GATES TO THE PAST

LOVE AND LEGENDS: UNVEILING THE ROMANCE OF THE HANGING GARDENS 2

LOVE AND LEGENDS: UNRAVELLING THE ROMANCE OF THE HANGING GARDENS OF BABYLON

BY CHI-CHI NWABU-NWOSUthe dusty annals of antiquity, few monuments have captured the imagination quite like the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Shrouded in mystery and extravagant lore, this lush paradise is said to have been an extraordinary labor of love, commissioned in the 6th century BCE by King Nebuchadnezzar II to replicate the idyllic mountain scenery of his homesick wife Amytis’ homeland and soothe her longing for natural splendor amidst the sun-baked Mesopotamian plains.1

Although the romantic origin tale of the Gardens has ensured its enduring mystique over millennia, recent scholarship suggests their significance ran far deeper; daring to tap

deeper into the rich ceremonial traditions and erotic mythologies surrounding love, sex, and marriage in ancient Mesopotamian civilization. Beyond a private indulgence for one queen’s exotic tastes, this breathtaking monument appears to have embodied an entire culture’s intertwined obsessions with desire, fecundity, and the intoxicating power of human and divine passion.

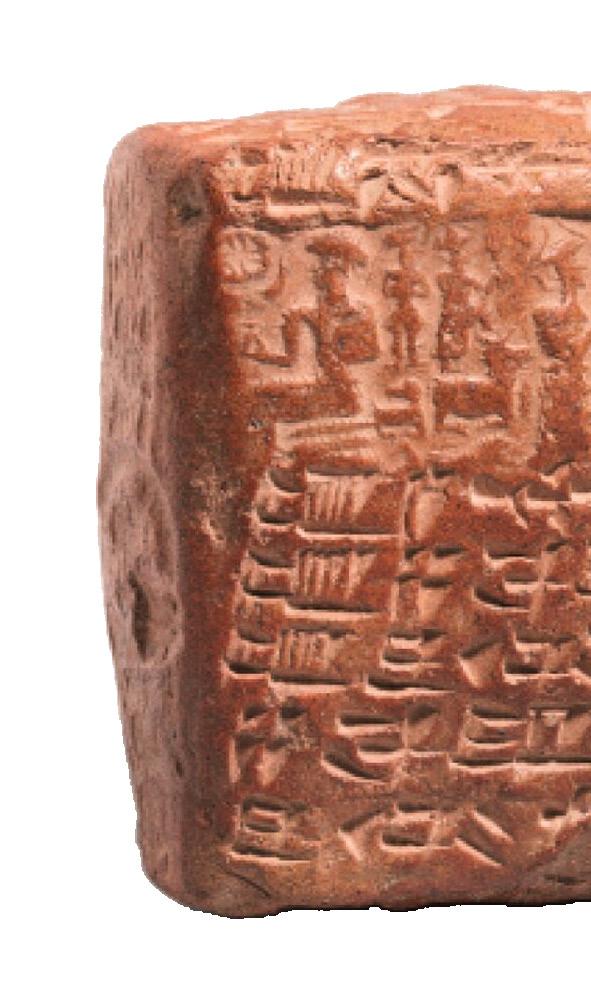

The old love poems written in cuneiform (a script of ancient Mesopotamia) vividly show how romantic feelings were linked with the beautiful garden imagery. One poem says, “You have captivated me, let me

stand tremblingly before you. Bridegroom, I would be taken by you to the bedchamber,”1, such erotic lyricism suggests how the Hanging Gardens might have been seen as a place of love and desire, full of passion and longing.

Did you know?

Nebuchadnezzar actually had a longer name in Chaldean: Nabu-kudurru-usur, meaning “Nabu, Preserve My First-Born Son.” It’s believed that the Israelites of Canaan knew him by the name Nebuchadnezzar, derived from the Akkadian ‘Nebuchadrezzar’.

These feelings of love and desire becomes even more meaningful when we think about how closely the Gardens were connected to Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, beauty, sex and fertility who was widely worshipped across ancient Mesopotamia. One cuneiform text depicts her realm as a paradise overflowing with “lush gardens...date-clusters and reeds arched over the plants.”2

This description sounds a lot like the impressive Hanging Gardens we’ve heard about. It seems like the Gardens were seen as an earthly manifestation of Inanna’s mythic domain - a place where love, beauty, and nature all came together in a magical way. Archaeological discoveries add depth to this idea of this sensual and romantic idea of the Hanging Gardens. In ancient Mesopotamia, people used to decorate their bedroom walls and ceilings with frescos of gardens, thus mixing human intimacy with symbols of love and fertility. “These lush murals created an atmosphere that felt almost magical, blurring the lines between earthly pleasures and spiritual beliefs. These artworks were meant to help couples experience a deeper connection, almost like entering a mythical realm together. The grandeur of the Hanging Gardens might have served a similar purpose, allowing visitors to feel as if they were stepping into a world reminiscent of the goddess Inanna’s legendary paradise, overflowing with love and abundance.

Did you know? In Babylon, the bride brought with her a dowry called “sherigtu,” which remained the property of her children and could not be claimed by her husband’s brothers. Additionally, she might receive a marriage jointure, which remained her property even in the event of divorce.

Archaeological discoveries of ancient writings and artifacts, show how love, desire, and sacred marriage ceremonies were deeply rooted in Mesopotamian society. One distinct example can be seen in The Sacred Marriage ceremony. The sacred marriage, or

hieros gamos, was a religious ceremony that reenacted the divine union of the fertility deities Inanna (Ishtar) and Dumuzi (Tammuz). As Samuel Noah Kramer elucidates, “To make his people happy, prosperous, and teeming in multitude - there was no fear of a ‘population explosion’ in those olden golden days - it was the king’s pleasant duty to marry the passionate, desirable goddess of fertility and fecundity, the alluring deity who controlled the productivity of the land and the fruitfulness of the womb of man and beast.”1 This ceremony symbolized the renewal of fertility in the land and the con tinuity of the cycle of life.

Although this ritual holds a primarily agricultural significance, it was also associated with love and romance, intertwining with the delicate threads of affec tion and longing. Inanna radiated as a captivating and alluring figure within Mesopotamian mythology. Through this ritual, worshippers sought the benevolent blessings of these deities, invoking prosperity across human, animal, and agricultural domains. The very myth of the sacred marriage echoed with resonant chords of love and desire, portraying a divine union pulsating with elements of longing and devotion.

This reverence for ecstatic intimacy permeated all aspects of marital customs and partnerships in ancient Mesopotamia, as the veneration of such intimacy wove seamlessly through unions. The personal depth of romantic longing is palpable, captured poetically in lines like “When you speak to me, you make my heart swell till I could die!”2. Beyond the

pragmatic bonds of property and progeny, these heartfelt sentiments spoke to a deeper, more profound reality. While pragmatic concerns like property exchange and producing heirs shaped many unions, such heartfelt sentiments attest to far more than just contractual realities. Tokens of romantic love, depictions of lavish wedding feasts brimming with sensual symbolism and courtship scenes adorning murals and carved reliefs – all underscore the vital affectionate and erotic tenor infusing spousal relationships.

FROM KÜLTEPE-KANESHE, TURKEY.

Undoubtedly, while pragmatic concerns undeniably influenced numerous unions, romantic love emerged as a transcendent force, heralding a transformative and even mystical state. Esteemed scholar A. Leo Oppenheim astutely noted, “The contractual nature of Mesopotamian marriages did not preclude deeply personal dimensions. Love poetry and art reveal an undercurrent of sacred eroticism interwoven with earthly marital rites.”1. This perspective underscores the powerful valorization of romantic love within ancient Mesopotamian culture, transcending the mundane pragmatism often associated with marital arrangements.

Nowhere did this transcendent yearning for mythical unity find clearer expression than in the eternal promise of the Hanging Gardens. With lush vegetation cascading in terraced abundance, exotic scents perfuming the air, and shimmering waterworks breathing life into the landscape, the Gardens conjured an immersive ecstasy, blurring the boundaries between earthly and celestial realms. A lush, verdant paradise cascading in terraced abundance, ex1

More Fun facts about King Nebuchadnezzar II!

otic fragrances perfuming the air, shimmering waterworks conjuring the very essence of life itself – the Gardens created an ecstatic immersive experience blurring earthly and celestial realms. Like the intoxicating fragrance of their blooms, believed to possess healing properties, the Gardens embodied an antidote to the melancholic longings and mortal separateness of humanity. By symbolically evoking Inanna’s mythic paradise overflowing with sensual plenty, the Gardens offered a multi-sensory gateway into divinely ecstatic states of cosmic unity and regeneration.

He was a formidable military leader who successfully invaded and conquered the Kingdom of Judah, leading to the Babylonian Captivity, during which many Jews were exiled to Babylon.

Nebuchadnezzar II, as part of his building projects, reconstructed the great ziggurat known as Etemenanki (“the foundation of heaven and earth”), which had been destroyed by the Assyrian king Sennacherib. This monumental structure is thought to be the inspiration for the biblical Tower of Babel.[?]

For the lovesick Amytis, this grand creation likely stood as the ultimate romantic apotheosis—an earthly manifestation of her cherished homeland transformed into an eternal mystic idyll. Rath er than languishing in the grip of nostalgia, her primal desires found myth ic, transcendent resolution through this symbolic naturalistic consumma tion. The Hanging Gar dens materialized human love’s highest dream of sacred wholeness and abundance by

The Babylonian ‘s had advanced knowledge of mathematics, particularly in the field of geometry. Their mathematicians used a base-60 numeral system, which allowed them to make complex calculations and measurements with remarkable accuracy. They were able to calculate areas of geometric shapes, solve quadratic equations, and even develop methods for calculating the volume of irregular objects. Their mathematical achievements were far ahead of their time and laid the foundation for later mathematical advancements in civilizations such as Ancient Greece!

symbolically fusing with the regenerative cycles of the cosmos itself.

Within the mythopoetic tapestry of ancient Mesopotamian culture, there existed no rigid boundaries between the sensual and celestial, the physical and, philosophical realms. The visceral, earthy realities of romantic love, marriage, and human sexuality were perceived as intimate cosmic resonances —mirroring the mytopoetic tapestry of ancient Mesopotamian culture, there existed no rigid boundaries between the sensual and celestial, the physical and philosophical. The raw, earthy realities of romantic love, marriage, and human sexuality resonated as intimate cosmic harmonies, reflecting the mythic dramas of the gods and participating in their fertile vitality. For the ancient Mesopotamians steeped in this mythopoetic cultural milieu, there existed no rigid separation between the sensual and celestial, physical and philosophical realms.

The visceral, earthy realities of romantic love, marriage, and human sexuality were perceived as intimate cosmic resonances— mirroring the deities’ own mythic dramas and participating in their fertilizing vitality. This syncretic perspective viewed the most carnal of human experiences as resonant with the divine, the biological impulses imbued with mythic significance.

This syncretic worldview finds affirmation in the scholarship of luminaries like Mark

Cartwright, whose exploration and overview of the legendary monument illuminate its deeper symbolic dimensions. “The notion of recreating an idyllic, fertile, mountainous landscape mirrored the Mesopotamian fascination with themes of regeneration, fecundity, and abundance embodied in mythological garden paradise imagery,” Cartwright explains. “It merged human ambition with spiritual yearning, manifesting a lush temple to the agricultural deities.”1 Through Cartwright’s insights, we grasp how the Hanging Gardens epitomized the blending of mortal aspirations with celestial ideals, serving as a testament to humanity’s deepest longings and the divine mysteries of creation.

Thus, the Hanging Gardens emerge as the ultimate fusion of human and celestial planes—a lush, breathtaking mortal ode to our species’ most primordial yearnings. “The loftiest ideals of romantic love transmuted into promise. In the quiet depths of our being, the Gardens whisper, reminding us of an Edenic a mythic spectacle, carnal desire transfigured through symbolic communion with the generative energies of the divine,”2 elucidates the narrative.

It is an alchemical vision, uniting the microcosm with the macrocosm in a lush evocation of Paradise’s life-affirming bounty. In this light, the Gardens shine as a quintessential synthesis of mortal aspirations and celestial ideals, offering a verdant testament to humanity’s deepest longings and the divine mysteries of creation.

Small wonder, then, that the legend of the Hanging Gardens endures as an oasis in

the desert of our collective imagination—an icon of love’s redemptive power, capable of healing the wildernesses of the soul and revealing fleeting glimpses of paradise’s lush state where human and divine love converge in sacred plenitude, as expressed by the eternal harmony of the natural world and the divine.