It was dead, lying there still on the beach enveloped in a pile of rotting sargasso, woven in faded fragments of plastic, with the buzzing of flies eager to drop their larvae on its decomposing flesh. If I had just kept walking it would have seemed a beautiful day, but there I was fixated on the damage humans have caused. This poor beast had swallowed its last plastic bag.

It is easy to just walk by, to put the blinders on and kid ourselves into thinking everything is ok. Thankfully most people are waking up to the reality of the massive mountain of ecological afflictions now inundating the Earth.

There is no doubt that we are in a global climate emergency. But what most people don’t realize is that climate change isn’t just about fossil fuels. Almost every environmental issue has a direct link to climate change. Whether it is too much plastic and pollution in the oceans, deforestation on land, greenhouse gases in the air, or the killing of wildlife; it all impacts the climate.

The focal point in the minds of most people is the economy. And as important as the economy is for our society, we must not forget our environment. We need to increase awareness about the environment through education. We need easy to understand dialogue and we need to make this personal, now.

On July 26th, I successfully completed The Climate Reality Leadership Training with former Vice President Al Gore and the Climate Reality Project team. This amazing network of individuals is an exemplary example of how we can work together individually to make a global difference. I will be initiating my leadership on climate in the coming months and hope that you will join me as I strive to make a difference.

I have realized how very important it is for us to work together. Most of us are passionate about something in the natural world. If each person finds a way to focus on that one thing that connects them to nature, we can, globally, make a difference together. Whether that passion is going fishing, camping, gardening, birdwatching, snorkeling, or caring for animals, all of us have at least one blissful connection to nature — nature brings us balance. We absolutely require our governments and international agencies to take the ‘big steps’ in making policy changes, but we also need individual ‘small steps’ to protect the Earth. With these steps we become ecologically sensitive, together. Your passion can turn into a movement for fundamental policy changes. Save a reef, clean a beach, recycle, grow organically, protect a species; each action in turn will benefit the Earth and protect future generations.

We can’t all fix everything, but each of us can fix one thing.

In this edition of Saving Earth Magazine, we take a look at wildlife in the face of climate change, habitat destruction, and thoughtless extermination. In 2019, the United Nations reported that one million species of plants and animals were (and continue to be) at risk of extinction with habitat loss being their largest threat.

During Australia’s bushfires of 2019 - 2020, nearly three billion animals (mammals, reptiles, and birds) were killed or displaced. As scorching temperatures continue to rise around the world, leading to drought and even more deadly fires, what does the future hold for life on this planet? It is vital people understand that humankind will not survive without biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. The environmental web of life is absolutely interconnected, with each species relying on another for its existence, humankind included. This statement, in itself, highlights how people will not change unless it is personally relevant. The alarm is sounding, there is no more time for sweet talk. We cannot continue to stand by while one species goes extinct after another and expect no consequences. I carry in my heart the pain and suffering of each animal that has met its end because of human action, whether it was intentional or not. All life must be given respect, even those that we consume. I feel strongly that as humans it is our responsibility to be the caretakers of this planet, anything less is pure arrogance.

Certainly, extinctions have occurred throughout history, but human activity and climate change are the primary reasons for the acceleration of species extinction, so much so that the current rate of extinction is 10,000 times higher than historical extinction rates.

Unfortunately, we do not have the space in this edition to examine all at risk creatures, but we have dedicated this quarter’s magazine to a few. We implore you to get involved locally to protect the wildlife in your area. Join me in Saving Earth.

- Teena Clipston, publisher of Saving Earth Magazine and Climate Reality LeaderPUBLISHED BY SAVING EARTH

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Teena Clipston

SENIOR EDITOR

Cassie Pearse

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Dean Unger

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Cassandra Redding

ADVERTISING

Jodi Mossop

GREEN BUSINESS REPRESENTATIVE

Monique Tamminga

CONTRIBUTORS

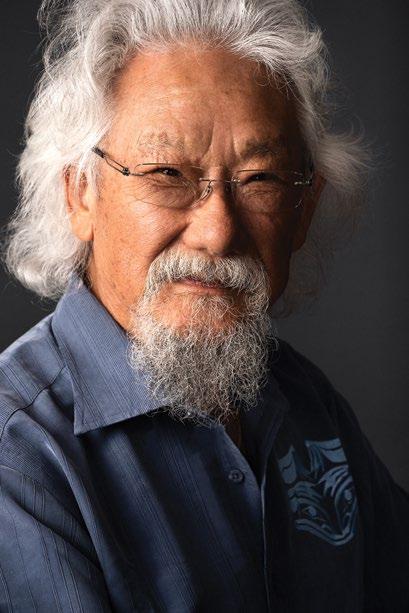

Jay Clue, Dean Unger, Emma Rodgers, Cristina Mittermeier, The Parvati Foundation, Sophie McDonald, Nam Cheah, Cassie Pearse, Monique Tamminga, Sergio Izquierdo, Roslyne Buchanan, Lola Méndez, David Suzuki, Kayla Bruce, Shayne Meechan, Ingrith León, Ellen Sharp, and Tara Pilling.

PRINTING

Royal Printers

DISTRIBUTION

Magazines Canada & Royal Printers

SPECIAL THANKS

to the Hitz Foundation for their generous donation.

COVER PHOTO

Jay Clue

Saving Earth Magazine has made every effort to make sure that its content is accurate on the date of publication. The opinions expressed in the articles are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the publisher or editor. Information contained in the magazine has been obtained by the authors from sources believed to be reliable. You may email us at Saving Earth Magazine for source information. Saving Earth Magazine, its publisher, editor, and its authors are not responsible for any errors, omissions, or claims for damages, and accepts no liability for any loss or damage of any kind. The published material, advertising, advertorials, editorials, and all other content is published in good faith.

©Copyright 2020 Saving Earth. All rights reserved. Saving Earth Magazine is fully protected by copyright law and nothing herein can be reproduced wholly or in part without written consent.

PRINTED IN CANADA savingearthmagazine.com info@savingearthmagazine.com

Saving Earth Magazine focuses on environmental issues, green businesses, conservation, human rights, and climate science. It inspires readers to change how they interact with the planet and offers solutions to global environmental challenges that we face. Some of these solutions include directing readers to organizations and businesses that are making a difference, giving them the ability to support and follow the issues they care most deeply about.

Across the world, we see a groundswell of people engaging to protect their environment, from governments banning plastic bags to individuals inventing exciting new green technologies and Saving Earth Magazine is becoming a part of this step-change. There has never been a more crucial time for this magazine. We don’t just want to report the conversation, we plan on creating the conversation!

At Saving Earth Magazine, we strive to create and bring together ideas that have the power to transform the way we interact with the planet – to devise, communicate, educate, share and help implement strategies and new technologies, which reduce pollution, reduce greenhouse gases, nurture and protect flora and fauna, and protect the waterways.

With contributions from experts and fieldworkers from around the globe, we seek to inspire individuals and organizations to become motivated to protect the planet. We cover stories of success in pioneering fields of ecology and environmental sciences; stories from communities that have faced challenges and found equitable, sustainable solutions that the world should replicate; and inspirational human interest stories and biographies that serve to inspire our lives and help us reconnect to the Earth.

By sharing ideas about how we can make a better world, we will help to heal communities and support those who are at the forefront of ecological and environmental research. Saving Earth Magazine is a manual that can be referenced globally, and will provide an evolving canvas of themes, information and ideas, which will inspire a new era of human interaction with the planet. It is a public forum where ideas and dialogue help to shape our thinking in these emerging fields. It will help us rethink the way we interact with the planet as we seek to find solutions in the transition from fossil fuels, and into new vistas of renewable energy and resources.

FACEBOOK.COM/SAVINGEARTHMAG

INSTAGRAM: @SAVINGEARTHMAG

TWITTER: @SAVINGEARTHMAG

ISSUU.COM/SAVINGEARTHMAGAZINE

photo credit: Romolo Tarani

ISSN 2563-3139 (Print), ISSN 2563-3147 (Online) Library and Archives Canada, Government of Canada

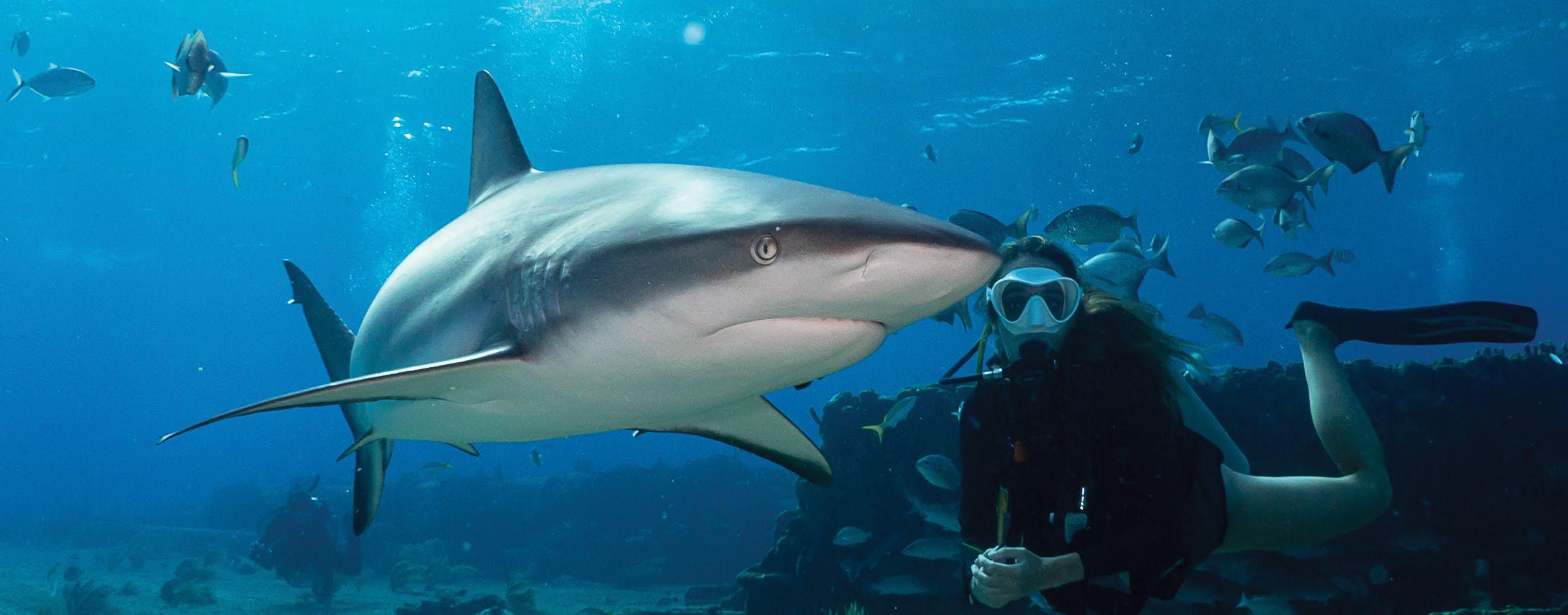

The warm Baja sun glistens across the Sea of Cortez creating a cinematic scene just below the surface. Beams of yellow light dance through the waters, fading down into the blue depths below as forty plus sharks encircle us. But this is no Hollywood scare-fest. There are no bloodthirsty monsters of the deep here, no maneater mouths filled with butcher knives being powered by a thousand kilos of pure evil muscle. Instead, we see curious and almost playful creatures. They circle us, interested in our cameras because of the electromagnetic fields they produce while investigating the area. Our team is marvelling at one of the ocean's beautifully rare spectacles - the summer aggregation of silky sharks off the coast of Los Cabos, Mexico. There is no tension, no anxiety or fear. Just a feeling of peace and admiration for these remarkable animals. Yet, a sombre feeling keeps creeping in the back of my mind, knowing that in the very near future this beautiful encounter may no longer exist.

141 sharks

killed since you began reading this article

Silky sharks aggregating off the coast of Cabo San Lucas, MexicoThe first shark ancestors began to inhabit our oceans over 450 million years ago, about 65 million years before trees began to dot the Earth's landscapes creating the blue and green colorway so synonymous with our planet. It would be over 150 million years before the first dinosaurs would roam the earth. Us humans are a mere blink in the timeline of the oceans' most misunderstood creature. Even if we journey as far back to the first human ancestors we only reach five to seven million years ago; meaning the ancestors of modern sharks had already existed for well over 400 million years before our ancestors first appeared on the great stage of life. That is a breadth of time extremely difficult to truly fathom. Our human lives work in minutes, days, weeks, and years. As we reach decades and centuries, time begins to slowly mesh together and blur. We simply can’t truly comprehend millions of years. But let’s try something. Take a quick moment to glance at the nearest clock and make a mental note of the time right now. I promise it’ll help put perspective into this journey a bit later.

Millions of years of evolution and adaptation have made sharks a keystone predator in most marine environments. They help to balance ecosystems and keep everything in check. Sharks remove the sick and weaker animals while helping keep populations from exploding and taking over. In many cases sharks are the apex predator in their environment, feeding on the different species below them in the food web. Imagine that on a reef you have small fish that eat algae, then larger fish that feed on these smaller algae eating fish. A shark then feeds on the larger fish. If we were to remove the sharks from our equation, the larger fish are kept unchecked and can grow in population, ultimately possibly eating all of the smaller algae eating fish and leaving algae to take over the reef and wreak havoc on the ecosystem.

We can see how removing apex predators affects marine ecosystems through studies of remote reefs that have had little to no exposure to human impacts—especially fishing. A research study of remote reefs in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands found that apex predators, including sharks, make up more than 50% of the total fish biomass on these remote reefs with no human impact. However, the study noted that on similar reefs with regular human impact, and/ or fishing, apex predators only accounted for less than 10% of the total fish biomass. But it isn’t only sharks that benefit from a lack of human interference. Studies show that when sharks and reefs are left alone, both the biodiversity and biomass of marine life increase. That means we see both a wider variety of marine species as well as more of individual species.

Another study in North Carolina showed that while the populations of large sharks such as hammerheads and tiger sharks declined by up to 99% due to overfishing and bycatch, the population of the cownose rays that they prey on increased ten-fold. This explosion in the number of cownose rays in the area was one of the driving factors for closing down North Carolina’s century-old bay scallop fisheries in 2004. Bay scallops are an important part of the diet of cownose rays, but scientists estimated that this increase in their population meant the rays were eating three times the total catch of the commercial mollusc fisheries in the area — leading to its collapse.

Shark conservationist, Liz Parkinson, explains, "The importance of sharks in the ocean far exceeds being an apex predator. They are an advanced being that is part of an integral web in the complexity of the animal kingdom. The rapid deterioration of our shark populations has created an imbalance in the ocean ecosystem. These vital predators, found at the apex point of the food chain, allow for a healthy sustain-

A female tiger shark affectionately known as Joker for her playful antics off the coast of Bimini. Photography: Jay Clue.Top: A curious Shortfin Mako off the coast of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. The fastest shark on earth, capable of bursts of speed up to 74km/h, yet also classified as endangered with extinction by the IUCN. Mid left: The critically endangered Great Hammerhead shark. Mid right: A Lemon Shark rests in the Bahamas while a rémora cleans her teeth. Bottom: A grey reef shark patrolling the reefs of the Bahamas.

Photography: Jay Clue.

able environment. As their numbers deteriorate at an alarming rate, these animals who have existed for millions of years, are taking with them the evolutionary power needed to keep our oceans alive."

An ocean without sharks is a grim future no one wants to consider but sharks are being removed from our oceans at an alarming rate. A study published in the journal Marine Policy, estimated that 100 million sharks are killed by humans every year. However, they also add that this is a very conservative estimate and that the true number could be as high as 273 million. Using the more conservative figure of 100 million, that breaks down to 11,416 sharks per hour, or 190 sharks killed every minute. That is more than three sharks every second. How long has it been since you looked at the clock? 400 million years may be hard to wrap our heads around, but 190 sharks killed in one minute is much clearer, and a lot scarier than any Hollywood monster film or clickbait news article.

Sharks are commercially fished throughout the world for both their fins and meat. The demand for shark fin soup is regularly highlighted as being one of the major causes of their population decline. However, shark meat is also regularly used in all sorts of products from cosmetics to pet food and more. Yet many of these products don’t even mention shark on their ingredients labels. Even more worrying is that recent studies are beginning to show that shark meat is being mislabeled in a lot of seafood throughout the world.

Shark meat is a cheap seafood that can be cooked in many ways to make it unrecognizable, leaving consumers unaware they are actually eating shark. Studies into fish & chip shops in the UK and Australia have shown that most of the ‘fish’ was shark. A kilo of shark meat can sell for one euro in Europe, whereas swordfish would sell for 12 times more at the same market - making the fraudulent mislabeling of shark meat a very lucrative industry.

The shark conservation organization Nakawe Project has been researching this phenomenon for the last three years by conducting chemical and genetic testing on filets sold in fish markets and supermarkets. Their DNA results showed that 27% of the fillets analyzed were Shortfin Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus), 13% were blue shark (Prionace glauca), and 11% were pelagic thresher shark (Alopias pelagicus). This is alarming because both mako and pelagic thresher sharks are currently listed as vulnerable to extinction on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species, while blue sharks are listed as near threatened. Their research also showed results of numerous other species listed on the IUCN Red List; including smooth hammerheads and silky sharks.

corporations to clearly label their products”, explains Nakawe Project founder, Regi Domingo. “Our hope is that if consumers know what they are being fed then they won’t want to support this exploitation of endangered apex predators. You probably wouldn’t want to eat an endangered tiger, panda, or elephant, would you? So why should eating an endangered marine species be any different.”

Sharks have been proven to be worth much more alive than dead. By only looking at the revenue benefits of shark tourism and not even considering the value of the ecosystem services they provide, we see that sharks are worth millions more alive. In the Bahamas alone the shark diving industry contributes approximately $113 million USD per year to the economy. In Palau, shark tourism contributes eight percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). One reef shark in Palau is estimated to be worth $1.9 million USD over its lifetime, whereas one shark fished in the same area is estimated to be only worth $108 USD. It doesn’t take a mathematician to see that protecting sharks is much more profitable and it also helps protect and rebuild our oceans at the same time.

Shark scientist, Dr. Frida Lara, explains, “Shark tourism has increased worldwide. Since the 1980s, advances in the technology of the diving industry and the knowledge of sharks have improved significantly. The negative perceptions about these species have begun to change, from initially seeing them as killing machines to intelligent, incredible, uniquely beautiful beings.”

“Mexico is one of the countries with the greatest diversity of sharks and rays, and has more than 20 places where it is possible to interact with sharks. Among the most important are Guadalupe Island for Great White sharks, Revillagigedo Archipelago for multiple species, Los Cabos for multiple pelagic species, Cabo Pulmo & Playa del Carmen for bull sharks, La Paz & Isla Mujeres for whale sharks, and the list goes on.”

The chemical analysis of the fillets was also cause for concern as it showed that on average the filets contained a concentration of 1.45mg/kg of mercury, which is well above the legal limit on seafood products. Mako shark showed the highest concentration of mercury with levels of 3.0mg/kg - three times higher than the legal limit.

“We believe that people should know what they are actually consuming, which is why we have begun petitioning distributors and

Although there has been significant change in the last decades, there is still a long way to go. More humans need to speak up for sharks and get involved in their protection. This could be as easy as volunteering or making donations to conservation and research organizations, or helping spread the word about the issues sharks face. Asking where your seafood comes from before purchasing and learning the common names that shark is usually mislabeled as can help us make more informed decisions of the products and foods we purchase. But most of all, if you haven’t yet, go experience these remarkable and beautiful creatures in the wild. They will steal your heart and make you understand why so many humans are working so hard to try and protect them. Together we can be the force that keeps sharks roaming our oceans for another 400 million years. We must protect them as if our life depends on it...because in many ways it does.

killed since you began reading this article

background image: a scalloped hammerhead 0ff Isla Darwin in the Galápagos Islands. inset image: a close up of a Great Hammerhead in Bimini. Photography: Jay Clue.

BY DEAN UNGER

BY DEAN UNGER

Research has established that the ocean’s chemistry is changing at a rapid rate, due to the uptake of anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO₂). Ocean acidity (OA) levels have been on the rise since the industrial era, and continue to threaten shell-fish production on the Pacific West Coast, from California to British Columbia.

“The potential biological effects of OA were first documented in the late 1990s,” said Christopher Harley, a Professor, at UBC Dept. of Zoology and Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “But it wasn't until the early 2000s that both research on, and awareness of, the issue really took off. The early experiments were short term and usually only considered one species at a time. More comprehensive studies have really only been done in the last 10 years, so the field is still young.

As the scenario played out, in 2007, technicians at an oyster farm in Whisky Creek, Tillamook, Oregon, recorded consecutive sudden mortality rates among oyster larvae. It was soon discovered, via a process of trial and error, that seawater pumped into the hatchery seedbeds was indeed so corrosive it was preventing young oyster shells from fully developing. As a result, seed production in the northwest plummeted by as much as 80 percent between 2005 and 2009.

Researchers at the facility immediately began working with academic and government scientists, and ultimately showed a high correlation between the aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) of in-flowing seawater and the survival of affected larval groups. Findings clearly linked increased CO₂ levels to hatchery failures, specifically regarding mortality rates in the first few days of growth.

A paper published by the Oceanography Society confirmed that 2007 brought unprecedented levels of larval mortality for commercial hatcheries in the US west coast shellfish industry – initially, those were producing the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Since then, numerous other species have been added to the list of affected populations.

Increased carbon dioxide concentrations in the water do three things, Dr. Harley explained: 1) feed plants and algae that can use the CO₂, 2) create challenges to maintaining the internal acid-base balance, which takes energy to keep in balance and can lead to all kinds of problems once it is out of balance, and 3) make it harder to build and maintain shells and skeletons out of calcium carbonate. For the first point, some shellfish may actually get a bit more to eat, although there is also evidence that increased CO₂ leads to harmful algal blooms too. For point two, the early life stages (larvae) of shellfish can be very vulnerable to these energetic costs, and their development can be delayed and mass mortalities can occur. For the third point, growth rates for most calcified plants and animals are slower when CO₂ concentrations are higher, and shells can dissolve completely or fail to form in the first place if conditions become severe enough.

To meet the growing challenge, researchers in British Columbia have joined efforts with Oregon and California. Pacific Coast Shellfish Growers Association (PCSGA) undertook to monitor shellfish hatcheries and coastal waters, establishing an information-sharing network in collaboration with university researchers and the US Integrated Ocean Observing System.

phtography: Farhan Sharief

Unhealthy pteropod showing effects of ocean acidification including ragged, dissolving shell ridges on upper surface, a cloudy shell in lower right quadrant, and severe abrasions and weak spots at 6:30 position on lower whorl of shell. Photo

credit: NOAA's Fisheries Collection.

photography: TOan chu

photography: TOan chu

“We have surprisingly poor long-term records of CO₂ and pH in the sea,” says Harley, “because for a long time scientists assumed that these wouldn't change very much and didn't bother to measure them. The early research showing that CO₂ and pH were changing was done at about the same time as the first biological experiments, and most of those early biological experiments were on shellfish like sea angels, sea urchins, and oysters. It was only a few years later that hatchery failures for oysters would be attributed to low pH water.”

One of the certainties to come from the effort, is confirmation that seasonal coastal upwelling, which supplies nutrient-rich water to the inner continental shelf from late spring to early fall, drives productivity. However, in addition to fueling the industry, it also threatens it. Decomposition of organic matter, at depth, naturally raises CO₂ in upwelled seawater, and increasing atmospheric CO₂ concentrations have raised the baseline, leading to increased intensity, magnitude, and duration of acidified water over the continental shelf.

“We have a calcite or aragonite saturation state index, which indicates whether or not calcifying organisms would naturally be able to precipitate their shells,” says Richard Feely, a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (NOAA). “This index is different for different organisms producing calcite or aragonite shells that are necessary for many species to thrive. The task is to understand the mineralogy and what an optimum saturation state looks like. If the saturation state is high, they do fine – if it gets close to one, then it becomes difficult for them to produce their shells. We've had to understand the mechanism of shell precipitation for each organism, to determine what level they are affected at. It turns out that CO₂ indeed lowers the saturation state, and in doing so, creates risk. Shellfish are unique, in that they require high concentrations of calcium and carbonate to generate their protective shells. The issue then becomes the levels of carbonate concentration in the water.

The shellfish community were saying they were having difficulty producing seed, but didn't know why. By 2008, Dr. Feely and his team completed a research survey along the entire west coast and concluded that, in fact, the problem was actually caused by the increasing CO₂ levels in seawater. The scientists discovered that oyster larvae, once hatched, were very sensitive to changing aragonite saturation state and could die off in approximately two days. Oyster larvae don't feed right away in the natural environment, during those critical first few days they feed off yolk reserves. If the yolk runs out before they develop the ability to feed externally, they can’t survive. What we found was very dramatic, Feely said. “When the waters were highly corrosive, the organisms died within two days. When the water had high saturation state, they did just fine. This is happening around the world as oceans take in higher loads of carbon dioxide.”

Yet another process phase of oyster seed production offered a further clue, and ultimate confirmation: there was a shift in transient water quality in the ocean between morning and afternoon. “When they drew water later in the day, the oyster seed were better off,” Feely said. “This observation at least suggested where the problem was.”

Early success with adding carbonate to the seawater drawn from the environment, to be used in the hatcheries themselves, was promising, although researchers, and industry people alike, admit this is a stop-gap measure to keep the shellfish industry in the hatcheries going. At present, there is no feasible measure to solve the greater problem and the larger long-term effects.

Part of the problem – perhaps the most daunting, is in coming to terms with the overabundance of man-made carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, largely resulting from our reliance upon fossil fuels, and the chemical and petroleum byproducts that are manufactured and used worldwide. “You've hit some of the major issues here that we are studying all the time,” Feely explains. “We know how much has changed from our measurements and model results and we have reasonable estimates for future conditions.”

In a 2005 story in the Stanford News by Mark Schwartz, scientists from Stanford University confirmed their long-held suspicions that “fertilizer runoff from big farms can trigger sudden explosions of marine algae, capable of disrupting ocean ecosystems, and even producing 'dead zones' in the sea.” This was some of the first direct evidence linking large-scale coastal farming to massive algal blooms in the ocean. It was not long after, that reports from the aquaculture industry indicated that there was a serious problem mounting with oyster seed mortality rates.

The NOAA website states that nutrient pollution is a process whereby too many nutrients - mainly nitrogen and phosphorus - are added to bodies of water and can act like fertilizer, causing excessive growth of algae, which then blocks light needed for plants to grow. Excessive nutrients can come in the form of fertilizer-laden run-off in urban areas, which contribute to high acidity levels, and can often lead to low oxygen levels in the water. Coupled with rising CO₂ levels in the water, the resulting acidity has threatened fish, crabs, and oysters. Most of the man-made sources originate in wastewater treatment facilities, run-off from land in urban areas during rains, and from farming. If the problem continues it may well put increased pressure up and down the food chain.

Even a cursory look at most modern hydrographic maps will show a number of UXO sites located along coastlines and inland locations, along with respective advice to avoid these areas. UXO stands for unexploded ordnance – unused bombs and weapons that were jettisoned by the military after World War Two.

A story in Smithsonian Magazine, published November 11, 2016, Chemical Weapons Dumped in the Ocean After World War II Could Threaten Waters Worldwide, written by Andrew Curry, reveals the massive scope of the challenge. Curry writes that when peace finally arrived in 1945, the world’s military forces, and their respective scientists, did not know how to dispose of their massive arsenals of chemical weapons. Ultimately, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States decided that it would be efficacious to dump it all into the ocean, including unexploded weapons and chemicals.

Today, experts estimate that one million metric tons of chemical weapons lie on the ocean floor—from Italy’s Bari harbor, where 230 sulfur mustard exposure cases have been reported since 1946, to the U.S.'s East Coast, where sulfur mustard bombs have shown up three times in the past 12 years in Delaware, likely brought in with loads of shellfish. “It’s a global problem. It’s not regional, and it’s not isolated,” says Terrance Long, chair of the International Dialogue on Underwater Munitions (IDUM), a Dutch foundation based in The Hague, the Netherlands.

James Delgado, host of the Nova Productions documentary, Sea Hunters, agreed that the chemicals are certainly an issue, but are a small portion of the larger problem. “There are hundreds of thousands of ships, planes and all manner of cargo sitting on the bottom of the ocean,” Delgado said, “many of these potentially littered with unexploded ordnance; [it’s a problem] with no easy solutions.” Delgado points out there are now numerous expert salvage companies that specialize in securing old UXO sites, however, some are either too deep or too dangerous to handle. He believes we are due to encounter some of the problems that were predicted decades ago.

It is only recently that we began to question the practice of dumping chemicals and effluents from mills and processing plants into otherwise healthy rivers, streams and bodies of water. Many processing facilities, chemical plants, and mills made a habit of dumping effluents in the backyard, especially during the period 1950 - 1970s. Nature was seen as the communal disposal system: out of sight was out of mind. It was felt that we had every right to use the environment as a dumping ground in a haphazard and spontaneous way. In Canada, and likely all of North America, there are now dump sites leaking effluents and pollutants across the continent: as with ocean dump sites, some can be cleaned up, some cannot.

Add to the above, accidents and spills involving railroads, ocean freight ships and highway tankers. Consider too, the mass consumer use of chemicals, which then often get flushed or poured into the sewage, drainage or natural water systems; add carbon emissions from vehicles, plants and mills; sewage and refuse from homes, cabins and cruise ships, and, add to all of it the effects from changing water temperature, from human-caused climate change.

The US-EPA website provides a list of clear directives to be implemented between federal and state governments, including overseeing regulatory programs, developing a collaborative approach to cleaning up, providing technical and program support to states, and financing nutrient reduction activities. Although the subject of regulatory measures is present in the document, there is a seeming lack of dialogue regarding actual enforcement. This leaves the question as to whether it will be left to the stake-holders and industries themselves to decide their degree of commitment to the process. The need for adequate, effective enforcement is an ongoing problem, one that has recently been exacerbated in North America, by the systematic stripping of environmental regulations by the Trump administration during his first three years in office.

Here in Canada, as per the Government of Canada website, scientists from Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Water Quality Monitoring and Surveillance programme, said there is a contrast between the need to preserve ocean health and policies that appear to contradict that need. A document on the Environment Canada Climate Change page shows a heading entitled How substances are permitted for disposal at sea. The site maintains that only substances listed in Schedule 5 of CEPA are eligible for consideration for ocean disposal. Proposed projects are evaluated by regional Disposal at Sea Program staff, in accordance with the assessment requirements. Of particular note here, is that among the items approved for consideration are

“ OA is a global problem and truly getting on top of it will require a lot of work at the national and international level to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

dredged material; ships, aircraft, platforms and other structures; uncontaminated organic matter of natural origin; fish waste and other organic matter from industrial processing operations. Disposal of fish waste at sea has recently been vigorously questioned by scientists and industry proponents alike due to suspicions it may be contributing to disease in wild fish populations and increased OA. The Canada Fisheries and Oceans website addresses the issue in a document titled, Managing Organic Wastes

It is likely that existing policies will be rigorously scrutinized as the challenge unfolds as clearly there is still work to be done.

As OA advances in coming decades, the window of opportunity for spawning events to coincide with favourable water chemistry will continue to shrink.

The paper's authors conclude that “significant challenges remain, and a multifaceted approach, including selective breeding of oyster stocks, expansion of hatchery capacity, continued monitoring of coastal water chemistry, and improved understanding of biological responses will all be essential to the survival of the U.S. west coast shellfish industry. Because their livelihood depends entirely on the health of the coastal ocean, shellfish growers, who now recognize a very clear and immediate threat to their industry, possess a fairly advanced level of understanding of acidification and the coastal processes affecting it,” (Mabardy, 2014). But what does it mean for the rest of the ocean's inhabitants?

“OA is a global problem,” Dr. Harley said, “and truly getting on top of it will require a lot of work at the national and international level to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But there are local options too. Keeping the ecosystem healthy usually makes it more resilient in the face of stresses like OA, so designing marine protected areas and setting sustainable harvest quotas is helpful. Limiting pollution and fertilizer runoff is important too, as those factors can magnify the negative effects of acidification.”

Changes among marine species and entire ecosystems will be subtle at first, says Harley, “but in the long-term, certain stocks may no longer be economically viable, and managing pH issues will become so expensive for land-based aquaculture that either companies will go out of business or consumers will have to pay a premium for their seafood. Food security in some coastal communities will be at risk, and larger ecological changes may arrive suddenly as the system crosses tipping points that aren't easily reversed.”

Ultimately it is largely agreed among scientists that the problem of OA stems from our carbon-based, fossil fuel propelled orientation to energy and power requirements. This must change. What we're facing is the result of decades of blissful and willful ignorance that propelled people to use the planet as a dumping ground for pollutants. This is just the beginning of a long-term struggle, which will require definitive policy, enforcement and collaboration across the board.

BY EMMA RODGERS

BY EMMA RODGERS

Coral reefs in the Caribbean are transforming from colourful, mesmerising networks of life, to eerie, green carpets. In these tropical reefs, fast-growing algae outcompete corals for space and light, and reefs are quickly invaded by an army of green. Eventually the smothered corals die, and the health of the reef is severely compromised. Astonishingly, tropical coral reefs support a quarter of all marine life on the planet whilst occupying just 0.1% of the ocean floor. Therefore, to prevent the marine ecosystem from total collapse, coral-dominated reefs need to be restored - and the answer may lie in the humble parrotfish.

Reefs in the Caribbean have been regularly monitored since the 1970s and since then, many have undergone dramatic shifts from vibrant, coral-dominated habitats to dull, algae-dominated habitats. Coral reefs may appear to be harmonious, peaceful landscapes, but beneath this mirage, a silent war is occurring. Corals and macroalgae, the dominant benthic groups in coral reefs, are in constant competition for limited resources, including space and light. Light is a particularly valuable commodity under the water for photosynthetic organisms. Both the zooxanthellae (single-celled algae that reside in the tissues of corals) and macroalgae require light to photosynthesise in order to produce the nutrients needed to survive and grow. When corals face disturbance, such as coral bleaching, storm action or disease, macroalgae claim victory and spread across the reef, revelling in their newfound space and lapping up the sun’s rays. As macroalgae asserts its dominance on the reef, corals languish in a green fog, smothered by thick green blankets. Unable to photosynthesise due to lack of light, the zooxanthellae fail to produce enough nutrients for the corals to function. Worse still, fleshy macroalgae release generous amounts of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) which gets eaten up by microbes. Microbes play a large role in nutrient recycling processes on coral reefs, but the influx in DOC creates an ideal environment for potentially harmful microbes to flourish, and disease can quickly spread across the reef, causing further coral mortality and maintaining algae dominance. For example, in the 1980s, algae-dominated reefs in the Caribbean suffered a disease outbreak, which killed 80% of elkhorn and staghorn corals, both major reef building corals from the Acropora genus.

When corals cannot thrive, coral reef ecosystems simply cannot host the diversity of life that depends on them for food and shelter. This is the key problem with algae-dominated reefs: they quickly lose their ability to support and stabilise the marine ecosystem. Healthy coral reefs are not only ecologically important, they also provide coastal communities with economic services, directly supporting over 500 million people worldwide. In the Caribbean alone, coral-reef related tourism generates annual benefits of USD $2.7 billion. Devastatingly, coral cover in the Caribbean has declined by 50% since the 1970s. It is vital that this figure does not increase. We must put a pause on the spread of algae and shift the green reefs back to being resilient coral havens where marine life can blossom.

Parrotfish, of the family Scaridae, are a peculiar family of 80 recognised species that are strongly associated with tropical reefs across the world. Their biodiversity peaks in the Indo-Pacific region, par-

Photography: Placebo365

top left: humphead parrotfish. photography: Atese, top right: Parrotfish are herbivores and feed on algae that they scrape from the reef using their hard beaks. Photography: Simak. Bottom: bullethead parrotfish. photography: Bearacreative. Top Right: The bright colouration of parrotfish make them the one of the most conspicuous coral reef residents. Photography: Levent Konuk. Bottom Right: If herbivorous parrotfish do not graze the macroalgae on the reef, it proliferates and smothers the corals.t icularly the Coral Triangle. With their compelling and flamboyant colours, parrotfish are among the most conspicuous residents of the coral reef ecosystem, making their presence a joyful spectacle for many a lucky SCUBA diver. A tell-tale sign that a parrotfish is nearby is a very loud crunching sound, which ripples through water as they feed. Most parrotfish are herbivores and spend up to 90% of their day eating algae that they bite and scrape from the surface of reefs. Whilst some species also like to feed on live corals – the largest parrotfish, the bumphead parrotfish, can remove five tonnes of coral structures every year – most parrotfish prefer dining on algae-covered surfaces. These noisy feeding behaviours are enabled by a fairly bizarre adaptation, which gives parrotfish their endearing ‘buck-toothed’ appearance - a set of over 1,000 teeth that are fused together to form a solid beak. To add extra strength, each tooth is made of fluorapatite, the second hardest biomineral in the world. This unique uncrackable beak allows parrotfish to scrape and bite into hard corals in order to secure an algae fix.

Parrotfish act as important bioeroders and play a large role in the maintenance of coral reefs. Most critically, by removing macroalgae from the reef’s surface, parrotfish not only open up space for younger corals to grow and flourish, they also control the growth of algae communities that impede coral recruitment and growth. In short, parrotfish help to establish healthy coral-algae interactions. In the Caribbean, the functional importance of parrotfish in keeping the algae at bay dramatically increased in the 1980s, following the mass mortality of the herbivorous sea urchin, Diadema antillarum, which once munched its way through large volumes of algae growing on the reefs. In these regions, parrotfish are now the primary grazers on the reefs.

Parrotfish must be protected, not only because of their critical functional role on coral reefs, but also because it would be a great shame to see such a quirky family of fish fade from our oceans.

Interestingly, parrotfish do not digest the coral fragments that they swallow as they scrape and extract algae from coral structures on the reef. Indigestible calcium carbonate coral skeletons are ground up and excreted as a fine white sand. Every year, a single parrotfish can produce a phenomenal volume of sand, sometimes up to 350kg. Over time, the white sand is washed up by wave action and eventually forms the pristine white beaches that we know and love. Next time you’re lying on a tropical sandy beach, remember to thank the tireless work of parrotfish digestive systems.

Another peculiarity of parrotfish is that before they go to sleep, many species tuck themselves into a thick mucus sleeping bag. Parrotfish have a sinister enemy: juvenile crustaceans belonging to the Gnathiidae family, which like to suck the blood from marine fish. During the day, these pesky parasites are removed by cleaner fish, but at night, sleeping parrotfish are vulnerable to attack. It is thought that the layer of mucus acts as a “mosquito net” that stops parasites from reaching the parrotfish as they sleep. The mucus also masks the scent of the parrotfish so they can essentially hide in plain sight.

Unfortunately, populations of parrotfish are decreasing; a trend which is largely due to overfishing. In some Caribbean fisheries, parrotfish dominate the catch. Parrotfish may be able to stem the tide of fast-growing macroalgae and help restore algal-dominated reefs back to being healthy coral-dominated reefs. The restored reefs would also have a greater resilience to the impacts of climate change, such as rising temperatures and ocean acidification. However, with numbers of parrotfish falling, the growth of macroalgae is not sufficiently controlled and it grows freely across the reefs – the choking corals have little opportunity to recover. If parrotfish populations continue to decrease, the occurrence of algaedominated reefs will rise even further. Sadly, a massive 70% of coral reefs are currently under threat of overfishing.

All Caribbean parrotfish are protogynous hermaphrodites, meaning most juveniles begin life as females and, should they grow large enough and territory is available, can transition into larger, more colourful terminal males. Terminal males defend a hareem, and if lost, the largest female in the hareem will transition into the next terminal male, having a go at leading the pack.

Coral reefs in the Caribbean are among the most degraded on the planet. If parrotfish populations are not restored and legislation is not introduced to control overfishing, there’s a real chance that coral reefs in the Caribbean could disappear altogether within a few decades. But there is hope! Campaigns in the Caribbean, such as The Nature Conservancy’s #PassOnParrotfish, are working to protect parrotfish by educating people about their critical role in maintaining healthy coral reefs. Raising awareness is a fantastic way to spark behavioural change. In 2009, Belize banned the fishing of parrotfish altogether, and Guatemala followed suit in 2015. To bring the reefs back to life, other countries urgently need to introduce fishing regulations to ensure populations of iconic parrotfish are replenished. These funky fish may be our last hope.

From the earliest manipulation of materials long before the common era began, until the mid-20th century, there was relatively little in the way of human pollution. Once humans began to mass-produce synthetics in the 1940s, however, the story changed and our love affair with plastics took off. In 2020, according to Ian Tiseo , cumulative plastic production has reached 8.3 billion metric tons with no end to its consumption in sight. The human race has become lazily reliant upon plastic in its myriad forms but this reliance comes with a high price tag, one that we need to examine closely in order to protect our environment and the animals living alongside our polluting species.

BY NATALIA CONTRERASPlastic absolutely has incredibly useful properties: it doesn’t break down easily, it’s cheap and it’s versatile so can be moulded and manipulated as required. Plastic plays a critical role in food quality and in the reduction of worldwide food waste. It is also vitally important within the medical world, where its cost and versatility make it perfect for one-time use sterile implements.

However, these same properties are also its downfall and our downfall too: plastic doesn’t simply disappear when we’re done with it. Most plastics are used once and then discarded into landfills and our oceans where they take hundreds of years to breakdown. Once it has eventually fragmented into macro and micro-plastics, it is ingested by living organisms. Plastic really never truly leaves us.

The problem is not plastic itself, rather how we interact with it. Consumers have failed to use these incredibly useful materials thoughtfully and with care. Instead, we have created a throw-away society where we use packaging once, often for a short time, and then dispose of it with very little thought for our environment or the animals living alongside us. Consider the lifespan of a takeaway coffee cup or a piece of plastic cutlery. Used once and discarded without thought.

For so long, we were told that as long as we recycled it would be ok. But that is simply not true. We need a serious change of mindset: we must change habits, say no to single-use products, re-use what we have and reduce our reliance on plastics.

Not only does our plastic habit impact our environment but it has a direct impact on animals too. Saving Earth Magazine has already published an excellent and thorough article by Sergio Izquierdo (Summer 2020) highlighting the serious issue of microplastics in the oceans. According to Izquierdo, 100,000 marine animals die each year from plastic ingestion and by 2050 there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish. A study published in Nature in 2019 found that the gut of every dead marine mammal around the UK that was examined contained microplastics.

It isn’t only marine life that is choking on our discarded plastic: birds also suffer as they mistake plastics for food, which causes them to starve as their stomachs fill with indigestible plastic. Birds have been found to use plastics for nest materials, mistaking it for leaves and twigs, which can then injure and trap chicks before they have even had a chance to fly. According to WWF, 90 percent of seabirds have plastic in their guts. Birds, like marine life, are absolutely vital to the maintenance of our ecosystem: they control pests that would otherwise decimate crops and they are pollinators of many plants and trees across the world yet we continue to perpetuate the destruction of their environment.

We have all seen the pictures of turtles with plastic bags hanging out of their mouths but when birds and marine animals ingest plastics they don’t necessarily suffocate and die immediately. If they swallow many smaller pieces over time, they slowly starve as they do not receive enough nutrients due to the plastics making them feel full. This often leaves them incapable of following their annual migratory paths and even incapable of breeding due to a lack of energy.

Land animals also suffer from our bad attitude as obviously not all plastic waste ends up in the oceans. Land animals, like marine animals, can also mistake our plastic waste for food. It can, of course, then cause intestinal blockages and lead to death. Animals can get their paws or even heads stuck in plastic and give themselves nasty injuries, and of course, some animals will eat birds and marine life that have ingested plastics, just as we humans find ourselves eating seafood that contains microplastics

There is an absolute urgency around creating new, non-petroleum based materials that are harmless to animals and our shared environment. We must avoid single-use plastics wherever we can and ‘the four Rs’ are imperative again: reject, reduce, reuse and, finally, recycle.

These solutions can prevent us from further contaminating our world and the animals living on it but they do nothing to fix the already enormous problem we face: the plastic already in our oceans and in landfills is not going anywhere. We need both innovative solutions and total governmental and intergovernmental commitment to clean up our world.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND STORY BY CRISTINA MITTERMEIER

PHOTOGRAPHY AND STORY BY CRISTINA MITTERMEIER

My dream of being a National Geographic photographer became a reality in 2017 when I went on my first expedition as one of the lead photographers when SeaLegacy partnered with NatGeo. The team of photographers sent to the white continent included Paul Nicklen, Andy Mann, Keith Ladsinzki, and me. Our mission was to capture the beauty and splendour of a place in desperate need of protection.

While Antarctica was as beautiful as we expected, it was bittersweet to realise that even here, in one of the most remote places on our planet, humanity has had an impact. I had been to Antarctica before as a tourist and although my first visit had been brief, I could see that even after a few short years, things had already changed.

I was so excited about this expedition. My focus was on making beautiful images, but over the course of the month in Antarctica, as we dived deeper into our story, I began noticing things that initially didn’t strike me as a problem. As the days went on, the hard reality of what was happening here became clear.

It had been raining steadily for many days. In a place where the norm is to see snow flurries, instead, rivers of guano-laden mud ran into the ocean. Snorkelling near a penguin colony, I was puzzled when the visibility in the waters abruptly became clouded. Later I realized it had started raining, and the murky water was a product of the sudden influx of muck from the land. When I got back on the boat and looked out towards the penguin colony, I could see the rivers of red guano flowing out to sea. It was clear I had been swimming in penguin poo. I became more alarmed when later that day I went on land to visit this colony of Adélie penguins. I noticed several of the chicks, which were moulting their baby feathers for their adult, waterproof coat, were covered in mud. Whereas baby penguins can preen themselves when they are covered in snow, becoming caked in clay or mud is a different story. Adult penguins can clean themselves when they go out to sea, but chicks are too young to swim, so instead, they sit on land and when the temperatures drop down at night, hypothermia can kill them because they are unable to preen and the mud freezes onto them. It is not just the change in weather patterns that is a threat;

top: A baby elephant seal, or "weaner", sits alone on a beach on the Antarctic Peninsula. bottom left: A King Penguin looks down at a lone krill, the foundation of the ecosystem with every creature from birds to whales depending on healthy krill populations for survival. bottom right: Watching a baby penguin die is never easy. This chick is not likely to survive. It is soaked from the incessant rain and coated in thick mud that it could not preen off.

photography: Cristina Mittermeier/SeaLegacy

it is the unpredictability of these changes. I was devastated to realize that these beautiful creatures simply cannot adapt to this harsh new environment with its rapidly changing weather patterns.

To the casual tourist, changes may not be apparent, but to the animals that live here, the changes are a matter of life and death. Just a few decades ago, in the 1970s, sea ice covered the ocean around the peninsula for a full three months longer than it does today. For species such as leopard seals, strict ice-obligate animals, it is a big deal as females must find pack ice in order to safely give birth and nurse their pups. As the conditions of sea ice are changing, so is the predictability of weather patterns, which in turn changes the abundance and distribution of krill and penguins. That means leopard seals must also change their habits. New scientific observations show that leopard seals are now moving into places where fur seals have started to recover after decades of exploitation. The leopard seals wait for the young fur seal pups to enter the water, and their efficiency as predators is wreaking havoc on these newly recovered populations.

When it was time to leave, we headed back across the Drake Passage, back towards the Falkland Islands. We approached the southern beaches of Elephant Island, which is only 245 km from the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. Even though we were almost 61 degrees south, we looked out at what appeared to be a green meadow on an island with a reputation for being the stark outpost where Shakelton famously left his men after his ship, The Endurance, was trapped in the sea ice and sank. While Shakelton and a six-man crew sailed 1,300 km on board the James Caird, one of the small rescue vessels from the sunken ship, to South Georgia, the other 22 survivors were left to fend for themselves on the rugged northern coast of Elephant Island. In their memoirs, they speak of a land devoid of life, a rocky outpost in the middle of nowhere, so exposed to the beating of the frigid wind and sea that nothing could grow. Now, as we stood there wearing only t-shirts on this balmy austral summer day, I could not help but cringe at the massive changes this place has experienced. Mosses and lichens were happily growing

on the rocks where nothing could grow a few decades ago. When you look at the increase in temperatures, however, it starts making sense. Annual temperatures have increased by up to 0.56 degrees Celsius per decade in the Antarctic Peninsula and sub-Antarctic islands since the 1950s; that is a full three degrees! When the temperatures were still consistently below zero degrees Celsius, a change of one or two degrees didn’t matter much to plants because all the water was still locked away as ice. As soon as temperatures started to rise above zero degrees Celsius for several hours a day, then all of a sudden, there was a lot more melted water available for growth. Mosses, which are very adaptable, take advantage and begin to proliferate. Nowhere on Earth are ecosystems changing more rapidly than in the Antarctic and Sub Antarctic islands, where even a small change in temperature has brought really big changes. The lush carpet of green mosses we were looking at on Stinker Point was a testament of this change.

We may not realize it yet, but as Antarctica goes, so does the rest of the world. In 2020, a year that has witnessed a global pandemic and the rise of a global social and racial justice movement, the world is also coming together to finally protect the vast wilderness that is the great southern ocean. By creating three new marine protected areas in Antarctica, we have an opportunity to create the largest act of conservation in the history of humanity and the largest nature sanctuary on Earth. Together, the East Antarctica, Antarctic Peninsula, and Weddell Sea MPAs would protect almost one percent of the ocean globally by covering approximately four million square kilometers and represent the largest act of ocean protection in history. This protection will not only lend resilience to an ecosystem under siege, but it will also give us more time to ultimately solve the underlying issues causing climate change.

I invite you to join tens of thousands of ocean advocates from around the world and support the creation of the largest conservation act in human history. Add your name to the growing list and urge world leaders to protect Antarctica’s waters. Sign the petition at https://only.one/act/antarctica.

A leopard seal patrols a huddle of penguins, patiently waiting for one of them to risk jumping into the water. photography: Cristina Mittermeier/SeaLegacy

A leopard seal patrols a huddle of penguins, patiently waiting for one of them to risk jumping into the water. photography: Cristina Mittermeier/SeaLegacy

With its thick ice, frigid wind, and months-long darkness, the Arctic Ocean may seem both remote and obscure. Yet in terms of its impact on our lives, this distant ocean may as well be in our back-yard. Its health is inescapably connected with our own.

The Arctic Ocean is a global life support system that keeps our entire planet cool and healthy. Through what is known as the albedo effect, its ice reflects the sun’s heat away from the planet. The cold vortex of air above the ice shapes weather patterns for the entire world, including the temperature and rainfall patterns that grow the food and resources we need and ensure we have access to drinking water. This also protects us from natural disasters and, because it stabilizes land ice in turn, it helps safeguard our homes from rising sea levels. By keeping 148 trillion kg of CO₂ out of the atmosphere and preventing significant methane release, it prevents a drastic increase in global

left: A whale swims in the arctic. photography: Alexey Suloev. above: ice melt. photos: Pxhere & Geological Survey

emissions. It also provides us with clean air, because it gives shelter and food to 17 different species of whales, three of which live there year-round. In the “whale pump effect”, whales bring nutrients from the ocean depths to fertilize phytoplankton at the ocean’s surface, which capture carbon out of the air. Ocean phytoplankton are responsible for half the oxygen we breathe, or every other breath we take.

The Arctic Ocean is critically important to keep Arctic permafrost – soil that is normally frozen year round – solid. Because of the organic matter buried in the permafrost in varying stages of decomposition, the permafrost holds large deposits of methane, as well as pathogens such as anthrax, smallpox, Spanish flu, and the plague—as well as many other pathogens for which humanity has no name, let alone immunity.

But today, the Arctic Ocean is sick, and its life-giving benefits have been compromised. Its ice has vanished precipitously in the past

five decades, while its waters are now as much as 7°C warmer than the norm. At the same time, it has become subject to exploitation of all kinds—fishing, oil and gas, shipping, military activity, and more—from businesses and governments seeking to profit off the thaw. Since such activities break up the remaining ice and disrupt an already unstable ecosystem, the risks to us all include increased pollution, species loss locally and globally, rising warming, greater natural disasters, and the deadly release of methane and pathogens.

above: Polar bear. photography: mario hoppmann.

A heating, polluted and noisy Arctic Ocean directly threatens the whales that depend on it. For example, seismic blasting and oil exploration deafen and disorient whales, who rely on sound to navigate and communicate. In addition, the diminishing ice means that polar bears may be replaced as the apex predator in some regions by orca whales –which could damage the beluga whale population in turn.

Yet all of these are symptoms of an even bigger problem: our collective greed and disconnected thinking, which are like a fever sickening our world.

Today, most of us understand that a medical mask keeps disease contained—either from getting in, or from getting out. What if we could apply a medical mask to the Arctic Ocean to keep life on Earth safe? With MAPS, the Marine Arctic Peace Sanctuary, we can.

MAPS protects the entire Arctic Ocean north of the Arctic Circle from all forms of exploitation, and compels a global commitment to

interconnection. By taking Arctic seabed oil and gas off the table for good, MAPS catalyzes our collective transition to renewable energy. It is by far the largest conservation area in history, at eight million square km, or approximately the same size as the contiguous USA.

By removing ships that break up the ice and whose dark soot lands on ice and accelerates the thaw, MAPS preserves the vital ecosystem that stabilizes the planet. By stopping commercial and military activity in the region, MAPS keeps harmful behaviour and pollutants out of the Arctic Ocean for a more peaceful, healthy world. In short, it protects the Arctic Ocean from the symptoms of our isolationist thinking, and protects the world from the symptoms of a sick Arctic Ocean. As we all come to terms with the need to wear masks to keep ourselves and others safe in the COVID-19 pandemic, MAPS is an essential medical mask for an ailing world.

MAPS originated with the all-volunteer international non-profit Parvati Foundation. We created the MAPS Treaty that updates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in order to ensure the Arctic Ocean is fully protected. It enters into force with the signatures of 99 countries, including the Arctic nations. To date, two countries have already signed and more signatures are expected soon.

Everyone has the right to know that the Arctic Ocean affects us all and that a healthy world is possible when we protect it. To get involved, please visit Parvati.org.

By Sophie McDonald

By Sophie McDonald

While it is vitally important to appreciate the range of fascinating creatures that are alive today, it is just as critical to reflect on species that we have lost. The Yangtze River dolphin, or the baiji, used to populate China’s great river in its thousands but in 2006 it was declared functionally extinct. This is a tragic tale not only because the world has lost a remarkable and beautiful animal, but also because it is representative of a far wider issue: biodiversity loss.

With every species lost, we tumble faster towards catastrophe. To understand why the loss of the baiji was so devastating, it is vital to unpick what the term biodiversity means and what the consequences of the biodiversity crisis will be if we do not take drastic action.

What sets apart Earth from every other orbiting rock in the solar system? Biodiversity. Our green and blue marble is teeming with a variety of lifeforms all interacting with one another and making our planet habitable. Biodiversity operates at multiple levels from genes, to species, to organismal communities, and ultimately the whole ecosystem, where life and the physical environment coil together. It encompasses everything from microscopic fungi to towering redwoods

and gigantic whale sharks. It is the complex web of life that defines our planet and, crucially, sustains it.

It depends where you look. The tropics house the majority of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. By definition a biodiversity hotspot needs to have lost at least 70 percent of its original native vegetation, and as such, hotspots are a focus point for conservationists. These are areas that are rich with life but also are at high risk of destruction. Examples include the renowned Amazon Rainforest and the Congolese forests in Central Africa. The trouble with being an area of immense biological richness and irreplaceability is that these areas are inherently fragile. As humans encroach ever further into these areas, the degree of damage left in their wake increases as well.

Across the whole globe there are 1.7 million recorded species of animals, plants and fungi but the most precise estimates suggest that the actual total is closer to 8.7 million, although some calculations have estimated numbers could even be as high as 100 million. Working at the genetic level has also recently revealed that what was once described as a single species could actually be broken down into dozens of species. Our planet is so diverse that we have barely scratched the surface when

it comes to identifying all of it. The issue is that life may be disappearing without us even noticing, let alone grieving.

Since the exponential growth of industrialisation in the 20th century, human activities have eroded nature across the globe. This erosion is known as biodiversity loss, which describes the loss of genetic variability, variety of species and biological communities in a given area. While biodiversity loss occurs naturally to some degree, anthropogenic drivers such as pollution, overexploitation, invasive species as well as habitat loss and fragmentation cause accelerated losses. There is also a significant interplay between anthropogenic climate change and biodiversity loss, wherein species are pushed to extinction by drastic changes in climate, and declining ecosystems become less able to sequester carbon and act as buffers to extreme weather events.

It is difficult to precisely estimate the numbers, considering we don’t know exactly how many species existed to begin with, but we lose anywhere between 200 and 100,000 species every single year. Our melting pot planet is losing its variety every single day and with each extinction the flavour of life on Earth becomes increasingly bland.

Climate change has entered public discourse within recent years, and rightly so, but it is essential that an interest in protecting our planet’s biodiversity moves into the mainstream as well. Biodiversity loss is as pertinent an issue as climate change and the consequences of failing to act on it are equally catastrophic.

Not only can many of us recount times when nature has calmed us or inspired us but the economic value of natural capital can also be quantified in very tangible ways and its benefits are woven into every aspect of modern life. Biodiversity enables us to breathe, eat and drink. It provides us with medicinal ingredients and protects us from natural disasters. Thriving economies are gifted to us by the products of biodiversity. It underpins all life, even those of humans in bustling cities seemingly detached from nature’s simplicity.

The Convention on Biological Diversity, states “at least 40 percent of the world’s economy and 80 percent of the needs of the poor are derived from biological resources.” It adds, “the richer the diversity of life, the greater the opportunity for medical discoveries, economic development, and adaptive responses to such new challenges as climate change.”

a Chinese River Dolphin. Photo crediT: Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of SciencesWhile the presence (or absence) of a single species may not seem to directly impact our lives, every species is part of a wider puzzle that shapes our entire existence. Biodiversity is what offers us planetary security, therefore it should be in the interest of every occupant of this planet to safeguard it. This means fostering an appreciation for every organism, regardless of how mundane or bizarre they may seem. When existing at appropriate levels in their natural habitat, all organisms have a role to play in maintaining biodiversity, and it is vital that we invest time, energy and money into conserving them.

The Yangtze River is China’s largest river, connecting nearly 6,300 km of the country. It’s so large that a third of China’s population live in the area covered by the Yangtze’s river basin. Today it is one of the world’s busiest and most polluted waterways, however in the not so distant past it was bustling not with boats and people, but with wildlife. Travelling along the river in early 1950s China, you might expect to see a Yangtze River dolphin; the river is thought to have been home to thousands of individuals at the time. The baiji inspired Chinese mythology and was nicknamed the ‘Goddess of the Yangtze’, symbolising peace, prosperity and protection. Traversing the Yangtze in 2020, you wouldn’t spot a single dolphin for the entire length of the river. What happened to the baiji and how did it become The Dolphin That Disappeared?

From booming populations in the 1950s, the baiji’s numbers nosedived throughout the second half of the 20th century. Around 400 individuals were alive in 1979-1981, this crashed down to only 13 dolphins remaining in the late 1990s.

There were efforts from the early 1990s to the early 2000s to create designated reserves, monitor illegal fishing in these areas, and create breeding programmes, however these efforts were managed and executed poorly. Opportunities to act effectively were repeatedly lost and as a result many conservationists now reflect on the baiji’s tale with anger and disappointment. How could such a failure happen to a large freshwater mammal? What hope does a lesser-known endangered organism have for survival?

Samuel Turvey is a biologist and palaeontologist who became involved in the late stage of conservation efforts to save the baiji. Through reading his personal accounts it is possible to gain a further insight into the frustrating lack of urgent action that led to the baiji’s eventual extinction. Turvey and many others can recount how conservation plans and their implementation were insufficient in magnitude and appropriateness. Conservation measures were implemented far too late and with insufficient financial investment and the species’ numbers rapidly declined.

From the 1950s onwards, the baiji’s home was transformed by the lethal cocktail of pollutants seeping into the ecosystem from the thousands of chemical plants lining the river. This was coupled with dam construction, large amounts of boat traffic, overfishing and unsustainable bycatch. The baiji was rapidly dragged into the maelstrom of industrialisation and eventually lost the fight for its life. The last confirmed sighting of the baiji was in 2002, and in 2006 the ‘Goddess of the Yangtze’ was declared functionally extinct.

River dolphins act as indicators for riverine health, hence the absence of the baiji speaks volumes about the state of the Yangtze’s ecosystem. Booming freshwater dolphin populations are a sign of healthy river systems, able to support the countless other species and communities that depend on them. Missing or declining river dolphin populations therefore act as a red flag calling out for immediate intervention.

The baiji’s decline had been clear to the scientific community decades before its extinction and conservation groups were aware that action to preserve and restore the species was desperately necessary.

The plight of the baiji has become a cautionary tale for conservationists worldwide and it is imperative that we heed its message if we are to prevent such a loss from happening again.

Many more remarkable animals, plants and fungi are currently under threat, including a handful of other river dolphins. Over 32,000 species around the world are on the brink of extinction and they all deserve to be saved. There is inherent value in preserving wildlife, but additionally these species all have an important role to play in their ecosystem and ultimately provide us with a better quality of life. Conservation action must be carried out rapidly, effectively and with ferocious determination to preserve the life that exists on this planet.

We must fight cascading losses at every level of biodiversity more widely and with a greater sense of urgency. We still have a small window of time to act. Transformative action is the only way that we can save our planet, including implementing legislation that protects nature at its core; ending all subsidies that lead to the destruction of nature, and shifting rapidly away from a reliance on the overexploitation of natural resources to fuel our economies.

If you want to take action today, you can amplify the issue of biodiversity loss and the critical importance of conservation action to preserve and restore ecosystems. You can also support a number of conservation organisations including: The World Wildlife Fund (WWF), The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the Center for Biological Diversity.

Dolphins have a treasured place in our hearts; their intelligence and beauty capture our fascination and losing such a beautiful creature is a heavy loss. The baiji’s tragic tale must not be forgotten if we are to learn from the past and succeed in changing the fate of species living on Earth today.

by Cassie Pearse

by Cassie Pearse

Photography: hans jurgen

Photography: hans jurgen

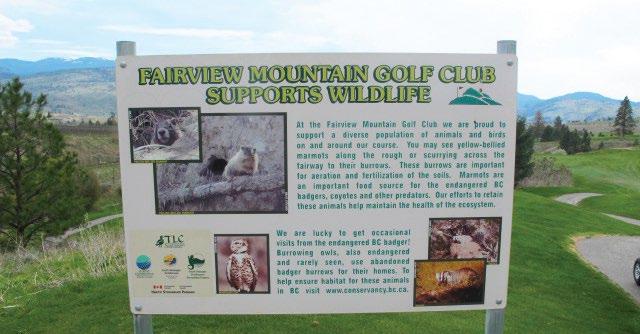

Canada is warming at twice the already alarming global rate and as such, its non-human inhabitants are extremely vulnerable to both climate change and to human activity. There are over 200 land animal species at risk in Canada including the iconic polar bear and caribou. These two species may be the face of climate change in Canada but they are, by no means, the only animals considered ‘at risk’. All across Canada, from the prairies, the lakes and the forests, animals are disappearing.

Canada has over 521 plant and animal species on its Species at Risk list. Once animals are identified as endangered, the next step must be to identify its habitat needs and then to take action to protect that habitat to ensure the survival of the animals in the face of human interference. While we absolutely believe governments must be at the forefront of wildlife and biodiversity protection, there are countless opportunities for communities to work together to protect their own environments.

Long a symbol of the plight of the Arctic and the consequences of climate change, Canada’s polar bears are at real danger of extinction by the end of the twenty-first century if we don’t act soon, according to a recent study published in Nature Climate Change

Around two-thirds of the world’s polar bears live in Canada. Polar bears are reliant on the Arctic sea ice for hunting, mating and raising their cubs. As the sea ice melts, their hunting ground shrinks, meaning fewer hunting opportunities and less time for the bears to fatten up before the summer season each year. Human actions are forcing these apex carnivores to move into closer proximity with communities living along the Arctic coastlines where they have little choice but to forage in human areas and through human waste in order to survive.

Photography: photodune/ Mint Images

Photography: photodune/ Mint Images

Endemic to Canada, the barren-ground caribou is at risk due to human activity in the north of the country. There are over one million barren-ground caribou and they spend much of the year on the tundra, migrating only to the coniferous forests to the south.