BLAZE EIGHT showcases the work of eight ACT emerging artists: S.A. Adair, Katherine Griffiths, Martin James, Alex Lewis, Hardy Lohse, Katy Mutton, Jemima Parker and Timothy Phillips. These artists all explore aspects of the human condition; from the personal to the political, the molecular to the global. Griffiths’ exploration of dreams and emotional states and Phillips’ devotional shrines are intensely personal but will resonate with many. Adair and Parker’s installation/drawing works use meditative processes to investigate our experience of the world around us. Mutton and Lewis explore things humans have built and how they affect our history and our experience of space, respectively. And James and Lohse both explore the most human crisis of current Australian politics- ‘boat people’.

S.A. Adair ’s Contagion is a site-specific installation that grows and spreads much like a disease. Made up of felt pieces cut into organic linear shapes, Contagion makes its way outwards from the corner of the gallery in an orderly fashion, like cells multiplying. Adair experiments with the process of making and installing, letting chance and errors affect how the work develops. Adair’s installations are organic in an almost biological sense; the components are allowed to behave in a characteristic way in a specific environment, to grow naturally, errors prompting the work to evolve. Contagion occupies both two-dimensional and three-dimensional space, subtly encroaching on the viewer’s space as it spans adjacent walls, and encouraging reflection on self, space, and the immensity of human life- from the basic cellular level to the shape of humans’ ongoing existence.

Katherine Griffiths ’ haunting photographs explore dreamlike states and their relationship with lived experience. In the works included in Blaze Eight , Griffiths herself is shown outside at night or just on dark, in mysterious circumstances. While narrative is open to interpretation, the dream-like states of sleepwalking or being suspended and possibly about to fall are so common as to be almost universal. Griffiths makes these scenes very personal, through her presence in them and by shooting at locations that mean something to her; cherished houses and suburban alcoves. The homely fabric objects in the works - doona, pillow, dress - are also intensely personal, and mediate her interaction with the darkened scene enclosing her. Through her works, Griffiths brings together the familiar and the unknown, the conscious and the subconscious.

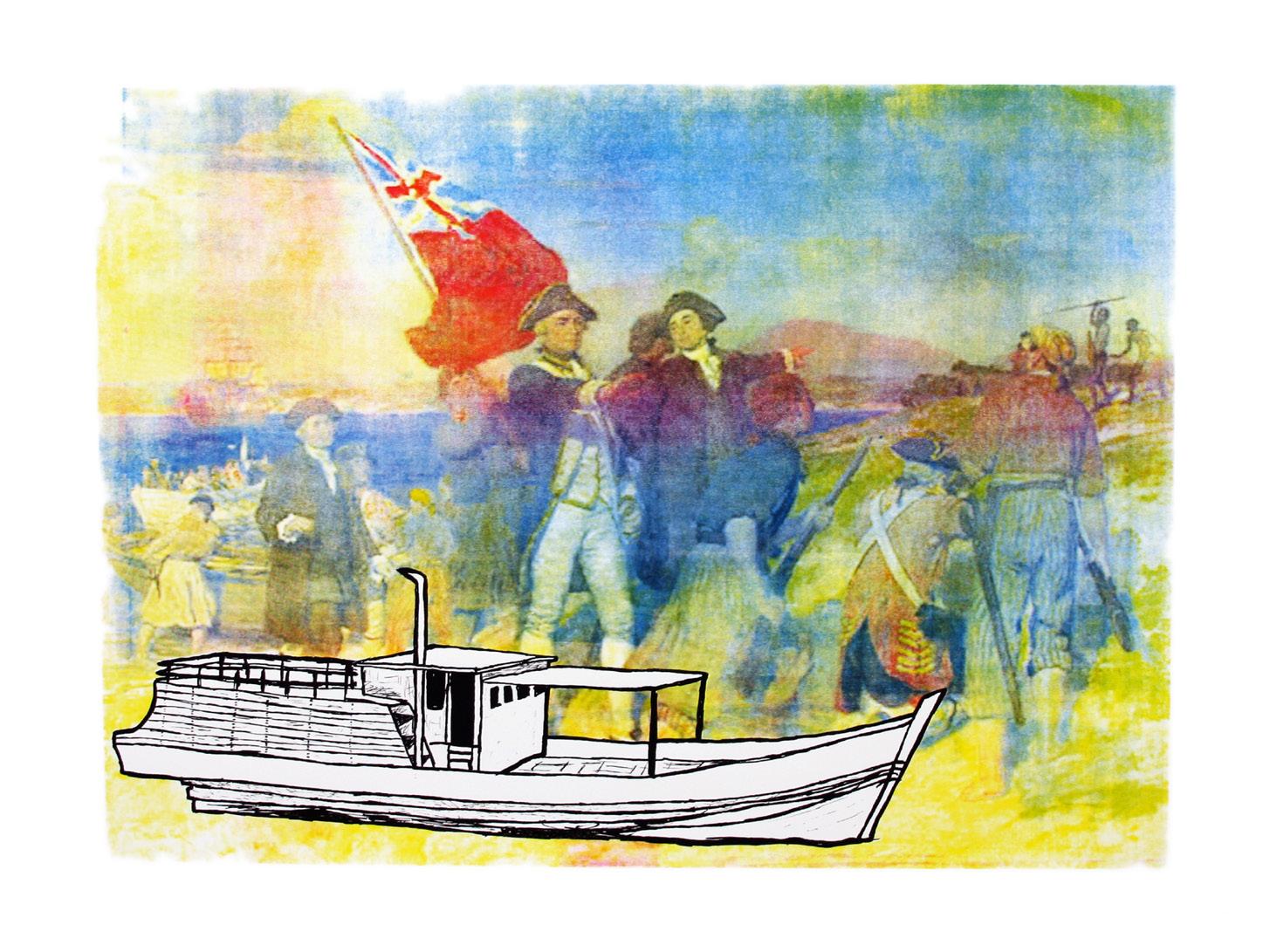

Martin James draws from his fascination with advertising and mass media, combined with his background in printmaking and drawing, to masquerade as a wolf in sheep’s clothing. By utilising techniques found in product packaging and advertising, he critiques the manufactured world of spin and the people, products and organisations out to sell product or politics. The series presented in Blaze Eight interrogates Australian identity by jesting depictions of colonial arrival on Aboriginal land, with Captains Cook and Phillip staking claim upon the country (originally painted by E. Phillips Fox and Algernon Talmage). James questions why this bloody occupation conducted in the name of the British Empire is celebrated by white Australia, yet people seeking refuge from war, political regimes, persecution and suffering are treated as criminals. Each image is presented in multiple, the historical elements misprinted and blurred; but the boats of asylum seekers sit sharply in the foreground in black and white. This contrast speaks of the erosion of time, difference in opinions, and ultimately reminds us we must remember our mistakes if we are to grow together as one.

Although approached from a very different perspective, Hardy Lohse shares similar concerns to Martin James on the current state of international human rights and what it means to be a contemporary Australian. Lohse’s father came to Australia by boat shortly after World War II, and as a first generation Australian of German descent, his practice has been informed by extensive travel and immersion in many different cultures,

giving him an appreciation of hindsight and differing perspectives to assess the anthropological lay-of-the-land in his own country. Where Lohse’s recent work has used the figure as an indicator of scale and a reference point to express deterioration and dysfunction of urban environments, the pieces in Blaze Eight are stripped back to nothing but portrait and a stenciled racist slogan. Lohse has worked with Canberran young people to produce the series, many of whom are refugees. These works are an in-yourface reminder that unless you’re an Indigenous Australian, you are a boat person. Or maybe you’re a fancy plane person, but an immigrant, nonetheless.

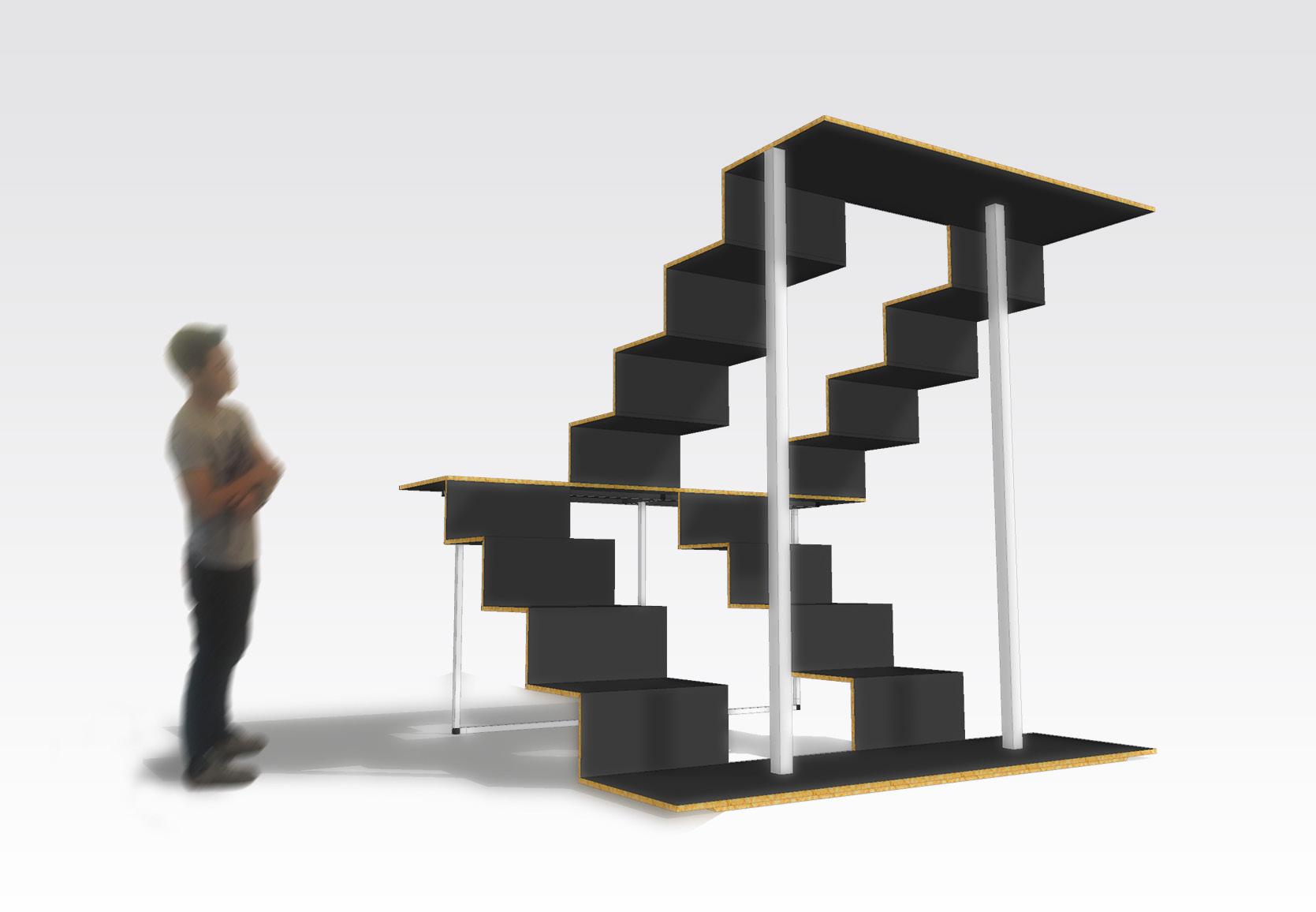

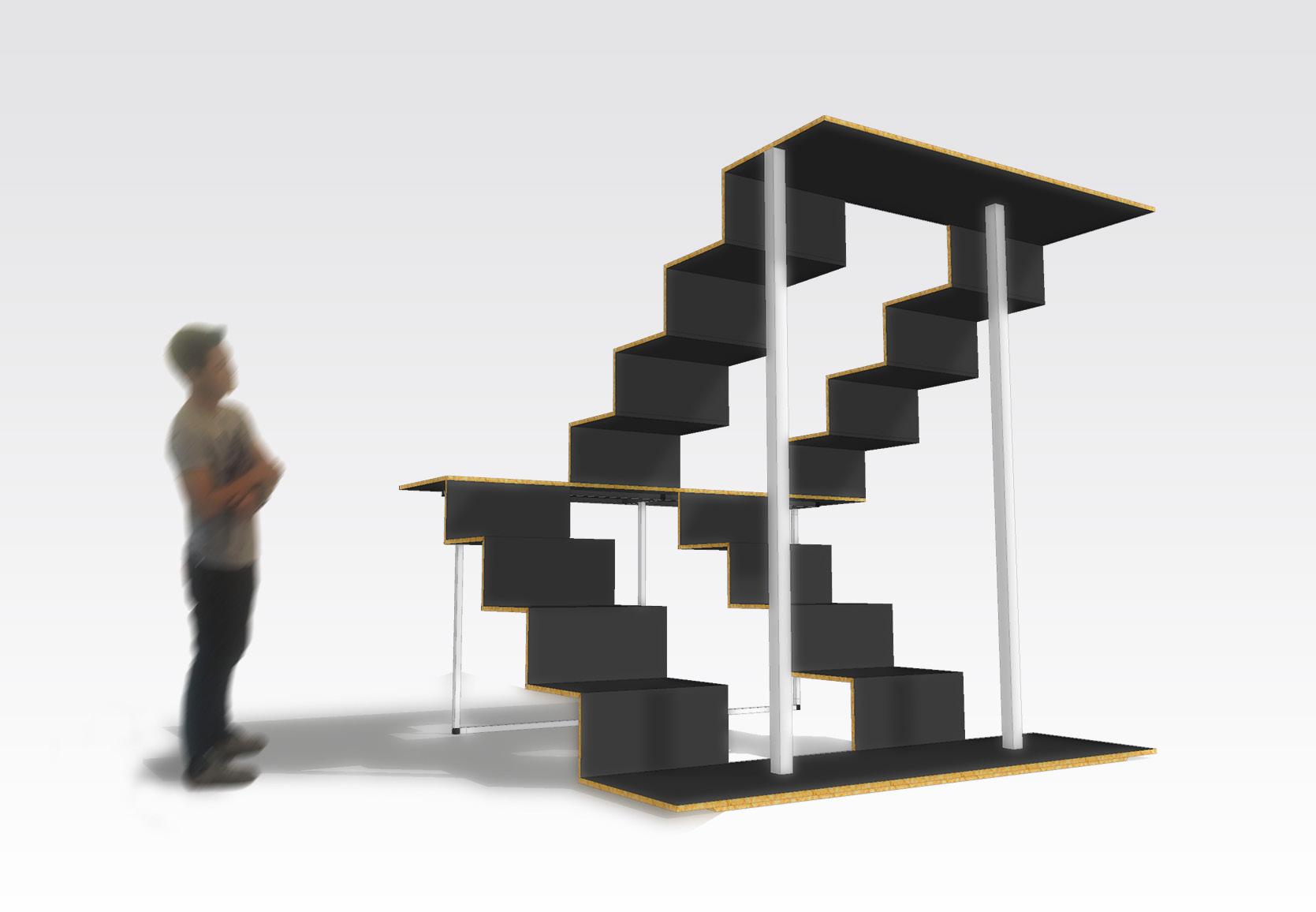

Alex Lewis ’ work is strongly influenced by the body’s relationship with architecture and the urban environment, and how subtle modifications in scale and function can greatly alter our perceptions. These investigations of structure and form stem from architectural line drawings and computer generated images, so it’s no surprise his sculptural works can at first appear as floating drawings, only to pop-out into the third dimension when further examined. Staircases that promise function yet deliver none are

a recurring motif in Lewis’ work. Presented in Blaze Eight is Lewis’ most ambitious sculpture to date - Hybrid Problems In the 2.5 metre-square work, twin black staircases loop in unison, mirroring each other like DNA strands, reflecting our constructed surroundings and basic genetic make-up alike. By distorting familiar forms he is subtly able to consider the larger human condition, including futility and the Sisyphean labor of everyday existence.

Katy Mutton ’s practice is informed by an ongoing concern with warfare. Her early work was created out of a desire to honor and better understand the experiences her relatives suffered in World War II, but has since become a reference point to commentate on modern day conflict and the long-term impacts of war. Her latest suite of work entitled Harbingers explores the proliferation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or Drones, across the globe with seemingly little accountability. In 2014 they have become commonplace across our landscapes – as eyes-in-thesky at sporting events, for 3-D mapping, farming applications and search and rescue. Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, plans to deliver packages by drone in the near future. Meanwhile, iPhone Apps give live updates on drone strikes worldwide, tracking and mapping covert war - airborne killing machines ghost foreign landscapes, operated by people who clock off at five and go home to suburbia. Mutton is fascinated by their idolised status in modern-day warfare, emphasising their incredible monetary value with glimmers of gold as if caught by the sun, seen yet unseen - lethal chameleons shimmering above camouflaged topography.

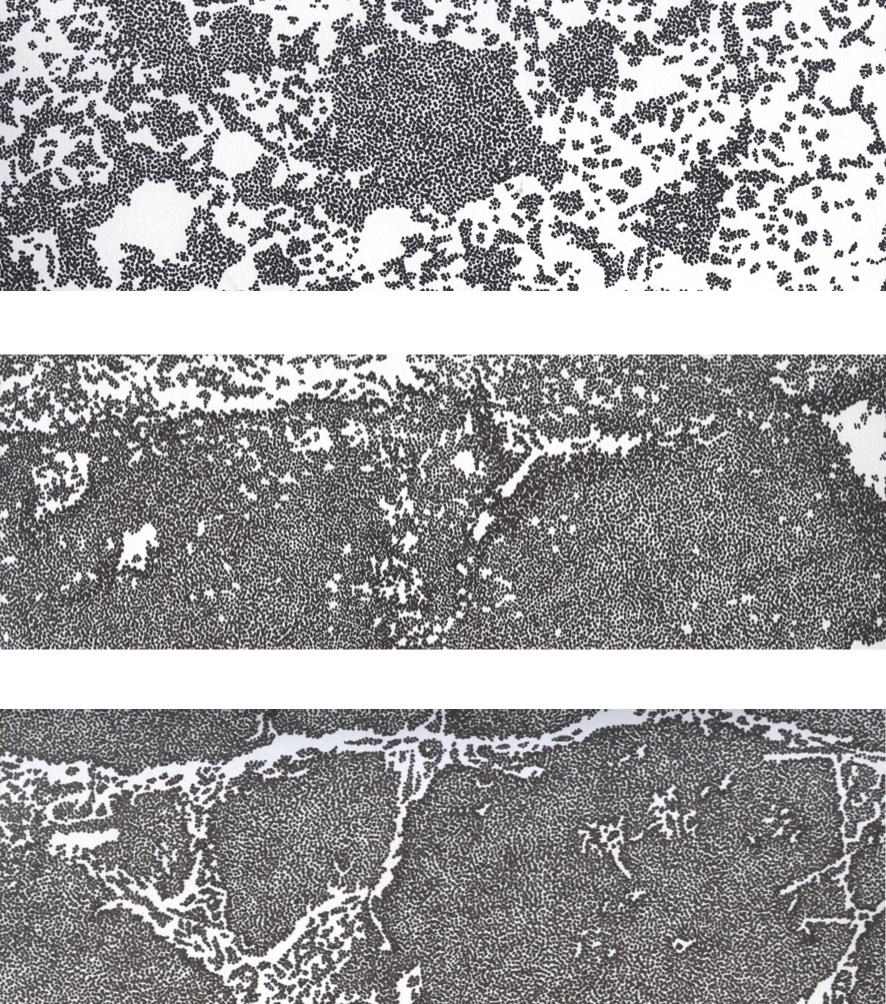

In her recent drawings, Jemima Parker has been methodically and meditatively exploring patterns and textures that she finds in her everyday surroundings; signs of age and disrepair such as weathered paint, aged concrete and rust. For Blaze Eight she has made a series of these drawings in the format of scaledup microscope slides, zooming in on these patinated textures. They are presented in a suite of ten, vertically spanning the high gallery wall, rather like Donald Judd’s Stack (1967). Like Judd, Parker presents something very ordinary as something extraordinary and valuable, but Parker also presents us with two transformations- that of the urban material itself as it weathers and cracks; and that of the drawing, which translates the texture into one made up of thousands of dots of wavering density, suggesting the activity of the molecules, particles and even organisms that these textures are made up of.

Tim Phillips ’ works are every bit as seductive and beautiful as ‘Old Master’ Still Life paintings, but there’s much more to them than that. They are in fact very personal self-portraits, which explore the idea of devotion and shrines- painting is a devotional act in itself. Instead of precious objects or flowers, Phillips paints things which are readily accessible to him: cheap jars and paper bags, bundles of sticks from outside his studio. The colours he throws into the mix, largely in the background, speak of distinct personal choice and also the history of painting- saccharin pastel pinks and bold warm yellow. Phillips also introduces jarringly fantastic imagery from his own imagination and found images. Rainbows- not an object, but an ephemeral phenomenon of light- arc unrealistically across the horizontal surface depicted in the still life, and images of porn stars and penises appear as if through random portholes within the surface behind the still life objects. These collaged images reference visual cues in religious devotional paintings, but the sense of rapture and posed body parts are a little different. Phillips celebrates Still Life painting and makes it his own, whilst also challenging its history. In his work, Still Life is no longer a record of high status, and it cheekily reveals glimpses of things which are not seen in the group of objects and the surfaces underneath and behind.

Alexander Boynes & Annika Harding , February 2014