23 minute read

MODERN NATIVE LEADERSHIP IN FOUR KEY AREAS

Beginning in the mid-2000s, a series of gatherings of Native cultural and traditional leaders from the 11 Colorado Plateau Tribes were convened with the goal of reviving ancient inter-tribal networks and deepening inter-tribal collaboration. Out of the discussions that took place over years, four areas emerged as those needing deep and sustained attention from Native leaders over the coming decades: sustaining and reviving Native languages; protection of water; advancing community-based sustainable agriculture; and protecting culturally important lands and sacred places. Water, language and traditional knowledge, seeds and agricultural know-how, and sacred places are all interwoven with Native cultures on the Plateau and are deeply threatened today. As such, each of the movements described below serves as a part of the larger, collective effort to sustain Native lifeways and culture, and to heal the Plateau itself.

Sustaining Native Languages

One of the greatest challenges facing Native people on the Colorado Plateau today is the effort to sustain and revive Native languages. The number of living Native languages spoken and number of speakers both testify to the Tribes’ strength in overcoming decades of directed federal and state policy efforts designed to eradicate these languages forever. As shown in Figure 1 below, the Colorado Plateau houses eight of the nine counties in the United States with the highest percentage of Native language speakers. The only outlier is the Bethel Census area in Alaska. A full 20% of all American Indian language speakers live in one of two Colorado Plateau counties: McKinley County, New Mexico, which overlaps with both the Navajo Nation and Zuni Pueblo; and Apache County, Arizona, over one-half whose land area lies within the Navajo Nation.2

Yet, as Figure 2 shows, many Native languages on the Colorado Plateau remain critically endangered with some speakers, particularly in small Tribes, numbering only in the hundreds. A few things about Figure 2 are worth noting from the outset, both for their own merit and as an illustration of larger trends related to data in Indian Country. While the information displayed was developed on the best, most recent data available, census or other survey data in Indian Country is generally unreliable, particularly with regard to language questions. For example, while the U.S. Census does publish data on Native populations, the Census Bureau counts anyone who says they are Indian, regardless of tribal enrollment, in its Indian population numbers.III Additionally, Figure 2 does not reflect the demographic distribution of Native language speakers and the sharp decline in language speakers in younger generations. To provide a concrete example, estimates from the American Community Survey on the Hualapai Reservation indicate that 77% of the population over the age of 65 speak Hualapai as compared to only 7.4% of children ages 5-17.3

Est. Native Language Speakers in Select Colorado Plateau Tribes

As the interviewees make clear, the risks posed by language loss runs deep and extends far into Native culture and traditional lifeways.

I see languages as that thread that holds a basket together, and when you start to unravel that basic weaving of language, then things begin to fall apart. And so language is an integral part of not just learning how to speak it, but knowing the social, cultural context of how that language is used and how it can carry a particular community’s perspectives on things and why we believe the way we do and why we value the things that we do. In that way, I think, language is really critical to a lot of understanding of these other places and things that we talk about.

– Dr. Christine Sims

Language is a big part of our lives that we as Hopi people ourselves don’t realize because when we want to talk about deeper things, we use the Hopi language because it’s easier and you can explain yourself really in more detail. Where in English, you can talk about it, but you can’t really express and explain yourself. In the Hopi

III For a detailed explanation of the manifold problems resulting from no entity taking responsibility for accurately tracking tribal enrollment through the census or other means, see DeWeaver, Norm, Assessing the Challenges in American Indian Population Data in The State of Indian Country Arizona, Volume 1 (2013) pp 23-25. As a result of the problems described by DeWeaver, the data in Figure 2 should be considered estimates and nothing more.

Modern

NATIVE LEADERSHIP IN FOUR KEY AREAS MODERN NATIVE MOVEMENT-BUILDING ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU language, we understand how the communication is more deeper without hesitation... the songs are all in Hopi and Tewa. It’s our language and I don’t know how many people really, really know what the songs are about. That’s a real issue. I think if we lose that, we also lose the rest of the culture. I think that it is all based on language.

– Bucky Preston

Hearing words in Diné language has more meaning and significance. Especially when you hear it in ceremonial settings, it brings puzzles and pieces together. For example, plants are named in ways that connects you to be identified by the plant for its use and purpose, opposed to how it’s viewed as a scientific name. Our language has a stronger purpose and brings more power hearing it through songs and prayers. It’s more inspiring when we speak our language to acknowledge the universe, the earth, and all beings in our surroundings before we acknowledge ourselves. These teachings are the fundamental laws of nature, taught by our elders. It’s really a good teaching to speak our language and to be recognized by the holy people.

– Cynthia Wilson

The youth are coming to realize that there is a place for Zuni language only and the fact that they have been a part of having activities within our religious activities drives home that point. There aren’t prayers that are recited in English. It’s all Zuni. And in order for them to grasp that prayer and come to an understanding of what the prayer is, they have to speak and learn Zuni.

– Octavius Seowtewa

Despite the widely-recognized importance of sustaining and protecting Native languages, Native children today are growing up predominantly exposed to English. Both in the school setting and at home, Native children on the Plateau do not have the same, or even moderately similar, exposure to their Native languages that children did even one generation ago. Unfortunately, research indicates that heritage language loss can occur as quickly as within two generations.4 And the diminishing number of Native language speakers reflects that reality.

I think most communities would agree that it’s the maintenance and the re-strengthening of language that has to do with cultural knowledge, and also building relationships within a speech community, that has to do with passing on tribal perspectives and values. Those elements of language are really what most communities want to see their children be able to learn. It’s not just learning how to speak a language, but it’s how that language is used across all those contexts. And of course, the key thing is that spiritual, cultural foundation that the Indigenous people have and language is part of that. So one of the things that is most challenging right now is this: How do you create the kinds of opportunities for our children to learn those things when so much of their modern day lives are impacted by a global language like English?....Today, most Native children spend eight hours of their wak- ing hours in English-based contexts, whether it’s school or afterschool kinds of things when they go home. They see and hear media all in English. And so carving out and re-instituting ways in which language would traditionally have been passed on is a real challenge. It’s a real challenge for every Native community.

– Dr. Christine Sims

Great potential remains in resisting this trend. Studies show that it takes approximately five to seven years to acquire age-appropriate proficiency in a heritage (second) language when consistent and comprehensive opportunities in the heritage language are provided.5 Today, across the Plateau, strong Native leadership in many Tribes has spearheaded efforts to revive and sustain Native languages. These leaders design programs from the ground-up to meet the unique needs of the tribal communities they serve. The support of a tribal government impacts these efforts significantly; for example, the leadership of the Navajo Nation led to the development of a full curricula of Navajo language instruction – a tool that many other Tribes on the Plateau have not developed. Developing curricula and other innovative programs provide alternatives to relying on transmission at home as the sole way for that language to survive and are durable solutions for children whose family members are not speakers. The case studies below highlight three different Native-led models of language transmission active on the Plateau today.

CASE STUDIES: DIFFERENT MODELS OF LANGUAGE TRANSMISSION

Private Early-Age Montessori Learning

Several Tribes on the Plateau have begun language revitalization efforts with Montessori schools focused on early age students. Since 2000, the 100% tribally funded Southern Ute Montessori Academy has provided Ute language instruction to Ute students, ranging from six weeks through sixth grade.6 The Ute language is among the most critically endangered on the Plateau and the three Ute Tribes (Southern Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, and Ute Indian Tribe) are creating a Ute language immersion program that can be implemented in public schools, including in Ignacio public schools where children matriculate when they leave the on-reservation Southern Ute Montessori school.7 Another example occurs on the Cochiti Pueblo; although Cochiti Pueblo is located just outside the Colorado Plateau, the Cochiti people speak Keres, which is a major Puebloan language across the Plateau. The Keres Children Learning Center, an on-reservation Montessori preschool uses the Cochiti Keres language to teach preschool and kindergarten students for six hours a day. The school, which incorporates Cochiti Pueblo traditions into classes, was collaboratively designed by tribal leaders from Cochiti Pueblo, education experts, and community members. It is led by Cochiti Pueblo members Trisha Moquino and Olivia Coriz and receives foundation funding from the Kellogg foundation, among others.8

Working on Many Fronts: The Acoma Pueblo’s Efforts

At the Acoma Pueblo, a community survey in the 1990s revealed that children were no longer acquiring Acoma Keres as a first language. In response, the Pueblo created a pilot two-week summer immersion program that later grew into a formalized six-week program. Parents observed that after the summer camp, children would use the language games and songs they learned at home and that they “were using each other’s Indian names rather than their English names.” Additionally, many parents made a greater effort to speak more Acoma Keres at home.9 In turn, this intergenerational engagement resulted in transmission of the traditional knowledge that only Acoma elders and fluent Keres speakers possessed. From the foundation of summer immersion programs, the Pueblo began expanding Keres cultural teaching to the classroom in local school systems. First, offerings were included at the local Bureau of Indian Education school, then at a local public high school and elementary school, and finally to a parochial pre-kindergarten program. The Pueblo faced many challenges along the way, including surmounting a claim that targeting classes at Acoma Pueblo members discriminated against other students.10 Another issue arose from the “fact that many of our Acoma elders and Keres-speaking adults lacked formal teaching degrees, which created administrative issues for public schools under the No Child Left Behind Act.”11 Acoma Pueblo, with other New Mexico Tribes and Pueblos, launched a multi-year effort that culminated in 2003 when New Mexico adopted an alternative certification for speakers of Native languages teaching Native languages in New Mexico public schools. The New Mexico Public Education Department only issues these alternative certifications as recommended by a Pueblo or Tribal Nation. This provides a framework where the Pueblos and Tribes have authority to deem individuals qualified to teach their indigenous language, as well as over the way lessons and programs are carried out.12

Native Languages in Public Schools – The Flagstaff Unified School District

The Flagstaff Unified School District (FUSD) has emerged as a leader in innovative approaches to advancing Navajo language transmission on the Colorado Plateau, and is increasing efforts with the Hopi language as well. Serving 15 different school sites and over 9,600 students, FUSD’s student enrollment is 25.30% Native Americans.13 Today, FUSD’s foreign language requirement can be met with Navajo language classes, and FUSD offers a full

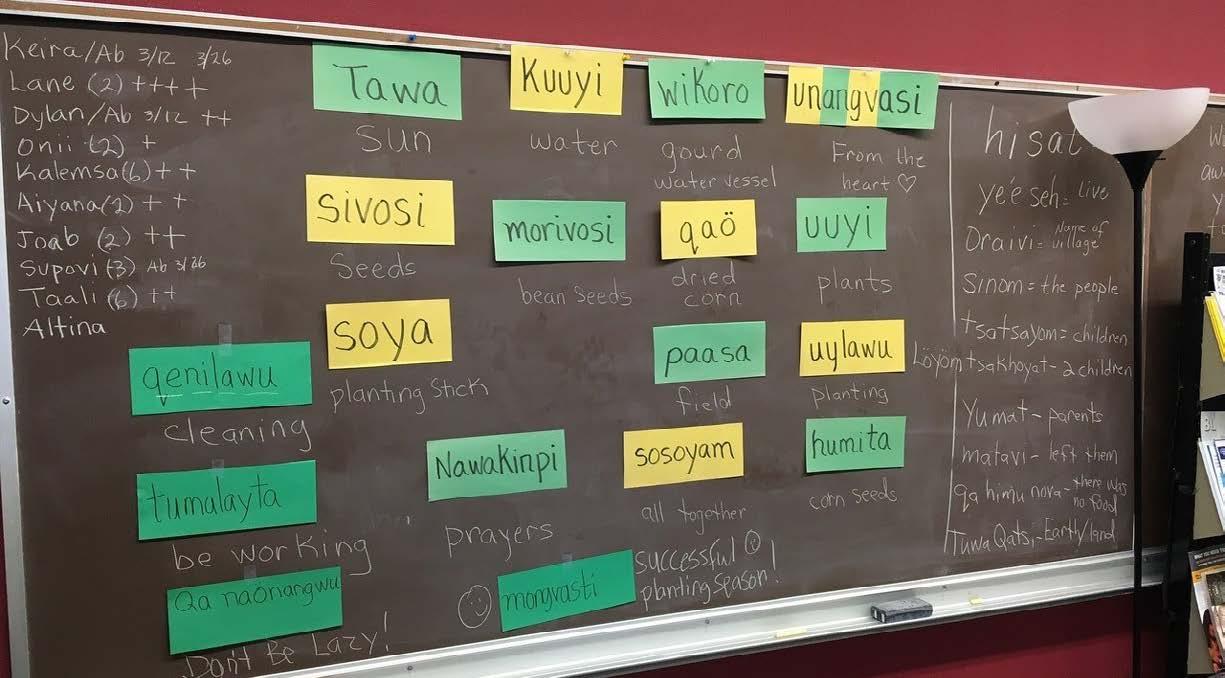

Navajo language immersion program at its Puente de Hózhó charter school. Puente de Hózhó has two dual-language programs comprised of a Navajo Immersion Language Program and a Spanish-English Bilingual Program that serves students from kindergarten through 5th grade. A 6-12th grade International Baccalaureate Continuum is in the process of being established.14 While FUSD’s Navajo language efforts are forward-thinking and responsive to the largest Native population in the area, children from the Hopi Tribe and other non-Navajo Tribes are in the difficult position of having to either take Navajo or Spanish to satisfy their language requirement.15 To begin to address this, FUSD partnered with Hopi educators to offer Ita Hopi Lavayi This is a Hopi immersion program within FUSD summer programming. Active since 2009, the program has been successful in transmitting language. It has also laid a foundation for Hopi educators to push for Hopi language classes to satisfy FUSD’s foreign language requirement.16

MODERN NATIVE LEADERSHIP IN FOUR KEY AREAS

MODERN NATIVE MOVEMENT-BUILDING ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU

However creative and effective these approaches, more resources and support are urgently needed to bolster efforts to sustain Native languages while they still exist on the Colorado Plateau. In New Mexico, a promising development has emerged as a result of the Yazzie/Martinez v. New Mexico lawsuit. Brought by families and school districts against the State of New Mexico, the suit alleged that the state failed to provide students—especially low-income students, Native Americans, English language learners, and students with disabilities—the programs and services necessary for them to learn and thrive. It also challenged the state’s failure to sufficiently fund these programs and services. In July 2018, the court held for the families and ruled that all New Mexico students have a right to be college and career ready. It additionally held that the Public Education Department has a duty to ensure school districts are adequately spending the money provided to them to effectively provide students with a proper education. The judge instructed the legislature and executive branch to find a funding system to meet the constitutional requirement. The implications of this decision are far-reaching, and legislators are now introducing bills to comply with the order.17 This decision does not impact education in Arizona, Utah or Colorado, but could be hugely impactful for the Tribes and Pueblos in New Mexico. Dr. Christine Sims comments on this potential:

In the future, I hope to see a change from “these little drop in the bucket” approaches, especially when we don’t have that sustainable funding source. State funds for language programs in schools from K-12 are particularly important because that’s where our children spend 180 days of the school year, eight hours a day, five days a week. Those financial supports are necessary in order to help these programs either begin or expand. What people don’t realize is that it takes quite a bit of effort to plan out how you’re going to do this kind of language instruction. We don’t have the ready resources of curriculum materials or instructional materials for most Native languages. Instead, language speakers have to create that. Right now, we don’t have a big school publisher that’s going to come in and produce Native language books or anything. So these things that are being proposed as remedies in the Yazzie/Martinez lawsuit have the promise of beginning to help build those support systems, the infrastructure that’s going to enable not only Tribes to create these programs, but to sustain them and grow them. It will be interesting to see to what extent New Mexico state education agencies provide those necessary resources for Native languages in the future.

– Dr. Christine Sims

Finally, it is important to note the data gap and lack of data uniformity in the efforts of states on the Colorado Plateau to track data related to the number of students studying Native languages. Of these states, New Mexico leads the way. Figure 3 shows the number of Native languages being taught in public schools in New Mexico, and the number of students being reached; similar data was unavailable for Utah, Colorado, and Arizona.

Source: American Indian Policy Research & Teacher Training Center, & University of New Mexico College of Education. (2018).; Language and Culture Bureau. (2018). New Mexico Public Education Department.

MODERN NATIVE LEADERSHIP IN FOUR KEY AREAS MODERN NATIVE MOVEMENT-BUILDING ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU

Protecting Water

We are the hydrologic cycle. We believe this because that’s how our Hopi civilization was developed from being dry farmers, farmers in a desert, and from choosing to stay here...Faith develops from there, so all of our ceremonies, Kachina ceremonies, social ceremonies, it’s always talking beautifully about rain. How if we can put our hearts and minds together and be sincere, the rain will come.

– Vernon Masayesva

When we plant, we run and then the women, they pour water on us because we depend on the moisture, the clouds. Everything is based on water, water, water, water, everything in Hopi is water.

– Bucky Preston

Water, in all its forms, is deeply tied to Native peoples’ cultures, ceremonies, and traditions on the Colorado Plateau. The scarcity of precipitation heightens the importance of water in this high-desert landscape. The semi-arid to arid Colorado

Plateau receives an average precipitation of 8-12 inches annually. The high-alpine mountainous areas of the Colorado Plateau such as the top of Sleeping Ute Mountain on the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s lands, the Chuska mountains on the Navajo Nation, or the Zuni Mountains on the Zuni Reservation receive more precipitation, averaging over 20 inches annually.18

So Zuni have their own religion and culture and, having lived where they’ve always lived, a strong connection to that land in the Homeland and the environment. Their beliefs and practices have evolved from that relationship. And basically, almost everything Zuni does traditionally throughout the year and their religion and way of life does reflect the relationship with the land and especially water, being in a semi-arid desert, water is critical to life. Water has been a central part of a lot of the prayers and the beliefs and practices. For example, springs have a special relationship to not only the physical world, our world of what it provides with life, but then a window into our spiritual other worlds of entities and mystical beings and just sacredness and connecting all the worlds. Springs reflect that kind of belief system and then also rivers, especially our Zuni River that connects her Homeland with another place of cultural importance. And the River is that umbilical cord that kind of ties the two distant places together. And as a place of making offerings of food to our ancestors there into the River, that then gets carried down to that spiritual world. So it’s a water place. Both the practical and the more abstract kind of metaphysical connection between our culture or current people and our ancestors and the spirit world and with rain or water in particular. And a lot of our dances and prayers relate to the clouds and the precipitation, rain, snow being a blessing and when they come they, they represent our ancestors, bringing their blessings both spiritually and in all the ways that people benefit from that, but also practically for the life giving force it gives to the crops – Zuni being a traditional farming culture and, and everything that’s needed with the water for life and blessing. So rain and water definitely has its unique place in the Zuni belief system.

– Kirk Bemis

Overall, the Colorado Plateau lands on which Native people settled are water-rich. The majority of major river systems, both mainstem rivers and their tributaries, in the Colorado River Basin flow through tribal lands on the Colorado Plateau. These rivers include the Colorado River itself, the Little Colorado River, the San Juan River, the Zuni River, the Pine River, the Navajo River, the Mancos River, the La Plata River, the Animas River, the Florida River, the Chaco River, the Black River, and the Salt River. In addition, scientists have documented over 15,000 springs across the Colorado Plateau’s public lands and many more are present on tribal lands.19 Large aquifers of pure groundwater that underlie tribal lands supply both artesian springs that bubble up from the ground and wells that provide drinking water.

Yet, over six decades of mining and extractive activity targeting the coal, uranium, oil and gas deposits that underlie the Colorado Plateau have damaged culturally important surface and groundwater resources. This extensive extractive and industrial activity has both contaminated and depleted the Plateau’s scarce water resources.

MODERN NATIVE LEADERSHIP IN FOUR KEY AREAS MODERN

The White Mesa Ute Community of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is located between Blanding and Bluff in southern Utah. The community sits at the foot of Bears Ears National Monument and in the larger San Juan River watershed. Only three miles from the community center sits the White Mesa Uranium Mill, the United States’ only operating conventional uranium mill. Along with uranium mined from the Colorado Plateau, radioactive waste from sites across North America are sent to the White Mesa Mill for “processing” and permanent disposal in the facility’s tailing ponds. For over two decades, the White Mesa Mill has processed and disposed of this waste. Today, the mill’s waste pits contain radioactive and contaminated wastes from rare-metals mining, uranium-conversion plants, and contaminated defense facilities, among other sources. Radioactive pollution and other contaminants are emitted from the mill into the air, land, and groundwater, threatening public health and the environment.20

A community-led, grassroots movement, White Mesa Concerned Community, has emerged to resist the White Mesa Mill and its impact on the people, lands, and water of White Mesa. Led by White Mesa community members Thelma Whiskers and Yolanda Badback, White Mesa Concerned Community organized partners to put on an annual leadership and education academy to inform White Mesa youth about the mill. They also lead an annual spiritual walk from the community to the mill’s gates. This direct action and community organizing are coordinated with the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, whose environmental department supports logistics for the annual walk. White Mesa Concerned Community provides a grassroots counterpart to the Tribe’s uranium mill-related legal and administrative challenges.

The story of the White Mesa Mill is not an outlier but rather an example of a larger trend. Over the life of the Black Mesa coal mining complex on Navajo and Hopi lands that supplied the Mohave Generating Station, Peabody Western Coal Company used 44 billion gallons of pristine groundwater from the N-Aquifer to slurry coal from the mine to the power plant. Over time, dropping aquifer levels reduced spring discharge on the Navajo and Hopi reservations. At some monitored springs, this discharge reduction exceeded 50%.21 The drawdown has also potentially increased the concentration of contaminants in water sources. Since the Bureau of Indian Affairs first installed a drinking water system on the Hopi Reservation in the 1960s, the arsenic levels in water for eight Hopi villages exceeds Environmental Protection Agency safe-drinking water standards by as much as three times the allowable levels.22

Uranium development that began in the Atomic Era and continues has also been hugely harmful to tribal water resources across the Colorado Plateau. This is particularly true on the Navajo Nation and near Grand Canyon where mining activity continues today and threatens the blue-green waters of the Havasupai Nation. On the Navajo Nation, a 2017 study showed that arsenic and uranium concentrations exceeded national drinking water standards in 15.1 % (arsenic) and 12.8 % (uranium) of 464 unregulated water sources that scientists have tested for the last 25 years.23

Unregulated sources in close proximity to abandoned uranium mines yielded significantly higher concentrations of arsenic or uranium than more distant sources. This is particularly problematic because, due to the lack of infrastructure, 30% of families on the Navajo Nation haul water and often from unregulated sources.24

The issue of multi-national companies and federally-supported mining on the Colorado Plateau is deeply complex because, in some cases such as at Black Mesa, tribal governments themselves sanctioned the activity in exchange for economic benefit, albeit over the protests of numerous community members. In other cases, such as uranium mining during the Atomic Era, the federal government disseminated misinformation about the impacts of uranium mining and milling. This caused significant cancer clusters in tribal communities due to inadequate protection for miners and the contamination of groundwater due to milling activity.25 Grassroots and nonprofit groups emerged to bring attention to the impacts that they were seeing on the ground in their communities, such as culturally important springs drying up, streams no longer flowing, and sick community members. Once created, these groups pushed tribal and federal governments for different policies that protected both public health and the health of water resources. Even where water quality concerns related to mining are not an issue, the impact of non-Indian use of shared resources is significant, especially as Western populations grow.

Another challenge is water rights, just the ongoing efforts to secure our water rights and then protect them once we get them. Now, non-Zuni uses are impacting our uses. That continues to be an issue and especially in times of drought when there’s not a lot of water to begin with to go around for everyone….That’ll continue to be a challenge, especially with increased development….Today, you have a lot of rural subdivisions popping up – where you have people living in subdivided two, five, or 10 acre lots and needing a well, where there used to be huge tracks of land owned by ranchers and others doing minimal development and minimal water use for ranching, livestock grazing, or whatever other uses. But now with more and more people, each lot represents a potential well and even though the well might be small and used for its own domestic household purposes…if you have hundreds and hundreds of them and if they all tap the same aquifer that provides water to the spring, then you could still get the cumulative effect of one big well pumping a lot that could affect a spring.

– Kirk Bemis

Beyond water quality concerns, Tribes on the Colorado Plateau are still in the process of securing and accessing surface water resources for community use. Two U.S. Supreme Court cases created the legal doctrine of federal reserved rights that frame Tribal claims to water, incuding on the Colorado Plateau. In 1908, Winters v. United States established that every Indian reservation has implied rights to water sufficient to support the purpose of the reservation, rights now known as Winters rights.26 However, Indian nations do not automatically receive water flowing through pipes simply by virtue of the reservation’s existence. In order to obtain this “wet water,” a Tribe must either go through a protracted general stream adjudication or secure a negotiated settlement. In Arizona, the Navajo and Hopi Tribes are involved in the adjudication of the Little Colorado River. This process began in the late 1970s, currently involves 14,654 claimants, and is predicted to be in litigation for many more years.27 This is a typical timeframe for an adjudication involving Indian water rights.28

The difficulty of adjudicating water rights, including adjudication’s focus on consumptively used water and the subsequent challenge of obtaining legal recognition for the cultural values of water, leads many Tribes to turn toward negotiated settlements. In a settlement, the Tribe usually accepts a smaller quantity of water in exchange for water resource infrastructure, other economic assistance to manage water resources, waivers of liability, and other preconditions. While there are many advantages to negotiated settlements, non-Indian interests also have a seat at the negotiating table and their requirements are also accounted for in the settlements. Thus, settlement provisions designed to benefit state and federal parties often impose limits upon tribal use of water.29 Additionally, because Tribes are often the very last water users in a system to receive their wet water, they face the additional heavy burden of balancing the environmental and cultural needs of the natural world against the needs of their people – an issue that non-Indian communities who secured water earlier did not have to face.

Kirk Bemis, who has worked on water rights issues for the Zuni Tribe for several decades, provides perspective on this complexity:

I think just overall there needs to be more of a recognition by Tribes and others that water is not only critical for people but for nature and just the habitat and wildlife and just nature itself need to water for its own sake. And so in planning and water rights, there needs to be something set aside for that. And that can be challenging. And there may not be enough to go around and Tribes especially being behind a lot of mainstream development and catching up with things. Sometimes it’s a struggle for them to, to have to say, “Oh, there’s finally water and now we can finally get it as people. But we also need to remember to leave some behind it, preserve some nature.” And the Tribe is put in that terrible position of being the people to make that choice. Whereas people before us didn’t have to necessarily face that.

– Kirk Bemis

Notably, the Colorado Plateau is encompassed by the greater Colorado River Basin and here, as much as any river system in the West, natural flowing rivers have been altered by dam systems. For decades, state and federal interests have managed the River primarily as a water delivery system. Today, particularly as tribal water projects come online and add demand to an over-allocated system, Tribes are leading the way in integrating tribal traditional and cultural values into the complex web of policies and planning processes that make up the Law of the River.30 This can be seen, perhaps most notably, in the growing leadership role that the Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes PartnershipIV plays in water management negotiations and discussions in the greater Colorado River Basin. In 2018, in partnership with the Bureau of Reclamation, the Ten Tribes Partnership released “The Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study Report,” which documents how the member Tribes currently use their water, projects how future water development could occur, describes water development challenges and opportunities, and articluates the potential effects of tribal water development on the Colorado River system. The report also includes powerful statements from each Tribe’s individual perspective about the cultural values of water.31

Finally, climate change also increases pressure on scarce water resources. The seasonality of precipitation is changing with rain falling more often in colder months instead of snow, less precipitation overall, and snowmelt runoff occurring earlier.32

Ceremonies that Native people have always performed are timed with the seasons, and the disruption to the climate also impacts these ceremonies. Additionally, cultural tension can exist around anticipating, predicting, or planning for climate impacts.

Climate change presents cultural challenges as well, in addition to all the practical reasons. Philosophically, it’s something that similar to drought and floods. Zuni has a taboo about talking or predicting bad things that can happen, especially when it comes to natural disasters. So sometimes planning and preparing for droughts or floods can be challenging to say things the right way and not insult people’s mindsets, talking as if it will happen and, therefore, willing it to happen. Predicting it. And climate change can be similar, especially with respect to the water and the rain and predictions from forecasters. And then the Zuni’s belief in what their practices are about. And the idea there is that if climate change models say that the Zuni area will not receive as much precipitation in the future, then somehow stating that is bad. For a lot of traditional Zuni to be hearing that, it’s like being told that practicing your faith will not work as well in the future because it won’t bring as much rain. It’s almost like being told that you’re just not going to be able to do what you used to with your belief system. So, that can be a challenge to speak in those terms and be careful about, talking in those ways.

– Kirk Bemis

Water, in all its forms, remains a cultural touchstone for Native Tribes across the Colorado Plateau. Native leadership to protect culturally important water resources will only grow as climate impacts and western populations increase. The ongoing work to heal landscapes and waters devastated by mining, and to prevent future impacts from new extractive industry operations, will continue for generations to come. Simultaneously Tribes will work to secure safe, piped, drinking water for their tribal members by advancing large water projects, which will place additional pressure on the overallocated Colorado River system. Negotiating these tensions and finding a path forward that both advances the human right to safe drinking water and safeguards cultural values will require strong leadership from Native people across the Colorado Plateau.