WHEN I WAS A CHILD there was a single fir tree in our front yard and across the street, where my grandparents lived, was a magnificent weeping willow. These two trees, almost forgotten until now, were the first of many that would make a difference in my life. As I sit here thinking about what trees mean to me, the memories flow. I don’t recall if I was five, six, or seven… or perhaps it was all of those years, but I vividly remember sitting at the top of the fir. I would climb right up until the branches became so small I couldn’t be sure they wouldn’t snap under my weight. I took my chances. I wanted to hide, camouflaged, or at least I imagined so. There I would sit like an owl, quietly watching the goings-on up and down the suburban street until my mother called, pretending to look for me. That tree was my place to be alone with my thoughts.

The weeping willow, on the other hand, was the tree where my young social life came alive. It was a beauty with long flowing branches. My sister, my cousin Jaime, and the neighbourhood kids would come to swing on its pendulous branchlets. We would laugh, swing, jump, and chase each other under its canopy.

As I grew, my relationship with trees changed, there were tree forts to build, furniture to refinish, things that needed building, and sticks that held marshmallows around campfires with my own kids. There were also the dozens and dozens of hikes through remote areas and national parks, and the time my kids wandered into the bush behind my house and got lost. Of course, I found them, huddled under a tree.

from the air, they improve water quality and reduce flooding and erosion. They are the keepers of biodiversity whether one single tree, or a forest of trees. With this edition of Saving Earth Magazine, we aim to emulate the Lorax and speak for trees.

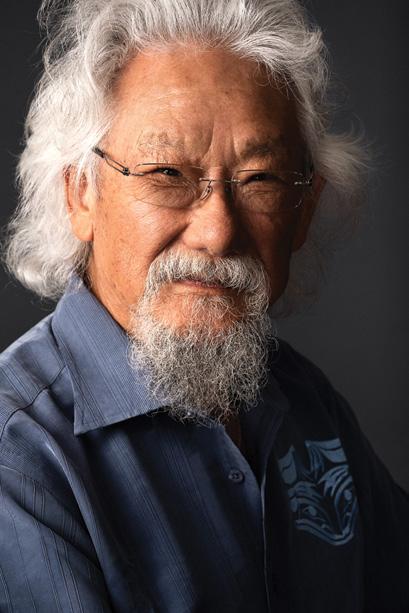

In this issue we join with Sierra Club BC to help stop clear-cut logging of BC old growth. We look at the devastating wildfires that have recently occurred, and learn about replanting trees with One Tree Planted. We explore a nature-based economy with Greenpeace, and speak with Minto Roy from Social Print Paper about environmentally-friendly paper. We also look at Community Forestry Concessions and how they can prevent narco-deforestation in Guatemala, and include a special report from our journalist Sergio Izquierdo on palm oil plantation pollution. David Suzuki joins us on the topic of decolonization, and Jan Lee gives us an inside look at mangrove forests. We study tree trunks with FLAAR Mesoamerica and look at how parrots in Belize disperse seeds and help the forests grow. We look at the benefits of hemp with Hemp Save the World, talk gift wrap with Green Okanagan, and look at how trees create oxygen with educator Ingrith León in Teaching Science.

During those times I did not think about the science of trees. I just admired their beauty. Today I still admire their striking forms, but I am also aware of how fundamental they are. Nothing lives without the trees. They provide us with oxygen, they filter contaminants

Our next edition will be dedicated to climate change. We are inviting Climate Reality Leaders to join us in this special edition, helping to bring awareness to the climate crisis in order to invoke policy changes, and fight for this planet.

If you want to participate in Saving Earth, whether through content contributions, advertising, sponsorship or as a member please contact me at teena@savingearthmagazine.com.

Thank you for Saving Earth

, Teena Clipston, publisher of Saving Earth Magazine and Climate Reality LeaderPUBLISHED BY SAVING EARTH

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Teena Clipston

SENIOR EDITOR

Cassie Pearse

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Dean Unger

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Cassandra Redding

ADVERTISING

Anne-Marie Freeman

CONTRIBUTORS

Kayla Bruce, Roslyne Buchanan, Teena Clipston, Alex Fullerton, Nicholas Hellmuth, Sergio Izquierdo, Colette Kase, Olivier Kölmel, Jan Lee, Ingrith León, Shayne Meechan, Cassie Pearse, Tara Pilling, David Suzuki, Dean Unger, Meaghan Weeden

PRINTING

Royal Printers

DISTRIBUTION

Magazines Canada & Royal Printers

SPECIAL THANKS

to the Hitz Foundation for their generous donation.

COVER PHOTO

Benedek

Saving Earth Magazine has made every effort to make sure that its content is accurate on the date of publication. The opinions expressed in the articles are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the publisher or editor. Information contained in the magazine has been obtained by the authors from sources believed to be reliable. You may email us at Saving Earth Magazine for source information. Saving Earth Magazine, its publisher, editor, and its authors are not responsible for any errors, omissions, or claims for damages, and accepts no liability for any loss or damage of any kind. The published material, advertising, advertorials, editorials, and all other content is published in good faith.

©Copyright 2020 Saving Earth. All rights reserved. Saving Earth Magazine is fully protected by copyright law and nothing herein can be reproduced wholly or in part without written consent.

PRINTED IN CANADA savingearthmagazine.com

info@savingearthmagazine.com

Phone: 250-754-1599

ISSN 2563-3139 (Print)

ISSN 2563-3147 (Online)

Library and Archives Canada, Government of Canada

Saving Earth Magazine focuses on environmental issues, green businesses, conservation, human rights, and climate science. It inspires readers to change how they interact with the planet and offers solutions to global environmental challenges that we face. Some of these solutions include directing readers to organizations and businesses that are making a difference, giving them the ability to support and follow the issues they care most deeply about.

Across the world, we see a groundswell of people engaging to protect their environment, from governments banning plastic bags to individuals inventing exciting new green technologies and Saving Earth Magazine is becoming a part of this step-change. There has never been a more crucial time for this magazine. We don’t just want to report the conversation, we plan on creating the conversation!

At Saving Earth Magazine, we strive to create and bring together ideas that have the power to transform the way we interact with the planet – to devise, communicate, educate, share and help implement strategies and new technologies, which reduce pollution, reduce greenhouse gases, nurture and protect flora and fauna, and protect the waterways.

With contributions from experts and fieldworkers from around the globe, we seek to inspire individuals and organizations to become motivated to protect the planet. We cover stories of success in pioneering fields of ecology and environmental sciences; stories from communities that have faced challenges and found equitable, sustainable solutions that the world should replicate; and inspirational human interest stories and biographies that serve to inspire our lives and help us reconnect to the Earth.

By sharing ideas about how we can make a better world, we will help to heal communities and support those who are at the forefront of ecological and environmental research. Saving Earth Magazine is a manual that can be referenced globally, and will provide an evolving canvas of themes, information and ideas, which will inspire a new era of human interaction with the planet. It is a public forum where ideas and dialogue help to shape our thinking in these emerging fields. It will help us rethink the way we interact with the planet as we seek to find solutions in the transition from fossil fuels, and into new vistas of renewable energy and resources.

FACEBOOK.COM/SAVINGEARTHMAG

INSTAGRAM: @SAVINGEARTHMAG

PRINTED ON

TWITTER: @SAVINGEARTHMAG

ISSUU.COM/SAVINGEARTHMAGAZINE

The issue of old-growth logging has reached critical mass in British Columbia. Seasoned environmentalists and scientists say we're out of time, and the provincial government has so far failed to act... again.

With BC old-growth apparently still on the menu despite decades of opposition and conflict, logging companies and the agency that is charged with oversight and licensing of a portion of the province's merchantable timber have their sights set on some of the last remaining old-growth forests of British Columbia — both in the interior, and on Vancouver Island. Recent reports among environmental agencies, from scientists, and in many community newspapers, have also surfaced, which indicate a long history of neglect and short-sightedness by the government agencies charged with managing the province's forests.

Both an independent scientific report, published in June 2020, and a new strategic review commissioned by the BC government and prepared by an independent panel of two foresters, support the view that BC’s most endangered old growth forests, defined as those forest areas with less than ten percent of their area covered in old growth, must be protected now, to avoid irreversible damage and biodiversity collapse in this unique ecosystem.

Conservation North’s, Michelle Connolly, said that BC has “failed to meet a basic and straightforward recommendation by scientists and their own appointed panel, which is to stop harvesting the rarest old growth forests immediately.” Connolly's frustration comes after decades of controversy about logging, preserving old-growth forests and sensitive habitat areas.

A story by Narwhal Magazine, published in October 2019, revealed the BC Timber Sales office was found to be violating old-growth logging rules. The BC Timber Sales (BCTS) office is a division of the Ministry of Forests, Lands, and National Resource Operations and Rural Development (FLNRORD). This agency plans, manages and issues logging permits for approximately 20 percent of the province’s merchantable timber, which is located on Crown lands and which fall outside of forestry tenures.

To combat mounting public opinion, in September 2020 the BC Government announced a new approach to old-growth logging. The Times Colonist carried the story, stating the protection of the province's old-growth forests requires a united effort of groups, industries and people who have often disagreed over land-use issues. Forests Minister, Doug Donaldson, claims the government wants to break

from the confrontational past, and now fully involve environmental groups, Indigenous leaders, forest companies, labour organizations and communities, while working together to protect forests and support jobs. However, many say it's likely another case of “talk-and-log”.

In an interview with Saving Earth Magazine, Senior Forest and Climate Science Advisor for Sierra Club BC, Jens Wieting, said British Columbians are not being forced to watch helplessly while the last old-growth forests are logged. “This is the time to keep the pressure up,” he insists. “Why? We are witnessing a number of tipping points simultaneously. Tipping points make it impossible to maintain the delusion that BC’s forests are well-managed, a point made very clear in the damning findings of the independent old-growth panel, which submitted its report to the BC government in the spring of 2020.”

Wieting points out that for decades successive BC governments, and the industry they support, have remained in denial about the inevitable impacts of harvesting the last old-growth forests. “Denial about the impacts for the web of life, the cultural values of Indigenous Peoples, gifts that the forests provide, and that we all depend uponlike clean water and a stable climate - and ultimately [the impacts] on forestry workers once the last big trees are gone. They [the industry]

stayed in denial about the growing support for social justice and what it really means to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and to work with their respective governments. The BC government brought into force legislation to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), but is still seeking to maintain business as usual for as long as possible, rejecting the reality that token consultation before clearcutting is no longer an option.

“They are in denial about the speed of ecosystem breakdown, resulting in an ever-increasing cost for logging the last intact forests, more loss of species and more loss of environmental services like clean air and clean water. Cutting the last ten percent of big, old trees has worse consequences than cutting the first ten percent,” Wieting warned.

He went on to point out that the industry players are in denial about the dangers of the climate crisis, and what continued logging of the last old-growth forests means for communities threatened by

droughts, flooding, landslides, heat waves and wildfires, all of which are made worse by continued clearcutting. “They are in denial about the anger of concerned citizens fully aware of the crisis and unwilling to see the last big trees cut down, rising up to defend the last stands,” Wieting stated, “like the two men who were on hunger strike this summer, and the ongoing blockades of logging roads near Fairy Creek, in Pacheedaht territory, on Southern Vancouver Island. All of these factors led to the fate of BC’s last old-growth forests becoming an election issue in the 2020 snap election. Both the Green Party and, with some delay, the NDP, promised to implement all of the 14 recommendations of the old-growth panel (while the Liberals stayed silent on increasing protection).

Back in 2002, following a concerted lobby effort by forest industry interests, Gordon Campbell's Liberal government (in power from 2001 – 2011) replaced the Forest Practices Code with the Forest and Range Practices Act and, as outlined in a story published in September 2020, in the Tyee, “Oversight was outsourced to “qualified professionals” working for timber companies — effectively privatizing public forests. From 2004 on, conservation could only happen “without unduly reducing the supply of timber.”

To counter the prospect of vast deregulation, several environmental groups rallied to take an eleventh-hour run at old-growth deforestation. Sierra Club BC, for one, was deeply concerned that the initiative was a continuance of prior methods, and would take forest policy in a direction that "tosses fundamental elements of forest management to the industry." Now, eighteen years later, it's evident they were right to be concerned.

An ENS Newswire story , in May 2002, detailed that Campbell, and then Forest Minister, Mike DeJong, used principles identical to those that underlie the environmental policies of the Bush administration south of the border, and that [logging] companies would “have lots of leeway” when it came to regulatory expectations and in deciding how to meet them.” Specifically, according to the ENS story, DeJong said that the new code will "avoid dictating" to timber companies how results are to be achieved. Instead, companies "will determine the most appropriate methods to use.”

Essentially, the historical record shows that the Liberal Party indeed deregulated the industry and put the final chapter on the elimination of smaller mom-and-pop logging outfits.

Now, environmental organizations, scientists and policy makers are voicing strong opposition as the present NDP party continues to break its own rules and is stripping the province of its last remaining old-growth.

In an October 2019 story on logging in the Nahmint Valley, in Narwhal Magazine, journalist, Judith Lavoie stated, that allowances by the BC Timber Sales office were indicative of a truly corrupt system. “Two investigations, released under Freedom of Information laws, showed the agency had ignored best practices and available data when auctioning cutblocks in the Nahmint Valley — home to some of Vancouver Island’s last remaining stands of un-logged ancient forest.”

The BCTS office, intended to be an independent agency charged with monitoring timber licenses and allotments, was found to be grossly negligent in its duties regarding logging in the Nahmint Valley. Since then, evidence of questionable conduct by the BCTS continues to surface. Conclusions from both of the reports referenced above, determined the agency was derelict in its duties and mismanaged the forests in its charge, in particular, old-growth forests.

Yet despite widespread opposition and challenges from environmental agencies such as Sierra Club BC, Greenpeace, and the Ancient Forest Alliance, who are calling the provincial government out on its failure to ensure sustainable forestry practices, the provincial agency continues to permit logging in contested and formerly restricted areas.

The problem has been clearly stated on numerous occasions, yet many are left wondering, where are the levers of democratic process? A cursory look over the last century reveals a battle between corporate logging interests, a consistently ineffectual government when it comes to old-growth policy, and acceptable public policy. It's clear previous provincial governments receive a failing grade when it comes to reflecting the needs of the environment, and the will of the people.

With respect to provincial government policy regarding BC's forests, the historical profile belies decades of questionable tactics, performance and result. The force of lobby and the questionable and obscure relationship between government and industry, when it comes to the policies that arise from such influence, has grown along-side overreaching deregulation and lax lobby laws and requirements. Add to this the government's historic propensity for creating large profits in raw industry and resource sectors at the expense of creating infrastructure in local economies, and within First Nations' communities. Essentially, this has worn away at the security of communities that depend upon such resources for livelihood, recreation and quality of life.

The bottom line is, profound environmental destruction often comes with such unregulated, unchecked industrial aspirations, where government seems complicit, and the sensibilities of the public are ignored.

On September 11, Forest Minister Donaldson said the province was going to cease logging in 350,000 hectares of old-growth in nine specific areas of the province. However, an independent study titled, “BC’s Old Growth Forest: A Last Stand for Biodiversity”, was released by a group of BC ecologists, who had previously worked for the provincial government.

According to the provincial government, 23 percent (approximately 13 million hectares) of the province's present forests are classified as old-growth. In fact, only three percent of BC forests should be classified as old growth, and within that, only 2.7 percent of the trees are actually old. “The old forests are now all but gone due to intense harvest,” said Rachel Holt, one of the study's authors. She points out that the forest ministries recently announced two-year shutdown of old growth logging is “mostly in areas that were already protected, had already been logged or were not slated for logging at all. I am baffled by that,” she said in an interview with Narwhal Magazine. She called the government’s framing of the data “very misleading.”

Donaldson’s announcement was issued alongside the province’s own report, titled, A New Future for Old Forests. Meanwhile, Holt, and her coauthors, Daust and Price, insist the province had misled the public for decades, by over-counting old-growth. They feel the report was generally accurate, but that the province’s first step in implementation was all wrong. A New Future for Old Forests confirms the province has not managed old-growth forests properly for many years, and had been working with an outdated approach. The report also states that ecosystem health and biodiversity must become a priority.

According to Narwhal, Price, Holt and Daust have called upon the province to implement an immediate moratorium on harvesting old and mature forest in ecosystems with less than ten percent of old forest

remaining, even if they fall within existing cutblock permits. They are also asking the government to increase old-growth retention targets and improve old-growth management areas.

Wieting says it's pretty clear that successive provincial governments have worked to create an illusion that forests are well managed, that we have strong laws and sustainable forestry, but the reality on the ground brings the house of cards down. “The evidence in the form of data and mapping is overwhelming,“ he said. “Few people remain in denial about the facts when only three percent of old-growth forests with very big trees remain standing.”

A November 2019 poll commissioned by the Sierra Club showed there is widespread support for the protection of old-growth forests across British Columbia and that 92 percent of British Columbians want old growth forests protected.

Over the last two decades, governments in North America seem to have shifted from oversight of public good and community interest, into mechanisms of industry, to be plied and coerced, via donation, to look out primarily for industry interests. This is true in the province of British Columbia, and within Canada in general, where the weight of force has also transitioned largely to commerce and industry, over equitable policy.

In 2018, Attorney General, David Eby, (NDP) told the people of BC that the province would take adequate measures to ensure greater transparency. Andrew Weaver, BC Green Party leader, agreed, saying, “These changes will improve accountability in government decision making. [These] rules will strengthen the integrity of the decisions made in Victoria, while ensuring that the lobbying industry adheres to high ethical standards."

“Big money and political insiders have had too much influence for too long,” Eby said. “These changes are long overdue and build on our continuing work to strengthen BC’s democracy for all British Columbians.”

The changes he is referencing regard efforts to air out decades of dirty government laundry when it comes to logging, and to stem the unbridled influence of big business. Bill 54 was part of this initiative. It's a somewhat subversive history that extends back to the 1950s, and was described in painful detail, in Joe Garner's 1991 book, Never Under the Table. It details decades of corruption, extortion, and bribery in the logging industry on Vancouver Island from the 1950s onward, much of it landing at the feet of the various provincial governments over the years.

The question is, why do so many loopholes persist? The Narwhal story points out that Duff Conacher, coordinator of Democracy Watch, an Ottawa not-for-profit focused on making Canadian governments and corporations more accountable, “has a disturbing explanation for why the NDP has talked tough on cleaning up lobbying yet

failed to go the full distance. There’s no other reason to leave the loopholes open, except that government wants secret, unethical lobbying, so they can do secret deals behind closed doors with interests they favour. There is now a publicly accessible, searchable database that provides a window into how government works, including the thousands of lobbying records of former BC politicians-turned-advocates.”

A 2017 Corporate Mapping Project concludes that “BC stands out in Canada in terms of its weak regulations against corporations influencing public policy. The report also found 'substantial overlap' between the top corporate political donors and the most frequent lobbyists — suggesting the two practices “work in tandem” to ensure companies with ample resources can leverage those resources to gain the ear of politicians.” To date, no major changes to lobby and gerrymandering laws have been exacted.

Couverdon, the real estate arm of TimberWest, was created to maximize revenue as land values outweigh the value of timber. As actual forestry has shrunk dramatically, with mill closures, raw log exports and with the prospect of declining forestry jobs, the company has morphed into real estate development. How will this affect long-term sustainability of land and company? For many, it has raised further concerns about a sustainable future, log supplies and jobs for forestry workers. “Combined, these two forestry companies (Timber West and Western Forest Products) own approximately 1,439,200 acres of Vancouver Island land,” wrote Ceritanne, in the Watershed Sentinel (March 2014), “and both are transforming themselves into real estate development companies and selling off their land.” Despite much misgiving about the way these logging companies came into possession of almost the entire of Vancouver Island, nothing has been done to address the issue.

Many of our scientists, and the public at large, appear to be in agreement with the conclusions of the old-growth review panel, when it declares the need for an immediate moratorium for old-growth sites while effective strategies are found. It is widely agreed that there must be provincial government control over BC Timber Sales’ planning and operations, to accelerate conservation of endangered old-growth forests. An effective Old-Growth Forest Protection Act should be put into force, and a science-based legislated plan that includes targets and timelines for protecting old-growth in all forest types and based on the best available science-based criteria.

Further, a sustainable, value-added second-growth forest industry must be supported by implementing regulations or tax incentives to retool old-growth mills and to process second-growth logs. The report recommends forgoing the provincial sales tax on new mill equipment, reducing stumpage fees or property taxes for companies which invest in second-growth mills. Using stumpage fees to expand markets for sustainable, value-added, eco-certified, second-growth forest products would go a long way to stopping the marketing of old-growth and raw logs. Raw log exports would be curtailed by actually banning oldgrowth log exports and increasing the fee-in-lieu (i.e. log exports tax) on second-growth log exports. Increased First Nations' input is also strongly advocated.

“For the first time in decades, we have a coherent path towards protecting the last old-growth forests across the province, with a timeline for implementation within three years, “Wieting said. “Working with indigenous decision-makers, the next BC government has to demonstrate accountability to deliver on this promise from day one. It will depend on all British Columbians to keep the pressure up, to make the old-growth panel plan a reality. Forests are giving us immeasurable benefits. It’s time to give back to the forests that sustain us.”

It’s not too late. You can help protect the last remaining ancient forests. Take action today at sierraclub.bc.ca/OldGrowth

Photos by Sierra Club BC and Louis Bockner

Photos by Sierra Club BC and Louis Bockner

Amesmerizing spectacle of vivid oranges and reds, a cacophony of crackling and roaring, fire has commanded our attention from the beginning. One moment fire offers warmth to our weary bones and energy to heat our food, while the next it challenges our existence.

Trees are complicit in this dichotomy. Trees are a key component in the “fire triangle” as fuel, one of the three elements required for a fire to burn in collaboration with heat and oxygen. How the wildfire develops depends on the interaction of fuel (needles, leaves, twigs, trees and deadfall), weather and the topography.

While that is the science of it, devastating headlines blaze across our news and social media sources in 2020 as wildfires burn forests in record-breaking proportions in California, Colorado, the Pacific Northwest and in the Amazon rainforest. Meanwhile the toll of last season’s wildfires in Australia are still being tallied.

In the United States and Canada, peak fire season tends to run from mid-May to August. It can run from April to October, although it’s unusual to witness such volatility so late in the season. Those of us living in British Columbia were lulled into complacency given wildfire activity here didn’t really heat up until well into August 2020. About

ten kilometres north of my home, the Christie Mountain fire was discovered on August 18. It is thought that lightning caused this interface fire (a fire that can spread to human structures whilst still burning in forests) that burned down a home and some 2,122.5 hectares in difficult terrain before being held September 9. Among those evacuated and others on evacuation alert were friends of mine. It was a stern reminder to remain vigilant. Here, in Western Canada, the 2020 fire season was less severe.

South of the border, in the USA, things are far bleaker. As I write this, wildfires still rage while some headway in containment is finally being made in cooler fall temperatures.

On October 6, CNN and other news sources reported that the “California fire is now a 'gigafire', a rare designation for a blaze that burns at least a million acres. The August Complex is now the largest fire in California's history.” Sadly, this isn’t the only gigafire the USA has suffered. The most recent one, in 2004, burned some 1.3 million acres in Alaska’s Taylor Complex. In Australia, earlier this year, we witnessed a gigafire burn roughly 1.5 million acres when two fires merged.

Photography: J Bartlett, Team Rubicon/BLM for USFS

Photography: J Bartlett, Team Rubicon/BLM for USFS

For California, the gigafire designation is in addition to a number of records already set. The more than four million acres burned so far in 2020 is over double the previous record set in 2018. Statistics researched by CNN meteorologist Robert Shackelford indicate, “California wildfires have increased in size eightfold since the 1970s, and the annual area burned by fires has increased by nearly 500 percent.”

Signs point to global warming as a huge contributor to the factors causing these record blazes. “Humancaused climate change was creating higher temperature extremes and drier vegetation, conditions conducive to deadlier and more destructive wildfires,” explained Daniel Swain, climate scientist at UCLA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research to CNN.

Climate change as a factor in the increasing severity of wildfires becomes even more compelling looking at new patterns in precipitation, both snow and rain, ocean temperatures, greenhouse gases, vegetation shifts across the planet, and other fluctuations from historic norms.

Heartbreaking 2020 impacts tallied to date in California include loss of life of 31 people, more than 8,400 buildings burned, among them homes and businesses such as world-renowned Napa and Sonoma wineries, and with so much habitat destroyed, countless wildlife displaced or killed. Plus, there have been record lows in air quality as dense smoke drifted into major cities from San Francisco and into Canada, blocking the sun and creating effects yet to be fully assessed.

The Glass Fire burning in California’s wine country remains a top priority and at time of writing, it is only 50 percent contained. Cal Fire, on October 6 said that 290 Napa County houses and 321 commercial structures were destroyed. Residential destruction was greater in Sonoma County where 310 single-family houses were lost, but only 12 commercial structures were destroyed.

In some areas, mandatory evacuations have been lifted and residents have returned home. Through my friend, Inga Aksamit, a California-based author, who lives in Kenwood, I’ve watched the saga unfold via our Facebook connection.

While we can peruse the numbers and try to imagine the toll it has taken on individuals and businesses, hearing your friend’s firsthand account rips into your soul why we must take measures to mitigate these fires.

With her permission I share her Facebook post upon returning home from mandatory evacuation:

“What's it like to be home? Good and not good. Good to come back and have the house standing. Wonderful to see neighbors and share stories. But sobering to see charred hillsides once again, some blackened and some eerily white from intense heat. A huge sign in Hwy 12 directs trucks to a PG &E "Base Camp". It's an enormous field with large rolls of cable and

piles of equipment needed to erect new poles and string new electrical wire. Houses and ranches are missing — just blank spaces. I wanted to come home yet I didn't want to see what I had to see. I know it will be tempting for some of you to talk about recovery and spring wildflowers and the longterm health of the forest. Yes, we know. We just did this three years ago and neighboring areas did it two years ago and last year. We're resilient and we'll get through it but it's hard to see. Part of this feels too familiar but I don't think any of us feel the same as last time. It's not new anymore. Last time every day was uncharted territory. Now we know too much. There are many questions about how to live in this new version of the world and I have no answers. I'm so sorry for all of our neighbors and beyond who lost their homes. I wish I could hug everyone I see like we did last time but we can't even do that.”

She also said she witnessed:

“more talk among my friends wondering about how much more we can take and perhaps considering a move, but where? We run down various lists and know that fire can be everywhere in the west where we want to be — California, Washington, Oregon, BC and even Alaska and the Yukon. And the worsening hurricanes and tornadoes, floods, sea rise, etcetera. Climate change is here.”

Aksamit is right. It is not an isolated incident. In the United States in early October according to the Insurance Information Institute, 65 large fires are burning in California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and five other states. Oregon fires also resulted in at least 11 deaths, thousands evacuated from their homes, 3,000-plus buildings burned and whole towns decimated.

To review the complete lists of all active wildfires across the United States, visit the National Interagency Fire Center website (FIFChttps://www.nifc.gov/). For lists of Canada’s fires, visit the National Wildland Fire Situation Report (https://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/report).

We are not alone. Worldwide, the news is also devastating.

Statistics published by the Parliament of Australia speaks to the devastation:

• 33 people died including nine firefighters

• 3,094 houses were lost across New South Wales (NSW), Victoria, Queensland, Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Western Australia and South Australia.

• Over 17 million hectares were burned.

• Park lands and reserves were devastated, impacting natural flora and fauna. In NSW, World Heritage property including more than 80 percent in Greater Blue Mountains and 54 per cent in Gondwana Rainforests of Australia had been affected by fire.

• In its Annual Climate Statement 2019, the Bureau of Meteorology noted ‘The extensive and long-lived fires appear to be the largest in scale in the modern record in New South Wales, while the total area burnt appears to be the largest in a single recorded fire season for eastern Australia’.

• Conservative estimates of how many animals died using numbers just from NSW and Victoria projected losses of over one billion mammals, birds and reptiles combined. Loss of insects were reported in the hundreds of billions.

• While the impact on many rare or threatened animals, plants and insects is yet to be fully determined, various modelling projects some losses of species could be permanent. From this analysis, a provisional list of 113 animal species were identified as highest priorities for urgent management intervention.

• Lightning was deemed the predominant natural source of the bushfires – about half the ignitions. The remaining ignitions are attributed to accidental or deliberate human origin.

As reported by Al Jazeera, “The Brazilian Amazon is experiencing its worst rash of fires in nearly 10 years, data from space research agency INPE shows. Last month, INPE satellites recorded 32,017 hotspots in the world’s largest rainforest, a 61 percent increase compared with the same month in 2019.”

Often called “lungs of the Earth”, the Amazon is experiencing some “28,892 active fires in the Amazon basin alone” as reported by thenewdaily.com.au. Of these, 27 percent of fires in September were burning primeval forests – old-growth forests that had previously been almost completely undisturbed by human activity. Rômulo Batista, Amazon campaigner at Greenpeace Brazil notes, “The fires are not only a threat to climate and biodiversity, the smoke from the fires adds another threat to the health of people living in a country already strained by the COVID-19 crisis.”

Contributing to the increase in fires is deforestation that is linked to President Jair Bolsonaro dismantling environmental laws to allow more commercial operations in formerly protected areas. Farmland and other recently deforested areas are also ablaze as a dry season more severe than last year points to climate change. One factor causing this is moisture being diverted from South America due in part to warming in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean.

CBC News reported in September that Brazil’s Pantanal is on fire despite the fact that “world’s largest tropical wetland is not supposed to burn.” We learned that “A UNESCO heritage site and one of the world's most diverse ecosystems — home to dozens of endangered

species and the densest concentration of jaguars anywhere — is in jeopardy. Charred jaguar carcasses now litter the ground, along with burned alligator-like caimans and fallen birds.”

The Arctic Circle, too, is suffering the effects of climate change with wildfires raging in northeastern Russia. In the Yakutia region record amounts of greenhouse gases released by these fires are contributing to global warming. Remote and vast, Siberia presents additional challenges in battling these blazes fueled by abnormally high temperatures. It’s not just the treetops that are burning, the fires are reaching deep into the ground and thawing permafrost. Coupled with higher temperatures warming the permafrost, these ground fires burn hot for sustained periods thereby contributing to more warming that adds to the climate change crisis.

The grim numbers tallied all across the planet are yet another effective reminder from Mother Nature that what happens in one location has global consequences. Incremental temperature variations in the atmosphere and ocean impact climate. Even the smoke that drifts from fires far away can affect the quality of the air we breathe and sunshine units for vital crops.

While reviewing the trends for wildfires across the planet can be overwhelming, there are absolutely small steps all of us can take to both protect our homes, our societies and our collective future.

In a CBC News interview with Lori Daniels, University of British Columbia forestry professor and wildfire expert said that as we witness the fire seasons extending and fires growing larger “there has been a slow but steady acceptance that more needs to be done to protect homes and property... from wildfire.”

• Responsible forest management can play a role in which deadfall is cleared, trees are thinned and fire breaks are created, especially in potential interface regions.

• Controlled burns have a long history and if managed appropriately have an important role in reforestation and fire mitigation.

• Attention needs to be paid to building and retrofitting homes with more fire-resistant materials.

• Landscaping can be designed to be esthetically pleasing while fire resistant. Xeriscaping strives for that goal and reduces the need for watering, thereby preserving that critical resource.

• Learn your climate science through reputable journalism sites such as:

• The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ipcc.ch) the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change.

• Clinton Foundation (https://www.clintonfoundation.org/ourwork/clinton-climate-initiative)

• The Conversation (theconversation.com) that presents wellresearched articles.

• NASA Global Climate Change (https://climate.nasa.gov/ evidence/)

• Protect Our Winters Alliance (https://protectourwinters.ca/ science-alliance/)

• David Suzuki Foundation (https://davidsuzuki.org/what-youcan-do/what-is-climate-change/)

• Climate Watch (https://www.climatewatchdata.org/)

Meichen, a habitat restoration specialist, surveys the planting site in Oregon. Photography: One Tree Planted

By Meaghan Weeden, One Tree Planted

Meichen, a habitat restoration specialist, surveys the planting site in Oregon. Photography: One Tree Planted

By Meaghan Weeden, One Tree Planted

Look up “forest fires,” and the headlines will quickly demonstrate that fires have increased in frequency, severity, and size everywhere from California and Australia to British Columbia, the Amazon Rainforest, and even the Arctic Circle. The causes vary — from decades of fire suppression combined with climate change in California to unregulated slash and burn agriculture in the Amazon and Asia — but the effects are the same. And as the planet’s temperature continues to rise, so too does the risk for future fires.

In many ecosystems, fire plays an important role; in higherlatitude forests, it releases important nutrients into the soil and activates seeds. In tropical forests, local and indigenous communities have used controlled fires for centuries to clear land for agriculture. And from serotinous cones to fire-retardant bark and self-pruning responses, trees have come up with some pretty amazing adaptations in order to thrive in fire prone areas. But what we’re seeing today is at a scale of intensity that nature can’t keep up with. And according to the Food and Agriculture Organization, "each year wildfires destroy 6 to 14 million hectares of fire-sensitive forests worldwide, a rate of loss and degradation comparable to that of destructive logging and agricultural conversion."

When forest fires are relatively small, nature doesn't require intervention because seeds in the soil and natural regeneration from surrounding healthy trees will restock the ecosystem with new seedlings. But when burn scars are severe, or when the closest healthy trees are too far away to spread seeds, planting trees can help to catalyze the natural process so that forests grow once again. That’s where One Tree Planted, a reforestation nonprofit, steps in. During British Columbia’s rank six Hanceville Fire in 2017, the fire burned so hot that it destroyed the native seed stock and created its own weather system. As a result, around 30 percent of the forest wouldn’t have returned without help. Through a partnership with local First Nations communities, One Tree Planted, local contractors, and the British Columbia government’s Forest Carbon Initiative, over one million trees are being restored in this region.

So how do we know when to help and when to simply let nature take its course? For that we turn to fire ecology, or the study of the role of fire in ecosystems. Fire ecologists study the origins of fire, what influences its spread and intensity, best restoration practices, and what happens in nature after fires.

Once fires have stopped burning, environmental professionals will assess the scope of damage, asking questions like these:

• How many trees were killed?

• Was the seed stock destroyed?

• Is the land completely degraded?

• How is the local climate affected?

• Will the ecosystem be able to regenerate on its own?

Based on this and other criteria, they will determine if the forest can regenerate on its own, or if reforestation is necessary. But before tree planting can take place, a few things usually need to happen, such as:

• Removing extra debris like snags (dead trees) and brush that will provide fuel for future fires, while leaving some to provide wind protection and improve water retention for newly planted trees. Some wildlife species, like the black-backed woodpecker, also rely on snags to nest and forage the insects that are drawn to these recently killed trees.

• Assessing the health of the soil, the erosion risk, and remediating as needed. Fires can improve the nutrient profile of the soil by

breaking organic matter down into a usable form. But they also remove the most effective anchor (trees) holding everything together while also exposing the top layer of soil, which increases the risk of everything washing away and causing further damage downstream.

• Selecting the most beneficial tree species — for example, after the Hanceville fire in British Columbia, we included Trembling Aspen, which has a high water content and fewer flammable organic compounds, which can help slow the spread of future fires by creating a natural protective barrier.

It's important to know that in some ecosystems, fire has historically played an important role in shaping and maintaining the landscape. As a result, many native plant and animal species have developed incredible strategies to withstand blazes.

California’s giant sequoias depend on fire to reproduce: their serotinous cones, glued shut with pine resin, need fire to release the seeds inside. And their thick, fire retardant bark protects sensitive inner tissue, allowing it to withstand low-intensity surface fires. Other species with fire-aided dispersal strategies include jack pine, table mountain pine, and lodgepole pine (one of the first to grow after a fire). And many chaparral plants like coffeeberry, long sepal globemallow, and snow brush have coated seeds that require direct or indirect contact with intense heat and smoke to germinate.

Underneath the soil, there is a rich seed bank just waiting for the right opportunity. Species like Indian paintbrush, scarlet gilia, Oregon sunshine, and Washington lily are just a few examples of beautiful fireactivated wildflowers. Even fungi can benefit — and the experienced mushroom hunter knows that recent burn sites are the best place to find morels and boletes!

When gaps are opened in the canopy, some species, like pine grass, gain access to more sunlight. And when brush is cleared from the understory, creating gaps of bare soil, plants such as fireweed quickly colonize them with their lightweight, wind disseminated seeds. Sometimes, fire even changes the composition of the soil itself. When this happens, adaptive plants like Lupines multiply quickly. They typically grow in nitrogen-deficient soils where other plants cannot, but are able to “fix” or add nitrogen back into the soil over time.

Animals have some pretty amazing adaptations, too. In Australia, fire-foraging birds actively start fires to smoke out mammal and insect prey. These so-called fire hawks — black kites, whistling kites, and brown falcons — swipe burning sticks or grasses from fire areas (and sometimes even human cooking fires) and drop them into unburned areas to set them alight. When their prey emerges from the fire seeking safety, the fire hawks benefit.

They are, of course, a notable exception: most wildlife species will instead use intimate knowledge of their home range to outrun or fly away from fires. Those that aren’t able to flee quickly enough, like ground squirrels, frogs, and ants, will burrow deep underground or shelter under rocks and downed logs. Others will wait within nearby bodies of water, returning to consume newly released nutrients and rebuild their homes if possible once the fires have passed.”

No species is able to live in fire, but many have found ways to rise, phoenix-like, from the ashes. They’ve adapted over thousands of years to the fire regime — or, fire frequency, intensity, and fuel consumption patterns — unique to their home region.

But human activities like fire suppression, land degradation, and settlement are shifting the balance from normal, low-mid range fires that help to keep ecosystems in balance to high-intensity blazes that destroy everything in their path.

Fire prevention is the logical first step, but it can be tricky to get funding and public support for things like urban re-planning and prescribed burns. Still, progress is being made: foresters, planners, conservationists, and legislators are working hard to address the factors that make wildfires more frequent and widespread. And in light of this interdisciplinary approach, some feel cautiously optimistic about the future. They’re learning how to fix some of the mistakes from the past, and how to prepare for the future by improving forest management to ensure that the forests are healthier and more resilient.

The unfortunate reality is that fire seasons have been lengthening for years, skewing resources towards firefighting and making prevention difficult to implement. As Lenya Quinn-Davidson, Director of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council said, “we’ve been in a 100 year gap in fire in the landscape and the result of that is what we see today.” For example, California is now practically at risk yearround with little time to recover before the next one occurs. Because of this, restoration is often necessary.

There are a few different approaches to land restoration when it comes to trees. Reforestation is very helpful soon after a forest fire because invasive species can take over the land before native species have the opportunity to grow back. The result may not be a forest but a brush land of ecologically lower value, and one that's likely to burn again. This not only puts wildlife at risk, but also nearby communities because food and water supplies can be negatively affected. In this situation, planting ecologically appropriate seedlings gives nature the natural resources and time to heal itself.

And where reforestation occurs, it is conducted wisely in everything from the tree species chosen, to the distance between trees to the exact location where trees are being planted so that they don’t create the potential for future harm if another fire comes along in the area. Often, pioneer species that can tolerate poor conditions are introduced to help enrich the soil so that more sensitive native species can return naturally and gradually over time. By assisting in the regeneration process, we give native ecosystems a helping hand in restoring healthy, beautiful, and biodiverse forests.

One Tree Planted is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit on a mission to make it simple for anyone to help the environment by planting trees. Their projects span the globe and are done in partnership with local communities and knowledgeable experts to create an impact for nature, people, and wildlife. Reforestation helps to rebuild forests after fires and floods, provide jobs for social impact, and restore biodiversity. Many projects have overlapping objectives, creating a combination of benefits that contribute to the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at onetreeplanted.org.

PLANT A TREE TODAY TO CLEAN THE AIR WE BREATHE AND THE WATER WE DRINK, PROVIDE HABITAT FOR BIODIVERSITY, SUPPORT LOCAL COMMUNITIES, AND IMPROVE THE HEALTH OF OUR FORESTS.

VISIT ONETREEPLANTED.ORG

ONE DOLLAR. ONE TREE. ONE PLANET.

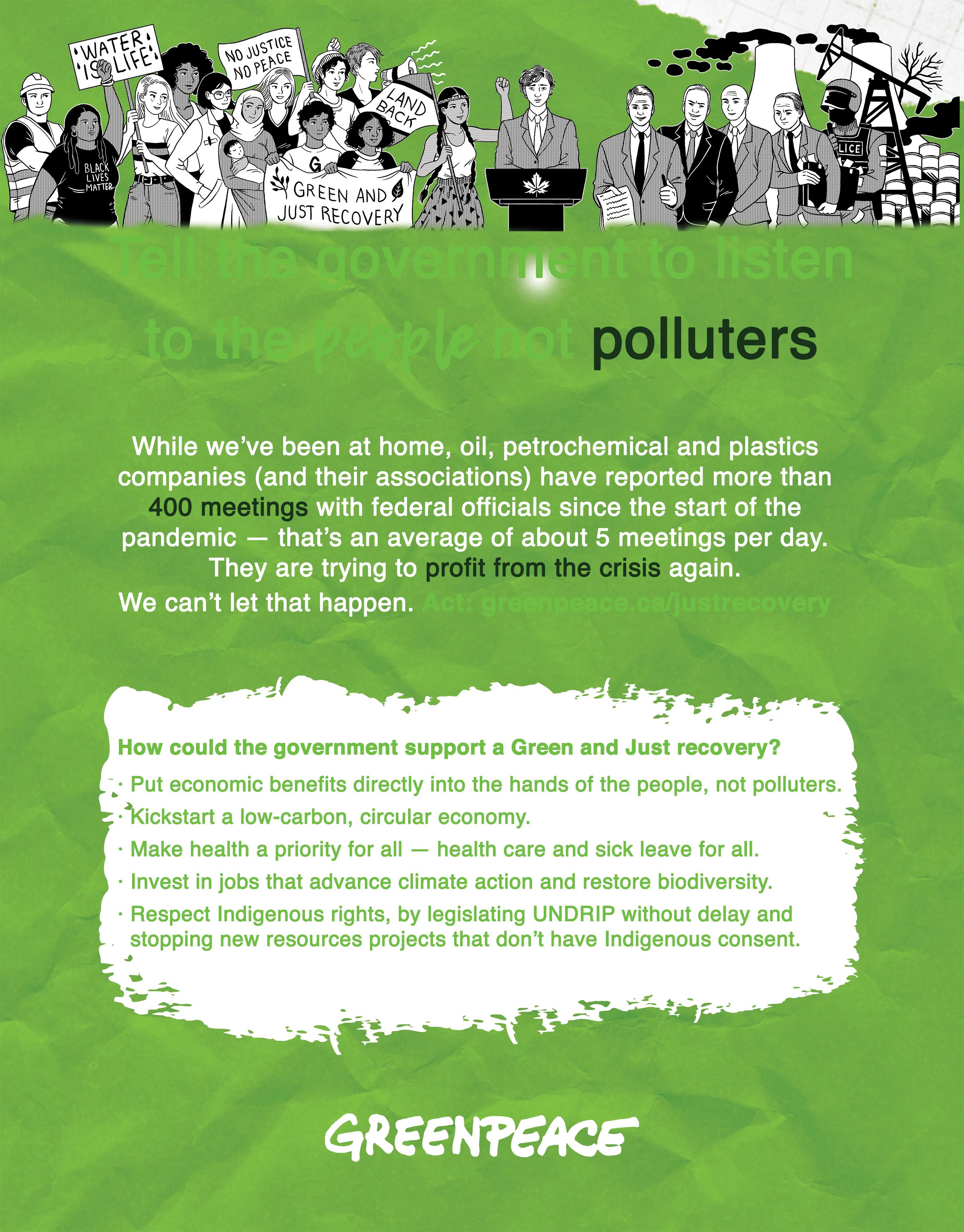

BY OLIVIER KÖLMEL, GREENPEACE CANADA

BY OLIVIER KÖLMEL, GREENPEACE CANADA

Growing up, the imagination that guided my paintbrush was inspired by the majestic landscapes of Europe and Canada. As a child, I loved hunting down the most delectable mushrooms, running in the mud of the undergrowth with my brothers, climbing trees in search of the canopy, or coming face-to-face with a deer or an anthill. My fondest memories are intimately linked to nature, to the forest. The great moments of adventure, the sense of discovery, the sense of freedom — all bring me back to these fortresses of nature.

Yet these places of healing and inspiration we call forests, are also places subject to harm, injustices, and atrocities. The destruction of nature is at the root of many disease outbreaks, wildlife decline, and is a driver of weather extremes such as forest fires. What we call development should more often than not be called conquest, as the companies behind mining, energy, forestry, and infrastructure projects push aside communities and wildlife in their quest for resources. Habitat loss is not only felt by woodland creatures. Human cultural heritage, identities, and traditional knowledge tied to these lands are also being eroded. Today’s economic model has become a threat to all life, a threat to our own species. Business as usual needs to change.

The restoration revolution is a vision for a new relationship between society, the land, and ourselves. It is an invitation to move our focus away from heavy resource extraction and toward a nature-based economy. To do that, we’ll need to shift our mindset, values, and activities.

Forests are home to an estimated 80 percent of all life on land, and are said to be capable of providing at least one-third of climatechange mitigation measures. The natural world provides the life-support systems we all depend on to survive. These “ecosystem services” (natural processes that benefit humans), include water purification, air pollutant filtration, climate regulation, flood control, pest management, pollination, and food security, to name a few. A restoration economy is an investment in these systems. However, it first starts with the protection of existing ecosystems.

While the Canadian government committed to protecting 30 percent of its lands, oceans, and freshwaters by 2030, it missed its 2020 target. Creating new green jobs at an ambitious scale can help achieve this urgent goal. If the Amazon forest is the lungs of the Earth, then Canada’s Boreal forest is our climate shield. The Boreal holds more carbon than all tropical forests combined. Protecting forests so they can grow to their full age is also a cost-effective approach to climate mitigation and reversing biodiversity decline. Scientists can also use these living laboratories to better understand how nature is adapting over time.

Protection, it should be noted, is not about excluding people from low-impact, sustainable use of forests. Protection must be centred on local communities and Indigenous rights, access, and knowledge. Considering that some of the richest and most biodiverse lands left in the world are on Indigenous territories, Indigenous-led conservation and stewardship is critical in meeting protection targets; including expanding Guardians programs, Indigenous land and marine plans, and Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) across Canada.

Restoration can take on many forms: reforestation and reclamation of degraded soils, land decontamination, restoration of peatlands, seagrass beds, and riverbanks. However, it should be noted that restoration is not an effort to recreate a past state, but to re-establish the evolutionary trajectories of disrupted ecosystems. In essence, it is moving past the simple act of planting trees, but ensuring we are rebuilding a self-sufficient and life giving forest ecosystem.

In addition to protection measures that protect forests as they are, restoring deforested, degraded and contaminated lands offers the most cost-effective opportunity to mitigate climate change and boost biodiversity. Connecting fragmented forests through ‘green corridors’ is another way restoration can help expand ecosystems. While restoring nature currently receives one percent of global climate financing, a recent study in the journal Nature indicates its potential can ‘prevent about 70 percent of predicted species extinctions’.

Think about it in everyday banking terms: while protection and conservation measures result in predictable yet immediate benefits, like a savings account, ecosystem restoration is more like a long-term investment. Canadian National Parks, for example, bring in six dollars for every dollar spent, while restoring natural ecosystems can bring in nine dollars in benefits for every dollar spent. Together, they provide greater insurance, prosperity and well-being.

Cities also need to rethink their landscapes to create healthier, greener environments that are accessible to people from all walks of life. By investing in jobs restoring urban canopies, creating parks, community gardens, and food forests - with a focus on the communities most in need - cities can improve air quality, the physical and mental health of their populations, and address food security issues. In some areas of the country, for example, cities will need to review their bylaws to allow citizens to grow food in their front yards and allow native plant species to take over ‘immaculate’ lawns. This, in turn, will attract birds, butterflies and other pollinators. It can also help reduce the use of lawn fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation, while cutting back on municipal costs for stormwater management, and treatment.

Recent reports and studies have emphasized that investing in “naturebased solutions” is a key fiscal policy option that offers high economic benefits and positive climate impacts. Some researchers estimate the global value of a restoration economy at $25 billion per year. The World Economic Forum puts the overall global value of nature-positive solutions at $10 trillion.

Governments can support economic recovery from COVID-19, and long term resilience by directly employing and funding naturebased jobs — jobs rebuilding shorelines, replanting native tree species, removing invasive species, restoring fish habitat, recovering abandoned or polluting fishing gear, upgrading existing conservation sites, stewarding lands, and carrying out data collection and monitoring. Other opportunities include jobs in regenerative agriculture, seed banks, integrating trees among crops (agroforestry), and restoring wetlands around existing farmlands. Adapting infrastructure to allow a continuous path for wildlife to roam freely also opens the door to engineering and construction jobs around restoration. The opportunities are endless.

A green and just recovery means leaving no one behind, and transitioning to a restoration economy holds up the same principle. This means empowering communities to make an equitable shift to more diversified, sustainable, and job-generating opportunities (instead of focusing on mining, forestry, or fossil fuels). This can take the form of training in Indigenous and single-industry communities, investing in the research and development of non-timber forest products (e.g.,mushrooms, berries, herbal teas, tree nut flour), exploring new uses for abandoned mills, ecosystem management, and overall help for diversifying local economies.

A study of strict ecological restoration work in the United States suggests this emerging sector employs “more than the coal, mining, logging and steel industries altogether.” Looking at the province of Alberta, the thousands of orphaned oil and gas wells are increasingly becoming a concern, and desperately calling for restoration jobs. These abandoned mines and wells are full of pollutants, and must be decontaminated in order to restore a healthy ecosystem.

Developing Indigenous-led conservation area planning and stewardship programs is a great model for public funding and job creation. But this only works if we holistically integrate Indigenous rights, laws, knowledge, and treaties with adequate funding and nation-to-nation relationships to guide land planning decision-making. This is an essential part of our collective journey towards reconciliation. The restoration revolution is not all about the economy, it is also about restoring respectful relationships.

The pandemic may have brought the world to a halt, but in many ways it brought us closer together. For many, it has also restored an appreciation for the outdoors. In Michel Le Van Quyen’s book, Cerveau et Silence, he points to different studies that highlight how contact with nature can bring about multiple health benefits. For example, patients in hospital rooms facing a natural landscape have shown to recover faster

from surgery, require fewer painkillers, and go home, on average, a day earlier. A short walk in nature has shown to significantly reduce depression levels in 71 percent of hikers sampled. Further studies show the benefits of longer walks or ‘forest bathing’ on heart rate, blood pressure, and the immune system. What is even more striking is that after only two days of walking in nature, the biological benefits persist for about a month. In ensuring we all have access to nature, by definition this could help relieve pressure on our health care systems. The impacts of preventative medicine related to 'forest bathing' is something governments and businesses should factor into their budgets and programs.

Another important reason to nurture nature is that our forests are also our pharmacies. The World Economic Forum states that “25 percent of drugs used in modern medicine are derived from rainforest plants while 70 percent of cancer drugs are natural or synthetic products inspired by nature.” Aspirin, for example, is extracted from the wonderful willow tree. What other treasures are hiding in our forests? Preserving biodiversity is key to finding out.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unforgettable reminder that our health, livelihoods, and well-being are intrinsically linked to the health of nature. Investing in nature is an investment in our resilience and future.

As governments around the world plan and budget for a long-term economic recovery from the pandemic-triggered recession, Greenpeace is urging Prime Minister Trudeau to make unprecedented investments in ‘nature jobs’ that will protect Canada’s carbon stores and restore degraded natural infrastructure.

Take action now and join the restoration revolution by asking our leaders to invest $10 billion to create at least 100,000 nature-based jobs in the upcoming budget.

Let’s put building a restoration economy at the heart of the recovery plans and build a new kind of economy. Let’s protect what protects us!

LEFT & BELOW: Boreal ForestS - Montagnes Blanches, Quebec.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Markus Mauthe/GREENPEACE.

By Cassie Pearse

By Cassie Pearse

Sometimes one comes across an idea that is so simple that we have to wonder why it hasn’t been clear to everyone forever. It should be so obvious to see that using paper made from trees is a waste of valuable resources. We are the ones who are responsible for our planet and our future and we know, without a shadow of a doubt, the role that trees play in keeping our planet healthy yet we continue to treat them as if they are an expendable, low-value, resource.

I knew all this yet I’d never seriously considered the alternatives until I began working with Saving Earth Magazine. Sure, I buy recycled paper for my personal printing, I have banned gift wrapping in my home and I try to stop my own family from wasting paper, but a serious, industrial alternative? Shamefully, simply not in my mind.

Enter Social Print Paper, a Canadian company, that offers businesses and individuals an agripaper alternative that is not only sustain-

able but also affordable and of high quality. The company’s tagline is, “the best alternative to not printing” and that’s exactly it. I spoke with Minto Roy, Managing Partner of Social Print Paper, to learn more about their product and why he believes it is a smart environmental choice for protecting our planet’s trees.

Our most observant readers may have noticed that Saving Earth Magazine is printed on sugar sheet paper. That is, paper made from bagasse, the residue waste of sugar cane, rather than the traditional treepulp paper. The only reason a reader holding this magazine in her/his hands would ever know that this isn’t traditional paper is that the publisher chooses to share this information. By touch or sight alone there is really no way to tell. And that is the first point Roy makes when we speak: that he saw the challenge as creating an alternative paper product without sacrificing either product quality or cost to the consumer. He told me he wanted to create an environmentally-friendly product that was at least equal to traditional paper in price and quality.

Roy, as a social entrepreneur (someone who uses business ideas to solve community or environmental issues), understands that people aren’t just one thing: he highlights that shrewd business leaders could well have strong desires to protect our planet’s resources and so set

about creating a product that answers both business and ethical needs. He firmly believes that most consumers want to spend in line with their values and that they will do so as long as a product isn’t expensive.

Agripaper provides an opportunity for all to reduce their carbon footprint and minimize deforestation without sacrificing paper quality, performance or price. Roy and his team are not the first to think of using other materials for paper. Indeed, there have been many different materials used in the past, in fact, wood-fibre paper is a relatively new development in the long history of paper.

Social Print Paper didn’t actually begin with sugar cane waste. Their first efforts were with wheat but after early experiments, they realized that sugar cane provides a better quality final product.

The Valle de Cauca in Colombia is home to 80 percent of all the country’s sugar cane industry and it’s where this sugar sheet paper is made. Sugar cane is a major part of the local economy and this valley provides the perfect climate to grow sugar cane all year round, allowing the production of more tons per hectare than elsewhere in the world. One crop can grow to maturity in under two years compared

to trees, which vary greatly depending on species, but on average take around 40 years .

The bagasse, or sugar cane waste, when not diverted into making sugar-sheet paper, sits in landfills unless it can be sent to commercial composting plants where it can decompose in 45-60 days. If burned, as so often can be the way with traditional landfill waste, it releases carcinogens into the atmosphere, further polluting the air that we breathe. Instead, thanks to innovative thinking, the waste is converted into a useful product that also helps to prevent deforestation.

I asked, like the good environmentalist that I am, about the impact of the paper having to travel from Cali to Vancouver, where Social Print Paper is based. Roy was quick to point out that the paper is made where the sugar cane waste is found and that it travels to Canada by sea, the lowest travel impact available. If the paper were made in Quebec and then transported by rail or air to Vancouver, while appearing to be more environmentally sound, the carbon footprint would actually be higher. And, of course, not forgetting Roy’s competitive urgency, the paper wouldn’t be as cheap if it were produced in Canada.

cost them more and doesn’t sacrifice quality or performance, would rather not use trees.”

Roy believes that we need a new language around sustainability. His message is that, “not only is it the right thing to [use environmentally friendly alternatives] but it’s the competitive thing to do, too”.

Roy tells me that in his experience when leaders learn about sugar sheet paper and the possibilities it offers for corporate tax levies they are all-in because, honestly, who is going to turn down the opportunity to do something good if it also saves money? He is all about reading the situation and that is his competitive urgency: he is a businessman who wants his product to be part of the environmental solution and he knows businesses are more likely to join him if it is in their best interests. “Businesses value sustainability” but as they pragmatically note on their website, “businesses shouldn’t have to jeopardize their bottom lines to collectively save forests and benefit climate change.”

When Roy was just starting out on his paper journey there was no chance of a supply chain within North America as the paper mills simply aren’t made to deal with sugar cane. In the future, when demand has grown as he hopes it will, there will be the opportunity to retrofit machines across North America at the behest of big business and government.

Roy is clear that he isn’t against the lumber industry. He acknowledges that we need trees to make long-life items such as furniture or housing but paper, a short-term product, simply doesn’t need to be made from such a valuable resource.

The paper can be used for personal printing at home as well as by industries. Social Print Paper works closely with big name printer companies such as Xerox, Canon, HP, and Ricoh to ensure the paper meets the highest of standards and requirements.

As an entrepreneur, Roy thinks not only outside the box but also about the box itself. The eco-friendly sugar sheet paper isn’t what he considers to be his innovation, the innovation is that he has an ecofriendly paper that is equal in quality to wood-fibre paper.

For many people, and for many years, the path to sustainability has fed on guilt and obligation but it doesn’t need to be this way. We need to do more to create not only interest but a strong financial incentive among business leaders to make a switch to more sustainable business practices. Roy told me he knows this needs to be a “values based decision for consumers.” He believes “that most consumers in the world, if they have a choice to use paper made from trees or paper made from agricultural fibre waste, if it doesn’t

Social Print offers eco savings reports to clients, detailing how much carbon dioxide they did not produce by swapping to sugar sheet paper. This can then be incorporated into their carbon reporting (in Canada), effectively reducing their carbon tax requirements. Using two boxes of sugar sheet paper rather than tree-fibre ‘regular’ paper, saves one tree from being felled for paper.

We discussed another surprising innovation that still wasn’t the material from which this paper is made: supply chain disruption. Generally, Roy explained, the traditional incumbents control the supply chains, whether we are talking oil and gas or paper, it’s all the same. The big boys control the supply chain and this means controlling consumer choice. Consumers see what they want them to see, there is the illusion of choice rather than true choice. But this can be challenged with smart advocacy and knowledge sharing.

Roy explained it thus: if a distributor talks to a CEO, she may well agree that switching her company from traditional paper to an environmentally ethical choice that also offers tax breaks is a smart move but if this decision doesn’t get transmitted throughout the company then there is a good chance it will never actually happen. “If you want change, you have to take the ideology and put in accountability and reporting”.

“Big businesses and governments got us into this [climate change]”, says Roy, “they have a responsibility to get us out of it, they need to make the change”.

Roy’s aim is to create a future where people say, “can you believe we used to make paper from trees?” Saving Earth Magazine stands proudly with this aim.

If you have a green business you’d like to see featured in Saving Earth Magazine email us at info@savingearthmagazine.com for more information.

Connect your students, faculty, and staff to a technology experience that drives innovation, communication and collaboration while doing good for the environment. Ricoh can help.

SERGIO IZQUIERDO

SERGIO IZQUIERDO

"Nothing was more shocking than the dark black fluids taking over the entire wetland of Manchón Guamuchal."

After two canceled flights due to bad weather, I was finally able to accomplish my assignment to fly over and document Manchón Guamuchal, Guatemala’s biggest wetland. Located on the south coast of Guatemala, this wetland was declared a RAMSAR site in 1995. This floodable area covers a total of 25 thousand hectares, of which 7,650 are covered with mangrove. It was the beginning of June when I found myself flying, doorless, in a small Cessna aircraft, with my pilot and friend, Clemente. We flew over the city of Guatemala, Lake Atitlán, passing by a few volcanoes, as well as over an important river called Ocosito. As we zigzagged the river we found big extensions of sugar cane farms, banana crops and huge African Palm plantations.

Suddenly these widespread fields ended, and we started to see a series of natural and artificial lagoons located in the Tamashan estate. This is an enormous property and in it is the Manchón Guamuchal wetland. I’ve known this place for a few years already, it being the most important stopping point for migrating birds to feed and rest, including birds that come from the Arctic and fly all the way to the austral region of South America. This turns out to be one of the most fascinating places to photograph different species of birds.

These natural and artificial lagoons I mention are used for shrimp farming, managed in a profitable and productive model that benefits, not only the owner of the farm – Guillermo Aguirre, a friend of mine – but also many people in the local fishing communities, such as Tres Cruces, Tilapa and El Chico.

As we approached this area, we noticed something wasn't right. We realized the lagoons, the mangrove and other water canals were dyed a disturbing black color. This abundant black fluid flowed all the way to the ocean. We were also able to notice other problems in the area, for instance, how there have been fires destroying different parts of the mangroves, and in several places, illegal invasions into the mangrove. Nevertheless, nothing was more shocking than the dark black fluids taking over the entire wetland. I couldn’t find any fishermen around, they were unable to fish of course, because of the water’s condition.

As soon as we landed I called my friend, Guillermo Aguirre, to ask him what was going on, and he said, “Man… You have no idea the amount of fish floating around, it looks as though they were tree leaves floating around the canals. They dumped their waste all over us (referring to their neighbours, the African Palm farmers)”. Three days after my flight, Guillermo and I organized a trip to his farm. We had to get special permits to be able to document the damage caused in the area. After a ten hour drive, we arrived at the shrimp lagoons and the first thing I noticed as I got out the car was a foul odor coming from the water. I saw a crab swimming backwards towards the surface, really struggling to get some oxygen along with other dead fish floating around the water.

I introduced myself to Victor Hernández, a community member, to see what he could tell me about what happened. Victor told me that a few days earlier, just after the first strong rain of the season, Finca Maravillas (the Palm industry next door to them) released all of this black substance into the water, killing all the fish in it. Luckily, the townspeople were able to save three out of the five lakes, by blocking the water entrances. Many extensive crop estates such as this one have created huge water deviations along the Ocosito River to benefit their plantations, affecting communities and the ecosystem as a consequence. Not only that, they dump their waste into that same river creating yet more massive contamination. Finca Maravillas is one of these estates.

Victor then mentioned that this same problem repeats itself every year, always after the first strong rain of the season, and it has been going on for decades. He said that before, Finca Maravillas (Agroaceites Industry, a subsidiary company of Agroamerica), used to dump their waste directly into the river, therefore killing all the fish in the river. Their waste would rapidly end up in the ocean. This water contamination would only last around two days and would not affect them as much (which is also not good at all, but there was no one to control this), but he said that lately they have deviated their waste directly into the lagoons, the same lagoons that connect with the mangrove. Guillermo Aguirre confirmed that the contamination on the lagoons has been an issue since his deceased father managed the farm. I later interviewed locals from different places and they said the same thing. They’re all dealing with the same problem and confirm all the facts.

Horrified by all of this, we took a boat ride for hours along the canals. The texture of the water was greasy, the colour was absolutely black and the smell was disturbing. We arrived at Tres Cruces, where we met up with Joel Archila, the community's “Cocode” (the chief of the community). He and his father shared exactly the same information as Victor, and they also told us how they are helpless and have no income because of this. They not only cannot fish, but they’re also left without a water source, since their water well has been contaminated as well.

This also becomes a health problem for the population in the area as they rely on this water source that is being contaminated, for their subsistence. Their food resources are being poisoned by the toxic waste in the water, and in the end, it all comes back to humans and the food chain. Add financial problems to the list of problems, since the villagers are fishermen, and no longer have any product to sell. This just aggravates economic difficulties caused by the current pandemic of COVID-19.

but also every bit of mangrove at every stage of growth.

Everyone I talked to pointed at the same farm causing the problem, but I wanted to see it with my own eyes, so I could be 100 percent sure about all of this. We continued our boat ride, looking for the place of origin, and with the help of a drone, we were able to locate it. First we saw images showing how there was brown looking water coming in from Ocosito River on one side, and black contaminated water coming in from the other side. So the contaminating black water was not coming in from the river, it appeared as though it came from the Tamashan farm. We then followed all of Tamashan’s canals until we finally reached the place where we saw the dark waste originating: Finca Maravillas’ sewage system. The saddest part was that during the whole boat ride along the mangroves, which lasted hours, we didn’t see any wildlife, no birds, nothing, only dead fish. We were witnessing a complete ecocide. There is no other crop that can pollute the area but the African palm from Agroaceites –I documented this ecocide by air and by land, and saw it with my own eyes, the dark waste coming out of their property.