25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, October 16, 2025, at 7:30

Friday, October 17, 2025, at 7:30

Saturday, October 18, 2025, at 7:30

Klaus Mäkelä Conductor

Antoine Tamestit Viola

MUSIC BY HECTOR BERLIOZ

Harold in Italy, Op. 16

In the Mountains: Scenes of Melancholy, Happiness, and Joy (Adagio—Allegro)

March of the Pilgrims Singing the Evening Hymn (Allegretto)

Serenade of an Abruzzi Mountaineer to His Sweetheart (Allegro assai)

Orgy of the Brigands (Allegro frenetico)

ANTOINE TAMESTIT

INTERMISSION

Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14

Dreams—Passions (Largo—Allegro agitato ed appassionato assai)

A Ball (Waltz: Allegro non troppo)

A Scene in the Country (Adagio)

March to the Scaffold (Allegretto non troppo)

Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath (Larghetto—Allegro)

These concerts are generously sponsored by Zell Family Foundation. Bank of America is the Maestro Residency Presenter. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

Newsradio 105.9 WBBM is a Media Partner for this event.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Zell Family Foundation for sponsoring these performances.

Born December 11, 1803; La Côte-Saint-André, France

Died March 8, 1869; Paris, France

At one of the first performances of his Symphonie fantastique, Hector Berlioz noticed that a man stayed behind in the empty concert hall after the ovations had ended and the musicians were packing up to go home. He was, as Berlioz recalls in his Memoirs, “a man with long hair and piercing eyes and a strange, ravaged countenance, a creature haunted by genius, a Titan among giants, whom I had never seen before, the first sight of whom stirred me to the depths.” The man stopped Berlioz in the hallway, grabbed his hand, and “uttered glowing eulogies that thrilled and moved me to the depths. It was Paganini.”

Paganini, is, of course, Italian-born Nicolò Paganini, among the first of music’s one-name sensations. In 1833, the year he met Berlioz, Paganini was one of music’s greatest celebrities, known for the almost superhuman virtuosity of his violin playing as well as his charismatic, commanding presence. He was even a successful composer, whose signature caprices for unaccompanied violin had already been transcribed by Schumann and would later be given new life by Liszt, Brahms, Rachmaninov, and Lutosławski. A few weeks after the 1833 concert, Paganini went to see Berlioz. He had a marvelous new instrument, he said—a Stradivarius viola—which he wanted to begin playing in public. Would Berlioz compose a piece for his viola? “I replied that I was more flattered than I could say,” Berlioz recalled. “But that to live up to his expectations and write a work that showed off a virtuoso such as he in a suitably brilliant light, one should be able to play the viola, which I could not.” But Paganini insisted, and even Berlioz, already one of the most powerful figures in music, found that he couldn’t say no.

What Berlioz began to envision, typically, was novel in form—a work for viola with orchestra that was neither concerto nor symphony, but, rather, a bit of each. Even though the orchestra would have a role more significant and commanding than that of mere accompanist, Berlioz was certain that “by the incomparable power of his playing, Paganini would be able to maintain the supremacy of the soloist.” But when Paganini saw an early version of the score, with so many rests in the solo

COMPOSED 1834

FIRST PERFORMANCE

November 23, 1834; Paris, France

INSTRUMENTATION

solo viola, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (1st doubling english horn), 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 cornets and 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, harp, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME 42 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

March 11 and 12, 1892, Auditorium Theatre. August Junker as soloist, Theodore Thomas conducting August 12, 1945, Ravinia Festival. Milton Preves as soloist, Pierre Monteux conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

August 9, 2003, Ravinia Festival. Kim Kashkashian as soloist, Christoph Eschenbach conducting

January 5, 7, and 10, 2012, Orchestra Hall. Lawrence Power as soloist, Sir Mark Elder conducting

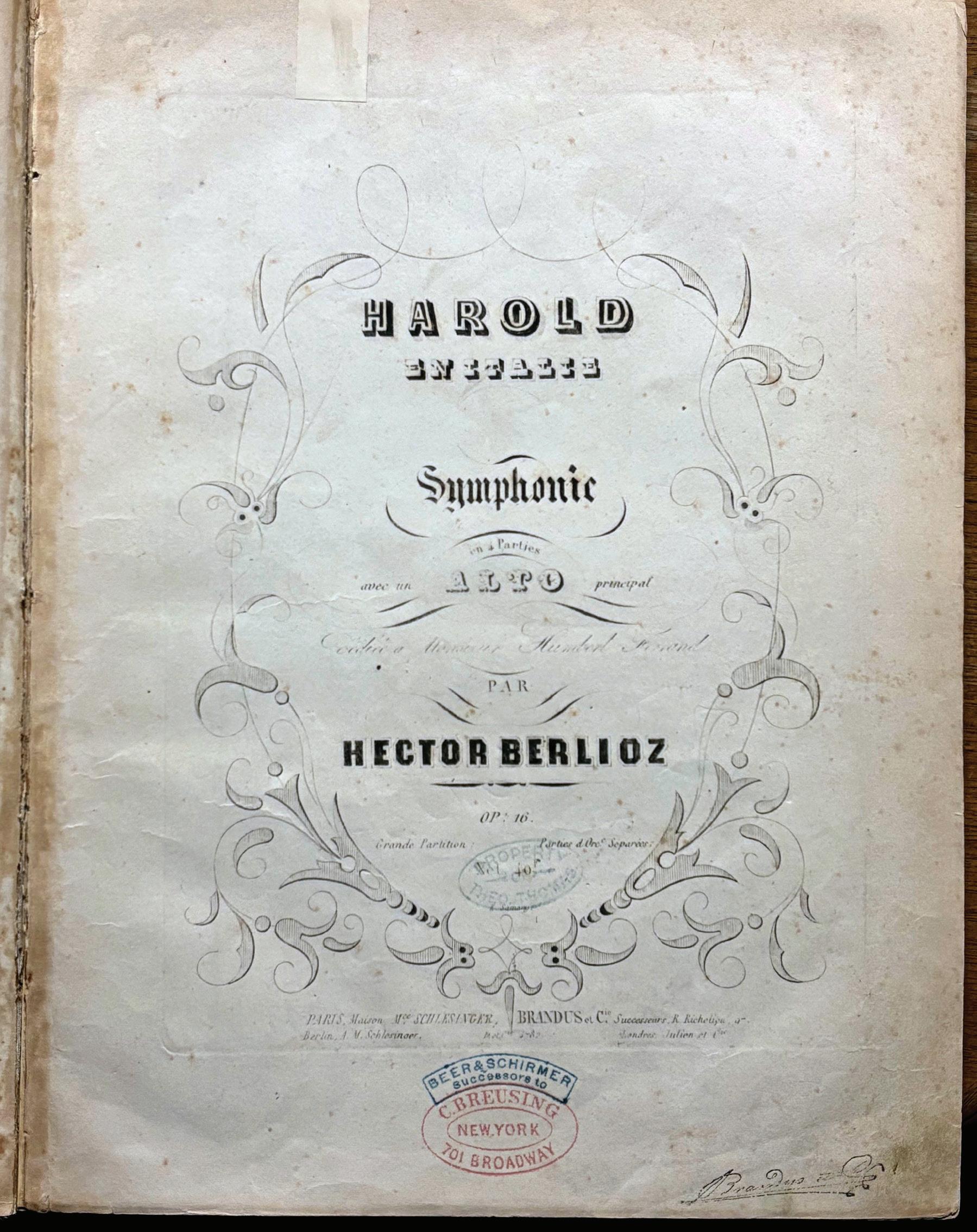

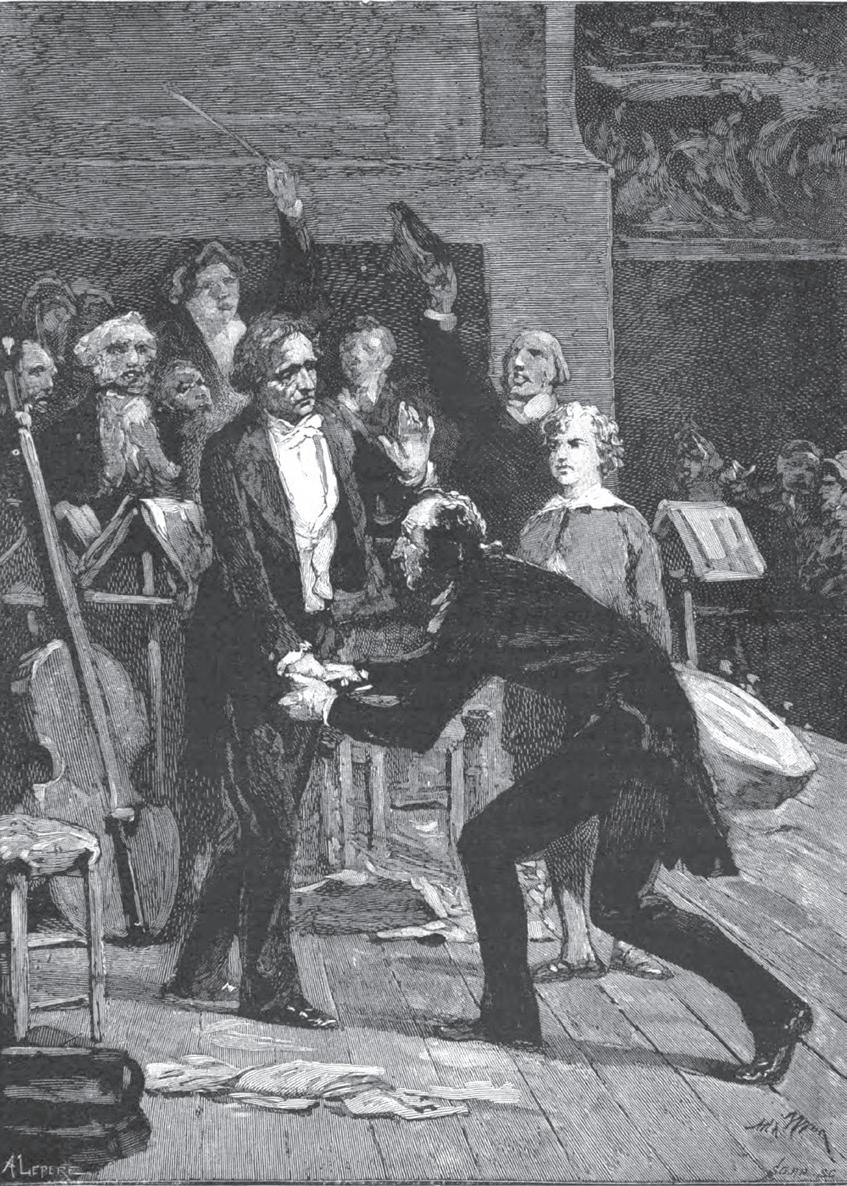

previous page: Hector Berlioz, portrait in oil, 1832, by Émile Signol (1804–1892), who won the Prix de Rome at the same time as Berlioz, in 1830. Villa Medici Collection, Rome, Italy | this page: Title page to a first edition of Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, used by Theodore Thomas—the Chicago Orchestra’s founder and first music director—for the U.S. premiere given on May 9, 1863, in New York’s Irving Hall. Theodore Thomas Collection, Rosenthal Archives | opposite page, from left: Homage of Paganini to Berlioz at the Concert of December 16, 1838. Sketch of a painting by Adolphe Yvon (1817–1893) commissioned from the artist by Édouard Alexandre (1824–1888), friend and executor to the composer, commemorating the occasion, 1884. Featured in Hector Berlioz: sa vie et ses oeuvres, the biography by Adolph Jullien (1845–1932), published 1888 | George Gordon Byron (1788–1824), Sixth Baron Byron, Poet. Lord Byron in Albanian dress, portrait in oil by Thomas Phillips (1770–1845), 1813. Government Art Collection, London, England

viola part, he said, “That’s no good. There’s not enough for me to do here. I should be playing all the time.” “What you want is a viola concerto,” Berlioz replied, “and in this case only you can write it.” Paganini did not answer, according to Berlioz: “He looked disappointed, and went away without referring to my symphonic fragment again.”

Freed from the burdens of pleasing Paganini and treating the viola like a scene-stealing, showstopper virtuoso, Berlioz returned to work on what would become one of his greatest and most ingenious compositions—“a series of orchestral scenes in which the solo viola would be involved, to a greater or lesser extent, like an actual person, retaining the same character throughout.”

As in the groundbreaking Symphonie fantastique, there is a motto theme that recurs throughout the piece; but, unlike the symphony’s idée fixe, which “keeps obtruding like an obsessive idea on scenes that are alien to it and deflects the current of the music,” the viola’s theme here is

“superimposed on the other orchestral voices so as to contrast with them in character and tempo without interrupting their development.” Berlioz began to think of the contemplative solo viola role as a kind of melancholy dreamer, in the style of Lord Byron’s wandering poetic hero Childe Harold, which gave the piece both its overall sensibilities and its title. By extension, the piece also became a reflection on Berlioz’s own happy travels through Italy, just as Byron’s Harold was partly autobiographical.

Harold in Italy, Berlioz’s new “symphony in four parts with solo viola,” was premiered in Paris in November 1834, without Paganini. The soloist was Chrétien Urhan, well-known in Parisian musical circles, but no Paganini. The conductor, Narcisse Girard, apparently wasn’t up to the challenge of Berlioz’s complex, large-scale structures, and the finale nearly fell apart. The first review was brutal. “On the morning after the appearance of this article,” Berlioz later wrote, “I received an anonymous letter in which,

after a deluge of even coarser insults, I was reproached with not being brave enough to blow out my brains!”

Despite his role in the creation of Harold in Italy, Paganini didn’t hear the piece until December 16, 1838, in a concert Berlioz conducted that also included the Symphonie fantastique. By then, Paganini had lost his voice to the disease of the larynx that would eventually kill him. He came to see Berlioz after the concert, accompanied by his young son. “My father bids me tell you, sir, that never in all his life has he been so affected by any concert,” the boy said. “Your music has overwhelmed him, and it is all he can do not to go down on his knees to thank you.” Paganini then took Berlioz by the arm and led him back onto the stage, where many of the players lingered. “There he knelt and kissed my hand,” Berlioz recalled in his Memoirs. “No need to describe my feelings: the facts speak for themselves.”

A few days later, Paganini sent Berlioz a congratulatory letter (“Beethoven being dead, only Berlioz can make him live again”) and a check for 20,000 francs, a gift that ended up paying for the composition of Berlioz’s “dramatic symphony” Romeo and Juliet. The score of that work, dedicated to Paganini, was on its way to the great performer when he died in May 1840. Although Paganini never performed Harold in Italy, the solo part was eventually played on the Stradivarius viola for which he commissioned the work, an instrument that until 1994 was in the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and now belongs to the Nippon Music Foundation in Japan.

The tale of Harold in Italy is told in four descriptively titled chapters. The first, which opens with a chromatic fugue, introduces the simple, square-cut melody that is Harold’s recurring theme. Several of the ideas in this

movement are recycled from Berlioz’s Rob Roy Overture, a remnant of his earliest plan for Harold in Italy as a work based on The Last Moments of Mary Stuart, a then-popular play running in Paris. The second movement, which, according to Berlioz, he originally improvised in a couple of hours one evening by the fire and then spent another six years fine tuning, depicts the approach and passing of a group of pilgrims.

The sound of convent bells is suggested, as Berlioz the great orchestrator boasted, by “two harp notes doubled by the flutes, oboes, and horns.” This movement was repeated, by demand, at the Paris premiere.

The Abruzzi mountaineer of the third-movement serenade sings to his beloved with the voice of an english horn, in a tune that is eventually combined with the viola’s theme. With a flair for language matched only by his gift for descriptive music, Berlioz described the orgiastic finale as a movement

. . . where wine, blood, joy, and rage mingle in mutual intoxication and make music together, and the rhythm seems now to stumble, now to rush furiously forward, and the mouths of the brass to spew forth curses, answering prayers with blasphemy, and [the brigands] laugh and swill and strike, smash, kill, rape, and generally enjoy themselves.

Each of the previous three movements is recalled, as in the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, another groundbreaking work, itself less than a decade old. If Berlioz was the first—though hardly the last—composer with the nerve to imitate Beethoven’s novel masterstroke, he was also the rare genius with the brilliance, imagination, and panache to pull it off. Harold makes one last, quiet cameo appearance before the symphony’s riotous conclusion.

“I come now to the supreme drama of my life,” Berlioz wrote in his Memoirs at the beginning of the chapter in which he discovers Shakespeare and the young Irish actress Harriet Smithson. “Shakespeare, coming up on me unawares, struck me like a thunderbolt,” he wrote after attending Hamlet, given in English—a language

Berlioz did not speak—at the Odéon Theater on September 11, 1827. But it was Smithson appearing as Ophelia, and then four days later as Juliet, who captured his heart and set in motion one of the grandest creative outbursts in romantic art.

Berlioz began the Symphonie fantastique almost at once, and it immediately became a consuming passion. Throughout its composition, he was obsessed with Henriette, the familiar French name for her he had begun to use, even though they wouldn’t meet until long after the work was finished. On April 16, 1830, he wrote to his friend Humbert Ferrand that he had “just written the last note” of his new symphony, one of the most shockingly modern works in the repertoire and surely the most astonishing first symphony any composer has given us. “Here is its subject,” he continued, “which will be published in a program and distributed in the hall on the day of the concert.” Then follows the sketch of a story as famous as any in the history of music: the tale of a man who falls desperately in love with a woman who embodies all he is seeking; is tormented by recurring thoughts of her, and, in a fit of despair, poisons himself with opium; and, finally, in a horrible narcotic vision, dreams that he is condemned to death and witnesses his own execution.

Berlioz knew audiences well; he provided a title for each of his five movements and wrote a detailed program note to tell the story behind the music. A few days before the premiere, Berlioz’s full-scale program was printed in the Revue musicale, and, for the performance on December 5, 1830, two thousand copies of a leaflet containing the same narrative were distributed in the concert hall, according to Felix Mendelssohn, who would remember that night for the rest of his life because

this page: Hector Berlioz, a pencil drawing by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), 1824. Florence, Italy. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images | next page: Oil portrait of Harriet Smithson (1800–1854), actress and wife of the composer, by Claude-Marie Dubufe (1790–1864), 1830. Musée Magnin, Dijon, France

COMPOSED

January–April 1830

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 5, 1830; Paris, France

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling english horn), 2 clarinets (2nd doubling E-flat clarinet), 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets and 2 cornets, 3 trombones, 2 ophicleides (traditionally played by tubas), timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, low-pitched bells, 2 harps, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME

49 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

December 2 and 3, 1892, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

July 20, 1943, Ravinia Festival. Efrem Kurtz conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

March 4, 5, and 8, 2022, Orchestra Hall. Paavo Järvi conducting

August 18, 2024, Ravinia Festival. Jonathan Rush conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1972. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1983. Claudio Abbado conducting. Deutsche Grammophon

1992. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1995. Daniel Barenboim conducting. Teldec

2010. Riccardo Muti conducting. CSO Resound

he was so shaken by the music. No one was unmoved. It is hard to know which provoked the greater response—Berlioz’s radical music or its bold story. For Berlioz, who always believed in the bond between music and ideas, the two were inseparable. In an often-quoted footnote to the program as it was published with the score in 1845, he insisted that “the distribution of this program to the audience, at concerts where this symphony is to be performed, is indispensable for a complete understanding of the dramatic outline of the work.” [Berlioz’s program note appears on page 9 of our book.]

Even in 1830, the fuss over the program couldn’t disguise the daring of the music. Berlioz’s new symphony sounded like no other music yet written. Its hallmarks can be quickly listed: five movements, each with its own title (as in Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony), and the use of a signature motif, the idée fixe representing Harriet Smithson that recurs in each movement and is transformed dramatically at the end. But there is no precedent in music—just three years after the death of Beethoven—for his staggeringly inventive use of the orchestra, creating entirely new sounds with the same instruments that had been playing together for years; for the bold, unexpected harmonies; and for melodies that are still, to this day, unlike anyone else’s. There isn’t a page of this score that doesn’t contain something distinctive and surprising. Some of it can be explained—Berlioz developed his idiosyncratic sense of harmony, for example, not at the piano, since he never learned to play more than a few basic chords, but by improvising on the guitar. But explanation doesn’t diminish our astonishment.

None of this was lost on Berlioz’s colleagues. According to Jacques Barzun, the composer’s biographer, one can date Berlioz’s “unremitting influence on nineteenth-century composers” from the date of the first performance of the Symphonie fantastique. In a famous essay on Berlioz, Robert Schumann relished the work’s novelty; remembering how, as a child, he loved turning music upside down to find strange new patterns before his eyes, Schumann commented that “right side up, this symphony resembled such inverted music.” He was, at first, dumbfounded, but “at last struck with wonderment.” Mendelssohn was confused, and perhaps disappointed: “He is really a cultured, agreeable man and yet he composes so very badly,” he wrote in a letter to his mother. For Liszt, who attended the premiere—he was just nineteen years old at the time—and took Berlioz to dinner afterwards, the only question was whether Berlioz was “merely a talented composer or a real genius. For us,” he concluded, “there can be no doubt.” (He sided with genius.) When Wagner called the Symphonie fantastique “a work that would have made Beethoven smile,” he was probably right. But he continued: “The first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony would seem an act of pure kindness to me after the Symphonie fantastique.”

In fact, it was Berlioz’s discovery of Beethoven that prompted him to write symphonies in the first place. At the same time, Berlioz also seems to foreshadow Mahler, for whom a symphony meant “the building up of a world, using every available technical means.” The Symphonie fantastique did, for its time, stretch the definition of the symphony to the limit. But it didn’t shatter the model set by Beethoven. For it was

The author imagines that a young musician, afflicted with that moral disease that a well-known writer calls the vague des passions, sees for the first time a woman who embodies all the charms of the ideal being he has imagined in his dreams, and he falls desperately in love with her. Through an odd whim, whenever the beloved image appears before the mind’s eye of the artist, it is linked with a musical thought whose character, passionate but at the same time noble and shy, he finds similar to the one he attributes to his beloved.

This melodic image and the model it reflects pursue him incessantly like a double idée fixe. That is the reason for the constant appearance, in every movement of the symphony, of the melody that begins the first Allegro. The passage from this state of melancholy reverie, interrupted by a few fits of groundless joy, to one of frenzied passion, with its gestures of fury, of jealousy, its return of tenderness, its tears, its religious consolations—this is the subject of the first movement.

The artist finds himself in the most varied situations—in the midst of the tumult of a party, in the peaceful contemplation of the beauties of nature; but everywhere, in town, in the country, the beloved image appears before him and disturbs his peace of mind.

Finding himself one evening in the country, he hears in the distance two shepherds piping a ranz des vaches in dialogue. This pastoral duet, the scenery, the quiet rustling of the trees gently brushed by the wind, the hopes he has recently found some reason to entertain— all concur in affording his heart an unaccustomed calm, and in giving a more cheerful color to his ideas. He reflects upon his isolation; he hopes that his loneliness will soon be over.—But what if she were deceiving him!— This mingling of hope and fear, these ideas of happiness disturbed by black presentiments, form the subject of the Adagio. At the end, one of the shepherds again takes up the ranz des vaches; the other no longer replies.— Distant sound of thunder—loneliness—silence.

Convinced that his love is unappreciated, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of the narcotic, too weak to kill him, plunges him into a sleep accompanied by the most horrible visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned and led to the scaffold, and that he is witnessing his own execution. The procession moves forward to the sounds of a march that is now somber and fierce, now brilliant and solemn, in which the muffled noise of heavy steps gives way without transition to the noisiest clamor. At the end of the march, the first four measures of the idée fixe reappear, like a last thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow.

He sees himself at the sabbath, in the midst of a frightful troop of ghosts, sorcerers, monsters of every kind, come together for his funeral. Strange noises, groans, bursts of laughter, distant cries which other cries seem to answer. The beloved melody appears again, but it has lost its character of nobility and shyness; it is no more than a dance tune, mean, trivial, and grotesque: it is she, coming to join the sabbath.—A roar of joy at her arrival.—She takes part in the devilish orgy.—Funeral knell, burlesque parody of the Dies irae [a hymn previously sung in the funeral rites of the Catholic Church], sabbath round-dance. The sabbath round and the Dies irae are combined.

a conscious effort on Berlioz’s part to tell his fantastic tale in a way that Beethoven would have understood and to put even his most outrageous ideas into the enduring framework of the classical symphony.

At the premiere, Berlioz himself was onstage— playing in the percussion section, as he often liked to do—to witness the audience cheering and stomping in excitement at the end. Later, in his Memoirs, he admitted that the performance

was far from perfect—“it hardly could be, with works of such difficulty and after only two rehearsals”—but that night he knew that he had the public in his camp, and that with the recent, coveted Prix de Rome under his belt, his career was about to skyrocket.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

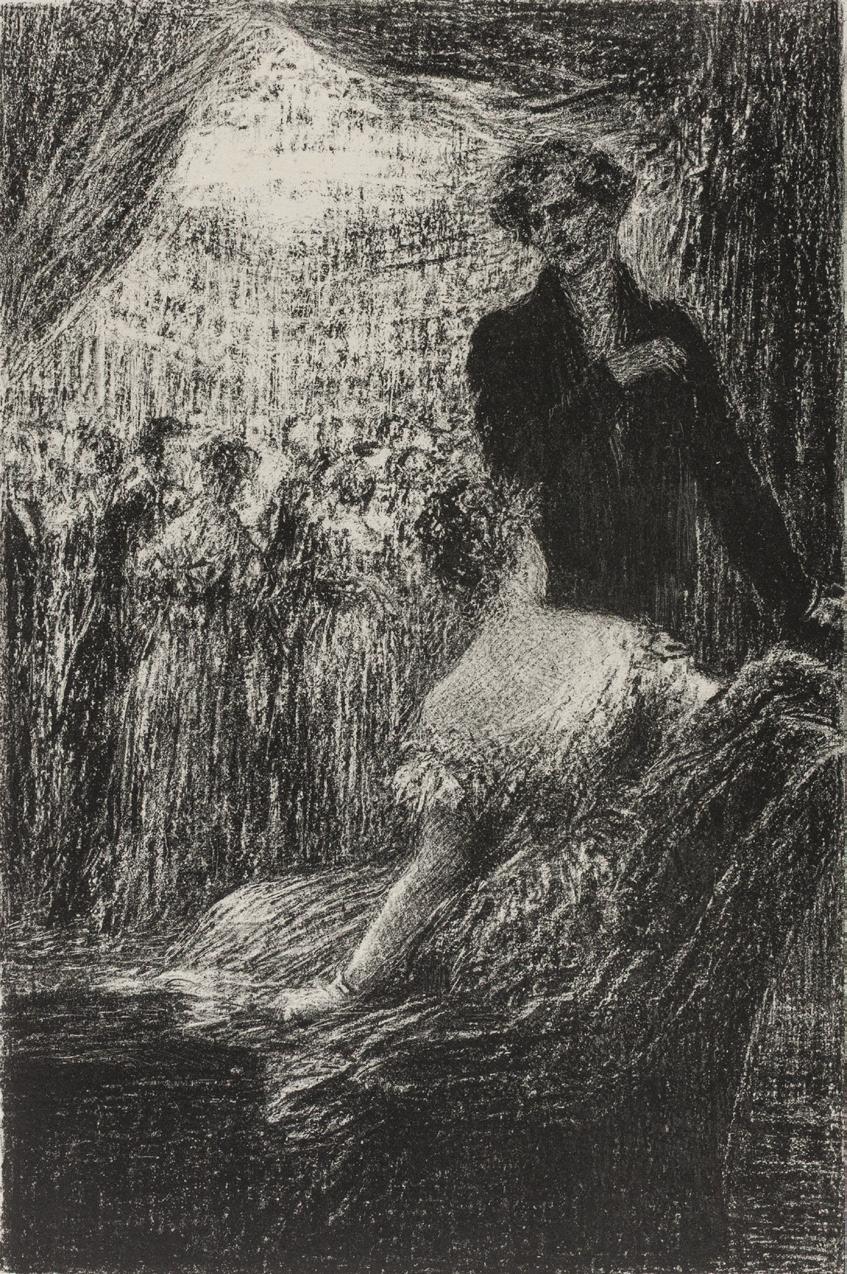

Shortly after Berlioz’s death in 1869, his reputation began to rise steadily; within a decade, his pioneering and once divisive works were performed regularly, particularly in Paris. In 1888, the first full-scale, richly documented study of his life and music was published by the critic Adolphe Jullien, one of Berlioz’s greatest defenders: Hector Berlioz: sa vie et ses oeuvres. The first edition included fourteen lithographs by Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), who spent much of his career documenting those in his Parisian circle of artists—Fantin-Latour was a close friend of Édouard Manet and great music lover who had even traveled to Bayreuth for the first Wagner Festival in 1876. His set of Berlioz lithographs, included in the Jullien biography as separate pages, are among the treasures of nineteenth-century musical illustration. Here, in one of his prints from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Fantin-Latour captures a moment in the second movement of Symphonie fantastique, where the composer is drawn to his beloved against the backdrop of dancing couples.

—P.H.

Fantin-Latour

French, 1836–1904

Symphonie fantastique: A Ball, 1888

Lithograph on paper

The Charles Deering Collection, 1927.2967

Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association is grateful to Bank of America for its generous support as the Maestro Residency Presenter.

Klaus Mäkelä

Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä has been chief conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic since 2020 and music director of the Orchestre de Paris since 2021. He assumes the title of chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam in September 2027 and, in the same season, begins his tenure as Zell Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

An exclusive Decca Classics artist, Mäkelä has released three albums with the Orchestre de Paris, including Ballets Russes scores by Stravinsky and Debussy, as well as Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Ravel’s La valse. With the Oslo Philharmonic, he has recorded Sibelius’s symphonies, Sibelius’s Violin Concerto and Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto no. 1 with Janine Jansen, and Shostakovich’s symphonies nos. 4, 5, and 6.

With the Oslo Philharmonic, Klaus Mäkelä opened the 2025–26 season with Mahler’s Symphony no. 7 and closes with Magnus Lindberg’s 1985 tour de force, Kraft. Additional highlights include a January tour and residencies in Hamburg, Vienna, Paris, and Essen, with performances of Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 8, Sibelius’s Lemminkäinen Suite, and the violin

concertos by Tchaikovsky and Sibelius with soloist Lisa Batiashvili.

Mäkelä’s fifth season with the Orchestre de Paris features wide-ranging programs, from Beethoven’s Missa solemnis to Pascal Dusapin’s opera oratorio Antigone. With a continued focus on French repertoire and contemporary music, they also perform Bizet’s Symphony in C and Franck’s Symphony in D minor, as well as new works by Guillaume Connesson, Joan Tower, Anders Hillborg, Ellen Reid, and Sauli Zinovjev.

His performances at the 2025 BBC Proms and Salzburg Festival with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra are followed by an extensive tour of South Korea and Japan in November. At home they celebrate together the fiftieth anniversary of the traditional Christmas matinee TV broadcasts and begin an annual residency at the 2026 Baden-Baden Easter Festival, taking over from the Berlin Philharmonic.

Klaus Mäkelä conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in four residencies this season and leads a U.S. tour, making his first appearance with the Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in February, performing Sibelius’s Lemminkäinen Suite and Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben. He returns to the United States in the summer of 2026 for his Ravinia Festival debut, leading the CSO in two programs. In addition, he appears as guest conductor with the Berlin Philharmonic and, as a cellist, partners with members of the Orchestre de Paris and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Mäkelä and the CSO were arguably at their best . . . a very fine performance of depth, complexity, and nuance.”

CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

Learn more about Klaus Mäkelä at cso.org/klausmakela

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

September 26, 27, and 28, 2024, Orchestra Hall. Walton’s Viola Concerto, Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider conducting

Antoine Tamestit stands as a singular voice in the world of classical music, redefining what it means to be a viola player in the twenty-first century. His unique artistry, marked by an unparalleled sensitivity and a profound connection to his instrument, places him among the most distinguished musicians of our time.

Tamestit opened the 2025–26 season at the Tanglewood Music Festival in a recital with Leonidas Kavakos, Yo-Yo Ma, and Emanuel Ax, to be followed by returns to the London Symphony Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Cleveland Orchestra, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, and Orchestre de la Suisse Romande in Geneva. Further highlights include his debut with Filarmonica della Scala in Milan and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra in Tel Aviv; chamber residencies with LSO St Luke’s and the SWR Linie 2 of the Southwest German Radio Orchestra; and the Finnish premiere of John Williams’s Viola Concerto with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra.

In recent seasons, Tamestit has performed with the Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Vienna Symphony, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, TonhalleOrchester Zürich, and the NHK Symphony Orchestra Tokyo, among many others. He performs regularly with major conductors including Sir John Eliot Gardiner, Daniel Harding, Paavo Järvi, Klaus Mäkelä, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Sir Antonio Pappano, Kirill Petrenko, Sir Simon Rattle, François-Xavier Roth, Christian Thielemann, and Jaap van Zweden.

Antoine Tamestit has premiered major contemporary works by such composers as Jörg Widmann, Thierry Escaich, Bruno Mantovani, Gérard Tamestit, and Olga Neuwirth. Recent premieres include Marko Nikodijević’s Psalmodija with the Southwest German Radio Orchestra and Francesco Filidei’s Viola Concerto with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

He was a founding member of Trio Zimmermann with Frank Peter Zimmermann and Christian Poltéra, performing in Europe’s most prestigious concert halls for more than ten years. As a chamber musician, Tamestit performs regularly with Emanuel Ax, Martin Fröst, Leonidas Kavakos, Yo-Yo Ma, Emmanuel Pahud, Yuja Wang, Shai Wosner, and the Ébène Quartet.

An ardent educator, Antoine Tamestit served for ten years as programming director of the Viola Space Festival in Tokyo, where he focused on expanding the repertoire and creating diverse educational initiatives. He previously held professorships at the Cologne University of Music and Dance and the Paris Conservatory and currently teaches at the Kronberg Academy in Germany.

Antoine Tamestit’s acclaimed discography spans a wide range of repertoire, from cornerstone works by Bach, Berlioz, and Hindemith to contemporary concertos and chamber music. His award-winning recordings feature works by Brahms, Schubert, Schoenberg, Telemann, and Widmann. Most recently, he recorded Joe Hisaishi’s newly written Viola Saga on Deutsche Grammophon.

Born in Paris, Tamestit studied with Jean Sulem, Jesse Levine, and Tabea Zimmermann. In 2022 he received the prestigious Hindemith Prize of the City of Hanau in recognition of his contribution to the contemporary landscape within classical music.

Antoine Tamestit plays the first viola made by Antonio Stradivarius in 1672, generously loaned by the Stradivari Habisreutinger Foundation in Switzerland.

Intermusica represents Antoine Tamestit worldwide.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation, Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

Olivia Jakyoung Huh Cello

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie

Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery