THE CHABAD TIMES

A Publication of Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester

A Publication of Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester

Shalom Uverachah! As Chanukah draws near and we run down our list of things to do: Polish the Menorah, buy the olive oil and candles, concoct new exotic latke recipes, find last year’s Dreidels . . .

Hmm, we muse, the search for the Dreidels would probably be futile, and, anyway, is the Dreidel such an integral part of Chanukah? After all, the Menorah certainly is important, even latkes (in Israel they eat donuts) fried in oil commemorate the miracle of the oil - but Dreidel?!

Yet, if it was merely an innocuous spinning toy, it would not have survived this long, and certainly not in our era of high priced high tech toys. In fact, the Dreidel really tells us a very moving story of Jewish heroism and courage:

Back in those days of Greek occupation of the Holy Land, the Jews were threatened by their foreign conquerors. However, the major threat was not a physical one, but rather of a spiritual nature. The intention of the Greeks was not to kill Jews but rather to force them to assimilate into the Greek way of life. The conquerors knew (as did later the Romans and the Stalinist Communists) that the key to the Jewish spirit is the Torah and its transmission to the next generation - the children. Thus, the teaching of Torah to children was severely prohibited.

proached, the children quickly hid their scrolls, took out a spinning toy and pretended to play until the danger passed. The toy? Of course, it was the Dreidel.

Oh, Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel, you remind us of the heroism of those children of old and you reawaken us to our commitment to the children of today. They have the right to be properly exposed to the beauty of their heritage and study Torah - and we have the obligation to provide them with that opportunity.

The Greeks, however, did not reckon with the strength and resilience of the Jewish spirit. Jewish children secretly met with their teachers in the caves outside the city and continued to study Torah. Whenever a Greek garrison ap-

Kessler Family

Chabad Center 1037 Winton Rd. S. Rochester NY 14618 585-271-0330

chabadrochester.com

Rabbi Nechemia Vogel

Rabbi Dovid & Chany Mochkin

Our children don’t have to meet in caves to study and the Dreidel does not have to serve a camouflage role. But this Chanukah, G-d willing, we will spin the Dreidel again and realize that if back then they could maintain Jewish education under those conditions, then in our free society we can certainly give our children what is rightfully theirs. As our Sages point out, the name Chanukah is related to the Hebrew word, Chinuch, Education.

So, Chanukah is really not about gift giving per se; rather, it’s about Jewishly educating our children and our encouragement of their efforts by giving them Chanukah Gelt and gifts. This is what the Maccabees fought for with such dedication and courage - and this is the continuing Story of Chanukah. So this Holiday of Chanukah let us spin the Dreidel with the youth of today and tell them about their heroic ancestors - and then let us follow through on the message of the Dreidel. Wishing you all a Bright and Inspiring Chanukah!

Chabad Lubavitch of Rochester NY

Chabad Of Pittsford 21 Lincoln Ave. Pittsford NY 14534 585-340-7545

jewishpittsford.com

Rabbi Yitzi & Rishi Hein

Chabad Young Professionals 18 Buckingham St. Rochester NY 14607 585-350-6634 yjprochester.com

Rabbi Moshe & Chayi Vogel

Rohr Chabad House @ U of R 955 Genesee St. Rochester NY 14611 585-503-9224 urchabad.org

Rabbi Asher & Devorah Leah Yaras

Chabad House @ R.I.T. 3018 East River Rd. Rochester NY 14623 347-546-3860

chabadrit.com

Rabbi Yossi & Leah Cohen

The Chanukah Lights which are kindled in the darkness of night recall to our minds memories of the past: the war that the Hasmoneans waged against huge Syrian armies, their victory, the dedication of the Temple, the rekindling of the Menorah, the small quantity of oil that lasted for many days, and so on.

Let’s imagine ourselves as members of the small band of Hasmoneans in those days. We are under the domination of a powerful Syrian king; many of our brethren have left us and accepted the idolatry and way of life of the enemy. But our leaders, the Hasmoneans, do not commence action by comparing numbers and weapons, and weighing our chances of victory. The Holy Temple has been invaded by a cruel enemy. The Torah and our faith are in grave danger. The enemy has trampled upon everything holy to us and is trying to force us to accept his way of life which is that of idol

worship, injustice, and similar traits altogether foreign to us. There is but one thing for us to do - to adhere all the more closely to our religion and its precepts, and to fight against the enemy with everything we have.

And wonder of wonder! The huge Syrian armies are beaten, the vast Syrian Empire is defeated, our victory is complete.

This chapter of our history has repeated itself frequently. We, as Jews, have always been outnumbered; many tyrants attempted to destroy us because of our faith. Sometimes they aimed their poisoned arrows at our bodies, sometimes at our souls, and, sad to say, some of our brethren succumbed to the pressure, turned away from G-d and His Torah and tried to make life easier by accepting the dictates of the conqueror.

In such times of distress we must always be like that faithful band of Hasmoneans, and remember that there is always a drop of ‘pure olive oil’ hidden deep in the heart of every

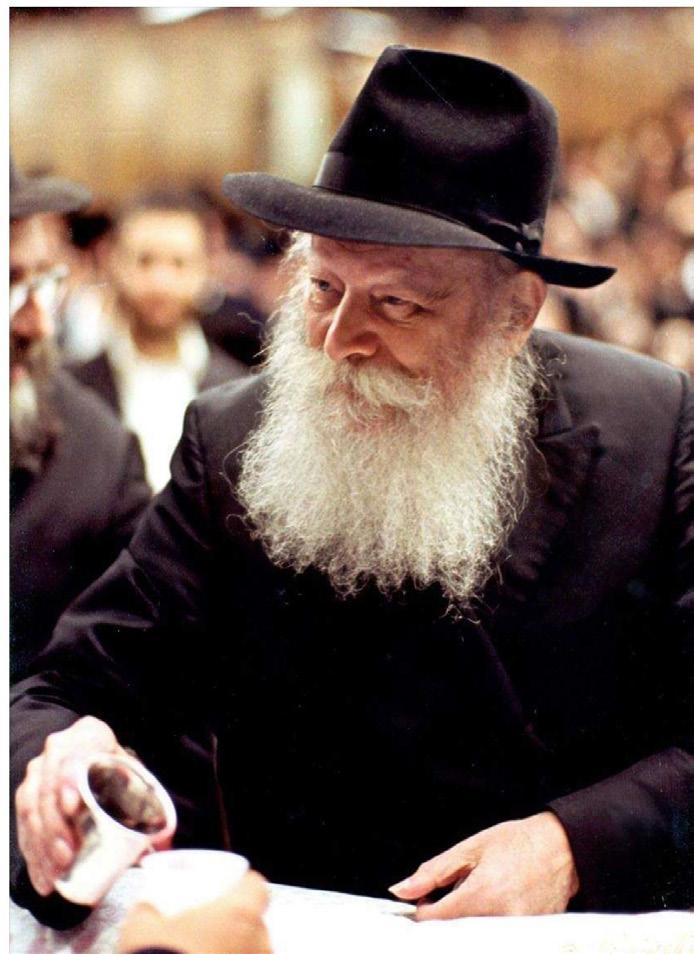

He replied, “A Chassid is like a street-lamp lighter.” In olden days, there was a person in every town who would light the street-lamps with a light he carried at the end of a long pole. On the street-corners, the lamps were there in readiness, waiting to be lit; sometimes, however, the lamps were not as easily accessible. There were lamps in forsaken places, in deserts, or at sea. There had to be someone to light even those lamps, so that they could fulfill their purpose and light up the paths of others.

Jew, which, if kindled, bursts into a big flame. This drop of ‘pure olive oil’ is the ‘Perpetual Light’ that must and will pierce the darkness of our present night, until everyone of us will behold the fulfillment of the prophet’s promise for our ultimate redemption and triumph. And as in the days of the Hasmoneans ‘the wicked will once again be conquered by the righteous, and the arrogant by those who follow G-d’s laws, and our people Israel will have a great salvation.’

dled. Sometimes they are close, nearby; sometimes they are in a desert, or at sea. There must be someone who will forgo his or her own comforts and conveniences, and reach out to light those lamps. This is the function of a true Chassid.

Dovber, of saintly memory, was once asked, “What is a Chassid?”

It is written, “The soul of man is the candle of G-d.” It is also written, “A Mitzvah is a candle, and the Torah is light.” A Chassid is one who puts his personal affairs aside and sets out to light up the souls of Jews with the light of Torah and Mitzvot. Jewish souls are ready and waiting to be kin-

The message is obvious. I will only add that this function is not really limited to Chassidim, but is the function of every Jew. Divine Providence brings Jews to the most unexpected, remote places, in order that they carry out this purpose of lighting up the world.

May G-d grant that each and every one of us be a dedicated ‘street-lamp lighter,’ and fulfill his/her duty with joy and gladness of heart.

This issue of The Chabad Times is lovingly dedicated in memory of Rabbi Zvi Kogan - Zvi ben Alexander HaKohen hy”d, a fellow Chabad Rabbi, 28 years-old, who was recently murdered in Dubai, while serving the Jewish community in the U.A.E. Our hearts go out to his family and wish them strength and comfort.

Dear Zvi, you died heroically fighting these evil haters with your bare hands. We will continue your legacy of serving the Jewish people and spreading light with love and dedication, leading to the day when we will see the fulfillment of the prophecies of the Torah, the day when peace will come to our world - may it be soon.

Until, on the last day, you light only one!”

small light can chase away an entire army of darkness.

Everyone knows that each day of Chanukah you add another flame to your menorah. Well, it wasn’t always that way. Originally, this was a matter of serious debate.

The Jewish sages who lived not long after the Chanukah miracle were divided between the disciples of Shammai (“Beit Shammai”) and the disciples of Hillel (“Beit Hillel”).

Beit Shammai said, “Look, on the first day of Chanukah you’ve got eight days of miracles ahead of you. That’s a lot of potential light. So it makes sense to light eight candles. The second day, there’s only seven days to go, so you should light seven.

But Beit Hillel said, “You don’t have any light until you’ve actually lit a candle. What you think you can do means nothing. It’s what you actually do that counts.”

Both sides had a strong point.

On the one hand, if you’re fighting darkness, you want to start by pulling out all the light you have. Then you’re left just cleaning up the leftovers, so less light is necessary.

On the other hand, in a time of darkness, you usually don’t have a lot of light to fight back with. So you start with what you’ve got, and you discover something amazing - that whereas a vast empire of darkness can’t extinguish a single light, one

Indeed, this debate between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, of potential versus actual, extends throughout the entire Talmud, spilling over into every facet of Jewish law and life. But in the end, the Jewish people decided unanimously to follow the disciples of Hillel. Why?

Because when you do a mitzvah, its light never goes out. It remains with you, protecting you, guiding you, and channeling blessings toward you. So that today you have the light you gained from yesterday. And tomorrow you will have the light from yesterday and today.

Darkness fades and disappears with time, but the light that shines from a mitzvah can only increase.

by Chana Hirschowitz

“What happened?” I asked naively. For the first time, I heard the words “hostages,” “babies,” “a massacre.”

“Are you sure?” I pressed, willing it not to be. It sounded like an echo reminiscent of the rumors Elie Wiesel heard as a child. It was too unbelievable to believe. I didn’t want to believe it. I couldn’t believe it. I still find it hard to believe.

Simchat Torah 5784 will forever be remembered as one of the darkest days in Jewish history. It is a shadow that has pervaded our Jewish consciousness. It has woken us up from our apathy, from our innocence. It has pushed us to reflect, to be more active, more Jewish.

In many ways, this story is very personal to me. It’s a story of my deep personal quest to feel some concrete relief, to find answers, to understand the pain in my soul. Why was I hurting so deeply? I had never met Ariel Bibas, nor a single precious soldier that has fallen in the past year. Yet, I cried at funerals like it was my own family member who had fallen. I needed to understand how and why.

How can you love and miss people you have never laid eyes on?

Intellectually, I’d always known that the Jewish people are one spiritual, interconnected body, but my travels over the past year - in Israel and along “the Hummus Trail,” the Eastern routes that many young Israelis travel after they complete their military service - have shown me just how real, how strong, and how unbreakable our connection is.

In Laos, I meet Raz Barabi, a fearless, strong soldier with the Duvdevan Unit, a traditional, not-typically-observant Jew with a heart of gold. He reminisces, taking us back to the war zone, to the deafening explosions, to the ever-present Angel of Death. “It was one of those moments whose spiritual weight was impossible to ignore,” he tells us. “It revived me, ignited my belief, reminded me why we are here, why we are fighting.”

I know I am about to hear a gem.

“It was Chanukah,” he continues. “We were stationed in a house in Jabalia, in northern Gaza. Soldiers in my unit wanted to light the Chanukah candles, but it was dangerous - the lights could have exposed us. Any movement could have unmasked our hiding spot. But it was Chanukah.

One of the many walls of stickers on the “Hummus Trail,” the Eastern routes that many young Israelis travel after they complete their military service.

“And so, we masked all the windows, huddled in a corner and lit the same candles that have been lit by Jews for thousands of years. We sang the same songs as the Jews did in the barracks, in the shtetl, in all corners of the world in all kinds of dangerous situations. Here we were in Gaza, in a place darker than most, fighting for our people, not only physically, but with the power of the lights.”

I look at Raz and realize he is no longer here; he has been transported to that moment, and his vivid descriptions have taken me with him.

“There was no feeling like it. A simple light, in the deafening darkness. It reminded me why I was fighting; it gave me the strength to push forward.”

A simple story in the most complex of circumstances. It wasn’t even his words that moved me, but his tone. At the moment of lighting the candles, he had an undeniable clarity. He saw the spiritual makeup of this world through the obvious G-dly energy that each of us carries within. It was a moment the likes of which every Jew yearns to experience. A moment that reminds us who we are, why we are fighting and what we stand for.

I’ve just landed in Hoi An, Vietnam, when I overhear Matan Sussman asking a pair of friends he has clearly just met, “Is that a picture of Aloush on your phone case?”

“Yes, he’s our friend from home,” the two friends respond.

“I was with him in Gaza the night that he fell,” says Matan quietly. His new friends are taken aback, somber but curious, and come to sit closer. There is a lot of Hebrew, a lot of army talk, but I sit and watch as two men listen to the events leading up to the death of their childhood friend, Liav Aloush who served in Tzevet 100, the most elite team of the Duvdevan Unit.

I don’t understand all the details, but I gather that there

were terrorists, explosions, and lots of gunfire. “Everything that could have gone wrong, went wrong,” said Matan sorrowfully.

These are young, ordinary people, on vacation in Vietnam, yet the horrors they have witnessed are indescribable. But the conversation doesn’t end there; soon the somber talk transforms into smiles and laughter, as one calls out “Achla Aloush,” slang for “Incredible Aloush,” and they segue into reminiscing about the life he lived, the joys they experienced together in their short lives.

How did they laugh and smile? I wondered. How did they live their ordinary lives after all the pain they had witnessed? What did I even experience in life living in a small, quaint, war-free town in Sydney? What gave me the right to feel the pain too? I wasn’t there; I had never met Aloush.

“I didn’t tell them all the details,” Matan tells me later that Friday night in the Chabad House. It had been twentyfour hours since I had witnessed the encounter and I didn’t sleep well the night before. I dreamt of the war zone, the chaos and the sounds, and of course, the face of Aloush that had been imprinted on my mind from the sticker on the phone case.

Later, I see the two friends of Aloush sitting with Matan, drinking a beer. They had only met 48 hours ago, but they shared a story. They shared Aloush.

Tisha B’Av is almost upon us. We are on the road, cooking last-minute couscous in a parking lot with eggs we picked up at the local market. We pack up and then I remember: Tonight is Shilo’s birthday.

I was first introduced to Shilo Rauchberger through a copper bracelet worn by two of his friends. “What is written on the bracelet?” I asked innocently. “Learn to look at the good and celebrate it,” they explained.

Who was he, and why did he inspire this bracelet, of all things?

When I sat down to write this article, I finally got the courage to call his three best friends, Nadav, Matan, and Beeri, to ask, to know more; for me, for you, to remember those who have sacrificed their lives for us.

The first thing Matan describes is what Shilo was wearing when they first met in ninth grade. “He was wearing one of those camp shirts, like the merch they give you in B’nei Akiva, cut around the neck. He loved those shirts,” he reminisces, “He always wore them.”

I look down at my shirt; there is Hebrew scribbled on the front and on the back. “I love those shirts, too,” I think to myself.

I try to imagine losing my best friend from high school. I shudder.

“How do you do it?” I ask in desperation, like there is some secret formula to overcoming the incessant tragedy that has been suffocating us the past 365 days.

“I have comfort knowing that he fought for Am Yisrael until the very end; that’s the only way Shilo would have done it. He would do anything to protect his soldiers, his people, his land - our land,” says Matan with conviction.

Shilo Rauchberger was born in Eli on Tisha B’Av 2000 to Dudi and Nirit. He was one of seven children. “He always had a smile on his face. This photo is classic Shilo,” he says, as he shows me a photo of young Shiloe.

Shilo was a commander in the Golani Brigade 51 for Yeshivat Hesder, serving on the Southern R&D outpost on the Gaza border. He passed up the opportunity to be an elite officer with the Special Unit Egoz to be able to inspire people from all different parts of Israeli society in the Golani Brigade, not just those in the special units. “That was Shilo,” Matan explains, “he wasn’t authoritarian, yet his soldiers performed better than every other unit. They simply loved and respected him.”

I don’t want to ask about his final day. My usual talkative, curious self has lost the ability to ask such questions. But he doesn’t wait for me to ask. “It was Simchat Torah. Shilo had organized for a rabbi to come and spend the holiday on base. When the sirens went off in the early hours, dressed in one of his well-loved merch t-shirts, he assembled all his soldiers at the safe room in the mess hall. Shilo stood there, holding the door, as a barrage of grenades, bullets, and shouts of Arabic rained down on them. Devoted to his troops until the very end, Shilo stood firmly by the door despite being badly hit by shrapnel. When he couldn’t stand any longer, he lay down, continuing to direct commands to his soldiers to protect the base, until his holy soul left this world. Not a single terror-

8

The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Kislev 5785 ist managed to get past the base into civilian territory. The majority of the southern kibbutzim and moshavim on the Gaza border had been saved. But what a price we paid.”

I’m sitting at a coffee shop in Pai, Thailand, when I overhear a father and his three daughters mentioning that they are from Kibbutz Eilot.

“Kibbutz Eilot?!” I chime in. “I spent every Friday running a Shabbat booth there, for five months,” I babble excitedly.

“With Danielle?” they ask, with equal excitement.

Immediately, they take out a phone and we send Danielle a video. Danielle runs the weekly Friday market in a Kibbutz right outside of Eilat.

How did the Shabbat booth come to be?

“A little before Chanukah we got a call,” recalls Rebbetzin Chanie Klein, Chabad emissary to Eilat and honestly the most incredible woman I have ever met. “The caller explained that Kibbutz Eilot was searching for something more after the trauma of the October 7 Simchat Torah attacks, and asked if Chabad of Eilat would be interested in opening up a stand in their Friday fair.

“I could never have anticipated this,” exclaimed Chanie excitedly. “A secular Kibbutz reaching out for a Shabbat stand in their local Friday fair? It was a modern-day miracle.”

Chanie brought her very own silver candlesticks to place at the center of our booth, and for the next five months we gave out Shabbat candles every Friday by the thousands. On my final Friday, I received a job offer to work at the local kibbutz, free earrings from the stand next to us, and lots of tearful goodbye hugs and kisses.

“Chana, will you come back and bake challah with us?” asked Shira, a soldier I had met only moments earlier at a BBQ at a base in the Golan.

“Sure,” I agreed, without missing a beat. I am Chabad after all.

But I was leaving for Australia in two days. “How about tomorrow?” I heard myself say.

Honestly, I had never felt particularly connected to baking challah. It felt like a chore. But since the attacks, it feels like a lifeline. I need it, I crave it: Women coming together, baking bread, generation after generation. The power of prayer and the mystical energy that is undeniably palpable - there is nothing like it. We have laughed together, we have cried together, I have traveled to bases

all over Israel for it. Not for them - for me. It’s my muchneeded spiritual therapy.

“Wait, do you have an oven on your base?” I asked Shira. I knew the answer would be negative. I had seen the base. It was in a muddy field with no electricity. There wasn’t even a concrete floor there; my shoes had been swallowed by mud. I had to find a solution.

“I have a strange question,” I stuttered on the phone to a random hotel in nearby Moshav Keshet. “Do you by any chance have an oven I can borrow for an hour? I am trying to run a challah bake for soldiers in a base close by.”

“We are closed because of the war,” said the woman on the other line, “but let me send you three numbers of families on the Moshav. I’m sure you can use their home ovens.” Her response was so calm and nonchalant, it was as if I had asked her what her last name was. Obviously, a random Australian girl on the phone can come and use a private oven, in a personal home, no questions asked.

Only in Israel.

Sure enough, one of the people I reached referred me to another family who owned a bigger oven. And so, after completing one of the most memorable challah bakes - in a tent, on an artillery base, in a field in the Golan Heights, in our indigenous homeland - we arrive at Sheri’s house at 10:00 p.m. to drop off trays of challahs to bake in her very roomy oven.

“No problem; I’ll drop it off at the base in the morning,” she tells us.

Now it’s 11:00 p.m., we have a four-hour drive back to the center and I have a flight to Australia the next morning. I carry the holy, dry mud on my shoes, from our homeland, from the base in the Golan, all the way to Australia...

by Chana (Jenny) Weisberg

Viktor Frankl famously wrote that human beings can suffer through any “what” as long as they have a good enough “why.” You can put up with hunger pains, for example, if your hunger means that you will be able to fit into your wedding dress in time for the ceremony a month from today.

For me, the most remarkable aspect of Sarah Nachshon’s very remarkable life is the way in which her “why,” the mission to rebuild the Jewish community of Hebron, has enabled her to keep a smile on her face throughout extreme “whats”.

While I heard her story, I could not help but imagine myself in the situations she described. I imagined myself pregnant, sharing one room with seven children, living without electricity, and carrying twenty-five-liter jerry cans of water long distances in order to fill my baby’s bottle.

I don’t think I would have lasted more than an hour or two. In contrast, Sarah Nachshon’s absolute clarity of purpose and unwavering sense of mission have enabled her to repeatedly sacrifice her own personal needs with love and even enthusiasm. Her rare clarity, together with her tremendous humility, have caused many admirers to refer to her as “a modernday Sarah, our Matriarch.”

Sarah Nachshon grew up in the village of Kfar Chassidim in the north of Israel. Her parents had fled from Poland several months before World War II, and despite their poverty, she has sweet memories of her childhood. “My family lived in a small shack, and we didn’t have any toys or anything else. I had only one dress, and if I wanted to wear another dress I had to trade with one of my friends. But I will tell you something - I had a wonderful childhood. My parents taught me to be happy with what I have, and that is a value that I have worked hard to pass on to my own children as well.”

Growing up, Nachshon also learned from her parents the value of self-sacrifice for the land of Israel. “I remember the stories my parents told us of how they fought against the British in order to establish the State of Israel. My parents taught me that if the Jews want to keep the Land of Israel, then we must fight for the Land of Israel. If we don’t fight for it, they taught me, we may lose it, G-d forbid.”

After the Six Day War in 1967, Nachshon and her hus-

band, the respected Chassidic artist Baruch Nachshon o.b.m., joined a group of idealistic activists determined to reestablish the ancient Jewish community inside newly-liberated Hebron. The Rebbe encouraged them and endowed them with many blessings for their efforts. These activists understood the supreme importance of establishing a Jewish presence in the oldest of the Israel’s four holy cities, where a Jewish community had existed for hundreds of years until the massacre of sixtyseven Jews by local Arabs in 1929. They also understood that maintaining a Jewish community in Hebron would be the only way to guarantee continued Jewish access to the Cave of Machpelah, the burial site of our Matriarchs and Patriarchs and the second holiest site in Judaism which until 1967 had been barred to Jews by the Muslim authorities for over 700 years.

In 1968, the Nachshons and their four young children moved with this group of activists into an Arab-owned hotel inside Hebron. Nachshon recalls, “An army official came to meet with our group, and told us that we were a big pain in his neck. But he told us that because the government feared for our safety, they had reluctantly agreed that a group of seven families and fifteen yeshiva students could stay in Hebron if we would move into an army compound overlooking the city.

But the army underestimated the determination of this small but committed group. Over those three years, not only did the families not move out; thirty more families moved in.

“They assumed that we would not be able to tolerate the terrible conditions for long - living in one room with all of our children, only one kitchen for all of us to share, and with the only bathrooms outside. The army saw us with our little children and thought that within a few weeks we would give up and leave. They thought that our dream to live in Hebron would die right then and there.”

But the army underestimated the determination of this small but committed group. Over those three years, not only did the families not move out; thirty more families moved in. While living in the army compound, Sarah Nachshon gave birth to three more children, and repeatedly risked imprisonment by defying government orders and circumcising her newborn sons at the Cave of Machpelah. When the mohel, the ritual circumciser, performed

The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Kislev 5785 the first circumcision at Machpelah in over 700 years on Nachshon’s son, he wept as he said the blessing over “the covenant of Abraham our father,” in the burial place of the Patriarch himself.

Despite the challenging physical conditions, Nachshon remembers the years she spent at the army compound with much nostalgia. She recalls, “When we were living in the army camp, my sister visited us from her home in Canada at the beginning of one of my pregnancies. She asked me, ‘Sarah, do you mean to tell me that you will spend this whole pregnancy living in a place with an outdoor bathroom?’ I told her, ‘I’ll tell you something! I am happier to live in one room in the Land of Israel than in a palace in Canada!’ Afterwards, when we moved to a larger apartment, my children missed the army compound so much. They were so sad that they could no longer sleep together with all of their siblings in one room.”

In 1971, the city of Kiryat Arba was established outside Hebron in order to provide permanent housing for the families from the army compound as well as the many other families who wanted to join them.

While living in Kiryat Arba, Sarah Nachshon experienced one of the most painful chapters of her life. In 1975, she gave birth to a healthy baby named Avraham Yedidya who suddenly died of crib death when he was only six months old.

The terrible morning that Nachshon found her baby lifeless in his crib, her husband was out of town, and there was no way to reach him. As she made the preparations for the burial all on her own, while she wept and prayed she tried to remind herself that everything G-d does is for a purpose, even if it is hidden from us. At that point she understood that her lost son was meant to play a sad but vital role in the rebuilding of the City of the Patriarchs. “I decided,” she recalls, “that we would bury him in Hebron. Our Avraham Yedidya would be the first Jew buried in the ancient Jewish cemetery of Hebron since the burials of the sixty-seven Jews massacred in 1929.”

Roadblocks and Israeli soldiers who had been given orders to prevent a burial in the ancient cemetery lest it anger the local Arabs, blocked the funeral procession of cars from Kiryat Arba. Sarah Nachshon got out of her car holding her baby wrapped in a sheet. She addressed the soldiers, “Are you looking for me? Are you looking for my baby? My name is Sarah Nachshon. Here is my baby, in my arms. If you won’t let us drive to the cemetery, we will walk.”

As darkness fell, and the mourners got out of their cars and started walking in the direction of the cemetery, senior army officials continued to order the soldiers over their walkie-talkies, “Stop them! Do not let the funeral procession reach the cemetery under any circumstances!”

But the soldiers, unable to turn back this young mother

grieving for her lost child, radioed back their superiors, “If you want to stop this woman, come down here and stop her yourself!” One of the soldiers got out of his command car, and as he wept he begged Sarah Nachshon, “Please, Mrs. Nachshon, it is too far to walk! Please permit me to drive you to the Jewish cemetery.”

Thirty-two years later, tears still come to Sarah Nachshon’s eyes when she remembers the words she said to the hundreds of people who gathered that summer night to bury her son. “I told them, ‘It has been a hard day, but there is something I must tell you. I, Sarah, am holding my dead baby, Avraham, in my arms. And just as Avraham our Father came to Hebron to bury his Sarah, so too I, Sarah, have come here to bury my Abraham. At this moment, I know why G-d gave me this irreplaceable gift for only six months. To reopen the ancient Jewish cemetery

Avraham Yedidya’s grave in the ancient cemetery of Chevron

of Hebron.’”

In the years that have passed since that funeral, Sarah Nachshon has continued her struggle to ensure that the City of the Patriarchs will remain in Jewish hands.

In 1980, she and her children joined a group of fifteen other mothers and thirty children who cut through barbed wire and defied government orders by entering the abandoned Jewish owned Beit Hadassah in Hebron. The army and government had assumed that if they prevented the husbands from entering Beit Hadassah, the women would not be able to make it on their own. But weeks turned into months and not only were the women not leaving – they succeeded in establishing a school within the building, and other programs to keep the children occupied and happy. They lived without electricity, running water, and in substandard conditions, forbidden to leave the building lest the army prevent them from reentering. But they weren’t budging. These women were stronger than anyone could have imagined.

These women were not allowed to meet with their hus-

bands or leave the building. But on Friday nights, when the men were returning home from prayers at the Machpelah Cave, they would stand outside of Beit Hadassah and serenade these heroic women with the traditional Fridaynight song Eishet Chayil, A Woman of Valor.

As a direct result of this group’s tremendous self-sacrifice, the Israeli government at long last agreed to the establishment of a Jewish community within Hebron. Today, the Hebron Jewish community numbers 800 residents, with hundreds more waiting to move in as soon as apartments become available.

To this day, Sarah Nachshon leads groups of women to the Cave of Machpelah, and is active in the struggle to

by Mendy Wolf

The story is told of a group of mountain climbers who had their hearts set on reaching the peak of a very tall mountain. They trained for years, practicing in harsh climates, scaling smaller mountains. One day, they thought they were finally ready. Supplied with essentials and filled with excitement, they set out for the long climb.

After many difficult days, the group finally reached the summit. Their satisfaction was complete - they had achieved their great goal, realizing a dream of years. Suddenly, to their shock, they sighted a young boy sitting comfortably on a rock. Here they had trained for years to scale the

open all of the halls of Machpelah to Jews 365 days a year. She fills her days performing acts of kindness for her family, friends, neighbors, as well as complete strangers. On an average day you will find her babysitting for one of her scores of grandchildren (she knows all of their birthdays by heart), volunteering with the elderly at her local senior’s club, or using her vast knowledge of alternative medicine to treat a sick neighbor. As one friend explained, “It’s easier to make a list of what Sarah Nachshon doesn’t do than what she does do.”

Sarah Nachshon, in other words, is a living example of what it means to live for a “why” that is greater than yourself…

mountain; how had he gotten there?

In response to their questions, the lad stated simply, “I was born here.”

Imagine you were that child, fortunate to be given what others needed to labor arduously to accomplish. How would you feel? Would you be grateful? Would you take it for granted? Would you feel superior to others?

Now stop imagining. You are that boy. Yes, we are each born with unique talents and capabilities which enable us to reach heights that remain out of reach for others. Every one of us is born at the top of some mountain, be it intellect, physical strength, creativity or anything else.

It is easy to feel that we own our achievements. We pride ourselves on a job well done. We consider ourselves deserving of the profits of our labor.

Charity? It’s my money! Gratitude? For what? This is all my work!

In the Torah (Deut. 8:17-18), Moses exhorts us not to fall into that trap of entitlement. When we start thinking, “My strength and the might of my hand made me all this wealth,” we are to remember that our strength was, after all, given to us by G-d.

Yes, we may work hard, and for that we deserve recognition. But let us not forget that we received a head start. We may have cut a great deal, but it was only because we received a “lead.” We were born at the top of a mountain: Our efforts, however laudable, really build upon the talents and capabilities we were given, gratis.

do I place the Menorah?

Many have the custom to place the menorah in a doorway opposite the mezuzah (such is the custom of Chabad Lubavitch) so that the two mitzvot of mezuzah and Chanukah surround the person. Others place it on a windowsill facing a public thoroughfare.

How do I set up the Menorah?

It is preferable to use cotton wicks in olive oil, or paraffin candles, in amounts large enough to burn until half an hour after nightfall. If not, regular candles can be used as well. The candles of a menorah must be of equal height in a straight row. The shamash, the servant candle that kindles the other lights, should stand out from the rest (i.e. higher or lower). The Chanukah lights must burn for at least half an hour each night. Before kindling the lights, make sure that there is enough oil (or if candles are used, that they are big enough) to last half an hour.

Who lights the Menorah?

All members of the family should be present at the kindling of the Chanukah menorah. Children should be encouraged to light their own Menorahs. Students and singles who live in dormitories or their own apartments should kindle menorahs in their own rooms.

How do I light the Menorah?

On the first night of Chanukah one light is kindled on the right side of the menorah, on the following night add a second light to the left of the first and kindle the new light first proceeding from left to right, and so on each night.

On Friday eve the Chanukah lights are kindled before the Shabbat lights (which are lit 18 minutes before sundown). Additional oil or larger candles should be provided for the Chanukah lights ensuring that they will last half an hour after nightfall. •

ON WEEKDAY NIGHTS OF CHANUKAH, AFTER SUNSET, GATHER AROUND TO LIGHT THE MENORAH. SEE SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR SHABBAT. BEGIN BY LIGHTING THE SHAMASH CANDLE AND HOLDING IT IN YOUR RIGHT HAND (OR LEFT HAND IF YOU ARE LEFT-HANDED). WHILE STANDING, RECITE THE APPROPRIATE BLESSINGS BELOW. THEN, LIGHT THE CANDLES, STARTING WITH THE NEWEST CANDLE ON THE LEFT AND CONTINUING TO LIGHT FROM LEFT TO RIGHT.

1. Ba-ruch A-tah Ado-nai E-lo-hei-nu Me-lech ha-olam a-sher ki-de-sha-nu be-mitz-vo-tav ve-tzi-va-nu le-had-lik ner Chanukah.

Blessed are You, Lord our G-d, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us to kindle the Chanukah light.

2. Ba-ruch A-tah Ado-nai E-lo-hei-nu Me-lech ha-olam she-a-sa ni-sim la-avo-te-nu ba-ya-mim ha-hem bi-z'man ha-zeh.

Blessed are You, Lord our G-d, King of the universe, who performed miracles for our forefathers in those days, at this time.

3. On the first night of Chanukah, or on your first time lighting a menorah this year, add the following: Ba-ruch A-tah Ado-nai E-lo-hei-nu Me-lech ha-olam sheheche-ya-nu ve-ki-yi-ma-nu ve-higi-a-nu liz-man ha-zeh.

Blessed are You, Lord our G-d, King of the universe, who has granted us life, sustained us, and enabled us to reach this occasion.

After kindling the lights, the Hanerot Halalu prayer is recited. See our website for full text.

DESIGNED BY G-D THE ORIGINAL MENORAH WAS CARVED OUT OF A SOLID CHUNK OF GOLD.

Then, a thousand years later, the story of Chanukah occurred, and Jews started lighting miniature, less expensive Chanukah menorahs. It seems unlikely that your menorah at home could outshine that seven branched menorah that stood proudly in the Temple in Jerusalem. Yet, surprisingly, according to Chabad teachings, the light of your menorah outshines the Temple’s original menorah in many ways.

We asked our editors to shed some light on what makes your menorah at home so powerful that it wins the “Ultimate Candelabra” title. Here’s what we found:

To start, we find four primary differences between the two menorahs:

1) The number of candles lit in the Temple’s seven branched menorah remains the same daily, while your Chanukah menorah changes and grows from one to two to three until eight.

2) You light your Chanukah menorah when it’s dark outside, specifically after sundown, while the High Priest lit the Temple’s menorah in the sunshine during the day.

3) The golden menorah was kept inside the Temple, forever confined indoors, whereas your Chanukah menorah is lit outdoors, at the front door facing the street, or in a window.

4) The Temple’s menorah glowed in a time of prosperity and spiritual clarity, during the days of Moses or the reign of King Solomon. In contrast, the Chanukah menorah was born in a period of intense spiritual struggle and hardship under the oppressive rule of the Syrian Greeks.

The Rebbe sees these differences as the reasons and ingredients that create

your powerful Chanukah lights. For example, when life is good and the sun is shining, we produce a light that is good enough for our homes and Temples. But when we are oppressed by a heavy darkness that lurks outside, we must find a light strong enough to face and illuminate the darkness.

That’s the power of your Chanukah menorah’s light. It knows that when you face darkness and spiritual hardships, you don’t have the luxury of remaining the same person as yesterday; you need to grow and increase your light daily.

The fact that the Chanukah menorah is lit in the evening demonstrates how the light needed tonight differs from the light we needed during the good old Temple days. Today, we can’t survive on an “indoor menorah” or by merely illuminating our homes; we need a spark and flame that can thrive in the streets. We put our menorahs in our windows and doorways because its light can brighten the world.

The Rebbe sees these four discrepancies as the four steps in how to win the war against darkness:

1 2

By Benjamin Sherman

Grow and increase daily. A little movement forward and slight increases in your Divine light make your light so much more potent.

Create light according to the darkness. When the flames of antisemitism flare up and a new darkness confronts us, we need to find a more powerful Jewish light that has never shone before.

3 4

Shine outward. Today, we are all ambassadors of light, and we must warm the cold, unholy streets and spread the light and joy of Judaism with others.

Don’t be scared of the darkness. Like the fearless Maccabees, be courageous enough to shine, engage, and transform the darkness.

In conclusion, You can outshine any darkness if you’re brave enough to face a dark world and add one extra candle each night.

Benjamin Sherman is a staff writer for Chabad Magazine. He lives in Southern California with his wife and children.

by Asharon Baltazar

The household of Rabbi Chaim Halberstam of Sanz was used to things vanishing without warning. Whether it was a silver goblet, an ornate spice box, or the Shabbat candlesticks, all they could do was acknowledge the disappearance and continue on with their day. There was no thief to catch, no mystery to solve. Well known for his expansive adoration of fellow Jews, Rabbi Chaim pawned whatever he could find to help those seeking monetary relief, whether it was an orphan collecting for his wedding or a mother in need of food for Shabbat. With nothing spared, his house remained bare of furnishings most of the time.

Weeks before Chanukah, Rabbi Chaim opened the door to a haggard-looking gentleman and invited him into his study. The Jew, who had traveled long distances to get to Sanz, introduced himself, buried his face in his hands, and began to sob. Through his tears, he managed to describe his impoverished life. His daughter had reached the age of marriage, and he didn’t have the means to provide for her wedding.

Looking on with softhearted eyes, Rabbi Chaim solemnly shared the man’s misfortune. “G-d will help,” he promised.

In his mind, he was already thinking about what to give this poor gentleman.

ered, even calm. He smiled underneath his thick mustache and said nothing.

Late afternoon, after praying Minchah, all the townspeople rushed home to light the Chanukah lights. One by one, flames popped up in the neighboring windows, but the Halberstam house remained gloomy and dark despite the late hour. Rabbi Chaim was in his study, learning the mystical themes of the holiday. Despondent as they felt, no one wanted to bother Rabbi Chaim and remind him about the neglected mitzvah. The pain they knew they would see on their father’s face was too much to bear.

Suddenly, the study door opened and Rabbi Chaim appeared. If he was worried, he hid it perfectly as he busied himself with the lighting preparations, leisurely going about the room, gathering oil and rolling wicks. But there was still no menorah to light.

The household of Rabbi Chaim Halberstam of Sanz was used to things vanishing without warning. But there was no thief to catch, no mystery to solve.

Rabbi Chaim disappeared into the house. All of his shelves were empty. He skimmed the walls, shelves, drawers, praying he would find something to give the man. Nothing but dust. Everything had been pawned. But he could not send the man away without even a single coin.

The menorah!

Sitting on top of his bookcase was the handsome silver menorah he lit each Chanukah. Rabbi Chaim quickly brought it down, blew off the thin coating of dust, and wrapped it in paper to prevent unwanted stares. The man watched Rabbi Chaim, peering from behind the door, his worry melting into disbelief.

The man gingerly accepted the menorah, blessed Rabbi Chaim, and soon disappeared from view.

It was a week before Chanukah when the Rebbetzin finally discovered the missing menorah. Though she didn’t confront her husband, she felt a twinge of sadness. She couldn’t imagine her window bare of the festive lights while the homes around them glowed.

One day before Chanukah, she reminded her husband that their house had no menorah. Rabbi Chaim was not both-

As that thought crossed the minds of all present, a rhythmic clatter and the whinnying of horses sounded from outside. A luxurious coach had pulled up to the house. The door opened and a well-dressed couple stepped out, a package visible in their hands.

The two breathlessly apologized for the late hour, but also seemed impatient to speak with Rabbi Chaim. For an hour or so, Rabbi Chaim and the couple sat in his study, door closed, discussing a matter of urgent nature. Rabbi Chaim listened and showered them with blessings.

As the couple stood to leave, the man placed the package on the table.

“This is our thank you,” he said, removing the paper.

A tall menorah, wrought of the finest silver, stood twinkling on the table.

Rabbi Chaim’s face registered no surprise. Rather, he delicately moved the menorah to its usual place and crowned it with olive oil and wicks. In his right hand, Rabbi Chaim held the shamash and recited the three blessings.

The miraculous atmosphere of Chanukah was undoubtedly felt by everyone that year.

by Arnie Gotfryd

One elegant idea, developed by a child some 3,800 years ago, has transformed the world forever. That child was our patriarch Abraham, and his big idea, on closer inspection, seems more akin to ecology than to ethical monotheism.

So what’s the big idea? And how did he come to it?

According to tradition, Abraham was born in 1813 BCE in the ancient Iraqi town of Ur Kasdim. As a young child in a pagan culture, he practiced idolatry and prayed to the sun, believing it to have created the heavens and the earth. But something didn’t quite click. Whenever the sun set, it was out of the picture and the moon and stars dominated the night sky. Realizing the sun’s limitations, Abraham prayed to the moon. With time he realized that neither is the ultimate answer, and so he came to the conclusion that there must be one Creator with unlimited power and knowledge.

that discovered that the sun and moon aren’t the ultimate answer to life’s questions, would you desert your family, wage war on the government, and risk martyrdom? So what that the sun and moon don’t run the world? Is that a reason to go fanatic?

Let’s step back and look at Abraham’s quest as a logical problem. He was seeking some entity capable of creating and controlling the world as a whole. With nothing more than the world itself to go by, he had to work by inference. Knowing that everything that happens, happens for a reason, Abraham set out to discover that reason. Put another way, he set out to identify that Being responsible for the existence of... well, you name it: Matter, energy, motion, and life on the grandest scale imaginable. A theory of everything, if you will.

One elegant idea, developed by a child some 3,800 years ago, has transformed the world forever.

That child was our Patriarch Abraham.

Abraham was absolutely convinced that the prevailing pagan beliefs were wrong. He set about sharing his findings with everyone he met and successfully persuaded thousands to drop paganism in favor of his “heretical” views. Although popular with the public, Abraham was spurned by both family and the ruling class for bucking the system. After narrowly escaping martyrdom for refusing to deify the emperor, Abraham was forced to flee the country.

Only after all this does Genesis pick up the plot with Abraham’s journey to the Promised Land and the subsequent history of his descendants, both Jews and Gentiles. Such is the story. But is it really so simple? If it were you

No wonder, then, that he started by worshipping the sun. It is huge, powerful, and immensely influential. It is our preeminent source of light and heat. It drives the hydrological cycle and makes the plants grow and the animals thrive. It sets the days and seasons.

Today, we can overlook the sun. There are countless thousands of people who wake up indoors, take elevators down to subways, commute to skyscrapers they access from underground, and return home at the end of the day after shopping, dining and taking in a show, all without stepping outside. But back then, who knows, maybe it was a no brainer to see the sun as the creator of all.

But the sun has its limits. The moon rules the night. The stars, the tides, biorhythms, moods, all seem quite independent of the sun. If the moon can act where the sun

18 The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Kislev 5785 cannot, it shows a certain greatness above and beyond the sun itself. So Abraham worshipped the moon.

Now he could have stopped right there, like the rest of his compatriots. Each heavenly body with its own sphere of influence. Radiate and reflect, give and take, positive and negative, masculine and feminine, duality works fine for many cultures and faiths. But not for Abraham. He recognized duality, yet he suspected an underlying unity. But why?

The sun and the moon have a special relationship. While different as night and day (in light, in heat, in motion, in phases, and in seasons), they nevertheless share two remarkable qualities. First, they are exactly the same angular (or apparent) size, even though the sun is huge and far and the moon is small and close. Second, their paths intersect every once in a while resulting in spectacular eclipses. Whoever has witnessed a total solar eclipse knows the awe and wonder this majestic event evokes. It was obvious to Abraham that the coordination of the sun and the moon was not mere chance event.

Abraham understood a most basic principle of human logic, that everything that happens, happens for a reason. The very fact that solar and lunar sizes and motions are coordinated is itself a something, albeit an abstract something, which requires an explanation. The sun and moon should be viewed as an orderly system with a suitable cause.

Now the question was, what could the cause of this systemic property be? Could the two-part, sun-moon system originate in a duality or other plurality, say pantheon, of forces? Remember that Abraham had no clue about monotheism at the time. He addressed his question first using the pagan cognitive tools that were his heritage. Well, he must have thought, if it were the case that some divine plurality created the system, what was coordinating the parts of that higher plurality? And if nothing was coordinating the higher plurality, then how did their coordination come to be? Abraham wasn’t ready to drop cause and effect. Abra-

ham concluded that there had to be ultimately one factor unifying the sun-moon system. But what was it?

One possibility was that the control was within the system. That would mean, in effect, that the sun and the moon were coordinating themselves. But that did not seem feasible because seeing their individual orbits and properties, it was clear that the sun was not controlling the moon and the moon was not controlling the sun. Therefore, the control must be some factor which is not the sun and not the moon. Perhaps it was the earth, but that could not be because the earth was itself integrated systematically with the sun and the moon, for after all, that’s why Abraham worshipped them originally. The stars and planets too had their regular, integrated motions and specific roles in the grand scheme of things, so they were not the organizing force.

Clearly, whatever that force or being was, had to have two properties. It had to be external to the parts of the system, and it had to be more powerful than them, to keep all the parts in systemic order. Given that the system under consideration was now not just the sun and the moon but indeed the heavens and the earth as a whole, being external to it all implied being transcendent, and being more powerful than it all meant being omnipotent.

Abraham’s little idea grew from a child’s musings to a rational approach to nature as a whole, to a firm faith in a first cause so well established that most of the world’s inhabitants pride themselves in Abraham and his legacy of ethical monotheism.

Let us hope and pray that all Abraham’s children take to heart Abraham’s message of ethical monotheism. Both the ethical and the monotheism. Both the Divine unity, and the human.

Realistically speaking, as the world looks today, that would take a miracle, compared to which the bringing of Moshiach looks easy. Abraham was one alone, yet he changed the world. Perhaps we can do the same.

Abraham was a zealot. He was so intolerant of false notions that he smashed his father’s idols. That nearly cost him his life, but in the end, his new concept of one invisible, omniscient and omnipotent Creator caught on so well that today followers of Abrahamic religions comprise more than half of the world’s 8 billion people.

We all have a little Abraham inside us. I had an Abrahamic moment back in the early 2000s, and in a small way, I got some serious unexpected flak for it.

The idol I had set out to eradicate was more subtle than a pagan statue - it was a false idea. And of course, you can’t

demolish ideas with a hammer. You need persuasion. And if you are standing at the front of a lecture hall in the role of professor at a secular university, and you want to take down an idea, you had better do it with facts and arguments, not polemic and rhetoric.

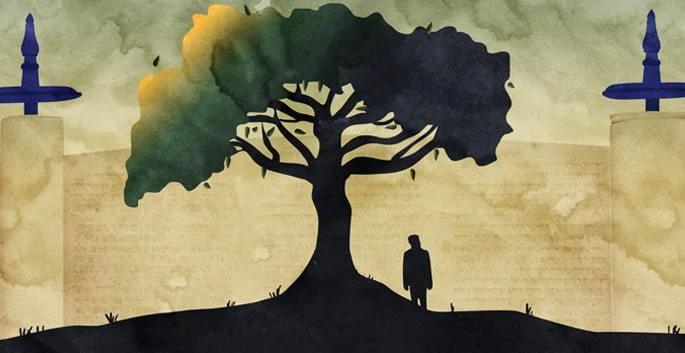

And yes, I was prepared. Having earned a doctoral degree in the University of Toronto’s Department of Zoology, I was exceptionally familiar with the ins and outs of the idea I was about to challenge - the most cherished dogma among biologists for a century and a half: Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, the idea that the diversity of life on earth is

the result of random mutation and natural selection.

The classic image is the “Tree of Life” in which humans are a recent branch tracing back to apes, then to earlier mammals, and back to reptiles, fish, and ultimately to the one-celled organisms from which all life is supposed to have evolved over many hundreds of millions of years.

The truth is I believed it too. Unquestionably. Until Chabad found me, at a weekend getaway for Jewish college students. Some rabbi was giving a talk on Love, Dating and Relationships (Yes, it was Manis Friedman), and although my curiosity was piqued, my secular background screamed in the back of my mind: “Don’t fall for it! It’s religious dogma from the dark ages. Religion is just a crutch for people who can’t take the truth.”

“Are there any questions?” I had barely gotten the words out when one very vocal young man let loose with a barrage of challenges of his own.

“I can’t believe what this guy is getting away with! Look at him! With that beard and the skullcap? He’s trying to indoctrinate you. Are you going to let him get away with this? If what he is saying is true, why doesn’t any other professor talk like this? We can’t take this lying down.”

We just sat there quietly for what seemed like a really long time. We both knew that this wasn’t about Darwin. This was about the girl.

We got into a six-hour argument, during which he had answers for all my questions and questions for all my answers. I was left in a state of suspended disbelief, not quite the atheist I thought I was, yet not ready to take Torah at face value.

Over the following decades, I became an avid reader and public speaker on the subject of the interplay of authentic science and traditional faith, including, of course, Darwinian evolution and all the related questions of cosmology and the age of the universe.

My talk that day was to the hundred undergraduates who had registered for my accredited Faith and Science course, and that day’s lecture was Evolution Myths and Facts. (You can find the gist of my talk at https://www. chabadrochester.com/library/article_cdo/aid/113105/jewish/Appendix-4-Evolution-Myths-and-Facts.htm)

But as prepared as I was to give the talk, I was certainly not prepared for what happened immediately afterward.

Several students reacted immediately, but not quite as he had hoped. The blue-eyed blonde said, “Why are you so nervous? He told us on day one, you don’t have to believe like him. You just have to understand the information.”

Then an Asian student chimed in, “What’s the matter, the scientific citations don’t exist? The math doesn’t add up?”

Then a fellow with a turban joined the fray, “Who is making polemic arguments here? It’s your claims that are spurious.”

Our rebel glanced from one student to the next in shock, like a deer in the headlights. He sank back into his chair. This gave me a chance to play ‘good cop.’ “I’m very interested in what you have to say. I have an office hour before class next week. Why don’t you come see me and we can explore your perspective at greater length then.”

I took his name (it sounded very Jewish), and we confirmed for the next week. Of course, I had my tefillin ready for his visit. “Hmm. Your name sounds Jewish,” I said with a smile as I started to take my tefillin out of their bag. He pulled up his sleeve, “I knew I wasn’t going to get out of this without putting on tefillin.”

I approached to help him wrap the tefillin and he took

20 The Chabad Times - Rochester NY - Kislev 5785 them before I had a chance. “I’ve got this,” and he made the blessing and started wrapping the straps himself. I opened the siddur to the Shema prayer, but before I could hand it to him he was already reciting it by heart - all three paragraphs. I asked him if he’d like to say more, and he grinned as he commented, “I’m not going to daven the whole Shacharit!”

This was definitely not the meeting I was expecting. As I put away the tefillin, we started to chat.

“Where are you from?”

“Here in town.”

“Where did you go to school?”

“Hebrew Academy.”

“So you are living at home?”

“No. Downtown.”

“In residence?”

“No, off campus.”

“Sharing a place with a few people?”

“Just one.”

“A guy or a girl?”

“A girl.”

“Is she Jewish?”

“No.”

by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks

The Jewish world has changed. Looked at from one perspective, that of our recent history, it is the worst of times. But from another vantage point, that of Jewish history as a whole, it is the best of times. Rarely in the four thousand years of our history, have Jews simultaneously had sovereignty and independence in the land of Israel, and freedom and equality in the Diaspora.

This raises questions of the most fundamental kind. Historically, Jews have learned how to handle oppression. Do we know how to handle freedom? We know how to cope with poverty. Do we know how to cope with

I looked at him. He looked at me. We just sat there quietly for what seemed like a really long time. We both knew that this wasn’t about Darwin. This was about the girl.

Because if Darwin is right, then the Torah may be wrong. And if the Torah is wrong, then Judaism is wrong, and living with a non-Jewish girlfriend is fine.

But what if Darwin is wrong? Well, then maybe Torah is right. And if Torah is right, then maybe living with a nonJewish girl is wrong.

That’s what he was fighting for. Not the origin of species. It was about the girl.

As Aldous Huxley, whose family was among the leading evolutionists of yesteryear, famously said, “We objected to the morality because it interfered with our sexual freedom.”

For him, and for me, letting go of Darwin’s Tree of Life was a necessary prelude to embracing the true Tree of Life, the Torah. And once you hold on to that, you never want to let go.

As we say after the Torah reading, “It is a Tree of Life to those who hold fast to it.” And that’s a kind of zeal that’s really not so scary. As the verse continues, “Its ways are pleasant and all its paths are peaceful.”

affluence? We have unrivaled experience in living with powerlessness. Do we know how to live with power? The whole of Jewish history has been a journey towards Israel, acceptance, the freedom to live our faith without fear. We know how to travel. Do we know how to arrive?

For what the world faces today is an epic clash between the universal and the particular, in the form of the global economy on the one hand, and resurgent ethnicity on the other. Rarely if ever before have we needed more urgently the classic Jewish imperative: to be true to our faith while being a blessing to others regardless of their faith.

This is how the Torah tells the story of Abraham. He fights a war for the sake of his neighbors. He pleads with G-d on their behalf. Yet he does not adopt their way of life. He is in, but not of, his time and place. His faith is

singular, his moral concern universal. That is what makes his contemporaries say of him, “You are a prince of G-d in our midst.”

To be of relevance to the world, we must keep faith with what is distinctive about ourselves and our faith. We must be prepared to mitigate the split between the universalists and the particularists, asking the former to reengage with Judaism and the latter to re-engage with humanity as a whole. To heal a fractured world, we must first heal the fractures within the Jewish soul.

by Shira Gold

Moran Stella Yanai was selling her custom jewelry at the Nova Festival on October 7th when terrorists began hunting for Jews to murder and capture. They targeted Jews like you and me, and the only thing that set Moran apart from us was her proximity to Gaza.

I recently drove to Yorba Linda, California, to meet Moran, one of the few hostages who, after fifty-four days in Hamas captivity, somehow finds the strength to travel the world, bringing awareness to the hostages and telling their story of faith and resilience in the face of unspoken darkness.

Many people remember seeing the TV coverage of a forty-year-old hostage on crutches reaching out to embrace a woman in a Red Cross jacket. The entire world watched her release on November 24th, 2023, and now, as I arrive, I see Moran sitting on a bench outside Chabad of Yorba Linda without crutches, soaking up the sunshine. I say “Shalom” and hug her.

Moran is an artist and poet who knows how to design her spoken words beautifully. She likes to recount how many times she saw the hand of G-d protect her while in Gaza and how gratitude helped her survive and continue to survive. Starting with that sudden gut feeling not to listen to the police officer who, in the original chaos, told her and her friends to head to the street behind the festival; sadly, those who did listen didn’t survive.

Although the Yanai family is Jewish, Moran’s childhood wasn’t religious. Still, her mother, a proud Jewess from Egypt, did teach her kids about faith in G-d and, for fun, a little Arabic. On October 7th, Moran used her faith, wit, and Arabic to convince the first two groups of gunmen to leave her alone since “she’s an Arab” and was thereby able to save several festival goers from capture. But, eventually, after hours of running and hiding and injuring her ankle, a third group of bloodthirsty terrorists brutally forced her into a stolen car and, within minutes, told her, “Welcome to Gaza.”

Earlier that fateful morning, Moran had given little thought to her wardrobe choices for attending a jewelry booth at a desert rave. However, now her green pants and combat boots had convinced her captors that they had scored a soldier. While a doctor looked at Moran’s injured ankle, she quietly pleaded for his help, only to realize that the doctor was not there to help her. She was on her own.

In the moments when no one can help us, we pray. Moran knew only three prayers: the Shema, the blessing for lighting Shabbat candles, and the morning blessing of gratitude for being alive called Modeh Ani.

You would expect any hostage to experience shock, anxiety, panic, and fear. Yet, for fifty-four days, Moran focused on the fact that she was alive and would repeat this prayer throughout her long days in captivity: Modeh Ani. “I offer thanks to You, Living and Eternal King, for You have restored my soul within me; Your faithfulness is great.” She was dragged and kidnapped but alive. Moran says this prayer to stay alive.

While in Gaza, the kidnappers told Moran that her family, country, and G-d had given up on her. They pointed a gun at her head and threatened to kill her. At one point, the weeks of mental torture, physical malnourishment, lack of essential hygiene, and food poisoning eventually left her body lifeless, and Moran remembers the guard coming to check if she had died.

The harsh reality in captivity had depleted her morale, and she would need another sighting of the “Hand of G-d” to help turn her away from death’s door and guide her back to health. That’s when the guard started scanning the radio for another Arabic news station, and suddenly, Sarit Hadad’s voice, “Shema Yisrael Elokai,” filled Moran’s heart with hope. The guard quickly switched the channel, but it was too late. Moran would survive.

Moran shares her message and explains that the hostages are stronger than we imagine; they are lions and lionesses of Judah. They don’t want your pity; they want your light. In her darkest moments, Moran imagined her family celebrating Shabbat; it gave her the strength to survive. Now, she urges women everywhere to light Shabbat candles to bring light and hope to the hostages still held behind.

I asked her if she was getting back into her custom jewelry business, and she explained that she was only working on helping the hostages. Still an artist, Moran is teaching the beauty of Modeh Ani gratitude and painting a clear picture of what we can do for the hostages: They want our light.

by Yaakov Ort

The first crystal-clear memory I have of the trip up to Woodstock is when we hit 85 miles per hour on the open road in my friend Stevie’s 1968 Buick Wildcat. We were just past the New York State Thruway tollbooth in Newburgh when we raced up alongside a wildly Day-Glowed VW Bug convertible with a big white peace sign painted on its back. We flashed the V (“peace”) sign to five or six young people who couldn’t possibly fit in a car that small, but somehow did. The feeling was a pleasantly paradoxical mix of freedom and connectedness - the certainty that we were all heading towards something unknown, exciting and new; perfect strangers eloping together, escaping the known, depressing and old, the world of Richard Nixon and Richard Daley, Brezhnev and Mao, Elvis and the Rat Pack, war abroad and race riots at home.

We had purchased tickets in advance at a local head shop in Brooklyn, and we were among the first few hundred thousand young souls who were there on day one. It had rained the day before so that by the time we got to Yasgur’s farm, it was a mix of mud, manure and what would swell to about 400,000 people, all attractive not because of what they looked like, but because of what I hoped they hoped for - people who I imagined were just like me, yearning for the Age of Aquarius of which this was the dawning; people longing for a life based on peace, love, freedom, deep spirituality and respect for all humankind. This would come about only through a quantum global leap in human consciousness that would be launched by love, mindaltering chemicals and us.

After sleeping in the mud, taking some bad drugs, being too far away from the stage to enjoy the music, and witnessing some very frightening human breakdowns, I found a ride back to the city after a day-and-a-half, feeling down, dirty and depressed.

For decades, I would proudly tell people that I was there, but not be very honest about what it was like.

Life’s whirlwind took me elsewhere, really fast. Less than two years later, I was a 20 year old working for the publisher of The New York Times as his office boy, living in a door-manned high rise on Manhattan’s Upper East Sidelooking back at Woodstock and all that it represented as an insanity-producing exercise in communal self-indulgence

and self-deception.

My shoulder-length hair was now trimmed by Jerry at Bergdorf-Goodman, my tie-dyed tank tops, Levi 501s and Frye boots supplanted by Sea Island cotton shirts, suits from Paul Stuart and shoes from Church’s. Opiated hashish and LSD, having permanently burned out the bodies and brains of some very close friends, were recognized as the very dangerous drugs that they were (and still are), and were replaced by far less crazy-making intoxicants like Johnny Walker Black on the rocks and Stolichnaya gimlets. Love, not war was replaced by a new mantra: Life is a game in which he who dies with the most toys wins.

That didn’t work out so well either.

By the summer of 1985, a decade-and-a-half of the fast life in the big city had taken its toll on my relationships, my finances and my health, and I was looking for something - anything - different. When I saw an ad in The Village Voice for an “Encounter with Chabad” weekend in Crown Heights, I thought I’d give it a try. Although I grew up in Brooklyn, I had never, not even once, had a conversation with an Orthodox Jew - let alone a Chassidic Jewabout anything substantive. I showed up in Crown Heights so clueless that it didn’t occur to me that I should bring a kippah with me (not that I owned one). And I found something very different than anything that I had expected.

There I found men and women, Chassidic Jews, from all kinds of backgrounds. A few were college-educated, but most had families that were Chassidic for hundreds of

years. But just about all of them were in some very important ways kindred spirits to my younger self - still possessing a deep belief in the potential of human goodness and the possibility of a world transformed, not just longing for, but working towards that quantum leap in global consciousness that my generation had so deeply hoped for - and abandoned.

Fascinated by the people I met that weekend, I decided to study in a yeshiva while continuing to work at the Times. I soon learned about some deep spiritual concepts that explained the world in which I live and my purpose in it. Two key ones presented to me in my study of Tanya and Likkutei Torah were the primordial worlds or dimensions of Tohu and Tikkun.

I learned how perfect, holy souls like yours and mine are sent down into an imperfect, unholy world in order to bring “the lights of Tohu into the vessels of Tikkun.” That means, in short, that we’re all here on this planet to harness the passionate, chaotic, destructive energy of a ruptured primordial world that usually manifests itself in all kinds of physically and spiritually damaging ways. We need to channel that raw, intense energy through G-dly thought, communication and behavior defined and bounded by Torah and Jewish law, the deeply detailed Divine guidance for a life well-lived. The goal is to build a world that will be a dwelling place for G-d and humankind, filled with eternal, Divine consciousness.

No drugs necessary.

for a better future and channel it into a global revolution of goodness, kindness and G-dliness. He knew it was possible, and he showed us how to do it.

My shoulder-length hair was now trimmed by Jerry at Bergdorf-Goodman, my tiedyed tank tops, Levi 501s and Frye boots supplanted by Sea Island cotton shirts, suits from Paul Stuart

The Rebbe taught me to slowly but surely discover a little bit more every day about myself, about the world I live in, and about G-d. To nurture whatever I am most passionate about, and figure out how to use it for the benefit of others. To be curious about how G-d wants me to live in the world. To find out how to engage in a well-lived life by studying the written and oral Torah - life’s blueprint and instruction manual. To set up a fixed time for Torah study, however modest, every morning and every night. To focus on giving to others, not on getting for myself. To find mentors who I admire and trust. To share what I’ve learned and experienced. To discover the sublime, incomparable joy of learning Torah in depth as an end in itself.

To pray sincerely and give of myself generously. To find a congregation, a community of people who I like and identify with, and join humankind everywhere in a revolution in behavior and consciousness that, with G-d’s help, will achieve a critical mass of goodness and transform this fractured world of ours into one that is forever filled with love, respect, compassion and harmony in what we call the Messianic Era.

It’s an era we have not fully entered yet, but despite some appearances, we’re getting closer and closer to its complete and final unfolding every day.

All things have their root on high, I was taught. True, the psychedelics, the hippiness, the free love - in practice, these all proved to be destructive, even deadly, emanations of the unbridled light of Tohu. Nevertheless, at their essence they contain Divine sparks of powerful energy, meant to be redeemed and used for holiness. And I had found the means to do that, by safely channeling that energy into the bounds of the vessels of Tikkun - through the mindful and heartfelt study of Torah and the passionate, joyous performance of mitzvahs.

My own journey took me from Crown Heights to Israel. Fifty years after Woodstock, sitting here in Jerusalem reflecting on the past and the future, the world’s and my own, with years of Chassidic study and practice behind me, I can see more clearly than ever how the Rebbe sought to harness my generation’s raw, youthful energy and hope

After a 35-year career at The New York Times, retiring as group director for creative services, Yaakov Ort is now living in Israel enjoying his second career as senior editor at Chabad.org.

In today’s tumultuous post-October 7th world, worry and anxiety have become my unwelcome companions. The knowledge that my quest for calm amidst life’s chaos is universal and ageless comforts me to a degree. I was reminded of this consoling truth when I read “Letters for Life: Guidance for Emotional Wellness from the Rebbe”.

Over his decades of leadership (1950-1994), the Rebbe received millions of “old-fashioned” letters from individuals across the globe. The people writing to the Rebbe were real men and women struggling with everyday human problems. Worried parents, grief-stricken widows, hippies with questions, and lonely and confused adolescents searching for direction. The Rebbe patiently responded and guided them all toward a more fulfilling life.

To date, over forty volumes containing some 20,000 letters have been published. Luckily, Levy Y. Shmotkin, a Chassidic writer and scholar, has released a curated selection of the Rebbe’s ‘Letters for Life’ at the perfect time for many of us. He distills the Rebbe’s holy wisdom on emotional wellness into actionable advice directly addressing today’s reader. As the book’s insightful editor and narrator, Shmotkin meticulously selected key messages from thousands of letters and categorized them into mental health and well-being themes. This treasure trove of the Rebbe’s Torah-based advice provides intellectual clarity and practical guidance for anyone navigating the complexities of modern life.

Interestingly, Shmotkin initially started delving into these letters while in his late teens, to find answers to his struggles. Applying them to his journey into adulthood, he found them invaluable tools for a calmer and happier existence. That’s when he also began to notice recurring themes and patterns of advice that he felt would have universal appeal.

As Shmotkin clarifies, the book doesn’t seek to replace medical professionals or your therapist. Instead, it provides lay people and professionals with the Rebbe’s insights into

age-old problems, similar to a Divine roadmap drawn from the Rebbe’s wisdom to guide you through life’s challenges. For example, one central theme in the Rebbe’s correspondence is empowerment through purpose. Many letters counsel their recipients that every individual matters and that no matter how bad someone might feel about themselves, they have an indispensable role in the world. In today’s society, the rampant lack of purpose has devastating consequences for all ages. In contrast, a healthy sense of purpose can be transformative, giving individuals the motivation and confidence to overcome their internal struggles.

Marc Wilson, a syndicated columnist and community activist in North Carolina, faced a dark period after his second marriage and career collapsed. A friend advised him to see the Rebbe. Despite the brevity of their meeting, the Rebbe’s counsel was particular. He suggested Wilson teach Talmud, even if only to one or two people in his living room. “Sometimes a devoted lay person can do incalculably more good than a rabbi,” the Rebbe explained. After an even darker period of stagnation, Wilson eventually acted on this advice, beginning his journey of healing and restoration to soundness and self-respect.

NMLS #46832

Justin Smith Vice President Senior Branch Manager

585 442 7014

585 461 4939 FAX

Jesmith@mtb.com

Brighton Branch 1627 Monroe Avenue Rochester, NY 14618