CHABAD JEWISH LEARNING CENTRE

NISSAN 15–22, 5785 APRIL 12–20, 2025

Passover, the joyous Jewish festival of freedom, begins this year on Saturday evening, April 12, and continues through Sunday evening, April 20. It marks our ancestors’ liberation from Egyptian bondage and the birth of our nationhood and special relationship with G-d. The festival’s highlight is the seder (ritual meal), observed on Saturday evening, April 12, and repeated on the following night.

Jewish calendar dates do not begin at midnight, but earlier—at nightfall. Not insignificantly, this allows Jewish days to fully progress from darkness (night) to light (day), a theme especially native to Passover eve: Our national experience began with darkness of exile and the nightmare of bondage, before maturing into freedom and light (the receiving of the Torah). In our own lives, we attempt to replicate this progress when celebrating Passover—to escape from internal darkness, inflicted by self-centeredness and servitude to baser instincts, and to emerge into a liberating existence focused on purpose. In this way, Passover empowers our personal exodus.

The following pages provide impetus for this experience. Fascinating Passover insights, designed to inform and inspire, are paired with practical guidance to facilitate a meaningful commemoration of our past, while supplying liberating tools for the present.

Our goal is to produce results that endure: Although some editions of the Haggadah include a concluding declaration—“We have reached the end of the Passover seder”—other editions pointedly shun that notion. For all concur that our inspiring experience is supposed to linger and positively influence us for the rest of the year, until we are ready to leap further on the following Passover. The messages contained in this pamphlet encourage us to head into Passover prepared to never leave, for the personal liberation we will experience is as valuable and immutable as the miraculous disintegration of Egyptian bondage and the gift of divinely guided nationhood that flourishes until today.

Best wishes for a festival of liberating inspiration, Rabbi Altein

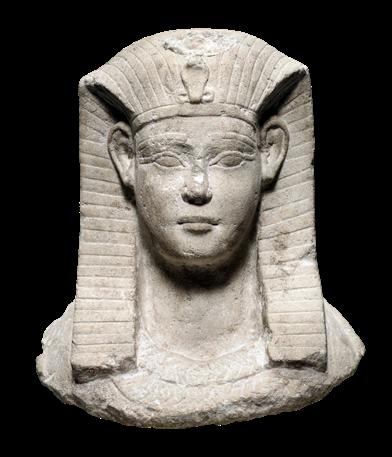

G-d strikes a covenant with Abraham known as the “Covenant between the Parts.” G-d informs Abraham that his children will be enslaved in Egypt and then return to Israel to inherit the land.

On Rosh Hashanah, Pharaoh has 2 disturbing dreams and Joseph, known to interpret dreams, is brought before Pharaoh. Joseph’s interpretation foretells of 7 years of plenty followed by 7 years of famine. He advises a nationwide food storage program. Pharaoh is impressed and appoints Joseph as viceroy of Egypt.

After 2 years of famine, Jacob and his family come to Egypt, where Joseph provides for them and where they are treated with honor as Joseph’s family.

1400

The conditions of Jewish slavery grow exceedingly harsh and bitter.

1545

Abraham’s grandson, Jacob, has 12 sons, including Joseph. The brothers sell Joseph into slavery and he is taken to Egypt. Thus begins the saga of Jewish slavery in Egypt.

Levi, Jacob’s last surviving son, passes away. With the last of Joseph’s brothers gone, Pharaoh grapples with how to handle the growing Jewish population in Egypt and decides to enslave them.

1373 BCE

Moses kills an Egyptian for beating a Jewish slave. This is reported to Pharaoh, who decrees Moses’s execution. Moses flees to Midyan.

On the 7th of Adar, Moses is born. His mother, Jochebed, places him in a basket in the Nile. Pharaoh’s daughter discovers him and raises him in Pharaoh’s palace.

1394

Pharaoh decrees that all Jewish male newborns be drowned in the Nile.

Exactly 1 year before the Exodus, G-d appears to Moses in a burning bush and orders him to return to Egypt and liberate the Jews. Moses appears before Pharaoh and relays G-d’s instruction, but Pharaoh refuses.

1314 BCE

9.5 months before the Exodus, the Ten Plagues commence.

On Rosh Hashanah, as the 3rd plague commences, Egypt loses control of its Jewish slaves, who are henceforth free of oppression.

1313 BCE

On the 1st of Nisan, G-d instructs the Jews to designate a Paschal lamb to be eaten on the eve of their Exodus.

On the 10th of Nisan, the Egyptian firstborns demand that the Jews be liberated. When Pharaoh refuses, a civil war ensues.

1313 BCE

On the 14th of Nisan, Jews slaughter the Paschal lamb and paint their doorposts with its blood.

On the eve of the 15th of Nisan, Jews eat the Paschal lamb and celebrate the first Passover seder in history. At the stroke of midnight, the 10th plague strikes all Egyptian firstborns, but passes over the Jewish homes. Jews spend the night collecting valuables from their Egyptian neighbors and baking matzah for their journey. At midday, the Jews leave Egypt.

1313 BCE

On the 21st of Nisan, Pharaoh and his army reach the Jews at the Sea of Reeds. G-d splits the sea miraculously, the Jews pass through, and the pursuing Egyptians drown.

1313 BCE

1 month after the Exodus, the matzah provisions run out and G-d commences a miraculous daily ration of heavenly manna that continues for 40 years.

1313 BCE

On the 6th of Sivan, seven weeks after the Exodus, the Jews receive the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai.

SOURCES

Mechilta , Shemot 12:40, 12:41; Yalkut Shimoni , Shemot 1; Tanchuma Shemot 8, Shemot 2:11–15; Rashi, Shemot 6:16; Rabbeinu Bechaye, Shemot 10:5; Talmud, Rosh Hashanah 11a, Sotah 12a, Kidushin 38a, and Shabbat 86b.

One of the instructive messages of the Yom Tov of Pesach is that a Jew has the inner capacity and actual ability to transform himself, in a short time, from one extreme to the opposite. Our Holy Scriptures and Rabbinic sources describe in detail the bitterness of the enslavement in Egypt and the nadir of spiritual depravity to which the enslaved Jews had sunken in those days.

Enslaved in a country from which even a single slave could not escape; completely in the power of a Pharaoh who bathed in the blood of Jewish children; in utmost destitution; broken in body and spirit by the meanest kind of forced labor—suddenly Pharaoh’s power is broken; the entire people is liberated; the erstwhile slaves emerge from bondage as free men, bold and dignified “with an outstretched arm” and “with great wealth.”

Likewise is their spiritual liberation in a manner that bespeaks a complete transformation. After having sunk to the 49th degree of unholiness, to the point of pagan idolatry—they suddenly behold G‑d revealed in His full Glory, and only a few weeks later they all stand at the foot of Mount Sinai on the highest level of holiness and prophecy, and G‑d speaks to each one of them individually, without any intermediary, not even that of Moshe Rabbeinu, and declares: “I am G‑d, thy G‑d!”

The lesson is highly instructive:

No matter what the status of the Jew is, individually or collectively; no matter how gloomy the position appears to be in the light of human appraisal, the Jew must remind himself every day of Yetzias Mitzrayim [the Exodus from Egypt]—and strive effectively towards complete liberation and freedom, in a bold manner (“with an outstretched arm”) and to the fullest attainment (“with great wealth”): freedom from all shackles and obstacles in escape from his “Mitzrayim,” [Egypt] in order to reach the height of “priestly kingdom and holy nationhood,” through Receiving the Torah in all respects “as in the days of your liberation from Mitzrayim.”

There must be no pause and no hesitation on this road; there must be no resting on one’s initial accomplishments; one must go on and on, higher and higher, until one apprehends and experiences the call: “I am G‑d, thy G‑d!” Public letter, 1959

From the day on which the Jewish people came out of Egypt, out of the house of bondage, they were taken out forever of the category of slavery, transposed into a new category, that of free men. However, the transition from slavery to freedom is not a onetime happening, but a continuous process. It demands frequent and constant reflection so as to experience once again, in a personal way, the coming out from slavery into freedom, and to make the proper conclusions therefrom, conclusions that have to be expressed not only in thought and in words but especially in a deep penetrating feeling which permeates the whole being, down to actions, to a corresponding conduct in all details and aspects of the everyday life.

Hence, although the Exodus from Mitzrayim [Egypt] of each and every Jew, together with their possessions, etc. took place in one day, the true liberation, the spiritual liberation, including also from all constraints and limitations, is something that is accomplished through daily reflection and remembrance, as it is written, “In every generation, and in every day, a Jew should consider himself as though he personally came out this day from Mitzrayim.” Public letter, 1982

Q Seder plate

Q Shemurah matzah

Q Wine/grape juice

Q Hard-boiled egg

Q A roasted piece of meat or poultry, e.g., chicken neck

Q Romaine lettuce

Q Ground horseradish

Q Charoset (mixture of fruits and nuts; e.g., apples, pears, walnuts)

Q A seder-plate vegetable; e.g., cooked potato or raw onion

Q Saltwater

Q Candles

Q Haggadah

Beware of Chametz!

Throughout the festival of Passover, the Torah forbids the owning, eating, or derivation of any benefit from chametz. Chametz, or “leaven,” refers to any food in which grain and water come in contact long enough to possibly ferment.

Commercially produced foods used during the festival should therefore be certified “Kosher for Passover.” And in the weeks before the festival, we remove all chametz from our homes. On the night before Passover—this year, we perform this on Thursday evening, April 10—we conduct a search for any remaining chametz; on the following morning, we burn what we found and renounce all ownership of any leaven that may have escaped our notice.

Chametz that one wishes to have after Passover should be sold to a non Jew for the duration of the holiday. This sale must be enacted properly; to sell online, see the web address on page 19.

For the seder , a table is set with the matzah, a cup for wine, and a kaarah (plate) that holds six items. The arrangement of these six items varies with local tradition; the Chabad custom is illustrated below—along with clarification about each item and additional insights.

A Matzah The Torah instructs us to eat matzah on Passover eve to recall the incredible speed with which G d extracted the Jews from Egypt. Our ancestors did not have time for the dough they had prepared to rise, and on their first stop outside of Egypt they hurriedly baked it into matzah. We use three matzahs for the seder.

It is especially preferable to use handmade shemurah matzah: it is circular, without start or end, symbolizing G d’s infinity; its grain is protected against contact with water from the time of its harvesting; and it is handmade, replicating the matzah baked in Egypt and ever since.

See “The Bread of Authenticity.”

B Wine For the seder, the sages ordained that each person drink a total of four cups in the course of the proceedings. If wine is unworkable due to young age, health, or other factors, grape juice may be used.

C Zero’a (“arm”); a small roasted segment of meat or poultry. Some use a shank bone; others, a chicken leg or neck. It recalls the Passover offering in the Jerusalem Temple, itself a commemoration of the Paschal lamb eaten in Egypt. This item is not eaten at the seder.

D Beitzah, a cooked egg; to recall the chagigah—personal festive offering brought on all festivals, including Passover. The absence of the Holy Temple evokes a sense of mourning. Hence the egg, a traditional mourner’s food (its oval shape symbolizes the life cycle). It is a common custom to dip it into Saltwater and eat it at the start of the seder’s meal.

See “The Seed of the Redemption.”

E Maror, “bitter herbs,” invoke the bitter agonies of servitude. Maror’s precise identification is debated; prevailing customs call for romaine lettuce, horseradish, or both. Note that romaine is not bitter unless it is left unharvested for too long; similarly, our ancestors arrived in Egypt as royal guests of their relative (Joseph, the viceroy), but as their stay lengthened, their fate became increasingly bitter.

F Maror a second helping, because maror is used twice during the seder.

See “Channeling Bitterness.”

G Charoset, “edible clay”; a mixture of ground raw fruit and nuts with a dash of wine to recall the thick mortar with which our enslaved ancestors constructed cities for Pharaoh. (The maror is dipped in charoset before it is eaten.)

H Karpas, a vegetable. Prevalent options include celery, parsnip, radish, cabbage, raw onion, or cooked potato. It is dipped in Saltwater during the seder to pique the curiosity of children (of all ages!).

See “From Soil to Soul.”

THE BREAD OF AUTHENTICITY

Bread and matzah are both made from the same dough, but while bread has undergone a process of fermentation and changed its appearance, matzah still retains its original form. Matzah symbolizes the key to Jewish survival in the Egyptian exile: remaining true to their beliefs and values despite the oppression they were subjected to. Matzah points the way forward for us in all areas of our lives—remain loyal to who you really are and don’t become a puppet to the whims of the time or environment. This is the path to redemption.

Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Alter of Ger (1847–1905), Sefat Emet, Pesach 5658

THE SEED OF THE REDEMPTION

A freshly laid egg appears to an uninformed onlooker as an end product. In truth, it is merely a preparation for the subsequent emergence of an entire creature—a live chick. Similarly, the Exodus appeared to be a completed achievement, but in truth, it merely set in motion the preparations for our final Redemption.

Rabbi Yaakov Leiner of Izhbitz (1814–1878), Seder Haggadah, Sefer Hazemanim, Shulchan Orech

CHANNELING BITTERNESS

Our passion for performing goodness is symbolized by the matzah, whereas our inclination towards wicked choices is represented as maror, for its products are indeed bitter. During the seder, we perform korech—combining matzah and maror. This represents our objective: to unite our passions in G-d’s service by inspiring our evil inclination to embrace the directions of our good inclination, thus forming an upgraded force for goodness.

Rabbi Moshe Alshich (1508–1593), Shemot 13:11

Honest reflection on our spiritual lowliness could lead us to consider ourselves unworthy of G-d’s love. But look at this karpas vegetable! It was buried in dirt with only its leaves piercing the soil. And now it graces a seder table in G-d’s service. G-d did the same with our ancestors, and He will do it for us as well. We can rise from a spiritually vegetative state, rise from the dirt, join the King’s table, and reach tremendous heights.

Rabbi Yerachmiel Yisrael Danziger (1853–1910), Yismach Yisrael, Haggadah Shel Pesach, Karpas

ׁשׁ דֵקַ

Sanctify Recite the kidush over the first cup of wine. If you cannot drink wine, grape juice may be used. It is appropriate for women and girls to light the festival candles on/near the seder table before sunset (and after nightfall on the second night). See p. 19 for the candle lighting blessings. While drinking the four cups of wine or eating matzah, we recline (lean to the left) as a sign of freedom and luxury.

ץחַרְוּ

Cleanse Ritually wash your hands (as before eating bread), but without reciting a blessing.

ספַּרְכַּ

Greens Eat a small piece of vegetable dipped in saltwater in order to stir the children’s curiosity, so that they ask about tonight’s unusual practices.

In addition, dipped appetizers were a practice of royalty, hence a sign of freedom, whereas saltwater evokes the tears of our enslaved ancestors.

ץחַי

Divide · Break the middle matzah in half. Put aside the larger half to be eaten at the end of the meal (Step 12— afikoman); reinsert the smaller half between the two whole matzahs; it is the symbolic “bread of poverty” over which we retell the story of the Exodus. Some use the afikoman to keep the children sederfocused by appointing them as afikoman guardians and suspending it over their shoulders—reminiscent of the unleavened dough that accompanied our ancestors from Egypt, “bundled in their robes upon their shoulders” (Exodus 12:34). Others hide the afikoman and reward the child who finds it.

דֵיגִמַ

Tell Pour the second cup of wine. If there are children present, they pose the Four Questions to the adults. If not, the adults pose them to each other. Those who are celebrating alone pose them aloud to themselves.

In response, read the Haggadah’s narrative of the Exodus that incorporates history, textual analysis, prayers, and songs. A summary of the contents of the magid section is provided on pp. 12–13, and selected highlights appear on pp. 14–15.

At the conclusion of this step, drink the second cup of wine.

6

Wash Wash your hands ritually and recite the blessing that concludes with al netilat yadayim

7 MOTZI איצָוּמַ

Bring Forth In preparation for eating the matzah, touch the three matzahs and recite the blessing Hamotzi —“Blessed are You G d . . . who brings forth bread from the earth.” Proceed immediately to the next step.

8 MATZAH הצָמַ

Unleavened Bread Touch the top two matzahs and recite tonight’s unique blessing over “the eating of matzah.” Eat a piece from each of them. Matzah recalls the haste with which our ancestors left Egypt. There was no time to allow their dough to rise, so they hurriedly baked it while it was unleavened. For the blessings recited over the matzah, see p. 15.

9

MAROR רְוּרְמַ

Bitterness · Recite the blessing over the maror, bitter herbs, symbolizing the bitterness of slavery. Before eating, dip it in charoset—the paste resembling the mortar used by our ancestors in forced labor.

10 KORECH ךְרְוּכַּ

Wrap Dip a second portion of bitter herbs in charoset and place it between two pieces of matzah (use the bottom matzah of the aforementioned three in the Motzi step) to create a matzah maror sandwich.

Set Table · Enjoy a festive meal. It is customary to begin with the egg from the seder plate.

Hidden · Retrieve and eat the afikoman (see step 4), which represents the original afikoman (“dessert”) eaten at the end of the seder meal—the meat of the Passover lamb.

ךְרְבֵּ

Bless Recite the Haggadah’s “Grace after Meals” over the third cup of wine, and then drink the wine.

לְלְה

Praise · Pour the fourth cup of wine.

Pour a fifth cup (just one for the table, not for each individual). This is not consumed; it is the Prophet Elijah’s Cup, demonstrating that, in addition to the four cups of our past liberation, we anticipate our future, ultimate Redemption that will be heralded by Elijah the Prophet.

Open the door of your home for the passage indicated in the Haggadah; it signifies trust in G d’s protection, as well as our longing to greet Elijah as he announces our final Redemption.

Recite the Hallel (psalms of praise) to thank G d for the miracles of the Exodus.

15 NIRTZAH הצָרְנ

Accepted Having fulfilled the seder’s steps as prescribed, we are confident that G d accepts our performance. In conclusion, we joyously proclaim: “Next Year in Jerusalem!”

The most robust of all the seder steps is Magid —“narration.” It is the platform for the most meaningful discussions of the night, as it leads us to verbally and mentally relive the dramatic dawn of Jewish history. As the main body of the seder (“order”), magid is carefully structured. Reviewing its structure in advance will help you avoid disorientation while experiencing its shifts in gear.

Before we begin the recital of magid, we extend an invitation to individuals who may be needy or otherwise seder less, assuring them that we are delighted to have them join us at our seder.

Our sages taught that the Exodus story we will recount tonight should ideally be couched as our response to questions posed by children. To that end, magid begins (after a brief intro) with the children’s Four Questions (see p. 14). In response, we offer a summarized explanation—we were slaves in Egypt, G d redeemed us, and He directed us to verbally review the experience (see p. 14). This summary is followed with a brief discussion to establish the source of tonight’s mitzvah of recounting the Exodus—illustrated with an anecdote involving some of Jewry’s greatest sages who gathered at a seder to discuss the Exodus until dawn.

The Four Sons

The Torah directs us to retell the story to our children—but not all children are alike. Humans tend to possess dissimilar abilities and diverse personalities, and they require individualized channels of education. This segment of the Haggadah identifies four classic personality types that the Torah addresses while indicating the specific method of interaction appropriate for each of them.

The summarized Exodus saga offered earlier was a warm up; we now embark on a detailed treatment.

Our sages advise us to launch the discussion with our lowly origins before working our way up to the glory in which we bathed at the story’s conclusion. We therefore reach back to our humble origins in pagan Mesopotamia, where our forefather Abraham’s family was steeped in idolatry. We describe G d’s leading Abraham to the Holy Land, where He informed Abraham that his descendants would endure foreign slavery followed by glorious redemption. We move on to explore our ancestors’ suffering in their Egyptian exile and then finally arrive at the dramatic unfolding of G d’s redemption through a series of supernatural blows to the mighty Egyptian empire.

The Haggadah relies on the framework provided by the summary of the Exodus that appears in Deuteronomy (26:5–8). Its verses are broken down, line by line and sometimes word by word, with snippets of classic rabbinic commentary inserted to explain or expand.

Gratitude

Our description of the amazing miracles G d performed on our behalf during the Exodus leads us to erupt with the “Dayenu” song of gratitude. Essentially, it is a list of the many kindnesses and blessings G d showered on us from the Exodus until our arrival in the Land of Israel and the Holy Temple’s construction.

Mitzvot

We have concluded the story of the Exodus; it is time to discuss the three edible mitzvot of the night—the actions that G d asks from us in return for His salvation: the paschal offering that was brought in the Temple; eating the matzah; and partaking of the bitter herbs (maror). For this passage, see p. 15.

Praise

We conclude the magid section by singing psalms in G d’s praise and then reciting blessings over our redemption and drinking the second cup of wine.

The Four Questions

G-d instructed His liberated nation to discuss the Exodus on this night. We begin with curiosity-arousing inquiries—for progenies to pose to parents, and for individuals to ask themselves.

What makes this night different from all [other] nights?

On all nights-we need not dip even once; on this night we do so twice!

On all nights we eat chametz or matzah, and on this night only matzah.

On all nights we eat any kind of vegetables, and on this night maror!

On all nights we eat sitting upright or reclining, and on this night we all recline!

Avadim

Hayinu

Three-Sentence Summary

This is a lead-in to the Haggadah that sums up tonight’s story, mission, and scope of duty.

We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and the L-rd, our G - d, took us out from there with a strong hand and with an outstretched arm. If the Holy One, blessed be He, had not taken our ancestors out of Egypt, then we, our children and our children’s children would have remained enslaved to Pharaoh in Egypt. Even if all of us were wise, all of us understanding, all of us knowing the Torah, we would still be obligated to discuss the Exodus from Egypt; and everyone who discusses the Exodus from Egypt at length is praiseworthy.

Rabban Gamliel

Edible Messages

ןבר לאילמג

This section is indispensable. Reading it satisfies tonight’s verbal obligations, and in clarifying the seder’s edible duties, it solves questions posed at the seder’s start.

Rabban Gamliel used to say: Whoever does not discuss the following three things on Passover has not fulfilled his duty, namely: Passover (the Passover sacrifice), Matzah (the unleavened bread) and Maror (the bitter herbs).

חספ The Passover lamb that our ancestors ate during the time of the Beit Hamikdash: For what reason [did they do so]?

Because the Omnipresent passed over our ancestors’ houses in Egypt, as it is said:

“You shall say: It is a Passover offering to the L-rd, because He passed over the houses of the Children of Israel in Egypt when He struck the Egyptians with a plague, and He saved our houses. And the people bowed and prostrated themselves.”

הצמ This matzah that we eat: For what reason? Because the dough of our ancestors did not have time to become leavened before the King of the kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed be He, revealed Himself to them and redeemed them. Thus, it is said: “They baked matzah cakes from the dough that they had brought out of Egypt because it was not leavened; for they had been driven out of Egypt and could not delay, and they had also not prepared any [other] provisions.”

Hold the three matzahs (while covered with the cloth) and recite the following:

Baruch atah Ado‑nai, Elo‑heinu melech ha’olam, hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from the earth.

Let go of the bottom matzah and recite the following, bearing in mind that it also applies to the eating of the korech sandwich, and to the eating of the afikoman:

Baruch atah Ado‑nai, Elo‑heinu melech ha’olam, asher kideshanu bemitzvotav, vetzivanu al achilat matzah.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us concerning the eating of matzah.

רורמ This maror that we eat: For what reason? Because the Egyptians embittered our ancestors’ lives in Egypt, as it is said: “They made their lives bitter with hard service, with mortar and with bricks, and with all manner of service in the field; all their service that they made them serve with rigor.”

Enliven your seder by posing and discussing the following questions with family and friends.

What are some pedagogic lessons we can learn from the structure of the seder ?

What is your funniest seder memory?

When you think of Passover, which one person comes to mind more than any other?

Can you suggest a lesson that can be derived from Hillel’s korech sandwich?

Matzah symbolizes commitment, while wine symbolizes appreciation. In what ways are these traits important for one’s relationship?

What is a unique Passover custom or tradition in your family?

What do you enjoy most about Passover?

What are some dos and don’ts for dealing with the Pharaohs of our times?

In what way are slavery and freedom relevant to our lives today?

Who were Shifrah and Puah?

Our sages instructed that in each generation, we must view ourselves as if we personally experienced the Exodus.

What does this mean? How is it possible?

There were eras in which Jews refrained from using red wine at the seder.

When was this, and why?

What is the oldest extant Haggadah?

5 We can satisfy our daily obligation with a mental recollection, and as briefly as we wish. By contrast, our Passover recollection must be (a) verbal, (b) elaborate, and (c) delivered in response to an inquiry.

4 The framework of our —arrangedHaggadah as an exposition to Deuteronomy 26:5–8—is already attested to in the Mishnah (Pesachim 10:4), which was itself redacted around the year 200 CE. The oldest surviving Haggadah manuscripts were discovered in the Cairo Genizah and (using paleographical -consider ations) have been dated to the eleventh -cen tury. One manuscript housed at the University of Pennsylvania (Halper 211) contains most of the ;Haggadah fragmented selections from a different manuscript are stored at the JTS Library (MS 9560).

3 Red wine is preferred for the four cups, according to the Code of Jewish Law Orach( Chayim 472:11). A seventeenth-century commentator to the Code, Rabbi David Segal (d. 1667), notes that red wine is appropriate because the Bible considers it fancier than white wine. However, he adds that in his day, the Jews of Poland avoided red wine for the .seder He cryptically notes that contemporary antisemites, associating the wine’s redness with blood, charged that Jews murder Christian children in order to mix their blood into the matzah (and wine). This ridiculously false but deadly claim caused much oppression and many massacres of Jews. (Today, the original practice of seeking red wine as an initial preference has been restored.)

What is their association with the Passover story? to bond with the infinite G-d through performing a mitzvah, studying Torah, and acting with kindness to others. Our body then becomes a companion instead of a captor.

The Torah tells us to recall the Exodus daily (Deuteronomy 16:3).

So what is unique about the mitzvah to retell the story of the Exodus on Passover eve?

2 One interpretation: The true “we” is not our -cor poreal selves, but our Divine souls. Our souls are trapped and enslaved within a body that is antithetical to spirituality. It is our duty to facilitate its exodus, which is achieved by permitting our souls

A Talmudic tradition (Sotah 11b) identifies the midwives as a mother-daughter team: Shifrah was Moses’s mother, Jochebed; and Puah was her daughter, Miriam. Rabbi Efraim of Luntshitz (1550–1619), in his biblical commentary Keli ,Yakar explores the possibility that they were Egyptian women who risked their lives to save innocent Jews.

1 Shifrah and Puah ran midwife services for our ancestors in Egypt. Pharaoh ordered them to -mur der all male Hebrews at birth, but they heroically disobeyed. Pharaoh instead had his forces throw Jewish babies into the Nile.

The Torah describes Passover as extending for seven days, designating the first and seventh days as “sacred” days on which it is forbidden to engage in certain “labors.”

Outside of Israel, this results in an eight-day holiday, with the first two and final two days as the sacred days. This year, the final two days of Passover begin on Friday evening, April 18, and conclude on Sunday evening, April 20.

Each of these final two days of Passover have their own theme.

The Seventh Day

On the fifteenth day of the month is G d’s festival of matzot: for seven days you must eat matzot. . . . On the seventh day, hold a sacred assembly and do no laborious work.

Leviticus 23:6–8

Every Action Counts

We should always view ourselves as equally balanced with merits and faults, and view the world, too, as equally balanced with merits and faults. . . . Therefore, if I perform but one mitzvah, I can tip the balance—my own and the entire world’s—and effect personal and global deliverance and salvation. Maimonides (1138–1204), Mishneh Torah, Laws of Repentance 3:4

The Messianic Era

The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the kid goat. . . . They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, for the earth will be filled with the knowledge of G d as the waters cover the sea. . . . G d will raise a banner for the nations and gather the exiles of Israel; He will assemble the scattered people of Judah from the four corners of the earth.

Isaiah 11:6–9, 12, read during the service of the eighth day of Passover

The Sea and Its Song

On the seventh night of Passover, the Jewish people entered the Sea of Reeds [and it split for them]. In the morning, they sang a song of praise to G d. This is why we read the “Song of the Sea” from the Torah on the seventh day of Passover. Rashi (1040–1105), Exodus 14:5

A Messianic Feast

The Baal Shem Tov would call the final meal at the end of the final day of Passover seudat mashiach, the Messiah meal. This is because on the final day of Passover the radiance of the Mashiach shines. . . .

Rabbi Shalom Dovber of Lubavitch instructed that every participant in the seudat mashiach should drink four cups of wine.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (1880–1950), cited in Hayom Yom, 22 Nissan

after 8:57 PM*

/ Nissan 5785

Holiday ends: 9:13 PM

Holiday ends: 9:02 PM

Sell** and burn chametz before 12:22 PM

Search for chametz after 8:52 PM at 8:10 PM

Finish eating chametz before 11:13 PM at 7:59 PM

after 8:59 PM*

after 9:11 PM*

*Light only from a preexisting flame.

**To sell your chametz online, visit chabadwinnipeg.org/chametz

FOR HOLIDAYS OCCURRING

FOR HOLIDAYS, APRIL 12, 13, 19

FOR SHABBAT, APRIL 11

Baruch atah Ado‑nai, Elo‑heinu melech ha’olam, asher kideshanu bemitzvotav, vetzivanu lehadlik ner shel. . .

FOR HOLIDAYS OCCURRING ON SHABBAT, APRIL 18 Shabbat veshel Yom Tov.

FOR SHABBAT, APRIL 11 Shabbat kodesh.

FOR HOLIDAYS, APRIL 12–13, 19 Yom Tov.

ON THE FIRST TWO NIGHTS OF PASSOVER ADD

Baruch atah Ado‑nai, Elo‑heinu melech ha’olam, shehecheyanu, veki’yemanu, vehigi’anu lizman hazeh.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us to kindle the light. . .

FOR HOLIDAYS OCCURRING ON SHABBAT, APRIL 18 of the Shabbat and of Yom Tov.

FOR SHABBAT, APRIL 11 of the holy Shabbat.

FOR HOLIDAYS, APRIL 12, 13, 19 of Yom Tov.

ON THE FIRST TWO NIGHTS OF PASSOVER ADD

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the Universe, Who has granted us life, sustained us, and enabled us to reach this occasion.

COMMUNITY SEDER

Ahava Halpern Building, 1845 Mathers Ave.

Enjoy a delectable catered dinner, complete with kosher wines and brisket, all as part of the traditional Seder!

CHABAD JEWISH LEARNING CENTRE

204.869.7631

RABBIS@CHABADWINNIPEG.ORG

WWW.CHABADWINNIPEG.ORG