THE SCULPTURAL THREAD

AN EXPLORATION OF TECTONIC SCULPTURALISM

CORIN AFZAL KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY

© 2024 Corin Afzal, Kansas State University

All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the copyright owner. This document was generated for educational purposes and not for profit. It is not for distribution outside of fulfilling the educational requirements of assigned coursework and the author’s personal use. Every e ort has been made to properly cite all source material.

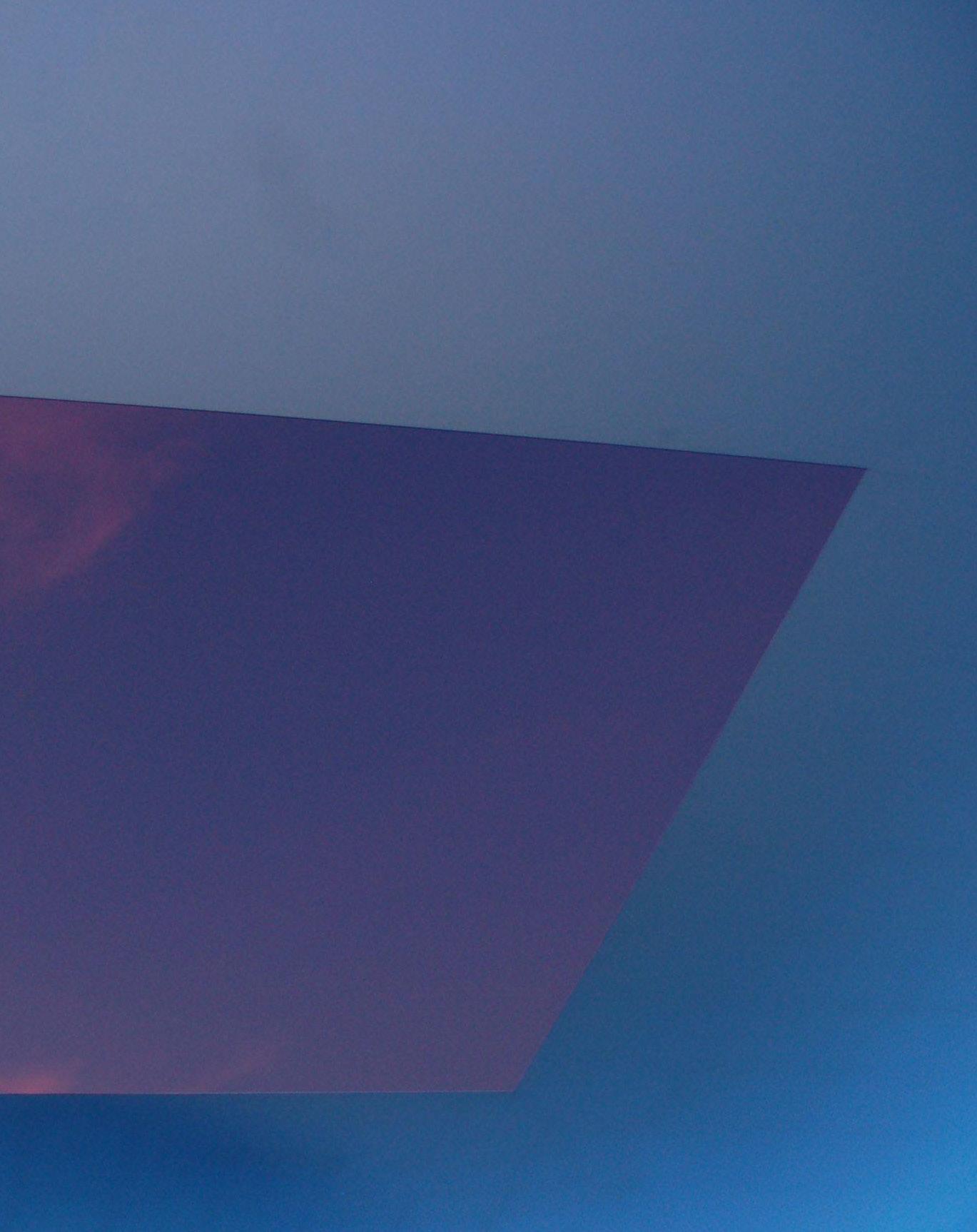

Fig. 1 Not Vital’s House to watch the sunset

THE SCULPTURAL THREAD

AN EXPLORATION OF TECTONIC SCULPTURALISM

Fig. 1 Not Vital’s House to watch the sunset

INTRODUCTION

The collection of buildings in this booklet demonstrate the power of sculptural techniques in architectural design to create complex and engaging spaces. The collection, along with the to be designed entrance building, creates a di erent narrative about sculptural architecture than what has predominantly studiedsculptural for the sake of being sculptural, a topic that has shifted minimally since the Post-Modern movement. Instead of structure supporting sculptural elements, the following nine buildings, pavilions, and sculptures express their concepts through their self supporting structure. Through the language of tectonics, the nine pieces’ concepts are pushed past general aesthetics and into the architectural realm of funtionality. The process of creating architecture is in of itself a sculptural act, and the connection of architecture to the fine arts can supply the designer with a wealth of information.

The rise of Sculpturalism in California in the midst of the Post-Modern movement has dominated the conversation about sculptural architecture.1 One conjures images of the famous Frank Gehry, and his architecture that directly opposed the mass production and sometimes sterile environments of modernism. The sculptural forms often have required their own structural systems to carry their weight. These architectures, like those found in the modern movement, often lacked a sense of connection to place and meaning, like that of the modern and post-modern sculptural scenes happening right beside them.2 The Sculptural Thread is proposing a group of works that are all from the contemporary period, the 2000s-2010s besides one project by architect and sculptor Sol LeWitt from 1979, but whose work is itself is timeless.

The Sculptural Threads entry building will provide a place for all to learn and experience what sculptural works of architecture can bring to our daily lives, on the sculptural, pavilion, and building scale. The collection of buildings and museum of information will provide a di erent definition of sculptural architecture, one that celebrates tectonic sculpturalism.

THE LENS OF SCULPTURE

When creating a work of sculpture or architecture, there is always a concept and an intent to be interpretted by an audience. There are three e ects that the creator can use to facilitate their concept (see Fig. 1). Though in the case of architecture several di erent spaces in one project may be aiming for a di erent e ect on the individual depending on many factors. A space could call for projection onto the environment around the viewer, placing emphasis not on the person or the object, but the non-person and non-object. Projection onto self is exactly what it implies, a space or work creates a concentrated self awareness of the person, being mostly felt in the mental capacity. Think of works of art or buildings that lead the person to ideate and introspect. Awareness of the self in the environment is both of these combined. The person becomes aware of themselves in the environment, whether it be through movement, compression, or other.

The collection of buildings in The Sculptural Thread explores sculpture, pavilion, and buildings that through design have a di erent desired e ect on the user. How each e ect is executed is explored through three techniques of sculptural design: abstraction, gesture, and immersion (see Fig. 2). Each technique is discussed through a sculpture, a pavilion, and finally a building that will all be connected together, tied together by a thread of discourse.

PROJECTION ONTO ENVIRONMENT

PROJECTION ONTO SELF AWARENESS OF SELF IN ENVIRONMENT

Fig. 2 The Three Effects of Created Space in Sculpture and Architecture

The Scultpural Thread entry building will be designed through this same sculptural lens, borrowing from all three subjects and will express itself tectonically and through structure. Acting itself as a museum, guests to the park will begin their journey in the grand space, gain information, meet each others friends and family in a gathering space, and take respite in a space that it self is a work of sculpture, like the buildings it preludes on the open air museum journey.

Many of the projects being studied for the design on the open air museum entry building contain other techniques and e ects on the users of the building. For the focus of this study, the dominating technique and following e ect will be examined and diagrammed. The goal is not to categorize each work and argue a certain technique, but to discuss the importance of sculpture as a lens of design. The sculpture and his goals easily align with the architect, and vice versa.

Fig. 3 Three Sculptural Design Techniques GESTURE ABSTRACTION IMMERSION

THE LANGUAGE OF TECTONICS

The subject of tectonics and the language of construction began in the early 1800s, and through this still relevant design strategy is a key asset to studying the group of buildings in The Sculptural Thread. The nine selected buildings, pavilions, and sculptures were selected to be displayed in the open air museum because of their alignment with principles of architectural tectonics.3 It is important for the building’s tectonic expression to align with narrative and not allow symbols in design to predetermine a spaces interpretation by the user.4 The sculptural aspect, no matter the technique, is accentuated if not fully realized through the tectonics of the buildings.

According to Schwartz, there are ten principles of architectural tectonics: precedent, place, anatomy, materiality, construction, representation, ornament, detail, space, and atectonic.5 The latter being a design that does not follow tectonic theory, not expressing the way it was constructed. The ten principles reminds the designer that tectonics lives outside of merely just the detail. It is also the reaction to the site, and the arrangement and distribution of di erent kinds of spaces, and how each part no matter the scale interacts or vice versa. It is important that through the design of material, connections, and joinery, and their individual expression6 that there is an invitation for the viewer to theorize about reasoning, and not to be boxed into aesthetic admirations.7 The intentional articulation of di erences between materials and connections is found in successful architecture.

Wiszniewski describes architecture as language through its use of symbols. “Tectonics are the very mechanics of meaning.”8 All buildings start as drawings, and predetermined terms. There are several di erent ways of reading buildings designed with tectonics in mind, and makes the user think and ponder the small details of the whole. Buildings designed to promote symbolism are flat when analyzed, and lead to little user interaction.

Theory itself is revealed through tectonics, after a building is completed and it is analyzed. Through intentional design, architectural tectonics, like individual brush strokes in painting, will be interpreted on di erent levels by di erent critiques. In this way, Wiszniewski suggests that tectonics is not only the language of construction, but in construction.9

Fig. 4 Courtesy of Nuno Borges. “The Twist.”

SITE CONSTRUCTION

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

MARKED SITES AXIOMATIC STRUCTURES

ART

NOT LANDSCAPE NOT ARCHITECTURE

SCULPTURE

Fig. 5 (left) Rosalind Krauss’ theory of neuter, proving architecture to be an artform, removing sculpture as the base of discussion

SITE CONSTRUCTION

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

MARKED SITES AXIOMATIC STRUCTURES

SCULPTURE

NOT LANDSCAPE NOT ARCHITECTURE

FINE ART

6 (right) Rosalind Krauss’ theory applied to the contemporary time and attitude towards architecture and sculpture

Fig.

ARCHITECTURE AS SCULPTURE & GALLERY

The display of objects in museums and galleries in our modern era has evolved into being inherently architectural.10 Whether a display is in one space, through several rooms, or on di erent sides of a site, the space itself becomes a language in which to push the narrative of the objects connection further. Before this, galleries had evolved in several di erent directions, displaying works of art crowded in one large forum, to the more traditional form historic museums take displaying by location and date. In contemporary times the narrative of gallery design has been pushed into many di erent directions. One sculpture in a large white room, to objects obstructing pathways and molding the space. The rooms that shape these spaces are no longer though of as long halls, but moldable in their own way. Thus the architect designing the gallery takes on a similar role to the curator designing the show.11

In her essay, Sculpture in the Expanded Field, Rosalind Krauss suggests that architecture and sculpture are separate things under the umbrella of art (see Fig. 3).12 This was a reaction to the modernist movement and what sculpture had become, but was still significant because of her determining architecture was an art. She wanted to defrenciate architecture from sculpture, saying the two were complately di erent modes.13

Objects, performances, and strange immersive experiences soon came under the label “sculpture” because there was no other term they could be categorized under.14 During the post-modern movement, this trend continued. It felt for a moment like the word sculpture itself would completely collapse. Opening the term up to architecture seemed like too large of an ask. In the contemporary era, however, this wide range of works under the term sculpture still exists and has not collapsed at all. Many architects self-describe their buildings as sculptures. The term archisculpture has risen to describe the post-modern sculpture obsession15, as well as Sculpturalism16. These movements, once again, are aligned with the post-modern, and often describe works that require additional structure to support their sculptursl qualities. The Sculptural Thread would like to bring sculpture and its semantics back into the center of conversation, and view architecture through its lens directly (see Fig 4). The Sculptural Thread proposes that the gallery and museum are architectural and that architecture that engages with tectonics is sculptural.

SCULPTURAL THREAD PROGRAM

PUBLIC HALL

MUSEUM

MUSEUM COLLECTIONS

LOBBY SPACE

GALLERIES

EXHIBITION LOBBY

STORAGE

MUTIPURPOSE ROOM

VENUE

STORAGE

CAFE

CATERING KITCHEN OFFICE

OPEN SEATING FOOD STORAGE

OUTDOOR SEATING

OFFICES

CONFERENCE ROOM

CONSERVATION LAB

OPEN OFFICE

LIBRARY

BREAKROOM

STORAGE

LOBBY

EXECUTIVE OFFICES (3)

SUPPORT

MECHANICAL

LOADING DOCK

RESTROOMS

SITE MAINTENANCE

BUILDING MAINTENANCE

ELECTRICAL

JANITORIAL

Fig. 7 Programmatic Needs and their Square Footage

The Sculptural Thread’s museum will contain a permenant collectionof drawings, items, and information pertaining to the nine collection buildings to be discussed in this booklet. The main public hall that connects the parking lot entry to the open air museum will contain this information for visitors to obtain knowledge before experience the buildings, pavilions, and sculptures ahead.

The gallery space will be currated by a sta who’s main goal will be to bring in artists and architects who practice tectonic sculpturalism in their works. The venue space will be used for lectures from said artists, as well as events and fundraisers. The attached cafe’s kitchen will be equipped for event catering as well as the daily customers it will serve.

The Sculptural Thread’s entry building will also house most of the sta , including administration, a curator and their team, and conservationists. The conservationists will have a lab dedicateted to their work of upkeeping the collection onsite and any items that are in the museum’s possession.

Two of the collection’s buildings are functional galleries, and are intended to remain in full operation. There will be other sta that functions out of those buildings, hosting a wider array of artworks than the Sculptural Thread’s focus on sculpture and architecture. These buildings will be either located in close proximity to the entry building in the site design phase or have their own dedicated parking.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS

DESCRIPTION

THE PERMANENT COLLECTION DESCRIBING THE NINE BUILDINGS, PAVILIONS, AND SCULPTURES AND THEIR ARCHITECTS IN THE OPEN AIR MUSEUM’S COLLECTION.

A STORAGE SPACE FOR THE PERMANENT COLLECTION AND DONATIONS

TWO VESTIBULES AND AN ENTRY DESK TO GREET GUESTS AND OFFER INFORMATION

TEMPORARY EXHIBITION FOR ARCHITECTS AND ARTISTS WORKS

STORAGE FOR TEMPORARY ARTWORKS

ENTRY DESK AND PROPERTY DROP OFF

ROOM FOR SPEAKING ENGAGEMENTS, EVENTS, AND GALLERY OPENINGS

STORAGE FOR TABLES, CHAIRS, AND OTHER MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS

SEATING ATTACHED TO THE CAFE AND BOOKSTORE, OPEN VIEWS ONTO THE SITE.

OUTDOOR SEATING ATTACHED TO THE OPEN SEATING, OPEN VIEWS ONTO THE OUTDOOR EXHIBITION

DESCRIPTION

FULLY EQUIPPED INDUSTRIAL KITCHEN TO BE USED BY THE CAFE, AND FOR CATERING STAFF DURING EVENTS

FOR USE OF CAFE STAFF

FREEZER AND DRY STORAGE

PERSONAL OFFICE FOR THE ADMINISTRATION LEAD

PERSONAL OFFICE FOR THE GALLERY CURATOR

PERSONAL OFFICE FOR THE LEAD CONSERVATIONIST

OPEN FLOOR PLAN SEATING FOR EMPLOYEES

LABORATORY USED TO MAINTAIN MUSEUM AND BUILDING COLLECTION PIECES

COLLECTION OF BOOKS FOR THE USE OF EMPLOYEES RESEARCH

SPACE FOR MEETINGS

FRONT DESK FOR GREETING GUESTS

SPACE FOR BREAKS OR LARGE WORK SPACE NEEDS

OFFICE STORAGE NEEDS

PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS

PROGRAM SFTQFT

SUPPORT SPACES

DESCRIPTION

DOCK FOR ARTWORK AND FOOD DELIVERIES

STORAGE FOR ELECTRICAL EQUIPMENT

STORAGE FOR UTILITIES EQUIPMENT

STORAGE FOR JANITORIAL STORAGE & MOP SINK

STORAGE FOR MAIN BUILDING MAINTENENCE

STORAGE FOR SITE CARE EQUIPMENT

RESTROOMS FOR UP TO 300 GUESTS NET TOTAL

GROSS TOTAL

SQF

PRIMARY SPACE

SECONDARY SPACE

SUPPORT SPACE

OPEN CIRCULATION

CIRCULATION CONNECTION

VIEWS TO OUTDOORS, NATURAL LIGHTING

ENCLOSED SPACE, INDIRECT NATURAL LIGHTING

Fig. 8 Programmatic Adjacencies

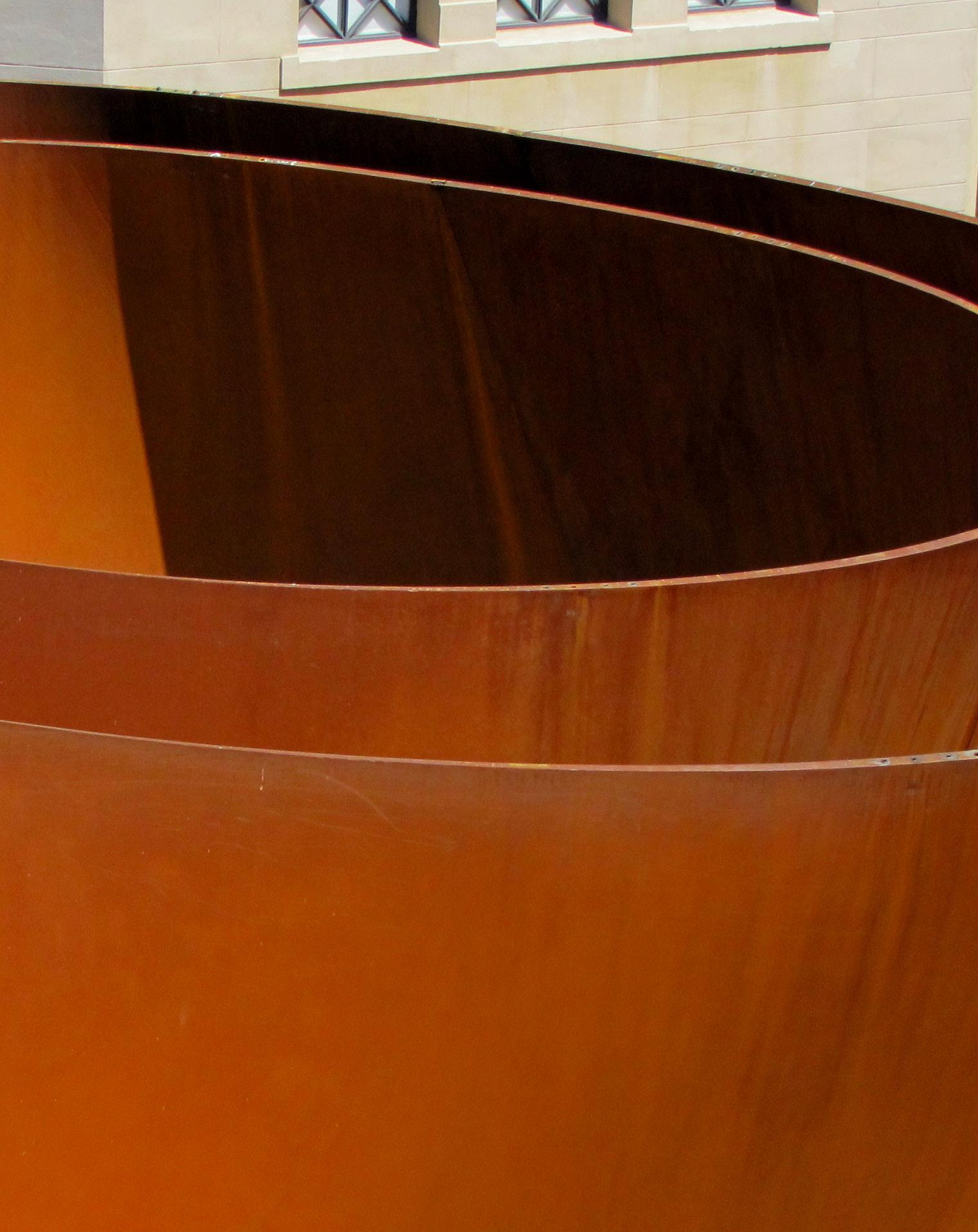

RICHARD SERRA SECTION 1:32

SEQUENCE

ELEVATION PLAN

Sequence is said to be one of Richard Serra’s greatest acheivements. The sculpture consists of twleve manipulated steel plates at the height of thirteen feet and weighing twohundred and thirty five tons. It is located for a longterm viewing at Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, California.17

“Sequence, is two torqued ellipses connected by an S. The S is the passage that reverses itself right in the center of the piece. And you might have the concern that you’re walking back in the same direction that you came from. But you’re not.”18

-Richard Serra

Sequence was not created to teach or lead the user to anything in particular, it is the thoughts that one has while engaging the project that creates a “private participation.”19 This sculpture, along with many others by Serra, is inherently architectural. The circulation experience pulls users inside, and guides them physically to its centers and outwards while their experience is molded by their individual thoughts.

A fantastical environment can initiate an inner experience, and is what the architect strives for, no matter the scale or concept.

GESTURE

SPATIAL AND SELF AWARENESS

WELDED CONNECTION

Fig. 9 Courtesy of Rob Corder. Detail of Richard Serra’s Sequence

ELEVATION 1:32

ELEVATION

SERPENTINE PAVILION

JUNYA ISHIGAMI

PLAN

Junya Ishigami was invited to design a 2019 Serpentine Pavilion because of his design based in the ideas of harmony with nature and the man made environment, and natural phenomena.20

The pavilion was made by individually arranging slabs of slate into a canopy roof that enclosed the interior like a “cave.” The slate visually has a weight, appearing to grow out of the lawn, until one circles around and sees the interior. The thin layer of slate upheld by thin columns appears so light it could fall over in the breeze. The rocks then almost appear to have the consistency of a fabric tarp inflating to create the interior.21

The use of traditional roof tiling with the sculptural organic form contrast with the space underneath, which uses modern methods of structure and material realization. Ishigami and his designs aim to balance the “man made” with surrounding landscape and natural materials used in modern construction. 22

The concept of pavilion has long lived at the centerline of architecture and art, using the medium of our built environments to express ideals that are not so easily incorporated into funtional buildings. The Serpentine Pavilion is a wonderful example of a pavilion truly centering itself between landart and architecture.

GESTURE

COMPRESSION & MATERIAL MANIPULATION

SLATE STEEL MATERIALITY

Fig. 10 Courtesy of Ste Murray. Junya Ishigami’s Serpentine Pavilion.

EAST ELEVATION

SECOND FLOOR PLAN

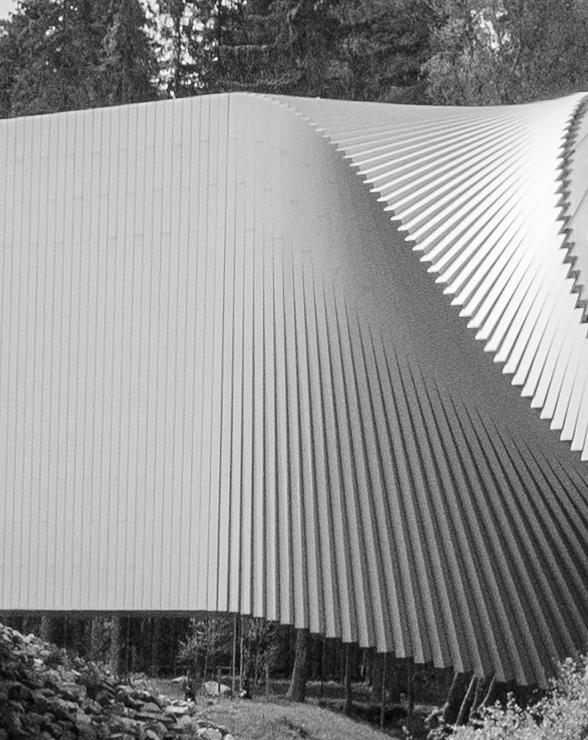

THE TWIST BJARKE INGLES GROUP

The Twist was finished in 2019 and is located in Kistefos Sculpture Park, one hour outside of Oslo, Norway. The building is described to be a “beam” and bends at ninety degrees and crosses the Randselva River, acting as building, bridge, and sculpture in one.23

Bjarke Ingels Group was invited to design the gallery to add indoor exhibition space to the sculpture park, and after careful study of the site, the team proposed the building bridges across the river to bring natural circulation throughout the park.24

The sculptural form twists and propels the user through, over the river, through a gallery space, and to the other side of the river to continue through the park installations. The museum itself is an abstract shape juxtaposed with the landscape. The double height space from the south entry houses a huge warping structure, while the north entrance uses simple bridge technology.25

GESTURE

EXPERIENCE

SCULPTURAL FORM TECTONIC TRANSLATION SCULPTURAL STRUCTURE

Fig. 11 Courtesy of Astrid Westvang. The Twist’s ninety degree turn over the river below.

SECTION 1:32

ELEVATION

PLAN

ONE, TWO, THREE SOL LEWITT

LeWitt’s work is said to be highly conceptual and deals with seriality. His sculptures adhere to a strict rule set that determine the finished works appearance, much like the structure of a building. These rules have adjusted and broken throughout his sculptural lifetime, creating a dialog between his works. Sol LeWitt’s nonsculptural works also deal in rules and the individual following them, such as instructions for a wall painting that a gallery must perform themselves.

LeWitt’s sculptures are tied to his architectural past, creating space frames that uphold not a building but a construct and interpretation of space. His sculptures at this scale are in dialog with not only the environment, but with the pedestrian. There is an awareness of space taken by sculpture, surrounding architecturs, and the person inbetween them.

One, Two, Three was created as a commission for the General Services Administration’s Art-Architecture Program to enrich federal buildings and their communities.26 The three groups of cubes are connected by a central axis.27

The use of abstraction is clear in Sol LeWitt’s work. He takes the architectural language of structure and subtracts it to its simplest form and span. Noteably, he hides any connections to appear simplistic, when in reality these joints are more complex under their wrappings.

ABSTRACTION

PROJECTION ONTO SELF

MULTIPLICATION ALONG AXIS

Fig. 12 Courtesy of . Detail of Sol LeWitt’s One, Two, Three.

HOUSE TO WATCH THE SUNSET NOT VITAL SECTION 1:32

Not Vital coined his works as between sculpture and architecture, “SCARCH.”28 They are not at all practical, and live in a realm of poetics. His work truly encapsulates the language of tectonics, and with this language Not Vital writes poetry.

House to Watch the Sunset was conceived during his time staying in Niger, Africa. After a sunset walk, he exclaimed he would build a house for watching the beautiful sunsets he experienced there.29 These homes are now built in di erent locations, all for the same purpose, one being in Niger, and another in the Swiss Alps (See Fig. 12).

Each inhabitable sculpture is built at the exact same dimensions and layout. The building is oriented according to the suns path onsite. Depending on the location, di erent materials are used to better suit the climate and local surroundings. 30

Not Vital’s SCARCH is a wonderful example of the abstraction and simplification of architecture into a sculpted work, very similar to the pavilion in the world of sculpture.

ABSTRACTED “HOUSE”

number https://www.hauserwirth.com/ursula/26923-not-vital-poetry-unique-intense/

Fig. 13 Courtesy of Agnes Monkelbaan, Agnes. One of Not Vital’s Houses to watch the sunset, located in Switzerland.

SECTION 1:32

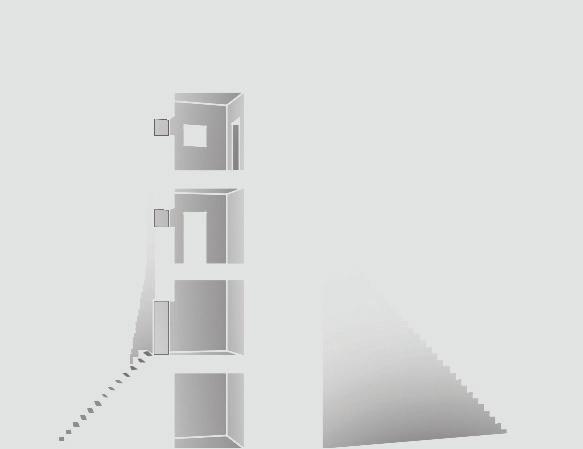

GC PROSTHO MUSEUM

KENGO KUMA RESEARCH CENTER

ELEVATION PLAN

Kengo Kuma and Associates finished the GC Prostho Museum Research Center in 2010 located in Aichi Prefecture, Japan. 31 The building contains laboratories and o ce space for research as well as a functioning gallery in an urban context. The already striking design stands out among the modern surroundings.

The design of the medium sized gallery was inspired not only by traditional Japanese wood joinery, but specifically a wood joinery toy called cidori. 32 The toy’s image is repeated, becoming the simplified, orthogonal structure of the building. No wood glue was used to create the structure, celebrating the craft of wood joinery so strong that even a toy can support an entire functional building.33

The interior space is carved from the gridded structure, creating the gallery. The private spaces are made of concrete, and located within the gridded structure. The grid terminates into the interior spaces connecting to the concrete. Sculptures and artwork are displayed inside the grid, calling back to traditional Japanese infrastructure but arranged in a contemporary context.

ABSTRACTION & SIMPLIFICATION

SPATIAL SEGMENTATION & AWARENESS OF SELF

JOINERY

Fig. 14 Courtesy of Daici Ano. Kengo Kuma’s cidori inspired structure

SECTION 1:32

ELEVATION PLAN

THE OAK ROOM

ANDY GOLDSWORTHY

The Oak Room is located at the Chateau la Coste in Le PuySaints-Reparade, France. The structure is built from local materials, a old stone fence and tree branches collected from Burgundy, France.34

The structure is self supporting, created from weaving large tree branches together to create the interior, and then using stones to form the exterior in a square block form.

Goldsworthy’s sculptures straddle the line between monument, sculpture, and space. Many of his works are stand alone sculptures that directly interact with their environments, being made of their environments.35 Others, akin to The Oak Room, invite the user into the space, often with a glimse of what is hiding around a corner.

His works extend past monument and stand alone sculpture because of their being create by the environement, and not being displayed in plain view. The use enters the space, underground, and it seems time itself could stop. His grand compositions of nature invite the user to contemplate themselves in space and time, and nature.

number https://mrstromain.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/goldsworthyproject.pdf https://www.wnyc.org/story/andy-goldsworthy-his-new-book-projects/

COMPRESSION & AWARENESS OF SELF

IMMERSION UNDER GROUND SELF SUPPORTING

Fig. 15 Courtesy oif Château La Coste Exhibitions The Oak Room interior.

TWILIGHT EPIPHANY

JAMES TURRELL SECTION 1:32

ELEVATION

Twilight Epiphany is located next to the Shepherd School of Music on the Rice University Campus in Houston, Texas. Finished in 2012, the space is acoustically engineered to host performances and students of the music school.36 The space is connected to LED lights that project a lighting sequence onto the huge, seventy-two foot long roof.37 These lights along with the knife edge design of the roof play a crucial role in Turrell’s sky spaces.

The roof is cut through the center. The angle of the knife edge is designed to hide the true depth of the roof, giving it a paper thin appearance. The lighting projected onto the roof makes it appear as if it could be the sky. The sky coming through the center as a result feels weighted, like it is hung from the roof itself.

The user is immersed into the stone, steel, and concrete structure by light that plays with the illusion of heaviness of environment and lightness of structure. Some say that you could believe it was not the true sky if its a clear day. The moving clouds break the illusion, giving away the secret of the space, but not taking away from its magic.

IMMERSION BY LIGHT

OUTWARD PROJECTION

Fig. 16 Courtesy of James Turrell. Detail of a skyspace.

DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO

DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO

Fig. 17 Courtesy of Elizabeth Diller. Arial view of The Blur.

ARENESS

ABSTRACTION IMMERSSION

ABSTRACTION

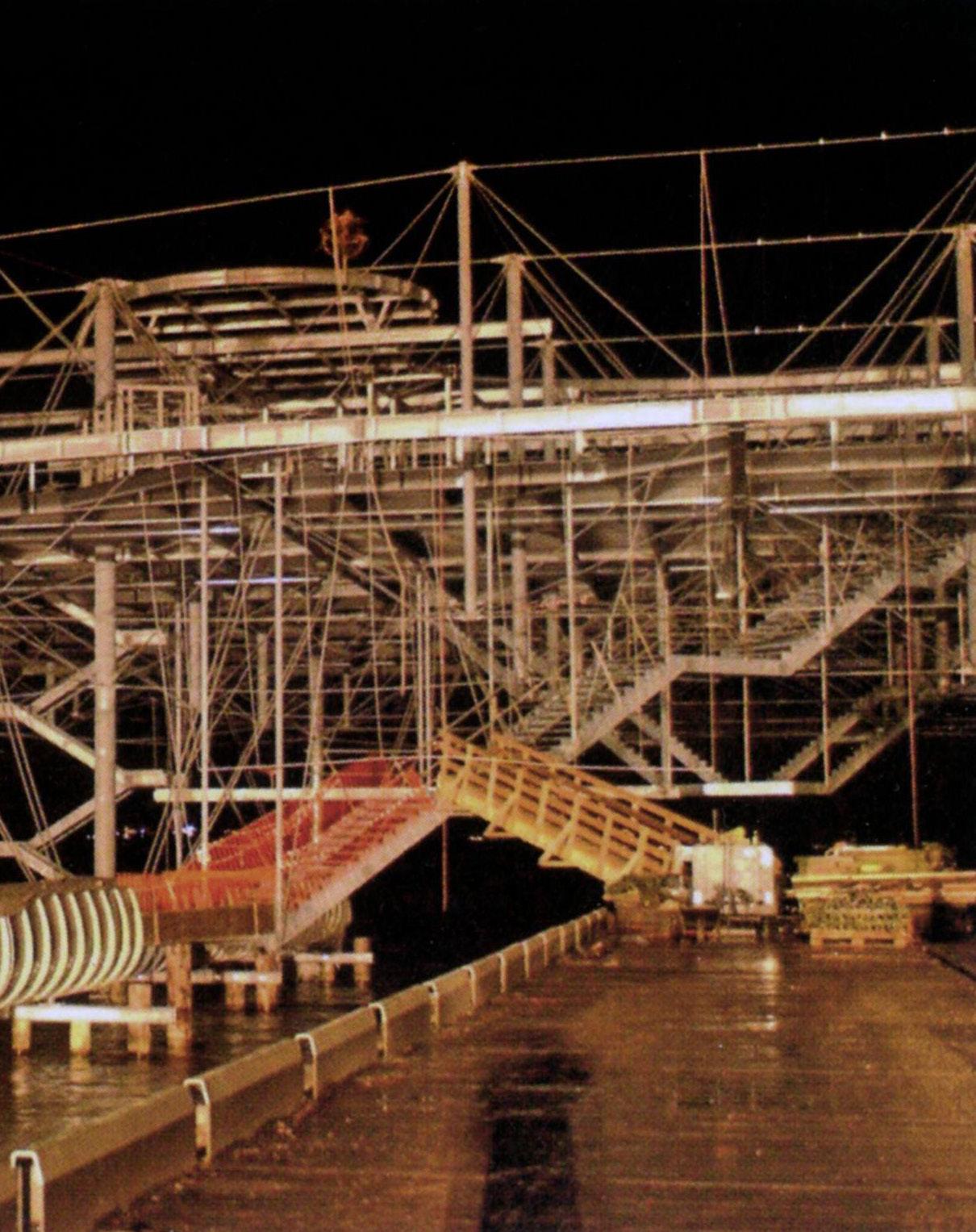

The finale to the collection is The Blur Building by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. It was built for the Swiss National Exposition in Yverdon-les-Bains in 2002 as a response to the oversaturation of visual media.38 By atomizing the water of Lake Neuchâtel, the space becomes low-definition and the hissing from mist nozzles surrounds users auditorally. The open space allows users to contemplate our dependence on vision and the experience of being inside ones body.39

THE BLUR

IMMERSSION

The massive three-hundred by two-hundred, by seventy-five foot tall structure is supported by four columns that imbed into the lake. Fresh water is pumped from the lake, filtered, and then misted through thirty-five thousand high pressure nozzles blurring the man made tensegrity structure.40

TWILIGHT EPIPHANY

SPATIAL AWARENESS

ABSTRACTION

ABSTRACTION OUTWARD PROJECTION

OUTWARD PROJECTION

PROJECTION ONTO SELF SPATIAL AWARENESS

THE BLUR

The idea of the Braincoat was developed to create a “proxicommunication” without language. The raincoat with embedded technologies create a “social radar.”41 While The Blur takes away the visual, the braincoat that would be worn by users on the pavilion uses log in information at the beginning of the experience to collect answers to twenty questions. As guests pass each other in the mist, their coats compare their answers and their compatibility (see Braincoat Experience). 42

TWILIGHT EPIPHANY

THE OAK ROOM

THE OAK ROOM

IMMERSION

IMMERSION BY MIST

SPATIAL AWARENESS OUTWARD PROJECTION IMMERSION

HEIGHTENED AWARENESS OF SELF & ENVIRONMENT

IMMERSION IMMERSION IMMERSION

SPATIAL AWARENESS SPATIAL AWARENESS OUTWARD PROJECTION

Fig. 18 Courtesy of Elizabeth Diller. The Blur Building.

Endnotes

1 Christpher Mount, and Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, Calif). A New Sculpturalism: Contemporary Architecture from Southern California. New York, Los Angeles, CA: Skira Rizzoli; In associationwith the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, (2013), 31-32.

2 Rosaline Kraus. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October 8 (1979): 32-33. https://doi.org/10.2307/778224.

3 Chad Schwartz. “Investigating the Tectonic.” Essay. In Introducing Architectural Tectonics, 2nd ed., 6–23. Routledge, 2016.

4 Dorian Wiszniewski. “‘The Space of Communicativity’: Lévinas and Architecture.” Lévinas, February 26, 2009, 191-193. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444309621.ch13.

5 Chad Schwartz. “Investigating the Tectonic. 6-23.

6 Ibid. 6-23.

7 Dorian Wiszniewski. “‘The Space of Communicativity’: Lévinas and Architecture.” 191-193.

8 Ibid. 191-193.

9 Ibid. 191-193.

10 Ibid. 68-80.

11 Kali Tzortzi. “The Display as Presentation in Space.” Chapter. In Museum Space, 68-80. Routledge, 2015.

12 Rosalind Krauss. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October 8 (1979): 31–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/778224.

13 Ibid. 31-44.

14 Ibid. 31-44.

15 Christpher Mount, and Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, Calif). A New Sculpturalism: Contemporary Architecture from Southern California.

16 “Archisculpture.” Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/ exhibitions/archisculpture.

17 Richard Serra. “Torqued Torus, Inversion, and Sequence.” 2006 | MOMA. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www. moma.org/audio/playlist/236/3049.

18 “Richard Serra: Sequence.” Cantor Arts Center Exhibitions. Accessed September 22, 2024. https://museum.stanford. edu/exhibitions/richard-serra-sequence.

19 Richard Serra. “Torqued Torus, Inversion, and Sequence.” 1.

20 Ishigami, Junya. “Serpentine Pavilion 2019 by Junya Ishigami.” Serpentine Galleries, September 15, 2023. https://www. serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/serpentine-pavilion-2019-designed-junya-ishigami/.

21 Ibid. 1.

22 Ibid. 1.

23 Bjarke Ingels Group. “The Twist.” BIG. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://big.dk/projects/the-twist-1337.

24 Ibid. 1.

25 Ibid. 1.

26 LeWitt, Sol. “Maquette for One, Two, Three.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed September 23, 2024. https:// americanart.si.edu/artwork/maquette-one-two-three-14689.

27 “One, Two Three.” General Administration Services: Fine Arts Collection, n.d.

28 Theus, Tilla. “Not Vital: Poetry, Unique and Intense.” Hauser & Wirth. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.hauserwirth. com/ursula/26923-not-vital-poetry-unique-intense/.

29 Morrell, Lara. “Not Vital: On Scarch, Sunsets and Silence: My Art Guides.” My Art Guides | Your Compass in the Art World. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://myartguides.com/interviews/not-vital-on-scarch-sunsets-and-silence/.

30 Theus, Tilla. “Not Vital: Poetry, Unique and Intense.” 1.

31 “GC Prostho Museum Research Center.” Kengo Kuma and Associates. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://kkaa.co.jp/en/ project/gc-prostho-museum-research-center.

32 Ibid. 1.

33 Ibid. 1.

34 “The Artwork.” Château La Coste · Artists and Architects in Provence. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://chateau-lacoste.com/en/art-architecture/artists-architects.html.

35 Goldsworthy, Andy. Andy Goldsworthy A Collaboration with nature . Edited by Terry Friedman. NY, NY: Harry N. Abrams 1998. 41.

36 “James Turrell Twilight Epiphany Skyspace.” Moody Center for the Arts. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://moody.rice. edu/james-turrell-twilight-epiphany-skyspace.

37 Ibid. 1.

38 “Blur Building.” DS+R. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://dsrny.com/project/blur-building.

39 Ibid. 1.

40 Ibid. 1.

41 “Braincoat.” DS+R. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://dsrny.com/project/blur-braincoat.

42 Ibid. 1.

1 Monkelbaan, Agnes. “‘House to watch the sunset”’by artist of Not Vital.”

2 Afzal, Corin. “The Three E ects of Created Space in Sculpture and Architecture.”Own Work.

3 Afzal, Corin. “Three Sculptural Design Techniques.” Own Work

4 Borges, Nuno. “The Twist.” October 05,2019. https://flic.kr/p/2i2gM7F

5 Krauss, Rosalind. “Klein Group for Architecture as Art.” From Sculpture in the Expanded Field, 37.

6 Afzal, Corin. “Klein Group for Architecture as Sculpture.” Own Work

7 Afzal, Corin. “Programmatic Needs and their Square Footage.” Own Work.

8 Afzal, Corin. “Programmatic Adjacencies.” Own Work.

9 Corder, Rob. Sequence. August 18, 2011. https://flic.kr/p/aef3ci

10 Murray, Ste. Serpentine Pavilion 2019 _ Junya Ishigami _ London _ 2019 _ Dusk. June21, 2019. https://flic.kr/p/2gCfLSD

11 Westvang, Astrid. The Twist. May 27, 2020. https://flic.kr/p/2j8jx4d

12 McKay Lodge Laboratory. Untitled. Photograph.

13 Monkelbaan, Agnes. “‘House to watch the sunset”’by artist of Not Vital.”

14 Ano, Daici. Forgemind ArchiMedia. Kengo Kuma - Prostho Museum Research Centre. May 27, 2020. https://flic.kr/p/mvtrmB

15 Château La Coste Exhibitions. Oak Room Interior. Photograph.

16 Turrell, James, American, and artist. Dividing the Light. 2007. SAHARA Public Collection. SAHARA: Society of Architectural Historians Architecture

17 Diller, Elizabeth & Scofidio, Ricardo & Diller + Scofidio. Blur, Swiss Expo. 2002. https://jstor.org/stable/community.16511454.

18 Diller, Elizabeth & Scofidio, Ricardo & Diller + Scofidio. Blur, Swiss Expo. 2002. https://jstor.org/stable/community.16511449.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Archisculpture.” Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/exhibitions/ archisculpture.

“The Artwork.” Château La Coste · Artists and Architects in Provence. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://chateau-la-coste.com/en/ art-architecture/artists-architects.html.

Bjarke Ingels Group. “The Twist.” BIG. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://big.dk/projects/the-twist-1337.

“Blur Building.” DS+R. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://dsrny.com/project/blur-building. “Braincoat.” DS+R. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://dsrny.com/project/blur-braincoat.

Chad Schwartz. “Investigating the Tectonic.” Essay. In Introducing Architectural Tectonics, 2nd ed., 6–23. Routledge, 2016.

Christpher Mount, and Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, Calif). A New Sculpturalism: Contemporary Architecture from Southern California. New York, Los Angeles, CA: Skira Rizzoli; In associationwith the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, (2013), 31-32.

Dorian Wiszniewski. “‘The Space of Communicativity’: Lévinas and Architecture.” Lévinas, February 26, 2009, 191-193. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444309621.ch13.

“GC Prostho Museum Research Center.” Kengo Kuma and Associates. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://kkaa.co.jp/en/project/gcprostho-museum-research-center.

Goldsworthy, Andy. Andy Goldsworthy A Collaboration with nature . Edited by Terry Friedman. NY, NY: Harry N. Abrams , 1998. Ingels Group, Bjarke. “The Twist.” BIG. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://big.dk/projects/the-twist-1337. Ingels Group, Bjarke. “The Twist.” BIG. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://big.dk/projects/the-twist-1337.

Ishigami, Junya. “Serpentine Pavilion 2019 by Junya Ishigami.” Serpentine Galleries, September 15, 2023. https://www.serpentinegalleries. org/whats-on/serpentine-pavilion-2019-designed-junya-ishigami/.

“James Turrell Twilight Epiphany Skyspace.” Moody Center for the Arts. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://moody.rice.edu/jamesturrell-twilight-epiphany-skyspace.

Kali Tzortzi. “The Display as Presentation in Space.” Chapter. In Museum Space, 68-80. Routledge, 2015.

LeWitt, Sol. “Maquette for One, Two, Three.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://americanart. si.edu/artwork/maquette-one-two-three-14689.

Morrell, Lara. “Not Vital: On Scarch, Sunsets and Silence: My Art Guides.” My Art Guides | Your Compass in the Art World. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://myartguides.com/interviews/not-vital-on-scarch-sunsets-and-silence/.

“One, Two Three.” General Administration Services: Fine Arts Collection, n.d.

“One, Two, Three.” U.S. General Services Administration: Fine Arts Collection, January 1, 1979. https://art.gsa.gov/objects/18565/onetwo-three.

“Richard Serra: Sequence.” Cantor Arts Center Exhibitions. Accessed September 22, 2024. https://museum.stanford.edu/exhibitions/ richard-serra-sequence.

Richard Serra. Torqued Torus, Inversion, and Sequence. 2006 | MOMA. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.moma.org/audio/ playlist/236/3049.

Rosaline Kraus. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October 8 (1979): 32-33. https://doi.org/10.2307/778224.

Schwartz, Chad. “Investigating the Tectonic.” Essay. In Introducing Architectural Tectonics, 2nd ed., 6–23. Routledge, 2016.

Theus, Tilla. “Not Vital: Poetry, Unique and Intense.” Hauser & Wirth. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.hauserwirth.com/ ursula/26923-not-vital-poetry-unique-intense/.

Wiszniewski, Dorian. “‘The Space of Communicativity’: Lévinas and Architecture.” Lévinas, February 26, 2009, 183–94. https://doi. org/10.1002/9781444309621.ch13.