13 minute read

PROFILE: THE NUVAYESTEWA FAMILY — TRADITIONAL HOPI LIFEWAYS

The Nuvayestewa family lives on First Mesa on the Hopi reservation. They are deeply steeped in tradition and culture and are members of the Corn Clan, which holds tribal responsibility for feeding community members. The Nuvayestewa family has taken on a leadership role with regard to traditional food and related cultural practices. Leon Nuvayestewa, Sr. describes the role that traditional foods and gathered plants played in his healing process from a severe sickness during his youth:

There is a hospital in Tuba City, but I didn’t go there when I got ill. I went to my grandparents’ house and my grandparents, my uncles, and the Medicine Man joined together to make me well. What I remember was that there was food involved, there was natural Hopi medicine involved, and there was prayer as a part of healing. The medicines that I remember being used were bear root, a plant that grows in the forest, and they gave me chunks of it to bite off, chew, and put juice on my body. Cedar was also used from the trees on the reservation. It was boiled and I was bathed every morning by my grandmother. She would give me a cup of the juice to drink every day, and she would burn the cedar while I stood over it with a blanket and let the smoke purify me. The food that my grandmother fed me was blue cornmeal, made into a mush, blue marbles, or pikki bread. I also drank the spring water from the springs at my home. Wild food, Neeveni, was also prepared for me – the tea that grows out on our lands and wild spinach. The other part I remember is that prayers were made every morning and every evening for me. The Hopi Medicine Man prescribed this medicine for me. My father told me, my uncles too, “Food is medicine for your body to keep you strong.”

– Leon Nuvayestewa

Evangeline Nuvayestewa shares her perspective on the strong matrilineal traditions around food and seeds at Hopi. The contexts of food and farming traditions provide spiritual guidance and teach discipline around family roles. Hopi men plant and once the corn is born, it becomes the women’s responsibility to prepare and nurture it for its role in ceremonies and meals. The women process the corn differently depending on whether it is used for food or ceremonies. The knowledge that Hopi women have is taught by their mothers and grandmothers and is passed down to their daughters and granddaughters. In every aspect of food and farming, women play a role and hold knowledge. Whether it’s determining needs for planting, cooking food during planting, or distributing corn for ceremonies, Hopi women hold deep cultural knowledge that’s passed through generations.38

The Nuvayestewa family retains their traditional knowledge of food, including food farmed at home and gathered Neeveni (wild foods), for health.

Leon’s daughter Valerie comments, “We were absorbing everything, all the information around us.” Family members across generations regularly gather Neeveni, cultivate their crops and gardens on Hopi, and raise their children in traditional Hopi lifeways. As a former diabetes educator, Valerie emphasizes that the benefits of traditional foods are both spiritual and physical – providing enhanced immunity, a stronger microbiome, and resistance to diseases. For her, cultivating and consuming traditional foods and passing on her knowledge has been lifesaving. Most recently, Valerie’s teenage daughter Erin Eustace began planting her own garden:

For me, planting was where I needed to start and its taught me compassion, nurturing, patience, persistence, and its also taught me commitment – being committed to your field everyday and being there to check on all your plants, making sure everyone is ok. It’s taught me that you have to be committed to anything in life you are passionate about and take all these little steps to get to the finished product…to me, the ultimate glory was to bring my food home to my mother.39

– Erin Eustace

Today, across the Colorado Plateau, Native farmers are reviving seed saving and other community-based agricultural and traditional food practices.

I think an important aspect of Indigenous resistance is learning to really be sovereign, and to restore our traditional lifeways, one of which is food sovereignty, which is my passion. One of my biggest goals in life is restoring our food systems in our communities because a lot of us are in food apartheids where you don’t have access to any foods. I tried to go with eating more traditional foods, but I realized that I can’t really get them anywhere unless I grow them myself.…I’m trying to revive that knowledge and revive that seed, so that we can practice it again….The seed and the technique that was handed off to us and prepared for us. So that’s one thing I tried to get across to all the young people that we were working with. This is literally thousands of years of knowledge and intricate systems that our ancestors had to learn through trial and error, and probably starving sometimes through failure and famine. So we need to honor this knowledge and keep it here and don’t forget, don’t forget these things, these lessons, that they passed on for us.

– Aaron Lowden

Community-based agriculture proves to be fertile ground for cultivating vibrant new systems and new markets. These are emerging across the Colorado Plateau to address both health disparities and access to healthy food, as well as to create alternative frameworks for economic development. Section IV discusses this move- ment-building work in greater depth. Alongside these innovative practices remains the deep focus on transmitting, sustaining, and documenting traditional knowledge of food, seed saving, and gathering practices to Native youth.

MODERN NATIVE LEADERSHIP IN FOUR KEY AREAS

MODERN NATIVE MOVEMENT-BUILDING ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU

Protecting Culturally Important And Sacred Places

As Native people made seasonal pilgrimages from the low deserts to the high-elevation forests, engineered societies, created art and historical accounts, and built cultures – they developed deep relationships with places across the Colorado Plateau that endure today. Almost all of these places, whether on tribal reservations or public lands, hold cultural significance to Plateau Tribes. Some of these locations are particularly important, such as ceremonial grounds, pilgrimage destinations, or lands used for other private reasons. Some Tribes reserve the word “sacred” for these places. Today, the culturally significant landscapes and sacred places of the Colorado Plateau remain central to modern day tribal culture.

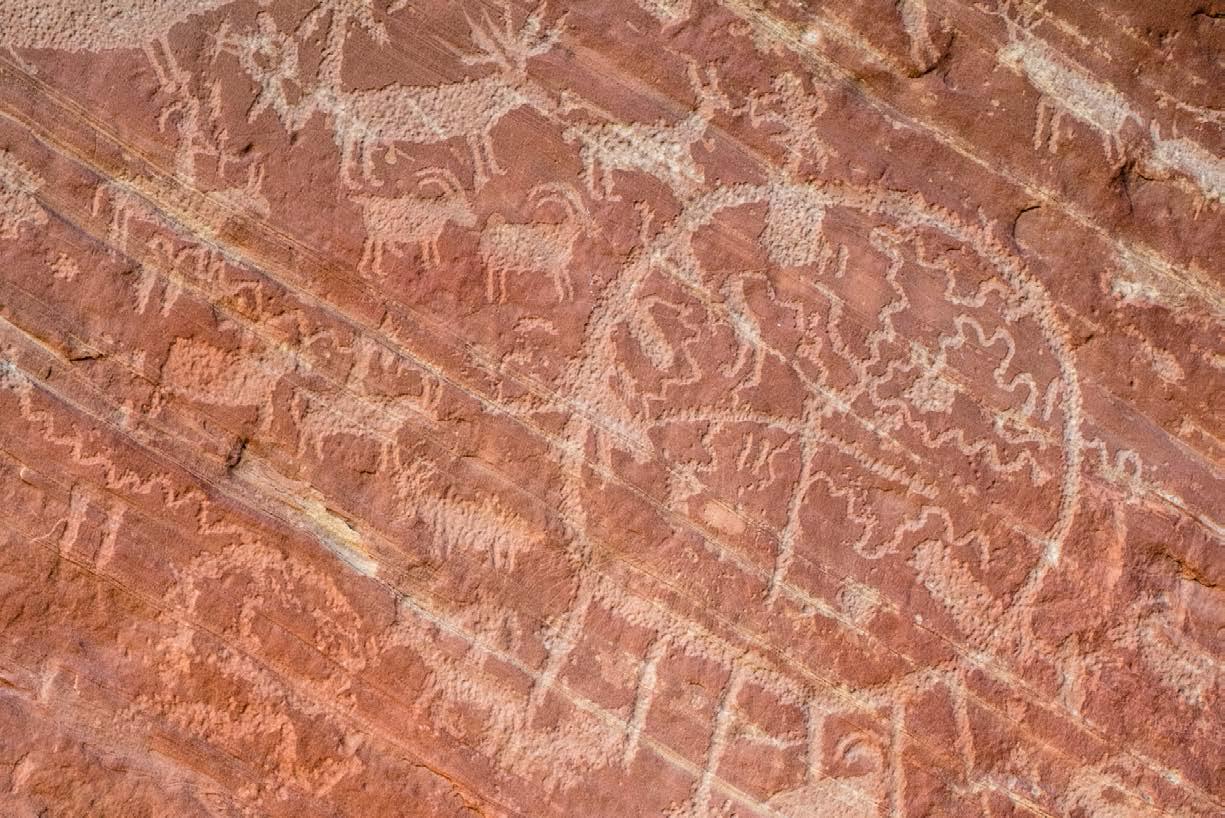

A culturally important place is one with “information left by our ancestors.”… I think that’s very important because without that information it will be difficult for us to make people aware that we are a part of this place. If I identify petroglyphs that are coming down from the bottom of the Grand Canyon to as far as Deming to Salt Lake City to the San Juan river. If we see that petroglyph, we know that our ancestors were there. So just having ties to the information on petroglyphs really opens that door for us to get that information….And having the map art identifying these places, it really makes people aware that we are a part of all of these places and want to make sure that people understand that the reason why we left was, because we had, we’re given a destination, our own little middle place. And we found it here at Zuni.

– Octavius Seowtewa

And so these [culturally important] places are like in Hopi, they call them the footprints of our ancestors. That’s literally the English definition of how we view our history. So you know, if you remove those places off the landscape then you erase a good part of who we are, and you erase our right to call ourselves and identify as Hopi. So they’re, they’re physical, they’re tangible entities. Things out there in the landscape that have metaphysical and spiritual qualities that feed into your daily life as an individual Hopi person. So these ancestral sites, whether they’re a village or spring or whatever, they’re all a part of our cultural identity.

– Lyle Balenquah

The ancestral sites in Greater Chaco have stories and these stories are mostly with the elders. People who’ve heard the stories from their parents or their grandparents. Now that oral history is finally, finally being accepted and listened to in this world, especially in academia. They don’t call it myths any longer; now they are saying, “Oh well maybe the Indigenous people had knowledge.” And I say “How do you think we survived here? Do you thought we just all sat around?”

– Kendra Pinto

Many interviewees clarified the importance of reserving the term “sacred place” for locations of the highest importance in order to avoid dilution of the word sacred.

I think that word ‘sacred’ has been thrown around a lot. We’re still trying to figure out the word to use, but it’s been thrown around so much that it’s lost its importance. Culturally important to me is a better word because there’s different levels of sacred and to identify something like – well, people call it the Zuni Heavens. Now that would be a really sacred place, but there’s different levels of culturally identified areas. Using the word sacred for all of them really takes away the importance of some of these places that are really important, it dilutes that information.

– Octavius Seowtewa

I find that term ‘sacred’ problematic. And I try real hard to remove it from my own personal language use. I think it’s a Western concept. I’ll use Hopi as an example. During one of our consultation meetings this question was posed to us by some federal agencies. They put the map on the wall and they said, “Okay, show us what is sacred.’ And it was, it was hard for our advisors, for us as individuals, to simply say, “okay, we’re going to draw a line around this.” One of the men went to his office and came back with a picture of the earth. He says this, “Do you want to put a boundary on something?” Know that when I’m asked to define what is sacred, almost immediately in my mind, I have to draw that boundary, exclude something from a larger perspective.

– Lyle Balenquah

Even when the word “sacred” is used, its use is evolving away from attempting to pinpoint a “site” and rather recognizing the importance of the larger surrounding landscape.

I can’t say that one pile of rocks as a shrine or one cliff dwelling or one petroglyph should receive more protection than another. They should all be protected equally.

These are sacred places, not sacred sites. A site to me is a point on a map, and it would be too easy to say, “We’ll protect this spring, or we’ll protect this rock shrine.” When actually it is the context of place that makes those areas sacred and worthy of protection.40

– Jim Enote

One of the largest challenges faced by Tribes on the Colorado Plateau is the threat posed to culturally significant and sacred places, particularly when those places are located off-reservation on lands designated as multiple-use by the federal government. In some areas, like within the boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park, competing uses are limited due to protective designations. Yet even when designations exist, there are limitations. The effort to revive uranium mining just outside the borders of Grand Canyon threatens its lands and waters, including the waters that feeds the Havasupai Tribe.41

Regardless of protective designations, visitation abounds and looting, vandalism, and irresponsible tourists bring their own threats. Even innocent overuse takes a toll on cultural sites nested within the fragile high-desert landscape of the Colorado Plateau. Finally and relatedly, the designations themselves bring their own risk of raising a region’s public profile. For example, visitation to Bears Ears surged more than 72% from 2016 to 2017 following monument designation, and Fodor’s ranked Bears Ears at the top of its list of places to visit in 2019 – an act that will only drive more visitors to that landscape.42

The majority, if not the entirety, of the Colorado Plateau holds significance as ancestral lands. As a result, Colorado Plateau Tribes and tribal cultural resource management staff are stretched thin with consultation requests, ensuring that federal land managers are aware of the cultural importance of lands, advocating for responsible visitation practices, and creatively leveraging existing legal frameworks to prevent damage when necessary.

CASE STUDY: GREATER CHACO AREA

Perhaps nowhere on the Colorado Plateau is the tension between use of lands for energy development and the values of public health and traditional lifeways more pronounced than in the Greater Chaco Canyon region in northwestern New Mexico. Greater Chaco has long been inhabited by Navajo and Pueblo people. Chaco Canyon itself was a center of Puebloan culture and economic life where Native people built great houses, astronomical obser- vation sites, and ceremonial kivas. Today’s Pueblo people find the Greater Chaco Canyon region “to continue to be places of prayer, pilgrimage and living connections to our ancestors”43 and emphasize that “the greater landscape of the Chaco Canyon region is not a resource to be managed parcel by parcel, but as a complete, living landscape that since time immemorial has sustained Pueblo people.”44

Chaco Canyon is located in the San Juan Basin, which has been one of the most productive natural gas basins in the United States for decades, and oil resources are located near Chaco Culture National Historic Park. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has already leased and allowed drilling on the vast majority - approximately 90% - of the San Juan Basin’s federal lands.45 Over 23,000 oil and gas wells are currently in production, including in several areas that overlap with Chacoan roads, villages, and other highly significant resources.46

There is this idea that there’s nobody out there in Greater Chaco – that its just Chaco and the walls and the kivas. Then I say, “No, actually I live out there. My grandmother’s always lived out there. Her father lived out there. That’s why I say it’s a living culture.” And it’s being impacted; it’s a living culture that’s being impacted every second of the day…there’s cultural properties, unknown and unmarked artifacts, things that probably should be TCPs all over the place. People moved around in that area and there are artifacts everywhere, and they’re still unmarked and unknown when you go out there. And so any extraction activity that goes on out there is going to have a potential effect on those cultural resources. Sometimes it’s hard to believe the Bureau of Land Management when they conclude that the extraction will have no significant impacts. How can they say that the companies are not going to disturb it, and at the same time that they are going to tear it up?

– Kendra Pinto

It is hard to overstate the extent that these oil and gas plays adversely impacted nearby Navajo Nation communities by compromising air quality, water quality, and bringing a many-fold increase in trucking activity on local roads.47

I asked my grandmother once if she knew what was happening with oil and gas that’s out in the greater Chaco area and her only reply was, “The land’s not the same.” And just those few words that she spoke illustrate how much more diverse the seed life and all life was before this intrusion came in and the extraction started. The companies literally changed our environment around us. That’s not just mental, it’s physical. Plants grow less and less every year, there are less and less deer, elk that used to hang out around the house don’t come by any more, there are less snakes, and just less wildlife overall. My grandmother used to get water from a spring behind her house that doesn’t run today. That’s a big change. We literally have less water. One of the things that blows my mind is that we literally have less of what we did before, and when we bring up these issues, sometimes we’re called radical or loudmouths. Instead what we should all be talking about is how we don’t have as much water as we used to have before the extraction started. Also, I can’t even stress enough how loud it is. It keeps me up at night sometimes. It causes a lot of stress and it makes me angry. I used to do a lot of hiking within the area up on Lybrook Mesa and there were trails or dirt roads to go get wood or whatever. But now they’ve cleared this huge, single lane dirt road up there for the oil and gas.

– Kendra Pinto

As Navajo tribal member and public health advocate Kendra Pinto describes, the threats in Greater Chaco extend from tangible, public health issues such as elevated hydrogen sulfide detected during air testing at schools to the destruction of cultural resources to the deterioration of the larger landscape as a whole. However, many Navajo families who own allotted lands within the Basin are receiving economic benefits from the leasing. This causes deep conflicts within communities and within the Navajo Nation at the governmental level.

The threat to the Greater Chaco Canyon landscape and the campaign led by Tribes have prompted legislative solutions at both the federal and state level to prevent any future leasing or development of minerals owned by the U.S. government located within an approximately 10-mile protected radius around the national park.48 These measures are controversial both within the Navajo Nation, whose support for the buffer has oscillated, and among tribal members living in the Greater Chaco region who economically benefit from the leasing. The ultimate management of these lands remains uncertain.

It is important to remember that the task of safeguarding sacred places and culturally important landscapes exists both on-reservation and on off-reservation public land. However, where Tribes have full jurisdiction, Tribes tend toward making management decisions that limit or prohibit harmful uses of sacred places and culturally important lands. There are, of course, exceptions to this rule – such as the coal mining that occurred on Black Mesa for decades. Even there, the Hopi Tribe approved the mining under circumstances that can only be described as suspect,V and the local Hopi and Navajo people living in the area strongly opposed the mining. In general, tribal management of reservation lands historically elevates protection and sensitive management of sacred places and culturally important lands.

People aren’t aware that Zuni had an opportunity to extract within our reservation in the 60s and 70s. Our governor actually put in some test pits and natural gas, coal and CO2 were identified to be extracted. And the religious leaders came to hear about the extraction and they met with the governor and told him that this was not right. Our governor, I’m glad, listened to the religious leaders. So he stopped all of the extractions…. We actually have religious leaders listening to their elders and the past, and not benefiting from extraction, and protecting Mother Earth.

– Octavius Seowtewa

V It is now well-known that the Hopi Tribe’s attorney at the time of the coal mining lease negotiations, John Boyden, violated his ethical duty to the Hopi by working concurrently for Peabody Coal and the Hopi Tribe while facilitating the various land settlements and partitions that paved the way for mining leases. Wilkinson, C. F. (1996). Home Dance, the Hopi, and Black Mesa coal: Conquest and endurance in the American Southwest. BYU Law Review, 449. University of Colorado Law School: Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. Retrieved from http://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/698/

IN FOUR KEY AREAS