THE IN-BETWEEN:

Transition Space for Former Foster Youth

PROJECT BACKGROUND |

YBB students participated in three design workshops over the course of the semester. They will continue to play an important role in the design of the project as they advocate for their peers who will one day live in this building.

Project Statement:

This is a project about human-centered and participatory design. If design thinking is the intersection between viability, desirability, and feasibility, then it should be applied to the world’s toughest challenges, and used to address the needs of our most underserved communities. I believe that almost any problem can be solved by a designer. I am dedicated to pursuing meaningful work, and I am inspired to make a change in the world through design. We have the power to shape the future. Let us move forward with the audacity to challenge traditional ways of thinking and make this world a better place for all.

Project Partners:

This thesis project was sponsored by YouthBuild Boston (YBB). YBB is an innovative design/build and workforce development organization that develops high-quality, energy-efficient projects in underserved communities. YBB has a long history of developing housing for people who would not otherwise have a home of their own, and their projects serve as the training grounds for young people interested in starting a career in the building trades. YBB is committed to the development of housing for one of the most vulnerable populations in our community- a community of which many past and current YBB students are a part. The project will provide opportunities for students to strengthen their community through the development of safe, stable housing for their brothers and sisters in need. It will be the first of its kind: a model for how to develop housing that heals and empowers- built FOR young people BY young people.

Boston’s annual Homeless Census shows that on a given night, 360 youth and young adults are either sleeping in a shelter or on the street. Additionally, many young people experiencing homelessness are not in a shelter or on the streets, but are ‘doubled up’ or couch surfing from one unstable situation to another. In November 2019, the City of Boston, the Boston Youth Action Board, and 170 public and private partners released the “Rising to the Challenge” initiative; a new plan to prevent and end youth and young adult homelessness through concrete investments in housing and services. YBB is especially equipped to help address this issue because of their ability to leverage partnerships that enable them to develop quality housing at significantly reduced costs. YBB works closely with the city to identify and acquire building lots and neighborhood approval. Their many vendor partners, along with industry partners including Skanska, Shawmut, Stantec, and the New England Regional Council of Carpenters provide donated materials and training. The end result is high-quality, energy-efficient housing at a lower cost.

This new model for permanent, supportive, communal housing will be replicable all across the city as new construction or renovation, and YBB will partner with other nonprofits to provide case management and other social services. The project will strengthen nonprofit networks in Boston and help cultivate partnerships between leading edge organizations whose innovative models are helping to make the world a better place. YBB has begun conversations with organizations such as More Than Words and Breaktime Cafe, who provide job opportunities for youth experiencing homelessness. Other organizations who successfully serve this demographic, such as Home for Little Wanderers, Children’s Services of Roxbury, and Bridge Over Troubled Waters may also be interested in partnering. YBB has already garnered strong support from funding partners, and the City of Boston has committed to providing support by way of lot acquisition and potential subsidies for the project. YBB’s partners, staff and students have played an integral role in the development of this project. Thank you to all who have contributed!

THESIS SUMMARY

This image by Josh

was originally created as street art and has been turned into the limited edition screen print shown above. The screen prints are sold by an organization called

When you purchase this screen print, you also purchase five nights in safe accommodation for a young homeless person in London.

Jeavons

‘Street Stories’.

Thesis Statement:

Former foster youth need a home that heals and empowers in order to successfully transition from childhood to adulthood, and from foster care to independence.

Abstract:

Approximately 23,000 kids age out of U.S. foster care each year, and 40-50% are homeless within 18 months. Each of these young people has experienced various types of trauma, and many of them never have a chance to heal before they are abruptly forced into adulthood at age 18. Yet 70% of former foster youth say they want to attend college, and many resources exist in our city to help them get there. How can architecture amplify the assets that will help a young person successfully transition to adulthood, while helping them recover from past trauma? Inspired by a cohousing model and situated in a specific cultural context which considers the past, present, and future of permanent supportive housing, the design portion of the thesis project incorporates the latest research in trauma-informed design to propose a new building typology for permanent, supportive, communal housing that will provide Single Room Occupancy (SRO) for 8-12 young people.

METHODS OF INQUIRY |

The Boston Architectural College defines the ‘Methods of Inquiry’ as the methods used to seek knowledge that can help answer the questions central to the thesis. These methods are based on gathering observable, empirical, and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning. They consist of a collection of data gathered through observation, experimentation, and formulation. They are a testing of the thesis abstract, and an answer to the question of how one will investigate the thesis. Whereas means are defined as techniques towards achieving or enacting a method, a method is seen as a larger, more overarching idea about approaches.

created by

I came across an article recommending that youth service providers ‘shift from Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement’ based on something a young person who had experienced trauma said: “I am more than what happened to me, I’m not just my trauma”. The author suggests that the term ‘Trauma Informed Care’ focuses on the trauma itself, rather than on the person who has experienced it- it is deficit based rather than asset driven (3). These young people are more than what happened to them. They have strengths and skills and passions just like any other whole person. The image is inspired by the Japanese art of Kintsugi, through which broken pottery is repaired using a special lacquer dusted with powdered gold. Philosophically, kintsugi treats the breakage and repair as part of the history of the object, rather than something to disguise. The image depicts a collection of memories- good and bad, that are all part of what shape a person.

(Image

Christine Banister using photographs sourced from Google Images, which have been labeled for reuse. Photographers unknown.)

1 |

Can I develop a set of design principles that address the very specific needs of young people as they transition from childhood to adulthood, and from foster care to independence? Means: Conduct thorough background research and interviews to develop a set of design principles specific to the thesis.

2 |

Can I create a new building typology based on this set of design principles? Means: Put the design principles into built form by developing a generic preliminary design concept that incorporates the extensive research done on this topic.

3 |

Can this new typology be adapted to fit a variety of sites? Means: Test the design on real project sites in collaboration with project partners and stakeholders.

TERMS OF CRITICISM |

The Boston Architectural College defines the ‘Terms of Criticism’ as the terms (language, measures, and criteria) applied to inquiries and findings that help readers evaluate the project’s worth. They are a judgment of merits and faults of the work- their purpose is to evaluate, not to find fault. They are an answer to the question of how the outcome is to be measured.

(Image created by Christine Banister using photographs sourced from Google Images, which have been labeled for reuse. Photographers unknown.)

1 |

Did I identify tangible ways that the built environment can help address the specific needs of young people as they transition from childhood to adulthood, and from foster care to independence?

2 |

Did I translate this set of design principles to built form through the creation of a new building typology that helps to address these specific needs?

3 |

Did I test the new typology on a variety of sites to see how it might be adapted for a specific project?

neighborhood integration connection to nature

PROJECT METRICS |

The Project Metrics let us know if our building is working the way we want it to, and help us measure the outcomes of this new typology. They are the result of research and early workshops with youth, and they are the set of standards from which all project decisions are made. The list was developed after careful consideration into what makes a home healing and empowering for the young people who will live there. The metrics are broken into four categories of equal importance: Mental, Emotional, Personal, and Networking.

variety and choice connection

NETWORKING: Web of Interdependence | Neighborhood Integration

When we say that we want a young person to transition out of foster care and into independence, what we really mean is that we want them to become interdependent. When someone is dependent, their life is built on a foundation that must be maintained by others, and when something goes awry or is pulled out from under them, their whole world crumbles. If they are independent, it is true that they no longer rely on others, but also others do not rely on them. Healthy, productive adulthood actually depends on cycles of interdependence. When a person begins to develop a web of interdependence, they can count on others, and others can count on them. If something goes awry and is pulled out of their web, the person easily bounces back with the help of their support system. Building a web of local supports helps the young person integrate into their community and gives them a solid, stable base of support.

EMOTIONAL: Community | Belonging | Health | Love

Feeling like part of a community is important for human health and well-being. Depression and anxiety are reduced when a person has strong ties to other people. For many people, these ties come in the form of family bonds. For former foster youth who may not already have strong ties, it is important to establish a strong connection with the other people who are a part of this community. The service provider should plan community-building programming, and each building should have at least one semi-public community space where formal and impromptu social events can be held. The building design should encourage more social interaction between residents by locating private spaces directly off of this community space. This ensures that the residents encounter each other in passing at least periodically, which will help to encourage conversation and cultivate stronger relationships.

MENTAL: Safety | Permanence | Order | Cleanliness

Safety is important for any residential building, but this particular demographic has an increased need to feel especially safe. Case studies indicate that keyless entry systems, and in particular, a fob system that allows for special permissions and reprogramming, tend to be most successful. Each resident unit should have a way to see who is at their door, as well as view a camera that records people entering the front door of the building. A note about time and space: It is important for the young people to feel a sense of permanence in their home. They should not be concerned about aging out or being asked to leave because they started earning too much money. The youth who live in this building should be given as much time and space as possible in order to feel like they have a permanent home.

A clean and tidy space is conducive to good mental health. The building manager should conduct monthly maintenance checks to ensure that each resident’s space is in working order and is being kept clean. Clutter can be a safety concern, so if residents have too many belongings in their studio, they should be provided information about off-site storage. The spaces should be planned in such a way as to make it easy for residents to maintain order in their own space. Materials specified should be durable and easy to clean. Hard flooring is better for indoor air quality. Some residents may move in with all of their many possessions and will need someplace to store their things efficiently. Other residents will move in with nothing. Storage should be designed in a way that can be easily kept tidy, and appears beautiful whether empty or full. Each resident should be provided with a safe for keeping important papers and identity documents. A laundry closet should be provided (on every floor, if possible), and hampers on wheels can make getting there and back with a load of clothes easier.

PROJECT METRICS |

PERSONAL: Ownership |

Privacy | Individuality

Humans, even within a specific subset of our country’s population, come in all shapes, sizes, colors, and genders. People also have different physical abilities, sexual preferences, cultural backgrounds, and tolerances for things like heat and humidity. In order for many different kinds of people to feel comfortable in the same space, it is important to design with consideration for the widest range of human needs and preferences as possible. Universally designed kitchens and bathrooms eliminates the need for specifically designated ‘handicap units’ and makes the spaces more comfortable for all people. Each resident should have the ability to control their own HVAC. Furniture should be chosen by the resident, or adaptable so that it meets the needs of many different people. For example, a twin bed might be sufficient for many teens, but a 6’5” man will probably want a king. If residents are able to customize their environment, such as chose their own paint colors (from a pre-selected color palette), they will be more inclined to take care of their space. When it comes to the private rooms, there should be a variety of options to choose from. For example, some units might open to outside, and others to inside. Some might have shared baths, while some have private baths. (benefits of scattered site model)

A graduated approach to privacy helps solidify a sense of ownership for each resident. For example, picture the cliche american home and imagine an interaction between neighbors. A neighbor may approach your home on the street or sidewalk, waving hello as they pass. If you like this neighbor and would like to initiate a discussion with them, you might open the gate on your white picket fence and invite them to stop and chat. If the conversation gets juicy and you’d like to discuss further, you might invite them to come onto your front porch and enjoy some lemonade while you sit in your wicker rocking chair. If this person is a friend, you might even invite them into your living room. But only if you are very close with this person will they be invited into the private spaces of your home, such as your bedroom. The multiple levels of privacy allow a homeowner to control how much access they give to others. This can be very reassuring for all people, but especially individuals who might have reasons to be wary of people around them. Care should be taken in establishing sequential levels of privacy for each resident. Thresholds between spaces are crucial moments in the design where transition should be thoughtfully considered- A small private space should not be located directly off of a large public space without any kind of buffer. For example, each resident might have their own ‘front porch’, or raised stoop off of the common lounge space. Each studio space could be composed of private to semi-private ‘zones’ to allow for greater levels of privacy in the most intimate areas. Acoustical privacy is also important, and the building design should include sufficient acoustical insulation, or utilize strategies like closets between rooms to provide acoustical buffers between spaces.

Initial brainstorming workshops with youth led to the creation of a set of metrics to help us measure the effectiveness of our new typology. In the ‘verb-storming’ workshop pictured, youth were asked to write in pen things that they might do in their home (shower, eat, sleep, etc.), then with blue marker list anything they might do to help them unwind or cool off. The group listed healing verbs like laugh, exercise, and listen to music. Next, they were asked to write in green things they could do to feel like they are in charge of their own lives. The list of empowering verbs included things like signing up for programs at YouthBuild Boston. The conversations I had with the young people during these workshops were enlightening, and at times, surprising and confusing to me as an outsider. Each workshop greatly altered my thinking and had a profound impact on the project direction.

DESIGN MODIFICATIONS |

The Design Modifications are the specific architectural moves taken to help achieve the goals of the project as outlined in the Project Metrics. They are flexible and adaptable, and should be front of mind when making decisions throughout the design phases of project development.

Some of the young people who participated in the design workshops felt very strongly about the ‘connection to nature’ guideline. There was significant discussion about the need for plenty of natural light and outdoor space. The conversations led to a thorough investigation into building organization and layout based on climatic considerations.

circulation as community space

redistribution of living space

neighborhood integration

neighborhood integration

8 makes a community

redistribution of living space

8 makes a community

privacy gradation

variety and choice

space

8 makes a community

connection to nature

8 makes a community

privacy gradation

privacy gradation

privacy gradation

redistribution of living space

circulation as community space

circulation as community space

neighborhood integration

privacy gradation

connection to nature

circulation as community space

connection to nature

variety and choice

variety and choice

redistribution of living space redistribution of living space

neighborhood integration

variety and choice

variety and choice

8 makes a community

neighborhood integration

connection to nature

connection

privacy gradation

circulation as community space

connection to nature

circulation as community space

The typology can be adapted to any site in any part of the United States. With the support of YouthBuild Boston and partners, Boston was used as a test case for this project. The first consideration when choosing a site is vicinity to the primary service provider. Since this is considered Permanent Supportive Housing, with intensive case management of a 1:15 ratio staff to youth, service providers with this model would be an ideal fit.

Typically under each level of case management, there are two kinds of housing available: project based and scattered site. Many intensive case management providers prefer the scattered site model because it allows for more choices in housing type, a greater level of independence for the residents, and better integration into the neighborhood. However, my research showed that these benefits are only theoretical. In reality, residents are often limited to high crime, high poverty areas and tend to feel isolated. I like that the project-based model provides a strong sense of community, better amenities, and more efficient case management with all of the clients in one location. However, by combining these two different types of housing under a new ‘Independent Community’ classification, residents will receive the benefits of both models. For example, even when all of the units are located in the same building, they don’t all have to be the same. You can provide the benefit of choice that is typically associated with scattered sites by having some of the units open to the outdoors, some to inside, give some of them private baths, and have others share a bathroom. This idea and others are built into the Design Metrics and Modifications described on page x.

In addition to service provider vicinity, other site considerations include safety, transportation, and recreation. This map identifies a number of potential service providers (in white) and some potential sites that meet these requirements. With the exception of 9 Codman Park, which would entail the renovation of an existing building owned by Children’s Service of Roxbury, all of these sites are owned by the City of Boston and are available for development.

PROGRAM + NATURAL LIGHTING

PROGRAM |

RESIDENT APARTMENTS

RESIDENT APARTMENTS

Single Room (125 x 8)

Single Room (125 x 8)

Resident Advisor Studio

Resident Advisor Studio

Guest Apartment

Guest Apartment

COMMUNITY SPACE

COMMUNITY SPACE

Kitchen / Dining

Kitchen / Dining

Living Room

Living Room

Semi-Private Lounge / Laundry

Semi-Private Lounge / Laundry

Outdoor Space

Outdoor Space

Shared Restrooms (56 x 3)

Shared Restrooms (56 x 3)

Mailboxes + Resources Library

Mailboxes + Resources Library

RESIDENT APARTMENTS

RESIDENT APARTMENTS

Single Room (125 x 24)

Single Room (125 x 24)

Resident Advisor Studio

Resident Advisor Studio

Guest Apartments (100 x 2)

Guest Apartments (100 x 2)

COMMUNITY SPACE

COMMUNITY SPACE

Kitchen / Dining

Kitchen / Dining

Living Room

Living Room

Semi-Private Lounge / Laundry

Semi-Private Lounge / Laundry

Outdoor Space

Outdoor Space

Shared Restrooms (56 x 9)

Shared Restrooms (56 x 9)

Mailboxes + Resources Library

Mailboxes + Resources Library

USE SPACE Commercial / Public Services

/ Public Services

Restrooms (100 x 2)

(100 x 2)

NATURAL LIGHTING |

The program includes private bedrooms, shared spaces, and space for the service provider. Specifics will depend on the needs of the chosen service provider and the size of the building, but two example programs are listed left. Natural lighting is the primary influence on the building’s form and way the program is organized within. Private rooms will need windows for natural ventillation and emergency egress, so should be located on the perimeter of the building. However, shared community spaces should receive the most natural light, and so should be oriented to the south.

SCHEME 2 | Renovation

Sunlight angles help determine the building form, the shade that it will cast at different times of year, the depth of overhangs or shading decvices needed, and window sizes and locations. Allowing winter sun into the building can help keep the space warm in cooler months, while blocking summer sun will help keep the building from overheating. Below is a diagram illustrating the sun angles for our test city of Boston, MA.

Winter Solstice: 24°

Summer Solstice: 72°

Summer Solstice: 72°

Winter Solstice: 24°

SITE ORIENTATION SCHEMES |

These four schemes illustrate how we might arrange the program on the differnt sites in our test city. As some sites are smaller than others, innovative stacked approaches may need to be taken, as shown in scheme 1.

SCHEME 1 | Stacked Amenities

SCHEME 2 | Renovation

26 Forest St

9 Codman Park

ROOF DECK

LAUNDRY

LOUNGE

KITCHEN / DINING

SCHEME 3 | Urban Roof Deck

SCHEME 4 | The Bridge

150 Shawmut

Shawmut

QUALITY OF SPACE |

After site considerations and solar orientation, desired quality of space is the next element that helps determine the building’s form. This collage incorporates images that were collected throughout the semester. These images were used during student workshops, and to help create the catalogue of spaces on the following page.

CATALOGUE OF SPACES |

There are various strategies for achieving a certain quality of space. Ceiling height and pitch, the overall scale of a room, and the number, size, and location of windows all dramatically change how one feels in a space. When we begin to adjust the shape of the room, or divide it into multiple spaces, this affects the quality of space even more. This becomes very complex when we attempt to use these strategies to seperate spaces to various degrees while maintaining a certain quality of space. For example, a room with a lofted space, as shown in diagram #X, still feels like one large room with a smaller intimate space attached. Whereas, a longer loft like that shown in diagram #X creates two seperate spaces with a small visual and acoustical connection between them. This exercise of diagramming and categorizing different types of spaces is endless. Shown here are just a few of the different kinds of spaces that could be incorporated into the housing for youth.

ADJACENCIES |

With space for 12, the kitchen and dining area is the most public area in the house. Living space and outdoor areas are slightly cozier (semi-public), the lounge has seating for no more than 6 and is considered semi-private, and sleeping spaces are private (meant for only one plus an occasional visitor). Adjacencies are determined based on the level of connection needed between each of these spaces. For example, the kitchen and living room spaces should have a high connection, while the kitchen and sleeping spaces should have a low connection. The matrix below led to the creation of an adjacency diagram, which I then translated into an example building section. The next page provides an example of how this adjacency diagram might be translated into the mixed-use community described in the program list found on page 27.

ADJACENCIES |

FORM |

STRUCTURE |

SLEEP

OUTDOOR

SLEEP

LIVING SPACE

KITCHEN / DINING

PRIVATE LOUNGE / LAUNDRY

ADJACENCY SECTION |

This image is not a building proposal. It is a sectional diagram that shows how the typology could apply to a larger mixed-use building. The wall colors correspond to the color-coding of the program and adjacency diagrams on previous pages: the spaces on the top in dark blue are private bedrooms, the middle floors are shared community space, and the ground floor is reserved for the service provider. Here, I included photos of More Than Words Bookstore on the left, and images of a cafe (such as Breaktime Cafe) on the right. The background images illustrate how this typology could be located in an urban area with strict setbacks, as shown on the left, or a neighborhood area with a more sprawling layout, as shown on the right.

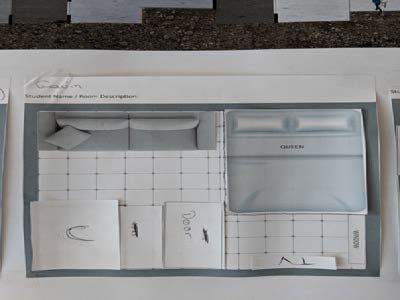

PRIVATE ROOM LAYOUTS |

The ideal bedroom dimensions are 10’ by 11’-6”, with a panel system running the length of the room to allow for varying degrees of seperation if desired. These dimensions perfectly fit bedroom furniture in infinite configurations, and allow the resident to fully customize their own space. One of the youth workshops involved the students choosing inspiration images and designing their own room. A selection of the resulting designs are on the facing page.

Student inspiration images (found on Google images).

STRUCTURE + TECTONICS |

“Creating Order out of Chaos”

“More Supports -> Less Supports”

“Defining a Path”

Journey Into Adulthood”

the

“The

“The Lifelong Journey”

Exploring

concept of ‘jourey’ in model form

A

Journey Through the Building, and Into Adulthood

I am interested in how the design metrics might influence the form and structure of the building. I began with a series of diagrams representing the process that a young person goes through as they transition from childhood to adulthood, and from foster care to independence, but was having trouble settling on one that I felt accurately described the journey. The process led me to the realization that a person’s journey does not end at adulthood. Life will always have ups and downs, highs and lows, and does not simply end when some goal is achieved. Structurally, this building needs to feel solid and stable, with the warmth of a home. To me, the building is screaming to be made of heavy timber. Innovations in the industry allow for walls to become ceilings and floors to become stairs as the young person moves along on their journey through the space. These elements should be visible from the outside- symbolizing the de-stigmatization of homelessness and showcasing the amazing journey that these young people are on.

The diagrams below were generated by tracing the floors and walls in the sectional adjacency drawing from page 37. This exercise could help to generate a structural plan for the building.

Structural and tectonic inspiration images sourced from Google

FORMER FOSTER YOUTH |

In Massachusetts, the top three reasons for home removal are neglect, parental drug abuse, and physical abuse. As illustrated by the overlapping colors in the diagram below, many of these young people have experienced multiple forms of trauma, and for extended periods of time. This is called ‘complex trauma’ and can be very difficult to treat. Being removed from one’s parents is traumatic in itself, and has enormous consequences. A strong parental bond is essential for the development of a young person’s sense of self, sense of safety, and trust of others. Although each young person has a very different background and history, all former foster youth have this trauma in common. Once parental rights are terminated, children are often moved from one placement to another until they are adopted or age out of the system. The average number of placements in Massachussetts is 3.9, and some young people are placed in as many as 47 different homes during their time in the system. As they approach the age of 18, youth are given only 90 days to prepare for discharge from foster care.

variety and choice

In spite of the challenges associated with being in foster care, 70% of foster youth say they want to attend college. Young people, with their energy, creativity, and optimism, have so much to offer this world. Youth tend to have an outlook that is open-minded, non-judgemental, unbiased, and accepting of others’ differences. They have experienced trauma, and will no doubt have more challenging life experiences, but they will also have good experiences, and when given the chance, will make our world a better place. The diagram below illustrates the difference between trauma-informed care and healing-centered engagement. The circle on the left shows a traditional trauma-informed care model, where the yellow star represents the traumatic experience, and efforts are focued inward on healing. The circle on the right shows a healing-centered engagement approach. Although this circle and yellow star are exactly the same size as the one on the left, there is less focus on the trauma amongst all of the other experiences that make a person who they are. Efforts are focused inward on healing, but also outward, on empowering the young person to take charge of their own life. It treats the whole person, rather than just the trauma.

- sense of self - sense of safety - trust of others Time youth are given prepare discharge from foster care:

redistribution of living space

redistribution of living space

gradation

gradation

Young people in foster care who they want to attend college:

PERFORMANCE PROGRAMMING |

Considering procession, movement, and experiential awareness, the Boston Architectural College defines the Performance Programming as a narrative description which illustrates in words the imagined emotional aspects of the outcome of the thesis research. This is my interpretation of what a young person might think and feel as they experience the building for the first time.

Key Features Highlighted:

Close to public transportation, mixed use building, blends with residential neighborhood, accessible, secure, natural light (south-facing), nature, ‘co-living space’ with shared kitchen, shared laundry, shared bathroom with two people (less exposed than sharing with many, but still keeps costs down), shared space encourages community building, able to control things themselves (thermostat, windows open and close, mini-fridge), custom paint color, tray on dresser helps to feel grounded.

This work was created by Angie Ayrault of Ayrault Artware: a line of art that is designed to advance homeless youth by funding school fees, housing deposits, art, music and sports for youth residing in shelter care.

It’s pretty warm out today. I hope my new apartment has air conditioning. I step out of the T station and look around for the c-store where I’m supposed to meet Kathy. There it is. I peek inside, no sign of Kathy. They have eggs and milk. Not too overpriced. Good to know. Kathy arrives and asks if I’m excited. I shrug and smile, then follow her around the corner.

“It’s pretty cool that you got one of these spots. I think you’ll really like it here.” she says.

From the side, the big building kinda looks like a house, but I can tell that several people live here. Inside the door there are mailboxes and an elevator. Kathy turns her key in a lock on the elevator and presses the call button. The doors open, we get inside and she presses 2.

As I exit the elevator on the 2nd floor, I immediately notice the big windows and all the light. Someone left the windows open and it’s pretty warm inside, even with the slight breeze. It’s noisy outside since we’re on a busy street. I see the street below and realize that we’re actually right on top of the c-store where I met Kathy. The room feels big- there’s even a tree in the corner. I feel a bit exposed, even though no one else is home. I turn around to see a couple windows on the wall above us. There’s a set of stairs to get up there.

I see the signs that my roommates have already made themselves at home here. There are dishes drying in a rack next to the sink. Someone’s book is on the table next to the sofa, and a couple pillows are on the floor.

“We call this the lounge.” Kathy says.

It looks like a living room to me, but there’s kitchen stuff along the back wall. There’s a tv in the corner. The couch looks cozy, but I probably won’t spend any time out here anyway, outside of cooking meals. I’m more interested in seeing my own room.

Kathy gestures to the middle door. I turn the knob and walk into the room. Seems small, but pretty standard- full sized bed, dresser, nightstand. There’s a window on the back wall next to the closet. Then I notice the window into the living room space that I just came from. That’s weird, a window to the inside. I really like my privacy, but it’s actually kinda nice because some of that light from the living room makes it way into my room, and I can see what’s going on out there without opening my door. Besides, there are blinds on the window, so I could always keep them closed. For right now, I’ll leave them open. I like the light.

I notice that it’s cold in my room. I see a thermostat on the sidewall and turn it off.

I drop my stuff on the bed and check out the bathroom. Seems clean enough, and there’s a huge cabinet in the wall where I can keep my things. Good thing I’m only sharing with one other person, and she has her own cabinet on the opposite wall. The door to her room is closed. I hope she’s nice. I go back into my room and lock the bathroom door from my side. I look through the window into the living room. I’m really starting to like this window. It lets me keep an eye on what’s going on out there. I notice that it opens, so I open it and let some of the warm air from the lounge into my room. I open the other window on the back wall and can feel the breeze moving through my room. It warms up pretty quickly and it feels pretty comfortable. I open the closet to put my things away and notice that there’s a mini fridge in there. Cool. There’s a tray on my dresser where I put my sunglasses and headphones. I sit on the bed next to my stuff and look at the wall where Kathy is standing. Then I notice that they’ve painted it purple. Is that why they asked my favorite color on the housing application? Kathy looks at me and I accidentally let her see me smile a little. “Do you like it?” she asks.

…Maybe they do care.

WELLNESS + CULTURAL CONTRIBUTION |

The Boston Architectural College defines the Wellness and Cultural Contribution Statement as a description of how the thesis improves the lives of inhabitants, neighborhoods, and communities. It is a discussion in terms of the regional and global conditions; our understanding and responsibility. How does the thesis respond to global and local responsibilities? How does it respond to wellness in the city or neighborhood? How is the work situated culturally? How does it engage other disciplines? What is the relationship of the thesis to professional practice, where practice is understood as a culturally situated activity? The Wellness and Cultural Contribution Statement should identify where health issues or quality of life are inadequate, and state how the work may improve, remediate, or solve for conditions currently not being met.

This iconic Banksy image condemns politics for placing people in situations where they are unable to make a living, and end up homeless on the street. The image can be found reproduced all over the world. The stencil is even available for purchase on Etsy!

Of the 3.5 million young people aged 18-25 who experience homelessness in the course of a year, 50% have stayed in a foster home. 90% of youth in foster care have experienced violence or trauma, with nearly half reporting exposure to 4 or more types of traumatic events. Approximately 23,000 kids age out of U.S. foster care each year, and 40-50% are homeless within 18 months (2,7). Under 3% of these young people earn a college degree, and 50% are unemployed at age 21 (6). The cycle of poverty only exacerbates the problem, elevating the effects of trauma and violence to a community level. It has even been suggested that violence and trauma should be treated as a public health epidemic (5). Experiencing homelessness is traumatic in itself, and being homeless increases the risk of further victimization and retraumatization. Young people are particularly prone to harm because trauma can affect how their brain develops (1), leading to lifelong consequences like poor mental health, poverty, substance abuse, and social isolation. All of these problems will continue to spiral into a cycle of violence until they are finally addressed. Not to mention the fact that a chronically homeless person costs the tax payer an average of $35,578 per year, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Clearly, violence and trauma have devastating effects not just on individuals, but also on entire communities.

Architecture has the power to allow that person or community to sink into a decline, or to help its users heal. The physical environment can produce or mitigate the stress felt after an individual experiences violence or trauma, and I propose the use of design as a tool to build resilience at the individual and community level. In our current socio-political climate of anger, hatred and hostility, it is more important than ever for the design community to make a meaningful impact. More attention should be placed on the creation of healing spaces that build strength and resilience at the individual and community level. We are a community of dreamers, collaborators, planners, and doers with the potential to make tangible strides towards the creation of a more peaceful society, so what can architects do to help?

The healing properties of the built environment have been well documented in healthcare settings, and the same lessons we’ve learned in hospitals can be applied to blighted communities and individuals who have experienced trauma. For example, biophilia is becoming increasingly more popular in the world of design. Natural light, fresh air, and views to nature are all proven to enhance the healing properties of a space (9). But a healing space isn’t just a pleasant space to be in. It must also provide for its occupants psychologically, spiritually, behaviorally, and socially. This thesis responds to health and wellness at every scale- individual, neighborhood, city, nation, and even the world- as the new building typology that emerges from this project is a model that could be implemented throughout the U.S. and in other countries as well. Many other disciplines will be involved in the research and design, including social work, construction, etc. In terms of its relationship to architecture as a profession, this thesis challenges the way we typically approach housing- that is, as an individual experience instead of as an experience of the community. If the practice of architecture is a culturally situated activity, then what better way to approach housing design than while simultaneously addressing a huge, and primarily unknown need here in the U.S.

BUILDING SYSTEMS STATEMENT |

The Boston Architectural College defines the Building Systems Statement as an investigation in writing about the understanding of the building’s structural, environmental, and sustainable design considerations as they relate to proposing solutions to the technical aspects needed for realization. The statement considers methods and materials, sequence of construction, sustainability, availability of resources, cost of construction, digital fabrication, software, and resources, as it identifies the potential challenges and specialized knowledge needed for the construction of the project.

Healing-Centered Design:

There is a lot of information out there around healing-centered design, especially in the healthcare setting. However, my research is showing that healing from trauma is very different from healing from injury or medical conditions. I have identified a specialist in healing-centered design specifically for people who have experienced trauma, and will reach out directly for advice on my design ideas.

Trauma / Youth Case Workers / Youth Experiencing Homelessness:

I will need to work closely with a ‘client consultant’ including youth caseworkers and trauma specialists, as well as a sample group of young people, to provide feedback on the design. Before the project is built, I will ensure that nothing about the design will trigger stress for the young people who will be living in this building.

Non-Profit Development / Funding / Housing Policy:

I will establish contacts with potential funders and with the Department of Neighborhood Development to consult on project funding and subsidies, lowincome housing policy, neighborhood approval, historic preservation, zoning and codes. The project logistics will be one of the most difficult aspects in predevelopment and predesign because of challenges like ‘Not-In-My-Backyard’ (NIMBY) neighbors and a low project budget.

The word mandala comes from the ancient Sanskrit language and translates loosely to “sacred circle”. The circle symbolizes wholeness, continuity, connection, and the cycle of life. Created by interlocking spheres that reflect the geometry of the universe, the colors and patterns of mandalas have a meditative effect, and evoke healing and spiritual development. (Image and background info from holistichealingnews.com).

Contractor:

I would like to work with a contractor starting from early in the design process in order to establish measures for cost savings and construction efficiency, rather than waiting until the design is more established. This will enable me to easily make adjustments that might not affect the design but could save thousands of dollars on the overall project. I believe that Architects and Contractors should communicate more in the design process for this reason. Additionally, a contractor can connect me with specialists in structural, geotech, and other predevelopment issues that may affect the project logistics and budget.

Water Considerations:

The chosen site is subject to Groundwater Conservation as articulated in Article 32 of the zoning code. In order to protect wood pile foundations of buildings from being damaged by lowered groundwater levels, the project must prevent the deterioration of and, where necessary, promote the restoration of, groundwater levels in certain sections of the city. New projects must protect and enhance the city’s historic neighborhoods and structures, and otherwise conserve the value of its land and buildings. They must reduce surface water runoff and water pollution, maintain public safety, and not cause reduction in groundwater levels on the site or on adjacent lots. In addition, the site has a Base Flood Elevation (BFE) of 18ft. The BFE is the computed elevation to which floodwater is anticipated to rise during the base flood, and is the regulatory requirement for the elevation or flood-proofing of structures. I will need to work with specialists in these areas to ensure that the project complies with zoning and is designed in a way that accounts for these very serious water considerations.

Sustainability:

The building should be healthy for its inhabitants and healthy for our planet. Even with a low budget, it is possible to use concepts like passive heating and cooling in order to reduce the embodied energy in the building and provide a more comfortable space for the residents. A sustainability specialist can help me identify other similar strategies to be implemented in the design.

Acoustics / Materials and Technologies / Building Envelope:

I will consult with other specialists as needed. I may need to meet with an acoustics specialist to ensure that each resident has adequate privacy in their room and will not be bothered by sounds that may trigger a post-traumatic stress response. Additionally, I will be soliciting material donations requests and may need to consult with manufacturers or construction specialists on specific building materials or technologies such as heat recovery ventilation, zip wall systems, etc. Especially with the building envelope, I will be selecting building materials with consideration to the history of form in this region, and will most likely be using red brick, glass, and concrete, as is common for this area of Boston. I will be interested in learning how to design sustainably using these materials.

The Gap House

Architect:

Archihood WXY

Location: Seoul, South Korea

There are some basic design principles that are universally known to be good for human health and wellbeing. Natural light and fresh air are two of these elements. Featuring a large central courtyard and recessed outdoor balconies, The Gap House allows for natural light and crossventilation from two sides of every room, and provides ample opportunities for spending time outdoors. The top two diagrams to the right show these features in action. The bottom two diagrams illustrate how the design creates pockets of semiprivate space, and how the shape of the building impacts circulation. The design inspires me to create a building that allows former foster youth to spend time outdoors, and to have access to fresh air and abundant natural light. It is a good precedent for how to incorporate these design features in an urban setting. This particular design, however, would not fit into the Boston context because it doesn’t consider the cold snowy winters. Not to mention, it would look completely out of place among the historic row houses that Boston is known for.

Images found on Google; Photographers unknown.

Share House LT Josai

Architect: Naruse Inokuma

Location: Nagoya, Japan

The Share House demonstrates an innovative way to think about public vs. private. The designer started with an empty box, then placed private rooms within this box. The bedrooms hover at various heights within the large public realm, with stairs and floating hallways bridging between them to provide access. Because the public space is entirely open, it feels full of light. The many openings along the exterior walls allow for ample cross-ventilation, and the elevated bedrooms feel more private because they are removed from the public space. There are opportunities for gathering in various scales- at the shared dining table or living room space on the first level, or on the cozy conversation rug space in the loft. This project is an intriguing take on communal living, but with price per square foot levels in Boston, I’m not sure my design could afford so much open and uninhabitable space.

Images found on Google; Photographers unknown.

Three-Generation House

Architect:

Studio BETA

Location: Amsterdam, Netherlands

The Three-Generation House is a great example of accommodating individual living units within one larger building. In this project, the grandparents live on the top floor, while a young family occupies the next two floors, and the residents all share the bottom two floors- including a large kitchen and living space. The entire back wall of the building is glass, providing ample natural light and a view to the backyard. The front facade is mostly solid for privacy and to blend in with the context. A large central staircase connects all the levels and serves as a semi-public core down through the building. While this design is great for a close family, it would probably not be private enough for unrelated strangers. Also the overall envelope strategy would not be very efficient in Boston’s colder climate. However, the tall narrow shape of the building could work nicely in a narrow Boston residential building lot.

Images found on Google; Photographers unknown.

THESIS PROPOSAL PRESENTATION PANELS |

METHODS OF

1.

“THE

IN-BETWEEN” Transition Space for Former Foster Youth