CM

Commonwealth School Magazine Winter 2025

Words, Words, Words...

Commonwealth School Magazine Winter 2025

Words, Words, Words...

In the fall of 2023, I approached Mr. Hodgkins, our Director of Music, about writing a piece for the Commonwealth Chorale.

Usually, when I write a piece, the music comes first and the title omes later. But this was different. The only thing I ever knew for certain was the title. It comes from a phrase I overheard at a concert hall in Cambridge: “only when the clock stops does time come to life.”

Wondering if it was nothing but a clever philosophical conjecture made by an intellectual concertgoer, I looked up the phrase. I was wrong; it came from William Faulkner’s 1929 novel, The Sound and the Fury

So I decided to read it. It was one of those books where I didn’t understand a single thing. You could have asked me “what happened?” two days into reading it, and I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. But I did notice one thing: Faulkner’s narrator repeats himself—a lot. Identical pieces of description, word for word, syntax for syntax, would come back again and again, phrases like “Caddy smelled like trees in the rain” or “I could hear the bright, smooth shapes” or “I’m not going to mind you” or “I wasn’t crying, but I couldn’t stop.” From those repeated phrases, I began my work on “only when the clock stops...”

One of my great mentors, the composer Lei Liang, has said that a composition contains three parts: the idea, the musical material, and the execution of the material (i.e., “technique”). In reading Faulkner’s book, I found the material for this piece: those repeated phrases of Faulkner’s. What was left was an overarching idea to tie the piece together conceptually, and the notes and rhythm to turn these materials into music. Quite naturally, time became the obvious candidate for the conceptual idea.

“I dont [sic] suppose anybody ever deliberately listens to a watch or a clock. You dont [sic] have to. You can be oblivious to the sound for a long while, then in a second of ticking it can create in the mind unbroken the long diminishing parade of time you didn’t hear.”

— Quentin Compson in William Faulkner’s 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury

Time is a central theme of The Sound and the Fury and escaping from time, in particular. Benjy, the narrator of the first chaper, contemplates the relationship between the past, present, and future; he hopes to escape time by avoiding the present and only thinking about the past, looping his thoughts over and over again in his memories. On the other hand, Quentin, the second narrator, contemplates the slowing down or speeding up of time. Constantly aware of the “minute clicking of little wheels” that happens every second, Quentin attempts to destroy time, whether through destroying his watch or a grandfather clock, or by ignoring the cathedral bells across the river.

My piece examines Benjy’s and Quentin’s attempts to escape time in musical terms. French composer Gérard Grisey’s 1987 article “Tempus ex Machina” describes three aspects of musical time: the “skeleton” of time, the “flesh” of time, and the skin” of time. The “skeleton” represents a quantitative approach to time: the seconds or beats per minute, or the hertz. Meanwhile, the “flesh” and skin” are qualitative: a driving drum beat that makes time “flw” or a predictable chord progression that makes time stagnate.

Grisey’s article formed the basis for my exploration of musical time in this piece. In the same way Benjy dramatically repeats his phrases to dial back to the past, cells of rhythmic and melodic content repeat themselves in the piece, almost obsessively, in an attempt to “freeze” biological time. As for Quentin, it is the musical time that gradually speeds up; the violins begin the second movement by playing an unpitched pulse at sixty beats per minute, like the second hand of a clock. As Quentin becomes increasingly paranoid about the clock as an object, that unpitched pulse gradually becomes pitched, adding another layer of time (frequencies), then harmony (multiple frequencies), and finally an acelerando to end the piece.

I am beyond grateful to Mr. Hodgkins for giving me this opportunity to write for our very own Chorale, who performed this piece wonderfully during our 2024 spring concert!

Earlier this fall, we held our second annual literary assembly in honor of longtime Commonwealth English teacher Eric Davis. We welcomed poet George Kalogeris, who read from his most recent collection, Winthropos, weaving together memories of his Greek immigrant childhood with classical meters and mythological imagery. At the assembly, we were joined by our own pantheon: former Commonwealth teachers Judith Siporin, Kate Bluestein, Bill Wharton, and Polly Chatfiel (some of whom you will spend time with in this issue). I found myself wondering how many students, myself among them, have had their lives shaped by the ways we learned to read poetry at Commonwealth.

Like many Commonwealth students, I was an early and eager reader. My childhood was spent nestled in nooks with Nancy Drew or Little Women, hiding from chores and yelled exhortations to practice the piano. As a child, stories captured me; at Commonwealth, it turned out to be words. My teachers shone a laser beam on each particular word and convinced us, through their careful array of evidence, that each could connote several simultaneous, purposeful meanings. I was slower to believe that the writer artfully controlled those multiple meanings (how could anyone’s brain work like that?), but I heard it in poem after poem, parsed by my brilliant, patient teachers. As you will read in our profil of teacher Don Conolly, our school remains in brilliant hands, and we still marinate in language.

This is a school where if you asked people for their favorite words, they’d have them at the ready. My own favorite words taste like candy in my mouth: susurration, mellifluous crux, spatchcock (and perhaps I’ll fin some new favorites from the article that follows on current slang). From words, our English classes moved on to syntax as an artistic medium. And from there, to the fundamental ambiguity of metaphor, whose meanings advance and recede at the same time.

We then learned to posit a “speaker” of the poem. Again, I was slow to wrap my head around the idea that the speaker wasn’t the poet, that the poem reflecte artful control rather than spontaneous rhapsody. With careful inferences from tone and topic, we learned to conjure and describe a person speaking that poem. I have to believe this helped make us more empathic, that we were schooled in perspectivetaking as much as prosody. I learned that we are always trying to reach across to each other while swaying on the suspension bridge of language. In the “Reasons for Writing” piece that follows in this issue, we share vignettes of how many of those lessons from English class took hold in the lives of several alumni/ae writers and editors.

This issue also features alumni/ae whose careers took them in quite differen directions, and then new directions again. From lawyer to musician, from Slavic languages to medical school, from opera singer to nonprofi leader, these alumni/ae carved their own non-linear paths. A Commonwealth education empowers us in so many ways. As our lessons seep through the years, we can walk through the doors we choose.

Jennifer Borman ’81 Head of School

Commonwealth School Alumni/ae Magazine

Issue 27 Winter 2025

Editor-in-Chief Jessica Tomer

Editor Catherine Brewster

Contributing Writers

Jennifer Borman ’81

Catherine Brewster

Becca Gillis

Claire Jeantheau

Jessica Tomer

Lillien Waller

Charlie Zhong ’25

Contributing Art and Design

Richard Amster P’26, 28

Martina Ardisson

TIm Daw Photography

Becca Gillis

Hannah Holland Photo

Sarah Rahman ’27

Jessica Tomer

Printing Hannaford and Dumas

CM is published twice a year by Commonwealth School, 151 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02116, and distributed without charge to alumni/ae, current and former parents, and other members of the Commonwealth community. Opinions expressed in CM are those of the authors and subjects, and do not necessarily represent the views of the School or its faculty and students.

We welcome feedback: communications@commschool.org. Letters and notes may be edited for style, length, clarity, and grammar.

Printed on recycled paper. Please recycle.

We were thrilled to return to Camp Kingswood in Piermont, New Hampshire, for a fall Hancock fille with volleyball matches, pie baking, board-game battles, pumpkin carving, boating adventures, and so much more. While we saw some rainy days, students, faculty, and staff remained enthusiastic as ever as they cooked meals together, danced the night away, and put on a talent show for the books. Cap off the week with a double rainbow over the lake, and what more could we ask for?

This fall, twenty-two of our vocal and instrumental students auditioned for the Massachusetts Music Educators’ Association All-District Music Festival—the largest number ever sent from Commonwealth! Kudos to the following students who qualifie for an event this year:

All-District Festival

n Tomi Duintjer Tebbens Nishioka ’27

n Jake Hurwitz ’26

n Brian Li ’26

n Anoushka Menon ’28

n Linus Schafer-Goulthorpe ’27

n Adriaan Van Herck ’28

n Vybhav Velamoor ’27

n Addie Zha ’26

n Jovana Živanović ’28

n Milana Živanović ’25

Commonwealth students have been deepening their fil knowledge, thanks to Classics of World Cinema, “a project the language department cooked up to spark students’ curiosity about other cultures and open their minds to great art in the hopes of fomenting more intellectual fervor in their literature and language classes,” says organizer and humanities teacher Don Conolly. With film “sponsored” by Mr. Conolly and his language department kinsfolk, students and teachers alike have enjoyed and analyzed together Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7, Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Olmi’s Il Posto, and Ray’s Pather Panchali (with a planned fiel trip to the Harvard Film Archive’s screening of Ray’s Apu trilogy). “In addition to our desire to share our passions with students and colleagues, we also launched this project out of concern about the sinking prestige of the humanities in our society as well as the erosion of a shared intellectual culture,” notes Mr. Conolly. (Turn to page 25 to learn more about his work.)

This fall saw another action-packed sports season for the Mermaids! Both the Boys’ and Girls’ Varsity Soccer teams made impressive returns to the playoffs finishin the season with valiant effort in their semifina matches. Our Cross Country teams ran all the way to the championships, too, with the Girls’ team taking fift place and the Boys’ team taking sixth. Mira Haber ’26 was also named to the Cross Country All-Star team following her outstanding performance this season. Sailor Oliver Grant ’25 placed second in the ILCA 7 in the NESSA Single-Handed Championship at American YC in Rye, New York. As a top-two sailor, Oliver qualifie for the ISSA Single-Handed National Championship at St. Petersburg YC. Our community is proud as ever of our athletes—as demonstrated by the enthusiastic spectatorship from students, faculty, staff and families throughout the season!

Machu Picchu. Chinchero Market. Colca Canyon. Museo Larco Hererra. Real Felipe Fortress. This summer’s trip to Perú did not disappoint, with students spending almost two weeks soaking up the country’s culture, history, and language. Many thanks to Spanish teacher Mónica Schilder and Director of Admissions and Financial Aid Carrie Healy for showing these world travelers the time of their lives!

Theater doesn’t get much more immersive than this! Commonwealth became the backdrop for our fall play, A Doll’s House Deconstructed, as actors performed throughout the building and brought the notion of a dollhouse to life. Based on the Henrik Ibsen classic, A Doll’s House Deconstructed tackles raw moments of a family in contentment and in turmoil, featuring everything from games of hide-and-seek to a masked ball to forgery and blackmail to the shattering of a picture-perfect marriage. Featuring fifeen Commonwealth players, as well as an enormous, assiduously organized team of techies and ushers, the show left enthusiastic audiences clamoring for more over the course of its sold-out November run. Bravo to all involved, especially fearless director Susan Thompson.

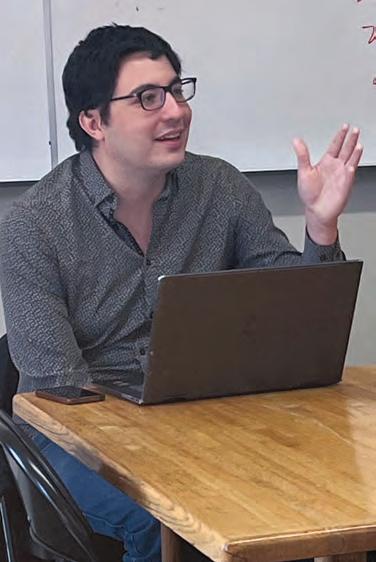

Led by English teacher—and scholar of transnational U.S. and Caribbean literature— Michael Samblas, a Caribbean Reading Group has taken o� at Commonwealth, with students, faculty, and sta� gathering at lunchtime to discuss such works as Louise Bennett-Coverley’s Jamaican patois poem “Dutty Tough.” Raised in Miami by Cuban parents, Mr. Samblas says Caribbean literature has been a lifelong passion, and it’s the focus of his graduate-school research. “Ever since starting at Commonwealth, I’ve wanted to fin ways to both help diversify the curriculum and leverage my own academic interests,” he says. “After a number of students expressed interest in the material I brought to my Diversity Day activity [“What Does it Mean to Study the Caribbean?”], I decided to see if the broader Commonwealth community would be interested in regularly examining a corner of the world whose literary output is often understudied, despite its cultural significanc and global impact.” The response has been enthusiastic, as the group tackles poems, essays, short works of fiction political documents, and more, with an eye toward “reading from a historicist or regional perspective, supplementing close reading with other methodologies that are commonly employed in the humanities.”

Commonwealth’s Board of Trustees kicked o� the academic year with their firs ever “advance” (not a “retreat”!), a day designed to deepen their collaboration and shared knowledge. Led by Mike Cobb of Pennsylvania-based consultancy Mission & Data, trustees spent a September Saturday sharpening their leadership skills and exploring the immutable qualities that make Commonwealth truly exceptional, such as ardent intellectualism, tight-knit community, and student agency. While Trustees bring wide-ranging expertise—from radiology to playwriting to law—to their work on the Board, they are united by their deep commitment to Commonwealth, as they made clear throughout the day. A Board’s work is most impactful when members can be thoughtful and strategic, and our trustees left the advance energized by the shared experience and well-equipped for a productive year to come.

Though school rankings are but one small, capricious metric in a sea of quality indicators, we are still grateful to have been named the #5 private high school in the United States and #3 in Massachusetts by Niche.com. Many thanks to everyone in our community for making Commonwealth such an exceptional place. Highlights from Commonwealth’s Niche rankings:

n #5 Private High School in the United States

n #3 Private High School in Massachusetts

n #1 Best Private High School in Suffol County

n #3

Best High School for STEM in Massachusetts

n #14

Best High School for STEM in the United States

n #11

Most Diverse Private High School in Massachusetts

This October, Govind Velamoor ’25 presented his work with MIT PRIMES, a program that allows high school students to work alongside MIT researchers on unsolved problems in mathematics, computer science, and computational biology over the course of a year. His research focused on API timeout optimization, or “mathematical, algorithmic, and machine learning approaches to optimize when computers should give up on something, even when that thing is constantly changing.” Kudos, Govind!

Commonwealth has always had a reputation for athletics: specifically, that we’re not ver good at them. There was something charmingly countercultural about embracing that identity, as many students and alumni/ae have. We’re nerds! We have our Plato and our problem sets. Let the other schools have their sports, and let our (nonexistent) football team remain undefeated. The joke in the 1980s: “Why did the Commonwealth student cross the road? For sports credit!” (Though that’s an unfair characterization; the ’70s and ’80s had solid fencing and squash programs, and a strong dance program under Jackie Curry.)

That reputation has held fast, even though the school has required athletic participation for more than forty years for all the reasons one would expect: camaraderie, leadership opportunities, general health and fitness, etc. Then, in yet another COVID-19 pandemic shift, Commonwealth saw not just an influx in applicants but a hunger amongst students (and families) for connection, including on the courts and fields.

Enter Jackson Elliott ’10, who returned to Commonwealth as our Director of Athletics and Wellness in January of 2022, bringing with him not just passion for sports and a deep familiarity with the school but a commitment to harnessing our recent growth to shape an athletics program that both speaks to student interests and stays true to our ethos. Jackson now coaches students as they face off against the same schools he played as a student athlete, amongst a host of other responsibilities. Keep reading as he and Head of School Jennifer Borman ’81 reflect on the evolution of Commonwealth athletics and moving toward their shared goal.

Jackson, what’s your typical day like as Director of Athletics and Wellness?

JE: A lot of it is about preparing for the next season, scheduling games and setting up coaches and facilities months in advance. That tends to be balanced with the miscellaneous things that come up day-to-day, like when a game gets rained out and needs to get rescheduled.

JB: You’re underselling the vast amount that falls in your purview! Finding all these facilities all over the city. Hiring and vetting our coaches. Talking to students to find out wher their interests lie. Liaising with other schools and their teams. Coordinating transportation.

Ordering uniforms. Not to mention teaching Health and Wellness to our ninth graders, interviewing for admissions, helping with lunch clean, and planning Hancock.

JE: (Laughing) Yeah, during the school day there just tends to be a lot of emailing and spreadsheets!

JB: Then in the afternoons we really get to reap the benefits of your work, once we get onto let’s say, a soccer field and the game kicks o� Then it's just about the kids having fun. And you’re in the thick of it, including as a coach.

JE: Yes, I coach the Girls’ Varsity Soccer team in the fall, Boys’ Varsity Basketball in the winter, and the Ultimate Frisbee A Team in the spring. I love coaching. That’s probably the most fun part of the job. It is definitly busy, and it means a lot of travel, but it’s really rewarding, especially seeing students grow year over year and teams start to gel each season.

You also stepped into the role of Hancock Czar, planning every detail of this beloved tradition in recent years. How has the work colored the way you think about Hancock, and why are trips like this still relevant?

JE: As a student, you’re focused on what you’re looking forward to at Hancock, what activities you want to do with your friends, and it’s easy to forget everything that happens behind the scenes. I mean, Hancock is truly a full community-wide effort, and students do their assigned jobs, but now that I’m on the other side of it, I know how much all the adults have on their plates, whether they’re facilitating meals or organizing morning activities or sleep chaperoning. It’s really rewarding to see it all come together. It may be exhausting, but at the end we can step back and say, “We did it.”

As for why we do this, it’s one of the ways students can get closer to everyone, especially ninth graders during fall Hancock. It’s a time when you’re balancing new classes, teachers, and sports with trying to connect socially with people. Having four days to forget about schoolwork and do some fun activities and maybe commiserate if it’s raining: that’s where you can really make some deep and meaningful connections that can last for not just the rest of the year but your entire time at Commonwealth and beyond.

Jackson Elliott ’10 Director of Athletics & Wellness

Enrollment in our team sports has increased by more than sixty percent over your tenure, Jackson, and, anecdotally, there seems to be more enthusiasm amongst players and fans alike. How has our athletics program evolved since you both were students?

JB: We do have a lot more participation, and I think that comes from a lot of things, but your ethos, Jackson, has been a big part of it. You can make an inference just looking at all the teams you coach and how they’ve grown.

I also wanted to reculture us a bit around sports. The Commonwealth of my era was often full of eye rolling and mordant self-deprecation about our poor sports performance, and, for some kids, that attitude became self-fulfilling Today, we really are conscious—you, most particularly, Jackson—about saying, “Look, you don’t have to love sports, but it can be a wonderful experience; just give it a try.” You’ve really built a really supportive culture, and the numbers reflec that.

JE: Thanks! Yeah, we’re not trying to prepare our student athletes for playing competitively at, you know, an NCAA Division 1 school. The lower stakes mean everyone gets to play, which is not always the case at more “serious” sports schools or even in college. My senior year here, I played Ultimate Frisbee for the firs time, and years later, it’s still one of my favorite sports. Students can start a lifelong relationship with a sport or fitnes in general. It’s really about helping them fin a positive environment and experience playing a team sport, because that’s just a great way to fin community and joy in high school and beyond.

JB: I certainly see athletics strengthen the sense of community here in all kinds of ways. It’s an opportunity for wonderful cross-grade connection. That happens elsewhere at Commonwealth, too, but, on a team, ninth graders start to feel appreciated and have easy mentoring connections to older students. And the older students step into these leadership roles, and they have a great esprit de corps at recess announcements, where they’re shouting out each other’s

goals or reminding the rest of us to go to games. Like you said, there’s a joyfulness and a sense of connection within and across teams.

JE: So, I played soccer and basketball all four years here, and my sophomore and junior years, I played baseball in the spring. I found a great group of people doing all of those sports, and that community would actually extend to things like chess club or acting in plays. It was a great way to meet people across grades. It’s also a way to connect beyond screens and relax, and I think both students and families are looking for that. Spectating a game is a chance to cheer on not just their student but their team.

What about those students who are looking for a more competitive athletic experience or who perhaps already have that long-standing interest in a sport?

JE: We do have some really high-level athletes who work with coaches outside of Commonwealth in addition to or instead of with us. I'm thinking of fencing, specifically

because we have a few fencers who compete in the Junior Olympic circuits and things like that. They put in a lot of hours each week, and we want to make sure they can continue to pursue those goals, and that’s why we have our independent sports option [wherein students get approval to continue working on an outside sport in lieu of a Commonwealth team]. We also try to fin ways to celebrate their accomplishments in the community. We have a senior who’s a competitive sailor and made a national sailing tournament this fall, and we’re lucky to have a sailing team that he can participate in in the spring as well.

JB: We have a rower right now who was in the Head of the Charles, and we’ve had dancers who’ve pursued ballet and other forms of dance pretty seriously outside of Commonwealth. Every Commonwealth student does a lot of really careful time management, but those athletes in particular walk a razor-thin edge. It’s impressive.

JE: Those are the kind of pursuits, whether they’re academics or sports, where determination and discipline pays off, including i other areas of life.

Boston is our campus, including for sports; can you talk about the role the city plays in shaping the athletic experience at Commonwealth?

JB: It’s a gift and a constraint!

JE: Yes, exactly! There are a number of huge benefits to our location, and one i that we’re fairly central. That means there are lots of opportunities around the city we can take advantage of and that students can get to relatively easily. We sail on the Charles and climb at Rock Spot [in South Boston], and we use basketball courts at local universities, which can be really exciting, because they’re designed for high-level athletes. It also often means we play at multiple facilities, and students have to pay attention to their schedules and announcements, so they can keep track of all the different places

JB: It is amazing to have the Esplanade as our backyard. Some sports, like cross country or Ultimate Frisbee or soccer, are a hop, skip, and a jump away. Some are farther afield, lik fencing, and that really is a challenge. And some sports are held in the building: yoga,

“ I found a great group of people doing all of those sports [as a Commonwealth student], and that community would actually extend to things like chess club or acting in plays. It was a great way to meet people across grades. It’s also a way to connect beyond screens and relax, and I think both students and families are looking for that.”

ballroom dance, Latin dance. When I was a student, we did Taekwondo in the library, which was really transformative for me!

JE: With fencing in particular, we want to be able to send a full team—about thirty fencers at a time—and there just are not that many studios with that kind of capacity. Adding climbing as a winter sport was big for us, and we can send a lot of students to Rock Spot because they have the capacity. It’s been very popular; students even ask about it in admissions interviews. So we’ll see what the next rock-climbing “hit” is. I’m always looking at what else we could offe.

What are your hopes for the future of our athletics program?

JE: I want us to see how we can improve the player experience by providing leadership training for students who want to take on larger roles on teams and by adding more professional development for coaches, so they can better support the growing number of students participating in their sports.

In terms of our other offerings, we’ve overhauled the fitness program this year so students are getting individualized workout plans tailored to their goals, as opposed to everyone taking the same class. We’ll see how that goes. I’m excited about the potential. I think the spring season can continue to be flexible, because its generally an optional season. We have Ultimate Frisbee, competitive sailing, Girls’ Volleyball, running club, and yoga. If there’s a high level of student interest in another sport, we can see if that’s a possibility. That’s what happened with Girls’ Volleyball [new as of 2024].

You both came back to us as alums; how does it feel working at the Commonwealth of today?

JE: In terms of athletics, it’s really interesting to coach against all of these schools I played as a student and doing so with the broader perspective of knowing what goes into all of these sports. It also helps me appreciate what Meagan Kane [the librarian and athletics director when Jackson was a student] was doing and all the other hurdles she faced back then: like, we did not have a home field for socce, so we had to take a bus to Daly Field and bring our own nets; we had to jog to Magazine Beach [two miles away] for practices. So things have changed a lot since then, and I appreciate those hurdles a lot more now.

JB: I often observe and reflect on the fac that Commonwealth is an even better school than the one I went to. The things that were amazing and transformative and inspiring then still are, and there is so much more to offer students no. Forty years ago, I had some really fun athletics experiences: as I said, Taekwondo was amazing, and I laughed a lot with my friends about how completely inept I was on the basketball court. But there was certainly no such thing as an athletics director, and there really wasn’t a culture that embraced and supported athletics participation when I was a student. So it’s been a privilege to nurture both our traditional strengths and grow in other areas, and I think students—not every kid, but a whole lot of them—really like the opportunities they have in our athletics program. t

Commonwealth authors and editors reflect on their pactices and the outside forces that have sustained— and eroded—their work

BY CLAIRE JEANTHEAU

The student arrived twenty minutes late to class—“waltzing in,” veteran English teacher Mary Kate Bluestein recalls. But as he strode into the room, he exclaimed to her by way of explanation: “I was reading Chapter 39! I forgot to get off the T!

That would be Chapter 39 of a Commonwealth staple, Dickens’s Great Expectations, in which Abel Magwitch (“Pip’s scary guy that leaps out from behind tombstones–slash-benefactor,” as Kate refers to him) reveals himself for the first time on Pips doorstep in London during a midnight thunderstorm. While surprised, Kate could understand why the student, catching up on homework on his commute, missed his stop: “It’s just a humdinger of a chapter.”

When was the last time you were lost in a piece of writing so deeply—missing-your-T-stop, under-the-bedsheetswith-a-flashlight deeply? Last fall, an Atlantic article, “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” with its claim that (as of 2022) 11.5% of high-school seniors didn’t read a single book for fun over the course of a year, sparked discourse among writers, publishers, and educators alike. Suspected culprits for the low numbers abound: social-media oversaturation, reliance on AI-generated summaries, a decline in reading full novels in English classes, even brain fog from COVID-19. Regardless of explanation, there’s a fear that the total focus Kate’s bookish student once enjoyed is a thing of the past.

In this moment, Commonwealth alumni/ae who work with language, from novelists to medical editors, grapple not only with holding readers’ concentration but holding onto their own habits of mind to overcome distraction. We turned to them to rediscover what’s distinct about the sustained attention of a Commonwealth English class, what we lose when it’s gone, and how—in writing and life—we can keep cultivating it.

“Let It Happen”

The Commonwealth English class of 1975 was “really not that different” from one decades late , remarks Kate, now retired, who spent more than forty years teaching. Indeed, alumni/ae throughout the generations, when asked about

reading and writing at 151 Comm. Ave., invariably turn first to names those of teachers (John Hughes and his small third-floor classroom Brent Whelan and his Hemingway pastiche assignments) and authors (Yeats, Shakespeare, Auden).

Then come the lingering images: the paradox of being “free” while “imprison[ed]” in “Batter My Heart, Three Person’d God” by John Donne; the omniscient eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg’s billboard in The Great Gatsby and Daisy’s tears at Gatsby’s rich and multicolored shirts. It’s a trove stockpiled from years spent close reading, the Commonwealth mainstay of focused study of authorial choices and textual structure. To hear it described, though, is to learn less about specific literar terms and techniques and more of a way of being.

“The way that I think about how close reading is incorporated into my life today is the same way that I think about how studying French grammar might be part of how I would talk in French,” says author Ottessa Moshfegh ’98. “It’s part of how I write. It’s part of how I hold words in my head and how I listen to people when they’re talking.”

Judith Siporin, whose tenure as a Commonwealth English teacher also lasted more than forty years, is adamant about this point: that close reading is much more than a “catchphrase” or a single analytical technique. “It’s a whole complex of attitudes that are involved and parts of oneself that are engaged in it,” she insists.

Or, as Ottessa puts it: “There is this element of appreciating the miraculous at Commonwealth.”

The miraculous can be humbling. As a writer, where to begin? How to describe what compels you about a detail in the text that seems striking, profound—maybe even ridiculous? “It's not that you don’t have large ideas. You just don’t start with those ideas—you don’t come in with any baggage at all. You leave it all behind you, and you try to come free,” Judith explains. “You let it happen to you. You don’t impose your ideas on it. And then you try to write as directly about that experience as you can—without jargon, without highfalutin literary terms.”

Alina Grabowski ’12 published her debut novel, Women and Children First, during the summer of 2024; the first time she learned to linger wit sentences and consider their underlying meaning, she says, was at Commonwealth. The philosophy of “let[ting] it happen” has entered her own craft. “When I’m working on fiction, I oftentimes dont even really know why I’m drawn to what I am creating. If I go in with a preconceived notion, it quickly reveals itself to be faulty or flimsy in some way,” sh reflects. “I think writing, for me, is following these obsessions or interest that have to be revealed through the work itself.”

Women and Children First traces the lives of ten female narrators following the death of a young woman in a tight-knit Massachusetts coastal town. Following each perspective, wherever it might lead, guided much of Alina’s writing process. “It’s very character-driven,” she says. “I think all of the women, in some way or another, are stuck in their lives.” As she probed each narrator’s past, Alina asked herself: “‘Why is this character like this? What are the circumstances of their life and the way that they’re currently leading their life that lead to their current situation?’”

But curiosity is never the final aim, whether in Commonwealth Englis class or when alumni/ae write.

“It always started there, but it would never end there,” observes Alex Star ’85, an executive editor at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. “The point wasn’t just to read and ooh and ahh and gasp in appreciation. It was hard work. Then it became puzzle solving.”

“If the writer is doing a good job—which, in everything we read at Commonwealth, that was the case—you can go back and figure out th underlying mechanics that allow you to be immersed in the scenery of a particular scene or that make a character seem so alive to you,” Alina says. “Oftentimes upon your first read, you sense those things, and the you’re able to go back like a little detective on the trail and figure out What actually led me to that impression? Was it because of a staccato succession of words? Was it because the colors were really exaggerated in the writing, and the scene felt almost psychedelic?

“These are the individual bricks of the work,” she finishes. “And if can see how all the individual bricks fit togethe, then I understand how the whole house is built.” Alina echoes author and naturalist Annie Dillard in her memoir The Writing Life, comparing each line written to a “hammer” testing the potential shape of a piece: “Some of the walls are bearing walls; they have to stay, or everything will fall down. Other walls can go with impunity.”

Learning to test for those walls—uncovering, and then writing, a coherent argument—remains a hallmark of the curriculum. Michael Samblas, who teaches tenth-grade English at Commonwealth, directs his students to mark down every reference of devils, demons, or Satan in their readings of Frankenstein: “That gets them really thinking, ‘Wow, this isn’t just occasionally referencing Paradise Lost.’” When they turn to Their Eyes Were Watching God—which begins with protagonist Janie reclining under a pear tree as a girl—they search for the images of flowering plant that signal Janie’s blossoming into a woman. On an initial read-through,

Michael says, “you might not know that this detail matters, but when that detail shows up twenty times, then it stops being coincidence.”

As Alex edits nonfictio books that span the breadth of global history, politics, and beyond, he identifie similar patterns in how each author marshals their points, which guides him as he helps hone their writing. “It is important to really think about the arguments and how well-grounded they are in evidence and how persuasive they are and just how interesting they are,” he says. “That close attention to language and tone and structure and ambiguity that Commonwealth gave me is completely essential to just being a good editor.”

That testing doesn’t just strengthen analysis. It also builds a kind of courage as students, sometimes in dialogue with their peers or teacher, go out on a limb, attempting to position themselves from a differen viewpoint.

Ottessa can pinpoint the exact moment when she took a risk on writing in her own voice, rather than in her image of a “good student,” in an English paper for Eric Davis. When he handed back her essay, she remembers, he had highlighted the spot where her self-expression was most marked, praising her and saying he’d keep a copy for his files “That was the class where I really started talking more and felt like I could have a voice,” she says, the class where she could “explore without needing to be right or wrong about how a sentence might have moved me to think a certain way.”

Ottessa remains a risk-taker, with her narrators—cynics and paranoiacs, criminals and would-be detectives—transgressing many readers’ social boundaries. (Recent senior speaker Tien Phan ’24 gave her 2018 bestseller My Year of Rest and Relaxation a shout-out during graduation, noting that close reading helped him understand the underlying emotions of, in his words, a “resigned but manic” protagonist.) As a writer, she feels it’s “extremely important” to be sensitive to the idiosyncrasies of each character.

“There are so many micro-decisions that we’re making at any given moment—when we’re describing something or trying to give an opinion or asking for something—that are particular to us. They inform whoever’s listening, in a very specifi way, about who we are and how we think and what we want—and they also might convey ways that we’re trying to manipulate you,” Ottessa says. “The peculiarities of a voice can come across sometimes in really clear and obvious ways, and other times they’re more obscure. And the subtlety, I think, is the really challenging part of character and storytelling.”

Judith, approaching from the reader’s angle, appreciates the provocative characters that emerge from those efforts “In some works of fiction when you’re reading closely, you begin to realize that you can’t really trust the narrator,” she observes. “He’s obtuse. He’s missing things that you get. Or he’s maddening. He says outrageous things, and you know, ‘Oh, he’s at it again. Impossible person!’”

There are moments, too, when an “impossible person,” like an unreliable narrator, lurks in our own internal assumptions. A new student, transferring from another school, arrived in Kate’s eleventh-grade class as a “‘no, I don’t do poetry’ kind of a guy,” she remembers. “He clearly thought that poems were for ladies with flu� hats and teacups in their hands”—until the day they dove into a complex sonnet about despair.

“He just looked at me like, ‘Oh my God, this is about the real thing,’” Kate says. The student’s transfer to Commonwealth had been spurred by personal tragedy, and he connected the poet’s anguish with his own. Engaging with the writing on its own terms, Kate believes, enabled his breakthrough. “It wasn’t me saying to him, ‘I know you’ve really been through a tough time, and you might like this poem because it’s all about getting through tough times,’” she says. “He would’ve just rolled his eyes.”

Kate herself was once frustrated by undergraduate English classes where she read about many authors, but examinations of their works themselves were few and far between. “They were just teaching us the Norton Anthology generalizations about what we were reading—you read Marvell, and you fin out something about seventeenth-century poetry,” she says, her disappointment still unmistakable. Later, while earning her Ph.D. in English at Boston College and during her firs years teaching, Kate—like Ottessa and like her once poetry-averse student—would plumb for multivalent voices and motives that weren’t always evident at firs glance.

As these writers describe the mindset they nurtured at Commonwealth—open, constructive, attuned to the layers of others’ perspectives—several are concerned about its erosion.

Before Alina published her firs novel, she taught English; her students seemed increasingly “resistant” to drawing too much from a work of literature. She worked to show them what could be gained from spending time with each text—that “if we look at the repetition and why the comma is in this place as opposed to that place, and why are the tense shifts there, it will crack open the whole work for you.” But the typical response

was “‘You’re reading too much into it,’” she says. “The way that teens live is so utterly different from what my teenage experience was like i terms of social media and how students engage with text.”

Introducing a deeper level of analysis comes with a learning curve under the best of circumstances. “Students will always wonder, ‘Do I know that this actually does have this deep, significant meaning, an I’m not just blowing smoke or making mountains out of molehills? Why do I know that this detail matters?’” Michael says. The instantaneous availability of information (and misinformation) online, however, gives the issue a new urgency. “When students feel like they can get an answer or an essay question about a text using [artificial intelligence], says Alex, “the idea of just reading that closely is really endangered.”

Alex is wary of the kind of “transactional” approach to language this can engender, where the main goal of reading or writing is to “take a message away”—closing off possibilities for how initial expetations might change over time. “The message is going to be flawed,” he argues, “if one isn’t grounding it in the sort of tactile realities of what a text is.” What do those realities look like? Alina contrasts “Googling in five minutes” with investing time in “a novel talking about three generations of a family,” for example, or a complex academic theory. “That is so many hours someone has spent wanting to impart something,” she says. “You just get such a deeper understanding of things, I think, if you’re willing to engage closely.”

It’s not just a problem that plays out in English class. “There’s a lot of talk about how media literacy is in trouble,” Michael notes, especially considering that “kids today are being advertised to pretty constantly.”

“That’s the danger of the Internet,” Judith adds. You need to continuously ask: “‘Who’s telling me this? What’s the motivation behind this? Is this evil? Is this mere fact, or is this really skewed?’ That’s an important thing in life, generally, apart from school.” Words always have someone behind them, whether that’s a direct copywriter or the programmer of an answer-generating chatbot. Without slowing down to parse their thinking and motivations, a lot will be missed.

Kate once entered her classroom after school to find a young woman copying out a string of words over and over. Asking the student what

she was writing, Kate learned it was a poem she’d been asked to discuss in a written response. “I see more in the poem if I literally write it,” the student had explained. “I actually put the words down with my hand in my handwriting.”

“I thought that was so striking. I’d never heard that said before,” Kate says. “She knew that was a way of being present in the piece of writing.”

If quick answers threaten deeper understanding, how do alumni/ae writers engage with their own craft? Kate’s student’s practice points to one answer: complete immersion.

“I routinely, repeatedly revise my poems, often as many as thirty times or more,” says Michael Ansara ’64, an author who has introduced numerous students to living poets as a founder of the nonprofit Mass Poetry His memoir, The Hard Work of Hope—a work nine years in the making, detailing his decades of activism in the anti-war movement and political reform—will be published in 2025. When he speaks of developing that work, along with an earlier volume of poetry, What Remains, he dwells on “endless revision” and the cycle of “cut, rewrite, and cut again.”

“I had to learn to be willing to go where the poem wants to go,” he says, evoking Judith’s approach of “leav[ing] it all behind you and try[ing] to come free.” He also had to learn how to create his own “psychic space” for his work that would be separate from the world—a marked contrast from digital settings that can bombard users with notifications and up-to-the-minute news. “I cannot write and be thinking about the news, emails, taking calls, or wondering how the election will turn out,” he adds.

Liz Pease ’93, a senior medical editor at Eversana Intouch, also stands by the close re-read—even when her subject matter would ordinarily make her switch television channels. “You know those lists of side effects at the end of drug ads? I read those, sometimes over and over and over,” she says. An early role as an editorial assistant at an educational development house first pointed her towards her twenty five-year career in proofreading and editing

For Liz, the skill feels partially intuitive (“I seem to have been born with something that just makes errors stand out to me,” she muses), but practices like reading aloud—“even punctuation” and especially “if I know I’m losing focus or getting tired”—help her “make absolutely sure I’m not missing things that are easy to overlook.” It’s a strategy that goes

back to Commonwealth: Alina does the same with her writing, noting that Judith was her “first advocate” fo never keeping background music on while making edits.

As for current classes, Michael Samblas says, “I really like that Commonwealth students seem to still take personal pride in being able to write and take writing seriously as a skill they want to learn rather than just do well at for grades.” He’s organized his instruction to place greater emphasis on face-to-face interactions in small groups over individual assignments, encouraging students to try their theories on each other rather than first turning to search engines. And hes introduced weekly writing assignments—each about a paragraph in length—to encourage continuous reflection about each work that students encounter.

Given the “transactional” relationships to information he’s noticed, Alex wonders whether it might become “a little more difficult” to find the broad audience suppo for the kind of nonfiction he specializes in at Farra, Straus, and Giroux. But he still believes that the valuation of good writing hasn’t disappeared yet.

“I try not to be too deterministic or declinist about it,” he says. “It’s much easier to notice when someone is looking at their phone when they could be reading and being annoyed by it, and much harder to appreciate that someone actually is reading and getting something out of it.”

His optimism isn’t unfounded. Several years ago, Judith, along with her husband, Eric Davis, and former Head of School Bill Wharton, ventured to Palo Alto for an alumni/ae gathering. Her apprehension rose as she wondered how this group of language-minded faculty would address a guest list that included senior leaders at Google and other major technology companies. As an icebreaker, Bill asked alumni/ae what part of their Commonwealth education had the most value in their lives beyond the school.

“Most of the people who spoke,” Judith recalls, “said it was the English department and learning how to write—how it had been invaluable and what a rarity it is in the tech world and how they had been sought out and valued at their jobs. We were astounded. We thought we would have nothing to say to one another, but afterwards we had many wonderful conversations and were so happy to have made this unexpected connection.”

It’s the “teaching of being fully present” at Commonwealth, Alina says, that is so enriching—in working with language and in any other aspect of living— and that will endure over time.

“I think we’re all, unfortunately, pulled in many directions, but that way of giving attention to something, whether it’s a conversation with a friend or looking out your window and admiring how your garden has grown…it’s applicable, essentially, to everything in life.”t

Claire Jeantheau served as Commonwealth’s Communications Coordinator before becoming the Marketing Manager for the American Exchange Project.

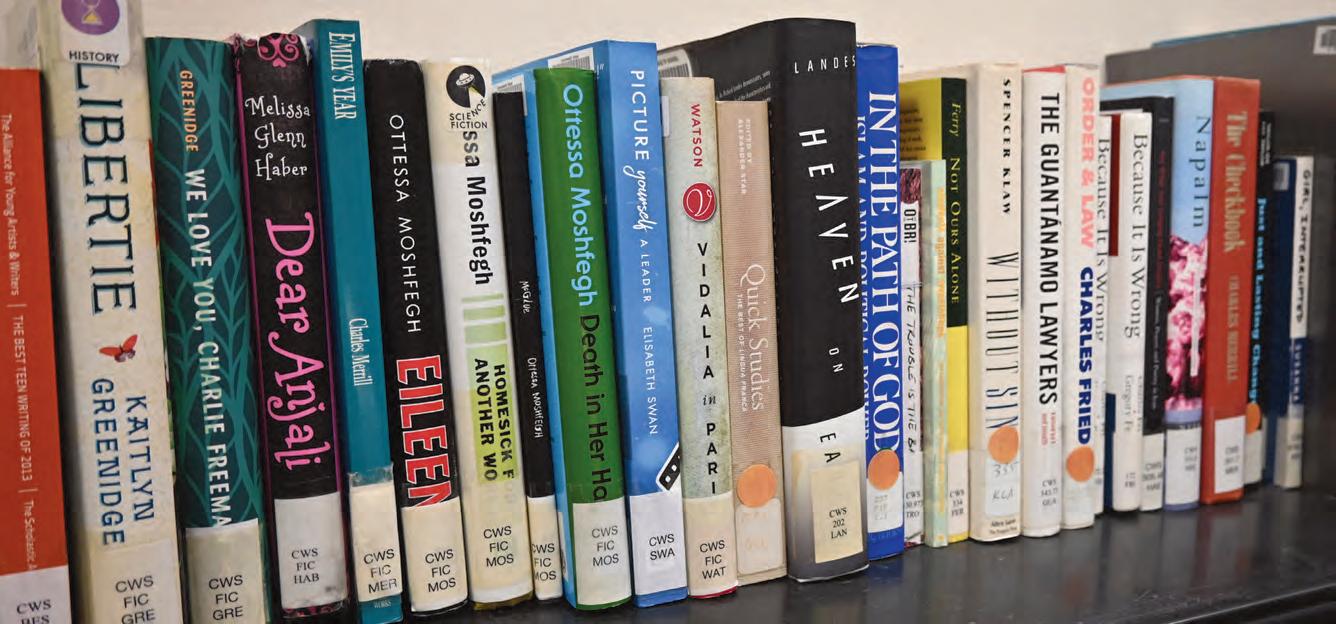

Hoping to spend more time with the written word this winter? Peruse these recommendations from teachers and alumni/ae, who share why they were compelled by each work’s style.

n Mary Kate Bluestein: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout; the novellas of Claire Keegan. “They’re succinct. They’re incredibly pure and simple. And so much is implied by very little. Very measured but not cold; you feel as if what they’re describing is full of meaning and depth, but it’s very simple diction. They’re terribly moving books and I go back to them repeatedly.”

n Alina Grabowski: “Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting is probably my favorite thing that I’ve read this year. It’s this sprawling tale of a family and particularly the father, Dickie, at the center; his shame clouds everything that happens. That book is cinematic and visual while still having enormous emotional resonance and an incredible ability to depict one’s interior life. I also reread Jazz by Toni Morrison. It’s just so cool in terms of how it moves and how flexible and kind of wily the narrator is.”

n Ottessa Moshfegh: Flesh by David Szalay (coming spring 2025). “The way that this writer writes is so intimate and funny in a way that is also just uncomfortable and personal enough for me to feel like I’m the only one who will ever read this book. It’s very special and strange.”

n Michael Samblas: The works of Nicolás Guillén, an Afro-Cuban poet, translated by Langston Hughes. “My specialty is Caribbean literature and particularly the Hispanophone Caribbean. Hughes tries to find ommon ideas in race discourse in the U.S. and Cuba. But then there are racial ideas in the Caribbean that don’t translate well to the U.S. How did Hughes try to plug those gaps? How does he try to bridge those divides through language? That’s been the most interesting stuff for me”

n Judith Siporin: The Diary of Helen Morley by Alice Dayrell Brant. “It’s an actual diary, written by a Brazilian girl in the nineteenth century, self-published under a pseudonym. I first got inerested in this book, which I discovered at a used bookstore, because it was translated from Portuguese by the American poet Elizabeth Bishop, who lived in Brazil for many years. The voice of the girl who wrote the diary is completely unself-conscious, fresh, original, and audacious….she brings to life the remote town, Diamantina, where her impoverished family lived and its dream-like mountain landscape where there are diamond mines and diamonds could be found lying on the ground.”

n Alex Star: “I’m reading a lot about Germany lately, because I’m here for the semester. The Pity of It All by Amos Elon is an exquisite book of cultural history, a history of Jews in Germany—from the eighteenth century up until the Nazis, but really focusing on the nineteenth century and artists and writers and thinkers and assimilation at that time. It’s very fluently writen; I just wanted to hold on to almost every paragraph.”

BY BECCA GILLIS

W

hen you’re eighteen years old, a college major can look like a lifelong commitment. Up the ante to graduate school, and it feels like there’s even less space to diverge from one’s chosen path. But these four Commonwealth alumni/ae took the plunge, pivoting after their postgraduate studies to pursue newfound passions—or ones that were waiting for them all along.

These days, Joe Reid ’75 begins his mornings practicing Chopin or Mozart, warming up for the day before heading to a gig, helping students perfect their technique, or some of both. But forty years ago, Joe couldn’t imagine his love of music paying the bills.

“I grew up in Cambridge with two doctors as parents,” Joe says. “And so you think, ‘Okay, law school or medical school, maybe business school.’ It was a cultural thing: unless you’re going to be Yo-Yo Ma, don’t be a musician.”

With a natural interest in policy and a brief stint on Capitol Hill under his belt, Joe decided to go the J.D. track, graduating from Northeastern University’s School of Law in 1985 and kicking off a fifteen-year career that never quite seemed to fit. “I was very tense lot of the time for different reasons,” he recalls of those days, when his work primarily entailed corporate law and real estate. Between the demand of a competitive job reliant on perpetually bringing in more clients and frustrations over the need to “chase the money” through obligations like golf outings with the mega-wealthy, the burnout became unavoidable by the late 1990s. “I wasn’t happy,” he says.

But what to do with a law degree and a career fifteen years in the maing? It was a question of “figuring out what I really like to do,” Joe says and, despite a certain amount of eyebrow raising from the people around him, Joe decided his future lay in the passion that had been a source of joy and identity for him since his days at Commonwealth: music.

“The musical environment of Commonwealth was life changing for me. I was sort of known as a musician there,” he recollects. “I was in the Orchestra, the Madrigals, the Jazz Band. It was a perfect storm: wonderful music teachers, enthusiastic and talented classmates, and opportunity. I wrote my college essay to get into Harvard about my experience of Commonwealth Orchestra and Jazz Band. I realized that that was me; where I was mentally at Commonwealth, I came back to that.”

The challenges of pivoting to a career in music when his entire adult life had been spent in law were not lost on Joe, but, as he describes it, he decided he’d simply have to put in the work as if he had gone to a conservatory instead. “I basically said, I am going to do this no matter

what, and no one is going to stop me,” he says. “I lost a certain number of years not working on my technical abilities, but at some point you just have to not look at that and work on your strengths.”

That’s exactly what Joe did, focusing all his efforts on polishing the piano skills he’d been honing throughout his life. As performance opportunities began to multiply, he soon distinguished himself in the Boston area as a respected jazz musician. Now, in addition to teaching piano at the New School of Music in Cambridge and from his Belmont home, Joe plays around 150 gigs per year for jazz clubs, churches, choirs, and more.

Between practicing, teaching, and gigging, Joe estimates that he spends more hours per week on his music career than he did on his legal practice, but says the stress that once consumed him has largely melted away as he’s taken on work that feels true to who he is. Settled into a life centered around the craft he’s held most dear since high school (and, he notes, even recently included reuniting with saxophonist Paul Klemperer ’75 for several gigs), Joe urges young people—and people of any age—to not be afraid of the hard work required to make a risky career move, echoing his own mantra from when he decided to make music more than a way to unwind from a day at the law firm: “I want to do this. I’m not afraid. If you’re telling me this is a bad idea, I’m just going to work harder.”

“‘It’s always about noticing,’” Natalie Mills ’13 recalls Commonwealth art history teacher Judith Siporin telling her students. “‘What do you notice? What do you see?’”

Natalie fell in love with noticing at a young age, entranced by trips to art museums with her parents. After taking two impactful art history classes at Commonwealth, her passion for the subject and determination to pursue it further solidified. But the journey wasnt quite how she pictured it, beginning with her unexpected major in religion, given her Christian iconography–heavy classes. When her advisor suggested she look into divinity school, Natalie struggled to picture herself in that environment, imagining classrooms full of aspiring clergy. Even then, her philosophy of studying art history guided her thinking: understand

context to the fullest extent possible. “I was trying to be like an anthropologist,” she says. “I don’t think you can view something that was a religious icon and used in prayer in a secular setting.”

So Natalie enrolled at Yale Divinity School, which offered a progra covering both art history and religion. It wasn’t a fit. While Natalies studies continued to fascinate her, the cultural mismatch between her and the school came to overshadow her love of the work, and she began to doubt her plan to pursue a Ph.D. and become a professor. “Every piece of advice I got from professors and advisors was that if you’re not 100 percent sure [about getting a Ph.D.], don’t do it,” she says. “It left me being like, ‘I don’t know that this is what I want.’”

In the wake of that uncertainty, Natalie experienced what she calls a “classic COVID pivot” following her graduation from Yale in 2019. She moved to California, intent on spending a year seeing where life would take her, but the places she expected to find work, like museums soon shut down due to the pandemic. “I had to get really creative and be like, ‘Okay, I guess I’ll just get a job and start somewhere,’” Natalie recalls. She soon accepted a position at a small tech startup, where she enjoyed her ability to do “a little bit of everything” and especially liked her work managing the company’s social media presence. But, once

again, Natalie found herself in a culture didn’t quite suit her. “It felt like it was missing the beauty, the visual world, all of those things that I loved so much,” she says.

In the summer of 2022, Natalie happened upon an opportunity to bring the visual world back into her work in a way that resonated with her, when she began her current position as social media manager of Garnet Hill, a clothing, bedding, and home-decor company. Her daily projects range from directing models and photographers at photo shoots to writing up analytic reports to creating slide decks for brand campaigns and everything in between—and she says her years studying art history are surprisingly relevant to all of it. “It’s an art form in its own right to set everything up and style things so beautifully. When you spend hours looking at paintings, you find the beauty in things, o you see why someone did something the way they did, and I think it feels very similar with the images Garnet Hill creates.”

Looking ahead, Natalie sees a position as an art director in her future, building on her current role to focus her efforts on directing and fine-tuning details to capture the perfect picture, enveloped in a world built on noticing.

Some people end up in postgraduate programs because they’re following a clear, standard path, destined for, say, med school from that freshman-year Anatomy 101 class. Alexander Droznin-Izrael ’11, however, landed in his for quite the opposite reason. “Everyone knew I was a pre-med; it seemed like all my friends were on that path” he says. “I liked the idea of pursuing something non-standard.”

Having majored in Russian in addition to biology, he enrolled in a Ph.D. program in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Harvard. But as much as he enjoyed the subject material and his work teaching undergraduates, he couldn’t shake the feeling that a lifetime in that field would feel disconnected from much of the world, an medicine crept into his thoughts again. “Looking at my background, I’m thinking, “‘Okay, do I want to teach ten college students a year, or do I want to see hundreds or thousands of patients a year and help them get better?’” he says. “I felt that I could make a greater difference in medicine.

Still, academia would retain Alexander for two more years as COVID pummeled the world and its hospitals, making it difficult f him to acquire the clinical experience necessary to apply to medical school. He exited his Ph.D. program in 2022, prior to completing his dissertation but having secured a master’s degree and a plethora of teaching experience.

Now, with two years of clinical work completed, Alexander is in the midst of his first year of medical school, which he describes as “both fascinating and like drinking out of a fire hose.” Despite the long hours and the host of minute details and complex systems to commit to memory, his excitement about the dawn of his medical career—and the change he may effect with it—is palpable. Alexander has a few years yet to determine his specialty (or to decide not to specialize), but he keeps returning to oncology, an area of medical advancement he likens to HIV research in the 1990s in its potential to transform a death sentence into a manageable illness. “So much of [medicine] is about alleviating suffering, at least in one context,” he says. “How wonderful is it to be part of a community that’s tasked with reducing suffering? That, to me, is a blessing in this work.

Alexander may be close to a decade older than most of the students in his classes, but he says he has no regrets about his detour to grad school, as he values the life experience gained over those years and the opportunity to think in different ways, especially through teaching. He s discovered his time spent immersed in humanities work not only solidified his writing skills but also taught him how to apply close-readin practices: “When you read closely, you don’t want to lose sight of the whole thing. And I feel like that’s kind of what I’m doing here, too; yes, I’m understanding how individual molecules and proteins are working in a given mechanism, but I’m also trying to keep a broader sense of how that connects to the bigger picture of health and all of the social determinants that are related to a patient’s health.”

If Deborah Fryer (’81)’s professional and academic journeys demonstrate one thing, it’s the transformative power of stories—the ones we read, the ones we share with others, and the ones we tell ourselves.

Among the first stories to capture Deborahs attention were works by the likes of Ovid and Virgil, encountered and voraciously devoured in her Commonwealth Latin classes with Polly Chatfield. “I can still see he and hear her as we’re reading the Metamorphoses,” Deborah recalls. “I remember us weeping over how beautiful the language was.”

A self-described “free spirit” in those days, Deborah followed her love of classics wherever it might take her, from a six-month program on a Greek island working as a weaver’s apprentice to an eventual master’s degree in Latin and Ph.D. in Classics and Comparative Literature. Shortly before completing her Ph.D., she attended a conference on women in media, where she encountered a lecture on Aristophanes’s Lysistrata and the power of women to change outcomes—and in the span of one weekend, everything changed. “After this conference, I thought, ‘I want to do more than teach Classics. There must be something more that I can be doing.’”

Deborah sought advice from the conference’s organizer, who encouraged her to go home and journal about her dreams for the future.

One such dream: “I wanted to be a reporter for National Geographic,” Deborah says. “I wanted to travel the world, tell stories, take pictures, meet people.” Though not National Geographic, a series of connections soon led Deborah to NOVA and FRONTLINE at WGBH in Boston, kickstarting a twenty-year career as a filmmake. “I wanted to be known, I wanted to be heard, I wanted to feel like I had something valuable to say,” Deborah recalls. After going on to create films with programs like Discovery and American Experience, Deborah founded her own production company, Lila Films, in 2004.

Fast forward a couple decades in the filmmaking industry, and Deborah once again felt the pull to do something more, frustrated by the instability of her career. “I felt amazing and like I was contributing something of value when I was on a project,” she says. “And then the project would end, and I wouldn’t have any money.” Yearning for “real respect” and “real income,” Deborah pivoted to the medical field, completing a post-baccalaureate pre-medical degree

Her days in the anatomy lab taught her different lessons than she expected, however. While examining a heart that had suffered cardiac arrest, just one day after losing her father to the same ailment, Deborah says the sight of the unbalanced organ opened her eyes to the bigger picture of her life: “I could see that I had been running my business completely counter to the laws of nature. I wasn’t giving and receiving. I was doing a lot of pro bono work at the time, because I didn’t feel comfortable receiving money. I was pulling all nighters because I didn’t know how to say no. I was supporting, but I wasn't letting myself be supported.”

Deborah quickly realized the importance of mindset to one’s physical health—or, as she puts it, “the story [a patient] tells about themselves.” Intent on helping other women overcome their own mental barriers to success and wellbeing, Deborah jumped fields for the thir time, creating a program called “The Anatomy of Money.” The program tackles “how we think about thinking,” offering women differe somatic techniques and metacognition work to “get the mind and body on the same team.” Deborah has also recently incorporated creativity work, such as painting, to help participants employ both their minds and bodies to understand the patterns of their subconscious.

Despite the winding path her career has taken, Deborah recognizes a clear throughline from her graduate studies to each type of work she’s engaged with since. “I can see a direct thread from Ovid and the themes of our human potential to translate and transform and shapeshift throughout our lives,” she says. “Everything led to this moment.” t

Becca Gillis is the Communications Coordinator at Commonwealth.

BY LILLIEN WALLER

Rachel Albert ’93 is on a mission to end hunger by recovering waste and providing fresh, healthy products to food-insecure residents in Massachusetts.

The United States produces more than enough food to feed all of its citizens. The longstanding myth of scarcity is quite simply that: a myth. But if this is the case, why does food insecurity persist?

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), as of 2023, more than thirteen percent of American households—and thirty percent of Massachusetts residents—were food insecure, which means they lacked consistent resources to obtain nutritious, affordable food and were often forced to make trade offs between buying food and paying for other necesities such as housing, transportation, and medication. Food-insecure households are everywhere, in every community, including those perceived to be affluen

Rachel Albert ’93, Executive Director at Food Link, a food-rescue nonprofit in Arlington, Massachusetts explains that food insecurity is the inevitable outcome of economic and social policy decisions. “We talk about food insecurity as its own issue,” she says. “And I think that makes it a little more palatable, and it also makes it an issue that can be more unifying across political lines. But the reality is, if you’re going to trace its causes, it’s all economic,” referring to the deregulation, wealth inequality, low wages, and frayed social safety net at its root. “The bottom line is that food insecurity is no mystery to anyone. And the government has left the nonprofit sector to pick up the pieces.

Rachel joined Food Link in spring 2021 after many years working with mission-driven organizations, a decision that can be traced back to her Boston upbringing in a family that prioritized social justice. But her first passion—o, rather, parallel passion—was opera and performance, which she pursued while a student at Commonwealth.

“It really was, for me, a time of feeling like I had found my people,” she recalls of Commonwealth. “I felt as if I could be my nerdy self who wasn’t ashamed of being a good student and of wanting to learn. I found a lot of people who were intellectually curious, with a really wide range of passions and interests. My passion was to become an opera singer. And in my senior year, the wonderful David Hodgkins [Commonwealth’s Director of Music] noticed that we had just enough interest and talent in our small school to put on a fully staged production of Dido and Aeneas [an English-language opera by Henry Purcell], and I got to play Dido.”

Maintaining her interest in music, Rachel pursued a dual degree at the University of Rochester in psychology and vocal performance at the school’s Eastman School of Music. The realities of such a competitive field however, soon began to hit home. “You’re young, you’re idealistic, you think, ‘This is amazing,’” Rachel recalls. “You’re told you have talent. You win competitions. But in the opera world there are 100 people vying for every role. I hadn’t wrapped my head around that, and I didn’t understand the business side of things.

“My interest in social justice work was always there, this interest in trying to make the world a better place in whatever way I could. So I started to think, what would it look like to pursue this professionally?”

Rachel went on to earn advanced degrees in both business and social work from Columbia University, and her consulting work in strategic planning for such nonprofits as eterans Legal Services, Rhode Island Community Food Bank, and 2Life Communities would eventually lead her to Food Link. “What drew me to Food Link’s mission is that it employs an elegant solution: we’re basically working toward solving one problem—food insecurity—by addressing another— food waste.”

Founded by DeAnne Dupont and Julie Kremer in 2012 as the Food Recovery Project, Food Link rescues food from more than 100 supermarkets and other retailers, farms, and wholesalers and distributes their fresh,

“When you start breaking down the food system today, what you have is a lot of food being produced at scale in a way that is much worse for the environment and for people.”

high-quality surplus to food pantries, low-income housing facilities, after-school programs, veterans programs, group homes, addiction services, and other hubs in under-resourced communities. The nonprofit sort the food, composts what isn’t viable, and distributes the rest. “We pack boxes of only what each recipient agency wants,” Rachel says. “So, it’s a very individualized service. And we break down barriers to access by bringing the food directly to where people need it, so they don’t have to make an extra trip. It’s right there where they live or gather.”

Food Link accomplishes a lot with a little. Serving forty-six communities in Greater Boston, a staff o twelve and hundreds of volunteers distribute upwards of 1.4 million pounds of food annually to 100,000 people via 106 community-based nonprofits. o date, the organization has recovered more than five million pounds o food. But if more than forty million American house-

13% U.S. households that are food insecure

30% Massachusetts residents who are food insecure

33M Tons of food sent to landfills in the U.S. annually

holds do not have enough to eat—and forty percent of the food produced in the United States remains “unsold or uneaten,” according to the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC)—where does the waste come from? And more importantly, where does it go?

As with the parallel problem of food insecurity, the answers are complex. It starts in the home, where the majority of food waste happens, an accumulation of little losses—overbuying groceries, tossing leftovers— that seem harmless but add up significantly. Ther are non-human factors, too, such as crops that are rendered inedible by blight or mold. “There are many, many factors contributing to this,” Rachel says, citing consumers’ unrealistic cosmetic standards for groceries, long transportation times, and storage methods among them. Then there are less obvious factors, such as food expiration dating. There are more than forty differen systems, used on everything from eggs and dairy to bread and canned goods. These dates often have nothing to do with the actual shelf life of the product, and the lack of consistency from one brand to another confuses consumers, who throw away food that may continue to be viable for days or even weeks.

All of this food ends up in landfills or incinerator as part of the thirty-three million tons Americans waste each year, according to the NRDC: “What we toss contains enough calories to feed [food-insecure Americans] more than four times over.” The price of all this waste? $414 billion per year.

was reeling from a dramatically heightened demand for food. On one hand, Rachel explains, the organization was able to take advantage of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which funneled more than $550,000 into their budget. On the other hand, the staff was very quickly burning out. “Before I arrived, in late 2019, early 2020, Food Link was moving 600,000 pounds of food a year. Within a year, when the pandemic hit, that number doubled to 1.2 million, and now we’re at 1.4 million and rising.”

One of Rachel’s first goals was to stabilize things, “because we had grown so quickly and there was so much hustling going on. There were opportunities to recover food from parts of the supply chain that had never been available before,” she explains, due to the sweep of restaurant closures. “So there was lots of food available, and folks were scrambling to rescue it and connect it to the community.” Food Link and other nonprofits in the same space were able to take advantage of the surge in federal and state earmarks, as well as individual donations. And Rachel was able to shore up Food Link’s infrastructure during this period, including hiring more staff, so they could move more food.

$414B Cost of food waste in the U.S. annually

Rachel points out that the problems with how we waste food should be understood alongside the problems wasted food causes. Food waste in landfills is on of the largest contributors to methane gas emissions and is a significant driver of the climate crisis. “If foo waste were its own country, it would be the third-largest global contributor to greenhouse gases after the U.S. and China. But it hasn’t been talked about in the same way that we talk about fossil fuels and cars on the road. When you are looking for the biggest levers of change and what’s going to move the needle the fastest, addressing food waste should be right up there. Getting this waste out of our landfills has to be a climate priority.

The commercialization of agriculture is another huge piece of the puzzle, Rachel says, noting that most of us no longer live close to the sources of our food, so our instincts about what’s safe to eat have begun to disappear.

But it wasn’t to last. The ARPA funding has dried up, food costs have skyrocketed, and the net investment by the government into food programs hasn’t increased—the money has just been shuffled around Rachel also notes that the Healthy Incentives Program in Massachusetts, which was meant to double residents’ purchasing power of produce, was not refunded at the level necessary for families to make ends meet.

In the fight to decrease food waste and food insecrity, however, it’s not all bad news. As The Washington Post reported on a University of Texas study of nine food waste bans across the United States, aimed primarily at chain restaurants and grocery stores, “from 2014–2018, Massachusetts reduced its solid waste by an average of 7.3 percent.” And in 2023, Food Link participated in a coalition to advocate for a bill funding universal school meals in the state, which passed.

1.4M Pounds of food FoodLink moves annually

A small number of big corporations produce and control a majority of what we eat, Rachel says, with companies like Kraft Heinz, PepsiCo, and Conagra monopolizing everything from meat to cereal to toothpaste production. “Then factor in transporting it all over the country. When you start breaking down the food system today, what you have is a lot of food being produced at scale in a way that is much worse for the environment and for people.”

When Rachel arrived at Food Link in 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic was roiling, and the nonprofit

Rachel understands that it’s still an uphill fight, as food insecurity in the state and around the country continues to rise and food waste still piles up in America’s landfills. It is not, howeve, a fight that she, Food Link, and other food-based nonprofits are willing to give up on.

“Ideally, the numerous broken links in the food supply chain would be fixed,” says Rachel. “But until that day comes, I believe that Food Link’s approach of mobilizing a community of volunteers to recover unsold food is replicable to many other communities. That’s what I’m excited to think about next.” t

Lillien Waller is a poet, essayist, and editor. Her essays focus primarily on the intersection of art and personal history. In 2023, she was awarded an Arts Writers Grant from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts to profile interdisciplinary artists of color in her hometown, Detroit.

BY CATHERINE BREWSTER