Science Fiction provides an overarching framework for Monster and Kynic, two exhibitions that explore notions of scientific reality and its mutations within popular consciousness and media. Recent research by the Australian Academy of Science has shown that Australians have little knowledge of the machinery of science and any broad engagement is based on images produced in literature and film that present a fantastical view of what science might be. From Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) nothing it seems is more entertaining than a mad scientist or an experiment gone wrong. While technology is the cement that binds civilisations, the prospect of its coming unstuck generates intense excitement as evidenced in the capacious history of B-grade film and pulp fiction.

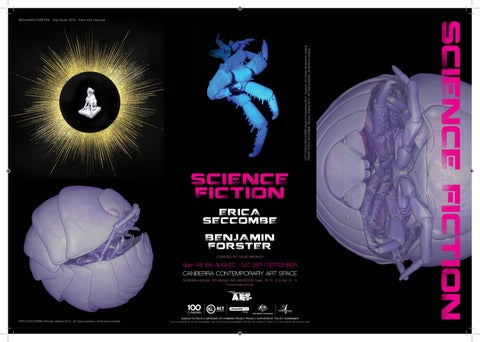

Science Fiction brings together Erica Seccombe and Benjamin Forster, two artists who employ bona fide scientific methodologies for work that examines the tensions between science and its suspect appearances in popular culture. Both, to some extent work in the ‘god’ zone, albeit with tongues in cheek, using science to suggest the construction of creatures that exist outside the ‘natural world’ and thus have the potential to wreak havoc upon humanity. They draw upon the familiar, common garden organisms and the family pet, to produce alien objects and ideas. Their works critique and even mock the idea of artists being scientists and vice versa; blending empirical method with fantastic imagination their work reflects a divergent yet electrifying relationship between science and art.

Neither Monster nor Kynic should be viewed as science per se. If either exhibition advances human knowledge it is paradoxically towards an understanding of how little is known and in spite of significant advances, how much continues to remain a mystery; beyond the control of mortals. It is here that imagination steps in and artists, like writers and filmmakers, envisage scientific potential that is necessarily beyond its current capabilities. Monster and Kynic reflect the idea of ‘botched’ experiments –ultimately Seccombe did not make the two-metre monster she envisaged and Forster did not fuse the cell of a man with that of a dog (although it was not for want of trying). From state-of-the-art laboratories at The Australian National University and The University of Western Australia they used the most advanced technologies to test scientific clichés and the resulting exhibitions reflect grandiose trajectories of failure. Within the story of failure, however, lies the success of the artwork for which science provided the means to an unknown end.

Taking the common garden slater Porcellio Scaber as her point of departure Erica Seccombe, in collaboration with Professor Tim Senden and Dr Ajay Limaye (ANU Department of Applied Mathematics and Vizlab), applied the notion of relativity to suggest that under magnification of the most extreme kind, this benign little creature takes on alien proportions. Using the latest technologies available to science, the ANU Department of Applied Mathematics has developed 3D Microcomputed X-ray

Tomography (XCT) that enables scientists to see the material structure of an object as a virtual model. Seccombe has used the resulting volumetric data and digital visualisation processes to produce an exhibition of printed threedimensional creatures and parts thereof, that are able to inspire fear and awe in an ‘alien’ inspired nursery. Blurring the borders of film and scientific data the exhibition also includes a 3-D cinematic screening of the amplified isopod so that it appears significantly larger than life.

Nature is a worthy match for our worst imaginings and when it comes to creepy-crawlies there is good reason to be fearful. B-grade movies have exploited an uneasy relationship with the natural world and the irradiated ants in Them (1954), Attack of the Crab Monster (1957), The Fly (1958) and The Wasp Woman (1959) are but four examples of films that deal with hazardous metamorphoses resulting from scientists tampering with nature (and its multi-footed creations). Monster recreates the atmosphere of a postapocalyptic laboratory in which this risky meddling might have taken place as we find enlarged isopods and body parts in varying states of completion, stored as if to be employed at some future time for an unknown purpose. The parts glow in the dark suggesting a form of irradiation while the stereoscopic project generates a sense of serious inquiry whereby the viewer is able to explore the innermost regions and experience the complexities of this simple life form.

Monster encompasses unambiguous visual allusions to Swiss Surrealist H.R Giger’s creature and design for Alien (1979) and the prequel Prometheus (2012). While these latter films might be technically superior, the essential tone differs little from schlock 50s sci-fi which Seccombe effectively exploits to engage her audience via their familiarity with this genre. With this dark aesthetic in mind she updates the work while also connecting it to the Ancient Greek figure of Prometheus and Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, originally titled The Modern Prometheus. In Greek mythology Prometheus was the creator who defies the Gods by giving fire to humanity and in the classical Western tradition he represented the quest for scientific knowledge as well as the dire consequences that result from playing with fire.

Kynic

Benjamin Forster’s attempt to fuse the blood cells of artist Billy Apple with that of a canine, to produce a viable human-canine hybridoma, or an immortal cell that contains both human and canine DNA, is a project that has its roots in the ancient Greek philosophy of Cynicism. In their quest to lead virtuous lives at one with nature, original Cynics such as Antisthenes (445-365 BC) and Diogenes of Sinope (404-323 BC) inhabited the streets; like dogs. The original derivation of cynic was kynikos or dog like. Although Forster’s experiment has significant ethical implications his intention is pure. It is less to conceive a mythical lycanthrope (werewolf) in a petri dish and more to produce an allegorical totem that reflects an ‘ideal position’ for contemporary artists and scientists in the tradition of ancient forbears who saw the creative benefits of nonconformity. For six long months Forster worked in the laboratories of SymbioticA, at the University of Western Australia where he became intensely immersed in the science of cross species hybridisation.

“Using a haemocytometer we counted the concentration of BA-BL in our culture. 3 million per 1ml. The suspension was diluted to 1 million to 1 mil and pipetted 1 ml each of cell suspension in to 20 cryovials. To each 0.2 ml of 80% FBS and 20% DMSO (antifreeze) was added. DMSO helps retain

cell structure during freezing, but is also toxic to the cells if left at room temperature. As such the cryovials are sealed quickly and transvered to -20° for 2 hours before -°80 …. ” Benjamin Forster, from Progress Report (03/04/13)

On 26 March 2013 the canine cells died. As their mitochondrial powerplants withered, disintegrated and vanished, nothing remained to place between glass slides under the microscope. In the gallery the cell would only ever have been dead. Removed from its life supports in the lab Forster was compelled to reconsider the implications of the cell’s transformational journey from science to art. The original context in which the cell was to be seen therefore survives as the central idea: a ‘memorial’ plinth co-joins the detritus of scientific experimentation with artistic process. Urine soaked drawings that “present allegoric fragments from the history of Cynicism” lie crumpled on the floor and texts that record the scientific conversation that lead to the death of a cell resurrect the ingenuous honesty of the ancient Cynic. There may well have been cells to show but in the end they were less significant than the narrative fusion of scientific method and philosophical sub-texts.

Forster’s second work, Knowledge, Intermediate, You (Considering Serres) 2013 introduces the persuasive powers of advertising into an amorphous emulsion of science and truth. If the average person has little understanding of science coupled with the unequivocal conviction of its intrinsic objective truth, it is an ideal tool for the industries of persuasion. Hair care, skin care, dental hygiene, medical supplies, cleaning agents are but few of the industries to draw credence from ‘laboratory testing’. Nothing it seems is more credible than a person in a white coat backgrounded by bubbling test tubes and bunsen burners, however bogus the claim. Forster disrupts the relationship between medium and message using a partially dismantled digital television screen for a video collage of ‘scientifically tested’ products. A single, lit, domestic light bulb sits behind the screen, a bathetic representation of divine enlightenment.

David Broker, July 2013