Heritage in Wales

Walking the Snowdonia Slate Trail: a journey of discovery

Why heritage is good for you: the well-being benefits it brings

Wartime Wales: the work to protect our built heritage

Holding court and castle: a Custodian’s life at Tretower

What’s on: Cadw events

Days to remember …

Join us this spring and summer for an action-packed programme of events at our historic places across Wales.

From medieval battle re-enactments and living history displays to willow weaving and book binding, there’s something for everyone.

Enjoy daytime walking tours or night-time bat walks. Develop new skills in calligraphy, needle felting or landscape painting. Hear the authentic sounds of medieval and Tudor music or listen to storytellers regale the historic tales of Wales. Take part in an archaeology open day or learn about medieval medicine. Or simply experience nature at its best with breathtaking falconry displays.

For a full list of events, visit cadw.gov.wales

Croeso i Heritage in Wales

I am sure that, like me, you are all looking forward to the warmer weather and a chance to explore the outstanding heritage that Wales has to offer. The new CadwHandbook, which you will have received with the magazine as a key benefit of your membership, will help you plan days out at our historic monuments by providing helpful information to make the most of your visit.

The article on page 30, ‘Heritage is good for you’, goes a long way to show that heritage plays a key part in improving people’s individual well-being and in building stronger communities. It really does inspire a visit to one of our historic sites! Furthermore, the article on Tretower Court and Castle showcases the daily work of Cadw’s hardworking custodians (p. 8). Our long-serving custodian, Ian Andrews, demonstrates that their work is so much more than the warm welcome they provide to visitors.

This latest edition of Heritage in Wales contains the usual mix of Cadw-led projects and those that we have supported as key partners. In November 2024, I was asked to announce the winner of the Outstanding Achievement Award at the Council for British Archaeology’s Archaeological Achievement Awards. I am sure that you can imagine my pride when I read out the name of the award winner — the Bryn Celli Ddu Public Archaeology Project, which features Cadw as a lead partner (p. 4).

Several other projects included in this edition have been led by others but have received significant support from Cadw — either through financial grants or through advice and encouragement from senior Cadw

officers. The ironworks and fossil forest at Brymbo, near Wrexham, is one such example that has received both. Cadw is a formal partner on the co-ordination group for this major heritage project, led by the Brymbo Heritage Trust, and played a key role in getting the project underway. Although the National Lottery Heritage Fund is providing the bulk of the funding, Cadw has also contributed critical financial support for the conservation of several of the key structures associated with the historic ironworks (p. 23).

Cadw also continues to play a key role in the ongoing partnership for managing Wales’ most recently inscribed World Heritage Site — the Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales. Our very own staff member, Cheryl Cracknell, shares her rewarding experience of walking the Snowdonia Slate Trail (p. 14).

The extraordinary range of work undertaken by Cadw is illustrated by the Minecraft project (p. 20), which brings together heritage and digital technology to support an educational resource that will engage young people with Cadw sites in an innovative and exciting way. It is particularly pleasing to see the Welsh language feature so prominently and, already, the interest from schools throughout Wales has rewarded the effort of the team involved.

I plan to step down from my role as Head of Cadw later this year to focus on major projects at our outstanding monuments. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank you for your ongoing support and making it possible for us to continue to conserve and safeguard Wales’ special heritage.

Diolch

Gwilym Hughes, Head of Cadw.

1 Welcome

Gwilym Hughes, Head of Cadw, welcomes you to this edition of Heritage in Wales

4 News

We look back at the success of the Bryn Celli Ddu Public Archaeology Project winning two awards at the prestigious Archaeological Achievement Awards in 2024 and look forward to the hugely successful Open Doors festival in September 2025.

8 Holding court (and castle)

Ian Andrews, Lead Custodian at Tretower Court and Castle, shares 15 years of memories of his role working at a historic site that has grown and developed into a well-loved visitor attraction.

14

Walking the Snowdonia Slate Trail

Follow Cadw staff member Cheryl Cracknell as she explores the Snowdonia Slate Trail, taking in a wealth of wonders both ancient and modern on a 10-day journey of discovery.

20

Minecraft

Education and Cadw join forces to build interest in Welsh heritage

Enter the digital world of Minecraft Education and discover how it is being used to enable young people to learn about our heritage as they travel back through time.

23

Brymbo: the 314-millionyear-old origins of an industry unearthed

Ashley Batten, Cadw’s Inspector of Ancient Monuments and Archaeology, explores the fascinating history of Brymbo Ironworks and the remnants of a lost world that lies beneath its ruins.

28

A spotlight on… Talley Abbey

Visit this tranquil abbey in its valley setting, located at the head of two lakes.

30

Heritage is good for you

Polly Groom, Cadw’s Historic Environment Outreach and Engagement Manager, reveals the research that backs up the long-held belief that the historic environment is of great benefit to our physical and mental well-being.

34

‘This old castle has stood for nearly a thousand years. I don’t suppose Hitler will knock it down tonight.’ The work of the Ancient Monuments Advisory Board in wartime Wales.

Jon Berry, Cadw’s Senior Inspector of Ancient Monuments, reveals the work of Cadw’s predecessor organisations as they endeavoured to protect our built heritage at a time when Wales’ historic sites faced risk, destruction or service through two world wars.

40

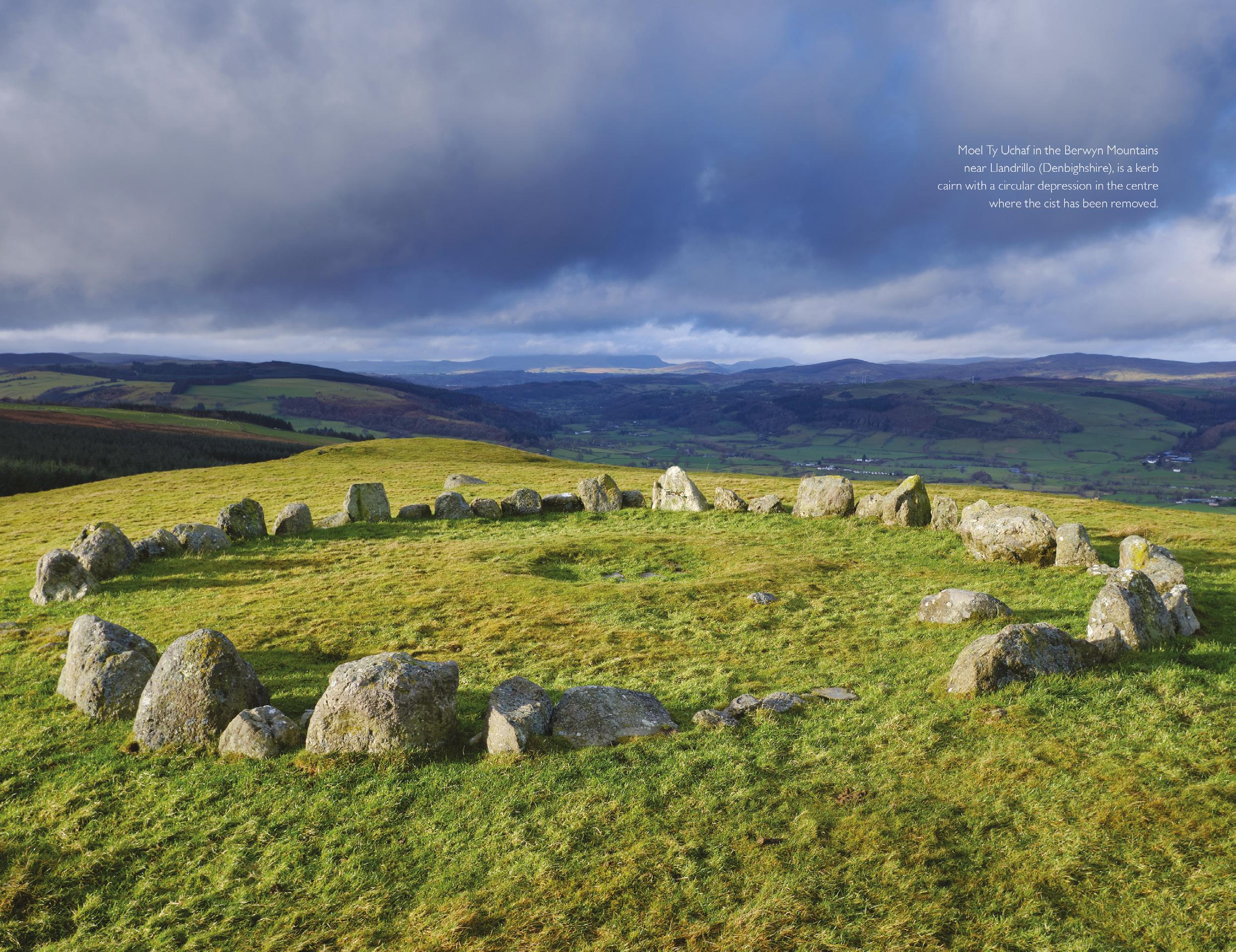

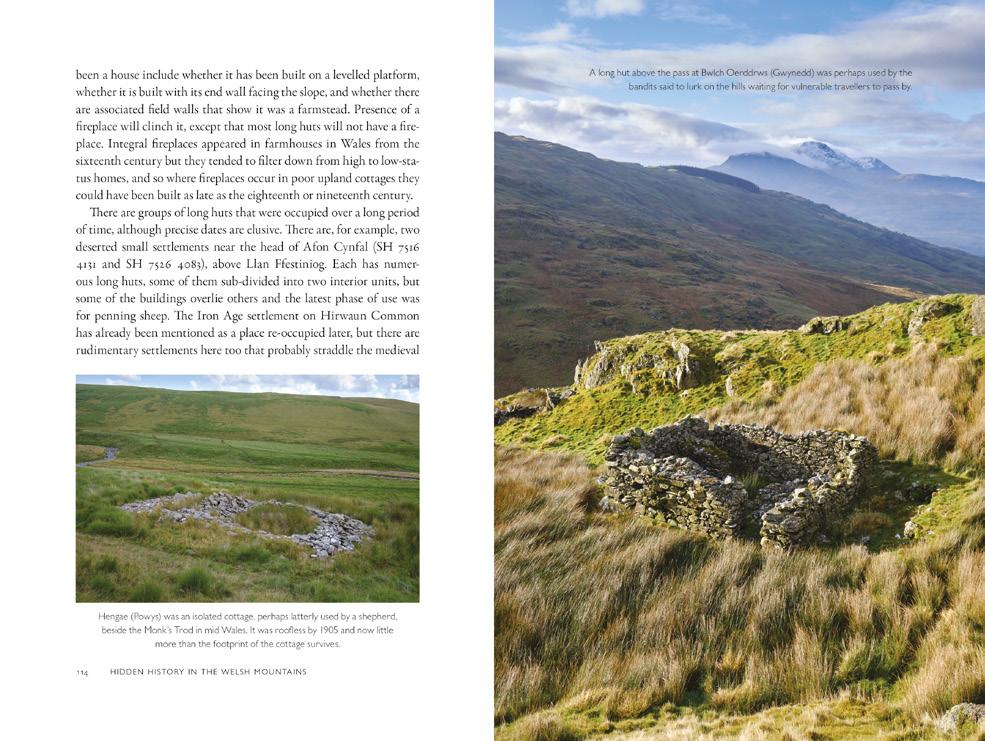

Book offer: Hidden History in the Welsh Mountains by

Richard Hayman

The mountains of Wales might seem like an uninhabited wilderness, but they are alive with evidence of our presence from the earliest days of human occupation. Discover more in Hidden History in the Welsh Mountains, available to Cadw members at a reduced price.

42 Members’ area

Complete the Cadw crossword to be in with a chance of winning a £250 gift voucher for Welsh Connection, and read what people are saying about our historic sites on social media.

The Bryn Celli Ddu Public Archaeology Project wins two awards

Cadw is delighted to announce that the Bryn Celli Ddu Public Archaeology Project won the Outstanding Achievement Award and the Engagement and Participation Award at the Archaeological Achievement Awards 2024, coordinated by the Council for British Archaeology (CBA).

The Archaeological Achievement Awards are a showcase for the best in UK and Irish archaeology and a central event in the archaeological calendar. They encompass five awards and an overall Outstanding Achievement Award, celebrating every aspect of archaeology and its contribution to society and environmental sustainability.

The awards are committed to recognising significant contributions to archaeological knowledge and research, the effective dissemination and presentation of archaeological knowledge, the involvement of local communities and a focus on sustainable approaches.

The public archaeology project — Gwreiddiau (Roots) — centred on Bryn Celli Ddu Chambered Tomb on Anglesey, is in its tenth year. It is a cross-disciplinary, outdoor, arts and heritage project, offering an opportunity to respond to the passage tomb through archaeological excavation, folklore and performance, exploring its histories and ritual through a contemporary lens.

Cadw, in collaboration with Think Creatively, a Welsh inclusive arts Community Interest Company, and

partners, engaged with local communities on Anglesey and Gwynedd through a series of artist-led workshops, providing opportunities for participation and creation. This led to a summer solstice performance celebration at Bryn Celli Ddu, exploring old and new connections to the land.

Bryn Celli Ddu (the ‘Mound in the Dark Grove’) is a remarkable and mysterious structure. Beneath its large mound, an entrance passage leads to a polygonal stone chamber where artefacts including human bones, arrowheads and carved stones have been found. Bryn Celli Ddu is the only tomb on Anglesey to be aligned with the rising sun on the longest day of the year, when shafts of light penetrate down the passageway to light the inner burial chamber at dawn.

In June 2024, Bryn Celli Ddu Chambered Tomb on Anglesey hosted a living history and folklore event to celebrate the project ’s tenth anniversary.

Right: The anniversary event included a colourful folklore procession.

Open Doors, September 2025

Open Doors is our national celebration of Wales’ built heritage, funded and organised by Cadw. 2025 marks the twelfth year of this popular festival, offering a variety of events and guided tours with free entry at over 200 historic places, landmarks and hidden gems across Wales. Here’s a taste of what to expect …

Barclodiad y Gawres Chambered Tomb, Anglesey Rhys Mwyn has been a guide at the Open Doors events at Barclodiad y Gawres, the Neolithic passage tomb on Anglesey, for over 10 years. He considers it a huge privilege to be able to share what we know about this exceptional monument and to welcome people into the chamber with its six carved stones.

There is so much that we do not know and understand about burial practices during the Neolithic period, and this is why Rhys adopts a conversational approach when guiding people around. He feels that visitors appreciate the opportunity to offer their thoughts, discuss possibilities and get to grips with the monument in a more hands-on way rather than being part of a formal tour.

‘In past years,’ he says, ‘we have had many interesting thoughts, sometimes ideas that I have never even considered. There is never a dull moment! On average, each tour lasts an hour in the tomb, but I have often found that 90 minutes has passed without anyone noticing.’

Cathays Cemetry in Cardiff commemorates over 700 servicemen who lost their lives during the world wars. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission will give tours of the cemetry as part of the Open Doors programme in September.

Archaeologist and presenter, Rhys Mwyn, gives guided tours of Barclodiad y Gawres Chambered Tomb on Anglesey as part of the Open Doors festival.

Barclodiad y Gawres Chambered Tomb occupies a spectacular coastal location overlooking Cable (Trecastell) Bay.

Local history with a global focus

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission is the global organisation established in 1917 to maintain the graves of those men and women who fell in the Great War. Today, they commemorate more than 1.7 million Commonwealth men and women who lost their lives during both world wars — in 23,000 locations in 150 countries and territories across the globe.

The Commission first became involved in the Open Doors programme in 2023 when they welcomed visitors to Cathays Cemetery in Cardiff. Their biggest site in Wales, Cathays is the final resting place of over 700 servicemen from as far away as Norway, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, France, Canada and Australia.

During the First World War, Cardiff was the headquarters of the third Western General Hospital, taking casualties from all regiments stationed on the Western Front. Whilst half of the casualties commemorated in Cathays Cemetery have some connection to Cardiff, the remainder do not.

The life stories of individuals feature heavily in the Commission’s tours. Private John Young Laing, for example, was the first soldier to be buried in what would become their First World War plot. He was a regular soldier from Kirkcudbright in Scotland who had joined the 1st Battalion Black Watch in January 1913. He fought with the British Expeditionary Force in France before being wounded in a bayonet attack and evacuated to the UK. He died in November 1914, aged 21.

In 2024, new tours of St Woolos Cemetery in Newport and Danygraig Cemetery in Swansea were added to the Open Doors programme.

At the Danygraig tour, a letter written by an Australian soldier to his mother was read out and those present listened to the bagpipe music that was played at his funeral.

In 2025, the programme will be extended to include tours of Wrexham and Porthcawl cemeteries.

In the 80th anniversary year of VE and VJ Day, come along and learn about the local heroes buried in your community.

Stori Brymbo, Wrexham 314 million years ago, Wales was a drastically different landscape. If you travelled back in time to this era, you’d feel light-headed due to the much higher oxygen levels and the hot, humid climate. You’d find yourself in a dense, unpassable blend of swamp and rainforest inhabited by enormous, insect-like creatures. Dominating this vast expanse would be towering horsetail plants and strange lycopsid club-mosses, their primitive leaves covering tall, telegraph-pole-like trunks.

While it’s impossible to step into this extraordinary era of earth’s history, Stori Brymbo, an emerging heritage attraction in north Wales, offers the next best thing (see pp. 23–27). An in-situ fossilised forest dating back to the Carboniferous period was discovered next to the Georgian ironworks during reclamation works in 2001. The forest was adopted by Brymbo Heritage Trust and, today, part of the site is protected by a building that will allow the exploration, excavation and interpretation of the fossils within.

The site is open to the public, with knowledgeable guides offering immersive tours that delve into the

A 314-million-year-old giant lepidodendron stump discovered in a fossilised forest at Brymbo Ironworks, near Wrexham.

Visitors to the Open Doors event at Stori Brymbo will have the chance to see new discoveries, such as this thicket of calamites preserved in the fossil forest.

The grave marker of John Young Laing in Cathays Cemetry, Cardiff.

ancient ecosystems and the remarkable species that once flourished there. Visitors have the unique opportunity to talk to the excavation team and witness ongoing palaeontological work up close, with a chance to see new discoveries as they happen. The site also features hands-on learning activities, allowing visitors to engage directly with the process of uncovering and interpreting scientific findings, as well as informative displays and interpretation.

• The Brymbo fossil forest will be open on Saturday 6 September as a Cadw Open Doors event.

St Michael & All Angels Church, Lower Machen, Newport

Grade II* St Michael & All Angels, dating from 1102, is one of Wales’ hidden treasures. The church has been inextricably linked with the Morgans of Machen, Ruperra and Tredegar for over 500 years, many of whom are buried in the church. Next to the church is the privately owned Grade II* listed Machen House, built in 1831 by the Tredegar Estate as the rectory for the Revd. Augustus Morgan, the younger brother of the first Lord Tredegar.

Cadw has provided the church with funding and advice which has supported a seven-year conservation programme, the latest phase of which focused on the fifteenth-century bell tower. The church is unique in holding the largest collection of hatchments — diamondshaped tablets bearing the coat of arms of someone who has died — in their original location in Wales.

Cadw Open Doors visitors can now enjoy the beautifully restored chantry chapel, dating from 1710, with its exceptional collection of monuments. Highlights include the large, double memorial to Sir William Morgan (1700–31) and his wife Lady Rachel Cavendish (d. 1780) and his parents, John Morgan of Tredegar and Martha Vaughan.

The hatchments and monuments within the church have been researched to tell the stories of the Morgans

— from their involvement in the armed forces, politics, law and international trade in the seventeenth century to all aspects of industrial development in south-east Wales. These histories can be accessed via an audiovisual tour available on your smartphone. Guided tours are also available if booked in advance of a visit.

• If you work or volunteer at a site which is interested in taking part in Open Doors 2025, we would love to hear from you. Please email OpenDoors@gov. wales for a registration form. Alternatively, you can volunteer to help out at a historic place that is taking part in Open Doors in your community.

• All events will be listed in the Open Doors section of the Cadw website — cadw.gov.wales Keep checking as sites will continue to be added throughout the registration period.

• Cadw sites taking part this year will include Llanthony Priory, Monmouthshire.

During

the Open Doors festival, around 1,000 volunteers welcome approximately 50,000 visitors to their heritage sites each year.

Open Doors 2024 consisted of 616 events at 200 different historic places.

Above

Twelfth-century St Michael & All Angels Church, Newport, will open its doors to visitors as part of the Open Doors programme of events. © Tom Hannigan. Left

St Michael & All Angels Church holds the largest collection of hatchments in their original location in Wales.

Holding court (and castle)

It is 15 years since Tretower Court and Castle were reopened after major interpretation work. Lead Custodian Ian Andrews has been at the monument since then, overseeing another major development in visitor facilities. The remarkable buildings tell the story of 900 years of life and almost a century of welcoming visitors…

Ian Andrews comes smiling from the room behind the counter, offering a mug of freshly made coffee and starts to chat. Above us is the high open ceiling of the recently renovated medieval barn which now houses the visitor centre at Tretower Court and Castle, with its spacious shop and welcoming desk.

For the Lead Custodian here, this is luxury. Not only does the site tell the 900-year story of the families who lived here, it also shows how the welcome for visitors has improved over the past 90 years and, especially, in the 40 years since Cadw was established.

In the grounds, just beyond the rectangular late-medieval house, is the bungalow that was built for the first-ever Custodian, Leo Moore, a former army veteran and, by all accounts, a great raconteur. He brought up his family here and carefully recorded the tiny numbers of visitors that called by in the 1930s and 1940s. The cottage is now one of Cadw’s collection of holiday lets.

For many years, the entrance into the court was through the narrow postern gate, the welcoming facilities being no more than a tiny green shed; inside the courtyard even now, you can still see a later reception building, a glorified cabin a few steps up from the ground. The barn, with its feeling of space and light and well-organised displays of gifts, is a revelation — a fitting introduction to a remarkable set of buildings.

While Leo Moore was on his own, Ian Andrews now has a team of four custodians — as many as three on duty on a particular day. The new visitor centre has added another dimension to their work and has also made the site an even more attractive proposition for the couples who decide to get married here.

Weddings and Tretower’s appeal as a site for filming — from featurelength movies, to reality TV series — means that custodians are now far more than gatekeepers; they are hosts and facilitators and, at Tretower and many other sites, have a valuable role in bringing the place to life.

A little later, Ian Andrews is sitting in the colourful great hall, describing the work that went into renovating and renewing this ceremonial space 15 years ago, when it was dressed with re-created furniture and fabrics to represent the setting of a feast in 1471. Ian is completely at ease describing the scene as the household prepared for their lord’s return from battle. ‘As it happens, Sir Roger Vaughan never returned. He was killed following the Battle of Tewkesbury. But his family would have been expecting him back, here on the top table … down there would be his retainers, poorer people,

Images

1. Tretower Court was begun by Sir Roger Vaughan in the 1450s and was subsequently home to 11 generations of his family.

2. An aerial view of the converted fifteenth-century barn in the foreground, with Tretower Court and the castle beyond.

3. The heart of the home: the great hall, dressed as it might have appeared in 1471.

4. Lead Custodian, Ian Andrews, giving a guided tour of the court.

5. Tretower Court Cottage, once home to Leo Moore, is now a holiday let owned by Cadw.

woodcutters, potters and the like; he’d be thanking them for their support. The family would have the best cutlery and dishes, these people would have local pottery and wooden trenchers and spoons.’

It’s obvious that he loves this part of a custodian’s role, taking tours of visitors around the site, both the twelfth- and thirteenth-century castle and the house itself. His lifelong love of castles, the benefit of attending a school with a headmaster who was an archaeologist, and his later career as an actor, stage manager and theatre licensee have placed him in good stead for his role as guide and animateur. His passion for the Wars of the Roses (1455–85) makes this the perfect post.

‘I’m a Yorkist by inclination,’ he says, with the fervour of a die-hard football fan. ‘And remarkably,

this was a Yorkist house in what was part of the Duchy of Lancaster — despite the family’s ancestor, Dafydd Gam, having fought with the Lancastrian Henry V at Agincourt.’

That story, and Dafydd Gam’s death in the battle, supposedly saving the king’s life, is depicted on the re-created tapestries behind the great hall’s top table. That was the event that set the Vaughan family apart, the basis for their later renown and helped make Sir Roger Vaughan — the first of the Vaughans to occupy Tretower — one of the richest and most powerful commoners in Wales. In his day, the great hall was the pulsating centre of the house; today, it is still the historical heart of the court.

‘This is where we sit and answer questions,’ says Ian. ‘I point out the various bits around the room — things that mean something today,

like the tenterhooks which were used to hang the tapestries or the taper which gave us the saying about burning the candle at both ends. Those kinds of facts are actually more important to most of our visitors than the architecture.’

Even royal visitors love Tretower. In 2019, the then Prince Charles and future king made a special request to visit. Given a tour of the site by Head of Cadw, Gwilym Hughes, and Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Will Davies, he too ended up in the great hall chatting to Ian Andrews and showing

Images

6. Dressed in historical costume, Ian gives a guided tour to a group of visitors.

7. King Charles visited Tretower Court and Castle in 2019.

8. The painted cloth behind the high table depicts the history of the Vaughan family.

his extensive knowledge of the age of the Wars of the Roses. The one thing Ian forgot to ask was whether he had a preference for York or Lancaster! What fascinated King Charles is what sets Tretower apart: the sweep of history here and how the story can be read in the buildings … how the castle’s strategic position led to the house, how a change in the family’s fortune turned the once palatial court into a working farmhouse, occupied up until the 1930s. One of Ian’s favourite features is no more than a doorway that doesn’t seem quite to fit: proof that wood was moved from somewhere else in the house as a patch-up job. He can also point to the daisy-wheel patterns left by medieval plasterers as a sign of good luck. ‘That’s a piece of humanity.’

People can imagine living at Tretower. They can see where work has been done. Where the lower part of a beam is more heavily smoke-stained than its upper parts (the two parts delineated by a row of holes), it can indicate that a later ceiling was added. People can see the progression. They can see how the place developed.’’

The tours usually start in the original castle outside. Built near a crossing of the river by a Norman family called the Picards, it also commanded the meeting point of two valleys, east and west to Crickhowell and Brecon, northwards to Talgarth. Again, the castle’s story is clear in the building itself. It started as a motte-and-bailey castle at the end of the eleventh century, with its wooden tower replaced by a stone shell keep after 1150. About a century later, a formidable round keep was built inside the other; marks in the masonry and the remains of stairs and windows today show how the two would have integrated. Inside the main tower, ledges and windows and fireplaces show how it was laid out and adapted; the second-floor solar provides an immediate connection with a similar family room in Tretower Court.

Glyndŵr, despite the family’s loyalty to the English crown and despite the destruction at nearby Crickhowell, Tretower remained unscathed.

In contrast to other modest castles of its kind, the main towers weren’t plundered for building materials either; the village buildings were likely to be built in stone by the seventeenth century, so the only use for the castle materials was in the construction of the attached farm and some later repairs to the court.

10.

Another remarkable link is in the survival of the two buildings. Despite being caught up in the wars of Owain

The court too avoided destruction or major reconstruction, even during the Wars of the Roses and the English Civil War (1642–51). Although the development of the house and the various additions can be clearly seen, the basic building remains. It was adapted and put to different uses but, when local people campaigned to have it taken into state custodianship in the 1930s, they helped save a rare example of an early fortified house.

Images

9. Tretower Castle was first built around 1100 by the Norman adventurer, Picard. Pictured is the great round tower surrounded by the earlier shell keep.

The two domestic ranges of the court seen from the courtyard.

As we cross what would have been the bailey and middens from the castle to the house, Ian Andrews again points out the way differently dated windows tell the tale of adjustment and adaptation. We round the early west range and the great hall and enter again through the re-created gardens and the avenues of rose bushes — Yorkist white flowers, of course. We are back in the flow of the house, moving through the kitchen and back to the great hall. And the Lead Custodian is back in his element, bringing the place to life.

‘‘Smell,’ he says. ‘That’s one thing we have to explain. We can see people in costume or the tables laid out for a feast, but we can’t bring back the smell. In the fifteenth century, people weren’t washed in the way we are now. The smell of burning wood, decaying matter, that’s the sort of thing we’d have great trouble with today. And outside in the middens, it’s open drains and animals.’

A feast would have been an exception, though. The richer people at least would have washed in preparation and would have taken out their best clothes, stored carefully with rosemary and other sweet-smelling herbs. And when the aromas were too powerful, they would have held a pomander to their noses. For the ordinary people, it was another story.

Another development was the Picards’ shift from being Norman

occupiers to being integrated into the fabric of Welsh life. Under their descendants, Tretower became an important cultural centre, attracting some of the greatest poets, like Lewis Glyn Cothi, to praise its hospitality and the greatness of its owner.

After the feast, the family would have retired to the adjacent solar. Their guests would have been on the first floor, where the north range has bedrooms and solars; although now open plan, Ian can point to the slits and marks where dividing walls would have been. Some of these rooms are obviously now used for wedding ceremonies.

We hold around eight or ten weddings a year. If couples come to see the court, they usually get married here. During Covid, couples delayed and delayed their ceremonies because they really wanted the wedding to be here. We’ve had couples get married in period costume even. They truly love the place.’’

A local farmer is happy to rent out a field for marquees: a sign of how the monument is part of valley life. Village meetings and fetes have been held here; local people recall playing here in the early days, even roller skating along the open north range.

We follow their route and turn into the gatehouse — once much higher — and look out over the refurbished barn and its visitor centre. One more range — a corridor and facade that pretend to be another suite

On site, on set!

If Tretower has seen real transformations, from castle to house to farm, the site has also been a tavern and in stories ranging from Robin Hood to pirates and even Dracula. All through TV and film.

One of Ian’s favourite programmes was the Welsh-language reality series, Y Llys (The Court), when a group of twenty-first century Welsh people tried to live like the residents of Tretower back in Tudor times.

When the house became The Boar’s Head tavern in the Shakespearean series, The Hollow Crown, visitors could wander around. On one side

of rooms — and we’re back down again in the kitchen and pantry and Cadw’s re-creation of the great hall.

For the future, as he himself nears retirement, Ian would love to stage another fully fledged feast and, if funds allow, would like a little more furniture in the bedrooms. ‘But not too much,’ he stresses, afraid that over-dressing and re-creation takes away the mystery and sense of discovery. It would lose the sense of a home and a stretch of time.

A day in the life

As Lead Custodian, Ian Andrews has less opportunity than in the past to welcome and guide the guests.

He now leads the team, on duty from shortly after 9am until up to 6pm. He will be in the background while one custodian welcomes people into the visitor centre and another provides an introduction at the gatehouse entrance.

There are regular tasks such as reconciling the cash in the shop and checking the house and grounds before opening and closing at night. There are other safety

was a realistic set, on the other, the scaffolding and open woodwork.

The Hollow Crown was filmed in the freezing cold of January, which is how a Cadw custodian ends up sharing the comparative warmth of his cabin chatting away with the wonderful Julie Walters.

Ian’s experience in acting, opera and stage management has been invaluable in dealing with television and film — he understands what they need, helping them to achieve their aims without harming the history.

The first film on his list is Restoration, back in 1995, exactly 30 years ago. And there are 30 major productions on the list … one a year on average since then!

‘Then, it would just be flat; it would just be there … and I’d have much less to say!’

Images

11. Part of

12. The first floor of the north range. Now a single, open space, it was originally divided into four chambers.

13. Weddings are

and security checks to be done throughout the day and the year.

Another daily task is dealing with e-mails and other requests and queries from the public, Cadw and other bodies. Using Leo Moore’s meticulous records, Ian was even able to tell a recent visitor the very day she had visited as a schoolgirl during the war.

Less regular but frequent are visits from couples considering getting married here and from film and television companies looking for locations, together with the numerous Cadw-arranged events which happen each year. They entail administrative work that Leo Moore could never have imagined.

Tretower’s recreated medieval garden, with its dripping fountain.

held in the west range of Tretower Court, dressed for the occasion.

Custodian, Rose Waters.

Tretower Court dressed as an Italianate courtyard (top) and a dormitory (above) in Da Vinci’s Demons

WALKING THE SNOWDONIA SLATE TRAIL

Tregarth

Caernarfon Y Felinheli

Deiniolen

Waunfawr

Plas y Nant

Snowdon Ranger

Garndolbenmaen

Porthmadog

Porthmadog

Garreg

Penrhyndeudraeth

Located in the heart of north Wales, the Snowdonia Slate Trail offers an 83-mile adventure through some of the most stunning landscapes in Wales. This circular route not only showcases the natural beauty of Eryri (Snowdonia), but also tells the story of the region’s rich slate-quarrying heritage. Cheryl Cracknell, a member of Cadw’s digital team, reflects on her unforgettable experience of walking the slate trail, a 10-day adventure that exceeded her expectations.

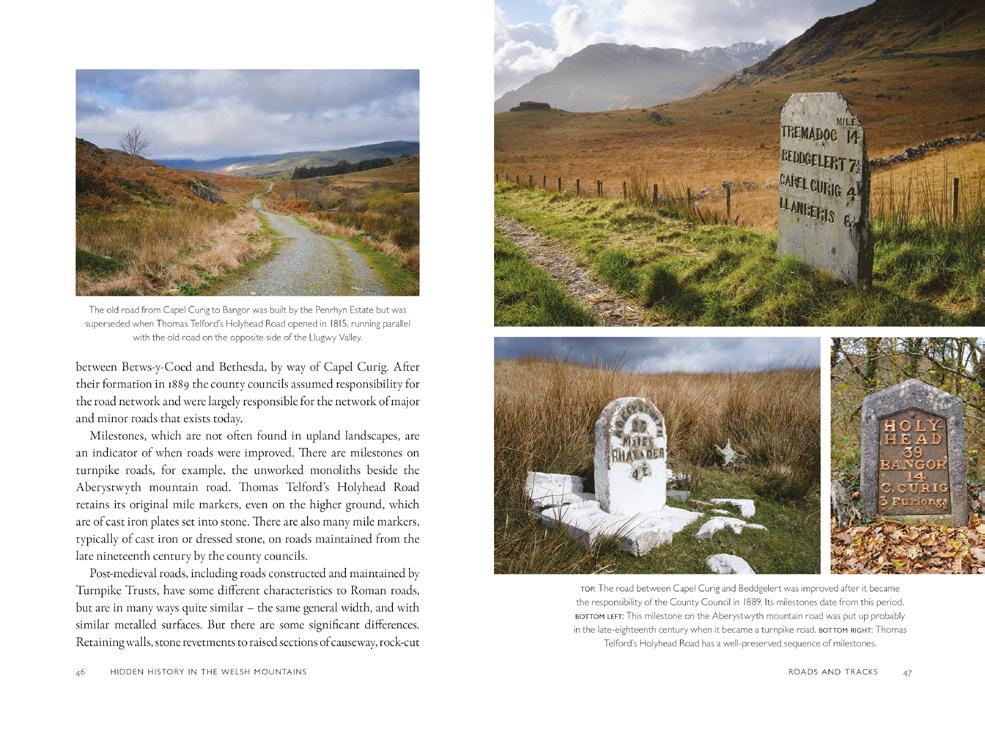

Starting in the historic city of Bangor at Penrhyn port, the trail initially follows the route of the disused narrowgauge Penrhyn Quarry railway line, then winds through picturesque villages, ancient woodlands and past remnants of the once-thriving slate industry. Each step along the trail is a step back in time, offering glimpses into the lives of the quarry workers who shaped the landscape. The abandoned quarries, old tramways, inclines and ruined buildings serve as poignant reminders of the region’s industrial past.

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

Section 5

Section 6

Section 7

Section 8

Section 9

Section 10

Section 11

Section 12

Section 13

source: Snowdonia Slate Trail

Llanrwst Dolwyddelan

Images

1. The derelict ruined buildings of Rhosydd Quarry, near Tanygrisiau. Occupying a remote location between two mountain valleys, the remains include barracks for the quarrymen.

2. The trail begins in Bangor where it follows the old Penrhyn Quarry railway line. The arched bridge carries the active north Wales railway.

Blaenau Ffestiniog

Blaenau Ffestiniog

3. The refurbished, gravity assisted, railed V2 incline at the National Slate Museum, Llanberis, served the Vivian Quarry. The loaded wagons going downhill pulled up the empty wagons.

4. Vivian Quarry, Dinorwic, Llanberis, was worked on a gallery system whereby the slate was taken from stepped working levels cut into the hillside at regular intervals.

5. Cheryl walking towards Croesor village following an old coach road along the rugged landscape.

6. An upturned slate wagon abandoned at Croesor Quarry.

7. Rhiwbach Quarry buildings, located in a remote spot between Cwm Penmachno and Cwm Teigl. The site is dominated by the engine house, with its tall squareplan chimney stack.

8. An incline and slate waste tip forming part of Tan y Bwlch Quarry, near the village of Rachub, Bethesda.

9. Castell Dolbadarn, Llanberis, with far-reaching views of the Dinorwic slate quarries.

From Croesor Quarry, the walk to reach Rhosydd and Cwmorthin quarries crosses high, bleak moorland and passes over the remains of the Llyn Croesor dam. On my approach, the mist rolling in over the ruins of the Rhosydd mill and barracks’ buildings was very atmospheric. Quarrymen lived in the barracks near the quarry and mill as it was too far for them to commute from the nearest villages and towns. There is even a chapel, known as Capel y Gorlan, located along the pathway up the hillside, 1.5 miles from Tanygrisiau village, but this is now in ruins. Images

The trail passes through key sites such as Dinorwic Quarry, Llanberis, now home to the National Slate Museum (currently closed), and Penrhyn Quarry, Bethesda, once the largest slate quarry in the world. Some disused areas of Penrhyn are now given over to Zip World, but other parts are still being quarried today.

There are so many quarries along the trail — too many to list here — but the ones that particularly stood out to me were the quarries located in remote, high-up locations, in particular Croesor, Rhosydd and Cwmorthin quarries.

Reached by a long but steady hill walk from Croesor village below, Croesor Quarry is known for its manager Moses Kellow. He ran the quarry from the mid-1890s until its closure in 1930. Kellow was famous for his remarkable engineering achievements and inventions, including the waterdriven Kellow drill and the introduction of hydrogenerated electricity into the quarry works.

A few slate quarries in Eryri are still being worked today, including Cwt-y-Bugail near Cwm Penmachno. Cwt-y-Bugail’s underground mines were used to store valuable British paintings during the Second World War. A short distance away, the trail descends one of the inclines to Rhiwbach Quarry buildings. Standing at the top of the incline, the wind was so strong that I was very nearly knocked off my feet. It gave me a sense of the harsh conditions faced by the quarry workers and the communities that grew up around the industry in such exposed, isolated places.

As I ventured further along the trail, the countless number of slate tips and inclines spread across the landscape revealed just how many quarries and mines there are. Some are cut into the hillsides and easy to see, while others are underground with their spoil tips outside — the only clue to their existence and, in turn, their immense size.

The multitude of inclines used to transport the slate down the hillside to the trains and tramways below, waiting to take the slate onward to locations across the world, is impressive.

In addition to the industrial heritage, the trail takes in earlier historic sites. Part of the walk follows the Sarn Helen Roman road near Llan Ffestiniog, and a short distance from the trail at Llanberis is Castell Dolbadarn — well worth the diversion for its stunning views over Llyn Padarn and Llyn Peris and the Dinorwic slate quarries on the far side.

In 2021, the Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This prestigious recognition highlights the global significance of the region’s slate industry and its cultural landscape. The slate trail passes through several areas of the designated site, including Dorothea Quarry and its surroundings, as well as the Cilgwyn and Pen Yr Orsedd slate quarries above Nantlle.

The designation celebrates the unique combination of natural beauty and industrial heritage that defines the area — from the dramatic quarry landscapes to the remains of slate-built villages.

The slate trail ventures through diverse terrains, from lush valleys and serene lakes to open moorlands with vibrant gorse and heather and Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Highlights include the stunning Afon Cynfal gorge, the Llugwy riverside walk past Swallow Falls, near Betws-y-Coed, and the views from Capel Curig looking towards the mountains of Eryri. The trail is a haven for wildlife enthusiasts, giving countless opportunities to spot various birds and other native species along the way.

One of the most striking features of the trail is its ever-changing scenery. As I moved from one section to another, I encountered a variety of landscapes, each with its own unique charm. The lush greenery of the Nantlle Valley, the open moorlands above Croesor, and the serene waters of Llyn Nantlle Uchaf, famously painted by Welsh landscape artist Richard Wilson in 1854, all contributed to the trail’s diverse beauty.

The sense of isolation in the more remote sections provided a rare opportunity to disconnect from the hustle and bustle of modern life. The added combination of physical exertion, natural beauty and historical significance created a powerful and thought-provoking journey.

The Snowdonia Slate Trail is a cultural journey as well as a physical one. The trail passes through areas rich in Welsh heritage, offering opportunities to experience local traditions, language and cuisine. The chapels and churches, band rooms, schools and libraries are evidence of respect for faith, education, literature and music. Fundamental to all is the Welsh language — the living language of our communities to the present day.

While the trail was very rewarding, it also presented its fair share of challenges. The weather in Eryri is unpredictable and the terrain varied from gentle paths to steep, hilly climbs and sections that were very wet underfoot. To complete the whole trail in one go is a big undertaking, but it can also be split into smaller, manageable sections with options for circular walks in some areas like Llanberis and Betws-y-Coed.

Walking the Snowdonia Slate Trail is more than just a hike: it’s an exploration of the natural and cultural heritage of north-west Wales. Whether you’re drawn by the promise of stunning landscapes, the allure of historic places or the challenge of the trail itself, the journey offers something for everyone. So, lace up your boots, pack your backpack and set out on an adventure that will leave you with lasting memories and a deeper appreciation for the beauty and history of Eryri.

Useful website links snowdoniaslatetrail.org — the Snowdonia Slate Trail website has lots of useful information, including a selection of walkers’ stories and testimonials. llechi.cymru — the Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales World Heritage Site. unesco.org.uk/the-slate-landscapeof-northwest-wales/ — UNESCO.

historypoints.org — there are QR codes located along the trail which you can scan on your mobile phone to learn about local history along the route. There is also a ‘Snowdonia Slate Trail tour’ in the Tours & Themes section of the website which you can read in the comfort of your home if you are unable to walk the trail. museum.wales/slate — Dinorwic Quarry is currently undergoing a major redevelopment project to conserve and renovate its Grade I listed buildings. It is due to reopen in 2026.

celtictrailswalkingholidays.co.uk — Wales-based provider of self-guided walking holidays, from customised itineraries, including route notes, maps and documentation, to booking quality accommodation. Other providers are available.

Planning your journey

Proper planning is essential for walking the Snowdonia Slate Trail. Here are some tips to help you prepare:

• Research the route: familiarise yourself with the trail’s sections and key landmarks. The Snowdonia Slate Trail website contains planning information and route descriptions. Knowing what to expect can help you plan your walks and ensure you don’t miss any highlights.

• Pack wisely: bring essential gear such as a goodquality backpack and walking boots, waterproof clothing, a map, a compass and a first-aid kit. Don’t forget snacks and plenty of water.

• Check the weather: the weather in Eryri can change rapidly. Check the forecast regularly and be prepared for all conditions.

• Stay safe: let someone know your itinerary and expected return time. Carry a mobile phone but be aware that the signal can be patchy in remote areas.

• Follow the Countryside Code: the trail passes through protected areas and fragile ecosystems. Stay on marked paths, keep a safe distance from quarry edges, dispose of waste properly and respect wildlife.

11.

12 All images © Cheryl Rose Photography

Images

10. St Mary’s Church, Beddgelert, is traditionally regarded as one of the oldest religious foundations in Wales.

A picturesque waterfall along the Afon Cynal gorge, near Llan Ffestiniog, is just one example of the stunning scenery along the trail.

12. The Snowdonia Slate Trail bench at Porth Penrhyn, Bangor.

Minecraft Education and Cadw join forces to build interest in Welsh heritage

What better way to mine curiosity and build fascination in something old than to stitch it together with something new? That’s exactly what we have done with the support of Microsoft’s Minecraft Education.

Minecraft is a 3D computer game consisting of virtual worlds made up of building blocks. Players can explore these worlds and build anything, from cities to roller coasters, across different environments and terrains. The game involves resource gathering, crafting items, building and combat.

Minecraft Education is a version of Minecraft which enables a world to be used for educational purposes. Developed in collaboration with historians, education practitioners and digital designers, Cadw Cymru is an exciting new Minecraft Education world which

cleverly merges the virtual realm of Minecraft with the rich history of Welsh heritage sites. The program recreates iconic Welsh heritage monuments within Minecraft Education, allowing learners to explore and learn about historical landmarks, including castles and abbeys, in an engaging digital format.

Cadw has also created a new Cadw Cymru Minecraft Welsh Language Resource Pack, designed to transform how learners in Wales interact with Minecraft Education. Wales is one of the highest users of Minecraft Education in the world and this will be the first time that children will be able to access this fun learning resource in Welsh.

The innovative downloadable Welsh resource pack transforms the entire Minecraft Education experience into a fully immersive Welsh-language adventure.

The east barbican and inner ward of Castell Conwy recreated within the Cadw Cymru world in Minecraft Education.

Every element has been carefully translated, from in-game language and menus to detailed inventory descriptions. This ensures that Welsh-speaking learners and fluent speakers alike can navigate and explore the game entirely in Welsh, making it inclusive. The pack offers education practitioners in Wales an exciting tool to engage learners with their national history in an interactive and immersive way.

The bilingual Minecraft version of Castell Conwy is the first Cadw monument to feature in the game, but the Cadw Cymru world will gradually expand to include many more Cadw sites, representing different aspects of Welsh history and culture. Each site will have its own virtual tour, together with a range of ‘Quest’ learning activities. Learners will be able to travel in time to find these historic sites rebuilt in Minecraft, making history tangible and interactive.

Minecraft’s interactive nature encourages collaboration among learners, allowing players to work together to solve historical puzzles, participate in role-play scenarios or even create their own reconstructions of Cadw sites.

Cadw Cymru complements the goals of the National Curriculum for Wales by promoting the development of a range of cross-curricular skills and competencies, integrating literacy, numeracy, STEM and digital competency into history lessons. The program encourages enquiry-based learning, an approach which aligns well with the curriculum’s focus on developing independent learners who can critically evaluate information and make informed decisions.

Top

Middle and bottom

The

Castell Conwy is the first Cadw monument to feature in the Cadw Cymru world, but a new location will be added every month until a total of 20 Cadw sites are included.

Cadw Cymru world was launched at Castell Conwy in December 2024, giving children who had previously helped to test the world, from Ysgol Pennant, Powys, and Ysgol Minafon, Conwy, the opportunity to be amongst the first to play the game.

How it works

• Cadw Cymru is hosted by Hwb, the Welsh Government Digital Learning Platform. Practitioners can download a Cadw Cymru Minecraft World map and a Cadw Cymru Minecraft World practitioner guide from the ‘Resources’ area on Hwb — hwb.gov.wales/minecraft/cadw-cymrubridging-welsh-heritage-and-digital-learning/

• Minecraft Education can also be downloaded from the Minecraft Education website — education.minecraft.net

• Learners can enter the Cadw Cymru world where Taliesin will invite them on a journey. They will then enter a Galeri, a gateway to Cadw sites around Wales.

• The virtual Cadw sites, each with their own digital tour, will allow learners to explore and interact at their own pace, providing an educational yet entertaining experience.

‘The team are constantly looking for ways in which we can make the heritage and culture of Wales relevant to a contemporary audience in an exciting and participatory way. We think learning should be fun and have developed a new Cadw Cymru world in Minecraft Education to ensure that it is.’

Sue Mason, Cadw, Head of Lifelong Learning.

‘This is a huge and innovative programme. Not only does it celebrate the heritage of Wales but, through accompanying resources and activities, it will inspire children to explore their own history and culture and hopefully to research and build their own versions of these historical sites.’

Jack Sargeant, Minister for Culture and Skills.

‘This is an incredible resource for both Welsh speakers and those learning the language. Minecraft is a fantastic tool for engaging learners. Now, with the Welsh Language Resource Pack, it’s an even more powerful way to connect young people with their heritage and language. It’s an exciting and fun way to learn!’

Manon Jones, teacher, Ysgol Pennant, Powys.

‘Minecraft Education is delighted by the continued innovative use of Minecraft within the classrooms of Wales. This project, which is particularly important to the topic of cultural heritage and science, shows that game-based learning can provide immersive and engaging curriculum experiences that are relevant to the National Curriculum for Wales.’

Justin Edwards, Director of Learning Experience, Minecraft.

As the Cadw Cymru world is expanded, each new site will be supported by a virtual launch and training sessions for teachers. The Castell Conwy launch involved an interactive classroom (pictured) and an opportunity for the schoolchildren to experience playing Minecraft Education on laptops provided (below).

An aerial view of the remains of Brymbo Ironworks today. Image courtesy of Brymbo Heritage Trust/ArchaeoDomus.

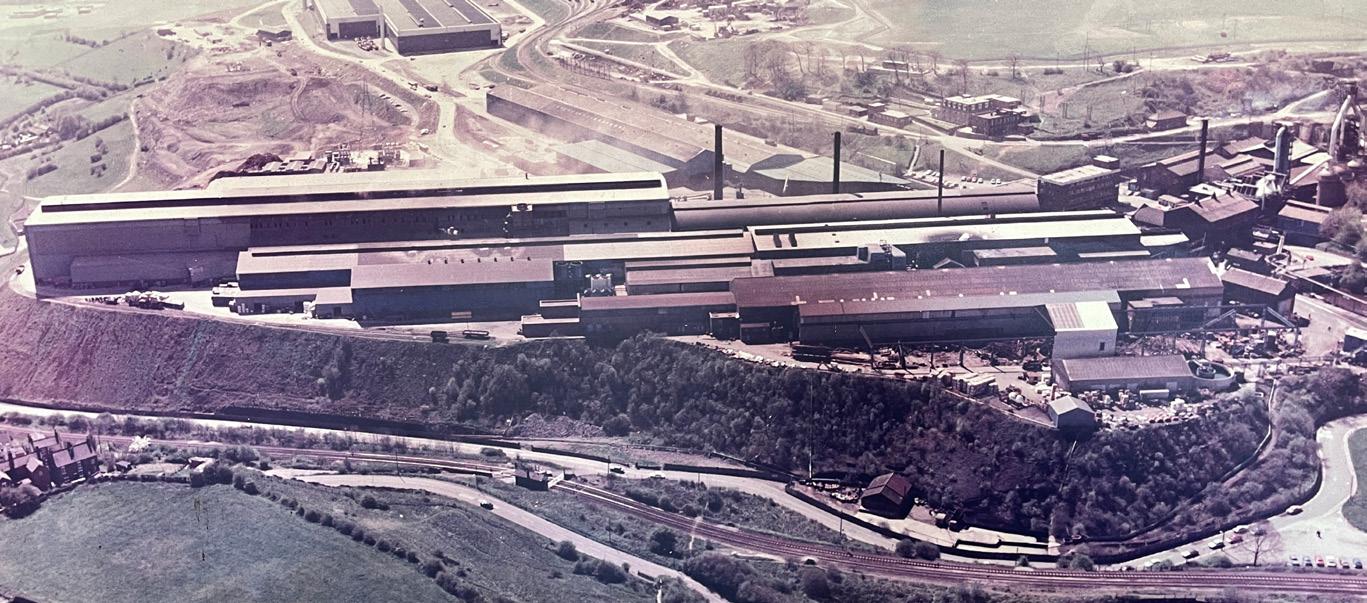

The people of Brymbo, Wrexham, are rightly proud of the rich industrial heritage of their village. Brymbo Steelworks was once the main employer for the area, and its vast complex saw 200 years of use and development before closing in 1990. However, a chance discovery made during land reclamation work in 2003 revealed that the mineral wealth that was the key driver for industrial activity was formed more than 300 million years earlier. Ashley Batten, Cadw’s Inspector of Ancient Monuments and Archaeology, sheds light on the fascinating history of this complex site.

The industrial history of the county of Wrexham is well documented. Mining in the region can be traced back to at least the medieval period, but the first records of coal being exploited on the Brymbo estate were in 1620.

The area became comprehensively industrialised in the 1790s when pioneer industrialist John Wilkinson — known for developing nearby Bersham Ironworks with his father — purchased Brymbo Hall and the surrounding 500-acre estate with the intention of exploiting the mineral reserves of the area. Over the next 15 years, an ironworks, lead smelting works and colliery were established before Wilkinson’s death in 1808.

In the 1840s, the ironworks became known as The Brymbo Company, owned by William and Charles Darby, descendants of ironmaster Abraham Darby. In the later nineteenth century, the Brymbo Steel Company was formed and continued to thrive until the First World War. Whilst the inter-war years were difficult for the industry, there was steady growth throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Significant investment led to an increase in output and even the demolition of Brymbo Hall in 1973 to enable the expansion of operations.

The steelworks closed in 1990, leaving much of the surrounding land in need of remediation and restoration. The important relict industrial remains were immediately recognised for their historical significance shortly after their operational life ended.

Brymbo Ironworks was designated as a scheduled monument to protect it for future generations. The nearby agent’s house was listed Grade II* and other features in the wider landscape were also afforded statutory protection by Cadw.

The long and complex history of the site is reflected in the well-preserved remains that can be seen at Brymbo today. The old ironworks retains many different features surviving from earlier periods of industrial development. Some masonry elements relate to the foundation of the site by John Wilkinson, but many have been replaced with later additions, making the building phases difficult to work out. The massive

Images

1. During its peak in the mid- to late twentieth century, the steelworks dwarfed the original site. The main elevation of the machine shop can be seen top-right. Image courtesy of Brymbo Heritage Trust.

2. A cast house and foundry at Brymbo Ironworks have early origins but remained in use until the twentieth century.

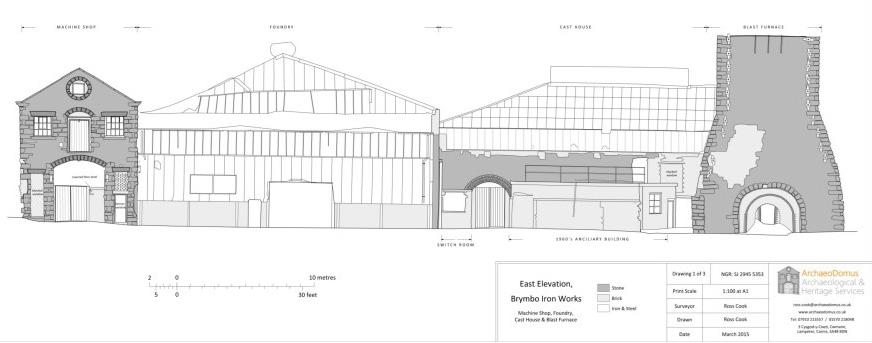

3. Elevation drawing showing (left to right) the pattern makers’ and carpenters’ workshop, the foundry, cast house and Old No. 1 Blast Furnace. © ArchaeoDomus

4. Left to right: Old No. 1 Blast Furnace (1820s), winch house (1964) and north charge ’revetment’ wall (1890s).

5. The concrete winch house, built in 1964, is a well-preserved relic of the more recent history of the site.

6. An archaeologist from ArchaeoDomus points to the newly discovered remains of a chimney base and flue system.

rectangular sandstone stack of 1820, known as Old No. 1 Blast Furnace, occupies the site of Wilkinson’s original blast furnace, known from an early print to have been circular.

A cast house and a foundry sit adjacent to the blast furnace. Originally built by the Darby Brothers in 1843, the foundry continued in use into the twentieth century. The pattern makers’ and carpenters’ workshop also dates to the 1840s; it survives in a relict state but is now dwarfed by the massive 1920s machine shop.

The site is enclosed on the west and north sides by a massively built sandstone revetment, or charge wall, holding back the uphill slope. The west charge wall retains phasing from the 1820s through to the 1870s, while the north wall was mainly constructed in the 1890s. Between them survives the concrete remains of a winch house built in 1964.

Recent groundworks have revealed new evidence of an early twentiethcentury brick-built chimney and a complex of well-built underground flues. These discoveries shed

new light on the way that hot-air stoves functioned at the site.

Both the steelworks and its surroundings have undergone extensive landscaping and change over the past 200 years and it is difficult to imagine the scale of the site as it once was. However, the ancient origins of the mineral wealth that was the key driver for industrial activity on this site were formed more than 300 million years ago in a landscape that was much more unfamiliar and difficult to visualise.

The coal seams that Wilkinson exploited were deposited as thick mats of plant debris in a period of deep geological history known as the Carboniferous. During this time, the earth’s continents formed one giant supercontinent known as Pangea, and north Wales was located close to the equator. This period of earth’s history is characterised by high levels of atmospheric oxygen (162% of the modern level) resulting from almost planet-wide tropical forests. Giant insects inhabited these swampy environments and massive plants towered over the landscape.

The layers of coal at Brymbo are interspersed with layers of mudstone and sandstone. These represent flash flooding events that rapidly buried much of an ancient river-delta in sediment and preserved an impressive landscape. This rapid reburial is the reason for the unusual quality and quantity of fossilised plants that have been discovered at Brymbo over the past 22 years, earning it the nickname ‘fossil forest’.

The fossil forest would have been dominated by giant tree-like lycopsids that would have grown to 30m (98ft) in height. Calimatian Horsetails and other spectacular fossilised species that have no related descendants today have also been discovered, providing a unique insight into this ancient world.

The story of the fossil forest is intrinsically tied to the local heritage. It was responsible for producing the coal that allowed the community to thrive economically during the Industrial Revolution. But it is also a reminder that in the last 200 years humanity has burned hundreds of thousands of years’ worth of carbon, sequestered by these primitive forests, to further economic and industrial growth. The introduction of huge quantities of carbon into the atmosphere that had been entombed for millions of years is thought to be one of the fundamental factors contributing to the climate change that threatens our planet today.

Images

7. A Calimatian Horsetail is just one of the species of fossilised plants discovered in the 314-million-year-old fossil forest. Image courtesy of the Fossil Forest Project.

8. The trunk and roots of a lycopsid uncovered at Brymbo. The trunk survives at over 2m (7ft) in height and the roots spread over 5m (16ft). © National Museum Wales

9. A computer-generated image showing the sympathetic conversion of the 1920s machine shop into a first-class visitor attraction. Image courtesy of Brymbo Heritage Trust.

10. As part of the Stori Brymbo project, the west charge wall, dating from the 1820s through to the 1870s, is being conserved.

11. The excavation of the fossil forest will take place over several years, providing opportunities for students and volunteers to work alongside scientists. Image courtesy of Brymbo Heritage Trust.

12. Four pits were excavated prior to building construction. Image courtesy of Brymbo Heritage Trust.

StoriBrymbo

StoriBrymbo aims to conserve, restore and celebrate Brymbo’s rich natural, industrial and social history.

The project is being developed by Brymbo Heritage Trust with funding from National Lottery Heritage Fund, National Lottery Community Fund, Natural Resources Wales and Cadw.

Cadw has been supporting the redevelopment of this important site that has both a regional and an international dimension.

As part of Stori Brymbo, a building is being constructed to protect and display the fossils while palaeontologists painstakingly excavate the fossil forest to understand the nature of the ancient landscape at Brymbo. The excavation will take place over several years, unlocking the potential of this important scientific resource for the public and the educational and scientific community.

Due to open in spring 2026, Stori Brymbo will be a new community-led visitor attraction. It will include a community hub and cafe, along with retail outlets and heritage crafts. The sympathetic conversion of the machine shop is underway and the Grade II* listed agent’s house and the scheduled pattern makers’ and carpenters’ workshop will be repurposed into homes for permanent exhibitions.

Stori Brymbo will create opportunities for training and skills development in the community. Heritage craft studios will work alongside the research and investigation of palaeo-botanical evidence and the industrial archaeology of the site.

• For more information, visit brymboheritagetrust.org

• Follow the project on Facebook (Stori Brymbo) and Instagram (stori_brymbo) for updates on news, opportunities and events.

• To get involved in the 2026 programme of student and volunteer dig opportunities, visit Eventbrite to book tickets — eventbrite.com/o/ stori-brymbo-22773346287

Stori Brymbo is an incredibly exciting project with so many diverse elements. Located just outside the city of Wrexham, we are benefitting from the success of Wrexham AFC as well as the forthcoming relaunch of Wrexham Museum and the Welsh National Football Museum. Wrexham is due to host the Eisteddfod this year and will also be bidding for City of Culture 2029 after coming second place in the last round. It’s an exciting time and we’re in the right place.’’

Nicola Sawford, Chief Executive, Stori Brymbo.

A spotlight on… Talley Abbey, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire

Set in a lush, green valley in the heart of rural south-west Wales, the Premonstratensian abbey of Talley, in Welsh ‘Talyllychau’ (literally ‘head of the lakes’), takes its name from its position at the head of two lakes.

The abbey was founded by Rhys ap Gruffudd — the Lord Rhys — prince of Deheubarth, for Premonstratensian canons between 1184 and 1189. Rhys was an enthusiastic patron of the new monastic orders in Wales; his descendants continued to support the abbey and his great grandson, Rhys Fychan, was buried there in 1271. Nevertheless, it remained the only abbey of the Premonstratensian order to be established in medieval Wales.

Known as the ‘White Canons’, the Premonstratensians established a reputation for dedicated prayer, ‘pitiable poverty’ and ‘abundant want’. Before 1200, they engaged in an ambitious building programme at Talley. From the main road, the remains of the crossing tower stand out as the most prominent feature of the abbey church.

Had the church been built to its original plan, it would have been approx. 73m (240ft) long, with a nave of eight bays, representing one of the largest Premonstratensian churches in Britain. However, owing to disputes with other monastic neighbours and attempts to claim the lands that the Premonstratensian canons needed to fund their work, the abbey never truly prospered and design changes were made during construction.

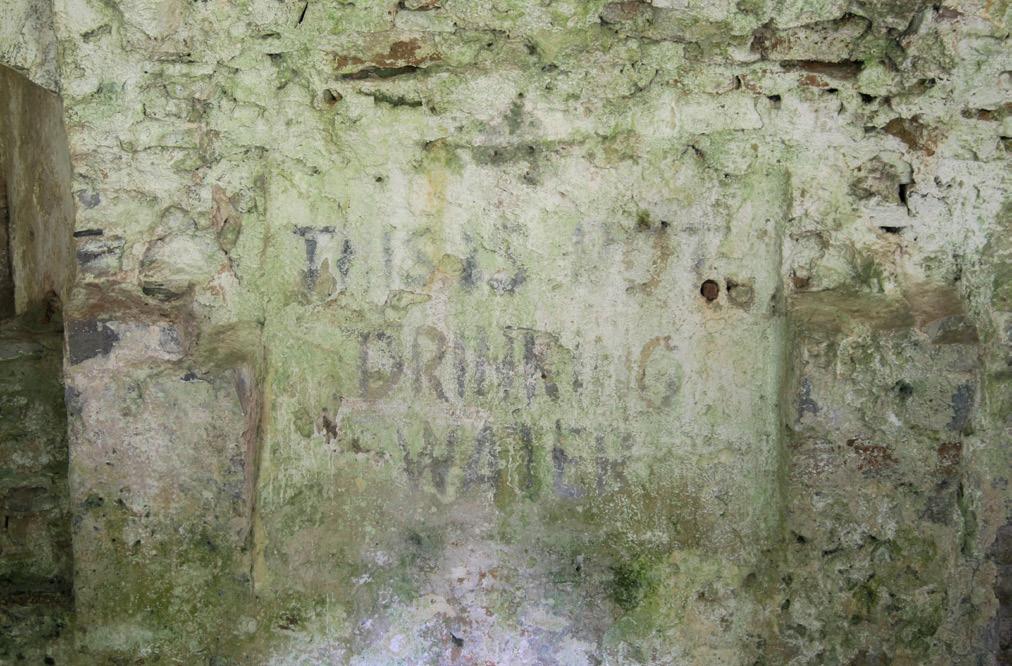

What we see today are the ruins of a church with a nave of just four bays, a south aisle, a presbytery, and north and south transepts, each with three chapels. Discoveries from excavations of the 1890s suggest that the walls were plastered and decorated in colour, and at least some of the windows were filled with painted glass. Parts of the floor were also covered with decorated tile pavements. The cloister was set to the south of the church, but only the footings of the northern half survive above ground level.

Talley Abbey was dissolved in 1536, but the abbey church remained in parochial use until 1772, when the present church of St Michael was built. A path through the modern churchyard leads to the shore of the upper lake from where you can enjoy the idyllic setting and the solitude of your surroundings.

For more inspiration on places to visit, take a look at the new Cadw Handbook, packed full of information on over 100 historic sites in Cadw’s care.

Heritage is good for you

We know instinctively and anecdotally that heritage is ‘good for you’. Who doesn’t feel better after exploring a historic site? But is there any proof of this? Polly Groom, Cadw’s Historic Environment Outreach and Engagement Manager, has reviewed the published evidence which connects heritage and well-being to explain the benefits that heritage brings.

‘Well-being’ may seem like a buzzword, a phrase that’s snuck into our language over the past few years. But what does it actually mean and what does it have to do with heritage? There are lots of different definitions but, in essence, well-being is the state of being comfortable, healthy or happy. Mental, physical and social health are all wrapped up in well-being.

Many things contribute to well-being, including the environment around you, your own personal circumstances, your health, your activities and your hobbies and interests. But, despite some things being completely outside your control — a long, wet, dark winters’ month for example — the good news is that there are plenty of things that you can do to improve your own well-being.

The importance of place

The physical environment around us is a strong influencing factor on people’s well-being. The historic environment — its buildings, monuments and structures — is part of this. It forms the backdrop to people’s lives, woven into where they live and work and is often seen as being visually attractive, which makes people happier.

Historic places very often also encourage healthy behaviours, including walking and socialising with others. But the links between place and well-being run much deeper than this. Research carried out by the National Trust in 2017 mapped people’s brain activity and showed that significant places brought about a more powerful emotional reaction than significant objects. These emotional reactions bring with them positive physical and psychological changes, suggesting that connecting powerfully and meaningfully with a place is good for you. These attachments to place are not necessarily fixed or long-standing. People become attached to places they’ve recently discovered and explored or places that they have found out more about. Heritage projects help people to learn about places and encourage them to care about what happens to them.

sited Castell Conwy forms the backdrop to the lives of the local community who live and work within the town.

Top

Post Covid, historic places were considered as special spaces for people to meet up and be reunited with friends. The cafe at Castell Harlech, Gwynedd, with its panoramic views and outdoor seating, provided such a haven.

Middle

Historic places can provide the backdrop for maintaining social connections. Situated alongside a cycle route, Castell Coch, Cardiff, provides the perfect location to stop off and take a break.

Bottom

A volunteering scheme run by Newport’s Youth Justice Team at Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire, greatly benefitted the young people taking part. A young person involved in cleaning a grave marker at the abbey took immense pride in his work. He gained the skills and confidence to chat to visitors about the project and developed a stronger sense of belonging as a result.

The importance of time

As the UK emerged from Covid lockdowns, visitors began to return to historic places. Research in England suggested that, in the early stages of lockdowns lifting, heritage sites were often chosen as trusted places and somewhere ‘special’ for people to meet up and be reunited with friends or family. Places with a long history and a sense of permanence helped to build a feeling of security and provide a sense of stability in an unstable world.

The importance of people

People need people. Strong social connections are a key part of well-being and there are many ways that heritage contributes to these. From taking part in an art workshop to meeting up with friends, heritage can provide the backdrop to forming and maintaining social connections. In other examples, the historic environment can be the key driver to undertaking an activity. A 2023 study concluded that young people directly engaging with heritage gained skills and confidence, took more pride in place and developed a stronger sense of identify and belonging. Taking part in heritage-based projects also encouraged stronger communities.

The importance of taking part

There is a long tradition of volunteering at archaeological and heritage sites and projects, making a big difference to both people and places. In recent years, we’ve started looking closely at what volunteers get out of this. A 2023 study focused on community heritage projects across the globe, and asked whether taking part in the projects improved people’s well-being or whether it was the other way around — were people with higher well-being scores simply more likely to volunteer? It concluded that taking part does make people happier with their lives overall and

develops a stronger attachment to place and community. Feedback from volunteers here in Wales suggests that people value the chance to take part in heritage projects for a whole range of reasons, including developing new skills, meeting like-minded individuals, learning and finding out more about a place. And, further afield, military veterans taking part in archaeological projects showed considerable improvements in their mental health, including decreased anxiety and depression. The same themes and benefits come up time and time again in the research — socialising, learning, developing skills and being part of a community.

The importance of authenticity

One of the important things about heritage and archaeology is its uniqueness — its authenticity. Excavation is a one-off process: once dug, the site can’t be put back. You can hold in your hand an object that was made thousands of years ago and there is only one of it. The same principle applies to the uniqueness of a place. There is something very special about standing in the very spot where history was made, a place once occupied by prehistoric families, perhaps, or Roman soldiers. When you volunteer on a heritage project, you are making a unique contribution to the sum of knowledge about a place or an object and becoming part of its story. There is often no single answer to questions about heritage; places and objects mean different things to different people and we seldom have a clear, definitive answer. Students can be encouraged to fill in the gaps about an object — who used this and when? — and to get used to uncertainty. Contributing to knowledge, instead of simply consuming it, helps to level the playing field between all participants; it makes us all storytellers and empowers everyone.

Top left

Volunteers at Plas Mawr, Conwy, frequently dress up in period costumes to bring the history of the Elizabethan house to life. They have won several heritage awards for both costume making and Tudor dancing, contributing to their sense of well-being.

Top right

Volunteers engaged in an archaeological excavation of St Patrick’s Chapel in St Davids, Pembrokeshire. Overlooking Whitesands Bay, the authenticity of the experience and the location of the site are likely to improve well-being. © Heneb: the Trust for Welsh Archaeology

Right

The feeling of finding and holding an object that is thousands of years old is priceless. Pictured is a volunteer at the excavation of Porth y Rhaw Iron Age promontory fort in Pembrokeshire. © Heneb: the Trust for Welsh Archaeology

Conclusion

Following a review of the published evidence, we can say with increased confidence that heritage plays a key part in improving people’s individual well-being and in building stronger communities. Whether people visit a castle for a day out, volunteer on an archaeological site or learn about the history of their local town, they benefit from connecting with these places. By understanding more about these interactions and what makes these experiences so special, we can endeavour to improve them for all concerned.

• Cadw are proud to be partners in Hapus, a space dedicated to mental well-being. The Hapus website — hapus.wales — includes a host of information, ideas and resources to help inspire us all to take action to protect and improve our mental well-being and that of others.

• Cadw supports Heneb: The Trust for Welsh Archaeology — heneb.org.uk — to run an outreach programme throughout the year.

• Visit the Cadw website for activity suggestions and a list of online resources used in this article — cadw.gov.wales/learn/fun-activities/ heritage-health-and-wellbeing

• The content of this article builds on research undertaken by Kirsty Usher from Aberystwyth University. Kirsty recently completed a six-month, ESRC-funded internship with Cadw, working on a report entitled Well-being in the Historic Environment.

‘This old castle has stood for nearly a thousand years. I don’t suppose Hitler will knock it down tonight’. The work of the Ancient Monuments Advisory Board in wartime Wales.

Swansea Castle, surrounded by modern office buildings in the city centre, has stood the test of time, including two world wars. © Crown copyright: RCAHMW

The Ancient Monuments Advisory Board was established in 1913 to protect Wales’ ancient monuments, but the outbreak of the First and Second World Wars hampered its ability to do this. Using records preserved in the National Archives, Jon Berry, Cadw’s Senior Inspector of Ancient Monuments, reports on the work of the Board in the first half of the twentieth century and the ways in which our historic monuments were repurposed during the wars.

The First World War

The Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act was enacted in August 1913 before the First World War started. It established three new delivery mechanisms to protect ancient monuments: Sections 12, 15 and 16. Section 12 allowed HM Office of Works to legally protect archaeological sites through scheduling. It represented the first significant reduction of an owner’s property rights over protected ancient monuments on their land and saw the state assume a cultural responsibility towards its own history on a scale never seen before in the UK.

Section 15 of the Act established Ancient Monuments Advisory Boards and section 16 permitted the appointment of one Inspector of Ancient Monuments per nation. The Inspector of Ancient Monuments for Wales was also to serve as Secretary to the Ancient Monuments Advisory Board for Wales, which was to undertake an advisory and approval role, recommending actions to the Commissioners of the Office of Works.

New scheduling proposals were presented by the Inspector to the Ancient Monuments Advisory Board for Wales for their approval. Once approved, the Office of Works was responsible for issuing the scheduling notices to owners. In the four monthly meetings leading up to the declaration of war in July 1914, the Board identified preliminary lists of castles, religious houses, town walls, Roman military sites and dolmens for scheduling.

The Board’s fifth meeting on 23 October 1914 reflected the solemn national outlook. It cited correspondence with the French Ambassador, stating ‘The Ancient Monuments Advisory Boards of England, Scotland and Wales desire to record the horror and indignation with which they have received the news of the wanton destruction by the common enemy, of the famous and beautiful monuments of your country…’

At the Board’s eighth meeting on 24 March 1915, Wilfred Hemp, Inspector of Ancient Monuments for Wales from 1914 to 1928, reported that ‘letters giving notice of intention to schedule had been sent by HM Office of Works to the majority of owners…’ However, scheduling was mostly placed in abeyance during the conflict and archaeological investigations at monuments in state care largely ceased. The first scheduling list of monuments of first-rate importance for Wales was not issued until 1921, including Anglesey, Caernarvonshire, Denbighshire, Flintshire, Merionethshire, Montgomeryshire and Radnorshire.

Some monuments were repurposed as part of the war effort; the area around Lamphey Bishop’s Palace, Pembrokeshire, was used as a hutted encampment during the First World War for the Manchester Regiment. Other monuments in Wales were deliberately destroyed. The ‘finest and best-preserved section’ of the Chepstow medieval port wall was pulled down and demolished to make way for the construction of National Shipyard No. 1, which aimed to mass-produce ships to a standard design. The Board was involved in discussions to save the wall but, on this occasion, the war effort was prioritised over the preservation of the ancient monument.

Very few monuments were offered or accepted into state care during the conflict. Preparations for receiving the guardianship of Denbigh Castle and Castell Harlech progressed as they had already been underway before the war started. But the offer of Castell Llansteffan to the Commissioners of the Office of Works in 1916 was rejected as ‘for the present it would not be possible to take any active steps in the matter.’ However, Castell Bryngwyn Prehistoric Enclosure and Caer Lêb Romano-British Farm, both in Anglesey, were ‘handed over to the custody of the Commissioners of Works by Lord Boston’ in February 1918.

The Board worked hard to establish a network of 50–60 informed local correspondents across Wales to report concerns regarding threats to ancient monuments or their poor condition. In 1916, the Board wrote to all correspondents ‘emphasising the need of vigilance lest monuments should suffer in war time’ and ‘pointing out the possibility that earthworks, etc. might be endangered by new schemes for bringing waste land into cultivation’. A large network was appointed, but the effort was weakened as many correspondents had to decline or step back from the role owing to circumstances connected to the war.

The interwar years

Following the armistice, the Board met in November 1918. Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Charles Peers, expounded on the preservation policy of the Office of Works, noting that Raglan Castle ‘was likely to be handed over in the near future [it did not enter guardianship until 1939], and Basingwerk Abbey and Beaumaris and Conway Castles as instances of monuments which would gladly be taken over should the opportunity arise’. The Office of Works took into guardianship or purchased the freehold of a further 46 monuments during the interwar period, including some of Cadw’s finest historic sites such as Beaumaris Castle, Caerleon Roman Fortress, Eliseg’s Pillar and St Davids Bishop’s Palace.

From 1919, many guardianship monuments were utilised in wider government initiatives, such as the King’s National Roll Scheme, in which disabled ex-servicemen were employed. Relief schemes in Wales included the re-excavation of the moats at Ogmore, Kidwelly and Beaumaris castles.

From January 1938, a system of mutual consultation was established between the defence ministries and the Office of Works as the Inspectors of Ancient Monuments were made aware of all proposals to acquire or requisition land. Their close scrutiny of the land allowed many ancient monuments to be fully excavated and recorded for posterity rather than destroyed without record.