This

This

Anita Nowinska found her long-forgotten box of pastels while rummaging through a battered suitcase, using only a candle for light as her power was cut out. “By candlelight I created my first flower painting,” she recalls. “As I painted, I found the deep distress, sadness and pain I was feeling disappear.” That single act, she says, “saved me; healed me and gave me a sense of purpose.”

It was not, as she puts it, the straightest of career paths. As a precocious eight-year-old, Anita was invited to study alongside a master’s group under the Polish painter Marian Bogusz-Szyszko. “It wouldn’t be allowed these days,” she says, “eight grown men and an eight-year-old girl!” Her mother, indulgent, bought her oil paints and an easel; her father, less so, frequently destroyed her work. Later, Anita swapped paints for the fast money of dotcomera headhunting. “It gave me a very nice lifestyle financially,” she says, “but it was soul destroying.”

“It was Margaret Thatcher’s time, and success meant building a big career.” Anita’s art fell to the side as she ran a recruitment business in the emerging internet and e-commerce sector, but she doesn’t remember being happy throughout those years. During the dot-com crash, most of her clients went bust and although she kept paying out of pocket, she eventually lost everything; her business, home, partner, health and many friends.

Today, she is known for her vast, immersive canvases of meadows, wild grasses and blossoms – paintings that ask you to stop, breathe and look. “I want the viewer to see what I see. That the smallest thing in nature has so much beauty and wonder.” Scale matters: she paints big because she wants you to feel enveloped, caught in the shimmer of dew or the flicker of a slight breeze.

Art, for Anita, is a celebration of biophilia – our primal link to nature. “Walking through the hedgerows is my meditation,” she says. “These days we call it mindfulness, but for me it’s just immersing myself in wonder.” Viewers seem to agree. One woman in a wheelchair once sat with Anita’s work for three hours, later confessing it was the first time in 20 years she had felt no pain.

That, for Anita, is the point. “I can’t teach you how to paint,” she shrugs. “I can only teach you how to look.” And her latest series, See Me I Bloom carries that lesson into womanhood itself: “It’s about women truly valuing themselves – their strength, their wisdom, their determination. We create and nurture life – what could be more important?” britishartclub.co.uk/profile/anitanowinska ▫

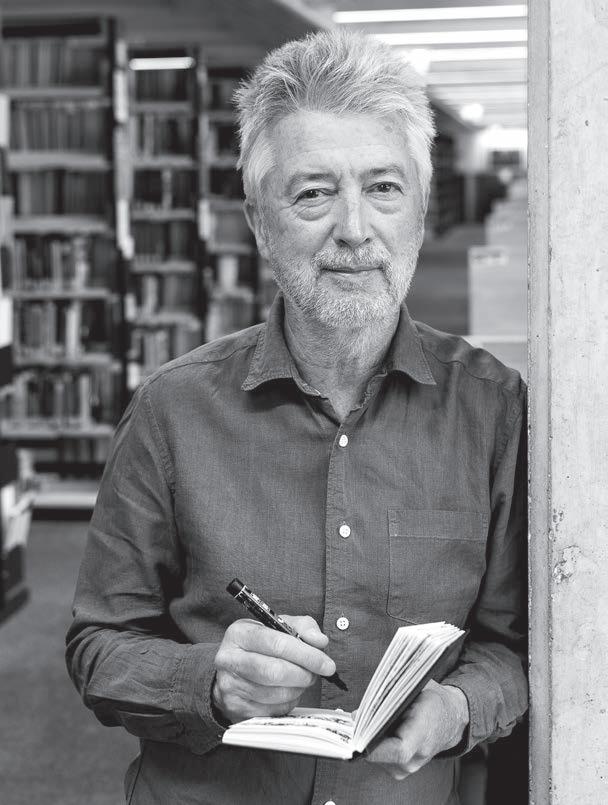

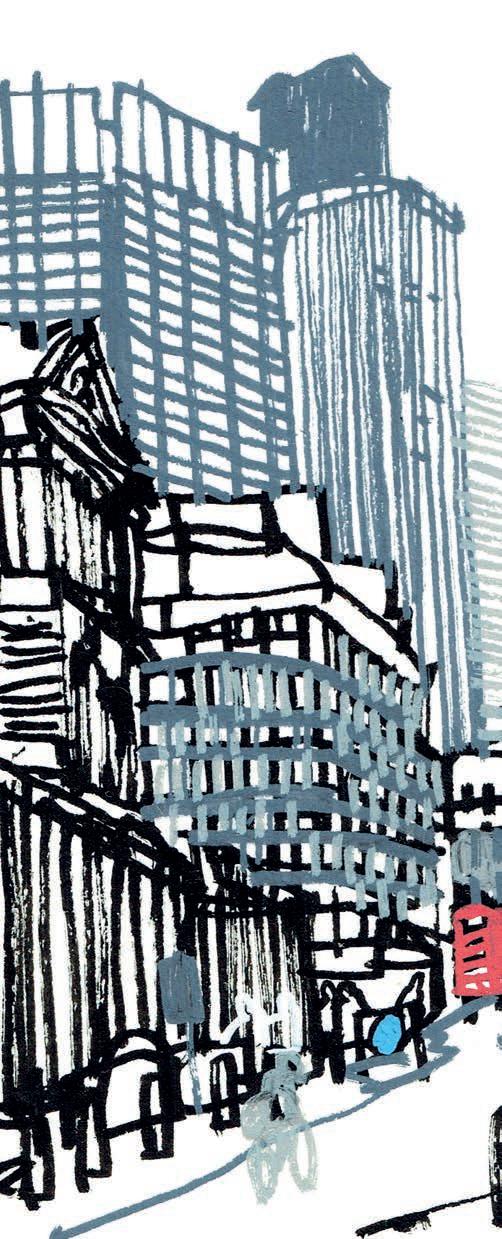

A former editor of Artists & Illustrators , JAMES HOBBS is now a prolific sketchbook artist and successful author, unbound by precision and perfection, finds Niki Browes

It’s not often you get to interview a past editor of this very magazine but James Hobbs – author, artist and former journalist – was just that. “I did a BA in Fine Art at Winchester School of Art and there was a writer-in-residence, the late novelist Grace Ingoldby. Through her, I soon knew that the written word was as important to me as visual imagery. After I’d written my first (unpublished) book, I trained as a journalist and for more than 20 years I worked in art magazines and newspapers alongside making my own art.” But with a growing family and busy job, his drawing work took a back seat.

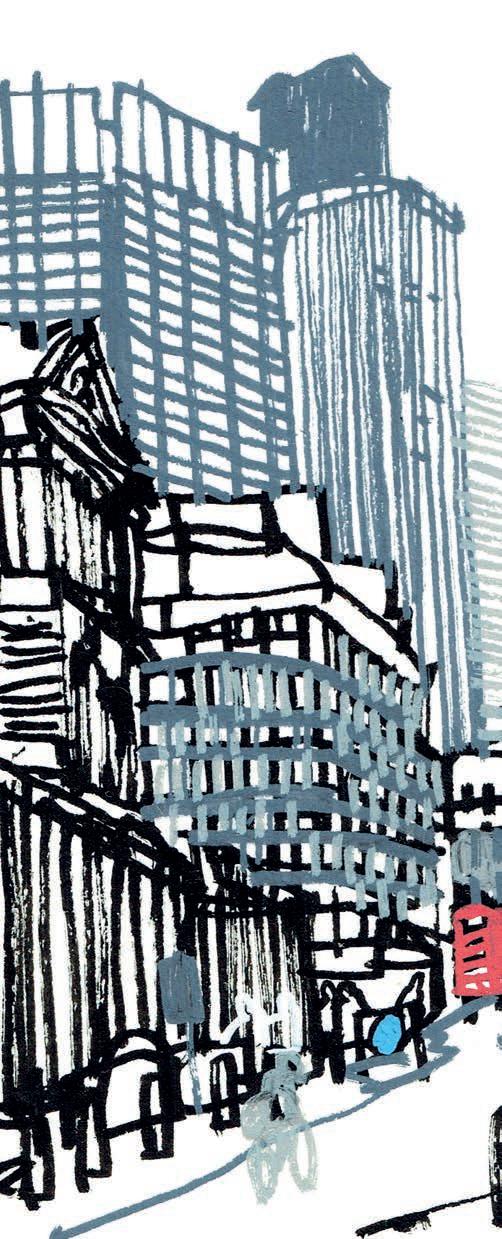

“I worked at Artists & Illustrators magazine for about seven years, ending up as editor (until 2004),” he explains. “It was a full-on, exciting time, working with a great team for a friendly readership. But my drawing slipped. I have a sketchbook from this time filled with hasty drawings of stuff on my desk, such as staplers, PC equipment and telephones.” Yet, it’s mainly the city and urban life that pulls him in. “I’m still not sure exactly what it is that makes me stop and draw,” he muses. “The city’s changing skyline interests me. I have drawings of the Shard from when it was a stump, just a few storeys high. I like a political event, such as a general election or

demonstration. I drew Trump’s helicopters when he flew over north London during his first term, for instance. The drawings may have a story behind them, but not always.”

Family has also been subjected to his artistic gaze. “I have drawings of my daughters when they were small. I drew a lot when my dad’s health was failing. The sketchbooks reflect my life and what’s going on, and sometimes that means I write in them rather than just draw.”

Whilst James has an office-type studio at home, much of his work is done when he’s out and about. “My creative place to work eventually shrank to a domestic scale: it fits

into my life well in terms of space and time. My studio is on the go because my life is.

Having a space where you can lay out some work and not have to clear it away every time you finish is a luxury made more attainable by working small.” His studio at home is where he stores his 200+ sketchbooks.

“When I was selecting what to include in the book Sketchbook Reveal a year or so ago, I put them in order on a bookcase together for the first time. It was odd to see the last 40 years of my life before me.” They’re now back in boxes.

“I can dip into them as needed but having them easily accessible on the bookcase encouraged a retrospection I can do ▸

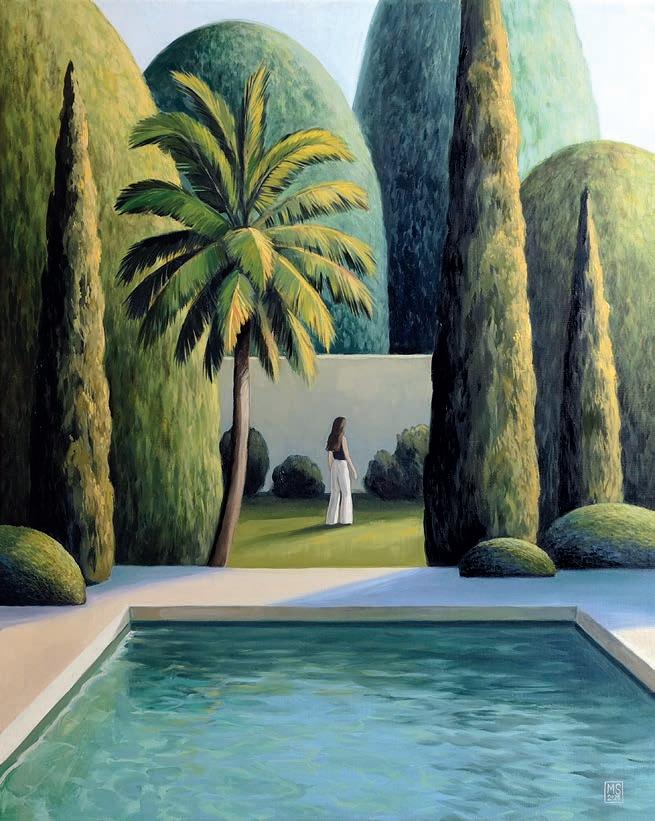

This Polish artist turns natural scenes into serene, geometrical paintings that invite pause and attention, says Ramsha Vistro

If art is a reflection of its maker’s world, then Magdalena Starzyńska’s is one of order, rhythm and silence, balancing structure with softness. Nature is her constant theme, not as a postcard-perfect scene, but as an atmosphere; a place to breathe. Growing up on the edge of a forest in southern Poland gave her this instinct for stillness. She learned early that solitude and nature can spark entire worlds of imagination and today, those lessons are everywhere in her work. Her paintings hold balance without rigidity: strong horizon lines softened by muted greens and browns, figures dwarfed but never lost. After a period of printmaking, she returned to oils, drawn to their ability to hold nuance. She plans each piece carefully, letting compositions ripen before the first brushstroke. The aim is landscapes that are less about depicting reality and more about creating a refuge from its noise. Instagram: @magdalena.starzynska ▸

This artist captures the beauty of life, often hidden in plain sight, whilst he likes to work from feeling, finds Sarah Edghill

Award-winning artist, Richard Claremont, is based in Australia. After graduating from Sydney College of Arts in the late 1980s, he started working as a postman to supplement his income. He set up tiny canvases and a few paints on the handlebars of his motorbike and painted little street scenes as he delivered mail, which led to him finding television fame as the ‘Painting Postie’. He is now one of Australia’s most collectible artists and runs workshops around the world, alongside courses through his online art school, The Skilled Artist. richardclaremont.com

I’m a painter of light and ordinary moments.

I use that description on my website and it came out of years of noticing how beauty often hides in plain sight. I’m interested in the felt experience of a place – the light on a wall, the heat in the air, the smell of wet timber. These things are quiet but powerful. And painting, for me, is a way of holding onto them. Or offering them up again for someone else to feel.

Inspiration tends to arrive disguised as something ordinary.

That might be a chair pushed back from a table, the way sunlight hits a hallway wall, or a glimpse of the ocean through a back window. I’m drawn to quiet, familiar spaces with emotional weight. Domestic interiors, Sydney’s northern beaches, scenes from ▸

In every issue, we ask an artist to tell us about a piece of work that is important to them. This month, we speak to oil artist SUSANNA MACINNES

This is my sitting room, a space where I love to spend winter evenings by the fire, enjoying the warmth alongside my cat and dog. After moving house, I found great pleasure in transforming the stark whitewashed walls into a more intimate and lived-in environment.

One winter evening, after company had left, I noticed the quiet traces of life lingering in the room. The lamp was still on, cushions slouched from recent use and the dog’s basket sat skewed on the rug. Framed photographs and a small model sailboat caught the lamplight, becoming memory points in themselves. I wanted to capture that afterglow of human presence, without depicting any figures.

This piece forms part of my ongoing series called ‘Corners’ – intimate

vignettes shaped by a single light source. For me, interiors function as portraits, with the sitter being the room itself. I am continually drawn to the dialogue between warm artificial light and cooler ambient light, and to the way everyday objects transform into stage props when struck by illumination. This work is emblematic of my practice: a play of complementary colours organised around a single light source that shapes the entire scene.

Objects act as characters in their own right. Floral pillows soften the architectural severity of the fireplace; the dog basket grounds the room and suggests unseen company. pindroppainting.com ▫