The Legend of "The Brown Lady"

Any university campus that’s been around for this long—Chowan University was founded in 1848—really ought to have its own myths, and so Chowan does in the legend of “The Brown Lady.” More than a hundred years ago, she was described in the school’s yearbook as the daughter of a wealthy family from the region who honored her parents’ wishes by attending Chowan, putting off marriage to her fiancé, but tragically dying during her sophomore year. A different version of her legend has her jumping to her death from the top floor of the school’s famous Columns Building after her husband (or fiancé) dies during the Civil War. But the main detail that remains the same in every version is her preference for wearing a brown gown made of taffeta, one that would rustle as she walked that has earned her the name of “The Brown Lady.” Legend also consistently figures her as a silent ghost, only recognizable by the rustling of her dress in the hall or on the breeze. But her legend continues to speak at Chowan, now honored through an annual quiz bowl tournament pitting teams from different departments against each other (The Brown Lady Academic Bowl) and the magazine that you’re now reading.

Editorial Board

Timothy Hayes Faculty Editor Associate Professor of English

Olivia Wheeler Elementary Education Honors College Student Association

David Ballew Professor of History

Bo Dame Professor of Biology and Physical Sciences

Danny B. Moore Professor of History

Jennifer Groves Newton Assistant Professor of Graphic Design

Karensa Strieder Graphics Production Graduate Assistant

Destiny Vaughan Disability Services Coordinator

Catherine Vickers Instructor of English

Welcome

Welcome to the 12th edition of The Brown Lady, a creative and academic magazine that showcases some of the most impressive work created by Chowan University students during the past year! I invite you to explore and enjoy the remarkable array of outstanding writing and artistic creations in this issue. We have two important “firsts” to celebrate this year: Destiny Vaughan is now our first student to have work published in 5 different issues, and DyMez Moore is the first ever first-year student to be featured on our cover!

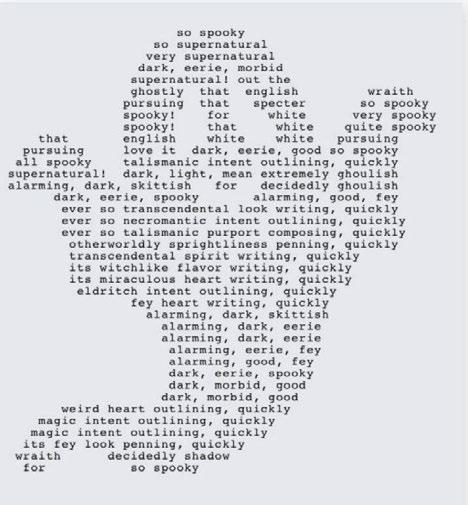

The beginning of this year’s edition features a variety of great work. We begin with a child’s eyes looking out on the world in Destiny Vaughan’s “Sanguine,” which is followed by two impressive “shape” poems, Remus Cox’s lament for a lost pet, “OUR Home,” and Leah Hansley’s clever and energetic “Little White Ghost.” Next comes our cover piece this year, DyMez Moore’s vibrant and striking “Imperfect Stars.” Harry Buckman’s in-depth and intriguing capstone essay “Magic Mushrooms” and Breyonna Lanier’s heartfelt poem “To My Friend” come next.

In the middle section of this year’s issue, we experience a symphony of art and design. This is highlighted by our centerfold, which features a “triptych” of paintings from Destiny Vaughan entitled “Inspired by Esther,” which were created after she experienced the art of Esther Mahlangu, a South African artist, at a Richmond art museum. Following the centerfold, you will encounter Katlyn Gray’s energetic photo “Rock Show” and Destiny Vaughan’s colorful and conflicted “Bamboozled.” The final two pieces in this section take us out into the world, with Skyler Davies capturing an unforgettable sunset in “Horizontal Horizon” and Erica Mock celebrating the historic “skyline” of Porto, Portugal, in her memorable “Pescador.””

Next comes a number of accomplished written works. Tasia Huntley and Jordan Goodfellow each share poems that recall troubled times. Huntley’s “Jim Crow Sonnet” looks back to a time of prejudice and forward to greater freedom, while Goodfellow honors a family member who fled persecution after World War II. Destiny Vaughan is back with her poetic speech, “Answering With Hope,” followed by Jasmine Hendricks’s sensitive and thoughtful poem, “She Waited…” Katlyn Gray’s insightful “Are Psychopathy Assessments Ethical and Do They Accurately Predict Violence?” comes next. Then, Jasmine Hendricks returns with two more poems, one lamenting a lost companion (“Space”) and one fervently calling for their return (“Where You Belong, To Me”). Kaleena Green’s quiet and thoughtful poem “Root to My Tree” closes out this section. Then art gets the final word, so to speak, in this year’s issue. Three design pieces from Destiny Vaughan’s senior project—“Hopefully Disguised,” “Immerse in the Void,” and “Invisible Forces”—capture the struggle for identity and belonging. Skyler Davies closes out this year’s issue on a lighter note with a quintessential image of college sports, “Through the Grit and Grime.”

On behalf of this year’s editorial board, I encourage you to spend some time with each of these outstanding works in the weeks, months, and years to come. I hope you are as proud of these extraordinary students as we are. Enjoy…and, as always, be sure to congratulate this year’s contributors!

Dr. Tim Hayes Faculty Editor

Magic Mushrooms

The Neurophysiological and Pharmacological Effects and Plausible Applications of Psilocybin for Neuropharmaceuticals and Psychotherapy

Harry BuckmanAbstract

This study aims to create a comprehensive understanding of the neurophysiological and pharmacological effects of psilocybin and to further advance the research pertaining to the comparative efficacy of the drug compared to traditional antidepressant medication interventions. This study encompasses a range of varying dimensions, including the plausible beneficial therapeutic effects and applications of psilocybin as it relates to neurophysiology, neuroplasticity, and individual psychological states. Specifically, the research explains how the benefits in these categories correlate to improvements in the maladapted neurophysiology of individuals suffering from major depressive disorder and how the therapeutic potential of psilocybin can elucidate reductions in depressive symptomology experienced by such individuals. The proposed hypothesis sets the stage for a multi-pronged approach that explores the comparative neuropharmaceutical efficacy of psilocybin and traditional antidepressants. The study’s design ensures a rigorous comparison between the psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions and traditional antidepressants, considering safety, feasibility, and long-term neurophysiological, psychological, and neuroplastic changes.

The study also briefly explores the current economic, legal, and social landscapes relating to psilocybin use, both in the clinical setting and in the research setting across multiple countries, providing context to the broader implications and challenges associated with its applications. Overall, the study aims to contribute significantly to the multifaceted understanding of the biochemistry, pharmacology, and mechanisms of action

of psilocybin, positioning the drug as having antidepressant, anxiolytic, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties. The study explores the comparative efficacy of psilocybin compared to traditional antidepressants and expands upon its potential role in the future of neurotherapeutics that will shape new paradigms of mental health interventions.

Key Words: PSILOCYBIN, SEROTONIN, 5-HYDROXYTRYPTAMINE, PSYCHOPLASTOGEN, NEUROPHYSIOLOGY, NEUROPLASTICITY, NEUROPHARMACEUTICAL INVERVENTION, MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Introduction

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring psychoactive compound found in the Psilocybe mushroom species. It has a rich history of use in various indigenous cultures, such as Mayan, Olmec and Aztec (MacCallum et al., 2022), for its profound and mind-altering changes on perception, cognition, and mood. When ingested, psilocybin is converted into its pharmacologically active metabolite, psilocin, which produces these mind-altering changes through the non-specific partial agonism of 5-hydroxytryptamine serotonergic receptors (Kwan et al., 2022; MacCallum et al., 2022). This intricate mechanism of action has been the subject of extensive research, offering valuable insights into how psilocybin’s pharmacological characteristics modulate the neurobiological underpinnings of cognition and human consciousness (de Vos et al., 2021; Hasler et al., 2004).

For those who may have lived through the mid-1960s to mid-1970s, namely the “Psychedelic Era,” such psychoactive compounds have noted benefits that extend beyond recreational use.

Currently at the forefront of medical research is psilocybin, which is the most studied psychoactive substance. Emerging evidence confirms psilocybin’s significant medicinal, pharmacological, and neuropharmaceutical applications and potentials in the realm of psychotherapy (Goel et al., 2022). Psilocybin shows great promise in addressing a range of conditions, including the treatment of pain and inflammation, migraines, and alleviation of mood disorders, such as anxiety and major depressive disorder (MDD) (Lowe et al., 2022; Schindler et al., 2021). These findings have sparked excitement in the medical and neuroscientific communities, as psilocybin-based treatments, and proof of their enduring remedial impacts, may address a new critical field of neuropharmaceutical-based treatments that may potentially provide relief to individuals suffering from, and experiencing an assortment of, physical and psychological disorders (Goel et al., 2022). Herein, this work explores the plausible applications and feasibility of psilocybin for its uses in the neuropharmaceutical, psychotherapy-assisted treatment of mental health disorders, specifically major depressive disorder (MDD). This work also secondarily proposes psilocybin as an analgesic, with potential plausible effects on a broader range of somatic health conditions.

Literature Review

Biochemistry & Pharmacology

Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,Ndimethyltryptamine) and its pharmacologically active metabolite, psilocin (4-hydroxy-N,Ndimethyltryptamine), are the major psychoactive alkaloids in several hallucinogenic mushrooms of the Psilocybe mushroom species (Hasler et al., 2004). They are tryptamine/indolealkylamine (where indolealkylamine is a subgroup of indolylalkylamines that have pharmacological or psychoactive properties), serotonergic hallucinogens that are structurally similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin (EMCDDA, 2013; Lowe et al., 2022; MacCallum et al., 2022). Both psilocybin and psilocin are moderately minuscule, with tryptamine-enlivened structures, that are derived from a common pharmacorphore structure that consists of an indole ring that is connected to an

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

aminoalkyl chain via a two-carbon linker (Goel et al., 2022; Kwan et al., 2022). Specifically, the indole ring at the fourth position of the tryptamine structure of psilocybin and psilocin is responsible for the hallucinogenic effects associated with the drug. Functionally, the two-carbon linker creates optimal spacing between the two groups of the pharamacophore, for the non-specific partial agonism of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) serotonergic receptors (MacCallum et al., 2022).

Psilocybin exists as a dihydrogen phosphate prodrug that undergoes dephosphorylation in vivo upon administration and ingestion within the acidic environments of the stomach, kidneys, and blood. This transformation is facilitated through the action of alkaline phosphatases and esterases and results in the conversion of psilocybin into its pharmacologically active form, psilocin (Goel et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2021). Psilocin is believed to be the dynamic fixing and principal active compound in the focal sensory and central nervous systems, which exhibits varying affinities for a range of serotonin receptors, including 5-HT1A , 5-HTB, 5-HTD, 5-HTE, 5-HT2B, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7, with a particularly high affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor (de Vos et al., 2021).

Though serotonin is the natural ligand for the 5-HT receptor family, these receptors can also be manipulated by other compounds (Berger et al., 2022). Normally, serotonin is released into the synaptic cleft via adjacent nerve impulses, where successive specific binding to postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors ensues (Bakshi et al., 2022). Central nervous system serotonin receptor binding interactions are said to regulate neurophysiological, neuropsychological, and behavioural processes (Bakshi et al., 2022; Kulkarni et al., 2022). When serotonin binds to postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors, normal functioning and downstream effects occur. Thus, the dysregulation of serotonergic functions is linked to altered psychiatric and neurologic conditions. The binding of psilocin to the 5-HT2A receptor results in non-specific partial agonistic activity within the serotonergic neurotransmitter system, where psilocin partially activates the receptors, leading to altered signalling within the brain (MacCallum et al., 2022).

This altered signalling establishes wide-

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

ranging effects on the serotonergic, dopaminergic, and glutamatergic systems, neural circuitry, and neuroplasticity, which are attributed to the psychedelic and visual hallucinatory effects associated with psilocin (Kwan et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2021; MacCallum et al., 2022). 5-HT2A receptors are also greatly expressed in the visual cortex and visual cortical neurons of the occipital lobe. Agonism of these receptors within the visual cortex greatly contributes to the propensity for visual hallucinations associated with psilocin (Ling et al., 2021; MacCallum et al., 2022). On a larger scale, the 5-HT2A receptors play a pivotal role in mediating emotions and moods, including anxiety and aggression, as well as influencing cognition, sexual behaviour, learning and memory processes, and appetite regulation, along with various other biological, neurological, and neuropsychiatric processes (Lowe et al., 2022).

Neurophysiology and Neuroplasticity

Current neuropharmacological and psychopharmacological studies strongly suggest the beneficial therapeutic potential of psilocybin, where biological adaptations caused by psilocin lead to lasting behavioural and cognitive changes in individuals (de Vos et al., 2021). The continuing effects of psilocybin categorise it as a “psychoplastogen” (Olsen et al., 2018), as the pharmacologically active metabolite rapidly stimulates periods of accelerated neuronal growth. This process enhances shortterm neuroplasticity, while catalysing enduring neuroplastic changes (Calder et al., 2022; de Vos et al., 2021). Neuroplasticity denotes the capacity of the central and peripheral nervous systems to reorganise its structure and function to adapt to a dynamic environment. Throughout the lifespan, neuroplasticity is essential for learning, memory formation and retention, and recovery from neurological injury, as well as adapting to life experiences (Ismail et al., 2017). In the clinical context, psilocybin-based interventions and psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy have reportedly engendered pronounced acute and enduring improvements in the mental health of individuals suffering from maladaptive behavioural responses such as major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety

(Calder et al., 2022; Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2018). These therapeutic outcomes are posited to be linked to the mitigation of neuroplasticity aberrations prevalent in the aforementioned psychiatric conditions (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Griffiths et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016).

Neuroplasticity encompasses structural plasticity, involving changes in cell structure, and functional plasticity, which pertains to alterations in the efficacy of synaptic transmission (Calder et al., 2022; de Vos et al., 2021). At the molecular and cellular levels, psilocybin initiates neuroplastic changes via signalling pathways, comprising changes in gene and protein expression as well as post-translational modifications (Calder et al., 2022). Psychoplastogen-stimulated structural and functional neuroplastic changes at the cellular level, regulated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (a neurotrophin that regulates neuronal growth and synaptic plasticity) (Gulyaeva et al., 2017), can be measured through morphological changes and increases in neurogenesis (most notably in the hippocampus), dendritic spine density, synapse number, immediate early gene (IEG) expression, neuroplasticity-related gene expression, and intrinsic excitability within a short period of time, usually 2-24 hours, following administration of psilocybin interventions (Calder et al., 2022; de Vos et al., 2021; MacCallum et al.1, 2022; Olsen et al., 2018).

Neuroplastic changes may occur while the acute effects of the drug are experienced, although the peak and persisting effects are mostly observed at later times. These psychoplastogen-stimulated changes at the molecular and cellular levels enable the reshaping of neural circuits (Calder et al., 2022), resulting in behavioural and cognitive improvements that yield long-lasting alterations in neurochemistry and, consequently, behaviour, extending beyond the acute effects of the drug (de Vos et al., 2021; Olsen et al., 2018). Notably, increases in the upregulation of IEG’s and other neuroplasticity-related genes, elevated peripheral BDNF protein concentration in the prefrontal cortex, and enhanced neurogenesis, including greater synaptic density, and increased dendrites and dendritic spines, have been documented at 2 days, 30 days, and 60 days post-administration, respectively (Calder et al., 2022).

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

Economic Disease Burden

According to a 2019 global burden of disease (GBD) study, mental and behavioural disorders (MDD, OCD, PTSD, addiction, and anxiety) rank among the top ten leading causes of global disease burden (Ferri et al., 2022). In the realm of clinical research, recent investigations have been primarily directed towards elucidating the neurophysiological and pharmacological effects of psilocybin and their potential therapeutic implications in addressing maladaptive behavioural disorders, notably MDD, OCD, as well as substance addiction to tobacco and alcohol and anxiety-related conditions (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Ling et al., 2021). Notably, MDD stands as a considerable public health burden, in terms of number of individuals impacted and in terms of both its negative economic externalities and raw financial costs (Davis et al., 2021). In 2023, an estimated 21.0 million adults (aged 18 or older) and 6.0 million adolescents (aged 12-17) were diagnosed with MDD in the USA, and the incremental socioeconomic burden of the disorder is estimated to exceed 382.4 billion US dollars (USD) within the nation (Greenberg et al., 2023; NIMH, 2023). Globally, the negative externality related to MDD is estimated to cost the global economy 1 trillion USD in 2023 and is forecasted to reach 16 trillion USD by 2030 (Chodavadia et al., 2023).

Disorders

Conventional first-line antidepressants, such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), and serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), exhibit a notable therapeutic delay of up to two weeks and demonstrate limitations with regard to their efficacy and patient adherence (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Davis et al., 2021; Ling et al., 2021). Recent empirical investigations have provided compelling evidence suggesting that the administration of psilocybin, in conjunction with psychological integration therapy, yields significant, enduring enhancements in the well-being and mental states of individuals. These beneficial effects are attributed to the “pharmaco-physiological interaction” between psilocybin, neural chemistry, and neuroplasticity, ultimately culminating in its antidepressant and anxiolytic properties (Carhart-Harris et al.,

2017; Davis et al., 2021; Ling et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2016). Recent empirical investigations involving a psychotherapist-led administration method is evidenced to limit many regimen compliance issues otherwise associated with prescribed conventional treatments, as treatments occur in the presence of a practicing psychotherapist (CarhartHarris et al., 2017).

In relation to neurophysiology and neuroplasticity, MDD is characterised by specific neurobiological changes. These include reduced cortical neuroplasticity, synapse atrophy in the prefrontal cortex, and a reduced ability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate limbic areas (Calder et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2021). These limbic areas, which include the amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and cingulate cortex, regulate emotional information processing and response and memory processing while also influencing decision-making processes (Calder et al., 2022). Additionally, social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety are associated with fewer synaptic connections between the medial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, which compromises the prefrontal cortex’s ability to regulate fear responses (Calder et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2021).

Administration of psilocybin to brain regions expressing 5-HT2A receptors is associated with increased expression of the early growth genes egr1 and egr-2 (Ling et al., 2021). Alterations in the gene expression of the aforementioned genes is unique to 5-HT2A hallucinogens. Alterations in expression of these early growth genes are conducive in dendritic and synaptic growth and enhancement and heightened neurogenesis within limbic brain regions. These findings suggest that psilocybin activates critical neuroplastic pathways that underlie its putative antidepressant effects (Calder et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2021).

Both MDD and anxiety disorders are associated with an overexpression of 5-HT2A receptors in the prefrontal cortex and limbic brain regions, where overexpression correlates positively to the severity and duration of depressive symptomology (Ling et al., 2021). Administration of psilocybin leads to the modulation of BDNF, which results in downstream downregulation of 5-HT2A receptors. This deregulation is directly associated with the

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

putative antidepressant and anxiolytic properties of psilocybin, indicating that the modulation and deregulation of 5-HT2A receptors serves as a predominant mechanism underlying its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects (Calder et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2021).

Therapeutic Potential in Mental and Behavioural Disorders

Research into acute brain action of psychedelics, specifically psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical interventions, has consistently revealed well-replicated alterations in global brain function and connectivity (Daws et al., 2021). Notably, individuals with depression exhibit an abnormally constricted functional connectivity state space, reflecting limited and/or constrained and restricted connectivity patterns between different brain regions (Carhart-Harris, et. al., 2017; Daws et al., 2021). This constriction in functional connectivity mirrors the characteristic narrow, introspective, and ruminative cognition and emotional state observed in individuals with depression. The constriction of the functional connectivity state space directly correlates to abnormal modular spontaneous brain function and the altered cognitive and emotional processes that are hallmark features of depression (Daws et al., 2021). Current research shows that psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical treatments and interventions effectively remediate the functional connectivity state space constriction and the abnormal modular spontaneous brain function that is associated with depression (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Daws et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2016). Psilocybin seems to enhance the brain’s capacity to visit a broader state space, both in acute experiences and following psilocybin therapy in individual patients with depression (Daws et al., 2021). The “liberating” action of psilocybin aligns with subjective reports of emotional release, immediate and sustained increases in quality of life, spirituality, behavioural optimism, cognitive and psychological flexibility, and significant reductions in existential distress (Daws et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2016).

Purpose

In the current context, there is a growing interest in developing alternative neuropharmaceutical approaches for the treatment of mental health. The purpose of this study is to comprehensively investigate the comparative treatment efficacy of psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions and traditional antidepressants in individuals diagnosed with MDD in particular. By employing a range of standardised depression-rating assessments, physiological monitoring, and neuroradiological techniques, the research seeks to elucidate not only the immediate therapeutic effects but also the sustained neuroplastic changes associated with psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions. The research also aims to shed light on the safety, tolerability, and overall feasibility of integrating psilocybin into clinical interventions for MDD, contributing to the ongoing discourse on the potential benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapies. The outcomes of this study may inform future treatment paradigms, guide regulatory considerations, and ultimately contribute to the evolving landscape of mental health interventions.

Hypothesis

It is hypothesized that individuals diagnosed with MDD who undergo psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions will demonstrate significantly greater improvements in both physiological and psychological parameters compared to individuals receiving traditional antidepressant treatment interventions. The positive enhancements are expected to manifest in various aspects, including a more substantial reduction in scores on the GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID-HAMD), indicating a greater alleviation in depressive symptomology. Additionally, individuals in the psilocybin-based intervention group are anticipated to exhibit far more favourable changes in the measured cardiovascular statistics, blood chemistry, hormonal balance, and neurophysiological markers as evidenced by fMRI and PET scans. The hypothesis posits that the unique neuroplastic and neurophysiological effects of psilocybin will lead to a more comprehensive and sustained improvement in the mental health and overall well-being of individuals with MDD when compared to conventional antidepressant treatments.

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

Methods

Characteristics of participants:

In this clinical research study, male and female subjects aged between 25 and 75 years with a clinical diagnosis of MDD and a depression severity of ≥ 17 on the GRID-HAMD will be enrolled. 100 enrolled participants would be optimal for this study; however, accounting for potential exclusions and participant dropouts, a sample size of 40 participants who reach completion of the experiment would be deemed adequate.

To ensure the safety and validity of the study, the following criteria will be applied. Participants with a personal or familial history of psychotic disorders will be excluded to minimize the potential risks associated with psychedelic interventions. Individuals with a history of serious suicide attempt(s) or prior hospitalisation due to their MDD will also be excluded, as their participation may require specialised and more intensive care beyond the scope of this study. Participants who are currently prescribed or using traditional antidepressant or anxiolytic medications, including SSRIs, NRIs, SNRIs, and gabapentin, will not be eligible for participation. This exclusion aims to minimize any potential interactions or confounding effects between traditional medications and the psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions. To ensure psychological stability and suitability for participation, individuals must undergo a mental state and personality stability evaluation, administered by a practicing clinical psychologist. This evaluation is crucial, as, following the dosing of psilocybin, individuals with unstable personalities and mental states may experience transient anxiety due to the loosening of ego-boundaries that occurs during dosing of psilocybin.

Participants who are using other medications, for non-psychiatric medical conditions, may be considered for participation, provided they have been on stable doses for a specified duration before entering the study.

Participants who meet all of the previous criteria will be subject to a baseline health assessment to confirm their physical health, including the absence of severe cardiovascular

and gastric conditions. If the presence of a serious condition in either of these two categories is present, the participant will be excluded. This is important, as psilocybin may acutely increase heart rate and blood pressure following administration, and the potential nausea associated with psilocybin administration may exacerbate severe gastric conditions. Additionally, a comprehensive review of their medical history shall be conducted to identify any other potential contradictions or interactions with psilocybin. If any potential contradictions are present, the participant will be excluded.

Variables and measurements:

In this clinical research study, the primary experimental variable to be tested is the type of intervention administered, where the therapeutic effects of psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical interventions will be compared to those of traditional antidepressants, specifically escitalopram. To establish a rigorous comparison, an included experimental control group will receive a placebo.

The variable to be measured will be changes in the GRID-HAMD score over time, which serves as a quantitative indicator of depression severity. Physiological variables relating to cardiovascular statistics, blood chemistry, and hormonal balance will be monitored to track the immediate physiological responses to the interventions and establish the effect of psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions on somatic health.

Neurophysiological changes associated with neurogenesis in specific brain regions and expression of 5-HT2A receptors, including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and limbic areas, will be examined and tracked over a 3-month period of time. These assessments conducted over set timeframes will be used to establish the efficacy of psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical interventions in increasing cortical neuroplasticity, synapse hypertrophy, and moderating 5-HT2A receptor expression (where reduced cortical neuroplasticity, synapse atrophy, and 5-HT2A receptor overexpression are specific neurobiological adaptations of those suffering from MDD).

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

Additionally, the therapeutic delay associated with psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical interventions will be investigated and compared to the therapeutic delay of traditional antidepressants and placebos. This analysis aims to determine the time it takes for each treatment to yield significant improvements in depressive symptomology. By examining these variables across psilocybinbased treatments, traditional antidepressants, and placebo groups, a comprehensive understanding of the comparative efficacy and mechanisms of action for individuals suffering from MDD will be developed.

In this clinical study, it is also important to recognise the extraneous variables that could impact the validity of the study. Individual variability in response to psilocybin, influenced by factors such as psychological history, personality traits, and genetic predispositions, may introduce unpredictability in treatment effects. Although unlikely due to the small, fixed dosage, it is possible for participants to experience acute transient anxiety due to the loosening of ego-boundaries that occurs during psilocybin administration. Expectation effects may also occur, where participants’ beliefs about the efficacy of psilocybin or traditional antidepressants may place placebo effects on or alter perceived treatment outcomes. The blinding of the patients to the treatment they are administered should limit this from occurring; however, it is a possibility that should be considered. The rigorous monitoring and standardised procedures presented in this study should assist in mitigating the potential for confounding or extraneous variables to impact the internal validity of the study.

Instruments:

GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID-HAMD) – this standardised assessment will be used to quantitatively measure the severity of participants’ depressive symptomology. The GRID-HAMD test will measure 17 differing aspects of emotional, behavioural, psychosocial, and physical symptoms that are associated with MDD.

Philips PageWriter TC10 Electrocardiogram Machine – this state-of-the-art, hospital grade electrocardiograph (EKG) machine will examine

and measure the following standard parameters: mean, minimum, and maximum heart rates (min1), number of supraventricular and ventricular extrasystoles (n), maximum S-T elevation (mm and °), maximum S-T depression (mm and °) and number of pauses (asystoles; n).

Phillips IntelliVue X3 – this compact continuous patient monitoring system will examine blood pressure continuously, recording measurements at regular intervals. This non-invasive device will express blood pressure data in the following standard parameters: mean, minimum, and maximum systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean arterial pressure (MAP) (mmHg), and maximum rise of MAP above placebo level (∆ MAX MAP).

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imagine Machine (fMRI) – this specialised application of MRI will capture images continuously over a period of time to allow observation of dynamic brain activity during periods of intervention administration. fMRI operating at a field strength of 1.5 Tesla or higher will provide time-series images of individual brain structures specific to this study (hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and limbic areas) and display changes in brain morphology associated with neurogenesis, cortical neuroplasticity, and synapse remodelling over a period of time.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Radiolabelled Ligands – this medical imaging technique will be used to visualise and quantify in vivo expression of 5-HT2A receptors in the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions of the brain. PET will work in conjunction with radioactively labelled isotopes carbon-11 (11C) and fluorine-18 (18F) that are designed to bind specifically to 5-HT2A receptors. PET will construct a three-dimensional image of the brain showing where radiolabelled ligands have accumulated and where intensity of signal shows receptor concentration.

Beckham Coulter AU480 Chemistry

Analyser – Blood samples for quantification of hormones and clinical chemical parameters will be drawn from participants via intravenous catheter. With the use of centrifugation and this device, blood chemistry of participants will be monitored at varying time intervals throughout

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

the experiment. The AU480 Chemical Analyser will be used to measure the following standard parameters: blood concentration levels of serotonin, cortisol, dopamine, testosterone, oestrogen, and norepinephrine, and blood concentration levels of free radicals, proinflammatory cytokines, and blood oxidative stress. Standard blood chemistry, including levels of sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), chloride (Cl-), nitrogen (N+), urea (UR), and creatinine (CR), will also be recorded and analysed for data analysis.

Procedure:

Subjects will participate in the study over the course of 3 months, with two dosing sessions occurring in the first month. The first dosing session will occur on day one of experimentation, and the second dosing session will occur 2 weeks later. Participants will be blinded to the intervention that they are administered. Prior to both administrations of neuropharmaceutical interventions, participants will undergo a baseline GRID-HAMD test that will be conducted by a blinded practicing clinical psychologist via telephone call, have fMRI baseline recorded, and PET in conjunction with radiolabelled ligands (carbon-11 and fluorine-18) will be used to determine baseline 5-HT2A receptor expression in the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions of the brain. Drug intake will be accompanied with 3 months of weekly assisted psychotherapy to maximise potential benefits.

One hour prior to both dosing sessions, participants will begin EKG and cardiovascular statistics monitoring. EKG and cardiovascular statistics monitoring will occur continuously for 24 hours following administration of the neuropharmaceutical intervention. Blood will be drawn via intravenous catheter into vacutainer tubes an hour before drug intake, and at 5, 30, 60, 120, 180, and 240 minutes post drug intake. Following blood sampling, plasma will be separated via centrifugation and immediately stored at -27° C until analysis. These results will be compiled for data analysis, where said results will be used to track the immediate physiological responses to the interventions and establish the effect of psilocybinbased neurotherapeutic interventions on somatic health.

Following this hour of baseline assessment, psilocybin, traditional antidepressant intervention, or a placebo will be administered in an opaque gelatin capsule with approximately 100 mL water. Psilocybin capsules will contain a standard fixed dose of 25 mg (which is consistent with current clinical trial protocols and the previous 0.3 mg/kg weight-based dosing protocols), the traditional antidepressant intervention (specifically escitalopram) will contain a fixed dose of 10 mg, and the placebo will contain water and 25 mg of glucose sugar. Facilitators will be present in the room and available to respond to participants’ physical and emotional needs during the 24-hour period. Participants will be instructed to lie on a couch in a living room-like environment, to focus their attention inward with their eyes closed, and to stay with any experiences that arise.

fMRI and PET scans will occur at 2, 6, 12, and 24 hours following both the first and second drug administrations. These scans will also be repeated at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 weeks after initial drug intake. These scans will be compiled and compared in future data analysis, where changes in brain morphology and neurogenesis will be tracked over time and compared to other neuropharmaceutical interventions, to determine the effectiveness of psilocybin in correcting the maladaptive neurobiological adaptations of individuals suffering from MDD.

Following administration of the neuropharmaceutical interventions, participants will undergo a GRID-HAMD test, conducted every other week for 3 months by a blinded practicing clinical psychologist via telephone call. These scores will be compiled for future data analysis, where test scores will be tracked over time and compared to other neuropharmaceutical interventions to determine the efficacy of psilocybin and assisted psychotherapy in reducing the depressive symptomology of individuals suffering from MDD.

Discussion

The experimental choices made in this study were driven by a meticulous consideration of existing gaps in the current research literature and a commitment to addressing them

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

comprehensively. Notably, the decision to aim for an optimal sample size of 100 participants while having an adequacy goal of 40 participants was motivated by a desire to overcome a limitation observed in similar studies conducted by CarhartHarris (2017), Davis (2021), and Hasler (2004), which had small sample sizes of 20, 27, and 8 participants, respectively (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Davis et al., 2021; Hasler et al., 2004). By increasing the potential sample size by 5.0, 3.70, and 12.5 times respectively, the study aims to enhance the reliability and generalisability of its findings. By representing a larger proportion of the population, more robust insights into the comparative efficacy of psilocybin and traditional antidepressants can be elucidated.

The selection of escitalopram as the traditional antidepressant is grounded in its status as one of the most commonly prescribed antidepressants in the United States. This choice ensures that the study’s findings will be applicable to a broad population and align with real-world clinical practices. By opting for a widely prescribed SSRI antidepressant, the study addresses a practical aspect of treatment comparison, contributing to the relevance of its outcomes in the broader context of mental health neuropharmaceutical interventions.

In terms of the neuroimaging choices, the focus on specific brain regions, including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and limbic areas, was informed by the high expression of 5-HT2A receptors in these regions (de Vos et al., 2021; Ling et al., 2021; MacCallum et al., 2022). This strategic selection aligns with the aim of understanding the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of psilocybin. By focusing on areas with heightened receptor expression, the study aims to unravel the interplay between psilocybin, neural pathways, and receptor modulation, which contributes to the developing comprehension of its therapeutic actions.

The incorporation of a placebo control group and rigorous and continual monitoring of physiological parameters including cardiovascular statistics, blood chemistry, and hormone balance, adds a layer of scientific methodological robustness. The inclusion of a placebo group ensures that the observed effects

can be confidently attributed to the interventions, minimising the confounding and extraneous variables and enhancing the internal validity of the study.

While this study is designed with a multipronged approach to make significant contributions to our understanding of the comparative efficacy of psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions and traditional antidepressants, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations. The exclusion of individuals with a personal or familial history of psychotic disorders, as well as those with a history of serious suicide attempt(s) or prior hospitalisation due to MDD, may limit the generalisability of the findings to a broader population. Additionally, the exclusion of participants currently prescribed or using traditional antidepressant or anxiolytic medications may affect the applicability of the results to individuals already undergoing conventional treatments. The study’s focus on specific brain regions, while strategic for understanding 5-HT2A receptor modulation, may also limit the generalisability of the findings to other brain areas associated with depressive symptomology. The 3-month duration of the study may provide insights into the short- to medium-term effects of psilocybin on neurophysiology, neuroplasticity, and depressive symptomology but may not capture the long-term sustainability of the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin. Recognising these limitations is essential for interpreting the results in a nuanced manner and underscores the need for future research to address these constraints and further refine the understanding of psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic therapies in diverse clinical contexts.

Currently on the global stage, there is great interest in utilising psilocybin as an alternative to traditional antidepressant, anxiolytic, and antiinsomnia/hypnotic medications, as ongoing and future research continues to prove the efficacy of psilocybin in remediating mental health and physiological disorders (Carhart-Harris & Godwin, 2017; Lowe et al., 2022). The aforementioned pharmaceutical interventions, specifically serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and gabapentin (the most common anxiolytic medication), produce severe side effects, such as increased risk of suicide,

sexual issues, increased susceptibility to internal bleeding, and others (Lowe et al., 2022). Additionally, in the USA, these drugs are heavily overprescribed (Smith, 2012). Conversely, psilocybin exhibits several advantages, including low physiological toxicity, safe physiological responses, minimal potential for addiction or dependence, a low likelihood of developing neurological deficits after use, and a lack of persisting adverse physiological or psychological effects during or after use (Lowe et al., 2022). Psilocybin is associated only with relatively minor side effects in comparison to commonly prescribed antidepressant, anxiolytic, and antiinsomnia/hypnotic medications and interventions (Lowe et al., 2022).

The utilisation of psilocybin in neuropharmaceutical medications is currently marred by certain drawbacks and negative perceptions. Psilocybin remains associated with a high abuse potential in recreational contexts (Lowe et al., 2022). Those with a family history of psychotic disorders (such as schizophrenia disorder and paranoid personality disorder) need to be excluded from using psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical medications and being involved in psilocybinassisted psychotherapy due to safety concerns and a reduced efficacy of psilocybin to act in a beneficial physiological and psychological manner on the aforementioned individuals (Lowe et al., 2022). Finally, there is still a negative social construction and perception as it pertains to psilocybin. The negative stigma associated with psilocybin poses a significant hurdle for both academic researchers and governmental policymakers alike; it also represents a hurdle to both the prescriber and the consumer of these substances and impedes their broader acceptance (Lowe et al., 2022). Further research is required, as, from the physiological and pharmacological standpoints, the mechanisms of action of psilocybin still require more comprehensive elucidation (Lowe et al., 2022).

As of July 1, 2023, Australia became the first country in the world to legalise the therapeutic use of psilocybin to treat severe mental health conditions (Hunt, 2023; Wertheimer, 2023).

Authorised psychiatrists are now able to prescribe psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical interventions in conjunction with psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of individuals

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

with treatment-resistant depression (Hunt, 2023; Wertheimer, 2023). The laws and regulations regarding this breakthrough medication are strict; before Australian psychiatrists are permitted to prescribe psilocybin-based neuropharmaceutical and psychotherapy interventions, they must obtain approval from a human research ethics committee and formal approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (Ducharme, 2023; Hunt, 2023).

While Australia leads the way in legalisation and regulation of psilocybin as a medication and neuropharmaceutical, clinical human trials are also underway in the United States, Canada, and Israel. The current legalisation, regulation, and trials underway globally are “ushering in a new era of psychedelic medicine” (Wertheimer, 2023). In the United States, the FDA has recognised psilocybin as and granted the drug the title of “breakthrough therapy,” and Australia’ s approval of psilocybin for the treatment of mental health conditions is expected to expedite the approval process in the United States, with approval “anticipated within approximately 24 months” (Ducharme, 2023).

Beyond the benefits that psilocybin engenders for mental and behavioural disorders, the drug also has potential plausible effects on a broader range of somatic health conditions. Recent exploratory research has provided evidence that psilocybin, along with other 5-HT2A receptor agonists (specifically lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and dimethyltryptamine (DMT) can induce long-lasting therapeutic effects in the treatment of somatic health conditions that are characterised by chronic inflammation (Schindler et al., 2020). Evidence from these exploratory investigations has revealed that the pharmaco-physiological interaction between psilocybin and 5-HT2A receptors leads to immunomodulatory, antiinflammatory, and analgesic effects (Schindler et al., 2020). Specifically, evidence shows psilocybin to be effective in treating migraine headache disorder, which is characterised by chronic inflammation. Migraine headache disorder is the most common of all headache disorders and has a prevalence of 15% that ranks it among the top three in disabling diseases on a global scale (Ling et al., 2021; Lipton et al., 2001). The immunomodulatory, antiinflammatory, and analgesic effects of psilocybin also extend to delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), intractable phantom-limb pain (PLP), and

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

chronic pain disorders (Lowe et al., 2021).

Recommendations for Future Research

Future research in this field should consider expanding the sample size of the tested participants to enhance the statistical reliability and generalisability of findings. A larger and more diverse participant pool would allow for subgroup analyses and the consideration of individual difference(s) that might influence treatment outcomes (such as age, ethnicity, previous exposure to psilocybin, etc.).

Additionally, investigating the economic viability of psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions is crucial, as the current regulatory landscape and production costs can significantly impact accessibility and affordability. Stringent regulations such as compliance requirements, infrastructure construction regulations, and quality control measures limit the ability to produce pharmaceutical-grade psilocybin at an economy of scale. The currently limited scalability leads to higher per-unit production costs, making psilocybin-based neurotherapeutic interventions more expensive for the consumer.

Future research focusing specifically on the effects of psilocybin on MDD should consider developing the knowledge regarding the comparative efficacy of other psychoactive substances such as LSD, DMT, and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Understanding how other psychoactive substances could influence the neurophysiological and psychological outcomes could guide more tailored approaches to psychedelic-assisted therapies if the results differ between substances, especially when focusing on the resulting differences and similarities between naturally occurring compounds and synthetically developed compounds.

Exploring the comparative efficacy of psilocybin against a broader spectrum of mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorders, would develop a more comprehensive understanding of the greater therapeutic potential of psilocybin that isn’t specifically focused on MDD. These recommendations aim to guide

future research endeavours towards a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of psychedelic-assisted therapies and their potential applications in neurotherapeutics and the treatment of other mental, behavioural, and somatic health disorders.

Acknowledgements

The author of this paper would like to thank Melanie Eddleman and Dr. Lia Walker for their advice and guidance through the writing of this manuscript. Special thanks to Dr. Lia Walker for taking her own personal time to build upon the research and create recommendations for the author based upon her own individual analysis of the proposed study.

References

Bakshi, A., & Tadi, P. (2022). Biochemistry, Serotonin. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Berger, M., Gray, J. A., & Roth, B. L. (2009). The expanded biology of Serotonin. Annual Review of Medicine, 60(1), 355–366. https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802

Calder, A. E., & Hasler, G. (2022). Towards an understanding of psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 48(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-02201389-z

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Day, C. M., Rucker, J., Watts, R., Erritzoe, D. E., Kaelen, M., Giribaldi, B., Bloomfield, M., Pilling, S., Rickard, J. A., Forbes, B., Feilding, A., Taylor, D., Curran, H. V., & Nutt, D. J. (2017). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: Six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology, 235(2), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Goodwin, G. M. (2017). The therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs: Past, present, and future. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(11), 2105–2113. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.84

Chodavadia, P., Teo, I., Poremski, D., Fung, D. S. S., & Finkelstein, E. A. (2023). Prevalence and economic burden of depression and anxiety

symptoms among Singaporean adults: Results from a 2022 web panel. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04581-7

Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., May, D. G., Cosimano, M. P., Sepeda, N. D., Johnson, M. W., Finan, P. H., & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Effects of Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy on Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 481. https://doi.org/10.1001/ jamapsychiatry.2020.3285

Daws, R. E., Timmermann, C., Giribaldi, B., Sexton, J. D., Wall, M. B., Erritzoe, D., Roseman, L., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2022). Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nature Medicine, 28(4), 844–851. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01744-z

de Vos, C. M., Mason, N. L., & Kuypers, K. P. (2021). Psychedelics and Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review Unraveling the Biological Underpinnings of Psychedelics. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724606

Ducharme, J. (2023, February 9). The future of MDMA, psilocybin, and psychedelics in the U.S. Time https://time.com/6253702/psychedelicspsilocybin-mdma-legalization/

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2013). Hallucinogenic mushrooms drug profile. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/ publications/drug-profiles/hallucinogenicmushrooms_en

Ferrari, A. J., Whiteford, H. A., Shadid, J., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., & Santomauro, D. F. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s2215-0366(21)00395-3

Goel, D. B., & Zilate, S. (2022). Potential Therapeutic Effects of Psilocybin: A Systematic Review. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30214

Greenberg, P., Chitnis, A., Louie, D., Suthoff, E., Chen, S.Y., Maitland, J., Gagnon-Sanschagrin, P., Fournier, A.-A., & Kessler, R. C. (2023). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

in the United States. Advances in Therapy, 40(10), 4460–4479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325023-02622-x

Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Carducci, M. A., Umbricht, A., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., Cosimano, M. P., & Klinedinst, M. A. (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1181–1197. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0269881116675513

Gulyaeva, N. V. (2017). Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity: An expanding universe. Biochemistry (Moscow), 82(3), 237–242. https:// doi.org/10.1134/s0006297917030014

Hasler, F., Grimberg, U., Benz, M. A., Huber, T., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2004). Acute psychological and physiological effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-effect study. Psychopharmacology, 172(2), 145–156. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1640-6

Hunt, K. (2023). Australia ushers in a new era of psychedelic medicine. CNN. https://www.cnn. com/2023/06/30/health/australia-mdmapsilocybin-psychedelics-medicine-wellness/ index.html

Ismail, F. Y., Fatemi, A., & Johnston, M. V. (2017). Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 21(1), 23–48. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.07.007

Kulkarni, G., Murala, S., & Bollu, P. C. (2022). Serotonin. Neurochemistry in Clinical Practice, 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07897-2_2

Kwan, A. C., Olson, D. E., Preller, K. H., & Roth, B. L. (2022). The neural basis of psychedelic action. Nature Neuroscience, 25(11), 1407–1419. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41593-022-01177-4

Ling, S., Ceban, F., Lui, L. M., Lee, Y., Teopiz, K. M., Rodrigues, N. B., Lipsitz, O., Gill, H., Subramaniapillai, M., Mansur, R. B., Lin, K., Ho, R., Rosenblat, J. D., Castle, D., & McIntyre, R. S.

The Neurophysiology and Pharmacology of Psilocybin

(2021). Molecular Mechanisms of Psilocybin and Implications for the Treatment of Depression. CNS Drugs, 36(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40263-021-00877-y

Lipton, R. B., Stewart, W. F., Diamond, S., Diamond, M. L., & Reed, M. (2001). Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: Data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 41(7), 646–657. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.15264610.2001.041007646.x

Lowe, H., Toyang, N., Steele, B., Grant, J., Ali, A., Gordon, L., & Ngwa, W. (2022). Psychedelics: Alternative and Potential Therapeutic Options for Treating Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Molecules, 27(8), 2520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ molecules27082520

MacCallum, C. A., Lo, L. A., Pistawka, C. A., & Deol, J. K. (2022). Therapeutic use of psilocybin: Practical considerations for dosing and administration. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyt.2022.1040217

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023, July). Major Depression https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/ statistics/major-depression

Olson, D. E. (2018). Psychoplastogens: A promising class of plasticity-promoting neurotherapeutics. Journal of Experimental Neuroscience, 12 https://doi. org/10.1177/1179069518800508

Ross, S., Bossis, A., Guss, J., Agin-Liebes, G., Malone, T., Cohen, B., Mennenga, S. E., Belser, A., Kalliontzi, K., Babb, J., Su, Z., Corby, P., & Schmidt, B. L. (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1165–1180. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0269881116675512

Schindler, E. A., Sewell, R. A., Gottschalk, C. H., Luddy, C., Flynn, L. T., Lindsey, H., Pittman, B. P., Cozzi, N. V., & D’Souza, D. C. (2020). Exploratory Controlled Study of the Migraine-Suppressing Effects of Psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics, 18(1), 534–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-020-00962-y

Smith, B. L. (2012, June). Inappropriate prescribing. Monitor on Psychology, 43(6), 36–40.

Wertheimer, T. (2023, June 30). Australia legalises psychedelics for Mental Health. BBC https:// www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-66072427

To My Friend

Breyonna Lanier

Will you continue to remember us

When days end, and memories fade with age.

When we run out of things to discuss, Does our friendship still get to hold a page?

Time, the starving consumer of the past, Could never steal the shine from your eyes

Or the way you beamed when a smile was cast.

To forget those would be worse than goodbyes.

So, when we meet next, let our days never close.

Let our laughter be loud and our joy known, For it’s your laugh I wish to hear the most, And it’s your joy I wish to make my own.

But, when night draws our time to an end, Know that you are forever my friend.

Horizontal Horizon

Skyler Davies

Jim Crow Sonnet

Tasia Huntley

In shadows cast by laws unjust and cruel

Jim Crow, a name that bore the weight of pain— A system meant to keep a people's rule Dividing hearts, like links in a rusted chain.

Through decades dark, they stood with strength and grace Their voices rose, a chorus for their rights. Injustice met with courage, face to face In unity, they faced the darkest nights.

Though Jim Crow's grip has loosened over the years

The scars remain, a testament to strife.

We strive for justice, face our deepest fears To build a world where all can share in life.

In history's pages, let this truth be shown Jim Crow may fade, but justice will be known.

Horror while running

Terror, escaping to a new life

Please, do not look back

Running

Jordan Goodfellow

My poem is a haiku based on some dark family past. My family is full of Russian Jews, and, after World War 2, the persecution and hatred towards Jews continued. So, this poem is about my great-great-grandfather, who walked across Europe to escape the Bolsheviks (the people trying to kill the Jews) and get on a boat to come to America for a better life.

Answering with Hope

Destiny VaughanDelivered at the Chowan University Senior Banquet on April 27, 2023:

As we pass on to bigger things, We need to remember what got us here.

Whether it was family, With their insane ways, Or friends that help us through the crazy days.

It could be God, Never leaving us.

Or ourselves,

Determined to get past every hour

Of endless lectures, numerous papers, Outrageous projects, and dreadful quizzes

That helped us to get here today.

Or just incredible luck, Appearing regularly.

Nevertheless, it began with Hope.

A simple four-letter word,

Giving us the ability to believe In something better—

A more promising future.

With intense struggles and victorious victories,

Where we wage battles within and without,

Finding the willpower

To move,

Not backward but forwards

On the straight yet winding road

Into an unknown future

With as much excitement and anticipation

As we can muster,

With nervous energy flowing through us,

Yet daring to have courage

To learn and grow

And fight for the impossible,

The unreachable.

While negative influences come and go

And try to steal our joy,

Our sense of purpose, We pushed through and made it here.

With the help of professors

And wonderful staff members, We will continue to rise

And show the world what Chowan Has helped shape us to be:

A generation of doctors and lawyers, Accountants and business associates, Artists and multi-talented teachers, Along with music leaders and great coaches

Helping to change our world for the better.

As we move forward

We’re looking at the days, Counting the hours, Whispering minutes, Watching for seconds—

Understanding we’re limitless, Even when the pressure is on.

But at this moment, This joyful moment, When you hold your diploma, Shout, even cry, “I made it, I survived, I finished!”

And through all these countless words,

Hope is here as I stand before you today;

Though you may not see it, Can’t even believe it, or just don’t understand it. Look around, there is hope Within these walls, and further on.

As we leave today, As we walk across that stage, As we depart from Chowan, Don't give up!

You made it this far.

Who knows where hope will take you?

Regardless, you will do just fine.

Thank you!

She Waited…

Jasmine Hendricks

You couldn’t understand how you broke her heart.

You’ve never tried to wear her shoes, while she tries to make a new start.

You would never comprehend the love that she offered to the distinctive you, Not the idea or any man near you. You were her rule breaker And her differentiator.

You assumed she was content.

With this hurt and public humiliation,

You think she chose these tears and character defamation. She dated, but in her heart she waited.

You decided against her, while she sought a way to make it.

You knew that she was unlimitedly available.

You gave and took her strength in the places she was capable.

She craved you now, you made her starve for later.

Your love was mediocre, her love was always greater.

Those tears you thought she faked for attention

Were actually from the scars she

never mentioned.

The times her heart said yes, her mind said no.

The minutes she attempted to plan, but many canceled based on your say-so.

The sacrifices she made, solely for your pleasure, Stemmed from the heartache you failed to measure.

You felt the love from her that she begged to feel from you.

She loved you past her, she was breaking, and you knew.

You allowed her to sit in a confusion, experiencing thoughts of uncontrollable crazy.

You forced her to live with answers of unsures and “maybe”.

You watched her in an internal world of insanity.

She chose you against all forces of humanity.

She waited….

She wasn't patient, but she saw you as worth it.

She waited…

So loyal to you, a man so imperfect.

She let you in and required that you bring nothing.

All she wanted was you, and you

were still in search of something. You felt respected and she felt less than.

You requested trust, when she had little to put her faith in. She asked to leave, but you guilted her into being still. Her option to walk away was no longer her free will.

A soul tied so tight, where would she go?

You knew not the depths of her love but will soon reap the seeds that you sow.

She waited, the long process she endured alone.

She was your consistent through all the unknown.

You almost lost your wife, being blind to her endurance.

You nearly gave away the best part of your life, giving her no reassurance.

You were almost a minute too late.

But she waited, just for you. She gave up for the last time, right before you decided to finally come through.

She waited...and somewhere deep inside, she will always wait. But she will never forget all of the heartbreak.

Are Psychopathy Assessments Ethical and Do They Accurately Predict Violence?

Katlyn GrayPsychopathy is a personality disorder characterized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as “fearlessness and/or boldness that is linked to interpersonal difficulties, delinquency, and aggression” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). One way to diagnose psychopathy in individuals is by assessing them with what is known as the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R) (University of Wisconsin Madison, 2023). If someone has a score that is above 30, then that person would be diagnosed or considered to be a psychopath. However, like many other psychiatric disorders, psychopathy is a spectrum; not all who are diagnosed are violent nor are they completely untreatable. Recent research has questioned the reliability of psychopathy assessments, and this has sparked concern among forensic psychologists about their use. Forensic mental health professionals are questioning if these tools for diagnosing psychopathy can accurately predict violence and if they are even an ethical tool to begin with. It is important to keep in mind that psychopathy is not an official diagnosis the way it used to be. To be considered a psychopath in the forensic psychology field, an individual would need to be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). Just like psychopathy, someone with antisocial personality disorder has a disregard for other people and other symptoms that those with psychopathy have. In today’s time, psychopathy’s formal diagnosis is known as ASPD.

Psychopathy Assessments

Psychopathy assessments have been used to inform psychologists about violence, threat management, and sentencing for many years. They are used to assess the presence and extent

of a psychopathic personality in individuals, most often those institutionalized in the criminal justice system. But recent research has questioned the reliability of these assessments, sparking concern about the ethics of their use. Many researchers are also questioning the chronicity of not only psychopathy but these other personality disorders as well, because research shows that psychopathic offenders appear to gain from treatment the same way that regular offenders do (Larson et al., 2022). Two of the most fundamental ethical standards in the field of forensic psychology and psychology in general are to promote well-being and to do no harm. Psychopathy assessments seem to provide no clear benefits to the patients, nor do they promote well-being, and these assessments could possibly cause harm that is associated with their use, which outweighs any social benefits.

Structured risk assessments are commonly used in secure settings to aid in the prediction and prevention of risky behaviors. It is accepted that structured risk assessment instruments outperform clinical judgment in the accuracy of prediction of violent and sexual behavior (Dawes et al., 1989). However, it has been argued that risk assessments may be limited to measuring a general construct of criminal risk rather than specific tendencies to violence as they were originally intended (Coid et al, 2011). For example, the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (2010) was developed to assess violence in those that were released from maximum security hospitals, and the Psychopathy Checklist Revised is meant to assess the degree to which an individual matches a prototypical psychopathic personality. Very few studies show information on the predictive ability of individual items.

Are Psychopathy Assessments Ethical and Do They Accurately Predict Violence?

Communication Style and Psychopathy

Many experts have warned against therapy with psychopathic individuals because of the possibility that these psychopathic offenders could manipulate a therapist into thinking they have improved, only to get out of prison and then commit the same or different criminal offenses. A huge hallmark of psychopathy is verbal deception, so the question is not if we should treat these individuals but how to treat them in a way that facilitates real change and keeps the psychologists from being fooled (Gullhaugen & Sakshaug, 2018).

The stereotypical communication style of psychopaths tends to come from the media for most people. People typically think of a psychopath as someone who is unaffected by things that are sad or upsetting and cold towards others. It is true that psychopathic criminals do tend to recall their criminal actions in a detached manner with less consideration for how these events affect their present functioning or the feelings of others (Brinke et al., 2017). However, we should not let the media show us what all psychopathic individuals are like because, as mentioned before, there is a spectrum.

Romberg et al. (2015) decided to take a closer look at this phenomenon of detached emotions in offenders and how they display their emotions. Romberg studied video-based dialogues of three well-known psychopathic offenders: Peter Lundin, Richard Kuklinski, and Aileen Wuornos. They were all previously interviewed about their selfperception, their childhood, any close relationships they had, their criminal intent, and their offenses. The study disclosed differences between explicit and implicit communication in these offenders. When the offenders were seen in control of the conversation, their communication appeared inert and emotionless. Disturbances in communication such as inappropriate laughing and being unable to articulate their feelings happened when individuals were emotionally activated, such as when they were asked about their upbringing. The study also indicated that the verbal expressions were defensive and contradictory. And the implicate verbal and nonverbal expressions happened to have negative feelings such as keenness toward being emotionally cold or special. While the results of this study cannot be generalized

due to the limited sample, it does present some potentially important information regarding the inconsistencies in implicate and explicate communication with psychopath offenders and should be further studied.

By studying the communication styles of psychopaths, we know now that these individuals seem to be vulnerable and that this vulnerability is expressed through their implicit communications, not their explicit communications. Therefore, forensic psychologists need to pay attention to consistencies between the two communication styles of psychopathic offenders to create change not only in these individuals but also in the ethical way that these therapies are supposed to be used. Studies also need to investigate perceptions of psychopathy as well, because they could gain insight into how psychopaths manipulate others so that psychologists can ensure that they are not being manipulated during therapy. With better understanding of the communication style of psychopaths, we could make better decisions in legal settings and in personal interactions.

Juvenile Psychopathy

In the past few years, there has been an interest in the concept of juvenile psychopathy among forensic psychologists and mental health professionals and if that term can be and should be applied to youth. One research group, which included 85 adolescent offenders, explored the relation between measures of psychopathy and treatment. They found that self-report measures predicted violence better than the Psychopathy Check List (PCL). However, the PCL and the Childhood Psychopathy Scale (CPS) were better at predicting physical violence. This is just one small study, though, so we are still unsure if youth would benefit from treatment. However, it does provide some information on a topic that is very underresearched. Caution in the application of the title “psychopath” to juveniles is advised until we can determine if it is a valid construct for someone so young (Skeem & Petrila, 2003).

One major concern regarding psychopathy is the developmental appropriateness of diagnosing this syndrome in children and adolescents. Some critics argue that there is

Are Psychopathy Assessments Ethical and Do They Accurately Predict Violence?

some level of psychopathy that is normal in youth, such as being irresponsible or showing a lack of forethought, so they worry about diagnosing someone that is in a developmentally normal stage. Instead of focusing on assessments that look for normative personality levels, we should focus on when the symptoms become non-normative or impairing to a child and their life (Salekin & Frick, 2005). The same goes for adult psychopaths; there are often normative variants of the symptoms in this disorder, and they could vary over the course of development. Therefore, we need to work to further refine the indicators of what makes someone psychopathic. Research needs to document when exactly the symptoms become non-normative and at what stage of development they are no longer normal.

Treatment of Psychopathy

Studies show that, after incarceration or hospitalization, those with a psychopathic personality may commit more serious or violent crimes, and they are more likely to end up reincarcerated or re-hospitalized compared to a non-psychopath. However, there are studies that show the treatability of psychopathy and reduced violence in psychopathic offenders when they are treated.

Approximately 24–35% of the population in Dutch forensic in-patient settings consists of psychopaths (Hildebrand et al., 2004), and 13–47% of European and North American forensic psychiatric samples consist of psychopaths (Patrick, 2006). Psychopathic patients are a challenge in forensic treatment settings, especially because they are often viewed as being untreatable by forensic mental health professionals. This belief that psychopaths are untreatable was challenged by Salekin (2002), who stated that, after reviewing 42 treatment studies, there is no convincing scientific evidence that psychopaths are untreatable.

Results of a recent study based on the PCL-R suggest that psychopaths are just as likely to benefit from treatment as non-psychopaths (Chakhssi et al., 2010). A study among 381 male offenders who were mandated to undergo residential drug treatment found that psychopaths who received intensive treatment were three times

less likely to be rearrested at their one-year followup than psychopaths who received less treatment (Skeem, 2008). Overall, psychopaths and nonpsychopaths appear to show the same pattern of reliable deterioration on the total score, and 22% of psychopaths showed a reliable deterioration in physical violence.

Treatment is routinely withheld from patients with a high PCL-R score because of the false belief that psychopaths are untreatable. Treatment should not be withheld from forensic patients based on PCL-R scores, because studies suggest that they are treatable. In the future, it is important to be able to predict which patients would benefit from treatment and which patients would not. Currently, according to research, withholding treatment is not necessary, nor is it ethical to do so.

Conclusion

More studies, investigations, training, and knowledge on relevant literature need to go into improving risk assessments, because the ones that are currently available to forensic mental health professionals don’t seem to be predicting individual violence the way they were made to. In addition, withholding treatment from patients with high PCL-R scores is something that is inherently unethical. And until new tools are made to be more ethical, clinicians need to be made aware of these limitations. In terms of applying the psychopathy diagnosis to youth, there are a number of limitations there as well, and this needs to be investigated further before we can make informed decisions about this concept being applied to them.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text Rev.). American Psychiatric Association.

Blakey, R., Askelund, A., Boccanera, M., Immonen, J., Plohl, N., Popham, C., Sorger, C., & Stuhlreyer, J. (2017). Communicating the neuroscience of psychopathy and its influence on moral behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 294. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00294

Brinke, L., Porter, S., Korva, N., Fowler, K., Lilienfeld,

Are Psychopathy Assessments Ethical and Do They Accurately Predict Violence?