Project Proposal Comprehensive Design Preparation

Fall 2024 | ARCH 808: Comprehensive Design Preparation

Spring 2025| ARCH 818: Architectural Design Studio 8

Introduction

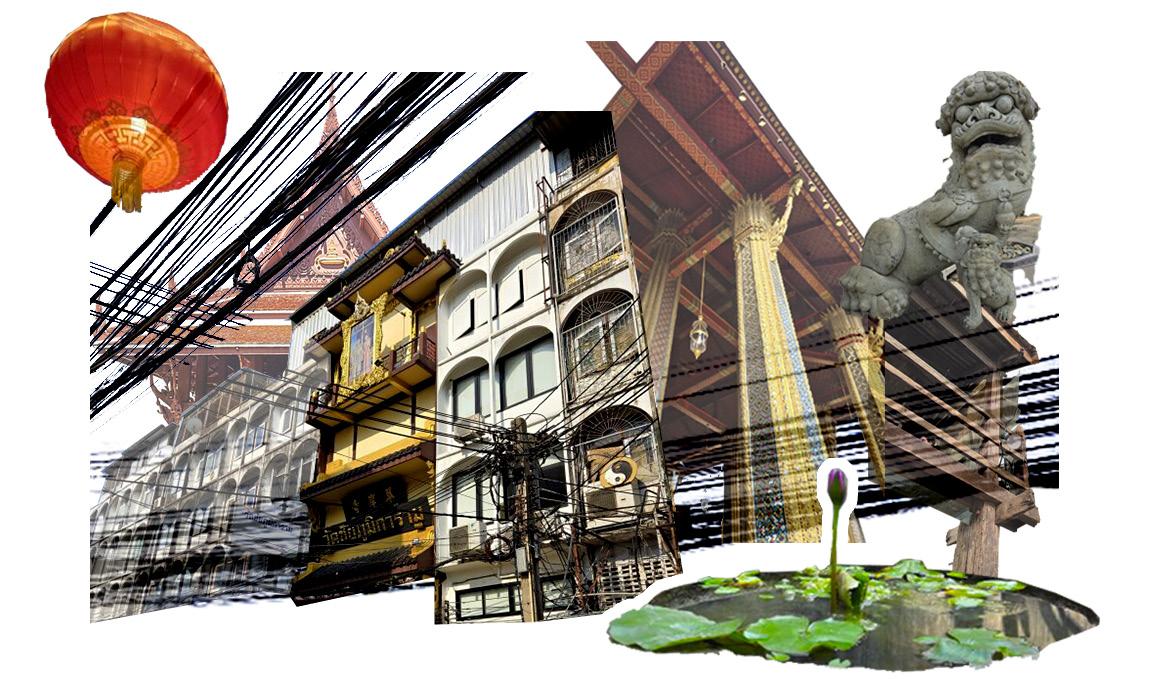

Yaowarat Road, the old China Town on the Chao Praya River, Bangkok, Thailand, is an area of intense shifts and changes. Chinese immigrants from the Southern part of China travel to Thailand by boat, and originally settled in the location of the Phra Borom Maha Ratcha Wang. Through several generations, the area has flexed and created a culture that embraces change and movement. Older generations owned shop houses where they and their children and families lived and worked together. Today, these spaces have been outgrown by families who have opted to move out of the cramped and often dirty spaces that served their purpose as shelter when they’re parents and grandparents first arrived to Bangkok.

Thai-Chinese descendants of immigrants, not using the homes they grew up in once they have outgrown them have begun leasing the spaces to larger businesses. These businesses have changed throughout the decades, through different “fads” and trends, often tearing down the urban and historical fabric of Yaowarat and its surrounding streets. This change, though resented by some, is seen as a natural way of life in Bangkok by others. Regardless, this gentrification of the area is erasing the historic roots and context of China Town and poses an immensely layered and complex situation for proposing a new building.

After careful deliberation, research and on site

interviews of locals, the program and site selection of the project came into fruition. The Resilient Futures Labs will house intimate research and wet laboratories to study the climate conditions, water, air, and soil qualities of the Bangkok area. The amphibious design of the labs addresses the extreme flooding conditions Bangkok faces today, and remains highly adaptable through structural additions for future needs.

The second portion of

The goal of this project is to embrace the younger generations moving into the area but holding space for the locals and their families with a new park on site designed around the Thai-Chinese youth that still reside there. A key facet to this is to not design for tourists, and to keep the chaotic urban fabric the area is known for (Fig 2).

Hybridizing

The ARCH818 Architectural Design Studio 8, I intend to design a laboratory that specializes in air, water, and soil quality research, as well as community engagement. Site B has been chosen to replace the current parking lot. The site will be re Breaking up the existing asphalt and re-greening the site will

be paramount to the design. The area is currently in a state of change since the COVID-19 virus, and is being revitalized by new offices, creative businesses, and inhabited by a younger population. I want to avoid contributing to potential gentrification of the area with the addition of public space that connects the river to China town, while making a space for citizens to pool, gather, and connect.

The intension of my design is to educate the new generation about sustainable design, and flood management and community contribution. Using cutting edge technology, the facility will collect data on water, air, and soil quality. The data taken can be used for several different disciplines and projects, such as conservation and climate monitoring, landuse planning, water management, pollution control, research development, agriculture, etc. This center will allow for climate related jobs, education opportunities, and begin future oriented research for Bangkok’s continuing climate crisis.

The research facility itself will be a case study in resilient design, promoting and creating healthier air and water passively through rain run off collection and filtration, and other researched tactics. The research center will engage in amphibious design, preparing for the worst future flood

scenarios. The center includes terraforming, amphibious stilt architecture, and amphibious floating architecture. There are several amphibious case studies that will be explored, including a home design in Bangkok. The community space will also play a part in flood management by learning from Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park as well as the Watersquare Benthemplein in the Netherlands. The public can engage with flood management infrastructure and learn from it.

The overarching goal of the project is to create a space that reengages with the flooding season culturally and in play, builds on an amphibious architectural model for a city that is actively sinking, and act itself as a case study in resilient architecture.

Precedent

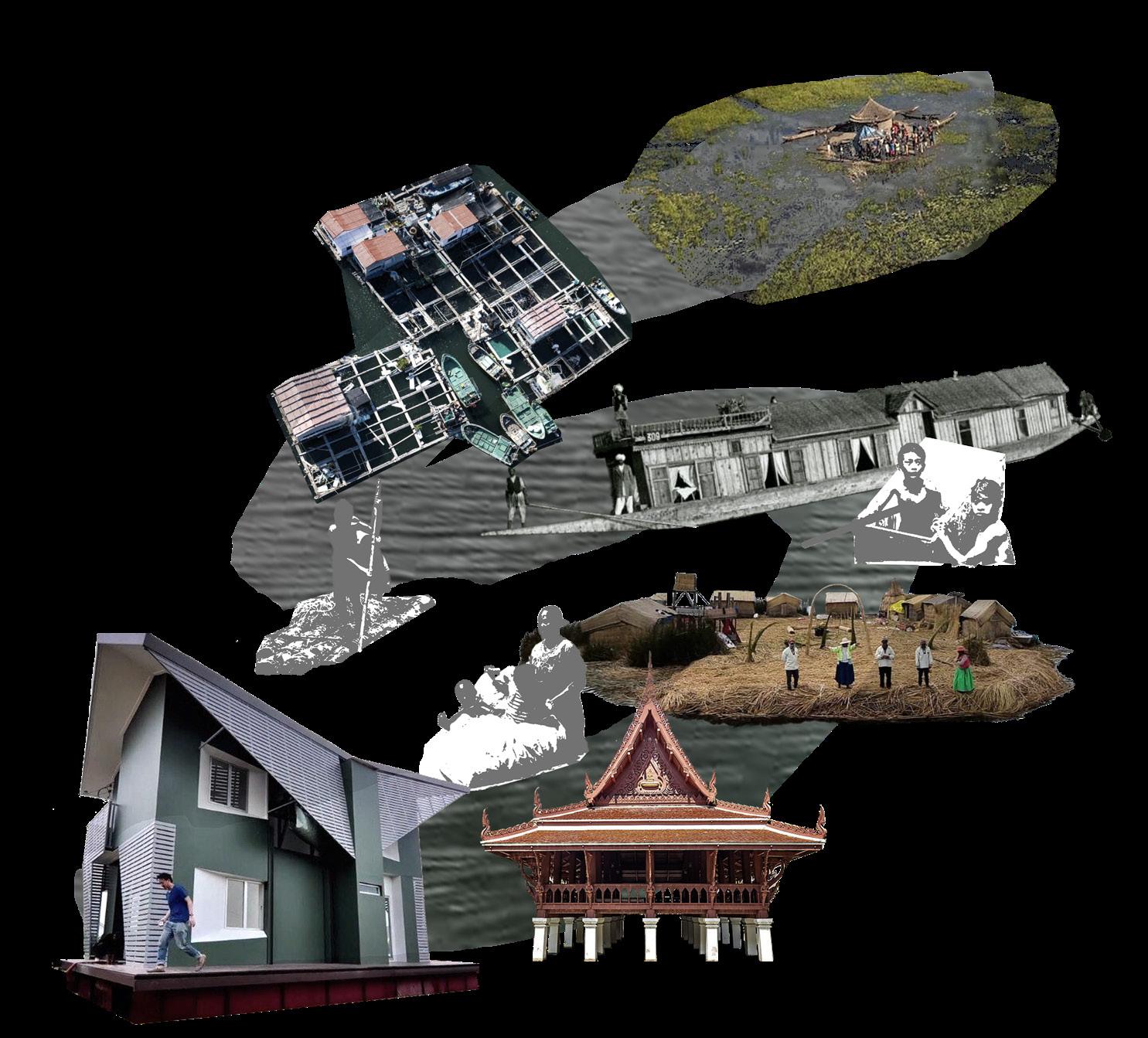

Many different precedents were studied as the project has several different layers. Figure 4 represents the different passive strategies communities have enacted around the world who are subject to flooding conditions. These communities are almost always forced into these areas as

refugees, annexed communities, or otherwise. The will to live and resilience they show through their adaptive strategies is both marvelous, and a testament to the human races ability to change. Through terraforming, creating floating structures on boats or recycled plastic containers, and stilt architecture, generations continue to live and build in some of the most dramatic climates and conditions. The final image, on the bottom right of Figure 4, is an amphibious home designed in Bangkok, Thailand to combat flooding conditions based on these passive models.

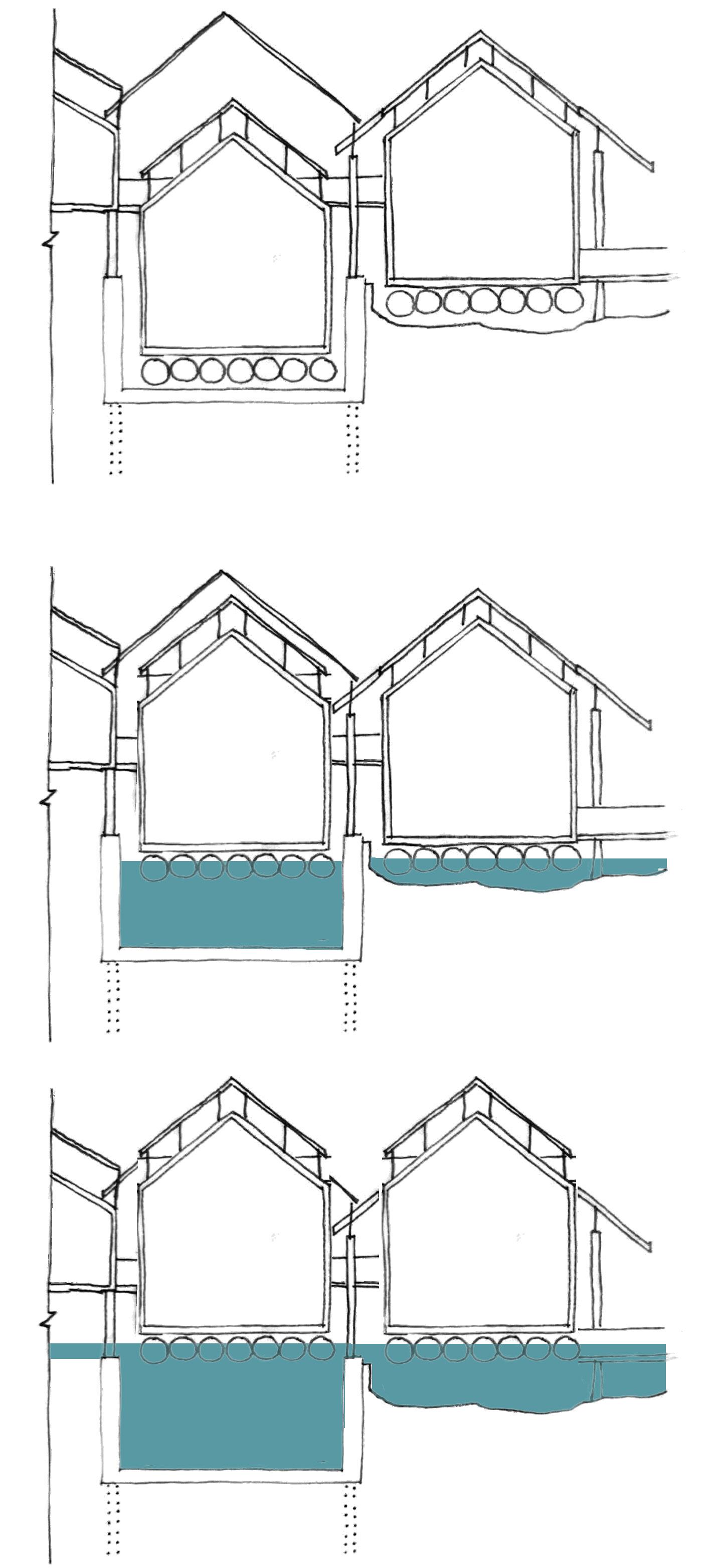

The Floating House Project by Chutayaves Sinthuphan (Fig 5) does exactly as it sounds, floats during a flooding crisis. This typology allows the building to sit on ground level and rise to an exact flood level instead of sit on stilts or flood altogether. The building sits in dug out pit , connecting to this foundation by a sub-frame system that contains large empty barrels to allow the home to float. Foundation piers act as “guide poles,” only allowing the structure to rise vertically.1 Not only does this model protect the individuals using the space from the elements, but it also protects the architecture, keeping costly 1 Saengpanya, P., and A. Kintarak. Thailand’s Floating House Project: Safe and Sustainable Living with Flooding. (International Journal of Engineering and Technology: 2019). 301-303.

repairs of extreme flooding events to a minimum.

The project aims to connect with the youth of China Town, Bangkok, through a public park. Instead of just a green space with benches that is mostly utilized by tourists, water management infrastructure will be designed as an amphitheater and sports field, much like the Benthemplein Water Square in Rotterdam, Netherlands (Fig 6).2 Scheduled events can take place in the space, but most of the time it will be open for public use. The younger generations in Bangkok, Thailand are experiencing green spaces in their city, and are one of the first generations in a long time to do so. This space will be dedicated to play and learning in their own neighborhood. Instead of traveling by public transit to a park, or a mall to gather with friends, they can share a space close to home.

Many other precedents of amphibious architecture were studied, including the Amphibious House by BACA Architects in the UK, The Lift House by Prithula Prosunin Dhaka, Bangladesh. The model of foundation, superstructure, and sub-structure will be adopted in this project.

The Design Process

After the research phase and the exploration of program and precedent, I began exploring what kinds of spaces were needed for the research facility, and what additional programs could be added to enhance community engagement. A portion of the building will be dedicated to an education and volunteer center to bring citizens and schools into the space and engage.

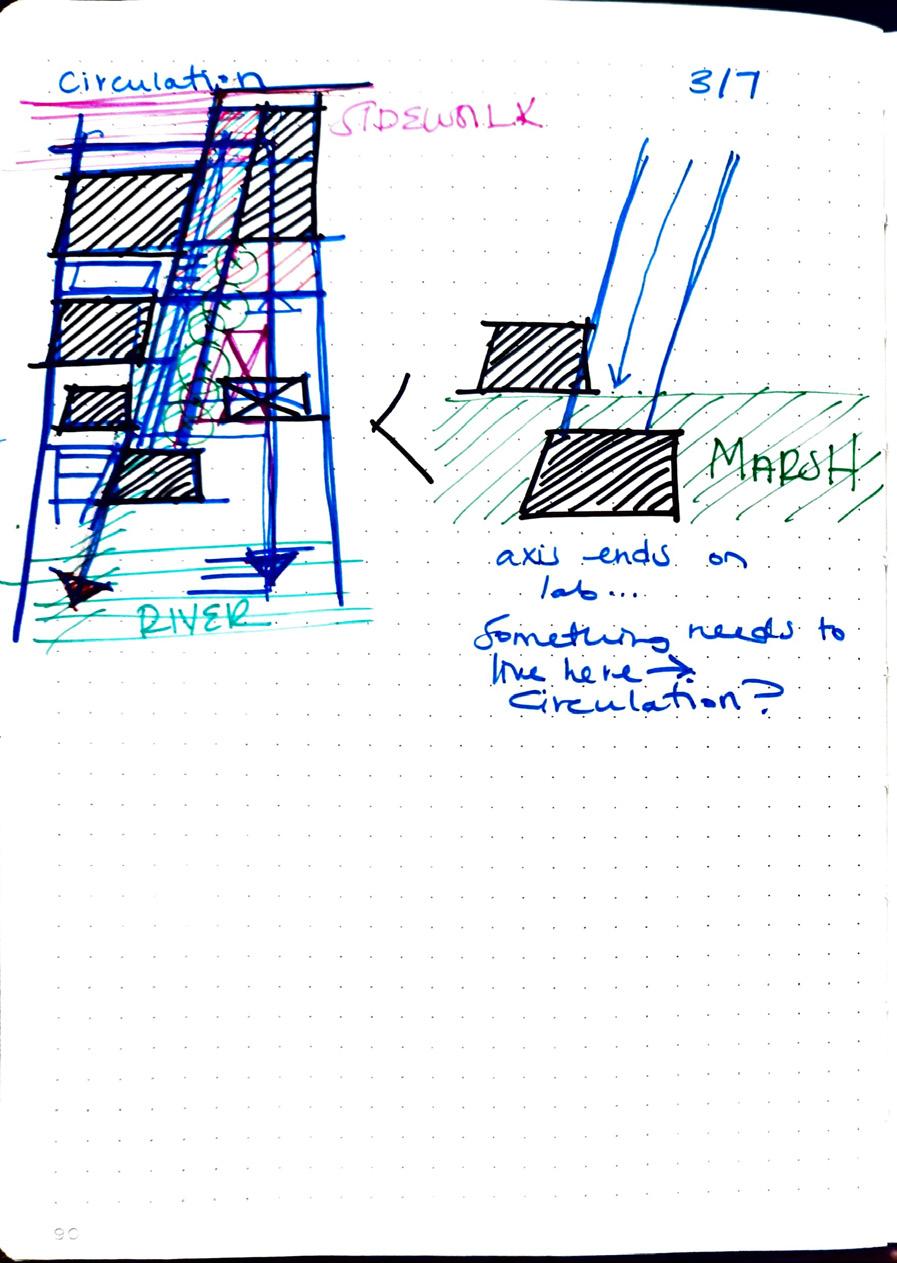

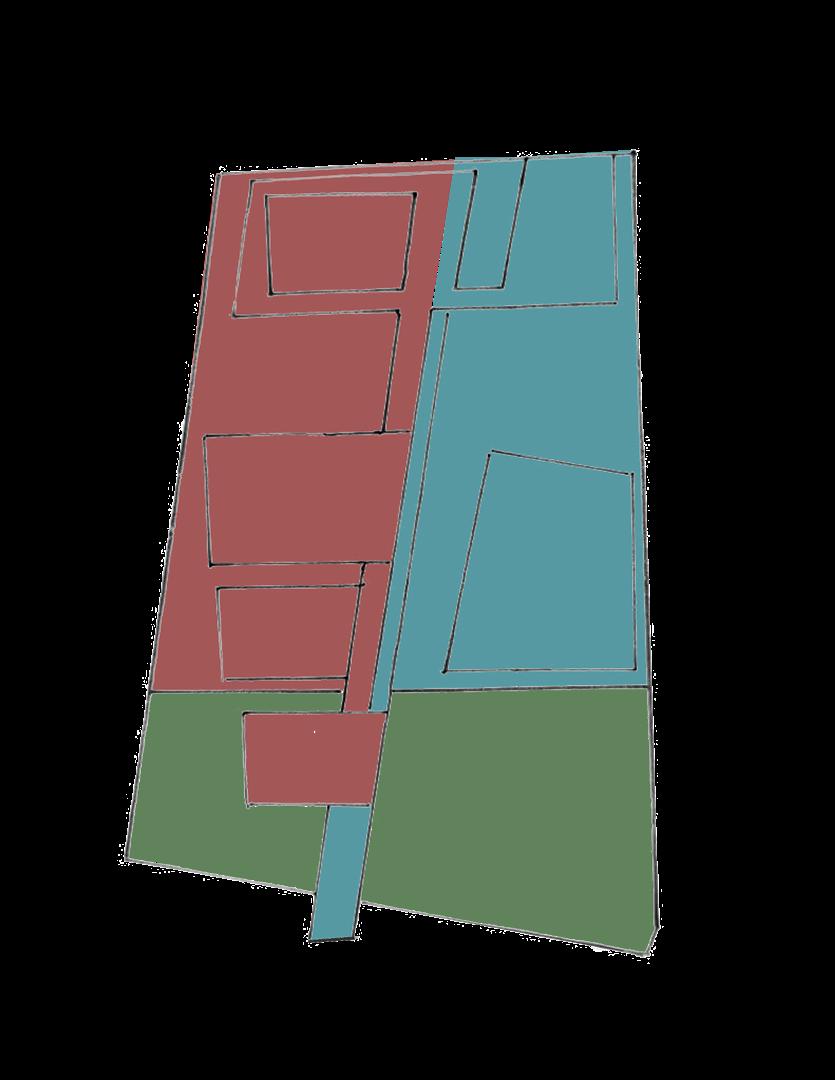

The site was designed to have a simple parti where public and private meet through at the circulation axis. The west of the site is for the laboratories and collaboration space, and the east side is for play and infrastructure. With a clear parti set, the organization of spaces began. Traditional Thai architecture was the focus of inspiration, and eventually, it was decided that programmatic pieces would be connected by exterior circulation, similar to Thai stilt communities. During this process, it was also decided that the laboratories would be stand-alone masses that slide within a super-structure system that upholds a roof and supports amphibious architectures. This secondary roof supported by the superstructure not only provides shade and protection from the elements but creates cohesion on the site, tying it together visually. The two labs closest to the Chaopraya River were chosen as the amphibious architecture, one sitting down one story into the earth and the other floating on a portion of the site dedicated to re-marshing.

Once the buildings were stilted and amphibious, allowing most of the site to be natural earth- the idea of terraforming and re-wilding came into play. Earth that is removed from the southern side of the side to re-wild the river’s edge will be used to create hills mid-site. This mimics the natural landscape of Thailand and makes the site seem as 2 DE URBANISTEN. Watersquare Benthemplein, Rotterdam. DE URBANISTEN. 1.

though it was found as is and built around. The site over time will grow, become wild, and ripe for study and play.

The next step was the urban edge, which was upheld to keep the street life of Bangkok. A large public entrance leads into the wild site, seen in passing. The east building has a different facade style from the west to mimic the urban fabric of China Town’s streets and the rhythm of buildings. The program of this building also stands alone as the hub for administration, support staff, and the community outreach office.

Design Strategies

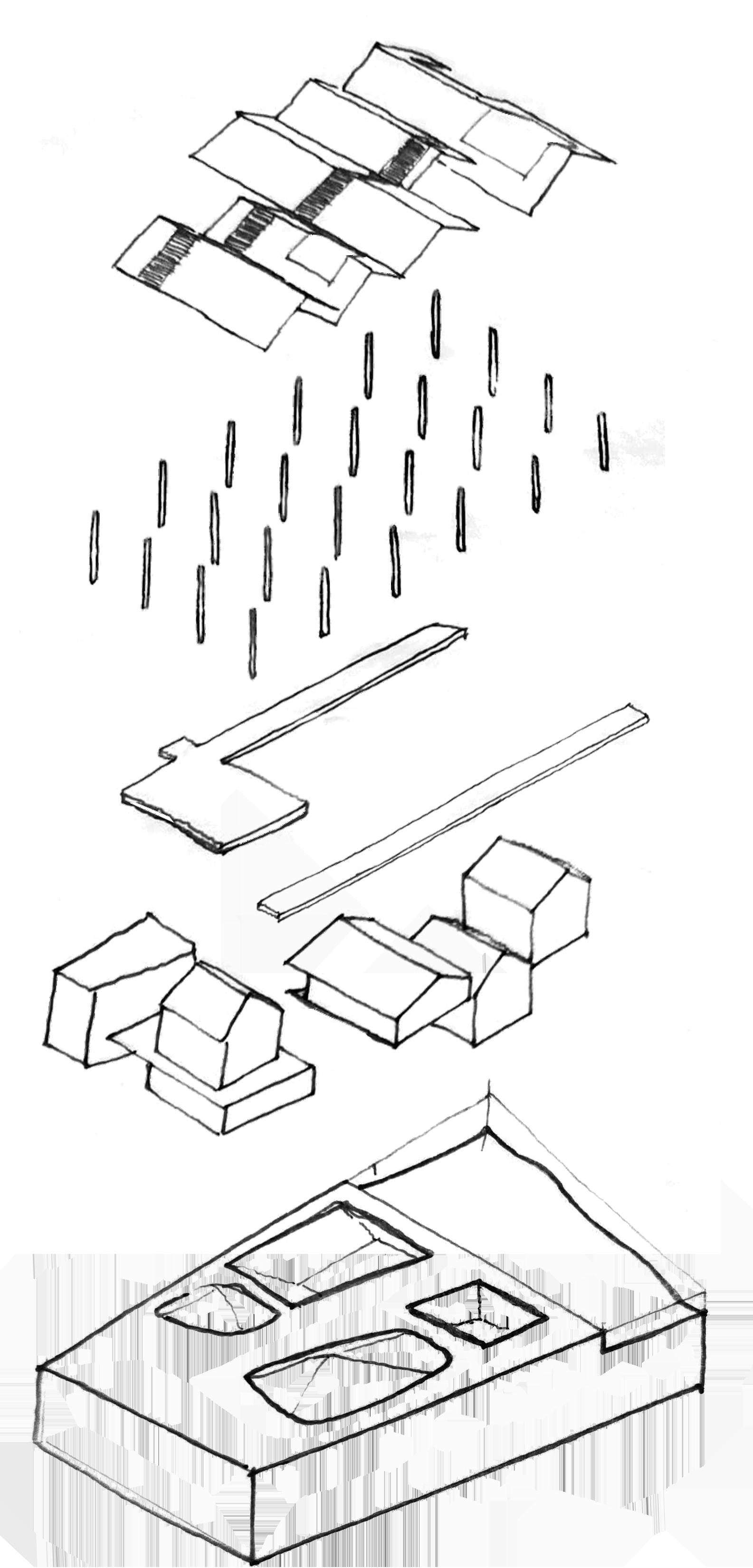

The first priority was establishing a regular grid for a post and beam structural system. Because of the hierarchal levels of structure, simplicity would serve the project best. A super structural grid was chosen based on span, but also the size of spaces in-between. The sub-frames for the amphibious components would nest inside. To tie the project together, a large pitched roof system would span the entire site, connecting the grid and nested structures together as one whole. The system would also provide much needed shade and protection from elements.

It was natural to design the rest of the components needed as a nested, layered system. The layers are as follows: roof, structure, connection (circulation), massing (nested structures), and ground plane. Two walkways lead the user through the site, creating a strong central axis on which public and private functions meet. The top walkway is primarily used for those working at the laboratory, while the second and lower walking is used for the public, leading directly out onto the water.

The inserted massings are all functional components of the laboratories, administration, and services. The organization of space, and open-air connections calls back to traditional Thai architecture, celebrating community and connection. The collaboration center is set on stilts, while the two laboratories on the back end of the site are amphibious. The urban edge of the site is held with concrete based buildings to resist flooding damage. All important program is set above on the second level to prevent damage during extreme flooding events.

The existing parking lot is broken up, and re-greened. This allowed for terraforming, creating a miniature rolling landscape. The back one-fourth of the site, connecting to the Chaopraya River, is returned to marshland, acting as an educational opportunity, flood management, biodiversity inducer, and an active area of study for those working in the laboratory. The rest of the site is open and usable but left natural. Natural material pathways lead to the amphitheater, encouraging exploration and play.

The amphitheater connects to the marshland, promoting flood waters to collect and pool in this space instead of spreading over the site. When this space floods, a water pump connects it back to the amphibious architecture, allowing water to travel to the amphibious foundation and be retains here as well. As this foundation itself floods, the

building will rise, guided by the substructure that ties to its foundation. The laboratory on the marsh is also amphibious, and will float when flooding is extreme, acting as a warning that if flooding continues the rest of the site may be in jeopardy. When extreme flooding events occur, and inevitably the entire site floods, and exposed earth and infrastructure will protect the architecture, leading to minimal repair and rebuild costs.

The site will be planted with local species, specifically Banyan trees at the north of the site, and in the marsh Mangrove trees. Both of these species are native to the location and will aid in shading, biodiversity, ecosystem rehabilitation, and water management.

The site connects to the complex culture of China Town through the act of work. The people of China Town, mostly immigrants, pride themselves on their work ethic and dedication to providing for their family. The addition of laboratories and green jobs plugs into the environment seamlessly, while also acting as inspiration to the youth. The circulation axis combines scientists and users, allowing glimpses into each others worlds.

The next phases of design will focus on no major design changes, but on refinements of design. The main goals of refinement include the roof structure and connection points being simplified, the marsh and infrastructure connection line being softened and made natural, and the interior space floor plants being streamlined and improved. The shown drawings and diagrams will also be updated and improved in preparation for the final review.

Along with the existing design refinements, the exploration of wall section and site section at amphibious architecture and water infrastructure will be developed, focusing on efficiency and also maintenance access. Materialization and facade will be developed and will still draw from both traditional and contemporary Thai design. Finally, on ground water drainage routes will be designed to lure water off of the site and back to the marsh and river, directing potential flood waters coming from the north through the site safely.

The Mid-Crit

On March 24, 2025, the project received feedback during the mid-crit review. Preceding onward, the project will focus on the structural detail of the amphibious architecture and the super and sub-structural connections. The landscape and marsh were also explored, and with good intention, would at its current design cause more flooding on site than help. Softening its edges near the river’s edge and the water infrastructure will help guide rain and flooding waters to the allocated locations. The cultural connection also needs to be better included and tied more to the narrative. What makes this culturally appropriate and significant? The next phase of design will consist of these main take aways from the mid-crit review, as well as further develop all other aspects of design.

References

Saengpanya, P., and A. Kintarak. “Thailand’s Floating House Project: Safe and Sustainable Living with Flooding.” International Journal of Engineering and Technology 11, no. 5 (N.D..): 299–304.

“Watersquare Benthemplein, Rotterdam.” DE URBANISTEN. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://www.urbanisten.nl/ work/benthemplein.

Figures

1 Corin Afzal, Changing Spirit, 2025, collage.

2 Corin Afzal, China Town, Bangkok, Feb. 2 2025, photography, Bangkok, Thailand.

3 Corin Afzal, Site B, Mar. 26 2025, Adobe Illustrator and Google Earth.

4 Corin Afzal, Resilience in Flooding Waters, Mar. 20 2025, collage.

5

Site-Specific Co Ltd., The Amphibious House, photograph, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/ article/business/environment/Thailand-testsfloating-homes-in-region-grappling-withfloods-idUSKBN0M100M/

6 DE URBANISTEN, Water Square Benthemplein, https://www.urbanisten.nl/work/benthemplein

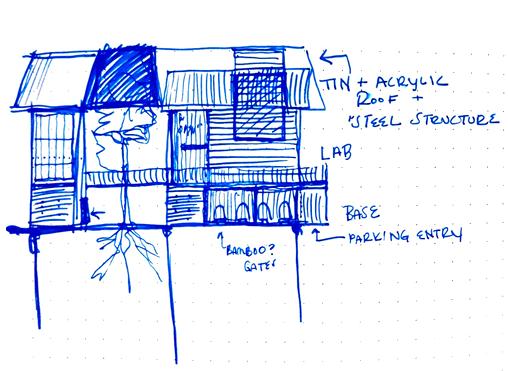

7 Corin Afzal, Sketchbook, Mar. 7 2025, marker and notebook.

8 Corin Afzal, Parti diagram, March 20 2025, Adobe Illustrator.

9 Corin Afzal, Sketchbook, Mar. 7 2025, marker and notebook.

10 Corin Afzal, Exploded Axonometric, Mar. 21 2025, marker and trace.

11 Corin Afzal, Amphibious Diagram, Mar. 21 2025, marker and trace.

12 Corin Afzal, Mid-Crit Site Section, Mar. 19 2025, Rhino 7 and Adobe Illustrator.

13 Corin Afzal, Identity & Authenticity, Mar. 29 2025, collage.