Reclaiming Alleys

Building on a Walkable Center City

In 2025, Philadelphia has been named – for the third year in a row – the #1 “most walkable city to visit” in the USA Today 10 Best Readers’ Choice Awards. This confirms what those who experience Center City on foot already know. William Penn and Thomas Holmes laid the foundation with a logical street layout with regular blocks that makes navigation intuitive. Our dense, mixed use downtown concentrates residential high-rises, office towers, restaurants, shops, cultural venues, and services is a small footprint, so that most daily needs can be met within walking distance. Transit brings commuting workers and visitors into the walkable core. Active street life comes from ground-floor retail, restaurants, and businesses that keep sidewalks populated and interesting. Of course, Center City District’s on-street teams work hard to provide supplemental cleaning, public safety, homeless outreach, and hospitality services with the goal of making the sidewalks comfortable and inviting for all.

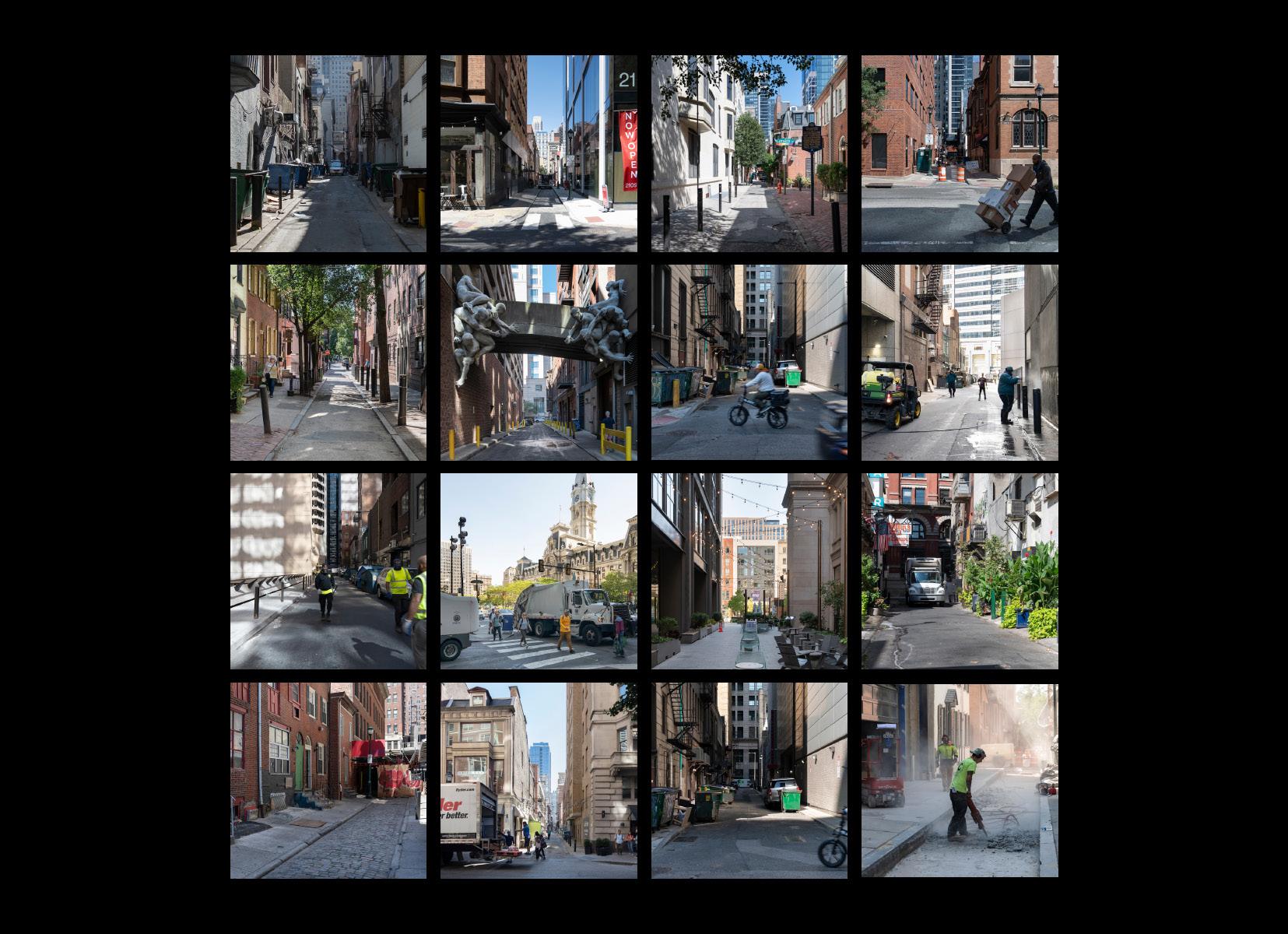

Center City’s alleys, like Open Streets and improved wayfinding, represent a very exciting opportunity to further enhance Center City Philadelphia’s walkability. Our many forlorn alleys are optimally human in scale, making them ideal for transformation into interesting and charming paths. However, today, many alleys are lined with overflowing dumpsters, often covered with graffiti, and harbor the quality of life issues exacerbated by this neglect.

By choosing to prioritize better oversight and thoughtful updates to existing regulations, alleys can evolve beyond their role as back-of-house service corridors into safe, clean, and active spaces that support both commercial and residential life. When reimagined with care, alleys can even become celebrated destinations that enhance, rather than detract from, the character and identity of the downtown.

Melbourne is a model for Philadelphia. “The laneways (alleys) were the crappiest space you could think of in Melbourne,” said Helle Søholt, the co-founder of Gehl Architects in the 2012 movie The Human Scale. “It was never ever thought about as a people space, but at the same time, they had this very nice human scale to them.” Today, the city’s tourism website states that laneways “evokes a riotous colour of street art, the scent of freshly roasted coffee, cutting edge boutiques, chic restaurants, and bars — soooo many hidden bars.”

Philadelphia already has the building fabric and geometry to make the same transition; we need the imagination and will.

Investigating the Alley Network

Wanting to further understand this opportunity, the Center City District team conducted a survey of over 2.5 miles of Center City's alley network — 45 alleys in total — to gain a deeper understanding of how these vital yet often untended public rights-of-way function. The goal was to develop strategies for enhancing conditions that will pave the way for transforming these overlooked spaces into valuable public assets.

We discovered that while many alleys in Center City need improvement, they also show substantial promise. In addition to enhancing walkability, clean alleys will unlock the value of adjacent real estate, providing additional opportunities for retail or workshop spaces at lower rents for small businesses, artisans, and entrepreneurs.

What is an alley?

Alley, alleyway, laneway, back street, side street, passageway, service street... Alleys are generally narrow, mid-block streets between buildings that are within the public right-of-way. Alleys are not uniform but are multifunctional spaces of varying scale and purpose. They serve as maintenance and waste collection areas to buildings, pedestrian pathways, primary entrances to residences and retailers, and are active connector throughways for vehicles.

Why do we have alleys?

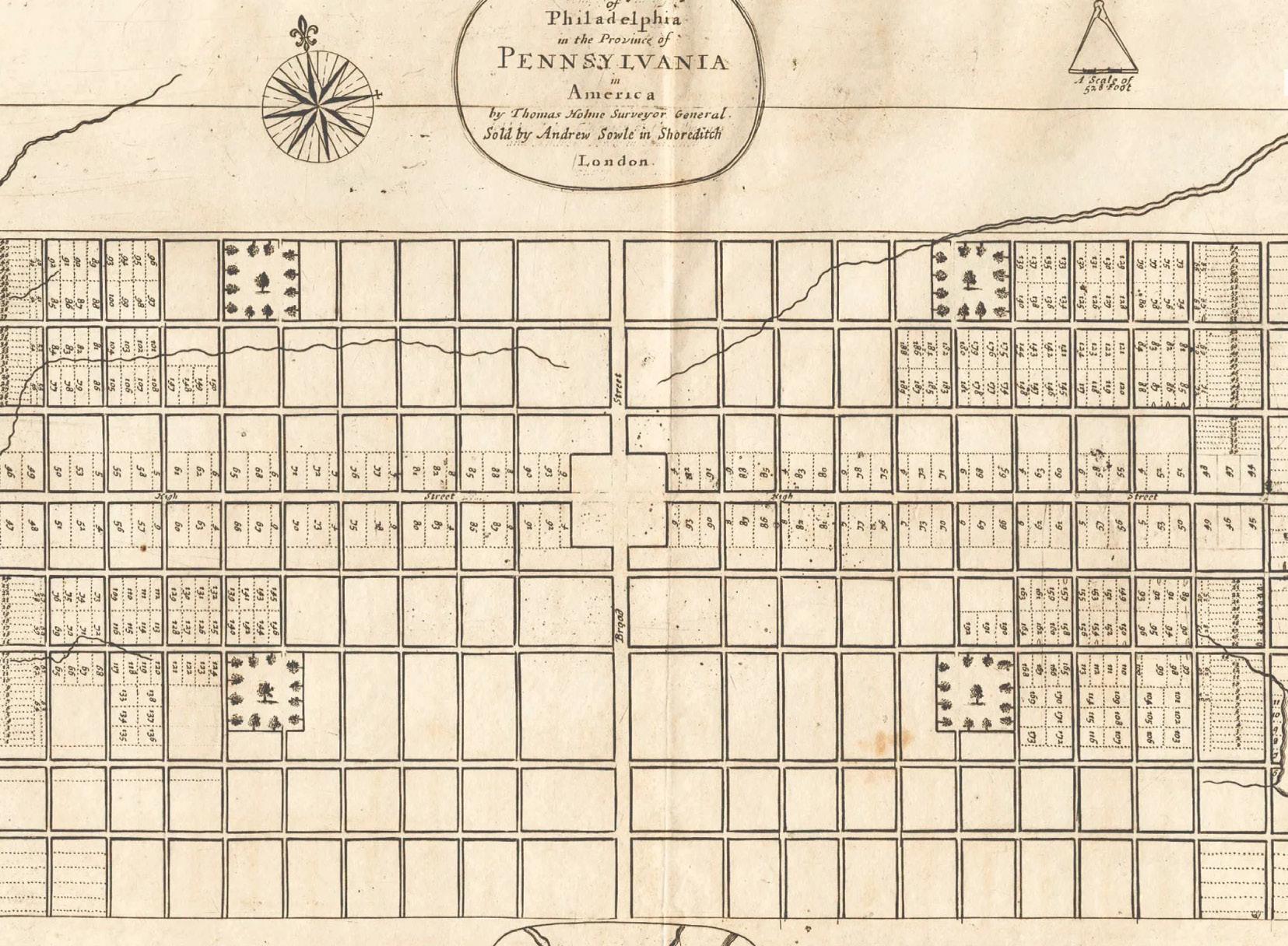

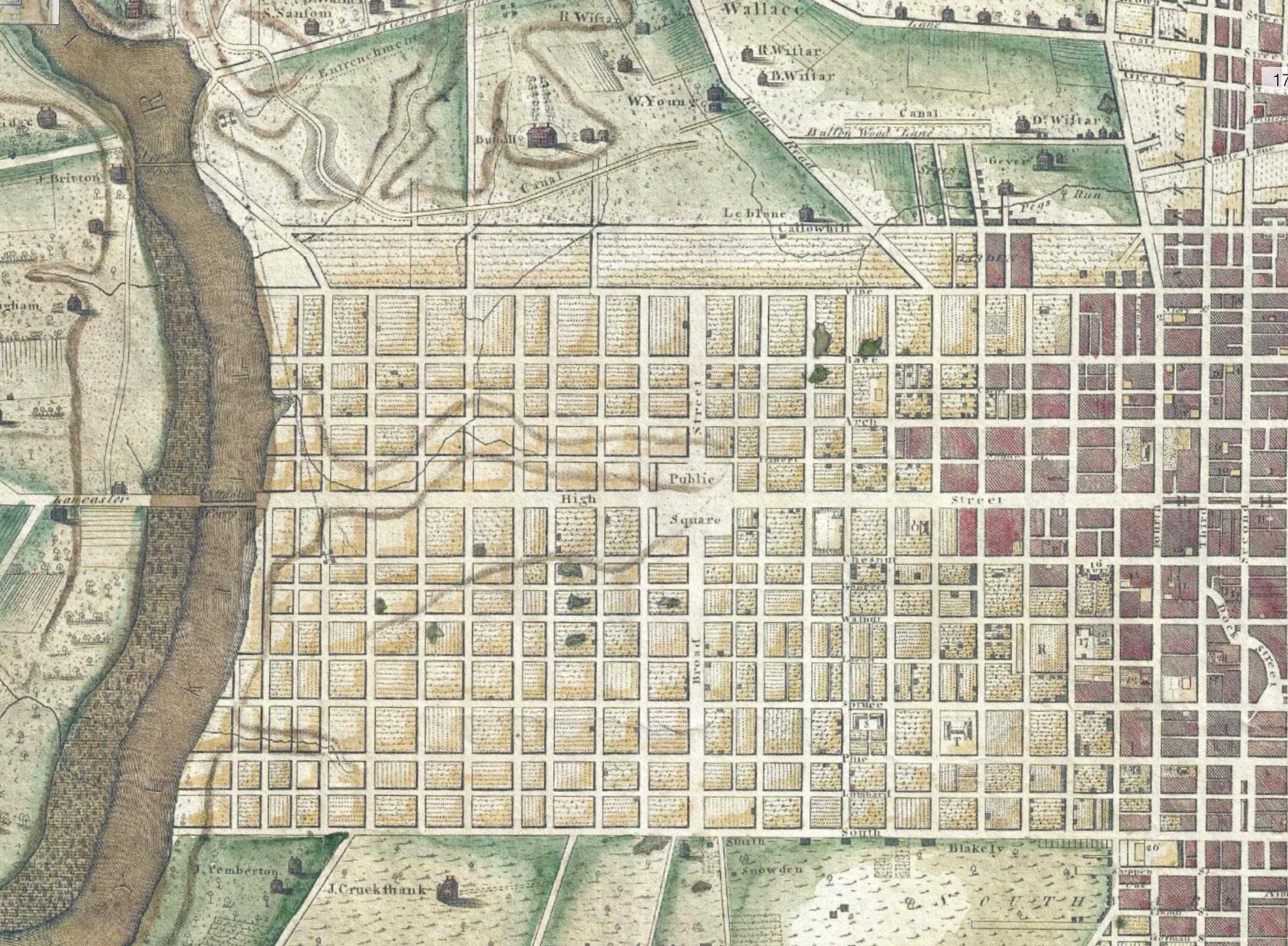

Although Philadelphia was the first colonial American city to be formally planned and laid out, alleys were never part of the original design. William Penn’s vision of a “greene country towne” focused on the structured grid plan that still defines the city today. However, as development expanded westward from the Delaware River, alleys emerged organically.

These alleys, or “minor streets,” were a practical response by private property owners seeking to create passageways between major streets. By bisecting colonial-scale blocks, they also provided homes with greater access to light and accommodated essential urban living needs, such as stables, privies, and other necessities of daily life.

In the 18th century, private development incentives played a key role in the creation of alleys. Departing from Penn’s vision of spacious lots with only a few large dwellings, landowners subdivided their properties to construct multiple rowhouses, increasing both density and profitability. Notable examples include Elfreth’s Alley in Old City and Drinker’s Court in Society Hill – both designed to provide access to the tightly packed trinity homes that line these blocks.

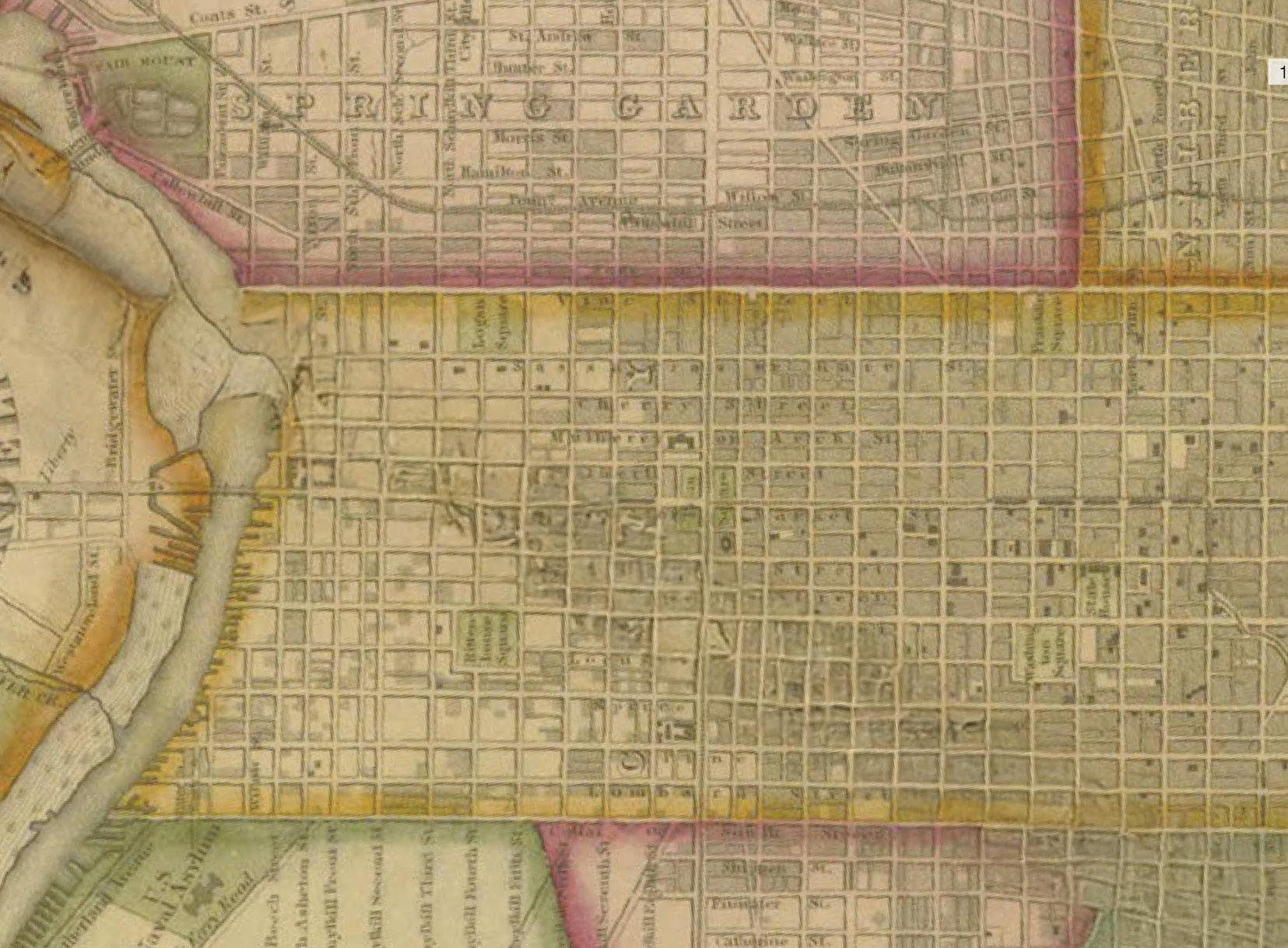

As urban development surged in the 19th century, alleys became an established part of the city’s street infrastructure. As buildings grew in size and function, alleys in the city’s core took on a more service-oriented role, facilitating waste collection, delivery access, and other essential functions that supported the expanding built environment.

Today, alleys remain essential to the city’s infrastructure, particularly for waste collection. However, they struggle to meet modern demands, as they were originally designed for horse-drawn carriages, not large trash trucks. Additionally, with the rise of single-use materials and shifting consumption habits, buildings in 2025 generate significantly more waste than they did a century ago, further straining the physically narrow, yet extensive network.

Framing the Problem

Frustration over alleyway conditions has persisted for decades, with ongoing concerns from Center City residents, stakeholders, business and property owners, and visitors regarding cleanliness, safety, and maintenance.

However, this does not have to remain the default. Early Philadelphians created alleys to suit their needs at the time. While we have inherited this model, we have the opportunity to redefine and reshape how alleys function in 21st century urban life – in fact it’s already happening.

The current state of Center City’s alleys — often defined by overflowing dumpsters that contribute to various quality-of-life issues — creates significant challenges for adjacent business owners and shapes negative public perceptions of safety and cleanliness in Philadelphia. These conditions frequently undermine the daily efforts of Center City District’s on-street teams, from sidewalk cleaning to homeless outreach.

But the current status quo does not have to define the future of our alley network. With improved coordination and enforcement, outreach to business owners about the importance of dumpster maintenance, and light modifications to existing regulations, these alleys have the potential to be clean, safe, and highly functional spaces that contribute to, not detract from, the downtown experience.

Moreover, there are already existing systems in place that can significantly improve the conditions of our alleys. The City of Philadelphia has longestablished regulations and codes for keeping dumpsters clean and secure. These include:

1. A visible medallion identifying the permit holder

2. Waste collection at least once per week

3. Dumpsters that are clean, well-maintained, and free of offensive odors

4. Properly painted surfaces, free from graffiti

5. Tightly sealed lids with a litter-free surrounding area

Adhering to these standards would lead to cleaner dumpsters and, in turn, cleaner alleys. Effective enforcement — whether by City personnel, property owners, or third-party agencies — can help ensure these regulations are consistently upheld.

On-the-Ground: A Survey of 45 Center City Alleys

In light of increasing concerns from business owners and residents, and broader quality-of-life impacts tied to alley conditions, the CCD team undertook a study of 45 commercial alleys. Surveys conducted in July 2024 and January 2025 captured seasonal variations in behavioral and physical conditions.

The survey team primarily focused on the following:

• Dumpster conditions

• Permit holder information (e.g. medallions)

• Quantity and types of entrances/exits

• Homeless activity

• Waste hauler identification

Ground Survey Data:

446 dumpsters surveyed

68% of dumpsters unlocked or unsealed

41% of dumpsters with trash adjacent or beneath 77% of dumpsters without permit holder information 60% of alleys with homeless activity

75% of dumpsters were open or unsealed when homeless activity was observed

21 waste hauler companies identified

3 companies serviced 65% of all dumpsters in the study area

Unpacking What We Learned

Simply put, there is a dumpster problem. Of the 446 dumpsters surveyed, 67% were unlocked or unsecured, and 41% had trash scattered beneath or nearby making them non-compliant with City regulations. These conditions directly contribute to the visual disorder commonly associated with our alleys and significantly affect public perception of crime and safety in Center City.

Neglected dumpsters also contribute to wider quality-of-life issues. The team observed homeless activity in 60% of the alleys surveyed, and in those locations, 75% of dumpsters were found to be unlocked or unsealed — highlighting a strong correlation between poor dumpster conditions and behavioral patterns in the alleys.

Unsurprisingly, the CCD team has noted a rise in both homeless encampments and discarded drug paraphernalia at these sites over the past year.

Additionally, while the City requires all dumpsters to display medallions for ownership identification, only about 25% had any form of ID. Identifying who is responsible is essential for effective enforcement. In contrast, most dumpsters displayed stickers from waste hauling companies—at least 21 different haulers operate in Center City alleys. In one alley alone, six separate companies were observed.

Consolidating waste services could improve quality control, reduce alley traffic, and help lower emissions.

Surveying 45 alleys also revealed just how diverse these spaces truly are. Alleys in Center City are far from uniform—they vary widely in scale, function, and use. Some were active with pedestrians and bicyclists, others included residential properties or hotel entrances, while several functioned purely as back-of-house spaces with little to no foot traffic. Perhaps surprisingly, out of more than 600 doors observed, nearly 25% served as primary entrances—highlighting that many alleys function as main access points for residents, business owners, and visitors alike.

To effectively improve these spaces and unlock their full potential, we need to understand the key characteristics that define them. As a result, we categorized the alleys into three distinct types: service, pedestrian, and pedestrian/vehicular. This framework serves as a guide for making strategic enhancements that respect both the operational and versatile nature of the alley.

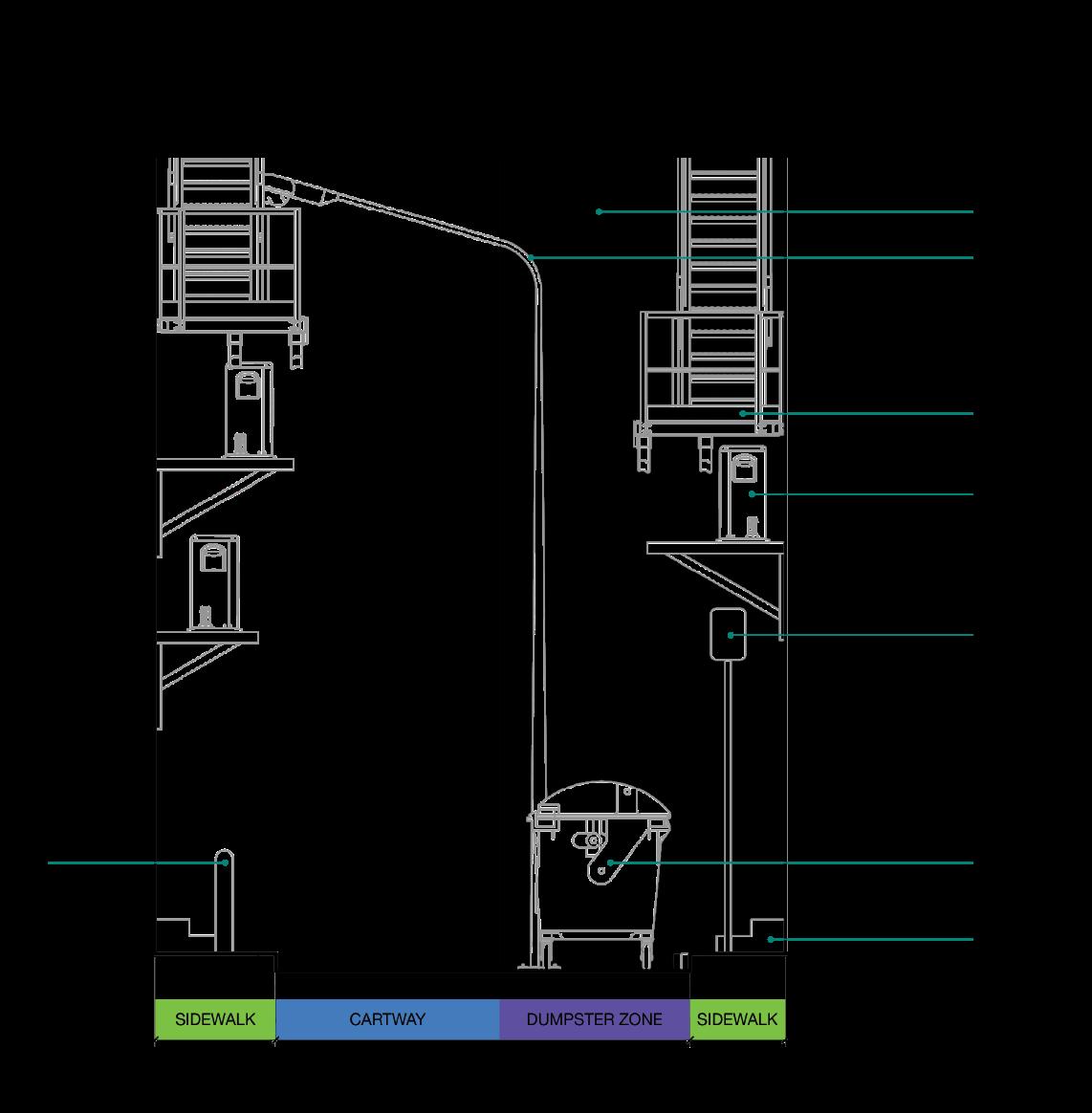

Alleys with narrow sidewalks and street widths, primarily used to service buildings for waste hauling, deliveries, and general egress to the adjacent buildings.

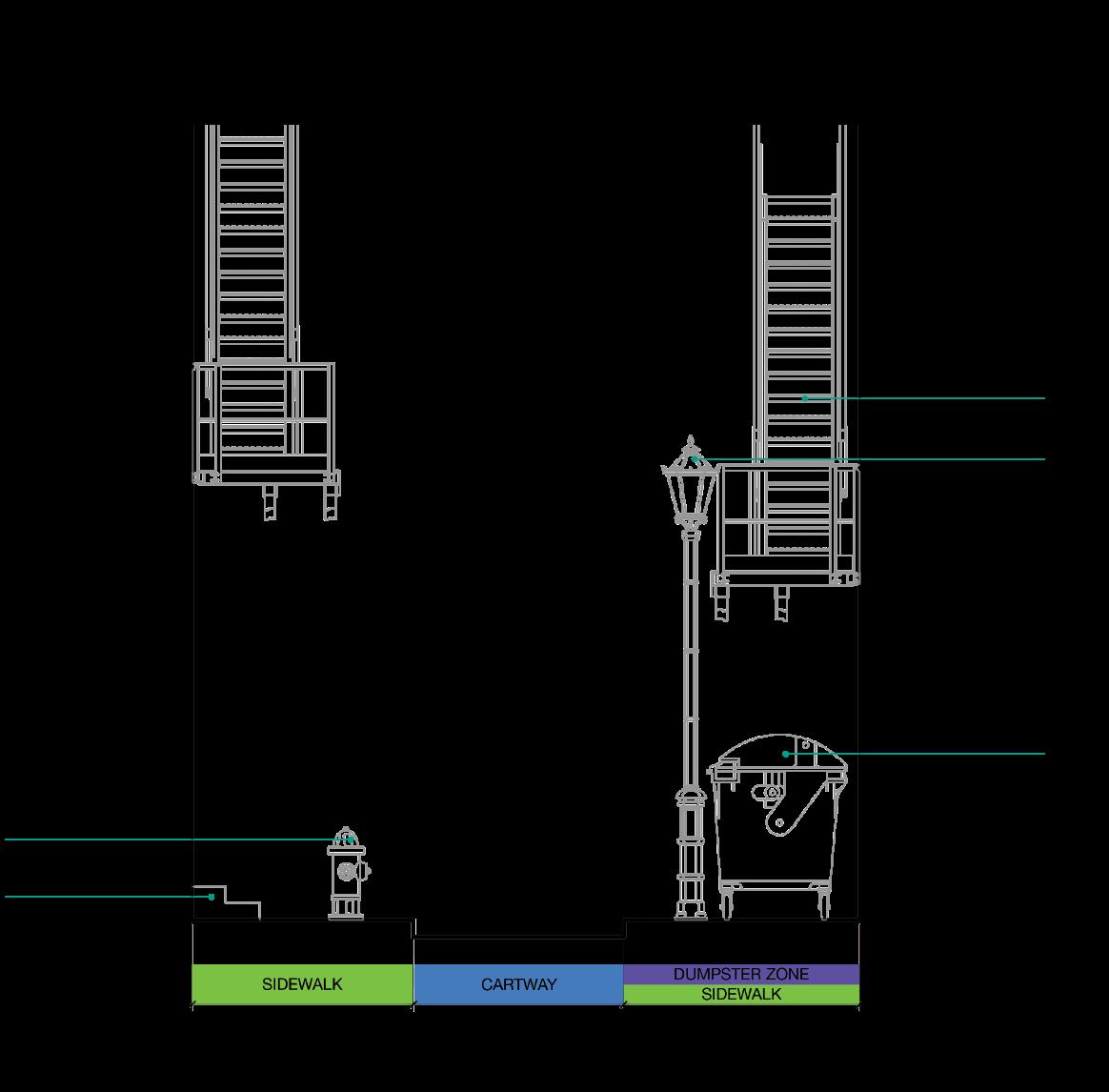

Alleys with a mix of residential and commercial building entrances, and where sidewalk widths are ADA compliant, primarily used as pedestrian pathways.

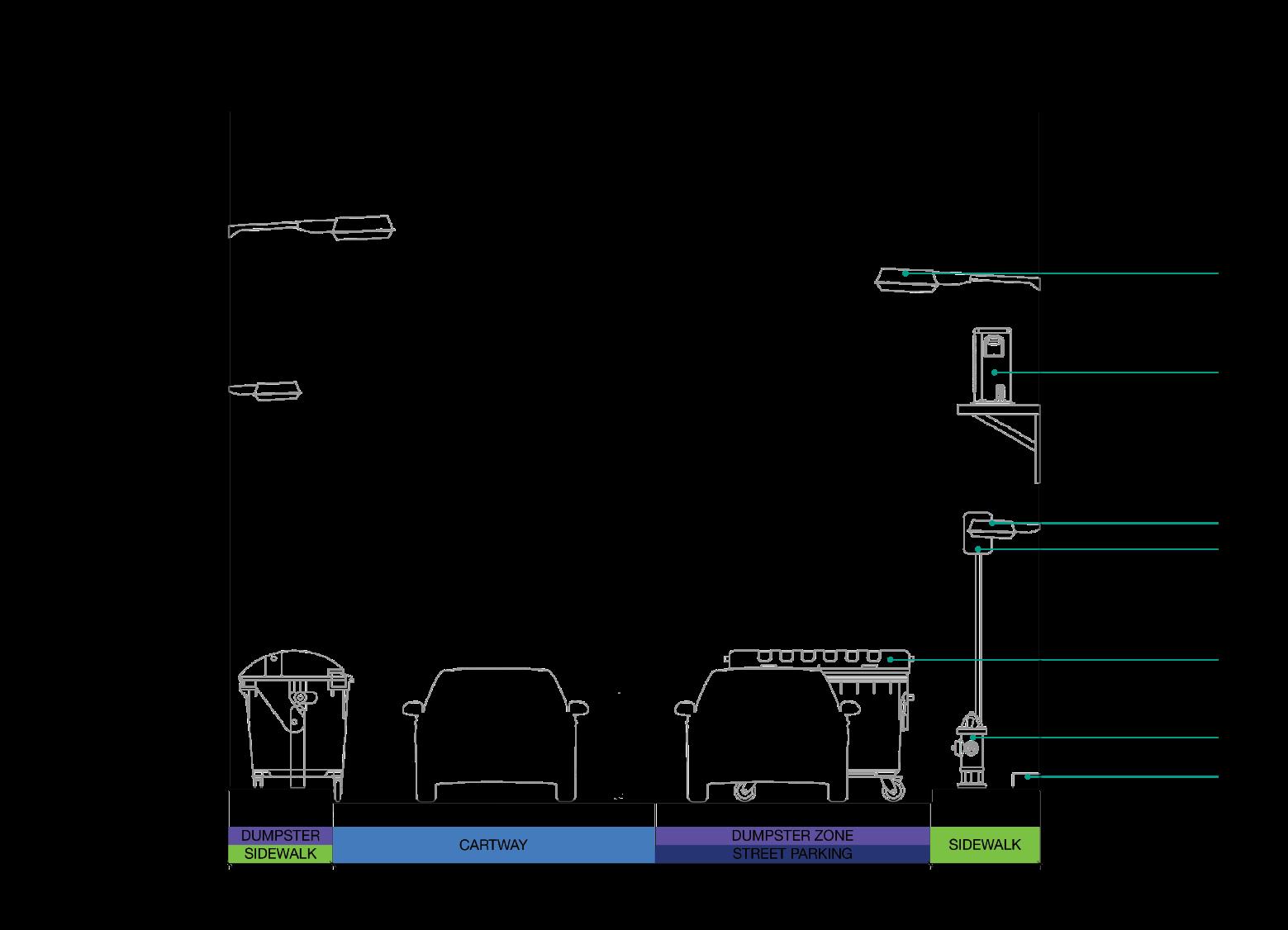

Alleys with greater street widths that primarily function as pedestrian and vehicular or loading zones), but still serve as “back-of-house” to adjacent buildings and contain multiple dumpsters.

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

“ “

Jane Jacobs - The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Opportunities for Transformation: Looking at Other Cities for Inspiration

As we dive into some inspiring examples of alley transformations from around the world, think about what could work in Philadelphia, especially for pedestrian focused alleys. Yes, every alley needs basic improvements like cleaning and upkeep — that’s priority number one. But beyond that exists an opportunity to reimagine what the spaces can be. Keep an eye out for features like public art, overhead lighting and installations, curbless walkways, and simple touches of greenery that bring these humble spaces to life.

Melbourne, Australia

Laneways

Timeline: 1992 - Present

Melbourne’s laneway revitalization, which began in the early 1990s, sought to transform the city center by encouraging vibrant urban life. The strategy involved cleaning streets, promoting mixed-use development, and attracting international students and local businesses to activate urban spaces. Key approaches included a temporary public art program, incentivizing cafés and retailers to occupy laneway spaces, extending business hours, and limiting vehicle access to create pedestrian-friendly environments that enhance connectivity and make the city center more dynamic.

Sydney, Australia

City Art Laneways

Timeline: 2008 - Present

The Laneways temporary art program originally ran from 2008 to 2013. It aimed to create opportunities for artists to test ideas through temporary artworks that projected light onto laneways, which we previously overlooked and underused spaces in the city. The program encouraged people to visit the city and explore these spaces.

Vancouver, Canada

The Laneway Project - Ackery’s Alley & Alley Oop

Timeline: 2016 - 2018

Vancouver is transforming downtown laneways from utilitarian corridors into vibrant, unique public spaces that can increase pedestrian areas by up to as much as 30%. By developing an interconnected network of lanes, each with its own distinct identity, the city aims to create stronger neighborhoods and communities. Beyond initial redesign, the project involves ongoing maintenance and collaboration with local organizations to continuously activate and preserve these spaces through creative programming and events, recognizing that each laneway will evolve differently based on its surrounding context and community interactions.

Detroit, Michigan, USA

Parker’s Alley

Timeline: Completed in 2019

A revitalized retail and dining destination with live music, local shops, and temporary art installations. Developed by Bedrock in collaboration with Shinola and adjacent to the Shinola Hotel.

2026 and Beyond: Reclaiming the Alley Network in Center City

Philadelphia is approaching a milestone year: 2026. As the birthplace of the nation, the city will celebrate America’s 250th birthday while also hosting major events like the FIFA World Cup Qualifiers and the 2026 MLB All-Star Game, drawing visitors from across the country and around the world. This presents a unique opportunity to harness the momentum, improve alley conditions, reinvest in downtown walkability, and even transform some of these spaces into vibrant destinations. Fortunately, there are already proven models in place to help giude the way. Here are some Center City projects that illustrate the transformative potential of thoughtful, site-specific alley interventions.

1700 Moravian Street

Location: Moravian Street between 17th & 18th

Features:

· Café seating at the intersection

· Mural graphics on blank walls

· Overhead market lighting

· Built-in partitions to conceal dumpsters

1300 Drury Street

Location: Drury Street between 13th & Juniper

Features:

· Alley trash compactor (no dumpsters)

· Security gate with tenant-only access

· Curbside planters and landscaping

1200 Cuthbert Street

Location: Cuthbert Street between 12th & 13th

Features:

· Public art suspended over alley

· Funded by the Percent for Art program

East Market

Location: Ludlow Street between 11th & 12th

Features:

· Redesigned alleys with programming

· Overhead lighting, curbless pathways, seating and tables

· Below-surface waste storage

1900 Moravian Street

Location: Moravian Street between 19th & 20th

Features:

· New streetscape with construction of The Laurel

· Flush curbs, new paving and lighting

· Interior waste storage

Building the Path (or Alley) Forward

At first glance,our alleys can seem like an intractable problem: messy, neglected, and impossible to change. But if there’s one idea we want to leave with you, it’s this: transforming our alleys is more achievable than it appears. That belief has been the driving force behind this study. Yes, we have too many dumpsters. Strategies like replacing them with trash compactors or consolidating waste services are important, and perhaps the long-term solution. But let’s solve the problem that's in front of us today. By focusing on keeping dumpsters closed, clean, and well managed, we can drastically reduce visual pollution, enhance the public’s view of Center City, and create momentum and opportunity for larger, systemic improvements. The following tiers of intervention outline a path to achieving that goal:

Outreach and Engagement

The first step in addressing alley issues is raising awareness among business owners about proper dumpster maintenance practices. City agencies are already taking action through regular monthly inspections and business engagement initiatives.

Secure Dumpster Lids

A simple, low-cost preventative measure: locking dumpster lids helps keep alleys clean. This is an easy step that any dumpster license holder can take.

Update Dumpster Regulations

Amend the City code to support more practical and enforceable standards. For example, mandate that lids be “locked” rather than simply “sealed” or that dumpsters be setback a certain distance from intersections to avoid litter spill-out from alleys.

Consider Dumpster Consolidation

In alleys with sufficient space — whether on the sidewalk, along the cartway, or in an unused parking spot — businesses and property owners can work together to invest in shared compactors. This approach reduces the need for individual dumpster licenses and streamlines waste management.

Consolidate Waste Hauler Services

Explore policy consolidating commercial waste collection by issuing area-specific contracts in Center City via an RFP process. This would reduce truck traffic, improve efficiency, and enhance the overall quality of service.

Reinvest in the Alley Network

Identify alleys for strategic capital improvements, public art, and programming. With the right partners, these underutilized spaces can become vibrant connectors between commercial and restaurant corridors, enhancing one of Center City’s strongest assets: walkability.

Unlock Real Estate Potential

Clean, well-managed alleys can boost foot traffic, attract retailers and residents, and strengthen the overall investment appeal of the area, ultimately adding value for property owners.

The work has already begun. Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration has launched monthly alley walk-throughs, where teams from the Philadelphia Police Department, Licenses and Inspections, and Sanitation are talking with business owners, spreading awareness about dumpster regulations, and beginning the slow but vitally important process of enforcement. Early results from this initiative are promising. Following the start of inspections, a sample survey of two target alleys revealed positive changes: one showed a marked increase in sealed or locked dumpsters, leading to reduced litter, while the other saw a rise in visible identification labels that had previously been absent. This is a small but telling sign that information sharing and consistent outreach can spark meaningful action.

That’s the spirit behind this work: to help set the stage so that by 2026, when visitors come from across the country and around the world to celebrate Philadelphia’s story, our alleys can proudly be part of it.

This report was researched and written by Andrew Jacobs, Director of Planning and Urban Design. The Reclaiming Alleys report team also includes Jessie Brain, Manager of GIS; John Crichton, Senior Manager of Public Safety Operations; Bryant Gosnell, Graphic Designer; Jinah Kim, Urban Designer; David Orantes, Art Director; Samantha Rosenbaum, Streetscape Manager; and Emma Witanowski, GIS Intern.

Report Team Photography Credit

On-the-ground alley photos: Kendon Photography (Kat Kendon)

Drone photography by Chris Rivera Photos (Chris Rivera)

"Hosier Lane Melbourne" by Bernard Spragg is marked with CC0 1.0.

"Vancouver's Public Spaces" by Public Spaces and Streets is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

"Forgotten Songs" by Theen Moy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

"Parkers Alley, Detroit, MI" by w_lemay is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.