NEWS: HHS Cuts

UChicago Grants for HIV, COVID Research

PAGE 4

APRIL 16, 2025

FOURTH WEEK

VOL. 137, ISSUE 13

NEWS: HHS Cuts

UChicago Grants for HIV, COVID Research

PAGE 4

APRIL 16, 2025

FOURTH WEEK

VOL. 137, ISSUE 13

By ISAIAH GLICK | Senior News Reporter

Seven individuals affiliated with the University of Chicago—three current students and four recent graduates in the U.S. under the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program—were informed on the afternoon of April 9 that their F-1 visas under the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVIS) had been revoked by the federal government.

According to an email from Division of the Arts & Humanities Dean of Students Shea Wolfe reviewed by the Maroon, there is no specific cause known for the revocations aside from “unlawful activity,” but they were not clearly connected to pro-Palestine activities or statements.

The affected individuals became aware of this change only after the University’s Office of International Affairs (OIA) conducted an audit of their records of students on visas; the students were not notified by the U.S. government when the visas were terminated. Currently, the students and graduates are in the U.S. illegally and are

at risk of being deported, but OIA has indicated that they can either speak with an immigration attorney or leave of their own volition.

On April 7, international students at the University received an email from Nick Seamons, the executive director of OIA, stating that OIA will contact international students directly if their SEVIS status is revoked and that they should reach out if they are informed of a termination by the Departments of State or Homeland Security.

Previously, OIA had issued updated guidance to international students and faculty members regarding travel outside of the U.S., informing them that they should take caution when traveling outside of the U.S. and to reconsider nonessential travel.

“Re-entry is not a guarantee [for noncitizens] and [is] at the discretion of the U.S. government,” OIA wrote.

Additionally, OIA urged students to be aware of scammers who might use the threat of deportation to demand money.

“The U.S. government will not call you asking for money in connection with your visa or status. If you receive such a call, please hang up immediately and do not provide any personal information.”

When asked for a statement, the U.S. Department of State referred the Maroon to an April 8 press briefing, where Department Spokesperson Tammy Bruce declined to share any information on why the department had terminated the visas of at least 300 international students nationwide.

“We don’t go into the rationale for what happens with individual visas. What we can tell you is that the department revokes visas every day in order to secure our borders and to keep our community safe, and we’ll continue to do so,” Bruce said.

In a statement, the University told the Maroon it was “committed to continued deep engagement and active exchange with international students, scholars, and visitors. The University has a long history of supporting America’s position as a magnet for talented people from across the globe,

and we will continue to work to assist the members of our international community.”

The University also said that “OIA has offered to connect the affected individuals with immigration attorneys.”

UChicago Faculty Forward, the union representing non-tenure-track faculty, issued a statement criticizing the visa revocations.

“These visa revocations are just the latest in a series of authoritarian, unconstitutional, and unconscionable moves by the Trump White House to target and harass international students and immigrants, colleges and universities, people exercising their rights to freedom of speech, and other groups this administration claims are its enemies,” the statement read.

Faculty Forward urged the University to provide support for affected students, including legal advice and assistance from OIA, along with mounting “a forceful public stand against these authoritarian and chilling actions by the federal government.”

CONTINUED ON PG. 2

By ZACHARY LEITER | Senior News Reporter

UChicago Trustee Antonio Gracias (J.D. ’98) is working at the Social Security Administration (SSA) as a representative of the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency Service (DOGE), per the New York Times.

Gracias is a close friend of Elon Musk, the Tesla and SpaceX executive who now

NEWS: University Introduces New Major in Climate and Sustainable Growth

PAGE 5

serves as a senior advisor to President Donald Trump and a special government employee. Gracias campaigned with Musk in Wisconsin on March 30 at a major rally for Republican state supreme court candidate Brad Schimel.

At the rally, Gracias delivered a presentation on what he called “tremendous

GREY CITY: Reworking A Decades-Old Disciplinary System

PAGE 12

fraud” at SSA, which provides retirement and disability benefits to almost 69 million Americans and accounted for 21 percent of the federal budget in 2024.

Gracias is currently serving his first five-year term on the University of Chicago Board of Trustees, which he joined in 2021. He also serves on the board of UChicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering.

VIEWPOINTS: AI Professor

Gracias serves as a director at SpaceX and previously served as a director at Tesla from 2007 to 2021. Valor Equity Partners—where Gracias is the founder and CEO—invests in both companies, and much of Gracias’s $2.2 billion personal net worth is held in Tesla stock.

“I have worked closely with Elon for over 20 years,” Gracias wrote on X on

CONTINUED ON PG. 3

ARTS: Maroon Musings PAGE 26

“The seven UChicago-affiliated individuals are among... more than 300 enrolled at various universities who have been informed that their visas had been revoked.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

The seven UChicago-affiliated individuals are among a group of more than 300 enrolled at various universities who have been informed that their visas had been revoked for reasons ranging from traffic infractions to participation in pro-Palestine protests. Affected campuses include private institutions like Harvard University and Stanford University as well as public institutions like the University of Texas at Austin and the University of California system.

On April 8, a representative from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

confirmed to Illinois Public Media News that several of its international students had their visas revoked. Students at Northwestern University and Southern Illinois University have also had their visas revoked in the past week.

Last month, several students, including Mahmoud Khalil at Columbia University, Rümeysa Öztürk at Tufts University, and Momodou Taal at Cornell University, were detained by immigration enforcement or targeted for deportation following their public statements or alleged participation in activism related to the Israel–Hamas war.

Additionally, Citizenship and Immigration Services announced that it would begin monitoring social media feeds for evidence of antisemitic activity as grounds to deny benefit requests to immigrants.

This is a developing story. We ask anyone who has knowledge of visa revocations or other immigration-related issues to please contact us at editor@chicagomaroon.com or to submit a tip through the tip form on our website. The Maroon protects source information, and your name and contact information will only be seen by the paper’s editors-in-chief and managing editor.

Evgenia Anastasakos and Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon contributed reporting.

The U.S. Department of State building in Washington, D.C. zachary leiter

By AARYAN KUMAR | Senior News Reporter

The UChicago Office of International Affairs (OIA) updated its international travel guidance following changes to immigration policy by the Trump administration. The new guidelines were announced in an April 4 email from University leadership and through the OIA newsletter.

Interim Dean of Students in the University Mike Hayes and OIA Executive Director Nick Seamons urged noncitizen students, faculty and staff—regardless of their residency status—to take caution when traveling outside of the U.S. and to reconsider nonessential travel. “Re-entry is not a guarantee and [is] at the discretion of the U.S. government,” OIA stated in the travel guidance document.

Several peer institutions, including Brown University and Columbia University, have shared similar statements cautioning noncitizen community members against international travel.

Last month, Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed to reporters that he had canceled the visas of more than 300 international students who had joined pro-Palestinian demonstrations. The White House has cited the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which allows the Secretary of

State to deport any noncitizen whose presence or activities the secretary determines have “potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.” Legal scholars have contested the White House’s application of the law.

Prior to international travel, noncitizens should ensure their passports are valid six months into the future and carry proper immigration forms and relevant visa stamps, OIA advised.

According to the updated guidance, international noncitizen travelers should reenter the United States during business hours in Chicago and notify a trusted individual when their flight lands, when they approach customs, and when they are past customs. If the trusted individual is not notified of the final step, the individual should be prepared to contact an immigration attorney and the traveler’s family and have access to a copy of the traveler’s documentation.

OIA also advised individuals on trips “related to official University programs, events, activities, or funded by University resources” to continue registering their travel with UChicago Traveler—the University’s international travel management

portal—so that the “University can provide support in case of emergencies or crises.”

OIA also recommended that travelers be mindful of the content on their devices, which can be subject to search when reentering the United States, and their social media presence. In recent months, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has used more aggressive tactics to scrutinize visa holders and tourists seeking entry to the United States.

Immigration officials deported Rasha Alawieh, an assistant professor at Brown University and a Lebanese citizen, after CBP discovered “sympathetic photos and videos” on her cell phone taken during the funeral of former Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.

Philippe Baptiste, France’s minister of higher education and research, alleged that a French researcher was denied entry to the United States over personal opinions the researcher expressed towards President Donald Trump in texts. The Department of Homeland Security has denied this allegation.

In an April 7 follow-up email, OIA warned international students of scammers that may attempt to impersonate federal agents, demanding money and threatening visa cancellation. OIA will

notify any students whose status has been terminated, OIA said.

OIA’s travel guidance document also anticipates further travel restrictions based on an executive order signed by Trump. On March 14, the New York Times reported on a draft travel ban that would ban all entry for citizens of 11 countries, severely limit entry for citizens of 10 others, and force an additional 22 countries to improve vetting or risk a ban.

Thirty-one percent of degree-seeking students at the University are from outside of the U.S., according to the winter quarter 2025 census, though it is unclear what proportion would be directly affected by a travel ban.

1427

“I have been from D.C. to Social Security offices to the border to track [Social Security fraud] down.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

January 23. “His heart is pure, and his sole mission is to help humanity. During the darkest moments, he has shown me the path to choose courage and compassion over fear and hate.”

Both Tesla and SpaceX—and by extension Musk—receive billions of dollars in federal contracts. White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said at a press conference on February 5 that Musk would be trusted with identifying his own conflicts of interest.

Musk’s role at DOGE is unclear. Though media reports often attribute DOGE’s actions to Musk, and though Musk has attended Trump’s cabinet meetings and received Department of Defense briefings, DOGE’s official acting administrator is Amy Gleason.

Gracias’s role in the Trump administration is similarly unclear. Following his arrival at DOGE, Gracias joined the SSA alongside eight other DOGE employees.

In a February 7 interview on the AllIn podcast, co-hosted by Trump A.I. and Crypto Czar David Sacks (J.D. ’98), Gracias characterized his own role at DOGE as being “in and out a little bit and trying to help where I can, but I’m not there full-time.”

During Sunday’s Wisconsin rally, Gracias said, “I have been from D.C. to Social Security offices to the border to track [Social Security fraud] down.”

At the Wisconsin rally, Gracias displayed a graph that purported to show 2 million “New Non-Citizen Social Security Numbers Issued” for 2024. “These are non-citizens that are getting Social Security numbers,” he said. “This literally blew us away. We went [to the SSA] to find fraud and found this by accident.”

“You [only need to] show a medical bill and a school ID” to get a Social Security number, Gracias said. “From there, you get on the voter rolls, and then Dem[ocrat] operatives will farm the vote,” Musk added. While some municipalities have legalized noncitizen voting in local elections, there is no evidence of widespread voting by noncitizens in federal elections.

In meetings with senior staff, SSA Acting Commissioner Leland Dudek has referred to Gracias and other DOGE staff-

ers as “outsiders who are unfamiliar with nuances of SSA programs,” per a March 6 Washington Post article.

Despite DOGE staffers’ lack of experience, “I am receiving decisions that are made without my input. I have to effectuate those decisions,” Dudek told senior SSA staff.

Though the White House said on March 11 that the Trump administration and Elon Musk “will not cut Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid benefits,” Musk has called Social Security “the biggest Ponzi scheme of all time.”

SSA has faced repeated website crashes, long hold times, and the closure of many regional offices since Trump took office, as the Washington Post reported on March 25.

Neither DOGE nor Gracias could be reached for comment. The White House declined to comment.

When asked whether UChicago’s Board of Trustees was aware of Gracias’s role at DOGE and whether the University had any policies around Trustees’ political activities, a representative of the Board directed the Maroon to a University spokesperson.

A statement from the spokesperson did not confirm whether the Trustees know about Gracias’s role at DOGE. “The Board of Trustees [follow] the responsibilities outlined in the University of Chicago’s governing documents [and adheres] to the University’s conflict of interest policy for Trustees and Officers,” the statement read.

For Gracias, Social Security fraud is part of a broader problem.

On the All-In podcast, Gracias said that he thought more than 10 percent of the federal budget was fraud. “You’re talking about $650 billion, $1 trillion in waste,” he said.

And at the Wisconsin rally, Gracias said that because millions of undocumented immigrants were receiving Social Security, Medicaid, and other federal financial assistance, human trafficking and cartel activity were increasing rapidly.

Undocumented immigrants are generally ineligible for Medicaid and other federal benefit programs despite paying billions in federal taxes.

SSA did not respond to a request for comment.

Gracias has undergone a political transformation in the past decade. He donated to Democratic presidential primary candidates Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton in 2007 and to Obama again in 2012, per Federal Election Commission records reviewed by the Maroon.

He supported Clinton in the 2016 presidential election and gave almost $500,000 to Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden and the Democratic National Committee in the 2020 election. Both candidates ran against Trump.

In 2022, Gracias donated to Republican Senate candidate Dave McCormick (R-Pa.). In 2024, he donated millions to McCormick, Elon Musk’s pro-Trump America PAC, and the POLARIS National Security PAC, formed to “[h]elp elect conservatives to Congress who will stop

Joe Biden’s dangerous foreign policy and fight for American Greatness.”

However, Gracias also donated in 2024 to the reelection campaigns of Senator Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) and Representative Jim Himes (D-Conn.).

Musk, for his part, contributed $277 million to Trump and other Republican candidates in 2024.

The Eisenhower Executive Office Building, where DOGE is located. zachary leiter

Tiffany Li, editor-in-chief

Elena Eisenstadt, deputy editor-in-chief

Evgenia Anastasakos, managing editor

Haebin Jung, chief production officer

Crystal Li & Chichi Wang, co-chief financial officers

The Maroon Editorial Board consists of the editors-in-chief and select staff of the Maroon

NEWS

Sabrina Chang, head editor

Gabriel Kraemer, editor

Anika Krishnaswamy, editor

Peter Maheras, editor

GREY CITY

Rachel Liu, editor

Celeste Alcalay, editor

Anika Krishnaswamy, editor

VIEWPOINTS

Sofia Cavallone, co-head editor

Cherie Fernandes, co-head editor

Camille Cypher, co-head editor

ARTS

Miki Mukawa, co-head editor

Nolan Shaffer, co-head editor

SPORTS Josh Grossman, editor

Shrivas Raghavan, editor

DATA AND TECHNOLOGY

Nikhil Patel, lead developer

Austin Steinhart, lead developer

PODCASTS

Jake Zucker, co-head editor

William Kimani, co-head editor

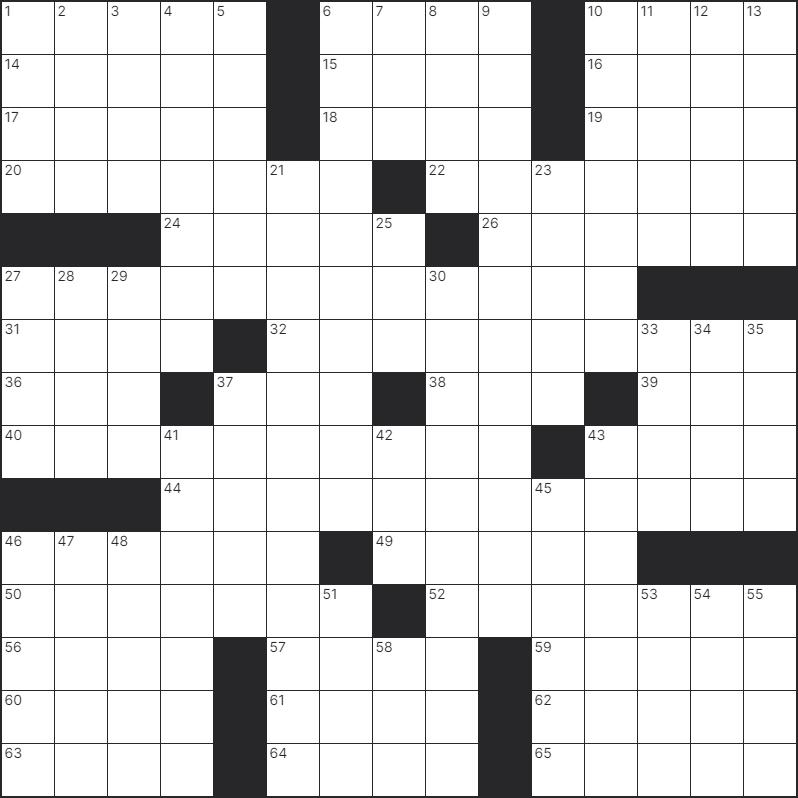

CROSSWORDS

Henry Josephson, co-head editor

Pravan Chakravarthy, co-head editor

PHOTO AND VIDEO Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon head editor

DESIGN

Eliot Aguera y Arcas, editor Kaiden Wu, editor

COPY

Coco Liu, chief Maelyn McKay, chief Natalie Earl, chief Abagail Poag, chief

Ananya Sahai, chief

Mazie Witter, chief

Megan Ha, chief

SOCIAL MEDIA

Max Fang, manager

Jayda Hobson, manager

NEWSLETTER

Amy Ma, editor

BUSINESS

Adam Zaidi, co-director of marketing Arav Saksena, co-director of marketing Maria Lua, co-director of operations Patrick Xia, co-director of operations

Executive Slate: editor@chicagomaroon.com

For advertising inquiries, please contact ads@chicagomaroon.com

Circulation: 2,500

By GRACE BEATTY | Senior News Reporter and ISAIAH GLICK | Senior News Reporter

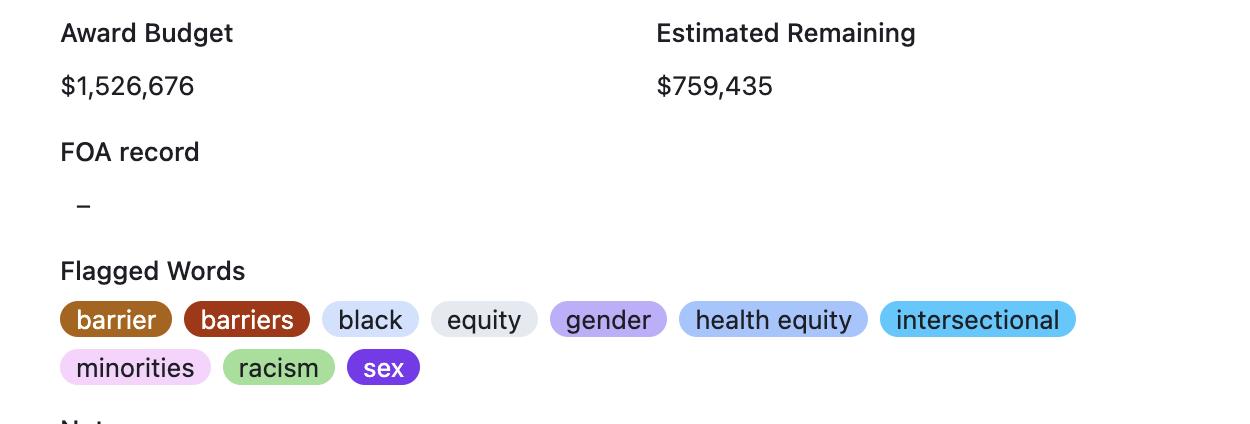

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in March terminated six National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants awarded to University of Chicago researchers, including funding for research into HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, and health inequality.

The UChicago grant terminations, which totaled nearly $6 million, are part of a growing list of terminated research grants awarded to universities, research labs, and public health systems. The move comes as the Trump administration continues to slash government research funding across the country, justifying the actions as eliminating diversity, equity, and inclusion programs and other “wasteful” government spending.

A January 20 executive order titled “Ending Radical And Wasteful Government DEI Programs And Preferencing” directed federal agencies to cancel funds that “provide or advance DEI, DEIA, or ‘environmental justice’ programs, services, or activities.”

A New York Times analysis found hundreds of words that have been “flagged” to be limited or eliminated from federal websites and other government documents. Most of the terms are related to diversity, discrimination, or inequality. According to the Times, federal workers have been told to remove the words and phrases from agency materials and in some cases to “automatically flag for review” any grant proposal containing words inconsistent with the Trump administration’s priorities.

A separate database compiled by Harvard University researchers lists grants terminated by HHS, including words in research proposals that may have been flagged.

In a statement, an NIH spokesperson told the Maroon, “NIH is taking action to terminate research funding that is not aligned with NIH and HHS priorities. We remain dedicated to restoring our agency to its tradition of upholding gold-standard, evidence-based science.”

“As we begin to Make America Healthy Again, it’s important to prioritize research that directly affects the health of Americans,” the statement read.

The NIH did not provide an explana-

tion for why individual grants were terminated or how the affected grants were inconsistent with NIH and HHS priorities to the Maroon

John Schneider, a professor of medicine and public health sciences at UChicago, is the principal investigator (PI) on a study retrospectively examining the increased risk of COVID-19 transmission and decreased access to testing and vaccination among migrant workers. Schneider’s team was initially awarded $374,670 by the NIH in March 2024, of which the remaining $99,409 was revoked on March 10, 2025.

Schneider told the Maroon that his study was unrelated to the HHS’s stated reason for its cancellation: that his research was ostensibly nonscientific and focused on diversity.

“We looked at the entire grant proposal and there was no mention of diversity throughout the entire research plan,” he said.

A grant termination letter reviewed by the Maroon informed the affected researcher, “It is the policy of NIH not to further prioritize research programs based primarily on artificial and non-scientific categories, including amorphous equity objectives, are antithetical to the scientific inquiry, do nothing to expand our knowledge of living systems, provide low returns on investment, and ultimately do not enhance health, lengthen life, or reduce illness.”

“Worse, so-called diversity, equity, and inclusion (‘DEI’) studies are often used to support unlawful discrimination on the basis of race and other protected characteristics, which harms the health of Americans. Therefore, this project is terminated,” the letter concluded.

Schneider is also the PI of a study looking into the relationship between cannabis use and HIV “acquisition, testing, and care” for young Black men. Initially awarded $2,814,152, HHS terminated nearly $400,000 in outstanding funding.

“We’re in year three of five… This is a multi-million-dollar grant,” Schneider said. “We’ve already spent about half of it, and so if we can’t complete it, that’s… wasted money, it’s wasted time, it’s wasted effort.”

Schneider intends to appeal the deci-

sion: “I know there are some great people who have appealed so far and have been successful, [but] I’m sure there’s a lot who have appealed and have not been successful.”

A coalition of public health groups, unions, and individual researchers filed suit against the NIH, HHS, and their respective agency heads on April 2 seeking to restore terminated research funding. Separately, 23 state attorneys general have also sued HHS and HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to have public health grants to their states restored.

A federal judge has since granted a temporary restraining order (TRO) in the states’ lawsuit.

In a statement, a University spokesperson told the Maroon, “The University of Chicago is dedicated to supporting our researcher community and the impactful, field-defining research produced across all academic disciplines. The Office of the Provost is working to help researchers identify potential alternative research funding sources where possible.”

Associate professor of medicine Jessica Ridgway, another PI whose study faces a grant cancellation, told the Maroon, “We have patients who were actively receiving care for their substance use, and we had to call them and tell them that we were not able to provide that care anymore and help try to find them alternative resources or places to go for their substance use treatment.”

Ridgway is the PI for a study looking into the overlapping challenges between substance use disorder (SUD) and HIV care among Black Americans, analyzing inadequate access to healthcare, stigma, and lack of engagement with care.

Her team aims to design and implement

a strategy to increase portal engagement, perform a trial to assess the effectiveness of clinic visits, and ultimately improve SUD screening and treatment among Black people living with HIV. HHS has revoked the remaining $758,813 of Ridgway’s $1.5 million grant.

Previously, on February 7, the NIH instituted a 15 percent cap on the “indirect costs” of research, which include administrative functions, maintenance costs, and utilities of buildings, for federal research grants.

After 22 state attorneys general sued the NIH to block the indirect funding cap, a federal judge issued a TRO on February 12 to prevent the cap from taking effect. UChicago concurrently filed a lawsuit with 12 other universities and several academic organizations, which also resulted in a TRO.

In a February 11 letter to UChicago faculty explaining the decision to sign on to the lawsuit, University President Paul Alivasatos wrote that the “precipitous timing of [the indirect funding cut] would immediately damage the ability of our faculty, students, and staff (and those of other academic institutions and medical centers across the nation) to engage in health-related fundamental research and to discover life-saving therapies.”

“I do think that we will find a way through this and past these funding cuts,” Ridgway said. “I think that you know people in the community and researchers that focus on people living with HIV are particularly resilient and are banding together. I think we’ll hopefully find… a way through. It is painful and disappointing right now.”

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon contributed reporting.

A screenshot of the database’s entry for associate professor Jessica Ridgway’s cancelled grant for research into the relationship between substance use disorder and HIV care for Black men. nathaniel rodwell-simon.

By ELIOT AGUERA Y ARCAS | News Reporter

The Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth will introduce a new interdisciplinary undergraduate major and minor in Climate and Sustainable Growth beginning in fall quarter 2025. Housed in the Physical Sciences Collegiate Division, the program will give students a climate-oriented foundation in economics, policy, and energy technologies.

After a sequence of seven foundational courses, students will have the option to choose between three specializations: Climate Science and Technology; Politics, Economics, and Society; or Finance.

The major owes its formulation to the same 2023 report that led to the launch of the Institute itself in October 2024. The report was composed by a faculty committee, chaired by Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor in Economics Michael Greenstone, tasked with assessing the University’s interests and obligations in the climate space. The report laid out a broad program to promote climate research and reduce institutional emissions. Greenstone now serves as the Institute’s founding director.

In his initial announcement of the Institute, University President Paul Alivisatos promised that “a number of education-based initiatives and programs will be developed to cut across many disciplines and research topics.”

The major has been in development for two years, answering what Greenstone described as “an insatiable demand” for new curricula on climate. In recent years, the University has seen an increasing number of majors in climate-related fields.

In the Division of Social Sciences, the Committee on Environment, Geography, and Urbanization (CEGU) began offering both a major and minor of the same name

in the fall of 2023, replacing the Environmental and Urban Studies major. Students majoring in public policy also have the opportunity to specialize in energy and environmental policy.

Universities around the country have similarly expanded their climate offerings. Vanderbilt University’s Climate Studies major, launched in 2022, aims to integrate coursework in the humanities and social sciences. The Columbia Climate School at Columbia University recently introduced master’s programs in Climate and Climate Finance, as well as Climate and Society.

The Climate and Sustainable Growth major proposes to take a holistic approach to climate that students might not find in a traditional curriculum. “We definitely have environmental science majors and lots of classes in law and policy fields focused on the area, but this brings all of those things together,” said Vaani Kapoor, a second-year in the College and member of the Energy and Climate Club.

Second-year Iris Badezet-Delory, a co-president of the club, explained the case for an interdisciplinary approach: “If you’re working on a technology that you think could help with the adaptation or mitigation aspect, great, but if you don’t know how to sell it to businessmen and show why it’s amazing, people are not going to invest in that.”

“If you’re not able to see the possible policy outcomes of your technology,” she continued, “it might not be widely adopted. If you’re working in finance, you’ve got to take both policy and tech considerations into mind when you’re making an investment decision. Same with public policy. Those three arenas really interconnect when you’re talking about climate and energy.”

The major will also offer opportunities to study abroad through a selection of September Term experiential courses intended to bring global perspectives into the curriculum.

Students travelling to destinations in rural India and sub-Saharan Africa will gain insight into how people live with relatively low levels of energy consumption, while others will spend the term in West Texas, where the booming oil and gas economy relies on fracking. Other groups visiting Wall Street or Washington, D.C. will have the opportunity to meet the investors and policymakers who shape decision-making surrounding climate.

In an interview with the Maroon, Greenstone said that he looks forward to students bringing the diverse understandings these experiences will provide back to the classroom. “Each of those groups are going to have very different perspectives, and what we want is students… to be able to hold those multiple competing perspectives in their head at once and try to make sense of them,” Greenstone said. “That’s what education is supposed to be. You take a bunch of complicated ideas, some of which seem to run in opposition to each other, and how do you make sense of them? How do you draw conclusions?”

Greenstone hopes that UChicago’s Climate and Sustainable Growth major will serve as a template for other institutions. “Just as the Chicago Principles for Free Expression have proved to be very influential in higher ed [and] in the world broadly, we aim for the same thing for the Chicago curriculum,” he said.

The major’s creators aim for students to emerge from the Climate and Sustainable Growth program well equipped to enter a growing niche for sustainability specialists in both the private and public sectors. Within the past five years, job prospects in

corporate sustainability have been among the fastest growing in the country, with few candidates well-trained to step into those roles, Greenstone said.

Kapoor also highlighted the major’s pathway to more specialized career areas. “It’s going to create so many more opportunities for students… to get exposure to the field and matriculate out into working in the climate space rather than just general policy or general business areas,” she said.

At the same time, Greenstone emphasized the value of the curriculum in its own right as part of a broad liberal arts education, a priority which informed its development. “The University of Chicago is not a technical school, in that the deepest aim of education is to help students learn how to learn.… By taking this multi-dimensional, multi-faceted problem and getting people to develop the muscles in their brain to be able to see this problem in all of its glory and all of its complexity and reach conclusions for what they think is the right thing—that ‘learning how to learn’ is something that time will never take away.”

In the coming years, Greenstone anticipates the curriculum adapting not only as a result of student input but also as the field itself is reshaped by developing research. “We’re in the second or third inning of the climate challenge. It’s not going away,” he said. “There are projected to be high levels of CO2 emissions out into the indefinite future. In its own way, unfortunately, climate change is a growth business.”

Beyond the new major and minor, the Institute also hopes to apply the curriculum for a master’s program through the Harris School of Public Policy. The program would become available for the 2026–27 academic year.

Student information sessions about the major are slated to take place in spring 2025.

By NATALIE EARL | Staff Photographer

cultural show on Saturday, March 29, at 8 p.m. in Mandel

The show was ac-

companied by an art display outside the hall that showcased SASA members’ visual art, poetry, and photography. Pagal Khaana: House of Madness,

a short film SASA produced, played in segments between each performance and guided the audience through the experi-

“The almost two-and-a-half hour show was high energy from beginning to end.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 5

ence of high school senior Anush (Vivek Cherian) as he struggled to embrace his family and culture. Heartfelt and witty, the film left the audience with the message that there is much to be gained through deepening our bonds with family and friends and, ultimately, culture.

Directed by Antrita Manduva, Raghav Pardasani, and Ishi Sood, the almost two-and-a-half-hour show was high energy from beginning to end, keeping the audience excited and often whooping in encouragement, laughing, or clapping along.

The official show program is quoted throughout for an accurate description of each performance.

See chicagomaroon.com for the color version of this photo essay.

SASA members’ artworks—largely focused on their cultural experiences—are displayed gallery-style outside Mandel Hall for attendees to view. natalie earl

Audience members file into Mandel Hall to find their seats for a sold-out show, with SASA reporting over 720 tickets sold.natalie earl .

Raghav Pardasani (center), and Antrita Manduva (right) welcome the audience and open the show. natalie earl

The first performers of the night, from left to right, Harsha Mandayam Bharathi (mridangam), Sammy Thiagarajan (guitar), Parjanya Tiwari (vocals), Anuraag Kaashyap (vocals), Rishabh Subramanian (vocals), and Pravan Chakravarthy (violin), bring the audience “classical music from across South Asia, including Carnatic, Hindustani, and sub-styles within these genres.” natalie earl.

Rock band AC/Desi wows the crowd with a performance of South Asian pop and rock songs. The group is composed of Amam Jain (vocals), Mridvi Khetan (vocals), Sammy Thiagarajan (guitar), Tia Khosla (keyboard), Hetav Mehta (guitar), Avyay Duggirala (bass), and Ayush Gautham (drums). natalie earl .

SASA members bring high energy to their Garba and Raas performance—traditional folk dances from Gujarat—choreographed by the Chicago Raas team. natalie earl

SASA members perform a dance choreographed by Apsara, “combin[ing] classical forms of dance—Bharatanatyam, Kathak and Kuchipudi—with Fusion music, such as Bollywood, Rap or classical South Indian.” natalie earl

SASA members leave the audience in a frenzy with their fusion dance, a “lively performance with dance styles and music from around South Asia.” natalie earl .

SASA members strut down the runway to display the diverse fashion and jewelry of South Asia. natalie earl .

Chicago Aag performs a cappella medleys of popular South Asian and American songs. The group is composed of Anuraag Kaashyap, Trayi Ajit, Eden Anne Bauer, Saumya Gondotra, Aanya Bhola, Rishabh Subramanian, Neel Maheshwari, Arnav Modak, Ishaan Goel, Grey Singh, Aria Saxena, and Parjanya Tiwari. natalie earl .

UChicago Bhangra performs Bhangra, “a folk dance, originally from Punjab, full of high energy and fast movements.” natalie earl

Class of 2025 SASA members—dressed in blue jeans and white tees—take up the stage in the final photo of the night. natalie earl.

By GABRIEL KRAEMER | News Editor

Heidi Heitkamp, the outgoing director of the Institute of Politics (IOP), sat down with the Maroon last month to discuss her tenure as director, challenges the IOP faces going forward, and her future plans.

The former U.S. senator has led the IOP since January 2023. The IOP announced in January that Heitkamp will step down later this year following a “global search” for her replacement. She will stay on as a member of the IOP’s board of advisors after her departure.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Chicago Maroon (CM): What do you see as your major accomplishments as IOP director?

Heidi Heitkamp (HH): In this transition between a founder—David [Axelrod]—and thinking broadly about what the next 10 years of the IOP look like, I think we set it on a good trajectory. The one thing that I would say that I’m probably most proud of is I think we’ve increased the collaboration across programs…. Before I came here, the place was pretty siloed. By that I mean, civic engagement did their thing, career development did their thing, speakers did their thing, [Pritzker] Fellows did their thing.

What we’ve really tried to do with the staff is say, “Look, we’re student-facing.” We have to look at a student who is thinking: “I want to be an ambassador for a fellow who works in climate.” How can we help that same student find an internship in climate? How can we find an opportunity for them to engage in the community in a way that helps them build their climate resume? So to me, [one of my major accomplishments at the IOP has been] the collaboration across the various groups that we operate.

The second thing is broadening the scope of [the IOP’s] Bridging the Divide [initiative]. As we have seen more and more political discourse becoming very siloed, very, very rancorous, [we aim] to try and figure out how we can engage students in ways that give them the skills to engage in respectful dialogue. And so

[with] Bridging the Divide, we did our big conference on urban–rural [division]. Now, with [the] Divided We Stand [initiative], we’re looking not just at urban-rural divisions but gender divisions, cultural divisions, religious divisions.

David [Axelrod] ran Bridging the Divide, but it was a much more contained program. It involved taking 15 students and having them engage across with other universities, other campuses. My feeling was that those 15 students could have gotten a great advantage, but in this time of polarization… broadening Bridging the Divide is responsive to the times we’re in.

A lot of this, to be fair, has been driven by our student advisory groups. My goal coming here was to maintain, if not increase, student-facing reaction. By that I mean the ability of students to come here and say, “This is more of what we need from the IOP.” We’ve always been student-facing, but I think we’ve really tried to make it much more about our students.

CM: The University’s financial issues have been under the spotlight for much of your time as director. How have those concerns affected programming at the IOP, if at all?

HH: This has been a difficult time because of the University budget concerns.… We haven’t been able to hire because of] the hiring freeze, [so] people have been doing double time. We used to do a lot of programming that involved students being able to get subsidized trips; I don’t think we’re as robust [as we used to be] in that area.

The one thing that I would say that I have refused to do, that I think other programs have, is eliminate any of our internships. I think there’s some programs that have gotten rid of their academic-year internships—it means that our applications tripled. And so, to me, [eliminating internships] is a nonstarter.

CM: How do you see the Trump administration’s cuts to the federal government affecting the IOP and similar institutions at other universities?

HH: There’s been plenty of students who want to work in this administration. But we’re seeing more students wanting

to have an internship experience that is outside of government, and I think that’s good. Looking at state and local [government] is an important recalibration, because I think way too often students think that the only experience that’s worthwhile is in Washington, D.C., and I disagree with that. If I compared my internship in D.C. that I did when I was a junior in college with my internship at the North Dakota legislature, the North Dakota legislature had a much greater impact on how I thought about my role. I ended up being a state official, and I’m not sure I would have done that without that experience in the state legislature.

So what I would say is that it has now broadened our thinking about how we do more hometown internships, which is a favorite program of mine. How do we be responsive in the moment? And then how do we become a place for dialogue for students who are concerned?… There’s just a lot of students on campus who haven’t been all that interested in politics and now are approaching our student leaders because all of a sudden they’re not going to get into a Ph.D. program because [the National Institutes of Health’s] money has dried up. And so, I think it’s a real opportunity to bring non-traditional students to the IOP who now realize the impact of government decisions on a much broader swath of America.

So, we’re looking for the opportunities: the opportunities to build state and local leadership experiences, internship experiences; the opportunity to have programming for students who would not otherwise have an interest in politics that now are saying, “Whoa whoa whoa, I guess this could affect me”; and an opportunity for reflection for a lot of students on how this vote happened.

And then one thing that we’re deeply concerned about is the future of science. That’s one thing I’m very excited about and will stay engaged and involved in, which is this political intersection between science and scientific discovery and politics. That’s a role we can play at a university that’s a major research university.

CM: Could you talk a bit about what happened during pro-Palestine protesters’ occupation of the IOP last year?

HH: I was right here, actually, doing

Heidi Heitkamp began her tenure as IOP director on January 3, 2023. courtesy of s christopher gillett

a hit with ABC. I’m an ABC contributor. I wasn’t on air yet—I was waiting to go on air. And the door burst open because I always keep the door shut when I’m doing this. I had heard the protesters come down.… I thought, maybe they’ll move on so that background noise won’t be there. And all of a sudden, the door burst open, and three masked protesters came in the door. The first thing they said is, “You have to leave.” They clearly did not want me in this building. And I said, “No, I don’t think I do.” And then in the meantime, ABC is like, “What’s going on?” So I kept saying, “Just let me do the ABC hit. Let me do the ABC hit, and we can talk about this.” And they were not having any of that.

Eventually I just said, “I’m not leaving.” And they said, “Well, you know, you’re going to get hurt.” And I said, “Who’s going to hurt me?” It was not well thought out on their part in terms of how they were going to occupy this building. The only time that I got irritated is when I heard them throwing furniture because I thought, “You don’t need to do that.”

But we had a great conversation about why they were in this building. I never really did understand [why], and I wanted to say, this is a place where— well, I wouldn’t say it’s First Amendment hallowed ground; that’s a little grandiose—but it is a place where we want to be respectful of all opinions. And it was our feeling that, to maintain that obligation we have on this campus, we can’t just simply capitulate; we have to engage.

CONTINUED ON PG. 8

“We... want to expose students to a whole different way of thinking about how they can engage civically, rather than just traditional political engagement.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 7

And so that’s what happened. Eventually, after 20, 30 minutes, that’s when the police came in, and the [protesters] jumped out the window.

I like to think that, as somebody who is here as a steward of the ideals of the IOP, that that was a period in time where we reflected those ideas. Let’s engage in dialogue, respectful dialogue.

CM: Looking back at your tenure at the IOP, is there anything you wish you had done differently as director?

HH: I wish I had more time. And, you know, that was self-imposed. I made a three-year commitment and knew that I really could not take any more time away from my family. And so, you know, it always takes you about a year to get your feet underneath you and another year to get people to trust you, and so I feel like we’re kind of hitting on all cylinders. But when I leave here, I’ll go on to the advisory board—I mean, I’m not really leaving the IOP in terms of thought participation on what this [institution] should be.

I’m trying to think of regrets. I mean, I am somebody who does a lot of evaluation at the moment, right? So if I think I’m not articulating or not doing enough with students, I’ll try and correct that. This has been a journey of, what can we

do differently? How are we going to respond to students who have legitimate concerns about whether we’ve been responsive to their issues? How can we do better?… If I had to leave with one goal, I would say expanding the internship programs would be a huge goal. I once told [a group of College parents that] my goal for the IOP would be that every student who qualified and wanted an internship could get one. And I don’t think we’re there.

CM: You spoke about budgetary issues a bit earlier. What do you see as the biggest challenges for the IOP going forward, after you leave this role?

HH: Funding—to fully fund all the things that we should be doing here on campus, especially expanding our internship program and our civic engagement. I think we do a great job with speakers. I think we do a great job with Fellows, thanks to the Pritzker family. We have what we can manage there.… I think the next IOP director is going to have to be very forward-facing on funding challenges and fundraising.

[And] continuing to build out student engagement. Listening to students. To me, a fellowship is successful when I hear a fellow say, “My favorite part is office hours. I love the kids”—I had someone tell me that reason. And I just think,

“Now I’m glad we picked you because you get it, you get why we’re here,” which is to expose people [to nontraditional figures with] the Pritzker Fellow program, to not just have more traditional former elected officials. Even if you’re picking former elected officials like Jon Tester, Jon Tester’s been teaching people a lot about farming, about nutrition, and that’s something that students wouldn’t otherwise [learn about].

Obviously, Pete [Buttigieg] is a fan favorite, but you know, he’s not really saying anything different than what he says every day. That’s valuable for students, and I’m grateful that he has accepted the opportunity. But we also want to expose students to a whole different way of thinking about how they can engage civically, rather than just traditional political engagement. We want to maintain that responsibility, but we also want to say, “You can do it through art, you can do it through music, you can do it through your religion—you know, how does that work? As a scientist, what do you need to do to be engaged?”

CM: What is next for you? What do you plan to do after you step down from the director role?

HH: I have a lot of obligations and responsibilities beyond the IOP. Because I

knew that this was time-limited, I didn’t really cut back on a lot of my nonprofit work [or] civic engagement. I’ve been very involved in pro-democracy work since I left the Senate. So for me, what this will do is give me more time with my husband and my new grandbaby. It’s almost cliché, “Oh, I’m leaving to spend more time with my family.” But I’m turning 70 this year, and so for me, that was kind of a pivotal point of, you have maybe, God willing, another 10 years of runway. How are you going to use it?

Like I said, that will include staying very involved in the IOP. They may want me to come back and moderate a program; they may want me to come back and do a student engagement [program]. I’m [still] going to be engaged here at the University of Chicago, even though I won’t be the director of the IOP.

CM: Has there been any progress on the search to find a new director?

HH: It’s very robust. We’re just very grateful that there’s been so many really great candidates who have stepped forward. We continue to work with the University, because obviously the University will be part of that process, the president and the provost, but we’re excited about the depth and the experiences of the applicants.

By KATHERINE WEAVER | News Editor

A judge for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois dismissed a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) case against a unit of University Trustee Don Wilson’s (A.B. ’88) Chicago-based crypto trading firm Cumberland DRW on March 31. The SEC and Cumberland DRW jointly sought the dismissal.

In a March 27 press release, the SEC said its decision to drop the case “rests on its judgment that the dismissal will facilitate the Commission’s ongoing efforts to reform and renew its regulatory approach to the crypto industry, not on any assessment of the merits of the claims alleged in

the action.”

The Biden administration greatly expanded cryptocurrency regulation under the leadership of then SEC Chair Gary Gensler, especially after the collapse of digital currency exchange platform FTX in 2022. Shortly after returning to the White House, the Trump administration began scaling back enforcement efforts against cryptocurrency firms, leading to the abandonment of a series of lawsuits from the last few years against firms such as Coinbase.

According to Crain’s Chicago Business, the SEC’s case against Cumberland DRW was a “holdover from the tail end of the Biden administration’s SEC,” and many similar lawsuits had already been dropped.

In a press release on October 10, 2024, the SEC announced that it had charged Cumberland DRW with violating federal registration laws for selling more than $2 billion of cryptocurrency assets as securities. The statement alleged that the unregistered dealings had been going on since at least March 2018.

Cumberland DRW claimed in a separate October 10 statement posted on X that the SEC had made several errors in both the communication and enforcement of Biden-era registration law changes. “Today’s complaint is the first time the SEC has outlined the specific transactions at issue,” the statement read. “The SEC asserts these

“We look forward to continuing our dialogue with the SEC to help shape a future where technological advancements and regulatory clarity go hand in hand.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 8

transactions required us to register as a broker-dealer. While we strongly disagree, we took that step and acquired a registered broker-dealer in 2019. Only then… were we told we could only use our broker-dealer to trade [Bitcoin] or [Etherium] (both commodities and not under the jurisdiction of the SEC).”

In an interview two weeks later with CoinDesk, a cryptocurrency-focused

news website, Wilson claimed that the SEC’s guidelines for cryptocurrency firm registration are unclear by design: “This dynamic put the SEC in a position where they could say everyone is breaking the rule, and we’re just going to go after whoever we want to.”

President Donald Trump ran on a platform of being friendlier to the cryptocurrency industry than the Biden administration. In March, Trump signed an executive

order to establish both a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and a U.S. Digital Asset Stockpile to capitalize on Bitcoin and other digital assets owned by or forfeited to the Department of the Treasury.

“The Executive Order begins to resolve the current disjointed handling of cryptocurrencies seized through forfeiture by, and scattered across, various Federal agencies,” the fact sheet on the order read.

“As a firm deeply committed to the

principles of integrity and transparency, we look forward to continuing our dialogue with the SEC to help shape a future where technological advancements and regulatory clarity go hand in hand, ensuring that the U.S. remains at the forefront of global financial innovation,” Cumberland DRW wrote in a statement on X announcing the joint filing to dismiss the case.

Aaryan Kumar contributed reporting.

By KALYNA VICKERS | Senior News Reporter

The inaugural Chicago Energy Conference, formed as a partnership between the UChicago Energy and Climate Club (ECC) and Northwestern University’s Energy and Sustainability Club, convened students and faculty from both universities on April 5 to engage with leaders across the energy sector.

The conference examined critical issues surrounding the energy transition, with a particular focus on facilitating student engagement in the industry. The Maroon spoke with the event’s four executive directors: UChicago fourth-years Eric Fang, Khwaish Vohra, and Raghav Pardasani and Northwestern fourth-year Quinn Cook.

“For our conference, it really is for the students and by the students,” Vohra said. “From the ground up, this has been something where we worked together to highlight what we as students are interested in learning more about.” Educating students on the multifaceted nature of the energy transition was a core goal of the event. “Energy is at the intersection of solving climate change, improving lives, and driving financial innovation—that’s what drew me in and what makes this space so exciting,” Fang said.

According to Fang, who previously served as a news editor for the Maroon, the conference aimed to break the mold of

traditional discussions by incorporating perspectives from a range of disciplines, including law, human rights, finance, and technology.

A central purpose of the event was to expose students to the breadth of career paths within the energy industry. “There are so many opportunities for students interested in grassroots activism but fewer for those looking to explore professional pathways in energy and climate. With ECC, we’re not just organizing a conference—we’re giving students the experience of running a major event and connecting them with industry leaders,” Pardasani said.

“At Northwestern, there are a lot of clubs focused on traditional environmental activism. But there’s a gap when it comes to professional development in energy and sustainability,” Cook added. This conference fills that gap—it’s about showing students that energy is a great place to build a career.”

Building upon the success of similar energy conferences held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Duke University, the Chicago Energy Conference hopes to establish itself as a premier event in the Midwest. “Our vision was to create a Midwestern energy conference, not just a UChicago-specific event. Partnering with Northwestern has helped us expand our

reach, bring in a wider breadth of speakers, and reinforce the Midwest’s role in the energy transition,” Vohra said.

Panel topics ranged from decarbonizing buildings to exploring the role of nuclear power in Illinois. “We started with a big question: What policies, investments, and technologies are needed to enable the new energy age? Every panel we created stemmed from that question,” Fang said.

Other discussions addressed the critical materials necessary for battery storage and the future of green hydrogen, providing an overview of the sector’s key challenges and innovations.

“My passion for climate and energy stems from a love for people—you can learn from books and classes, but so much of it comes from engaging with others and hearing their experiences,” Pardasani said. Cook added, “There’s no silver bullet for learning. Don’t be scared to walk up to someone, tell them about your interests, and ask what you should see.”

Keynote speakers at the event included Kate Ringness, former senior adviser to the secretary at the U.S. Department of Energy; Seth Darling, chief science and technology officer for Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Energy Technologies directorate; and Jen Zhao, chief operating officer of investment banking at Marathon Capital. Their remarks were accompanied by eight panel discussions held throughout the day.

Ringness opened the day with remarks on the Biden administration’s strategy to grow the energy economy, including its investment incentives, workforce development, and research and development support.

“Overall, investments in U.S. battery and medium manufacturing have quadrupled, and nearly $150 billion has been invested in EV and battery supply chains,” Ringness said. However, she warned that uncertainties, such as a freeze on Department of Energy grants and loans, pose significant risks to the energy economy. She emphasized the importance of community engagement and advocacy in sustaining progress.

Darling addressed the growing complexities of the energy transition, highlighting a central dilemma: how to meet skyrocketing energy demand—driven by

“This institutional partnership... allows us to learn from each other... and broadens our understanding of the energy space.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 9

AI and electrification—while still reducing emissions and ensuring a resilient energy grid. Despite the rapidly decreasing cost of renewables, he said that fossil fuels continue to dominate the global energy supply.

“Data centers in the U.S. today already use about 5 percent of our electricity. That’s projected to be 10 percent in three years,” Darling said. He framed the energy transition as an approaching systems problem. To meet this challenge, Darling referenced emerging technologies such as SMART energy plasmas, small modular reactors, and advanced catalysts for hydrogen production.

One panel focused on the clean hydrogen market in both domestic and interna-

tional contexts. “Hydrogen is going to sit with any other fuel and help the economy grow. Our energy needs are not going down—they’re going up,” said Fabrice Bonvoisin, one of the panelists. “There’s going to be room for other fuels and other types of energy to coexist, with batteries, with renewables, with natural gas, nuclear. We’re going to need all of it working together in unison to see this economy grow.” The session emphasized hydrogen’s potential in decarbonizing transportation and shipping while acknowledging cost and infrastructure challenges. Panelists also highlighted the need for international collaboration and the use of AI to improve hydrogen transactions.

Emphasizing the global dimension of

the energy transition, organizers incorporated international perspectives into the programming. “A lot of conversations about energy and climate in the U.S. are focused on domestic issues, which are important, but I really wanted to bring in global perspectives. That’s why we included a panel on energy transition in the Global South, with perspectives from Latin America, India, and Africa,” Pardasani explained.

The Global South panel examined major energy transition projects, including a 2022 initiative in El Salvador that Hong Zhang Durandal, a panelist, cited as reducing emissions by 400,000 metric tons of CO2 and saving $400 million. Panelists advocated for policy consistency, community involvement, and economic incentives

to drive sustainable transitions, particularly in developing markets such as India.

Looking ahead, the conference directors plan to continue the event annually, alternating between Northwestern University and the University of Chicago as the host campus. They aim to cement the partnership between the two institutions and continue providing students with exposure to energy-related careers.

“This institutional partnership is really unique. It’s not just about bringing UChicago and Northwestern students together— it’s about creating a space where we can all learn by doing,” Cook said. “It allows us to learn from each other, professionally and personally, and broadens our understanding of the energy space,” Pardasani added.

By JULIAN MORENO | Senior News Reporter

UChicago’s University Research Administration received notice last week that all active and upcoming grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to the University would be terminated. According to the NEH website, the NEH had been funding 10 active projects at the University worth a total of $3.1 million. It is unclear how much of this funding has already been allocated and what will be lost due to the cuts.

The announcement comes after the Department of Governmental Efficiency Service (DOGE) placed 145 NEH staff members—80 percent of the NEH’s staff—on administrative leave. The New York Times reported last week that the NEH planned to cancel more than 85 percent of current grants and would focus on “patriotic programming” going forward.

Founded in 1965 under President Lyndon B. Johnson, the NEH has provided over $6 billion in funding to museums, universities, libraries, and other cultural

institutions from all 50 states. Before the cuts, the NEH was funding more than 1,200 active projects and had a combined annual budget of roughly $200 million.

The NEH cancellations come amid several other cutbacks to academic research under the Trump administration. On February 7, the administration sought to limit “indirect” costs in National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants, threatening $52 million annually awarded to UChicago. NIH also canceled six UChicago research grants worth nearly $6 million in March.

Two UChicago researchers told the Maroon that NEH Acting Chairman Michael McDonald initially conveyed the grant termination to the University Research Administration, which then notified researchers. A professor in the College, who spoke to the Maroon on the condition of anonymity, described the termination letter as “laconic” and “a very weird and bone-chilling text.”

Associate professor Niall Atkinson, who leads a project to produce a digi-

tal map of 15th-century Florence, told the Maroon that the termination of his $349,969 grant was unexpected. “I called the person who was listed as our grant specialist.… She said that my grant looked good and everything was fine [on] Wednesday, and [the grant] was terminated Thursday.”

Atkinson said that his team’s planned trips to Florence to carry out topographic work and architectural analysis have been suspended. He noted that the biggest consequence of the grant termination is the loss of income for researchers on the project.

“The worst part of losing the grant is the fact that [for] my colleague who’s working out of Virginia—this was her only income,” he said.

Concerning the possibility of the University resisting the broad assault on higher education, Atkinson remarked that the University “probably can’t do much without the approval of the Board of Trustees.”

“That seems to be, for me, the real problem in getting any real action or resistance going on from the University,”

he said. “[The Trustees’] obligations are raising money and the financial soundness of the University. They have nothing to do with academics or research.”

“I think part of the reason the University is not just automatically offsetting the losses that it’s seeing in the humanities right now is that they’re… worried about more [losses] to come,” the other professor said.

The Division of the Arts & Humanities directed the Maroon to a spokesperson for the University, who did not respond to a request for comment.

.

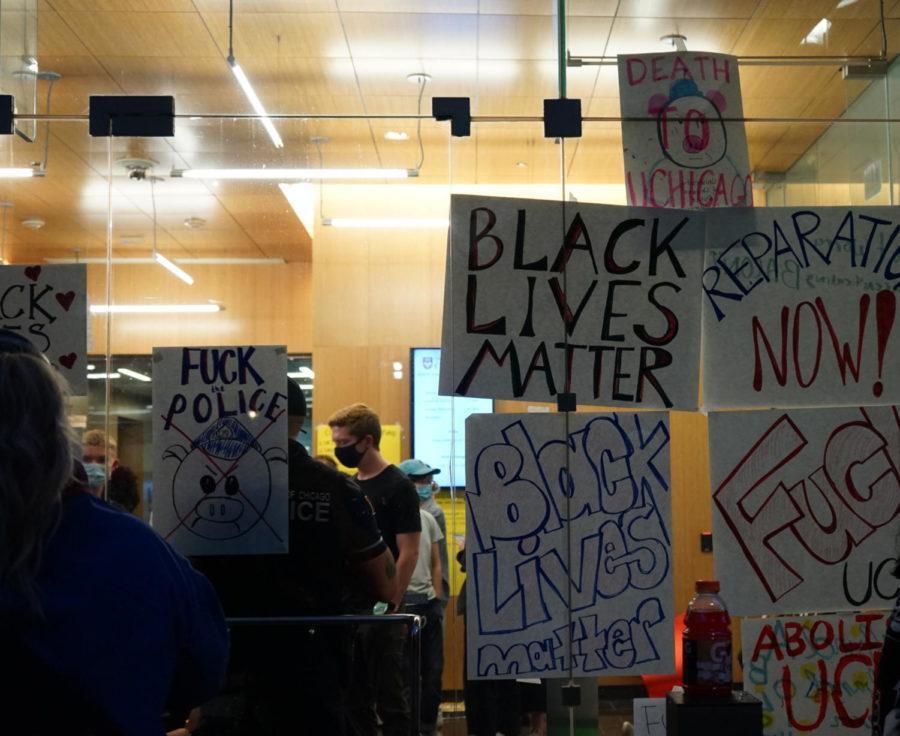

Protests over UCMed’s lack of a Level I adult trauma center beginning in 2010 resulted in student arrests and misconduct by an undercover UCPD officer, forcing the University to reevaluate its protest policies and how it communicates them to students.

By EVGENIA ANASTASAKOS | Managing Editor, CELESTE

| Grey City Editor, and NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | Deputy News Editor

This piece is the second in a three-part series on the history of protest and the disciplinary system at UChicago. It covers the period from 2010–20. Other articles cover 1967–74 and 2023 to the present day.

From 1974 to 2013, the All-University Disciplinary System—created to deal with many of the challenges that arose during the 1969 protests—was rarely used. Instead, disruptive conduct was largely handled within decentralized divisional disciplinary systems.

This was not for lack of protest on campus, however. Students widely protested the University’s refusal to divest from companies doing business with apartheid South Africa in the 1980s. Similar calls for divestment focused on the Sudanese government during a period of mass killings in the early 2000s. However, protesters in the post-Vietnam War era intentionally de-escalated their demonstrations to be less disruptive, rendering the All-University system less useful.

“After a lot of talking back and forth… it was decided that we did not want to commit civil disobedience because we did not want to divide the community,” one former protest organizer told the Maroon in 2015, referencing the 1980s anti-apartheid movement on campus.

The lull in disruptive activity on campus ended with the death of a youth activist in 2010, when demonstrators began

protesting the absence of an adult trauma unit at the University’s Center for Care and Discovery.

“There will be more actions; there will be more protests; there will be more direct actions. We’re not turned around by what happened [January 27],” a local South Side activist said in a February 2013 address to protesters outside of then University President Robert Zimmer’s house.

The University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) and Chicago Police Department (CPD) arrested dozens of students and community activists over the following years as trauma center protests escalated.

UCPD’s conduct while handling the protests generated concerns of police overreach and called into question the management of disruptive conduct of protesters unaffiliated with the University.

As a result, the University began a new process in 2014 to reevaluate its protest and disruptive conduct policies. This process, which concluded in 2017, would ultimately result in the abolition of the All-University Disciplinary System in favor of a new Disciplinary System for Disruptive Conduct, which both removed any limitations on which University community members could file complaints and offered less transparency in its disciplinary processes.

An activist’s death sparks

For nearly three decades, beginning in the early 1990s, the South Side had no Level I adult trauma centers—hospitals capable of providing specialized, 24-hour care to adults with traumatic injuries, such as those caused by serious car accidents or gunshots.

UChicago Medicine’s (UCMed) adult trauma center closed in 1988, and Bronzeville’s Michael Reese Hospital closed its center in 1991. To receive trauma care, Southsiders needed to travel to Northwestern Memorial Hospital, 10 miles away.

The death of 18-year-old youth activist Damian Turner in 2010 gave rise to calls for a new Level I trauma center at UCMed. Turner was shot four blocks away from the hospital but had to be transported to Northwestern Memorial for care and died en route. At the time, his mother told the Maroon that she believed that he may have survived if he had been able to receive more immediate care at UCMed.

An earlier WBEZ analysis found that Southsiders had to travel 50 percent longer on average to receive trauma care. Later, a Northwestern University study would find that “Chicago-area gunshot victims who are shot more than five miles from a trauma center have a higher mortality rate.”

During a 2010 press conference organized by Turner’s mother, protesters read a letter delivered to UCMed spokesperson John Easton.

“At the same time as your hospital is embarking on a multi-million research pavilion to treat complex diseases and

surgeries, there seem to be no plans to develop the resources to treat the hundreds of South Siders dying from gun violence,” the letter read.

UCMed broke ground on what would eventually become the Center for Care and Discovery in 2009. The new facility would “transform how we care for all patients, using leading-edge technology and innovative research to deliver advanced clinical treatments in a setting that offers a superior healing environment,” according to a 2012 press release.

At an estimated cost of $700 million, the Center would include units for cancer, gastrointestinal disease, neuroscience, high-technology radiology, and advanced surgery, using its expanded footprint and larger patient rooms—along with its proximity to University research divisions—to accommodate future developments in medical technology.

Notably, the Center did not include a Level I adult trauma center.

Following the 2010 conference, organizers with Southside Together Organizing for Power (STOP) and its youth affiliate, Fearless Leading by the Youth (FLY); University student group Students for Health Equity (SHE); and several other groups combined to form the Trauma Care Coalition (TCC).

In its early days, TCC used door-todoor canvassing and student outreach to build support for its campaign demanding UCMed establish a Level I adult trauma center on its campus. They also staged protests, which included “die-ins” and a mock-funeral during a 2011 Martin Luther King Jr. Day event. By 2013, the CONTINUED ON PG. 13

“The

movement had taken a different tack—focusing on direct action against UCMed.

On January 27, 2013, several dozen demonstrators organized a sit-in during an invitation-only tour at the Center for Care and Discovery.

About 50 protesters entered the Center, announcing their intent to protest via a megaphone.

UCPD officers took out their batons and started shoving protesters toward the door, according to a Chicago Tribune report. Minutes later, CPD officers arrived. Several protesters said they were shoved to the ground after struggling with UCPD officers.

CPD officer Francis Frye explained that UCPD didn’t “have the expertise in dealing with crowds.”

“[UCPD] is finally getting a taste of

values and we will not tolerate it.”

what it means to be police,” Frye told the Maroon at the time.

According to a University statement, four protesters were arrested after demonstrators disregarded a UCPD request that they leave.

The Maroon identified the arrestees as Toussaint Losier, an eighth-year graduate student in UChicago’s history department; Victoria Crider, a 17-yearold student at King College Prep High School; Alex Goldenberg, the cameraman for STOP; and Jacob Klippenstein, a representative from the Anti-Eviction Campaign.

By the following week, an online petition calling on the University to explain police conduct at the protest had garnered more than 2,000 signatures. The petition claimed that police caused the only violence at the event, according to reporting from neighborhood news outlet DNAinfo. Specifically, members of STOP alleged that UCPD officers singled out Losier and beat him despite his lack of resistance.

All four arrested individuals present at the January protest were held without charges in a CPD station overnight. The lawyer for the defendants told the Maroon at the time that CPD waited on UCPD to process the charges, resulting in delayed access to counsel for the defendants.

The three arrested adults—Losier, Klippenstein, and Goldenberg—went to trial in March 2013. All were charged with trespassing, and Losier was also charged with resisting arrest.

The trial took place at the District 2 CPD courthouse. Eight University representatives were present at the trial, including five UCPD officers whom Goldenberg and Losier claimed were at the protest.

At the start of the proceedings, the University offered each defendant a plea deal, which Losier refused.

order] with the University of Chicago…. Our lawyer went back and pushed them on it. They said I was a student and that doesn’t make any sense,” Losier told the Maroon

The no-contact order would bar defendants from returning to the University and the site of many previous demonstrations. According to the defendants’ lawyer, Joey Mogul, the order would infringe on the defendants’ First Amendment right to continue protesting the lack of an adult Level I trauma center on the South Side.

On the second day of the trial, the three protesters accepted revised versions of the plea deals. Both Goldenberg and Klippenstein agreed to fewer than six months of supervision and signed a no–unlawful contact order with the University—allowing them to visit UCMed for medical care but no longer participate in disruptive protests on campus. The charges did not remain on their records. A judge sentenced Losier to a supervision period that lasted only a day.

“We took these deals mainly because we wanted to make sure that we had all the time and the resources available to us to really organize people,” Losier said in a video shared with the Maroon following the court decision.

TCC led another protest on February 23, the day that the Center opened and patients were transferred into the building. Prior to the demonstration, which included a march around the facility ending at Zimmer’s home, organizers met with UCPD and University officials to ensure that the planned activities would not interfere with medical transportation while still allowing organizers to communicate their message.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 12 CONTINUED ON

“I was offered a one-year conditional discharge, which means it goes on my record. I was also offered [a no-contact

During the demonstrations, then UCPD detective Janelle Marcellis went undercover in the crowd, actively participating in the protest while relaying information to a UCPD deputy chief. UCPD officers were stationed in plainclothes along the route and had been instructed to “blend in and get intel.”

A 2013 Maroon investigation ob -

tained photographs of Marcellis’s cell phone, which revealed texts to Deputy Chief of Investigative Services Milton Owens reading, “In crowd w[ith] sign. All is well…. They are talking about wanting three things charges dropped trauma center and police to work [sic]” She carried a sign throughout the event and put a sticker on her mouth reading, “Trauma center now,” matching many other demonstrators.

Trauma center protesters march through the quad on the way to University President Robert Zimmer’s house in 2014. chicago maroon photographic archive

UCPD officer Janelle Marcellis holds a protest sign and wears protest tape over her mouth at a trauma center protest in 2013. She infiltrated the protest to gather intelligence. chicago maroon photographic archive.

When the investigation was published, then University Provost Thomas Rosenbaum released a statement condemning UCPD’s infiltration of the protest and indicating that it would be investigated.

“The behavior as described [in the Maroon] is antithetical to the University’s values and we will not tolerate it,”

“This prohibition, taken literally, is too broad. Vocal protest, and demonstrations in particular, are by their nature disruptive to some degree.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 13

Rosenbaum wrote. “The University will investigate this expeditiously and take immediate steps to ensure it is not repeated.”

The University hired law firm Schiff Hardin LLP to conduct an external review of UCPD’s handling of the January 27 and February 23 protests and determine whether “University policies had been violated.” Two UCPD officers were put on leave pending that investigation, per the Chicagoist.

In line with the report’s recommendations, UCPD fired Owens, who was deemed responsible for the undercover operation, and began drafting a more comprehensive protest policy in line with “University values.” UCPD’s general orders, which govern officer conduct, now include a section specifically devoted to handling protests.

In 2018, Owens won a wrongful-termination lawsuit against the University after hearings revealed his initial skepticism of the use of plainclothes officers at the February 23 protest. Marcellis still works for UCPD as the deputy chief of patrol services.

The Schiff Hardin report also recommended a “review, assessment, and clarification of University and UCPD policies and protocols related to demonstrations and protests, including the role of the Dean on Call program… followed by appropriate training and education of all involved parties.”

Despite Owens’s initial firing and Schiff Hardin’s recommendations, activists did not believe that the University addressed all of their concerns about UCPD conduct.