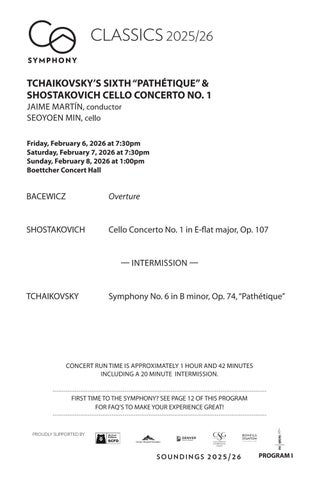

TCHAIKOVSKY’S SIXTH “PATHÉTIQUE” & SHOSTAKOVICH CELLO CONCERTO NO. 1

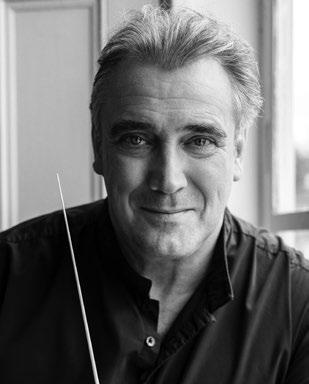

JAIME MARTÍN, conductor

SEOYOEN MIN, cello

Friday, February 6, 2026 at 7:30pm

Saturday, February 7, 2026 at 7:30pm

Sunday, February 8, 2026 at 1:00pm

Boettcher Concert Hall

BACEWICZ

Overture

SHOSTAKOVICH

Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107

— INTERMISSION —

TCHAIKOVSKY

Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74, “Pathétique”

CONCERT RUN TIME IS APPROXIMATELY 1 HOUR AND 42 MINUTES INCLUDING A 20 MINUTE INTERMISSION.

FIRST TIME TO THE SYMPHONY? SEE PAGE 12 OF THIS PROGRAM FOR FAQ’S TO MAKE YOUR EXPERIENCE GREAT!

PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY

JAIME MARTÍN, conductor

Music Director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra since 2019, and Chief Conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra since 2022, Spanish conductor Jaime Martín has also held the positions of Chief Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland (2019-2024), Principal Guest Conductor of the Spanish National Orchestra (2022-2024) and Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of Gävle Symphony Orchestra (2013-2022). In 2024/25, Martín became Principal Guest Conductor of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales.

Having spent many years as a highly regarded flautist, Jaime turned to conducting full-time in 2013 and quickly became sought after at the highest level. Highlights of the 2024/25 season include a critically acclaimed BBC Proms appearance with BBC NOW and leading an 11-day Beethoven Festival with the Melbourne Symphony, conducting all nine symphonies. He also returned to conduct orchestras in Barcelona, Spain, the UK, and Australia.

For the 2025/26 season, Martín will lead the Melbourne Symphony on a UK and Europe tour, their first full international tour since 2019, with stops at the Edinburgh International Festival and BBC Proms. He will also conduct major orchestras across Europe, the US, and Australasia. His extensive discography includes recordings with Gävle Symphony, Orquestra de Cadaqués, Barcelona Symphony, London Philharmonic, and recent releases on the Melbourne Symphony label. Martín is Artistic Advisor and former Artistic Director of the Santander Festival and a Fellow of the Royal College of Music, London, where he was a flute professor.

SEOYOEN MIN, cello

Seoyoen Min has served as Principal Cello of the Colorado Symphony Orchestra since the 2019/20 season. A native of South Korea, she is a versatile performer with an active career as a soloist, orchestral musician, and chamber artist in the United States and abroad.

As a featured soloist, Seoyoen has appeared with numerous orchestras, including the Colorado Symphony and Wyoming Symphony. A founding member of the Edith String Quartet, she has collaborated with distinguished musicians and ensembles in both traditional and contemporary settings. She remains deeply engaged in Colorado’s chamber music community and performs regularly as a soloist and chamber musician.

In addition to her orchestral work, Seoyoen performs at music festivals across the United States, including the Grand Teton Music Festival, and is an enthusiastic educator who teaches privately and presents guest masterclasses. She holds a Master of Music degree from Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music and a Bachelor of Music degree from Seoul National University.

BIOGRAPHIES

GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ

(1909-1969)

Overture

COMPOSITION & PREMIERE OF WORK:

Grażyna Bacewicz was born on February 5, 1909 in Łódź, Poland, and died on January 17, 1969 in Warsaw. She composed the Overture in 1943. The work was premiered on September 1, 1945 at the Contemporary Polish Music Festival in Kraków by the Kraków Philharmonic, conducted by Mieczysław Mierzejewski.

CSA LAST PERFORMANCES:

This is the CSA premiere performance of this piece.

INSTRUMENTATION:

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.

DURATION:

About 6 minutes.

Composer, violinist, pianist and writer Grażyna Bacewicz (Grah-ZHEE-nah baht-SEV-ich) was among Poland’s leading musicians during the early 20th century and the country’s first female musician to gain international prominence since Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831), who toured widely throughout Europe as a virtuoso before being engaged as pianist at the Russian court and whose compositions influenced those of Frédéric Chopin. Bacewicz was born in 1909 into a musical family in Łódź, 75 miles southwest of Warsaw, and her father gave Grażyna her first instruction in piano, violin and music theory. She received her early professional training at the local music school before entering the Warsaw Conservatory in 1928, where her talents as violinist, composer and pianist developed in parallel. After graduating in 1932, she received a grant to study composition with Nadia Boulanger at the École Normale de Musique in Paris from Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the famed composer, pianist and Poland’s Prime Minister in 1919, who used his fortune to aid, among many other causes, the country’s most promising young musicians. Bacewicz also studied violin in Paris with the Hungarian virtuoso and teacher Carl Flesch, and gained her first notice as a soloist in 1935 at the Wieniawski International Violin Competition in Warsaw.

The following year she was appointed Principal Violinist of the Polish Radio Orchestra in Warsaw and began touring as a soloist in Europe, occasionally appearing with her brother Kiejstut, a concert pianist. (The University of Music in Łódź is named jointly in their honor.) Bacewicz composed and gave clandestine concerts during World War II, after which she resumed her touring career and joined the faculty of the Academy of Music in Łódź. In 1953, she retired as a violinist to devote herself to composition and teaching. For the three years before her death from a heart attack in 1969, three weeks short of her 60th birthday, Bacewicz taught composition at the Academy of Music in Warsaw. She received numerous honors throughout her career, including awards for lifetime achievement from the City of Warsaw, Polish Composers’ Union and People’s Republic of Poland, served twice as Vice-Chair of the Polish Composers’ Union, and was an accomplished writer of short stories, novels and autobiographical anecdotes.

“The premise of Bacewicz’s Overture,” wrote Polish composer and conductor Artur Malawski, “is rhythm and motoric movement.” Bacewicz composed the Overture seemingly in defiance of the time of its creation — 1943, the year of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising that presaged the final transport of the city’s Jews to the extermination camps. The Overture begins with four soft, quick strokes on the timpani that may have been borrowed from the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony — short–short–short–long — which the BBC broadcast throughout the war as a hopeful symbol for Allied victory (i.e., Morse code for the letter “V”: dot–dot–dot–dash). The Overture, however, whose muscularity and orchestral brilliance are cast into relief by a lyrical central episode, was perfectly suited to the time of its premiere, at a Contemporary Polish Music Festival in Kraków on September 1, 1945, four months after Germany had surrendered.

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107

COMPOSITION & PREMIERE OF WORK:

Dmitri Shostakovich was on born September 25, 1906 in St. Petersburg, and died on August 9, 1975 in Moscow. He wrote his First Cello Concerto in 1959 for Mstislav Rostropovich, who was the soloist in the work’s premiere with the Leningrad State Philharmonic Orchestra on October 4, 1959; Yevgeny Mravinsky conducted.

CSA LAST PERFORMANCES:

November 18-19, 2026 with Peter Oundjian conducting and Silver Ainomae on cello.

INSTRUMENTATION:

The score calls for piccolo, pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons, contrabassoon, horn, timpani, celesta and strings.

DURATION:

About 30 minutes.

By the mid-1950s, Dmitri Shostakovich had developed a musical language of enormous subtlety, sophistication and range, able to encompass such pieces of “Socialist Realism” as the Second Piano Concerto, Festive Overture, and Symphonies No. 11 (“The Year 1905”) and No. 12 (“Lenin”), as well as the profound outpourings of the First Violin Concerto, Tenth Symphony and late string quartets. The First Cello Concerto, written for Mstislav Rostropovich during the summer of 1959, straddles both of Shostakovich’s expressive worlds, a quality exemplified by two anecdotes told by the great cellist himself: “Shostakovich gave me the manuscript of the First Cello Concerto on August 2, 1959. On August 6th, I played it for him from memory, three times. After the first time he was so excited, and of course we drank a little bit of vodka. The second time I played it not so perfect, and afterwards we drank even more vodka. The third time I think I played the SaintSaëns Concerto, but he still accompanied his Concerto. We were enormously happy....”

“Shostakovich suffered for his whole country, for his persecuted colleagues, for the thousands of people who were hungry. After I played the Cello Concerto for him at his dacha in Leningrad, he accompanied me to the railway station to catch the overnight train to Moscow. In the big

PROGRAM NOTES

waiting room we found many people sleeping on the floor. I saw his face, and the great suffering in it brought tears to my eyes. I cried, not from seeing the poor people but from what I saw in the face of Shostakovich....”

The ability of Shostakovich’s music, like the man himself, to display the widest possible range of moods in succession or even simultaneously is one of his most masterful achievements. (The same may be said of Mahler, whose music was an enormous influence on Shostakovich.) The opening movement of the First Cello Concerto may be heard as almost Classical in the clarity of its form and the conservatism of its harmony and themes, yet there is a sinister undercurrent coursing through this music, a bleakness of spirit not entirely masked by its ceaseless activity. The following Moderato grows from sad melodies of folkish character, piquantly harmonized, which are gathered into a huge welling up of emotion before subsiding to close the movement. The extended solo cadenza that follows without pause is an entire movement in itself. (Shostakovich had used a similar formal technique in the Violin Concerto No. 1 of 1948.) Thematically, it springs from the preceding slow movement, and reaches an almost Bachian depth of feeling. The cadenza leads directly to the finale, one of Shostakovich’s most witty and sardonic musical essays. With disarming ease, the main theme of the first movement is recalled in the closing section of the finale to round out the Concerto’s form. “It is difficult to think of any modern concerto,” wrote Alan Frank, “that pursues its objectives in so purposeful a manner with little or no exploration of by-ways.”

In addition to its purely musical value, Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto deserves a significant footnote in Russia’s modern artistic history. The piece was written for Rostropovich, about whom the composer said in his purported memoirs, Testimony, “In general, Rostropovich is a real Russian; he knows everything and he can do everything. Anything at all. I’m not even talking about music here, I mean that Rostropovich can do almost any manual or physical work, and he understands technology.” Shostakovich and Rostropovich were close friends during the composer’s later years, and they lived as neighbors for some time in the Composers’ House in Moscow. Rostropovich gave the Concerto both its world premiere (Leningrad; October 4, 1959) and its first American performance (Philadelphia; November 6, 1959), and was the inspiration for Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 2 of 1966. In 1974, Rostropovich and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, defected to live and work in the West; four years later they were deprived of their Russian citizenship and became “non-persons” in their native land. In 1979 Dmitri and Ludmilla Sollertinsky published their Pages from the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich, which was essentially the Soviet rebuttal to the scathing criticism leveled in Testimony, issued several months earlier. Though Rostropovich was one of Shostakovich’s best friends and most important artistic motivators, his name is not even mentioned in the Sollertinskys’ Pages, and the First Cello Concerto is dismissed in the book with a mere, passing half-sentence.

PETER

ILYICH

TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74, “Pathétique”

COMPOSITION & PREMIERE OF WORK:

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on May 7, 1840 in Votkinsk, Russia, and died November 6, 1893 in St. Petersburg. He composed the Sixth Symphony, his last important work, between February 16 and August 24, 1893. The composer conducted the work’s premiere on October 28, 1893, with the Orchestra of the Imperial Russian Music Society in the Hall of Nobility in St. Petersburg.

CSA LAST PERFORMANCES:

November 3-5, 2023 with Peter Oundjian conducting.

INSTRUMENTATION:

score calls for piccolo, three flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.

DURATION:

About 46 minutes.

Tchaikovsky died in 1893, at the age of only 53. His death was long attributed to the accidental drinking of a glass of unboiled water during a cholera outbreak, but this theory has been questioned in recent years with the alternate explanation that he was forced to take his own life because of a homosexual liaison with the underage son of a noble family. Though the manner of Tchaikovsky’s death is incidental to the place of his Sixth Symphony in music history, the fact of it is not.

Tchaikovsky conducted his B minor Symphony for the first time only a week before his death. It was given a cool reception by musicians and public, and Tchaikovsky’s frustration was multiplied when discussion of the work was avoided by the guests at a dinner party following the concert. Three days later, however, his mood seemed brighter, and he told a friend that he was not yet ready to be snatched off by death, “that snubbed-nose horror. I feel that I shall live a long time.” He was wrong. Grief and sense of loss was felt by music lovers in Russia and abroad as the news of his passing spread, and memorial concerts were quickly planned. One of the first was in St. Petersburg on November 18th, just twelve days after he died. Eduard Napravnik conducted the Sixth Symphony on that occasion, and it was a resounding success. The “Pathétique” was wafted by the winds of sorrow across the musical world, and became — and remains — one of the most popular symphonies ever written, the quintessential expression of tragedy in music.

The title “Pathétique” was suggested to Tchaikovsky by his elder brother, Modeste. In his biography of Peter, Modeste recalled that they were sitting around a tea table one evening after the premiere, and the composer was unable to settle on an appropriate designation for the work before sending it to the publisher. The sobriquet “Pathétique” popped into Modeste’s mind, and Tchaikovsky pounced on it immediately: “Splendid, Modi, bravo. ‘Pathétique’ it shall be.” This title has always been applied to the Symphony, though the original Russian word carries a meaning closer to “passionate” or “emotional” than to the English “pathetic.”

PROGRAM NOTES

The “Pathétique” Symphony opens with a slow introduction dominated by the sepulchral intonation of the bassoon, whose melody, in a faster tempo, becomes the main theme of the exposition; the tension subsides for the yearning second theme. The tempestuous development begins with a mighty blast from the full orchestra. The recapitulation is more condensed, vibrantly scored and emotionally intense than the exposition. Tchaikovsky referred to the second movement as a scherzo, though its 5/4 meter gives it more the feeling of a waltz with a limp. The third movement is a boisterous march. A profound emptiness pervades the closing movement, which maintains its slow tempo and mood of despair throughout.

©2025 Dr. Richard E. Rodda