GENDER, POWER, & CULTURE SEPTEMBER 2 0 2 2 ChariotVolumeV

Images and design by Maija Drezins

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we work, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations. We pay respect to their elders past, present, and emerging. Sovereignty was never ceded and this always was, always will be Aboriginal land.

i

Committee

Charlotte Allan Maija Drezins

Sunnie Habgood Julia Richards

Editors

Alice Wallis Elena Murphy Emerson Hurley Honor Rush Molly Lidgerwood Pamela Piechowicz Tahlia Antrobus

Contributors

Allegra McCormack Molly Lidgerwood Pavani Athukorala Sunnie Habgood Lachlan Forster Dominique Jones

Charlotte Allan Julia Richards Honor Rush Isabella Sweeney Maija Drezins Daniel Bird

Contributors

ii

Contents

AcknowledgementofCountry

ListofContributors

WordfromtheEditor

GenderFluidityintheLateMiddleAges:Acasestudyof SaintWilgefortis(AllegraMcCormack)

GenderPerformativityinEarlyModernEnglishTheatre (MollyLidgerwood)

HerProperty:WhiteWomenasSlaveMistressesinthe AntebellumSouth (PavaniAthukorala)

EloquenceandSilence:LeaningSocietalRolesofWomenin RenaissanceItaly(SunnieHabgood)

AmnestyforAll,SatisfactionforFew:ThePlanto'drawa line'beneathNorthernIreland'sTroubles(LachlanForster) Darkundark(AkankshaAgarwall)

UnderstandingtheSino-SovietSplit:TheGreatLeap Forward(DominiqueJones)

TheRelationshipBetweenMarriage,Reproduction,and FemalePowerinAncientGreeceandEgypt(Charlotte Allan)

LaughingattheMedieval:ArthurianLegends,Monty PythonandaKnight'sTale(JuliaRichards)

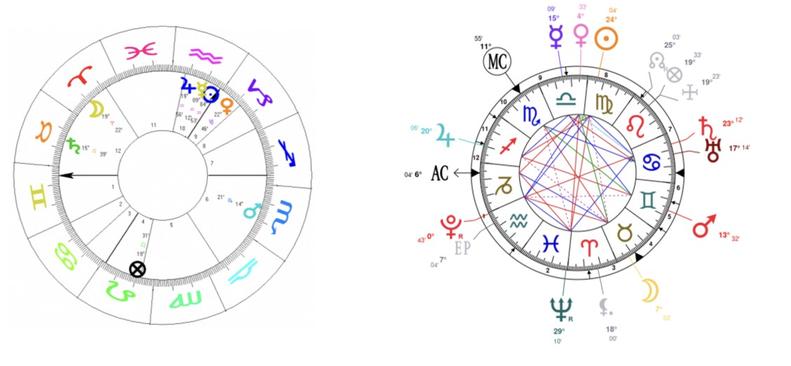

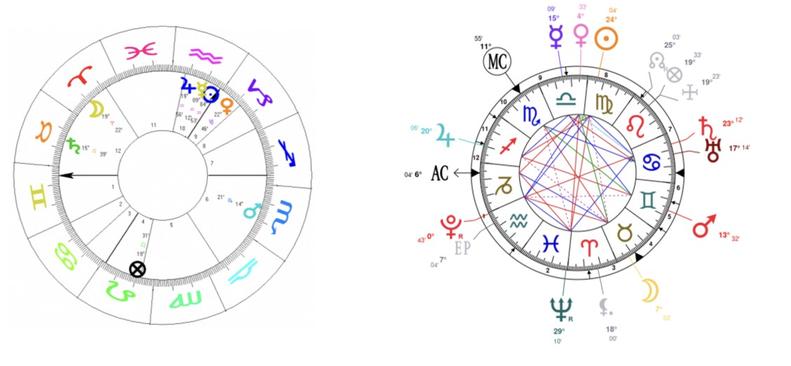

WhentheStarsSpeak:AComparisonBetweenQueen ElizabethI'sNatalCharttotheHoroscopeofherCoronation Chart(HonorRush)

ThePursuitofUnity:KantianMetaphysics, NaturphilosophieandHansChristianØrsted'sDiscoveryof Electromagnetism(IsabellaSweeney)

MusicintheDomesticSphere:MusicalWomenin Nineteenth CenturyLiteratureandMusic'sInfluenceonthe Domestic(MaijaDrezins)

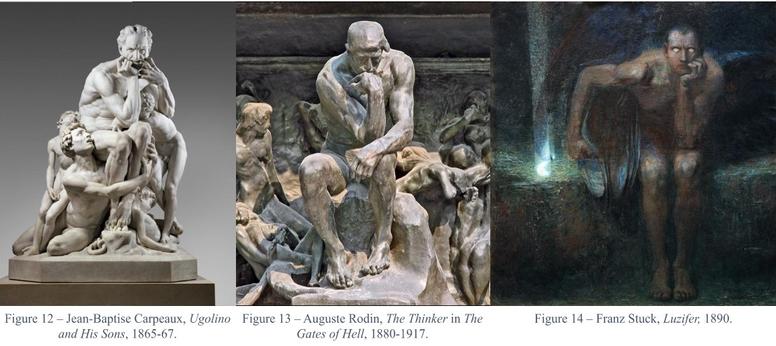

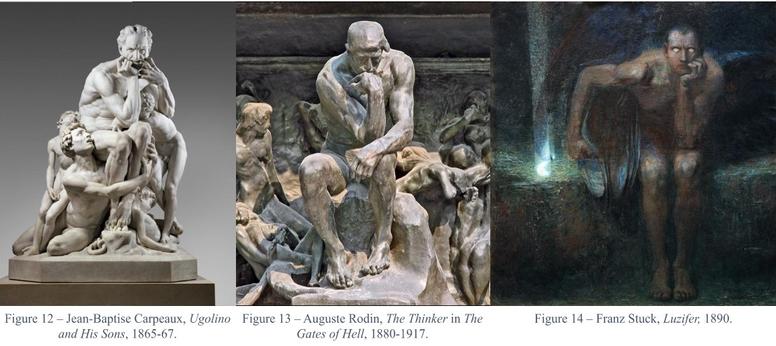

HeartonSleeve:TheNude,Morality,andtheGazeinthe Long19thCentury(DanielBird)

iii i ii iv 7 14 21 28 35 41 43 49 57 65 71 78 85

word from the EDITOR

The Chariot Journal has had another fantastic year in 2022 and we are very excited to share with you Volume V of our annual edition titled: Gender, Power and Culture. It has been a very exciting year for Chariot, particularly because we became an UMSU affiliated Club and have therefore been able to increase our membership, events and presence throughout the University of Melbourne. We thank all of our wonderful executive members, sub editors and contributors for making this year as exciting, intriguing and explosive as it has been. 2022 also provided the opportunity for Chariot to launch various in person events which reinvigorated our sense of community, spirit, and our shared love for history. We are also very thankful for the support of Dr. Julia Bowes and the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies in supporting us in all the work we do throughout the university.

Volume V of the Chariot Journal deals with some intriguing topics and issues relating to the themes of gender, power and culture within historical studies. This edition contains a diverse range of topics and include both academic essays and creative pieces, ranging from Allegra McCormack’s analysis of Gender Fluidity in the Late Middle Ages: a case study of Saint Wilgefortis to Honor Rush’s article When The Stars Speak: A Comparison Between Queen Elizabeth I’s Natal Chart to the Horoscope of her Coronation Chart. The themes of gender, power and culture are profoundly relevant and topical and we think that you will enjoy the marvellou tributors have produced. Turn the page al has to offer!

iv

GENDER, POWER, & CULTURE

v

Gender Fluidity in the Late Middle

Ages: A Case Study of Saint Wildefortis

Allegra McCormack

Allegra McCormack

7

Women were naturally colder and wetter than men, “whereas men were hot and contained.”

The growth of body hair was a physical manifestation of this two sex model as well as a symbol of masculinity. Indeed, the production of body hair was attributed to the balancing of male humours, as excess heat escaped through pores and facilitated hair growth. Within both models, as well as many theological constructions, the male was the ideal form, at the top of the sex hierarchy, whereas the female was considered an imperfect male. Physical transgressions, a visual crossing of the sex difference, were largely understood through the lens of disfigurement, and were subject to fascination and repulsion.

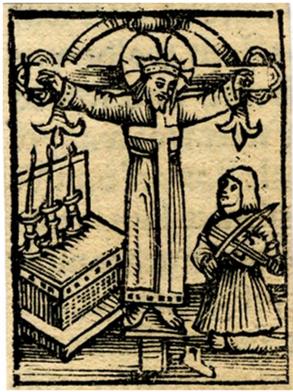

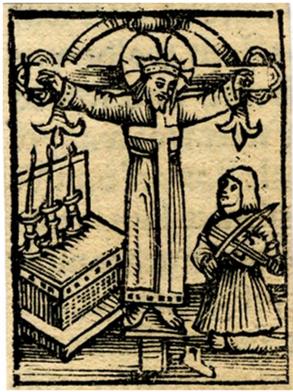

Fig 1: Adam Petri, Representation: Saint Wilgefortis, 1517, woodcut print, 44 x 32 mm, The British Museum, London Indeed, these observable occurrences were marked as an “unacceptable hybridity” belonging to the realm of the monstrous.

The legends of female bearded saints do, however, suggest that there could be a relationship between excess hair and female holiness. Gender fluidity within miracle stories could be understood symbolically and even uphold religious ideals of gender. Within late medieval Europe, the bearded St. Wilgefortis was a popular religious figure whose miracle story revolved around a divine act of gender fluidity. The image of Wilgefortis first appeared around 1400 as a ‘female crucifix’ and developed throughout the fifteenth century. The figure was usually depicted “ on a cross, wearing a crown, and often with a fiddler who serenades her from below.” Isle Friesen identifies the origin of St. Wilgefortis to a misinterpretation of a copy of Volto Santo. The image of a robed Christ was misperceived as a crucified, bearded female saint. Equally, Lewis Wallace argues St. Wilgefortis as a continuation of a series of “deformed” female saints which emerged in the thirteenth century. The later miracles stories of Wilgefortis had several common details:

A girl born to the pagan royal family of Portugal converts to Christianity and refuses to take a husband … Her father tries to force her into marriage and, upon her refusal has her imprisoned … [She] prays to God to be transformed to become physically unattractive to her would be husband so that she might remain a virgin bride of Christ alone. When Wilgefortis miraculously grows a full beard, her father has her crucified in a fit of rage.

8

For Wilgefortis, her beard is both a mark of disfigurement and symbol of divine protection. It is an intentionally monstrous, yet also miraculous phenomenon created by God that remains one of her most prominent features across varying depictions throughout the medieval and early modern period. As an example of divinely enabled gender fluidity within late medieval Europe, St. Wilgefortis encapsulates the complexity of sex difference as interpreted through a religious lens.

The legend of Wilgefortis, and the centrality of her act of gender fluidity, demonstrates the tension between medieval constructions of a gender hierarchy and the miracle stories of holy women. Gender was understood on both physical and moral terms, with female inferiority expressed within both Galenic and Aristotelian models of sex. Holy women, in achieving transcendence and overt divine favour, posed a challenge to this hierarchy. This theological problem could be remedied if holy women were understood as having ascended into the masculine side of the sex/gender continuum as personified through physiological characteristics. As such, Wilgefortis’ beard was perhaps an exhortation intended to portray masculine qualities, thus explaining her role within the gender hierarchy as well as visually bringing her closer to Christ. Several other saints also received the “divine gift of a beard” including St. Paula of Avila and St. Galla of Rome, while St. Mary Magdalene and St. Mary of Egypt were similarly described as having grown “fleeces of body hair.” Wilgefortis’ gender fluidity is also expressed within her actions as she seeks to protect her virginity and avoid the traditional social function of marriage through the protection of God accessible within a pagan court. These transgressions were similarly justified by constructing Wilgefortis as a more masculine figure. Some legends describe her as part of a set of septuplets and, being in the centre of the womb, having been exposed to “ a balance of heat and cold, which resulted in her having male attributes, such as the beard, and masculine qualities, such as distaste for marriage.” The de feminisation

Fig. 2: Jasper Isaac, Young Figure playing in front of the crucified body of Saint Wilgefortis, engraving, 1662 182 x 119 mm, The British Museum, London

9

of holy women, demonstrated through Wilgefortis’ gender fluidity, is a possible consequence of the conception of women as “ an afterthought of the creator” and theologically inferior to men.

Within the legend of St. Wilgefortis, this de feminisation was also conceived as a form of Christlike suffering. Rather than a painless, or even liberating expression of gender fluidity, her beard is intended to be repulsive and becomes the catalyst for Wilgefortis’ crucifixion. The beard of Wilgefortis is both a disfigurement and a divine gift from God. The radically transformative powers of Christianity are prominent throughout Christian doctrine; however, Wilgefortis’ transformation seemingly only increases her suffering. This paradox is reflective of the fifteenth century ideals popularised through the Imitatio Christi, a text that emphasised the importance of suffering as a means of spiritual purification. The text argues “the higher a person advances in spirit, the heavier crosses shall he often meet with.” The increasing suffering of Wilgefortis is a vital step for her eventual transcendence. While the prominence of the beard does vary between depictions, the crucifixion remains constant. This motif, in which Wilgefortis suffers “in cosmic unison with Christ on the cross,” reflects a common theme in which religious women’s bodies are directly associated with Christ’s. Wilgefortis’ body is, however, neither fully masculinised nor fully feminised. Her appearance and crucifixion tie her to the physicality of Christ, yet she is described as a woman, resulting in a blurring of her figure as a saint. Wallace argues Saint Wilgefortis embodies a multitude of characteristics from across the gender/sex spectrum: feminine yet virile, divine yet monstrous, Christlike and still a woman. This reveals the “fluidity and paradox common to late medieval religious symbols.” The gender fluidity central to her sainthood furthers Wilgefortis’ suffering as well as binding her closer to Christ.

In practice, St. Wilgefortis enjoyed considerable popularity as a saintly figure across Western Europe. Regardless of her legend’s origin it has been argued that her continued depictions were part of a deliberate effort to “transcend the ‘gender gap’ inherent to the crucifix.” Effectively, Wilgefortis’ gender fluidity could perhaps be utilised to promote a more universally applicable symbol of divine healing. Indeed, Wilgefortis assumed the role of compassionate protector. Sometimes referred to as St. Uncumber, she “would assist her faithful protégés in their final hour, so that they could die ‘ un encumbered’ by grief and anxiety.” Friesen argues that this role explains Wilgefortis’ inclusion as a

10

saintly protector within Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey. Perhaps due to her highly visible gender fluidity, Wilgefortis’ role as a saint was not always described positively. Within post reformation Britain, a growing connection between Wilgefortis’ patronage and women unhappy within their marriages was observed. In his Dialogue Concerning Heresies, Thomas More claimed that women referred to Wilgefortis as St. Uncumber “because they reckon that for a peck of oats she will not fail to uncumber them of their husbands.” Here, Wilgefortis becomes a threatening figure, her gender fluidity signalling her potential to allow other women to similarly destabilise the social order. Wilgefortis’ gender fluidity was both the driving force of her popularity as well a cause of growing suspicion. Miraculous gender fluidity was a complex act. Its divinity allowed for broad, often favourable, interpretations that reflected theological understandings of the sex hierarchy and divine favour. Like any depiction of social subversion, however, the ambiguity of Wilgefortis could be perceived as dangerous. The gender fluidity of Wilgefortis suggests that gender binaries were complex and multifaceted within late medieval miracle stories. While the prevailing sex models did enforce a relatively clear binary of gender roles, it is evident that there was space, albeit through legends, for some fluidity. It is crucial that Wilgefortis existed through symbolic representation, creating the possibility for varying interpretations as to the meaning of her beard. Gender fluidity is arguably defined through ambiguity, effectively informed by what it is not. Indeed, Wilgefortis was neither fully feminine nor fully masculine. This universality was possibly interpreted as purely metaphorical or understood as a more threatening transgression. Regardless, the legend of Wilgefortis reflects the stories of many holy women who adopted various forms of gender fluidity and ambiguity as central to their transcendence to sainthood.

Fig. 3: Untitled, 2019 Photograph Westminster Abbey. 11

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Kempis, Thomas A Imitation of Christ: In Four Books Edited by John Hodges Frome, England: Simpkin, Marshall and Co , 1868

More, Thomas A Dialogue Concerning Heresies: The Complete Works of St Thomas More Edited by Mary Gottschalk Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press, 1981

Isaac, Jaspar Young fiddler playing in front of the crucified body of St Wilgefortis Engraving 1662 182 x 119 mm The British Museum, London, https://www britishmuseum org/collection/object/P 1880 1009 1

Petri, Adam Representation: Saint Wilgefortis 1517 Woodcut print, 44 x 32 mm The British Museum, London, https://www britishmuseum org/collection/object/P 1932 0229 14

Westminster Abbey Untitled Twitter Post in Twitter Post January 10, 2019, 8:39pm https://twitter com/wabbey/status/1083297210861785088/photo/1

Wierix, Hieronymus Pietà with crucified female martyrs Etching on paper, 1609, 161 x 103 mm The British Museum, London, https://www britishmuseum org/collection/object/P 1863 0509 641

Secondary Sources:

Bailey, Anne E “The Female Condition: Gender and Deformity in High Medieval Miracle Narratives ” Gender & History 33, no 2 (2021): 427 447

Butler, Judith “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory ” Theatre Journal 40, no 4 (1988): 519 531

Cadden, Joan The Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages: Medicine, Science, and Culture Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993

Friesen, Ilse E The Female Crucifix: Images of St Wilgefortis since the Middle Ages Ontario, Canada: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2001

Gardener, Arthur English Medieval Sculpture Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2011

Hotchkiss, Valerie Clothes Make the Man: Female Cross Dressing in Medieval Europe New York, Routledge, 2012

Jasper, Alison “Theology at the Freak Show: St Uncumber and the Discourse of Liberation ” Theology & Sexuality 11, no 2 (2005): 43 54

Katritzky, M A “‘A Wonderful Monster Borne in Germany’: Hairy Girls in Medieval and Early Modern German Book, Court and Performance Culture ” German Life and Letters 67, no 4 (2014): 467 480

12

Kłosowska, Anna. “Premodern trans and queer in French manuscripts and early printed texts.” Postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 9, no. 4 (2018): 349 366.

Knippel, Jessi. “Queers Nuns and Genderbending Saints.” CrossCurrents 69, no. 4 (2019): 402 414.

Lacquer, Thomas. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992

Murray, Jacqueline. “One Flesh, Two Sexes, Three Genders?” In Gender and Christianity in Medieval Europe: New Perspectives. Edited by Lisa M. Bitel and Felice Lifshitz, 34 51. University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 2008

Wallace, Lewis. “Bearded Woman, Female Christ: Gendered Transformations in the Legends and Cult of Saint Wilgefortis.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 30, no.1 (2014): 43 63.

13

Gender Performativity in Early Modern English Theatre Molly Lidgerwood

14

.

the widely understood expectations of how people had ought to confine themselves to their respective genders.

The controversial pamphlets Hic Mulier and Haec Vir published anonymously in 1620 (but now assumed to be the work of John Trundle, an English publisher) epitomised the attitudes towards gender in early modern England. Hic Mulier condemned cross dressing as the “masculine women” were accused of making “ an asse” of the nation due to the connotations of “deformity” associated with gender ambiguity. For example, its title page displayed women getting their long hair cut off, destroying a symbol of modesty and inferiority (Figure 2). Short hair denoted masculinity in early modern England and consequently a woman with short hair elicited " a sense of shame", acc ording to Sandra Clark, as their needles were replaced with swords. Haec Vir similarly highlights the dangers of gender ambiguity as a couple in the opening scene meet and misidentified each other’s gender. The pamphlet ultimately argues that “shame…is a concept framed by men to subordinate women to the dictates of arbitrary custom.” Clark suggests that Trundle’s publications of these controversial pamphlets were an attempt to cause controversy by presenting a range of varying attitudes regarding gender in a way that mirrors the reality of gender performances which were fluid in the early modern period.

While cross dressing is explicitly condemned in the Old Testament of the Bible widely read in the early modern period, the theatre resisted gender binaries through their performances of ambiguous genders. English theatres employed all male casts unlike their European counterparts. This unique casting approach ascribed significance to the masculinity of the male bodies

Fig 1: The English Gentlewoman, Richard Brathwaite, 1631

Fig. 2: Opening Page to Hic Mulier, John Trundle, 1620.

Fig 1: The English Gentlewoman, Richard Brathwaite, 1631

Fig. 2: Opening Page to Hic Mulier, John Trundle, 1620.

15

and voices which performed a variety of genders in their plays. Playwrights such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe specifically employed young boys to perform their roles. For example, Nathan Field and Thomas Clifton were kidnapped and adopted into the theatrical world at only thirteen years of age, signifying the importance in finding young males with pre pubescent voices in order to signify the femininity of particular characters. Marlowe and Shakespeare wrote male and female roles for his boy actors, creating “simulated performances of women” which explored gendered relationships on the stage for the audience to witness. Henry Peacham’s drawing of a performance of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus reveals the subversive gender dynamics inherent in the performance as Tamora was taller than her Roman counterparts, even as she knelt submissively before the powerful Titus. Alison Findlay’s argument that the spectators of Titus “ were admitted to a hall of mirrors in which appearances, [and] gender identities…could be grotesquely distorted” reinforces that gender performances within early modern theatre were never stable and frequently subversive. Shakespeare often wrote “restricted” female roles for a small pool of his male actors. For example, Othello’s Desdemona was restricted to a limited number of male actors which ensured that the boys performing the role could master the performance of femininity in the tragedy. The example of Desdemona’s role also reveals the submissive nature of these female roles performed by male actors. For example, Henry Jackson’s recollection of an Othello performance notes how the murder of Desdemona “begged the spectators’ pity with her very facial expression,” highlighting the ability of these male actors to skilfully ingrain the patriarchal value of obedience into the memory of early modern audiences. Ultimately, these performances of femininity, led by young men, highlight the multifaceted and ambiguous representations of gender on the early modern stage.

The key signifier of fluid masculinity within early modern theatre was the voice of the actor. A squeaking voice demonstrated the boy actor’s transformation to developed man, which influenced the roles he played and the extent to which the performance of femininity was successful. In both female and male roles, the oscillating voice of the male actor was significant in igniting a sense of anxiety in an audience as the signs of masculinity became diminished, thus revealing the unstable gender boundaries in early modern England. While there have been minimal complaints recorded in this period regarding the physical appearance of male actors performing female roles, there have been recorded complaints related to these unstable voices. The voice of the male actor denoted the instability of gender and also connected their gender identities with a form of homoeroticism. Stephen Orgel’s contention that the dominant manifestation of eroticism in the early modern period was homosexuality is useful in analysing the performances of

16

gender by male actors. For example, the boy actors often were made sexually available by the theatre through a form of prostitution. As a result of this sexual indenture, the theatrical performances of the actors become linked to their roles as passive and available sexual partners for early modern spectators. Essentially, a boy actor who dramatised his identity through a female part constructed himself as a submissive, sexual, and consumable person, signifying the fluid gender and sexual identities in early modern England.

While male crossdressing and performances of gender blurred social conventions, female cross dressing, of both actors and characters, performed a similar function but was accused more frequently during the later years of King James’ reign in England. It is important to acknowledge the distinction between social cross dressing and cross dressing within the theatrical context; while the pair are connected, they are not the same. Cross dressing within plays provided an opportunity for playwrights, actors, and audiences alike to explore the fluidity of femininity within the confines of the theatre. For example, Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night is a play which provided female spectators the opportunity to witness layered gender disguise, as a male character would play the role of Viola who deceptively performed the role of Cesario. These complex performances of gender on the stage allowed actors to explore gender binaries but also explore the sexed female body. Viola/Cesario introduces herself to the Duke as “ an eunuch,” representing the lack of genitalia on the stage. This absence of female genitals in Twelfth Night suggests that Shakespeare used the one sex model which as a result solidifies the androcentricity of the early modern period. Twelfth Night therefore represents the early modern theatre’s preoccupation with blurred genders and associated sexed bodies. Contrastingly, The Merchant of Venice displays cross dressing that is socially disruptive as it resists “feminine subjectivity.” While The Lawe’s Resolution of Women’s Rights reminds us that “ women [had] no voice in parliament,” Portia’s manly disguise within the play’s courtroom is a powerful attempt of the character to assume control within the public and masculine sphere of the legal system. However, it would be false to argue that Viola or Portia’s cross dressing successfully resisted patriarchal hegemony in the early modern period. This failure is because firstly, the gender of the roles were performed by men which serves as a distancing mechanism; the power of the female characters was only a masculine façade. Secondly, as Orgel argues, the consequence of these subversive roles was not the deconstruction of patriarchy but rather, the arousal of male spectators whose reasoning became blurred and they consequently lusted after the men disguised in the cross dressing female’s costume. However, it is also important to consider that there were many female spectators in early modern theatres between 1567 and 1642. The early modern theatre provided an opportunity for women to see their flexible femininity

17

represented on stage, while also engaging with the erotic practices of the theatre possibly even including prostitution and intercourse. Thus, representations of femininity in early modern theatre were even more deceptive and fluid than their male counterparts.

Ultimately, performances of gender in early modern England were never stable. While the expected attitudes towards gender were made clear through Biblical texts and political pamphlets, the theatre provided an opportunity to blur gender binaries as actors and spectators engaged in a way that often resisted gender and sexual conventions. For example, the unstable voice and young age of male actors signified masculinity, or lack thereof, which resulted in fluid performances of constructed femininity. The mirror of disguises in Shakespeare’s plays revealed the messy performances of layered genders which resulted in the deception of early modern spectators and subsequently their fascination and eroticism of fluid genders.

18

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Brathwaite, Richard “The English Gentlewoman,” 1631 In Aughterson, Kate Renaissance Woman: A Sourcebook London: Routledge, 1995, p xvii

Edgar, Thomas “The Lawe’s Resolution of Women’s Rights ” Digital Library, 1632 https://digital library lse ac uk/objects/lse:sor474mew

Jackson, Henry “Excerpts from Henry Jackson’s letter recording a performance of Othello at Oxford ” Shakespeare Documented, 1610 https://shakespearedocumented folger edu/file/ms 304 folio 83 verso and 84 recto

Peacham, Henry Titus Andronicus illustration, 1595 In Callaghan, Dympna Shakespeare Without Women: Representing Gender and Race on the Renaissance Stage London and New York: Routledge, 1999, p 3

Shakespeare, William “Othello ” In William Shakespeare Complete Works, edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen, 2081 2157 London: The Royal Shakespeare Company, 2007

Shakespeare, William “The Merchant of Venice ” In William Shakespeare Complete Works, edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen, 413 471 London: The Royal Shakespeare Company, 2007

Shakespeare, William. “Twelfth Night, Or What You Will.” In William Shakespeare Complete Works, edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen, 645 697. London: The Royal Shakespeare Company, 2007.

Trundle, John. “Hic Mulier: or the man woman and Haec Vir: or the womanish man. ” Internet Archive.1620. https://archive.org/details/hicmulierormanwo00exetuoft/page/n9/mode/2up.

Secondary Sources:

Bartels Emily C , and Emma Smith Christopher Marlowe in Context New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013

Bloom, Gina Voice in Motion: Staging Gender, Shaping Sound in Early Modern England Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007

Butler, Judith “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory ” Theatre Journal 40, no 2 (Dec 1988): 519 531

Butler, Judith Gender Trouble London: Routledge, 1990

Callaghan, Dympna Shakespeare Without Women: Representing Gender and Race on the Renaissance Stage London and New York: Routledge, 1999

Clark, Sandra “‘Hic Mulier,’ ‘Haec Vir,’ and the Controversy over Masculine Women ” Studies in Philology 82, no 2 (Spring 1985): 157 183

19

Findlay, Alison A Feminist Perspective on Renaissance Drama Oxford: Blackwell, 1998

Gurr Andrew Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987

Howard, Jean E “Crossdressing, the Theatre, and Gender Struggle in Early Modern England ” Shakespeare Quarterly 39, no 4 (Winter, 1988): 418 440

McMillin, Scott “The Sharer and His Boy: Rehearsing Shakespeare’s Women ” In From Script to Stage in Early Modern England, edited by Peter Holland and Stephen Orgel, 231 245 London: Palgrave, 2004

Orgel, Stephen “Nobody’s Perfect, Or Why Did the English Stage Take Boys for Women?” South Atlantic Quarterly 88 (1989): 7 29

Orgel, Stephen Impersonations: The Performance of Gender in Shakespeare’s England New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996

Tribble, Evelyn “Marlow’s Boy Actors ” Shakespeare Bulletin 27, no 1 (2009): 5 17

20

Her Property: White Women as Slave Mistresses in the Antebellum South

Pavani Athukorala

Content Warnings: slavery, racism, and sexual abuse

That the Antebellum Southern belle, long mythologised as a wisp of delicate submission and refined piety, could bear witness and contribute to the barbarities of slavery seems unfathomable. Many scholars have, in fact, been loath to consider it. This essay, however, adopts a position favoured by more recent works in arguing that white women were slave mistresses in fullest sense of the word, whose relationships to enslaved persons were primarily ones of power and property, where their own privileged statuses depended upon the other’s oppression. Firstly, I summarise prior scholarship and outline how this essay departs from their methodology. I then focus on mistresses’ economic involvement in slavery, deconstructing the notion of slave ownership and mastery as masculine or patriarchal. I then outline the gendered ways in which white women exploited enslaved bodies, both for reproductive labour and sexual purposes. Finally, I consider the reasons why mistresses upheld a system that contributed to their own oppression, but also why many contemporary scholars have difficulty believing they did.

When not entirely ignoring their role within the ‘peculiar institution,’ twentieth century scholars generally depicted white mistresses as benevolent ‘closet abolitionist’ figures whose oppression under the Southern patriarchy they often equated with the sufferings of (particularly female) slaves. Marli F. Weiner argues that Southern paternalism tasked white women with providing slaves both material and moral ‘ care and guidance’ (that is, attending to enslaved people’s bodily needs and spiritual health), a responsibility most took seriously. She concludes that this resulted in some mistresses empathising with their slaves in ‘radical’ ways, humanising an inhuman institution. Vera Lynn Kennedy similarly argues that ‘shared female experiences’ such as childbirth and motherhood

21

brought mistresses and slaves together with ‘subversive, even radical implications.’ Even more recent scholars who are more cognizant of white women’s complicity in slavery espoused similar rhetoric. For example, Elizabeth Fox Genovese admits that mistresses were often ‘ more crudely racist’ than masters and shared little sisterly solidarity with female slaves. Immediately however, she undercuts this by rhapsodising about the ‘genuine personal concern and grief’ mistresses felt for slaves in a well intentioned but misguided attempt to depict them complexly. Mistresses’ personal writings (which the aforementioned scholars use extensively and almost exclusively) do reveal that many considered their relationships with slaves as mutually loyal and affectionate. But as bell hooks writes, allowing privileged persons like slaveholding women to interpret ‘the reality of…a less powerful, exploited and oppressed group’ such as their slaves is problematic for obvious reasons. If one instead uses evidence from slave narratives and the testimonies of former slaves, mistresses emerge (in striking contrast to their self characterisations) as calculating, authoritative and occasionally tyrannical figures. For these reasons, I too prioritise sources that allow the enslaved to define their own realities, against which I critically compare mistresses’ claims.

Firstly, as Glymph notes, the false dichotomy some scholars create between the ‘masculine’ public world of auctions and ‘feminized’ or sheltered plantations conceals the extent of white women’s economic involvement in slavery. In reality, no such firm distinction existed. As Low Country slave codes demonstrate, female mastery was specifically inscribed into the colonies’ legislature from their earliest days. One 1701 South Carolina law stated that slaves castrated for fleeing their ‘master, mistress or owner’ would be further mutilated for repeat escapes, while another from 1740 warned owners failing to provide slaves ‘under his or her charge, sufficient cloathing, covering or food’ they would be held legally responsible. Georgia’s laws threatened to fine the ‘Master, Mistress, overseer’ of any slave who was hired without an approved ticket. Clauses detailing other civic responsibilities of slaveholders, including contributing the colony’s militia and sending slaves to build public works, used similarly gender neutral language, specifically taking into account female owners. Female slave ownership existed and was acknowledged; in fact, because so many male heads of households died prematurely amidst the instability of colonial life, some women gained ‘unprecedented economic autonomy’ through it. These women independently managed large plantations, and freely bought, sold, bequeathed and hired slaves, which gave them the financial status to play important public roles within their communities. Well-aware that the Southern patriarchy was generally hostile to female autonomy, such single slaveholding women protected their precarious privilege by replicating the same racist hierarchies that enabled Southern slavery.

22

Nevertheless, as Stephanie Jones Rogers emphasises, slave mastery was not limited to the unmarried. Wealthy women entered marriage with slaves gifted to them by parents, and though legally, wives’ persons and property, enslaved or otherwise, belonged to their husbands, the reality was more nuanced. Some mistresses distinguished between their own and husbands’ slaves; former slave Silas Glenn remembered his mistress being ‘good to the slaves that come into her from her daddy’ but ‘mean’ to those from her husband’s side. Many firmly resisted their husbands’ attempts at managing, disciplining, or selling their enslaved property. White women who had grown up commanding slaves gained an internalised understanding of themselves as slaveholders (replete with the associated rights and responsibilities) and did not hesitate to assert this sense of independent ownership within their marriages. Some, such as Mrs. Annie Poore who sold slaves for ‘big prices’ after she ‘done trained them’ in specialised skills like cooking and carpentry, were acute businesswomen: true ‘mistresses of the market.’ Such women studied slave prices, exploited market fluctuations, and (contrary to popular belief) personally attended auctions, or hired male representatives to conduct such business on their behalf. In sum, both single and married slaveholding women gained economic power and personal agency within a repressive patriarchal system through the ownership and oppression of enslaved persons, whom they considered, first and foremost, as their property.

Secondly, while sources do not suggest that witnessing the sexual abuse of female slaves turned mistresses into sympathetic allies, it was actually quite the contrary. Powerless to stop men’s transgressions and suffocated by the hypocritical ideals of female purity thrust upon them, most turned a complicit blind eye or further abused the victims. Diarist and slave mistress Mary Boykin Chestnut, for instance, could call slavery a ‘ wrong and an inequity’ for the sexual disorder it produced and characterise female slaves as ‘prostitutes’ in the same sentence. Mistresses such as Boykin Chestnut self pityingly casted themselves as the sole victims of white men’s actions while extending little sympathy towards the enslaved victims. Instead, many reproduced racist stereotypes of Black women as animalistic, hypersexual, and complicit in their own abuse. Boykin Chestnut felt ‘faint, seasick’ witnessing a mulatto woman being sold for sexual purposes but described the woman as lasciviously ‘ogling the bidders’ with an ‘expanded grin of excitement.’ Others, especially on smaller plantations where mistresses were constantly confronted with evidence of their husbands’ infidelity, took their anger out on victims. In his famed autobiographical narrative, Solomon Northup remembers witnessing an enslaved woman named Patsey being ‘literally flayed’ due to her mistress’ jealousy. The mistress often persuaded her husband or other

23

slaves to whip Patsey out of spite, and even attempted to bribe Northup to murder her. As Natalie Zacek notes, though some have framed such erratic, emotionally motivated violence as somehow less severe than the systematic abuse often associated with masters, its unpredictable nature likely terrorised and traumatised slaves. Thus, most mistresses’ reactions to sexual abuse ultimately perpetuated the larger culture of racialized violence inherent to Southern slavery.

Moreover, mistresses themselves exploited enslaved bodies in various ways. Emily West and Rosie J. Knight use the thriving market for enslaved wet nurses to highlight how mistresses manipulated and commodified enslaved women’s mothering to serve their own needs. Mistresses’ reasons for employing wet nurses ranged from illness to vanity the fear that feeding would make their ‘breast fall,’ and become less aesthetically pleasing. Unlike slaves, mistresses had the privilege of choice in the matter, and their decisions determined the nature of enslaved women’s mothering. Harriet Jacobs, for example, remembers her mother being ‘weaned at three months old, [so] that the babe of the mistress might obtain sufficient food.’ Thus, mistresses placed their own desires and their children’s nutritional needs above enslaved women’s bodily autonomy, a uniquely gendered form of maternal violence. Moreover, while many fretted in personal writings about their own nursing related worries, not one reflected on the physical or emotional toll of forcing an enslaved mother to set aside her child for theirs. Mistresses also continually interfered in enslaved women’s parenting. Some supervised pregnancies, ministering home remedies, designating certain slaves to act as midwives, and occasionally deciding where births would occur. While this could be considered benevolent assistance, we cannot know how enslaved women felt about such intrusions into their bodies and intimate experiences. Neither was their interest in slaves’ reproduction wholly altruistic; a healthy child was a valuable commodity who could later be separated from their family and sold for profit. In sum, as Jones Rogers argues, shared female experiences like motherhood did not cause mistresses to ‘radically’ transcend societal norms. These instead became arenas where mistresses reconstructed racialized hierarchies to enforce their own privilege and power.

Thirdly, some white women also participated in the sexual abuse of male slaves. According to Thomas Balcerski, the conditions that fostered abuse between white men and enslaved women the availability of enslaved bodies, sex as a means of maintaining hierarchies of race and power also led to similar contact between mistresses and enslaved men. He notes that contemporary observers remarked quite offhandedly about this, for example Harriet Jacobs, who claims that seeing how female slaves were ‘subject to their father’s authority in all

24

things’, some mistresses learned to ‘exercise the same authority.’ Jacobs remembers a woman who chose the ‘most brutalized’ slave on her plantation as a partner, knowing she could most completely exercise her power over him, and evade the risk of capture. Admittedly, such relationships were a minority, but this example displays how white women understood, strategically used and often re enacted the hierarchies of race, sex and power around them. Importantly, sexualised abuse did not necessarily entail rape; Morgan comments that even daily encounters possessed a perversely ‘sexual dimension’ in the South because some enslaved people were forced to wear ‘little or no clothing.’ The display of particularly Black male bodies in the presence of upper class white women drew startled remarks from Northern observers, like one William Harding, who noted seeing enslaved men wearing only a ‘loose shirt, descending half way down their thighs’ waiting on ladies who did not express any ‘apparent embarrassment.’ Other violations of privacy included mistresses beating unclothed slaves (much in the same way masters did), or ordering them to massage or perform other intimate ministrations on their bodies. Some white women secured silence afterwards by threatening to accuse enslaved men of having raped them if they revealed anything, indicating that like their menfolk, they recognised and manipulated social stereotypes associating blackness with sexual aggression. Taken together, such examples exhibit how white women gained a certain transgressive power in a society that denied them sexual agency through the domination and violation of enslaved bodies.

In conclusion, while mistresses could and did treat their human property with basic decency (a bare minimum that has often been extolled as uniquely benevolent), they also held the power of life and death over their slaves. Slavery was not just a passive reality for white women, but a system based on power structures they actively upheld. Mistresses profited from the trade of enslaved people. They suffered minimal or no repercussions for inflicting sometimes unspeakable violence upon them in response to personal whims and jealousies. Some exploited enslaved women’s maternal labour to ease their own mothering, and others subjected enslaved men’s bodies to sexual violence. Of course, mistresses were also capable of genuine benevolence. Yet to focus on individual kindnesses over the systemic cruelty and exploitation that white women participated in, to insinuate that benevolence was ‘representative’ of white Antebellum womanhood as a whole, and to forget that these ‘kindnesses’ occurred within a power dynamic where one party was the property of the other, is to perpetuate the same stereotypes that kept slavery alive.

25

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

“Silas Glenn, Newberry, South Carolina, August 9, 1937 ” Library of Congress Accessed 15 June 2021 https://www loc gov/resource/mesn 142/?sp=140&st=text

“Tom Hawkins ‘She Beat On Them for Most Anything ” THIS CRUEL WAR Accessed 15 June 2021 https://thiscruelwar wordpress com/2017/01/05/tom hawkins/

Secondary Sources:

Anzilotti, Cara. “Autonomy and the female planter in colonial South Carolina.” The Journal of Southern History 63, no. 2 (1997): 239 268.

Balcerski, Thomas. Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men. University of Georgia Press, 2019.

Chesnut, Mary Boykin Miller. A Diary from Dixie. Harvard University Press, 1980.

Chesnut, Mary Boykin Miller. Mary Chestnut’s Civil War. Edited by C. Vann Woodward. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Dornan, Inge. ““Whoever Takes Her Up, Gives Her 50 Good Lashes, and Deliver Her to Me”: Women Slave Owners and the Politics of Slave Management in South Carolina, c 1691 1740 ”

Journal of Global Slavery 6, no 1 (2021): 131 155

Edwards, Laura F “At the threshold of the plantation household: Elizabeth Fox Genovese and Southern women’s history ” Mississippi Quarterly 65, no 4 (2012): 577 589

Foster, Thomas “The sexual abuse of black men under American slavery ” Journal of the History of Sexuality 20, no 3 (2011): 445 464

Fox Genovese, Elizabeth Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South University of North Carolina Press Books, 2000

Glymph, Thavolia Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household Cambridge University Press, 2008

Hodes, Martha White Women, Black Men Yale University Press, 1997

Hooks, Bell “bell hooks on Cultural Interrogations ” Artforum Accessed 15 June 2021 https://www artforum com/print/198905/cultural interrogations 34402

Jacobs, Harriet Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself, with “A True Tale of Slavery” by John S Jacobs Harvard University Press, 2009

Jones Rogers, Stephanie They Were her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South Yale University Press, 2019

26

Jones Rogers, Stephanie "‘[S] he could spare one ample breast for the profit of her owner’: white mothers and enslaved wet nurses’ invisible labor in American slave markets " Slavery & Abolition 38, no 2 (2017): 337 355

Kennedy, Vera Lynn Born Southern: Childbirth, Motherhood, and Social Networks in the Old South Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2012

Knight, R J “Mistresses, motherhood, and maternal exploitation in the Antebellum South ” Women’s History Review 2, no 6 (2018): 990 1005

Molloy, Marie S Single, White, Slaveholding Women in the Nineteenth Century American South University of South Carolina Press, 2018

Moore, Jessica Parker “”Keeping All Hands Moving”: A Plantation Mistress in Antebellum Arkansas ” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74, no 3 (2015): 257 276

Morgan, Philip D Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth century Chesapeake and Lowcountry University of NC Press Books, 2012

Northup, Solomon Twelve Years a Slave LSU Press, 2014

Tunc, Tanfer Emin “The mistress, the midwife, and the medical doctor: Pregnancy and childbirth on the plantations of the antebellum American South, 1800 1860.” Women’s History Review 19, no. 3 (2010): 395 419.

Weiner, Marli F. “The intersection of race and gender: The antebellum plantation mistress and her slaves.” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations (1986): 374 386.

Weiner, Marli F. “The intersection of race and gender: The antebellum plantation mistress and her slaves.” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 13, no. 1/2 (1986): 378 400.

West, Emily, and Rosie J. Knight. “Mothers’ milk: Slavery, wet nursing, and black and white women in the antebellum south.” Journal of Southern History 83, no. 1 (2017): 37 68.

Zacek, Natalie. “Holding the whip hand: the female slaveholder in myth and reality.” Journal of Global Slavery 6, no. 1 (2021): 55 80.

27

Eloquence and Silence: Learning and Societal Roles of Women in Renaissance Italy Sunnie Habgood

went against the ornament of silence that Barbaro mentions; hence, women must believe that eloquence and silence equate to each other eloquence therefore wasn’t seen as an achievable goal for Renaissance women. Women were, in On Wifely Duties, categorised as outside the learned class of society, as Barbaro enforces the contemporary attitude that women should be seen and not heard.

Furthermore, we must define what period will be discussed and give context as to what was happening during the Renaissance. Barbaro’s contemporaries did not believe they were living in a “renaissance” that term wasn’t coined until the nineteenth century, with Jacob Burckhardt’s The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy published in 1860. The etymology of the word Renaissance invokes ideas of rebirth as stated before, the Renaissance in Italy was categorised by a revival of classical ideals, which were mainly manifested through art, scholarship, and architecture. Italy during this time was forming independent governments, with periods of “relative freedom from foreign influences” that would later be marred by a succession of European invasions in the late fifteenth century. Italy was moving power from the hands of the nobility into independent governments (though it would later shift back into the hands of monarchies and foreign powers). Tensions between classes had been rife since the mid thirteenth century so, at the time of Barbaro’s writing, Italy was experiencing a period of general stability. On top of governments, the Church’s “moral prescriptions were enforced” by the Church as well as the laws of the states religion was, at this time, seen as the primary authority. We can see that the class system was being altered, as power was shifting; breaks from foreign invasions meant relative peace and stability for all areas of society; and most importantly, the Church was the authority on all moral and social issues, as well as natural law.

The “ornament of silence” named was a trait associated with femininity and therefore women at the time of the Renaissance. Historically, femininity and masculinity both social traits were equated with biological sex. According to Kent in their chapter “Women in Renaissance Florence” from Virtue and Beauty, gender was a social construct as much as a biological given, where women were “universally constricted in accordance with […] male needs”. Female destiny was entirely in the hands of men, as femininity and the virtue of silence became associated with women. This wasn’t a new idea in the Renaissance and stemmed back to Biblical times where Eve was believed to be created from Adam’s rib. Females were second to men from the time of creation Eve was created after Adam, and natural law in the Renaissance (perpetrated by the Church) stated that a hierarchy of creatures was established through the order of which they were created. Furthermore, Eve was seduced by the serpent, and in doing so influenced

29

Adam; she was sentenced to pain during childbirth and “the labour of motherhood”, and from then on women were “weak, foolish, sensual and not to be trusted”. This ties back to the belief that women should “honor themselves” with silence Eve’s sins followed women into the Renaissance, as did her creation after Adam, and there was no place for second class citizens in the realm of eloquence. Women were believed to have motherhood thrust upon them as a punishment, speaking to how their social position was cast in society.

This aspect of Christian doctrine was so engrained into everyday life in the Renaissance that chastity became the foremost virtue a woman could aspire to uphold, as they were pushed to do what Eve could not. Virginity and chastity were continuously brought up as a reason why women shouldn’t engage in eloquence or broader studies, linking into both their educations and their role in society. Let us first focus on how attitudes towards women’s learning were centred around the idea of chastity. In his infamous letter to Battista Malatesta, Leonardo Bruni discusses his belief that to women, “the intricacies of debate or the oratorical artifices of action and delivery” would never be of any practical use. Rhetoric in all its forms, Bruni suggests that it was “absolutely outside the province of women”, and they should primarily subscribe to “the whole field of religion and morals” as well as Church literature. Here another Renaissance man believes eloquence was an unattainable virtue for women to uphold and/or possess; rhetoric and eloquence were closely linked in humanist studies, as humanists strived to reinvigorate medieval rhetoric through eloquence. Eloquence in women was viewed as not only going against their nature, also as a sign of corruption of character. The rationale for this was that eloquence was a public activity according to classical Aristotelian thought, women “ were passive, irrational, opinionative, and inferior to man”, and therefore must be confined to the private sphere. Young females were discouraged from learning even Latin or Greek, as it was believed this could expose them to “obscene or frivolous literature”; girls’ educations were always designed to protect their chastity and virtue. As learned women would be exposed to lude materials, it was believed they couldn’t remain chaste while analysing classical texts, which is a key fact that shows how important chastity was. An important perspective on objections surrounding the attitudes towards women’s learning comes from Laura Centra, a prominent female humanist, in her letter to Bibulus Sempronius. Cereta is exasperated with Sempronius, who has labelled her as a “female prodigy” she believes that women “have been able by nature to be exceptional” but have had their opportunities limited. She goes on to list the names of many learned and brilliant classical women, whose achievements show that “nature imparts equally to all the same freedom to learn”. We can see that women were suppressed by their social

30

circumstances, and that those who had access to education wished for it to be more readily available. Both Bruni and Barbaro, by encouraging women not to become schooled in rhetoric and eloquence, reflect a key Renaissance attitude that higher education for women would be unsuitable for a gender that was supposed to remain chaste.

The reason for higher education being unsuitable was because it didn’t fit into the idealised role for women in society. One constant that overlaps with both women’s learning and their role in society was that all females, regardless of their social standing, were educated in domestic chores such as sewing and needlework. A woman was only supposed to master as much rhetoric “which would serve her for domestic purposes”; she would teach her children the basics of grammar and religion and leave the rest up to tutors or their father/male guardian. It was truly believed that women had nothing to contribute to society except in their role as a mother. Tying back into education, eloquence was a virtue only suitable for the public sphere, and we can see that a woman’s place was only in the private, domestic sphere. Silence was also a very large part of a woman’s life, particularly in relation to her husband. If women took the initiative during sex, it was seen as socially unacceptable they were taught to remain chaste and modest, “in the bedroom as much as elsewhere”, and expressing any form of sexual desire was deemed inappropriate. This tied back into the idea of the ideal woman remaining chaste, even throughout marriage.

A case which exemplifies Barbaro’s views, and shows his attitudes towards both women’s learning and their place in society is that of Isotta Nogarola, a Veronese noblewoman who is recognised by twenty first century scholars to have been a prominent fifteenth century humanist. Isotta’s eloquence in Latin became renowned throughout Italy by the time she was eighteen as she wrote to prominent humanists, but a theme that emerged from her praise was that she wasn’t a great humanist, but instead great for a woman. Her achievements were consistently equated to her gender, and in her famous letter to Ermolao Barbaro she self deprecates, writing “it may be very difficult to find a silent woman” in reference to herself, and acknowledging that her writings may seem “too verbose”. In an attempt to be taken seriously, Isotta had to acknowledge she was going against the norm of her gender against the lack of eloquence and silence Barbaro preferred. She further referenced Cicero and Virgil in the letter, making it known she’s skilled in Latin, which was yet another rebellion against the norm of

31

her gender. Due to her eloquence and this skill, she was a standout in her society, an oddity which many learned men had never encountered before. As put by Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine in “Women Humanists”, a fallout was inevitable: “triumphant warrior women all too easily become voracious, men eating monsters”. Isotta could not be a triumphant, learned woman without facing public backlash. Furthermore, engaging in higher education wasn’t her only wrong, as Isotta swore herself to celibacy and refused to marry. This went against the social expectation for women to wed, and an anonymous accuser would make accusations of sexual deviancy against her. As we discussed previously, chastity was the utmost virtue which a woman could aspire to uphold, however, it was genuinely believed that women couldn’t engage in humanism and live chaste lives simultaneously; it was therefore assumed that Isotta must have been engaging in sexual relations outside of marriage. She would later retreat from the humanist scene, instead devoting herself to the study of religious texts, which was seen as a more appropriate pass time for noblewomen. While her motives for doing so aren’t known, male humanists had not accepted her and, as a woman, and she most likely “lost courage when faced with the monumental task” of being taken seriously. Isotta was unmarried, educated, and had a public voice, going against Barbaro’s ideals expressed in On Wifely Duties, and the outcome of her life highlights the attitudes towards women’s learning and their place in society.

To conclude, the relationship between women’s learning and their place in society meant that the education of young women was limited. Barbaro’s statement reflects that silence and chastity were the main virtues a woman could uphold, and this attitude had age old roots and was perpetrated by Christian doctrine. If a woman was skilled in eloquence, they were going against their nature and the silence that was key to their roles in society. Isotta Nogarola, who summarised a woman going completely against her gender norm, suffered due to her skills in eloquences and had silence forced upon her as she retreated from the humanist scene. Women’s learning was clearly designed to serve their societal roles as mothers and wives.

32

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Bruni, Leonardo. “Praises Petrarch’s Rekindling of Antiquity, 1404”. Major Problems in the History of Italian Renaissance. Edited by Benjamin G. Kohl and Alison Andrews Smith, 26 29. Lexington: D.C. Heath and Company, 1995. In Renaissance Subject Reader, 216 221.

Cereta, Laura. “Letter to Bibulus Sempronius: A Defense of the Liberal Instruction of Women”. The Civilisation of the Italian Renaissance: A Sourcebook. Edited by Kenneth R. Bartlett, Lexington: DC Heath and Company, 1992. In Renaissance Subject Reader, 283 287.

Nogarola, Isotta. Complete Writings: Letterbook, Dialogue on Adam and Eve, Oration. Edited and translated by Margaret L. King and Diana Robin. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Secondary Sources:

Borsic, Luka, Ivana Shuhala Karasman “Isotta Nogarola The Beginning of Gender Equality in Europe” The Monist 1, no 98 (2015): 43 52 DOI: 10 1093/monist/onu006

Brown, Meg Lota, Kari Boyd McBride Women’s Roles in the Renaissance Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005

Brundin, Abigail, Deborah Howard, Mary Laven The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018

Den Hartog, Marlisa “Women on top: Coital positions and gender hierarchies in Renaissance Italy” Renaissance Studies: Journal of the Society for Renaissance Studies 35 no 4 (2021): 638 657 DOI: 10 1111/rest 12718

Grafton, Anthony and Lisa Jardine “Women Humanists: Education for What?” From Humanism to the Humanities: Education and the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Europe. Edited by Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine, 29 57. London: Duckworth, 1986. In Renaissance Subject Reader, 293 324.

Jordan, Constance. Renaissance Feminism: Literary Texts and Political Models. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Kent, D. “Women in Renaissance Florence”. Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, edited by D.A. Brown, 25 47. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001. In Renaissance Subject, 768 788.

King, Margaret L. “The Religious Retreat of Isotta Nogarola (1418 1466): Sexism and Its Consequences in the Fifteenth Century”. Signs 3 no. 4, 1978: 807 822. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173115

33

Kristeller, Paul Oskar “Humanism and Scholasticism in the Italian Renaissance” Major Problems in the History of the Italian Renaissance Edited by Benjamin G Kohl and Alison Andrews Smith, 285 296

Lexington: D C Heath and Company, 1995 In Renaissance Subject Reader, 238 251 “Meaning of eloquence in English” Cambridge Dictionary, accessed June 2022 https://dictionary cambridge org/dictionary/english/eloquence

Najemy, John M Short Oxford History of Italy: Italy in the Age of the Renaissance, 1300 1550 Edited by John M Najemy, 1 17 Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005 In Renaissance Subject Reader, 2 14

Rocke, Michael “Gender and Sexual Culture in Renaissance Italy” The Renaissance: Italy and Abroad Edited by John Jeffries Martin, 139 158 London: Routledge, 2003 In Renaissance Subject Reader, 813 832

34

Amnesty for All, Satisfaction for Few: The place to 'draw a line' beneath Northern Ireland's Troubles

Lachlan Forster

35

Proposals of amnesty for those who contributed their efforts towards violent struggle during periods of upheaval are not unfounded. The most famous and effective enactment of such legislature was the ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission’ within South Africa, established by Nelson Mandela to record testimony and shed light on the crimes of the apartheid system. This commission had the ability to grant amnesty, and complete protection from prosecution for former political offences, to those who had propped up the apartheid system, as well as to those who had committed crimes whilst aiming to take down said governmental framework. While not entirely without blemish, this act of amnesty not only ‘generated a great deal of information if not truth’, but was also a massive contributor towards ‘reconciliation in South Africa’ , ‘moving the country towards a more democratic future.’ So, if such a proposal could work to heal the deep wounds left by the apartheid system within South Africa, what stands in the way of such a proposal working to put the troubles in the past once and for all?

South Africa’s reconciliation and subsequent amnesty grants centred on the fact that the system of apartheid and the majority of the groups that fought for it were a thing of the past. As Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress took power within the state, it was evident that his political faction had ‘won’ the apartheid struggle. But the troubles did not have such a definitive victory for any party. The Good Friday agreement was a negotiated settlement between every party, hashed out between the British crown, members of the republican Sinn Féin, and representatives from the Democratic Unionist Party. Each entity had to make concessions for peace, but none of them ceased to exist, continuing to campaign for their respective political ideals, but with an agreement that Northern Irish politics should centre on civility rather than violence. The struggle of amnesty with these conditions is that as each character from the troubles continues to exist in the modern day, they still maintain their actions within the conflict were unquestionably just, demanding justice for those who suffered on their side whilst also conveniently turning a blind eye to their own party’s poor conduct. A condition of amnesty in South Africa was an admission of guilt for crimes, asserting that in order to achieve forgiveness in the post minority rule nation, one had to admit fault. But this ask will not be met by any of the parties within Northern Irish politics, demonstrated by an overwhelming backlash to Westminster’s amnesty proposal from all five major political parties in Ulster, victim groups, families of the deceased and British servicemen. All of them have rightful cause to be angry and hurt by what happened during the troubles, but the notion that they need to be forgiven is completely foreign. Their justifications are as follows:

36

Republicans: The republican cause in Northern Ireland was the most passionately supported independence movement in the world due to widely publicised events of suppression that grabbed headlines, carried out against the minority Catholic community in Ulster. The aforementioned Bloody Sunday followed riots in 1969, that demanded civil rights for families being forcibly evicted by Protestant landlords and communities. Subsequent decades would also see hunger strikes within prisons by convicts who asserted that they had been denied proper trials and the human rights that detainees are entitled too, including mail from loved ones and time outside their cells. Maeve McLaughlin, manager of the Bloody Sunday Trust, explained that many Catholics in Northern Ireland ‘can’t just draw a line and forget’ the oppression they and their families experienced, and that ‘putting the truth out there’ was essential to promote the suffering of her community during this period. The latter quote refers to the legislation’s barring of legacy inquests, that would end the search for answers for the families of those who lost their lives in uncertain circumstances during the period, with said families being left to rely on the conscious of those who were granted amnesty to come forward and confess to their crimes. These points are backed by Sinn Féin, the Republican Party of Northern Ireland who wholeheartedly maintain that those who maligned Catholics should be prosecuted. Furthermore, Sinn Fèin successfully campaigned for Bloody Sunday to be recognised as an unlawful act of aggression, resulting in British Prime Minister David Cameron apologising for the event in 2010 on behalf of the crown, stating Great Britain was ‘deeply sorry’. But Sinn Féin was not a helpless victim throughout the troubles, and their passionate campaigning for the martyrdom of the republican cause is undermined by their paramilitaries own actions during the conflict.

Unionists:

Of the 3,500 murders during the troubles, 60% were committed by republican paramilitaries, the primary of which was the notorious Provisional Irish Republican Army, or IRA. The majority of the organisation’s targets were unionists and British military servicemen who had been stationed on the streets of Northern Ireland. Frequently however, their actual victims were innocents who had become unknowingly caught in the crossfire of the IRA’s campaign of terrorism. For example, the assassination of Lord Mountbatten in 1979, a member of the royal family and distinguished military serviceman, was further muddied by the deaths of the Lord’s 14 year old grandson and a 15 year old boy who had been caught up in the bombing. Whilst this case centres on the royal family, situations of this creed were common for unionists in Northern Ireland, who felt they had to protect their communities from the radical, and often messy IRA. Skepticism around paramilitaries seeking reunification of Ireland unfortunately

37

contributed to farther persecution towards Catholics, as the Protestant population of Northern Ireland turned the troubles into an issue of patriotism; the North was for protestants who wanted to maintain their joint Irishness and Britishness, and if the catholic population were not happy with the conditions of the region’s existence, they had an entire republic to the south they could populate. This segregationist logic underpins the unionist issues with the proposed amnesty legislator, namely that those seeking to cause political disruption within a purposefully autonomous region of Ireland, should be brought to justice for their murder of innocents, not excused on the grounds of having a political cause.

British Armed Forces: The sight of servicemen strolling the streets of Belfast and Londonderry was commonplace during the troubles, as the military was instructed to stay alert for threats from the IRA and keep the peace between the unionists and republicans. Of course, this often met with mixed results; some days the peace could be kept easily, and the people of Northern Ireland were free to go about their business, other days the negligence of the armed forces could result in a situation like Bloody Sunday. The primary issue that most armed forces personnel have with the amnesty legislature is that it implies wrongdoing on the part of the military, with most soldiers having simply been assigned to Northern Ireland and kept the peace effectively. This sentiment is backed by the group, ‘Families Acting for Innocent Relatives’, an organisation promoting the prosecution of terrorists for their murder of innocents, which stated they ‘do not wish to see the perpetrators of heinous crimes seen on an equal parallel as police officers and soldiers who were trying to maintain peace at a time of rioting and mayhem in Northern Ireland’. However, the issue with this stance is not the perceived guilt of the average serviceman, but rather the culpability of the higher command in providing weapons and support to unionist paramilitary groups in an attempt to combat the IRA. In other terms, the commanders and generals of the British army lowered themselves to the IRA’s standard in combatting their messy form of rebellion with an equally hazardous and unfocused violent response, leading to the maiming and deaths of further innocent Northern Irish citizens.

To simplify this situation, it can be said that each party from the troubles wants to see justice for their own that had been harmed or killed during the conflict, but do not want to admit to any wrongdoing on their part and believe that their own violence should be excused on account of their perceived politically valid cause. All parties take issue with the legislature, none want to forgive, and all want justice. As most things in politics are, the answer to what should happen with this issue of the continuing legal status of the troubles is wrapped in a paradox.

38

The notion of amnesty is a frustrating one, as most of us would maintain that people should be punished for their crimes and said punishment should not be beholden to a ‘ use by’ date. Furthermore, some courts have found that amnesty laws violate fundamental constitutional rights within most first world nations, including ‘the rights to life, liberty and judicial protection’, and imply that crime is allowed so long as it is done for politically murky reasons, and you keep your guilt a secret past the statute of limitations. But, as the troubles pass further into history, and those with a firsthand memory of the conflict grow older, it becomes evident that something must be done to put the rivalry between Protestants and Catholics into the past, continuing towards a united Northern Irish community. No one is asking victims’ families or veterans of the conflict to forgive those responsible for heinous crimes, but the blanket amnesty agreement instead seeks to create a level playing field. This acknowledges that the prospect of innocence will likely bring about answers to the unsolved cases of death and violence through convenient means, and place both communities on an even level within society, delivering the statement that no one in the modern day is any longer responsible for the atrocities of the past, and the era of the troubles.

To acquit each side of this conflict is not to deny justice and proper remembrance to those lost, but an effort to rebuild Northern Irish society. This would free the two communities, separated for so long by mutual blame and prejudice, from the branding of being responsible for the atrocities of the troubles. Perhaps this deal is not the proper manner of going about this, and all interested parties certainly need to be consulted on the matter. But with nearly a quarter of a century passed from the end of the conflict, it is certainly time to draw a line beneath the troubles, and that will require forgiveness in any manifestation.

39

Bibliography

BBC ‘Plan to end all NI Troubles prosecutions confirmed’ July 14, 2021 https://www bbc com/news/uk northern ireland 57829037

Gibson, James L ‘The Contributions from Truth to Reconciliation: Lessons from South Africa’ Journal of Conflict Resolution Vol 50, no 3 (June 2006): 409 432 Doi: https://doi org/10 1177/0022002706287115

Cameron, David ‘The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on the findings of the Bloody Sunday report’ Speech, House of Commons of the United Kingdom, Westminster, Great Britain, June 15, 2010

Webber, Jude ‘Amnesty Row clouds Bloody Sunday 50th Anniversary in Northern Ireland’ Financial Times, January 29 2022 https://www ft com/content/a54c3f33 7924 4ad9 b82a 2d91f6584948

Sutton, Malcom ‘An Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland’ Ulster University Cain Archive Published November 13 2007 https://cain ulster ac uk/sutton/tables/Status html

Roht Arriaza, Naomi and Gibson, Lauren ‘The Developing Jurisprudence on Amnesty’ Human Rights Quarterly 20, no 4 (1998): 843 885 Doi: https://www jstor org/stable/762791

Brendan O’Leary and John McGarry. The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland. Bloomsbury Academic: London, 1996.

Bosi, Lorenzo. ‘Explaining Pathways to Armed Activism in the Provisional Irish Republican Army, 1969 1972’. Social Science History 36, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 347 390. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S014555320001186X.

40

D a r k u n d a r k A k a n k s h a A g a r w a l

ApoemabouttheRadiumgirls. eyesfallonbreath’sbeat, time. sun dialshines, awomaninside. thatradiumglow silence. stickyglow splashedacross nails teeth lips two fiftywatchfaces until jawssplit, bonerots, bodiesend. theyknew. syphilis dignity’sdownfall. fiftylivesforadollar aman’sdeathforaverdict thefireinfive women insuredawildfire. ilookup underalostepitaph, nightsstillglowinthedark.

41

42

Photo

credit: Timothy Dykes, Blacklight/UV reactive paint, Photograph, January 2020, Unsplash, https://unsplash.com/@timothycdykes.

Understanding the Sino-Soviet Split: The Great Leap Forward Dominique Jones

Russia China relations have undergone many ebbs and flows. One of the most contentious periods of Sino Soviet relations began at the introduction of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) Great Leap Forward in 1958. The Soviets’ disapproval of the Great Leap Forward initiated discontent with the Chinese Communist Party which precipitated the Sino Soviet split. This article will examine the reasons which underpinned the Soviet Union’s dismissal of the Great Leap Forward. The Great Leap Forward thrust the Sino Soviet relationship into an antagonistic standstill where jabs were delivered by both leaders in a bid to undermine the other.

It must first be acknowledged that the Soviet Union’s disapproval of the Great Leap Forward was not immediate. The Soviets expressed praise for the contributions the Great Leap made to socialist theory and practice. During a visit to China in the Summer of 1958, Khrushchev commented that the Soviet Union had ‘ no doubts’ about China’s ‘ability to fulfil these plans.’ Thus, at the outset, the Soviets eagerly validated the Great Leap Forward and the ‘enthusiasm and vigour’ of the Chinese people in pursuing the advancement of socialism. Such approval was maintained by the Soviets until as late as June 1958. Whilst the sincerity of Khrushchev’s remarks has been questioned, with some claiming his compliments were given blindly, it remains that the Soviets did not publicly disapprove of the Great Leap immediately. It was only until late 1958, when concerns regarding the people’s communes grew, that the Soviet Union’s accolades dissipated.

However, the end of Soviet public praise did not necessarily result in the outright criticism that would later transpire. In late 1958 the Soviet Union recognised the need to maintain the socialist bloc’s image of unity, leading to the decision to conceal its concerns regarding the Great Leap. A politburo study group

.

43

attests to this, outlining that the USSR’s publication of its concerns regarding the leftism of the communes would ‘widen the divergence between the two parties.’ A disunified socialist camp would be vulnerable to the polemics of Western powers. Therefore, even as doubts grew among the Soviet Union’s leadership about the feasibility of the Great Leap Forward, these remained private. The USSR only then publicly and explicitly voiced its disapproval of the Great Leap Forward after the PRC began to acknowledge problems itself in the last few months of 1958.

The Soviet Union, under Khrushchev, was disgruntled by the Great Leap Forward’s rejection of orthodox Marxism. Mao’s goal of bypassing socialism to enter communism through a concentrated period of accelerated production violated what the Soviets considered the immutable laws of Marxism. These immutable laws were reiterated in Khrushchev’s 1957 Moscow Declaration which pronounced socialist construction must be ‘gradual’ and that ‘national development should be planned.’ The rash advancement of surpassing the greatest economic powers Mao sought to achieve through the Great Leap was diametrically opposed to Khrushchev’s ‘basic laws.’ Khrushchev despised Mao’s belief that historical materialism was negotiable and should be ‘rewritten,’ noting that under Mao ‘the Chinese interpret Marxism Leninism any way they please.’ The ambitions of the Great Leap sought to reconstitute Marxist theory on socialist construction, much to the dismay of the Soviet Union. Thus, the Soviet Union categorically rejected the Great Leap Forward as being unfounded in the pure Marxist tradition.

The Great Leap Forward’s resurgence of a Stalinist model of economic development also unsettled the Soviet Union. The collectivisation of domestic items and consumption was received negatively by the Soviets. They saw the act as an abominable and unnecessary repeat of the mistakes of Stalin’s commune experiment. Mao’s unforgiving Stalinist posture was growingly irreconcilable with Khrushchev’s policy agenda of de Stalinisation and peaceful co existence. The Great Leap Forward exemplified Mao’s discontent with what he believed was Khrushchev’s bourgeois back sliding thathad led the USSR to become complacent. Such complacency, for Mao, was vested in the USSR’s relatively unambitious industrial targets which Khrushchev estimated would see the Soviet Union reach communism by 1980 at the latest. Thus, Mao’s scheme to hasten the path to communism was antithetical to the USSR’s adherence to gradual growth. Whilst Khrushchev attempted to remove the Stalinist legacy from the socialist movement, Mao sought to reinvigorate Stalinism through the labour intensive methods of the Great Leap. The Great Leap Forward’s attempt to ‘out Stalin Stalin’s economic policies’ was in direct contradiction to the new conciliatory

44

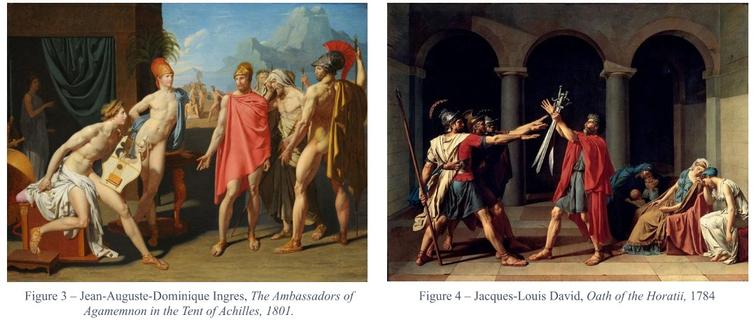

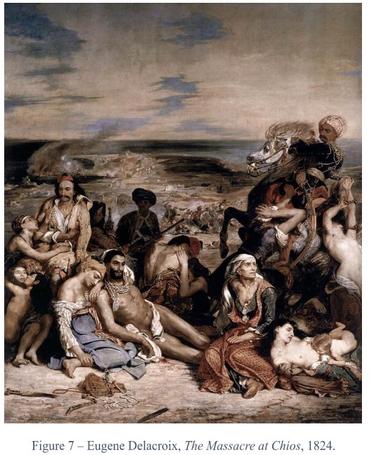

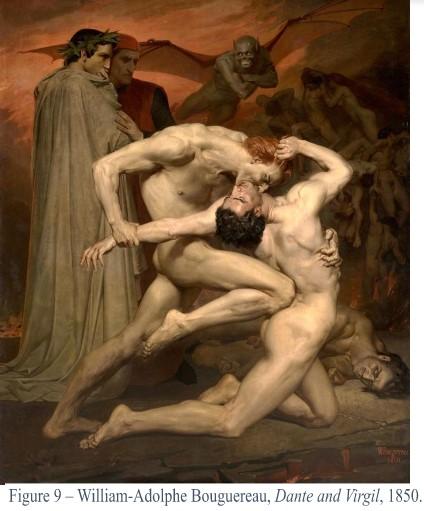

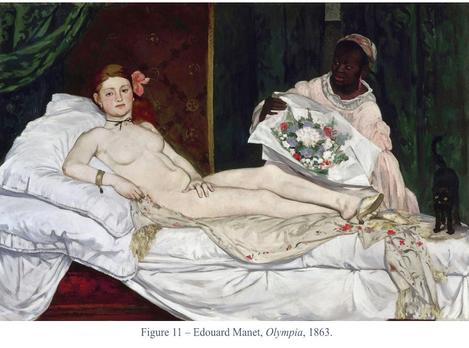

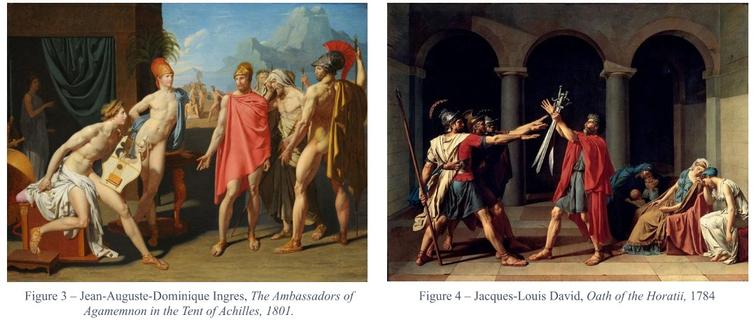

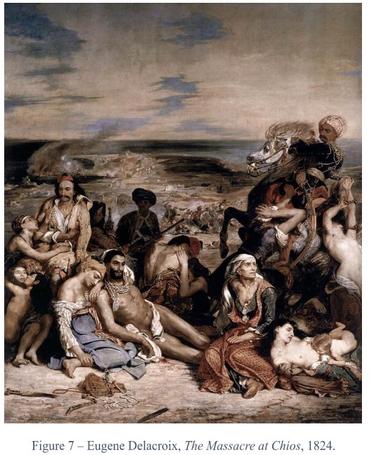

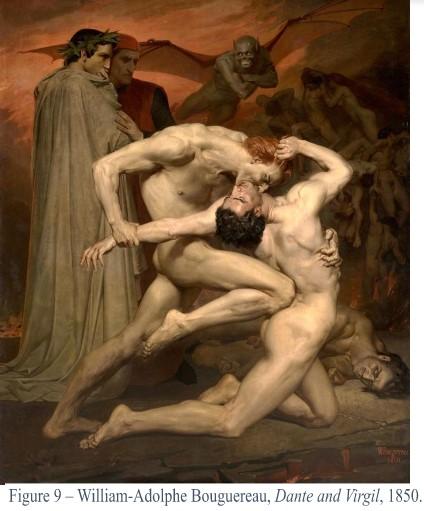

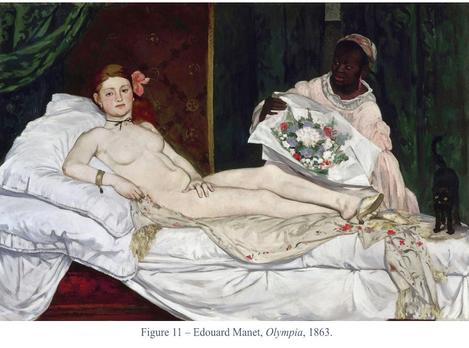

path Khrushchev sought to pursue.