CHICANO PARK STEERING COMMITTEE

Stewards of Chicano Park

P.O. Box 131050

San Diego, CA 92170

cpscchicanopark70@gmail.com

www.chicano-park.com

April 22, 2023

The Chicano Park Steering Committee welcomes the community to the 53rd commemoration of the founding of Chicano Park. All the hard work, numerous meetings, and commitment that was put into making this event possible was done from our hearts for you, nuestra gente, nuestras familias.

Chicano Park Day will again feature the famous lowrider car exhibition organized by Amigos Car Club, live bands, indigenous Aztec dancers, folklórico dancers, djs, speakers, children’s arts & crafts and much more, as well as other family activities and delicious food.

We would like to give special thanks to all the organizations and individuals who have worked closely with us to co-organize this event. Muchísimas gracias!

Everyone celebrate with us and enjoy this beautiful day, it is for you and your familia.

Lucas Cruz Chairperson, CPSC22 de abril de 2023

El Comité Directivo del Parque Chicano da la bienvenida a la comunidad al 53o conmemoración de la fundación del Parque Chicano. Todo el arduo trabajo, las numerosas juntas, y el compromiso que se requirió para hacer posible este evento, fue hecho de nuestros corazones para ustedes, nuestra gente, nuestras familias.

El tema de este año es Día del Parque Chicano 53: Encendiendo el Fuego Nuevo”

El Dia del Parque Chicano una vez más contará con la famosa exhibición de “lowriders,” organizada por el Amigos Car Club, bandas de música en vivo, danza indígena Azteca, danza folklórica, djs, oradores, artes y manualidades para niños y niñas, al igual que otras actividades para toda la familia, y ricas comidas.

Nos gustaría agradecer a todas las organizaciones y a todos los individuos que han trabajado muy estrechamente con nosotros en la organización de este evento ¡Muchísimas gracias!

Celebren con nosotros y disfruten este hermoso dia, es para ustedes y su familia.

Lucas Cruz Chairperson, CPSC53rd Annual Chicano Park Day

Kiosco (Chunky Sánchez Stage)

9:50 am Opening blessing

10:15 am La Rondalla Amerindia de Aztlán

10:35 am MC/DJ

11:05 am Aztlán Underground

11:35 am Via International

11:50 am Brown Berets speaker

12:00 noon FLAG RAISING, keynote speaker

12:50 pm Danza Azteca / Calpulli Mexihca

1:45 pm Unión del Barrio speaker

1:50 pm Ballet Folklórico Xochipilli

2:20 pm Amigos Car Club speaker

2:40 pm Bill Caballero & friends

3:25 pm

TimesandPerformersare subjecttochange

10:15 am

11:10 am

11:30 am

12:00

1:15 pm

Music Stage

10:00

10:25

11:35

12:00

1:15

1:50

2:15

Placita Stage

Chicano Park was founded on April 22, 1970 when the community of Logan Heights and Chicano movement activists joined forces to protest the construction of a Highway Patrol station on the present site of the park. The Highway Patrol office was, at the time, the final insult to a community that had already been degraded by the demolition of hundreds of homes to make way for Interstate 5 and the Coronado Bridge, in addition to the placement of toxic industries and junkyards, lack of community facilities, proper schools, jobs, social or medical services.

Protesters led by community activists, artists, Brown Berets, MEChA, and others took over the site and faced police and bulldozers for days while negotiations took place that eventually resulted in the land being given over for a community park. In the following days and months, similar actions by the same groups led to the forming of a Chicano Free Clinic, now known as the Logan Heights Family Health Center, and the Centro Cultural de la Raza in Balboa Park. The struggle for Chicano Park came to symbolize the Chicano-Mexicano people’s struggle for self-determination and self-empowerment. The more than 100 murals in the park portray the social, political, and cultural issues that form the struggle for the liberation of Chican@/Mexican@s.

Chicano Park has received international recognition as a major public art site. Since 1980, the Park has been listed on the Historical Landmarks Registry (San Diego Historical Resources Board), since 1997 on the California Register of Historical Resources. In addition, Chicano Park was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 23, 2013, and was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 23, 2016.

For more information on the Chicano Park Steering Committee, the stewards of Chicano Park, visit our website: www.chicano-park.com.

Chicano Park es La Tierra Mia:

An active and living space that honors and respects all who have walked the sacred land/ tierrasagradaof Chicano Park to transform, create, and affirm why the park exists and what it means to the community. Chicano Park retains the millions of steps that have been placed on its surface; the millions of words that have been spoken; countless songs that have been sung; speeches that have been recited; endless colors inscribed on its pillars; ceremonies and blessings that have been shared; prayers that have been spoken; meals that have been shared, and stories that have been told and created. All by activists, artists, musicians, storytellers, dancers, actors, lowriders, sembradores, caretakers, mothers, daughters, sons, fathers, and our ancestors/antepasados.

La Tierra Mia is a land-based storybook, a codex, a teaching, a history, all etched in its earth. It tells a story and history of preservation, perseverance, self-determination, healing, and liberation.

El Parque Chicano es La Tierra Mia:

Un espacio activo y de vida que honra y respeta a todos los que han caminado por la tierra sagrada del Parque Chicano para transformar, crear, y afirmar por qué existe el parque y lo que significa para la comunidad. Chicano Park retiene los millones de pasos que se han colocado en su superficie; los millones de palabras que se han hablado; innumerables canciones que han sido cantadas; discursos que han sido recitados; interminables colores inscritos en sus pilares; ceremonias y bendiciones que han sido compartidas; oraciones que se han hablado; comidas que han sido compartidas e historias que han sido contadas y creadas. Todo por activistas, artistas, músicos, narradores, bailarines, actores, lowriders, sembradores, cuidadores, madres, hijas, hijos, padres y antepasados.

La Tierra Mia es un libro de cuentos en tierra, un códice, una enseñanza, una historia, todo grabado en su tierra. Cuenta una historia e historia de preservación, perseverancia, autodeterminación, curación y liberación.

Sponsors

CHICANO PARK STEERING COMMITTEE, the stewards of Chicano Park, plan and carry out this annual commemoration of the takeover. The CPSC is an all-volunteer, grassroots organization comprised of individuals who donate their time and energy to ensure the development, maintenance, and expansion of Chicano Park. When the CPSC was established in April of 1970, the objective was, “to oversee (on behalf of the community) the continuing development and expansion of the Chicano Park and to insure that the park would be developed in a Chicano/Mexicano/Indigenous style.” One of the original goals was to transform the cold grey concrete and rock-hard dirt that once dominated the site into a glorious thing of beauty that would mirror and showcase the beauty, culture, and spirit of the Chicano people. As of 1997, Chicano Park and the Chicano Park murals have been on the list of California Historic Places and were added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 2013. On December 23, 2016, the park was awarded National Historic Landmark status.

Chair Por Vida: TommieCamarillo

Chair: LucasCruz

Vice-Chair: Tonantzin'Cina'Sanchez

Secretary: JessicaPetrikowski

Treasurer: IsabelSanchez

Sgt-at-Arms: JoeLeBlanc

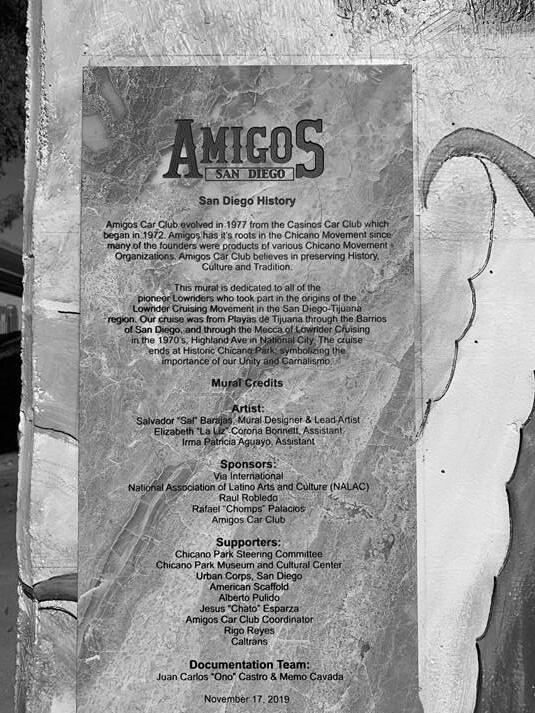

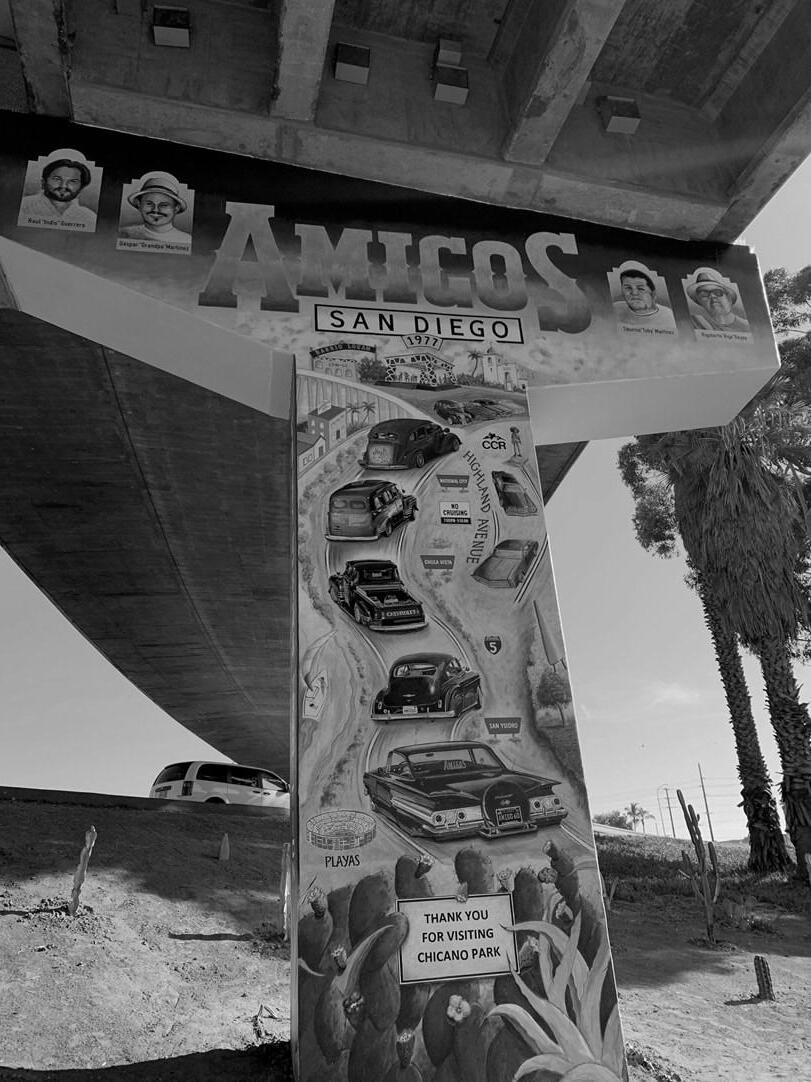

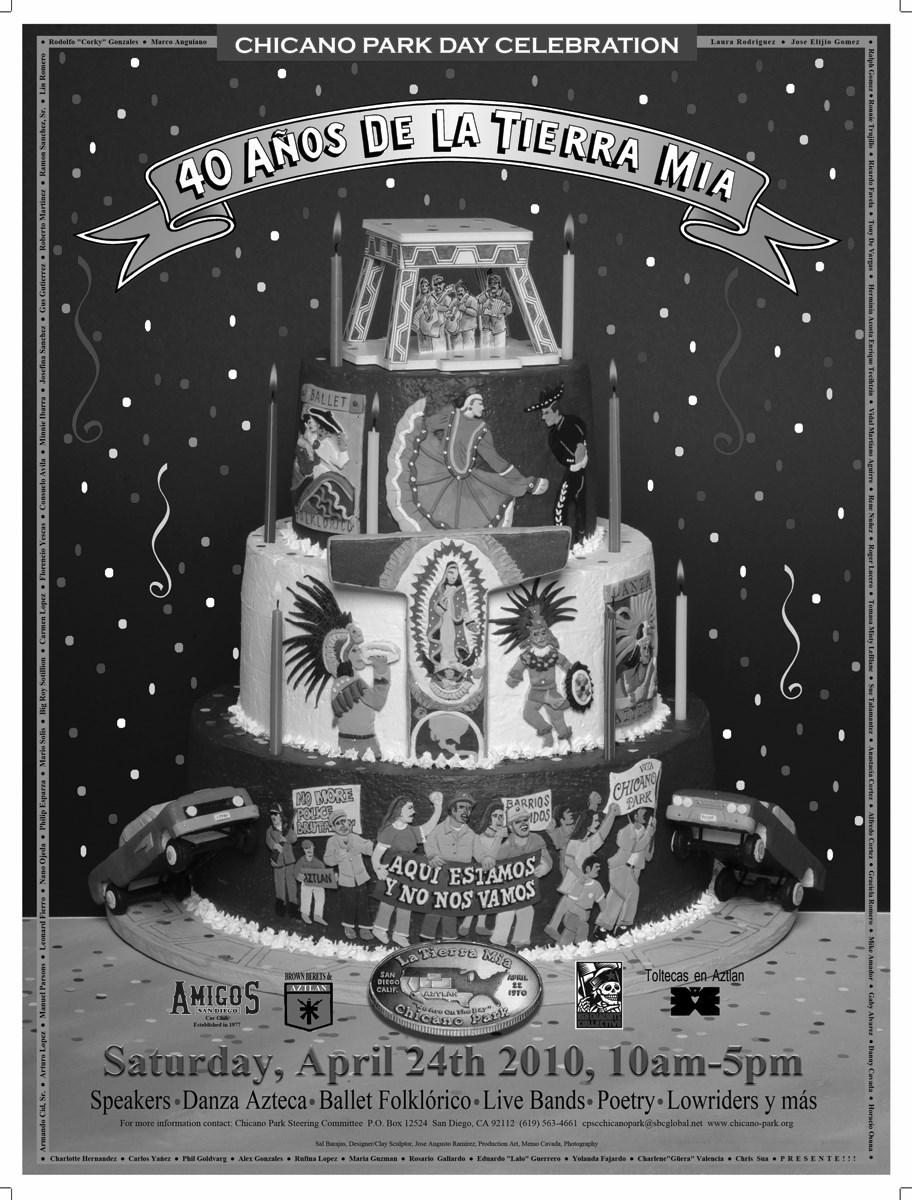

AMIGOS CAR CLUB, established in 1977, is the oldest active lowrider organization in San Diego County. Amigos has 46 years of promoting history, culture and tradition. Amigos congratulates the Chicano Park Steering Committee for 53 years of lucha in our community. They would like to extend appreciation to the lowriders for continuing to support this annual event. Many vehicles on display are show quality material and their goal is to promote positive role models to the youth. Amigos Car Club is a cofounder (1979) and proud member of the San Diego Lowrider Council.

VIA INTERNATIONAL is dedicated to building paths to self-reliance for an interdependent world. Since 1975, Via International addresses community needs by supporting community members to become agents of positive change. Programs emerge from community needs to improve quality of life through nutrition and ecology training, community leadership education, and microcredit and microenterprise support. The Voluntours programs offer educational travel and service

learning opportunities to engage with community development initiatives. The Via Institute provides a framework to nourish personal development, foster community engagement, strengthen organizations, and promote global dialogue.

CALPULLI MEXIHCA is a non-profit organization dedicated protecting, teaching and promoting the values of our indigenous cultures. Founded on Sept. 16, 2002 by the Flores family, Calpulli Mexihca has been recognized as ‘mesa’ by el General de Danza, Plascencia Rosendo Quintero since November 2008. Calpulli Mexihca has become a major social project. In addition to the teaching of Danza Azteca, their work also encompasses social activism and cultural diffusion in different levels to work closely with many renowned community organizations. Capitana Aida Flores ; Capitan Juan Flores.

BROWN BERETS DE AZTLÁN The National Brown Berets formed in 1967 in East L.A., striving for selfdetermination, they took militant action against the oppression of Chicano/Mexicanos. The San Diego Brown Berets started in 1970, participating in the takeover of Chicano Park and the Centro Cultural de la Raza (formerly the Ford building), and the occupation of the Big Neighbor (now Family Health Center). In 1972, the National Brown Berets began to break up. The San Diego chapter remained active as the San Diego Brown Berets. In 1989 the San Diego Brown Berets re-organized as the Brown Berets de Aztlán. In order to better define La Causa (the Cause), their patch was designed from La Causa to Aztlán. This defines their Causa: Tierra, Liberación , Revolución;Revolution, Liberating our Land of Aztlán. Through organization, self-determination, and unity we can liberate nuestra Raza, y tierra de Aztlán. Unite in the struggle to end police/migra terror on our Raza! Chican@ Power!

CHICANO PARK MUSEUM AND CULTURAL CENTER held its grand opening was on October 8, 2022. The inaugural exhibition was Pillars: Stories of Resilience and Self Determination. See pages 30 & 31 and visit https://chicanoparkmuseum.org or Instagram @chicanopark_museum for exhibits and event information.

CALIPOSAS PRESS is owned by Consuelo Manríquez, a long-time educator, community activist, and MC for Chicano Park Day and other events. On

Sponsors/MCs/Stages

March 19, Caliposas hosted the annual Chicano Park Day Pozolada Fundraiser at the home of Victor Cordero & family. Caliposas Press specializes in Chicano, Latino y bilingual books, CDs and more. See page 33 for pozolada fundraiser coverage.

TURNING WHEEL is a mobile classroom that teaches and serves the local community. It is designed as both classroom and a creative space where history and culture come alive through the telling and presentation of community story and history. We draw from the arts, literature, poetry, music, oral history, and the sciences to make knowledge relevant to the lives of the community it serves. The Turning Wheel Project is a partnership between the Chicano Park Steering Committee, the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center and the University of San Diego where it is housed in the Department of Ethnic Studies.

UNION DEL BARRIO celebrates Chicano Park as the beating heart of our peoples’ liberation struggle! ¡Esta EsMiTierra- EstaEsMiLucha!

Unión del Barrio is an independent political organization dedicated to struggling on behalf of la raza. Today, our communities suffer under terrible conditions. The intensity of the hatred and political poison our people are forced to endure is unprecedented. Unión del Barrio is convinced that our future must be different. We support the struggles for freedom and self-determination of all our sisters and brothers across Nuestra América, and we unconditionally uphold the right of self-determination of indigenous people and all poor and oppressed people worldwide. Since 1981, Unión del Barrio has led campaigns to resist migra and police violence, organized the active self-defense of our communities, and consistently advocated for the rights of workers, mujeres, young people, and prisoners. Now, more than ever, we need you to join Unión del Barrio to help build this movement for raza liberation!

Unión del Barrio es una organización política independiente dedicada a luchar en nombre de la raza que vive dentro de las fronteras de los Estados Unidos. Hoy, nuestras comunidades sufren terribles condiciones. La intensidad del odio y el veneno político que nuestra gente se ve obligada a soportar no tiene precedentes. En Unión del Barrio estamos convencidos de que nuestro futuro tiene que ser diferente. Nos hemos fijado el objetivo de construir una organización capaz de defender los derechos de la raza, y promover nuestros intereses como clase trabajadora. Apoyamos las luchas por la libertad y la autodeterminación encaminadas por

hermanas y hermanos en Nuestra América, e incondicionalmente defendemos el derecho de autodeterminación de los pueblos indígenas y de todas las personas pobres y oprimidas en el mundo. Desde 1981, Unión del Barrio ha liderado campañas para resistir la migra y la violencia policial, hemos organizado autodefensas en nuestras comunidades y abogamos constantemente por los derechos del pueblo trabajador, las mujeres, los jóvenes, y los prisioneros. Ahora, más que nunca, necesitamos que te unas a Unión del Barrio para ayudar a construir este movimiento por la liberación de la raza!

Webpage in English: https://uniondelbarrio.org/main/ Página web en español: https://uniondelbarrio.org/esp/ Introductory video: https://youtu.be/P4WzBoZtOu0

Email: info@uniondelbarrio.org

Social Media: @UniondelBarrio

YouTube:

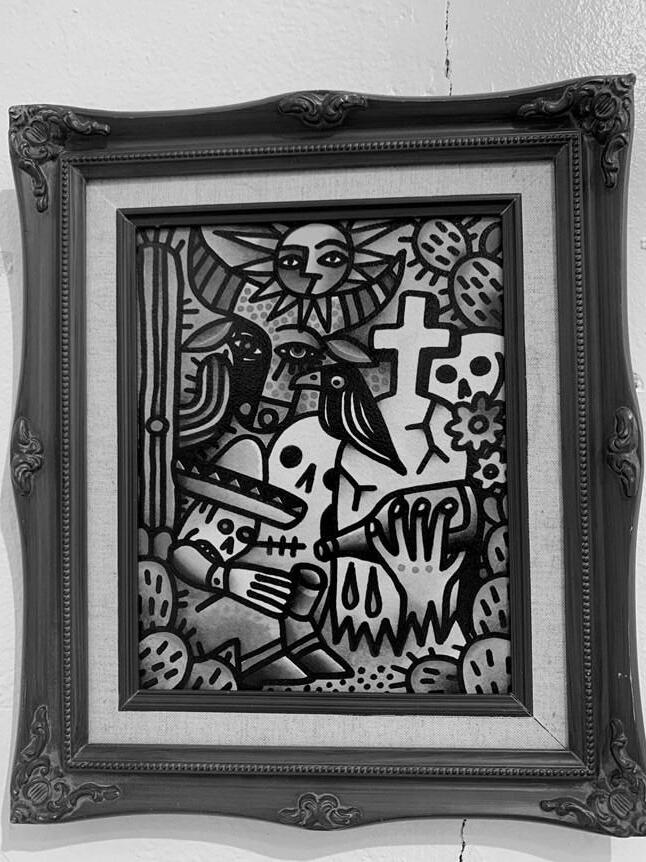

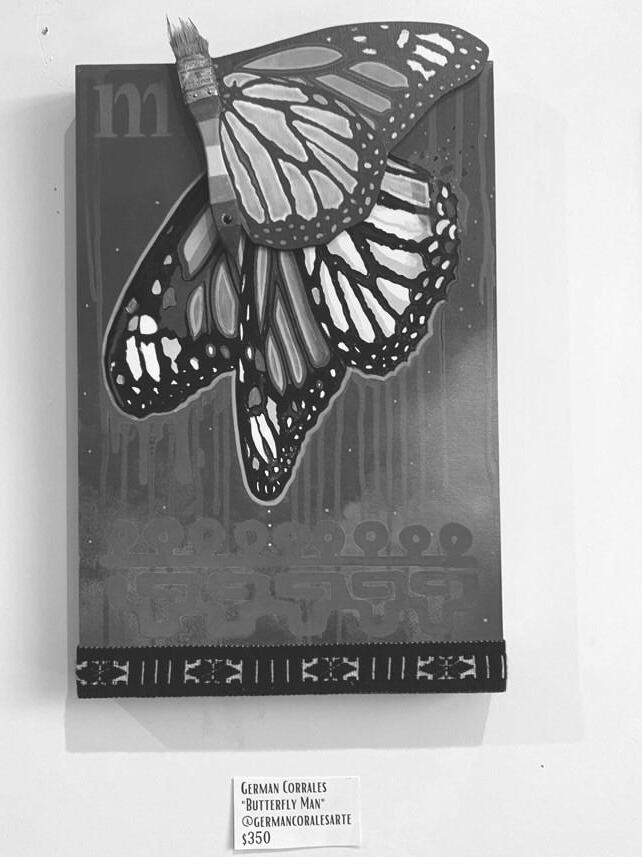

CHICANO ART GALLERY

Cesar Castañeda and Sholove (Erick De La Rosa) organized the 9th annual Chicano Park Day Art Fundraiser on April 8, 2023. See page 33 for event coverage.

MCs and Stage Crew

KIOSCO (Chunky Sanchez stage): Consuelo Manriquez, Hector Villegas

PLACITA stage:

Mil gracias to Fernie Lucero (DJ Rambo) & Mauricio ‘Wicho’ Sánchez for continuing the legacy of Fernando Lucero Sr. and Chunky Sanchez by overseeing the stages, sound logistics, and guiding the stage crew.

Performers

LA RONDALLA AMERINDIA DE AZTLÁN

La Rondalla Amerindia de Aztlán is an ensemble formed in American Studies professor, Dr. Villarino. The group participated unconditionally, providing “huelga” music during protest marches, Chicano/

Mexicano cultural music for Raza, from San Joaquin Valley to the north, to Imperial Valley to the Southeast and, of course, throughout San Diego County. For more than four decades, they have performed huelga” protest and social justice music at the request of our gente, to educate and to inspire our youth and our community with the perseverance and wisdom of Cesar Chavez. Through huelga music, La Rondalla Amerindia de Aztlán continues invigorating community spirit, working together to achieve the dream, vision and reality of social equality and social justice.

AZTLAN UNDERGROUND

Aztlán Underground navigates time and space between the contemporary and the ancient to create music that reveals the unrestrained voices of Indigenous peoples of the world. Through their own personal journey of enlightenment, they uncover the raw, painful, solitude of oppressed people, transforming it with unbridled energy and emotion into their hard-hitting musical style.

Aztlán Underground deconstructs colonization through the physical, emotional, and spiritual, via music. This is exemplified by the interjection of native instrumentation fused with jazz, punk, hip hop, punk and performance art, reflecting the urbanized native experience and artistry that is born of self discovery and analysis. Born in 1990 and still processing and progressing today, each album reflects different genre influences. They are currently working on a triple album release of native instrumentation, Dark ethereal rock, and hip hop. The lineup includes drummer extraordinaire-Caxo, multi talented bass and native flutes-Genetic Windsongs of Truth and Revolt aka Joe 'Peps', Og Founding vocalist and flutist-Bulldog (recently returned from hiatus), the young and multi-talented flutist and guitarist-Ethan Miranda, founding member and vocalist-Yaotl.

RICO XOCHIPILLI

through dance. Directed by Nelida G. Herrera, BFXSD was established in 2017 and also serves as the official house team for San Diego State University. Our team is privileged to represent and educate our community on the values of our heritage, every time we step on a stage.

BILL CABALLERO and FRIENDS

Caballero Music includes the Orquesta Bi-Nacional de Mambo (18 member band performing Latin big band music from 1950’s to present), the Latin Jazz Quinteto Caballero. Catch the Quinteto at The Rivera Supper Club. Caballero Music represents some of the finest musicians and performers in the San Diego/Tijuana Metroplex and they invite you to disfrutartheir Latin style entertainment. IG @billcaballeromusic

Ballet Folklórico

Xochipilli de San Diego is a community of dancers committed to showcasing the traditional art of Mexico's regions and colors

Juan Carlos Lozano is el Chicano de Oro, born and raised in San Diego, CalifAztlan. He makes music, clothing (Perseverance Clothing), organizes, and lives his life for Chicano/ Indigenous peoples and their national/ international allies. His music tells his life stories and the stories of others where he comes from. His music is his canvas, come vibe with him. Instagram: @chicanodeoro

Performers

KOZMIK FORCE

Kozmik Force is a rising Indigenous hip-hop group comprised of emcees Jaded Jag and Native Threat, whom hail from the Inland Empire. Since forming in 2017, over the span of three mixtapes, Kozmik Force’s mission has been to create & spread hip-hop with a strong message of cultural resistance, empowerment, sobriety, freedom, justice, equality, and decolonization

RUBY CLOUDS

Ruby Clouds is a sibling duo from San Ysidro / Tijuana, now based in Los Angeles, led by Claudia García, a graduate of Harvard University where she founded Mariachi Veritas. Her original music in English and Spanish reflects her experience growing up on both sides of the border and invites the listener to dream along. Their song “Un día de estos” is featured in the award-winning film “La Leyenda Negra” which premiered at Sundance 2020 and is now streaming on HBOMax. In 2021 Claudia was selected as a finalist and performer in the Original Songwriting Competition of the 27th Annual Mariachi Vargas Extravaganza. “Mexican Soul: How Claudia Garcia got mariachi fever” by Lydialyle Gibson, Harvard magazine, May-June 2022.

https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2022/05/montagemexican-soul

https://www.rubycloudsmusic.com/ https://www.instagram.com/rubycloudsmusic/

CUMBIA MACHIN

Cumbia Machin from San Diego is going to make you sweat with a healthy dose of smiling, drumming and dancing why not live your best life and move your body to the sounds of Cumbia.

Joaquin Hernandez created the project in 2010 to cure himself from a neurological disorder called focal dystonia. The disorder affects Joaquin’s ability to hold a drumstick so he uses a Zendrum to play electronic drums with his fingers. He started drumming in 1985 and has done International & national tours with metal, punk rock, reggae and salsa bands along the way.

CELINA ‘YAYA’ HEREDIA

Yaya has been singing for over 35 yrs with many local SD bands & now continues with solo performances. She belongs to the Christ The King Church choir, works for San Diego Unified School District, and is always willing to volunteer her voice at community spaces such as Sherman Heights Community Center and Aztlán Libre.

SLEEPWALKERS

The Sleepwalkers who hail from National City, CA, have been playing their brand of Chicano roots rock since 1994. They infuse a mix of rockabilly and cumbias for a sound that definitely gets folks out on the dance floor. Because of their eclectic style, they have played with the likes of the Texas Tornados, Big Bad Voodoo Daddy, Link Wray, Ronnie Dawson, The Blasters, Pancho Sanchez, Big Sandy, and Ozomatli to name a few. They have been nominated numerous times over the years for the San Diego Music Awards, winning Best Americana in 2020. IG: @thesleepwalkersband

QUETZALCOATL BAND

Hailing Southern California, Quetzalcoatl Band has an entrancing collection of sounds rooted in Aztec beats with a funk Latin Afro-Fusion of Tribal Rock, Cumbia and Reggae rhythms. In 2017 Quetzalcoatl Band released their debut album "La Catrina" on Blacklight Records, and subsequently released their follow-up album, “Rise Of The People Of The Sun” featuring the single ‘Xochitl’ which was filmed during Chicano Park Day 2019 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A6g7uGm-oEI) with shout outs to all the muralists/artists https://quetzalcoatlbandmusic.com/ https://www.instagram.com/quetzalcoatlband/ https://www.facebook.com/Quetzalcoatlmusic/

INDIGENOUS CATS

Indigenous Cats is a hip hop duo influenced by traditional indigenous teachings as well as the underground hiphop culture. With a unique blend of raw lyrics & soulful flavor, their vision is to impact the community by uplifting, inspiring and healing generations to come through their love for music.

GRUPO FOLKLORICO HERENCIA MEXICANA

Founded in 2018 by Director Federico Guerrero, Grupo Folklórico Herencia Mexicana is a non-profit dance company whose mission is to preserve, teach, and exhibit traditional Mexican folklore and culture through the art of music and dance. Beginning with 15 members who shared a passion for folklórico, the group has worked hard to maintain, promote, advocate and share our passion for the preservation

Performers

of traditional dances and history of Mexican folklore. Today, under the founder and artistic direction of Federico Guerrero, assistant director Jacqueline Alvarez, and instructors Mayra Del Rio, Alexis Barrera, and Rosemary Quijas, the group has over 175 active dancers and enthusiastically offers a dance academy for ages 8+ along with the professional company who travels locally and throughout California to perform at private and public events.

CHICANO DUKE

John Arroyo known professionally as Chicano Duke is a Mexican-American Rapper/Singer/Music Producer. He is the founder of Royalty Records originally from Victorville, CA but now resides in North Hollywood. He has done shows with Baby Bash and Lil Rob and you can follow him on Facebook and Instagram @ChicanoDuke

CUBAN MEMEE

Rapper, songwriter, actress & activist Cuban Memee is a first generation American whose family immigrated from Cuba in 1980. This Afro-Cubana performs hip hop and reggaeton to represent both cultures in her unique style. She loves her music and takes her craft seriously but also enjoys her community relationships as an activist. Memee is well known and supported throughout San Diego and takes high pride in her Afro Cubana culture. She plans to continue to bring hot and spice to the music industry if she can and is welcome.

LA DIABLA

La Diabla has been “cumbiando” since before it was cool (since 2000). The name “La Diabla” is derived from an old Celso Piña tune. Their music can be powerful and aggressive, romantic and cheerful, even dark and macabre. There’s something for everyone to dance to. The group had been described as Andres Landero meets N.W.A, but with masks, La Sonora Dinamita meets Daft Punk. Regardless, La Diabla is here to make you move and make dance floors bounce.

POISON CONTROL

Poison Control came together as a band early in 2003 to perform at the Chicano Park Day 2003. The band started jamming together as music students at the local school of performing arts although each

of the band members already had a good deal of previous musical experience. Poison Control is made up of Cuauhtemoc Chacon (lead guitar, bass, vocals) Ivan Velasquez (drums,) and Jacob Barnes (bass, vocals.) Their music stylings are primarily punk, and classic rock covers, and have recently written several excellent original songs. Each musician in Poison Control is aware of the societal ills that plague our time and place and have committed to take a stand through their music. They are a pure and visceral reflection of their generation.

DAVIANNA SERRANO

As a 2nd generation San Diego coming from Mexican heritage roots. The youngest of six siblings, 11 year old Davianna is an accordion player and folklórico dancer. She has been dancing since she was six years old and loves to make people smile with her dance and music. She only started playing the accordion when she was 9 years old. She has performed at the Coronado Talent and many community events, restaurants, parties and private gatherings. Davianna believes that music is spiritual and universal and she loves representing her Mexican culture and heritage. She is currently a 6th grader, balancing homework and school projects with practice sessions and performances.

JAH OLLIN

Jah Ollin is a musician/band based in San Diego. Ollin is an Aztec expression of immense depth that conveys intense and immediate MOVEMENT. Jah Ollin is a Roots Reggae group influ- enced by Akae Beka (Midnite), Bob Marley & the Wailers, Israel Vibration, Sly n’ Robbie and many more. Jah Ollin is keen on keeping the roots sound pure and spiritual, with an emphasis on mental liberation and One Love. Fol- lowing the teachings of His Imperial Majesty , Emperor Haile Selassie the 1st, Jah Ollin will forward Jah movement of Oneness, unifying the masses towards an international morality. Jah Rastafari!

MARIO AGUILAR and BEA ZAMORA

Dr. Mario E Aguilar, Capitan-General, and Beatrice Zamora Aguilar, Capitana-Generala, of Danza Mexicayotl have been teaching and leading the Chichimeca-Azteca dance tradition in San Diego for over 40 years. Mario was one of the first danzantes Chicanos to learn from General Florencio Yescas in 1974 where he and others formed the original danza Toltecas en Aztlán. Mario and Beatrice have continued to lead danza at Chicano Park since then and work collaboratively with other groups to continue this important indigenous tradition. Together with their son, Andres E Aguilar, daughter, Sofia M Aguilar and grandson, Dante T Aguilar, they are an example of passing

Speakers

on oral tradition from one generation to the next through their work with Danza Mexicayotl and the local Mesa of the Senor de los Danzantes. La Danza has been an inspiration for Chicanos connecting with their indigenous heritage since the 1970’s and has always been an integral part of ceremony at Chicano Park, el ombligo de Aztlán.

RIGOBERTO (RIGO) REYES grew up amongst the rallies of the United Farm Workers of America, listening to Cesar Chavez while he was playing marbles. At the age of 12, Rigo rode his bike 17 miles each way from his barrio in San Ysidro to Logan Heights to witness the takeover by the community of a little piece of land that today is known as Chicano Park. It was from this experience that his love for activism and social justice causes was born. Rigo is Director of Community Development at Via International, a non -profit community-based organization working at the USMexico border. He has been a member of the Chicano Park Steering Committee since 1976, has served on the board of directors for the Centro Cultural de La Raza, former member of the Brown Berets, Committee on Chicano Rights, a founding member of the Union del Barrio, former member of Casinos Car Club, co-founder of Amigos Car Club, and co-founder of the SD Lowrider Council, and board member of the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center (CMPCC).

ELISA SABATINI became President of Via International in 1998, when it was called Los Niños. In 2005, she oversaw both the formation of Los Niños de Baja California, an independent Mexican non-profit, and the transition of the U.S. organization to Via International. She continues to serve as President of both entities. Elisa brings years of experience working throughout Latin America with an expertise in microfinance and community development. She continues to oversee the expansion of the educational travel program, partnering with over 60 universities and high schools, with the end goal of making Via International a self-sustaining community development organization. Recently, she has worked to develop Corporate Social Responsibility programming providing relevant volunteer opportunities for local businesses

Brown Berets representative will speak on the Kiosco stage at 11:50am

Union del Barrio representative will speak on the Kiosco stage at 1:45pm

JULIE CORRALES

Julita Corrales is a first-generation Chicana, an auto-didactic chola, political activist, teen-mother, hoochie, feminist, survivor, actively engaged in her own decolonization. Zapoteca by blood, a U.S. citizen by her parents’ sweat and tears, she draws on her experiences to advocate for, and write about Chicanx issues. As a youth, Julie wrote many melodramatic rhyming love poems, some of which are still in circulation among California inmates. Since then, her essays have been published in the SanDiegoUnionTribuneand La Prensa , and her poetry has been published in Acentos Review, Anacua Literary Arts Journal, and Azahares Literary Magazine. She performs spoken word at various venues in San Diego.

DJs (Music stage)

BETTY BANGS is a Chicana artist from San Diego. Her art reflects her cultura and lifestyle. She is a mixed media artist and has helped paint murals in Chicano Park and throughout San Diego. She also is a local DJ known for playing vinyl.

New Fire Ceremony

On April 23, 2022 many community members gathered to celebrate the end of our first 52 year cycle and lit the new fire to guide us with energy into the next 52 year. We called it Quincuentagesimo-Segundo Dia del Parque Chicano and at 3am at the altar at the Kiosco we started the ceremony that ended at daybreak. This marked the end of the first cycle in our calendar based on our history, not the Mexicas, not the Toltecas, not the Olmecas, but for us, Chicanos/Chicanas history.

Fifty-two years ago our community took over and created several institutions: Chicano Park, El Centro Cultural de la Raza, and the Department of Chicano/a Studies at SDSU.

The New Fire symbolizes the spread of a new consciousness of unity and strength in our community. The fire represents our indigenous roots and our re-commitment to justice, liberty, and freedom.

Que Viva Nuestra Raza y Nuestra Parque Chicano!

From Tollan-Teotihuacan to Tollan-Chicano Park

Capitán-General Mario E. Aguilar Cuauhtlehcoc, PhD and Capitana Beatrice ZamoraThe rich tradition of La Danza Azteca-Chichimeca has been a part of the annual Chicano Park Day since 1974. The indigenous traditions and heritage of our people unite us with all the oth- er native tribes of the Americas. The danzas of San Diego are proud to be an integral part of Chicano Park and offer up our dances and our songs to the ancestors of yesterday, to the people of today, and to the ancestors to come.

The underlying 20th century past

The Chicano search for roots in ancient Mesoamerican cultures is deep and ever evolving. In the past, before “la Danza Tolteca-Chichimeca-Conchera-Azteca (from here on “La Danza”)” arrived in Aztlan in the early 1970’s, Chicano identity and spirituality was firmly rooted in “Spanishcentric” mestizaje . That is, our identity was rooted in what the Mexican government of the PRI (PartidoRevolucionarioInstitucional , PRI Institutional Revolutionary Party, an oxymoron of the finest type) used for over 60 years to create a modern national identity that served its purpose of tightly controlling all levels of Mexican society. This “revolutionary spirit” was in fact, a continuation of the status quo: elites fashioned themselves as the descendants of Spanish conquistadores, and a few “Aztec” virgins. Thus, “Aztec emperors” were paraded out every Mexican holiday as a noble example of Mexico’s ANCIENT past. However, the MODERN, LIVING indigenous people of today were seen as mere footnotes in history, necessary for mere production of artesaniafor tourists and not much more.

The Mexican mass media, a longtime ally of the PRI, would regurgitate films, songs, and revistas(magazines) that endowed super-human status to famous mestizos such as Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Pedro Vargas, Dolores del Rio, Maria Felix, etc. For most of the twentieth century, the Eurocentric Pigmentocracy of the PRI, PAN, and PCM dominated mestizo/Mexican identity. The murals of the 1920-50’s by great Mexican artists (Rivera, Siquei-

ros, Orozco, Tamayo, O’Gorman, etc.) repeated the official intellectual policy of the elite: the grandeur that was Tenochtitlan and the courage of Cuauhtémoc.

We Chicanos, like most Mexicans in Mexico did not understand the concept of elite mind control, just followed (and many still do) what we saw and heard on TV and the radio. However, outside the large cities of Mexico, like Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Puebla, there had always been a separate and strong allegiance to la partiachica.Especially in the small towns, pueblos, and villages where an historic pride in their own indigenous heritage thrived. Whether it was Zapoteca in Oaxaca, Otomi in Hidalgo, or Yaqui in the north, people carried an ancestral (but somewhat nebulous) “gut feeling” about their personal connection to Mexico’s indigenous past.

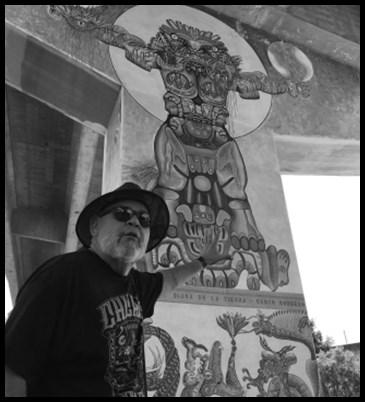

The Completion of the Aztlán Recollection

In 1974 General Florencio Yescas travelled north from Mexico City to Tijuana, BC and then over to San Diego. Several young male danzantes from Tacuba, Mexico City accompanied Jefe Yescas. Those included: Lazaro Arvizu, German Salinas, Gerardo Salinas, Jose Nolla, and Andres Garcia Pacheco. These courageous young men made the acquaintance of Juan Felipe Herrera and Alurista and through these two Chicanos were introduced to the community of San Diego. It was here that Florencio Yescas began to teach La Danza to a hungry Chicano audience. Don Florencio Yescas performed at the Guadalupe Church in Otay, at the San Ysidro Recrecreation Center, at the Centro Cultural de la Raza, and at Chicano Park. Several young Chicanos were excited and thrilled to be able to learn about their indigenous heritage. Those early danzantes who later became known as the Toltecas en Aztlan danzantes included: Mario E. Aguilar, Guillermo Aranda, Veronica, Claudia, Viviana, and Tupac Enrique, Felipe Esparza, Aztleca Magallan, and Guillermo Rosette. Eventually, Jefe Florencio moved to Los Angeles and made his home there until 1985 when he passed away. Meanwhile in San Diego the Toltecas continued to learn the tradition and traveled back and forth to Los Angeles.

In 1980, General Florencio Yescas asked Mario Aguilar to travel to Tepeyac, the Villa, in Mexico City to be recognized as a young Capitan de la Danza at the feast day of the Vir-

From Tollan-Teotihuacan to Tollan-Chicano Park

gen de Guadalupe. Jefe Mario Aguilar was the first Chicano danzante to receive this recognition and obligation. Several Jefes de Danza in Mexico recognized Mario on that day. Those included: Rosita Maya, Juanita Maya Diaz, Los Hermanos Plascencia, Miguel Avalos, Juan Pineda, Felipe Aranda, and others. This was a huge step for the Chicano community because it meant that they were now received into the traditional danza community of Mexico. When Mario returned to San Diego, there were conflicts that arose among the other Tolteca leads, and he left, along with several other danzantes, to start his own dance circle known as Danza Mexi’cayotl. The Toltecas en Aztlan continued for many years under the leadership of Aztleca, Felipe, and Guillermo Rosette. Eventually, Felipe moved to Los Angeles, Guillermo R. moved to Taos, New Mexico, and Aztleca continued as Toltecas en Aztlan until his passing. Subsequent danztanes picked up the Tolteca root and continued in San Diego. (Tupac Enrique had moved to Arizona and Guillermo Aranda moved to Watsonville, California much earlier.)

Danza Mexi’cayotl is proud to celebrate 40 years of consistent stewardship of La Danza in San Diego. They continued to lead the dance tradition in San Diego with their Capitanes Mario Aguilar and Beatrice Zamora and provided the leadership for the dance tradition at the annual Chicano Park Day celebrations for over 20 years, 1980-2000. They also created the ceremonial piece that included the evening vigil/velación and the Sunday dance offering at the park. The goal was always to pray for a peaceful and joyful gathering at the park. In the past several years, the Calpulli Mexihca under the leadership of Capitanes Juan and Aida Flores have led the Saturday community blessing and performance during Chicano Park Day.

In 2016, Capitan Mario Aguilar was recognized by dance

groups in San Diego and throughout Aztlan as a CapitanGeneral de la Mesa del Señor de los Danzantes. This recognition has brought together several groups working towards building a strong foundation of la danza. This tree has been planted to provide a grounding and a foundation for future generations of danzantes. The groups that are now working under Capitan-General Aguilar include: The Danza Mexi’cayotl of San Diego, The Calpulli Mexihca of San Diego, The Grupo Tonantzin de la Santa Cruz of San Diego, The Grupo Tonantzin of Santa Paula, California, and The Grupo Tlalloc of Denver, Colorado. This is the first Chicano Danza Mesa in Aztlan and has been widely recognized throughout the Americas.

Every year the groups in San Diego dance at Chicano Park to celebrate the park and the place where La Danza was first brought by General Yescas back in 1974. Since that time the danza continues to flourish at the park with several dance groups providing free classes each week. Visit the Chicano Park Steering Committee’s website for a schedule of classes.

Chicano Park has become a sacred danza site for all the groups of San Diego and throughout Aztlan. All through the year there are ceremonies offered at the park including, Dia de los Muertos in November, Cuauhtemoc in February, Sagrada Familia and Señor de los Danzantes in July, Santa Cruz in September, and our annual Chicano Park Day in April. The Kiosco at Chicano Park is considered a temple and a place where they build altars and call the spirits of the ancestors to come forth and give them strength in the batalla the battle to teach and educate our people about their beautiful indigenous heritage.

Que Viva Chicano Park por siempre!

Happy 53rd Anniversary Chicano Park!

Danilo Gudiel, Presente! He was born and raised in San Diego. He grew up on streets of Barrio Logan all his life. I remember him being so small and me walking him to Chicano Park before renovations were made, oh how he loved seeing the murals and the painters do their art! At a young age he learned the meaning of the murals and how much it meant to respect them by not tagging on them, and what story was behind each one of them. As he grew older he grew to love the park as much as I did, he took care of the park as if it was his second home. On July 19, 2021 he was celebrating the life of his dear friend who unfortunately passed away in Chicano Park. As family and friends gathered together, Danilo lost his life to homicide. Our community did everything in its power to help him, but due to police neglect he was unable to get first responders in time to help him. By the time he got the help that was needed, he had passed. Our community had experienced this as well in the death of his dear friend who they were celebrating that night. I hope that no one ever experiences this again, and that we place a stop to this. Victims should be able to get help from first responders instead of being treated as criminals. Now we have an altar in their name and their memory will always live with us and in the park. Long Live Danilo and Long Live Brian for we forever will hold in our hearts! And their love for the park will always remain

Brian Romo, Presente! Brian Alexis Romo was a ray of sunshine, lighting up every room with his big smile and nourishing laugh. He was born and raised in Barrio Logan. Chicano Park was his happy place. He attended marchas to defend it, he kept it clean and loved it until his last breath. Que Viva Brian!

Amigos Car Club

San Diego Califas

On behalf of Amigos Car Club, we would like to extend our deepest gratitude to the Chicano Park Steering Committee for their continued support, ongoing dedication, and struggle to keep Chicano Park s history and traditions alive. Congratulations on the 53rd Anniversary of the take over of Chicano Park. Recently, Amigos Car Club lost two of their active Carnales. Our deepest condolences to the Henry “Kiko” Roybal and Erick “Drifter” Gomez families, although they are no longer with us, they will never be forgotten, they will always be cruising the calles besides us, along with our other fallen members throughout the years. Amigos dedicates this year’s Car Exhibition to the memories of Kiko and Drifter, Presente!

Amigos hope to educate the public about the positive impacts lowrider car clubs have on this community and highlight the beauty and cultural significance of this art form. Amigos Car Club has always valued its role in the community as providing mentorship and positive role-models for barrio youth, and we hope through this efforts to engage and inspire more local youth to seek out positive artistic outlets that value community and history such as lowriding as an alternative to the negative paths that exist in this community such as gangs, graffiti and crime. Many of the local leaders both in local car clubs as well as community leaders in Barrio Logan are growing old. Amigos is partnering with the Chicano Park Steering Committee, Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center, and Via International to implement programs and strategies in our neighborhoods to engage and inspire local youth to become the future leaders of our communities. Educating them about the history and significance of the Chicano movement and lowrider movement are key elements in this process of developing civic engagement in the next generation. The mission of the Amigos Car Club is to promote a positive image of Lowriders and Lowrider culture and through our members, provide positive role models to barrio youth. Through our activities and through our unique art form, we raise awareness of Chicano culture and utilize cars as an expression of our history and culture.

The Turning Wheel Project: El Pueblo En Movimiento - A Community In Movement

For Information Contact:

Alberto López Pulido, Director of Turning Wheel and Professor of Ethnic Studies

University of San Diego

Email: apulido@sandiego.edu

Telephone: (619) 260-4022

ALL AGES ART WORKSHOPS

Art workshops are free and open to everyone during Chicano Park Day. Located near the National Ave side of the park, next to the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center

Gracias to coordinator MEX and his team of volunteers!

A Glimpse into the History of Chicano Park

Logan Heights

Envision a hurriedly-paced procession of students filing out of their Chicano Studies course at San Diego City College Only minutes earlier, fellow student Mario Solis had burst into the classroom of Professor Gil Robledo in order to publicly proclaim that a construction crew along with their equipment were presently underneath the newly erected San Diego – Coronado Bridge about to lay down blacktop for a parking lot for the newly proposed California Highway Patrol station in their historic neighborhood and Chicano barrio known as Logan Heights. Led by Rico Bueno, Josephine Talamantez, and David Rico, these student activists quickly mobilized around a ‘red alert’ call to action that brought together numerous other students, women, men, families, young and elderly activitsts and that by the end of this historic day on April 22, 1970 were two to three hundred people strong who had successfully evicted the construction crew and had occupied the land.

The community had created a human chain around the bulldozers and successfully stopped the construction workers from continuing their work. As Chicano muralist Victor Ochoa recall: “They actually took over those bulldozers to flatten out the ground and they started planting nopales, magueys, and flowers along with a Chicano flag being raised on a telephone pole.

takeover and served as the catalyst behind the creation of the Chicano Park Steering Committee who negotiated with city and state officials demanding that this piece of land be donated to the community. By the end of the twelfth day, the City of San Diego conceded and agreed to acquire the land from the State of California for the establishment of a park for the people that would become known as Chicano Park. Now five decades later, Chicano Park is still running strong, celebrating its fiftieth anniversary in April 2020, and is now a designated national landmark with one of the largest collection of outdoor murals in the world. The landtakeover under the bridge in Logan Heights represents an act of reclamation for generations of Chicanas and Chicanos seeking to hold on to their history in the face of powerful political and economic forces wishing to disrupt and erase their history and community of memory.

A Brief History of the Takeover

The Battle of Chicano Park: A Brief History of the Takeover

by Marco A. Anguiano(reprintedfrom30thChicanoParkDayprogram)

Chicano Park - Reclaiming Aztlán

On April 22nd and 23rd, 2000, we celebrate the 30th birthday of Chicano Park - "La Tierra Mia" - "Our Land." We commemorate this sacred place and we honor those people - some alive, some passed away - who planted, painted, protected and nurtured Chicano Park. The birth of the Park is the story of a barrio tragedy transformed into triumph. It is the history of the Chicano Mexicano people struggling to reclaim our heritage and our right to selfdetermination. The Park is where our history is enshrined in monumental murals. It is where we keep making history as we fight to preserve and defend a small piece of Aztlán known as Chicano Park in Barrio Logan, San Diego. By taking Chicano Park, the "myth" of Aztlán metamorphosed to reality. Aztlán - the southwestern United States was the ancestral land of the Aztecs. These ancient people migrated to the Valley of Mexico and founded an empire whose capital was Tenochitlan, now Mexico City. By claiming Chicano Park, the descendants of the Aztecs the Chicano Mexicano people begin a project of historical reclamation. We have returned to Aztlán - our home.

A Park for the Raza of Logan Heights, Aztlán

In many ways Chicano Park is like any other park. It's where families gather to have a reunion or a picnic. Where the crisp tempting smell of carne asada floats in the air. Where the high pitched giggles of chamaquitos and chamaquitas reverberate against the cement pillars as they climb, slide and swing on a playground that people struggled and sweated for.

It's a park where youngsters bounce a basketball on the court or challenge each other to a round of handball; Where couples exchange wedding vows in the Kiosko. Where a grandmother - nana - gently pushes a stroller along the walkways to pacify a grinning, gurgling baby. Unlike other parks, el Parque Chicano pulsates when trumpeting shells, throbbing drums and percussive rattles proclaim the beginning of a Danza Azteca ceremony.

Unlike other parks, Chicano Park displays on its monolithic pillars, one of the largest assemblages of public murals in North America. These awe inspiring murals are giant mirrors of our Chicano Mexicano history.

Unlike other parks, Brown Berets fired raised shotguns in militant salute while a Mexican flag was raised and waved defiantly during Chicano Park Day ceremonies. And unlike other parks, Chicano Park was taken by militant force by a community angered by decades of neglect, ignorance and racism.

La Raza Moves to Take the Land

For decades, the Chicano community in Logan Heights had thrived as a small, self-reliant neighborhood. Mexicanos

had always been part of the community. Since the 30's many more moved there as laborers, cannery workers, welders, pipefitters, longshoremen, etc. For decades, community residents had asked city officials to build a park n the barrio.

After World War II, the city, with complete disregard for Barrio Logan residents rezoned Barrio Logan to allow the influx of industry, junkyards, metal shops and other toxic businesses incompatible with a residential community. City burrocrats and politicians seemed to care less about the predominantly Chicano barrio.

By the mid-1960's, the community was bisected by the construction of Interstate 5, an eight lane freeway that tore Barrio Logan in half and displaced many lifelong residents. A community gathering place, the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe was no longer in the center of the Barrio. It now faced a barren asphalt freeway flanked by a 40 foot high cement retaining wall.

According to Victor Ochoa, a Chicano Park mural coordinator from 1974 through 1979, "They threw Interstate 5 in the barrio, taking nearly 5000 families out of the barrio." When the Coronado Bridge, which intersects Interstate 5 in the heart of Logan Heights, was completed in 1969, it left a jungle of concrete pillars where many families had lived.

The "Paul Revere" of Chicano Park

On April 22, 1970, Mario Solis, a student at San Diego City College ditched class and was strolling casually through the Barrio Logan in the area below the bridge. He ran into construction crews, equipment, machines and bulldozers.

Solis asked the construction workers, "what are you going to be doing here?"

The crewmen responded that they were "building a parking lot for a Highway Patrol station"

Solis was stunned. He told the crew that the people of the community had other plans. He said, "It'll be a park!" The construction crew cackled and laughed in response. Little did they know who would have the last laugh.

Solis rushed back to City College and interrupted a Chicano Studies class taught by Gil Robledo. He alerted the students in the class and demanded to know, "...what are you guys gonna do?"

Students and Activists on High Alert

Robledo's students who included Rico Bueno, Josie Talamantez, David Rico and others "went on red alert," according to some of those present. Bueno wrote and printed flyers and directed others to area schools and to surrounding barrios to sound the alarm - that this was the final straw. Bueno, a Vietnam veteran later threw away his

A Brief History of the Takeover

service medals in protest against the war at a Chicano Moratorium march.

Women, men, children, activists, students, residents the youth, the elderly and entire families gathered at the construction site. At day's end, two to three hundred people had congregated. They evicted the construction crew and seized the land.

Solis, a Brown Beret, as well as a student, commandeered a bulldozer and ignited and gunned its engine. He begin flattening the land while others planted cactus, plants and trees. The people begin to build a park. Long time barrio residents like Laura Rodriguez brought tortillas, rice, beans and tamales to feed the rebels.

"What I still remember is that there were bulldozers out there," says Ochoa. "And women and children making human chains around the bulldozers and they stopped the construction work. They actually took over those bulldozers to flatten out the ground, and they started planting nopales and magueys and flowers. And there was a telephone pole there, where the Chicano flag was raised."

Police and Authorities are Stunned

According to veteran activist David Rico, current chairman of the Brown Berets de Aztlán, "When the cops showed up during the takeover of the Park, they demanded to know who the leaders were, so we pointed to somebody over there and that somebody would point to somebody else who would then point somebody else - you had a lot of confused cops. We had the system very, very confused."

Al Puente, then a San Diego police officer on the Barrio Logan beat, years later divulged that the police department was confused since they had never experienced such an incident before - where an entire community had rebelled. Although Puente had earned a reputation as rough cop in the barrio, years later he related that he warned police against attacking the protesters since many women and children were among those at the site.

The land underneath the bridge was occupied. An unprecedented coalition of barrio residents, students, and community activists, Brown Berets and Raza from barrios throughout San Diego and Aztlán united and confronted the bulldozers and stopped the construction of a Highway Patrol station. At a community meeting that night, activist Jose Gomez stated, "the only way to take that park away is to wade through our blood."

Chicano Park Steering Committee formed

On April 23 the Chicano Park Steering Committee was formed to direct the community effort to build a park and confront state and city authorities. Activists demanded

that the property be donated to the community as a park in which Chicano culture could be expressed through art.

"Our community had already been invaded by the junkyards, the factories and a bridge had even been built through our barrio," declared Jose Gomez, "some of us decided it was time to put a stop to the destruction and begin to make this place more livable."

"We are ready to die for the park," Salvador "Queso" Torres, a community artist shouted to a gathering of city and state officials while supporters stamped their feet in rhythm and shouted, "Viva la Raza!"

The Coronado Bay Bridge was built at the height of the Chicano Movement. There was a great awareness at the time about the militancy that was all to often necessary to attain our rights. The establishment of a California Highway Patrol station under the bridge was a final insult to the people of Barrio Logan, a community that already had many grievances against local police.

The occupation of Chicano Park lasted twelve days. People of all ages worked together to clear the land and plant it. Supporters arrived from all over the state. Finally an agreement was reached between the Chicano community and the city, which agreed to acquire the site from the state for the development of a community park.

Chicano Power Peaks in San Diego

Many of the same activists involved in the takeover of Chicano Park were also central to the occupation and founding of the Chicano Free Clinic (now know as the Logan Heights Family Health Clinic) and the Centro Cultural de la Raza in Balboa Park.

The creation of Chicano Park was a defining moment in Chicano history and in the history of Barrio Logan, as well as the City of San Diego. Respected leader Josie Talamantez, then an 18 year old student at San Diego City College and a resident of Barrio Logan, explained the exaltation of the community in the park takeover:

"I was living a block from the site and my family had been very much involved with trying to get a park in this area for a long time. I felt proud. It was the first time that I had seen Jose's (Gomez) mother and my mother and the little kids and a lot of the people in between all working together."

One of the park's original muralists Mario Torero, linked the Park to Chicano identity: "We can't think of Chicanos in San Diego without thinking of Chicano Park. It is the main evidence, the open book of our culture, energy and determination as a people."

Ramon "Chunky" Sanchez, composer and singer of the rousing anthem "Chicano Park Samba," said, "There's an energy there that's hard to describe - when you see your people struggling for something positive, it's very inspir-

A Brief History of the Takeover

ing. The park was brought about by sacrifice and it demonstrates what a community can do when they stick together and make it happen."

Ernesto Bustillos, another veteran activist termed Chicano Park, "A Liberated Zone," where Raza from all walks of life, students, barrio residents and activists joined forces to retake our land. Chicano Park has provided us with the freedom to practice and express our ideas, our culture and our traditions. In short, the struggle for Chicano Park has become symbolic of our Raza's struggle for selfdetermination, our right to Aztlán and who we are as an indigenous people.

A Never Ending Story

There is no end to the story of Chicano Park. It is a living history. As long as Raza take responsibility to preserve and defend the park and Barrio Logan, it will survive and thrive. Since the reclamation of the land, there have been many difficult and exhausting struggles to preserve and defend the park. We highlight a few:

Grand Jury Attacks

The battles included the San Diego County Grand Jury's so called "investigation" into Chicano Park Steering Committee which resulted in the evacuation of the Park building by the Chicano Federation in 1979. The Chicano Park Steering Committee has been homeless since, but holds meetings throughout the community and is open to anyone who wants to be involved.

Building the Kiosko

The construction of the Kiosko (1972-77) went through a maze of San Diego City burrocratic red tape. After years of meetings the project was hijacked and funding withheld by so called city council representative Jess Haro. Haro wanted a "Spanish style" architecture for the kiosko." When finally confronted at a community meeting, Haro backed off. The Kiosko was dedicated in 1977.

All the Way to the Bay

The "All the Way to the Bay" (1970-88) campaign spearheaded by Ronnie Trujillo of the CPSC asserted the right of Barrio Logan residents to have the only access to the bay and to extend Chicano Park all the way to the waterfront. Activists challenged the San Diego Port District and other agencies from San Diego to Sacramento. Ground was broken for the bay park in 1987 and the park completed in 1990.

The Murals and the Retrofit

In the mid-1990's, Cal Trans, the agency responsible for the San Diego Coronado Bay Bridge, proposed an earthquake safety bridge retrofit plan that would've destroyed the Chicano Park murals. In response certain community "representatives" formed the "Right Directions Committee" to squeeze Cal Trans for "mitigation money."

The Right Directions Committee assumed that the retrofit

was a foregone conclusion and the murals would be inevitably destroyed. They wanted to press CalTrans for their pet projects in exchange. This "committee" began holding forums at the Barrio Station. When the Chicano Park Steering Committee found out about this "movida," mural supporters rallied to the forums and challenged Cal Trans and their proposals. The Right Directions committee dissolved itself in the face of community opposition to the retrofit.

After many militant marches, press conferences and negotiating sessions with Cal Trans, they relented and under the advise of professional engineers found a method of retrofitting the pillars that spared the murals. This retrofit work continues to this day, while the Chicano Park Steering Committee is the watchdog of the construction.

Even in the Quietest Moments

Then there are the meditative moments in Chicano Parkwhen the din of the traffic evaporates and you're alone facing the monoliths of history - prisms reflecting our lives, our history, and our struggle.

It's our church, where we reflect on the spirit of those who struggled to create and preserve the Park.

It is our school, where we learn our story - our history written, painted and told by us for generations to come.

It's also during these contemplative moments when Chicano Park becomes the paramount icon of our Raza's aspiration to control something meaningful in our livesChicano Park symbolizes our sacred right to selfdetermination.

References:

1) Historic Resource Evaluation Report for the SDCoronado Bay Bridge, Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals, Jim Fisher, staff historian/planner; 1996

2) Made in Aztlán, Centro Cultural de la Raza, fifteenth anniversary exhibition catalog; Philip Brookman and Guillermo Gomez -Peña, editors; 1986

3) Chicano Park Day programs, 18th, 20th and 27th anniversary editions; 1978, 1980, 1998

4) San Diego Union Tribune, 1995,1996, 1997.

Chicano Park 1970-2010: 40 AÑOS

On a beautiful spring afternoon April 22, 1970, to be exact, there was a Chicano barrio, in San Diego California, that was inspired and motivated to make that blind leap into eternity that would become a legacy in Chicano history. This was a legacy that was fueled by the social and political movements of the 60’s: five political assassinations of John Kennedy, Malcolm X, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert Kennedy, and L.A. Times reporter Ruben Salazar; the Vietnam War, the public school walkouts of 1968 led by the Brown Berets, the Black Panthers and the Puerto Rican Young Lords taking their banners to the streets of America. Something was obviously wrong, and people everywhere were determined to do something about it. At that particular time in history, words were blown away by the wind-and actions were what counted.

In the city of San Diego, countless families had been displaced from their homes alongside Interstate 5 from San Diego to the Tijuana Border. Very soon after that, many more homes and families in Barrio Logan were displaced by the building of the Coronado Bay Bridge. The thriving tuna cannery waterfront industries began to diminish as San Diego officials told the community that all this was for the betterment and progress of San Diego. This was a difficult reality to accept as people lost their homes and their jobs and were forced to relocate from the sacred land where their roots were entrenched for decades. The community at this time in history felt there was a need for a community park. In an effort to quell down the cries for justice and a park, city officials promised that eventually there would be a park in the area. Not quite so! When Mario Solis was walking by the barren land and saw two tractors grading under the bridge, he stopped one of them and asked are you grading for a park? The tractor driver quickly replied that no, they were grading for a Highway Patrol substation, not a park. Mario quickly took the news to City College MECha, and the word spread like wildfire amongst Chicano activists, students, and the community. Chicanos throughout the community mobilized on April 22, 1970. The people walked on the barren land with their picks and their shovels and took it over to declare it for use as a community park.

Chicano Park has been an educational lesson, a historical lesson, a political lesson, a social lesson and a lesson in heritage. It has taught many of us the art of community organizing, dealing with political bureaucracies, and making the best out of while working with limited resources. We have learned that if you want to accomplish something in life, you must be committed, consistent,

and determined to your cause. As Chicanos we refer to this commitment as “lacausa”. Chicano Park was lacausafor Barrio Logan on April 22, 1970. The community was focused on the reality and necessity for a park in the limited barren earth that was left after the intrusion of Interstate 5 and the Coronado Bridge through what was once a thriving, vital community. The mural projects on the cold ugly pillars gave life and energy to the inspirations of community residents that may have been on the verge of giving up. We began to seek and find deep-rooted identities that gave us hope, courage and strength to defend our presence and existence on this earth. The formation of the Chicano Park Steering Committee was equivalent to the formation of an indigenous tribal council to oversee their people, their land, and their cultural existence. For forty years, this committee has functioned with community members from all walks of life that have been dedicated to the “labor of love” for a small park that has symbolized the importance of struggle and sacrifice for the betterment of humanity and respect for others. Members have come and gone and to this day, there are, and have been, many supporters of the cause of Chicano Park. On this 40th anniversary the Chicano Park Steering Committee extends a deep sincere thank you to everyone that has been touched by the spirit of Chicano Park. To all the musicians, danzantes, folklóricos, poets, artists, voladores, lowriders, seniors, and children, we thank you for 40 years of love and support.

Barrio Logan and Chicano Park may well be the last stronghold in San Diego, and for that matter, in Aztlán. The last stronghold where memories of Zapata, Villa, Geronimo, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Morales, Hidalgo, Corky Gonzales, Cesar Chavez, la Adelita, La Valentina and countless more revolutionaries motivated only by acts of love for the struggle and suffering of their people and tribe.

The Chicano Park Steering Committee welcomes everyone to the 40th anniversary of Chicano Park.

In the words of José Elijio Gomez, the first chairman of the CPSC,

“Chicano Park is not a big park, but it’s our park, and in our style”

Chicano Park 1970-2010: 40 AÑOS

Chicano Park 1970-2010: 40 AÑOS

by Ramón “Chunky” San chez ; traducción de Carlos Martell (reprintedfrom40thChicanoParkDayprogram)

by Ramón “Chunky” San chez ; traducción de Carlos Martell (reprintedfrom40thChicanoParkDayprogram)

Una hermosa tarde primaveral abril 22, 1970, para ser exacto, había un barrio Chicano en San Diego California, que se inspiró y se motivó a tomar el gran salto a la eternidad que se convertiría para siempre en un legado histórico en la historia chicana. Este fue un legado fomentado por los movimientos sociales y políticos de los años 60… cinco asesinatos políticos: John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Dr. Martín Luther King Jr., Robert F. Kennedy, y el reportero de LosÁngelesTimes , Rubén Salazar. La guerra de Vietnam, las protestas estudiantiles del 68 en California, dirigidas por los Brown Berets, el movimiento de las Panteras Negras y los Puerto Rican Young Lords, llevaban sus banderas a las calles de América. Algo estaba obviamente mal, y la gente común por todas partes estaba determinada en hacer algo. En ese momento histórico, las palabras se las llevaba el viento y las acciones eran lo único que importaba.

En la ciudad de San Diego, numerosas familias habían sido desplazadas de sus casas por el “Interstate 5”, desde el centro de San Diego hasta la frontera con Tijuana. Muy pronto después, muchos más hogares y familias del Barrio Logan fueron desplazadas por la construcción del puente a Coronado. La floreciente industria pesquera del atún empezó a desaparecer, mientras los oficiales de la ciudad de San Diego le decían a la comunidad que todo esto era para el bien y el progreso de la ciudad.

Este fue un concepto difícil de aceptar para la gente que había perdido sus hogares y sus trabajos, y ahora estaban forzados a mudarse de la tierra sagrada en donde habían atrincherado y desarrollado sus raíces por décadas. La comunidad en este momento sintió que se necesitaba un parque comunitario. En un esfuerzo por callar las demandas de justicia y de un parque, la Ciudad prometió que eventualmente habría uno. ¡Pero esto no sucedió así! Cuando Mario Solís estaba caminando por aquel terreno baldío y vio a dos tractores nivelando la tierra debajo del puente, el joven le preguntó a un conductor, “¿Estas preparando la tierra para un parque?”, y el conductor le respondió que no, “estamos preparando la tierra para una estación de la Patrulla de Caminos, no un parque”, Mario rápidamente fue con esta noticia al grupo MECha del City College, y la noticia se divulgó como fuego entre los activistas chicanos y estudiantes. En todos los niveles de la comunidad, Chicanos empezaron a movilizarse, y el 22 de abril de 1970, la gente caminó al terreno baldío con sus picos y sus palas, y tomó el terreno declarándolo de uso comunitario.

El Parque Chicano ha sido una lección educacional, una lección histórica, una lección política, una lección social y una lección sobre nuestra herencia. Nos ha ense-

ñado a muchos de nosotros el arte de la organización comunitaria, tratando con burocracias políticas, y aprender a cómo ser eficientes con recursos limitados. Hemos aprendido que si uno quiere lograr algo en la vida, uno tiene que tener compromiso, ser consistente, y estar determinado en llevar acabo su causa. Como Chicanos nos referimos a este compromiso, como “La Causa”. El Parque Chicano fue “La Causa” del Barrio Logan aquel abril 22 de 1970. La comunidad estaba enfocada en la realidad y en la necesidad de tener un parque en el espacio limitado que quedó después de las invasiones del Interstate 5 y del Puente Coronado, en donde una vez hubo una floreciente comunidad cultural. El proyecto de los murales en los pilares feo y fríos le dieron vida y energía a la comunidad de residentes, que tal vez hubieran llegado al borde de la derrota. Empezamos a buscar y a encontrar identidades con profundas raíces que nos dieron esperanza, valor y fuerza, para defender nuestra presencia y existencia en esta tierra. La formación del Comité Directivo del Parque Chicano fue el equivalente a la formación de un consejo tribal indígena que velara por su pueblo, por su tierra y por su existencia cultural. Durante cuarenta años, este comité ha trabajado con todo tipo de miembros de la comunidad que se han dedicado al “trabajo amoroso” del Parque, el cual ha simbolizado la importancia de la lucha y el sacrificio para el mejoramiento de la humanidad y el respeto de otros. Miembros han ido y venido, pero hasta este día, ha habido muchas personas que han apoyado la causa del Parque Chicano. En este 40o Aniversario el Comité Directivo les extiende un sincero agradecimiento a todos los que han sido conmovidos por el espíritu del Parque Chicano. A todos los músicos, danzantes, folkloristas, poetas, artistas, voladores, lowriders, a los mayores y a los niños, les damos las gracias por 40 años de amor y apoyo.

El Barrio Logan y el Parque Chicano, tal vez sean los últimos bastiones Chicanos en San Diego, o tal vez en todo Aztlán. Este es el último bastión donde la memoria de Zapata, Villa, Geronimo-Goyakla, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Morales, Hidalgo, Corky Gonzales, César Chávez, La Adelita, La Valentina, y otros incontables revolucionarios motivados solamente por actos de amor para llevar acabo la lucha por, y el sufrimiento, de sus pueblos y sus tribus. El Comité Directivo del Parque Chicano les da la bienvenida a todos, al 40 o aniversario del Parque Chicano. En las palabras de José Elijio Gomez, el primer director del Comité Directivo, “ElParqueChicanonoesunparquemuygrande,peroes nuestroparque,yennuestroestilo”

Memories of Chicano Park Origins

Memories of Logan Heights and the Chicano Park Takeover

by Josephine S. Talamantez (reprintedfrom44thChicanoParkDayprogram)It is a difficult task to discuss the “Take-Over” of Chicano Park without acknowledging the history of Logan Heights, its residents, and the current day politics of the Barrio .

The first peoples in Logan were the Kumeyaay. They migrated between the mountains and a low land village located where the 32nd Street Naval Terminal is currently located. Raza in the area date back to the late 1800’s, although Spanish and Mexican arrivals in the San Diego region date back to 1700’s and the first Spanish expedition lead by the Portuguese explorer Juan Cabrillo was in the 1500’s.

Logan Heights was the first land development and the oldest neighborhood in San Diego, established in the 1880’s. The geography of the streets is strategically designed at an angle to provide the most spectacular view of the San Diego bay. The streets are named after US military war Generals/personnel and today includes one of our most cherished heroes, Cesar Chavez.

By the 1900’s the railroad and the automotive industry paved the way for further real estate development, Anglo residents of Logan Heights began to take flight to the newer developing suburbs. “Logan Heights due to its proximity to the fishing and lumber industries and discriminatory housing covenants became the home to San Diego’s Mexican and Negro citizens.” In other words, we were not allowed to live anywhere else.

By the 1950’s and 1960’s the neighborhood had become extremely neglected by the City of San Diego. It had been re-zoned to include industry and set the stage for the invasion of auto dismantlers and other toxic businesses setting up shop next to homes and schools. Eminent domain policies were instituted to take property from residents in preparation for the construction of Interstate 5 and the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge. Jose Eligio Gomez, Co-founder of Chicano Park, was quoted as saying “… we are just viewed as people who haven’t gotten out of the way of the freeways, bridges, junkyards and other industries…”

Today again Logan Heights is faced with annihilation, this time by the Maritime industry. The last remaining historic section of Barrio Logan a nine-block area from Evans to 28th Street and from Newton Street to Main Street—is the target of their desire (the area just south of Chicano Park.) The nine blocks are identified, in the Barrio Logan Community Plan, as a buffer zone between heavy industry and community residents to protect the residents against toxic pollutants emitted into the air from Maritime industries.

After a five-year democratic process that included residents and industry representatives, facilitated by the San Diego City Planning department, the BarrioLogan Community Plan was approved by the San Diego City Council on September 17, 2013. The Maritime Industries, including one Foreign owned company, are dictating the

fate of a Community Plan. At the last hour they suddenly decided they did not want the buffer zone. They paid to gather signatures to have the City approved plan overturned by a referendum. With their extensive resources they hired signature gathers to lie to San Diego residents stating that Maritime industry jobs would be loss and the Navy would move out of San Diego if the nine blocks identified in the BarrioLogan Community Plan were allocated as a buffer zone. In June 2014 the issued will be placed on the ballot for the residents of the entire City of San Diego to vote to overturn the San Diego City Council approved BarrioLogan Community Plan.

As a young person growing up in Logan Heights, I did not have to leave my Barrio . My mother walked to work at the last remaining fish cannery in San Diego, one of my brothers worked as a longshoreman on the docs, while another brother attended San Diego City College all except my oldest brother and father, all of my immediate family members worked and lived within a radius of a couple of miles. Logan Heights was a self contained neighborhood, with our own cinemas, panaderías,tortillerías,carnecerías,churches, restaurants, dance halls, cantinas,and the beloved Neighborhood House where I took dance classes from Sr. Alberto Flores, attended cultural events with my parents and played with my friends from school. The Neighborhood House, now recognized as the Logan Heights Family Health Center, located at 1809 National Ave. was our community cultural, recreational and social service center.

With the intrusion of Interstate 5 and the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge we lost many friends and relatives with the mandatory eminent domain policy that allowed the City/State to take homes and force people out of the area. Not understanding our power as a community many of us thought that was just the way it was and that we had no voice in the matter. In retrospection after all these years I now understand that it was, and continues to be, the strategy of government in conjunction with corporate industry to target low-income minority community’s to do whatever they want because they assume we have no voice. That was, of course, until the powers that be decided to place a police station in the middle of our neighborhood. That definitely was the “tipping point” that turned things around for the Chicano community of San Diego. And yet here we are again with the encroachment by private industry and government in BarrioLogan as San Diego discusses the enlargement of the Convention Center, the development of a new sports stadium complex for the Chargers, and a referendum to overturn the Barrio Logan Community Plan.

Remembering the “Take-Over” of Chicano Park, I reflect on the neglect, disrespect and racism that my community has endured during my lifetime and before during my parents, my grandparents and my great-grandparents

Memories of Chicano Park Origins

life in Logan Heights. I arrive in memory to Valentine’s weekend 1970, it was my second semester at San Diego City College, I was a member of MovimientoEstudiantil ChicanosenAztlán(MEChA), working part time for the school newspaper and was about to become engaged to my high school sweetheart, who was returning home from military boot camp. MEChA had organized a two-day conference regarding social and political issues facing our community. During the conference we decided it was important that we make a statement about who we were Chicanos in Aztlán so we raised the flag of Aztlán (recognizing the mestizajeof LaRazaCósmica,the face of the Chicano/Mestizoin the center, the profile of the Indio on one side, and the profile of the Spaniard on the other side.) For me that was the defining moment in time and the precursor to my involvement in the founding of Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Steering Committee.