Full download ebooks at https://ebookmeta.com Atlas of World War II History s Greatest Conflict Revealed Through Rare Wartime Maps and New Cartography 1st Edition Stephen G. Hyslop For dowload this book click link below https://ebookmeta.com/product/atlas-of-world-war-ii-historys-greatest-conflict-revealed-through-rare-wartime-maps-andnew-cartography-1st-edition-stephen-g-hyslop/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Eyewitness To World War II The 75th Anniversary Edition

Stephen G. Hyslop

https://ebookmeta.com/product/eyewitness-to-world-war-iithe-75th-anniversary-edition-stephen-g-hyslop/

World War II Re explored Some New Millenium Studies in the History of the Global Conflict Jaroslaw Suchoples (Editor)

https://ebookmeta.com/product/world-war-ii-re-explored-some-newmillenium-studies-in-the-history-of-the-global-conflict-jaroslawsuchoples-editor/

The Phantom Atlas The Greatest Myths Lies and Blunders on Maps Edward Brooke-Hitching

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-phantom-atlas-the-greatestmyths-lies-and-blunders-on-maps-edward-brooke-hitching/

The Oxford Handbook Of World War II 1st Edition G. Kurt Piehler

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-world-warii-1st-edition-g-kurt-piehler/

The Oxford History of World War II 1st Edition Richard Overy

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-oxford-history-of-world-warii-1st-edition-richard-overy/

The Rise Of Hitler Deutschland Erwache Images Of War Rare Photographs From Wartime Archives Trevor Salisbury Translator And Editor

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-rise-of-hitler-deutschlanderwache-images-of-war-rare-photographs-from-wartime-archivestrevor-salisbury-translator-and-editor/

China s good war how World War II is shaping a new nationalism 1st Edition Rana Mitter.

https://ebookmeta.com/product/china-s-good-war-how-world-war-iiis-shaping-a-new-nationalism-1st-edition-rana-mitter/

History of War Defining Battles of World War II 4th Edition 2023 Dan Peel - Editor

https://ebookmeta.com/product/history-of-war-defining-battles-ofworld-war-ii-4th-edition-2023-dan-peel-editor/

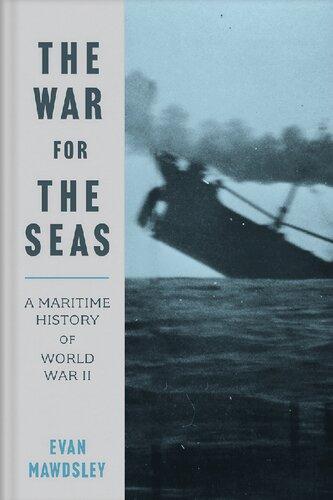

The War for the Seas A Maritime History of World War II 1st Edition Evan Mawdsley

https://ebookmeta.com/product/the-war-for-the-seas-a-maritimehistory-of-world-war-ii-1st-edition-evan-mawdsley/

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Fig. 313. John Wickliff, a theologian Heresiarch, the Precursor of Luther, born at Wickliff, in England, about 1324, died in 1387. After the “Vrais Pourtraits des Hommes Illustres:” 4to, Jean de Laon, Geneva, 1581.

The staunchest Catholic writers admit that the clergy are themselves responsible for the triumph of the heretics. Moeller says —“The relaxation of ecclesiastical discipline amongst the clergy and that in a great many religious communities, from which the pontifical court itself was not always exempt, gave the sectaries of the sixteenth century a pretext for their rebellion against the Church, its doctrines, its hierarchy, and its institutions. To this moral decadence of a great part of the clergy must further be added the profound ignorance of the upper clergy; and even those who cultivated

literature and science confined themselves almost exclusively to the study of Greek and Latin literature, which directed the whole course of scientific research from the fifteenth century downwards. Many pagan ideas had pervaded men’s minds, and had contributed to create a feeling of contempt both for Christianity and for that beautiful Christian literature which had shed a lustre on the Church from the very earliest times. This condition of the clergy had a baneful influence upon the mass of the people, who lived in utter ignorance of religion, and who had lost their attachment to the Church and all respect for its pastors.”

This religious indifference of the clergy and of the people explains the success, not only of the heresiarchs who presented themselves as reformers of manners and discipline, but even of the sects held in the lowest esteem, the sorcerers, for instance. The facts are too numerous and too well-authenticated to admit of any doubt upon this head. There existed throughout all Europe, in the Middle Ages, numerous sects of sorcerers and witches who in all seriousness professed to give themselves over to the devil in exchange for the gift of magic power. The Spanish Inquisition was not the only body which sent them to the stake, after having submitted them to trial and received the confession of their misdeeds; the French tribunals pronounced sentence of death in similar cases when the accused, after long and minute interrogatories, but without being put to the torture, made a confession of their satanic orgies known by the name of sabbat (Fig. 314). This kind of heresy eluded all the steps taken by the civil and the religious powers to put it down. The “Histoire des Procès de Sorcellerie,” by Soldam, tells us that, even at the close of the sixteenth century, from 1590 to 1594, thirty-five witches were condemned to be burnt, out of a total population of six thousand, in the small Protestant town of Nordling, in Germany. The enormities of the sect of sorcerers attest, no doubt, a profound depravation of morals, but they contained no germ of social revolution; such, however, was not the case with the theories expounded by the great heresiarchs.

Fig. 314. The “Sabbat,” reprint of the legend contained in a sentence of the Arras Tribunal in 1460. Engraving of the Sixteenth Century, preserved in the National Library, Paris.

Wickliff’s doctrine soon made its way into Germany. It was propagated by John Huss, one of the doctors at the University of Prague. When the University discovered this, it solemnly condemned Wickliff’s books, and prohibited them from being read. John Huss did not venture upon any overt opposition; but, as the doctors of the University were Germans, he called to his aid the vanity of the Bohemians and the personal ill-will of King Wenceslaus against the Germans, who had deposed him from the empire. The situation of the professors became untenable, and they left with their two thousand pupils for Leipsic, where they founded the University. John Huss was joined by several ecclesiastics, who were anxious to acquire liberty of action; but the leading Bohemian professors,

convoked by the archbishop to examine the works of Wickliff which John Huss had distributed amongst the Bohemian nobles, decided that the possessors of these books should surrender them to be burnt. John Huss again endeavoured to temporise, promising the archbishop to correct in his preaching anything which might have escaped him contrary to Christian doctrine; for, in his view, this promise did not prevent him from propagating the doctrine of Wickliff, which he believed to be quite orthodox. He was supported by Jerome of Prague, a man of position, who, in addition to his ardour and daring, was a bachelor in theology, though a layman. The latter was so zealous in his partisanship, that he upon one occasion stopped three Carmelite monks who had been combating the theories of Wickliff, and threw one of them into the Moldau. Denounced to the pope by the clergy of Prague, John Huss and his adherents were declared heretics and excommunicated. A rebellion got up in Prague by his partisans, headed by the impetuous Jerome, cost a great number of them their lives, the senate visiting their crimes with capital punishment. John Huss appealed from the sentence of the pope to the next council; and this, which was held at Rome in 1413, condemned afresh the writings of Wickliff and excommunicated John Huss, who had not put in an appearance, although he was cited before the Council. The Chancellor Gerson, the illustrious Dean of the Faculty of Theology in the University of Paris, which had just condemned the nineteen errors of John Huss, wrote to the Archbishop of Prague, exhorting him to take the necessary steps for repressing this heresy.

That prelate, in conformity with Gerson’s advice, obtained the support of the King of Bohemia; and it was decreed that all those who still adhered to the condemned theories of Wickliff should be expelled from the kingdom. John Huss was thus compelled to leave the city, but he declaimed as vehemently as ever against the Church, and especially against the pope.

Fig. 316. Jerome of Prague, a Disciple of John Huss, born at Prague about 1378; burnt alive for heresy at Constance in 1416.

After the “Vrais Pourtraits des Hommes Illustres:” Jean de Laon, Geneva, 1581.

The Council of Constance, convoked for the 1st of November, 1414, was ordered to examine his doctrines. John Huss, far from flinching at this decisive moment, vehemently called upon his adversaries, by public placards, to come and put him to confusion before the council. “If,” he stated in these placards, “I can be convicted of any error, or of having taught anything contrary to the Christian faith, I am ready to undergo the punishment inflicted upon heretics.” He then solicited and obtained from the Emperor Sigismund a safe-conduct, in which it was stated that, “out of

respect for the imperial majesty he was to be let freely and safely pass, sojourn, remain, and return, and be provided, if necessary, with other fitting passports.” John Huss left Prague on the 11th of October (Figs. 315 and 316), and on the 20th, in a letter written from Nuremberg, he expresses his satisfaction at the reception which he has everywhere met with, especially from the ecclesiastics, who seemed disposed to accept his doctrine. Upon reaching Constance, on the 3rd of November, he expounded his ideas very freely, both by word of mouth and in writing; and, in spite of the excommunication hurled against him, he said mass every day in a private room, but without making any secret of it, to the inhabitants of the neighbourhood. Upon the 28th of November he was arrested and cast into prison. After many witnesses had been examined, thirty-nine articles taken from his speeches and writings were read in public, the most important of which declared “that the elect alone are members of the Catholic Church; that St. Peter neither is nor ever has been the chief of that Church; that by the commission of mortal sin the ecclesiastical and civil authorities lose their rights and privileges; and lastly, that the condemnation of the forty-five articles of Wickliff was unreasonable and unjust.” The venerable Peter d’Ailly exhorted John Huss to submit himself to the judgment of the council; the emperor did the same, threatening him, if he refused, with the rigour of the law. Upon the following day he was given a recantation to sign, which he would not consent to do. A fortnight afterwards, on the 24th of June, his books were condemned to be burnt. On the 6th of July the council declared him to be a heretic, and degraded him from his ecclesiastical orders, by which process he was handed over to the secular arm. The emperor, who was present, had him immediately seized by the count-palatine, and the civil law, which condemned stubborn heretics to the stake, was applied in all its rigour. John Huss submitted to his fate with courage. Jerome of Prague at first signed the formula of recantation, but he soon afterwards disavowed it; and, after publicly declaring that he adopted the whole doctrine of John Huss, he also was sent to the stake.

These pitiless measures failed to intimidate the partisans of John Huss; on the contrary, they became converted into a horde of fanatics, in which all the sects hostile to the Church became indiscriminately merged. Ziska, the chamberlain of King Wenceslaus, placing himself at their head, ravaged Bohemia, pillaged the monasteries, massacred the monks, constituted himself absolute master of the country, holding in check the whole military force of the empire. After his death (1424) the Hussites, far from giving in their submission and avowing their errors, continued supreme in Germany, so that Luther had only to cast seed upon the ground which they had bedewed with blood.

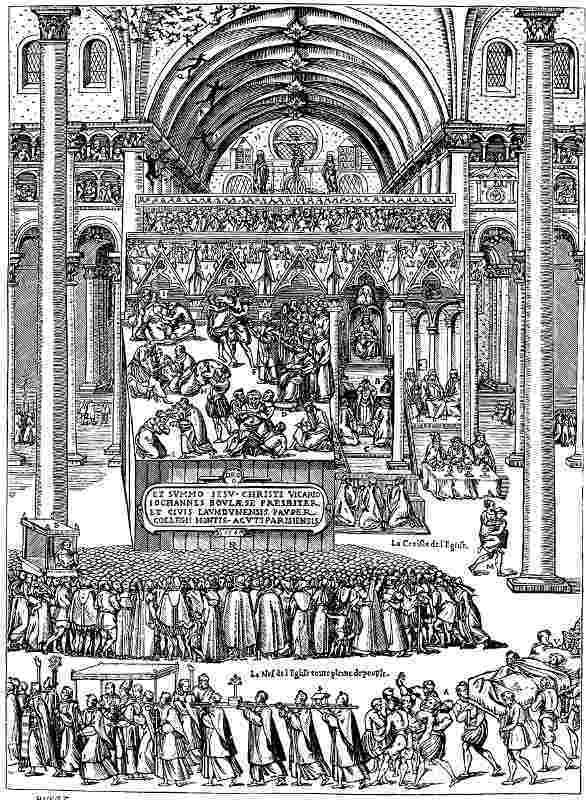

By a strange anomaly, the Hussites remained firmly attached to the dogma of the eucharist; and the chief inducement of the people to join their party was, in several cases, the privilege of being able to receive the communion in both kinds. The Hussites, assembled to the number of forty thousand in their celebrated camp of Tabor, by the wayside, without any preliminary confession, received the communion under the elements of bread and wine. Their leader signed himself Ziska of the Chalice; and when the moderate section of the party separated themselves from the more advanced section, he chose the name of Calixtines to indicate his own followers. The Protestants, on the contrary, were not long in coming to deny the real and abiding presence of Christ in the eucharistic elements. The importance attached to this dogma drew general attention to the extraordinary case of a woman possessed, who travelled through the dioceses of Laon and Soissons towards the middle of the sixteenth century. This was a young woman, recently married, of the name of Nicole, belonging to a humble but very honest family. There were many public exorcisms, and the paroxysms of the patient were always allayed by the giving of the sacrament. The case was much criticised; it was submitted to a scrupulous examination, and the agitation which it gave rise to was so great that the authorities intervened. Nicole was handed over to the royal delegates (Fig. 317), “who ordered that all the experiments should be made by physicians and surgeons officially appointed, and selected from

among Catholics and Protestants alike, so that there should be no suspicion attaching to their reports.” The evidence of these doctors did away with all idea of fraud, which the judicial authorities would have had no hesitation in punishing had it been practised. The Prince de Condé, Governor of Picardy, and one of the warmest upholders of the Reformed Religion, so called, detained for several days at his residence the possessed woman, together with her parents, who accompanied her wherever she went; but his interrogatories failed to shake their conviction that Nicole had been possessed, and that the eucharist had restored her. At last, a royal order enabled these poor people to return to their own home at Vervins.

8th of February, 1566.

Reduced Fac-simile of an Engraving in the “Manuel de la Victoire du Corps de Dieu sur l’Esprit malin,” by Jean Boulaese: 16mo., Paris, 1575.

The ecclesiastical authority, seconded as it was by the orthodox sovereigns, had been nearly always sufficient to suppress the heretical movements, which were circumscribed within a few provinces or dioceses; but the violent dissensions of Rome with the Empire, the two rival camps, formed during two centuries between the popes and the anti-popes, the independent position acquired by the communes after reiterated uprisings against their bishops and nobles, rendered necessary the intervention of a judicial authority in the religious quarrels and contentions springing out of the heresies and schisms which were constantly arising. The creation of this authority, half civil and half ecclesiastical, emanating from the throne, was mainly with a view to protect the legacy of the past against the encroachments and the audacious claims of the future. This is how it came to pass that, from the fourteenth century, the courts styled Cours des Grand Jours, the presidential tribunals, the parliaments, and even the bailiwicks, together with the Châtelet of Paris, intervened in matters of worship, though their rulings were not always in accordance with canonical law. The Inquisition failed to effect a permanent lodgment in France, but the ordinary tribunals claimed for themselves the right to take cognizance of crimes of heresy without having recourse to the aid of the ecclesiastical authorities.

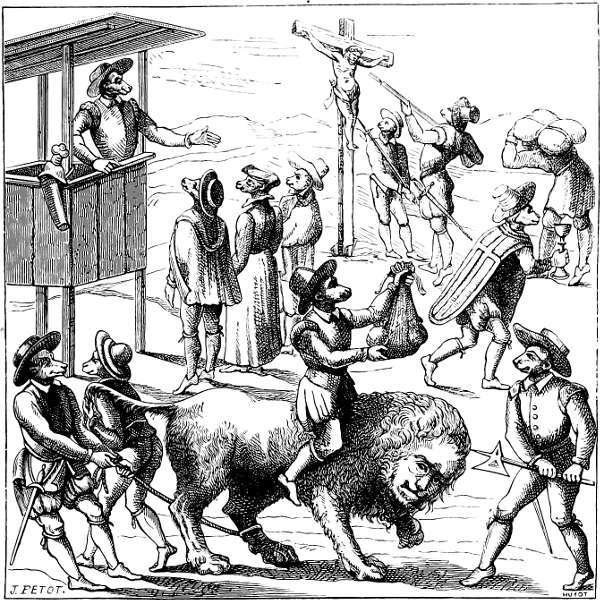

Fig. 318. Allegorical Picture of the Excesses committed by the Huguenots. The lion bound and tamed represents France reduced to a deplorable position by the heretics, as much by civil war, pillage, violence, and bloodshed, as by the impiety of which they left traces everywhere, profaning churches, breaking the sacred vessels, and treading under foot the crosses, the images, and the relics of the saints.—After a Drawing from the Manuscript “De Tristibus Franciæ,” preserved in the Library of Lyons. (Sixteenth Century.)

Fig. 319. John Knox, Propagator of the Reformed Religion, so-called, in Scotland; born at Gifford in 1504, died in 1572.

Fig. 320. Ulrich Zwingle, the first champion of religious reform in Switzerland; born and died at Wildhaus, in the Canton of St. Gall, 1484–1531.

From the “Vrais Pourtraits des Hommes Illustres:” Jean de Laon, Geneva, 1581.

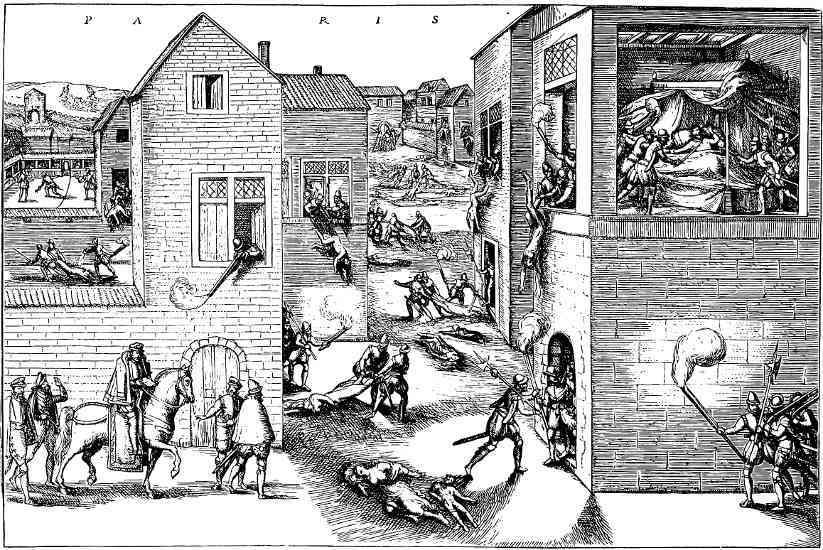

Fig. 321. The Massacre of St. Bartholomew, Paris, August 24th, 1572. The principal subject is the murder of Coligny. To the left, the admiral is leaving the Louvre, and while reading a memorandum is wounded by an arquebuse fired by Maurevert from a window (August 22nd); in the background, one of his equerries is communicating this fact to King Charles IX., whom he finds playing at tennis. To the right, Coligny, attacked by soldiers in his hotel, Rue Béthisy, is assassinated by Besme, and his body, thrown from the window, falls at the Duc de Guise’s feet. In the next house Téligny and other Protestants are being massacred.—After a German Engraving, a reprint of one of the Supplementary Plates of the Collection engraved by Jean Tortorel and Jacques Perrissin.

When Luther’s protests against Rome and Catholicism (1517) first burst upon the world, the heresy of Reform had long slumbered in a chrysalis state, so to speak, awaiting only some circumstance to favour its development. “The egg was laid,” as Erasmus remarked, “Luther had but to incubate and hatch it.” The corruption of the higher classes, of the clergy, and of the people, increased his chances of success. The suppression of celibacy amongst the clergy, and of monastic vows, was looked upon with secret favour by the

depraved among the bishops, priests, and monks; the prospect of seeing all the property of the Church fall into their possession excited the cupidity of the princes and nobles; and the rejection of ecclesiastical teaching flattered the vanity of the people, who were made supreme judges of the dogmas through the right which had been given to them, themselves to interpret the Bible, now translated into the vulgar tongue. For two centuries Rationalism had been disseminating the leaven of revolt against the authority of the past, and the advent of printing lent it fresh force. The apostle of the new doctrine had only to pronounce the word negation, and an army of disciples rose up to follow him and fight under his banner disciples who, at first obedient to his command, soon became rebellious, and impatient to obtain for themselves the liberty of inquiry and the independence of principles which Luther despotically endeavoured to reserve exclusively for himself. Carlstadt, Œcolampadius, Hutten, Zwingle (Fig. 320), Schwenckfeld, Munzer, Staupitz, Knox (Fig. 319), and many others, while following in the footsteps of the famous Wittenberg professor, had their own school: “The teachings crashed like avalanches, the doctrines rattled like the tempest; there was a dark abyss of neologies, inconsistencies, and contradictions, amidst which no ray of the eternal sun of grace was visible,” to quote the poetic simile of Wieland. The intellectual movement was none the less gigantic, especially in Germany and in the countries bordering on the Moselle. A deluge of statements, of pamphlets, and of stories, some true and others false, issuing, most of them anonymously, from an infinity of printing-presses, were rapidly disseminated, and made their way into every district; the allegorical eucharist of Zwingle, the revolutionary appeal of Munzer to the Franconian monks, the restoration of the letter by Schwenckfeld, the trope of Carlstadt against Luther, assumed a thousand different forms; while the indefatigable Luther himself, in turn a Demosthenes, a Petronius, a Danubian peasant, a beersodden drunkard, spun out in fifteen thousand folio pages his senseless Protestant theories—a chaos of eloquence, poesy, impassioned similes, tangible truths, audacious falsehoods, venom, hatred, jealousy, and filth. The famous Leipsic dispute, the sessions

of Worms and of Augsburg, the war of extermination of the peasantry, the quarrel about images, the interview of Mauburg, the Massacre of St. Bartholomew in France (Fig. 321)—in a word, the numerous revolutions of this great religious drama which Europe was watching with nervous anxiety, are brought into less marked relief in the large works since published by learned controversialists, than in these desultory pages, scattered to the winds, sung at the streetcorners, accompanied by denunciations, threats and sanguinary struggles between the irreconcilable factions of Catholic and Huguenot.

Fig. 322. Martin Luther. Reduced Facsimile of a Portrait by Lucas de Cranach (1520), published in the flyleaf of a sermon preached by Luther against the authority of the Roman Church (in octavo, Wittenberg, 1522), when he threw off his garb of an Augustine monk. The Latin distich renders famous both the artist and the original in these words:—“If Luther leaves imperishable traces of his genius, Lucas (Cranach) perpetuates for ever the features which death will efface.”

Lutheranism, in consequence of a revolt in the cloister, had led to anarchy in the Church, to the exile of Carlstadt, who was compelled

to beg his bread from village to village, to the persecutions against Œcolampadius and Schwenckfeld, and to the massacre of a hundred thousand rebellious peasants in Thuringia and Swabia. A multitude of sects—the Sacramentarians, the Œcolampadians, the Antinomians, the Majorists, and the Anabaptists were given birth to by the heresy of Luther; there were as many popes as there were dissenting churches. The Lutheran creed was still confined to the countries on the other side of the Rhine, when the French sectaries, Farel and Froment (Fig. 324), set out to revolutionise Geneva and the neighbouring country. An unjust hatred for the House of Savoy attracted to their standard a large body of patriots, who, aspiring after a democratic independence, hoped to rid themselves of hereditary monarchy and to break with Catholicism, its main ally.

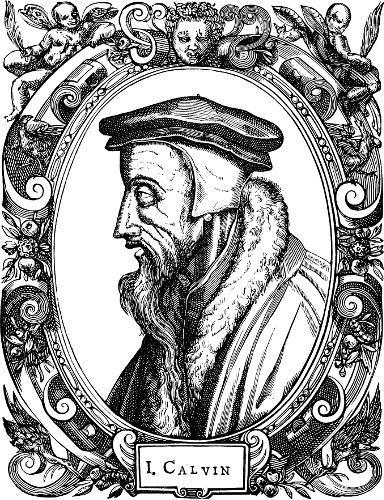

Fig. 323. John Calvin, called the Pope of Geneva, chief of the so-called Reformed Church; born at Noyon in 1509, died at Geneva in 1564. Facsimile of a Wood Engraving from the works of Theodore Beza, translated from the Latin by Simon Goulart “Les Vrais Pourtraits des Hommes Illustres” (4to, Jean de Laon, Geneva, 1581). One of the engraved frontispieces of this collection bears the monogram of Jean Cousin.

In England, the king separated himself from the Roman Church. Henry VIII., unable to obtain from Pope Clement VIII. a bull annulling his marriage with Catherine of Arragon, and permitting him to espouse Anne Boleyn, declared himself to be the supreme and only head of the Church in his own kingdom, but he did not touch

upon the dogmas which he had defended against Luther; thus it was a schism rather than a heresy. Under his successors, in conformity with a decision of the English Parliament, a synod assembled in London drew up the Confession of Faith for the Anglican Church, which differs less than any other, in regard to dogma and discipline, from the traditions of the Catholic Church.

Fig. 324. William Farel, preacher of the so-called Reformed faith; born at Gap in 1489, died at Geneva in 1565. From the “Vrais Pourtraits des Hommes Illustres:” 4to, Jean de Laon, Geneva, 1581.

Calvin, upon arriving at Geneva, his mind imbued with those evangelical novelties which constituted a heresy essentially French, found the Reformation already accomplished there. Its passage was

marked only too plainly by ruins and blood-stains; the stripping of the vanquished by their conquerors had turned a religious reform into a social revolution. Calvin, a jealous and inflexible sectary, laid hold upon reform as an instrument of despotism. In order to become head of the Church as well as head of the State, he proclaimed the doctrinal negation of authority, thus beginning where Luther ended. To the Saxon-like creed of the great Reformer, he adapted a mixed system concerning the Lord’s Supper borrowed from Zwingle and Œcolampadius; he was ardent and pitiless, as the sad fate of Servet and of Gruet too clearly prove; he was determined to reign by terror, for he was a slave of politics rather than of spiritual ideas. This it is which constitutes so marked and characteristic a difference between the two champions of Protestantism, between the rebellious monk of Wittenberg and the apostate priest of Noyon. Calvin entered upon an overt struggle with all the renegades of the Catholic school, with Gentilis, Ochino, Castalion, and Westphalz; his doctrine and his teaching were alike divergent from those of Zwingle in the mountains of Switzerland, of Melancthon in the University of Wittenberg, of Œcolampadius at the foot of the Hauenstein, of Martin Bucer at Strasburg, and of Brentzen at Tubingen. Amongst the Geneva sectaries, two friends, Farel and Beza, alone remained faithful to him, more through compatibility of temperament than from identity of principles. The French Huguenots had, however, accepted as their supreme chief a theocrat like Calvin, who, for fourand-twenty years, never stepped without an escort of swords, of faggots, and of executioners (Fig. 325).

Fig. 325. Violence of the French Huguenots against the Catholics. A. Noble lady of Montbrun (Charente) being tortured by soldiers whom she had hospitably welcomed. They are burning the soles of her feet with red-hot irons, and with the sharp edges of the irons cutting the skin from her legs in strips.—B.

Master Jean Arnould, Procureur-Royal at Angoulême, after having had his limbs mutilated, is strangled in his own house.—C. The widow of the Procureur at the criminal court of that city, seventy years of age, being dragged by the hair through the streets. Fac-simile of a Copper-plate in the “Theatrum Crudelitatum nostri Temporis” (4to, Antwerp, 1587).

Fig. 326. Seal of an imaginary Bull of Lucifer, taken from the “Roi Modus,” a Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century, in the Burgundian Library, Brussels. The inscription on the seal seems to be cabalistic; at any rate, it is unintelligible.

It is therefore to Calvin and his personal influence that must be attributed the violent and merciless character which reform took during the sixteenth century, when the horrors of religious warfare were excused by the necessity of preaching the word of God to Christians who were anxious to hear it!