CHABAD JEWISH LEARNING CENTRE

AUGUST 24 SEPTEMBER 22

Elul is the final month of the expiring Jewish year. It is a time for introspection and contemplation, for an honest reckoning of missed opportunities, and for careful consideration of ways to advance during the coming year.

SEPTEMBER 22—24

Rosh Hashanah is the anniversary of the creation of Adam and Eve. It is the launch of the human story. On this date each year, we remind ourselves that G-d created us in His image to fulfill a critical mission of partnering with Him to perfect His creation.

Can you name three reasons for the blowing of the shofar?

Answer on pp. 12–13.

SEPTEMBER 23—OCTOBER 2

Maimonides taught, “Although teshuvah (returning to G-d) and calling out to G-d are desirable at all times, during the Ten Days of Repentance these activities are even more desirable and will be accepted immediately.”

What does teshuvah mean?

And how is it accomplished?

Answer on p. 20.

OCTOBER 2

The Torah informs us (Leviticus 16:30) that the presence of this date itself and the Divine disclosure that it conveys atones for our sins. Nevertheless, the sages of the Talmud clarify that this atonement depends on teshuvah—our return to G-d through sincere regret for shortcomings and a sincere commitment to doing better.

Why is the Tenth of Tishrei designated as the Day of Atonement?

Answer on p. 17.

OCTOBER 6—15

Sukkot is an extraordinarily joyful festival, as the Torah urges us: “Be joyful on your festival . . . and you will experience only joy” (Deuteronomy 16:15). When the Holy Temple stood in Jerusalem, it hosted major public celebrations of sacred song and inspired dance during Sukkot.

What is the Talmudic debate about the symbolism of the sukkah?

Answer on p. 26.

OCTOBER 14

Sukkot lasts for seven days. The subsequent day is a stand-alone festival called Shemini Atzeret. Its name is self-explanatory: shemini means “eighth”— it is the eighth day from the start of Sukkot—and atzeret means (among other things) to “gather”— it is a day to gather in sacred celebration.

What’s a second reason why the word atzeret is employed for this holiday?

Answer on p. 30.

OCTOBER 15

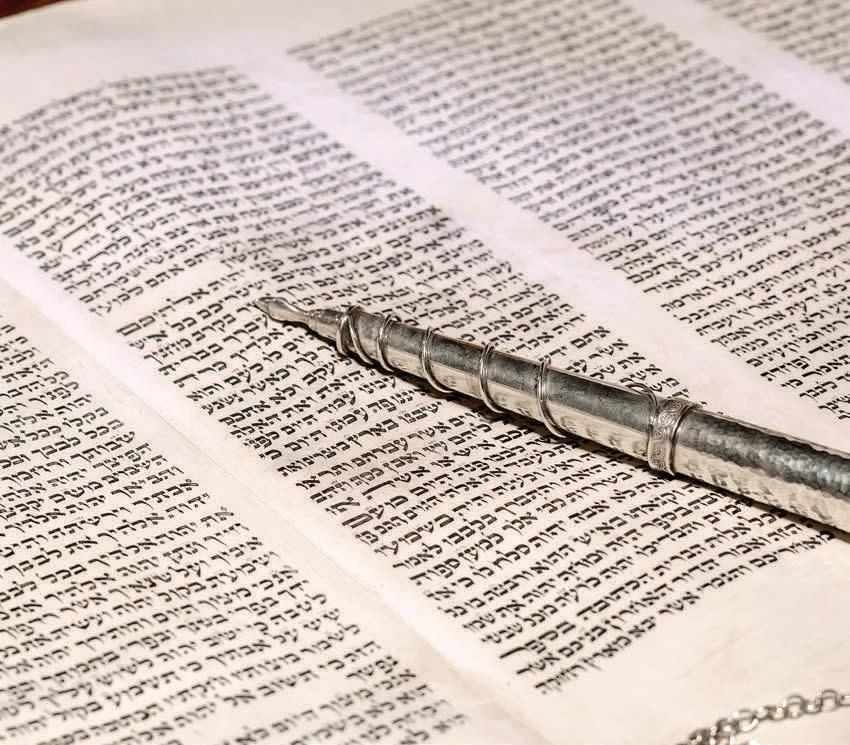

On each Shabbat, another portion of the Torah is read publicly from a Torah scroll in synagogues around the world. On Simchat Torah, the annual cycle is completed, which is cause for tremendous rejoicing—hence the name Simchat Torah, the joy of the Torah.

After we complete the Torah, we immediately begin from the beginning. Why?

Answer on p. 30.

Several times a year, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, would compose a pastoral letter addressed “to the sons and daughters of our People Israel, everywhere,” and copies were dispatched across the globe. The following are excerpts culled from several pre-Rosh Hashanah letters.

Rosh Hashanah teaches and reminds every individual about the tremendous powers which have been vested in him; powers which enable him not only to attain personal fulfillment in the fullest measure, but also to influence and direct—and transform, if need be—the whole world around him.

Together with this comes also the tremendous responsibility not to underestimate the powers with which he has been endowed, and to utilize them in the fullest measure for his benefit and for the benefit of the world around him.

The very fact that Rosh Hashanah, which is also the Day of Judgement of the entire world, has been set not on the day when everything was created yesh me’ayin (ex nihilo), but on the day when man was created, clearly indicates that the outcome of the judgement of the entire Creation depends on him, from which it follows that he has been given the capacity to influence and direct the whole of Creation. . . .

As explained in many places in our Torah, the manner of creation of the first man, Adam, and the details thereof, are duplicated in many respects in every Jew. . . .

Just as Adam had no one to shift to the G-d-given task of bringing the whole world to the realization of “Come, let us accept the kingship of Him Who created us,” so it is also with every individual regarding his responsibility; it is not transferable.

And when one comes to recognize this responsibility and privilege, all hindrances and difficulties encountered in the way become negligible. For, considering the far-reaching implication of every action of each individual, not only for himself, but for everyone else, reaching to the very end-purpose of Creation— surely all difficulties must be trivial by comparison.

WE CAN DO IT (1964)

The celebration of Rosh Hashanah has been ordained by the Creator to take place not on the anniversary of Creation in general, but specifically on the anniversary of the creation of Man. . . .

One of the main distinguishing features in the creation of Man is that Man was created single, unlike other species which were created in large populations.

This indicates emphatically that one single individual has the capacity to bring the whole of Creation to fulfillment, as was the case with the first Man, Adam. No sooner was Adam created on that first Rosh Hashanah than he called upon, and successfully rallied, all creatures in the world to recognize the Sovereignty of the Creator, with the call:

Come, let us prostrate ourselves, let us bow down and kneel before G-d our Maker! [Psalms 95:6]

For it is only through “prostration”—self-abnegation— that a created being can attach itself to, and be united with, the

Creator, and thus attain fulfillment of the highest order.

Our Sages, of blessed memory, teach us that the first Man, Adam, was the prototype and example for each and every individual to follow: “For this reason was Man created single, in order to teach you—one person equals a whole world,” our Sages declared in the Mishnah [Sanhedrin 4:5].

This means that every Jew, regardless of time and place and personal status, has the fullest capacity (hence also duty) to rise and attain the highest degree of fulfillment, and accomplish the same for the Creation as a whole.

Rosh Hashanah—the anniversary of the first, and single, human—reminds every Jew of this duty.

Rosh Hashanah disproves the contentions of those who do not fulfill their duty, with the excuse that it is impossible to change the world; or that their parents had not given them the necessary education and preparation; or that the world is so huge, and one is so puny— how can one hope to accomplish anything?

Rosh Hashanah offers the powers needed to fulfill this duty, because on this day the whole of Creation is rejuvenated; a new year begins, with renewed powers, as on the day of the first Rosh Hashanah.

This is borne out by the prayer which each one of us prays in the evening, morning, and afternoon prayers of Rosh Hashanah:

Establish Thy reign upon all the world . . . that every creature shall know that Thou didst create it.

The fact that each one of us prays for total Divine Sovereignty and the identity of each created thing with its Creator is proof that the attainment of this is within reach of every one of us.

ELEVATING OUR ENVIRONMENT (1977)

Man’s mission in life includes also “elevating” the environment in which he lives, in accordance with the Divine intent in the entire Creation and in all its particulars, by infusing holiness and G-dliness into all the aspects of the physical world within his reach—in the so-called “Four Kingdoms”: domem, tzome’ach, chai, and medabber (inorganic matter, vegetable, animal, and man).

Significantly, this finds expression in the special Mitzvos which are connected with the beginning of the year, by way of introduction to the entire year—in the festivals of the month of Tishrei:

The Mitzvah of the Succah, the Jew’s house of dwelling during the seven days of Succos, where the walls of the Succah represent the “inorganic kingdom”;

The Mitzvah of the “Four Kinds”—Esrog, Lulav, myrtle, and willow—which come from the vegetable kingdom;

The Mitzvah of Shofar on Rosh Hashanah, the Shofar being a horn of an animal.

And all of these things (by virtue of being Divine commandments, Mitzvos) are elevated through the medabber, the “speaking” (human) being—the person carrying out the said (and all other) Mitzvos, whereby he elevates also himself and mankind—both in the realm of doing as well as of not doing—the latter as represented in the Mitzvah of the Fast on the Holy Day, the Day of Atonement.

Thus, through infusing holiness into all four kingdoms of the physical world and making them into “vessels” (and instruments) of G-dliness in carrying out G-d’s command—a Jew elevates them to their true perfection. . . .

Taking into account the assurance that G-d does not require of a human being anything beyond his capacity, it is certain that, notwithstanding the fact that only a few days remain until the conclusion of the year, everyone, man or woman, can achieve utmost perfection in all aforesaid endeavors, according to the expression of our Sages of blessed memory—“By one ‘turn,’ in one instant,” since the person so resolved receives aid from G-d, the absolute Ein-Sof (Infinite), for Whom there are no limitations.

We offer many special prayers on Rosh Hashanah to project two general themes: (a) our acceptance of G-d as sovereign, and (b) our request that G-d inscribe us for a good year. These themes blend in a unified synthesis: G-d desires to be intimately present and felt in our physical experience. Our souls sense G-d’s desire, and we are moved to beseech G-d for material blessing to enable its fulfillment—turning this world into G-d’s home. We might not be conscious of this inner significance to our drive for material success, but if we train ourselves to listen well, we may begin to hear echoes of the soul’s footprints in our personal requests.

Tashlich, or “casting,” is a popular custom for the first day of Rosh Hashanah: we stroll to a nearby brook, pond, well, ocean, or similar body of water to recite a short prayer. This custom invokes the prophet Micah’s depiction of G-d removing our sins—“You will cast all their sins into the depths of the sea!” We quote this verse and others beside the body of water. See further, p. 16.

Even though napping on Shabbat is a proper way to celebrate the day of rest, the Code of Jewish Law states that on Rosh Hashanah we make a point of not napping. It is important to use the time constructively, such as by reciting Psalms, performing mitzvot, studying Torah, or sharing Judaism’s insights.

Each Jewish holiday has its special mitzvah deserving of special attention. Rosh Hashanah’s primary mitzvah is to hear the sound of the shofar, which prompts us to reflect on the awesome themes of this day (as explained on pp. 12–13). As you prepare to celebrate Rosh Hashanah this year, be sure to plan to hear the shofar in person on Tuesday, September 23, and then again on Wednesday, September 24. If you cannot attend a synagogue to hear the shofar during prayers, be sure to hear the shofar at some other point during the day.

Initial word panel for a prayer recited on Rosh Hashanah, in Machsor Lipsiae, created circa 1310 (MS. V. 1102, Leipzig University Library, Germany)

The meal served on the first night of Rosh Hashanah features a rich tradition of foods imbued with symbolic meaning. Here are some famous examples.

ROUND CHALLAH

For a year in which blessings continue without end.

That our merits be read and noticed. (The Hebrew word for squash is kara, which also means “to be read aloud.”)

That our foes be removed. (Beets in Aramaic is silka, which also means “to remove.”)

To multiply. (Carrots, in Yiddish, is merin, which also means “to multiply.”)

APPLE DIPPED IN HONEY

For a sweet new year.

Before we eat the apple dipped in honey, we recite a blessing and short prayer:

Baruch atah Ado-nai, Elo-heinu melech ha’olam, borei peri ha’etz. Yehi ratzon milfanecha, she-tichadesh aleinu shanah tovah umetukah.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the Universe, Who creates the fruit of the tree.

May it be Your will to renew for us a good and sweet year.

3 packets active dry yeast

2½ cups lukewarm water

1 cup sugar

4 eggs

½ cup oil

8–9 cups flour

1½ tbsp. salt

EGG WASH

1 egg yolk

1 tbsp. water

1 tsp. vanilla sugar

STREUSEL TOPPING

6–7 tbsp. margarine or oil

1 cup flour

1 cup sugar

Place the sugar, yeast, and warm water in the bowl of an electric mixer or any large bowl if mixing by hand. Let the yeast proof for 15–20 minutes.

Add oil, eggs, and flour. Add the salt as a dough begins to form, and knead it on medium speed for seven to eight minutes.

Place about one teaspoon of oil in the center of a large bowl. Transfer the dough into the bowl and flip it to coat completely with the oil. Cover the dough and let it rise for one hour.

Divide dough into 4 equal parts and roll into long ropes. Beginning at the end, spiral the rope on itself creating a round loaf. Pinch the end in on the bottom to make sure the spiral doesn’t come loose.

Combine the ingredients for egg wash and brush it on the dough. Let the dough rise for another 45 minutes to one hour. Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 375°F. Mix together the streusel ingredients with your fingers until a crumbly consistency forms. Sprinkle on top of the challah. Bake for 30 minutes or until golden on top and bottom.

The Torah teaches that when preparing a large batch of dough for baking, we are to set aside a portion of it for a Kohen—one of the priestly descendants of Aaron. Today, the custom is to burn this portion of the dough before baking the rest of the soon-to-be baked goods. To learn more about this special mitzvah, visit: www.chabad.org/363323.

By Chanie Apfelbaum

Reprinted with permission from www.busyinbrooklyn.com

4 eggs

2 cups sugar

1 cup canola oil

2 cups honey

2 cups self-rising flour

2 cups regular flour

2 Tbsp. cocoa

1 tsp. cinnamon

1 tsp. baking soda

2 cups boiling water

Preheat oven to 350°F. Beat eggs and sugar until creamy. Add oil and honey and beat until incorporated. In a separate bowl, mix flours, cocoa, cinnamon, and baking soda. Add wet ingredients and mix well. Pour boiling water into the batter and mix by hand. Pour into greased round pans and bake for about 50 minutes or until toothpick inserted comes out clean.

Tip: If you don’t have self-rising flour, add 2 tsp. salt + 3 tsp. baking powder to a measuring cup, and add flour until you measure 2 cups.

“The primary mitzvah of Rosh Hashanah is the shofar.”

Mishnah, Rosh Hashanah 3:3

The central Rosh Hashanah observance is hearing the shofar blasts on both days of the holiday, September 23–24. There are many laws governing the proper way to observe this mitzvah , which is why we make every effort to hear the shofar from someone who is well versed in these laws and who sounds the shofar properly.

Every feature of the shofar and its blasts is rich with symbolism and meaning.

Although the sounding of the shofar on Rosh Hashanah is a Divine decree, it also serves as an important wakeup call. The shofar’s voice calls to us, “Wake up, sleepy folk, from your slumber! Inspect your deeds, repent, and remember your Creator! Wake up those of you who forgot the truth and devoted your energies to vanity and emptiness that yield no benefit! Consider your souls! Improve your ways and your deeds! Abandon your evil path and thoughts!”

SOURCE

Why do we use a ram’s horn for the mitzvah of sounding the shofar?

G-d directed us: “Sound before Me a shofar fashioned from a ram’s horn so that I will recall in your merit the binding of Isaac, son of Abraham, who was willing to be sacrificed for Me, until I instructed Abraham to offer a ram in Isaac’s stead! When you do so, I will consider it as if you had bound yourselves before Me, like Isaac.”

Talmud, Rosh Hashanah 16a

The shofar used on Rosh Hashanah should be curved. This shape intimates to us that the further we bend our mind before G-d’s will and bend ourselves in submission to G-d in prayer on this day, the better.

Talmud, Rosh Hashanah 26b

Maimonides (1135–1204), Mishneh Torah, Laws of Repentance 3:4

Rosh Hashanah marks the beginning of Creation—the day on which G-d became King over the world that He created.

At a mortal monarch’s coronation, their subjects sound trumpets and horns to proclaim the beginning of their reign. We do the same for G-d on this day.

Rabbi Saadia Ga’on (882–942), Cited in Abudraham, Seder Tefilot Rosh Hashanah

Over the course of the entire day of the binding of Isaac, Abraham observed a ram whose horns were repeatedly becoming entangled in thickets and then disentangled.

G-d said, “Abraham! This ram is a metaphor for your descendants. Just as this ram moved from entanglement to entanglement, so will your children become repeatedly entangled in their transgressions and therefore entangled in exile at the hands of successive empires.”

Abraham asked G-d, “Master of the Universe! Will this be my descendants’ fate forever?” “No,” G-d responded. “They are destined to be redeemed in the era of the Messiah, who will be heralded by the sound of the shofar.”

Indeed the prophet stated, regarding that era, “G-d will appear upon them. His arrow will shoot like lightning, and G-d will sound the shofar” (Zechariah 9:14).

Jerusalem Talmud, Rosh Hashanah 2:4

A king was out in a forest and lost his way. He asked many people for directions, but none would help him, as they failed to identify who he was. Suddenly, a wise man recognized the king and helped him find his way. Thanks to his assistance, the king successfully returned to his palace.

Time passed, and the wise man did the king wrong and the king put him on trial. Before the sentencing, the wise man asked the king for a favor: “Allow me to wear the same clothing I wore on the day I saved you, and you will wear the clothing you wore on that day.” When the king put on those clothes, he remembered the great kindness the wise man had shown him, had mercy on the man, and forgave his offense.

The Jewish people did G-d a similar favor at the Giving of the Torah. G-d offered His Torah to all the nations of the world, but they did not want it. Only the Jewish people chose to accept the Torah. Therefore, when we are judged, we blow the shofar and invoke the shofar blasts at Mount Sinai. Thereby, we arouse G-d’s mercy for us.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev (1740–1810), Kedushat Levi, Derush LeRosh Hashanah

In advance of Rosh Hashanah one year, the Baal Shem Tov informed a senior disciple, Rabbi Zev Kitzes, that he would blow the shofar at the prayer services. In preparation, he was to master the mystical meanings behind the order of the shofar blowing.

Rabbi Zev complied and also prepared a sheet of paper with his notes on those profound concepts so that he could refer to them when he blew the shofar.

The Baal Shem Tov was displeased with this arrangement, and Rabbi Zev’s notes subsequently slipped out of his pocket and were lost.

When the awesome moment arrived, Rabbi Zev searched his pockets and discovered his loss. He could not recall the kabbalistic ideas without his notes, and he was horrified to have miscarried his weighty responsibility.

He sounded the shofar with a shattered heart, his bitter tears falling with the rising notes. He blew the shofar like an ordinary Jew, without any mystical meditation.

After the service, the Baal Shem Tov turned to him and greeted him warmly.

“There are numerous halls and chambers in the king’s palace,” the Baal Shem Tov explained.

“Each door has a unique key. But there is one key that fits all the locks, a master key that opens all the doors. The mystical concepts are the keys to the doors of Heaven, each unlocking a particular Heavenly chamber. But there is one key that unlocks all doors—that opens up for us the innermost chambers of the Divine palace. That master key is a broken heart.”

Sipurei Chasidim, Mo’adim, story 15

“Our Father, our King!

We have no king but You!”

A severe drought once struck the Land of Israel. The leading sages decreed a day of fasting and prayer, whereupon Rabbi Eliezer [one of the greatest sages living in the Holy Land during the late first and early second centuries CE] led the community in twenty-four emergency prayers, but the skies remained clear. Rabbi Akiva then took to the podium and cried out, “Our Father, our King! We have no king but You! Our Father, our King! For Your own sake, have mercy on us!” Rain immediately fell.

Talmud, Taanit 25b

THE SUPERNAL BOOK

Avinu Malkenu is cherished as one of the most memorable and moving High Holiday prayers. It contains a succinct series of supplications, through which we appeal with our most vital collective wishes to “our Father, our King.”

Four of its verses focus on Rosh Hashanah’s function as the date on which G-d determines the details of our upcoming year.

As we enter a fresh year, which of these requests resonates most with you?

Our Father, our King!

Inscribe us in the book of good life.

Our Father, our King!

Inscribe us in the book of redemption and deliverance.

Our Father, our King!

Inscribe us in the book of livelihood and sustenance.

Our Father, our King!

Inscribe us in the book of merits.

“Our sages of blessed memory instituted that we recite three blessings in the Rosh Hashanah Musaf prayer, corresponding to the three pillars of the Jewish faith.”

Rabbi Yosef Albo (1380–1444), Sefer Ha’ikarim 1:4

BACKGROUND

The Amidah for Musaf features three unique blessings that convey three fundamental tenets of the Jewish faith. In each of these blessings, ten biblical verses on the relevant theme are quoted: three from the Pentateuch, three from Psalms, three from the Prophets, and one final verse from the Pentateuch.

G-d created the world at large, and each of us in particular, for a purpose.

Passage from the blessing:

THEME OF BLESSING 2

Zichronot · Remembrance

G-d is involved in each aspect of His world, thus knowing and remembering all that transpires. Our choices matter.

Passage from the blessing:

Let all that has been made know that You made it; Let all that has been created know that You created it.

For you are One Who remembers forever all forgotten things, and there’s no forgetting before the throne of Your glory.

THEME OF BLESSING 3

Shofarot · Shofar Blasts

G-d revealed Himself at Mount Sinai following a strong shofar blast and instructed for all time how we ought to live.

Passage from the blessing:

You revealed yourself in a cloud of Your glory to Your holy nation, to speak with them. . . . As it is written in Your Torah, “Then on the third day, in the morning, there was thunder and lightning, and a heavy cloud on the mountain, and an exceedingly loud sound of the shofar.”

Tashlich, or “casting,” is a popular Rosh Hashanah custom, whereby we walk to a brook, pond, well, or any other body of water, and recite a short prayer. (Contrary to what some believe, feeding the fish is not part of the Tashlich ritual.) This year, the custom is practiced on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, Tuesday, September 23

THE ORIGINS OF TASHLICH

When the prophet Micah fervidly described how G-d forgives iniquity, he said (Micah 7:18–19):

Who, G-d, is like You, Who pardons iniquity forgives the transgression the remnant of His heritage? He does not remain angry

But delights in loving-kindness. He will again have compassion on us, hide our iniquities, and cast all their sins into the depths of the sea!

To invoke the imagery of this final verse, we stand near a body of water to recite this passage, along with some additional prayers.

INVOKES CREATION

By standing where water meets dry land, we remind ourselves of the third day of Creation, when G-d separated the water from the dry land (Genesis 1:9). Invoking Creation prompts us to remember that we are created beings and, therefore, obliged to the task for which we were created.

Rabbi Moshe Isserlis (c. 1530–1572), Torat Ha’olah 3:56

the prerequisite life, represents G-d’s kindness. We recite a near water to represent our wish for of kindness.

Shneur Zalman Liadi, Siddur

Unlike other animals, most fish do not have eyelids, so they don’t close their eyes to sleep. Standing near a body of water with fish reminds us of the Almighty’s watchful eye that neither sleeps nor slumbers.

Rabbi Yeshayahu Horowitz (c. 1550–1630), Shenei Luchot Haberit, Tractate Rosh Hashanah

“On

this day, G‐d will atone for you, to purify you.”

Leviticus 16:30

Decorated initial word panel for Kol Nidrei, from a Machzor for the High Holidays according to the Western Ashkenazi rite, created in Germany, ca. 1310 (MS. V 1102, Leipzig University Library).

Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar, begins at sunset on Wednesday, October 1 , and ends at nightfall on Thursday, October 2 . On this Day of Atonement, we abstain from eating and drinking, bathing or anointing our bodies, wearing leather shoes, or engaging in marital relations. (The fast begins and ends at the times noted on the back cover.) Refraining from these everyday comforts emphasizes that we can be more than creatures of impulse and that we must endeavor to nourish our souls as we do our bodies.

The history of this solemn day takes us back to the generation that received the Torah at Mount Sinai. Not

long after this climactic event, some Jews engaged in an idolatrous practice, which our sages compared to a bride committing adultery at her wedding. Moses pleaded with G-d to forgive the people he had led out of Egypt. On the tenth day of Tishrei, the day that would become Yom Kippur, G-d forgave the Jewish people. Since then, Yom Kippur has served as the annual Day of Atonement.

Wednesday, October 1 , the day preceding Yom Kippur, is treated as a holiday. Several observances on this day help prepare us for the awaited Day of Atonement.

The Talmud (Berachot 8b) teaches that when we partake in a festive meal on the day preceding Yom Kippur and then fast on Yom Kippur itself, we are credited as though we had fasted for two days. Practically, the festive meal is important because it lends us the strength to endure the subsequent fast and its many hours of immersive prayer. In addition, by celebrating the ninth day of Tishrei, we demonstrate our eagerness for the renewal that Yom Kippur provides. In fact, Yom Kippur is a day most worthy of celebration, and in Judaism we usually celebrate with a festive meal. Because no festive meal can occur on Yom Kippur itself, we fulfill this missing aspect of the Yom Kippur celebration on the preceding day.

On this day, it is customary to request—from a parent, rabbi, or friend—a piece of honey cake (known in Yiddish as lekach) to symbolize our wish for a sweet year. We verbally request the slice of cake so that if it has been decreed that we will resort to requesting a handout during the year, we should preemptively fulfill the unsavory decree by verbally requesting a delectable slice—and not have to plead for further assistance during the entire coming year.

TZEDAKAH

It is important to donate extra charity on this day. Earnings are the product of planning, creativity, and investment—and with charity, all of these investment are spiritually elevated and synced to the Divine purpose of bringing Heaven down to Earth.

We kindle holiday lights in the moments prior to the commencement of Yom Kippur, just as we do for any Shabbat and festival. See the back of this booklet for local candle-lighting time.

In addition, before Yom Kippur begins, many kindle a special candle in honor of the Yizkor prayers that they will recite the next day.

Yom Kippur atones for transgressions between an individual and G-d. It does not atone for transgressions between one person and another—unless the offender has placated the victim. For that reason, Jewish law urges us, in the run-up to Yom Kippur, to request forgiveness from whomever we may have aggrieved. Only through the human interaction of the offender appeasing the victim and the victim granting forgiveness can the victim achieve full internal healing, while the wrongdoer achieves the profoundest internal change.

Before the fast begins we remove any leather footgear, which may not be worn on Yom Kippur. It is customary to wear a white garment on Yom Kippur to reveal our potential for achieving purity; it also reminds us of a shroud—inspiring the humility and self-accounting that arrives from reflecting on our mortality. It is also customary to avoid wearing anything made of gold, to avoid invoking the sin of the Golden Calf.

It is customary for parents to bless their children individually—young children and adult children alike— before the onset of Yom Kippur. Some have the custom to recite the blessing while their hands are placed over the head of the child. The common custom is to invoke the notable blessings mentioned in the Torah:

For a son (from Genesis 48:20)

“May G-d make you like Ephraim and Menashe!”

For a daughter (based on Genesis, ibid., and Ruth 4:11)

“May G-d make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah!”

It is also customary to recite, for both a son and daughter, the blessings recorded in the Torah in Numbers 6:22–27. Naturally, parents should add additional heartfelt wishes in their own words.

The central theme of Yom Kippur is teshuvah , commonly translated as “repentance,” but more accurately meaning “return.” Judaism teaches that teshuvah can be performed by any individual, for any act, at any time. However, Yom Kippur is particularly conducive for teshuvah because the sacredness of the day itself achieves atonement for those who tap into its potential by engaging in teshuvah

1 / RESOLUTION to not reoffend

2 / REMORSE for the offense

3 / RESTITUTION for financial damages

4 / APPEASEMENT of the victim

MAIMONIDES · 1138–1204

Teshuvah occurs when transgressors abandon their transgressions, remove them from their thoughts, and resolve in their hearts never to commit them again. This is the message of the verse— “Let the wicked forsake their ways, and the unrighteous their thoughts” (Isaiah 55:7). It is also important to regret the past, as the verse states, “After I returned, I regretted” (Jeremiah 31:18).

Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Laws of Teshuvah 2:2

RABBI YEHUDAH LOEW OF PRAGUE · C. 1512–1609

When one individual acts sinfully against another . . . the act has an impact on the victim, who is hurt by the crime. This is the rationale behind the golden rule of repentance: Whenever an offender’s behavior negatively impacts a human victim, the offender cannot achieve atonement without appeasing the victim and repairing the damage. Yom Kippur provides an opportunity for atonement only for matters that are between a human and G-d, whereas an injury inflicted upon one human by another cannot be rectified through atonement until the offender seeks forgiveness from the victim.

Derashot HaMaharal MiPrague Derush Al HaTorah (Tel Aviv: Yad Mordechai Institute, 1996), p. 47

5 / VERBAL CONFESSION

to G-d, supported with a verbal statement of remorse for the past and resolution for the future

SEFER HACHINUCH · THIRTEENTH CENTURY

We are commanded to verbally confess our transgressions to G-d. One of the reasons for this is that a verbal expression compels the offender to confront the reality that their actions are fully revealed to G-d, Who knows full well what they have done.

Furthermore, the act of stating the transgression and verbally expressing remorse will cause the offender to be more careful and avoid reoffending in the future.

Sefer Hachinuch, Mitzvah 364

Kol Nidrei is a legal formula rather than a prayer. Through it, we preemptively void vows we may utter during the coming year. (It is limited to personal vows not involving commitments to others.)

Judaism regards vows as implicitly directed to G-d, even if this is not explicitly stated. It therefore strongly discourages vow taking, for if the vow is not kept, the individual has sinned against G-d. In case we do end up taking a vow, the Kol Nidrei proclamation serves to void it. Kol Nidrei is therefore a preemptive measure to avoid sin.

Having demonstrated our eagerness to avoid future transgression, we are empowered to approach G-d and plead forgiveness for our past failings.

Each of Yom Kippur’s five services includes the traditional confession— an alphabetically crafted list of sins we may have transgressed. It is recited in the plural due to the Jewish nation’s mandate of mutual responsibility. With each item of confession, we gently tap our heart.

A most famous and poignant piece of Jewish liturgy, couched in dramatic prose. It paints the scene of the celestial courtroom in which our deeds are reviewed. Even the angels tremble before the spirit of Divine judgment. Everything is at stake: life and death, prosperity and suffering, comfort and struggle. We end with a redeeming antidote: repentance, prayer, and charity can avert a negative verdict.

The climax of the musaf service is a detailed description of the Yom Kippur rituals performed by the High Priest in G-d’s Temple. Reading his duties is a form of reenactment that elicits a similar measure of atonement. In ancient times, hearing the High Priest pronounce G-d’s name on Yom Kippur was a most awesome experience. As we read of this moment, we bow to G-d in reverence, similar to the response of our ancestors.

G-d sent the prophet Jonah from Israel to the Assyrian city of Nineveh to urge its inhabitants to repent. Jonah attempted to escape his mission through sailing in the wrong direction, but he was swallowed by a giant fish and kept alive miraculously.

Jonah and the whale, in the Kennicott Bible (folio 305r), a lavishly decorated Hebrew Bible, produced in La Coruña, Spain, in 1476 for Don Shlomo de Braga.

(Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, U.K.)

We recite a brief but poignant memorial prayer for the departed during Yom Kippur’s morning service. It is popularly referred to as Yizkor, a name taken from the prayer’s opening word, which means, “May (G-d) remember.” We beseech G-d to remember favorably the souls of our relatives who have risen to the world of truth, in the merit of the charity that we intend to donate in their honor (after the conclusion of Yom Kippur).

The Talmud (Sotah 10b) describes King David’s fervent prayer for the departed soul of his rebellious son Absalam, after the latter was killed in battle. It reveals that David’s prayer was successful in achieving a positive destiny for Absalam’s soul in the afterlife.

This material world is the arena for action and accomplishment, the effects of which are experienced in the afterlife. By contrast, once a person leaves this world, they lose the ability to continue influencing their situation in Heaven. At that point, only individuals who remain alive in this world can steer the course of the departed soul. They can pray and donate charity on behalf of the soul, bringing it much benefit. Indeed, the practice of offering such prayers and donations is extremely widespread among the Jewish people.

Rabbi Shlomo ibn Aderet (1235–1310), Responsa 5:49

Although commonly called Yom Kippur, the Torah describes this holiest day on the Jewish calendar as Yom Hakipurim, referring to “atonements” in the plural (Leviticus 23:27). With this, the Torah informs us that dual atonements are achieved on this day: for the living, and for the departed. It is therefore customary to explicitly mention in prayer on Yom Kippur the names of the departed souls of our close relatives.

Rabbi Yaakov Weil (15th century), Responsa 191

YIZKOR POINTERS

→ After completing the morning service (Shacharit), take a moment to meditate and emotionally connect with your loved ones who have passed on.

→ Pledge to donate to charity on behalf of your loved ones. Choose an amount and a cause.

→ Identify which passage(s) of Yizkor you will recite. (There are separate texts for a father and a mother—and depending on your prayer book, perhaps for others). Then recite the applicable text(s).

→ Take a moment to contemplate your connection with your loved one(s) and to picture the immense gratification they are experiencing at this moment— for you are lovingly remembering them and pledging to donate charity in their merit. Bask in the fresh strength you have injected into your relationship.

→ After Yom Kippur, remember to make good on your pledge. There is a soul waiting for its effect.

Chasidic teachings about the High Holidays emphasize the power of sincerity over sophisticated understanding, and the need to infuse these solemn days with an uplifting feeling of heartfelt joy. The following Chasidic stories illustrate these themes.

Rebbetzin Rivkah Schneersohn of Lubavitch (1834–1914) related:

It was once common in Eastern Europe for lone Jewish families to live in small outlying non-Jewish villages, in isolation from Jewish communities. For the High Holidays, these individual families would travel to the nearest town with a congregation to participate in the services.

In one such village, a villager completed his morning prayers on the day before Yom Kippur and began readying his family for the journey to the nearest community. His sons dragged their feet and he grew impatient.

He finally told them that he would start walking. When they were ready, they would set out with their wagon, and when they passed him on the way they would take him aboard the wagon.

The villager walked and walked until he was too exhausted to continue. He lay down under a tree on the side of the road to rest, expecting his sons to pick him up when they passed. He soon fell into a deep sleep.

Meanwhile, his family was running late and when they eventually set out in a disorganized rush, they did not notice their father’s figure lying in the shade and hastily passed him by.

Hours later, the villager awoke and realized that his family had forgotten about him. Looking at the setting sun, he realized that there was insufficient time for them to return for him, nor could he reach the town on foot before the start of the sacred day.

He wouldn’t even manage to return home to his village before nightfall; he was stranded for the duration of Yom Kippur!

As the sun set and the time for the Kol Nidrei service came, the forgotten villager raised his eyes to Heaven.

“Master of the universe!” he thundered. “My children have forgotten about me, but I forgive them! Now, Master of the universe, forgive Your children who have forgotten about You!”

Shmuot Vesipurim, vol. 1, pp. 80–81

It was the eve of Rosh Hashanah when Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760) arrived in a certain town and asked the townsfolk, “Who leads you in prayer during the High Holiday services?”

“Why, our local rabbi!” they responded.

“How does he conduct himself during those prayers?” the saintly man pressed.

They described the rabbi’s prayers, including his habit of chanting the Yom Kippur confessions to joyful melodies.

The Baal Shem Tov asked to meet the rabbi and demanded an explanation. The rabbi replied:

“Imagine that a king has a lowly servant whose mission is to rake and clean the courtyard, removing the dirt that collected there. He must ensure that the place is spotless, so that the king should delight in it.

“As he busily tidies up, the servant is overjoyed with the opportunity to clean his beloved king’s courtyard. He sings cheerful tunes as he labors, for he knows that he is causing the king great pleasure.”

The Baal Shem Tov exclaimed, “If that is your intention while reciting the confessions, then I could only wish to reach your level!”

Sipurei Chasidim, Moadim, story 92

Jewish mysticism reveals that the Divine soul within us is multilayered, each rung equipped with another variation of a relationship with G-d:

Name Relationship with G-d through

Nefesh Action

Ru’ach Emotion

Neshamah Intellect

Chayah Will

Yechidah Oneness

The kabbalists explain that the first three soul layers are fully available on the average day. By contrast, the deeper soul layers (Chayah and Yechidah) transcend our conscious psyche and are excluded from our regular experience.

There is a further distinction between the first four layers and Yechidah: Even when we dedicate ourselves to G-d using the four layers—deploying our action, emotion, intellect, and will—we remain distinct from G-d. That is due to these four layers recognizing themselves as independent spiritual entities. Not so the fifth level. Our Yechidah, our deepest core, recognizes that it is a part of G-d. Its profound longing for G-d is similar to self-love, although it never focuses on itself but is locked in a perpetual bond with G-d.

For the majority of our daily living, our conscious minds experience a degree of separation from G-d, even while we engage our powers of action, emotion, intellect, and desire to relate to G-d. On Yom Kippur and, more specifically, during the final moments of this sacred day, a fundamental shift occurs. In these climactic moments, our Yechidah shines through and we can become conscious of our inherent unity with G-d.

In the closing hour of Yom Kippur, we pray the Ne’ilah (“closing”) service. We seek to complete our Yom Kippur journey by expressing in prayer the profound oneness with G-d that is available to us overtly at this special time.

POTENT STATEMENTS OF FAITH

At the finale of Ne’ilah itself, we declare with all our power three most potent statements of our eternal faith:

Hear O Israel, the L-rd is our G-d, the L-rd is One.

Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom forever and ever.

The L-rd is our G-d.

JOY AND HOPE

The Chabad custom is to conclude the Yom Kippur service with boundless joy and exuberant song, demonstrating our confidence that our teshuvah has been accepted and that we will indeed be inscribed for a year filled with physical and spiritual goodness.

In the synagogue, the shofar is sounded after the recitation of the above verses, and we then proclaim loudly in unison:

Next year in Jerusalem!

“Celebrate

the festival of Sukkot for seven days. . . . Be joyful in your festival.

Deuteronomy 16:13–15

. . . And you will have only joy.”

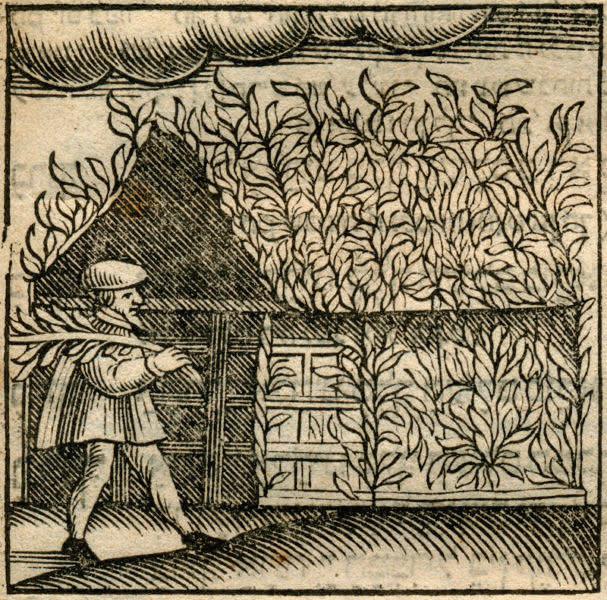

Copper engraving of a Jewish family eating a festive meal in a lavishly decorated sukkah, featured in the first volume of Bernard Picard’s Cérémonies et Coutumes Religieuses de Tous les Peuples du Monde (Amsterdam, 1723). Picard worked hard to learn about the customs of the Sefardic Jewish community residing in Amsterdam. The resulting engravings are now considered among the best sources for early eighteenth-century Dutch Jewish life.

The joyous festival of Sukkot will begin in the evening of Monday, October 6 , and it extends until the evening of Monday, October 13 . The first two days are the festival’s primary days: we kindle festival lights in the evening (for precise timing, see the back of this booklet), enjoy festive meals preceded by Kiddush, refrain from work and restricted activities, and recite special festival prayers. The remaining days are known as chol hamo’ed , “the weekdays of the festival.” Throughout the seven days of Sukkot, we eat our meals in the sukkah, a hut of temporary construction with a roof comprised of detached branches, and (except on Shabbat) we recite a special blessing while holding four specific plant species.

We place a major emphasis on joy during this holiday. Our joy is derived from reflecting on the many blessings in our lives, both physical and spiritual—and realizing that these gifts demonstrate that G-d is caring for us, loving us, and providing us with our needs.

The Torah refers to Sukkot as the “Festival of the Ingathering,” for in the Land of Israel this holiday coincides with the farmers bringing their harvested crop into their homes and storehouses. It is precisely at this juncture, when farmers witness the success of their toil, that they are most vulnerable to overlooking their dependence on G-d. Through from the comfort of their they have just delivered an abundance of grain—they are prompted to recall that their success was inevitable, for G-d is the source of all of their blessings. They are reminded to bear this truth in mind even as they feel secure and satisfied with their labors.

Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir (Rashbam) (c. 1080–1160), Leviticus 23:43

For seven days you shall live in temporary shelters. Every resident among the Israelites shall live in such shelters. This will remind each generation that I had the Children of Israel live in temporary shelters when I took them out of the land of Egypt. I am the L-rd your G-d.

Leviticus 23:42–43

“I had the Children of Israel live in temporary shelters”: Rabbi Eliezer taught that this refers to the miraculous clouds of glory that sheltered the Jews as they dwelt in the wilderness. Rabbi Akiva explained it literally: the Jews made actual shelters for themselves during that period. Talmud, Sukkah 11b

The mitzvah of sukkah is unique in the sense that it encompasses our entire lives. According to Jewish law, throughout the festival we are supposed to eat in the sukkah, sleep in the sukkah, and to spend the maximum possible time there. In short, we bring our entire lives into the mitzvah of sukkah. This imparts a critical message about our faith: Judaism is not just a minor facet of our lives. Judaism is designed to sanctify and guide the entirety of our lives, including superficially meaningless and mundane activities. Even such endeavors can be infused with sanctity.

The Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994), Torat Menachem 4, p. 32

The first view understands the function of Sukkot as a means of commemorating G-d’s special protection and care for our ancestors during their journey through the wilderness. We replicate their experience by dwelling in our own sukkot for the sake of reliving the loving care that G-d displayed to our ancestors— and that He continues to extend to us today.

The second view understands the function of Sukkot as a means of experiencing the contrast between our ordinary, relatively prosperous living conditions and the primitive desert dwellings of our ancestors. We are thereby inspired to express gratitude for the positive blessings in our lives, which leads to a sense of joy and indebtedness to G-d. It is an exercise in escaping the all-toohuman vice of taking our blessings for granted.

Rabbi Yitzchak Abarbanel (1437–1509), Leviticus 23

“For seven days, the sukkah becomes one’s permanent residence while the house becomes one’s temporary residence. So if you have beautiful vessels and fancy bedding, take them to the sukkah. And be sure to eat, drink, relax, and study Torah in the sukkah.”

Talmud, Sukkah 28b

Willem Surenhuis (ca. 1664–1729) was a Dutch Christian scholar who translated the Mishnah into Latin in Amsterdam between 1698 and 1703. The Mishnah in Tractate Sukkah discusses numerous ways one might build a sukkah and whether each is acceptable for the mitzvah. Each of these cases is depicted on this page.

A sukkah must have at least three walls. Any material is satisfactory for the walls, provided the results are sturdy enough to withstand an ordinary gust of wind without swaying.

A sukkah must be positioned directly under the sky. It cannot be situated under a tree or overhang.

The sukkah’s most important feature is its natural roof, referred to as sechach—“covering” in Hebrew. Only nonedible plant matter that is detached from the ground and remains in its raw state (not having been developed into any tool, processed item, or the like) may be used to create the roof. Common examples include bamboo poles, evergreen branches, and palm fronds. Enough foliage must be present to ensure that the shade is greater than the sunlight that reaches inside the sukkah through its roof.

BLESSING

During the Sukkot festival, when we are inside the sukkah and about to eat a meal (defined as eating a species of grain or drinking wine), we recite (a) the blessing specific to the kind of food or beverage, and then (b) the following sukkah blessing:

Baruch atah Ado-nai, Elo-heinu melech ha’olam, asher kidshanu bemitzvotav, vetzivanu leishev basukkah.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us to dwell in the sukkah.

You shall take for yourselves, on the first day [of Sukkot], the fruit of the citron tree, an unopened palm frond, myrtle branches, and willows of the brook; you shall rejoice before G‐d for seven days.

Leviticus 23:40

An etrog (yellow citron) represents one type of Jew: just as the etrog has a taste and aroma, so does Israel include those who have both Torah learning and good deeds.

A lulav (unopened palm frond), taken from the date palm, represents a second type of Jew: the date has a taste but no aroma; so does Israel include those who have Torah but do not have good deeds.

A hadas (myrtle) represents a third type of Jew: the hadas has an aroma but no taste; so does Israel include those who have good deeds but no Torah.

An aravah (willow) represents a fourth type of Jew: just as an aravah has no taste and no aroma, so does Israel include those who do not have Torah or good deeds.

Says G-d, “Let them all bond together in a single bundle and atone for each other. And when you do so, I will be elevated, for G-d is elevated when the people of Israel come together as one.”

Midrash, Vayikra Rabah 30:12

GRATITUDE FOR VEGETATION

The four species are a symbolic expression of our rejoicing over our ancestors leaving the wilderness, an uninhabitable place, and entering a country filled with fruit trees and rivers. To remember this, we take the etrog, a most pleasant-looking fruit; the hadas, a most fragrant plant; the lulav, which has the most beautiful leaves; and the aravah, one of the best plants.

These four kinds also have the following three qualities: They are found aplenty in the Land of Israel so that everyone can obtain them. They look pleasant, and the etrog and hadas have a pleasant aroma, while the other two have neither a good nor bad smell. Thirdly, they keep fresh and green for seven days, which is not the case with many other fruits.

Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed 3:43

We take the four species in our hand on each day of Sukkot (except for Shabbat). The four kinds are:

a Etrog—citron

b Lulav—an unopened palm frond

c Hadas—myrtle (a minimum of three is required)

d Aravah—willow (two)

It is customary to tie the latter three together at the lower stem end before the holiday, and the etrog remains separate.

Detail from the Rothschild Miscellany, a strikingly elegant Hebrew manuscript comprised of thirty-seven distinct texts accompanied by masterful artwork, crafted in northern Italy between 1460–1480. On the left, a man adorned in his talit waves the “four kinds.” To the right, a decorated initial-word panel introduces a prayer to be recited while holding the lulav. It presents two equestrian youths jousting with lances (a common medieval sports contest). This invokes a teaching in the Midrash (Vayikra Rabah 30:2) that compares the Jew’s taking of the lulav on Sukkot to the victor’s displaying his lance after victory.

On each day of the holiday (except Shabbat), preferably in the morning, we perform the mitzvah as follows:

BLESSING 1

1 Hold the lulav (with the hadasim and aravot attached to it) in your dominant hand. The etrog should be within reach on the table.

2 Recite the blessing on the lulav

3 Lift the etrog with your other hand.

4 If this is the first time this year that you are performing this mitzvah, recite a second blessing (Shehecheyanu). On the remaining days of Sukkot, skip this step.

5 Bring the etrog and lulav together and ensure that they touch while each remains in its respective hand. This accomplishes the mitzvah

6 It is customary to add movement to the ritual. Gently move the species together three times to and fro in the following manner: to the right, to the left, in front of you, in an upward motion, in a downward motion, and behind you (by turning somewhat to the right).

Baruch atah Ado-nai, Elo-heinu melech ha’olam, asher kidshanu bemitzvotav, vetzivanu al netilat lulav.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G - d, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded regarding taking the lulav

BLESSING 2

Baruch atah Ado-nai, Elo-heinu melech ha’olam, shehecheyanu, veki’yemanu, vehigi’anu lizman hazeh.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G - d, King of the Universe, Who has granted us life, sustained us, and enabled us to reach this occasion.

The festival of Sukkot leads directly into another two-day festival: Shemini Atzeret, which begins the evening of Monday, October 13 , and Simchat Torah that begins the next evening. The most familiar feature of this festival is the universal custom to complete the yearly Torah cycle on the day of Simchat Torah, which infuses the two-day holiday with incredible joy.

THE THEME OF SHEMINI ATZERET

“The eighth day shall be a time of restraint [atzeret]” (Numbers 29:35). This means, “Restrain yourselves from leaving.” With this command, G-d implores the Jewish people, “Although you have been with Me throughout the seven-day Sukkot festival, please remain with Me a little longer.” It expresses G-d’s affection for Israel. It is comparable to children about to take leave of their father, who tells them, “It is difficult for me to part with you! Please stay just one more day!”

Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (Rashi) (1040–1105), Numbers 29:35–36

RESTARTING THE TORAH

It is appropriate to rejoice when we complete the Torah. It is also customary to begin the cycle again immediately, reading from the very beginning of the Torah right after completing it. This prevents anyone from alleging that we consider ourselves having finished with the Torah and that we do not want to study it anymore. . . . We partake of joyous festive meals on this day in honor of completing the Torah, and to express our delight at having begun it anew.

Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher (1269–1343), Arba’ah Turim, Orach Chayim 669

One year, around the time of the High Holidays, the daughter of the saintly Rabbi Meir of Premishlan (c. 1780–1850) fell severely ill.

When Simchat Torah arrived Rabbi Meir conducted the hakafot as usual, dancing and singing with abandon. But suddenly he was interrupted by several of his students who burst into the synagogue. They informed him that his daughter’s condition had deteriorated and she appeared to be drawing her last breaths.

Rabbi Meir rushed home to his daughter’s bedside and discovered that the report was accurate. He stepped out of her room and stood alone. Then he began to address G-d directly, referring to himself with the diminutive nickname “Meir’l,” as he often did.

“Master of the universe!” he proclaimed. “You commanded us to blow the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, so Meir’l blew the shofar. You commanded us to fast on Yom Kippur, so Meir’l fasted. You commanded us to sit in a sukkah during Sukkot, so Meir’l sat in a sukkah. You commanded us to rejoice on Simchat Torah, so Meir’l is joyful.

“But now, Master of the Universe, you have made Meir’l’s daughter ill. Meir’l must accept it with love, for the sages of the Mishnah teach us that ‘we are obligated to bless G-d for misfortune just as we bless Him for good fortune,’ and the Talmud explains that this means that we are to accept tragedy with joy.

“However, Master of the universe, there is also an explicit law that ‘we must not mingle one joy with another joy!’ . . .”

At that moment his daughter broke into a heavy sweat, and within a short time she recovered completely.

Likutei Reshimot Umaasiyot, story 75

Shemini Atzeret this year is the second yahrtzeit of the victims of the Oct. 7 massacres. Jewish tradition reveals that the souls of people murdered for being Jewish are propelled into the purest Heavens. As we celebrate the festival, souls in Heaven rejoice with us, and those martyred souls dance to ever happier heights. No horror has broken our people’s three-and-a-half-millennia dance that began at Sinai, because an eternal nation cannot die. We honor the victims by proudly celebrating our Judaism; we defeat darkness with our indestructible joy.

We welcome both evenings of this two-day holiday by lighting the distinctive candles or oil lights. See chabad.org/zmanim for local candle-lighting times.

THE SUKKAH

The Talmud (Sukkah 47a) guides us to eat in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret (without reciting a blessing on this mitzvah). However, there are divergent customs as to whether this applies to all or just some of the meals on Shemini Atzeret. Chabad custom calls for eating in the sukkah throughout this festive day.

YIZKOR

Yizkor, a special memorial prayer for the departed, is recited during the Shemini Atzeret morning service.

As we enter the rainy season, we insert into the musaf prayer of Shemini Atzeret special prayers that the coming rainfall engender blessing, life, and plenty.

We conclude the Torah reading cycle during the day of Simchat Torah. Before doing so, we engage in joyous dance and song while circling the synagogue’s Torahreading lectern. These are called hakafot—“encirclings.” (So immense is this joy that we begin it earlier, on the previous evening—dancing the hakafot following the evening services on the eve of Simchat Torah. In fact, some have the custom to dance the hakafot on the night before that as well—on the eve of Shemini Atzeret.)

CHAZAK!

Chazak—“Be strong!” This ancient Hebrew wish is exclaimed aloud in unison and with great joy by the entire congregation immediately after the Torah’s final verse is read. The significance: Congratulations on completing this great mitzvah! May G-d grant you the strength to complete many more mitzvot!

A CALL TO ACTION

It is customary in some synagogues to mark the conclusion of Simchat Torah with a cryptic announcement: VeYaakov halach ledarko (“Jacob went on his way”— Genesis 32:2). The implication is that our multi-festival season has now ended and we are empowered by the radiance and spirituality of the diversity of sacred occasions to leap into the year ahead with fully stocked reserves of faith, joy, insight, and determination.

Sukkot (Chol Hamo’ed) at 6:23

Hoshanah Rabah

*Light from a preexisting flame.

BLESSING 1

Baruch atah Ado-nai, Elo-heinu melech ha’olam, asher kidshanu bemitzvotav, vetzivanu lehadlik ner shel:

Rosh Hashanah Shabbat

Sept. 22–23 Yom Hazikaron. Sept. 26, Oct. 3, 10 Shabbat Kodesh.

Yom Kippur Sukkot Oct. 1 Yom Hakippurim. Oct. 6–7 Yom Tov.

Shemini Atzeret Simchat Torah Oct. 13 Yom Tov. Oct. 14 Yom Tov.

BLESSING 2

On all holiday evenings during Tishrei, add a second blessing:

Baruch atah Ad-onai, Elo-heinu melech ha’olam, shehecheyanu, veki’yemanu, vehigi’anu lizman hazeh.

BLESSING 1

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us to kindle the light of:

Rosh Hashanah Shabbat

Sept. 22–23 Yom Hazikaron.

Sept. 26, Oct. 3, 10 Shabbat Kodesh.

Yom Kippur Sukkot

Oct. 1 Yom Hakippurim.

Oct. 6–7 Yom Tov.

Shemini Atzeret Simchat Torah

Oct. 13 Yom Tov.

BLESSING 2

Oct. 14 Yom Tov.

On all holiday evenings during Tishrei, add a second blessing:

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the Universe, Who has granted us life, sustained us, and enabled us to reach this occasion.

BLESSING 1

Shabbat Rosh Hashanah

Sept. 26, Oct. 3, 10