An Exhibition in Two Parts, June 1 - July 30, 2023

KCAI Gallery, Kansas City Art Institute and University Libraries, University of Missouri / Kansas City

Curated By Ann Wederquist Leahy

“The ‘past’ is… a physical reality approached through memory… leaving a boundless impression which remains the significant motivation of my life.”

Jaymes Leahy, 1990

This exhibit presented Leahy’s works from 1986 until his death in 1994 and was co-incident with the 40th anniversary of the first cases of HIV diagnosed and treated in Kansas City. Leahy’s papers, journals and select works have been accepted into the collection of the Gay & Lesbian Archive of MidAmerica at UMKC.

Jaymes Leahy’s was a lively and humorous creative intelligence, and his work was not content in a single medium. His confident drawing and lyrical compositions built evocative architectures of layered texture and luminous color. He strove in his drawings and patterns, printed textiles and botanical sculptures to realize family memories and their attendant depths of feeling – with a twinkling eye, and a light touch. He found his creative footing at Kansas City Art Institute and pursued a freelance design profession in Europe and America. He returned to study at Cranbrook Academy and then at Yale University. His joyous life and a promising career were cut short by HIV disease in 1994. His talent, his accomplishments, his life should not be measured against the specter of AIDS yet cannot be understood apart from it.

Essays were commissioned from Jason Pollen, Professor Emeritus, KCAI and Ruben Castillo (’12, Printmaking) Visiting Assistant Professor, KCAI. Curated by Ann Wederquist Leahy, organized by Stuart Hinds, Christopher Leitch and Michael Schonhoff. Ann Wederquist Leahy is founder of the Magic Sock Fund, a competitive project-specific grant opportunity for KCAI students. The Fund was established in memory of Jaymes Leahy (’87 Fiber). Michael Schonhoff is director, KCAI Gallery. Stuart Hinds is Curator of Special Collections, University Libraries, UMKC and adjunct faculty at KCAI. Christopher Leitch (’84 Fiber) is an artist and independent museum professional in Kansas City.

In the physical exhibit at Kansas City Art Institute, quotes from Jaymes’ journals and sketchbooks were mounted in the galleries, contemporary with the time period of the works exhibited. Selections are echoed here, in this style, maintaining formatting from the source such as capitalization or punctuation.

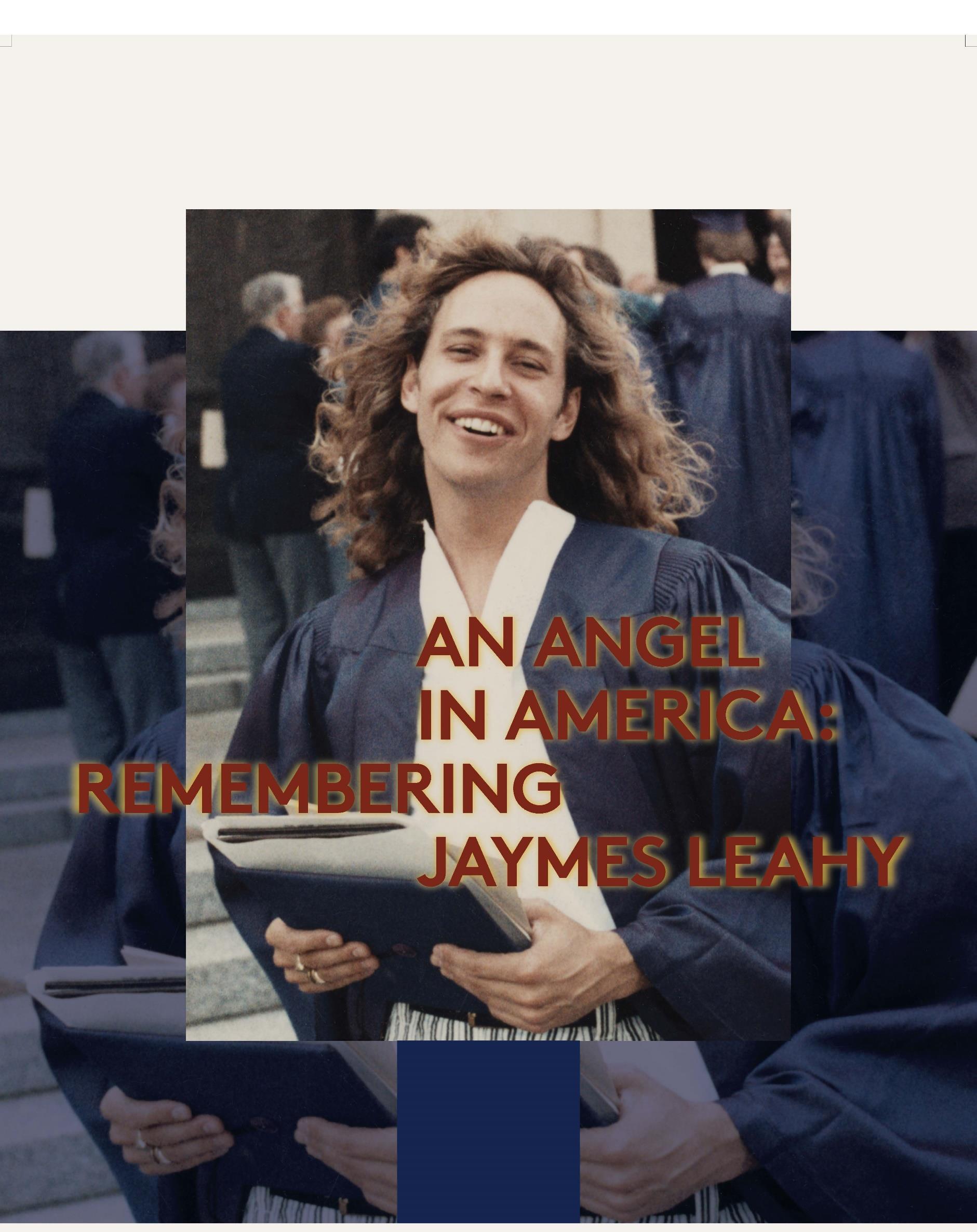

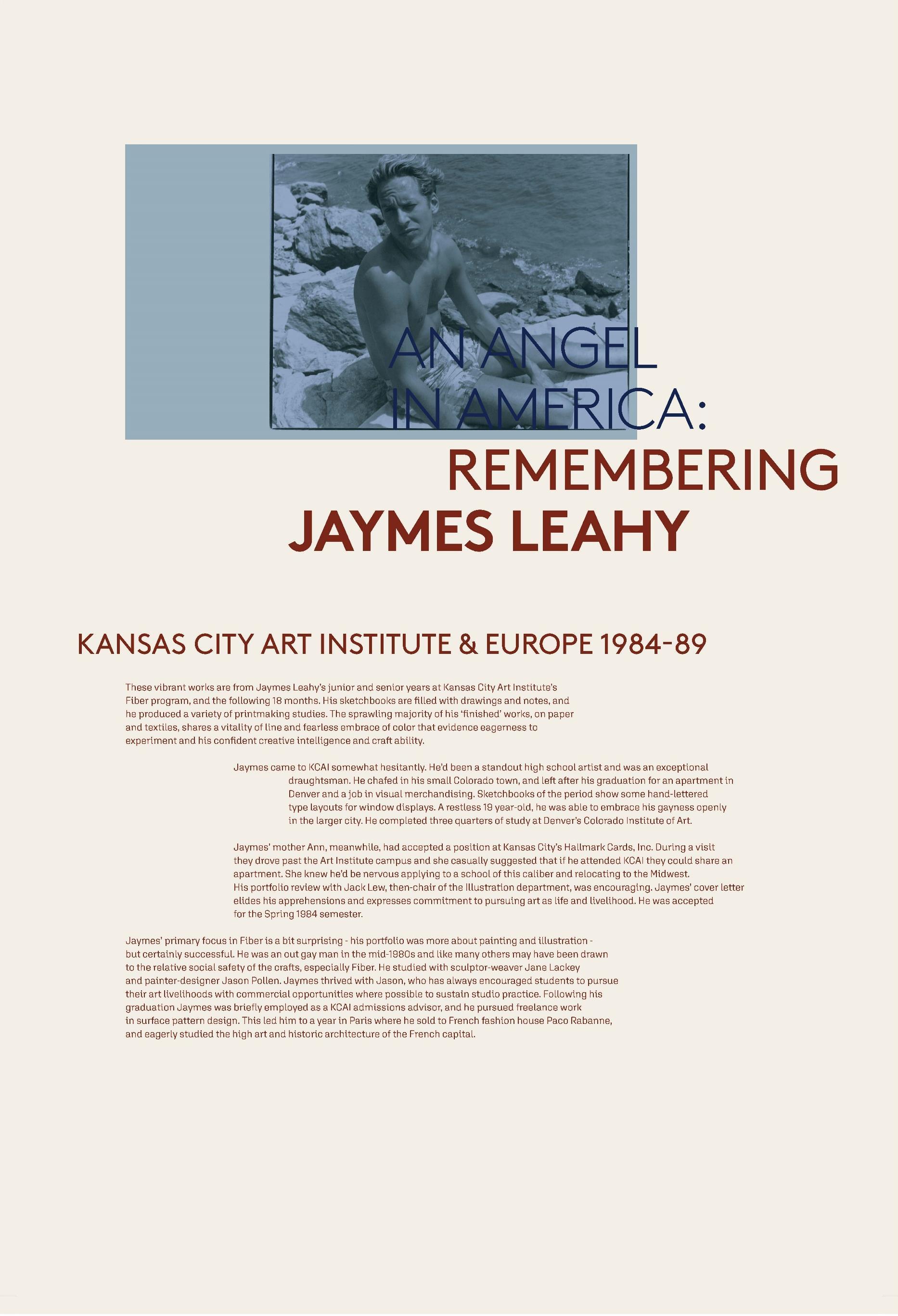

These vibrant works are fromJaymes Leahy’s junior and senior years at Kansas City Art Institute’s Fiber program,and the following 18 months.His sketchbooks are filled with drawings and notes,and he produced a variety of printmaking studies.The sprawling majority of his ‘finished’ works,on paper and textiles,shares a vitality of line and fearless embrace of color that evidence eagerness to experiment and his confident creative intelligence and craft ability.

Jaymes came to KCAI somewhat hesitantly.He’d been a standout high school artist and was an exceptional draughtsman.He chafed in his small Colorado town,and left after his graduation for an apartment in Denver and a job in visual merchandising.Sketchbooks of the period show some hand-lettered type layouts for window displays.Arestless 19 year-old,he was able to embrace his gayness openly in the larger city.He completed three quarters of study at Denver’s Colorado Institute of Art.

Jaymes’ motherAnn,meanwhile,had accepted a position at Kansas City’s Hallmark Cards,Inc.During a visit they drove past theArt Institute campus and she casually suggested that if he attended KCAI they could share an apartment.She knew he’d be nervous applying to a school of this caliber and relocating to the Midwest. His portfolio review with Jack Lew,then-chair of the Illustration department,was encouraging.Jaymes’ cover letter elides his apprehensions and expresses commitment to pursuing art as life and livelihood.He was accepted for the Spring 1984 semester.

Jaymes’ primary focus in Fiber is a bit surprising - his portfolio was more about painting and illustrationbut certainly successful.He was an out gay man in the mid-1980s and like many others may have been drawn to the relative social safety of the crafts,especially Fiber.He studied with sculptor-weaverJane Lackey and painter-designer Jason Pollen.Jaymes thrived with Jason,who has always encouraged students to pursue their art livelihoods with commercial opportunities where possible to sustain studio practice.Following his graduation Jaymes was briefly employed as a KCAI admissions advisor,and he pursued freelance work in surface pattern design.This led him to a year in Paris where he sold to French fashion house Paco Rabanne, and eagerly studied the high art and historic architecture of the French capital.

I would prefer to call [my artistic gift] the ability to see. I feel that it is my true direction in life; to use my abilities, and to create… I welcome the positive stimulus, criticism of my work, and an environment that is accepting and encouraging to creativity.

That which I have seen, felt, desire, interest, inquire, pursue, admire,_____ question, wonder, imagine.

THE POWER EXIST IN WHAT’S MISSING -?

I had the unique honor to be Jaymes’ professor in KCAI’s Fiber Department for three years. Often when I reflect on the joys that come with teaching, Jaymes stands as the quintessentially ideal student. His very presence seemed to brighten the space around him. He was a prolific, dedicated, inspired student who accepted creative challenges with great enthusiasm.

During his time at KCAI, Jaymes brilliantly navigated the art and design sides of what textiles can be. Among his ten thousand fiber “experiments”, marked by a vivid imagination and an innovative and playful use of materials, he produced many works that would and did resonate with the textile/fashion industry. In a bold foray into the world of some of the most revered couture designers in Paris, he sold several of his inspired textile designs.

After KCAI, and a perhaps less than ideal graduate school experience at Cranbrook Academy of Art, Jaymes found and pursued his own unique visual vocabulary and voice.

The works in these concurrent exhibitions convey complex introspective emotions. At first glance, some of these works might just seem like lengths of cloth with repeating motifs. Taking the time to sit quietly with them longer, they reveal the much deeper creative well from which each one emerges.

Ralph Vaughn Williams composed The Lark Ascending, inspired by a poem of the same name written by George Meredith, which tells the tale of a skylark singing an impossibly beautiful, almost heavenly, song. Vaughan Williams was working on The Lark Ascending in 1914, just as World War I broke out.

Jaymes Leahy requested that this musical composition be played at his Celebration of Life ceremony.

Ralph Vaughn Williams’ music and these lines from Meredith’s poem express my feelings for what Jaymes Leahy has been for me.

For singing till his heaven fills, ‘Tis love of earth that he instills, And ever winging up and up, Our valley is his golden cup, And he the wine which overflows To lift us with him as he goes…

Professor Emeritus, Kansas City Art Institute

The works here were made duringJaymes’ years at Cranbrook.There are shifts in imagery and style,and in tools and methods.Colors are as saturated as ever,yet values are more shadowed or aged. He pursues a ‘keystone’ image he first observed in Paris,that morphed into window / vessel forms and similar metaphors of the human figure as container / portal of spirit.Some of this responds to guidance of his faculty, and some evolves amidst the mental and emotional pressures of his changing life.

Jane Lackey was a Cranbrook alum and likely encouraged him to apply.It is not illogical that he sought the imprimatur of one of the country’s finest programs to provide introductions to other opportunities.It is equally probable he sought to test himself,as he saw others of his level and age variously succeeding with seemingly less effort than he applied.

The demands of the Fiber department’s well-known chair,Gerhardt Knodel,were not the permissive, engaging style he’d previously thrived under.Jaymes’ experiments and interests challenged Cranbrook’s particular calls for incisive focus and cerebration.He certainly had the intellectual capacity yet came to understand this approach countered his preferred painterly engagement.He was fascinated with the advanced urban decay of nearby Detroit and collected hundreds of photos,objects and rubbings detailing the evidence of lives lived,buildings and things that figured in his writings and works.

Jaymes’ notebooks are filled with a complex allegory of inner vs.outer and archetypal elements such as fire, earth,blood,flesh,water,spirit.His objects and images are tight and closely defined; his materials evoke layers of history.His forms are symbolic frames and containers shielding fragile components and delicate colors; containment and exposure appear in many works here,and later.Jaymes’ educational experiments succeeded in clarifying his approach to his work. This is unmistakable in the graphic arrangement of his thesis which opposes answers to academic questions with an impressionist elegy on memory and identity.

Only his mother knew the other force in play:Jaymes had learned his HIV+ status in the middle of his Cranbrook study.In the late 1980s an HIVantibody test was two nerve-wrought weeks waiting for results; if positive,a fraught period of seeking and acquiring medical care.There were few doctors who would see patients, and a mosaic of protocols for them to follow.There were no effective drugs for HIVitself until 1996, thus seropositive individuals urgently fought for time until treatment might be developed.Jaymes was thrust into this limbo while navigating intellectual and emotional challenges to his ideas and work.

I spend so much time looking and thinking of what was before, what stood here, what life had passed through this place, and I think there is much to be learned from standing apart from the maddening rush into the future, and looking back, gaining some peace and knowledge in the quiet of that time before my own.

My inspiration to create rarely would come from a book… what moves me to create is that which I know, care for and have experienced… That which I have seen, felt, know, desire, interest, inquire, pursue, admire – question, wonder, imagine. ¬–

I am most drawn to things that stand strong and last through time… Quite possibly I am so drawn to this strength and eternal quality because I am so acutely aware of my own mortality, and weakness…

I walked into Jaymes Leahy’s collection with several positions. First, as a gay cis-gender man who is HIV-negative and born in 1990, almost halfway into what Alexandra Juhasz and Theodore (ted) Kerr name in their Times of AIDS as “the AIDS Crisis Culture (1987-1996).” Secondly, I enter as an artist interested in process, memory, intimacy, place, and the body. Third, as an academic studying queerness and archives. And fourth, I am an alumnus of the Kansas City Art Institute, where Jaymes also studied (he received his BFA in Fiber in 1987). With each of these four positions are several embedded historical feelings and experiences shaping my current view of Leahy’s immense archival body. When we go through someone’s things, we bring our baggage too. Our encounters in archives can be messy, where past and present merge and timelines collapse. We find feelings, good and bad, while performing a crucial recognition to how our shared social experiences impact our everyday. We see, we name, we acknowledge, we affirm, and we address. When we can identify and name our connections to the past, we create transformative opportunities for our futures.

Since 2019 I have been preoccupied with LGBTQ archives in both my personal research and in my teaching. In Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History, Heather Love focuses on histories of “failed or impossible love” to develop a framework embracing all of the bad feelings of queer experiences. “As long as homophobia continues to centrally structure queer life,” Love declares, “we cannot afford to turn away from the past; instead we have to risk the turn backward, even if it means opening ourselves to social and psychic realities we would rather forget.” (Love, 29)

As LGBTQ people, our searches through archives include wading through the various ephemera of loves and losses. The dead are dead, and while we must do right by our historical subjects, we are looking and caring for ourselves. We bring our bad feelings to the archive, and in caring for other people’s materials, we perform care to our own future (what Love beautifully refers to as an “emotional rescue” within the archive). Our desires shape and define the things we encounter and feel within the archive. It creates a murky area of engagement with the past. As Love writes, “like many demanding lovers, queer critics promise to rescue the past when in fact they dream of being rescued themselves.” (Love, 33)

It took everything in me not to immediately ascribe queer meaning to every corner of Leahy’s work. I became flooded by hypotheticals as I saw nearobsessive motifs revisited across his work. Small hand-written notes in his sketchbooks, such as “Body without life again as a vessel” and “life is short––talk is cheap,” felt loud. Could these small musings be ruminations on the AIDS crisis and his own body’s temporality? Not likely (Leahy died from complications with AIDS in 1994 at the age of 32). Were the fixations on particular motifs a metaphor for how he might repeatedly perform his identity in social settings? Who knows. Was his preoccupation with urgent making a way to “stay with the mess” that was perhaps his own queer identity? Of course not (at least not in the testimonies I received from those who knew him). Leahy was like any artist interested in process, design, iteration, form, and the intersections of style & content. While my questions excited me thinking about what these things meant to a queer person in the 80s and 90s, queer themes do not actively present themselves within his work.

And yet, finding queer moments in his work is not unlike finding the queer gestures in the works of Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, John Cage, or Ellsworth Kelly gay men whose identities are sanitized by museums for the sake of their work reaching a wider public. What if all we saw were the queer gestures artists produced, like knowing glances shared by two people from across the room?

José Esteban Muñoz encourages us to see queerness in-between the lines of historical subjects as a way to perform a utopian project based on possibility. On queer evidence, Muñoz writes, “The key to queering evidence, and by that I mean the ways in which we prove queerness and read queerness, is by suturing it to the concept of ephemera. Think of ephemera as trace, the remains, the things that are left, hanging in the air like a rumor (Muñoz, 65, emphasis mine).” As queer people, looking is a form of survival.

Objects form an impression onto us (and vice-versa, we impress additional meanings onto them). The archival body exists as an abstract concept on the finding aid. The reality of these historical objects tells us how things were cared for they seemingly reveal an entire emotional world to us. Traces left by objects are not just the physical artifacts that someone experiences when looking at a collection but also the conditions, the margins, and the annotations. What we find in these minor details can speak volumes. Queer traces are present throughout all of Leahy’s collection, not just in specific

physical moments but in the stories circulating in and around them. As someone who never knew Jaymes, I can see queer affects within his motifs, the obsessions with history and loss, the flamboyance of his output, and the way his work does not cleanly adhere to any one normative working method. All of these encompass the gestural trace left by his presence.

What stands out most to me in Leahy’s work is the level of care to his practice and a clear rejection of fixity. One motif throughout his work is that of the portal to another place. This can be seen throughout his undergraduate work, surface designs, and graduate work at Cranbrook, where even the cover of his MFA thesis has a small, warm photograph of a corn crib from Iowa placed over a view of the industrial coolness of Detroit. Leahy’s work demonstrates the utopic grasp for a future that could never be reached (a hallmark of queer theory and queer experience) in addition to aspects of what Sara Ahmed might analyze as a queer pessimism towards the present. Writing on revolutionary consciousness, Ahmed creates a portrait of a queer person fighting for a happier future and the loss associated with that:

There is nothing more vulnerable than caring for someone; it means not only giving your energy to that which is not you but also caring for that which is beyond or outside your control. Caring is anxious to be full of care, to be careful, is to take care of things by becoming anxious about their future, where the future is embodied in the fragility of an object whose persistence matters. [...] To care is not about letting an object go but holding on to an object by letting oneself go, giving oneself over to the something that is not one’s own. (Ahmed, 186).

Jaymes carefully logged his ideas to paper. In a list related to displacement, he scribbles onto a large sheet of drawing paper, “I think object is representative of emotion.” In his work, metaphor operated as a vehicle to transport the viewer towards a happier future. He created vessels to contain hopes and anxieties as a form of caring for his own past. In tending to, caring for, and engaging with Jaymes work, we build a happier future while also tending to the feelings and emotions of HIV/AIDS. While the material components of Jaymes archival body do not read strictly as queer or of AIDS, the material effects of virus were unavoidable for any queer person at this time. Jaymes work existed during a charged moment of the AIDS crisis, when critical work was being produced to combat the first silence to the virus. I’m encouraged by AIDS activist and cultural producer Theodore Kerr’s reminder that “time is not a line” and that we need to tend to our

present, where we still see the effects of the virus and new HIV infections. Kerr’s writing and social projects work against silence to produce conversations and collectivist frameworks to acknowledge, affirm, and heal.

As part of a conversation with media theorist and filmmaker Alexandra Juhasz, Kerr reminds us that “...the universal can be in the specific, and that by caring for the specific, you can end up caring for everyone.” Queer archives don’t just tell the story of LGBTQ people but of all people. Caring for Jaymes’ materials (and of all materials within archives) as friends, mentors, KCAI alums, artists, designers, people with HIV/AIDS, or gay men is a form of collective caring for our shared futures.

Jaymes said it best in his MFA thesis:

Collecting today is like living a last frontier of discovery; in actuality it is re-discovery of what others have left behind. The need to seek and save is fundamental for me and has resulted in the accumulation of great quantities of goods and materials. Some of the objects are precious, others merely elements to be used in the process of my work. The whole world is a place of discovery, and where I’m willing to look, there is usually something of interest to be found. (Leahy, 8)

Ruben Castillo Artist and Educator

Fall 2023, Castillo was appointed Assistant Professor of Printmaking in the Department of Art at Skidmore College

Apall hung overJaymes’ works when he left Cranbrook and then entered theYale University graduate program.He continued drawing and writing about vessels and contrasts of interior/exterior,history/timelessness.His colors deepened and dulled, and his built-up drawn and collage-layered surfaces became grittier with charcoal and wax.Finished and unfinished textiles from around this period are dark and loosely patterned with painted and printed symbols referenced from sketches and rubbings made in the cemeteries and churches of glorious Paris and derelict Detroit.

Afew new techniques are employed occasionally among these dark textiles and collages,such as portals cut through black revealing undersides and hidden contents or black/blue paint mixed with soil drawn in heavily scraped swaths. Anew pale figure is introduced from several years’ sojourn in his sketchbooks into his compositions: sometimes emulating a Christ in crucifixion,at other moments curled in a fetal ball and cocooned in shadows.

Jaymes struggled with the confinements of an academic rigor from which he strived to benefit but which he resisted working within.His materials choices for a small series of Vessels convey this dissonance.Forms and fields of dulled jewel tones are solidly rendered,but on low-quality found papers mounted onto plain corrugated brown cardboard and wrapped in clear glossy acetate.These works are small,condensed,elegantly suffocating.He withdrew inside himself,in the shadow of his own faltering health and the related absences of close friends atYale from Art Institute days.He leftYale after a year.

Everything’s related.- be in contact with my innernarrative - - PUSH IT IN A NEW WAY –

TELL THE STORY INTO THE MATERIALS

I’m not sure – but I’m guessing the past CAN’T be replaced – If I were to extract a piece – I’m not sure what I could put in its place - ?

IN consideration of image over image –why not use SHEER… for instance, in the situation I’m in at this moment – there is fear, anxiety intense nervousness –Yet on the (surface) ? OR AT LEAST PRESENT –Is strength, hope, confidence. –

The works of Miami Beach are obviously and dramatically contrasted with the later collages and textiles of Yale.His images always were complex and layered,yet mostly battened in two dimensions. In Miami Beach,scumblings and dense scrapings erupted urgently in white,cerulean blue and pencil grey in a myriad of drawings and paintings duringJaymes’ final years.

They are square,or mostly,a rugged impasto unevenly layering white works on canvas, or charcoal and pencil clotted into the fine mesh of pale blue cotton muslin.The vessel image lingers,morphing into and out of definition,frequently fading into unfocused light from a distant window.

Jaymes’ studio days were as productive as ever,especially considering the exhausting necessity of trying to organize his own health care,on the phone and through clinical visits.There were countless protocols for people withAIDS in those early days,and little information seemed to be shared among health care providers.He was also,he told his mother,‘interviewing religions’ which occasioned comings and goings of representatives of various faith traditions.

It’s unclear if he settled on a conventional spiritual path.What is evidenced in Jaymes’ late work is eagerness for tangible meaning.He had accommodated himself to his worsening condition, traveled through the darkness and emerged into his own expansive light.If the past forJaymes was “a physical reality approached through memory” then his future,whatever that could be,would likewise be reached through acts of making that meaning,as long as he could.

All of these things are of a time not my own, all of them icons of a time past, of forgotten eras, forgotten personalities, places and events that I can only imagine.-

Do you want the original identity of your materials to show through…to leave things slightly unfinished – locks out some of the superconscious –allowing a little mystery and space…

I cannot be fueled by fear and sadness –though there is so much there –I must be driven by hope and Knowing…

JOSEPH BACON

JESSICABARBOSA

MAXBELANGER [MAXADRIAN]

ANTHONYBENNETT

JOHANNABROOKS

MICHELLE CHAN

KAYSIE COLLENS

AVERYDENNISON

MARLIE ESCOTO

JACKOB GRAVES

RACHELGREGOR

Jaymes Leahy died in Miami Beach,Florida on June 15,1994. The Magic Sock Fund was established at KCAI in his memory by his mother, AnnWederquist Leahy.Project grants to students are used for expenses related to mounting an exhibition,materials and supplies or other academic efforts.

The Fund takes its name from a family tradition in theWederquist-Leahy household.An old white sock was hung on the doorjamb atJaymes’ grandmother’s kitchen.He,his brothers and cousins were encouraged to search the contents of the sock on each visit; because the sock was ‘magic’ the kids never knew what they’d find: small toys,some candy.

The Fund was first granted in 1996 and since then has benefited projects across all disciplines.However modest,the grants honorJaymes’ memory and encourage applicants to expand their capacities and to explore new ideas.

SupportThe Magic Sock Fund inJaymes’ memory: click the logo below.

JORDAN HAIDUK

ROBERTHEISHMAN

MATTJACOBS

JESSLYNJAKOBE

ANNAKAMERER

CALDER KAMIN

MARYKUVET

LINDALAY

ROBIN LEWALLEN

ISSAC LOGSDON

SAMANTHALUDWIG

EVAN MADDOX

DANTE MOORE

PAULINAOTERO

DESIRAYPOLK

ZOE RICHARDSON

HANNALROSENTHAL

VAUGHN SANCHEZ

CHASETRAVAILLE

SAMYATES

LINGZHIYUAN

…in what ways can I depict the intense fear and worry I feel – at the same time rejoicing and being terribly happy?

I’m so filled with a love of life, and what’s Around me – I can’t help but grasp a Moment – and be happy.

It’s when I look forward to what may be…

These dynamic drawings were executed byJaymes Leahy likely between 1988 and 1990 during or just after his time at CranbrookAcademy of Art. They depict with accuracy and energy the landscape of his family’s Randolph,Iowa farm property.

Memories of the farm,and the formative years he spent there with his grandparents, parents,cousins and siblings,feature prominently in his master’s thesis at Cranbrook. The demands of the Fiber department’s well-known chair,Gerhardt Knodel, were not the permissive,engaging style he’d previously thrived under at Kansas CityArt Institute.Jaymes’ experiments and interests challenged Cranbrook’s particular calls for incisive focus and cerebration.He certainly had the intellectual capacity yet came to understand this approach countered his preferred painterly engagement.

Jaymes’ educational experiments succeeded in clarifying his approach to his work.This is unmistakable in the graphic arrangement of his thesis which opposes answers to academic questions with an impressionist elegy on psyche,memory and identity.These drawings may be seen as a vigorous reclaiming of his personal and painterly legacy.

The materials in theTable Cases are representative of Jaymes’ extensive archive: sketchbooks,journals,research files,photographs and found objects. These are records of his study and artistic practice,of personal and professional friendships,of curiosity and reverence for the natural world and remembered human passages through it.It was deemed proper to focus their exhibition at the archive where they are beingpreserved and made available for research.

My son, Jaymes, died two years ago. He had tested positive in 1983 after calling me to tell me he was going to have the test done. When I think back, I believe that call was the beginning of my "education."

Jayme learned everything he could about AIDS for the next 11 years, because he wanted to live as long as he could, as well as he could. He called doctors every month to see which ones took Medicaid; he called 1.880 numbers to get information on the latest treatments; he wrote out lists of questions to ask his clinic doctors; he had blood tests, eye tests; he arranged for social security disability payments and showed me the papers listing his condition as "terminal'' and "patient may live two years" handwritten by a sensitive social worker. He exercised, he ran, he rode his bicycle, he changed his diet, he stopped drinking alcohol in any form. he meditated, he went to a weekend seminar on thinking positive, he said he knew stress was bad for him. He took vitamins, drank protein powder, and in the last two years of his life, he tried vitamin C and gamma globulin IV, and went to an acupuncturist weekly.

For 11 years, he called me. He talked to me and with me. He told me the names of his medications, and why he was taking them. He questioned his health care-he questioned every medication that was recommended. I started reading, too. I purchased a book listing treatments, side effects, dosages.

Jayme said to me once, "If love really has the power to keep you alive, Mom, I think between the two of us, there's enough love to do that." We had the love we didn't have the power over the virus. It kept replicating, changing his days and nights, and taking away his vitality, but not his determination. When Jayme had found out he was positive, he said, "I don't want to talk about this right now. I'll let you know what I decide." It took him six months. He called and said, "I want my life to be like anyone else’s. I want to stay in school, I want to have goals, and I don't want everyone to know, because I don't want them to look at me and immediately think, 'Is he sick?'" He continued in school, then went to graduate school, then taught, then was accepted into another graduate school and at the same time was teaching at Parsons in New York City.

But right before Christmas 1992, he called to tell me he thought he had pneumonia. I caught the first plane and waited with him all day. At 9 pm they told him he'd have to be taken by ambulance to another hospital where he

would be admitted. At 11 pm I was allowed to go to his room. They had placed him in a room in a locked mental ward, to isolate him from the other patients, they told me. The room was filthy with what looked like vomit on the walls. That was the beginning of another kind of education for me.

I watched how Jayme took an active part, as sick as he was, in his care at that hospital. I learned how to confront nurses who didn't do heparin flushes, to keep notes on all medications the doctors were prescribing, to ALWAYS check what I had written down against what was brought to Jayme to take, and to go to the nursing supervisor and the hospital patient advocate when I couldn't get a problem corrected. I asked for and received all of his medical records, when he left. It was a hassle, but they were his.

He was in the hospital that time for three weeks. He asked me to bring tshirts and boxer shorts, slides he had been working on, food, music tapes, and personal items. I didn't know it then, but now I know it was about his own identity. He must have instinctively understood this, because he did it every time he had to stay in the hospital. He would ask the hospital personnel their first names. what they did, he complimented them on their appearance or technique, and laughed at himself or me. We began to keep crossword puzzle books on hand and would test their abilities when they came in the room. They, in return, came to know him and like him. He wasn't

"another person with AIDS." He was Jaymes. He questioned what they did, what medication he was given, even asked them to check the nurse's journal for contraindications for medications. But he didn't confront. He had always laughed at my mother's ability to come up with an adage that applied, and the one she would have used for him in that situation was, "You can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.'' I grew up thinking you did what a doctor told you to do. Jayme questioned every decision the doctors made. Sometimes he agreed, but a lot of times he refused to go along and made them rethink and re-prescribe.

In April 1994, I went to visit Jayme and the doctor asked if I could stay. I had tried to go see him every three months for over a year, and knew his physical body was giving out. He'd say, "Mom, I'm like an old man." His appetite had diminished, he took naps, he couldn't sleep at night, his writing had changed. But now his teaching was coming from a place I couldn't experience. Jayme taught me how to just BE WITH HIM, by asking me to do just that. He'd say, "Mom, come sit with me." He'd ask me to take a nap when he needed one. He'd say, "Don't you get tired?" when I'd be busy cleaning or doing dishes, and I thought about that question. I think what he was really saying was, "I can't do what you can anymore. I can't stand up and do the dishes, even. I have to hold myself up with walls and furniture. and you are my mother and you can do more than I, so would you stop when I need to

take a nap, so that I don't have to be reminded?" He was asking me to be quiet, to be in his space, to be IN the life that remained to him. He was asking me not to bring all my outside junk into the only space left to him.

And then, after a Friday afternoon visit with his doctor. he said, "Mother, you have to tell me when you're ready to let me go." We’d had that conversation before, but this time the doctor had told him he either had to fight with everything he had, or let go. On Sunday afternoon, I told him I was ready. On Monday morning, he called the doctor, then the hospice people. He stopped all his medications except for diflucan. The doctor prescribed morphine, a small dosage. Jayme had me call the hospital to see if they could remove the PIK line from his arm. One of several nurses who remembered him pulled it from his arm with one continuous, swift motion. Then, sitting in the wheelchair, he got lots of hugs and we went home.

Jayme had told me that one of the things he hated most about being sick was it changed the way people reacted to him. He felt it made them not want to touch him, and they always seemed to assume he only wanted to talk about his illness. It really bothered him, because he was the same person he'd always been and he loved to talk and be social. He wanted to talk about EVERYTHING else, before he’d talk about his illness. So, that last week, we watched “the Wheel”, had a visit from Betty (Jayme hysterically

proclaimed, “I have a dwarf for a pastor!”) ordered pizza and a movie and laughed and were happy. That's truly how I remember that last week. He ordered a vegetarian burrito on Tuesday night and ate it while I went to the airport to pick up our friend. On Wednesday morning he decided he wanted to go to the hospice unit at the hospital, and he died quietly at noon.

He had asked me over and over if I’d be OK and I had reassured him I would be. I think now that he had been ready to go for months, but waited until I was ready. He didn’t want me to be alone, and he asked who I wanted to be with me. He had left his DNR form and his will, made his scholarship wishes known, and placed letters to his two brothers and myself in his journal where they were found four months later.

Jayme taught me about the disease, and he taught me about acceptance. He led me though the process of his death and asked me to celebrate his life with his friends. He shared his dreams, his friends, his apartment, his BATHROOM! with me. At the memorial services, where people told about how they had met, or how they came to be named (by him) there was as much laughter as crying, I think, because Jayme was an energetic, funny, spontaneous individual. In reality Jayme took care of me. He gave me time, gave me knowledge, he did everything he could to make sure I was OK. More than anything, he gave me love.

I cannot tell you in words what that sharing of our lives means to me now.

But I can and do encourage each of you who live with AIDS every day to talk to your parents and families, to share your lives with them, to educate them, to drop all the reasons and justifications for not allowing them into your life, and maybe just let them into your heart.

Maybe they won’t understand. Maybe they are prejudiced and controlling, and maybe they are more afraid than you can imagine. Perhaps they cannot, or will not, change. You don’t have to either. This isn’t about judgements, this is about you. You are the one who can leave a legacy of education. You can be the one who is leading the way, who is teaching, who is giving to them. In my experience, there is still sadness, but there is no guilt, no despair, no feelings of "if only I had..." I am living my own life. I am laughing. enjoying the days, exact ly as I would wish life for Jayme, had I died instead of him. I know he wouldn't want me to waste a minute of it.

Reprinted from Resolute Journal, December 1996

A copy of the Journal is included in Jaymes’ papers presented by Ann Wederquist Leahy to the Gay & Lesbian Archives of Mid-America, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKC University Libraries, Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City Art Institute

Gallery 1 – KCAI

East and north walls

Surface pattern designs for textiles or paper c. 1985-88

Gouache, pencil, ink, dye on paper; 20 pieces, dimensions vary

Textile surface pattern designs c 1985-88

Dye and discharge chemistry, pencil, pigment on cotton, rayon and silk; 38 pieces, dimensions vary

West wall

Printed textile yardages c 1985-88

Monotype, block print, hand-painting, dye, pigments, discharge chemistry on cotton, rayon and silk; 7 pieces, dimensions vary

Royal Blue c 1988

Printed silk crepe de chine; 36 x 108”

Collection of Bonnie Thomas

Gallery 2 – Cranbrook Academy

East wall

Vessels, c. 1989-90

Discharge printing, paint, pencil on cloth; 9 pieces, dimensions vary, c. 12 x 9”

Dimensions are given in inches, h x w x l

Vessels c. 1989-90

Pencil, charcoal, watercolor on papers; 10 pieces, dimensions vary, c. 12 x 9”

Photos

Top: Thorn Gate, Bed of Roses, and Vessel 1989-90

1990 installation view at Cranbrook Academy of Art

Scan from period print

Bottom: Thorn Gate and Vessels 1990

1992 installation view, group exhibit at Sean Kelley Studio, Kansas City, MO

Scan from period 35mm slide

Vessels 1989-90

Plywood, glass, dried flowers, wax; each 42” h large: 12 x 12”, base 9 x 9” small: 8-3/4 x 8-3/4”, base 6 x 6”

Glass House 1989-90

Wood, glass, flower petals; 19-1/2 x 18 x 24”

North wall

Vessel 1989-90

Paint, charcoal on canvas; 80 x 30”

Gallery 3 – Yale University

North wall

Twined Vessel 1989 90 Paint, charcoal on canvas; 80 x 24”

Textures, vessels, architecture 1991-92

Chalk, charcoal, pencil, paint, wax, glue, collage on found papers; 5 pieces, each 19 x 9 x 1/2"

Vessels c. 1992-93

Paint, charcoal, chalk on canvas; 5 pieces, heights vary c. 9 – 14”, width 4”

Vessels c. 1992-93

Charcoal, chalk on paper; 2 pieces, c. 12 x 9”

East wall

Figure study, unfinished c. 1992-93

Printed and painted rayon challis; 45 x 144”

South wall

Structure studies c. 1990-91

Printed paper encapsulated within pierced cotton muslin; 4 pieces, each c. 22 x 22”

Structure study c. 1990-91

Printed, painted, collaged, cut cotton muslin; 24 x 40”

Vessels c. 1990-1

Discharge, paint, pencil, sgraffito on cotton canvas; 2 pieces, small 9 x 7”, large 14 x 10”

West wall

Figure study, unfinished c. 1992-93

Printed and painted rayon challis; 45 x 108”

Texture/structure study, unfinished c. 1991-92

Bleached and painted canvas and muslin stitched to cotton muslin; 60 x 40”

Gallery 4 – Miami Beach

North wall

White vessel 1992-94

Chalk, pencil, paint, on found canvas; 36 x 72”

Blue squares 1992-94

Chalk, pencil, paint, on cotton muslin; 12 pieces, each c. 12 x 12”

West wall

White squares 1992-94

Paint, pencil, charcoal on canvas; 10 pieces, each 14 x 14”

East wall

Icon sketches, 1992-4

Pencil, ink on vellum; 6 pieces, each c. 12 x 12”

folded dimension

Angel Icons, 1993-4

Pencil and chalk on paper; 2 pieces, each 14 x 11”

Vessels, 1992-4

Pencil, chalk, charcoal, watercolor on paper; 4 pieces, dimensions vary from 10 x 10” to 16 x 11”

University of MissouriKansas City

Framed Works

The Farm Drawings, c. 1988-90

Charcoal on paper; 10 pieces, each 24 x 18

Table Case A

Photographs 1985-94

Photographic prints on paper; sizes vary

In this era before electronic photography, paper prints were the standard method of preserving and sharing images of life and work

Table Case B

Sketchbooks and journals 1985-94

Mixed media in commercial sketch books; sizes vary

Table Case C

Sketchbooks and journals 1985-94

Mixed media in commercial sketch books; sizes vary

Table Case D

Studio boxes and tabletop items 1985-94

Wood, paperboard, found objects and natural materials; sizes vary

Table Case E

Day planners and telephone note pads 1985-94

Mixed media in commercial note pads; sizes vary

In this era before portable telephones, the household instrument was connected via a cord to a wall outlet thence to the wired telephone system. For Jaymes, it was common to keep a note pad by the telephone, and nearly everywhere else, to make notes about incoming calls, and to doodle in when the mind wandered.

Table Case F

Letters, papers 1988-96

Memorial booklet 1994

Mixed media on found commercial and art papers; sizes vary

AnAngel inAmerica: Remembering Jaymes Leahy

Curated byAnn Wederquist Leahy

Organized by Stuart Hinds and Christopher Leitch

The curator and exhibit organizers express appreciation to Kansas CityArt Institute,Nerman Family President Ruki Neuhold-Ravikumar,and the talented staff for welcoming this exhibit to the campus. Special thanks to Michael Schonhoff,Director of the KCAI Gallery for his good-natured encouragement and his generous support.

The curator and exhibit organizers express appreciation to the administration and talented staff of the University Libraries / Miller Nichols Library at the University of Missouri-Kansas City for welcoming this exhibit to the campus.

Allen Hori,principal at Bates Hori bateshori.com,a Cranbrook classmate of Jaymes Leahy,generously provided graphic design services for the exhibit.His sensitive hand and warm imagination have contributed immeasurably to the quality of this project. They are adapted in this catalogue with gratitude.

The exhibit organizers express profound gratitude to the Curator,Ann Wederquist Leahy,for permitting them the privilege of honoring their friend and colleague Jaymes Leahy through this exhibit.

Thank you to BeverlyAhern for her encouragement and for her generous support of the Magic Sock Fund.

Appreciation to Sean Kelley for his memories and advice.

The title of these exhibits referencesTony Kushner’s 1991 two-part playAngels inAmerica:A Gay Fantasia on NationalThemes. The play is a complex,metaphorical,symbolic examination of AIDS and homosexuality inAmerica in the 1980s.

Anote on titling and dating of works in the exhibits.Titles given by the artist are used when known; otherwise,the simplest description is made by the curator and organizers.Dates are another matter;Jaymes was not careful about applying dates to specific works. These are confirmed when exhibition dates are known or works are shown in photographs of known period; when some date-specific note is applied to the object (such as a scrap of tape with ‘KCAI’ on the back); when astyle / colorway fairly definitely places a work within a certain period.We apologize for any mistake,and encourage artists (and others) to do your future biographers a favor: date your works and sketchbooks.

exhibited courtesy the collection of AnnWederquist Leahy,unless otherwise noted.

AN ANGEL IN AMERICA: REMEMBERING JAYMES LEAHY Catalogue of the Exhibition © 2024 by Christopher Leitch Studio Essays by Jason Pollen, Professor Emeritus, KCAI; Ruben Castillo Assistant Professor of Art, Skidmore College; Ann Wederquist Leahy, independent artist. Exhibition graphic design elements by Allen Hori, Bates Hori. Exhibit photography by T. Maxwell Wagner, Kansas City.