Know Thyself

Commonwealth Physicians and Philosophers, Gamers and Public-Policy Wonks, Find and Make Meaning Across Disciplines

Commonwealth Physicians and Philosophers, Gamers and Public-Policy Wonks, Find and Make Meaning Across Disciplines

Istarted taking photography classes at Commonwealth about a year ago, maybe because I was drawn to the idea of working for National Geographic and becoming an intrepid explorer, or maybe just because it was a popular class my friends were taking. Regardless, photography has transformed my entire perspective and how I see the world when I step outside. I notice complementary colors, lines leading my eye to an object, natural geometric shapes, contrasts, and beautiful sunlight. I also see snapshots of the city that invoke a sense of loss of the natural world, and snapshots that make me want to celebrate Cambridge (my hometown) and all its eccentricities.

1When I originally took the photo of Brattle Square Florist (1), seen through its large window, on my phone, I wanted to capture how the rows of buckets full of flowers were each allotted to a tile on the floor. From my angle and perspective, the rows seemed to stretch on forever. I liked the man hunched over, studying the flowers, as if he, being now inside my photograph, was observing it from his own perspective. The reflection of the sky on the window also added another dimension to the photo, blending the inside of the store and the sign with the street lights and sign posts. Later, when I edited the photo in Adobe Lightroom, as my photography teacher Mx. Korman has been teaching us to do this year, it became infinitely better: I amped up the colors, making the flowers even more vibrant; I increased the exposure to make the lightbulbs shine; and I added a blue-and-purple tint to make it feel more wintery. I then created a mask that allowed me to edit just the sky to make it a darker blue, which added a lot more color. With a different exposure and color palette, the photograph felt cozier and a bit more exciting.

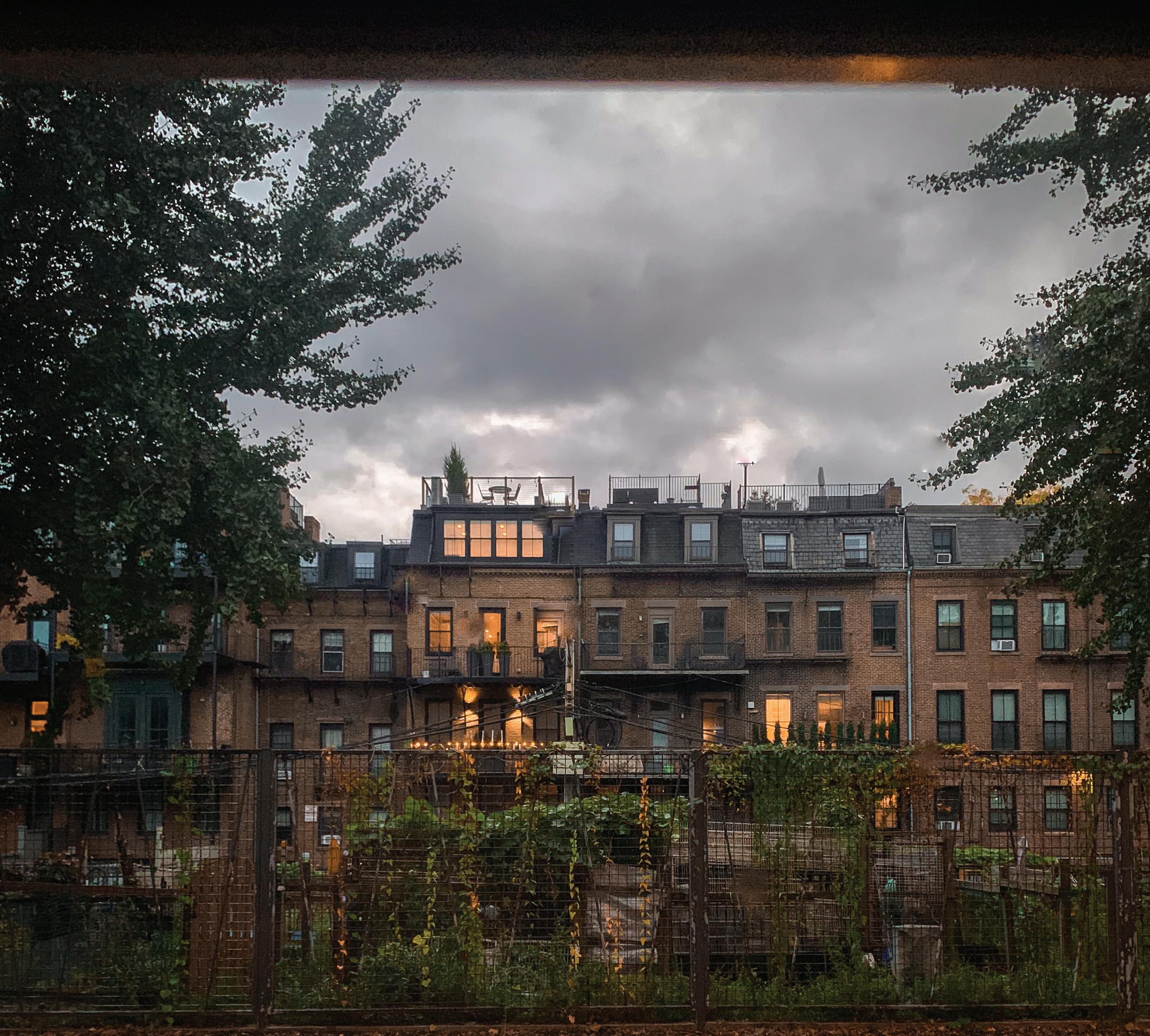

I took the photo of the South End of Boston (2), as part of a class project focused on commuting. I really like the composition and framing. There is a tree on each side of the buildings, a strip of sidewalk covered in leaves on the bottom, and part of the bus window protruding at the top and reflecting a yellow light the same color as the buildings’ windows. I also made the light a warmer, brighter yellow in Photoshop, so it seemed to spill out of the windows. I decreased the exposure of the sky so it was darker and the clouds stood out more, making the sky look stormier. I wanted the photo to appear as if it were a more fantastical version of Boston, a kind of just-discovered magical fairy realm, if you will. When I presented this photograph in class, someone said it “looked like Boston but also not Boston at the same time,” recognizable and yet foreign.

“ I see snapshots of the city that invoke a sense of loss of the natural world, and snapshots that make me want to celebrate Cambridge (my hometown) and all its eccentricities.”

Editing my photos on Lightroom has been really enjoyable. There’s something about being able to make my photograph look exactly like the image in my head that is so satisfying and fulfilling. Sometimes I stay up late, going over my photos from the week, mending them and giving them touch ups, organizing and reorganizing them by a five-star rating. I’ll leave comments to myself about what to continue working on the next day, when I’m in Photography class. Taking photography classes has allowed me to explore my city and the greater Boston area much more than I thought possible, and being able to capture it on film, to me, feels like the best way to experience it. t

Not infrequently, students will describe themselves to me as “a humanities person” or “a STEM kid.” While I know that adolescence is the continual process of self-discovery and self-definition, I still feel a small wince. I know they will enter a world where most work and most challenges require looking through multiple disciplinary lenses. I want them to stay expansive and flexible, even while they delve into their particular passions.

When I was a Commonwealth student, I, too, would have described myself as “a humanities person.” Math, in particular, was a constant struggle for me, despite the Herculean patience of my teachers. I didn’t understand at the time that confusion was intrinsic to real learning, and my angst became a selffulfilling prophecy. I preferred to play to my strengths and loves: the bottomless interpretative work of reading literature and engaging with language. Later in my career, I inched my way back into mathematics.

This issue of CM is replete with stories of alumni/ae and students whose work spans and blends academic disciplines or launches well beyond a particular academic boundary, whether STEM or humanities. You will read about the creative career paths of philosophy majors and find portraits of doctors who engage with politics and poetry in their work. You will get a taste of the domain-spanning work of video-game design. And you will get a glimpse into our students’ exciting projects and activities, from analyzing our school’s carbon footprint to Roosevelt and the Supreme Court.

Academic disciplines and subject matters can be powerful ways to organize knowledge, but they do not exist a priori. They are neither universal nor static. Some argue that they began in the Middle Ages when the University of France taught the trivium and quadrivium (including rhetoric, grammar, geometry, and music). The more traditional academic disciplines have their roots in nineteenthcentury German universities where the curriculum became more secular and expanded to include natural sciences, non-classical languages, and literature, for example. The twentieth century brought new disciplines such as psychology, anthropology, and women’s studies, for example. Walk onto a college campus today and you will find shiny new centers and institutes where scholars work across their areas of expertise to study brain science, media, or war.

As exciting as such collaborative centers can be, I find myself saddened to see the shakier state of the humanities at many universities. Not so at Commonwealth, thankfully. We remain deeply engaged with literature, history, philosophy, and language, within and across disciplines. We also remain humane in the deepest sense of the word. In this issue, my colleague Josh Eagle, Dean of Students, shares his work to ensure that each student is known, supported in a variety of tailored ways, and able to thrive here. Whether they identify as a “STEM kid” or some other initial label, each student here is in the midst of being and becoming. In the company of caring adults whose knowledge is wide and deep, our students are getting ready to join a complex world.

Jennifer Borman ’81 Head of SchoolCommonwealth School Alumni/ae Magazine

Issue 25

Winter 2024

Editor-in-Chief

Jessica Tomer

Editor

Becca Gillis

Contributing Writers

Jennifer Borman ’81

Catherine Brewster

Alisha Elliott ’01

Becca Gillis

Claire Jeantheau

Jessica Tomer

Lillien Waller

Contributing Art and Design

Alan A. Photography

Martina Ardisson

Margaryta Bushkin

Melissa Glenn Haber ’87

Mirabel Han ’26

Marc Robert Jeanniton

Eliza Lamster ’24

Chloe Li ’27

Danny McDonnell ’26

Printing Hannaford and Dumas

Sarah Rahman ’27

Tien Phan ’24

Mónica Schilder

Tim Daw Photography

Jessica Tomer

Tony Rinaldo Photography

Lillian Walsh ’25

Olivia Wang ’24

Ethan Wu ’26

CM is published twice a year by Commonwealth School, 151 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02116, and distributed without charge to alumni/ae, current and former parents, and other members of the Commonwealth community. Opinions expressed in CM are those of the authors and subjects, and do not necessarily represent the views of the School or its faculty and students.

We welcome feedback: communications@commschool.org. Letters and notes may be edited for style, length, clarity, and grammar.

Printed on recycled paper. Please recycle. @commonwealthalumniae

Another thrilling fall sports season has come to a close at Commonwealth! The Girls’ Varsity Soccer team dazzled us as they made the playoffs for the first time in more than ten years after finishing the regular season in third place, marking a huge step forward for the team. Boys’ Varsity Soccer qualified for the playoffs as well, and both teams made it to the semifinals. Lizzy Wakefield ’24, Elsie Shoemaker ’26, Beatrice Hsu ’27, Thomas Du ’24, Henry Levenson ’24, and Tomi Duintjer Tebbens Nishioka ’27 were all recognized as all-stars for their outstanding performance on their respective teams. Cross Country also made strides this fall, with the Girls’ team taking home second place in the championship and the Boys’ team placing eighth overall. Mira Haber ’26 scored a fifth-place individual finish, while she and Juliana Li ’26 were also recognized as all-stars. We couldn’t be more proud of all of our athletes, evident from the enthusiastic spectating by Commonwealth students, faculty, staff, and families throughout the season!

After making the jump last year from #24 to #9 among the Best Private High Schools in America, according to Niche.com, Commonwealth has once again risen in the website’s rankings to the #8 Best Private High School in America and #2 in the state of Massachusetts this year.

We’re pleased to share some other highlights from Commonwealth’s Niche rankings:

#8 Best Private High School in America

#2 Best Private High School in Massachusetts

#1 Best Private High School in Suffolk County

#2

#14 Best High School for STEM in America

#9 Most Diverse Private School in Massachusetts

This past summer, twelve Spanish students had the adventure of a lifetime as they journeyed to Spain to put their language skills into action. Accompanied by Spanish teacher and Co-director of Dive In Commonwealth Mónica Schilder and Director of Admissions and Financial Aid Carrie Healy, students visited sites like the Museo del Prado, Catedral de Granada, La Alhambra, and Alcázar Real. Throw in a flamenco performance and swimming in Málaga, and what more could you ask for?

Best High School for STEM in Massachusetts Ella Sherry ’25 Lizzy Wakefield ’24 Director of Athletics Jackson Elliott ’10 coaching the champion Girls’ Soccer team

Commonwealth’s identity comprises many parts: its small size and close-knit community, rigorous classes, expert faculty who truly know their students, recess, Hancock, and a host of other traditions. But our location in Boston’s Back Bay is another vital element of the life of the school that makes Commonwealth, Commonwealth. With this in mind, every ninth grader starts their Commonwealth journey with a ten-week City of Boston course, in which they learn about the history and current state of different neighborhoods, analyzing how and why Boston has changed over time while mastering city-life basics like navigating the T. Whether learning about gentrification in the North End, visualizing the history of segregation in Chinatown, or considering the housing stock (or lack thereof) in the South End, ninth graders spent this past semester getting up close and personal with the city of Boston, walking away with an enriched understanding of past and present.

Nineteen of the thirty-four members of the senior class have been recognized for their achievements in the 2024 National Merit Scholarship Program, either as Semifinalists or Commended students. Our ten Semifinalists are:

n Anto Catanzaro ’24

n Thomas Du ’24

n Mirai Duintjer Tebbens Nishioka ’24

n Henry Levenson ’24

n Aaron Li ’24

n Charlie Liebenberg ’24

n Will Narasimhan ’24

n Eve Shapiro ’24

n Jay Sweitzer-Shalit ’24

n Olivia Wang ’24

Representing less than one percent of graduating high school seniors across the U.S., only about 16,000 out of 1.3 million qualifying test-takers qualify as Semifinalists. Finalists will be announced in February of 2024, and National Merit Scholarship winners will be announced between April and July.

An additional nine Commonwealth seniors received notice of the National Merit Letter of Commendation. These are students whose PSAT scores put them in the top ~3% of test takers nationally:

n Ty Himmel ’24

n Eliza Lamster ’24

n Sienna Mathur ’24

n Matteo Sabatine ’24

n Sophia Seitz-Shewmon ’24

n Dava Sitkoff ’24

n Lizzy Wakefield ’24

n Paris Wu ’24

n Rayna Yu ’24

Two of our seniors had their work accepted by journals for publication. Athena Kuhelj Bugaric ’24, writing initially for Melissa Glenn Haber (’87)’s U.S. History class, tackled FDR’s infamous contestation with the Supreme Court and was published in the December issue of The Schola. In her essay, “FDR vs. the Supreme Court: The Battle for the Meaning of the American Constitution,” Athena veered from more traditional arguments about the outcome of this debate and contended that it resulted in “a more people-friendly form of ‘popular’ constitutionalism…that funda-

mentally transformed the meaning of the American Constitution.” Taking on a comparably complex topic in his U.S. History Since 1865 essay “Plan E in Cambridge: Town vs. Gown,” Jay Sweitzer-Shalit ’24 illustrated the political battles that ensued over the proposal of “Plan E” to institute proportional representation in Cambridge in the 1930s. Published in The Concord Review, Jay’s essay touched on class divides, university politics, and the underestimated importance of local government to offer a compelling case study of the journey of a controversial bill. Congratulations to both published scholars!

Camp Kingswood welcomed us with sunny skies as we returned to Piermont, New Hampshire, for a banner fall Hancock. From baking pies to battling in board games to putting on a talent show under the stars, our tradition-filled adventure saw us connecting with old friends and new.

Continuing a newer Hancock tradition, we were pleased to award nine members of our community for their submissions to our Hancock Photo Contest, in categories ranging from “Best Landscape” to “Best Spooky Vibes.” The winners of this year’s fall Hancock Photo Contest include:

n Grand Prize: Chloe Li ’27, “Burnt Gold on Blues” 1

n Best Landscape: Sarah Rahman ’27, “Mountain Reflection” 2

n Best Portrait: Olivia Wang ’24, “Metamorphosis” 3

n Best Adventure: Danny McDonnell ’26, “Kayak” 4

n Best Spooky Vibes: Mirabel Han ’26, “Misty Lake” 5

n Best Nature: Tien Phan ’24, “Monarch of Hancock” 6

n Best Night Sky: Ethan Wu ’26 7

n Best Boats: Eliza Lamster ’24, “Boat Buddies” 8

n Best Camp Kingswood: Mr. Singer

What’s the greenhouse-gas impact of a school that occupies two brownstones? Overall, impressively low, concluded the Environmental Club, led this year by Jay Sweitzer-Shalit ’24 ( meet him on page 25 ) Anya Ratanchandani ’25 , and Lillian Walsh ’25, after calculating Commonwealth’s carbon footprint for the first time.

As Jay put it, “Commonwealth only uses as much electricity as 2.5 homes because it is the size of 2.5 homes!” Sixty-five square feet per student means a culture of relentlessly optimized space, as anyone who’s spent time in the building knows, with classrooms and offices in constant use. “Only using gas and electricity emissions,” writes Jay, “the school produces around .13 metric tons of CO2 per student per year.” This figure represents both “scope 1” emissions, those produced directly by Commonwealth, and “scope 2,” those produced by the electricity we purchase. Jay calculates that “Commonwealth produces six times less CO2 from gas, electricity, and other ‘scope 1 and scope 2’ emissions per student than the Boston Public School system.”

The Environmental Club didn’t stop there but extended its analysis to scope 3, “emissions up and down the value chain,” which included everything from the paper in school printers to the flights students and staff take for the foreign-language exchanges and trips. That air travel accounts for 57% of the school’s carbon footprint; student commuting accounts for another 27%. During the 2022–2023 year, the club surveyed students and staff on how they get to school, wisely assuming that people don’t do it the same way every day, as reflected here:

On average, students commute to school via:

n Walking 5% of the time

n Bike 5% of the time

n Bus 7% of the time

n Light Rail 37% of the time

n Commuter Rail 19% of the time

n Car 27% of the time

On average, faculty and staff commute to school via:

n Walking 17% of the time

n Bike 17% of the time

n Bus 13% of the time

n Light Rail 23% of the time

n Commuter Rail 11% of the time

n Car 19% of the time

The commuting impact is about half a metric ton of CO2 per person per year, compared with 3.6 metric tons for a typical American driving a midsize car to and from work. Only 5% of workers commuted to work via public transportation in the U.S., per the 2019 Census. The school’s solid waste compares well, too, at about eighteen metric tons per year, on par with the annual municipal waste contributions of twenty-two average Americans.

Adam Hinterlang, Director of Facilities and Information Systems, said he was “very impressed and heartened” by the data the club gathered, which included “a lot of things I wasn’t factoring in.” In turn, Jay, who worked closely with Adam in putting the report together, says “Mr. Hinterlang has been improving the school a lot” in terms of energy efficiency.

Building managers like him, Adam says, have to think about cost alongside “other things I really care about. Being responsible citizens is part of the school’s mission.” Both come into play when it comes to Commonwealth’s electricity mix. The school was able

to lock in a low rate a few years ago by contracting to buy from a mix of renewable and nonrenewable sources “depending on where the supplier is delivering from.” In principle, the school could switch to 100% renewables, but at a higher cost and only after sifting through a lot of detail. “It’s not designed to be easy to switch,” says Jay. Nonetheless, he concluded that taking that step, along with replacing some gas-powered heating and water-heating units in the Cafegymatorium

once they are fully depreciated, could make the school carbon neutral (using scope 1 and 2) “within years.”

A Mass Save energy audit every three years, Adam says, also pays off because the state program will cover much of the cost of upgrades and the technology around efficiency changes constantly. After our most recent audit, for instance, “we had some power monitors added to our walk-in freezer and refrigerator units, which will cut down on their power usage by around 40%, since they are no longer running 24/7 but only running to maintain the target temperature.” He also learned about “legacy LED lighting”: older-generation LED bulbs need heat sinks, but the newest ones release so little heat that they don’t. So last spring Adam updated the fluorescent bulbs in the library.

A bigger lift will be new, double-paned windows for the classrooms on the third and fourth floors. “Climate control is one of the most challenging things I have to do,” says Adam, who looks forward to our already-efficient heat pumps becoming more so. Other hopes: air-quality monitors (“More oxygen, more alertness!”) and, looking further ahead, “If there was a way to have a solar array on the roof, I would love it.” t

Catherine Brewster is a twenty-three-year veteran of Commonwealth’s English department.

My bounty is as boundless as the sea, My love as deep; the more I give to thee The more I have, for both are infinite.

Juliet from Romeo and Juliet

“It’s a tricky, but moving, thing to consider love as an adolescent,” says Ellie Laabs ’17, reflecting on Commonwealth’s most recent fall play, Boundless as the Sea, and her own work, as the show drew its inspiration from her senior project, a compilation of scenes entitled One More Time With Feeling. Laabs attended the show’s premiere on November 17, 2023, watching a new generation of Commonwealth students explore love in all its incarnations through short works by Edward Albee, Julia Cho, Tennessee Williams, William Shakespeare (of course), and others.

“I felt truly moved and pulled back to that time when I put on a version of this show,” Ellie says. “The production had a palpable youthfulness that packed the punch all the more. It was so clear to me who had some experience with love and who was yearning for it—neither of these is better than the other, to me anyhow. The show was ripe with yearning and laughter and wonderful communal moments. I was delighted to see it—it truly did something for my soul.”

Using Ellie’s work as a starting point, Susan Thompson P’10 ’12, director of both the show and Commonwealth’s Theater program, added and edited scenes, with Romeo and Juliet as the evening’s anchor and love as a recurring theme. Susan titled the piece Boundless as the Sea after a speech given by that most iconic of love-struck adolescents, Juliet Capulet. “She understands that love isn’t a finite resource; in giving, you receive,” Susan notes.

The eighteen students involved (fourteen cast and four crew members) largely came from Commonwealth’s Advanced Acting classes, with several Acting 1 students providing “front of house” support. Three students, Paris Wu ’24, Will Papp ’26, and Mirabel Han ’26, took on more responsibility with longer scenes and after-school rehearsals.

“Without their extra hours, dedication, and hard work, this evening would not be possible,” Susan says.

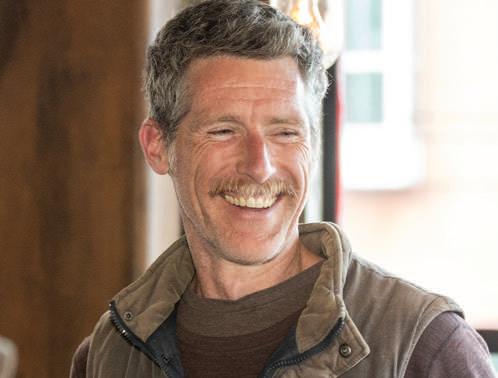

What does a Dean of Students do at Commonwealth, exactly? The title conjures a university administrator overseeing a network of offices devoted to student mental health services, extracurricular opportunities, family supports, social outlets, and more. In many ways, Josh Eagle’s work as our Dean of Students is no less extensive or nuanced.

With a team you’ll meet elsewhere in this article, Josh oversees “student life” at Commonwealth, which, we’ve been known to say, encompasses “everything outside the classroom.” But even that’s misleading, because attending to learning differences and academic challenges also falls to Dr. Eagle and the Student Life team. His assortment of responsibilities includes everything from chaperoning student dances to welcoming new families to weighing in on discipline cases. All are in service of supporting students and their ambitions at Commonwealth while giving them the skills they need to thrive beyond our walls.

Dr. Eagle and Head of School Jennifer Borman ’81 share a primary concern: students’ well being. Their work takes different forms but often intersects, like balancing Commonwealth’s academic rigor and supports to provide a healthy amount of intellectual “stretch” and combating lingering effects of the pandemic, as they discuss below.

Tell us more about what you do, Dr. Eagle.

Why do we have a Dean of Students? And what is the role of the Student Life team?

Josh Eagle: My job is about attending to people’s health and well-being—students, primarily, but also families, faculty, staff—and making sure all stakeholders are getting what they need in order to be successful here.

I’m a psychologist by training—I love talking to people—and a big part of my work is meeting with students, sometimes over a short term, sometimes a longer one, to help them problem-solve when they’re having issues in school or at home or with friends. Another piece of my job is stepping in when students have difficulties in the classroom, helping them figure out what exactly is getting in the way and working with their teachers and families to make sure they have the appropriate support.

The Student Life team is myself, two other clinical folks [school counselor Eben Lasker and intern Lilit Derkevorkian], Rebecca Jackman [Assistant Head of School], and Lisa Palmero [Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion]. We also added a consultative role this year: Audrey Budding [history teacher], who brings even more classroom context to our conversations.

I also work closely with several student clubs, like COMMunity, to develop—for lack of a better word—a

sense of community here! No two days are ever alike.

Jennifer Borman: One of the things people often ask me as an alum coming back to Commonwealth is how the school has changed. To me, this is the most striking set of changes: the web of support, both academic and emotional, is so much more built out than when I was a student. The exhilaration in the classroom is very similar, and advisors were wonderfully supportive then, but I feel like it was more “sink or swim” in my era. I just am so impressed and grateful to have so many adults looking at students’ experiences from multiple angles.

JE: I agree. I think we can expect a lot of kids and also offer them help if and when they need it. It’s not an either/or situation!

We do expect a lot of students—and they expect a lot from themselves! Commonwealth’s academic ethos is intellectually exhilarating, often life changing, and sometimes quite stressful. How do we help students mitigate that stress, set healthy goals (especially around college admissions), and grow as scholars and people?

JB: Our students are incredibly ambitious, and that is truly inspiring. The kids here hold themselves to high standards. They want to do a million clubs and extracurriculars. They’re in it full force. Usually that’s one of the thrilling things about being here, but sometimes that can lead to a lot of stress for them. Josh and I use the stretching metaphor: if you’re stretching your body, you want to go just to the point where it’s uncomfortable—but not so far you hurt yourself. The Student Life team helps

us find that balance with each student. That balance shifts from freshman to sophomore to junior and senior year, but I feel like we’re always titrating in that way, finding a healthy amount of stretch.

JE: Absolutely. We’ve worked really hard institutionally, over the course of many years, to dispel myths like “not sleeping a lot equates with being your hardest-working self.” We talk a lot in ninth grade about the importance of sleep and the corollaries of not getting enough of it. And it’s something we are mindful of, I think, as a community.

JB: The college stress is real, too. I teach seniors, and I call it the Baskin Robbins of stress: it comes in lots of different flavors as it unfolds throughout senior year. I think the messaging does get through, though, that they are going to get into wonderful colleges and that they are incredibly well positioned to thrive at those colleges. That said, and very much despite our messages and support, seniors often feel the stakes are very high. And that’s an ongoing challenge and an ongoing dialogue.

JE: We tell students: “Come here, invest in learning how to learn, and don’t worry about college until junior year.” That says a lot about how we value teaching students to be curious and to dig deeply into what they’re observing and learning. But there’s an inherent tension between being present for this high-school experience and being attuned to what’s to come after. I don’t think we’ve solved that, but it’s a work in progress.

JB: Beyond our own impressions and intuitions about how each student is doing, we administer this survey every other year, Challenge Success, to get a sense of how Commonwealth students

are engaging with their academic work, how much enjoyment they’re experiencing, how much stress they’re feeling and how that stress shows up in terms of sleep patterns or anxiety, [and] to what extent they are connecting with people in this school and feeling a sense of belonging. That data lets us look more holistically and objectively at what’s happening at Commonwealth than our own noticings.

One data point from the last survey that still sticks with me is that the students themselves report that the work they’re being asked to do is meaningful. Very rarely is it what they’d call “busy work.” This means, in large measure, our kids are really engaged, and our faculty do a wonderful job of engaging them. Another takeaway is that most students feel like they have an adult in the building they can connect with, particularly relative to other schools like ours. Again, our numbers aren’t perfect, but it was a much higher percentage of kids feeling like there was an adult who they could go to who they can trust, which, to me, is paramount.

What happens when a student stretches too far, pushing themselves in their classes and clubs? How do we intervene when they’re feeling overwhelmed?

JE: Depending on the nature of the issue, it can be as simple as a Student Life team member meeting once or twice to talk about what course load makes the most sense, or it can be longer conversations about what’s really going on, and that can sometimes take a little while to parse out. Even though students often know they’re overdoing it, they’re often reluctant to make changes.

Usually, but not always, when a student shows up at my door, I have some sort of idea of why they’re there. Their advisors often reach out to me first—and it’s usually after they’ve had multiple conversations with the student. That tells me advisors are well connected with what’s going on with their students. So by the time a student meets with me, they’re primed to entertain the prospect of change, which is helpful.

JB: There’s individual support, there’s problem solving, and there’s more programmatic thinking about the architecture we need to build so all kids can thrive. The Student Life team is really on the vanguard of asking, “All right, what do you need to understand as, say, an incoming ninth grader to be a successful student here?” It’s not just “how do we help a given child” but “how do we look at what we offer academically and programmatically to make sure all students are thriving?”

What do those programmatic student supports look like?

JE: You mentioned ninth graders, and the Ninth-Grade Seminar, specifically, really grew out of our recognition, during the pandemic, that we couldn’t assume a certain set of skills for new students in the way we could previously. So we worked to create a space to teach ninth graders, you know, What does it take to be successful here? What does it mean to be organized and on top of your work? What do those strategies actually look like? I think that course has made a real difference, and I hope it sticks around for many years.

Also on the programmatic side, there are community-building events—

JB: Where would we be without Overly Complicated Board Game Nights?!

JE: Ha! Yes, that is one thing I was thinking of. Especially in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, there was a real hunger from both students and families for more opportunities to connect outside of the classroom. Because our community lives all over Greater Boston, it’s harder for people to get together outside of school, so creating more spaces for them to just be together is really important. So we tried to create more school-based events for students to take part in as well as a student-led club to plan and orchestrate these activities. A couple years ago, it was often faculty and maybe one or two students planning these events; now students are eager to create these events for each other, which is wonderful to see.

You mentioned Lisa Palmero being on the Student Life team. Can you talk about how diversity, equity, and inclusion informs your work?

JE: I can’t say enough about Lisa, just the importance of her voice and presence and thoughtfulness. She has a talent for helping us solve complicated problems quickly, incisively. It’s not uncommon for our younger students to not necessarily know the boundaries of communication or understand the impact of their words and actions in a greater community. And when we run into situations like that, it’s essential to have Lisa’s perspective and expertise to help us think through the right educational response.

Lisa also helped Rebecca and me implement another important Student Life change over the pandemic: meeting one-on-one with all new families before their children even enter our building, even before orientation. We did this because we were finding that often,

our administrators’ first meetings with parents were centered around problems or challenges, and we wanted to find ways to be more proactive with those new to our community, for us to hear a little background and to better anticipate ways we might encourage and support our new students as well as to make more informed advisor choices. I think that’s made us a more welcoming place for new families—at least, that’s the feedback I’ve heard so far!

Even as the pandemic recedes, we know it exacerbated many existing teen mental-health issues. How are you thinking about these challenges and approaching them at Commonwealth?

JB: We spend a lot of time looking at public health data and the various analyses that try to show a causal link between things like social media use and rising rates of anxiety and depression [in teens]. Thankfully, on balance, our students show a lot of the behaviors that lead to resilience: they’re engaged with each other, they’re not cliquey, they have really constructive relationships with adults here and outside of Commonwealth. That said, we’re mindful of the fact that many of our students do experience mental health challenges, as many teenagers do. And that’s why it’s crucial to have such a strong team—and not just the Student Life team—with eyes on. It’s fundamental to what Commonwealth is, how intentionally small we are and how carefully every adult in the building attends to how kids are doing. “Oh, that child who was full of giggles a week ago now seems down and isn’t eating with their friends; what’s going on?” Or “A child who was thriving in a class is now way behind on work; what can we do?”

JE: The pandemic hit latency-age adolescents extremely hard. It’s a time when kids really need to be around each other to learn and to grow, and to know what it means to be in a community and have a friend. One of the impacts of being at home for eighteen months at that age is that kids missed out on a lot of important opportunities to learn what it means to be a teenager. So initially we saw—and I think still are seeing, to some degree—what happens when young people miss almost two years of socialization. That meant we had to adjust our expectations around what a “typical” ninth- or tenth-grade student looks like post-pandemic, and we needed to figure out what areas we needed to focus on encouraging and developing, like study and organizational skills, or social-emotional growth.

But I have to agree, Jennifer, that one of the benefits of being a very small community is that we can have a bigger impact on the lives and the evolution of the kids here in ways that help them grow into robust adults. We encourage face-to-face interaction. We encourage developing relationships amongst classmates and with teachers. And I think that mediates a lot of what they might encounter elsewhere in the world.

I also think the typical Commonwealth student is bought into what we do here, which is, really, learning how to be a learner. And by virtue of that, they’re approaching things like social media differently. Not to say there aren’t some kids who use social media too much or use it in the wrong way, but I really don’t think social media is a part of our culture in the same way it is as other schools—and I say this from my experience working with teenagers across the metro-Boston area. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be attentive.

One of our faculty working groups this year is focused on attention and distraction: How can we encourage sustained attention in and out of class? What are the barriers to that? And how can we create principles or a philosophy around healthy phone or technology usage we can follow as a community? That we’re engaging in thought and work around these issues, I think, speaks to who we are and how we take care of kids.

JB: The pandemic cast a long, long shadow and was—and sometimes is—an intrusive influence on our community. Still, I have to say, it feels very different this year to me. I think about our new cohort of ninth graders: they are so extroverted and enthusiastic and eager to connect. I don’t know if it’s a new phase of post-pandemic healing or if we just got really lucky. Again, this is only our second cohort of post-pandemic ninth graders!

JE: Yeah, I would agree. There’s a real champing at the bit to do all the things that come with being a Commonwealth student that feels pre-pandemic. Part of what keeps all of us going, I think, is that enthusiasm the new students bring. And I agree: their excitement is palpable.

I just want to say, I’m profoundly grateful for the commitment each of the various stakeholders brings to student life: I think our kids are wonderfully inspiring. I think our faculty are the best at what they do. And I think our families are very supportive of what we’re trying to do and willing to partner with us in finding precisely the right ways to support their kids. There’s alignment across the board, for sure, which is what makes Commonwealth such a special place. t

What can you do with a philosophy degree? Turns out, any number of things, as these five Commonwealth School alumni/ae have demonstrated with their careers in academia, digital publishing, banking, screenwriting, and more. And they agree that the real value of a philosophy degree is learning a way of being in the world with others, asking interesting and often tough questions about who we are and how we live.

During the financial crisis that began around 2008, many Americans felt as if their financial foundations were crumbling—for good reason. Ten years later, after the dust settled on what turned out to be a global recession, economists estimated that the U.S. GDP was approximately twelve percent below pre-crisis growth trends. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that the combination of decreased revenues and increased expenditures between 2008–2010 will ultimately cost every single American about $70,000 in lifetime income.

Stacie Haynes-Roberts ’89 had a unique vantage point in 2008 as a supervisory analyst at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, and she makes two key observations about that time: as bad as it was—with the loss of livelihoods and homes and imploding banking institutions—most of us will never know how fragile global economies really were. And the training Stacie received as a philosophy major at Haverford College was crucial to navigating the chaos.

“One of the things I learned, and I think a lot of us were figuring out, was just how difficult it was for any person, or even any segment of the disaggregated financial services supervisory community, to wrap their arms around the entirety of the U.S. financial system,” Stacie explains. “Nobody owns all of it. No single institution owns all of it. I remember one day there was a series of people making connections between one piece of the financial machine and another and another, and saying, ‘Oh my God, if this fails, then this could fail, and then this could fail.’ And people, like light bulbs, would go off at random times during the day, thinking of something else that we had to address. It was so incredibly stressful.”

Her background in philosophy, particularly the critical thinking at its core, was essential to understanding such cascading failure, Stacie maintains, and it has been apt preparation for working and succeeding within the world of banking. She began her career as a financial-planning specialist at Merrill Lynch “making rich people richer”—not what she wanted to be doing long term. For the next thirteen years, she worked as an examiner and analyst for the Federal

Reserve Bank in New York, then Boston, and, finally, San Francisco. Stacie is now a senior manager at PricewaterhouseCoopers in Washington, D.C., where she and her teams oversee regulatory compliance engagements for large financial institutions such as banks, automotive finance companies, mortgage lenders, money service businesses, credit unions, and consumer products manufacturers.

“I didn’t realize just how desperate we are as a species for critical thinking and just how absent it is,” Stacie says, “and that need has only increased while the presence of that kind of thinking has only diminished. So, my appreciation for that kind of [philosophy] training has only grown since Haverford. And I don’t care whether it’s my professional life or my personal life. It is essential to both.

“How do you get people to work with you? You’re there for their benefit, but they may not see it that way. A lot of that is in relationship building. And how do you do that effectively? You might not think philosophy would have anything to do with it, but the Socratic Method is key.”

Hers is not at all a mainstream perspective on the worth of a humanities degree, let alone a degree in philosophy. But Stacie explains that the foundation of her philosophy training at Haverford College was the mentorship of Professor Lucius Outlaw, Jr. Even before she declared a major, Dr. Outlaw, along with a few other African American professors, held a gathering welcoming Black freshmen to let them know that they were invested in their success at the college. Stacie has carried that ethic into her own work. Dr. Outlaw was Stacie’s thesis advisor and, after the death of her mother, a surrogate parent.

The two remain close, and she holds dear what he taught her: rigor and precision in thought and deed, the importance of embracing Black community, and most crucially, as she succeeds, to bring others along with her.

“Professionally,” she says, “I’ve decided that, as a Black woman with access to people who are not Black, one of the things that I can do is work on behalf of other Black folks or the next Latina or the next Asian person. There’s a way I can see racism. I can see misogyny. I can see homophobia. There’s a way in which I have been trained to see those things and to create space for the people who are othered.”

“How can you tell that you’re not dreaming? How can you tell that you’re not spending your entire life in a computer simulation?” Jessica Moss ’91, professor of philosophy at New York University, often hears these questions from first-time philosophy students. “I love it when people find out that this thing they’ve been doing all along—asking questions their parents have told them to stop asking because they don’t have answers—is a real thing that you can study. And it’s a thing that people have been doing for thousands of years.”

Jessica studied philosophy for the first time as a sophomore at Commonwealth in Mr. Kaplan’s course. The class read Plato’s Meno, a dialogue between Socrates and his student on the nature of virtue. It was one of several great reads that semester, and she describes the dialogue as having been intellectually intense but nonetheless satisfying. “I felt like I could make connections and understand what was going on, and I felt excited by the ideas,” she recalls. “[Meno] had some of what I liked about reading literature, but it also had these puzzles that would get under my skin, and I was hooked. Ever since then, I’ve loved

Stacie Haynes-Roberts ’89

Plato.” The experience showed Jessica why someone might want to study a subject that is thought by many to be esoteric but is mostly about exploring the perennial questions we ask ourselves.

Now a specialist in ancient philosophy, Jessica’s research looks at epistemology, ethics, and psychology. All roads in the Western tradition lead back to the ancients, but they still have much to tell us about the way we live now, particularly as it concerns the need for critical thinking and the ability to distinguish between knowledge and belief. Think so-called fake-news media or even the proliferation of AI—anything that relies on how something appears to us. “A lot of my work has focused on this idea, that runs very strongly in ancient philosophy, that appearances are very powerful,” Jessica explains. “But you have to be careful with them. A lot of our decisions, but also our emotions and desires, are influenced by how things appear to us, where that can include things appearing good or bad. For example, tasty treats appear good and hard work appears bad. And I think both Plato and Aristotle were really perceptive psychologists who thought that there is actually a whole part of our psyche that’s taken in by appearances without being able to question them at all, and that part is the source of our emotions and our desires. But we also have this other part that can reason and reflect and criticize. And that’s the part that they think we should trust and need to strengthen. I’ve been interested in how that gets picked up in modern psychology.” Her work, she says, has recently taken a turn from explaining or interpreting what Plato and Aristotle meant toward relating their ideas to contemporary philosophy “and thinking about analogies between knowing a person and knowing a fact, and believing a person or believing a fact or claim.”

The study of philosophy has many rewards, and Jessica wishes everyone could take the time to ponder its questions. She does outreach work in high schools and a local detention center and often encounters the preconception among students that philosophy won’t be for them. While that may be true for some people, for many others, something clicks. “If you can just get people to see what the question is, then a lot of times they think, ‘Oh yeah, I think about that all the time,’ or ‘I find this fascinating,’ or ‘This is getting under my skin.’”

Asking questions—some of which don’t have evident answers or evident means to achieve answers—is an activity that human minds do naturally, Jessica says. “The questions can’t be answered by science or history or even observation. You just find out by thinking. I feel really lucky to have been able to turn it into a career.”

This is the one about the philosophy student who becomes a successful television comedy writer…

As a writer/producer, Fred Barron ’65 helped launch Seinfeld, The Larry Sanders Show, Caroline in the City, and Dave’s World, as well as the HBO miniseries Sessions with Billy Crystal. Following a bout with cancer, Fred relocated to the U.K. in 2000, where he created the BBC One series My Family, bringing the American writer’s table to British sitcom production—which, even today, rarely airs multiwriter television shows. The series ran for eleven seasons and was considered a favorite sitcom of the early 2000s.

But there’s before this and after this. Long before his career in television, Fred attended the University of Wisconsin and majored in philosophy because, as he tells it, “it was great learning how to argue and seeing things from different points of view.” He went on to pursue graduate study in philosophy, until his girlfriend Jeanne, now his wife of more than fifty years, reminded him who he really was. “She said, ‘Don’t be crazy. You’re funny. You’re not a professor: You’re a writer.’ And that was the first time someone—other than myself— called me a writer. Who was I to question? I dropped out, Jeanne transferred to BU, and we moved back to Boston.” Fred worked as a freelance journalist for publications like the now-defunct Boston alternative weekly The Phoenix, which served as inspiration for his first film script, Between the Lines

After interviewing director Joan Micklin Silver at the Cannes Film Festival, Fred met her again at the Boston premiere of her film Hester Street. “Joan had liked the article I’d written from Cannes and invited me to dinner,” Fred recalls. “Since Joan was the only person I knew who had actually made a successful low-budget film, I asked if she would read my screenplay, Between the Lines. A week later, she called to say she wanted to make it as her next film. Just like that.

“I always wanted to be a writer, since I was six or even earlier, so that was never an issue. But what kind of writing? What would it be? How would I express myself?” Fred explains. “My writer’s voice hadn’t developed. I didn’t have a good descriptive sense. But dialogue? The back and forth of conversation? Maybe that’s the reason I was drawn to philosophy: I loved arguing things from different sides, and I ended up using that in the comedy. The basis for all my comedy was that you mess with people’s expectations.”

The comedy-drama Between the Lines, starring Jeff Goldblum, John Heard, and Lindsay Crouse, was released in 1977. The film received critical praise and is now considered an indie classic. It also put Fred on the radar of MTM Enterprises. “It all happened very quickly,” he says. “I was out in L.A. doing publicity for Between the Lines when James L. Brooks, who created The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and his head writer, Treva Silverman, hunted me down and for whatever reason took me under their wings.”

For the next thirty years, Fred wrote for and created some of the most memorable sitcoms in American television. His last project before retiring allowed him to cater to his love of “outsider art.” He wrote and co-produced the feature documentary Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts, about a former enslaved person who started drawing in his eighties, which had its world premiere at the Smithsonian in 2020 in conjunction with the first retrospective of Traylor’s art.

When asked how he reflects on his television work, however, his answer is both surprising and self-aware. “The world since Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, is so different, as far as what white male writers sitting in a room thought was funny. Yes, it was funny the way Copernicus said that the planets and the entire universe go around the sun; he was wrong, but he got part of it right. I think the shows were funny. They were wonderful. But they weren’t sufficient. There were so many other voices out there, newer voices. And I look at the assumptions we made for jokes, and it just feels a little embarrassing. We’re better than that now. We’ve improved.”

What if our current assumptions about how to protect the environment are incomplete or just wrong? What does it even mean to hold space for new thinking—on climate change, for example, or species conservation—as the human impact on the planet only intensifies? Alexander Lee ’06, associate professor of philosophy at Alaska Pacific University (APU), has built a career grappling with these questions and more. A specialist in environmental philosophy with a focus on applied ethics, Alex combines his academic background in philosophy and earth sciences with his love for the outdoors not only in order to think but to do

Philosophy isn’t just an intellectual exercise, says Alex, who points out that most philosophers are deeply invested in whether the questions they examine might be applicable to real-world problems. Environmental philosophy, in particular, is a branch of the field in which solving real problems is precisely the point. “It really matters if we can shape a better understanding of what it means to have a true belief, what it means to understand wrongdoing or harm to others. These questions have huge implications for how we live our lives,” Alex explains. “Environmental ethics is a way to take philosophical theory but try to use it in the service of an applied field. And for me, I went down that route really because I became passionate about both philosophy and environmental problems.”

Alex’s passion for philosophy began at Commonwealth, where he took two ethics courses with then-Headmaster Bill Wharton, and continued at Dartmouth College. He didn’t think he would ultimately major in philosophy, but while he was cultivating his interest in the earth sciences, he filled all of his electives with philosophy courses—resulting, accidentally, in a double major. At that point, he knew he wanted to pursue environmental science but he also wanted to learn more about the philosophy of science and ethics. Graduate school at University of Colorado, Boulder, enabled him to combine these interests and learn to apply philosophical thinking to environmental issues.

“Let’s look at something like climate change or biodiversity loss or conservation challenges or resource use,” Alex says. “How do we manage these problems in the most ethical way possible? As an environmental ethicist, I have a foot in a very theoretical world: ethics. But I also have a foot in a world where we look at environmental policies, management practices, and management decisions. What can philosophy tell us about these policies and practices, about our behaviors? And how might ethics guide us to build better policies, better behaviors, or help us evaluate different choices we might face when trying to solve a problem?”

His current areas of research circle a number of significant concerns, but one in particular will help shape the book he is writing: the ways in which our environmental consciousness from the twentieth century, which focused on resolving discrete problems—a “find a fire, put it out” approach—might be inadequate for addressing twentyfirst-century systems-level problems.

Alex teaches a number of courses at APU, including Environmental Philosophy, The Philosophy of Science and Technology, Environmental Policy, and Critical Thinking and Ethics—a required general education course that helps develop a skill set every student, regardless of major, would find valuable. “I fully believe that, as a society, we disagree on less than we often think we do,” he explains. “And it’s because we’re using different language, and we’re having different conversations, and

we’re [basing our opinions] on different assumptions. If we can break those down and understand that, we can find a lot more common ground and make a lot more progress, right?”

Having a background in philosophy can provide the clarity of thought and purpose needed to navigate periods of transition—and the rise of digital publishing is no exception. The Internet seemed to signal the imminent decline of print, a zero-sum game in which technology ultimately bested printed scholarship. But to Jesse P. Karlsberg ’99, senior digital scholarship strategist at Emory University, technology offers thrilling opportunities, helping us make research more accessible while also documenting and preserving cultures. In Jesse’s case, American vernacular music books and performance.

“Digital scholarship is the idea that technology impacts research, teaching, and publishing in academia in all kinds of ways,” Jesse says, “and that universities need people thinking critically about that and also pursuing research and innovation in those areas.

“My role is to understand this landscape and how it’s changing. Publishing on the Web and in other digital environments presents opportunities to do things that printed books or printed journals cannot do. It pushes conversations beyond the book—to sharing research data, curating thematic collections, or bringing new light to scholarly editions. It gets people thinking about publishing their data and digitally presenting the sources on which they base their arguments.”

Jesse is the product owner of Readux, developed at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship. Readux is an open-access, open-source, Web-based platform that enables scholars, students, and independent researchers to teach, learn from, and engage with digitized historical books. As a graduate student in American Studies at Emory’s Institute for the Liberal Arts, Jesse was studying shape-note singing, a form of musical notation and sacred vocal music originating in the nineteenth century. He wanted to publish an edition of a historical songbook digitally but realized that tools for digital publishing had a number of

“ I didn’t realize just how desperate we are as a species for critical thinking and just how absent it is. And that need has only increased while the presence of that kind of thinking has only diminished... And I don’t care whether it’s my professional life or my personal life. It is essential to both.”

Stacie Haynes-Roberts ’89

inherent deficits that would need to be overcome, deficits that Readux was designed to address.

At the time, digitally published books tended to privilege text over image, so they were often not captured in totality. “I was really interested in developing software that would enable us to harness the affordances that digital environments ought to offer for representing historical texts—centering the image, but not losing what you get by presenting the text and perhaps even the musical information.” Another issue was that, despite the voluminous number of digitized books being produced, “people were starting to realize that digitization didn’t solve any kind of access problem on its own.” Most digital resources were sitting on servers. Even as they were available via library search interfaces, siloed within individual institutions, very few people knew these resources even existed.

With Readux, researchers can annotate digitized books and create and publish digital editions and inter-institutional thematic research collections, as is the case with Jesse’s Sounding Spirit Digital Library project. Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, Sounding Spirit encourages collaborative engagement with southern American sacred songbooks through the publication of scholarly editions and thematic research and teaching collections of digitized works.

A composer and internationally recognized Sacred Harp singer, Jesse is passionate about the preservation of American sacred music cultures. He has sung since his time in Commonwealth’s Chorale and explains that there is something both transporting and grounding about singing with others “in the same space, facing them, vibrating the air, feeling it in our bodies. It’s when I most experience my personhood and my humanity, being a part of society.” t

Lillien Waller is a poet, essayist, and editor. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets, and she is editor of the anthology American Ghost: Poets on Life after Industry (Stockport Flats). Lillien is a Cave Canem Fellow and a Kresge Artist Fellow in the Literary Arts. She lives in Detroit.

“If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch,” Carl Sagan observed, “you must first invent the universe.’” That sounds like a job for video-game designer Lydia Symchych ’14 To make anything in Lydia’s current project, Tablecraft, players start at life’s very beginnings, gathering atomic elements and engineering reactions until they’ve produced items like plants, shells, and lightbulbs.

Lydia, along with her teammates at virtual reality (VR) gaming studio Not Suspicious, is building every detail of Tablecraft’s immersive universe—and using it to show how scientific principles work within our own world. “We’re trying to teach STEM concepts in a way that is really, really fun, in the vein of a cooking game,” she says. And as a longtime gamer herself with experience in teaching and exhibit design, Lydia is up for the challenge.

The plot of Tablecraft begins not with chemistry but a court summons: You are a mad scientist given a community service requirement after your latest schemes disturb public order; rubber chickens and gravitational anomalies are both involved. (Moreover, perhaps you are a kindred spirit of Commonwealth’s Evil Genius Club, aka student purveyors of puzzle hunts.) To fulfill your community service requirement, you must venture to laboratories on various planets and provide “craftable” objects to their dwellers. The catch: different resources are available on each planet, and you’ll need to puzzle out how to transform them into what your clients need on specialized machines. That could mean converting “element cubes” (Tablecraft building blocks) to organic molecules or forming rocks and other minerals. If you can grapple with each laboratory’s anomalies, satisfy the locals, and beat the clock, you’ll unlock new levels—and earn back the machine-operation licenses that were revoked under your sentencing.

Lydia works to map out how players will move through Tablecraft’s levels, developing not only the story arc but the core game mechanics, the taxonomy and classification systems for different objects (like element cubes and craftables), and models for her ideas. She counts the zany hijinks from the television shows of her childhood, like Wallace and Gromit and Jimmy Neutron, among her narrative inspirations—“slapstick but not dangerous.” And real-life researchers are taking note: the team has netted multiple grants for their work from the National Science Foundation.

Lydia and her fellow tinkerers at Not Suspicious take after their game’s protagonist, too; the company website’s tongue-in-cheek newsfeed describes the team as “infiltrators” who secure their funding through “heists,” pitching titles under the slogan “Learning in Disguise.” It’s a neat analogue for the educational-gaming niche (also sometimes referred to as “positive-impact gaming”), which can fly beneath the radar of mass-consumed culture. Blockbusters like Call of Duty or The Sims produced by the industry’s major “triple-A” studios still dominate popular perceptions of what games are and can do.

However, with plans to market Tablecraft to any interested player— not just students within middle and high schools—Not Suspicious aims not only to infiltrate but to innovate. “We want it to be able to be used in schools, but it is definitely meant more to be a field trip—something that does relate to what they’ve been working on but is a break,” Lydia says. “Anyone who really likes science and wants a chance to learn something new: that’s really where our target audience is.” Aspiring Tablecraft scientists don’t even need to wait for the game’s full release: a server organized by the studio on the messaging website Discord is full of playtesters, experimenting together on prototype levels.

The primary focus of Tablecraft is chemistry, but as the game’s universe expands, Lydia and her teammates are incorporating material from multiple subjects to give players more exposure to interconnected topics under the STEM umbrella. Take one update Lydia is excited to add to a future Tablecraft iteration: the ability to throw rocks of varying masses. “That’s a gentle nod to density, which is something that you cover very early on in chemistry; you also cover it earlier in math in algebra,” Lydia explains. “It interacts with basic Newtonian physics— things that are heavier will travel farther and longer.” The approach may sound familiar to anyone who’s experienced Commonwealth’s curriculum, where the sequencing of science courses aligns with when concepts are presented in math.

In her time at Commonwealth, Lydia didn’t self-categorize as a STEM nerd: “I think of myself as a jack-of-all-trades.” That included dance, creative writing, biology, history, and, among her ample gaming experience, playing Minecraft, which may have indirectly contributed to her sharp attention to Tablecraft’s scientific accuracy. (“I was genuinely sad to learn that obsidian in real life is not that hard, because in Minecraft, you need diamonds to break obsidian,” she recalls.) She explored gaming not only through play but production; her senior project with Phoenix Online Studios culminated in a design-intern credit on the twentieth-anniversary remake of adventure title Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Father

“I had the space at Commonwealth to do a lot of different things and not have to be the best at all of them,” Lydia reflects. “It wasn’t like other high schools where it’s like, ‘This is a math and science school first. This is a classics school. This is a sports school.’ Commonwealth had enough of a broad, liberal-arts palette that I could go and explore and get decent experience with any subject, which was important for me because I didn’t know what I was going to be or do or what I was good at.”

Lydia kept following the liberal arts to Carleton College in Minnesota, where a stint as a student dance instructor brought her professional interests into focus during senior year: “I like to teach people. I like to learn new things. I like to work with people of all ages.” She wasn’t keen on working in an art museum or traditional classroom, but she found two internships that fit the bill, first with the Rice County Historical Society, then at the Montshire Museum of Science, where she focused specifically on exhibition design.

But the COVID-19 pandemic hit, disrupting cultural institutions, and she needed a new plan. “I was still interested in video games very much,” Lydia says, so when a positive-impact game company was seeking a designer, she gave it her best shot: “I thought, ‘I need to make a portfolio anyway and brush up my résumé. I might as well apply. I’m not gonna get it because I have no experience.’ And then I got the job somehow.”

While this entry into game production may have felt like chance in the moment, it now it feels like a “natural extension” of her museum work, Lydia says. Learning to incorporate feedback from scholars and educators into a cohesive exhibit design prepared her to do the same with the knowledge, like chemistry in Tablecraft, underpinning her virtual worlds. “I did really like to work with people who were experts in their fields and hear about it and think, ‘Oh man, that’s so cool,’ and then figure out how I could integrate as much of that as possible into an exhibit either explicitly or subtly,” she says.

An expanding interest in narrative storytelling at museums meshes with Lydia’s current role at Not Suspicious, too. “Within the last couple of decades, museum exhibits have shifted from a more collections-based mentality to an interpretation-based one,” she notes. “You can see that shift, I think, particularly in older university museums, which have gone

from walls and walls of dead stuff in jars and collections…to curation with labels that establish the pattern, the story, the argument they’re trying to tell.” With more exhibitions inviting visitors to engage in those stories by virtual means, like scannable QR codes and augmented reality information pop-ups, a game like Tablecraft may not be out of place at a future museum either.

Like museums, digital games have evolved, too. Lydia came of age during what she hails as the “golden age of educational video games” in the 1990s, when a boom in personal computers opened new doors for studios. Kids solved puzzles for the charming blue titular creatures of the Zoombinis games or traveled to locales like Mystery Mountain and Haunted Island in the JumpStart franchise—all the while picking up basics of math, science, and reading.

~A game she wishes more people knew about: “Adventures With Anxiety is an anxiety-disorder simulator where you play as someone’s anxiety. You are in charge of keeping your human safe. You can see the flavors of anxiety that can occur in someone, which is interesting—‘you are in danger’ versus ‘you are a terrible person’....and you can pick thoughts that lean one way or the other and see how that plays out.”

~A game with gorgeous graphics: “Child of Light is done in all watercolor and colored pencil (pictured above). Also, Ōkami, which is in Japanese brushwork style.”

~A game with a compelling story: “Chicory is about imposter syndrome and creative burnout and the struggles of being someone who is artistic. It’s very wholesome and nice and has a great soundtrack.”

~What she’s playing now: “A lot of Slay the Spire I also just started playing Skyrim for the first time this year, which is bonkers considering it’s over a decade old.”

~If you don’t know what to play next: “I would like to make a plug for watching people on the Internet play games. You don’t necessarily have time to play every game, and also you will not enjoy every game. It is still valid to watch someone else play and experience it that way.”

In high school, Lydia’s interest grew through “Let’s Plays,” vlogs where a gamer films their play for viewers, with running commentary and jokes that recall the on-the-fly insights of a DJ or sports broadcaster. “I was exposed to so many types of games, which then built up my design vocabulary,” she says. By watching another person take the controls, she “could notice a lot more of the details and the ways that they were doing things.” The Let’s Players that Lydia followed helped usher in today’s savvy streamers, who can broadcast their gameplay live to an audience and get instantaneous reactions through online platforms like Twitch.

Now, educational game developers are on the cusp of another transformation with the rise of VR, but Lydia cautions those who would view the technology as a quick-fix solution for educational needs—or sloppy storytelling. “You can’t just throw something onto an iPad and have it be great. You have to have an intentionality with what you’re going to put onto a VR headset, onto an iPad, onto the computer as a game and as technology for teaching something, whether it’s for kids or older adults,” she urges. “If it tries to do everything, it will do nothing.”

When working on Tablecraft, Lydia takes a deliberate approach, considering what players will gain and learn by adding different sensory details. Designing requires making tough calls about which game objects to keep basic and which would benefit from multiple custom options. “Do you make plain feathers or do you make down feathers versus flight feathers versus another feather? Is it important enough of a difference to have so many types of fish scales?” The tradeoffs of time or money are too high to create some items, but for others, it’s those realistic details that help players absorb information. With regard to future rock-throwing, Tablecraft doesn’t explicitly say that changes in mass affect motion, Lydia says; rather, by hurling different materials within the game, “you will have intuitively learned something in the same way that a baby does.” (Plus, “throwing things is fun in VR.”)

The goal is for players, particularly young students, to learn by fully engaging with Tablecraft’s fantastical planets; that way, concepts will be vivid in their memory whenever they next encounter advanced STEM material. “Maybe a middle schooler plays the game,” Lydia says, “and they’re putting element cubes into a template to make cellulose. Years later, if they’re looking at the skeletal structure of a molecule of cellulose, they’ll think, ‘Wait a second. That looks familiar.’” Suddenly, absorbing what could’ve been strange abstractions feels as easy as, well, pie. t

Claire Jeantheau served as Commonwealth’s Communications Coordinator before becoming the Marketing Manager for the American Exchange Project.

In the fall of 2021, the members of Commonwealth’s junior class, tasked with electing two student representatives, were decisive about how they wanted to do it: ranked-choice voting, aka proportional representation. Rather than the more usual first-pastthe-post system for determining winners, each student ranked each of the four candidates from 1 to 4. As one of the class advisors figuring out how to turn the pile of ballots into two winners, I had only a vague sense of what explained their strong preference. In hindsight, I’m pretty sure it was the arrival of Jay Sweitzer-Shalit ’24 the year before.

As he puts it, Jay is “interested in civics and government through a mathematical lens.” If that suggests armchair detachment from actual politics, it shouldn’t. Since middle school, Jay has been accumulating expertise on how Brookline, his hometown, is governed; he’s not only thought about how the town can move the needle on equity and climate change but also proposed legislation, whipped votes, and logged hours of Zoom and in-person meetings. He expresses it as another mathematical dilemma: “The time I spend on Brookline politics and the time I spend on school should not be mutually compatible.” Somehow, they are.

When Jay was a junior, Brookline’s Select Board appointed him to the Ranked Choice Voting Study Committee, charged with recommending how best to implement proportional representation if Brookline chooses to do so. (See sidebar.)

Town governance in New England isn’t so different from the complex board games Jay and many Commonwealth students enjoy: both involve accounting for multiple stakeholders’ strategies, managing many moving pieces, and acquiring a fair amount of specialized vocabulary. Take, for example, this paragraph from Jay’s committee’s report about the ranked-choice voting legislation under consideration:

After evaluation of several potential RCV options, the Committee selected a Proportional RCV method. Standard forms of Proportional RCV are currently in use in Cambridge and have been selected by Amherst, Concord, and Northampton. Other options reviewed were Sequential RCV and Bottom-Up RCV, which were noted by the RCV Committee to less fairly represent voter-base intentions. The Committee reviewed commonplace methods of transferring Proportional RCV votes from eliminated candidates to continuing candidates, including random assignment, which is simple but can skew outcomes, and fractional-transfer, which requires a spreadsheet to calculate results but produces outcomes which are transparent and traceable.

It’s not hard to see why Jay, when asked what he wishes people understood better about local government, replies, “I wish they understood it at all.” At the same time, the committee’s report goes on, “Survey evidence indicates that voters in municipalities actually using RCV understand how it works.” As the committee member

who gathered that evidence, Jay heard from people in several municipalities that “the longer people use RCV, the better they understand it.” Thinking back to Massachusetts Ballot Question 2 on rankedchoice voting, which failed in 2020, he noted that “it’s very easy for opponents to make the math sound more confusing than it already is. And whether they intended to or not, the Yes campaign focused on how it works rather than what it seems to do: increase representation by underrepresented groups and reduce negative campaigning. Candidates don’t have to worry about playing the spoiler to like-minded candidates.”

The 255 elected members of Town Meeting, in Jay’s words, “vote on everything that matters to Brookline, an unwieldy and also very democratic system.” The legislation they consider takes the form of warrant articles. With the committee’s work done and a warrant article on ranked-choice voting before Town Meeting last May, Jay’s role shifted to that of lead whip, soliciting votes. That meant reaching out to about half the Town Meeting members himself, as a compromise was forged under which RCV would be used only for townwide races such as the five-member Select Board, not the election of Town Meeting members. Without that work, said Jay, “the article would not have passed.” The final vote was 120 in favor, 100 opposed, with 7 abstentions.

This is the next term that the local-politics neophyte needs to absorb. Home rule explains why ranked-choice voting is not yet in place in Brookline. Town Meeting’s “yes” vote was actually a vote to petition Massachusetts’ General Court—the state house—for home rule on elections, which the state controls according to its constitution. Brookline voters, in a town referendum, will decide whether to implement RCV in townwide races if the petition is granted.

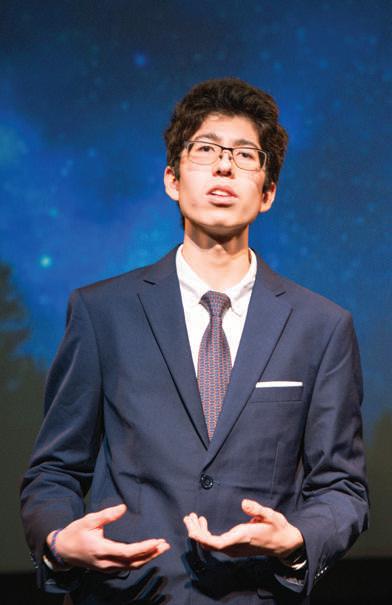

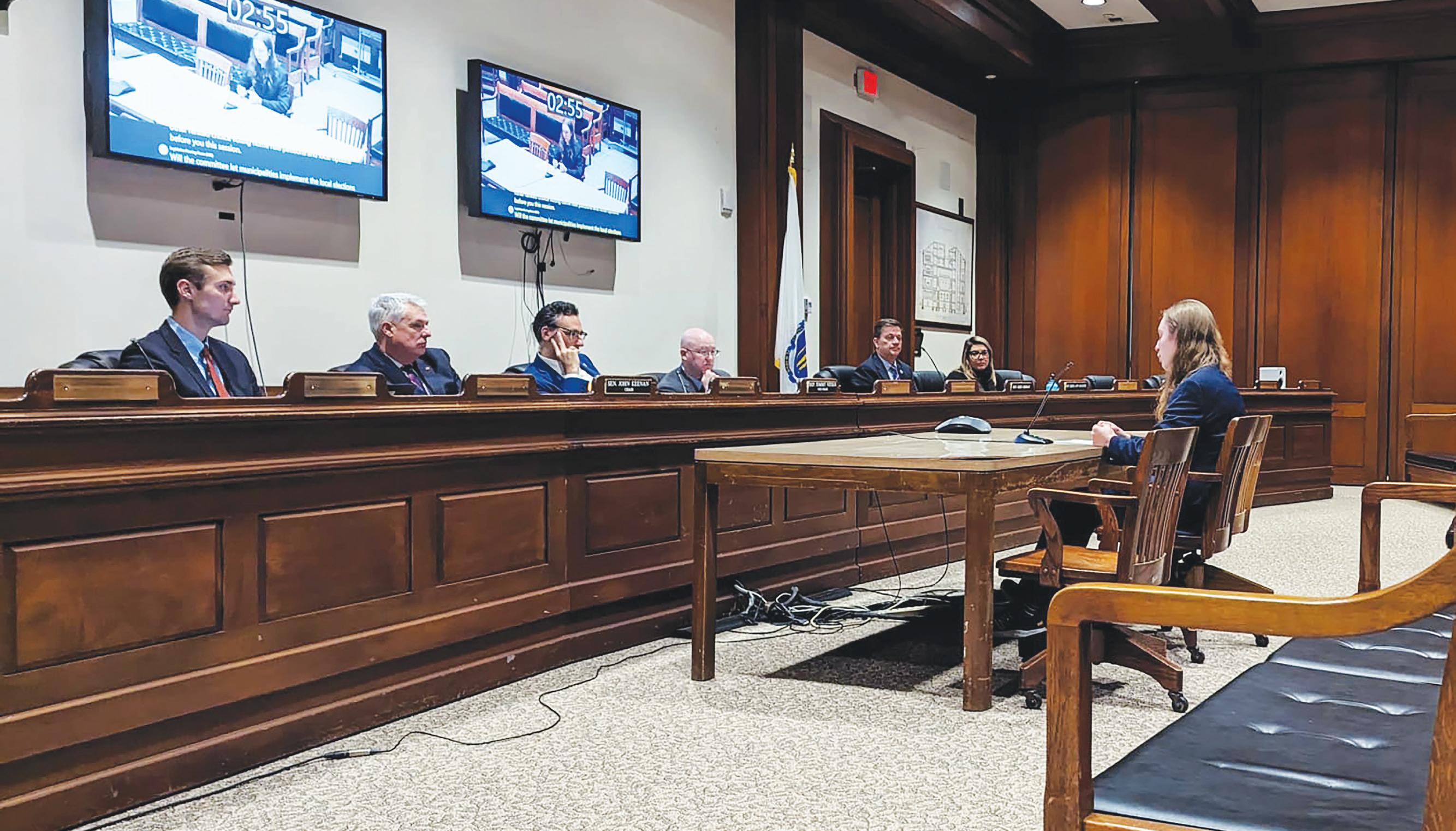

Jay speaking at a State House hearing of the Joint Committee on Election Laws to advocate for Home Rule Petition H.4112, which would grant Brookline a referendum on the implementation of ranked-choice voting in local elections

Jay speaking at a State House hearing of the Joint Committee on Election Laws to advocate for Home Rule Petition H.4112, which would grant Brookline a referendum on the implementation of ranked-choice voting in local elections

It probably won’t be “this time,” according to Jay, who has seen this before. “Most home-rule petitions don’t go anywhere, except for the ones for things like ‘Gary in the fire department doesn’t want to retire at 60, so please allow him to work another ten years,’” he said. But he’s also seen what can happen when enough home-rule petitions on the same matter accumulate.

One example concerns voting rights for 16- and 17-year-olds and for green-card holders (legal permanent residents who are not U.S. citizens; an effort to allow green-card holders to vote in New York City elections is making its way through the courts now). Brookline petitioned for home rule to allow green-card holders to vote in town elections in 2010 and again after a warrant article Jay proposed that passed “after a very difficult political fight” in the spring of 2022. Brookline’s history with 16- and 17-year-olds voting (again only in town elections) is similar, though not identical: a petition for home rule passed in 2019 but not in 2022. “There is now a statewide push for both,” Jay notes.

Jay’s initiation into Brookline politics, when he was in eighth grade, was a warrant article petitioning for home rule in prohibiting fossil-fuel infrastructure in new construction. In 2022, after denying multiple such petitions—from Brookline and other towns—the state created the Fossil Fuel Free Demonstration Project in ten cities and towns, including Cambridge, Newton, Arlington, and Brookline.

The fight to slow climate change is Jay’s leading example of what he has expressed mathematically as the Collective Action Problem: “If the whole world wants something, but each individual person is motivated by self-interest to do a different thing, then the thing that would be better for everyone doesn’t happen.” Brookline is already a dense, low-carbon community relative to its American peers, but banning new fossil-fuel infrastructure, he said, is one of the few meaningful steps the town can take. “It will have a much bigger impact” if it ends up allowing the town to say to the whole state, or Massachusetts to other states, “This is something that works; copy our language and do it.”