2

Performing the Tuskegee New Negro

The Racial and Gendered Aesthetics of the Repurposed Plantation

No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem,” declared Booker T. Washington in the Atlanta Exposition Address of 1895.1 This chapter lingers in the space between the tilled field and the poem, the line of crops and the line of verse, to take seriously Washington’s equation of agricultural labor and aesthetics. If the repurposed plantation was a material, geographic, and ecological strategy for regenerating Tuskegee’s degraded lands and African Americans’ relationship to agriculture in slavery’s aftermath, as argued in chapter 1, it was also an explicitly aesthetic project that aimed to redress racial-sexual representation in media and popular culture. Because Washington fashioned himself as too serious and driven to enjoy fiction and other amusements, his aesthetic contributions and those of Tuskegee’s faculty and students have often been overlooked. Although Tuskegee has often been regarded as a servant-training school that prepared Black students to accommodate themselves to the South’s racist and segregated labor economy, it was, on the contrary, a modern educational institution with defined aesthetic conventions and ideals.

As an international orator at a time when “public speaking was the chief form of public entertainment,” Washington was a leading Black performer, to say nothing of Up from Slavery’s tremendous influence on American letters.2 At Tuskegee, he exhibited a “devotion to design detail” that ranged from initiating and judging students’ flower-arranging competitions in the dining hall to collaborating with faculty about the design, layout, and style of the campus grounds and architecture.3 Tuskegee’s faculty, staff, and students understood themselves as southern New Negroes: modern, educated subjects who gave special care to dress and style and who comported themselves in accordance with bourgeois

conceptions of proper racial and gender conduct. They participated in numerous literary societies, and the Tuskegee Student newspaper regularly reprinted poetry and ran columns such as “Book and Magazine Table” and “About Books and Authors.” 4 In 1905, some of the most popular books in Tuskegee’s Carnegie Library included John Milton’s Paradise Lost, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield, and Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. Students were especially fond of Charles Chesnutt’s novels The Marrow of Tradition and The House Behind the Cedars for their ability to capture the specificity of students’ lived experiences and cultural traditions as Black southerners, and Tuskegee’s young women found great historical value in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Apparently, students were so fond of reading that they sometimes forgot to return their books to the library, and the school had to keep multiple copies of the most popular texts on hand.5 Washington and Tuskegee’s faculty held strong convictions about the school’s music performance culture, especially the singing and preservation of “plantation melodies,” and embraced photography and film to document and project the school’s successes to the world. As early as 1900, faculty and students even performed canonical theatrical works, such as William Shakespeare’s Othello

In rereading Tuskegee for its plot logics and ethics, this chapter argues that Washington’s repurposing of a former site of enslavement into a modern campus required an eye and appreciation for aesthetics. Though antebellum plantations were often quite beautiful, their beauty belied the terror of human bondage and ecological exploitation. Slave garden plots, however, were the “botanical gardens of the dispossessed” where the enslaved cultivated beauty and created a folk culture through music, dance, storytelling, and the coaxing of plants from the ground to nourish and heal Black bodies ravaged by the plantation system.6 Tuskegee similarly used art and performance to exemplify the beauty and vitality of Black life and culture. I use the term repurpose in this chapter with both its primary meaning and the etymology of its root word, purpose, in mind: to design and to propose.7 In doing so, I capture how the intentional design and regeneration of Tuskegee’s landscape, as discussed in chapter 1, were part and parcel of the careful aesthetic curation of Black subjectivity. Furthermore, through the school’s dynamic performance culture, I show how Tuskegeeans proposed the southern New Negro as the exemplar of Black progress and futurity uniquely equipped to meet the challenges of the new century.

Washington and his staff aimed to “reconstruct the image” of Black people by repurposing the phonic and visual legacies of the plantation against the continued hegemony of racial stereotypes derived from slavery and minstrelsy.8 Through oratory, singing, and new media technologies such as sound recording,

photography, and cinema, the Tuskegee-trained New Negro resignified the sounds and sights of the modern, emancipated Black body at a moment when Black people were largely regarded as a sociopolitical problem for the nationstate. Washington and his staff thus staged the southern New Negro as one who was no longer embittered by the slave past and could therefore master and repurpose it—materially, rhetorically, and aesthetically—for the postemancipation future.

Although Tuskegeeans did not explicitly proscribe the “criteria of Black art,” as would the subsequent generation of New Negroes, Washington’s writings and the school’s performance culture reveal an aesthetic preference for merging quotidian forms derived from southern Black vernacular culture and the slave past (the plantation, plantation melodies, and agricultural labor) with Victorian notions of beauty, morality, domesticity, and the dignity of labor.9 In effect, Tuskegee’s aesthetic vision grafted New England ideals onto Black southern life and culture, the industrial North onto the rural South, in hopes that “pretensions to middle-class respectability” would culminate in a gradual and nonthreatening enfranchisement.10

In his oratory and especially in his support for preserving and innovating the plantation melodies, Washington celebrated Black sonic practices that balanced naturalness and simplicity with training, technique, and virtuosity. He preferred expertise devoid of excess, acumen without affectation, mastery cloaked in modesty. Tuskegee’s visual archive similarly attempted to reconcile agricultural and industrial labor with Victorian sartorial aesthetics because the school was especially keen to prove that agriculture was compatible with the new, postemancipation desires of Black southerners. By juxtaposing Tuskegee’s photographic archive alongside the writings of Mrs. Margaret Murray Washington, who served as lady principal and director of the Women’s Department, I also show how Tuskegeeans used sartorial aesthetics and selffashioning to regender the Black body in freedom and to reclaim domesticity for a people who had relatively recently been denied both.

Booker T. Washington’s aesthetic philosophy was materialist, pragmatic, and utilitarian. Rather than “mere abstract public speaking,” he explained in Up from Slavery, he preferred “to do something to make the world better and then to be able to speak to the world about that thing.” And “the actual sight of a first-class house that a Negro has built,” he insisted, “is ten times more potent than pages of discussion about a house that he ought to build, or perhaps could build.”11 According to the literary scholar William Andrews, “by claiming a radical distinction between action and speech and by disclaiming language as anything more than a referential medium, Washington denie[d] the performative

dimension of representation.”12 I argue, however, that repurposing, as the strategy of world making that unifies Washington’s political and aesthetic philosophies, is, in fact, a highly performative, imaginative, aspirational, and even speculative act. Much like plotting, repurposing envisions things that are not (yet) as though they are, can be, or will be. Ironically, though Washington famously professed to enjoy biography and newspapers over fiction, preferring to read about “a real man or a real thing,” repurposing is precisely the praxis that links his work to the domain of fiction and the imagination, wherein he marshalled aesthetics to propose and speculate on new futures.13 For instance, upon sending his editor, Walter Hines Page, a collection of photographs, drawings, and “a water color representation” of school grounds, Washington was careful to include the following caveat: “With respect to the colored drawing of the grounds . . . you will note that there are several buildings which are not here now but we were drawing on our imagination only to the extent that they are buildings which we expect to erect as soon as we can get the money for them. . . . The luxuriant foliage which you see displayed on the colored drawing is supposed to represent Tuskegee in the summer time when everything is then at its best.”14

By drawing on his imagination and depicting the campus as he hoped it could be rather than how it was at the time, Washington was engaged in a protospeculative and Afro-futurist endeavor long before such concepts existed as Black studies praxes. Alongside designing the landscape to imagine its transformation, Tuskegeeans used aesthetics to propose new possibilities for Black being. Photographs of Tuskegee campus life depict faculty and students dressed in ornate suits, ties, hats, dresses, and blouses even as they perform agricultural and industrial labor. Despite Washington’s preference for “a real man or a real thing,” Tuskegeeans routinely used artifice and performance to clean up and dress up, repurposing the “raw material” of slavery and the plantation to propose new possibilities for Black being: the southern, Tuskegee New Negro.15

In what follows, I examine Tuskegee’s vast discursive, sonic, and visual archives to demonstrate how the logic and practice of repurposing the plantation landscape through eco-ontological regeneration animated the school’s broader aesthetic vision for the southern, Tuskegee New Negro. In the first half of this chapter, I explore how Washington’s oratory and the Tuskegee Institute Singers’ performances of plantation melodies moved within and against the ludic tones of minstrelsy to imagine new indexical possibilities for modern Black sound on the turn-of-the-century stage. In contrast to Houston Baker’s reading of Washington as a trickster figure who “mastered” the tones and types of the minstrel mask to transform Tuskegee into a “flourishing” “southern, black Eden” in the rural south, I argue that Washington’s caricaturing of the Black

masses in his speeches exposes the limits of mastering violent aesthetic and political-economic forms and falls short of a wholesale repurposing because it threatens to reproduce subjection.16 By contrast, Washington’s support for the Tuskegee Institute Singers, who continuously distinguished their sound from that of minstrel performers, represents a more effective regeneration of the sounds of slavery toward new and more liberatory ends.

The second half shifts to how Washington and his staff used visual culture to intervene in a turn-of-the-century scopic regime that reduced the Black body to the scripts of slavery and minstrelsy. Through photography, Washington crafted an “aesthetics of work” at Tuskegee that resignified the laboring Black body as proficient and autonomous and evinced to white and Black audiences alike how Tuskegee was training students for a bourgeois middle-class future in the Global Black South, equipping them with the tools and knowledge to resolve the postemancipation dilemma between labor and freedom. Tuskegee’s visual archive also illuminates the distinctly gendered dimensions of its conception of the southern New Negro. Whereas slavery “ungendered” the Black body—forcing enslaved women to perform field labor alongside their male counterparts and enslaved men to perform domestic tasks usually assigned to enslaved women— Tuskegee established a strict gendered code of conduct, dress, and labor to contest the racial-sexual abuses of the plantation past. Before subsequent generations (rightly) challenged traditional gender norms and pursued cosmopolitan mobility, Tuskegeeans regarded the ability to “stay put,” erect homes, and embrace the forms of femininity and masculinity denied them under slavery as constitutive of their eco-ontological regeneration and ability to plot agrarian futures rooted in autonomy and self-determination.

SOUNDING THE NEW NEGRO ON THE TURN- OF- THE- CENTURY STAGE

Booker T. Washington was hardly alone or unusual in his effort to generate a Black aesthetic tradition from plantation ruins. A host of turn- of-thecentury Black artists and performers—Harry T. Burleigh, Charles Chesnutt, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Henry O. Tanner, Aida Overton Walker, and Bert Williams, among others—were also variously engaged in adapting and reforming plantation aesthetics in literature, music, and performance. In the years immediately following emancipation, white and Black composers compiled and rearranged enslaved people’s folk songs, many of them

created on southern plantations, into Western art music. Ironically, these Negro spirituals were often mobilized to fundraise for Black educational institutions, such as Fisk University and Tuskegee, and to evince African Americans’ propensity for Western conceptions of “high culture.” Similarly, by the 1890s Black performers dominated blackface minstrelsy, capitalizing on white nostalgia for the “happy darky” stereotypes of the antebellum South. Despite their debased caricatures of Blackness, however, minstrelsy and vaudeville provided Black performers with the financial means to develop a more dynamic Black theater.17 Thus, at the same time that slavery, the plantation, and minstrelsy signified a shameful past, they also equipped these artists and race leaders with the rudiments of a distinctly African American cultural tradition that set the stage for the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro Movement of the 1920s and 1930s.

As an internationally acclaimed orator, Washington was in effect a performer who actively shaped and was shaped by the soundscape of turn-of-the-century Black performance culture. He toured the United States, giving speeches on the Negro problem, education, and business to help raise money for Tuskegee and Black education more generally. “An audience brought out his latent powers of persuasion,” writes his biographer, Louis Harlan. “On the platform he lost a little of his formalism and dignity, scored points by humorous anecdote and inverted metaphor, played one part of his audience against another like a choir director, and evoked in each segment of his audience in turn the emotions of pride, hope, nostalgia, amusement, and mutual esteem.”18

Alongside minstrelsy and vaudeville, the lecture circuit was an important site of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century performance and entertainment. In the antebellum period, Black orators such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth mounted the lecture stage to denounce the atrocities of slavery and to advocate for abolition and gender equality. Through oratorical performance, Washington inherited the mantle of Black leadership when he delivered the Atlanta Exposition Address in 1895. Houston Baker designates Washington’s Atlanta Address as the “commencement of Afro-American modernism,” for it was the first time when Black citizens “found an overriding pattern of national leadership or an approved plan of action that could guarantee at least the industrial education of a considerable sector of the black populace.”19

Ironically, Washington’s performance of Black modernity required him to don and appropriate the “minstrel mask,” for “the mastery of the minstrel mask by blacks,” Baker argues, was the “primary move in Afro-American discursive modernism.”20 Washington thus slipped into the “phonic legacies” of minstrelsy, peppering his speeches and essays with folksy anecdotes rendered in Black southern dialect to ingratiate himself with and seemingly garner the sympathies

of white listeners and readers. He recalls in Up from Slavery: “One morning, when I told an old coloured man who lived near, and who sometimes helped me, that our school had grown so large that it would be necessary for us to use the hen-house for school purposes, and that I wanted him to help me give it a thorough cleaning out the next day, he replied, in the most earnest manner: ‘What you mean, boss? You sholy ain’t gwine clean out de hen-house in de day-time?’ ”21

Washington’s use of such minstrel conventions contradicts the aims of his broader uplift project, which sought to counter debased caricatures of Black people. However, Baker suggests that Washington, as a trickster figure, is not only in on the joke but redeploys it with aplomb because the minstrel mask “constituted the form that any Afro-American who desired to be articulate—to speak at all—had to master during the age of Booker T. Washington.”22 Indeed, this mastery of the political and aesthetic forms of modernity was a crucial strategy that African Americans used to prove their fitness for inclusion and citizenship. Yet Washington’s detractors, then and now, have rightfully taken issue with such sonic blackening up. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, for instance, contended that such antics had the degrading effect of suggesting “that the Negroes of the black belt [sic] as a rule were hog thieves until the coming of Tuskegee.”23 For the historian Kevin Gaines, Washington and his contemporaries’ donning of the minstrel mask was consistent with an uplift ideology that held up “culturally backward, or morally suspect” African Americans as evidence of the educated African Americans’ “own class superiority.”24 The rural, country folk were essentially used as a foil to the bourgeois Tuskegee-trained New Negro.25

Baker’s conception of the “mastery of form” seemingly reflects the logic of the repurposed plantation; however, there is a nuanced and significant distinction between them, at least as it relates to Washington’s sonic blackening up. Mastering and redeploying the tones and types of minstrelsy, however strategically, ultimately risks perpetuating its debased caricatures of Black people. Repurposing, in contrast, insists on the wholesale transformation of the original form toward new and more life-sustaining ends. Though Washington’s intention was to advance the cause of uplift, this sonic blackening up still adhered too closely to the original, degraded form and demonstrates the potential limits of the “mastery of form” as a strategy of Black resistance.

Listening to Washington’s and Tuskegee’s broader sonic archive, however, reveals that he also generated new indexical possibilities for Black sound that contradicted those of minstrelsy. Through oratory and especially his support for preserving and innovating the plantation melodies at Tuskegee, Washington articulated a loose set of criteria for New Negro sonic aesthetics that masked

intense training, technique, and virtuosity under the cloak of naturalness and the everyday. These sounds were no doubt imbricated (and in tension) with the ludic tones of minstrelsy and vaudeville, but Washington ultimately believed that Black art should be rendered “in the language which the masses of people spoke . . . [and] which they could understand.”26 This practical positionality that reconciled the most modern training with naturalness and simplicity was the crux of his aesthetic philosophy.

In Up from Slavery, Washington recalls his student days at Hampton, where he studied the mechanics of oratory and elocution and received “private lessons in the matter of breathing, emphasis, and articulation.” Yet he also acknowledges that even the best technique cannot “take the place of soul in an address.” Soul here refers to the seemingly organic and improvisatory performance style often associated with Black vernacular culture. It is the ability “to forget all about the rules for the proper use of the English language, and all about rhetoric and that sort of thing, and . . . to make the audience forget all about these things, too.”27 Washington knew all too well, though, the rhetorical and literal dangers of disregarding “the proper use of the English language” for Black people on the turn-of-the-century stage and how it could be used to reinforce stereotypes about their alleged intellectual inferiority. Even an orator of Washington’s stature was not immune to such crude associations. In a review of the Atlanta Exposition Address, James Creelman, a reporter for the New York World , at once revealed the importance of the occasion and the precariousness of the Black stage performer:

The eyes of the thousands present looked straight at the Negro orator. A strange thing was to happen. A black man was to speak for his people. . . . There was a remarkable figure; tall, bony, straight as a Sioux chief, high forehead, straight nose, heavy jaws, and strong, determined mouth, with big white teeth, piercing eyes, and a commanding manner. The sinews stood out on his bronzed neck, and his muscular right arm swung high in the air, with a lead-pencil grasped in the clinched brown fist. His big feet were planted squarely, with the heels together and the toes turned out. His voice rang out clear and true, and he paused impressively as he made each point. Within ten minutes the multitude was in an uproar of enthusiasm. . . . It was as if the orator had bewitched them. 28

Creelman’s account of this momentous occasion in southern and African American history blurs the lines between antebellum and postbellum stages. His objectification and scrutiny of Washington’s body resembles nineteenthcentury performances of Black subjection, especially the auction block, where

slave traders engaged in the detailed anatomization of the enslaved Black body, inspecting teeth, groping muscles, and tasting sweat. This slippage between the lecture platform and the auction block demonstrates the easy diminution of performances of Black self-fashioning and Washington’s colossal challenge: despite his notoriety and accomplishments, he could easily be reduced once again to the status of a slave, at least rhetorically.

In his review of Up from Slavery in 1901, William Dean Howells, regarded as the dean of American letters, hailed Washington as an “Afro-American of unsurpassed usefulness, and an exemplary citizen,” while also writing that the “ancestral Cakewalk seems to intimate itself for a moment in Mr. Washington’s dedication of his autobiography to his ‘wife, Mrs. Margaret James Washington,’ and his ‘brother, Mr. John H. Washington.’ ”29 Originally, the cakewalk was an embodied practice of resistance whereby enslaved peoples parodied their owners’ affected dance and sartorial stylings. After emancipation, it became an international dance craze featured in minstrel and vaudeville performances. Howells quickly disavowed the cakewalk as not at all characteristic of the author, but the fact remains that he reduced Washington’s simple gesture to bestow respect on his wife and brother by using an honorific before their names to a form of racial caricature. That Howells could not imagine Washington’s gesture of respect outside of minstrelsy demonstrates how the Black body in freedom continued to bear the marks of enslavement for white readers and the challenge Washington and his generation of artists confronted on the stage and page.

Creelman and Howells tethered Washington to the auction block and the minstrel stage, respectively, but Washington’s voice in the lone extant recording of his speech (recorded about ten years after the original Atlanta Address, most likely for his personal archive) departs dramatically from these geographies of Black subjection and positions him firmly on the postbellum lecture platform. It is the sound of uplift. In the recording, Washington speaks with a quick, clipped Victorian diction. He rolls his Rs and enunciates every syllable with the utmost precision, likely a result of his elocution training at Hampton and despite his own emphasis on naturalness and the importance of disregarding proper English grammar. Paradoxically, he sounds more like a New Englander, the touchstone for his moral and aesthetic philosophies, than a southerner or a formerly enslaved person.

Washington’s pivot toward Victorian bourgeois sound to announce Black southern modernity elucidates the aesthetics of his uplift philosophy more generally. In writing his two-volume study The Story of the Negro (1909), a sketched history of the race from its origins in Africa to the present day, Washington

adapted and distilled into an aesthetic principle the sounds of the rural, country folk who surrounded Tuskegee.30 At the Tuskegee Negro Conferences, attendees often shared their success stories in farming, acquiring land, and purchasing homes. “In this way,” Washington wrote in 1910, “there grew up out of our conference a sort of oral literature which led us to take a wholesome pride in the progress that colored people were making. . . . In writing ‘The Story of the Negro’ I have tried to do on a larger scale just what the stories of the Negro conference have done—to supply a kind of literature that will inspire the masses of my own people with hope, ambition, and confidence.”31

T. Thomas Fortune, Washington’s ghostwriter and sometimes friend, admonished Washington for a writing style in his early publications that adhered too closely to public speaking. “ ‘You have ideas to burn,’ Fortune told him, ‘but your style of expression is more oratorical than literary, and in the written word the oratorical must be used most sparingly.’ ”32 However, in The Story of the Negro Washington (and presumably his other ghostwriters) intentionally developed an oral-literary style derived from the sounds of the folk masses that aimed to give expression to “what was stirring in the minds of the Negro people during that long period when there was no one to voice their thoughts or tell their story.”33

Elevating and regenerating vernacular practices through intense training and contemporary methods, while retaining their ordinary and quotidian essence, reflect the logic of the repurposed plantation as both a political and aesthetic philosophy. Washington’s oratorical mastery did not excuse his caricaturing of rural Black southern dialect, but his innovation of modern Black sound was on much firmer ground when he used the orality of Black farmers to develop a writing style that was both accessible to and in service of the masses of Black people.

THE SOUNDSCAPE OF THE TUSKEGEE INSTITUTE

By the turn of the twentieth century, Tuskegee had developed a rich performance culture that included oratory, singing, band and instrumental music, and theater. Students participated in weekly “rhetoricals” where they performed orations on themes related to their respective trades and industries, such as “Choosing and Preparing the Land,” “The Crops,” and “Constructing the Farm House.”34 This practical use of oratory—what Washington called “dovetailing” or “correlation,” a pedagogical innovation that aimed to close the gap between the academic and industrial curricula—reflects Washington’s insistence on

“Afterlives of the Plantation is a groundbreaking, brilliant, and paradigm-shifting account of Black modernity that reconsiders and recenters the Black South as a key vector in understanding the Black world. Jarvis C. McInnis mines neglected archives to reroute and reroot the legacies of the plantation in order to consider not only Black subjugation but also Black imagination and freedom dreaming. This book is a must-read for thinkers interested in race, agriculture, ecology, and cultural history.”—Imani Perry, author o f South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation

“Afterlives of the Plantation is a veritable paradigm earthquake. Turns out, Booker T. Washington’s exhortation to rural Black folk to ‘cast down your buckets where you are’ was less a backwardlooking compromise than a vision of Black modernity. Backed by meticulous research, McInnis recasts Tuskegee as an Atlantic experiment in turning the carceral landscape of the plantation into an engine of Black economic, social, and cultural development—provision grounds for a liberated future. It is time we cast down our analytical sights on the Global Black South.”

—Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression

“Declaring that Black modernity in the Americas is first and foremost agricultural, McInnis shows us early twentieth-century subjects who repurposed the plantation. This deeply researched book offers us capacious readings of south-south relations (within the United States and between the United States and the Caribbean), as well as rural and agricultural circuits for rethinking Black modernity and Black modernisms.”—Faith Smith, author of S trolling in the Ruins: The Caribbean’s Non-sovereign Modern in the Early Twentieth Century

“McInnis’s magisterial history of Black modernity, with Tuskegee Institute at its center, reveals how the industrial education model shaped a wide range of experimental projects that loosened slavery’s hold on the plantation throughout the Global Black South. Readers will see Marcus Garvey, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, and others as McInnis sees them: as Tuskegee students. Afterlives of the Plantation is carefully researched and exquisitely written, a gift to a world suffering ongoing ecological catastrophe.”—Erica R. Edwards, author of Th e Other Side of Terror: Black Women and the Culture of U.S. Empire

Jarvis C. McInnis is the Cordelia and William Laverack Family Assistant Professor of English at Duke University.

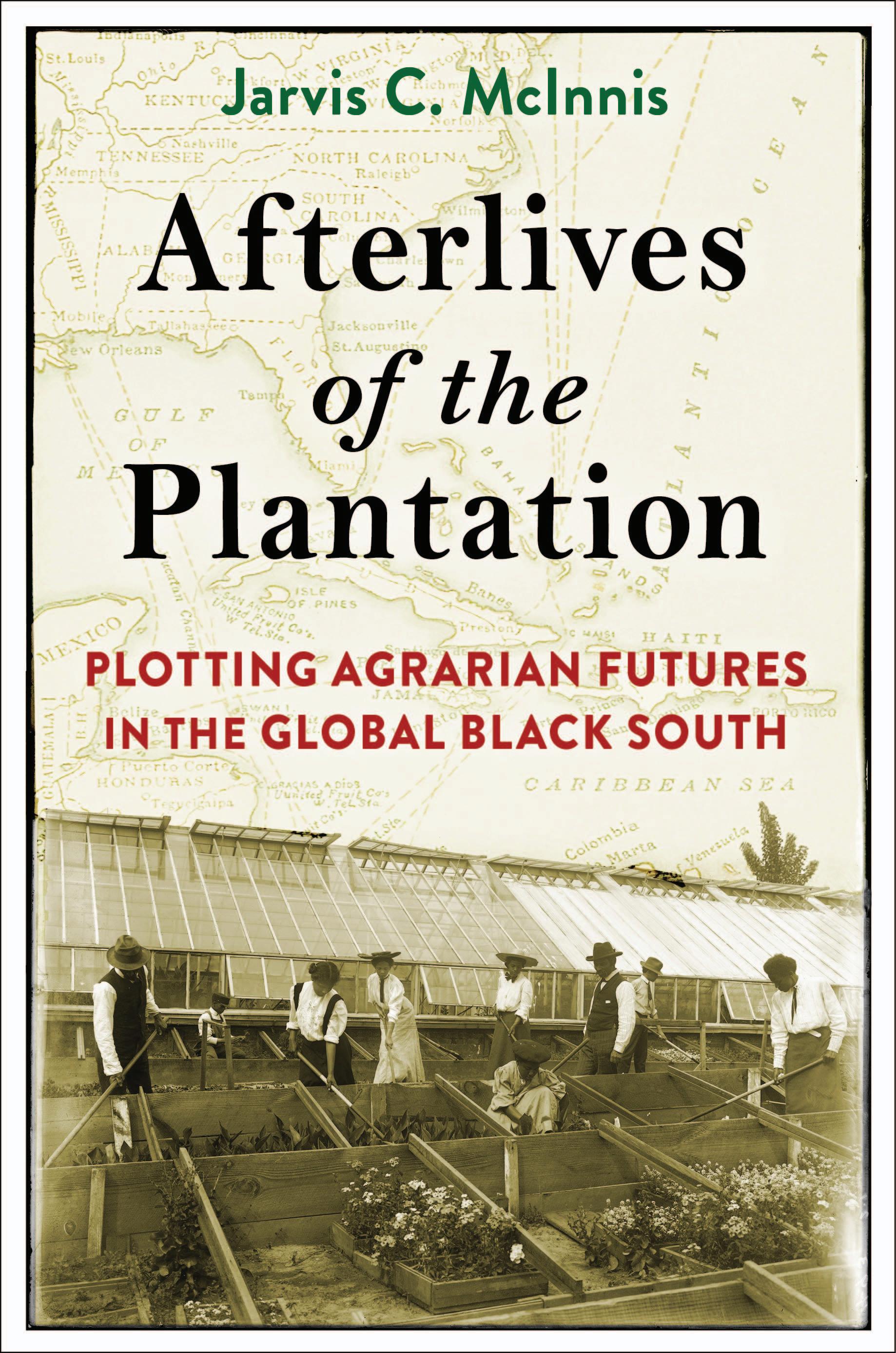

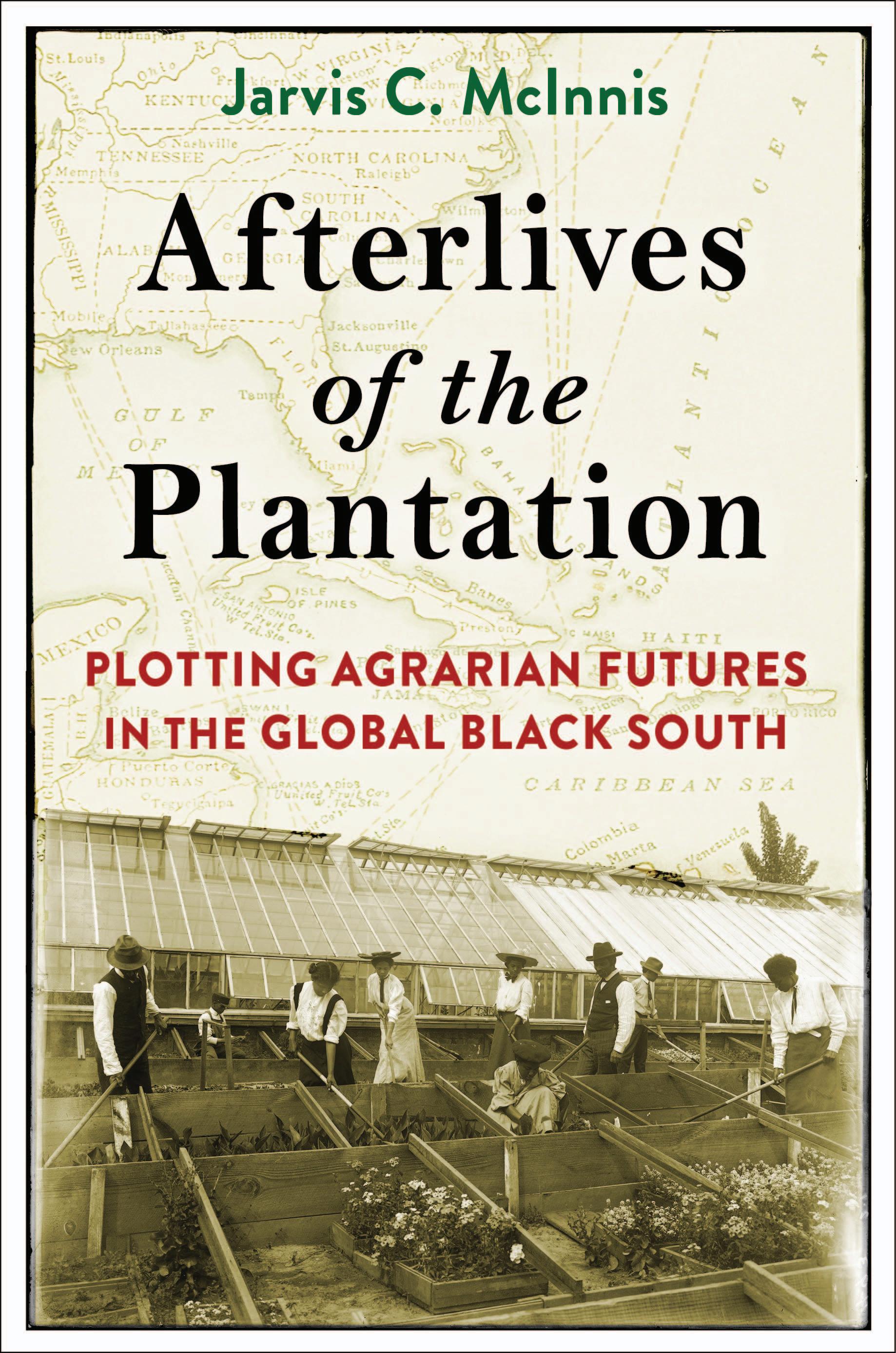

Cover design: Noah Arlow Cover image: Frances Benjamin Johnston, Students Taking Care of Flowers in Beds Near Green Houses, Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, Alabama , Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection (Library of Congress). Map: Jamaica, Panama Canal, and Central and South America (New York: Great White Fleet, United Fruit Company Steamship Service, 1912).