25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Friday, October 10, 2025, at 7:30

Edman Memorial Chapel, Wheaton College

Philippe Jordan Conductor

Augustin Hadelich Violin

KODÁLY Dances of Galánta

DVOŘÁK

Violin Concerto in A Minor, Op. 53

Allegro, ma non troppo

Adagio, ma non troppo

Finale: Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo

AUGUSTIN HADELICH

INTERMISSION

BRAHMS

Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73

Allegro non troppo

Adagio non troppo

Allegretto grazioso (Quasi andantino)

Allegro con spirito

CSO at Wheaton performances are generously sponsored by the JCS Arts, Health and Education Fund of DuPage Foundation.

Support for the CSO at Wheaton series is provided by Megan and Steve Shebik.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council. This performance is presented in partnership with Wheaton College and the Wheaton College Artist Series.

CSO at Wheaton performances are generously sponsored by the JCS Arts, Health and Education Fund of DuPage Foundation.

ZOLTÁN KODÁLY

Born December 16 1882; Kecskemét, Hungary

Died March 6, 1967; Budapest, Hungary

Galánta is a village near the road from Vienna to Budapest. (Originally part of Hungary, it now lies just over the border, in Slovakia.) When Zoltán Kodály was three years old, his father moved the family from a neighboring village to Galánta. They stayed in Galánta for seven years, and it was there that Zoltán became acquainted with music. At home his father played violin and his mother, piano; at school he and his classmates sang the songs of the Hungarian countryside. A famous gypsy band provided the first ensemble sound he ever heard. Years later, when Kodály, now a well-known composer, received a commission for a work to honor the eightieth anniversary of the Budapest Philharmonic, he remembered his time in Galánta as the happiest years of his childhood and wrote these dances. Even after his family moved from Galánta to Nagyszombat (now Trnava, in Slovakia) in 1892, Kodály’s interest in Hungarian folk music continued to grow, particularly after he teamed up with Béla Bartók in 1905. Together they began to collect and preserve the hand-me-downs of a dying musical tradition. (Nearly fifty years later, Kodály recalled their mission: “The vision of an educated Hungary, reborn from the people, rose before us. We decided to devote our lives to its realization.”)

In 1905 Kodály returned to Galánta for the first time in over a decade to track down the music of his youth. He recorded over one hundred fifty songs, a few of which were sung by his former schoolmates. “Knapsack on back and stick in hand,” he later recalled,

I set out . . . to roam the countryside without any very definite plan. Sometimes I would just buttonhole people in the street, invite them to come and have a drink, and get them to sing for me; or sometimes I would listen to the women singing as they worked at the harvest; but the most exhausting part was the nightly sessions in the smoky atmosphere of the village pubs.

COMPOSED 1933

FIRST PERFORMANCE

October 23, 1933; Budapest, Hungary

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, snare drum, triangle, glockenspiel, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 15 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

July 9, 1937, Ravinia Festival. Ernest Ansermet conducting

December 24 and 26, 1963, Orchestra Hall. Fritz Reiner conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

June 3, 4, 5, and 6, 2021, Orchestra Hall. Erina Yashima conducting August 13, 2021, Ravinia Festival. Michael Stern conducting

CSO RECORDINGS 1954. Fritz Reiner conducting. CSO (Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years) 1969. Seiji Ozawa conducting. Angel 1990. Neeme Järvi conducting. Chandos

this page : Zoltán Kodály, portrait, by Pál M. Vajda (1874–1945), 1928

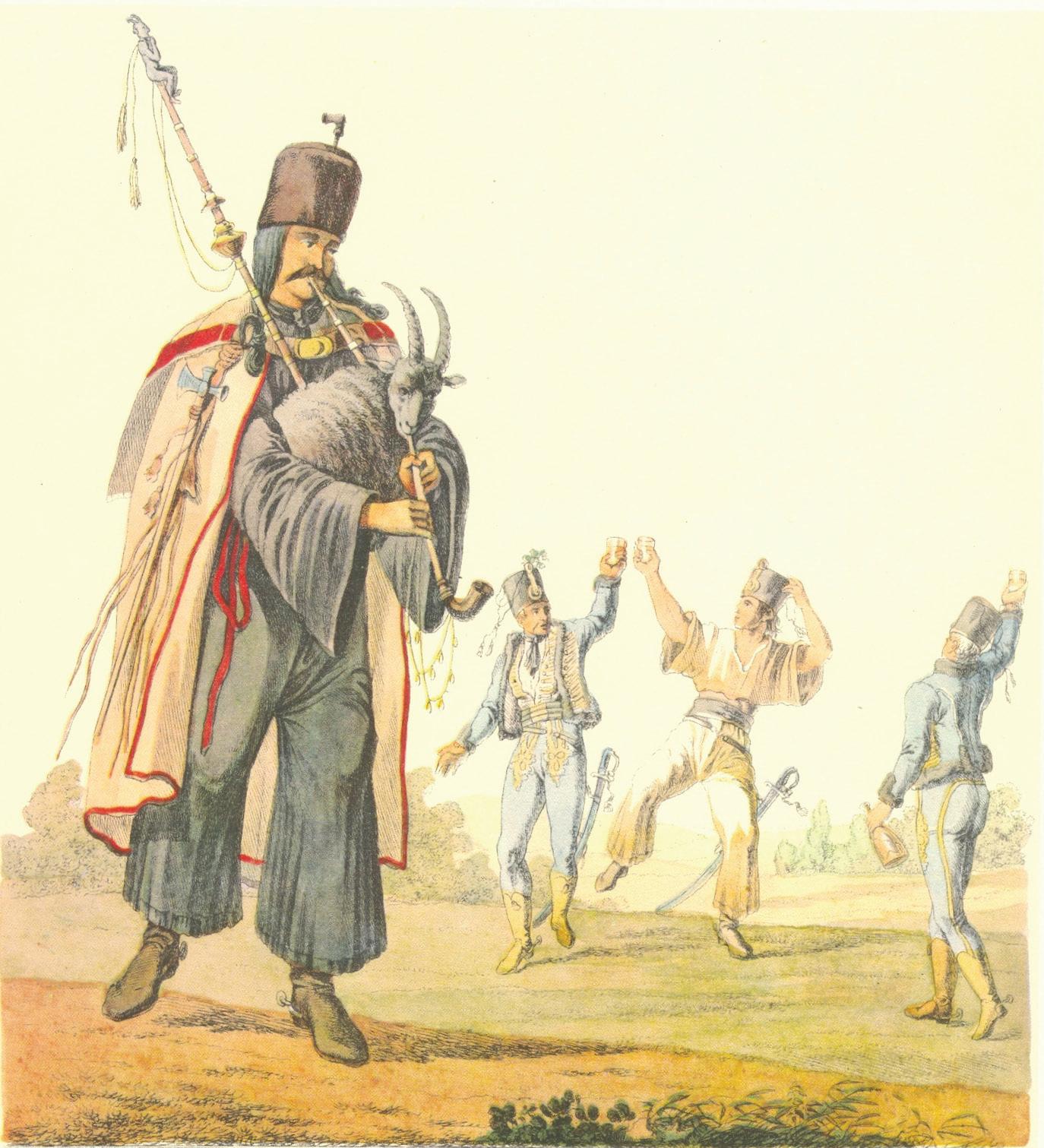

next page: József Román (1781–1800s), verbunkos bagpiper of the Thirty-Second Eszterházy Hussar Regiment. Lithograph by József Bikkessy Heinbucher (1767–1833), 1816

Kodály published his findings in his doctoral dissertation. “It is impossible to study folk songs satisfactorily,” he wrote, “particularly to investigate their rhythms, unless one hears them actually performed. Moreover, however extensive our knowledge and experience may be, it is only through hearing them sung by the peasants themselves that we can be certain as to their correct interpretation.”

Like Bartók’s earlier dance suite, Kodály’s Dances of Galánta is a continuous work in a loose rondo form (the first dance returns

after the third and during the last of the five dances). Kodály re-creates the remembered sound of the Galánta gypsy band with the resources of the full symphony orchestra. The clarinet plays a leading role, as it often does in gypsy bands, and there’s a great deal of fast, virtuosic violin music in the style of gypsy fiddling.

The music is based on the eighteenth-century verbunkos, a dance of military origin that mixed Gypsy, Turkish, and Viennese ingredients. Syncopation is prevalent, providing an irresistible rhythmic swing that differentiates this dance music from that of any other culture. Kodály had the style in his blood: what he hadn’t already absorbed he found in two volumes of dances from the Galánta region, published in 1804. Six years before the Dances of Galánta was composed, Béla Bartók wrote:

If I were to name the composer whose works are the most perfect embodiment of the Hungarian spirit, I would answer, Kodály. His work proves his faith in the Hungarian spirit. The obvious explanation is that all Kodály’s composing activity is rooted only in Hungarian soil, but the deep inner reason is his unshakable faith and trust in the constructive power and future of his people.

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

Born September 8, 1841; Mühlhausen, Bohemia (now Nelahozeves, Czech Republic)

Died May 1, 1904; Prague, Bohemia

The year the Chicago Symphony was founded, the Orchestra gave the U.S. premiere of an important new work during its third week of concerts. The program book for October 30 and 31, 1891 (exactly two weeks after the Orchestra’s inaugural concerts), lists Dvořák’s Violin Concerto as “new,” and the program annotator, like anyone writing about contemporary music, hedged his bets on Dvořák’s future reputation. Of the Bohemian composer’s recent decision to relocate to the United States, a new world he would later famously depict in a symphony, he said only, “it remains to be seen to what extent the influences of another civilization may affect his musical expression.”

Dvořák was hardly unknown at the time, even if he hadn’t yet written many of the works on which his reputation rests today, including the New World Symphony and the Cello Concerto. In fact, Theodore Thomas, the Chicago Orchestra’s founder and first music director, picked Dvořák’s Husitská Overture as the final work on the ensemble’s very first concert. And later that season, Thomas programmed more Dvořák: the Scherzo capriccioso, one of the Slavonic rhapsodies, and the D major symphony (no. 6, but then known as no. 1) that was composed the same year as the violin concerto. Dvořák’s Violin Concerto, little more than a decade old when the Orchestra introduced it, is the second of the composer’s three concertos, following one for piano written in 1876 and preceding the great cello concerto by some fifteen years.

Dvořák had learned to play the violin as a small boy, and he also composed marches and waltzes for the village band. In Zlonice, he studied piano, organ, and viola, eventually becoming a decent enough violist to earn a living as an orchestral musician when he couldn’t make any money from his compositions. After he moved to Prague in 1857, he became principal viola in the orchestra for the new Provisional Theater (later the National Theater). For the rest of his life, he treasured the memory of playing a concert there in 1863 under his idol, Richard Wagner, that included the Overture to Tannhäuser, the Prelude to Tristan and Isolde, and excerpts from Die

COMPOSED

1879, revised 1880

FIRST PERFORMANCE

October 14, 1883; Prague, Bohemia

INSTRUMENTATION

solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

31 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

October 30 and 31, 1891, Auditorium Theatre. Max Bendix as soloist, Theodore Thomas conducting (U.S. premiere)

July 27, 1971, Ravinia Festival. Itzhak Perlman as soloist, István Kertész conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 18, 2004, Ravinia Festival. Erik Schumann as soloist, Christoph Eschenbach conducting December 9, 10, and 11, 2021, Orchestra Hall. Hilary Hahn as soloist, Andrés Orozco-Estrada conducting

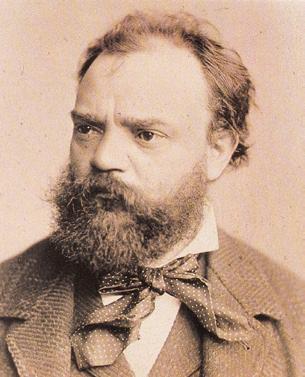

this page : Antonín Dvořák, portrait, 1882. Gallica Digital Library, Bibliothèque nationale de France

next page: Josefina Čermáková (1849–1895) with her sister Anna (1854–1931), Mrs. Dvořák, seated at the piano

Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Die Walküre. In 1871 Dvořák left the orchestra to devote more time to composition, but he soon realized that he would have to teach to get by. For many years, his father doubted the wisdom of his son’s choice of music over the life of a butcher, the family business.

Then, in 1873, Dvořák’s works began to attract attention. The successful premiere of his patriotic cantata Heirs of the White Mountain on March 9 launched his fame in his homeland. Later that year, he married Anna Čermáková, the sister of the Prague actress Josefina, who had, nearly a decade before, rebuffed his advances. (Like Mozart and Haydn, he married not his first love, but her sister.) In 1874 Dvořák took stock of his situation: he had begun to taste success; his wife was pregnant with their first child; and he looked forward to the pleasures, comforts, and traditions of family life. But he craved recognition, and he needed money. In July he entered fifteen of his newest works in a competition for the Austrian State Music Prize, a government award designed to assist struggling young artists. The judges were Johann Herbeck, the director of the Imperial Opera in Vienna; Eduard Hanslick, a man of famous, often caustic, opinions and one of the most influential critics of the nineteenth century; and, sitting on the panel for the first time, Johannes Brahms, the biggest name in Viennese music. Dvořák won the first prize

of four hundred gulden, and he felt a kind of encouragement and validation that money can’t buy. The citation praised his “genuine and original gifts” and noted, not unfairly, that he possessed “an undoubted talent, but in a way which as yet remains formless and unbridled.” (He competed and won again the next three years in a row.)

It was Brahms who introduced Dvořák to violinist-composer-conductor Joseph Joachim, who encouraged Dvořák to write a violin concerto. Joachim gave the premiere of Brahms’s Violin Concerto on the first day of 1879, shortly before Dvořák started to compose his; it was a banner year for violinists. When Dvořák sent Joachim the manuscript of his new score that November, the violinist mailed back pages of suggested improvements, and by May 9, 1880, Dvořák told his publisher that he had redone the entire concerto accordingly, “without missing a single measure.” Joachim made still further changes to his solo part—“Although the work proves that you know the violin well,” he wrote, “certain details make it clear that you have not played it yourself for some time”—and then arranged for a runthrough in Berlin in November 1882. But he never played the concerto in public; the premiere was given nearly a year later in Prague by František Ondříček. (Plans for Joachim to perform it in London in 1884 fell through.)

It’s clear from the powerhouse opening of this work that Dvořák knew and admired Brahms’s new violin concerto. (Brahms later returned the compliment: after hearing Dvořák’s Cello Concerto, he is reported to have said, “Why on earth didn’t I know that one could write a cello concerto like this? Had I known, I would have written one long ago.”) The entire first movement is serious and dramatic, and, for all its

richness of color and harmony, it’s still classical in formal outline. A short cadenza leads the way to the spacious, gloriously lyrical Adagio, nearly as long as the symphonically scaled first movement. The sparkling finale is one of the composer’s best, and the proudly Czech turn of its themes and syncopated rhythms suggest that, for all his fascination with America, Dvořák was still something of an “old world” composer.

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born May 7, 1833; Hamburg, Germany

Died April 3, 1897; Vienna, Austria

Within months after the long-awaited premiere of his First Symphony, Brahms produced another one. The two were as different as night and day—logically enough, since the first had taken two decades of struggle and soul-searching and the second was written over a summer holiday. If it truly was Beethoven’s symphonic achievement that stood in Brahms’s way for all those years, nothing seems to have stopped the flow of this new symphony in D major. Brahms had put his fears and worries behind him.

This music was composed at the picture-postcard village of Pörtschach, on the Wörthersee, where Brahms had rented two tiny rooms for his summer holiday. The rooms apparently were ideal for composition, even though the hallway was so narrow that Brahms’s piano couldn’t be moved up the stairs. “It is delightful here,” Brahms wrote to Fritz Simrock, his publisher, soon after arriving, and the new symphony bears witness to his apparent delight. Later that summer, when Brahms’s friend Theodor Billroth, an amateur musician, played through the score for the first time, he wrote to the composer at once: “It is all rippling streams, blue sky, sunshine, and cool green shadows. How beautiful

COMPOSED 1877, summer

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 30, 1877; Vienna, Austria

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME

48 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 23 and 24, 1894, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

July 10, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Hans Lange conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

August 9, 2016, Ravinia Festival. David Zinman conducting

September 21, 22, and 26, 2023, Orchestra Hall. Riccardo Muti conducting

January 8, 2025, Chodl Auditorium, Morton East High School. Lina González-Granados conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1976. James Levine conducting. RCA

1979. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1993. Daniel Barenboim conducting. Erato

it must be at Pörtschach.”

Eventually listeners began to call this Brahms’s Pastoral Symphony, again raising the comparison with Beethoven. But if Brahms’s Second Symphony has a true companion, it is the violin concerto he would write the following summer in Pörtschach—cut from the same D major cloth and reflecting the mood and even some of the thematic material of the symphony. When Brahms sent off the first movement of his new symphony to Clara Schumann, she predicted that this music would fare better with the public than the tough and stormy First, and she was right. The first performance, on December 30, 1877, in Vienna under Hans Richter, was a triumph, and the third movement had to be repeated. When Brahms conducted the second performance, in Leipzig just after the beginning of the new year, the audience was again enthusiastic. But Brahms’s real moment of glory came late in the summer of 1878, when his new symphony was a great success in his native Hamburg, where he had twice failed to win a coveted music post. Still, it would be another decade before the Honorary Freedom of Hamburg—the city’s highest honor—was given to him, and Brahms remained ambivalent about his birthplace for the rest of his life. In the meantime, the D major symphony found receptive listeners nearly everywhere it was played.

From the opening bars of the Allegro non troppo—with their bucolic horn calls and woodwind chords—we prepare for the radiant sunlight and pure skies that Billroth promised. And, with one soaring phrase from the first violins, Brahms’s great pastoral scene unfolds before us. Although another of Billroth’s letters to the composer suggests that “a happy, cheerful mood permeates the whole work,” Brahms knows that even a sunny day contains moments of darkness and doubt—moments when pastoral serenity threatens to turn tragic. It’s that underlying tension—even drama—that gives this music its remarkable character. A few details stand out: two particularly bracing passages for the three trombones in the development section, and much later, just before the coda, a wavering horn call that emerges, serene and magical. This

previous page, from top: Johannes Brahms, portrait, 1876, by Fritz Luckhardt (1833–1894). Austrian National Library, Austrian Image Archives | Fritz Simrock (1837–1901), portrait, ca. 1890, best known for publishing the works of both Brahms and Dvořák. Austrian National Library, Austrian Image Archives | this page: Pörtschach, from the eastern half of the Wörthersee. Published in the journal Die Gartenlaube, 1897, Leipzig, Germany | opposite page: Meadow with Poppies (Pörtschach), oil on canvas, attributed to Ida Kupelwieser (1870–1927), 1912

is followed, as if it were the most logical thing in the world, by a jolly bit of dance-hall waltzing before the music flickers and dies.

Eduard Hanslick, one of Brahms’s champions, thought the Adagio “more conspicuous for the development of the themes than for the worth of the themes themselves.” Hanslick wasn’t the first critic to be wrong—this movement has very little to do with development as we know it—although it’s unlike him to be so far off the mark when dealing with music by Brahms. Hanslick did notice that the third movement has the relaxed character of a serenade. It is, for all its initial grace and charm, a serenade of some complexity, with two frolicsome presto passages (smartly disguising the main theme) and a wealth of shifting accents.

The finale is jubilant and electrifying; the clouds seem to disappear after the hushed

opening bars, and the music blazes forward, almost unchecked, to the very end. For all Brahms’s concern about measuring up to Beethoven, he seldom mentioned his admiration for Haydn and his ineffable high spirits, but that’s who Brahms most resembles here. There is, of course, the great orchestral roar of triumph that always suggests Beethoven. But many moments are pure Brahms, like the ecstatic clarinet solo that rises above the bustle only minutes into the movement, or the warm and striding theme in the strings that immediately follows. The extraordinary brilliance of the final bars—as unbridled an outburst as any in Brahms—was not lost on his great admirer, Antonín Dvořák, when he wrote his Carnival Overture.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Megan and Steve Shebik for supporting the CSO at Wheaton series.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

March 1, 2, and 3, 2007, Orchestra Hall. Fauré’s Suite from Pelleas and Melisande, Ravel’s Shéhérazade with Susan Graham, and Franck’s Symphony in D minor

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES

November 16, 18, and 19, 2023, Orchestra Hall; November 17, 2023, Edman Memorial Chapel, Wheaton College. Mussorgsky’s St. John’s Night on the Bare Mountain, Szymanowski’s Violin Concerto no. 2 with Leonidas Kavakos, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring

Hailing from an artistic Swiss family, Philippe Jordan is considered one of the most distinguished and established conductors of his generation. His international career has taken him to the leading opera houses, festivals, and concert halls around the world. Beginning with the 2027–28 season, he becomes music director of the Orchestre National de France. Jordan served as music director of the Vienna State Opera from September 2020 until June 2025, leading numerous new productions, including Madama Butterfly, Parsifal, Macbeth, Le nozze di Figaro, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Tristan and Isolde, Salome, and Il trittico. He placed special artistic emphasis on a new cycle of the Mozart–Da Ponte trilogy. In his final season, 2024–25, he conducted new productions of Don Carlo and Tannhäuser, as well as revivals of the cycle of Mozart’s works and Wagner’s Ring cycle. In the summer of 2025, he returned to the Salzburg Festival to conduct Macbeth.

In the 2025–26 season Jordan conducts Der Rosenkavalier with the Vienna State Opera on tour in Japan. Additional concert engagements take him to the Orchestre National de France, Opéra de Paris, Teatro alla Scala in Milan,

Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Staatskapelle Dresden, Orchestre Philharmonique de MonteCarlo, Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra of the Region of Valencia, and the San Francisco and Atlanta symphony orchestras. In Asia, he guest conducts the Seoul and Hong Kong philharmonics and the NHK Symphony Orchestra Tokyo.

Jordan’s artistic journey began as kapellmeister at the Theater Ulm and the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin. From 2001 to 2004, he was principal conductor of the Graz Opera and the Graz Philharmonic Orchestra, at which time he also debuted at the Metropolitan Opera in New York; the Royal Opera House in London; Teatro alla Scala; the Bavarian and Vienna state operas; Festspielhaus Baden-Baden; and the festivals in Aix-en-Provence, Glyndebourne, and Salzburg. From 2006 to 2010, he was principal guest conductor of the Berlin State Opera. He made his Bayreuth Festival debut in 2012 with Parsifal.

Philippe Jordan was music director of the Opéra de Paris from 2009 to 2021 and chief conductor of the Vienna Symphony from 2014 to 2020.

As a concert conductor, Philippe Jordan has collaborated with the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Berlin and Vienna philharmonics, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Munich Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, RAI National Symphony Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and the Orchestre National de France. The major North American orchestras include the symphonies of Boston, Seattle, St. Louis, Dallas, Detroit, and San Francisco; the Minnesota, Cleveland, and Philadelphia orchestras; and the New York and Los Angeles philharmonics.

A fundraising event presented by the League of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association, featuring Zell Music Director Designate Klaus Mäkelä and violist Antoine Tamestit.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 17

11:00 am | Guest Check-In

11:30 am | Luncheon

12:30 pm | Program

UNION LEAGUE CLUB OF CHICAGO

Presidents Hall | 65 W. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604

TICKETS $250

For event tickets and more information, visit cso.org/fallinlove.

HOSTED BY

Sarah Good, President

Sharon Mitchell, Vice President of Fundraising

Mimi Duginger and Margo Oberman, Co-Chairs

Contact Brent Taghap at taghapb@cso.org with event-related questions.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 11, 12, 13, and 14, 2015, Orchestra Hall. Mozart’s Violin Concerto no. 5, Edo de Waart conducting July 25, 2024, Ravinia Festival. Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, Marin Alsop conducting

Augustin Hadelich is one of the great violinists of our time. Known for his phenomenal technique and ravishing tone, he appears extensively on the world’s foremost concert stages. Hadelich has performed with all the major American orchestras as well as with the Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, and many other eminent ensembles.

In the 2025 summer-festivals season, he appeared with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the Tanglewood Music Festival, the Mahler Chamber Orchestra at the George Enescu Festival in Bucharest, and Orchestre de Paris at the Lucerne Festival in addition to the BBC Proms Festival in London, Aspen Music Festival, and the Grant Park Music Festival.

In the 2025–26 season, Hadelich is artistin-residence of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He also appears with the Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Houston Symphony, St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, San Diego Symphony, New World Symphony in Miami Beach, and the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa. Further invitations bring him to the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Staatskapelle Dresden, Bamberg Symphony, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Munich Philharmonic, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Festival Strings Lucerne, Accademia Nazionale di Santa

Cecilia in Rome, BBC Philharmonic, Belgian National Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, Finnish Radio Symphony, National Centre for the Performing Arts Orchestra in Beijing, Orchestre National de Lyon, and the São Paulo Symphony, among others. In April 2026 he will be artist-in-residence at the Tongyeong International Music Festival in South Korea. Recitals take him to New York, Boston, San Francisco, Seattle, Warsaw, Copenhagen, Graz, Heidelberg, Cremona, and Taipei.

Hadelich’s discography encompasses much of the violin repertoire. In 2016 he received a Grammy Award for his recording of Dutilleux’s Violin Concerto (L’Arbre des songes) with the Seattle Symphony and Ludovic Morlot. He is a Warner Classics Artist, and his most recent album, American Road Trip, with pianist Orion Weiss, released in 2024, received the 2025 Opus Klassik Award for Chamber Music Recording of the Year. Other albums include the Grammynominated Bohemian Tales, which features Dvořák’s Violin Concerto with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Jakub Hrůša (2020); the Grammy-nominated disc of Bach’s unaccompanied sonatas and partitas (2021); and Recuerdos, a Spanish-themed album featuring works by Sarasate, Tarrega, Prokofiev, and Britten (2022).

Augustin Hadelich, a dual American German citizen born in Italy to German parents, rose to fame when he won the gold medal at the 2006 International Violin Competition of Indianapolis. Further distinctions followed, including an Avery Fisher Career Grant (2009), the Borletti-Buitoni Trust Fellowship (2011), and an honorary doctorate from the University of Exeter (2017). In 2018 he was named Musical America’s Instrumentalist of the Year. Hadelich holds an artist diploma from the Juilliard School, where he studied with Joel Smirnoff, and in 2021 he was appointed to the violin faculty at the Yale School of Music. He plays a 1744 violin by Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù, the “Leduc, ex. Szeryng,” on loan from the Tarisio Trust.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation, Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

Olivia Jakyoung Huh Cello

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie

Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery