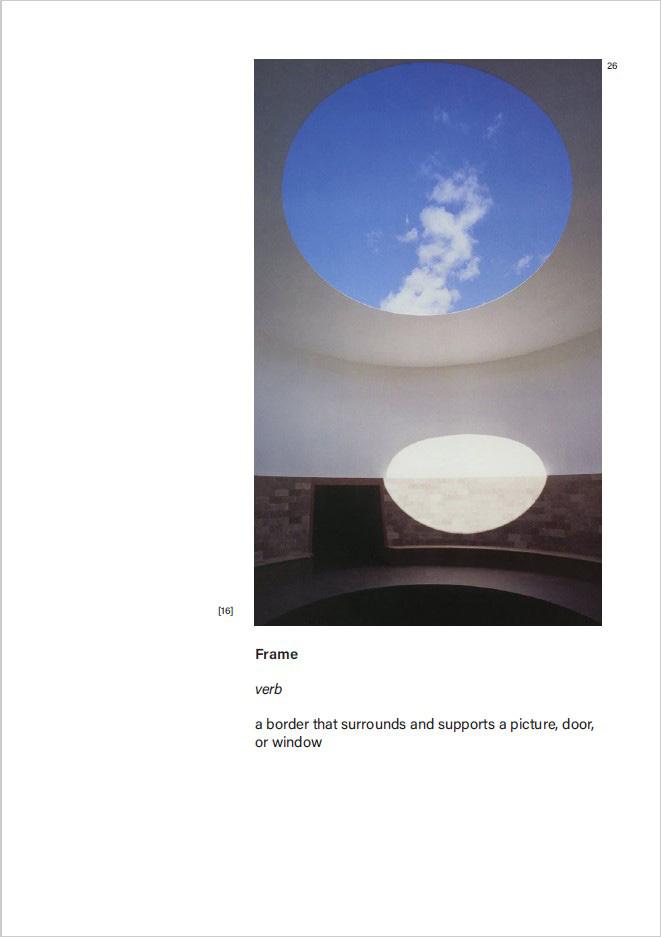

Zumthors Sepentine Pavilion created a vertical division, with the sky forming a separate plane, enhancing the ethereal ambiance. Similarly, Turrell’s Skyspaces merge interior and exterior realms, inviting viewers to reevaluate their perception of space. Unlike Zumthor’s enclosed garden, Turrell’s Skyspaces focus on contemplation of the sky itself, blurring boundaries and expanding visual horizons.

Extract 1: What unfolded was a construction of space predicated on a profound division, both laterally and, in the context of Ruskin’s and Brunelleschi’s renderings of the sky, vertically. The patch of sky occupied a separate plane, distinct from the ground plane, thereby establishing a unique dichotomy. The interplay between these distinct realms imbued the pavilion with an ethereal quality, as the luminous backdrop of the sky played its part in the theatrical performance of light within the structure.

In the context of Diller + Scorfiodio’s Blur, Turrell’s Skyspaces also work to give material form to a formless object, with light opposed to the cloud assuming a tactile quality.They frame like the camera lens of there accompanying film. Just as Turner, the painter of light, fascinated Ruskin, Turrell, too, was captivated by the painterly qualities of light. However, Turrell moved beyond traditional painting techniques and began to work with light itself. The monumental Roden Crater project in Arizona epitomizes his engagement with light and transcendent proportions. At Roden Crater, he sculpts the sky, evoking the concept of “celestial vaulting,” perceiving the sky as a moulded inverted bowl rather than a shapeless expanse.Turrell incorporates the immense dimensions of nature, harnessing celestial light and the boundless expanse of the sky. The desert assumes a central role serving as both the context and framing device that envelops the entire composition. The absence of building envelope becomes a way to capture the cloud.

[16] James Turrell. ‘Skyspaces’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://tlmagazine.com/jamesturrell-gives-us-an-insight-into-his-roden-crater/v [17] ArchDaily. ‘Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2011’ Website) Last access 10th May 2023. https:// www.archdaily.com/146392/serpentine-gallerypavilion-2011-peter-zumthor/whimg0090-presspage?nextproject=no

[18] Sarah Lee. ‘Zumthor’s Serpentine Pavilion’ (Website) Last access 10th May 2023. https:// www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2011/ jun/27/peter-zumthor-serpentine-pavilionarchitecture#img-1

[19] Guggenheim. ‘James Turrell – Skyspace’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https://www. guggenheim.org/artwork/4089

[20] James Turrell. ‘Shadowed Bowl in Grey, 1992’ (Website) Last accessed 10th May 2023. https:// www.nevadaart.org/art/exhibitions/james-turrellroden-crater/

[2023]

[Course Organiser]

Dr Chris French

[Course Aims]

The course will allow students to:

1. Acquire understanding of the processes and delivery of design projects, and of project and practice management.

2. Understand the concept of professional responsibility and the legal, statutory, and ethical implications of the title of architect.

3. Understand the roles and responsibilities of the architect in relation to the organisation, administration, and management of an architectural project and the execution of an architect’s professional and social responsibilities.

4. Develop an awareness and understanding of the financial, social and ethical matters bearing upon the creation and construction of the built environment.

5. Develop an awareness of the changing nature of the construction industry, including relationships between individuals and organisations involved in modern-day building procurement.

[Contributions]

Francisco Frankenberg Garcia [FFG]

Lewis Murray [LM]

[Course Synopsis]

This course delves into themes highlighted by RIBA (and ARB), covering economic, legislative, organisational, and cultural aspects impacting architectural practice. Lectures explore regulations, the climate crisis, activism, public procurement, gender, fees, and representation, shedding light on pivotal issues within the profession. Discussions address structural practices, architects’ roles in environmental and social concerns, and challenge professional norms. It prompts critical examination of professionalism, emphasising architects’ societal responsibilities beyond legal obligations. By navigating RIBA’s framework and developing informed perspectives on architectural issues, participants are encouraged to engage with the profession’s evolving landscape and contribute to societal well-being.

[Learning Objectives]

LO1

An understanding of codes of professional conduct, practice management, competency and ethics as relevant to the role of the architect in the design team, and in the context of the construction industry within society.

GC 6.1, 6.2, 11.1, 11.3 // GA 2.5, 2.7 LO2

An understanding of the roles and responsibilities of individuals and organisations within architectural project procurement, including the management of costs and risks, contract administration and postoccupancy evaluation.

GC 6.2, 10.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2 // GA 2.5, 2.6 LO3

An understanding of the influence of statutory, legal and professional responsibilities on the development of architectural design projects.

GC 4.3, 6.1, 10.3, 11.1 // GA2.5, 2.6, 2.7

OVERVIEW // COURSE REPORT

1. Critical Contemporary Practices Essay

Task(s)

A critical, researched response to one of the course lectures in the form of a Critical Contemporary Practice(s) essay. The essay is intended to encourage the development of research competency and critical thinking. In addition to making reference to the key readings and supporting texts listed in this syllabus, I was encouraged to pursue my own research, contact organisations and individuals who are concerned with the themes under discussion, and develop my own reading and resource lists.

2. Three Thematic Reflections

Three short reflections on three other lectures in the lecture series which are chosen from the lectures to guide these reflections whilst remaining informed by my own interests and sense of the urgencies affecting contemporary architectural practice.

3. Contractual Scenario Response

A response to one of the contractual scenarios explored through the Contract Workshops. This takes the form of a file note for my practice records, documenting the relevant factors guiding my response (the circumstances guiding my decision, the events and dates that impact this decision, and the contractual clauses relevant to this decision), and a formal response to a relevant party involved in the scenario, in this example, a letter to the client and member of the design team outlining an appropriate course of action.

Key References of the Report

‘Architectural Salary Guide | 9B Careers’. Accessed 16 December 2023. https://www.9bcareers.com/ careersupport/salary-guide.aspx.

GOV.UK. ‘Green Paper: Transforming Public Procurement’, 15 December 2020. https://www. gov.uk/government/consultations/green-papertransforming-public-procurement.

Highfield, Anna. ‘Who Pays the Most? Pay 100 Publishes Latest Salary Survey’. The Architects’ Journal (blog), 1 November 2023. https://www. architectsjournal.co.uk/news/who-pays-the-mostpay-100-publishes-latestsalarysurvey.

‘How Do Architects Calculate Their Fees’. Accessed 17 December 2023. https://www.architecture.com/ working-with-an-architect/how-do-i-calculate-anarchitects-fees.

‘What Does Our Business Benchmarking Report Tell Us about Architects’ Salaries’. Accessed 16 December 2023. https://jobs.architecture.com/ staticpages/10290/what-does-our-businessbenchmarking-report-tell-usaboutarchitects-salaries/.

Summary

Title // How Much Does an Architect Cost?

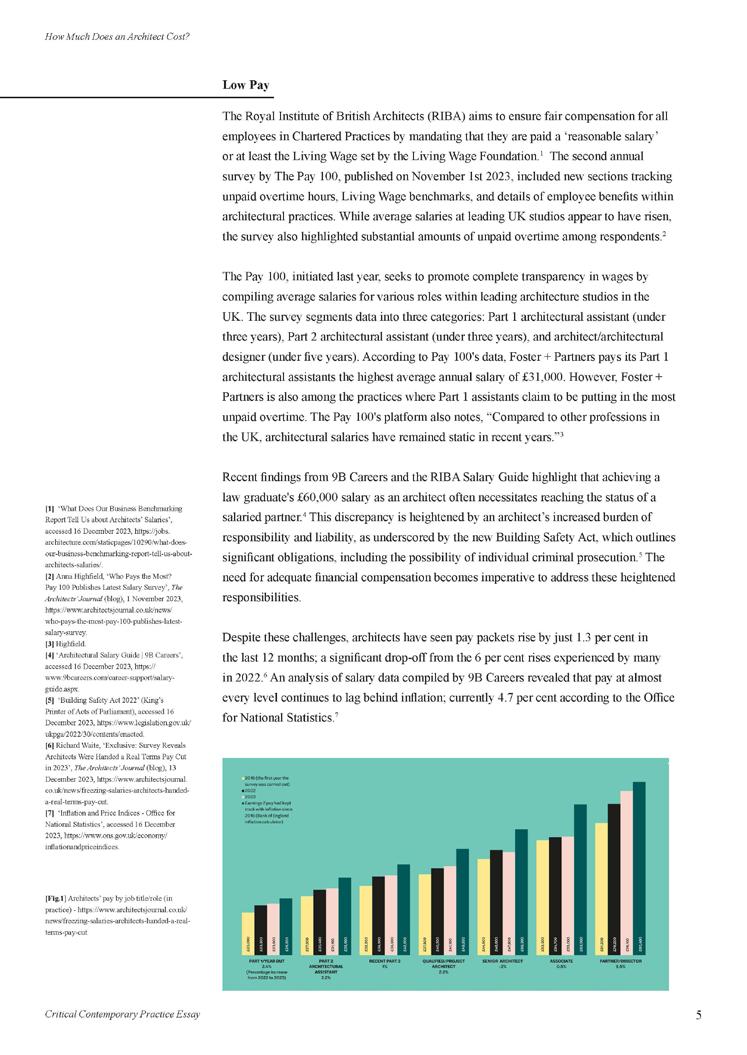

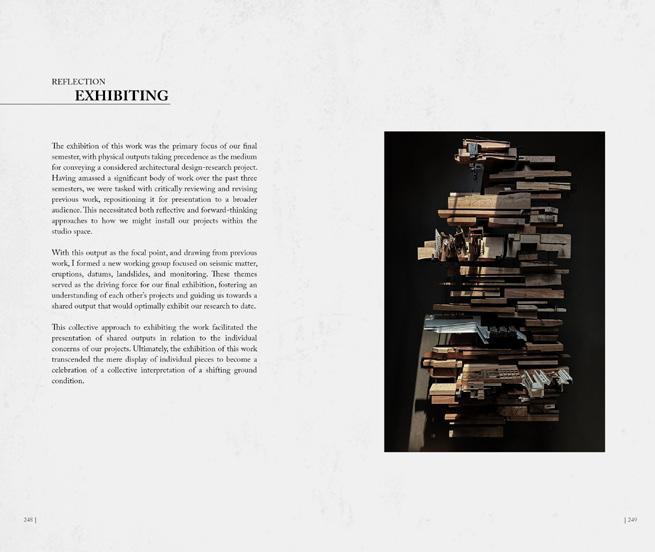

Question // Discuss the links between fees, work, and wages in the context of recent RIBA surveys (‘Future Trends Survey’, ‘Architectural Market Economics Report’, and so on) monitoring the state of the profession, and debates around the remuneration of architects.