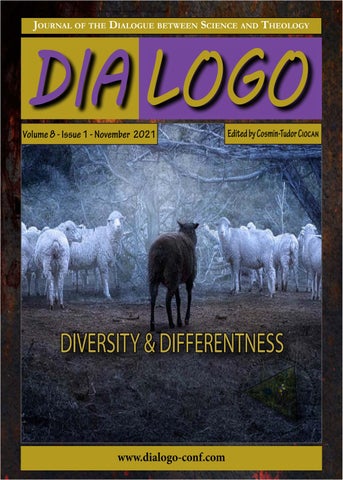

The implications of the Diversity &

Differentness issues are great and they extend to any field of social concern, psychological,

religious, political, and beyond. Diversity is generally understood to encompass race, ethnicity,

class, gender, sexuality, age, and political and religious beliefs. And while in the past it has

focused on strengthening inter-cultural tolerance, currently new ideas about diversity and

inclusion have developed, shifting the focus towards enriching human learning and experience,

so-called ‘unity in diversity.’ Nowadays movements strive to legalize more and more issues

that were previously banned from public display or engagement, while now more than ever

they are promoted, fought for, and socially imposed. A new kind of ‘generations conflict’

emerges from this fact, ‘liberals’ pro-actively engage social impositions of differentness,

while ‘traditionalists’ stand for a more conservative approach. There seems to be no way of

objectively and absolutely proving one way is ‘correct’ while