THE CHABAD TIMES

A Publication of Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester

Celebrate

Come to synagogue on Shavuot for the Reading of “The Ten Commandments” and reexperience The Giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai 3,336 years ago!

Shavuot Services @ Chabad Wednesday, June 12, 9:30 a.m. followed by Deluxe Dairy Pizza Kiddush

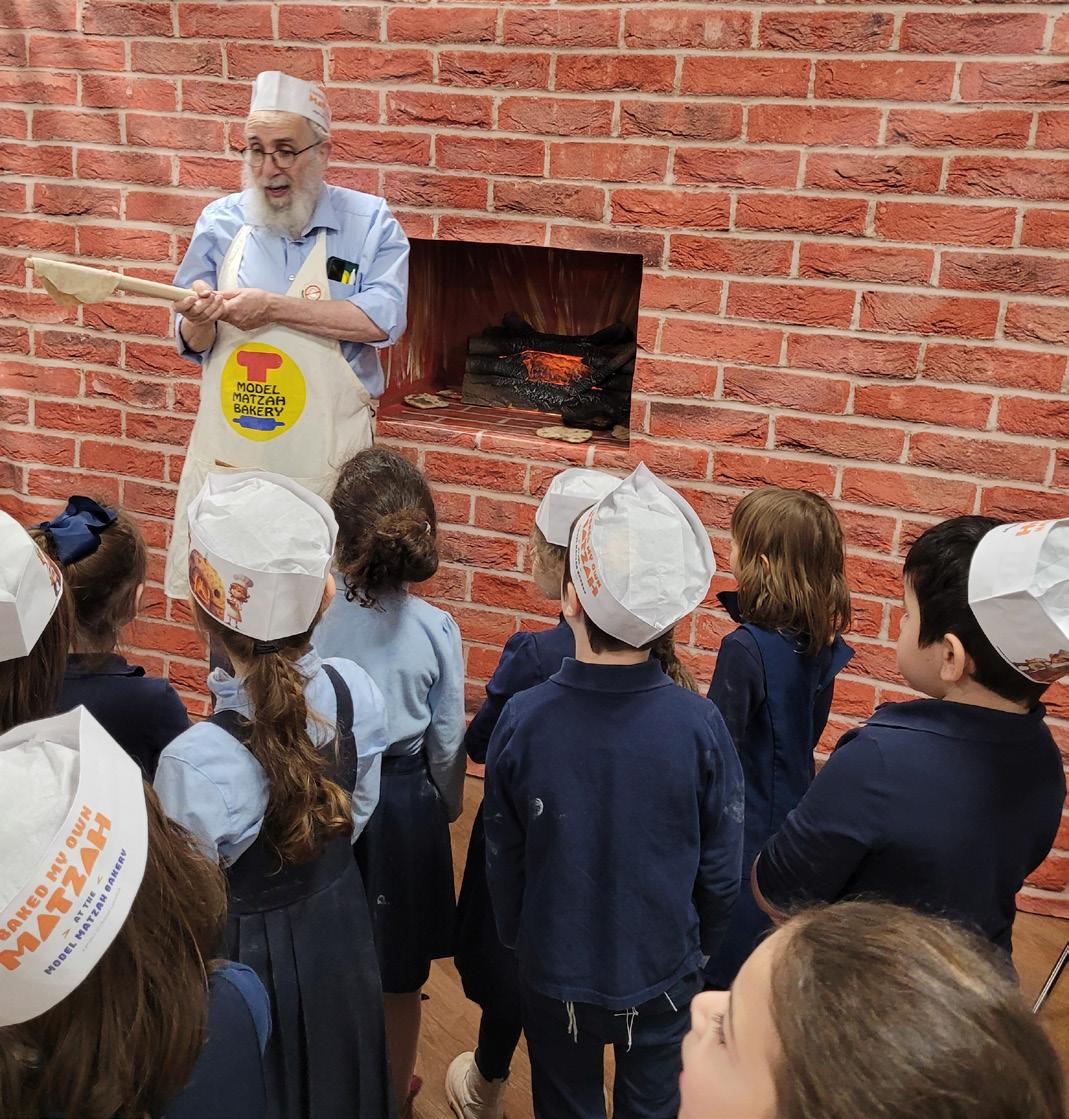

42 years of the Matzah Bakeryand it’s still a hit!

How many people on this planet today can say that they are celebrating their 3,336th wedding anniversary?

On Shavuot (June 12 - 13) millions of Jews all over the world will celebrate and toast their wedding with G-d on Mount Sinai.

On the day of the Giving of the Torah to the Jewish people, G-d Himself was the groom and the Jewish people were the eager, if slightly overwhelmed, bride. Amidst thunder and lightning, approximately three million Jews fresh from their liberation from Egypt stood under a very special Chupah canopy: The Midrash tells us that Mount Sinai itself lifted up and was our Chupah. We heard G-d revealing Himself to an entire nation as He gave us the Torah. The Torah was the Ketubah, the wedding contract. It served as the reciprocal agreement of devotion and love between “husband” and “wife” - each giving, each receiving.

step in life such as marriage, child rearing, career, etc., - with the proper preparation - can be so much more rewarding. The same applies to our Holidays.

Let us take a look at what the Jewish people did to prepare for the Revelation at Mt. Sinai. When the Jews departed from Egypt, their level of spirituality left a lot to be desired. Our Sages tell us that whilst in Egypt many Jews had gotten involved with idolatry. They had fallen to the 49th level of impurity (there are 50 levels) and were literally shlepped out of Egypt in the nick of time. They did not even have 18 extra minutes to let the bread dough rise, such was their hurry in leaving the decadent Egyptian environment. At that point, the Jewish people were spiritually far from Sinai. Yet only seven weeks later they had transformed themselves into a nation worthy of the title, “a Kingdom of Priests and a Holy Nation.”

Under the Chupah the bride accepts the wedding contract. The Jewish people’s response to G-d was “Naaseh Venishma - All that You ask we will do and we will (seek to) understand.” Our acceptance of the Torah was unconditional, enthusiastic. After all, it was the purpose for liberation from the slavery of Egypt. We were being chosen and wanted, the desired ones of G-d’s plan for a just world, a world of law, goodness and kindness that would be both spiritual and practical for us and for humankind.

Our Sages tell us that when we celebrate a Holiday, the singular atmosphere that surrounded the original events of the festival, with all its soul stirring aspects, becomes reawakened and actually “reoccurs” as we remember the event each year with the advent of the festival. As we prepare for our “wedding” on Shavuot it is also appropriate to reawaken within ourselves the unity, dedication, commitment and enthusiasm that our ancestors had at Mt. Sinai.

In other words, to fully appreciate the Shavuot Holiday we need some real preparation. In fact, any meaningful

Kessler Family

Chabad Center 1037 Winton Rd. S. Rochester NY 14618

585-271-0330

chabadrochester.com

Rabbi Nechemia Vogel

Rabbi Dovid & Chany Mochkin

It is not easy to refine oneself and become a better person. It seems to be more reasonable for us to accept our character, nature and tendencies even with the flaws, because we are led to believe that real change is almost impossible. Yet in those seven weeks, our ancestors showed us that it is possible. Preparing for our “wedding” on Shavuot thus entails taking a look at ourselves and making an effort to make a real change for the better.

The Midrash relates that prior to giving the Torah, G-d demanded that the Jews provide guarantors for the Torah. The only guarantors acceptable to G-d were the Jewish children. With such a central role in the events of Shavuot, it is fitting that all children, even tiny infants, be present in synagogue when the Ten Commandments are read from the Torah on the morning of the first day of Shavuot, June 12. After all, they are the next link in the unbroken golden chain of tradition. May we all merit to see much Yiddishe Nachas from all of them! Amen! Wishing you a Happy & Inspiring Shavuot, Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester

Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester NY

Chabad Of Pittsford 21 Lincoln Ave. Pittsford NY 14534

585-340-7545

jewishpittsford.com

Rabbi Yitzi & Rishi Hein

Chabad Young Professionals 18 Buckingham St. Rochester NY 14607 585-350-6634

yjprochester.com

Rabbi Moshe & Chayi Vogel

Rohr Chabad House @ U of R 955 Genesee St. Rochester NY 14611 585-503-9224 urchabad.org

Rabbi Asher & Devorah Leah Yaras

Chabad House @ R.I.T. 3018 East River Rd. Rochester NY 14623 347-546-3860

chabadrit.com

Rabbi Yossi & Leah Cohen

Echoes are a naturally occurring phenomenon formed by sound waves bouncing off obstructions. Every sound has an echo as, sooner or later, the sound wave emanating from the noise-source meets an immovable barrier and is reflected.

The one exception to this hard and fast scientific principle was when G-d descended on Mt. Sinai to declaim the Ten Commandments to His awestruck creations. Every living being froze in anticipation and adoration as the awesome sounds of G-d resonated throughout the universe.

Resonated maybe, but there was no echo. The greatest sound and light event in history was a strictly onetime production with no residuals or encore. He came, He spoke, we heard.

When humans produce sound, the audio transmissions have physical characteristics: loudness, frequency and pitch. Upon being transformed

The Torah describes G-d as “descending” onto Mt. Sinai to proclaim the Ten Commandments.

The expression seems strange on two counts:

Firstly, the fact that G-d is described as descending, surely G-d is neither above nor below. G-d is everything and everywhere. He is found in all places and all times equally. Neither male nor female, neither up nor down, permeating and encompassing alike - He just is.

Of even more interest is the fact that G-d seems to instigate the connection; He came down to us without expecting us to come up the mountain to Him. I always understood that the purpose of Torah and mitzvot is to

Elisha GreenbaumAdapted from the works of the Rebbe by

into an electronic format they can be captured on magnetic tape or burnt onto a CD. Even if diced into fragments and transmitted through space via radio waves, they still consist of basic physical characteristics and must be unscrambled and re-presented in the original format in order for a human recipient to process them as intelligible information.

The most faithful Hi-Fi system in the world, however, will not process and accurately present all of the original communication. The natural obstructions ever present in every environment will distort, reflect and disguise some small part of the message. Unavoidably, some sound waves will be bounced back, rejected by the recipient as it were, and be lost to the listener as an echo.

When G-d speaks there is no echo. When G-d communicates there is no need to transform it to another medium. G-d broadcasts to every one of us, on the frequency best adapted

energize and elevate the Jews. After all, G-d started off perfect and hasn’t changed since; but we’re the ones who need to shape up. We’re the people who should be setting off on the great journey that starts on earth and ends at Sinai. Why should we expect G-d to come down to us?

Obviously this notion of G-d’s descent from on high is metaphorical and not literal. However the description is possibly also symbolic of the effort each of us is expected to make when reaching out to others who need us.

We all have information to share and skill sets that others would benefit from learning. It is tempting to assume that those who wish to learn will approach you first and request to be taught. It is too easy to sit at home

for us to integrate and utilize every last fraction of the message. Nothing can stand in its way, nothing bounces back and no part of it is rejected as unsuitable.

When a Jew learns Torah, G-d is speaking directly to him. By opening oneself up to the undifferentiated word of G-d, we accept G-dliness into ourselves. The Torah permeates our very being and transforms our bodies and lives into a sounding board broadcasting G-d’s infinite message.

and wait for people to come looking for you. Yet the lesson of G-d coming down to the Jews is that we have no right to sit on our hands when those who need us are waiting.

Some people need Judaism, others need faith or love. There are hungry souls out there who need to be fed and jobs need to be found for the unemployed. Don’t be proud, be generous. People need you. You have gifts to share and knowledge to impart. Go out and teach. Reach out to others. You may feel that you are going below your current station; it may feel like a physical or spiritual descent from your present position in life, yet the good and G-dly way is to lower yourself into the world and share your bounty with those who need you most.

The Midrash tells us that when the Jews stood before Sinai to receive the Torah, G-d said to them: “I will not give you the Torah unless you provide worthy guarantors who will assure that you will observe its laws.” After offering answers that G-d rejected the Jews declared, “our children will serve as our guarantors!” “They truly are worthy guarantors,” G-d replied. “Because of them I will give the Torah.”

The white-bearded sages and the erudite rabbis weren’t sufficient to satisfy G-d’s “need” for a guarantor. Why? Who can better guarantee the transmission of the Law than the intellectuals, philosophers, and theologians who devote their lives to developing it and teaching its wisdom to myriads of disciples throughout the ages? Why did G-d prefer the Torah study of the child whose mind is constantly distracted, moving on to far more important subjects, such as which game to play during recess, the caliber of the snack which his mother

packed in his lunch bag, or his plans for summer vacation?

Yet, there is a unique quality exclusive to a child’s method of learning, a quality which is appealing to G-d and is the most effective guarantee for the future of the Torah.

One cannot study without questioning. “Why?” “What is the basis for your statement?” and “Why can’t it be done differently?” are rudimentary and indispensable phrases for any serious student. However, the child and adult harbor very different intentions when voicing these questions: the adult is doubting the very premise of the idea/law/principle which is being taught, and if the answer is not to his liking, he might altogether reject the teaching. Conversely, the child has an acute curiosity, but he doesn’t doubt that which he is taught; he is aware that his wisdom and knowledge is limited and therefore accepts what his parent or teacher says. He asks questions because he wants to understand more, not because he is skeptical of the information he has heard.

We are commanded to study Torah, and this involves closely examining every word of both the Written and Oral Law. G-d doesn’t want us to blindly accept His teachings, he wants us to use our intellectual skills to analyze, probe, and question. However, we must never lose sight of the fact that our minds are inherently limited, whereas G-d’s wisdom is infinite. We are obligated to question, but at the same time to unquestioningly accept each word of Torah to be the absolute truth. Only this method of study ensures the eternal survival of the Torah, guaranteeing that its teachings won’t be forsaken because of doubts which inevitably will arise (after all, that is the nature of intellect—it can always be questioned and doubted).

Receiving Torah begins with activating our inner child – the ability to fully accept its truth. And then we can ask all the questions…

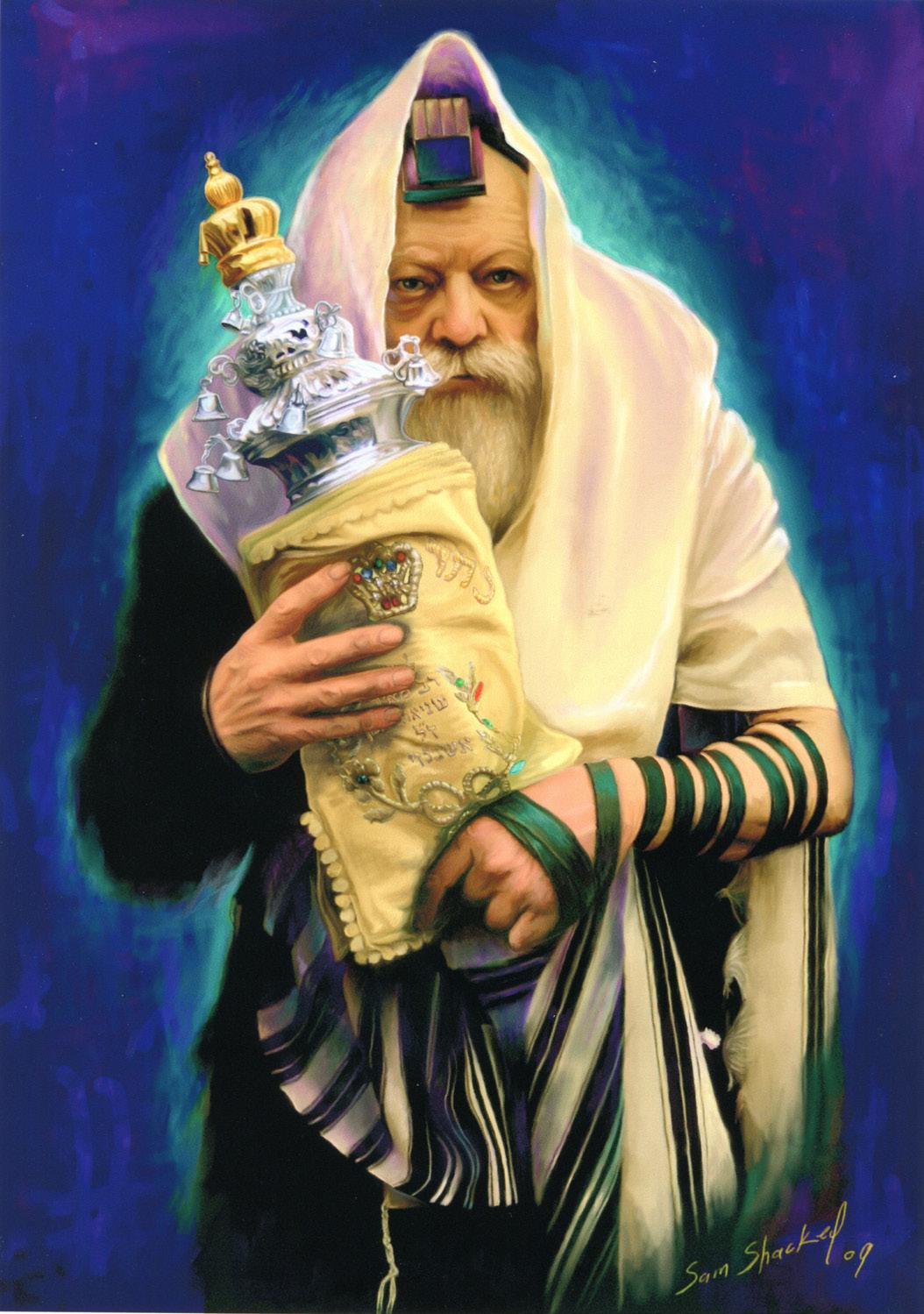

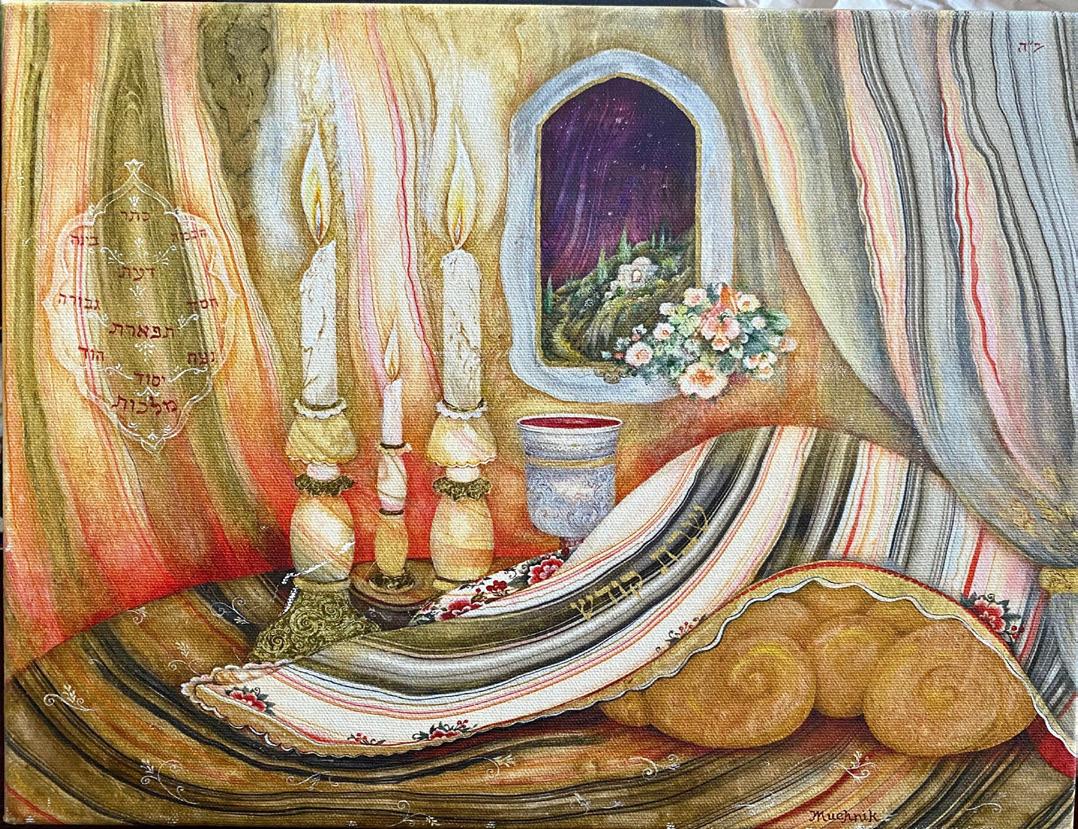

The Rochester Jewish Art Calendar 5785 September 2024 - September 2025

Your Ad/Greeting will be visible all year long to the entire Rochester Jewish Community

• 32 full color pages

• Large size: 10" by 14" closed, 20" by 14" open

• Big boxes that are very useful for appointments, notes, etc.

• Jewish Holidays are clearly shown

• Beautiful full color art on each page

• "The Month in Jewish History" feature

Visit: chabadrochester.com/artcalendar

Dear Ask-the-Rabbi,

My rabbi visited my clinic today and asked me to wrap tefillin. He said it was for our brothers and sisters in Israel. So I did.

On Friday my wife lit Shabbat candles - which she doesn’t always do. She said it was for our brothers and sisters in Israel. Somehow that made sense to her. And to me.

But now I started thinking. I’m an educated man, a doctor, and I try to make sense of things. But once I’m thinking, I don’t have an explanation. How does it work? What’s the mechanism - the cause and effect? And why did it make sense before thinking?

single being.

And in a single being, locality is secondary. What happens in one part of a living being immediately changes the entire organism. Which is how the Jewish people works as well.

Okay, here’s an example you’re probably familiar with: Caenorhabditis elegans. I’ll bet you studied little C. elegans back in medical school - because it is holds the distinction of being the most exhaustively studied and exposed creature in the world.

Dear Puzzled Jew,

Yes, a puzzle - that’s a good example. A jigsaw puzzle where all the pieces connect to make a single whole. Same thing with Jews and mitzvahs. All of our people and all of our mitzvahs fit together to make a single, integral whole. And every piece is needed.

But let me give you a better metaphor, something which you as a doctor can surely relate to. Think of the entire Jewish people as a single living organism, and then it all makes sense.

A living being, I’m sure you realize, is not like some clunky machine. For one thing, machines are made by putting parts together that originally had nothing to do with one another. Even once built, a machine is still a jumble of parts. But a living organism starts off as a single cell that then unfolds itself into an entire creature - and in such a way that even once fully developed and functioning, it remains a singularity.

In other words, unlike a machine, a living being is a

C. elegans is a one-millimeter-long, transparent roundworm with exactly 959 cells (we human organisms have about 75 trillion cells). Researchers hoped that by starting with this one simple paradigm, eventually all the processes and rules that govern life could be explained. And so, by 1980, the fate of each of those cells from egg to adult was already mapped out.

But those researchers never got what they bargained for. In 2002, Sydney Brenner received a Nobel prize for all the time he spent with that little worm. Critics balked. They claimed Brenner hadn’t explained a thing - all he had done was to describe what goes on inside the little critter. And Brenner had to acknowledge they were right. “It’s not a neat, sequential process,” he explained. “It’s everything going on at the same time . . . there is hardly a shorter way of giving a rule for what goes on than just describing what there is.” (my emphasis)

Call that an irreducible singularity. Something whose only description is itself. Which means that if one part were missing, it would not be what it is. And whenever one part changes, the entirety has instantly changed.

Something like a symphony: You can’t provide me a mathematical equation that will produce Beethoven’s Pastoral. The only description I can have is by listening to it. And if one part is changed - a sweet note gone sour, or a thundering triad played softly - the experience of the entire symphony has changed.

Now apply that to the Jewish people. We are one - essentially and integrally one. We have one G d, one Torah, one story to tell and one destiny at which we will arrive. Each one of us has his or her integral part to play. And so, whatever any one of us does immediately redefines the state of our entire people.

Locality is meaningless - it’s not a case of cause and effect. It doesn’t take time for the signal to travel, it needs no medium to carry it, and it doesn’t diminish over space or time. Our entire people spread over the entire globe, from Abraham until you and me - we are all one irreducible singularity. One Jew has done a mitzvah - the entire people is immediately enriched, and that enrichment is felt in every individual.

Take it further: If you somehow connect with another Jew who is struggling with some ethical challenge in life, find that same challenge within yourself, fix it up - and you’ll discover that this other Jew now has an easier time overcoming that struggle. That’s how deeply we are connected.

That also answers your last question: Why did it make sense before thinking? Strange thing: I’ve also asked many Jews to wrap tefillin or light Shabbat candles or do some other mitzvah “for our brothers and sisters in Israel.” Every Jew I have asked immediately gets it. “Of course,” they say. “It’s a mitzvah.”

Because a Jew feels the effect of the mitzvah. And a Jew knows we are a people above time and space.

We are one. Everything else is commentary. Now go do another mitzvah for our brothers and sisters in Israel.

The Torah foretells of a fixed location where the Jewish people would come to serve G-d in the Holy Temple: “But only to the place which the L-rd your G-d shall choose from all your tribes, to set His Name there; you shall inquire after His dwelling and come there. And there you shall bring your burnt offerings, and your sacrifices, and your tithes . . .” (Deuteronomy 12:5-6)

But although we are told that G-d will choose a place, we aren’t yet told what city this is.

Only later, after King David acquired the city of Jerusalem and built the first Holy Temple, do we learn that Jerusalem is the city that G-d chose for Himself. As the verses state, “. . . In Jerusalem, the city which I chose for Myself to place My name there,”

I Kings 11:36 and “. . . In Jerusalem, the city that the L rd had chosen to place His Name there out of all the tribes of Israel . . .” (I Kings 14:21; see also Psalms 132:13)

But Jerusalem’s significance predates King David. In fact, the Temple Mount has played a major role in history since the very creation of man. To quote Maimonides: According to accepted tradition, the place on which

David and Solomon built the altar, the threshing floor of Aravnah, is the location where Abraham built the altar on which he prepared Isaac for sacrifice. Noah built an altar on that location when he left the ark. It was also [the place] of the altar on which Cain and Abel brought sacrifices. Similarly, Adam, the first man, offered a sacrifice there and was created at that very spot, as our sages said: “Man was created from the place where he would find atonement.”

This raises the question: If Jerusalem and the Temple Mount were significant places long before King David, why doesn’t the verse in Deuteronomy name Jerusalem explicitly?

Maimonides in his Guide for the Perplexed explains:

Note this strange fact. I do not doubt that the spot that Abraham chose in his prophetic spirit was known to Moses our Teacher, and to others: for Abraham commanded his children that on this place a house of worship should be built. Thus, the Targum says distinctly, “And Abraham worshipped and prayed there in that place, and said before G-d, ‘Here shall coming generations worship the L-rd.”

• Continued on page 12

This year, on Wednesday, June 12, in synagogues across the world, the Jewish people will stand together once again to experience the Giving of the Torah with the reading of the Ten Commandments. Wherever you are, you are invited to take part - just as you did 3336 years ago.

Our Sages recount that when the Jewish people came to receive the Torah, G-d asked for guarantors. They offered every responsible party they could imagine, but G-d was not satisfied; until they declared, “Our children will be our guarantors!”

So make sure to bring along your guarantors - the children, right down to the newest sponsors - when you come to hear the reading of the Ten Command-ments at the Giving of the Torah on Shavuot.

Times are for the Rochester area only

Tuesday, June 11:

Light the Yom Tov candles at 8:32 p.m. and recite blessings.

Tikun Lail Shavuot during the night.

Wednesday, June 12:

Attend services in the morning to hear the reading of the Ten Commandments.

Light the Yom Tov candles from a pre-existing flame* after 9:45 p.m. and recite blessings.

Thursday, June 13: Yizkor is recited during services. Shavuot ends at 9:45 p.m.

*A pre-existing flame is a flame burning continuously since the onset of the Shabbat such as a pilot light, gas or candle flame.

Boruch A-toh Ado-noi E-lo-hei-nu Me-lech Ho-olom A-sher Ki-de-sho-nu Be-mitz-vo-sov Ve-tzi-vo-nu Lehad-lik Ner Shel Yom Tov.

Bo-ruch A-to Ado-noi E-lo-hei-nu Me-lech Ho-olom She-heh-che-yoh-nu Vi-ki-ye-mo-nu Ve-he-ge-o-nu Liz-man Ha-zeh.

The Holiday of Shavuot

Shavuot is the second of the three major Jewish festivals, (the others are Passover and Sukkot) commemorating the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai 3330 years ago. Shavuot marks the beginning of the Jewish people as a nation. It is the time when G-d pronounced the Israelites as His “chosen people” and “a holy nation”.

The Torah was given seven weeks after the exodus from Egypt, and is considered the culmination of the “birth” of the Jewish people, which began at the exodus on Passover.

The word Shavuot means weeks, for it marks the completion of the seven weeks between Passover and Shavuot during which the Jewish people were extremely eager, counted the days and prepared themselves for the giving of the Torah. During this time they cleansed themselves of the scars of slavery and became ready to enter into an eternal covenant with G-d with the giving of the Torah.

Now, too, as commanded in the Torah, we count the 49 days between the first day of Passover and the festival of Shavuot.

Shavuot also means “oaths”. The name indicates the oaths which G-d and Israel exchanged on the day of the giving of the Torah to remain faithful to each other forever.

The Torah is the very essence of the Jewish people. It is our way of life and the secret of our freedom, our nationhood and our existence. Even before the redemption from Egyptian bondage, G-d told Moses that He would redeem the Jewish people in order that they would receive the Torah. For there can be no true sovereignty for a Jew without Torah.

At Mount Sinai, the entire Jewish nation, millions of men, women and children, witnessed the revelation of G-d as He spoke the words of the Ten Commandments. It is this event, the revelation of G-d Himself, without a mediator,

that established for all of the people, the truth and eternity of the Torah.

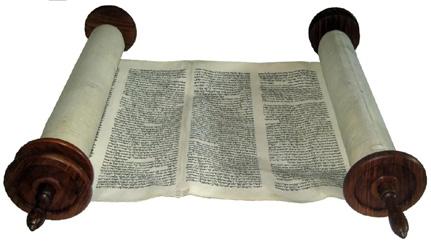

After the Giving of the Ten Commandments, Moses ascended to the peak of Mount Sinai, and stayed there for forty days and nights. During this time, G-d taught him the entire Torah, as well as the principles of its interpretation for all time. He also gave him the two precious stone tablets, in which He engraved the Ten Commandments.

Upon his descent, Moses taught the Torah to the Jewish people. The Torah was then taught and transmitted from generation to generation, until this very day.

The word “Torah” means instruction or guide. The Torah is composed of two parts: the Written Law and the Oral Law. The written Torah contains the Five Books of Moses, the Prophets and the Writings. Together with the Written Torah, Moses was also given the Oral Law, which explains and clarifies the Written law, much like a constitution and its bylaws. It was transmitted orally from generation to generation and eventually transcribed in the Talmud and Midrash.

The Torah relates how G-d created the universe, how the human race came into being from Adam and Eve, how our Fathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob fared, how the Jewish people became a nation, chosen by G-d to be ‘a kingdom of priests and a holy nation’ through receiving and observing the Torah. The Torah contains 613 commandments, of which 248 are positive (what to do) and 365 are negative (what not to do). Masorah (Tradition) In addition to the precepts, commandments and prohibitions written in the Torah, G-d taught Moses more laws, which he was to memorize and orally convey to his successors, who in turn were to uphold this tradition from generation to generation. Many laws and customs have thus been practiced by us traditionally, as if they were actually written in the Torah.

Following the passing of Moses, as G-d promised, He revealed himself to individuals of great piety and spirituality. These are the prophets who recorded G-d’s instruction and messages. In all there are 19 books of the prophets. In all we had 48 prophets and 7 prophetesses whose prophecies were recorded for their everlasting importance.

These include the books like Psalms, Song of Songs, Ruth and Esther, 11 in all. All of which were written by one or another of our prophets by divine inspiration (“Ruach Hakodesh”)

The Torah in its origin and essence is Gd’s infinite wisdom and will. And it is the infinite G-dly wisdom that is concentrated in the human logic and practical laws of the Torah addressing mundane worldly matters.

The Torah, as it deals with practical laws, is the revealed part of the Torah. The internal and mystical element of the Torah, focuses on the G-dly dimension of the Torah and mystical significance of the Mitzvos, which are the teachings of Kabbalah and Chassidut. They are, as referred to in Jewish tradition, the neshama (the soul) and essence of the Torah. Both the hidden and revealed are inseparable parts of the Torah, received from Sinai and transmitted from generation to generation throughout our history.

There are 613 Divine commandments embracing every facet of our lives, both the duties to fellow man and the way to worship G-d. The positive commandments, numbering 248, equal the number of organs in the human body, implying that a person should serve the Creator with every part of his being.

The 365 negative commandments are equivalent to the number of blood vessels in the human body, indicating that when we guard ourselves from transgressing these prohibitions, as we might be tempted to do by desires inherent in the blood, each one of our blood vessels, remains “unblemished” and pure. The negative commandments also equal the number of the 365 days of the year.

Mitzvah literally means commandment. However, it also means companionship (from the Aramaic tzavta - companionship). Upon fulfilling a commandment one becomes united with G-d, who ordained that precept. For, regardless of the nature of the commandment, the fulfillment of G-d’s desire, creates a relationship between the creator and the human who executed it. By fulfilling His wish a person accomplishes an infinite purpose and is in G-d’s “company”.

This is the interpretation of our sages’ statement (Avos

The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Sivan 5784 4:2) “the reward of a mitzvah is the mitzvah”, indicating that the mitzvah itself is the greatest reward, for this sets us in a companionship with the eternal and infinite G-d. All other rewards are secondary in comparison to this great merit.

The Ten Commandments consist of 620 letters, equaling the number of the 613 Mitzvos and the 7 Rabbinical Mitzvos (such as Chanukah, Purim, etc.). 620 is the numerical value of the Hebrew word “Kesser”- a crown. Each mitzvah is considered a part of G-d’s crown. When fulfilling a mitzvah a person offers a crown to the Almighty.

We all know that the Ten Commandments were given on Mount Sinai. Why Sinai? Say the Sages: Sinai is the lowest of all mountains, to show that humility is an essential prerequisite to receiving the Torah.

Why then on a mountain? Why not in a plain - or a valley? The Code of Jewish Law states at the very beginning: “Do not be embarrassed by mockery and ridicule.” For to receive the Torah you must be low; but to keep it, sometimes you must be a mountain.

The Midrash relates that when G-d was about to give the Torah the heavenly angels argued that He should offer it to them. Upon G-d’s request Moses replied, “Have you been in Egypt? Do you have an evil inclination?

This implies that the Torah was given in order to elevate humanity as well as the world in general. Precisely for those who have an evil inclination and need to be refined, was the Torah given.

“Na’aseh V’Nishmah”

Our sages relate that when G-d was about to give the Torah, He offered it first to all of the nations of the world. After inquiring what was written in it, each of them found in the Torah something not agreeable to their system and way of life. When He offered the Torah to the Jewish people, without even asking what it contained, they immediately exclaimed, “We will do and listen.” This uncon-

ditional devotion and acceptance of G-d’s law, prompted G-d to give them the Torah.

Everything connected with the giving of the Torah was of a triple nature: the Torah consists of Chumash (the five books), Prophets, and the Holy Writing (TaNaCH). It was given to Israel, comprised of Kohanim (priests), Levites and Israelites, through Moses, the third child in the family, after three days of preparation, in the third month (Sivan).

The Zohar declares “three are interlocked together: Israel, the Torah, the Holy One, blessed be He.”

Upon their leaving Egypt, when Moses related to the Jewish people that G-d will give them the Torah, the Jewish people were extremely eager and impatiently counted the days. Hence the Mitzvah of counting the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot.

Our Sages relate, that when the Jews camped before Mount Sinai, they were “as one man, with one heart”. Many of their other journeys were characterized by differences of opinion and even strife. However, when they prepared to receive the Torah, the Jews joined together with a feeling of unity and harmony. This oneness was a necessary prerequisite to the giving of the Torah.

The Book of Exodus relates that when G-d gave us the Torah at Mount Sinai, “The people saw the voices.” “They saw what is ordinarily heard,” remark our sages, “and they heard what is ordinarily seen.”

As physical beings, we “see” physical reality. On the other hand, G-dliness and spirituality is only something that is “heard”—it can be discussed, perhaps even understood to some extent, but not experienced first hand.

But at the revelation at Sinai, we “saw what is ordinarily heard” – we experienced the Divine as an immediate, tangible reality. On the other hand, what is ordinarily “seen” – the material world – was something merely “heard”, to be accepted or rejected at will.

On the first night of Shavuot, it is customary to stay up all night and study Torah. Our sages relate that on the night of Shavuot the Jewish people went to sleep, in preparation to receiving of the Torah. At day break, when G-d appeared to give the Torah they were sleeping. In contrast, we now prepare ourselves by studying Torah all night, ready to “receive the Torah” once more when G-d again offers us the Torah with renewed vigor.

It is customary to eat dairy products on Shavuot. A number of reasons have been given for this custom. Among them: the Torah is compared to milk. Also on Shavuot, immediately after receiving the Torah, the Jewish people were required to eat kosher. The only foods available for immediate consumption were milk products.

The custom to eat cheese blintzes on Shavuot is based on a play of Hebrew words. The Hebrew word for cheese is Gevinah, reminding us of the “controversy” of the taller mountains, each claiming to be worthier than Sinai for the privilege of receiving the Torah. They were therefore called Gavnunim - “humps,” because of their conceit, while Sinai, small and humble, was chosen for its humility.

On the second day of Shavuot the Yizkor memorial service is recited

Shavuot is also called Atzeret, meaning The Completion, because together with Passover it forms the completion of a unit. We gained our freedom on Passover in order to receive the Torah on Shavuot.

Another name for Shavuot is Yon Habikurim or the Day of the First Fruits. In an expression of thanks to G-d, beginning on Shavuot, each farmer in the Land of Israel brought to the Temple the first wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates that grew in his field.

Finally, Shavuot is also called Chag HaKatzir, the Festival of the Harvest, because wheat, the last of the grains to be ready to be cut, was harvested at this time of the year. On Shavuot two loaves of wheat bread from the new harvest were offered at the temple in Jerusalem.

Batter:

• 4 eggs

• 1 cup milk

• 1 cup flour

• 1 Tbsp. sour cream

Filling:

• 16 ounces cottage cheese

• 2 egg yolks

• 2 Tbsps. margarine or butter, melted

In many synagogues the book of Ruth is read on the second day of Shavuot. There are several reasons for this custom: A) Shavuot is the birthday and yahrzeit (day of passing) of King David, and the book of Ruth records his ancestry. Boaz and Ruth were King David’s great grandparents. B) The scenes of harvesting, described in the book of Ruth, are appropriate to the Festival of Harvest. C) Ruth was a sincere convert who embraced Judaism with all her heart. On Shavuot all Jews were converts having unconditionally accepted the Torah and all of its precepts.

It is customary on Shavuot to adorn the synagogue and home with fruits, greens and flowers. The reason: FruitsIn the time of the Temple the first fruits of harvest were brought to the Temple beginning on Shavuot. GreensOur Sages taught that on Shavuot judgment is rendered regarding the trees of the field. Flowers - Our Sages taught that although Mount Sinai was situated in a desert, in honor of the Torah, the desert bloomed and sprouted flowers.

• 1/4 cup sugar

• 1 package vanilla sugar

• pinch of salt

• 2 Tbsps. sugar

• 1/4 cup raisins (optional)

• 1/3 cup oil for frying

Cheese blintzes are a special favorite on Shavuot when it is customary to eat a dairy meal. They are served hot, with sour cream or applesauce.

Batter: Combine eggs and milk. Add sour cream and blend well. Add flour gradually. Mix well until batter is smooth. Heat on a low flame a small amount of oil in an 8 inch frying pan, until hot but not smoking. Ladle a small amount of batter (approx. 1 ounce) into pan, tipping pan in all directions until batter covers the entire bottom of the pan. Fry one side until set and golden, (approx. 1 minute). Slip pancake out of pan and repeat until all batter is used. Add oil to pan as necessary.

Filling: In another bowl mix all ingredients for filling. Fill each pancake on golden side with 3 Tbsps. of filling. Fold in sides to center and roll until completely closed. Replace rolled blintzes in pan and fry for 2 minutes, turning once.

Continued from page 7

For three practical reasons, the name of the place is not distinctly stated in the Law, but indicated in the phrase “To the place which the L-rd will choose.” First, if the nations had learned that this place was to be the center of the highest religious truths, they would occupy it or fight about it most perseveringly.

Secondly, those who were then in possession of it might destroy and ruin the place with all their might. Thirdly, and chiefly, every one of the Twelve Tribes would desire to have this place in its borders and under its control; this would lead to divisions and discord, such as were caused by the desire for the priesthood. Therefore, it was commanded that the Temple should not be built before the election of a king who would order its construction, and thus remove the cause of discord.

Indeed, when it came time for King David to acquire the Temple Mount, not only did he insist on paying for it (despite the fact that it was offered to him by Aravnah the Jebusite for free), but he made sure to collect 50 shekels of silver from each one of the tribes (totaling 600 silver shekels). Thus, although technically in the territory of Benjamin (and Judah), all the tribes had a part in acquiring it.

Although we have outlined the significance of Jerusalem, some point to a famous legend about two loving brothers as the ultimate reason why this spot was chosen by G-d. The gist of the story is as follows:

Two brothers had each inherited half of their father’s farm. One of the brothers was married and had a large family; the other brother was single. They lived on opposite sides of a hill. One night during harvest time, the single brother tossed about in bed. “How can I rest comfortably and take a full half of the yield, when my brother has so many more mouths to feed?” So he arose, gathered bushels of produce and quietly climbed the hill to bring

Meanwhile, his brother across the hill also could not sleep. “How can I enjoy my full share of the produce and not be concerned with my brother. He is alone in the world, without a wife or children; who will support him in his old age?” So he arose in the night and quietly brought over bushels of produce to his brother’s barn.

When the next morning dawned, each brother was surprised to find that what they had given away had been replenished. They continued these nocturnal treks for many nights. Each morning they were astounded to find that the bushels they had removed had been replenished.

Then one night it happened. The brothers met on the top of the hill during their evening adventure. And there, they embraced. G-d looked upon this expression of brotherhood and said, “On this spot of mutual love, I wish to dwell. Here My Holy Temple will be built.”

Although it is indeed a very moving and inspiring story, it does not seem to be found in the Talmud and Midrash and its original source remains unclear.

Now, it was only in the times of Kings David and Solomon that Jerusalem was chosen in the sense that from then on it became forbidden to bring offerings anywhere else in the world.

However, in an in-depth discussion about the chosenness of Jerusalem, the Rebbe explains that the events recounted above were not the reason for its sanctity.

Rather, G-d chose the land of Israel in general and Jerusalem in particular as the place for the Divine Glory to rest - not due to any external reasons, but simply because He wished it to be so. Since it was a special place chosen by G-d, it thus followed that our forefathers built an altar and brought offerings there. This sanctity is essential to the spot, and will remain intrinsically linked to His chosen people for all of eternity.

On Shavuot we read one of the most special sections in the entire Torah, the Aseret Hadibrot, the Ten Commandments. Rabbi Saadia Gaon, the brilliant 10th-century Talmudic scholar, philosopher, and Jewish leader, teaches that all 613 mitzvot are encompassed within the Ten Commandments, and he traces each one back to its source.

Taking it a step further, the Zohar teaches that the very first word of the Ten Commandments, the “I” (Anochi) in “I am the L-rd your G-d Who brought you out of the land of Egypt,”1 encompasses the entire Torah.

What kind of word is Anochi? I’m a simple guy from New Jersey. I know that the Hebrew word for “I” is “Ani.” If I wrote the Ten Commandments, which I didn’t, I would have started with the word Ani.

What language is Anochi? What is its origin? At first, I thought it was Spanish. But the surprising answer, found in the midrash Yalkut Shimoni, informs us that Anochi is an Egyptian word!

How is it possible for the word Anochi to be of Egyptian origin? How can it be that the word that encompasses the entire Torah, and the word that denotes G-d’s essence, is of the language spoken by the most morally bankrupt civilization at the time?

We are taught that every Jewish soul that has ever and will ever come into this world was present at the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. G-d gathered every man, woman, and child of the Jewish faith and said, “I am the L-rd your G-d Who brought you out of the land of Egypt.” If G-d wanted to impress everyone, why didn’t He say, “I am the L-rd your G-d who created heaven and earth”? Isn’t that much more impressive?

While “G-d Who created heaven and earth” is indeed impressive, it has very little to do with each of us on a personal level. When I hear “G-d Who took the Jewish people out of Egypt,” that’s personal; that’s about me.

It is especially personal when considering the teaching of the Mishnah that, “In every generation a person is obligated to regard himself as if he had come out of Egypt.” The Hebrew word for Egypt – “Mitzrayim” – also means boundaries and limitations. We all have our own constraints, things that hold us back, box us in, chain us down. These limitations can be externally imposed or selfcreated.

But, G-d promises us: “I took you out of Egypt once; I can also take you out of your own Egypt.” We are connected to the One G-d - Anochi - and we can do anything we set our minds to; there’s nothing we cannot accomplish.

The Talmud recounts a fascinating dialogue between G-d, Moses, and the angels when Moses ascended Mount Sinai to heaven to receive the Torah.

The ministering angels protested to G-d, saying, “This beautiful, concealed thing [Torah] You desire to give to one of flesh and blood?! You are giving it to a human being?!”

G-d turned to Moses and said, “You answer them.”

Moses was terrified! “Are You kidding? They’re going to breathe on me and consume me with their fiery breath!”

G-d replied, “Don’t worry about it. Grab ahold of My throne of glory and it will protect you. But I want you to respond to the angels.”

And so Moses responded, “The Torah states, ‘I am the L-rd your G-d Who brought you out of the land of Egypt.’ Angels, did you ever live in Egypt? Were you slaves to Pharaoh? You were not. So, what do you need the Torah for?”

Moses continued, “The second commandment says, ‘Do not have any other gods before Me.’ Do you live amongst nations of the world who worship idols that you would learn from them?

“What else is written in the Torah?” continued Moses, “‘Remember the day of Shabbat to keep it holy.’ Do you work all week that you need to rest on Shabbat? Do you get tired? ‘Do not take G-d’s name in vain?’ Will you, angels, ever be asked to swear in court? Do you engage in business dealings? ‘Honor your father and mother.’ You have no father or mother! ‘Do not murder; do not commit adultery; do not steal.’ Do angels ever become jealous? Do angels have an evil inclination?

“The Torah is not for you,” concluded Moses.

With that, the angels conceded, praised Moses, and even presented him with gifts.

Clearly, not only is Torah also for imperfect people, it is primarily for those of us who struggle, who are tempted, and who may sometimes fall short.

The Rebbe explained that in Moses’ first words to the angels he stressed the Anochi, the Egyptian word. “I - Anochi

The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Sivan 5784 - am G-d Who took you out of the land of Egypt.”

G-d was telling the Jewish people, “I remember you in Egypt. I know what it is to be human. I know what it means to have temptations, to face trials and tribulations. I know what it is to feel boxed in, limited. Anochi! I’m not using Lashon Hakodesh, the Hebrew tongue, where everything is rosy and holy and perfect. I am using an Egyptian word. I was with you in Egypt, and I am with you now! I created the evil inclination, and I created Torah as its antidote. This Torah I am giving you will arm you with the ability to transcend your limitations and overcome your personal difficulties.”

As we read the Ten Commandments, it’s crucial to internalize that they encompass the entire Torah, which serves as a blueprint for life.

One might question the relevance of Torah today, asking, “Why are you wasting your time with that?” In truth, however, Torah is the only thing that remains relevant, both today and always. Everything else is transient.

Imagine a doctor using 19th-century medicine or a judge applying outdated laws in a modern courtroom. A computer from a decade ago is considered a dinosaur. Science, technology, the “conventional wisdom” … everything evolves, but Torah remains unchanged; it is eternal.

And Torah is the best prescription for a happy life. When you come home from a Torah class and share what you learned with your spouse, friends, or children, everyone around you will be uplifted.

Is it always easy to adhere to the Torah? Certainly not. Take the 10th commandment, which states, “Do not covet.” What should you not covet? “Your neighbor’s house, wife, servant, ox, donkey, and everything your neighbor has.”

How can we truly observe this commandment? What if my neighbor has a nice car? What if he has a Maserati?! I wish I had a Maserati!

Here’s something I heard many years ago and have shared often: The final words of the Ten Commandments are “[Do not covet…] everything your neighbor has.”

Having enumerated house, spouse, servants, and animals, what does the Torah add by saying, “and everything your neighbor has?” What else is left?

The answer lies in a beautiful teaching, a lesson we would all do well to bear in mind.

People constantly feel pressured to “keep up with the Joneses” (or the Schwartzes, or the Cohens). We tend to think that the other guy has it all and the grass is greener on the other side.

But before bemoaning the fact that you don’t have what your neighbor has, it’s important to understand that you don’t know the whole story. You know the car and the house, but you don’t know the troubles. You have no idea what goes on behind closed doors - one’s relationship with their spouse, one’s relationship with their children, the audit or the investigation one is dealing with. You have no idea of the “tzuris” - the troubles - your neighbor may be experiencing, G-d forbid.

So before you say, “Why can’t I be like the other guy?” think about something my mother, Rebbetzin Miriam Gordon, of blessed memory, would always say, echoing what Jewish mothers and grandmothers have been saying for generations: “Everyone thinks the neighbors have it made, but if every family’s ‘package’ was hung out in public and G-d ordered that we each pick one, we would all run to pick our own. After seeing what the neighbor has to deal with, we change our minds! I don’t need his fancy car and his troubles.”

The truth is we’d rather not have “everything our neighbor has.”

With that in mind, we can return to the first words of the Ten Commandments, Anochi, the knowledge that G-d gave the Ten Commandments to human beings fresh out of Egypt. Each day, we must tap into our Divine connection to transcend our limitations and achieve freedom from our personal exile. Empowered by the eternal Torah, may we continually ascend higher in our partnership with G-d, utilizing our talents to make His world a better place. May we truly merit to see a world of perfection, with the coming of our righteous Moshiach, may it happen speedily in our days! Amen.

SCAN QR CODE FOR TEHILLIM - PSALMS FOR OUR BROTHERS & SISTERS IN ISRAEL FOR THE IMMEDIATE RELEASE OF THE HOSTAGES FOR THE SAFETY OF THE SOLDIERS

Many female converts to Judaism choose the name Ruth, and for good reason! Ruth, whose story is told in the Book of Ruth, is celebrated as a sincere convert who embraced Judaism with all her heart, voluntarily leaving behind the comforts of her idolatrous background to follow the Torah and the G-d of Israel.

Although not specified in scripture, tradition tells us that Ruth was a descendant of Eglon, king of Moab. She and her sister Orpah married the two sons of Elimelech, a wealthy Jewish man who had relocated from Bethlehem to Moab due to the famine that was ravaging the Holy Land. In time, Elimelech died, and his sons died as well, leaving two young widows.

Ruth and Orpah were very attached to Naomi, whose name means “sweet.” Upon hearing that the famine had subsided, Naomi decided to return to her people. Originally both daughters-in-law accompanied Naomi, but she entreated them to remain with their people, where they would be comfortable and cared for. Orpah turned back, but Ruth insisted on following.

At the end of a tearful conversation, Ruth famously told Naomi:

Wherever you go, I will go

And wherever you lodge, I will lodge

Your people shall be my people

And your G-d my G-d.

Where you die, I will die

And there I will be buried.

According to the sages, she was not just pledging her loyalty to the woman she loved and admired, but also accepting upon herself to keep the Torah, even the most difficult parts. This provided a template for Jewish courts to follow in the future, making sure that prospective converts are well aware of the challenges of Jewish observance.

Wishing to support her mother-in-law, Ruth went out to the fields to gather isolated stalks and forgotten sheaves of grain that the harvesters were obligated to leave behind by Torah law.

Boaz, leader of the Jewish nation and a relative of Naomi, noticed how Ruth would sit down before picking grain, so as not to expose herself, and that she never would take bunches of three stalks, which by right belonged to the owner of the field (him) and not the poor (her). Impressed, he inquired about her and was told that she was the former daughter-in-law of Naomi.

Boaz generously invited Ruth to pick grain in his field and to eat and drink along with his staff (who were instructed to be sure to leave grain for her to “discover”), which she continued to do until the harvest had finished.

When it came time to winnow the grain, Naomi instructed Ruth to surprise Boaz while he slept in the field, dressed in her finest and freshly bathed. When he awoke, she told him who she was and asked him to marry her and also buy a field that belonged to Naomi’s family. As a cousin of her late husband, it was his duty to both marry Ruth and “redeem” the properties.

Boaz readily agreed but told Ruth that there was another, closer relative, who would take first priority. Only after the other refused, could Boaz do so himself.

Ruth and Boaz married and were blessed with a son, Oved, whose doting grandmother, Naomi, was very involved in raising him. Oved was the father of Yishai and grandfather of the great King David.

The Book of Ruth could have just as easily been called the Book of Boaz. After all, he was the leader of the Jewish people at the time and a direct descendant of the royal clan of Judah. Yet it is known as the Book of Ruth. The Rebbe points out that this underlines the central place of the Jewish woman, who sets the tone for future generations and paves the way for the future Redemption, which will come about through a descendant of Ruth.

Continued on bottom of next page

I was feeling great before she walked into the room. She came in, our eyes met, and my joie de vivre started to deflate. She’d never harmed me; in fact, we had a cordial relationship. But she had something that I didn’t have. Compared to her, I felt diminished.

Competition - wouldn’t it be nice to outgrow it! In kindergarten, it’s understandable; in high school, inevitable; but as an adult, it’s so . . . passé. I wish we could leave it behind with our senior sweatshirts and loose-leaf folders. Yet it lingers into adulthood. The people we tend to like are those who validate our lifestyles and tickle our egos. Other people, we’d rather not be around. Not because they’ve done anything wrong, not at all. It’s just that we have very little in common - or, even worse, we feel threatened by their presence.

G-d says in the Torah, “Love your fellow as [you love] yourself.” That can’t mean everyone, can it? If we appreciate our fellow, we can probably love him. But if we don’t appreciate him, what’s to love? Didn’t G-d set the benchmark a bit too high with this commandment?

G-d can expect us to be nice to everyone. That’s an attainable goal. Indeed, many commentaries concede that this commandment is written euphemistically, and a more realistic interpretation of this verse would be, “Act in a loving way toward your fellow.” But if that’s what G-d meant to say, then why not say that to begin with? There are many other mitzvahs that require us to treat people with respect, regardless of our personal relationship with them. But this mitzvah doesn’t tell us what to do - it tells us how to feel. Can you tell someone to feel love?

10 FACTS ABOUT RUTH Continued from previous page

10. We Read Her Story On Shavuot

On Shavuot, the story of Ruth is read from the Book of Ruth. Some read it as part of Tikun Leil Shavuot, the all-night learning session on the 1st night of the holiday, while others read it as part of Morning Services on the second day. Why on Shavuot?

1. Shavuot is the birthday and yahrzeit (anniversary of passing) of King David, Ruth’s great-grandson.

2. The scenes of harvesting in the book of Ruth are appropriate for Shavuot, which is the Festival of Harvest.

3. Ruth was a sincere convert who embraced Judaism with all her heart. On Shavuot, all Jews were converts - having accepted the Torah and all of its precepts.

The last part makes it even more challenging: “Love your fellow as yourself.” A more moderate love should suffice. But to love others like we love ourselves? To look out for their best interests like we look out for our own? That type of affection could be reserved for a sister or best friend, but not for everyone.

Maybe this mitzvah is speaking to someone more spiritually attuned than your average Jew. For the rest of us, perhaps we should focus on the other 612 mitzvahs first. The problem is that this is apparently a really important one. Here is a case in point: One of the greatest sages of all times, Hillel the Elder, was challenged by a potential convert who said, “Teach me the entire Torah on one foot.” (In other words, “What’s the abridged version of the Torah?”) Hillel responded unequivocally that the mitzvah to love one’s fellow is essentially the entire Torah, and everything else is commentary to that mitzvah. But how is Shabbat a commentary to love? How is eating kosher predicated on love? What if you’re meticulous about the laws of Passover, but there are a lot of Jews you just don’t like?

The Baal Shem Tov cherished the mitzvah of ahavat Yisroel, love for one’s fellow Jews. In fact, he taught his students that appreciating other people is an objective indicator of how well one has internalized chassidic teachings. The Baal Shem Tov cultivated a following of spiritually vibrant people. They meditated, prayed, and sang soulful melodies. They viewed materialism as a means to an end, and spirituality as the central focus. And love was their litmus test of spiritual growth. Without authentic appre-

ciation of others, their soulful meditation was all hype.

The first Chabad rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, expounded upon many of the Baal Shem Tov’s philosophical tenets in his groundbreaking work, the Tanya. In the thirty-second chapter, he discusses Hillel’s reasoning for placing love at the center of our religious paradigm. And it’s not by coincidence that this topic is discussed in Chapter 32. The number 32 corresponds to the Hebrew letters lamed and bet, which together spell the word lev, “heart” - and loving others is at the heart of Chassidism. Without the heart, all of the intellectual theories are just theories. You can stand on your soapbox and preach Kabbalah all day long, but if you still get irritated by other people, then you’re not quite there yet.

But how do we it? How do we appreciate people that we don’t appreciate? Rabbi Schneur Zalman not only advocates the importance of this mitzvah, but guides us through it.

It all begins with self-love, authentic self-love - an appreciation for the breath of G-d inside us. This doesn’t mean loving any particular attribute or talent. That self-love is dangerously tenuous. Today, we’re stars; tomorrow . . . not so much. A truer self-value comes from the knowledge that G-d created us and invested a G-dly soul inside of us. We’re valuable because G-d gave us a mission.

And that’s really the goal of all of Jewish practice. To empower the soul and to give it precedence. Whenever we do a mitzvah, especially if it’s an inconvenient one, we’ve proven that our priority is the wellbeing of the soul.

And which mitzvah most highlights the centrality of the soul? Loving a fellow Jew - for no other reason aside from the fact that he is a Jew. As individuals, we may have little in common. Maybe she’s not your type, or he’s in another social group. But as Jews, we feel a commonality that transcends our differences. The appreciation that we feel toward another is an objective indicator of how far our spiritual development has taken us.

That’s not to say that we become blind to people’s flaws. We notice them, but they don’t alienate us - just like family members who disagree, but at the end of the day they’re still family. When someone else criticizes our family we take personal offense. And when our siblings are successful, we celebrate with them rather than become envious of them.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman explains that our souls are like siblings. We share a soul root, a father - G-d. We have so much in common with each other. Your success is my success, too, because we’re part of the same family.

It takes a lifetime of concentrated focus to truly master

this mitzvah. So, anytime we don’t feel our commonality, or we feel threatened by another’s success, we’re in good company. At its root, competition is an objective indicator that we don’t love ourselves deeply enough. Yes, I value my individuality, but that’s something that I can’t share with you. Not only that, my unique gifts and assets are threatened by yours. When we appreciate others naturally as common members of the Jewish tribe, we’ve proven that we value our soul more than our individuality.

I once asked a friend how she and her siblings got along so well. She shared the following story: “I remember as a teen going shopping with my mother and my sister. My sister was trying on a dress, and we both watched her reflection as she moved before the giant mirror. When she slipped back into her fitting room, I said to my mother, ‘She is so beautiful and thin!’ My mother responded with a smile, ‘Aren’t you pleased for her?’”

Like this Jewish mother, G-d delights in seeing His children getting along and enjoying each other’s success. The Tanya explains that when we get along, G-d is so pleased that he overlooks our personal imperfections. Unity creates a powerful magnetism that instinctively attracts G-d’s blessing.

In the summer of 2022, one of our sons was going to an overnight camp in Canada via New York City. We had plans to drive him there - about an 8-hour trip from Chautauqua, NY, where my husband and I direct the local Chabad center - but had to reschedule when we received an update that luggage drop-off necessitated that we arrive a day earlier.

Since we had a pre-existing obligation until 2 p.m. on the afternoon of our departure, our goal was to be all packed and ready to leave immediately afterward. My husband arrived home and when he noticed that we had a lot of leftover chicken, he suggested that we make chicken wraps for everyone to eat on the way.

After a quick poll, I saw there was no interest; everyone was already set with their favored packed food. (I also noted that one of my sons was remaining at home and would figure out what to do with the chicken.) Still, for some inexplicable reason, my husband, the one who was most concerned that we leave right away, decided that he really wanted to make those chicken wraps and was certain that later the children would appreciate them. I was incredulous as I watched him carefully making and proudly putting each one neatly in a plastic container. He did a great job, but now we were almost an hour behind schedule.

our minds! We weren’t late at all. Rather, our timing turned out to be perfect; we were absolutely meant to travel a day earlier, an hour later, and approach the exit where we could help a fellow Jew!

We found the woman, and I was able to drive her to the closest city with a proper hospital, where she could get appropriate care and evaluation. I stayed with her for a few hours until her family arrived from Cleveland.

As her family pulled into the hospital parking lot, my husband greeted them and asked them if they had something to eat. Hospital waits are unpredictable, and there would be a return trip for them ahead with little chance of finding kosher food. The family was in such a rush to get to the hospital that food wasn’t a priority. They figured they would just make do with whatever kosher items they could buy at a local gas station or grocery.

My husband went back to our car to get them food, and, of course, beaming with pleasure, gave them the chicken wraps. To me, those wraps had G-d’s fingerprints! The chicken wraps didn’t just affect our timing, so that we would be just seven minutes away from the site of the crash, but also provided nourishment and comfort.

I was incredulous as I watched my husband carefully making and proudly putting each chicken wrap neatly in a plastic container. He did a great job, but now we were almost an hour behind schedule.

A few days later, we were back in Chautauqua hosting a Friday-night Shabbat meal for a large group. The Torah portion of the week was MatotMassei, recounting the journeys the Jews made in the desert during their 40 years of wandering before entering the Land of Israel. With a Torah message about journeys and the purpose of each encampment, we thought our story of Divine Providence was a perfect example and excitedly shared our experience.

As we got into the car, my husband asked if I could drive as he felt exhausted. After driving an hour or so, his phone rang. Someone we didn’t know was calling us and asking how far we were from Cuba, N.Y. The caller said he had searched to find the nearest Chabad and Chautauqua popped up.

My husband quickly tried searching for Cuba, a small town we had never heard of before. The caller had a sister who had just been in a car accident on the highway near Cuba, and he was looking for someone to help her.

To our amazement, Cuba was on our way; in fact, it was the very next exit - seven minutes away! This just blew

The next morning, a woman came over to me, visibly moved and full of gratitude that my husband shared our story at the Shabbat meal because it meant so much to her family, especially her daughter. It so happened that the previous Sunday, she and her husband were driving to visit their nine-year-old daughter at camp on visiting day. It was the girl’s first experience at an overnight camp.

Unfortunately, the parents had a flat tire that delayed them for three or four hours. Their daughter watched and waited as her bunkmates went off with their parents. They had promised her that they would visit, but hours passed and they weren’t showing up. By the time they arrived, she was very emotional, upset and hurt. Even when camp ended and she was back home, it remained a sore subject that lingered in the air.

After having heard the story told by my husband at the Shabbat meal the night before, the girl told her mother, “Now I know why you came late on visiting day!” She

went on to explain to her mother that her parents’ delay was part of G-d’s plan for her to help another person.

“You see, there was another girl in my bunk whose parents couldn’t come. While you were fixing your tire, it was just the two of us, but we had each other to play with. G-d wanted my friend not to be alone and the only one without parents or visitors the whole day. For all those hours of waiting, we played together.”

She recognized the bigger picture with her important role, and her resentment and hurt feelings were gone. Her mother was so proud and inspired by her daughter’s perceptive and introspective reaction, and so relieved that her daughter processed this all in a manner that calmed her

NMLS #46832

emotionally.

These were the events and details I felt so privileged to witness and be a part of. It seems like an “ordinary story” (no splitting of the sea or amazing phenomena), yet upon scrutiny, Divine Supervision is so evident - every piece masterfully orchestrated with precision.

Justin Smith Vice President Senior Branch Manager

Justin Smith Vice President Senior Branch Manager

585 442 7014 585 461 4939 FAX Jesmith@mtb.com

Brighton Branch 1627 Monroe Avenue Rochester, NY 14618

In honor of Pesach Sheni 14 Iyar - May 22

by Elisha GreenbaumYou missed the flight. You forgot to file before the deadline. You mislaid her number. You downloaded a virus. You thought your anniversary was next week. You left your keys in the car. You forgot to hang up before announcing what you really think about him. You blew it!

Someone else got the job. The earlier bird got your worm. She said “Yes” to the other guy. Your childhood photos are plastered all over cyberspace. Your credit rating is a mess. You snoozed, you lost.

Not every error is recoverable, some mistakes are forever. It’s an unfortunate consequence of existence, that every blunder, blown chance and missed opportunity is recorded in life’s ledger with indelible ink. You can try to forget, you can lie and deny, but you’re the one who messed up and you’ll forever wear the consequences.

There was a group of Jews approached Moses with a problem. They’d been ritually impure on Pesach and had missed out on offering the Paschal sacrifice; was there anything Moses could suggest?

G-d told Moses to give them a second chance. One month to the day after Pesach we celebrate Pesach Sheni

when all those who’ve been missing or unable to observe the festival the first time around get a makeup opportunity. Pesach Sheni has become a sort of holiday celebrating life’s second chance. In the words of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, and elaborated on many times by the Rebbe, Es iz nitoh kein farfalen - it’s never too late. You can always make good on the mistakes of the past. G d is always willing and waiting for us to express sincere regret and be welcomed back into the fold.

But is that really true? Can every mistake really be rectified? I don’t think so. You cannot turn back time and Humpty Dumpty couldn’t be put back together again. Some mistakes are permanent; not every stain comes out in the wash and not every broken relationship can be repaired. Why should I believe that I can always repair the past when the evidence of my own eyes proves the opposite?

Obviously the explanation of es iz nitoh kein farfalen must be more sophisticated than just the specious claim that “everything can be fixed.” Not everything can be fixed, but everything can be amended. That first Pesach is gone forever, dead and buried in the mists of time, but your new time to shine is now. It’s a new month and a new you. You may not be able to recover the past, but your future actions can leave you sitting pretty; perhaps even better off than you would have been had you never gone astray in the first place.

The pain you caused in your relationships was real, but, by your committing to start again and do everything you possibly can to change, you have the opportunity to build a whole new relationship, founded on bedrock of shared commitment and new growth.

G-d never promised that we won’t fall off, but he will help us climb back on again. The past is my signpost to the future and the lessons I’ve learned from my earlier stumbles will protect me as I search for my new path through life. All it takes is resolution, courage and a lot of really hard work.

We all make mistakes and we all have regrets. The challenge is not to dwell on the sins of the past but seek a way forward for the future. It is never too late to start again. There is always a chance to redeem oneself. By starting over and committing to improve, we encounter a whole new world of opportunity and will be welcomed and comforted by G-d on our journey to the future.

Editor’s Note: Although by the time you are reading this article the Holiday of Pesach Sheni has already occurredit is never too late to learn about a Holiday that has “it’s never too late” as its theme!

In honor of the Rebbe’s 30th Yahrzeit on 3 Tammuz (July 9) we present the following article written by the late Rabbi Sacks shortly after the Rebbe’s passing

A great leader has died and the Jewish world has become a smaller place. History will chart the achievements of the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. My own tribute is simple. This was a man who changed the religious landscape of Jewish life.

We first met in 1968. I was an undergraduate, visiting American Jewry to seek out its intellectual leaders. They were impressive. But my encounter with the Rebbe was unique. In every other case, I asked questions and received answers. The Lubavitcher Rebbe alone turned the interview around and began asking me questions. What was I doing for Jewish life at the University of Cambridge? What was I doing to promote Jewish identity among my fellow students?

The challenge was personal and unmistakable. I then realized that what was remarkable about the Rebbe was the exact opposite of what was usually attributed to him. This was not a man who was interested in creating followers. Instead, this was a man who was passionate about creating leaders.

He himself was a leader on a heroic scale. Chosen to succeed his late father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, as head of Lubavitch in 1950, he set about reconstructing the movement in the inhospitable climate of secular America. At that time it was widely believed that Orthodoxy had no future in the United States. No one had yet found a way to make traditional Judaism a living presence in an America called the treifa medina.

Like all classic rabbinic leaders, the Rebbe began with education, creating a network of schools and yeshivot. Then he took the decision that was to change the face of Lubavitch and ultimately the Jewish world. He sent his followers out to places and communities which had never known a Chassidic presence. He began with university campuses. Already, in the early 1950’s, Lubavitchers could be found working with Jewish students, telling Chassidic stories, singing songs and introducing them to the hitherto remote world of Jewish mysticism.

It was an extraordinary move, nothing less than the reinvention of the early days of the Chassidic movement when, in the 18th century, followers of the Baal Shem Tov

had traveled from village to village taking with them the message of piety and faith.

Chassidism had proved to be the most effective ways of protecting Judaism against the inroads of secularization. But it was limited in its impact to Eastern Europe. Nothing was less likely than that a strategy from the old world could succeed in the new. But it did. Drawn by its warmth, intrigued by its depth, hitherto assimilated Jews were attracted to Lubavitch and, on meeting the Rebbe, became his disciples.

The second decision was even more remarkable. Though the faith that drove the Rebbe was traditional, the environment to which it was addressed was not. Earlier and more profoundly than any other Jewish leader, he realized that modern communications were transforming the world into a global village.

Religious leadership could now be exercised on a scale impossible before. The Rebbe began sending emissaries throughout the Jewish world, most notably and covertly in Russia. The movement was unified through his regular addresses, communicated through a series of mitzvah campaigns. Few international organizations can have been more tightly led by a single individual on the most slender resources.

Continued on page 33

I want to share with you a snapshot of what has been happening to our community of students - a community to which my husband and I have dedicated the past 23 years of our lives.

The Rohr Chabad Center serves the Jewish students at the University of Chicago, known for its rigorous academics and particularly for its economics department.

For two decades we have cared for the students’ emotional, social, and spiritual needs - as well as providing them with a comfortable home away from home.

We have friends and family who serve as Chabad emissaries in remote and developing countries, and we marvel at their bravery. We thought we had it easy, surrounded by the gleaming ivory towers of academia.

But today, as we look around the once-friendly neighborhood where we raised our children - both our biological children and the many students for whom we’ve become a second set of parents - the place is unrecognizable.

People shout, scream, and curse Israel, Jews, and America, the land that provided them the freedom of expression they’re glibly exploiting. A place of learning and discovery has dissolved into tension and conflict.

Our work began the moment the news broke on Simchat Torah morning that something was amiss. Days later, a student, Yair, came to our Chabad House with a heavy heart, having decided to leave school and return to Israel to fight. I was struck by the gravity of his decision and felt a mother’s instinct to offer him a blessing for safety and success. Watching him leave, knowing the risks he was taking, filled me with a sense of awe and fear.

ages, starting with King David during his tribulations.

The students have been channeling their emotions into positive action, committing to mitzvahs and living more Jewishly.

One grad student, told me she’d been in a committed relationship with a non-Jewish man and looked forward to marrying him. After the attacks, it became clear to them both that the gulf between them was too great. There was no way for him to understand how deeply she connected to people in a country halfway across the globe. She’s now committed to only marrying a Jew.

Of course there is the light at the end of the tunnel - but in our interactions with Jewish college students we need to reveal and share the light that is also in the tunnel itself.

There’s Lily, who one day came to Chabad asking for Shabbat candles. She felt that lighting candles was the one mitzvah she could do for Israel. Later, she sent me a photo of her Shabbat table in New York, complete with challah and candles. Her parents, Russian Jews without a strong Jewish upbringing, had joined her in embracing the beauty of Shabbat. Lily now comes to our Shabbat dinners almost every week. These moments of connection and inspiration are what sustain us through the most difficult times.

We worked relentlessly to support our students and the wider community in the following weeks. Students came to us from every corner, their souls seeking light amidst the darkness. We distributed mezuzahs and stood on campus - even surrounded by anti-Israel slurs and comments - putting tefillin on the young men, encouraging women to light Shabbat candles, and providing comfort to those grappling with hate and fear on campus.

We even invested in beautifully crafted books of Psalms with English translation, gifting them to students and explaining how these sacred psalms have served as a wellspring of inspiration for the Jewish people through the

We did everything possible to shield our young children from the anti-Semitic shouts and slurs they should never have had to witness. It was hard to explain to their teachers what they were seeing and what they were holding in their hearts each day. Just the other week, during a walk around the neighborhood, they counted over 80 anti-Israel signs and we hadn’t even walked onto the actual campus grounds.

One day, things on campus were especially tense. A loud and aggressive anti-Israel rally was taking place, and a student came rushing into Chabad, crying uncontrollably. I embraced her and held her close as she sobbed. She didn’t need words - just the presence of someone who cared. Later, I learned that a visiting mother had taken a picture of me holding this young woman, her tears soaking my shoulder. She sent me the photo, writing, “I took this so

that you would remember, and I could show my friends what a rebbetzin is for during challenging times.”

In such moments, the Rebbe’s teachings have always guided me. I draw strength from his words, whether in times of joy or deep despair.

Preparing for over 250 people for both Seders seemed daunting, but the joy of watching Jewish souls shine made every effort worthwhile. More than ever, students came to us asking where they could find something to eat during Passover.

There were days when we felt like there were two wars, one in Israel and one on college campuses around the country. Unfortunately, this campus war is still strong and frightening to the young Jewish students.

We woke up on the last day of Passover to a Gaza encampment on our quad. It was worse than you can imagine and more disgusting than you can envision. I ran with my son onto the quad to support the students, hug the girls who were crying, and just be a familiar face. We grabbed some kippahs and encouraged the boys to put them on. One young man whom I had never seen before came up to me and asked for a kippah. “I never wear a kippah,” he said, “it’s not my thing, but today I want to. I want to show them that I am a proud Jew.

Last Friday, things devolved to about the worst I had seen. There were hundreds of students on the quad, and things had erupted terribly, both sides were facing off. It was scary and appalling and I honestly could not believe what I was seeing with my own eyes. I will have these horrific images in my head for a long time. We had our sons and interns setting up emergency tefillin stations, blaring Jewish music over their speakers, which was hard to hear with all the shouting.