STEFFAN MEYRIC HUGHES, EDITOR

Funny things, anniversaries. If you accept that we appreciate milestones, arbitrary though they are, then we can agree that 100 is a big one. It’s how we mark the passing of history after all. The Rolex Fastnet is 100 years old this year. It’s probably the biggest, best known yacht race in the world, albeit that most of its fame stems from the tragic disasters of the 1979 race. The club that it founded – the Royal Ocean Racing Club – is also a century old this year. But how about the Royal Thames Yacht Club? An astounding 250 years old. That’s older than the America’s Cup. Come to think of it, it's older than America. King’s Boatyard in Suffolk (who built Arthur Ransome’s yachts) is 175 years old this year. This is a demisemiseptcentennial, quartoseptcentennial or terquasquicentennial or (in slang!) a dodransbicentennial anniversary. Why have one ridiculous word that no one uses when you can have four? And finally, it’s the 85th anniversary of Operation Dynamo, the Dunkirk Little Ships. There’s no silly word for 85, but if Operation Dynamo were your wife, you’d give her a moonstone. Either way, the fleet will return to Dunkirk this year, for the first time in a decade. See all this and more in our big events guide in this issue.

classicboat.co.uk

Telegraph Media Group, 111, Buckingham Palace Road, London, SW1W 0SR

EDITORIAL

Editor Ste an Meyric Hughes

ste an@classicboat.co.uk

Art Editor Gareth Lloyd Jones

Sub Editor Rob Melotti

ADVERTISING

Portfolio manager Hugo Segrave

Tel: +44 (0)7707 167729 hugo.segrave@chelseamagazines.com

Advertisement Production Allpointsmedia +44 (0)1202 472781 allpointsmedia.co.uk Published

ISSN: 0950 3315

PUBLISHING

Acting Director of Commercial Revenue

Simon Temlett

Publisher Greg Witham

Chief

Tel: +44 (0)1858 438 442

Annual subscription rates: UK £75 ROW £87 Email: classicboat@subscription.co.uk Online: www.subscription.co.uk/chelsea/help Post: Classic Boat, Subscriptions Department, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Lathkill Street, Market Harborough LE16 9EF Back Issues: chelseamagazines.com/shop/

The Chelsea Magazine Company Ltd Telegraph Media Group, 111, Buckingham Palace Road, London, SW1W 0SR chelseamagazines.com ©Copyright The Chelsea Magazine Company

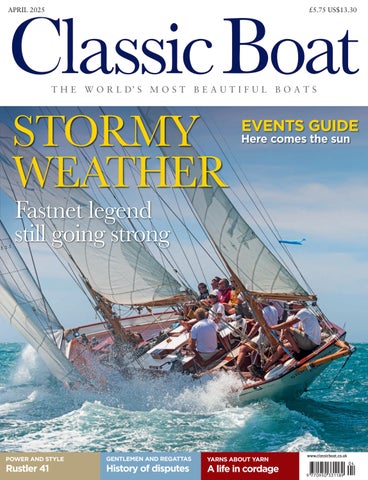

COVER STORY

4 . STORMY WEATHER

Catching up with a Fastnet legend and one of the world's most loved yachts

12 . ROYAL THAMES AT 250

e year of celebrations has begun...

18 . SAOIRSE

Raised-topsides yacht restored for the Gills, of yellow oilskin fame

28 . MEET THE INSURER

Simon Hedley is an insurance guy at Pantaenius... and a good laugh too!

30 . RUSTLER DOES POWER

First motorboat from venerable English sailing yacht builder

36 . 8-M WORLDS

e buoyant 8-M class thrashing it out in Scotland last autumn

COVER STORY

40 . EVENTS GUIDE 2025 e big events, races and regattas

48 . REGATTA HISTORY

e trials, the tribulations, the date clashes... it's always been this way

54 . CANVAS ART

Photographer Kos Evans and her project printing photos on famous sails

58 . THE YARN OF YARN

A rigger's life in rope, and a guide to cordage available to buy today

72 . BARUNA REBUILD PART 4

4

30

e end of our in-depth look at the rebuild of the big S&S inboard yawl

chelseamagazines.com/marine

One of Olin Stephens’ favourite designs has raced offshore and in regattas around the world for nearly a century and shows no sign of slowing down

It was in 2007 in Argentario that Olin Stephens, then aged 98, last sailed on Stormy Weather, the yawl which he had designed almost three quarters of a century earlier and which was said to be one of his favourite designs. “It got quite windy towards the end of the race,” recalls Stormy Weather’s owner Christopher Spray, “and he was getting a bit wet from some breaking waves. I asked him if he was alright and he said ‘I have been on this boat in far worse conditions than this’!”

Stormy Weather was built by Henry Nevins at City Island, New York, and launched on 14 May 1934. She was a direct development of another yawl, Dorade, which Olin had designed at the age of just 21 and which had won the 1931 transatlantic race from New York to Plymouth, as well as the Fastnet Race that year and again in 1933. Slightly longer and with proportionally more beam than Dorade, Stormy Weather was built under the watchful eye of Olin’s brother Rod, in just four months. She had Philippine mahogany planking on steamed New England white-oak frames, an oak keel, stem and stern post, and a Port Orford cedar deck laid on deck beams of spruce and oak. Her commissioning owner was Philip LeBoutillier, the proprietor of a chain of department stores, and it wasn’t until his new boat’s launch was imminent that he chose a name for her. After hearing Lena Horne sing the song Stormy Weather while he was dining with some friends at a restaurant in Long Island, his new boat was duly christened by his daughter Polly. Uffa Fox, when later analysing Stormy Weather’s hull lines, wrote that she “should glide along with the effortless grace of a bird soaring through the air.”

And glide along she did. In 1935, with Rod Stephens as her skipper, she repeated the successes of Dorade four years earlier by winning the transatlantic race (this one from New York to Bergen in Norway) and the Fastnet Race. Before leaving New York her Graymarine 35hp petrol engine was removed along with its stern gear. Amongst her innovations was a permanently installed thermometer for sea-water temperature readings, and The Yachtsman reported that “the success of Stormy Weather in the recent race to Bergen was largely due to

skilful navigation. Thanks to frequent wireless reports her navigator was able to note the approach of depressions, make his own weather charts, and find a passage through the ice, to say nothing of shortening the voyage.” Music may also have helped as various members of the crew played harmonicas, accordions, a tin whistle, a guitar and a kazoo during the course of the voyage. The 70ft ketch Vamarie won line honours and her crew thought they would be declared the winners on handicap as well, but just as they were finishing their victory dinner, they heard that Stormy Weather had finished barely five hours after them and so won by 42 hours on corrected time.

Previous Page: Racing in light airs off Cannes

Above: Stormy Weather was a development of the design of another famous S&S yawl Dorade

Main image right: Fully crewed or singlehanded, Stormy Weather’s hull is designed to glide

After leaving Bergen with the King of Norway’s cup, Stormy Weather cruised along the Norwegian coast, through the Dutch canals and then to the Isle of Wight. That year the Fastnet race started in Yarmouth for the only time in its history, and in a predominantly light airs race, Stormy Weather finished third and won by over six hours on corrected time. L Luard, who was sailing on another Olin Stephens-designed yawl, Trenchemer which came second, later wrote in The Yachtsman that “Stormy Weather deserved her win. She was sailed better than any other boat; her gear, perfect for its task, never failed; her crew, a trained team, skippered by Rod Stevens, were flawless in efficiency.”

Back on the other side of the Atlantic, Stormy Weather continued her winning ways. She won her class in the 1936 Newport to Bermuda race, and then from 1937 she won five consecutive Miami to Nassau races. In her first 20 years and with various owners after LeBoutillier – Bob Johnson, Bill Labrot and Fred Temple – she took part in 31 major ocean races, winning 12 overall and coming first in class 15 times. In 1947, Fred Temple took Stormy Weather to the Great Lakes where she came fifth in class in the Chicago to Mackinac race; and in 1954 he sold her to James J O’Neill who mainly sailed her in New England. From 1957 she was owned by FC Cunningham who was a member of the Seawanhaka YC and kept Stormy Weather in the British Virgin Islands. In 1977 he died suddenly of a heart attack, intestate and with Stormy Weather moored in West End Harbour with no official documentation on board. This put the British authorities in a difficult situation, and so they appointed American architect Doug White and his wife, Sue, to look after the boat. They were given permission to run Stormy Weather as a charter boat but she was in poor condition, and they found they were losing money. The authorities had also appointed Briton Paul Adamthwaite – who had previously served in the Royal Navy – as Ship’s Husband, and in 1981 he did a deal with Doug whereby he became sole owner. “I think I only paid him a couple of thousand dollars,” Paul told me.

Paul had already begun to restore Stormy Weather, initially in the US Virgin Islands but then in the British Virgin Islands. Most of the frames were broken and so were replaced with new ones in laminated oak; a two-layer plywood subdeck was fitted with a teak deck laid on top; and the Mercedes diesel engine was replaced by a direct drive Yanmar 3GM.

At some point, the original mast had been damaged in a lightning strike and had been replaced with an aluminium one from a 12-Metre, and may have been slightly reduced in length. Paul was keen to replace it with a timber one and

so he flew to the west coast of Canada to source some suitable Sitka spruce which was shipped to Camden. William Cannell Boatbuilding then built a new mast which was identical to the original except that – on the advice of Rod Stephens – its section was half an inch bigger fore and aft and a quarter of an inch smaller athwartships. It was shipped to the British Virgin Islands where it was completed and stepped. By January 1984 Stormy Weather was sailing again but with no interior and limited deck fittings. Almost all of the original joinery panelling had survived and was subsequently refitted, but the aft cabin was almost entirely rebuilt.

Paul and his wife Betty Ann then spent many years living on board Stormy Weather and sailing her extensively, typically spending winters in the Caribbean and summers in Europe, mainly in France where he had been a student. Paul crossed the Atlantic 36 times on Stormy Weather, three times solo and 14 times with his wife amongst the crew. They occupied themselves with heritage projects, youth sailing, museums and yachting archives, and were heavily involved in establishing the Douarnenez Festival. They raced Stormy Weather regularly, taking part in the Fastnet Race seven times (finishing 6th overall in 1995 – the 60th anniversary of her first victory – and winning the Iolaire block, for the oldest competing boat, four times); through their friend Don Street – the owner of Iolaire, of course – they first became involved in the Glandore regatta in Ireland and then took part in it about a dozen times; and they also competed in many Caribbean races including Antigua Race Week numerous times.

In 1997 the Adamthwaites took Stormy Weather up to Lake Ontario where they had a home and from where they day-sailed her for the remainder of their ownership. Then, one day in the spring of 1999, Paul had a call to say that the Italian Giuseppe Gazzoni who had just had Dorade restored at Cantiere Navale dell’Argentario, was looking for a similar boat to buy and restore. Paul was becoming all too aware that he was unlikely to ever cross the Atlantic again in Stormy Weather and that she “was unhappy in the fresh water of the Great Lakes and in the freezing conditions we experience during the winter”. He soon agreed to sell her to Gazzoni, albeit with some

regret. “Stormy Weather was the love of my life,” he told me.

Stormy Weather was shipped to Italy where, despite being in poor condition, she raced at Argentario in 1999 and came first in class. She was then taken to Cantiere Navale dell’Argentario for work to begin. Her whole deck was renewed with 28mm thick teak laid directly on the deck beams, and all new deckhouses were built to the original design. Many of her deck fittings were recast and then chromed, and a new mizzen mast was made as the existing one was badly split. With the work complete she took part in the Argentario regatta in 2001, coming first in class again but this time with the 94-year-old Olin Stephens on board for every race. She was then brought to the UK to compete in the America’s Cup Jubilee regatta in which she was skippered by the yacht designer Doug Peterson. She was the winner of the Vintage Division 3 class and was also shortlisted for the Concours d’Elegance, after which Andrew Bray, the editor of Yachting World and chair of the judging panel, wrote: “It was a privilege and a treat, the experience of a lifetime to walk the boards of such a distinguished yachting hall of fame…to wonder at the perfect sheer line and balanced overhangs of (various boats including) Stormy Weather.” By this time, Gazzoni had decided to sell her as he was keen to buy and restore another S&S yacht, the 1935 53ft sloop Sonny.

A couple of years earlier, Christopher Spray, whose only previous boat had been an Enterprise dinghy, had started looking for a classic boat that would be suitable for family cruising and racing. “I probably looked at almost all of the boats that are on the dock here at some point,” he told me when we were at Regates Royales in Cannes recently. He realised that a Sparkman & Stephens yawl would suit his needs and seriously considered Dorade before deciding that she would be “a little bit too narrow or too small”. So he contacted the yacht broker Mike Horsley to see if Stormy Weather might be available. Mike was initially doubtful, but about six weeks later he phoned Christopher to tell him that she was.

So Christopher went to look at her in Cowes where Doug Peterson showed him round, and soon afterwards he made an offer which was accepted. “About a week

Clockwise from top left: The mizzen sheeted at the end of the A-shaped bumkin; Waiting for the wind off Cannes; The mainsheet horse straddling the cockpit; Functional galley; Buttoned leather saloon seating; The aft cabin has its own companionway; Chromed halyard winch; Passerelle support clamped to the bumpkin

LOA: 53ft 11in (16.4m)

LWL: 39ft 9in (12.1m)

BEAM: 12ft (3.7m)

DRAUGHT: 7ft 11in (2.4m)

DISPLACEMENT: 20.3 tonnes

SAIL AREA: 1,332 sq ft (123.7m2)

later 9/11 happened and I wondered if I had made the right decision to make a relatively expensive purchase just as the world was going pear shaped,” he told me. “But I decided to press on and have never regretted it.”

By the summer of 2002, Stormy Weather was back in the Mediterranean and that is where Christopher, his family and his friends have mostly sailed her since. One year they took her to the Caribbean – with Christopher and his son William on board for the crossing – to race in Antigua Classics. They have taken part in numerous classic boat regattas where their results are generally “there or thereabouts in most regattas, we are reasonably consistently on the podium, depending on the makeup of the class,” said Christopher. Over the years Stormy Weather’s competition has included several other S&S designs including Dorade, Comet, Argyll, Skylark and, more recently, Baruna

In 2015, Stormy Weather was trailed to Cherbourg and then sailed to the UK to race there for a season. She took part in the RORC series in which she was 3rd in class and also won the Freddie Morgan Trophy for the first Classic Sailboat, and she raced in the Fastnet on the 80th anniversary of her initial triumph, “The RORC were superb in terms of getting the boat through the safety requirements,” said Christopher. Dorade was also taking part and these two boats spent about a day –

including the rounding of the Rock itself – just a few boat lengths apart, prompting Yachting World’s editor Elaine Bunting to write: “two elegant welterweights slugging it out in raw, troubled seas and sweeping rain.” Stormy Weather eventually lost out to Dorade but came 4th in IRC Class 4 and 11th overall.

Although Stormy Weather has had regular minor refits during Christopher’s ownership, last winter it was time for a more significant one. For this she was taken back to Cantiere Navale dell’Argentario where at least half a dozen people who had contributed to her 2000 refit worked on her again, including the head carpenter Piero Landini who was now 70 years old. The work was supervised by Tarquin Place who has been Stormy Weather’s captain since 2005. The ballast keel was removed and about half of the bronze keel bolts were replaced; about 25 linear metres of underwater planking, which was “getting a bit soft”, were replaced with African mahogany; all the fittings were removed from the spars which were stripped back to bare wood, and then benefited from plugged holes, new fastenings, some new fittings and a revarnish; and the rudder, which was waterlogged, was replaced by a new one designed by John Corby to the original profile, from Alaskan yellow cedar reinforced with stainless steel tangs.

On the day I was invited to sail on Stormy Weather at Regates Royale in Cannes there was to be disappointment in that we motored around for a few hours – with not a breath of wind, quite heavy rain and an uncomfortable swell – before the race committee officially cancelled the race. Nevertheless, it felt like a privilege to be aboard this historic yacht, with the words of Paul Adamthwaite ringing in my ears. “It isn’t just legend that Olin considered Stormy Weather to be his favourite design,” he said. “It is the truth. He wrote exactly that in a book that he gave me.”

18th -20th July 2025

From 18th -20th July, 2025

we will mark the 46th anniversary of the THAMES TRADITIONAL BOAT FESTIVAL with the biggest and best event yet!

The feedback from 2024’s “TRAD” was so immensely positive that we could be tempted to rest on our laurels. However, we know we can do better!

While the format and layout will be familiar, we will tweak and improve where we feel it is necessary. Admin will be even simpler, access for cars and visitors better marshalled, slight changes to catering facilities, more “posh loos”, more luxurious Members’ Enclosure: the long-promised on-site shop for essential supplies as well as a few new souvenirs.

When Lady McAlpine took the helm at the TRAD, using her Motor sport background she said: “Our aim is that if people see Henley Regatta as the “Festival of Speed”: the “TRAD” should be compared to the “Goodwood Revival Meeting.” Such a terrific gathering of beautiful old craft should be celebrated rather more loudly and publicly than it has been in the past: I would like to see an instant recognition of “The TRAD” among the public at large. At present, I’m afraid it is still too little known; even around Henley! If people are prepared to spend the time and effort involved in bringing their boats to the TRAD: they deserve a large and appreciative audience: and, of course, we need to show a younger generation the pleasures of messing about in old boats!”

So please book your boat in NOW: on-line. www.tradboatfestival.com

If you want to sell something to the 15,000 visitors we know we will get, and possibly more, please book a trade stand: booking is open on-line at www.tradboatfesitval.com

We have a few Premium spots for those who have beautiful boats to sell or just want to attract owners of beautiful boats. These can be booked by discussion with Sue via: exhibitors@tradboatfestival.com

Ticket sales are now open on-line too and we hope that a lot of you will want to join our supporters “Club”. Not only do you have use of the Members’ Enclosure with complimentary coffee or tea, dedicated bar, loos and food service but you will be invited to a Members’ party or two so that you feel part of the TRAD all year.

Like all such events, we are always trying to find SPONSORS.

We are lucky to have been supported by the Shanly Foundation for many years and others have come and gone. Hobbs Boatyard and GRUNDON are loyal sponsors “in kind” We feel we should have more Marine Trade sponsorship! Please try!

WORDS AND PHOTOS CLARE MCCOMB

The Royal Thames gathered at St Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge on 15 January for a service of blessing, including an inspiring sermon delivered by the Club chaplain, Canon Alan Gyle. ‘Eternal Father Strong to Save’ and ‘Jerusalem’ rang out to the roof beams: (Hubert Parry, composer of the latter’s tune, was a member.) Looking around, grey hair was everywhere, and I could not help wondering what marvellous stories all those seasoned sailors could tell, if they could be persuaded – what oceans they had crossed with the Blue Ensign fluttering, what adventures and near misses…

Back at the Clubhouse the bubbly flowed, thanks to event sponsor Nyetimber, as did the speeches. With 250 years to look back on, and a bright future ahead, there was much to celebrate. An antique painting, also from the founding year, had been sold to the Club that very afternoon (an o er which could not be refused), and was on display; as a brand new addition to the Club's famous collection it attracted considerable interest. Contributors to the new book commissioned for this major event mingled with the 150 present: it is a substantial volume incorporating much new research, approaching the Royal Thames’ history from six distinct angles, with a section on the Club treasures.

The newly commissioned cased models of the King's Fisher (owned by 18th century Commodore, Thomas Taylor), and half model of Cambria, with which the Royal Thames challenged for the first America’s Cup, were much admired; one example of the silver versions of King’s Fisher which are presented to each of the “superpatrons” whose generosity has done so much preserve the Royal Thames’s heritage this anniversary year, was held up for all to see. The wonderful and newly restored 18th century King’s Fisher flags, contemporary with the Club’s founding in 1775, draped with Sonar spinnakers, were unveiled by Olympic gold medallist and Club Cupbearer Iain Macdonald Smith, and there was much marvelling at them. They are the oldest such flags in the world – a unique treasure.

Later, at dinner, the food was, as always, delicious: I chose crab and cod loin with steamed spinach. Royal Thames editor, Richard Bundy, sitting opposite me, was stoically sticking to his “dry January”. We chatted on, freely, long into the evening. The traditions of such gatherings stretch back literally centuries – the Royal Thames is the oldest continuously operating yacht club in the United Kingdom, and 2025 will be celebrated on the water and o .

Now it is “ropes o for the Club’s passage through its 251st year” declares Head of Heritage, Andrew Collins.

1. Club members attend St Paul's Church, Knightsbridge for a service of blessing; 2. Event sponsor Nyetimber produced sparkling wine back at the clubhouse; 3. 18th Century flags on display belonging to club commodore Thomas Taylor (1780-1816); 4 & 5. Club members enjoying the hospitality and the Vice Commodore's speech; 6. A sail displaying the RTYC club burgee; 7 & 8. The celebration drinks were followed by dinner; 9. A brand new unsigned artwork bought by the club on the day of the event is believed to depict the Club’s first ever race in June 1775. In the foreground is a barge, presumably with the Duke of Cumberland on board, the Club's founder. Note the enormously enlarged Cumberland Cup on the roof of the cabin; 10. Specially commissioned cased model of Thomas Taylor's yacht King’s Fisher; 11. RTYC knows how to throw a party. Over 150 members were in

The Royal Ocean Racing Club, known to all as RORC, celebrates its centenary this year and will be marking the event in a number of ways, not least by holding a classics day in Cowes, Isle of Wight, on 19 July. The RORC is calling for yachts built in the first 50 years (1925-1975) and that have raced with RORC, to participate. The event will comprise a sail-past and salute for the

RORC followed by a short race (subject to sufficient interest), followed by a welcome of participating crews to the evening centenary party. Any yachts interested in participating are requested to email racing@rorc.org to register their interest (including whether they would participate in a short race) by 30 April 2025. For more regattas, see our events guide in this issue.

From 1957 to 2003 the RORC Admiral’s Cup was one of the most prestigious sailing contests in the world, competed for by national teams, and won the most times (nine) by Britain. This year it returns as part of the RORC’s centenary celebrations and will run, as it used to, biennially on odd years. The first race of the Admiral’s Cup series was, and will again be, the world-famous Fastnet Race, sailed, in those days, from Cowes (Isle of Wight) to the Fastnet rock off Ireland’s south coast, then back to Plymouth (Devon). Since 2021, the race has ended in Cherbourg instead of Plymouth.

The Fastnet will be celebrating its own centenary, as it was first raced in 1925, the year the RORC was founded. On 26 July, the overall winners from seven of the last eight races will be on the line, including Ran 2 (a rare double winner… 2009 and 2011) and Caro (defending champion).

The race has a rich history, most notably the tragic 1979 event in which 15 competitors died and 10 yachts were lost. It’s also known for the great yachts and famous sailors who have won it over the years. They include Rod Stephens (three wins – two on Dorade , one on Stormy Weather , of which more in next month’s issue), John Illingworth (two wins, both on Myth of Malham ), Eric Tabarly (a win for Pen Duick II ) and Ted Turner, who won aboard Tenacious in 1979. The race’s first ever winner was EG Martin on the legendary pilot cutter Jolie Brise in 1925. Martin and Jolie Brise went on to win in 1929 and 1930, making both skipper and boat the only triple winner in the race’s history. Another early winner was Tally Ho in 1927, recently and painstakingly restored by Leo Goolden, and about which you’ll be hearing a lot more in these pages.

There are usually a few classics in the 400-strong fleet, although registration seems to be akin to buying tickets to Glastonbury these days, such is the race’s draw.

The spirit-of-tradition yacht Oroton Drumfire has won her class in the 79th Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race for the second year running. Drumfire , a Truly Classic 78 model from the Hoek design office in the Netherlands, raced in PHS Class 1, in a field of 17 modern yachts. She was built in the Netherlands as an

ocean-going performance cruising yacht in 2007 and belongs to an Australian sailor. Dutch Olympic and Volvo Ocean Race sailor Carolijn Brouwer was part of the crew, as was Jessica Watson, the youngest sailor to circumnavigate the world.

Photo ROLEX/Carlo Borlenghi

Crafting Elegance, a new exhibition at the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine, celebrates the “golden age of Scottish yacht design” through its three most famous proponents, the families of Fife, Watson and Mylne. This trio made the West Coast ports of the River Clyde the cradle of maritime innovation in sailing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The exhibition, which runs until 25 May, illustrates how George Lennox Watson, Scotland’s first dedicated yacht designer, revolutionised the field by introducing scientific principles to what was once purely intuitive craft. The legacy of the Fife family, known as the ‘Wizards of Fairlie,’ is honoured for their mastery of design and craftsmanship, which set new standards in yacht building. And the remarkable journey of the Mylne dynasty is also on display,

whose designs graced waters from the Clyde to distant shores across the globe.”

At the heart of the exhibition are artefacts from the Mylne and GL Watson archives, including original drawings, models that and more, from yachts that raced in the America’s Cup to luxury vessels commissioned by European royalty and high society.

Interactive displays and compelling narratives show how these designers shaped the America’s Cup contests, from Watson’s pioneering designs for Thistle and the Valkyrie series to William Fife III’s creation of the legendary Shamrock challengers.

The exhibition also explores how the River Clyde’s unique geography and Scotland’s rich maritime heritage created the perfect conditions for these designers to flourish.

Designed by Knud Reimers and built by U a Fox in 1938, Waterwitch was the first 30-Square Metre to be built in the UK. This photo, showing several innovative features, appeared in The Yachtsman soon after she was launched. Reflecting on a growing class, they reported that “there are now 18 of them in the British Register, with five cups and prizes competed for in British waters.” Waterwitch ’s last entry in Lloyd’s Register of Yachts was in 1973.

The Association of Yachting Historians has digitised 92 volumes of The Yachtsman (1891-1940) and the complete Lloyd’s Registers of Yachts (1878-1980) and these can be bought on memory sticks. www.yachtinghistorians.org

Apologies to photographer Tyler Fields, who was not credited for his photos of the Rockport Marine-built yacht Mar Amore (Little Wolf 38) in last month’s issue. See tylerfieldsphotography.com. In the text, “African cedar” was mentioned in the build of the hull. This should have read “Alaskan cedar.”

FRIDAY 20TH JUNE - SUNDAY 22ND JUNE 2025

The main regatta will be a three-race series held over Saturday and Sunday in Dovercourt Bay, Harwich Harbour, and the Orwell and Stour estuaries. An optional early evening race will take place on Friday in which entrants will compete for separate prizes.

FRIDAY 20TH JUNE - SUNDAY 22ND JUNE 2025

The main regatta will be a three-race series held over Saturday and Sunday in Dovercourt Bay, Harwich Harbour, and the Orwell and Stour estuaries. An optional early evening race will take place on Friday in which entrants will compete for separate prizes.

Invitation to classic motor boats to join the weekend

Su olk Yacht Harbour presents the 23rd annual Invitation to classic motor boats to join the weekend

To enter online and for event details, visit www.syhclassicregatta.co.uk

To enter online and for event details, visit www.syhclassicregatta.co.uk

Entry forms via email or post can be requested from jonathan@syharbour.co.uk

Entry forms via email or post can be requested from jonathan@syharbour.co.uk

Now in her 10th decade, this little boat has defied the odds to remain afloat and in commission

In 1933, T Harrison Butler – the professional eye surgeon and amateur yacht designer – entered a design competition organised by The Little Ship Club. His entry was a 25ft 6in (7.7m) Bermudan cutter, the first of which was built in Hull the following year and named Bogle (after Butler’s daughter-in-law, the actress Joan Bogle Hickson who subsequently found fame playing Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple). Two years later, another boat to this design, but this time a Bermudan sloop, was built in pitch pine on oak by RJ Prior in Burnham-on-Crouch and was named Myfanwy She had a Stuart Turner 2-cylinder petrol engine and The Yachtsman reported that she “represents a compromise for a 6-tonner on a fifty-thirty basis, the thirty per cent belonging to the engine. She is a sailer first…The owner desired week-end comfort for two, and boldly decided to take the cabin top right across the ship. This arrangement not only slightly cheapened construction but in addition, provides full sitting head-room on bunks, strong construction and the elimination of the leaks between working decks and cabin top. The judicious handling of the rubbing strake and special cast ports have accentuated the shear and length and avoided the ‘boxy’ effect due to increased height of topsides.” The magazine’s correspondent also wrote that Mr Prior “undertook to build the craft to a first-class specification at a reasonable figure, and it is understood that he is prepared to keep the moulds until the end of the season, in case some reader may fall to this little lady.” Although no other boat to this class was ever built by Priors, it is thought that a total of six Bogles were produced by various other builders.

Myfanwy’s first owner was HWT Thatcher who kept her in Burnham and, it is thought, used her to take his new wife on a honeymoon cruise. At some point during the Second World War or immediately afterwards, she was sold to WJD Perkins and then in 1952 to WG Royse, both of whom also kept her in Burnham. In 1972 she was lying abandoned in the Belsize Boatyard in Southampton and facing an uncertain future, when the Domican family – Jim, Eugenia and their children Michael and Jennifer - found her there. They had previously spent a few years sailing their Elkins-built 24ft Withy “but my sister and I were getting bigger and the boat wasn’t,” Michael told me recently, “and there at Belsize was this magnificent much larger yacht.”

The previous owners – who seem to have left the boat “with all their possessions on board, including Admiralty charts of the Channel Islands and Mediterranean with pencil markings all over them, and dried up provisions in the larder” - were, apparently, not contactable, and so the Domicans effectively bought Myfanwy from the boatyard. They took her to Lymington where they kept her on a council mooring between two piles and for the next five summers they cruised – along with their border collie Bobbi - to the Isle of Wight and along the south coast of England. “Nothing really super adventurous, but great fun,” said Michael. But eventually Jennifer became less interested

Previous page: Saoirse is one of just six boats built to T Harrison Butler’s ‘Bogle’ design

Above: The full height cabin top extends the full width of the boat creating plenty of headroom but avoiding a ‘boxy’ look

Below: Chart table

and Michael went to university and became more involved in racing other boats (and went on to sail on Britain’s America’s Cup challenger Victory 83) and it was time to put Myfanwy on the market.

Her next owners were Mr and Mrs RW Parrott – “super people and very enthusiastic owners,” recalls Michael – who took Myfanwy to Portsmouth, changed her name to Cariad, replaced the original engine with an Arona diesel, and converted her to a cutter with the addition of a bowsprit. When Michael learned recently about the latter modification, he wasn’t in the least surprised as he had never understood why Myfanwy had had excessive weather helm given that Harrison Butler was renowned for being a strong advocate of the metacentric shelf theory to ensure his designs were well balanced.

There is some uncertainty about the boat’s history over the next few years but it seems that she was owned for a while by Keith Towne, had a major refit at Nash & Holden’s yard in Dartmouth, was converted back to a sloop (albeit retaining the bowsprit)and at some point

her name was changed back to Myfanwy. In 2002 she was purchased by Bernie and Pat Yendell (and for a short time John Fallows was their co-owner) who kept her in the Fal estuary. Bernie was a professional boatbuilder and during his five years of ownership he carried out a great deal of work to her. He replaced the rudder, two bulkheads, three deck beams, the forehatch carlins, the whole of the deck with two layers of epoxy sheathed ½in plywood, the toerails and rubbing strakes; fitted four new lodging knees; scarphed in a new 3ft section of stem; fitted twenty sister frames; installed a reconditioned Yanmar GM8 diesel engine; removed the iron floors under the engine and had them shotblasted and zinc sprayed before refitting them; rewired the whole boat and installed a solid fuel stove.

Myfanwy remained in Falmouth with her next owner, Paul Bidmead. Paul sailed her almost entirely singlehanded, and took part in the three local classics regattas – Falmouth, Fowey and Plymouth – “most years”. He took her to Cockwells to have new garboards fitted (in larch) and new bronze keel bolts.

Below: The interior looking forward

He told me that he was “never happy with the reconditioned engine as it sounded like a tank”. In 2014 Paul decided to buy another boat that had been restored by Bernie Yendell (Matanga, “a small pocket schooner”) and so he put Myfanwy on the market. She was then sold to Irishman Brian Redmond who kept her in Gillan Creek just to the south of the entrance to the Helford River and renamed her Saoirse. But sadly it wasn’t long before Brian began to suffer from poor health, as a result of which Saoirse lay neglected in a mud berth for several years.

Having founded the marine clothing company in his own name in the mid-1970s, in 2014 Nick Gill sold half of his shares and then finally retired in 2020. Living locally, he and his wife Caroline often walked along the shores of Gillan Creek and couldn’t help but notice Saoirse. “There’s a project,” he said at some point, to which Caroline said “well do something about it”. So he contacted the Sailaway St Anthony boatyard which administers the moorings, and was told that Saoirse would probably be for sale. One day at low tide he climbed aboard and, although he was pleasantly surprised to find that the planking seemed solid, he could see that she was “in a terrible state down below”. At some point she had lain on one side after a leg broke and there was silt all the way up the insides and everything, including the engine, had been submerged for some time. “Despite this I could see character and could imagine what she might look like,” he said.

So Nick then tried, with some difficulty, to find an expert to survey the boat, and eventually came across Clive Curnow, a retired shipwright who had worked for Falmouth Boat Co. “He had a look at her and said ‘she is a real mess, but seems pretty solid overall’,” said Nick.

So he contacted Brian who sadly couldn’t remember anything at all about Saoirse, but a good friend of his helped the transaction go through to allow Nick to take her on in May 2022. By that time she had been abandoned for at least five years.

Nick decided to take her to Gweek Boatyard to do the work. But to get her there he first needed to float her off on a high tide and then tow her round to the Helford River and leave her there overnight before taking her up the river on the next tide.

“We set up an electric bilge pump as it was a worry whether she would take in water,” said Nick, “but she seemed to be fine.” She was then lifted out of the water for the first time for seven years and the hard work began for Nick and for Clive who had agreed to help.

Firstly everything that could be was removed from the interior, and much of it went to the tip. The inside of the hull was pressure washed with the excess water pumped out through the heads – a Baby Blake which was salvaged but with renewed plumbing. The wood burning stove was very rusty

but was removed for sandblasting before being reinstalled. The engine was a write-off but was replaced by a new one of the same model. Other than that the work mostly consisted of a massive amount of scraping, sanding, painting and varnishing (with all the removable parts being done at Nick’s home), “but the more we scraped paint away, the more we unearthed more issues and the to-do list grew longer and longer,” said Nick.

In the autumn, Saoirse was moved into a rudimentary shed to give some shelter from the winter weather. In January, just as Nick’s morale was “already at a low ebb, as we had been working on her for six months with little sign of much progress,” the project suffered a major setback when Clive first contracted Covid and then deep vein thrombosis. “I think if someone had offered to take Saoirse off my hands at that point, I would have let her go,” said Nick. But Clive gradually recovered and the small team was also augmented occasionally by James Pardoe, a shipwright who was working on a neighbouring boat, and then they managed to make noticeable progress.

With regard to the rig, a new boom was needed –Ben Harris produced this, in spruce, but the mast was fine after everything was stripped off it, a few local repairs were made and eight coats of varnish applied. Although the stainless-steel standing rigging was in good condition, all the running rigging was renewed. By the summer of 2023, Saoirse’s hull was clearly drying out and so Nick and Clive were desperate to get her afloat. Eventually, she was relaunched in August and it wasn’t long before she took up. “Without Clive this wouldn’t ever have happened,” said Nick. “Although we did the work together, he was the brains and the brawn.”

Nick also owns a Southerly 42 and it so happens that he took her away for a month’s cruise as soon as Saoirse was launched but he began to sail the smaller boat as soon as he got back. “I had never sailed a long keeled, heavy displacement boat like this before,” he said, “and I was staggered at how well she performed.” He continued to sail her until the end of October when he was obliged to vacate his swinging mooring in the Helford River, and he laid her up afloat with a cover on her at Port Pendennis Marina. Then in the spring he had her lifted at Sailaway St Anthony and spent a month – “dodging the showers” – painting the topsides, antifouling and sound proofing the engine space.

After a month of weekend sailing, he entered her for Falmouth Classics for which he recruited Clive as crew, but that was when disaster struck. On the first day when it was already blowing quite hard, the competing boats were hit by a brief but ferocious 40-knot gust during the second race. This resulted in the sinking of a Falmouth Working Boat (happily she was successfully raised the next day) and the dismasting of four boats, one of which was Saoirse.

Understandably, Nick and Clive were devastated but since then Nick has taken a philosophical view and decided to take the opportunity to improve the rig. A new sail plan with a modified full-height genoa and a

DESIGN Dr T Harrison Butler

BUILD Priors, 1933

LOA 25ft 6in (7.8m)

LWL 22ft (6.7m)

BEAM 8ft (2.4m)

DRAUGHT 4ft 2in (1.3m)

DISPLACEMENT 6 tonnes

as “staggering”

Above: The new sail plan

shorter bowsprit was drawn up, dispensing with the inner forestay to allow easier tacking. Ben Harris was commissioned to make a new mast and bowsprit, and new sails were ordered from Falmouth-based SKB Sails. Saoirse was taken to Ben’s yard in Gweek so that the chainplates could be moved to suit the new rig, and it was while this work was being carried out that further issues came to light. Much of the plywood deck was found to be rotten, as were parts of deck beams, frame heads, the stem and the foredeck bulwarks. Ben and his team soon set to work to rectify all this and so, after these unfortunate, but temporary, setbacks, it won’t be long before a new and improved Saoirse will be back in action.

SALE, CHARTER & MANAGEMENT Also specialises in Transoceanic Charter

1968. Rebuilt 2019. TELSTAR VI is a classically designed, auxiliary ketch with all the character and style of the 1960s, but the luxurious comfort, amenities, and advantages of a modern yacht. Her strength and long range will provide endless enjoyment for local and world cruising. TELSTAR VI is carvel built of mahogany and oak. She underwent a substantial €13 Million refit in Malta from 2012 to 2019 where she was completely stripped out. Her all-new equipment also includes carbon spars. The extensive refit enables MCA coding.

1962. Refit 2022. Designed by the Scottish naval architects G.L. Watson & Co. and built along traditional lines to Lloyds class by Ailsa Shipbuilding, Scotland. She has a top speed of 11 knots and boasts a maximum range of 4,000 NM, thanks to her twin Gardner engines. She has cruised extensively in all latitudes including a circumnavigation. She was also a support vessel for the filming of Luc Besson’s Atlantis. Her interior has been rebuilt using varnished mahogany, in a timeless style, with modern details for comfort.

1914 Born from the drawing board of Herbert White and built by the Brothers Shipyard in Southampton (UK), despite her name – in recognition of her Kauri pine construction from New Zealand - KIWI was launched as an English gentleman’s yacht with an incomparable, but manageable size. A rare opportunity to own a beautifully vintage historic yacht, with authenticity yet practicality and an unmistakable aesthetic.

1983 WHITEFIN was designed by Californian Bruce King. The result is an exquisitely proportioned mix of agility, lightness, and grace. WHITEFIN was given a complete refitting in January 2020. The heart of life on board is the open-plan area in the widest part of the boat which includes the galley, partially recessed, the nav station, the bar, and the saloon with fireplace and piano. The boat consists of four cabins: the owner suite, all aft; the VIP guest cabin with a queen-sized bed and two twin guest cabins.

1998. Refit 2021. WINDWEAVER OF PENNINGTON is a solid, seaworthy, go-anywhere sailing yacht rigged as a ketch. She has a huge range including under engine with 2,500 NM to go at 8 knots cruising. Inside, she has a lovely, cosy interior which allows her to face all sorts of weather and climates. She can accommodate up to 8 guests and 3 crew.

Classic 20 DOLCE VITA

2004. Refit 2022. The hull and superstructure are made of wood, mixing traditional construction and design with the latest techniques. She truly resembles the timeless elegance of more traditional classic yachts. DOLCE VITA has been designed with enjoying comfortable holidays in mind, sailing peacefully, easily and safely. Her fuel range stretches to further extended coastal trips.

2023 Classic runabout replica from a François Camatte design (1926) with modern construction and equipment. Ideal for a day trip as well as suitable as a large yacht tender. Economical to use, and easy to run and maintain.

BY DAVE SELBY

Shaped like a gigantic soup-bowl, the Russian Imperial Navy’s revolutionary war ship turned out to be even more revolutionary than intended – it kept going round in circles. But that was only one of the foibles of the 1874 round-hulled, 101ft-diameter (30.8m) iron-clad that was intended as a formidable gun platform. With its 18in (46cm) freeboard and minimal draft, designed to present a minimal target, the heavily armoured Novgorod was as wayward as a soap dish and swamped just as easily in any sort of seaway. In “pursuit” mode the Novgorod could manage all of 6.5 knots in flat water, despite being powered by six massive steam engines driving six propellers, which at full chat consumed 200

There’s a long line of sailing US presidents, from Abraham Lincoln to John F Kennedy. One-time ferryman Lincoln is the only one to hold a patent – for an external buoyancy device to raise boats over shoals. War-time naval hero JFK took respite from responsibilities in a string of yachts, but lesser known is the passion of Grover Cleveland, twice president from 1885 to 1897.

Cleveland, a man of modest tastes, was equally modest on the water, taking his pleasure at his Cape Cod summer home in a cat boat, the beamy, gaff-rigged boats derived from working craft. A rare find is this half model of Cleveland’s boat (estimate $700-1,000), which reveals a man of simple tastes, and of whom it was said: “He is immoderate in only two things – his desk work and his fishing.”

tons of coal per hour. With little to no grip on the water the unwieldy white elephant took 40-45 minutes to turn full circle, and on the rare occasions when the Novgorod managed to line up a target the recoil from the massive guns sent her into a dizzy spin. A contemporary report of a sea trial noted that the Novgorod “whirled helplessly round and round, every soul on board helplessly incapacitated by vertigo.”

Scrapped in 1911, the failed experiment fully deserved its place of honour in the book, The World’s Worst Warships . The model (top right) of the Novgorod made £496 at Charles Miller Ltd, whose next London marine sale takes place on 29 April.

With not a single life lost among a crew of 28, the story of Ernest Shackleton’s 1916 small boat voyage to South Georgia and rescue of those left behind on Elephant Island is an epic feat of survival and leadership.

Yet the polar adventurer had another talent – for publicity –and even before he made it back to Britain his sponsor Bovril was making capital with a jokey ad that read: “Bovril & penguins – the staple sustenance of Shackleton’s men on Elephant Island.”

How much Bovril meat paste the men ate in their four months awaiting rescue is open to question, but they certainly devoured a lot of penguins. Apparently, they taste a bit like chicken.

The advert also went down well in the sale room, making a lipsmacking £2,000.

There’s this shackle that keeps me awake at night, or rather used to. A hefty shackle, and moused –but I’ll come to that later. I won’t be alone in having shackles on my mind: the singlehander whose forestay relies on one, scanning the masthead as a storm approaches, with a pair of binoculars, knowing they really should haul themselves aloft and check. In their mind’s eye they can see hands on a wrench, giving the pin a last twist, before threading the monel through the eye. Or had they made that up? The coil had been down to its last inch, that they can remember. No, they’d asked a guy at the yard to do it, and had been assured that it had been done. Yet still they can’t be totally sure. It’ll be fine, won’t it?

My shackle is 40ft under the sea. I can’t see it, even with binoculars. The ground chain – which I have no issues with, is good for a battleship, or at least the trawler that laid it five years ago. No, it’s the shackle that connects the ground chain to what we call the scrub chain, the 3m or so of chain designed to take the chafe as the yacht veers in the current, which is in turn shackled to the heavy Sea steel riser.

That’s fine; I can see most of it at dead low springs, even to the top shackle which I know is good, because I fitted, tightened and moused it myself using heavy coated wire. Tantalisingly close, but lower lies that shackle, the one that kept me awake during last year’s winter storms.

“Out in the Minch it was very, very windy, ferry cancelled, small fishing boats tied up”

All was well, as it turned out; my fretting was needless, and yet, how much sounder would I have slept if there had been a camera focused on that shackle. How would it have recorded the movement, the abrasion, the corrosion? The thing is, I didn’t dive the shackle, grind out the bar in the ground link and fit the shackle. I only have the word of whoever did it. But that’s not the same as doing it yourself. Besides, then you have no one but yourself to blame, which is scant comfort when you drive to the opposite side of the loch to where she’s lying, or was lying, to find she’s gone.

One aluminium yacht in the bay did break free, and was found miraculously poised, her keel wedged between two rocks, high and dry when the tide fell. Some yachts save themselves, find the only soft patch in a shoreline of boulders. Others seem intent on self destruction, generally those that have been neglected, but not always. In January we had a storm, not the first that winter, or the worst. When the south has a strong gale, they call it a storm and don’t the journalists love a storm. “Who wants to take a pool car to the promenade, and talk to camera? Pick up a Musto jacket from the newsroom cupboard and get down there. Make it sound dramatic. Look windswept” (despite the absence of serious waves in the background.) Getting wet and tousled will add to the effect. Ideally a deck chair, or failing that a bit of a sign can be induced to fly past. Like adding a child’s doll to a scene of devastation in a refugee camp.

Here it was just very windy. Out in The Minch it was very, very windy, ferry cancelled, small fishing boats tied up. And Sally ashore, not as in blown ashore, but as in propped up at the yard, braced fore and aft, side to side, tucked in out of the weather, cockpit cover on, sails stowed. And me sleeping peacefully as the slates rattled, no visions of shackle pins unscrewing, or strands unravelling, let alone boats upwind breaking free and dragging both to a lee shore, as has happened in the anchorage when a mussel barge fled from its mooring and collected a small yacht on its way east, the yacht fetching up on a beach, the barge stranded and now a rusting, holed hulk, days of carnage over.

As for that shackle, the one I used to agonise over, on inspection it was found the pin had worked loose, and the mousing, far from being monel, or heavy coated galvanised wire, was just a cable tie. There might have been a couple. But still…

2 Southford Road, Dartmouth, South Devon TQ6 9QS Tel/Fax: (01803) 833899 – info@woodenships.co.uk – www.woodenships.co.uk

32’ Lyle Hess Gaff Cutter built in Malaysia in 1991 from Chengal, a very durable tropical hardwood. New deck, interior and systems in 2007. Complete new gaff rig in 2018. 5 berths including double cabin forward. 6’2” headroom. Professionally maintained yacht with lovely lines set off perfectly with her recent gaff rig.

Wales £68,000

34’ Bermudan Cutter designed and built by her professional shipwright owner to German Lloyds standards, launched in 2015. Finished to a very high level and maintained to the same exacting standards. Cruised from Norway to the Med. 4 berths in a stunning interior. A very classy and elegant spirit of tradition yacht.

Germany €208,000

18’ Nick Smith Clinker Motor Launch launched in 2021. Planked in mahogany all copper rivet fastened to steam bent oak timbers. Beta 14hp diesel. Open boat with no fore or aft decks maximizing the inside volume. Beautifully yet simply finished. Used gently for 2 seasons only. Complete with fitted cover and road trailer.

Devon £34,000

46’ Fred Shepherd Bermudan Cutter built in 1903 on the IOW. Major rebuild finished in 2004 including significant hull repairs, new deck and interior. Sailed around the Irish Sea with gentle cruising then laid up for the last few years, sensibly priced taking into account the commissioning work that will be required.

Wales £38,000

28’ GRP Gaff Cutter designed by Percy Dalton and built by Cygnus Marine in 1979. Heavy duty hull built to Whitefish Standards based on a Falmouth working boat. Teak decks and coachroof. New rigging and Beta engine in 2022. 4 berths with 6’ headroom. Pretty boat with exceptional sailing qualities and a traditional look.

Devon £29,000

28’ Yachting World Seahorse designed by Van De Stadt and built in 1974. Refitted and used for classic regatta racing in recent years, she can be set up as either gaff or bermudan rig. In her gaff rigged guise she is a real bandit racer for classic regattas. Vire inboard petrol engine. Twin axle road trailer.

Hants £12,000

36’ 12 ton Hillyard launched in 1961. Perhaps the most practical size of yacht ever built by Hillyards. Major refit 2018-2021, full surveys available. Well presented, very well equipped and ready to go cruising. Incredible value for money given the quality of the boat with lots of comfortable live aboard space and volume.

Kent £25,000

62’ Steel Gaff Cutter launched in 2017. Professional build designed by Mylne Classic Yacht Design based on the Lowestoft sailing drifters. Voluminous interior with 8 berths and 2.1m headroom. Steyr diesel with hydraulics and twin props. Cruised extensively around the Baltic since launch and now well proven.

Sweden €275,000

An engaging, humour-filled conversation… about insurance! Steffan Meyric Hughes talks to Simon Hedley, head of commercial partnerships at Pantaenius UK

It’s hardly the first subject people want to talk about. Underwriters, brokers, risk, death, destruction, disputes and confusion might be the first things that spring to mind. The marine world seems to have a great humanising influence on all things though, and it seems that insurance – at least the way Pantaenius does it – is no exception. “We don’t have any chat bots or automated phone systems” says Simon. “When you phone us, someone who actually knows boats will pick up after a few rings.” In today’s world, that’s reason enough to sign up; in fact a few Pantaenius customers have signed up just on the strength of that. This is doubly important for owners of old, wooden boats – that’s you perhaps, dear reader. You might not know the year of build, the builder, or the designer, which makes filling in online forms a kind of hell without recourse to that phone line and the human at the end of it. Pantaenius, although one of the biggest names in marine leisure insurance, is still a family firm, owned by the German Baum family, since 1970 having been founded in 1899. The name, in case you’re wondering, is not the Greek god of broken skin fittings, but simply the surname of the original founder. They’ve been in UK leisure boat insurance for 35 years now and have been expanding in the last five years into one-off and classic boats. This involved some light sponsorship of British Classic Week last year (the British Classic Yacht Club annual bash) and sponsorship at the Spirit Yachts Regatta in Guernsey. It’s part and parcel of the sailing life Simon has always known, from his first forays sailing aged four on the Isle of Wight, on Optimists and the venerable roto-moulded Toppers, later Wayfarers; the classic progression for a certain age group (Simon is 54). “My first boat was a plywood Oppie” he remembers. “We had some brown paint in the garage, so that’s what we used, and the boat ended up being named Hot Chocolate.” He spent his 20s racing with a friend of the family on a mahogany, cold-moulded, varnished half-tonner called Pinball Wizard, presumable named after The Who’s 1969 hit single (Pete Townsend is a classic boat owner today) and various other yachts during this prolific time of yacht racing –“Being able to make a half-decent cup of coffee and doing what you were told was enough to crew” Simon remembers. “You started at the pointy end and worked your way back with experience.” It was a classic Cowes upbringing: Simon’s classmates included the sons of rigging and spar-making legend Harry Spencer, and his first job after school was as a marine joiner at Souters, having got the bug from his grandfather, whose retirement jobs included repairs to Frank Beken’s big, wooden, plate-glass camera, and making the miniature rocking chair trophy for the Island Sailing Club. One memorable incident came at the America’s Cup Jubilee in 2001, when the Mylne yacht The Blue Peter broke her boom and Simon helped fashioned a new, temporary boom from an old telegraph pole to get owner Matt Barker and crew out racing again the next day. “We did a load of work on [Herreshoff schooner] Mariette. The owner Tom Perkins turned up at Spencer Thetis Wharf in a McLaren F1 and took us for a sail. That’s when I really got the bug for classics. He was an amazingly kind, humble man for all his wealth, and he was the

first I heard describe himself as a custodian rather than an owner. Everyone says it now, but perhaps he was the first? Anyway, it made a real impression on me at the time!”

After nearly 20 years insurance broking, there followed a long spell in running marine events, before Simon moved back into yacht insurance, the last four years of which have been at Pantaenius. “I was tempted back into having a proper job by the quality of the company,” he said. And it certainly seems like a happy place to work. There’s the travel, the friendships, the chats (“some people phone for a restaurant recommendation in Cowes or English Harbour in Antigua!”) and the never-ending fascination with people’s motivations. Simon tells of one client who keeps a yacht as a moveable office and sails off to warmer climes to work in English winter months, for instance. Experience of this sort is vital when it comes to assessing risk, which is done on a bespoke basis. “It’s different to house, car and pet insurance” Simon points out. “Most people live in a house, drive a car and have had experience of a pet, after all.” I give Simon a marine equivalent scenario to the “17-yearold insures super car in central London” scenario and discover that the company would not insure a weekend dinghy sailor to circumnavigate the globe south of the capes in a leaky Folkboat single-handed; but that’s not necessarily because of a lack of qualification. A recent example was a relatively unskilled sailor who turned out to be a helicopter pilot, so he was considered insurable. Generally speaking, the attitude at Pantaenius seems to be one of inclusion; the company sponsor all kinds of barrier-free boating, including The Wetwheels Foundation (for wheelchair users among others), the Disabled Sailing Association in Torbay and more. Of course, you might say, it makes sense to encourage sailing as a sport when it’s your lifeblood to insure it, but actually, the genuine desire goes hand in hand with the commercial imperative. And, Simon says, the need to encourage and include goes for all of us in the marine world, in whatever capacity. Even my fictional Captain Calamity of the leaky Folkboat and the grand ideas would not necessarily be turned down flat. He might be given limited cover initially: daytime only and a limited area, for instance. And stopping the leaks wouldn’t be a bad idea.

And what about acts of God, you might wonder? Among the more than 100,000 boats Pantaenius insures around the world, are those that get struck by lightning in far-off places, an occurrence that has woken Simon a few times over the years, when he’s been manning the 24-hour emergency claim line. “It’s a bit of a red herring, this ‘acts of God’ thing” says Simon. “Storms are acts of God too, as are orca strikes. And we insure for these causes.” The high number and spread of insured boats means there are enough policy holders to share the costs evenly, without too much volatility in the cost of the insurance. So sailors around the world will share the load of the victim of storm or terrible creature, just as those sailors will be there to pay out for the English yachtsman who runs aground in fog on a calm day. You could see insurance as a benign form of gambling (some see a lack of insurance as a sort of gamble too), or you might just see it as a necessary chore. But at its heart, all insurance, when it’s fair and working well, is simply a formalisation of the fellowship of the sea.

The brand new Rustler 41 is a reminder that performance has always been part of the marque

WORDS NIC COMPTON

Rustler Yachts has developed a global reputation for building a long line of comfortable sailing yachts which err towards the comfortable and traditional, rather than the new and trendy. Its current range includes six sailing yachts, ranging from a 24ft dayboat to a 57ft world cruiser – although to some they will still be best remembered for building the indomitable Rustler 36, which finished in first, second and third place in the 2018 Golden Globe round-theworld race.

With that kind of record, the company might have been forgiven for resting on its laurels and sticking to building sailing yachts. But, with many of their loyal clients reaching an age when they would prefer to press a throttle rather than grind a winch, there was a steady clamour for a Rustler motorboat. But what exactly would that look like?

To an outsider, the obvious route might have been a traditionally-styled semi-displacement yacht, in the vein of Dale Yachts in Wales and Cockwells in Cornwall. But company directors Adrian Jones and Nick Offord had other ideas. For 15 years they batted the idea around, first considering a 37ft design by their in-house designer Stephen Jones and then a 45ft long-andnarrow design by Ed Burnett and Nigel Irens. Neither was quite right. Eventually they approached Tony Castro, better known for his range of swanky superyachts and modern sailing yachts than classic motor launches but who nevertheless described their proposal as “delicious”.

The design he came up with is an interesting mix of old and new. It combines an essentially modern hull shape – far more modern than those retro semidisplacement boats that have become ubiquitous on both sides of the Atlantic – with traditional styling and a rather unfashionable concern with seaworthiness. It’s a surprisingly contemporary look from one of the last bastions of traditional yacht design, until you remember the other key feature of Rustler Yachts: performance. Just as Rustler sailing boats are a bit faster than you might expect (not by chance did they sweep the board of that Golden Globe Race), so its motor boat needed to perform exceptionally well.

“We asked our clients what they wanted,” says Adrian. “And they said they wanted comfort and seaworthiness, but also efficiency. We approached Castro with a set of performance figures and he said he could do it if we built the boat under a certain weight. We weighed everything before it went in and weighed each corner of the boat all way through, so we have a map of the weight and the weight distribution.”

The result is a boat with a displacement of 11,000kg, which rises to the plane at 18 knots and has a maximum speed of 35 knots. Fuel consumption at 23 knots is around 75 litres per hour, giving the boat a range of more than 400 miles. By contrast, a more traditional semi-displacement hull, such as a Hardy 42, displaces 14,000kg and at 24 knots consumes about 180 litres per hour.

“We’re not reinventing wheel – it’s all been done

Previous page:

The varnished teak capping rail glints in the sun – a classic touch

before,” says Adrian. “But the configuration that Castro and CJR Propulsion came up with, with the engines quite far forward, combined with a pair of small, light and well-packaged engines, has created this quiet, efficient thing. We could have used a Z-drive and put an extra cabin down there, but that’s not what we do. We want to produce something an owner could walk up to proudly and say, ‘That’s my boat.’”

During a rare lull in the bad weather last November, I went down to Mylor Harbour to see the new Rustler 41 for myself. The phrase ‘a wolf in sheep’s clothing’ immediately sprang to my mind, as the yard have done a great job of disguising that efficient, modern hull form with a lot of well-crafted joinery – not least the distinctive varnished capping rail, laminated from sustainably managed teak, which catches the eye immediately. It’s a look designed to appeal to the heart first and the brain second.

On board, the immediate impression is of an ergonomic space, with a large uncluttered aft deck providing a focal point for activities. The back end of the saloon / galley opens up to create a sociable area, with comfortable seating aft – though I’d be tempted to add a small drinks table on either side. The aft gate opens onto the obligatory swimming platform, with huge storage lockers on either side for all those water toys, as well as fenders and lines. Moving forward, the deep bulwarks give a feeling of safety on the side decks, while a gate on each side of the boat gives easy access to the dock.

Inside, there’s a comfortable saloon area to port, with C-seating opposite a well-appointed galley to starboard. Forward of the galley is a double helm position, with all the necessary nav gear and a large, full-width sunroof overhead. Down a few steps, there’s a large double owner’s cabin forward with triple overhead skylights, and a surprisingly large guest cabin to port. Opposite that is the heads, with separate shower compartment and, hidden behind a watertight door, a control compartment, where all the electronic gismos are kept safely away from the engines. The interior is beautifully fitted out using walnut and walnut-faced plywood – although the owner of the next boat has specified pale oak, which would give a slightly airier feel.

All in all, everything flows together nicely and it’s easy to imagine a family and friends enjoying themselves here. The Rustler 41 is nothing if not a sociable boat.

As for the power drive, Adrian lifted a hatch in the aft deck to reveal the two 370hp Yanmar engines, which really are placed quite far forward – effectively under the sliding door to the saloon. That leaves a large amount of relatively empty space aft, giving easy access to propeller shafts, rudders etc.

Owner Peter Harvey was on board, so I was able to quiz him on what inspired him to take the plunge and commission Rustler Yachts’ very first motorboat. It turns out that he is a serial Rustler owner, having previously bought three new Rustler sailing yachts. The

Clockwise from above left: Modern, gleaming fittings on a classic capping rail; The wide open aft deck is sociable; A fully equipped dash at the helm; The electrics and electronics nerve centre is separate from the engine room; Walnut faced ply adorns the master cabin in the bow; Twin five-blade shaft-drive props provide a top speed of 35 knots; Natural light, easy access and good all-round views in the galley/dining area, which connects the helm and the aft seating areas

first was a Rustler 42 he acquired in 2010, on which he competed in the AZAB (Azores and Back Race) and cruised extensively as far afield as Spain and Scotland. In 2018, he and his wife decided they wanted to spend more time at home and down-sized to a Rustler 33. By then, the couple had bought a 27ft motor launch (along with various land and air vehicles) and decided they were “over-toyed”, so they downsized even further to a Rustler 24. Meanwhile, the motorboat was replaced with a 38-footer.

“The sailing boats were getting smaller,” Peter says, “and the motorboats getting bigger.”

Peter matched exactly the customer profile Adrian and Nick had in mind when they decided to add a motorboat to the company’s range: a loyal customer transitioning from sail to power. Peter’s reasons for swapping his old motorboat for a new one also struck a chord: “The old boat had old technology and much thirstier engines, so it was more expensive to maintain and keep going.” But there was more to it than economy and comfort: the Rustler 41 also offered the family different kinds of boating.

“The beauty of living in this part of the world is that you don’t have to go far to get away from the crowds,” says Peter. “My son and my grandson came down at half term, and we went all the way to Helford for lunch, then all the way up the river to Malpas to spend the night. My grandson is six and he thought it was the best adventure in the world. On the other hand, the boat cruises at 20-25 knots comfortably, so if you get a flat calm day like today, you can go to the Scillies for lunch – and L’Aber Wrac’h is only four hours away.”

Scillies for lunch? L’Aber Wrac’h only four hours away? Now that puts a whole different spin on this motorboating malarkey, doesn’t it? Suddenly, I was raring to go.

Perhaps surprisingly, the speed limit on the Carrick Roads is 30 knots, so as soon as we were clear of the moorings, Peter handed the helm over to me and, slightly apprehensively, I opened up the throttles. My

Above: The Rustler 41 was designed and built with strict weight limits to aid performance, getting up on the plane at 18 knots

experience of motorboating is mostly limited to the 48ft classic motor yacht I grew up on in the Med and bombing around on small speedboats, either as crew on large yachts or as a passenger on camera boats, so I wasn’t quite sure what to expect.

In fact, the transition from semi-displacement mode (ie under 12 knots) to planning mode (designed to be at 18 knots, though it felt like it might come a bit sooner) was remarkably smooth. That’s because of the placement of the engines, which means the boat comes on the plane sooner, while the shaft drive gives a smoother ride. Soon, we were cruising along effortlessly at 25 knots. It was certainly a lot quieter than most motorboats I’ve been on – to the extent that there was no need to raise your voice to have a conversation. It wasn’t difficult to imagine carrying on like this for four hours and, et voilà, we’d be in France!

It was probably just as well we all needed to be home that evening, however, as once we got out from under the lee of St Anthony Head a big easterly swell soon quelled such fanciful notions. I eased the throttle back to 15 knots and pointed the boat straight into the waves. The spray was spectacular, leaping from one end of the boat to the other, but there was none of the slamming that so many planing boats suffer from. Turning away from the waves, with the wind on her quarter, the motion was much more comfortable, though even then you wouldn’t necessarily want to do that for four hours. Our trip to L’Aber Wrac’h would have to wait for another day.

Back in the shelter of the Carrick Roads, we opened up the throttle for one last blast, reaching 29 knots at 2,700rpm. We then eased back to a comfortable 8 knots and headed back into harbour. I’m not about to give up my sailing boat, but I could see that you could have a lot of fun on this boat with a clutch of children, grandchildren and friends. And when your wine rack is empty, it would be a quick trip across the Channel to top up your supply of vin rouge

What’s not to like?

The 8-Metre class revels in its traditional Scottish waters, embracing new designs with a focus on youth

WORDS DAVID SMITH

PHOTOS JAMES ROBERTSON TAYLOR

The 8-Metre World Cup 2024 was held 17-24 August in Helensburgh, Scotland under the auspices of the historic Royal Northern and Clyde Yacht Club and Mudhook YC. Thirteen yachts from Switzerland, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, UK and even a team from Canada had a windy and wild week of racing and perhaps an even wilder week of social events.

The Class is noted for its dedication to sailing perhaps the world’s most beautiful and affordable boats, in outstanding locations offering opportunities to take families and friends along and still compete at the highest level. The Clyde event proved no exception and competitors found out why the history of Eight racing runs deep in this area. The waters of the Clyde near Glasgow are the home of the great William Fife dynasty of yacht designers and the boatyards around its shores are where many of the competing yachts were built. Silvers yard at Rosneath just 1km away from RNCYC is also next to the site of McGruers yard, and around the local coastline you can find names from the past including Robertsons at Sandbank in the Holy Loch, Milne’s yard and of course Fairlie where the Fife yard was based.

So the return to the Clyde of Fife-designed yachts

Above & above right: Neptune

Class 8-M yachts enjoying some challenging conditions

Below: No holding back despite gusts of 30 knots

Below right: And no holding back at the ceilidh evening either

Saskia, Severn, Carron II, Falcon and Fulmar was a sight to behold and a great opportunity to imagine the races of almost 100 years ago when the class was developing and trialling new designs and shapes, and pushing the boundaries.

The Neptune Class prevailed in terms of providing eight of the entrants. These are the more traditionallooking boats typically with 100-year-old wooden hulls and classic white sails including spinnakers. The line-up of Fife boats’ bow dragons made visiting mouths water and hopefully will bring more enthusiasts into the redeveloping Clyde fleet.

The racing was extreme with 20-knot winds, gusting 30 knots, every day. The fact that these conditions were accompanied by driving rain didn’t seem to deter the teams who were out in enthusiastic form for every day and every race. It is true that the number of thermals bought in mid-summer from the local chandlers was a surprise to us all, but the dedicated Eight teams definitely were up for six days of hard racing.

The two Modern Class Eights of Yquem 2 and the old Yquem 1, now renamed Spirit, were ready for a fight. Jean Fabre previously owned both boats and was

keen to see how the new owners, Richard and Stuart Urquhart’, had prepared the boat in the short time since bringing her across from Canada. With new sails and a new mast this was a steep learning curve.

A great initiative proposed and supported by the 8-Metre Class Association (IEMA) was to sponsor a youth team. The very kind and generous owners of Athena, the Earl of Cork and Orrery and David Parsons, offered this 1939 Tor Holm designed boat for use by a suitable team. The Etobicoke Yacht Club from Canada rapidly found some regular 8-M sailors who are also sailing instructors with a high level of competence, to crew the boat. They excelled in their ability to master the boat in only a couple of days before the event and safely and successfully compete throughout the regatta. Hopefully IEMA can repeat this opportunity in other World Cup events around the globe.

The social events will be a hard act for any future host clubs to follow. The week started with a civic reception in the historic town hall, then teams were invited to a seafood extravaganza serving Scotland’s excellent shellfish, a whisky tasting hosted by the

Below right: Paolo Manzoni’s team Vision won four of the remaining six awards

Urquhart brothers of Benromach whisky and of 8-Metre yacht Spirit (aptly named), a mini-highland games with caber tossing, and finally a Scottish night with haggis, bagpipes and highland dancing. The success and feeling of the week was totally embraced by the class and the more than 50 volunteers who helped make it all happen.

Yquem II won the World Cup; Vision won four of the remaining trophies; the Corinthian Cup was won deservedly by the Canadian youth team on Athena, while Njord of Cowes took the First Rule Cup.

World Cup Yquem II, Jean Fabre & Société Nautique de Genève

Sira Cup Vision KC3, Paulo Manzoni

Neptune Trophy Vision KC3, Paulo Manzoni

Coppa d’Italia Vision KC3, Paulo Manzoni

Generations Trophy Vision KC3, Paulo Manzoni

Corinthian Trophy Athena K36, Etobicoke Yacht Club Youth Team

First Rule Cup Njord of Cowes K13, Jason Fry

The classic sailing scene continues to prosper around the established centres of the Solent, East Coast, West Country and further. This summer sees the return of the 8-M Worlds, a revamped British Classic Week and a new Channel sailing series, as well as the usual line-up.

17-18 MAY

Cowes Spring Classics Cowes, Isle of Wight (IOW), cowesspringclassics.com

Broad-church regatta, sail and power

23-26 MAY

Yarmouth Gaffers Festival oga.org.uk. Flagship OGA bash IOW

30 MAY – 2 JUNE