their lives, their voices, their stories

Curator Charles Champagne

Director Devin Rogers Videographer Ashley Ann Estave

Lauren Duhon

Claire Comeaux Walker Dawson

& Katie Brauda

Thaxton Ryan Rogers Baylea Jones

Mathis Kane

Curator Charles Champagne

Director Devin Rogers Videographer Ashley Ann Estave

Lauren Duhon

Claire Comeaux Walker Dawson

& Katie Brauda

Thaxton Ryan Rogers Baylea Jones

Mathis Kane

Estelle

Estelle

Founder + Creative

Account

Contributing Editor

Contributing Artists

Sara

Ryan

James

Elliot

& Jake

Brooks

Dark Roux

Photogrpahy

Collin Richie

Photography

02

Curator’s Note :

I’ve always wished there was a place where those like me could be free. Free to express their true authentic selves.

I’ve always wished there was a place where those like me could share. Share pieces of them. Share pieces of their art.

Their art is an expression of who they are. Their art embodies their voice. Their art speaks.

Their art speaks to those, at those, for those; Those who feel they have no voice.

With this space we remind them of their voice. With this space we allow their voices to be heard, seen, read, felt.

With this space we listen, together.

Only then when we take the time to listen, to really listen, is when we will learn, we will grow, we will love,

them.

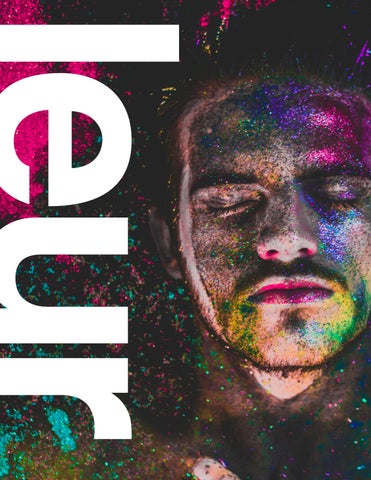

In this issue, sisters Katie and Sara Brauda take best friend Walker Dawson on a trip down the rabbit hole. From concept to final composition, their main goal was to accomplish a sense of true authenticity in self-expression. As Sara states, “His character was spilling from the seams with beauty and color to offer the world around him a lovely thing.” Something we as a brand try to always follow through on when selecting submissions for our curated issues is art that thrives on capturing the true spirit of the subject.

Covington-based photography company, Dark Roux Photography captures beautiful imagery of local and nationwide same-sex couples that celebrate their commitment to a lifetime together. Their styles are all-together warm, vibrant, emotional and simply breathtaking.

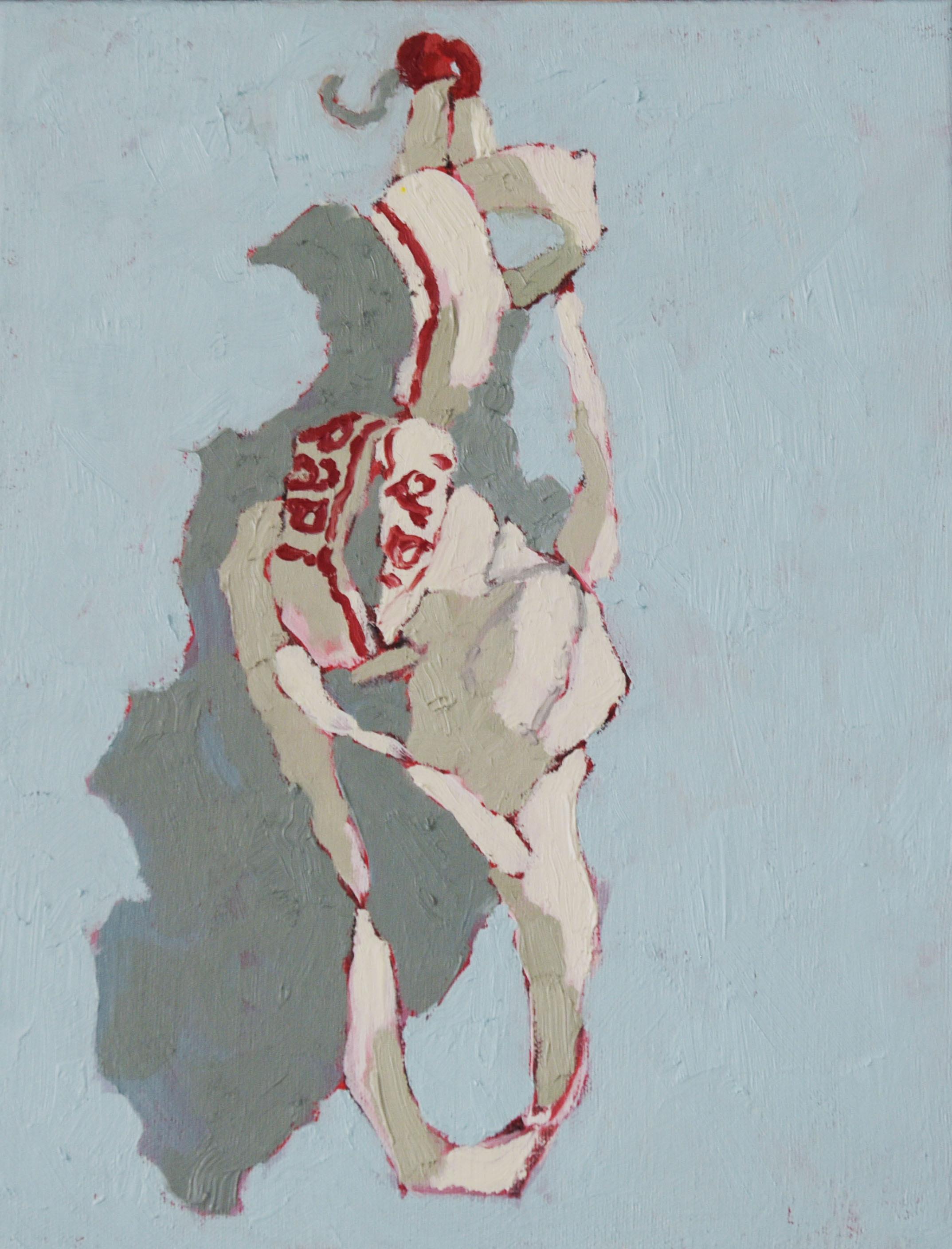

James Mathis Kane is a Baton Rouge artist whose abstract paintings explore the different facets of his personality. As well as celebrating the present identity that he holds dear and the future that awaits his greatness. In this issue’s Q+A segment, we talk to James about his most recent series of paintings and how they continue to allow him to indulge in his own self-expression.

You will also find a written memoir by Ryan Thaxton that encompasses the feelings one may go through from losing their family home during Louisiana’s most recent series of floodings. Especially when your home holds all of your darkest secrets. New Orleans-based copywriter Ryan Rogers takes us to another galaxy where there is a planet inhabited by all the men who have never had sex with you. Through this campy, yet truly endearing narrative, you learn that no matter how extensive your search for love, or even a hookup may be, you should never forget how perfect you already are.

The final segments of poetry will show you how growing up queer in the South affects your own personal views and acceptance of your own self. Claire Comeaux talks about how owning up to who you are takes time. Even if it’s as simple as etching down your name, better yet. your sins. Baylea Jones allows us to feel what it’s like being “butch” in a close-minded small town and what it’s like when you’re finally in a place that accepts and understand you.

Overall, we have a great issue for you to enjoy and we thank everyone who has continued to show this publication support and merit.

Welcome to Issue 02.

Charles Champagne Founder + Creative Curator

Wonderland

“

The inspiration for the shoot was brought about by the desire to reflect the bizarre, mystic, and colorful soul of the subject. When thinking of ideas to develop into reality, I wanted something that screamed uniqueness. Most the magical elements would come during editing, when I was in my zone, candles lit and music surrounding me. I chose a psychedelic color palette to offer a very Alice in Wonderland feel. Sort of like he was lost in a Wonderland of his own radiant spirit. His character was spilling from the seams with beauty and color to offer the world around him a lovely thing that he wore like a badge, something that he couldn’t hide. ” - Sara Brauda

photography : Sara Brauda + model : Walker Dawson

photography : Sara Brauda + model : Walker Dawson

Dark Roux Photography

New Orleans wedding photographers

portrait photographers providing personalized client experiences and first class service with documentary style wedding photography. Servicing New Orleans, South Louisiana,

beyond.

good things

and

and

“Our couples are passionate about one another, enthusiastic for the

in life, excited about having their photograph taken, and want to make this world a better place.” - www.darkroux.com

Andrea + Jessica

Brent

Herb

+

Cristina + Kayla

Sherri + Stasha

Wedding photography by Collin Richie

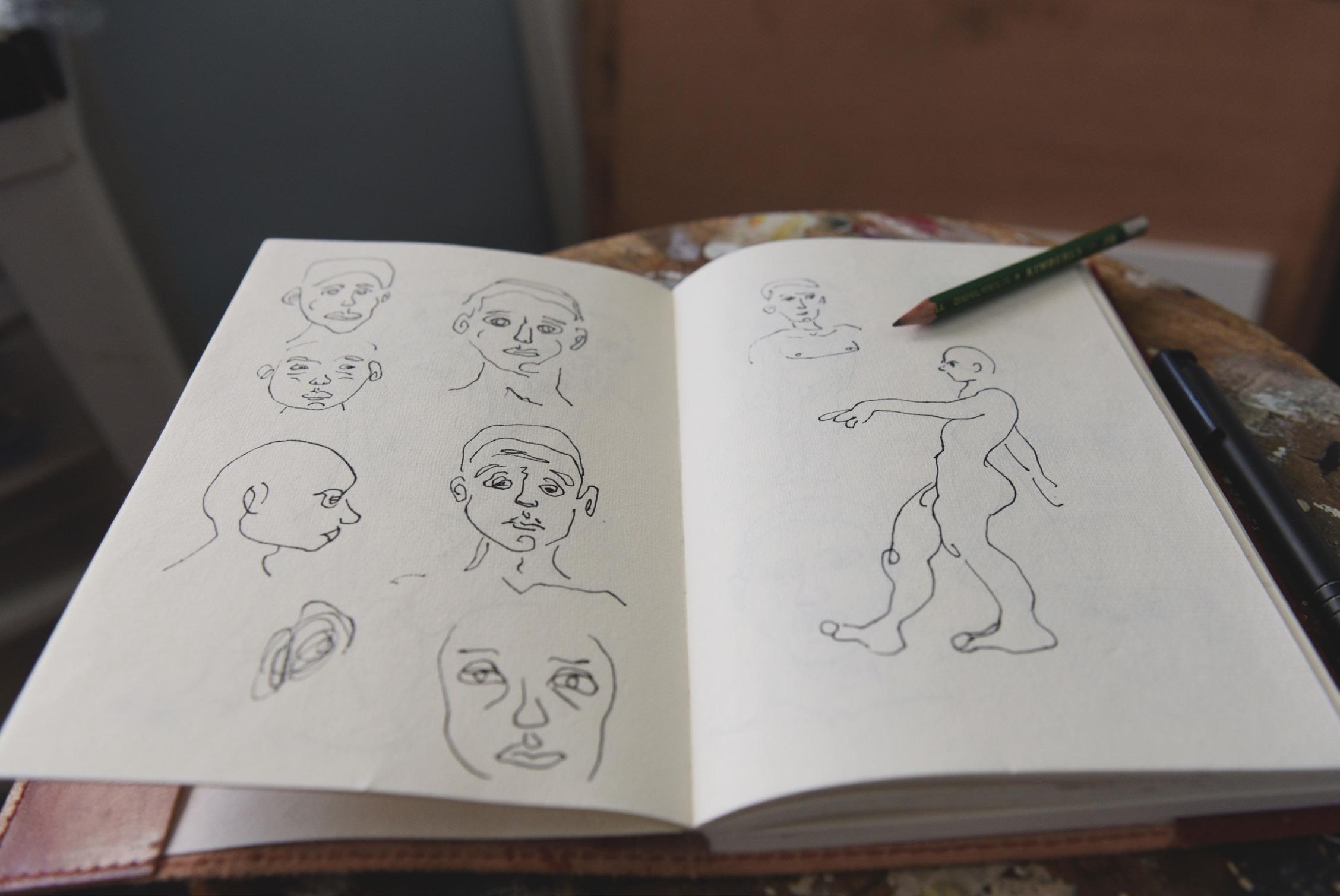

James Mathis Kane

Interview w/ James Kane + photos by Charles Champagne

Artist Statement : It’s hard to say I’m not seeking validation. I think to some extent, all artists are. For me, being an artist has been part of my identity for almost as long as I’ve been conscious. It predates even my sexual identity. Which didn’t come as naturally, or at as low a cost. Now these two things are really the anchors of who I am. It just makes sense that they came together this way. My identity as an artist, something I’ve always known about myself, being reconciled with my sexuality, something I had to learn and am still learning, is the inevitable result of me finding out who I am and what I can do. My work now is not just an investigation of these different facets of my personality, but a celebration of my identity in the context of its heritage, and more importantly I think, its future.

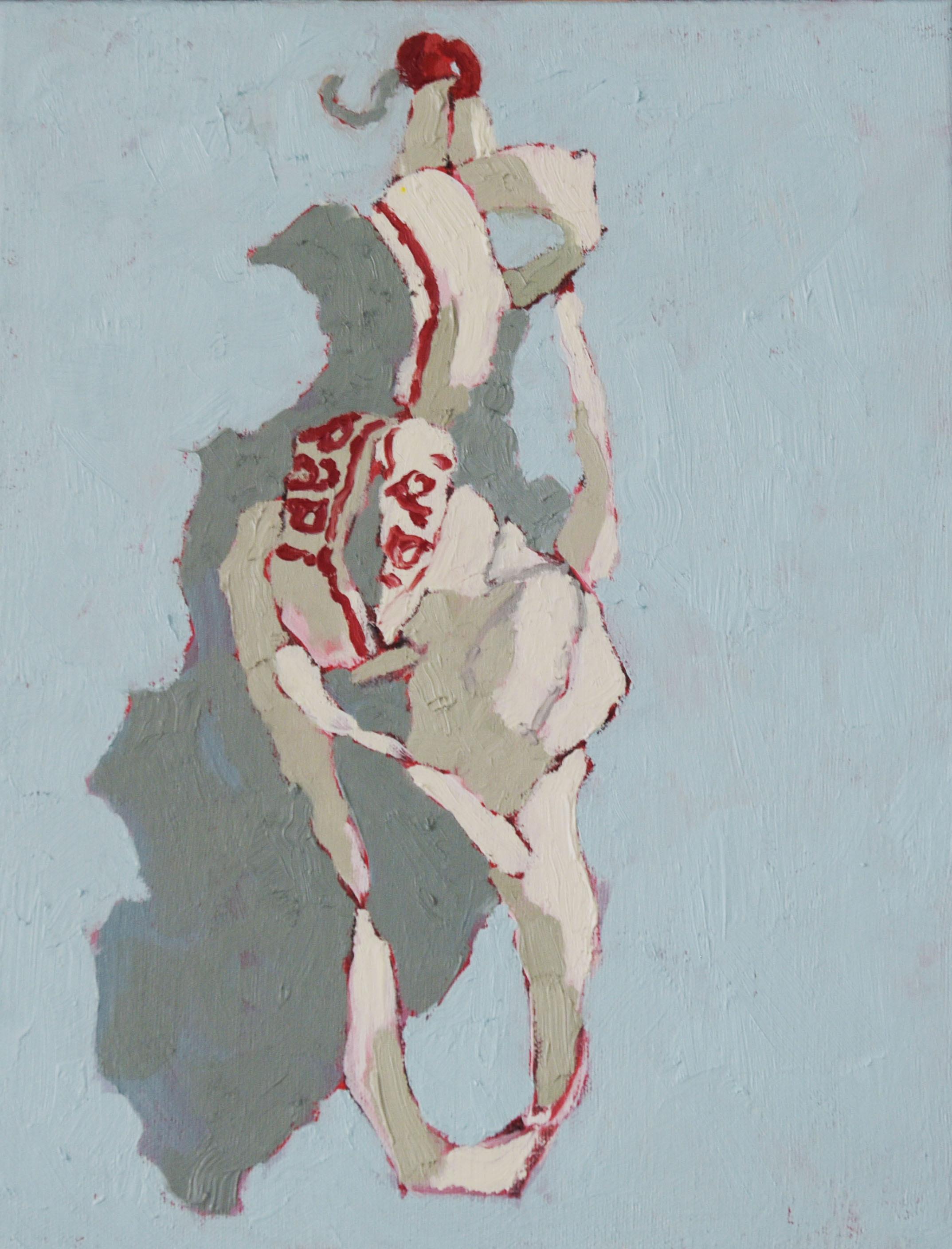

< Candy Gandy Oil on canvas 14 x 11 Know What You Want Acrylic on paper 18 x 22

How do you define yourself as an artist?

“I’m gay, I’m a painter. I don’t particularly like being any one particular thing. I even hesitate to call myself simply “a painter” because I still have all these ambitions for three-dimensional projects and performance pieces.”

How long has your relationship been with painting?

“I’ve been sketching/painting in some form for practically my entire life. Drawing really was my first love, I always felt sort of a natural affinity for it, and painting was the logical next step. It didn’t come as easily, but I was able to learn a lot about color/ texture/line, and I’m still putting the pieces together. It’s a constant progression.“

Your Hands Are Mine Mixed media on paper 20 x 24

What is it about this medium that speaks to you and your self-expression?

“There’s something very sensuous about paint. I love the lushness you can produce with it. I think that contributes to the content of my work as much as the fact that I make it. It invests a different sense of intimacy than if my work were all sculpture or photography. And painting really helps to inform my endeavors in other media.”

“If my experience with art reflects that of the LGBT+ community at all, I don’t think it’s melodramatic to say that creativity and having an outlet for that type of expression can save your life. Art has been a safe space for me during some of the most difficult times in my life, and now I’m finally able to approach my work with unhindered honesty and joy. My work today isn’t just self-expression, it’s celebration.”

In your own words, how important is art for selfexpression, especially to those who identify on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum?

See All The Ways I Can Move

Mixed media on canvas 16 x 20

What is the overall theme/subject matter/muse/etc of your current series of paintings?

“Typically my work does focus on homoeroticism. I’m interested in somewhat distorting male figures and placing them in cropped compositions in an attempt to abstract the activity within the painting. At the same time, I want the work to be an honest expression of gay male sexuality. It sometimes feels like a fine line between being a cliché and being unapologetic about my work.

More recently, I’ve started work on a series of still lives meant to examine different “types” within the gay community. The jockstrap paintings are the first in this “Archetype” series.”

What is it that you wish to accomplish with the series?

“The idea behind the “Archetype” series is to show how different types of men are idolized or ignored within our community. I also like the idea of investing objects with sexuality and erotic purpose. The concept is still in development, but I think with some refinement, I’ll have some good work on my hands.”

Where do you find your inspiration for the paintings?

“I use a lot of found photography that inspires compositions. I’ll often alter aspects of the setting or add in multiple figures according to what I’m trying to accomplish with each piece. Some of my work is just an expression of pure fantasy, something every young man growing up afraid of owning his identity is familiar with. Other paintings draw from memory, if not specific instances, then from the feeling I associate with a particular time or place.”

Archetype i.ii Oil on canvas 14 x 11 Archetype i.i Oil on canvas 14 x 11

Archetype i.iii Oil on canvas 14 x 11

How do you respond to those who may find your work uncomfortable, innapropriate or vulgar?

“I think that context is everything. Plenty of people would call my work inappropriate or vulgar, and in some settings I’d have to agree with them. My work isn’t for everyone. There’s always going to be someone cringing, and I’m not going to apologize for that. I’m not going to adjust what I do to make anyone comfortable. I’m tired of being made to feel like I’m in the wrong place, because of what I make, how I live or who I love. If you’re cringing or offended by my work, maybe you’re in the wrong place. Like I said, my work isn’t for everyone, but it’s for anyone who can look at it for what it is and take something positive away from it; no matter their gender, sexuality or artistic preference.”

Virgin

Spring

/ oil on canvas / 14 x 11

Jack/Jill

/ oil on canvas / 14 x 11

Pound Of Flesh Mixes media on canvas

A Dance We Know The Moves Mixes media on canvas

Pound Of Flesh Mixes media on canvas

A Dance We Know The Moves Mixes media on canvas

Hush Now My Back Wings

Mixes

media on canvas

Instagram @jameskaneart

When Bathrooms Flood

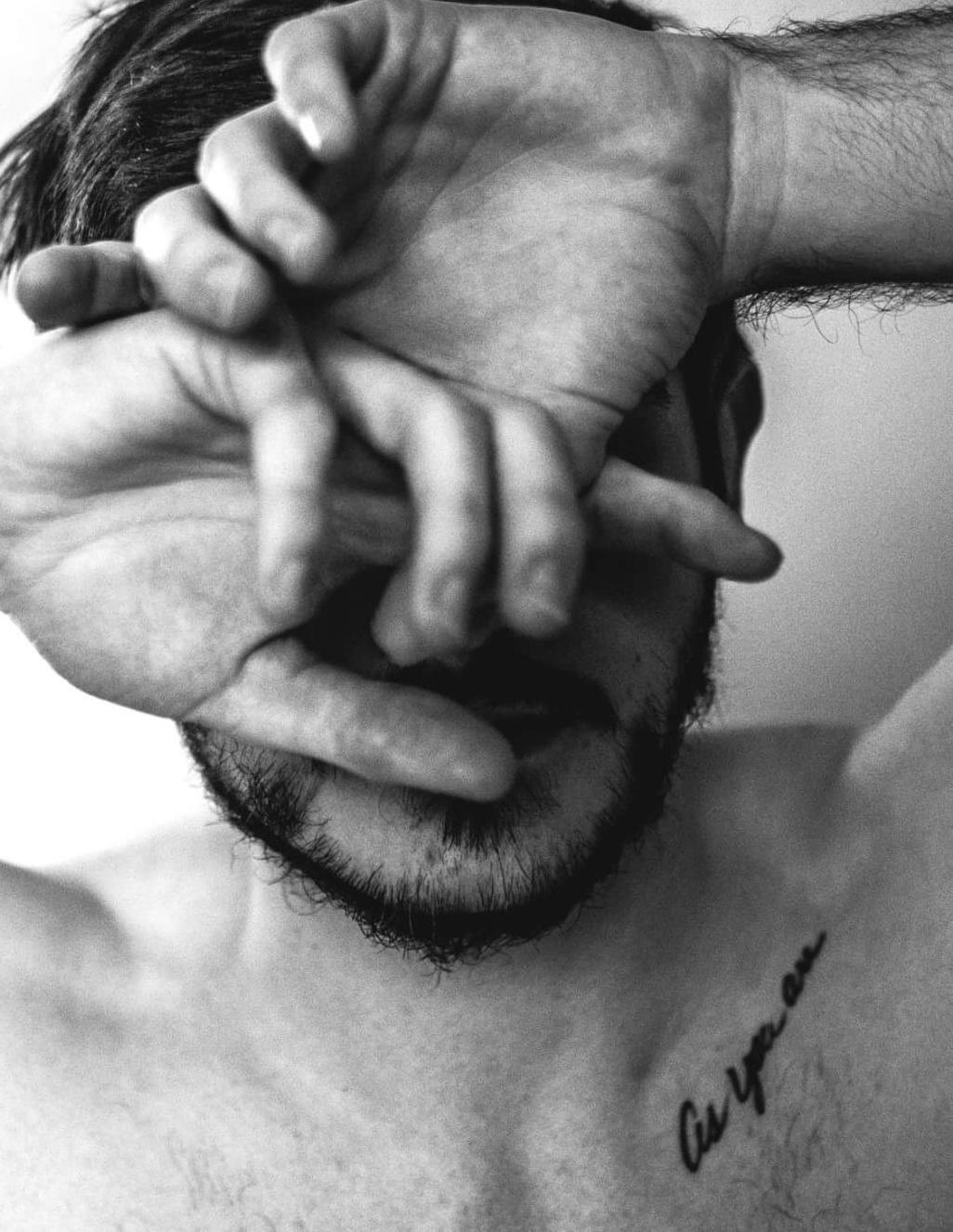

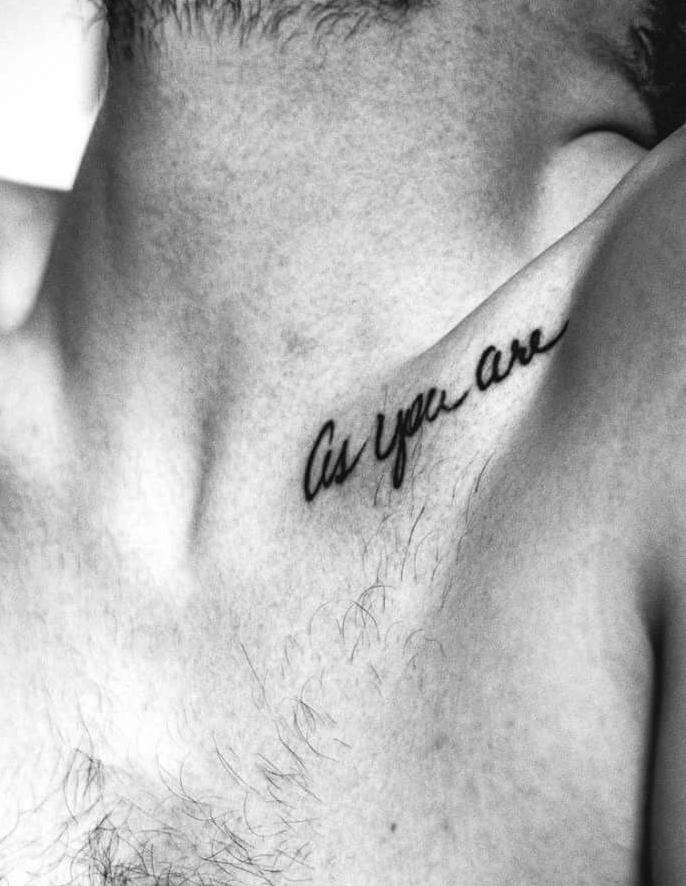

A personal memoir by Ryan Thaxton Photos by Charles Champagne

I.

The house I grew up in was nothing special. Old enough for the back end to have sunken a few inches into the ground, but not enough to be charming. A brazen crepe myrtle by the driveway balanced out the chipping, dirt-white paint on the front porch to make it overall average in appearance.

After saying my bedtime prayer I’d lie awake in a panicked sweat before running across the hall to my parents’ room. The concept of heaven was fresh in my mind and once I failed to wrap my head around eternity the whole idea of an afterlife filled with strawberries, never-ending laughter, and giant houses they tell little kids about in Sunday school had me convinced I never wanted to die. My mom would win me over by threatening the alternative.

In third grade I picked up all of my stuffed animals and moved to the guest bedroom on the opposite side of our house. My new sanctuary and the hub of my familial espionage, I would sit in the adjoined bathroom and auscultate whispered conversations from all corners of the house. I became all knowing, privy to my parents’ speculations on my (gay) sexual prowess and debates of their own infidelities.

When Bathrooms Flood

Written by : Ryan Thaxton

And I had my own secrets. No matter how old I was there was always something to hide in my room: conversations with unidentified boys, diaries that would have alarmed any cognizant parent, and later stashes of illicit drugs. Each their own form of escape. As I grew up, the room grew with me, complicit in as my closest ally in rebellions.

II.

Wednesday, March 9th, 2016. The air was cool but I could already feel the stickiness that accompanied summer. At 9:34 p.m. my mom texted me:

The intrusion would proceed for several days and stand at two feet, seeping into the walls, distorting wooden floorboards, marring the furniture, ultimately ruining everything it touched. It was a small flood in north Louisiana, foreshadowing one much more severe to come farther south a few months later. Barely anyone in my college town had even heard about it.

Walking home to my dorm that night I felt a glimpse of homelessness. The decrepit street lamps set the mood like an old jazz video. Spotlight after spotlight of harsh, yellowed buzzing exposed tears I couldn’t explain.

“ We’re going to flood. ”

III.

It was Saturday when the water subsided. I went to the local gay nightclub with my friends, per routine. It was objectively the cleanest bar a nineteen year old in Baton Rouge could get into, which isn’t saying much. Fog and neon welcomed queer youth looking for a place to relax in their new town famed for football, beer, and everything masculine.

I joked with my friends that I was a flood victim, now homeless in a humorous, cynical way. I brought it up incessantly and surprised myself each time. My new status was the ploy of the night for free drinks.

My mom had asked me to come home that weekend, but I claimed the flooded house was too traumatic to witness. There was nothing I could do anyways; I would be stuck around people I wasn’t close with, sleeping at another house that didn’t feel like mine—not that the mildew-stinking house ever did either.

IV.

The summer after sixth grade I went (was forced) to church camp. Every evening of that long week we gathered in a chapel to sing along to some obscure Christian alternative rock band—one that sounds just like every other Christian alternative rock band berating you from the radio of your mom’s Chevy suburban on a Sunday morning. I hated it.

I was a fake masquerading for my life among a crowd I believed would turn on me in an instant. As we sang along every night, I grew more desperate to escape. This honest, open, ever-smiling mass could not know I was gay. I was more scared of them than anything they preached.

If you’ve ever even been to church camp you know what it’s like—the singing and hand holding and crying. I dreamed of an Opheliac demise in the muddy lake just outside the chapel doors. The omnipresent persistence of youth pastors preaching purity and kids too happy to be believable was driving me mad. They, and the music that played on stage, were everywhere. At home, school, on the way to soccer practice. But I never went to the lake. Instead the song washed over me from the stage:

There is a fountain filled with blood Drawn from Immanuel’s veins And sinners plunged beneath that flood Lose all their guilty stains

V.

The night I came home from camp I waited till all the lights were off and I snuck into the kitchen to grab the grey-handled scissors from their drawer. Back in my bathroom I desperately I tore apart a 12-pack bag of BIC disposable shaving razors I had yet to need. Frantically I pried and picked and wedged the scissors in between the thin blades. Orange and disposable, it didn’t take long to break them apart.

It must have been a queer sight to the heavenly figures I believed were always watching me at the time. I sat on my toilet with my underwear over my knees, committing the edgy yet comparably safe alternative to teen suicide. The BIC razors became a weekly ritual. Panic, fear, and hatred would fester inside of me until I need to cut them all out to stop myself from crying.

Afterwards I would sit on the cold tile ask, “God, what have you done?” Sometimes to myself, sometimes not.

Several nights a week for years onward I would finish this act with a shower. The steam rolled throughout the bathroom like a fog as water reddened my chest and blood washed down my leg and through the drain. I got back in bed while the pillow was still wet with tears.

There is a fountain filled with blood Drawn from Immanuel’s veins And sinners plunged beneath that flood Lose all their guilty stains

VI.

Writing this I’m in a new house. My roommate has never been to my small hometown. He’ll never read this either. His house also flooded years ago in New Orleans.

The bathroom is my favorite room; it is of every house I inhabit, if even for just a night. They’re bright and varying, with pedestal sinks and colorful tiles. They offer privacy unjustifiable anywhere else. Your guard is completely down. You bare it all, forced to acknowledge every piece of yourself. All great horror scenes are in a bathroom because it’s the most intimate set for such a violation.

When I shower most things are the same. I still feel the hot water pepper my back. The steam still clogs my nostrils. Yet all that seeps through the drain is water. All that washes off of me is the day’s dirt. I still feel the vestigial wounds on my thighs; they remind me every morning of my past.

Changing in front of others I wonder if they notice. When I swim I watch for my shorts to gather up and expose me. When I have sex I wonder if the man below me can tell what they are as his hands run over them.

Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy him. For God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple1 Corinthians 3:16-17

VII.

On the eve of my eighteenth birthday I waited for the clock to strike midnight. My mother always told me “nothing good happens after midnight.” I always told her I was at a friend’s house, or I just slipped through my bedroom window.

Within minutes I was in my small town’s gay bar. The same bar that compelled my mom to vocalize her disgust every time we passed by. I sat at the tall, rickety tables with men I knew as well as myself, men I had never known before. Music drowned out all but the loudest shouts as drag queens whipped synthetic hair. I never wanted it to end.

VIII.

I rejoiced that Saturday night on the dance floor, numbness overtaking my brain in a way so familiar to nights spent drowning at home. The walls of my childhood prison were gone forever. The walls that watched me expose my deepest secrets and destroy myself were no more.

My sanctuary was gone, but so was what my sanctuary shielded me from. The flood was a victory. I spent years floundering, gasping for breath, sometimes thinking I would never resurface in that house. But the flood didn’t wash me away, only the sin I had left behind.

Ryan Thaxton is a 20-year-old from Monroe, Louisiana currently studying Mass Communications at Louisiana State University.

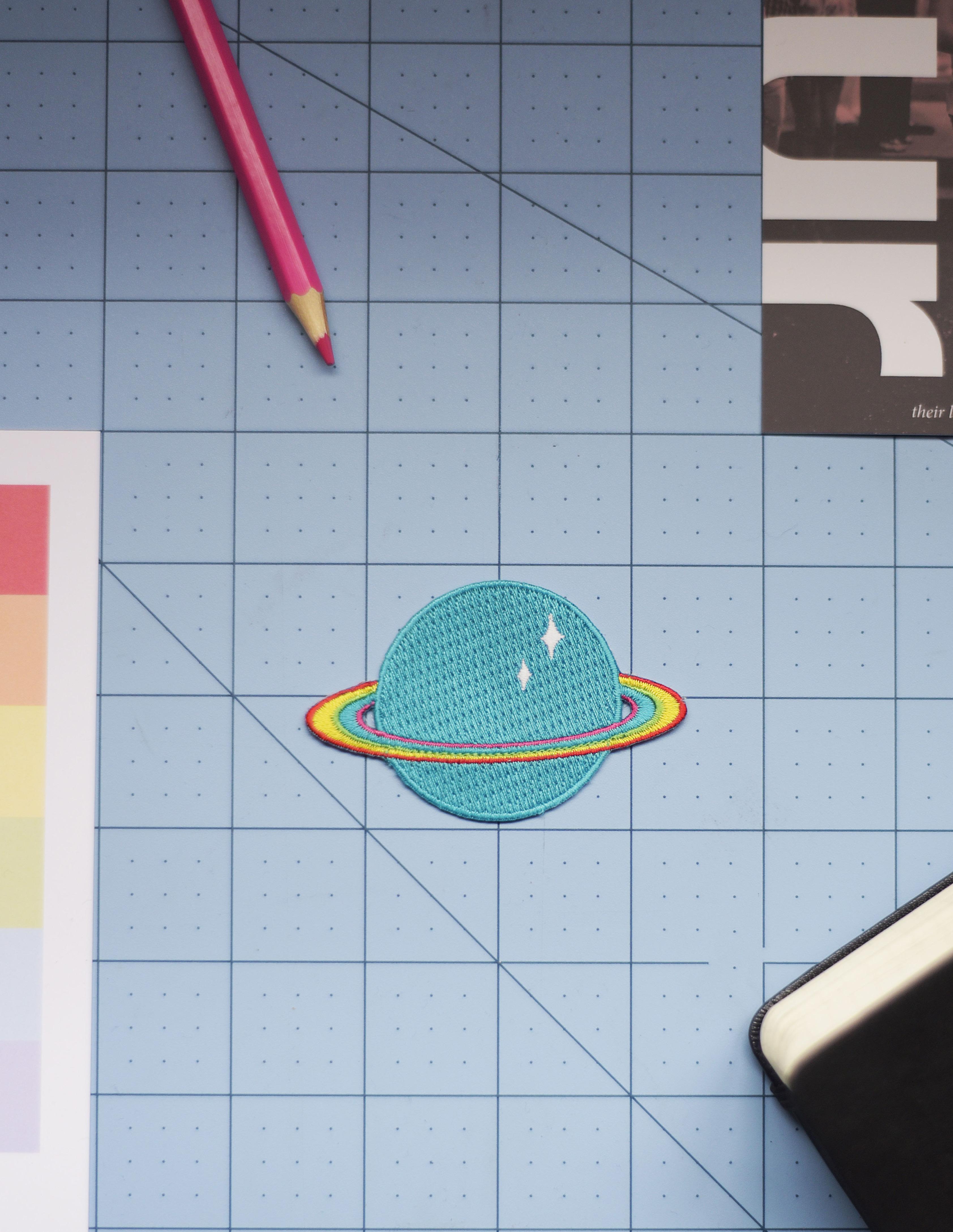

All The Men Who Never Had Sex With You

Written by : Ryan Rogers

There’s something you should know.

Very far away, there’s a planet in a galaxy you’ll never find. And on this planet there’s a single chunk of land in the middle of an endless sea. And on this tiny, jungled continent live all the men who never had sex with you.

You haven’t heard of this before because it’s kind of a secret. Because if someone had told you years ago that every man who turned you down or never gave you a shot in the first place was taken against their will to an alien planet lightyears away, you’d probably be an entirely different person. You’d probably be a lot more secure in your weight and in the imperfections of your smile. Who knows? You might even have a better job!

But still, you can take comfort in the fact that you live in a world where every man who agreed to sleep with you is still around and all the men who haven’t slept with you haven’t had the opportunity to say “No.”

This planet, the one on which every man who never had sex with you lives, is called Urloss and it’s not so bad. Every morning when the sun comes up, the boy to whom you wrote poetry for in the 7th grade goes fishing with the most handsome guy from your high school drama club. When the winds are calm, the lifeguard from 4H Camp wades into the surf to collect exotic shells in solitude. And every evening at sunset, the nice frat boy from that bar you used to go to freshman year with the impossibly chisel chest pulls out his guitar and plays the same set of Oasis, Aimee Mann, Sublime, and Jack Johnson, before closing with “Amber” by 311 and shuffling off to bed.

Members of this tribe vary in age and have virtually nothing in common except one thing: None of them ever had sex with you.

Just like they did on their home planet, the heavy drinkers still drink heavily on Urloss. Except here, they’re drinking an emerald-colored root sludge that lets them see sounds. These are all the men you met out in bars. Each one has his own story, but they collectively end in you getting turned down. So rest assured they’re way out beyond the stars — shrinking their balls with alien sludge.

The guys who never responded to your messages online make up an entire village on the west end of Urloss. They have

many sub-factions based on the social network on which you met them, but they still show solidarity as a unit. They try to stay busy. They’re just really busy.

Remember your friend for whom you developed feelings? Serious feelings? Feelings that were never reciprocated? Well, he’s here too. Yeah, that kind of sucks. I know you loved him, but it’s probably good for your “friendship” if there are millions of miles of permanent distance between you. And look on the bright side: His “Friend Zone” can’t extend all the way back to Earth, where you can enjoy going to a movie without the fear of running into him. Ever again.

On clear nights when all three moons are visible, the guy who excused himself to the restroom in the middle of your first date and never came back, likes to perch on the edge of a high cliff and think about jumping. He sits with his eyes closed and pictures himself scooting just a couple inches forward before pushing off with his palms and throwing his body onto the cluster of bayonet-shaped rocks below — finally giving him the escape he wants. You know he doesn’t deserve this, but it’s exactly the punishment you imagined when he left you alone at Tsunami with the bill and an “Oh, honey...” from the waitress, spoken with genuine sadness.

You’re probably wondering if any of these guys think about you or talk about you amongst each other. But the truth is, they don’t even know why they’ve been taken to Urloss. They haven’t yet discovered the common thread that binds them and they probably never will. So needless to say, the topic of you never comes up. But don’t be greedy. You’ve got a whole planet of men who wanted to fuck you or don’t know they want to fuck you yet. Which means you have a 100% closing rate among men you wanted to fuck. It’s perfect.

And you’re perfect. Just ask anyone.

Ryan Rogers is an award-winning author and copywriter with fiction and non-fiction published in The Huffington Post, Hello Mr. Magazine, Gertrude Literary Journal, HelloGiggles.com, Bird’s Thumb, and more. Essays by Ryan can be found at ExboyfriendMaterial.com.

Lesbian

In the last seat of the fourth pew, my bony knees are shrouded in God’s grace for an hour. Sunday morning makes them the most colorful part of me. Yellows, oranges, and reds from the window slat onto my flesh, and I shift, shying from the shades of Jesus’s glorious stained-glass face.

In Sunday School, I am told to use my finger to write in a small box of sand my sin and then pass my hand over it. My teacher says rubbing the words away will symbolize God’s forgiveness. I go to the box, make sure no one is watching me.

I write it.

This is the first time

I claim it. But I don’t, really. I’ve made it barely legible, and I start undoing it with my other hand before I even finish scrawling it—

The other children in church doodle their initials all over the Griefshare pamphlets. They scrape their names in the wood grain of the next pew.

I don’t etch myself into anything.

Claire Comeaux is a writer from Lafayette, Louisiana who currently resides in Little Rock. Her work has appeared in Scintilla and the Southern Literary Festival Creative Writing Contest Anthology.

As I, Do You

As I lay here in the dark im faded.

Fireworks outside the window throw color to the sky, I’m elated.

I can’t help but to think of those fireworks; those feelings you get when they burst into the air:

The chills. The passion. The happiness.

I too think of fireworks; not only the ones I see but the ones I feel.

The ones that I feel with you. The ones that I felt on the day I meet you.

The chills. The passion. The happiness.

Do you see those fireworks? Can you feel them?

You’ll know when you feel them, right?

Or will there just be too much smoke?

Anonymous

You Are Not Alone

In this city, everyone is gay, queer, fluid, label-free.

Here I am Baylea— writer of fiction, woman with cool hair, style.

There I was sir, young boy in blue jeans. Hair short, tomboy-girl with dirty fingernails.

Here when I am sir, it is question marked, trips out of mouths, picked up before it hits the ground. Red-faced shuffling and apologies.

There it is firm and sure, accusing or confusing. I am red-faced shuffling and apologies.

Here I am any other person on the subway. Here I am nobody worth noticing.

There I was talk-of-the-town, lone school lesbian. Quiet girl eating lunch in a bathroom stall.

Here they are all like me, and none like me. Here they accept and support, celebrate and ally.

So why am I still quiet girl eating lunch in an empty hall?

For the Love of Butches

We sit smokey eyed at window sills shielding our baby bird hearts, all feather and flutter and fragile trying to maintain our tough personas.

Wear our pleather jacket, tattoos, smile behind neatly festooned bow ties so nobody can see our grit, spit tucked into the front of chapped lips.

We hunch to hide what they think makes us women, buzz cut our hair, deepen our voices to blend into one side of the spectrum. As if we want to be men, Really we just want to shrink ourselves.

We sit smokey eyed and silent at those window sills, hoping to find a side to stand on, knowing we’ll always be disgusting wannabe-men to women and disgusting less-than-women to men.

Never the pretty girl, picked first, asked to dance by either sex. We’re the ones in the corners, freakshows, dykes, dirty old butches, the lesbians your mama warned you about.

We cry, drink, fight, hurt. Wounded, we carry on crooked smirks, shoulder shrugs, sweet head nods from the dark corners of the bar until she sees it.

For all the women that turned her head, that rolled her eyes, there’s this one that smiles back, walks over, shares a drink.

You start to think, this shit is worth it after all.

Baylea Jones is a fiction writer from southwest Louisiana. Her work has been featured in Dig Baton Rouge, Cactus Heart, and Marked by Scorn. At WNEU, she assists the MFA program, manages the social media, and edits for Common Ground Review. In her spare time, she enjoys bourbon, brunch, and burgers. Currently, she lives in Northampton, MA with her wife.

Issue 02 Submission Spotlight

Submit your artwork today to charlie@leurmagazine.com

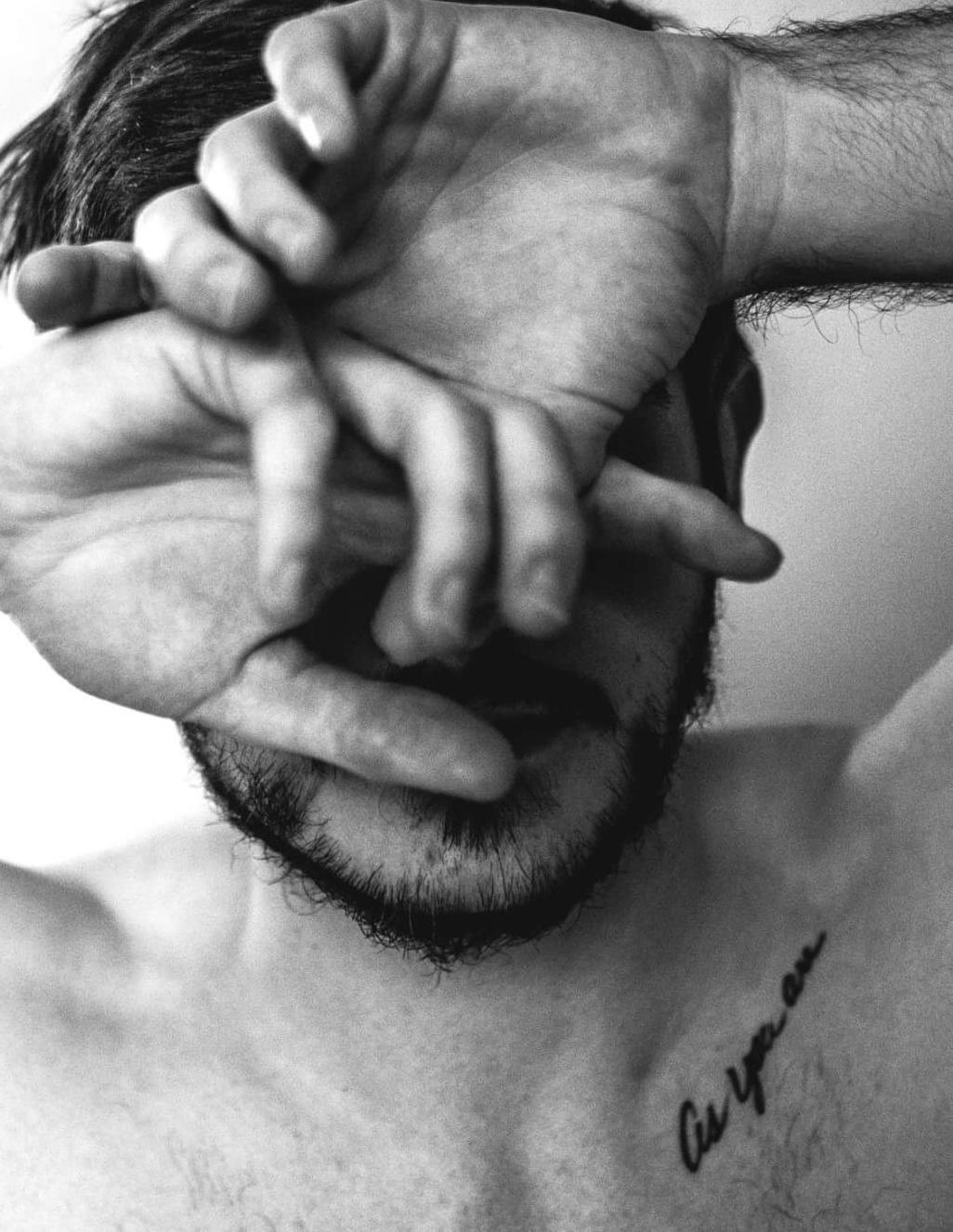

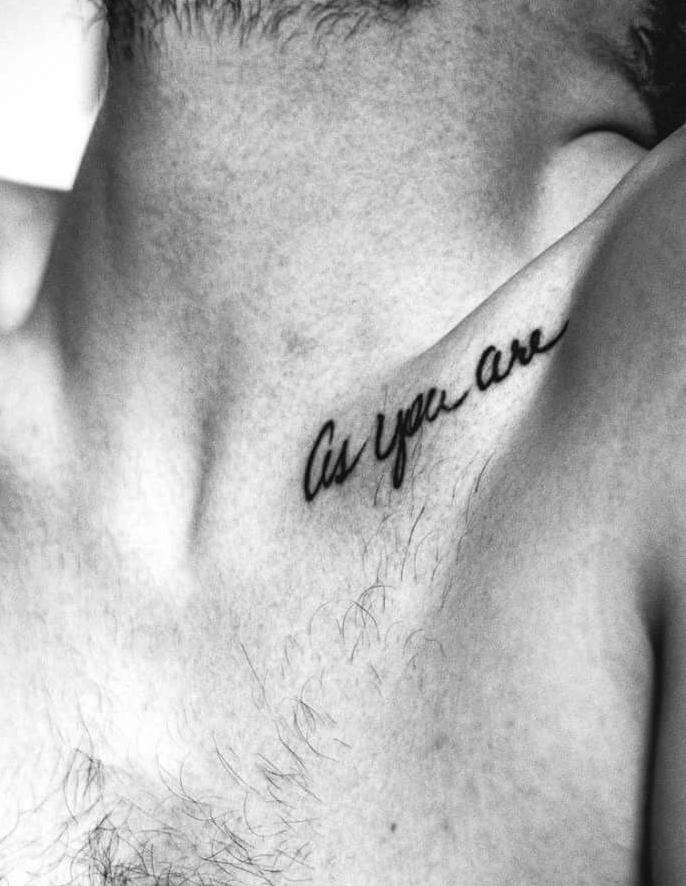

Photographer : Jake Brooks

Model/Stylist: Elliott Estelle

Title : StarPower

“This picture was created by me and my partner in our living room at 1 am. It started when I got the urge to paint green glitter under my eyes. We just played around from there, stum bling upon the light effect and picking up props from around the house. In photography, we have found an artistic medium that works for both of us, and brings us closer together. Whatever your urge is, explore it. You might find yourself a star.”

- Elliot Estelle

digital + printed issues available

Go and love someone exactly as they are. And then watch how quickly they transform into the greatest, truest version of themselves. When one feels seen and appreciated in their own essence, one is instantly empowered.

- Wes Angelozzi

Curator Charles Champagne

Director Devin Rogers Videographer Ashley Ann Estave

Lauren Duhon

Claire Comeaux Walker Dawson

& Katie Brauda

Thaxton Ryan Rogers Baylea Jones

Mathis Kane

Curator Charles Champagne

Director Devin Rogers Videographer Ashley Ann Estave

Lauren Duhon

Claire Comeaux Walker Dawson

& Katie Brauda

Thaxton Ryan Rogers Baylea Jones

Mathis Kane

Estelle

Estelle

photography : Sara Brauda + model : Walker Dawson

photography : Sara Brauda + model : Walker Dawson

Pound Of Flesh Mixes media on canvas

A Dance We Know The Moves Mixes media on canvas

Pound Of Flesh Mixes media on canvas

A Dance We Know The Moves Mixes media on canvas