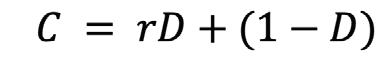

Figure 1: Lag Selection AIC Graph

About the Author

Kate D’Amato is a senior in the Honors Program at Christopher Newport University, where she is pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in Mathematical Economics with a minor in Business Administration. Maintaining a 4.0 GPA, she is set to graduate in December 2025. Since Fall 2022, Kate has worked as a research assistant for the Economics Department. She has been awarded three independent research grants for projects exploring economic issues, including pandemic policy impacts and infation. Her most recent grant-supported project directly inspired this paper on the efects of public debt on economic output in Italy and Japan. Kate previously served as Executive Vice President of the Student Government Association and has held several leadership positions including president of Alpha Chi and Students for Women’s Rights. Her academic research at CNU has shaped her career path in data analysis, and she will further pursue this interest as an Innovation and Strategy Intern at the American Bankers Association during the summer of 2025.

Te Role of Religion in Political Power: An Analysis of Teocratic Governance in Iran

Jaya Daniel

Faculty Sponsor: Dr. Jay Paul, Honors Program

Abstract

Teocratic governance in Iran, rooted in the fusion of religious authority and political power, has proven fundamentally incompatible with modern political, social, and economic development. From the Safavid Dynasty through the post-1979 Islamic Republic, Shi’ite religious institutions have shaped national identity, law, and state legitimacy. Key turning points such as the Constitutional Revolution, Reza Shah’s secular reforms, Mossadegh’s coalition government, and Khomeini’s rise highlight recurring tensions between secular nationalism and clerical dominance. Trough the lens of compensatory control, religious governance provides psychological order during periods of instability, yet this strategy conceals deep structural weaknesses. Centralized clerical power, exclusionary policies, and economic mismanagement have fueled public disillusionment and resistance. Tese internal pressures, combined with Iran’s regional infuence and authoritarian model, present signifcant challenges not only within the country but also for global stability and human rights.

Compensatory control refers to the psychological mechanisms individuals employ to restore a sense of order and predictability when they experience a loss of personal power. According to social psychologists Kay et al. (2009), in the face of uncertainty, people may engage in behaviors such as perceiving patterns in randomness, reinforcing belief in sociopolitical institutions, or relying on faith in an “interventionist god”: a deity believed to actively intervene in human afairs to guide and protect them. Tese responses help individuals manage their existential fears and maintain a sense of agency. Understanding how these processes operate enhances insight into various social phenomena, such as prejudice, radicalization, and the rituals that unite communities during times of crisis (Kay et al., 2009).

Tis psychological framework ofers a valuable lens through which to understand the intersection of religion and political power. Religion, particularly when intertwined with political authority, often plays a central role in such compensatory mechanisms by providing a framework for stability and certainty (Kay et al., 2009). In societies where secular governance struggles, religious authority can emerge as a dominant source of legitimacy. Tis paper will examine the role of religious authority in shaping governance in Iran and explore how theocratic rule, grounded in Islamic principles, has impacted laws, social structures, and state legitimacy. While theocratic rule in Iran emerged from historical and theological roots, it proves incompatible with the demands of modern governance. Iran’s centralization of power within a clerical elite suppresses pluralism, while exclusionary policies deny political participation to vast segments of the population. Tese practices not only erode institutional efciency but also deepen social divisions, fueling widespread disillusionment and resistance.

Historical Roots of Teocracy

According to Houchang Chehabi, professor at Harvard University, throughout history, most societies have typically maintained a distinction between spiritual and temporal authorities. However, when this separation ceases and a religious institution assumes rule over both spiritual and temporal matters, the resulting political system is referred to as a theocracy (Chehabi, 1991). In the purest form, “God is recognized as the immediate ruler, and his laws are taken as the legal code of the community and are expounded and administered by holy men as his agents,” as political scientist Vernon Bogdanor argues (Bogdanor, 1987). In Iran, this theocratic model has been frmly entrenched since the 1979 revolution, with the clergy playing a central role in governance, policy, and political authority, shaping domestic policies and the nation’s relationship with the outside world.

Safavid Dynasty

Tis theocratic infuence began in 1502 when a powerful clergy emerged, and the Safavid Dynasty declared Shi’ism as the dominant sect of Islamic Persia (present-day Iran), forming a strong centralized state. Te solidifcation of Shi’ism as the state religion and the integration of religious authority into their political structure created a dual system where religion and politics were intertwined. Tis system allowed the clergy to play a substantial role in governance, with religious leaders helping to shape laws and policies. Over time, the Safavid model of blending religious authority with political rule laid the groundwork for the clergy’s enduring infuence on Iran’s political landscape (Chehabi, 1991). However, Chehabi notes that “to understand the political involvement of the clergy in contemporary Iran, one has to keep in mind that it does not constitute a church in the sociological sense” (Chehabi, 1991). Additionally, there is no strict clerical hierarchy, with Shi’ites claiming that “the order of the clerical hierarchy is disorder,” meaning the clergy does not dominate all areas of religious activity (Chehabi, 1991). Tis structural complexity, paired with broader systemic challenges, contributed to the fall of the Safavid Dynasty in 1722,

resulting from a combination of internal instability, economic decline, and external threats.

John Foran of the International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies explores the rule of Shah Abbas I, also known as Abbas the Great, who ruled the Safavid Empire from 1588 to 1629 and is regarded as one of the most signifcant monarchs in Iranian history. After his death, the empire began to experience weakened leadership and growing internal turmoil (Foran, 1992). Te fall of the Safavid dynasty illustrates the inability of its theocratic system to adapt to changing political, economic, and ideological realities. As the religious foundation of the state weakened, the rulers failed to ofer a new unifying ideology, contributing to further instability (Foran, 1992). Further, renowned theologian Mohammad Fazlhashemi explains that the collapse of the Safavids marked the end of the most infuential dynasties in Iranian history, disrupting the establishment of the Twelver Shia Islam as the state religion. Twelver Shia Islam, also known as Imamiyya, is centered on the belief in twelve divinely designated Imams, starting with Ali, the Prophet Muhammad’s cousin, and ending with the twelfth, Muhammad Al-Mahdi, who is believed to return as a messianic fgure to restore justice and defeat evil. Te belief in the Imams’ divine authority and their role in governance remained foundational to Iranian political and religious life, even after the fall of the Safavids (Fazlhashemi, 2021). Te entanglement of religion and political authority as a source of legitimacy in Iran refects a legacy that, while historically signifcant, obstructs the evolution of a more pluralistic and accountable political system.

Constitutional Revolution of 1906

According to Vanessa Martin, a historian for the Royal Holloway, the 1906 Constitutional Revolution was a monumental movement that sought to curb the monarchy’s rule and lay the foundations for representative government in Iran. It emerged in response to widespread dissatisfaction with Shah Mohammad Ali’s absolutist rule and growing foreign infuence, sparking demands for democratic reforms, including a parliamentary system and a bill of rights. Te movement successfully established the frst Iranian Constitution in 1906, which created the Majles (national assembly) and guaranteed certain civil liberties. However, despite initial successes, the revolution faced strong resistance from conservative factions and international stakeholders, undermining many of its early achievements (Martin, 2011). While demands for political reform drove the revolution, it also revealed deep opposition surrounding the role of religion in governance, particularly through the involvement of the Shi’ite clergy.

Shi’ite religious beliefs in Iran played a prominent role in shaping the Constitutional Revolution, particularly through the infuence of the ‘ulama (religious scholars). Under the Shah’s absolutist rule, legitimacy and justice were derived from Islamic law as interpreted by the ‘ulama. Some clerics supported the constitutional movement because they believed it would restrain the Shah’s power and protect Islamic values. Te clergy actively advocated for the reforms, though not all agreed. Others feared the revolution would bring excessive Western infuence and weaken religious authority. Following the revolution, a shift toward secularism prompted many clerics to withdraw from direct political involvement. For context, secularism is “the belief that religion should not be involved with the ordinary social and political activities of a country” (Cambridge, 2025). Tis division between religious tradition and political reform played a pivotal role in shaping the revolution’s long-term outcomes (Martin, 2011).

Reza Shah Pahlavi and the

Secularization of Iran

Following the 1906 Constitutional Revolution and the subsequent shift towards secularism, Iran’s political landscape transformed with Reza Shah Pahlavi’s political ascent in 1925. Pahlavi pursued modernization through reforms that reduced clerical infuence, centralized authority, and promoted a secular national identity (Chehabi, 1991). According to Faegheh Shirazi, a specialist in Islamic Studies at the University of Texas, Raza Shah’s

policies, such as the compulsory unveiling of women and the establishment of a secular legal system, further deepened the divide between religion and politics in Iran. Tese policies were designed to transform Iran into a modern, centralized nation-state aligned with Western governance models. Still, they increased polarization between secular and religious factions (Shirazi, 2019). Many viewed this policy as a rejection of traditional Islamic values and a challenge to the authority of the religious establishment. Te clerics, who had historically held control in shaping Iran’s social and political fabric, viewed the unveiling as a direct threat to their infuence. Tis fueled widespread opposition among religious communities and escalated volatility crucial in the political upheavals leading to the Islamic Revolution in 1979 (Shirazi, 2019). In response to Reza Shah’s secularization eforts, many clerics and religious leaders began to unite against the perceived erosion of Islamic principles in governance, paving the way for the eventual rise of theocratic ideologies in Iran (Shirazi, 2019).

Reza Shah’s abdication during World War II ushered in a period of instability that led to a revival of competitive politics in Iran. Tis postwar period brought renewed interaction between traditional clerical politics and secular nationalist movements (Shirazi, 2019). Notable political fgures, such as Ayatollah Abolqasem Kashani, became infuential advocates for religious leaders’ involvement in national afairs. Mohammed Mossadegh, another key fgure, led the nationalization movement of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. His government represented a coalition of both secular nationalists and religious forces. However, this temporary alliance exposed underlying tensions between secular nationalism and clerical authority, foreshadowing future political conficts in Iran (Shirazi, 2019). Te fallout from Mossadegh’s tenure and his eventual overthrow in a coup backed by Western powers ushered in the strengthened reign of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (Shirazi, 2019). Tis shift demonstrated the fragile and often uneasy alliance between modernist reforms and the enduring infuence of religious leaders, revealing once again the challenges of balancing secular governance with theocratic authority. Amid the deepening divide, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini emerged as a central fgure determined to restore Islamic infuence in Iranian leadership.

Political Evolution and Resistance

Khomeini’s

Rise

According to Mahdi Khalaji (2011), a senior fellow at Te Washington Institute for Near East Policy and a trained Shi’a cleric for Iran, Khomeini began political activism in the late 1940s, advocating for clerical oversight of the government and greater involvement of religious authorities in political afairs. His writings and speeches increasingly criticized the Shah’s regime and its Western ties, which he viewed as harmful to Iran’s sovereignty and Islamic identity. Te growing opposition culminated in the 1963 attack on the Qum seminaries, where government forces violently suppressed protesting clerics and students. As Khomeini’s resistance to the Shah intensifed, he was exiled in 1964 but continued to rally support abroad, using religious rhetoric to unite the masses and frame the political struggle as a battle between Islam and secularism, which set the stage for the 1979 Iranian Revolution (Khalaji, 2011).

Iranian Revolution

Te Iranian Revolution marked the culmination of widespread dissent against the Shah’s authoritarian regime, leading to the establishment of the Islamic Republic. As the revolution unfolded, Khomeini emerged as the leading fgure, temporarily uniting religious and secular factions. Yet, the revolution also exposed deep ideological divisions between secularists and extremist factions within the clergy, complicating eforts to establish a stable political order. Khomeini’s anti-Shah rhetoric framed the Shah’s regime as an illegitimate

puppet of Western nations, galvanizing public support for the revolutionary cause (Khalaji, 2011).

After the establishment of the Islamic Republic, a new constitution was drafted to combine religious authority with the will of the people, giving the clergy a key role in governing. However, the new government faced difculties as it tried to strengthen its potency using religious principles while dealing with the challenges of governing and applying Islamic law to the state (Khalaji, 2011). Te consolidation of clerical might lead to an intertwining of state and religion, forming the foundation of Iran’s distinct model of religious authoritarianism. Over time, the clerical establishment, which was initially positioned as “agents of revolutionary change,” became increasingly subservient to the state it had helped create (Khalaji, 2011). Tis shift led to a regime-dominated political landscape, where religion became a symbolic capital that could be exploited for political ends. Within this framework, the clerics faced diminishing prestige and authority as the regime’s ideological grip extended over societal institutions, shaping public life and suppressing dissent. As the state consolidated its authority, it restricted the clergy’s ability to operate independently, undermining their historical role as moral and political advocates (Khalaji, 2011).

Tis dynamic soured the relationship between the ruling elite and segments of the clerical establishment, complicating the regime’s legitimacy. Tis led to rising public discontent, refected in declining mosque attendance and growing support for secular values among the Iranian populace (Khalaji, 2011). Tese tensions between state and clerical interests foreshadowed future challenges for the Islamic Republic, raising doubts about the long-term viability of a regime dependent on religious capital while confronting an increasingly resistant society demanding greater freedoms. Despite the revolution’s initial idealism, Iran’s evolving political landscape revealed the inherent friction in merging Islamic principles with modern governance, resulting in a complex and often contentious political reality (Khalaji, 2011). What began as clerical empowerment gradually evolved into a regime-controlled religious establishment, where symbolic authority replaced independent moral leadership.

Post-Revolutionary Teocracy and Political Challenges

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran has operated under a theocratic political system that fundamentally transformed the nation’s governance. At the helm of this new order is the concept of Velayat-e-Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), which grants ultimate authority to the Supreme Leader, a role frst flled by Ayatollah Khomeini and later by his successors. Tis system places clerical authority above democratic principles, concentrating power in the hands of religious elites, particularly the clergy (Golkar, 2016). Political scientist Saeid Golkar (2016) explains that “the clergy seized rule of Iran and its political machinery, efectively transforming itself into the most prominent group of political elites in the state.” Tis theocratic structure has sidelined secular political actors, emphasizing ideological commitment over technical expertise in the political elite. Many civil servants, for instance, are chosen based on their “taahhod” (ideological loyalty) rather than their “takhasoos” (technical skills) (Golkar, 2016).

According to Ray Takeyh, a former advisor to the U.S. State Department on Iran, this consolidation of clerical energy became even more pronounced in the decades following the revolution as Iran navigated a series of political and economic crises, reinforcing the regime’s reliance on religious authority. Te Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) played a pivotal role in legitimizing the theocratic government, as the confict was framed as both a national defense and a religious duty, allowing the Supreme Leader to tighten control under the guise of wartime necessity (Takeyh, 2009). Further, as historian Efraim Karsh (1990)

explains, the war also fostered a siege mentality, which allowed the clerical establishment to suppress internal dissent while justifying mass political purges. As the war concluded, the regime leveraged its newfound legitimacy to entrench its command further, systematically eliminating political opposition and consolidating command over key institutions (Karsh, 1990). For example, Khomeini issued a religious edict (fatwa) ordering Muslims to kill British author Salman Rushdie for his novel, Te Satanic Verses, which was “considered blasphemous to Islam” (BBC News, 2020). Te post-war period saw the expansion of Iran’s security apparatus, with organizations such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Basij militia playing a role in reinforcing state authority and enforcing ideological conformity. Te war’s aftermath also deepened socioeconomic divides, as veterans and loyalists were rewarded with government positions and economic privileges, while political dissidents and marginalized groups faced increased surveillance and repression (Golkar, 2016). Haleh Afshar, one of the frst Muslim women appointed to the U.K. House of Lords, notes that this period witnessed the rise of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Khamenei succeeded Khomeini in 1989, further reinforcing the centralization of power within the religious establishment. Khamenei, lacking the charismatic authority of his predecessor, relied heavily on the IRGC and conservative clerics to solidify his rule, leading to an increased militarization of Iranian politics and further suppression of reformist elements (Afshar, 1995).

Troughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Iran experienced a struggle between reformist and conservative factions, as President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) sought to expand civil liberties and improve relations with the West. However, according to German political analyst Wilfred Buchta, his eforts were repeatedly blocked by Iran’s unelected institutions, particularly the Guardian Council, which ensured that the supreme leader and clerics tightened hegemony over the political system (Buchta, 2004). Te election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005 signaled a shift back to hardline conservative rule, characterized by intensifed anti-Western rhetoric and a renewed focus on Iran’s nuclear program, which triggered international sanctions and economic struggles. Tis return to conservative leadership set the stage for growing internal unrest, as public dissatisfaction with the regime’s policies began to surface more openly. Peter Whittaker, journalist for the New Internationalist, noted that the 2009 presidential election and protests, known as the Green Movement, posed one of the most signifcant challenges to the regime. Still, it was violently repressed, reinforcing the government’s reliance on authoritarian measures to cement elite dominance (Whittaker, 2011). Sparked by allegations of electoral fraud, the movement mobilized millions demanding democratic reforms, only to be crushed by security forces through mass arrests, censorship, and violence. Tough unsuccessful, the movement exposed deep societal hostility and paved the way for counterprotests against the regime (Whittaker, 2011). In the following decade, economic instability and social unrest continued to grow. Tis culminated in more mass protests, such as those sparked by the 2022 death of Mahsa Amnini. Amnini, a woman from Iran’s oppressed Kurdish minority, was stopped by Iran’s police, who routinely detain women for not complying with the country’s religious codes, including compulsory veiling laws, which she was accused of violating. She was beaten to death while in custody (Amnesty International, 2022). Her death reignited concerns about the regime’s repressive policies and the long-term viability of Iran’s theocratic rule. Tese renewed concerns over state repression have drawn fresh attention to the structural foundations of Iran’s theocratic system and how centralized religious authority sustains it.

Structural Challenges of Teocratic Rule

Centralization of Power

Religious rule depends on centralizing power, allowing a governing body to assert ideological sovereignty over political and social life. Unlike secular democratic institutions, which encourage diversity and the dispersion of regency, religious regimes often consolidate decision-making within a clerical hierarchy, limiting political participation to those who align with its ideology. In Iran, this centralization is evident in the role of the Supreme Leader, whose command supersedes all other political institutions, including the elected president. Iran’s Guardian Council further enforces this centralization by vetting candidates for political ofce, ensuring that only those loyal to theocratic principles can run for positions of power (Golkar, 2016). Tis centralization not only suppresses opposition but also shifts political discourse from debates over policy and governance to moral and theological legitimacy. As secular institutions weaken, religious institutions become the primary spaces for political engagement, reinforcing a system where dissent is cast as heresy rather than political opposition. Tis is exemplifed in the Iranian system, where protests and reformist movements are often violently suppressed, and political opposition is framed as a threat to Islam itself (Khalaji, 2011). Tis transformation narrows the scope of political agency, making alternative ideologies less viable and perpetuating a system in which centralized religious sanction is asserted through institutional rule and ideological dominance.

Exclusionary

Policies

Exclusionary policies in Iran have been signifcantly shaped by the establishment of a theocratic regime following the Islamic Revolution. Under theocratic rule, religious identity became a crucial determinant of one’s political and social rights, creating a system where individual beliefs were not just a matter of personal choice but a determining factor for access to government positions and freedoms. According to Kazemipur and Rezaei of the Journal for the Scientifc Study of Religion, “Having a job in government and enjoying the freedom of expression are not rights but privileges, the benefciaries of which should be determined based on their beliefs about religion” (Kazemipur and Rezaei, 2003). Further, Kazemipur and Rezaei also explain that individuals who do not adhere to the prescribed religious norms, such as atheists, are excluded from holding governmental roles, delivering public lectures, or publishing ideas. Tese exclusionary measures refect the deep intertwining of religion and state power in Iran, where religious loyalty becomes a requirement for participating in the public sphere. Tis dynamic illustrates how faith-based governance can institutionalize exclusion, systematically denying political rights to nonconforming individuals in favor of reinforcing the prestige of the religious establishment. Deepening Social Divisions and the Struggle for Reform

Mansoor Moaddel, a prominent Iranian American sociologist, further agrees that the theocratic nature of Iran’s political system has intensifed ideological rifts and fueled a complex and ongoing struggle for reform. Initially, the revolution’s triumph granted a dominant role to the “masses,” including a broad coalition of workers, low-ranking bureaucrats, and other marginalized groups that had opposed the Shah’s regime (Moaddel, 1991). Tis emphasis on social justice rhetoric was central to the early years of the Islamic Republic, as it aimed to empower those who had long been excluded from political reign (Moaddel, 1991). However, UCLA sociologist Kevan Harris states that while the revolution promised unity, this idealism gradually unraveled as fractures emerged within Iranian society. Sidelined during the revolution, the middle class rose to infuence in the 1990s through its technical expertise and role in post-war economic reconstruction, marking a transformation in Iran’s political landscape, where the initial focus on the masses “was eclipsed by the growing infuence of the middle class” (Harris, 2015).

However, Iran’s cohesive middle class is an illusion. As both Moaddel (1991) and Harris (2015) argue, it is deeply fragmented, composed of groups with divergent social, economic, and political interests that hinder the development of a unifed political agenda. Tis internal division is evident in the emergence of conservative and reformist factions, each pushing for diferent versions of Iran’s future (Harris, 2015). Tese competing interests, spanning the masses, the middle class, and the state, have aggravated societal polarization in Iran and made the reform process even more contentious. Te resulting friction illustrates the challenges of balancing revolutionary ideals with the demands of a modern society, where the theocratic state is forced to address its historical legacy and the aspirations of a diverse and increasingly disillusioned population (Moaddel, 1991; Harris, 2025).

Compensatory Control

Trough the lens of compensatory control theory, the enduring strength of Iran’s theocratic regime can be recognized as a response to widespread feelings of uncertainty and sociopolitical fragmentation. In Iran, religion-driven governance provides a tool for the state to preserve command, particularly during unrest or social discontent. Integrating religious belief into governance ofers the populace a sense of order amid economic hardship, political repression, and societal splintering. Roxanne Varzi, an anthropologist of Duke University, notes that this psychological comfort is reinforced through state-sponsored rituals, such as annual Ashura commemorations, where the narrative of martyrdom and sacrifce inspires unity and obedience to religious authority. Tese public displays of grief and solidarity frame the regime’s rule as a moral continuation of Islamic residence, ofering a sense of cosmic order amid real-world instability (Varzi, 2006). Te state, in turn, uses this religious framework to suppress dissent, framing its actions as divinely ordained. Tus, compensatory control explains the appeal of theocratic governance and illustrates how such a system can persist by ofering a perceived solution to the uncertainty and anxiety inherent in a volatile political and social environment. While compensatory control helps explain the resilience of theocratic structures, a closer analysis reveals the system’s long-term unsustainability.

Argument

Teocratic rule, as exemplifed by Iran’s government, is fundamentally incompatible with modern political, social, and economic progress. By fusing religious authority with state authority, Iran’s leadership has created a rigid system that prioritizes ideological purity over competence, political dominance over democratic participation, and suppression over progress. Such a model is not only oppressive but inherently unsustainable. Tis rigid preference for ideological purity is evident in appointing key ofcials with religious credentials but minimal policy expertise, undermining institutional efciency. Tis has afected the health and energy sectors, where technical shortcomings have hindered modernization and stifed innovation. Consolidating power within a clerical elite has eliminated the diversity of thought necessary for efective governance, leading to underperformance, corruption, and systemic stagnation. Further, exclusionary policies that tie political rights to religious adherence directly undermine the principles of equality, barring millions from meaningful participation in society due to their personal beliefs. Tis is not merely amoral; it is a strategic blunder that weakens Iran’s economy and alienates a growing, disillusioned population.

Te regime’s use of religious legitimacy as a political instrument reinforces authoritarianism, using faith as a shield against scrutiny and dissent. Tis dynamic creates what Mario Ferrero, professor at the University of Eastern Piedmont, identifes as a “hidden information problem” within the governance structure, where a lack of transparency and

accountability allows abuse of power to go unchecked (Ferrero, 2013, p. 2). Moreover, historical precedent suggests that no regime can indefnitely suppress a population seeking change. Te desire for political freedom, social progress, and economic opportunity is intrinsic to human societies, and over time, oppressive systems breed resistance. Ferrero notes that the potential for internal confict among elite factions further contributes to the disintegration of efective governance, as seen in historical cases like the Hasmonean period in ancient Israel, the Papal states, the Buddhist theocracies of Central Asia, and even in Tibet under the Dalai Lama, where clerical confict undermined stability (Ferrero, 2013). Coercion and state-sanctioned violence do not eliminate dissent; they intensify resentment and sow the seeds of future revolt. Iran’s leadership may continue to imprison dissenters under the guise of protecting supremacy, but this merely postpones mounting societal backlash, as evidenced by the 1979 Iranian Revolution (Ferrero, 2013). Tese patterns of discontent and resistance indicate that theocratic regimes face inherent limits to their longevity.

Implications for Iran and the Globe

Te persistence of Iran’s theocratic regime carries profound implications, both domestically and globally, as it continues to infuence economic stability, human rights, and regional security. According to Esfahani and Taheripour of the International Journal of Middle East Studies, theocratic governance in Iran has enabled mass economic mismanagement, with an estimated 70 percent of public expenditures occurring ofbudget through hidden subsidies and unaccounted liabilities. Tese extra-budgetary funds, funneled through state-controlled oil, credit, and foreign exchange markets, have distorted resource allocation and fueled chronic infation. As a result, Iran’s economy remains stagnant, with long-term development blocked by inefciency, corruption, and ideologically driven practices (Salehi Esfahani & Taheripour, 2002).

Beyond the economic impacts, Iran’s theocratic identity has also shaped its approach to humanitarian crises, particularly in refugee policy. According to Bahram Rajaee, Director of the Institute for Global Studies at the University of Delaware, Iran, rooted in religious ideology and post-revolutionary solidarity with displaced Muslims, admitted over 4.5 million refugees during the 1980s and 1990s, primarily from Iraq and Afghanistan. Tis infux placed immense strain on Iran’s infrastructure and public services (Rajaee, 2000). Tis prioritization of religious image over administrative capacity continues to hinder humanitarian eforts and fuel regional instability. Together, these outcomes reveal how Iran’s theocratic structure not only weakens its internal governance but also produces ripple efects that complicate international responses to economic and humanitarian crises.

In its entirety, Iran’s theocratic regime presents a range of broader global risks. Te suppression of innovation threatens long-term economic development and limits international trade, while ongoing political repression raises the likelihood of heightened sanctions and volatile oil markets. Although Iran’s economy relies heavily on natural resources like oil and gas, its energy sector remains plagued by inefciency. According to Taiebnia and Barkhordari of the University of Tehran in Iran (2021), despite the government periodically proposing reforms, these eforts have failed to address policy implementation, institutional obstacles, and external pressures such as international sanctions. Recent studies highlight a trend of “policy dismantling”, where instead of enforcing reform, Iran retreats from its own energy policies, further undermining development and revealing profound structural weaknesses in governance. Prolonged instability could trigger increased refugee fows, the spread of religious extremism, and environmental neglect. Moreover, Iran’s model may embolden similar regimes elsewhere, weakening global commitments to religious freedom, educational equity, and human rights. Left unaddressed, the regime’s unregulated control, especially considering its nuclear ambitions, poses not only a regional threat but a profound and potentially catastrophic risk to global stability.

References

Afshar, H. (1995). After Khomeini: Te Iranian Second Republic British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 22(1/2), 187–188. http://www.jstor.org/stable/196001

Amnesty International. (2022, September 23). Iran: Deadly crackdown on protests against Mahsa Amini’s death in custody needs urgent global action https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/ news/2022/09/iran-deadly-crackdown-on-protests-against-mahsa-aminis-death-in-custodyneeds-urgent-global-action/

BBC News. (2020, January 6). Iran profle - timeline https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middleeast-14542438

Bogdanor, V. (Ed.). (1987). Te Blackwell encyclopedia of political institutions (p. 6). Basil Blackwell.

Buchta, W. (2004). Who rules Iran? Te structure of power in the Islamic Republic [Review of Who rules Iran? Te structure of power in the Islamic Republic. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 31(1), 103–108.

Cambridge. (2025). secularism https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/secularism

Chehabi, H. E. (1991). Religion and Politics in Iran: How Teocratic Is the Islamic Republic? Daedalus, 120(3), 69–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20025388

Fazlhashemi, M. (2021). Imāmiyya Shīʿa (Te Twelvers). In M. A. Upal & C. M. Cusack (Eds.), Handbook of Islamic Sects and Movements (pp. 181–202). Brill. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.1163/j.ctv1v7zbv8.14

Ferrero, M. (2013). Te rise and demise of theocracy: theory and some evidence. Public Choice, 156–156(3/4), 723–750. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/42003181.pdf

Foran, J. (1992). Te Long Fall of the Safavid Dynasty: Moving Beyond the Standard Views. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 24(2), 281–304. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/164299

Golkar, S. (2016). Confguration of Political Elites in Post-revolutionary Iran. Te Brown Journal of World Afairs, 23(1), 281–292. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26534724

Harris, K. (2015). Class and Politics in Post-Revolutionary Iran: A Brief Introduction. Middle East Report, 277, 2–5. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44578048

Karsh, E. (1990). Geopolitical Determinism: Te Origins of the Iran-Iraq War. Middle East Journal, 44(2), 256–268. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4328101

Kay, A. C., Whitson, J. A., Gaucher, D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Compensatory Control: Achieving Order Trough the Mind, Our Institutions, and the Heavens. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 264–268. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20696046

Kazemipur, A., & Rezaei, A. (2003). Religious Life under Teocracy: Te Case of Iran. Journal for the Scientifc Study of Religion, 42–42(3), 347–361. https://www.jstor.org/stable/ pdf/1387739.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A04f2accc4f20f261f7c8e260bb555ed0&ab_ segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=&acceptTC=1

Khalaji, M. (2011). Iran’s Regime of Religion. Journal of International Afairs, 65(1), 131–147. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24388186

Martin, V. (2011). State, Power, and Long-term Trends in the Iranian Constitution of 1906 and its Supplement of 1907. Middle Eastern Studies, 47(3), 461–476. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/23054313

Moaddel, M. (1991). Class Struggle in Post-Revolutionary Iran. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 23(3), 317–343. http://www.jstor.org/stable/164485

Rajaee, B. (2000). Te politics of refugee policy in Post-Revolutionary Iran. Middle East Journal, 1–1, 44–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4329431.pdf?refreqid=fastly-de fault%3A41db2819dc11dc76a92e31f6a2d73bae&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_ gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=&acceptTC=1

Salehi Esfahani, H., & Taheripour, F. (2002). Hidden public expenditures and the economy in Iran. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 34(4), 691–718. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/pdf/3879694.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A22a0c98b8869b88abf18264ed3066610& ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=&acceptTC=1

Shirazi, F. (2019). Te Veiling Issue in 20th Century Iran in Fashion and Society, Religion, and Government. Religions, 10(8), 461.

Taiebnia, A., & Barkhordari, S. (2021). Te dismantling of reform policies in the Iranian energy sector. Energy Policy, 161, 112749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112749

Takeyh, R. (2009). Guardians of the revolution: Iran and the world in the age of the ayatollahs. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195327847.001.0001

Varzi, R. (2006). Warring souls: youth, media, and martyrdom in post-revolution Iran: Varzi, Roxanne, 1971-: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive. Internet Archive. https:// archive.org/details/warringsoulsyout0000varz/page/n5/mode/1up

Whittaker, P. (2011, 04). Te People Reloaded: Te Green Movement and the struggle for Iran’s future. New Internationalist, 42. https://cnu.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest. com/magazines/people-reloaded-green-movement-struggle-irans/docview/1285269999/se-2

About the Author

Jaya Daniel is a senior at Christopher Newport University, majoring in Marketing and Management with a minor in Leadership Studies. She is an All-American student-athlete, Director of Operations for Women in Business, and a member of both the Honors Program and the Presidential Leadership Program. She is enthusiastic about leadership, ethics, and the intersection of politics and religion. In the fall, she will begin pursuing her MBA at Ashland University, where she will also compete as a member of the women’s soccer team. Jaya plans to continue her academic career by earning a Ph.D. in Business Administration while running her business, Pioneer Coaching Network. Her academic and professional interests include social impact, nonproft strategy, and youth mentorship.

Chief Justice John Marshall’s Court and How It Shaped the United States Devereaux E. Davis

Faculty Sponsor: Professor William Mims, Department of Leadership and American Studies

Abstract

Tis paper examines three landmark United States Supreme Court decisions: Marbury v. Madison (1803), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). Behind these decisions were brilliant constitutional interpretations by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Te importance of this analysis is to understand the constitutional signifcance of these early 19th-century cases. Chief Justice John Marshall’s decisions established an enduring framework for interpreting one of the most important documents in United States history. While Marshall was a Federalist, he established non-partisan decisions that also favored the Jefersonian Republicans to maintain the words and intent of the U.S. Constitution. Since the monumental period of our early republic, historians have debated the grounds of economic or political coercion, misinterpretation, and unclear precedents. However, Chief Justice John Marshall delivered these decisions to ensure that the future of the United States Constitution would fourish, providing the federal branches with a clearer understanding of their balance of power and answering questions of “federalism.”

Introduction

Few people have embodied the description of “great” to have it appear next to their name in history books. However, the Great Chief Justice John Marshall is one of the few to have earned this distinction. His lasting impact on the American experiment we have today forms the basis for his recognition. From 1801 to 1835, the Virginia native ruled on key constitutional issues that addressed signifcant questions such as “judicial review,” “federalism,” and the “commerce clause.” Te issue of constitutional interpretation has been debated since its signing in 1787. Te centuries that followed have led many diferent jurists and historians to express opinions and make decisions on how it should be interpreted. Some historians view Chief Justice John Marshall as the foundation of judicial power, while others argue that many decisions have been made too vaguely. Chief Justice John Marshall’s court, particularly the rulings in Marbury v. Madison (1803), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), shaped the interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and its enduring infuence on the country’s legal framework. Despite arguments of federal overreach, political and economic infuence, and dubious judicial precedents, Chief Justice John Marshall’s decisions made a signifcant impact.

Chief Justice John Marshall’s court impacted constitutional interpretation, and few people truly know the importance of many of his decisions. Te view and understanding of how Chief Justice John Marshall’s court has revolutionized constitutional interpretation have not received the credit they deserve. Marshall ruled in favor of Constitutional boundaries, state and federal government lines, and the idea of federalism. It is not that all other historians see it this way, though. While it is important to see the diferent sides of the constitutional debates, it is also important to understand how these decisions changed our Constitutional understanding. While some of Chief Justice John Marshall’s decisions were not made in favor of those who express individual rights or state rights, there still needs to be a greater appreciation for what these decisions have accomplished. Te federal and state boundaries were not explicitly set in our Constitution, so some sort of interpretation was bound to happen. Chief Justice John Marshall’s decisions set these precedents and have allowed our nation to thrive for almost two hundred and ffty years.

To understand the issues between, let us call them, “pro-Marshall” and “anti-Marshall” historians and historical fgures, it is key to look at the start of Tomas Jeferson’s presidency and the early stages of Chief Justice John Marshall’s time on the bench. When Jeferson took ofce, the Jefersonian Republicans and the Federalists had vastly diferent views on federal power and the relationship between the various branches. Te early decades of the Judicial Branch were weak. Te Constitution did not provide much guidance on what powers the Federal judiciary possessed and how it was to exercise its authority to check the other two branches and interpret the Constitution. After Marbury v. Madison (1803), which we will later discuss in more depth, the Judicial Branch established its power of “judicial review” and how it is to check the Executive and Legislative branches of government. Te fact remains that these three important cases cemented the Federalist legacy during a time when the Jefersonian Republicans ruled the federal government. Te anti-Jefersonian development of a more powerful judiciary, along with a stronger Executive Branch, as seen in Marbury v. Madison (1803), allowed for greater federal power overall. Tis immediately became a topic of heated debate. Some historians argue that Chief Justice John Marshall’s rulings were legitimate and made in good faith. Others delve deeper into the notion that his decisions were sound but were based on the wrong cases. Te foundation for these arguments is rooted in Jefersonian sympathizers who believed Marshall’s decisions to be outside the ideological beliefs that alienated him at the time.

Two authors, specifcally Harold J. Plous and Gordon E. Baker, have argued that the case McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) was the wrong vehicle for the court’s decision and that

it had allowed for a very unclear precedent that would leave holes for future constitutional issues, which also dealt with federal supremacy over states.1 Another group of authors, including David S. Schwartz, takes the stand arguing that the court’s decision was too broad a federal understanding and that the decision written by Chief Justice John Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), undermined the idea of limited government.2 Michael J. Klarman feels as though Marshall was ruling in favor of political allies, that he was abusing the constitutional interpretation that was set by his own decision in Marbury v. Madison (1803).3 Edward Barrett Jr. viewed the case of Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) as too broad an interpretation of the Interstate Commerce Clause. However, the broad interpretation has been benefcial to constitutional interpretation since. He tips his cap to what Marshall has been able to achieve.4 Another author who supported Marshall was Aditya Bamzai, who felt the Court’s decision delivered for Marbury v. Madison (1803) established the power of Judicial Review. Bamzai goes on to agree that the decision has set a solid foundation for how the Supreme Court has ruled in their cases since.5 Tese are some of the diferent interpretations that historians have taken. It is my opinion that, while some of these seem possible, it is more plausible that Marshall ruled in favor of creating a foundation along with some building blocks for how the newly formed Union would interpret one of its most important founding documents for centuries to come.

Life and Career of John Marshall

Born on September 24, 1755, in Germantown, Virginia, John Marshall grew up with a father who strove toward success and became one of the most successful men in the area. Te education that John Marshall was given was exceptional. He grew up to be focused on his studies and was able to gain a well-nourished education at the school of the Reverend Archibald Campbell, alongside the future president James Monroe.6 He would later be able to gain an education under George Wythe, William & Mary’s frst law professor in the colonies.7 At the time, not many people who got into the legal feld went to a formal law school. Many would gain their knowledge through apprenticeships and self-education. Te formal education in the law would allow Marshall to better understand legal principles and act as an aid in future court decisions.

On February 4, 1801, John Marshall took his oath of ofce to become the new Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He spent many of his frst forty-fve years on this Earth as a state legislator, executive councilor, lawyer, commissioner to France, member of Congress, secretary of state, and Revolutionary War hero. His time as a state delegate would serve as a valuable tool during his tenure on the bench. As one of the delegates from Virginia at the Constitutional Convention, he possessed in-depth knowledge and a comprehensive understanding of the Constitution and its various components.

Marshall had served as President Adams’ secretary of state for the last seven months of his presidency in 1800. Having his hand in the Adams administration seems to be what allowed him to fall in favor with President Adams to install a trusted Federalist into the

1 Harold J. Plous & Gordon E. Baker, “McCulloch v. Maryland: Right Principle, Wrong Case” (Stanford Law Review 9, no. 4, 1957.), 710.

2 David S. Schwartz, “McCulloch v. Maryland and the Incoherence of Enumerationism” (Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Police 19, no. 1, 2021), 25.

3 Michael J. Klarman, “How Great Were the ‘Great’ Marshall Court Decisions?” (Virginia Law Review 87, no. 6, 2001), 1115.

4 Edward F. Barrett Jr., “Gibbons v. Ogden”, (Lincoln Law Review 6, 1932), 1-2.

5 Aditya Bamzai, “Marbury v. Madison and the Concept of Judicial Deference” (Missouri Law Review 81, no. 4, 2016), 1059.

6 Charles F. Hobson, The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law, (University Press of Kansas, 1996), 1-2.

7 Hobson, The Great Chief Justice, 2-3.

Supreme Court. At the end of President John Adams’s time in ofce, he issued a series of federal judgeships to the courts. Marshall’s time on the bench also consisted of sitting in on the United States Circuit Courts for Virginia and North Carolina.8 Serving at both levels, federal and state, allowed him to gain frst-hand education and experience in United States law. Tis would allow him to understand ‘federalism’ at a deeper level than most. It was thirty-four years that the ‘great’ chief justice served on the highest court within the country’s legal system. His time was well spent deciding on the trajectory of the nation and our Constitutional understanding.

Political Landscape and Role of the Supreme Court

As the 1800 presidential election ended, the incumbent, John Adams, had lost favor in the eyes of the American people. Tomas Jeferson, a Virginia native, found himself as the president-elect of the highest ofce in the United States, still in its infancy. Jeferson would later evolve his political party to be identifed as “Jefersonian Republicans.”9 Te devastation would not only shake the Federalist supporters of John Adams but would later show the issues of executive, legislative, and judicial problems within the United States. Te Federalist view of government was more so the view that the Federal government should be expanded and the powers under Federal governance could and will be used in a way where the states are inferior to federal law. It was the idea of a more centralized federal government. On the other hand, the “Jefersonian Republicans” were more focused on a divided system of power where the state governments would be able to have more power over their districts and people.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Supreme Court found itself with a lack of federal powers outlined in the Constitution under Article III. Tere was not much granted to the federal judiciary, which caused many issues of how to interpret what the United States Supreme Court could and could not do.10 In the early years of the Judicial Branch, the Supreme Court functioned as the last level of appeals court decisions. What it will evolve into is a branch that will have the ability of constitutional interpretation and have more rights when checking the balance of power between the branches, in addition to the last level of the court. Te 1800s were a time in which the Supreme Court made some monumental decisions that would change the United States for the better. Te decisions and actions taken by the court, more specifcally, what was written in the decisions, would create guidelines for not only judicial but also executive and legislative powers. What was written in the United States Constitution would be expanded on, interpreted, and given substance through the men who sat on the bench, and more importantly, the chief justice of the Supreme Court from 1801 to 1835.

Marbury v. Madison (1803): Case and Legal Signifcance

On the eve of the incoming Jeferson administration, President John Adams and his administration passed the “Judiciary Act of 1801.” Tis act would reorder the federal judiciary, create new circuit courts, and appoint a list of Federalist Judges. Tese appointments all went through the regular procedures, such as being nominated by the president and being confrmed by the Senate, and the last step was for these appointments to be delivered to the appointees. As Tomas Jeferson took the oath of ofce and secured his role as President of the United States, the “midnight appointments” started to appear. James Madison would be sworn in as Jeferson’s Secretary of State after his predecessor

8 Ibid, 7-8.

9 N/A, “Research Guides: Presidential Election of 1800: A Resource Guide: Introduction,” Introduction - Presidential Election of 1800: A Resource Guide - Research Guides at Library of Congress, accessed April 11, 2025.

10 U. S. Constitution, art. 3.

vacated the seat. Madison would then block the remaining appointments that were never delivered at the discretion of President Jeferson. Amongst those appointments was a man named William Marbury, who had been appointed as a Justice of the Peace for the District of Columbia. Marbury felt as though the President of the United States, John Adams, at the time of his appointment and confrmation, had established his appointment rightfully and that he deserved his position. In trying to compel President Jeferson, a “Jefersonian Republican,” to deliver the “midnight appointments” of these “federalist judges,” Marbury hoped to get the deliverance of his and the others’ appointments. President Jeferson refused to deliver the appointments and told his Secretary of State, Madison, to ensure that these appointments would never be revealed to the public, as they were considered by him as “improper.”11

Following the president’s refusal to deliver, William Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court of the United States, which now consisted of “midnight appointee” John Marshall, to issue a writ of mandamus to the president, forcing him to deliver the rest of the John Adams appointments. A ‘writ of mandamus’ is a legal court order that commands a federal ofcial or body to follow a legal act. It is a judicial power that could order another branch of government to do something, or not do something, because there is a legal requirement for that action. As the weak federal judiciary reviewed this case, John Marshall took this as an opportunity to establish powers for the Judiciary and to create a foundation for the idea of separation of powers. For the Court, if they decided to rule in favor of Marbury, giving power to the Supreme Court to order other federal branches to act according to their writ of mandamus, the decisions would create an earthquake of issues for the future. Tere was also the issue of President Jeferson just ignoring the writ upon its arrival at the White House. Tis would undermine the Judicial powers and solidify the Judicial Branch as weak. On the other hand, if the Supreme Court ruled in favor of James Madison, who was the defendant in this case, then it would also create a ripple efect in judicial powers, asserting the Executive Branch could block earlier executive and congressional approvals.12

In the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision, Chief Justice John Marshall delivered the opinion that while the Executive Branch did not have the power to block previous administration appointments, especially after the Senate’s confrmation, the Judicial Branch did not have Constitutional standing to order a ‘writ of mandamus.’ As well as exercising a legal principle known as ‘judicial restraint,’ Chief Justice John Marshall took a bold stance to decide the legal doctrine of ‘judicial review.’ Te decision that was written by Chief Justice John Marshall acknowledged the fact that William Marbury deserved his appointment as Justice of the Peace, but he highlighted in his decision that he had also come to the Supreme Court improperly. In Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 it allowed the Supreme Court to hear cases dealing with citizens in ‘original jurisdiction,’ but Marshall understood that this provision was not constitutional. He ruled that the plaintif would have to make its way through the various levels of the court before it came to the United States Supreme Court, something that he did not do in this case. He cited Article III of the Constitution, which stated that the Court has the original jurisdiction “in all cases afecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party.”13

It is important to analyze this case and the decision delivered by Chief Justice John Marshall. Te Court chose to avoid confrontation with the Jeferson administration while establishing the idea of ‘judicial review’ to assert the power of the Judicial Branch. Marshall expressed his understanding of Federalist Paper 78, which was written by Alexander

11 John Marshall, “Marbury v. Madison” (1803).

12 N/A William Marbury v. James Madison, Secretary of State of the United States. (5 U.S. 137, 1803), 146-147.

13 John Marshall, “Marbury v. Madison” (1803).

Hamilton, which emphasizes the idea that the Federal Judiciary should have the power of ‘judicial review’ over deciding the Constitutionality of actions taken by the government or those within the United States.14 Marshall also understood that under Article II of the Constitution, “[T]he president shall nominate, and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and all other ofcers of the United States, whose appointments are not otherwise provided for.”15

As Chief Justice of a weakly established Judicial Branch, John Marshall understood the importance of this decision. He knew that, however he would rule, there would be pushbacks from both political parties. As a Federalist decision, the Jefersonians were upset with the broadening of Judicial powers. President Jeferson felt that the Supreme Court had impacted the balance of power between the diferent branches of government. Tey believed that the federal government, let alone the Judicial Branch, should be as limited as possible to allow the states to have equal powers. Some even believed that the language in the decision was faux, and that the Constitution did not allow for some of the decisions made.16 Te Federalists, including William Marbury, were disappointed with Marshall’s decision, feeling as though he did not assert the power to issue a writ of mandamus. Tis resulted in allowing President Jeferson to win in his battle against delivering the Federalist appointments.

Despite the criticisms, Marshall made this decision following the Constitution. Article III of the Constitution outlines the powers of the Judicial Branch and gives the federal judiciary the ability to make the fnal decision in legal cases; they are the highest court in the country.17 He established the powers of the federal judiciary that were not explicitly stated. He felt that for the Supreme Court to rule correctly and efectively, it was the government branch that was allowed to decide the Constitutionality of actions taken by the government or citizens. Tis decision was not an easy one, and it would create the foundation for the decisions to come. In asserting that the Supreme Court has the power of Judicial review, it allows the three branches of government to govern with checks and balances most efectively. Te Legislative Branch would write the laws, the Executive Branch would sign and approve the laws, and the Judicial Branch would check and decide if these laws are per the Constitution. Tat is only the surface-level idea of ‘judicial review;’ it goes more into depth to include the fact that the Judicial Branch has the power to decide if any actions taken by other branches of government are constitutional.

Marbury v. Madison (1803): Historical Views

Following the landmark decision in 1803, there have been many historians and political scholars who have had their views on the decision itself. In Aditya Bamzai’s “Marbury v. Madison and the Concept of Judicial Deference,” the focus on judicial deference was important. Bamzai understood the argument made by Chief Justice John Marshall and wanted to know further if there was strong constitutional standing for the decision. Bamzai posed the question, “[d]id Marbury [v. Madison] have anything to say about interpretive technique in the many other pages that Chief Justice Marshall devoted to statutory interpretation?”18 In the eyes of Bamzai, to have a compelling argument for establishing ‘judicial review,’ Marshall would need to explain the exact powers and procedures the Supreme Court would have to go through in deciding the constitutionality of a case. Te author agrees that, yes, the lessons in Marbury v. Madison established the doctrine of judicial

14 Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist No. 78,” The Federalist Papers, 1788, 235–240.

15 U. S. Constitution, art. 2, sec. 2 cl. 2.

16 Melvin I Urofsky. “The Case of the Disappointed Office-Seeker: Marbury v. Madison (1803),” (Supreme Decisions, 1st ed., 2012), 10.

17 U. S. Constitution, art. 3, sec. 2.

18 Bamzai, “Marbury v. Madison and the Concept of Judicial Deference,” 1059.

deference that is strong in legal theory and allows for particularly important decisions to be made. Bamzai highlights the three types of deference: Treatment of executive custom in statutory interpretation, discussion of the “political question” doctrine, and the use of the ministerial/executive distinction under the writ of mandamus.19 Overall, Bamzai understands Marshall’s decision and why he established ‘judicial review.’

Another author with a similar view but who focuses on another part of the decision is Jerry J. Philips. In Philips’ “Revisiting Marbury v Madison,” he marvels over the striking down of Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789. He highlights how Marshall, in striking that down, made a signifcant impact.20 Few people look at this nowadays, argues Philips. He believes that Section 13 was wildly unconstitutional and that this was a part of the decisions that few people had a problem with. Troughout the rest of his short article, he continues to praise Marshall’s assertion of Judicial power, focusing on how he was able to ensure a strong balance of power between the branches of government, as well as having a long-lasting impact that has allowed for the judicial system and our Constitution to survive this long.

Both views on Marbury v. Madison were delivered by twenty-frst-century historians. Te view on ‘judicial review’ at this time has evolved so much and has a repertoire of hundreds of Supreme Court decisions made based on ‘judicial review.’ We have also made it to a point in our country’s history where we understand the important impact that this decision has had on our Constitutional interpretation. Following my stance on Chief Justice John Marshall and the impact that he has made, these two authors reafrm the importance of Marbury v. Madison (1803) and how, without this landmark decision, there would be a very diferent view of the Judicial Branch and the other two branches of government, the Legislative and Executive, may have expanded their powers and ruin the balance of power amongst the three.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): Case and Legal Signifcance

Following the War of 1812, the United States wanted to charter a federal bank that would be able to rebuild the nation’s economy. Te First Bank of the United States, created by Alexander Hamilton during his time as the Secretary of the Treasury in the Washington Administration, had lost its charter in 1811 due to the refusal by Congress to recharter it. In 1816, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States. Te bill, signed by President James Madison, would charter the bank for twenty years, expiring in 1836, and would aim to bring fnancial stability to the nation. Given that the Second Bank of the United States was created through an act of Congress and was a federal government entity, it had protections that would allow it to have autonomy from state legislative regulations or activities.21

In 1818, two years after the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, Maryland’s legislature passed a law that would impose a ten percent stamp tax on currency issued by the Second Bank of the United States.22 Te bank teller, James W. McCulloch, refused to pay the tax, claiming that the Second Bank of the United States was a part of the federal government. Terefore, the states could not tax it. In response to not paying the tax, the state of Maryland sued McCulloch for $110. McCulloch argued that the federal agency was established constitutionally by the Legislative and Executive branches to fulfll the duties of the federal government and that the state governments cannot interfere with

19 Ibid, 1059.

20 Jerry J. Philips, “Revisiting Marbury v. Madison”, (Tennessee Law Review 71, no. 2, 2004), 313.

21 Raymond Walters. “The Origins of the Second Bank of the United States.” (Journal of Political Economy 53, no. 2, 1945), 116-117.

22 N/A, McCulloch v. The State of Maryland et al. 17 U.S. 316 (4), 318-319.

the actions taken by the federal government that are deemed to be “necessary and proper” under Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution.23

On March 6, 1819, Chief Justice John Marshall delivered the unanimous decision on the case McCulloch v. Maryland. Te Court ruled that Congress had the authority to establish a federal bank and that the federal bank could not be taxed by any governing body. Marshall noted that the Necessary and Proper Clause, which was Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, allowed the federal government to act in ways that were deemed “necessary and proper” to carry out the duties of the ofce.24 More notably, Marshall expanded the idea of “necessary” to mean “appropriate and legitimate” to allow the federal government to better understand its powers. It is important to realize that while Marshall’s decision established federal powers, it also afrmed that the states still had the right to taxation. Tis is important because it helps reassure some sort of “federalism.”25 Maryland was also held accountable for violating the Supremacy Clause of Article VI of the Constitution which stated, “Te Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the land.”26

In understanding if the states had the power to challenge the incorporation of a federal bank, Chief Justice John Marshall investigated the parameters that would allow for its establishment. In his decision, he looks to check of some boxes. He highlights that there was a bill that was passed to allow the federal government to charter a national bank. Tis act was not passed “unsuspectedly” or “unobserved.” Members of Congress and the president were aware of what the bill was that allowed the charter, and it was approved by them. Tis bill was debated fairly and still made its way through the legislative process fairly. Marshall does note that the enumerated powers in the Constitution do not say anything about whether the federal government can create a bank; however, nowhere in the Constitution does it exclude incidental or implied powers. Te authors of the Constitution were not able to insert every minute power that the branches of government have, so the implied powers, under the “necessary and proper” clause, allow Congress to charter the bank.

In addition, the power to levy and collect taxes, to borrow money, to regulate commerce, to declare and conduct a war, and to raise and support armies and navies is within the Constitution. To tax, they need to be able to incorporate a national bank to collect the federal taxes. What is admirable about Marshall’s decision is that “the power of creating corporations is one appertaining to sovereignty and is not expressly conferred on Congress. Tis is true. But all legislative powers appertain to sovereignty…Te government which has a right to do an act, and has imposed on it the duty of performing that act, must, according to the dictates of reason, be allowed to select the means…take upon themselves the burden of establishing that exception…”27 Te Constitution does not permit specifc actions, but for the federal government to operate to its best and to fulfll the duties, especially the ability to tax, they must be permitted to incorporate acts or institutions such as banks, that have sovereignty from states.

Te views on this decision were mixed at the time. Te states felt that the Court had suggested the federal government reign supreme over the states, which it technically does. In the article “John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, and the Concept of Constitutional Sovereignty,” by Clyde Ray, the author refers to a state rights activist named William Brockenbrough. Brockenbrough was the party leader in Virginia when the decision passed. He argued that the Constitution “was adopted and brought into existence by the

23 John Marshall, “McCulloch v. Maryland” (1819).

24 U. S. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 8.

25 John Marshall, “McCulloch v. Maryland” (1819).

26 U. S. Constitution, art. 6.

27 John Marshall, “McCulloch v. Maryland” (1819).

states, who had surrendered none of their original sovereignty upon its ratifcation.”28 He continued to argue that Marshall had thrown out the idea of federalism and did not maintain the balance of state and federal power. Marshall made the case that Congress, elected by the people, acted in accordance with the will of the states. Still, Brockenbrough argued more that the states as a whole were the ones who were represented in Congress, not the people, and that the states had the right over the people in Congress because it was their representatives.29 However, there was concern that the concept of federalism was failing, and that the federal government was overstepping its boundaries under the Constitution. Chief Justice John Marshall ruled to protect the rights of the federal government to execute its duties, not necessarily to the best of its abilities, but at least to fulfll its constitutional responsibilities, such as collecting taxes. Tis decision highlights John Marshall’s Federalist views, advocating for a stronger, centralized government. He wrote his decisions and focused on how the Constitution defned certain powers, such as “necessary and proper,” and how the government was going to be able to do its job the best it could. Tere were no underlying factors in his decision.30 Marshall was trying to create a balance between federal and state powers. Not necessarily undermining federalism, but with this decision, there is a good chance that it resulted in federalism issues that he did not plan for.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): Historical Views

Tis case had a little more controversy in the years following. First, we look at Sanford Levinson’s “Te Confusing Language of McCulloch v. Maryland: Did Marshall Know What He Was Doing (or Meant)?” Levinson ofers interesting insight into why he thinks that Chief Justice John Marshall’s decision is weak. Te main argument is not that it lacks length and explanation, but that the decision ofered was too long. Te written decision by Marshall is too lengthy and confusing for people to be able to brief. Levinson compares the decision to the courses he teaches and how much time it has allowed his students to be able to thoroughly analyze them. He understands that it is hard to brief a case, and he believes that a decision should not be briefed, as many parts of the Court’s written decision are too important. Te alternative that he ofers for McCulloch v. Maryland is that what Marshall wrote is so unclear, so inconsistent with other parts of his draft, that there is no true constitutional argument.31 As well as unclear, Levinson also argues that Marshall, being a Federalist, used his political views as a sort of lens to look through when writing his decision. Tere is his argument for a debate in his journal that he believes the Constitutional question of “necessary and proper” was put on the back burner when deciding this case.32

In concurrence with Sanford Levinson’s piece on McCulloch v. Maryland, Harold Plous and Gordon Baker argue that the decision reached by the Supreme Court was unclear and not the right case to make its Constitutional standing. In their journal, “McCulloch v. Maryland: Right Principle, Wrong Case,” the authors reference some of the important quotes remembered from this case, such as “the power to tax involves the power to destroy.”33 Te authors focus on how Marshall’s decision was very “generous” in

28 Clyde Ray, “John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, and the Concept of Constitutional Sovereignty.” (Perspectives on Political Science 47, no. 2, 2018), 72.

29 Ray, “John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, and the Concept of Constitutional Sovereignty,” 73.

30 N/A, McCulloch v. The State of Maryland et al. 17 U.S. 316 (4), 331.

31 Sanford Levinson, “The Confusing Language of McCulloch v. Maryland: Did Marshall Really Know What He Was Doing (or Meant)?” (Arkansas Law Review 72, no. 1, 2019), 11.

32 Ibid, 9.

33 Plous & Baker, “McCulloch v. Maryland: Right Principle, Wrong Case,” 710.

its construction of the “necessary and proper” clause. Much of what they feel is that the precedent set was not clear enough. In the matter of economic infuence, Plous and Baker viewed the Second Bank of the United States as a “ruthless and irresponsible institution” that was a giant that was being controlled by a group of private bankers who wanted to turn personal profts.34 Plous and Baker ofer an alternative to this decision. Tey say that even if Marshall stuck with McCulloch v. Maryland, he could have delivered the decision that still afrmed Congressional power to have constitutional authority to create a national bank to tax and handle money. However, if Marshall wanted to maintain that states could not tax the federal institutions, it could be because it would interfere with federal powers. In the end, the Court could have sided with Maryland by arguing that the Second National Bank was not a true federal agency, which means they would not be entitled to the same legal protections, like immunity from state taxes. Plous and Baker feel that Marshall missed afrming some sovereignty to the states by allowing broader legal protections for Congressionally chartered entities.35 Tese authors were twentieth-century progressive thinkers focused on the economic infuences of the Court. A lot of what they are arguing is through the lens that Chief Justice John Marshall was writing his majority opinions based on economic advantages. Tey believe that not only was his precedent unclear, but he was not using Constitutional theory and proper ‘judicial review’ to decide on this case. Tere is not much to agree with here. It is understandable how difcult this decision was, but it is not likely that Marshall had economic priorities on his mind. Tis was a case that wanted to deal with the Necessary and Proper Clause outlined in the Constitution, which wanted to ensure that the federal government was going to be able to execute its powers properly. Te last source to look at when reviewing this case is “McCulloch v. Maryland and the Incoherence of Enumerations” by David Schwartz. Te baseline for Schwartz’s argument is the three major questions asked and answered in McCulloch v. Maryland. Te frst question is, “Can an efectual national government with implied powers be meaningfully limited to a set of enumerated powers?” Te second is, “Can the Tenth Amendment’s concept of reserved state powers be presumptive or meaningfully specifed under a system of implied national powers?” Te fnal being, “Can the state governments meaningfully be called ‘sovereign’ in either of the two distinct senses usually meant?”36 In the end, Schwartz decides that McCulloch v. Maryland decided “no” to all these questions. Te problem that he has with this case is that the case decided on federal supremacy, which made the states “subordinate governments” and destroyed a lot of their powers that would otherwise be granted to them in the Tenth Amendment. Tere was an issue with whether the Tenth Amendment allowed for implied powers for the states that were not outlined in the Constitution for the federal government. Te reserved powers of the state are not to obstruct federal implied powers. Te issue with this is that both the federal and state “implied powers” cannot be defned. Te very nature of the term “implied” is that they are not explicitly written out, but based on other articles within the Constitution, there are still powers that can be interpreted. Schwartz argues that even though the three issues raised earlier were addressed in the case, the issues were never truly settled. Following the decision in 1819, other cases decided by the Supreme Court of the United States did not reference the decision delivered by Marshall. Schwartz points out how the next time the court used the precedent was in United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941) 37 He points this out to show how the precedent set was not strong and has caused many courts to misread it since then. He also feels that it was too broad an interpretation of federal powers. He understands Marshall wanting to establish boundaries for federal powers, but he feels that there was too much wrongful

34 Ibid, 719.

35 Ibid, 727-728.