Find your path to meaningful work.

Work in environment, sustainability, climate action.

Photo by Kevin Wolf on Unsplash

Find your path to meaningful work.

Work in environment, sustainability, climate action.

Photo by Kevin Wolf on Unsplash

For the last two years, I have been educating myself and readers about plastic pollution in our oceans. The situation is grave. And although there has been a lot of chatter among governments about “cleaning up” our single-use plastic problem, the only real action I have seen from them thus far is a ban on plastic bags and straws.

In December 2021, the Government of Canada decided to move forward with a comprehensive plan called the Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations to address plastic pollution. The draft regulation touted by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, the Honourable Steven Guilbeault, and the Minister of Health, the Honourable Jean-Yves Duclos, prohibits the manufacture, import, and sale of certain single-use plastics, including checkout bags, plastic cutlery, foodservice plastic ware, stir sticks, plastic ring carriers, and straws. According to the Government of Canada, banning these items will prevent more than 23,000 tonnes of plastic pollution from entering the environment over a ten-year period.

Saving Earth Magazine

The government also plans to ensure that all new plastic packaging in Canada contains at least 50 percent recycled materials by 2030, by achieving a recycling target of 90 percent.

I don’t think the 90 percent recycling goal is realistic. Let’s face it: we have been trying to recycle for decades now, and it has, for the most part, failed.

While the Government of Canada works to undertake firm action on the subject singleuse plastics, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) is also stepping up to the challenge by proposing a global treaty to combat plastic pollution.

Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Programme, stated, “Over the last week, we have seen tremendous progress on negotiations towards an internationally legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution. I have complete faith that once endorsed by the Assembly, we will have something truly historic on our hands.”

The first session of the UN Environment Assembly was held online February 22 and 23, while an in-person session took place in Nairobi from February 28 to March 2. Here, the ministers of environment and representatives from United Nations member countries convened to discuss a binding global treaty to curb plastic pollution. The conference was followed by a special session on March 3 and 4 on “Strengthening UNEP for the Implementation of the Environmental Dimension of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

While I acknowledge the efforts of global organizations like the United Nations, one thought crosses my mind: Problems linked to climate, health, and environment continue to inch towards global governance. While, yes, these are global problems, aren’t most of these problems caused by corporations looking to better their bottom line? Is it not all about profit? As we continue to dance around with solutions like recycling instead of putting the onus on those responsible for the mess we are in, the reality of the situation is that companies such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi Co, Nestle, and Unilever are responsible for more than half a million tonnes of plastic pollution annually. The solution seems very simple to me.

Can we all just agree to stop the manufacturing of single-use, petroleum-based plastics and replace them with bioplastics or other packaging solutions, even if it hurts the bottom line of these huge corporations?

Wishing you all the very best,

Teena ClipstonISSUE #7 - 2022

PUBLISHED BY Saving Earth

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Teena Clipston

SENIOR EDITOR Cassie Pearse

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Kirby

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Carolyn Rapanos

GRAPHIC DESIGN Cassandra Redding

ADVERTISING Teena Clipston

CONTRIBUTORS

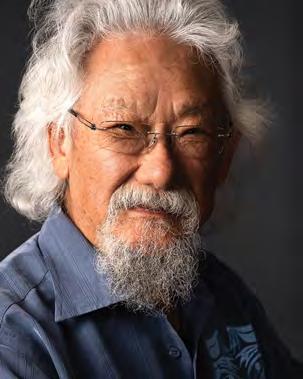

Erin Blondeau, Roslyne Buchanan, K ayla Bruce, Teena Clipston, Sergio Izquierdo, Sarah King, Rhonda Lee McIsaac, Ruth Linsky, Helena Mcshane, Shayne Meechan, Jodi Mossup, Cordelia Newlin de Rojas, Dayanne Raffoul, David Suzuki, Natasha Tucker

PRINTING

Royal Printers

DISTRIBUTION

Magazines Canada & Royal Printers

COVER PHOTO

Placebo365

Saving Earth Magazine has made every effort to make sure that its content is accurate on the date of publication. The opinions expressed in the articles are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the publisher or editor. Information contained in the magazine has been obtained by the authors from sources believed to be reliable. You may email us at Saving Earth Magazine for source information. Saving Earth Magazine, its publisher, editor, and its authors are not responsible for any errors, omissions, or claims for damages, and accept no liability for any loss or damage of any kind. The published material, advertising, advertorials, editorials, and all other content is published in good faith.

©Copyright 2021 Saving Earth. All rights reserved. Saving Earth Magazine is fully protected by copyright law and nothing herein can be reproduced wholly or in part without written consent.

PRINTED IN CANADA

savingearthmagazine.com

info@savingearthmagazine.com

Phone: 250-754-1599

facebook.com/savingearthmag

Instagram: @savingearthmag

ISSN 2563-3139 (Print)

ISSN 2563-3147 (Online)

Library and Archives Canada, Government of Canada

PRINTED ON 100% Forest Free Paper

SUGAR SHEET

By Rhonda Lee McIsaac

By Rhonda Lee McIsaac

Sphagnum moss wraps itself around a ridged black plastic pipe overlooking the sunny beach on Burnaby Island’s eastern shore south of Juan Perez Inlet and north of Poole Inlet. Gloved hands reach for the pipe, ripping it off its soft bed. A deep indent left on the moss after removing the pipe shows that it was sitting there a while after rolling or blowing in on a high tide. This persistent solid material does not belong on the shores of Haida Gwaii, and crews are working to remove marine debris off kilometres of shoreline. The plastic pipe is tossed into a waiting white super sack.

James and Shawn Cowpar, Haida Style Expeditions owners, selected youth from 300 applications. Youth ranged from their late teens to mid-20s. All were familiar with each other, having grown up on Haida Gwaii. Most had never been in Gwaii Haanas while others had attended Swan Bay Rediscovery. The Swan Bay Rediscovery has a long history of providing cultural stewardship camps for youth ages 10–18 at Swan Bay.

William Gravelle, a Haida citizen, had been down to Gwaii Haanas but not to Swan Bay. “I wanted to spend a week in Gwaii Haanas and get the opportunity to explore the beaches and to clean the marine debris,” he says.

A central factor in the success of the expedition was the preparation of youth for the adverse weather. While they were soaked by persistent rains, they had on wool and layers to insulate themselves. The zodiac, with its open seats and speed of travel through the wet weather and high waves, took its toll on their bodies. Run-ins with trees, slips, trips, and falls while on shore or loading full and heavy sacks onto the deck of the landing craft or the zodiac was exhausting. Sweat spilled from their brows while yarding heavy items down rocky shorelines. Sore muscles and cold did bring some mild cramps and aches. Over the week, boat captains and crew leads repeatedly addressed safety and hydration. There were barely any complaints, only weary smiles at day’s end.

Southwest and southeast storms with winds up to 45 knots pummelled the southern end of Gwaii Haanas. Staying in three damp, unheated, and breezy longhouses all week meant that the long house style cook’s cabin was the hub of activity. The wood stove heat dried soaked gear and became a cozy lounge area after a long and arduous day on the water and shorelines. Storm bound, the crew kept busy hauling wood and water from the creek and even gathering rainwater. Others took part in food preparation, dishes, sweeping, sanitizing, and maintaining their longhouses and the Phoenix composting toilets. As the stars and moon came out through the heavy clouds, the group sat around the big table eating, playing games, reading by the fire, or stacking cards, discussing macabre and mundane topics filled with lots of laughter. Others over the week helped with boats, gas, and even watching with concern as the captains were offshore gassing or tying up the boats during heavy seas and winds. All were growing their marine skills and outdoor leadership skills through the stormy week. Only two days during the week were clear, complete with a double rainbow.

“It humbled me being out there,” says Elin Hilgemann, a Daajing Gids Queen Charlotte resident who has never been to Gwaii Haanas until this trip. “The presence of the old-growth forests and kind people of all ages and ways was really remarkable.

“The trip confirms all the years of remarks about just how magical it is down there. It was also humbling because it was hard work, and I had forgotten just how capable this body of mine really is. It felt gratifying, more than depressing, to pick up garbage on the beaches there. That may sound counter-intuitive, but I see how far we have come with our ways of consumerism, and I think this is just the start of many years of cleanups.”

Fried bread Indian tacos were eagerly crammed into ravenous and appreciative faces for the best meal of the trip. “It was a huge pleasure cooking,” says Eugene Davidson Sr, a long-time fisherman and good-humoured cook. No deer or halibut were harvested for food and ceremony purposes on this trip, despite the drop line being tangled when pulled up and the sighting of six bucks over the week, largely due to the adverse weather conditions.

The final dreary day was nerve-wracking as southerly winds threatened to derail plans to go home. As the winds died down at daybreak, the captains called the teams to pack up and make a break for home. Travelling on the inside from Skincuttle through Burnaby Narrows and up through Burnaby Strait, and up through Juan Perez, through Shuttle Pass up to Darwin Sound, and out Logan Inlet, passing Porter and Hemming Head into Selwyn Inlet and in through Louise Narrows to Cumshewa Inlet, the team arrived at Moresby Camp where the vessels and crew were hauled out soaking wet and cold from the two-and-a-halfhour ride through rain and increasing winds. A fleet of trucks carried the exhausted crew home to Daajing Giids Queen Charlotte and Hlgaagilda Skidegate on Graham Island.

“I felt good returning home,” says William Gravelle, who is “ready to go back out whenever the opportunity comes up.”

Hilgemann hopes that every person on Haida Gwaii gets the opportunity to be a part of this important work because it is such a special place.

“I learned so much about Haida culture and history that I didn’t know,” she says about the social benefits of working alongside other local youth all working to make little dent in the very big single-use plastics problem.

The crew was assigned to clear Benjamin Point to Windy Bay for the length of the project. Other local marine operators have been assigned areas to access by boat, helicopter, and truck with crew

who work local beaches and accessible shorelines. Black, hard plastic dragger balls; weathered, hard, compressed plastic fishing net buoys; large fishing tow ropes; polystyrene; various types of plastic, single-use bottles; and even household appliances damage sensitive habitats. Derelict fishing line and rope and even remnants of nets are also carried off the beaches and stuffed into 20 super sacks over a seven-day period. On this trip, we covered Carpenter Bay, Collison Bay, Ikeada Cove, and a bit of Scutter Point with more day trips to complete before the end of the initiative.

The stay at ‘Laanas Dagang.a Swan Bay Rediscovery Camp located within Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site on the south end of Haida Gwaii, was necessary for safety and for ease of transporting crews to their work sites on two vessels. While cold and wet, the team was successful in their efforts to rid the shorelines of debris.

The largest marine debris initiative began in early October and will run through January 2022. The initiative is expected to clean up approximately 400 kilometres of shoreline on Haida Gwaii. This special youth trip met and exceeded expectations for the number super sacks stuffed with marine debris over such a short time. The sacks were left above the high tide mark at ‘Laanas Dagang.a Swan Bay. Part of the contract will be to bring those super sacks back to the sorting and recycling site north of Miller Creek on Highway 16 North to be sorted and weighed. The gross tonnage will be revealed when the initiative closes.

Haida Style Expeditions team included eight youth under 30 years of age from Haida Gwaii: Allegra van Heek, Roan Collison, Anton Amero, Evan White, Noah Borrowman, Linden McDiarmid, Elin Hilgemann, and William Gravelle. Also part of the team were Shawn Cowpar, Robert Russ, James Williams, Jeanette Yaroshuk, and myself. L ong-term friendships spring from shared labour and accommodations over a cold and stormy week. We hope that 200 tonnes of marine debris will be removed from the shorelines of Haida territory.

Partners in the Marine Debris Initiative include Council of the Haida Nation, Xaayda Gwaay.yaay Tang.Gwan Tll Skunxa HlGang. gulxa XaaydaGaay Haida Gwaii Clean Oceans Working Group, and the Misty Isles Economic Development Society with the financial support of the Province of British Columbia through the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy allocating $2.3 million dollars provided for approximately 146 local jobs.

For more information, please refer to the website www.mieds.ca/index.php/marine-debris-initiative Follow on Facebook m.facebook.com/misty.isles.ec.dev

Future funding for this initiative is undetermined at this time.

RIGHT: The winter water is as clear as it is cold in the Carpenter Bay estuary. The low tide hampered the ability of the boats to get all the way back to check the back end of the estuary.

Every time you drink from a plastic bottle, rip open a food package, or sip from a straw, do you wonder where it goes afterwards? Do you realize that much of it ends up in the oceans and on our beaches?

The youth are the future of Canada; therefore, it’s never been more important to ensure they are not only well educated on the issue of plastic pollution but also equipped to come up with solutions. In 2021, Plastic Oceans Canada launched its first Circular Economy Ambassador Program (CEAP), a voluntary program led by teachers that aims to teach youth about the widespread, harmful impacts of plastic pollution and what they can do about it while they clean up the beaches.

In the program’s first year, 243 students participated in beach cleanups within their communities, taking on the challenge of identifying, quantifying, and sorting waste with the goal of diverting their findings from landfills. Plastic Oceans Canada provided the teachers with resources that identified their municipal-specific waste management strategies as well as partners that process hard-to-recycle plastics. In addition to their data collection tasks, students were asked to speculate how the waste got to the beaches in the first place by identifying leakage points within their cleanup areas. The data collected by participants was added to Plastic Ocean Canada’s database that consolidates all the data from the cleanups across Canada to tell a story of what is happening from coast to coast. The story this data told was significant—we have a plastic problem.

Now, this may not come as a surprise, but over 50 percent of the items collected were composed partially or entirely of plastic material, where plastic pieces, cigarette butts, and food packaging were the most collected items. Aside from learning about the abundance of plastic pollution in our environment, one of the biggest goals of this program was to provide students with the opportunity to get thinking about how the waste is making its way into the environment and encouraging them to discuss the waste sources. These identified sources range from industries to individuals and poor waste management strategies (including those in areas that are heavily saturated with corporations that rely on single-use plastic and packaging).

Upon returning to the classroom, the students within the CEAP learned the importance of using and developing sustainable alternatives to reduce waste by reusing and repurposing materials. Students were given the opportunity to divert plastics that typically wouldn’t be recycled, such as mixed plastics or plastics that had degraded past the point of value, by sending them to local entrepreneurs that process these plastics into new products, such as 3D printing filament and construction bricks.

Ultimately, participants came out of this program with a well-rounded knowledge of why plastic pollution is a significant issue, what causes it, and solutions for future prevention.

If we continue to allow such enormous levels of plastic waste to enter the oceans, studies show that by 2050 they will contain more plastic than fish. Plastic is obviously a well-known pollutant with notorious negative impacts, such as entanglement of marine life, habitat destruction, and animals—both on land and in the oceans—ingesting it.

This leads to bioaccumulation of contaminants, causing risks to these animals and to humans as the contaminants return to us on our plates.

What can we do to prevent these issues?

First and foremost, promote a circular economy within your community. Within a circular economy, everything is reused, recycled, and rebuilt to be reinserted into the economy instead of trashing what we've used and creating entirely new products. For example, TerraCycle accepts cigarette waste and transforms them into plastic pallets, ashtrays, and benches. A circular economy prevents the production of waste, creates thousands of jobs, and is estimated to provide billions of dollars in revenue for countries like Canada.

There are ways that you can make a difference immediately, while advocating for a transition to a circular economy. The most important include:

• Refuse the unnecessary, such as single-use take-away containers.

• Inform yourself and others about the different recycling programs within your municipality.

• Recycle everything you can.

• Advocate for material/design change to prevent littering.

Your small actions can motivate others, creating a behavioural change domino effect, eventually reaching governmental officials who are able to concretize a circular economy within various communities. As Howard Zinn would say, “Small acts, multiplied by millions of people, can transform the world.” Let’s do it together!

The program is running again in 2022.

BY JODI MOSSUP

BY JODI MOSSUP

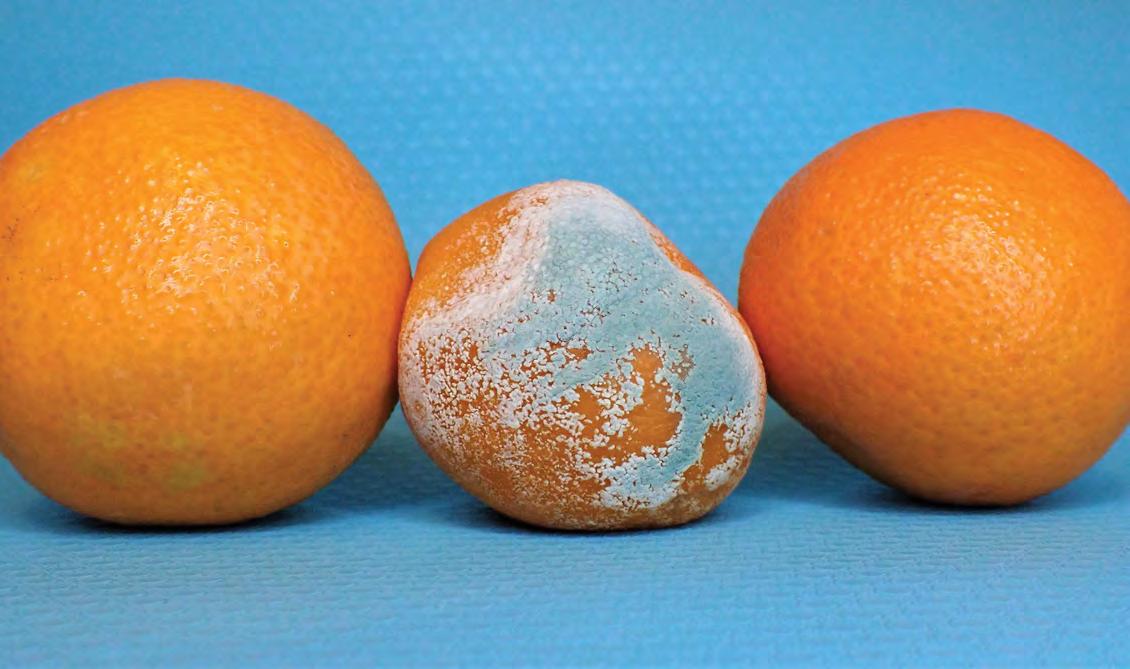

Oh, the love-hate relationship the world has with plastic. On the one hand, this amazing compositional material is durable, effective, and lightweight. It helps us protect much of our food from going to waste, it allows us to deliver goods more cost-effectively around the world, it is resilient to breakage, and it is so very convenient. On the other hand, its durability and resistance to decomposition are exactly what make it so problematic. Natural organisms have a very difficult time breaking down the synthetic chemical bonds in plastic, contributing to the tremendous problem of the material’s ubiquitous persistence. The fact that less than ten percent of our plastics are effectively recycled globally is shocking. The toxic compounds of plastic are released throughout the planet’s atmosphere, soil, and water cycles where they accumulate in biotic forms in our ecosystems. While the impacts and long-term implications of plastic pollution are not fully understood, they will be felt for thousands of years.

During the last few years, while sailing and playing in and around the Gulf Islands off the coast of Southern British Columbia, I have seen an accumulation of plastic debris scattered on the beaches and even pushed deeper into the forested shorelines. The debris includes plastic bottles, fishing ropes and netting, Styrofoam from docks and aquaculture farms, rubber tires, plastic bags, shoes, gloves, food packaging, and other household waste items. It’s hard to see it from a boat or even from the air. You see it when you walk along the water’s edge and look behind the logs, around the rocks, and in the trees. And then, you can no longer unsee it. It becomes Beautiful British Columbia’s dirty little secret.

There had to be something I could do. While working on my own ocean protection publication, I was introduced to Chloé Dubois of the Ocean Legacy Foundation (OLF). I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know both Chloé and her co-founder and partner, James Middleton, well over the last five years while doing what I could to assist OLF in its fight to clean and remove this debris and plastic waste from the ocean and scattered shorelines.

During 2021, British Columbia’s shores were cleaned of 425 tonnes of debris through the provincial government’s Clean Coast, Clean Waters (CCCW) program, which launched in 2021 and provides funding to organizations to carry out cleanup projects. The Ocean Legacy Foundation has been awarded assistance through this funding to work in British Columbia.

For the better part of a decade, OLF has been cleaning and diverting plastic pollution

that would have otherwise ended up in landfills and in the natural environment. Their efforts have included remote island and beach cleanups where they have spent weeks cleaning a small area. They opened a depot in Steveston Village in Richmond, BC, and in partnership with others have also opened depots in Powell River and Tofino, BC. These depots are used to store marine debris and Legacy equipment from the marine sector to divert waste and reduce oceanic plastic pollution. They provide a designated location for these materials to be properly contained and for selected items to be recycled. The usefulness of plastic cannot be denied, and the benefits of plastic are numerous. However, if we are to end the plastic pollution crisis, Dubois believes we cannot overlook the importance of product redesign, building adequate capture and processing capacity, mitigating policy measures, and the creation of best practices. OLF has developed its own emergency response program called EPIC, which is a platform that integrates Education, Policy, Infrastructure, and Cleanup. This program was designed to give plastic waste an economic value to stimulate the plastic circular economy and provide communities with the long-term tools they need to steward their environment by keeping plastic out of the oceans.

OLF recently realized one of these opportunities to give plastic an economic value with the introduction of its new product— Legacy Plastic™, the first commercially available 100 percent post-consumer plastic pellet in North America.

Plastic materials used in the Legacy pellet are from debris recovery operations, and they fall into three categories, which will all eventually have direct traceability using a blockchain system.

• Used marine gear: collected from fishing and aquaculture operations along the Pacific Coast, recovered at source or through Ocean Legacy depots.

• Shoreline plastic: materials found in various shoreline cleanup expeditions along the British Columbia shoreline led by Ocean Legacy and other partner organizations.

• Ocean recovered: plastic waste recovered from the ocean during underwater recovery operations.

Each batch of Legacy Plastic™ is tracked and will be traceable from its source, it comes with a unique story that can be shared and passed on to the consumer—a standout feature, for certain.

The various sources result in a range of resin types. All materials are cleaned, segregated, and processed using patent-pending technology

to ensure that the resins are of high quality for direct application in manufacturing. The resins processed through this technology are 100 percent polypropylene, high-density polyethylene, low-density polyethylene, and soon, nylon.

Legacy Plastic™ is a watershed in addressing the ocean plastic crisis.

“We recently started production at our new processing facility at the Steveston Harbour and are very excited to now be able to make recycled plastic pellets (Legacy Plastic™) from ocean, shoreline, and marine equipment materials,” Dubois says. “Legacy Plastic™ is now available for brands to incorporate into their products.”

With the introduction of Legacy Plastic™, companies now have an ethical plastic available for use in the development of their own products, creating a closed-loop system for these materials. “We are looking to partner with leading brands in the fight to address the ocean plastic crisis,” explains Gil Yaron, director of sales and marketing for Ocean Legacy.

By using Legacy Plastic™, companies become part of a market for recycled ocean plastic that will drive oceanic recovery and prevent used marine gear from making its way into the world’s oceans.

Some uses for recycled ocean plastics include running shoes, bathing suits, activewear, mats and rugs, blankets, outdoor furniture, backpacks, cups, and more. Opportunities for other products are innumerable. The recycled plastic pellets allow these companies to give life to this material that otherwise would have ended up in waste, in the environment, or causing other environmental harm. This prevents further unnecessary creation of virgin plastic and the additional extraction of oil for these types of products. It becomes a closed-loop system. We can’t fully get away from plastic, therefore, we must generate less of it. We must dispose of it properly and maximize its reuse.

Legacy Plastic won’t just sell its product to anyone. Licensing is offered only to companies with value-added products that foster closedloop thinking and do not perpetuate single-use applications. Ocean Legacy applies a set of 12 rigorous assessment criteria in determining appropriate applications for Legacy Plastic™ to help evaluate the circularity of the plastic items being produced. Recollection and recyclability are in this criterion and are considered when Ocean Legacy chooses a product or company with which it will partner. This set of criteria in choosing a partner has been a very important part of OLF’s story as an organization passionate about helping the environment. It is critical to ensure

that partner companies share the same values and are not just looking to cash in on the marketing story of the product. They must be equally passionate about being a catalyst to improving the environment and the health of the oceans.

In the early days of plastic recycling, it was a complicated process, and the resulting products were of inferior quality. However, this has begun to change. Technology has improved, our knowledge of synthetic materials has advanced, and recycled plastic has become increasingly competitive with virgin plastic in terms of quality, consistency, and availability. Each time plastic is recycled, the polymer chain grows shorter, so its quality decreases. The same piece of plastic can only be recycled two-three times before its quality decreases to the point where it can no longer be used and will then have to be discarded as waste. It’s not a perfect solution but it does help to decrease some of the additional extraction of petroleum needed to produce the material. OLF has entered the market with Legacy Plastic™ to create and supply a high-quality product to the market.

Legacy Plastic™ would not be possible without the partnerships and contributions of so many coastal communities who tirelessly clean Canada’s west coast environments. These include civil society groups, government, industry members, and Ocean Legacy’s own operations team.

I’ve had the opportunity to join a few remote cleanup expeditions, help sort debris at the drop-off center, and understand a little more about the waste found on the shorelines of British Columbia. I am forever grateful for the work that this organization has done and continues to do to keep our shorelines and planet healthy as they fight for policy change, create opportunities to divert waste from re-entering into our water systems, and allow for the re-imagining of a new life for this formidable material.

For more information about Legacy Plastic™ or any of Ocean Legacy’s programs, visit legacyplastic.ca or oceanlegacy.ca.

Ocean Plastic Pellets

Photo credit: Ocean Legacy Foundation.

Ocean Plastic Pellets

Photo credit: Ocean Legacy Foundation.

Sergio Izquierdo

Sergio Izquierdo

Caribbean Beaches on the Caribbean side of Guatemala.

Caribbean Beaches on the Caribbean side of Guatemala.

We call them “throwaway” plastics, but we never stop to consider what “away” really means. We have the false idea that we fulfill our mission of saving the planet by separating our waste and putting everything in the respective bins. More than 90 percent of plastic has never been recycled, and much of it can never be so. We live in a world where we buy, consume, and dispose without thinking. We are all submerged in something that we call “lifestyle”. All the plastic that has been created (and hasn’t been burned) is somewhere on the planet.

Thirteen thousand tons of plastic are dumped into the sea every year. This waste causes problems for animals, including obstruction of their respiratory tracts and intestines, entanglement, and, due to the toxic chemicals that plastic contains, reproductive problems and disease.

I am going to tell a story, one with many examples of how human consumption has a direct impact on our oceans, the largest producers of oxygen on the planet. Without blue, there is no green.

It’s May 17, 2021, and in the heat and extreme humidity, we depart from Lake Izabal in the north of Guatemala as part of expedition Plasticsphere, led by our NGO, Rescue the Planet. Onboard the ship there is a crew with scientists, environmentalists, journalists, filmmakers, and sailors, all with the same purpose—to skim the ocean surface for microplastic samples and to document the environmental, social, and political impacts of plastic pollution.

Navigating from Lake Izabal, we passed through the Rio Dulce Canyon, arriving in Livingston where we passed through customs and departed for Honduras. As we left, everybody excited for the work ahead, we threw our trawl to carry out the first microplastics sampling in the Punta Manabique Reserve. This reserve is an important place where a small manatee concentration is found.

Plastic does not biodegrade. It photodegrades, which means that with the sun (and weather conditions) it fragments into pieces less than 5 mm in size called microplastics. Microplastics can get so small that even plankton feed on them. They are then ingested by fish, and reach us through the food chain.

After four kilometres, we lifted that first trawl, and the results were devastatingly impressive. According to the results of the later analysis, there are more than 330,000 microplastic particles per square kilometre in this reserve. This is the equivalent of having at least one microplastic particle for every three square metres. The chance of fish ingesting microplastics is very high.

Heading to our next point of interest, the mouth of the Motagua River on the border between Guatemala and Honduras, we were followed by a school of dolphins (more than 100,000 marine mammals die each year by plastic pollution) for more than an hour. We anchored near the shore and took a zodiac towards the beach.

The Motagua River originates in the department of Quiché, Guatemala, and flows for 487 kilometers. Other rivers and streams connect to this river, carrying plastic waste from more than 90 municipalities, including waste from the main garbage dump in Guatemala City, the zone 3 landfill. This dumpsite receives more than 600 garbage trucks every day. Las Vacas River starts here and drags a large amount of plastic garbage from the landfill, connecting later to the Motagua River—an all too real example of how easily a city’s population and its garbage are connected to the oceans.

The government’s demagoguery, corruption, and patronage with the plastic industry prevents finding solutions at the source of the problem. Meanwhile, both the plastic industry and the government promote cam-

paigns solely blaming the consumer, campaigns such as “your waste, your responsibility”, removing themselves from the equation. This formula is replicated all over the world. Let’s remember that water bottlers do not produce water; they produce bottles (more than a million plastic bottles are produced per minute worldwide).

The Guatemalan government, with the help from the plastic industry, has also promoted the installation of “bio-fences”, which are practically fences that float across in the river and retain the plastic that floats in the current. These bio-fences have been placed at the end of the Motagua River, in the Quetzalito community. The government has spent millions of dollars on these fences, but over time it has been shown that the amount of plastic they trap is negligible, and they completely lack functionality when the rainy season begins. When the Motagua River rises, it carries more plastic from the communities along its banks, making this fence totally inefficient, and allowing everything to pass by. Biofences (just like beach cleaning and recycling campaigns) are projects funded by the plastic industry to anesthetize our consciences, make us feel part of the solution, keep us consuming their products, and avoiding seeking real solutions.

The Mesoamerican Reef, the second largest in the world after the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, touches the coasts of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras. Guatemala has the least amount of area; however, it’s the country that pollutes the most, due to the polluted Motagua River, which flows into the Caribbean.

After walking along these beaches and witnessing the chaotic and sad scenery that reaches as far as the horizon, we embarked again and headed towards Omoa, a town on the Honduran coast greatly impacted by the amount of plastic thrown by the Motagua River.

When we arrived at the dock, Mayor Ricardo Alvarado was there to welcome us. He told us that this problem is increasing every year and that Guatemala’s contribution to help them is zero. Therefore, the municipality must invest large amounts of money for daily beach cleanups to keep the local tourism industry alive. He said he felt that they must deal with the pollution that is not theirs, and due to all the money spent, there was no money left for the construction of schools and health centres.

This problem increases each rainy season, and now the Honduran authorities are considering lodging an international lawsuit against Guatemala for damages it feels is Guatemala’s responsibility.

We also met with the president of the Omoa Chamber of Tourism, Maribel de Umaña, who said that fishermen are struggling to earn enough to support their families since there are fewer fish because of the increasing plastic pollution. Local restaurants are having to buy fish from the Pacific coast, and many local fishermen are joining the migrant caravans heading to the United States in search of a better future. This is tearing families apart.

This makes me think about the fact that I, in my hometown of Guatemala City, make small decisions that contribute to people migrating because they lack education or health care. My choice of whether to buy soda in a returnable glass bottle or a plastic bottle can have a huge impact on other people.

We are not only connected to our oceans, but to people from other parts of the world. This butterfly effect occurs all over the world. Rich countries with high waste collection rates used to export their plastic waste to Asian countries, where most of it was not actually recycled. Most of this plastic ended up in the environment in the other side of the world, affecting ecosystems and communities.

Microplastic beach survey in Roatán, Honduras.

Microplastic beach survey in Roatán, Honduras.

We continued our expedition to Puerto Cortés (near Omoa), where one biologist of the crew, Zara Zúniga, has carried out a study on the microplastic presence in one of the most consumed fish species in the area, the Yellowtail fish. The study she carried out concluded that 60 percent of this species have plastic in their stomachs. Plastic pollution in the seas is more abundant than we could ever imagine.

Leaving Puerto Cortés, on our way to Cayitos de Utila, which is located southwest from Utila Island, we continued with our trawling to obtain microplastic samples. Every sample collected contained microplastics.

In Cayitos, we did our first dive. When diving in these pristine places, it seems like you are swimming in an aquarium because of the crystal-clear water. The corals were beautiful; however, as we continued diving down, we found more and more plastic tangled in the coral and on the seabed. According to a 2005 UN study, it is estimated that 15 percent of plastic pollution floats in the sea, another 15 percent floats in the water column, and the remaining 70 percent lies on the seabed. We continued diving down, and just when we reached a flat sandy area, we saw the seabed all covered with plastic, mostly single-use plastic items, such as bottles and food packaging.

Corals are one of the most bio-diverse ecosystems in the world and are home to a quarter of marine life. Coastal marine communities depend on fishing, and fishing activities in the region depend on the coral reefs. The main threat to coral reefs is climate change, yet many are already dying from diseases and viruses. Studies show that corals are between 4 and 89 percent more likely to contract diseases when they are in contact with plastic.

After our dive, we headed for the main dock of Utila, where we interviewed teacher Yoselin Turcios. She told us that she frequently does beach survey activities and beach cleanups with school students. She said that the brands identified on the surveys were the same as those detected worldwide, starting with Coca-Cola, Pepsi Cola, and Nestlé. She said that there is no sense in continuing beach cleanups forever if the problem is not solved at the source, by rejecting single-use plastic. She emphasized the importance of teaching the famous Rs in order—Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle. Recycling is important, but it is the last option for sustainability.

As the day became night, we returned to our boat where the captain gave us the bad news that the vessel had a leak and needed repairing. The next morning, just to make things worse, a heavy storm was approaching the island. Suddenly, we were told that a ferry was departing for Roatán Island (our last stop before returning home). We quickly packed our things and got the ferry, leaving our ship behind.

Upon our arrival in Roatán Island—an island of two municipalities, Roatán and José Santos Guardiola—we were greeted by Fernanda Lozano, head of the Municipal Environmental Unit of the municipality of Roatán. She told us that they had succeeded not only in banning straws, foam, and plastic bags but also plastic bottles. This is a great achievement, making transnational companies return to reusable packaging, such as glass bottles, and showing that change can be done without affecting consumption. However, to be fully effective, this approach must be replicated the other bay islands and the countries affecting the Mesoamerican Reef.

Before heading back, we did our last dives. We did a shark dive, an incredible experience witnessing the majesty of nature with 20 reef sharks surrounding us. Three hours later and five kilometres away, we did another dive, where we found the same polluted scenario as in Cayitos de Utila, with large amounts of plastic on the seabed.

These and other experiences during the expedition only made me think about how we, from our homes, are affecting sharks, thousands of marine species, sea birds, and also people without even considering the health problems that plastic packaging can cause humans. As we began our 30-hour trip at sea back to Izabal to end our expedition, I considered how this should not be the end of an experience but the start of us seeking more solutions.

We need to reject single-use plastic.

BY SARAH KING

BY SARAH KING

When you think about plastic pollution, images of clogged waterways, littered beaches, or injured sea turtles may pop into your mind. From beach cleanups to reusable water bottles, people have channeled their concern into trying to do their part to tackle the problem and reduce their plastic use. The burden of the plastic waste and pollution crisis has largely been placed on the average citizen. But what about those who are creating it? What are they doing about it?

The short answer is, not much.

Every single day, plastic pollutes. Plastic enters different ecosystems via improper disposal, leakage during waste transport, plastic production, weather events, illegal dumping, overflowing public receptacles, down drains through sewer systems in the form of microplastics or microfibres, and even as particles through air and ocean water currents to new areas. Once in the environment, especially the oceans, it’s impossible to get it all out. Waves bring plastic to shore, but only a tiny fraction of what is going into the oceans each day.

For a long time, people have organized shoreline cleanups to address the debris that washes up in their communities or threatens habitats. People will take note of the types of trash they find, try to dispose of it as best they can, and repeat the same exercise as needed. These efforts were the first to draw attention to the increased presence of everyday plastics like bags, bottles, and Styrofoam in marine environments.

In the last handful of years, with efforts from numerous organizations involved in the global Break Free from Plastic movement—including Greenpeace, concerned individuals, and community groups around the world—a new style of beach cleanup has emerged that not only focuses on collecting and identifying the types of pollution, but also uncovers who made the pollution in the first place. Known as brand audits, these plastic pollution investigations have revealed the companies largely responsible for this literal mess we find ourselves in.

For four years in a row, The Coca-Cola Company has been crowned the world’s top plastic polluter. In 2021, audit results from 45 countries were combined to reveal a total of almost 20,000 Coca-Cola branded products collected. PepsiCo (which owns several brands, including Lays, Doritos, and Tropicana) and Unilever (which owns over 400 brands, including Dove, Q-Tips, Popsicle, and Lipton) got the second and third spots. The branded trash included bottles and caps, labels, and multilayered packaging, like wrappers, chip bags, and sachets.

These results are not surprising when you consider the scale of plastic packaging used by these companies. Single-use plastic packaging is the largest end use of virgin plastic globally. As some of the world’s largest users of single-use plastic packaging, giant, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies, like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé, Mondelēz, Danone, Unilever, Colgate Palmolive, Procter & Gamble, and Mars, are playing a key role in driving the demand for plastic and the expansion of plastic production globally. In 2020, Coca-Cola alone put 112 billion single-use plastic bottles onto the market. That’s one company contributing over 100 billion plastic items that are designed to be used just once and disposed of! That’s the business model that dominates the sector and overall market. With all the different types of companies around the world flooding the market with plastic every day, it’s no wonder that plastic pollution has been found in all corners of our natural environment.

In Canada, our plastic waste and pollution crisis is top of mind. The last brand audit conducted across Canada in 2019 revealed that Nestlé, Tim Hortons, and Starbucks were the top three plastic polluters. The CocaCola company was in the top five. Of the 240 companies identified in that audit, 39 percent belonged to the top five polluters. House brand-labelled

products by Canada’s major retailers, such as Sobeys, Costco, Walmart, and Loblaw, were also found among the polluting items.

The most commonly collected single-use plastic item categories were cigarette butts, bottles and caps, wrappers, cups and lids, and straws and stir sticks. Bags, cutlery, and other forms of packaging were also present at most locations. While the ranking of brands and collected items varied across audit sites, single-use plastic items and packaging overwhelmingly dominate the results.

Increasingly in Canada, plastic can be seen in public spaces, along highways, at iconic nature destinations, and even in remote locations. And that’s just the plastic we can see. The seafloor off our coasts, the soil that grows our food, the sand along our rivers, and the lakes that bring so much summer enjoyment all contain pieces of plastic, large and small. Because plastic breaks apart and doesn’t totally break down, it is basically a massive, spreading solid oil spill with no way to clean up.

About 99 percent of all plastic comes from fossil fuels. Oil or gas is refined to create the building blocks of the numerous types of plastics we encounter in our daily lives.

The world’s dependence on fossil fuels and the resulting emissions from fossil fuel production and combustion has pushed our planet’s climate into a state of emergency. As a fossil fuel product, plastic is part of this equation. From plastic production through to disposal, and even once it is pollution, plastic emits harmful greenhouse gases. The world’s top plastic polluter, The Coca-Cola Company, produced 2,981,421 metric tonnes of plastic in 2019, and this resulted in 14,907,105 metric tonnes of CO 2 emissions. And this doesn’t consider the emissions associated with disposal of its products or when they are in the environment, releasing emissions through the degradation process.

While big plastic producers and distributors have acknowledged that they need to address the plastic problem, their actions fail to reflect their massive contribution to the pollution and climate crises or signal that they are truly committed to a more sustainable and socially responsible product delivery model.

Companies representing 20 percent of all plastic packaging produced globally, including The Coca-Cola Company, PepsoCo, Nestlé, Unilever and other top polluters, have public commitments through the Ellen MacArthur Foundation Global Plastics Commitment to: eliminate problematic or unnecessary plastic packaging; support efforts towards making all packaging 100 percent reusable, recyclable, or compostable; ensure that at least 50 percent of plastic packaging is effectively recycled or composted; ensure an average of at least 30 percent recycled content across all plastic packaging (by weight); and set a reduction target on the use of virgin plastic.

While the commitments sound bold and applaudable at first glance, there is nuance that means the companies can keep producing and using plastic as their main packaging type. Most companies remain focused on improving the recyclability of the products, increasing recycled content in the products, and shifting to alternative materials for their single-use packaging.

A 2021 review of action taken by companies conducted by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that while plastic packaging use by signatories seems to have peaked, less than 2 percent of Global Commitment signatories offer reusable packaging.

The picture is similar in Canada with popular brands and companies. One top polluter, Tim Hortons, is piloting a reusable cup share program, a step in the right direction, but the company has yet to commit to phasing out its throwaway cups and other plastics altogether. Starbucks has committed to move to reusables by 2030 but has made no progress in doing so. Canadian top polluters, Nestlé and The Coca-Cola Company, along with

other FMCGs and major retailers Loblaws and Walmart, signed the Canada Plastics Pact. As part of the Ellen McArthur Foundation’s plastic pact network, these companies have committed to the same actions as noted above. Some of these companies have also made specific commitments to eliminate certain single-use plastics like straws or other problem plastics, but they stop short of larger efforts to tackle the bulk on their packaging.

While we see more and more small-scale reuse, refill and zero waste businesses and programs pop up across Canada, the major retail, consumer goods, and restaurant companies are holding back the necessary industry-wide shift away from our take-make-waste system and a transition to a zero waste, circular, and low-carbon economy.

In Canada, less than 9 percent of plastic is recycled. The rest is burned, sent to landfill, or ends up as pollution. Canada’s current recycling capacity, at best, is about 17 percent. So even if we could do better at collecting, diverting, and recycling our plastic, we are a long way from tackling the over 3 million tonnes of plastic waste we generate each year. Focusing on recycling, recycled content, and alternative disposable packaging is like cleaning up an oil spill in the ocean with a dishcloth. Removing a bit of oil here and there won’t really address the layers of pervasive pollution, and it certainly won’t prevent the spill from happening again.

Shifting to other forms of single-use packaging like paper and other biobased materials may cause other problems. Is the source of the material also harmful to the environment, climate, or communities? Does it have toxic additives? Is it truly compostable? How is the best way to dispose of it? Does it still contain fossil fuel inputs? Composting facilities are not currently equipped to deal with a massive onslaught of packaging, so most bio-based packaging alternatives still end up in landfill or burned. And when it comes to pollution, our audits found that bio-based packaging was still present in the environment in non-biodegraded states, along with plastics that are recyclable and contained recycled content, thus not addressing the threat to habitats or wildlife.

So, what should these companies be doing? What’s the real solution and how can you help?

The only way to begin to deal with the plastic waste and pollution crisis is to stop it at the source and redesign the way companies produce and deliver products. That means cutting plastic production, legislating bans on all harmful and unnecessary single-use plastics, and accelerating the transition to reuse and refill-centred systems. Companies must commit to phasing out their reliance on all disposable packaging and move to zero waste solutions.

It’s nearly impossible for many people to avoid plastic packaging and other items in their daily lives. Where possible, supporting companies or markets that offer package-free, reusable, and refill grocery or food alternatives is a great way to ensure those models succeed and can serve as examples for sectors to scale up. If those types of options don’t exist near you, tell the businesses you frequent that you want to see them change. Call out false solutions like swapping plastic for paper and encourage your friends and family to do the same. The more these companies realize that their customers are sick of single-use, the more pressure they will feel to shift. And lastly, help push for legislative action. We ultimately need a legally binding Global Plastics Treaty that covers the entire plastic lifecycle, and we need national governments like Canada to support a just transition towards a green and just future.

The plastic waste and pollution crisis isn’t just about waste and pollution. It’s linked to our planet’s rapid and alarming loss of biodiversity, the climate emergency, and human rights abuses around the world. The top global polluters are fuelling it, but they can also help propel us in the right direction. Act now to hold top polluters and the Canadian government accountable.

Visit: act.greenpeace.org.

BY TEENA CLIPSTON, PHOTOS BY PONTUS PROTEIN LTD.

BY TEENA CLIPSTON, PHOTOS BY PONTUS PROTEIN LTD.

As the world races to produce more green and sustainable products, something might be overlooked in the endeavor. For instance, I love the organic section of my grocery store, but I hate that they are still offering me plastic produce bags, wrappers, and containers. I cringe at the toiletries section with its plastic shampoo bottles, toothbrushes, and razors. And am bewildered that we are still using fake, plastic grass as a decor in our grocery store, plastic-boxed, take-home sushi meals. Please stop.

The food and beverage industry is one of the worst purveyors of single-use plastic packaging and is a major contributor to the global waste problem. It is now well understood that recycling alone can not fix the plastic problem. In this article, we focus on solutions to the packaging problem and how Pontus Protein Ltd. (TSX-V Hulk), a Canadian food production company, is part of that solution by producing bioplastic packaging for the company’s products.

Partnering with CTK Bio Canada, Pontus’ Chief Technology Officer, Steve McArthur, explains, “We want to be able to provide our customers with biodegradable and compostable packaging. Sourcing this packaging has been extremely difficult. Suddenly, right across the street from us, we discovered CTK Bio Canada. And they are doing exactly what Pontus needs.”

Pontus specializes in aquaponic farms that produce organic, plant-based proteins, specifically, Pontus Protein Powder made from water lentils. The aquaponic system has two main components: aquaculture for raising fish and hydroponics for growing plants. The water system uses the fish by-products to fertilize the plants. Using this all-natural system, Pontus is committed to producing a product without solvents, chemicals, dyes, additives, preservatives, or pesticides. McArthur believes that there is no better way to showcase organic products than to have environmentally friendly packaging.

“CTK Bio Canada uses agricultural waste from different waste streams,” he says. “Whether it is rice husks or waste from the hemp industry, they are able to turn that fiber into plastics, which is pretty amazing.”

CTK Bio Canada is part of the CTK Group, which began creating innovative packaging for cosmetics out of Korea in 2001. The company offers customized, sustainable solutions by converting agricultural waste into biodegradable plastics.

Pontus will use its own agriculture waste to produce the biodegradable packaging.

McArthur explains, “I’ve grown tilapia for about six

years. Their fish scales are huge. However, in this facility, which is next to [CTK Bio Canada’s] facility, we are going to try rainbow trout. The scales are much smaller, so it’s not as easy [to clean] as tilapia. Then there is also shrimp. They molt, and they will do that multiple times. So, there’s a waste stream there as well. Being able to turn that into bioplastics is even more interesting.”

Fish scales and shrimp shells are made up of chitin (15%–30%). Chitin happens to be the second most copious biodegradable polymer found in nature, with cellulose being the first. One of the big questions when it comes to bioplastics is how long will it last? Petroleum-based plastics are known for lasting hundreds if not thousands of years, which is both a benefit and a curse. Bioplastics, on the other hand, may only have just months or years on the shelf.

“If you want something to be more shelf stable— say, a shelf life of more than 12 or 18 months—CTK Bio Canada can set the scale of where you want it to start biodegrading. It’s all in the polymer mix,” McArthur explains.

Of course, research is developing better bioplastics every year. In fact, a recent study out of Indonesia has discovered adding turmeric microparticles to the molding process strengthens and increases

Bioplastics are plastics that are made from renewable biomass sources using natural biopolymers instead of petro-based polymers. Materials used to produce bioplastic can be found in both plants and animals. Under the right conditions, bioplastics become biodegradable.

shelf-life of cornstarch-based bioplastic materials. The government of Canada is also promoting the transition away from petroleum-based plastics and announced in April of 2021 an $1 million investment in Bosk Bioproducts Inc. to research bioplastics made from paper mill sludge and wood fibre residue.

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is collaborating with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada as part of the federal government’s Innovative Solutions Canada (ISC) program. NRCan is also supporting the development of innovative sustainable solutions with the Domestic Plastics Challenge, which is earmarked with a $100 million fund. The government website says that successful applicants can receive up to $150,000 to develop a proof of concept, and if accepted, an additional $1 million to develop a working prototype. The race for the perfect long-lasting bioplastic packaging is on.

One of the biggest challenges right now for bioplastic production may lie in the cost of manufacturing. Petroleum-based plastics are cheap to make. Questions linger about the cost of producing bioplastic and whether it can be price competitive.

Currently, when we look at the cost of developing bioplastics, most of it goes into research and development. However, according to European Bioplastics, the cost has been decreasing over the past decade as more and more companies switch to bioplastic and production increases. They forecast that the rising demand and increased oil prices, will soon render the cost of bioplastics comparable with conventional plastic.

McArthur notes, “The genius thing about what CTK Bio Canada is up to is that their business model doesn’t include having to pay for their materials [agriculture waste].”

The model is also waste-free—the fish or shrimp used in the aquaponics system to grow lentils is harvested for grocery stores while skeletons, scales, and shells will be used in the bioplastic packaging.

Pontus is not stopping at bioplastics for packaging, either. The company has big plans to revolutionize the future of agriculture with a sustainable indoor growing platform that can aid in growing clean, organic foods in hard to grow areas around the world. Whether conditions are

too hot or too cold for outdoor growing, all they need is sunlight to run solar energy.

“We landed on water lentils as our first crop purely because of how exciting water lentils are,” McArthur says. “They are incredibly easy to grow, nutrient dense, and grow incredibly fast. Their value out competes lettuce 1000-fold. However, Pontus does have conceptual plans for other facilities. In urban areas like Hong Kong, downtown Singapore, downtown Vancouver, or downtown Calgary, we have a farm scraper design where the bottom half is all food production, and the top half is residents or a hotel or whatever.”

McArthur imagines each floor would be dedicated to specific food production. For example, one floor would be a fish habitat, other floors dedicated to plant production, and even a vineyard and orchard.

“One of the other technologies that is really fascinating for this kind of project is a company that is called Parans,” McArthur says. “It has lighting technology that is fiber optic, with receivers on the roof or sun-facing part of the building. The fiber optic cable goes to a diffuser and can put sunlight anywhere in the building.

“It [this project] certainly is the future of farming, especially in the cold or in extreme heat. And then of course, there is space. You know there is this idea from Elon Musk that we are going to need this kind of system up on Mars.”

Whether you are growing food indoors or outdoors, on Earth or on Mars, the future is in bioplastic. And that is the intelligent alternative.

For more information on Pontus visit pontuswaterlentils.com, and for investment opportunities email invest@pontuswaterlentils.com.

The Pontus mission is to provide the world with environmentally sustainable pure plant-based protein.

Pontus technology is reinventing agriculture to deliver new sources of plant protein, grown in a network of biosecure indoor aquaponic farms. We make it easy to eat healthier and more sustainably.

The impact of plastic and microplastics our ecosystems is still growing

Waste is a growing issue that we can see causing havoc on our planet and its ecosystems. From litter on the streets to overflowing landfills to ocean pollution—all are constant reminders that we need to use less and be mindful of how much waste we create and where it goes once it is thrown away.

Many communities use a linear concept of thinking when it comes to design, consumerism, and waste, also known as the take-make-waste concept. This way of thinking entails taking materials and natural resources from the earth, making something from them, and discarding them as waste at the end of their life. This approach presents many issues, with one of the more crucial being disregard for how an item will be disposed of once it reaches the end of its life. Once we throw an item away, it’s easy for us to forget about what happens to it once it leaves our sight. This problem is even greater when it comes to microplastics, which are so small they’re typically out of sight and out of mind.

Every single day, microplastics are making their way into our soil, waterways, and even food systems. Yet most microplastics are smaller than what we can see with the human eye. Though small, these plastics are having a big impact on the world around us.

Microplastics are extremely small pieces of plastic less than 5 millimetres in length, the approximate size of a sesame seed or grain of rice, though they have been found as small as nanoparticles.

Experts believe that the naked eye—unaided by tools—can see objects as small as 0.1 millimetres. This means there are microplastics up to 100,000x smaller than we can see with the human eye!

Microplastics have two main sources: they can be made intentionally, or they can occur when larger pieces of plastic fragment over time. Knowing the source helps us understand where the waste came from and can be used for creating reduction targets.

• Primary Microplastics: Primary microplastics are those created for a specific purpose, meaning they were intentionally designed to be small. Plastic pellets and abrasives found in health/body products—like exfoliating balls in body wash—is one example.

• Secondary Microplastics: Secondary

microplastics form when larger pieces of plastic break down into small pieces, such as plastic pieces found on beaches from ocean pollution.

These microplastics tend to start their journey through drainage systems and waterways. Whether it’s a personal cosmetic product you’re using at home or a fabrication process in industry, microplastics easily slip through drains and into our waterways. Their tiny size makes them non-recyclable through community programs, and they are often washed down the drain—most of the time we do it without even realizing. Plastic ingredients don’t decompose naturally and are too small to be filtered and removed through even the most sophisticated treatment systems, meaning microplastics are emitted through raw sewage, treated effluents, agricultural processes, landfills, or oceanic disposal.

Another culprit for microplastics is synthetic fabrics, also called microfibers, commonly used for home goods and clothing. The release of microplastics from these fabrics is mainly due to the intense stress they undergo during the washing process in a laundry machine, leading to the detachment of microfibres and particles that make up the textile. When your washing machine drains its water, these microplastics travel with it into our water treatment systems. At first this may not seem like very much, but when you start to think about how often you do laundry, how much of your clothing is made from synthetic fibers, and how many households have their own washing machine, it begins to add up big time.

Though microplastics are the result of a variety of different products and processes, plastics are a human-made material, meaning no matter where they are found or how they were formed, all microplastics are the result of humans.

Though plastic and microplastics have been around for over 50 years, their impact on our ecosystems is still growing.

We’re beginning to have a better understanding of the microplastic path of travel from homes and industrial processes to waterways, oceans, the Great Lakes, and other environments. We also know that their small and sometimes microscopic size means they can and are being ingested by a wide range of creatures, from marine plankton, fish, turtles, and

ocean life and even humans. Because plastics leach chemicals, consumption of plastic and microplastics may cause significant health effects to the creatures that ingest them.

In addition to finding microplastics in natural ecosystems and our food chain, microplastics have also been found in the air we breathe, which is a result of the planet’s weather trends. These plastics are all around us, but their full impact is not clearly known at this time. As with many pollutants, there may be a potential threshold beyond which microplastics become toxic to humans or other species; however, more research and studies need to be conducted to come to a definitive conclusion.

Though the impact of microplastics is relatively unknown, there are advocacy organizations, governments, researchers, and companies taking action to educate people and making changes to combat microplastic pollution. Check out some of the noteworthy work from around the world, highlighted below.

• Mountain Equipment Company (MEC), Funding Research: Mountain Equipment Company is an outdoor gear and apparel company that has their own line of products and stores across North America. In 2017, they became the first clothing business to help fund research surrounding apparel-linked microfibre pollution in aquatic environments.

• The Netherlands, Action through Policy: In 2014, the Netherlands was the first country to introduce a ban on microbeads/microplastics in cosmetic products. Since then, many countries have followed suit including Canada, the US, the UK, New Zealand, Sweden, and Australia.

• Beat the Microbead App: To help consumers purchase microbeadfree products, this app was developed to make it simple to check for plastic ingredients right from your phone. The app can be downloaded for free.

As an individual and consumer, there are simple things you can do in your everyday life to help combat microplastics.

1. Put Your Waste in its Place. Make sure you’re putting waste where it belongs. Check if it can be reused, composted, or recycled before throwing it in the garbage. This will help keep things from going to the landfill and reduce waste.

2. Check your Clothing Tags. Try to avoid buying clothes made from synthetic or plastic material. If you find words like “polyester”, “nylon”, “acrylic”, or “polyamide”, these are examples of plastic materials commonly used in clothing. For clothing you already own, consider investing in a micro-waste bag like GUPPYFRIEND, designed to catch the microplastics shed from your clothes in the washer.

3. Check your Cosmetic Products. Don’t purchase health and beauty products that contain microbeads.

4. Start the Conversation. Get in touch with your favourite brands and ask them about their microplastics and waste policies. Ask them to take responsibility for the items they put on the market.

Reducing our individual contribution to microplastics will help reduce the amount entering our waterways, affecting our environment, and impacting wildlife. By treading a little lighter on our planet, we can all do our part to help create a more sustainable future for generations to come.

GREEN OKANAGAN, or GO for short, is a volunteer-led registered non-profit organization based in the beautiful Okanagan, in Canada. Our mandate is to progress sustainability from an individual level. By sharing our own experiences and easy to implement tips and tricks, we hope to empower you to make smart consumer choices and adapt your lifestyle to improve your overall sustainability.

We break it down in an approachable way, with simple and affordable solutions anyone can implement. Join our online community for free resources that’ll help you simplify your life and improve your sustainability.

Local to the Okanagan?

Join us at our next event or workshopall are welcome in the GO community!

VISIT: WWW.GREENOKANAGAN.ORG FOR ALL THE DETAILS!

@GreenOkanagan@GreenOkanagan

By Teena Clipston, Photos by OceansAsia

By Teena Clipston, Photos by OceansAsia

“Using an annual global production estimate of 52 billion masks, we calculate that 1.56 billion masks will enter our oceans in 2020, amounting to between 4,680 and 6,240 tonnes of plastic pollution.”

- OceansAsia

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room. The global campaign against single-use plastic is in motion. We have banned straws and plastic bags, and the manufacturing of new bioplastics is on the rise. But things are not getting better in our oceans. Now, there is a new threat. According to a report put out by OceansAsia in December 2020, an estimated 1.56 billion disposable masks entered our oceans in 2020. These masks will take as long as 450 years to biodegrade into microplastics. Of course, mask wearing has continued exponentially since 2020, so we know that today the situation is much worse.

“Global mask production and consumption remained high during 2021,” says Teale Phelps Bondaroff, OceansAsia. “Tens of billions of single-use plastic face masks were manufactured and, unfortunately, as in 2020, a substantial number of these masks made their way into our oceans.”

Globally, we know that over 129 billion face masks (3 million every minute) have been added to landfills every single month since the start of mandated single-use face masks. Also in 2020, The Guardian reported that the number of masks floating in the oceans out-numbered jelly fish. Shocking, to say the least.

Along with masks, other personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gloves, and other protective elements, such as hand sanitizer bottles, are joining the already abundant plastic pollution that fills our oceans. No longer just used by healthcare workers, medical masks have become one of the main tools in preventing the spread of COVID-19. In some countries, masks have also become mandatory in public settings.

On February 1, 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) finally sounded the alarm stating, “Tens of thousands of tonnes of extra medical waste from the response to the COVID-19 pandemic has put tremendous strain on healthcare waste management systems around the globe.”

According to a study by WHO, titled, “Global analysis of healthcare waste in the context of COVID-19: status, impacts and recommendations”, more than 87,000 tonnes of PPE secured between March 2020 and November 2021 through the United Nations (UN) emergency initiative has contributed to the waste problem. This does not include over 140 million test kits, more than 8 billion doses of vaccine vials, syringes, needles, and safety boxes.

Aside from the large amounts of additional waste produced in health care settings, this new challenge of single-use PPE used by the public is challenging our waste systems through household garbage. This is a new problem that the world was not prepared for.

But exactly how do these items go from our general waste systems into our oceans and onto our beaches? One of the more prominent problems with face masks is that they are difficult to recycle. Most masks contain several different types of plastic that need to be separated before being processed, which means they end up instead in our landfills.

The most common avenues of PPE waste entering our oceans are leakage from landfill sites, improper waste disposal, and littering.

Another suggests that our waste systems are poorly managed. Landfills are prone to losing waste into the surrounding environment through wind and rain. Canada and the United States also send a significant amount of its waste over seas, and what happens to

that waste once it arrives in countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, or the Philippines is not being sufficiently recorded. If Western countries can not control what happens to their waste, how can we expect other nations to have a better system in place? We can’t.

While UN countries raced to protect their populations against COVID-19, little attention was placed on a safe and sustainable solution to the health care waste.

“COVID-19 has forced the world to reckon with the gaps and neglected aspects of the waste stream and how we produce, use, and discard of our health care resources, from cradle to grave,” said Dr. Maria Neira, director, environment, climate change and health, at WHO.

The continued flow of plastic into our oceans creates difficulty in knowing just how much plastic is floating around the globe, and micro-plastics can go undetected because of their size.

Saving Earth has published many articles on the dangers of microplastics. Some of the main concerns of micro-plastics filling our oceans include:

• Microplastics are toxic and poison the water.

• Microplastics can be mistaken as food by marine animals, which can lead to illness and death.

• Microplastics can get into the gills of fish and cause death.

• Microplastics are passed down the food chain to other animals and to humans.

• Disruption of marine food chain cycle can cause invasive species to thrive.

Scientific evidence also shows that microplastics impact coral reefs, deep seas, and polar regions. We see this problem in a number of large marine gyres—one of which you may have heard of: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which has grown to approximately 1.6 km². It is estimated to contain over 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic. What people may not be aware of is that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not the only gyre. There are four other garbage patches that had an estimated 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic combined in 2014. That number has continued to grow. Now, let us calculate how many more pieces of plastic have accumulated in these areas over the years, and add the PPE problem to those numbers.

Was The Guardian’s report in 2020 hyperbolic? Although calculating the amount of jelly fish in relationship to the number of masks floating in our oceans would seem an impossible task, we do know that marine life is being impacted. Firstly, plastic has always had a devasting impact on wildlife and ecosystems. This is undebatable, but how do face masks, in particular, cause harm?

The ear loops of face masks can get tangled around wildlife leading to starvation and death. It is important to remind people to cut the straps. However, entanglement is not the only problem. The decomposition process, which produces microplastics, has a far more of a lasting impact on marine life. Polypropylene and polyethylene used in face masks breakdown and have negative impacts on species and ecosystems.

“One study found that a single surgical face mask exposed to the sun and wave action can release as many as 173,000 plastic microfibres a day, while another study estimated that a face mask can release more than 1.5 million microplastic particles into the ocean under natural conditions,” says Teale Phelps Bondaroff of OceansAsia.

How long will it take for our oceans to become one big giant garbage patch?

OceansAsia states, “Without considerable effort on our part, oceans will continue to fill with plastic and do so at an accelerating pace.” This should alarm everyone. Without the health of our oceans, humanity is clearly doomed. While governments focus on fossil fuels, carbon taxes, and climate change as a general concept, what are they actually doing to stop the production of plastic?

The WHO report lays out some recommendations on how to move forward on environmentally sustainable waste practices in future pandemic preparedness efforts. These recommendations include using eco-friendly packaging, reusable PPE, and recyclable or biodegradable materials, and investing in non-burn waste treatment technologies.

“A systemic change in how health care manages its waste would include greater and systematic scrutiny and better procurement practices,” said Dr Anne Woolridge, chair of the health care waste working group, International Solid Waste Association.

“There is growing appreciation that health investments must consider environmental and climate implications, as well as a greater awareness of co-benefits of action,” she says. “For example, safe and rational use of PPE will not only reduce environmental harm from waste; it will also save money, reduce potential supply shortages, and further support infection prevention by changing behaviours.”

Refocusing research and funding on sustainable face mask mate r ial alternatives must move to the top of the list of sustainability actions. Our Earth’s health depends on it.

In response to government mandates, the world’s factories produced 52 billion disposable face masks in 2020. It’s estimated that 1.6 BILLION of them ended up in our oceans.

Here’s how long they take to biodegrade.

ALUMINUM CAN

CIGARETTE BUTT

200 YEARS

DISPOSABLE DIAPER

10 YEARS PLASTIC GROCERY BAG

20 YEARS

DISPOSABLE MASK

450 YEARS

Mask pollution from 2020 is equal to 7% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a mass of plastic debris that floats in the Pacific Ocean.

MASKS 5,500 T

PLASTIC BOTTLE

50 YEARS

STYROFOAM CUP

SINGLE-USE MASKS include N95 respirators and surgical masks.