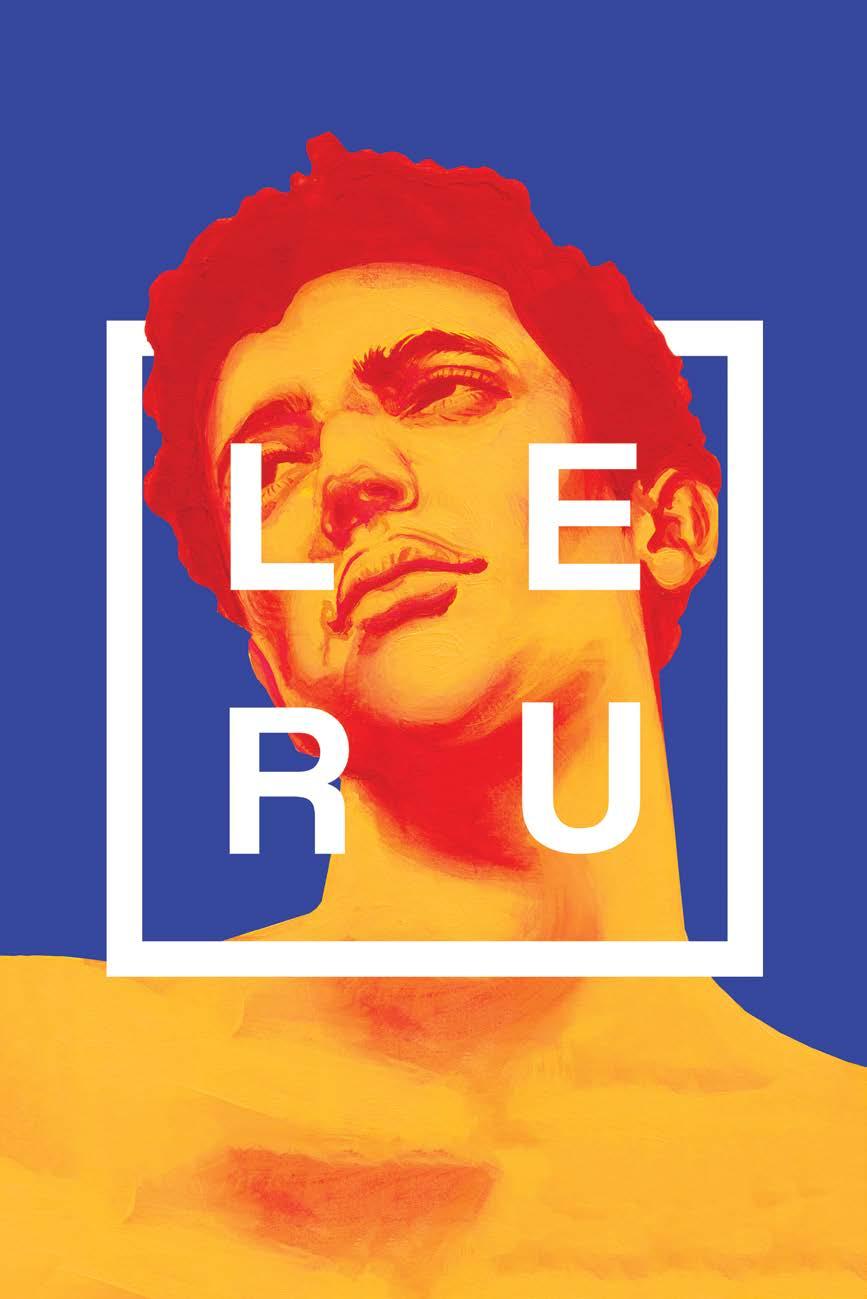

leur - them

I’ve always wished there was a place

Where those like me could be free. Free to express their true authentic selves.

I’ve always wished there was a place

Where those like me could share.

Share pieces of them.

Share pieces of their art.

Their art is an expression of who they are.

Their art embodies their voice.

Their art speaks.

Their art speaks

To those,

At those,

For those;

Those who feel they have no voice.

With this space

We remind them of their voice.

With this space

we allow their voices to be heard.

To be seen.

To be read. To be felt.

With this space

We listen, Together.

Only then

When we take the time to listen, To really listen, Is when we will learn to understand, to respect, to love,

them.

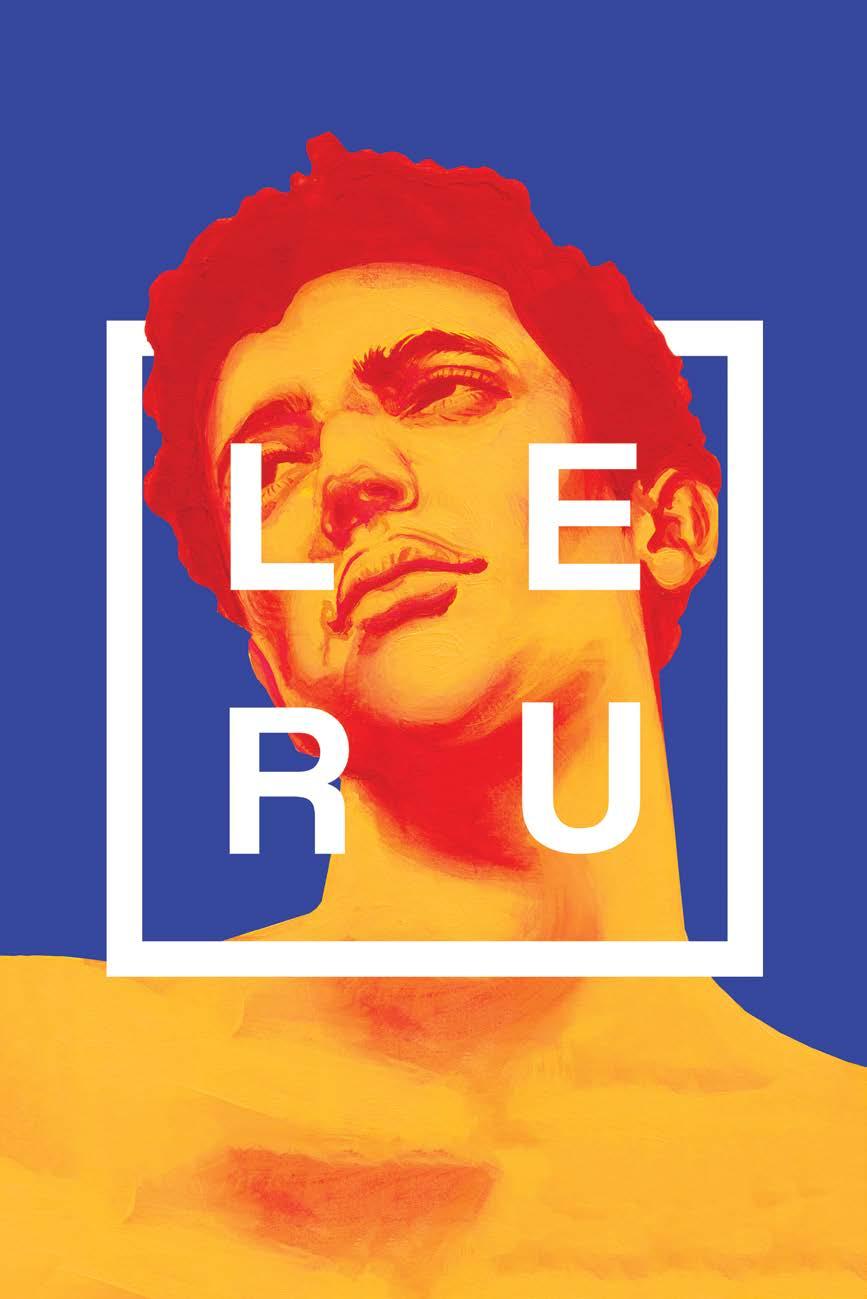

Charles Champagne Founder & Creative Directorcover artist:

Clay Kogut

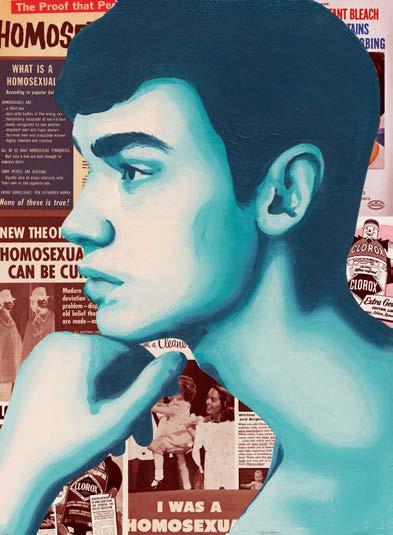

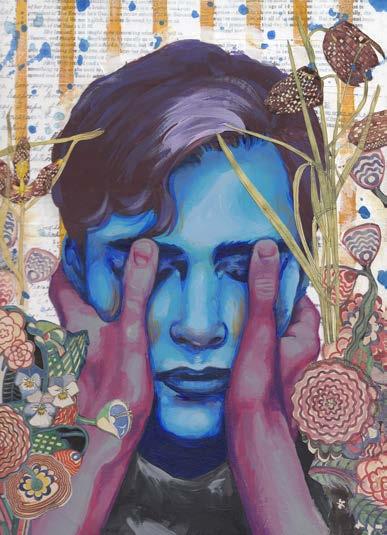

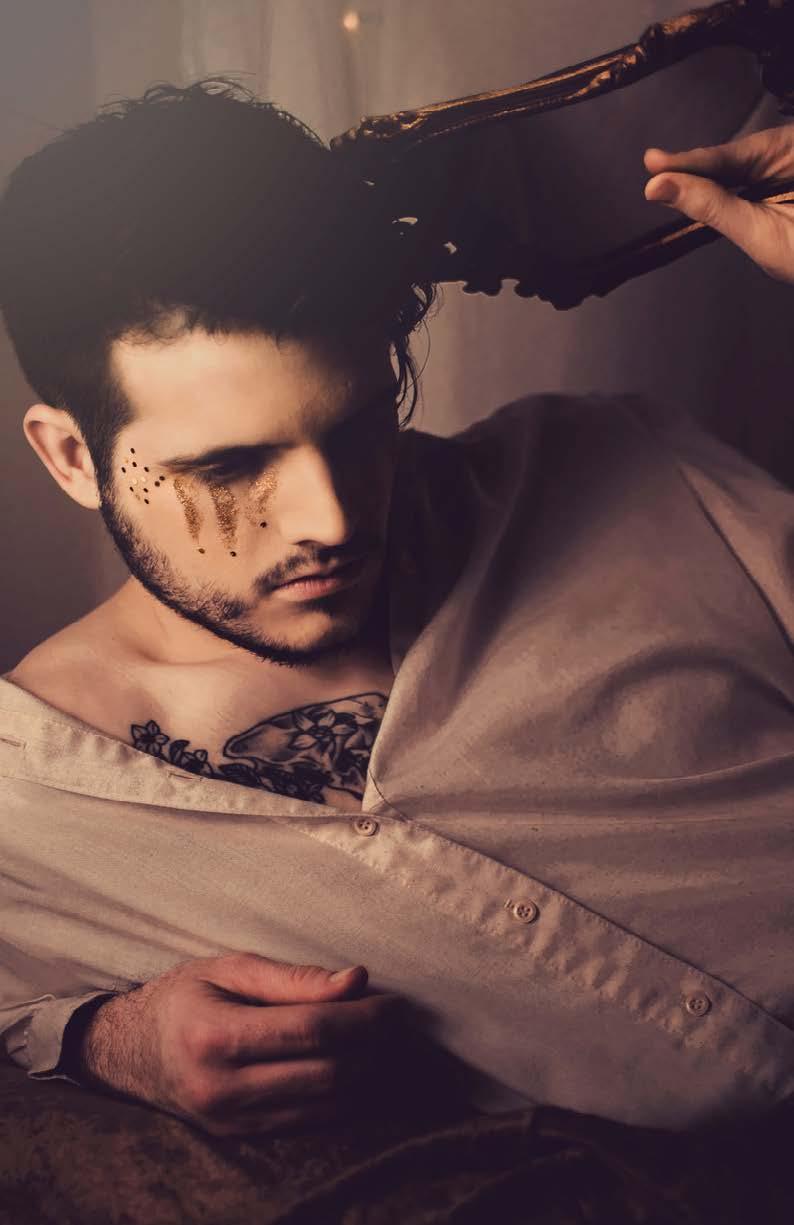

Clay Kogut is an emerging student artist from the University of Texas that specializes in portraiture. Kogut’s artwork seeks to offer an elevated approach to the narrative of life for a queer person living in the United States. He challenges stereotypes through his captivating portraits using mixed media collaging and vibrant color. As an artist his goal is to create a symbiotic relationship between the sitter and the viewer. He explores human facial expressions in order to command attention to the bigger issues queer individuals are managing. Kogut draws upon his personal experiences and seeks to expose the hidden nature of humankind.

Shadows a poem by Walker Dawson

In the shadows they call us

They speak our names in the hour of midnight

Prying our minds and keeping us blind.

Is it fate, you and I meeting in the hour of romance, Or is it a tragedy that in our meeting it’s completely dark?

Surrounded by the echoes of our footsteps we take more, Crawling, walking then running the next block.

You and I we’ve got many to stride together But I wish the shadows would leave us.

I wish we would be what we can be in the light, And let our troubles diminish in the hot night.

Soon they will.

And at the break of dawn like a shadow to the sun Our memories of this time will be that of darkness Killed by the light.

A shadow who can’t fight.

photos of Walker Dawson by Sara Brauda

“As a photographer, I aim to discover stories that don’t fit the typical mold of what love should look like. I use my camera to capture all definitions of love and to spread that to the rest of the world. I love using my camera to connect with others in unique ways; I find their personalities and bring it to the surface.

My good friends Bon and Shelby are the perfect example: Shelby identifies as Pansexual; Bon is Trans, ftm. Their story is just one of many. In an undeniably heteronormative world, we must show that we are here, we are queer, we’ve swallowed our fear and we’re not going anywhere.

I don’t just take pictures—I bear witness to the intimate moments of the lives opening before me. I document that we’re beautiful and we belong here.”

- xoxo Elie

“I Don’t Know” text by Dustin Owen

My relationship with time has always been strained.

We’ve never really seen eye-to-eye. It’s always looking for the next thing, pulling me along. I’m always looking at what was, trying to remember. In my fight to hold onto these moments, they become blurred, stretched between the past and the future. My memories are the casualty of this war – the battle with the beast that’s dragging me to my grave.

There are, however, certain crystalline moments that retain their glitter. They are so important, so perfectly cinematic, that even time itself takes a brief breath.

I remember one such moment. In fact, I don’t know that I could forget it.

It was a Sunday morning. We were passing by the photography studio once dressed as a video store (because those use to exist.) My great-grandmother would always take me there after school for an Icee, which would then be joined by a personal pan cheese pizza from Pizza Hut. Afternoon 90’s Nickelodeon never tasted so good.

On this particular day, there were no Icees or pizzas. It was Sunday, and Sunday was for church. When you grow up in “the south” you are born with a pocketful of what I like to call, “worship options.” I never really cared for any of them. I only ever went because I was told it was the “right thing to do,” and looking back, I did a lot of things because I was told it was the “right thing to do.”

This Sunday service wasn’t special enough to remember; in fact the day as a whole was altogether forgettable… with the exclusion of one short conversation.

It was just the three of us: my cousin, Nanaw (my grandmother), and me. We were in my Nanaw’s beat-up red Camry (the one she would later let me drive haphazardly on the back roads near her house) headed home after the service. My cousin and I were in the back seat singing to the radio, fidgeting in our confining church clothes. Suddenly, my Nanaw turned the music down. She looked into the rearview mirror and locked eyes with me.

“Dustin,” she began, “are you going to like boys or girls when you grow up?”

Without hesitation I shrugged, “I don’t know.”

She just smiled in the mirror, turning the music back up for the two of us to continue singing and squirming.

I must have been like seven or eight years old at the time. The beautiful thing about that age is the honesty. You say exactly how you think or feel without reservation, because there really hasn’t been anything to discourage your truth. It’s an age that precedes monsters like shame and fear. You still have your wings. You can fly above it all. So, what my Nanaw asked me wasn’t something that stood out. Thankfully, time held onto that moment for me. It knew I would need it some day – a day when she wouldn’t be around to tell me what I needed to hear.

I like to believe that she knew I was gay before that day, before asking that question. I like to believe that she had already accepted that part of me before I knew it myself. I believe she was trying to tell me she loved me all the same, no matter who I was. The most mystifying bit was how she showed her love. She didn’t make a big deal about it. She didn’t pry it out of me or preach to me what was “the right thing to do.” She treated me like a human and just asked a question.

She let me decide for myself.

That memory was always with me, at the bottom of a backpack filled with moments I wasn’t ready to look at again. I carried it with me, but I didn’t revisit it until a decade later. I spent those years trying to force myself into a mold made for “other” people, people who weren’t like me. Other children didn’t like magic and building forts in the forest. They didn’t like making wands with tape and hot glue. The only person who understood me was my Nanaw, and when I was 13... she died.

After that day, I was surrounded by the “other” people. I couldn’t see myself in the world anymore. I was the last wizard, and I didn’t think I could make it on my own. I was afraid my magic wouldn’t save me. So, I cast aside all magical things. I traded in my wand for a bible. I suppressed my imagination, and I silenced myself. I wasn’t to think about holding a boys’ hand. “Good boys don’t think these things, Dustin,” I would tell myself. When I thought something “bad,” I would make sure I felt every ounce of shame. I would look at the floor when the pastor said “homosexuals were going to hell.” I would endure the constant name-calling and self-hatred. I would pretend I was one of the “other” people, and I became such a great actor that even when I looked in the mirror that little boy my Nanaw used to smile at was no longer there.

It was a dark time that I am not proud of, but I am happy to say it was a darkness that ended. I eventually found my way back to that cramped Camry, staring into that mirror, into my Nanaw’s eyes. I can see her smile. I can feel her love, and through her eyes I can see the boy I abandoned for what I thought was the “right thing to do.” It is because of that memory that I found my magic again. As a child, magic was spells and wands and potions, and it still is, but now it’s so much more. It’s pizza and Icees and hugs and kisses. It’s wine with friends. It’s bonfires in winter. It’s Early Grey tea and Harry Potter weekends. It’s morning sex and late night gelato. Magic is in those moments where life takes a breath. It’s in the light, and it’s in the dark, and it’s fucking brilliant.

I still don’t know a lot of things, but I know a few things for sure:

1. It does get better.

2. We never have things completely figured out.

3. Hermione Granger is a Queen.

4. No matter who you are, you’re magicool, and don’t you ever fucking forget it.

Glamorous

by Chris Turner NealWhen she was sixteen, my grandmother went to New Orleans on her graduation trip. Sixty years later, she could remember it in detail—the trip’s organizers had arranged for the sleeping cars to be detached from the train and left at the station as a kind of dormitory, the better to contain wide-eyed teenagers from West Texas who were barely too young to have missed World War II and were making their first trip to one of the world’s fabled Gomorrahs. Audubon Zoo had recently planted yellow lilies, carefully bred from plain white lilies that had shown any jaundice, and she still shuddered at the posted hundred-dollar fine for touching them and thus potentially stealing pollen, long after material success and inflation had made her perfectly capable of paying a hundred dollars to touch whatever she pleased. Their last night, the travelers all ate at a fancy restaurant, and before they left, they got back the empty crab shells, washed and painted pearly pink as a souvenir. My grandmother left hers on the train, but kept track of the bigger treasure: the engagement ring from my grandfather, clutched in her fist because she didn’t fully trust it on her finger, a surer ticket away from home than any piece of paper marked New Orleans.

My grandmother was, I now realize, glamorous. As a child, I loved watching her “put herself together”: makeup, hair, the use of an old-fashioned eyelash curler that looked even more dangerous than it was, and hit from a bottle of a boozy-floral perfume. Everyone else in my family could be ready in a few minutes (except a similarly pretty aunt), but Grandmother had to be assembled. Wrapped in bright satiny fabrics, before, during, and after their Designing Women-era heyday, I thought she looked like a million dollars—and so did she.

She was never too prettied up to play with me. We took walks by the lake, where she’d point out the minor natural wonders of West Texas with a perfect red nail. She knew what plants had borne flowers in the spring and what animals you might see (“Watch for snakes!”), and liked to speculate on what life had been like for the Native Americans who had passed through the area, whose arrowheads she still occasionally found but that I, a less cautious searcher, never noticed in the loose thin dirt. The lake has since retreated dramatically, too shallow to maintain its footprint during successive years of ferocious drought, but as it shrank it revealed mammoth bones, which she would excitedly report in her frequent, newsy letters.

Cursed with the mercury-punishing blood pressure that runs in our family, she had a bad stroke in her sixties; afterwards, I was the one who was first able to coax her into eating half a banana. Soon after, she gave away all the high heels she’d always loved, resigning herself to less precarious flats and wedges. She saved one pair, tan and black and very pretty, that sat in the center of the back wall of her closet as long as she lived, demure and monumental.

My grandmother was the last person I came out to, not because I was afraid of her reaction, but because she mattered most. My father had come to all my theatre productions in high school, and my mother had made clear that she thought the idea of having a gay son would be fun, primarily because she assumed I would encounter a lot of heartbreak because of it and need her. (She was half right.) I wrote my grandmother a letter—yes, because it was distant and safe, but also because we’d always written letters to each other, even into the era of grandparents on Facebook—we both enjoyed pretty stationery. Her reply was loving and matter-of-fact, and meant the world to me. She would later meet my partner; when I left him in the last year of her life, she was glad I’d escaped the family curse of marrying addicts, even if that had more to do with the timing of Obergefell than any self-preservation instinct.

I am comforted when I remind myself of her. I cook her recipes and repeat her phrases; like her, I take too many close-up, almost pornographic pictures of blossoms. I rest my hand on a table the same way she did, and choose bright colors she would have liked. My lips purse in dismay like hers, and I have the same quick, sharp tongue we both often regretted. She had been born to be poor, to dry out too fast and live in a gas-station town, one of those Christ-how-do-people-live-here wide spots in the road named after a railroad executive. Her path of least resistance was a dry, cracked sidewalk, leading nowhere in particular, and she stepped off it. Because it was 1947, part of that escape was marrying my grandfather; despite it being 1947, she worked. Her extra income wasn’t, probably, very much compared to that my grandfather’s successful contracting business brought in, but it let her surround herself with pretty things, add another layer of safety between herself and the nagging, grinding poverty that dogged her mother all her life, and give big, splashy Chrishtmases. One of the last things my gift-loving grandmother ever gave me was another chance, like the one she’d made for herself: when I rolled back into New Orleans to start over (again), it was in the wide-bodied, smooth-riding Buick I’d inherited from her.

The last time I held my grandmother’s hand, she still wore rings on it: not the emeralds, those had been sent from the nursing home for safety, but some cheap, shiny ones from the mall that my aunt had bought her so she didn’t have to be plain in her last months. Her nails were still red.

Chris Turner-Neal is a writer and editor originally from Texas currently living in New Orleans. Highlights of his career have included writing an etiquette guide for misanthropes and replacing Bob Saget as the writer for a holiday article in Philadelphia style magazine. He is the Arts and Entertainment Editor of Country Roads Magazine in Baton Rouge.

We’re Still Here Photo Series by Ren Adkins

“We’re Still Here” began in Los Angeles as a response to the 2016 Presidential election. During that time, I and a lot of my peers were feeling shocked, powerless, and disenfranchised. In reaction, I created this photo series, in which I set out to give members of the LGBTQIA+ community, women, and people of color a platform to tell their stories and share their experiences and opinions on current events. Over time, the series has expanded to include one on one discussions of individual struggles as they relate to the current political climate of our country, covering a broad range of topics from gender and sexuality to healthcare.

Ren Adkins is a photographer based in New Orleans, where she lives with her fiancé and two grumpy cats. With a BFA and MFA in photography, Ren focuses on combining fine art photography and commercial work. She is a visual crusader, media literacy advocate, and fiction junkie who loves the art of storytelling in all its forms and hates talking about herself in the third person.

Xavier

Los Angeles, 2017

“I was born and raised in LA, and my family, they were all born and raised here, inner city. But even still, they’re extremely unaccepting. I’ve never been “out and proud.” I’ve just kind of lived. I’ve just always [perceived myself as] male.

The first memories I have are asking [my family], Can you pray about *anything*?’ ‘Cause we used to do prayers, every night before bed, and they’re like ‘Yeah, you can pray for anything!’ I was like, great, okay, yes. ‘Dear God, remember to help my penis grow so I can pee behind the bushes like all my friends.’

And then my Dad was like, ‘Woah you can’t pray for that. That’s not gonna happen.’ And I was like, no, you just said *anything*. You can’t take that back! And I’m like 3 years old, you know what I mean?”

Gracie Los Angeles, 2016

“I’ve never really been a person who’s into politics, and this election has made me want to become more aware... Everyone has different views, and I’ve learned to respect that. I came into a situation where this guy that I was [close to], on the day of the election, he was like, ‘Go Trump!’ And I was like ‘[makes gasping noise] Please tell me you’re just joking!’ and he was like ‘No, I’m actually serious.’

Afterwards, I had to really do some questioning, just thinking like, okay, because he votes for Trump does that mean that he’s a bad person? Does it mean that he’s a racist, that he’s not supportive of the LGBT? There are so many reasons that people are with Hillary, just like there are so many different reasons why they’re with Trump, and I’ve really gotten to an open place. I can’t expect for people to be so open about me and accepting of the way I live my life, so how can I be that judgmental about someone else and their different viewpoints? I’ve learned that it’s really okay to agree to disagree... It doesn’t mean that you have to change your opinion, but it does help you in the long run to open yourself up to the other party’s perspective. I feel like it makes you a little bit more educated and well rounded.”

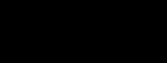

Cameron New Orleans, 2018

Cameron New Orleans, 2018

“I guess art, for me, has always been a way of dealing with [depression], whether the art is directly speaking to that or not. I think the process is always a mindful one. That helps me deal with intrusive thoughts or anxiety in a way that is helpful in a world where you need that sort of escapism because the 24 hour news cycle is so overwhelming… I think any experience like that is so inward that it becomes outward because it always comes from a place of compassion for yourself and others. I always think about how the root of the word “compassion” means “suffering with.” I think practices like that should be so much of a bigger part of everyone’s day because you go back to politics, and you think about all these policies that are being put into place that are just so far removed from a place of compassion, and it’s so hard to teach empathy to people… It’s like, how can you be rolling back all these programs that are meant to help people move forward? Even as recently as seeing things about food stamps and other aid for povertystricken people, making it more difficult for them. It’s like, what’s so wrong with wanting these people to be able to live that American dream? What’s so wrong with wanting these people to be able to move forward?”

Boyfriend

New Orleans, 2018

“I worry lately that modern activism is too fueled by the idea that your morality is somehow enhanced by policing someone else’s, particularly via social media. But if there is to be a revolution, there has to be more at stake than an individual’s morality, we have to critique systems not just hunt bad guys. It’s like we’re trying to master the game of wack-a-mole instead of take a screwdriver to the entire machine.”

Casper Los Angeles, 2017

“I’ve opted out of [testosterone] for now because I want to sing, and I’m afraid of what that’s going to do to my voice... I can’t handle puberty right now. But the one thing that I think is, at least, a positive about me not being able to have the body [that I would like to present myself as], is that it makes me really have to disconnect from my body-- and I’m not saying that in a bad or negative way. Because if not, looking at my body every day is gonna break me down. I’m gonna be upset, I’m gonna be like, oh my god, I have these breasts, and my hips and my thighs. I’m gonna just constantly be a negative feedback loop to myself. So it’s like having to disassociate from that, in a lot of ways, has been very beneficial for me personally. Obviously if your dysphoria is so bad that you need to get on [hormones] do it as quickly as possible. People need to do whatever is gonna make them happy, what is gonna make them feel the most authentic and comfortable in their skin. But at the same time, the ‘luxury,’ if you could call it that, I have is that I really am acutely aware that bodies are just vessels that we use as performance pieces. It’s just an art piece. That’s it. It really means nothing more than that. Whatever I am has nothing to do with my body. It’s in my brain, it’s in my heart.”

Allie Drew Caesar

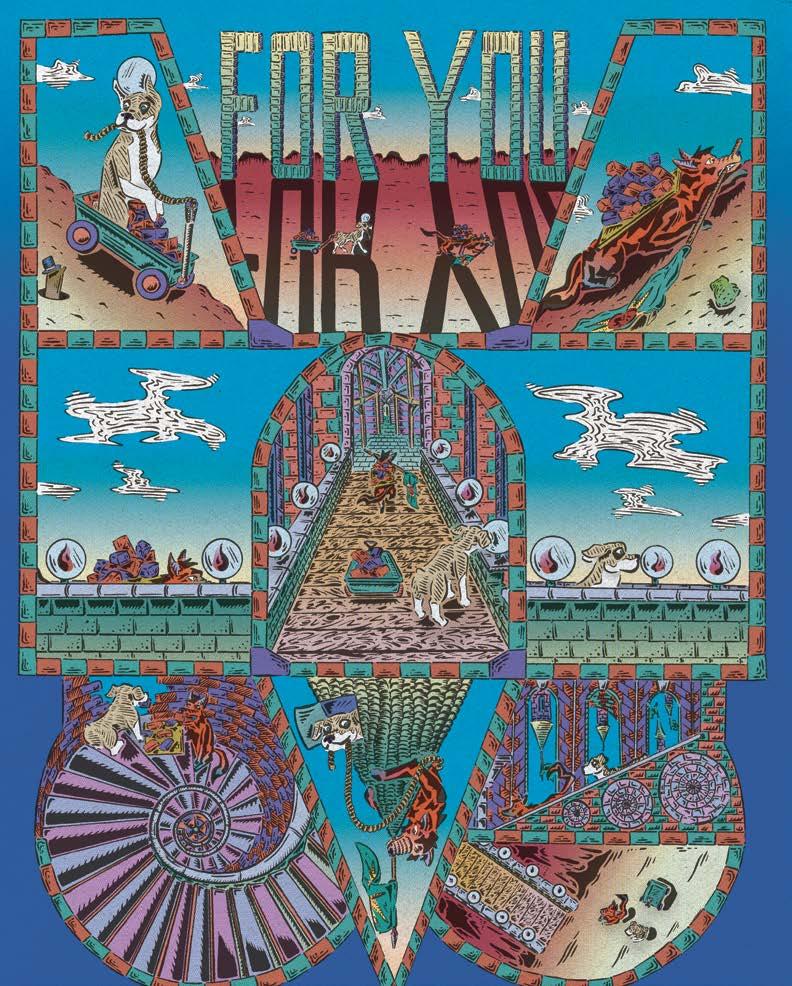

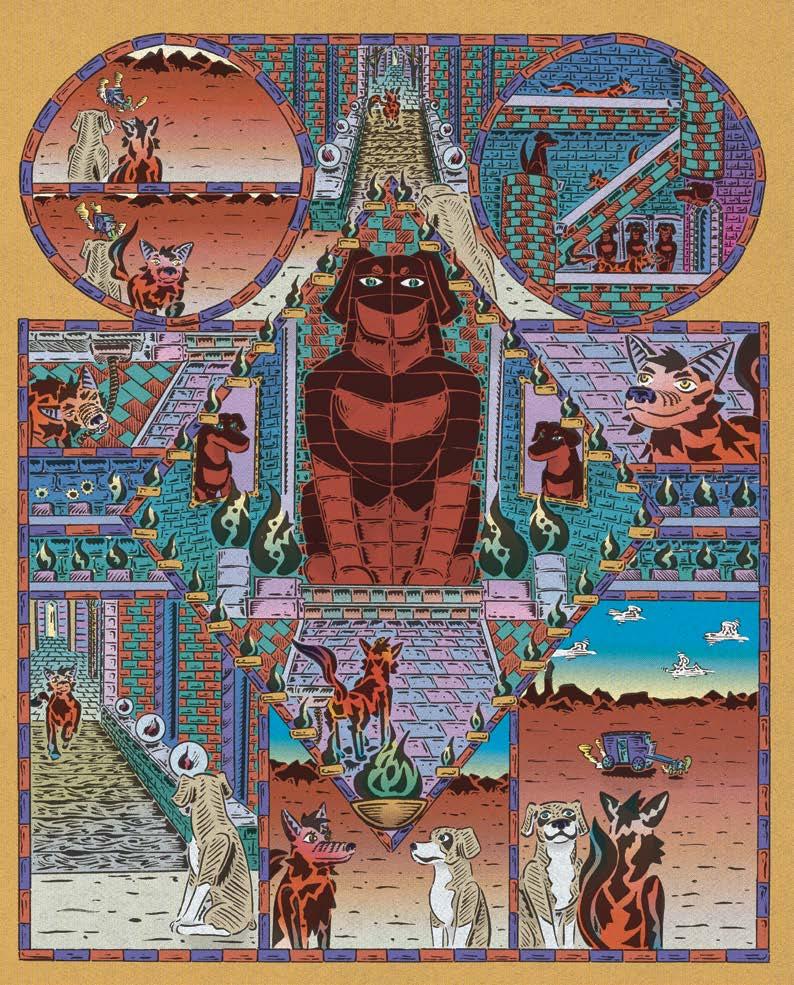

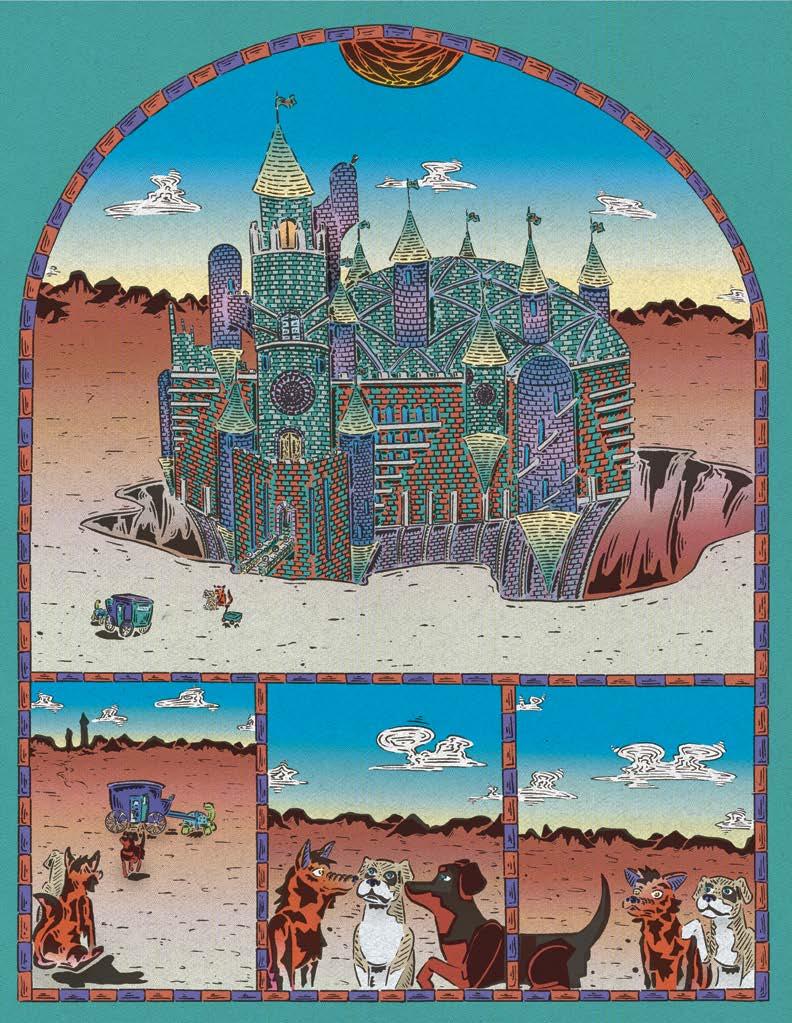

For You is from an ongoing collection of comics about wolves and dogs being as human as we sometimes are like animals. These comics deal with a wide range of topics such as war, identity, capitalism, and with For You specifically obsession and abuses relationships and friendships. All comics in the wolf and dog collection are internal wordless aside from they’re titles, this was done to provide a story to the largest possible audience with the hopes that each story would present ideas and questions to both the most earnest and curious young mind as well to us older folk who are still sorting out those genuine observations now buried in so much life. For You is dedicated to the deserving if you build castles make them together and only for each other.

Allie Drew Caesar, sometimes called Allie, sometimes Alan, on occasion Drew. They are non-binary cartoonist born and raised in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma by a single mother who works in state government. As far as fully government funded projects go Allie Drew is somewhere in the middle of the boondoggle scale. They currently reside in Chicago and spend most of their time drawing cartoon animals performing political satire with cartoon folks under the label Downfall Arts. Their work includes such comics as Rena Rouge, Destroit All Monsters, The Bar Dat, and many others. They design clothing in their spare time, mostly leather, with a lot of metal. Examples of both their comics and clothing design work can be found at their website www. downfallarts.net

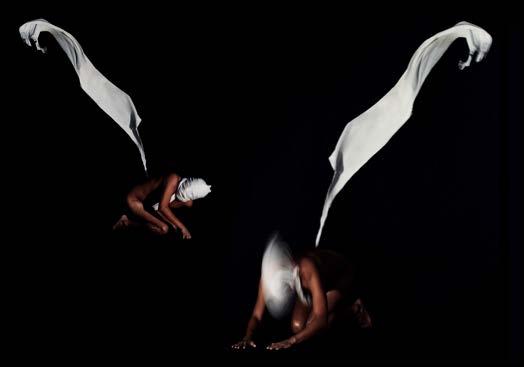

Roberto Navarette Visual Artist

My research offers a bridge into the physical, emotional, and spiritual scaring caused by global intolerance towards the LGBTQI community and various marginalized individuals. This body of work is a collection of history and experiences resurfaced then physically transformed through knots with a specific set of materials and intention. My objective is to deconstruct each individual knotted cord that makes up the fabric of my identity then reconstruct it as a space that offers a visceral experience for the audience that aesthetically explores the body’s transition as it heals. The residue of the final pieces takes place within that reflective, transitional process at the intersection of the space and temporality that I occupy as a Queer, Latinx Artist of color.

Roberto Rafael Navarrete, born in Queens, New York, was raised in Atlanta, Georgia. Navarrete and his four siblings are first generation Peruvian Americans. He graduated from Georgia State University in 2011 where he received his Bachelors in Fine Arts with a focus in Drawing, Painting, and Printmaking. His work has been included in several exhibitions. In 2015, Navarrete received The Graduate Teaching Assistantship at Florida Atlantic University and was awarded The Provost Fellowship 2015/2016, The Rothenberger Scholarship in 2016 and The Friedland Research Grant in 2017. Navarrete currently lives in South Florida and is a Masters in Fine Arts candidate (2018) at Florida Atlantic University with a focus in Painting, Photography and Mixed Media Installations.

Welcome to Volume 04

Another PRIDE month has arrived and LEUR Magazine is still here and still queer AF. Our platform continues to grow and evolve as we remain dedicated to providing platforms for Southern queer artists to share in their art-making through creative community collaborations.

Since opening the submission gates for issue 04, we have received various themes of artwork from LGBTQIA+ artists all over the country. Some of the themes you will see in issue 04 cover self-expression and identity, queer emotions on our current political climate, Southern grandmothers and their life-long impressions on their gay grandsons, humanistic behaviors such as abusive relationships, as well as photography capturing the love between two souls amplifying queer love.

Leur in French means “their” and “them”. Possessive pronouns that are inclusive, collective; representative of a group like our LGBTQIA+ community. LEUR tries to focus on representing the diversity within our niche of Southern queer artists and the diversity of aesthetics they bring to the table. Our platform is contributor-based which means our issues are curated around the entries and submissions we receive through our inbox. This allows us to better represent current up and coming artists all around the queer South.

This PRIDE season we are asking our community to help us grow our audience and reach out to more Southern queer artists. We are more than a print magazine. We are a Southern queer collective, a family. A family that works hard to offer more opportunities to queer artists here in the South through local events, printed publications, interactive campaigns, and collaborations. We want to show the world that the queer community here in the South, primarily in Louisiana, is here and will always be here. Like a proper family we want to mentor Southern queer artists and teach them how to better represent themselves not only as queer people, but as artists.

I hope you enjoy issue 04 and I hope you see the potential of this ever-evolving platform. Remember, we do not succeed alone, we only succeed together as a community and as a family.

Love, Charlie